While I knew that research studies had revealed that many nutrients are delicate and can be easily damaged, I was shocked when I found out exactly how many nutrients were lost due to overcooking. Traditional ways of cooking, such as boiling certain vegetables, can deplete water-soluble vitamins, such as vitamin C and the B vitamins, as well as flavonoid phytonutrients. When I found out that up to 80% of the folic acid in carrots and 66% of the flavonoids in broccoli are destroyed through boiling for extended periods of time, I realized how important it was to develop better alternatives to traditional cooking methods that would not only enhance flavor but also preserve vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. I call these methods the “Healthiest Way of Cooking.”

Traditional cooking methods oftentimes involve long cooking times. This results in overcooked foods that are soft, mushy and devoid of much of their natural flavor. It was once believed that cooking for long periods of time helped to develop the flavor of food. Although this may be good practice for root vegetables used in soups and stews, it is not good for leafy greens and other vegetables. For example, many people boil broccoli until it’s soft. No wonder broccoli doesn’t rank high on their list of favorites—waterlogged bland food wouldn’t be a favorite for anyone. The long cooking times frequently used in traditional cooking methods have another drawback. Not only does overcooking take the enjoyment out of food, it destroys vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and many other nutrients as well.

The realization that overcooking was the problem with traditional cooking methods inspired me to create the “Healthiest Way of Cooking.” The “Healthiest Way of Cooking” includes a variety of methods designed to maximize retention of the beneficial vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and other nutrients found in food, which can easily be destroyed if care is not taken in preparation and cooking.

Plus, the techniques, recipes and tips that I will share with you will also help enhance the flavor of your food. No matter how nutrient-rich a food may be, if it doesn’t taste delicious, you’re not going to enjoy it. And what’s the point of food if it doesn’t bring you pleasure? I believe that eating nutrient-rich foods should be a celebration and an enjoyable experience of knowing that you are doing something wonderful for yourself.

Many nutrients provide antioxidant protection against free radical activity, that can negatively affect cellular structures and DNA. These include vitamins such as A, C and E as well as phytonutrients such as the carotenoids, betacarotene and lycopene, and flavonoids such as phenols, quercetin and rutin. Studies have found that cooking in general, the length of cooking time and the amount of water used during cooking can impact the concentration of antioxidants found in your vegetables.

You may be surprised to find that according to recent research some vegetables, such as carrots and tomatoes, actually offer greater availability of antioxidants after they have been cooked. Carotenoids are usually hooked together with proteins or locked into their own crystal-like structure when found in their natural state. Heating helps break down these structures and free carotenoids for digestion and absorption into our cells. The release of carotenoids through cooking can be measured. In carrots, for example, about 40% more carotenoids are released and made available through cooking.

Studies on the effects of cooking on the phenolic phytonutrients in zucchini, beans and carrots found that these antioxidants are best retained if cooked in small amounts of water. Dr. Anne Nugent, a nutrition scientist at the British Nutrition Foundation, has noted that it is the presence of water, rather than the cooking process itself, which makes the difference in the preservation of antioxidants. “In other words, the antioxidants would be lost upon boiling rather than steaming. . . . . it is important not to overcook . . . . as this will result in excess antioxidant loss,” according to Dr. Nugent.

Since the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods include light steaming or “Healthy Sautéing” for a minimal amount of time, the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods used in the recipes are the ones I recommend to cook the different World’s Healthiest Foods—not only to maximize the retention of their antioxidants, but also to enhance their flavor, texture and color.

Finding the best way to prepare each of the World’s Healthiest Foods took time. I repeatedly tested the preparation of each of the World’s Healthiest Foods until I found the best cooking method to use for each food. This is how I discovered that cauliflower tastes best when “Healthy Sautéed,” broccoli is best quickly steamed to retain its moisture, and “Quick Broiled” fish is the most moist and tender. I prepared some of the foods over 100 times until I got it precisely right. I tested the recipes until I was satisfied that their flavor, nutritional value or ease of preparation couldn’t be improved.

I tried to make the recipes quick and easy using not only the right techniques, but a minimal number of ingredients. At first glance, the methods may seem too simple and quick to develop flavor or use too few ingredients to highlight the taste. But once you prepare them, you will see that they work really well and bring out the best flavor of your food. Believe it or not, it is actually much more difficult to create a great tasting, nutrient-rich, 5-minute recipe than to come up with a recipe that has lots of ingredients and takes many hours to prepare. I’ve literally put the methods and recipes in this book to the test, so I know they will work well for you.

Most cookbooks tend to concentrate on the flavor of food and ignore the loss of nutrients that can accompany prolonged cooking times. One of the reasons this book is special is that the recipes and preparation methods focus not only on bringing out the best flavor of your food, but also on preserving the maximum number of nutrients.

You will quickly see that the way you prepare foods can not only maximize their health benefits but optimize their taste, and therefore your enjoyment. “The Healthiest Way of Cooking” is easy, and its rewards are numerous.

The Step-by-Step “Healthiest Way of Cooking” recipes in each food chapter offer maximum benefits with minimal cooking. They are easy to follow (each recipe has only a few steps), and they don’t take much time to prepare. In fact, 95% of the recipes take less than 7 minutes! Since they require a minimal number of ingredients and you only need a steamer or skillet and just a few utensils, cleanup is also minimal. These recipes are great for people who don’t know how to cook or don’t have time to cook.

Since you won’t enjoy food if it doesn’t taste good, my philosophy is not just to eat nutritious foods, but to also enjoy them by preparing them properly. By following my recipes, you will not only have great tasting food but will have fun preparing it. Preparing food this way will help you build a relationship with your food. Food is essential to life; we all have to eat to live, so why not eat great tasting, nutritious food that adds to your enjoyment of life!

In the remainder of this chapter, you will find a lot of valuable information that addresses numerous aspects of cooking. I discuss the benefits of cooked and raw food, a topic on many people’s minds today. Additionally, I cover how you can best preserve the nutritional value of foods with the “Healthiest Way of Cooking.” Many readers of the World’s Healthiest Foods’ website, www.whfoods.org, have written to me asking about cooking with oils, so I have also addressed this here. Details on the cooking methods that serve as the foundation of the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” are presented, along with recommendations for the best cookware to use. Finally, you’ll read about high temperature cooking and the impact it has on the nutritional value of food.

Few human cultures have evolved or been sustained without incorporating some cooked foods, including cooked vegetables, into their eating practices. I believe that it is possible to get the full nutritional benefits from a food that has been cooked, provided that the cooking method is uniquely matched to the food and exposes the nutrients in the food to minimal damage.

• To make it easier to digest

• To increase the availability of nutrients for assimilation

• To enhance its flavor

• To preserve food safety

Here are more details on the benefits you will enjoy by cooking foods for short periods of time using the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods:

Cooking vegetables quickly softens their cellulose and hemicellulose. This makes them easier to digest and allows their health-promoting nutrients to become more readily available for absorption.

In the case of some vegetables, cooking can actually increase the variety of nutrients that get released inside our digestive tract. Cooking onions is a good example. Onions are a member of the Allium family of vegetables. Most vegetables in this family have unusual amounts of sulfur-containing compounds that help protect our health. Heating onions for five minutes increases the variety of sulfur-containing substances the onions provide since it triggers chemical reactions that create variations in those sulfur compounds.

The carotenoid phytonutrient, lycopene, which is found in tomatoes, is another example of how a nutrient’s bioavailability can increase when the food is heated. Heating disrupts the cellular matrix in tomatoes, which increases lycopene’s availability for absorption. Heating is important in increasing the availability of lycopene because it not only disrupts the cell matrix but also converts the “trans” form of lycopene found in tomatoes into the more bioavailable “cis” form. This means that your body absorbs the lycopene in cooked tomatoes more easily than the lycopene found in raw tomatoes. (For more on Tomatoes, see page 164.)

I recommend cooking vegetables al denté. Vegetables cooked al denté are lightly cooked and are tender on the outside and firm on the inside. The “Healthiest Way of Cooking” vegetables is a great way to enhance their flavor as well as retain their maximum number of nutrients. By softening the texture just a bit, cooking vegetables al denté makes their inherent flavors come to the forefront. This is quite different than with traditional cooking methods, which usually lead to overcooking that causes flavors to dissolve or evaporate rather than come to life (for more on Al Denté, see page 92).

For some foods, especially animal foods, cooking temperature and duration are associated with the elimination of potentially disease-causing bacteria. Meat and poultry are cooked to avoid exposure to E. coli bacteria. Eggs are cooked to avoid Salmonella-caused food poisoning. Formerly, Salmonella bacteria were found only in eggs with cracked shells, but now they may be found even in clean, uncracked eggs. To destroy Salmonella, eggs must be cooked at high enough temperatures for a sufficient length of time.

Less known, but equally as important, is that some beans must be cooked to eliminate toxins. For example, raw kidney beans contain a naturally occurring compound called haemaglutin that causes red blood cells to clump together and inhibits their ability to take up oxygen; cooking deactivates this compound. Soybeans contain a trypsin inhibitor that prevents the assimilation of the essential amino acid, methionine, if not deactivated with heat.

Some foods should always be cooked or processed (sprouted, soaked or fermented) and never eaten raw:

DRIED BEANS: |

Potential toxins found in raw beans are decreased by cooking, soaking and sprouting. |

GRAINS: |

Contain phytic acids that can partially block the availability of minerals. Grains should be cooked, soaked or sprouted to help reduce their phytic acid content. |

EGGS: |

May contain Salmonella bacteria and therefore should always be cooked. Also, the iron and biotin found in eggs are not as well absorbed if eggs are not cooked. Raw egg whites contain a glycoprotein called avidin that binds to biotin very tightly, preventing its absorption. Cooking the egg whites changes avidin and makes it susceptible to digestion and unable to interfere with the intestinal absorption of biotin. |

While I encourage you to enjoy vegetables prepared using the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods, I believe both raw and cooked vegetables can play important roles in your “Healthiest Way of Eating.” Most animals thrive on diets consisting almost exclusively of raw, uncooked food, but raw foods require more careful and thorough chewing than cooked foods. Over 80 of the World’s Healthiest Foods do not require any cooking. These include the fruits, nuts, seeds, dairy products, herbs and spices, and most of the vegetables. You can find recipes and tips for these foods in the different food chapters.

By chewing well and savoring the tastes and textures of raw food and by following the cooking suggestions for each of the World’s Healthiest Foods, you will receive the unique nutritional benefits from both raw and cooked foods!

Here is a question that I received from a reader of the whfoods.org website about fresh versus frozen food:

Q Is fresh always better than frozen?

A Actually, fresh is not always better than frozen. The reason is very simple: “better” depends on quality.

Suppose, for example, we chose the highest quality food source: an organically grown food, grown during its natural season and in its native habitat. In this case, would the fresh version always be better than the frozen one? Yes! Freezing would decrease the overall nutrient content of the food (although in some cases, only slightly). So fresh in this circumstance would always be better.

But imagine a second example, where the fresh food—let’s say, fresh broccoli—was grown out of season, in a non-hospitable habitat, with the use of artificial fertilizers and pesticides. And to continue on in our example, let’s say the frozen broccoli was grown organically in its native habitat in season. In this case, the frozen broccoli would make a better choice than the fresh broccoli because of its higher quality. Research studies have shown organically grown broccoli to have higher nutrient content than conventionally grown broccoli and to have virtually no pesticide residues.

Particularly when foods are not in season, or when organically grown products are not available, frozen organic alternatives make good sense. When fresh, organically grown foods are available, however, they always top the nourishment chart!

With the very precise and short cooking times used in the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods, you’re unlikely to get a nutrient loss of more than 5–10%. This range is dramatically lower than the losses that occur in food processing or in most restaurants and cafeterias where food is routinely overcooked. Processed foods often have nutrient losses in the 50–80% range—as much as 10 times the amount that occurs with the “Healthiest Way of Cooking.” While there is a 5–10% nutrient loss that occurs with careful, minimized heat and water exposure it is accompanied by other changes in the food that support our health. These other changes include improved digestibility and the conversion of nutrients into forms that are more easily absorbed.

The way that food is cooked is absolutely essential for avoiding unnecessary nutrient loss. Five minutes can make an enormous difference in the nutritional quality of a meal. (This is about the time it takes to walk away from the stove, answer the phone and say that you can’t talk right now because you are in the middle of cooking.) In addition, every food is unique and should be treated that way when it comes to cooking temperatures and times. That is why I don’t recommend boiling spinach for more than one minute or steaming broccoli for longer than five minutes.

The traditional rules about heat, water, time and nutrient loss are all true. The longer a food is exposed to heat, the greater the nutrient loss. Being submerged in hot water (boiling) creates more nutrient loss than steaming (surrounding with steam rather than water) if all other factors are equal. The lower nutrient loss from steaming is the main reason I recommend it so often in the recipes. I just can’t think of any valid reason to expose a food to high heat and boiling water for any prolonged period of time.

Here are some questions I have received from readers of www.whfoods.org about How to Preserve Nutrients When Cooking.

A One of the primary reasons for the change in color when green vegetables are cooked is the change in chlorophyll.

Chlorophyll has a chemical structure that is quite similar to hemoglobin, which is found within our red blood cells. A basic difference is that chlorophyll contains magnesium at its center, while hemoglobin contains iron. When plants (e.g., green vegetables) are heated and/or exposed to acid, the magnesium gets removed from the center of this ring structure and replaced by an atom of hydrogen. In biochemical terms, the chlorophyll a gets turned into a molecule called pheophytin a, and the chlorophyll b gets turned into pheophytin b. With this one simple change, the color of the vegetable changes from bright green to olive-gray as the pheophytin a provides a green-gray color, and the pheophytin b provides an olive-green color. This color change is one of the reasons I have established the relatively short cooking times for green vegetables using the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods. These cooking methods are designed to preserve the unique concentrations of chlorophyll found in these vegetables.

Q If many nutrients are lost in the boiling or steaming of vegetables, is pouring the remaining liquid into a glass and drinking it a good idea?

A Using the water in which vegetables have been steamed or boiled is a excellent idea! Broths of this kind are a great way to salvage nutrients, especially minerals that would otherwise be lost. Covering vegetables while steaming (or a soup while cooking), instead of open-top simmering, can help retain more of the water-soluble nutrients in the cooking water.

When you boil or steam vegetables, not all of the lost nutrients end up in the water. Some evaporate into the air, and some are changed in form so that they no longer have their same health-supportive properties. But many of the lost nutrients do end up in the water, so keeping and consuming the water is definitely worthwhile.

There are exceptions, though. I would not use the cooking water from spinach, Swiss chard or beet greens, because these vegetables are high in bitter-tasting acids (including oxalic acid), that will have been extracted to the water in which they were boiled or steamed.

Q Is the nutritional value of protein lost through cooking and storing of food just as vitamins are lost? For example, is the protein value still good in cooked fish that has been stored in the refrigerator for two days?

A Proteins are not lost during cooking as easily as vitamins; however, overcooking and cooking at extremely high temperatures will denature proteins found in food. When cooked or agitated (as occurs when egg whites are beaten), proteins undergo physical changes called denaturation and coagulation. Denaturation changes the shape of the protein, thereby decreasing the solubility of the protein molecule. Coagulation causes protein molecules to clump together, as occurs when making scrambled eggs. Overcooking foods containing protein can destroy heat-sensitive amino acids (for example, lysine) or make the protein resistant to digestive enzymes. Refrigerating cooked foods will not further denature the proteins.

Q When I pickle or marinate vegetables at home, do they lose nutrients to the pickling liquid?

A Some nutrient loss occurs when you pickle or marinate vegetables. The exact nutrients that are lost and the exact percentage depends on (1) the liquids you use to pickle and marinate and (2) the length of time you keep the vegetables in the solution before consuming them. A certain percentage of some water-soluble nutrients, like vitamin C, can naturally transfer to the pickling liquid over time.

For example, 80 calories of fresh cucumber contain about 30 mg of vitamin C while 80 calories worth of pickled cucumber contains about 20 mg, for a loss of about 33%. Pickled cucumbers also lose 40–50% of their folic acid. Many of the minerals in cucumber are contained in the skins, so keeping the skins on when pickling would be important if you wanted to maintain the mineral content. (Of course, I would highly recommend organic cucumbers, especially when leaving on the skins, since it’s the skin that gets the most exposure to potentially toxic sprays.)

I don’t object to the pickling of vegetables and think they definitely can have a place in your “Healthiest Way of Eating.” However, I do see them as significantly different (in terms of nutritional value) from both raw vegetables and minimally steamed or sautéed vegetables.

Q Are vitamins like vitamin C completely destroyed when these vegetables are cooked?

A In general, cooking does reduce the amount of nutrients in food, although while they may be reduced, they will not necessarily be completely destroyed. The amount of nutrient loss will be affected by a few factors including heat, time and the amount of water. For example, cooking of vegetables and fruits for longer periods of time (10–20 minutes) can result in a loss of over 50% of the total vitamin C content. The nutrient loss that can occur with cooking is the reason that I emphasize short cooking times with minimal exposure to water. These cooking methods help to create vegetables that have enhanced taste and texture and the best preserved nutrient content.

Food companies have come a long way in their ability to improve the properties of vegetable oils at the manufacturing level. There are refined and conditioned oils in the marketplace, including oils from plant hybrids that are high in certain types of fat such as monounsaturated fatty acids, which are less susceptible to damage from heating (high-oleic safflower oil is one example). If you are going to cook with oils, your best bet are these organically produced, high quality oils that have been specifically adapted for use in high heat cooking or oils that have naturally high smoke points, like avocado oil. But I believe you have an even better option—cooking without oils!

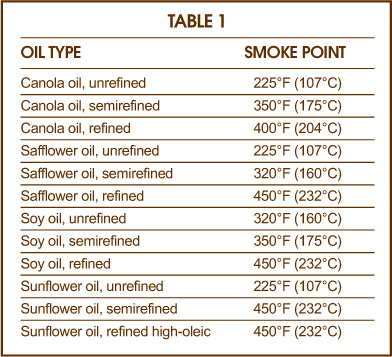

When you heat a highly unsaturated oil like safflower or sunflower oil, it will start to smoke at a fairly low heat—in the vicinity of 225°F (107°C); this is called its smoke point. When manufacturers refine these oils, they can increase the smoke point by about 100–125°F (38–52°C). In the case of refined safflower or sunflower oil, the heated oils won’t smoke until about 325–350°F (163–175°C).

With a monounsaturated oil like canola oil, however, refinement can raise the smoke point to about 400°F (204°C). Manufacturers of extra virgin olive oil claim smoke points of anywhere from 200°F (93°C) to 405°F (207°C), depending on the degree of refinement and original condition of the oil. Refined avocado oil—an oil that is naturally 12% saturated and 72% monounsaturated—has one of the highest smoke points of all vegetable oils at 520°F (271°C).

When you heat an oil to its smoke point, you have definitely inflicted a good bit of damage to the oil. This damage comes in several form.

• Heating causes loss of available nutrients contained in oils, including fat-soluble vitamins like vitamin E and the phytonutrients that give oils their characteristic colors, smells and flavors.

• Heating oils can cause the formation of free radicals, highly reactive molecules that can damage the oil further by triggering unwanted oxidative reactions. Oil manufacturers actually assign a value (called a peroxide value, or PV) to the oils based on the amount of oxidative reactions occurring.

• Formation of unwanted aromatic substances (like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs) in the oil that can increase our risk of chronic health problems including cancer.

The smoke point is a natural property of unrefined oils, reflecting their chemical composition. When oil is refined, the process increases the oil’s smoke point; in fact, raising the smoke point is one of the reasons why the refining process is used. To get a better idea of how refining increases the smoke point of oil, look at Table 1 on the next page, which shows several examples.

You will see various types of olive oil on the market:

• EXTRA VIRGIN: derived from the first pressing of the olives and has the lowest acidity level.

• FINE VIRGIN: also created from the first pressing of the olives, but it has an acidity level more than double that of extra virgin oil.

• REFINED: unlike extra-virgin and fine virgin olive oils, which only use mechanical means to press the oil, refined oil is created by using chemicals to extract the oil from the olives.

• PURE: a bit of a misnomer, it indicates oil that is a blend of refined and virgin olive oils.

Unlike the information presented in Table 1, the information on olive oil’s smoke points is, unfortunately, not very clear or consistent since different companies list different smoke points for their olive oil products; this variability most likely reflects differences in degree of processing.

Generally, the smoke point of olive oil falls in the range of 220–437°F (104–225°C). Most commercial producers list their pure olive smoke points in the range of 425–450°F (218–232°C), while “light” olive oil products—which have undergone more processing—are listed at 468°F (242°C). Manufacturers of extra virgin oil list their smoke points in a range that starts just under 200°F (93°C) and extends all the way up to 406°F (208°C). Again, the variability here is great and most likely reflects differences in the degree of processing.

In principle, organic, unrefined, cold-pressed extra virgin olive oil should have the lowest smoke point of all forms of olive oil since it is the least refined and most nutrient-rich, containing the largest concentration of fragile nutritive components. For a natural, very high-quality extra virgin olive oil, I believe the 200–250°F (93–121°C) range reflects the most likely upper limit for heating without excessive damage. In other words, this would allow the use of extra virgin olive oil for making sauces but not for 350°F (175°C) baking or higher temperature cooking.

On my last visit to Italy, I visited many homes and restaurants to find how extra virgin olive oil was used in cooking. What I found was they don’t use extra virgin olive oil for cooking; they use safflower oil or refined olive oil because of their high smoke point.

If damage to oils only occurred at smoke point, I might be more comfortable with the idea of using oils when cooking. However, oil can be damaged from heat long before its smoke point is reached. Exactly when does damage start to occur? The research is not entirely clear about this point. Very low heating of soy oil, for example, at temperatures below 160°F (71°C), does not appear to cause many oxidative reactions even if prolonged for the course of an entire day. However, 160°F (71°C) is hardly hot enough for stove-top cooking. Water boils at 212°F (100°C). Damage seems to vary between 175°F (79°C) and the oil’s smoke point—depending on the specific oil and its processing. However, even with a refined and relatively saturated oil, nutrient changes and oxidative reactions begin to occur well before the smoke point is reached.

For the reasons above, I believe it is best not to cook with heated oils. While steaming is a popular cooking method that doesn’t use oils, I have created another low-heat alternative that I call “Healthy Sauté.” This method was developed specifically to avoid unnecessary heating of vegetable oils by using broth instead of oil.

I have been using this technique for over 10 years with great results. Adding extra virgin olive oil to vegetables, sauces and soups after they have been cooked not only prevents the oil’s exposure to high heat but allows you to enjoy more of the oil’s wonderful flavor. All of the recipes in this book cook foods without the use of heated oils. I think you’ll like the results in terms of flavor as well as nourishment! (For more on “Healthy Sauté,” see page 57.)

Here are questions that I received from the readers of the whfoods.org website about oil:

Q Is oil a whole food?

A Extracting the oil from a nut or seed is a partitioning of the food. We’re dividing the food up into parts and consuming only a portion. The nut or seed from which we obtain a vegetable oil is the oil’s natural home. The oil is fragile and susceptible to damage from light, air and heat. The nut and seed protect it from these elements. The antioxidants that protect the oil from oxidation are contained within the nuts and seeds. When we extract the oil, we leave far too many of these antioxidants behind. That’s why artificial preservatives—like BHT, for example—have to be added to some vegetable oils. These oils have lost their natural antioxidant protection. High quality manufacturers do not add BHT, of course. But they still have to add something. Vitamin E is the most common high quality ingredient added back into the oil, but some companies also use extracts from thyme, rosemary or other herbs.

There are cultures throughout the world that actually rub the nuts or the seeds directly onto their heated cooking surfaces to season and lubricate these surfaces for food preparation. Technologically, they may be a step ahead of us in understanding the natural balance found in the whole food. Yet, while I always emphasize the importance of whole foods, I still think that oil can play a part in your “Healthiest Way of Eating,” as long as you use high quality, healthy oils such as organic extra virgin olive oil since it is so rich in important nutrients.

Q What is the difference between saturated versus unsaturated oils?

A The susceptibility of oil to heat damage depends in part on the nature of the oil itself. There are many types of oils, but all of them can be divided into two groups: saturated and unsaturated.

The more saturated an oil, the closer the oil gets to becoming a solid instead of a liquid at room temperature. Highly saturated oils tend to be at least “semi-solid” at room temperature. Placed into the refrigerator—where oils should be stored for long-term use—highly saturated oils become difficult to pour because they take on a more solid texture. Few vegetable oils are highly saturated. This short list primarily includes coconut oil, palm oil and palm kernel oil. (Most of the highly saturated fats come from animals instead of plants. Examples would include butter, lard, chicken fat and mutton tallow.)

At the other end of the spectrum are the highly unsaturated oils. They have many (“poly”) spots where they are unsaturated, so they are often referred to as the polyunsaturated oils. Most plant oils fall into this category including sunflower, safflower, soy, corn and cottonseed. These oils keep their liquid form even in the refrigerator. Today, a version of safflower oil is available called “high-oleic” safflower oil. (Oleic acid is a monounsaturated fatty acid, and it’s less susceptible to heat damage than the polyunsaturated fatty acids normally found in safflower oil.) This version of safflower oil can indeed withstand higher heats and is better for use with high heats than ordinary safflower oil.

In the middle are the monounsaturated oils—oils that have a little saturated fat, a little polyunsaturated fat, and a lot of the “middle ground” fat that is only moderately unsaturated. Olive oil (about 75% monounsaturated) and canola oil (about 60% monounsaturated) are the most popular oils in this category. Olive oil is sufficiently saturated (in a healthy way) to make it semi-solid in the fridge.

Q While I rarely stir-fry, when I do, I use olive oil. Is this the best choice?

A While I have included extra virgin olive oil as one of the World’s Healthiest Foods owing to its wonderful nutrition and health benefits, I don’t recommend cooking with it because heat can destroy the precious polyphenolic antioxidants it contains as well as cause potential oxidative damage to the oil.

Additionally, I purposely avoid cooking with oil in recipes because, unfortunately, any oil is going to undergo some damage during these cooking processes. However, if you are going to cook with oil, here is the approach I would recommend.

In general, oils become more susceptible to damage the more unsaturated they are in their chemical composition. A highly unsaturated oil (called a polyunsaturated oil) is more susceptible to damage than a minimally unsaturated oil (like a monounsaturated oil). Saturated fats are least susceptible to damage; however, they are not typically liquid at room temperature and not found in oil form. Butter, for example, is about two-thirds saturated and one-third monounsaturated and takes heat fairly well. Coconut oil is another example of a food that contains a high proportion of saturated fats.

Olive oil and canola oil are the most monounsaturated of the commonly used oils. Avocado oil is another primarily monounsaturated oil, although less commonly available. Olive oil is about 75% monounsaturated, and canola oil is about 60% monounsaturated. Avocado oil is about 70% monounsaturated. The problem with using olive oil in high heat situations, however, is that the beneficial polyphenols in olive oil are highly susceptible to heat damage.

Corn oil, safflower oil, sunflower oil and soy oil are all more than 50% polyunsaturated. Some companies make high-oleic versions of sunflower and safflower oil. Oleic acid is the primary monounsaturated fat found in olive oil. These high-oleic versions of polyunsaturated oils make them less susceptible to heat damage and better choices for stir-frying or sautéing.

Given the above options, it makes sense to me to go with a high-oleic version of sunflower or safflower oil when frying foods. Alternatively, you could use an oil like avocado oil that is naturally monounsaturated, has a high smoke point and may not have the same kind of polyphenol composition as olive oil, which is so sensitive to high heat.

Q Are there “good” and “bad” oils?

A While some fats are always “bad” for your health, such as those that contain trans fatty acids or high levels of saturated fats, I feel that what oftentimes makes the differentiation between “good” and “bad” is not the oil itself, but how the oil is used. Different oils have different cooking applications; an oil may be “good” if used properly but not as good if not used properly. For example, flaxseed oil is good for use in salad dressings, dips and other non-cooking applications, but it should not be heated; its fat structure is too delicate and therefore highly prone to oxidation when heated. For this reason, while flaxseed is a healthful or “good” oil when used properly, its use in a heated cooking application would be “bad.”

This rationale also holds for extra virgin olive oil, which is such a “good” oil that it is included as one of the World’s Healthiest Foods. It is rich in heart-healthy oleic acid, vitamin E and antioxidant polyphenolic phytonutrients. Yet, it is also very delicate and shouldn’t be used in cooking. Therefore, its goodness declines if it is heated, as it can oxidize and its polyphenols can degrade.

One way to therefore consider which oil is best is to think about how you will be using it. Oils that are more delicate and have a lower smoke point are best used for dressings, non-heating cooking applications or added to foods after they are cooked; those with higher smoke points can be used at different ranges of temperature. I purposely don’t cook in oil to avoid damage because, unfortunately, any oil is going to undergo some damage during these cooking processes. But if you are going to cook with oil, I would recommend higholeic versions of sunflower and safflower oil or an oil like avocado oil. Additionally, you may want to consider a high-quality coconut oil because it is highly saturated and more stable to heat; its saturated fat is mostly medium-chain fatty acids, which do not have the health drawbacks associated with long chain saturated fats, like those found in animal fats.

Q What do you think about coconut oil?

A Recent studies have supported the potential benefits of coconut oil. While it is true that coconuts contain saturated fats, it turns out that not all types of saturated fats are bad for you. Of the saturated fat found in coconut oil, only 9% is palmitic acid—the long-chain saturated fat most connected with increased risk of heart disease. Two-thirds of the fat in coconut oil falls into the category called “medium-chain” saturated fat; coconut oil contains caprylic and capric fatty acids, but more importantly, a very large amount of lauric acid, which has increasingly gained in its reputation as a heart-protective fatty acid.

In clinical healthcare, medium-chain fatty acids like the ones found in coconut have long-term and widespread use in the form of a product called MCT oil. (“MCT” stands for medium-chain triglyceride.) MCT oil has been widely used in clinical treatment of patients with digestion and absorption problems as well as other health conditions. The reason for use of MCT oil is its relative ease of digestion and absorption. About 30% of the MCT oil fats can be taken up from the digestive tract and into the blood without much metabolic work of any kind. This ease of absorption is very different from the absorption of long-chain fatty acids, which require much more processing. Since coconut oil, like MCT oil, contains a very high percentage of medium chain fatty acids, it can provide some of these same digestive benefits.

I have noticed that coconut oil is a very well promoted subject on the Internet, with many claims for its health benefits, notably for its antiviral activity. But from the research I have seen, many of these conclusions seem preliminary given that there has not been that much research published on this subject and that which has been conducted has often been done with individual fatty acid components of coconut oil (like monolaurin), not with coconut oil itself. Yet, at the moment it looks pretty good for coconuts and coconut oil in terms of the role that they can play in supporting health in general. But I will continue to look at the research results as they come in.

Unrefined coconut oil has a smoke point of about 350°F (170°C). Refined coconut oil has a smoke point of about 450°F (232°C).

Q What do you think about palm oil?

A Palm oil has received a lot of media attention, and I feel that some of the information is unclear and can cause confusion. Some of the confusion has to do with the issue of the name. There are two “palm oils”—palm fruit oil and palm kernel oil—the first may be health supportive, while the second is not.

Palm fruit oil is the oil derived from the fruit of the African palm tree (Elaeis guineensis). Extracting the oil from the palm fruit has been practiced in Africa for thousands of years. The oil, which is a richly colored red-orange, is an integral ingredient in West African cuisine. Palm kernel oil, on the other hand, is derived from the nuts of the African palm tree.

While their names are similar, and they come from the same tree, they are actually very different. Palm kernel oil contains over 80% saturated fat, while palm fruit oil contains about 50% saturated fat (45% palmitic acid and 5% stearic acid), 40% monounsaturated fat (oleic acid) and 10% polyunsaturated fat (linolenic acid). There is also another important difference between the two—palm kernel oil requires high heat and chemical extraction in its processing, while palm fruit oil is manually expressed at low temperature (usually not exceeding 100°F/38°C).

Several studies have, in fact, shown beneficial effects on cholesterol levels by including palm fruit oil in the diet. Additionally, extracts of palm fruit have been found to exert antioxidant activity. Currently, palm fruit oil is available in some natural shortening products, which can be great baking alternatives to conventional shortenings that contain trans fatty acids. However, most of the palm oil you see on the ingredient list of processed foods is palm kernel oil. This is yet another reason why it is important to carefully read food labels.

Q Are the fats in flaxseeds damaged when these seeds are included in baked goods such as breads, muffins or cereals?

A Fats (such as the omega-3s in flaxseed) do not get destroyed in baking because the water in the recipe, which boils at 212°F (100°C), keeps the fats cooler.

Q What are cold pressed oils?

A The best oils are cold pressed. The oil is obtained through pressing and grinding fruit or seeds with the use of heavy granite millstones or modern stainless steel presses, which are found in large commercial operations. Although pressing and grinding produces heat through friction, the temperature must not rise above 120°F (49°C) for any oil to be considered cold pressed. Cold pressed oils are produced at even lower temperatures. Cold pressed oils retain all of their flavor, aroma, and nutritional value. Olive, peanut and sunflower are among the oils that are obtained through cold pressing.

Q I heard that flaxseed oil taken with certain foods will enhance the value of the flaxseed oil. Is this true?

A As far as I know, the only way to naturally enhance the value of flaxseed oil would be to consume the whole flaxseed (ground) itself rather than the extracted oil. The seed contains a wider variety of nutrients than the oil, and they are uniquely combined in the seed in a natural way. I would not advise taking flaxseed oil or any oil on an empty stomach. Alongside of a balanced meal would usually be the best time to take flaxseed, although I am not aware of any special foods that could be consumed along with the oil to improve its benefits.

Q Is it better to use olive oil or corn oil for deep frying, shallow frying and making curries?

A In general, I do not recommend frying in oil. No matter what oil you use, you are going to damage some of the fatty acids in the oil. If you are going to fry, you want to use an oil that has more monounsaturated fat than usual and less polyunsaturated fat than usual. Olive oil is about 75% monounsaturated, and that would make it the better candidate based on fat quality alone. However, frying will damage the valuable polyphenols in the olive oil. Corn oil is about 61% polyunsaturated. That would make it a worse choice based on the fat content. A third possibility would be a high-oleic oil like high-oleic sunflower or safflower oil that should be better able to withstand the higher heat and does not have the same polyphenol levels as olive oil.

“Healthy Sauté,” “Healthy Steaming,” “Quick Broil,” poaching, roasting and healthiest way to grill are the healthiest methods I have found to enhance the flavor and retain the maximum number of nutrients of the World’s Healthiest Foods.

“Healthy Sauté” is a very special way of preparing foods because it has the benefits of three methods in one. It is a sauté that uses vegetable or chicken broth in place of heated oils; I am particularly conscious of creating recipes that do not use heated oils because they can potentially have negative effects on your health. It is like stir-fry because it brings out the robust flavor of foods but cooks them at a lower temperature. It is like steaming because there is enough moisture to soften the cellulose and hemicellulose, which aids digestibility. “Healthy Sauté” requires just a small amount of liquid to make vegetables moist and tender. Vegetables such as cauliflower and asparagus, which only require a small amount of liquid to tenderize them, are especially good candidates for “Healthy Sauté” because steaming and boiling dilute their flavor.

Heat broth in a stainless steel skillet. When the broth begins to steam, add vegetables and cover. Sauté for the recommended amount of time. Some vegetables require cooking uncovered for several minutes before serving. “Healthy Sauté” will concentrate both the flavor and nutrition of your vegetables.

Broth, a staple ingredient in “Healthy Sauté,” usually contains about 1% fat, which helps bring out the flavor of the food. This small amount of fat also helps coat the food and the bottom of the pan, which helps protect the food from sticking to the pan. Yet, if some sticking occurs (let’s say your “Healthy Sautéed” onions stick to the pan a little), don’t worry. Just add a little more broth to your pan and stir; it will release what little is stuck, actually adding extra flavor to your dish. If your vegetables look like they are burning, simply turn the heat down and continue to sauté.

Since the broth does not require the high heat used in stir-fry and because “Healthy Sauté” does not use heated oils, this method of cooking avoids the formation of carcinogenic compounds created when oils are heated to high temperatures. Be sure to use a stainless steel skillet when “Healthy Sautéing.”

If you do not have broth, a little hot water with a small amount of yeast extract would be a good substitute. Plain hot water also works although the broth adds a little extra flavor, and its minimal fat content helps to keep the vegetables from sticking. If you are not on an extremely salt-restrictive diet, another easy-to-make broth that I like to use and is made by adding 1 teaspoon of miso paste to 1/4 cup of warm water. Mix until it is well dissolved.

Here is a question that I received from a reader of whfoods.org about how to store broth:

Q My problem with broth is that you have to open a big can of broth in order to use a tablespoon for cooking purposes. What do you do with the rest of the can? Is there a good way to keep broth fresh for an extended period of time?

A You can make soup out of the remaining broth—just add chopped vegetables. You can transfer the rest of the broth from the open can into an airtight glass jar and keep it in the refrigerator for about five days after opening. Freezing the remaining broth in an ice cube tray is a very convenient way to use small amounts of broth as desired.

“Healthy Steaming” is one of the best cooking methods for retaining flavor and nutrients in foods. Foods simply steamed and flavored with fresh herbs, lemon and olive oil can be very satisfying and delicious, especially when the vegetables themselves have so much taste. It is also a way to cook that can be done in one pot on the stove, so there is very little mess and cleanup required.

A study published in the Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture found that light steaming was the clear winner when comparing different types of cooking methods and their effects on the retention of phytonutrients, such as carotenoids and flavonoids that act as powerful antioxidants. Light steaming resulted in almost no loss of these health-promoting minerals nutrients.

What I have gleaned from many scientific studies is that if you cook your vegetables al denté, you will maximize nutrient retention, losing only around 5–10% of vitamins, while the loss of minerals and other nutrients is even less. Overcooking can destroy more than 50% of some vegetables’ nutrients.

Even small variations in cooking techniques can affect how many nutrients you preserve. When you steam or boil vegetables, look at the color of the cooking water to see the difference in nutrient loss. The color of the water used to steam vegetables changes very little; this indicates very little nutrient loss. However, if you steam for a long time, the color of the water will deepen, reflecting the loss of a large number of nutrients.

One way to preserve water-soluble nutrients like vitamin C when steaming vegetables al denté is to make sure the water is boiling rapidly and the steam is very hot (rolling) before you put the vegetables in the steamer. The heat of the rolling steam neutralizes enzymes that can destroy vitamin C, which otherwise doesn’t stand up to heat as well as other nutrients. Up to 20% of vitamin C can be lost within the first two minutes of cooking if you’re not careful!

My “Healthy Steaming” method allows you to cook your vegetables to preserve their nutrients, bring out their color and enhance their flavor. Steaming for a minimal amount of time produces vegetables cooked al denté, crisp inside and tender outside, and is an ideal way to maximize their nutritional value. Commonly, vegetables are steamed for much too long, causing them to lose their flavor, color and nutrients. Be sure to note the time I have recommended for steaming in the recipes. Because temperatures vary on stoves, watch to make sure your vegetables are still brightly colored and a little crisp in the center when you remove them from the heat; reduce the time they are steamed if necessary.

Put 2 inches of water in the bottom of the pot. This will ensure that you will have enough water to avoid burning the pot. I am sharing this with you because I have burned many pots by using too little water trying to build up steam too quickly. It just takes a few seconds more with the extra amount of water.

In “Healthy Steaming,” you want to make sure the water is at a rapid boil before adding your vegetables to the steamer basket. This is so the heat will be consistent throughout cooking time. Steaming cooks the vegetables with even, moist heat. Once the water is at a rapid boil, turn the heat to a medium temperature and place the vegetables in the steamer basket. You want to make sure the steamer has a tight-fitting lid.

If you are “Healthy Steaming” more than one vegetable at a time, place the vegetables in the steamer basket in layers. There are two ways of doing this:

• Place all the vegetables in the steamer basket at once, putting the denser vegetables that need more heat on the bottom. Layer the vegetables, putting the lighter ones, such as greens, on top.

• Place the denser vegetables that take longer in the steamer basket and cook with the lid on for 2–4 minutes. Then add another layer of vegetables that take a little less time to cook and continue to steam. This can be done in several layers, ending up with all of your vegetables done to perfection at the end of cooking time. See Mediterranean Feast, page 277.

You can also “Healthy Steam” vegetables and fish together by steaming a variety of vegetables with a nice piece of salmon or other fish on top. You can make a simple Mediterranean dressing and drizzle it over everything when done. It is a perfect way to make a simple, healthy meal in one pot in a very short amount of time.

Remember that steam can be deceiving. It is still very hot and can burn you easily, so it is important to remember to open the lid on your steamer facing away from your body. This will prevent the steam from burning your face or arms as you lift the lid.

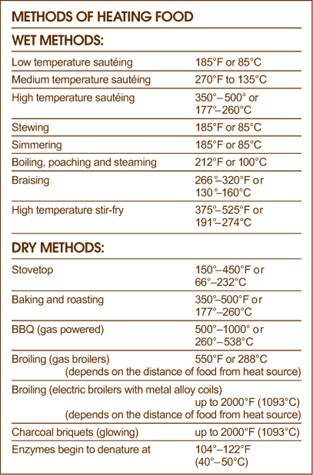

You may think of “Healthy Steaming” as a high-heat way of cooking, but in comparison to most other ways, it isn’t. Since water boils at 212°F (100°C) and transforms into steam, steam actually cooks food at a lower temperature than most oven-based and stove-top cooking methods, which range from 350°F (175°C) to 450°F (232°C). When compared with boiling, steaming is a better way of avoiding nutrient loss since the food is surrounded by water dispersed in air, rather than being completely submerged in the water itself. The decreased contact of water with the surface of the food results in decreased nutrient loss. If a food is sliced or chopped into sufficiently small sections, steaming can get it into a tender and tasty form long before most other heating methods. Even butternut squash can be steamed in less than 10 minutes.

It may sound silly, but covering the pot while “Healthy Steaming” can help preserve the nutritional quality of the food. When a pot is covered, the contact of the steam with the food is more consistent, allowing the steaming process to be completed in the least amount of time. In addition, light-sensitive nutrients—like vitamin B2—will not be leached out of the food so easily. As an added benefit, since many water-soluble nutrients pass out into the steam, if the pot is covered, they will drop back down into the water below the steamer basket. Save this water! It can be used as a base for soups and sauces or at the very minimum allowed to cool and used to water plants in the garden.

Healthy cooking methods are essential to getting all the value of the food we eat. When focusing on creating quick and easy recipes especially for the warm weather months, I have found that the “Quick Broil” method is one that I am using a lot.

To “Quick Broil,” you first want to preheat the broiler (on high). It heats up very quickly, so you don’t have to have the broiler on for very long. I place a shallow metal pan under the heat of the broiler for 10 minutes. For fish, I usually put the rack right beneath the heat. For chicken, I put the rack closer to the middle of the oven, so it doesn’t burn the top of the chicken before cooking all the way through. It is important that the pan is metal, preferably stainless steel.

Let the pan get very hot under the heat. The time of preheating the broiler and pan can be used to prepare your ingredients. Season chicken or fish with lemon juice, salt and pepper. Season red meats with salt and pepper. Once the pan is very hot, place your seasoned meat or fish on the hot pan. You do not need any oil in the pan for this cooking method. Because the pan is so hot, it immediately seals the meat on the bottom to retain the juices and keeps the meat or fish from sticking.

Return the pan with the meat or fish to under the broiler. The meat or fish is now cooking rapidly from both sides. It does not need to be turned, and it is done very quickly. For some fish fillets, the cooking time can be as quick as 1 to 2 minutes, depending on the thickness. Salmon fillets can be cooked in 5 to 7 minutes. For chicken, I have found that leaving the skin on the breast helps to keep the meat nice and juicy, and it can be cooked in as little as 15 minutes. Simply remove the skin before eating. I have found “Quick Broil” to be a very quick and healthy way of cooking meat and chicken.

Although very short cooking at 212°F (100°C) in boiling water produces relatively little nutrient loss, once boiling goes on for anything more than a few minutes, the nutrient loss becomes significant. Up to 80% of the folic acid in carrots, for example, can be lost from boiling. The same is true for the amount of vitamin B1 lost in boiled soybeans.

There are only three vegetables I recommend boiling: Swiss chard, spinach and beet greens. The reason I boil these vegetables is to help reduce their oxalic acid content. Spinach is “Quick Boiled” for only 1 minute, and Swiss chard and beet greens are boiled for only 3 minutes.

Use a large pot (3 quart) and fill it three-quarters full of water. Make sure the water is at a rapid boil before adding the greens. When the water is at full boil, place the greens into the pot. Do not cover. Cooking uncovered helps the acids escape into the air. Cook for the recommended time; begin timing as soon as you drop the greens into the boiling water. When vegetables are done, place a mesh strainer in the sink. Empty the contents of the pot into the strainer to drain the water from the vegetables.

Poaching is one of the easiest and most gentle ways of cooking fish and also provides a delicious broth that can be used for soup.

Chop onions and chop or press garlic and let them sit for 5 minutes. Place onion, garlic, celery, parsley, 4 cups cold water or broth and 1/2 tsp salt into a 2-quart pan. A few drops of sherry will also enhance the flavor. Cover and bring to a boil.

Cut fish fillets in half and place in the boiling liquid. Be sure that the fish is covered with the liquid. Lower heat to medium, cover and cook for 5 minutes depending on thickness. I love poached fish dressed with olive oil, lemon juice, garlic, and salt and pepper. For a Mediterranean flavor, I top the fish with a little chopped fresh basil, thyme or parsley.

Roasting is done with dry heat in an open pan in a hot oven, about 450°F (232°C) or higher. It crisps up the exterior of the meat or vegetables while slow cooking the inside.

Roast root vegetables at 450°F (232°C) for about 30 minutes without oil; stir once in a while to distribute natural juices. The temperature for roasting nuts is much lower—use a 160–170°F (70–75°C) oven for 15–20 minutes—to preserve the heart-healthy oils in nuts. (For instructions on Roasting Turkey, see page 585.)

Grilled foods have a unique flavor and texture and are synonymous with summertime and cooking outdoors.

• Grill on an area without a direct flame as the temperatures directly above or below the flame can reach as high as 500°F (260°C) to 1000°F (538°C).

• Be sure not to overcook or burn your food; this helps prevent the formation of toxic compounds.

• Marinate in a mixture that includes antioxidant-rich ingredients such as lemon, onions, rosemary or black pepper.

• If you do choose to grill foods and use an oil to coat them, use an oil that has a high smoke point, such as avocado oil or high-oleic safflower oil, to lessen the amount of oxidative damage that will occur in the oil itself.

The principles of nutrient loss from charcoaled or gas-grilled foods are very similar to the principles of all cook-ing: the shorter the time of exposure to heat and the lower the heat, the less the nutrient loss.

Here are some questions that I received from readers of whfoods.org about “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods.

Q Do you lose the nutritional value of food when using a pressure cooker?

A Pressure cooking—particularly when you keep the liquid when using the vegetables in a soup—can be a healthy approach to food preparation. But I believe it can be a little more difficult to avoid overcooking when pressure cooking than when steaming—and avoiding overcooking is one of my key concerns. You can usually tell by color and texture whether or not a food has been overcooked. Sometimes the difference between optimal heating and overheating is less than two minutes. Cooking at higher pressure can allow for shortening of cooking times with certain foods, such as beans.

Some nutrients become more available with light heating, and some become less. In general, however, it’s overcooking that’s the problem. Therefore, my main concern with the pressure cooker would be avoiding overcooking. If you experiment with your technique and the colors and textures of your foods are being preserved, you are probably doing a good job with your pressure cooker. If your foods are coming out discolored, limp and mushy, you are definitely losing nutrients in comparison with the light steaming technique I use for most vegetables.

Q What type of cookware should I avoid?

A First, in spite of its convenient, lightweight and break-proof nature, plastic is not a good choice for your kitchen. Very small amounts of plastic pass from the container to the food, even at refrigerator temperatures, and even when foods are not acidic. Vinyl chloride, for example, has been shown to migrate from PVC (polyvinyl chloride) water bottles into the water itself. The worst places to use plastic are in the microwave or in a pot of boiling water (for example, in the case of “boil-in-the-bag” foods). As a general rule, you are safest microwaving in unleaded ceramic or tempered glass containers (like Pyrex®) but not in plastic, even if the plastic is a harder, polycarbonate variety (number 7 on the recycling logo). Storage of food in plastic is not as much a problem as cooking in plastic, but even in this situation, glass containers with plastic lids would be safer than containers made entirely of plastic.

On the stovetop, aluminum pots and pans are the equivalent of plastic in the microwave and should be avoided. Many anodized aluminum pans look more like stainless steel than aluminum, so check to be sure. You may need to contact the store, or the manufacturer in some cases, to determine exactly what materials your pot or pan contains.

According to a 2005 report by a scientific advisory panel at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), a substance derived from Teflon® (known as PFOA) was classified as a “likely carcinogen.” This report set the basis for the EPA regulation of this product, most famous for its use as the original “non-stick” cookware surface. Teflon is relatively ubiquitous with pots, pans, woks, waffle makers, pancake griddles, deep fryers, slow cookers, bread makers, coffee makers, electric skillets, cooking utensils and hot air popcorn poppers, just a few of the kitchen items that may contain Teflon coatings. Although PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) the key susbstance found in Teflon, does not break down into PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) until a temperature of about 464°F (240°C) on the stovetop, this risk seems completely unnecessary to me and I recommend avoiding all PFTE non-stick cookware, including Teflon-coated cookware, for this reason.

The quality of the food you eat depends in part on the quality of your cookware, and high-quality meals require high-quality cookware.

Stainless steel, porcelain-coated, cast iron and tempered glass (if used on low heat to avoid damaging the glass) pots would be my first choices on the stovetop. Inside the oven, I would go with these same materials, although the rubber and plastic on lids and handles of cast-iron cookware can be a problem in the oven. Extra care must also be taken not to get burned by the hot iron. Glass, iron and porcelain ceramics consist of primarily natural substances, in stark contrast to a coating like Teflon®, which contains fluoro-carbons not formed in the natural world. With stainless steel, I do recommend careful cleaning that avoids harsh scouring, which can release too much nickel and/or chromium from the cookware.

Aluminum pots and pans clearly release aluminum into foods. Even though aluminum is very lightweight and convenient on the stovetop, and plastic is very lightweight and convenient in the microwave, I suggest you steer clear of these products. Except for convenience, there is simply no reason for you to face the potential health risks associated with migration of aluminum or plastics (like polyvinyl chloride)—even in very small amounts—from the kitchenware into your food.

In June 2005, a scientific advisory panel working at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in Washington, D.C., drafted a report that described Teflon as a “likely carcinogen” and set the basis for EPA regulation of this widely used product. In the cooking world, of course, Teflon is most famous as the original “non-stick” cookware surface, introduced into the marketplace shortly after World War II. Not only pots and pans, but also woks, waffle makers, pancake griddles, deep fryers, slow cookers, bread makers, coffee makers, non-stick rolling pins, electric skillets, cooking utensils and hot air popcorn poppers may contain Teflon coatings. So can a wide variety of other consumer products. Levi Strauss & Company even came out with a Teflon-coated version of their famous Dockers line of clothing. An estimated $40 billion dollars’ worth of Teflon-coated products has been sold worldwide.

In terms of chemistry, the health risks connected with Teflon involve two substances: polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). PTFE is the primary substance in Teflon and can basically be regarded as a plastic. PTFE will decompose under high heat, and one of the substances produced is PFOA. Toxic particles and fumes containing PFOA begin to be released from a Teflon-coated pan on a stovetop at about 464°F (240°C), according to research done by the Environmental Working Group (www.ewg.org) in 2003.

The EPA scientific advisory panel named PFOA as the likely carcinogen related to Teflon, not PTFE. For this reason, the manufacturer of Teflon, DuPont, has taken the position that no PFOA is contained in its non-stick cookware, only PTFE. This position by DuPont® has come partly in response to a $5 billion dollar class-action lawsuit filed by two Florida law firms on behalf of 14 people in 8 states who purchased and used Teflon®-coated cookware. Yet, it is important to remember that PTFE can decompose into PFOA.

There are only two essential pieces of cookware I need in my kitchen to serve one to four people using the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods. Large families will require larger size cookware.

10” Stainless Steel Skillet: For “Healthy Sauté,” poaching eggs, “Quick Broil” and roasting

3-Quart Steamer with a lid: For steaming and boiling vegetables and poaching fish

I don’t recomend collapsable steamers or bamboo steamers because you can easily burn your hands when using them, and they are hard to handle.

It is also important to have a battery-operated timer as well as a brush to clean the stainless steel pan. Cleaning the pan right after using it makes it much simpler to clean.

Battery-operated timer

Kitchen brush

Here are some questions that I received from readers of whfoods.org about cookware:

Q Does the small amount of aluminum released from an aluminum pot really make a difference?

A It depends on a person’s health status and also on a person’s philosophy of health. Healthy people can ordinarily process and get rid of small amounts of toxins they encounter. This process is called detoxification. Most healthy people could detoxify the amount of aluminum released by an aluminum pot. But an unhealthy person might not be able to do so. Would that person get immediately sick? Possibly, but probably not. Would that person be using up energy and vitamins and minerals in order to get rid of the small toxic residue? Definitely. Is it reasonable for a person to keep exposing him or herself to small amounts of toxins when those toxins could be avoided? The answer to that question really depends on your philosophy of health. Since there are many inexpensive, non-toxic alternatives to aluminum pans, I always recommend those alternatives.

Q Is cast iron cookware good for everyone?

A A hundred years ago, cast iron cookware was the most popular choice in U.S. households. This type of cookware is still an excellent choice, provided that no one in your household has excessive body stores of iron. While most U.S. adults receive too little iron from their meals and would benefit from cooking in cast iron cookware, some individuals have excessive body stores of iron and would be at risk of iron overload problems when cooking in cast iron. In general, men or postmenopausal women who consume beef on a daily basis are most likely to be at risk for iron overload problems.

Q Does seasoning my cast iron cookware with oil promote damaging free radicals to enter my body with the food?

A Unfortunately, the answer to your question is both “yes” and “no.” I’ll try to provide you with the complete context. Free radicals are highly reactive molecules that can be formed under a wide variety of circumstances. They are constantly being formed in our bodies, in the bodies of most living things, and in the atmosphere itself. Free radicals aren’t bad. They are neutral. Free radical reactions are necessary in order for life to continue. Excessive amounts of free radicals in the wrong place are the problem. Too many free radicals near a blood vessel wall can start to damage the blood vessel. Too many free radicals in the air can cause imbalances in the earth’s atmospheric gases. But the formation of free radicals is itself a natural process.

Cast iron cookware needs to be seasoned to function properly. Not only do foods stick to cast iron when it’s unseasoned, but the iron itself will leech out of the cookware more quickly. Most cast iron cookware comes with seasoning instructions. Seasoning basically involves the even application of a very light amount of oil—often less than one teaspoon—on all surfaces of the cookware, and then heating in the oven at 100–150°F (40–65°C) for 45–60 minutes. During this time, the oil seeps into the pores of the cookware and forms a protective seal. While there will be oxidation of fats during this process, the resulting coating will allow the cast iron to cook cleanly at high heats. When cast iron is properly seasoned, it needs very little oil when in use. A seasoned cast iron pot or skillet should be heated upon reuse until it begins to smoke. At that point, the surface coating of oil will have seeped back into the pores and will create an almost stick-free cooking surface.

You may have heard about the relationship between iron and free radicals. In that relationship, when too much free iron begins to accumulate in our cells, this free iron interacts with oxygen to form free radicals. Free radical formation from excess iron intake is one of the toxicity-related problems with excess iron. However, the amount of iron leeching from cast iron is not typically enough to throw a person into metabolic iron excess.

Q Are there different grades of cast iron? My aim is to have non-toxic cookware, and my budget is low. Do you know whether I can consider “cheap” cast iron safe?

A As far as safety is concerned, even “cheap” cast iron should be safe. However, there are things you might want to look for when purchasing cast iron cookware:

• Although unseasoned cast iron will be rough, it shouldn’t be uneven or bumpy.

• The roughness should be uniform and the “pores” small and fine. The finer the surface, the easier it will take the seasoning and the better it will cook. If it is unevenly rough, it will not heat and cook evenly.

• Check for ridges, pits, fine cracks, chips, seams and jagged edges.

• The color should also be uniformly gray with no discolored blotches or shadows; the color should be the same inside and out. If there is any variance in color, it means the metal wasn’t heated evenly and may break or warp.

• The bottom of a frying pan or kettle should be smooth, without ridges, to conduct the heat evenly. This is especially important if you’re going to use it on a smooth cooking surface such as an electric range.

One of the greatest insults to nourishment in our modern, fast-paced and processed food culture is the high heat at which so much of our food is cooked. We deep fat fry at 350–450°F (177–232°C); we fry on the stovetop in shortening and vegetable oils right up to their smoke points of 375–450°F (191–232°C); and we barbecue with gas grills that can reach temperatures of over 1000°F (538°C)! This exposure of food to high heat may be convenient and quick, and it may fill the air with aromas that we savor, but it comes at a definite nutritional cost. Neither the foods nor the nutrients they contain were designed to withstand extremely high temperatures. How you prepare the foods you eat can be just as important to your health as what you eat.

The problems with high-heat cooking are not restricted to the creation of toxic substances. High-heat cooking is also problematic when it comes to loss of nutrients. Virtually all nutrients in food are susceptible to damage from heat. Of course, whether a particular nutrient gets damaged depends on the exact nutrient in question, the degree of heat and the amount of cooking time. But in general, most of the temperatures we cook at in the oven (250–450°F/120–230°C) are temperatures at which substantial nutrient loss occurs, except for roasting turkey because it takes a long time for the heat to penetrate the meat and damage the nutrients. And although very short cooking at 212°F (100°C) in boiling water produces relatively little nutrient loss, once boiling goes on for anything more than a very short period of time (1–3 minutes), the nutrient loss becomes significant.

I’ve searched and searched through the nutrition research, and all of the evidence points to the same conclusion: prolonged, high-heat cooking is just not the way to go.

Sometimes scientific research just reminds us that we can trust our five senses and our own good judgment. This conclusion seems to apply to high-heat cooking. Almost always, there is some magical point at which our senses begin to dislike the result of the high heat. It may be a color change in the kale or collard greens, where the green ceases to become more and more vibrant and begins to take on a duller, grayer shade. It may be a change in air and aroma, as occurs when a vegetable oil starts to smoke. Vegetables oils have unique smoke points that can be more than 200 degrees apart, but the fact that they smoke is still a nice common-sense warning that high heat is doing some damage. If we expose foods to high heat for too long, our taste buds will also let us know.

I’ve tried to emphasize the wonderful diversity and uniqueness of food. I’ve tried to pay attention to all of the little details that make each fruit, vegetable or legume nutritionally special. It should not be surprising that specific foods within any food family must be treated just as uniquely when it comes to cooking. Nevertheless, I’ve still found it amazing just how sensitive some foods are when it comes to high heat—especially vegetables!

When it comes to vegetables, sensitivity to high heat has to be measured in a matter of minutes! In some foods, like Swiss chard, loss of vitamin C can increase by 15% in a matter of just 4–5 minutes. Swiss chard can’t be cooked as an afterthought while we are talking on the phone, setting the table or feeding the cat. Just a few minutes can change the outcome completely! Green beans will steam in about 5 minutes. During this time, their color will take on a more vibrant green hue. If you cook it longer you will notice a change in color. For example, after 7 minutes a drop in color intensity will begin to occur. By 9 or 10 minutes, the color intensity will have dropped noticeably. Just 2–3 minutes of extra steaming time can make this notable difference.

The optimal timetable for high-heat cooking will vary with a number of factors in addition to the type of vegetable. How the vegetable is sliced, for example, will change the amount of steaming it needs. Finely shredded cabbage requires less steaming (and less heat) than coarsely shredded cabbage. Because more surface of the finely shredded cabbage gets directly exposed to the steam, it takes less time for the cabbage to become tender. If you mix vegetables in the steamer basket, the topmost layers that are less directly exposed to the steam should be the vegetables needing the least steaming. The vegetables requiring longer steaming should be placed on the bottommost layer. Alternatively, vegetables that need less steaming can be added to the steamer basket later on, after the vegetables that are thicker and more dense have been added.

Nutritional research is just starting to catch up with the consequences of high-heat methods of cooking. We’ve learned, for example, that some of the most mutagenic agents formed in cooking, heterocyclic amines (HCAs), are commonly found in barbecued beef, chicken, and pork cooked at 392°F (200°C) or above. We even know what basic ingredients are required for these mutagenic agents to be produced: high temperature for more than a few minutes’ duration, free amino acids (from protein), creatine (or creatinine) and sugar. Without the high temperature component, the formation of HCAs does not occur. Direct flame grilling produces another type of carcinogen called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which might be just as harmful as the HCAs.

Researchers at Mt. Sinai Medical Hospital found that foods cooked at high temperature contain greater levels of compounds called advanced glycation end products (AGEs) that cause more tissue damage and inflammation than foods cooked at lower temperatures. AGEs irritate cells in the body, damaging tissues and increasing your risk of complications from diseases like diabetes and heart disease. These chemicals can be avoided by cooking meals at lower temperatures through “Healthy Steaming,” “Healthy Sautéing” or poaching and also by cooking meats with foods containing antioxidant bioflavonoids, such as garlic, onion and pepper.

Unfortunately, we’re not off the hook if we are vegetarian and don’t eat beef, chicken or pork. Very recent research has discovered that a potentially toxic substance called acrylamide, which is a carcinogenic nerve-damaging compound, is also formed when certain foods are cooked at high temperature. Potato chips are a key target of research interest here, as are some other foods, including flaked breakfast cereals and roasted nuts. As is the case with HCAs, acrylamide does not appear to form when high cooking temperatures are absent.

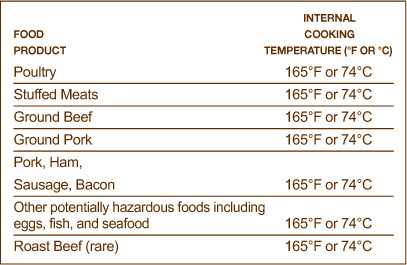

Heat is important in cooking because it can kill bacteria that can contaminate foods, especially meats and fish. The time required to kill bacteria decreases as the temperature increases. Eradication of bacteria starts at about 165°F (74°C), but as you move upward from this temperature, the time it takes to kill bacteria shortens (see table below). For some foods, like thick cuts of meat or fish, it is important to cook for however long it takes to produce a certain internal core temperature. In general, however, it takes much less than 5 minutes to kill potentially harmful bacteria on most plant foods.

The table below provides the minimum recommended intermal temperature needed to destroy harmful microorganisms in food that is cooked by conventional methods (i.e., heat source other than a microwave).

The chart below indicates the temperatures that correspond to various cooking methods.

Here are questions that I received from readers of whfoods.org about high temperature cooking:

Q What are the problems with grilling food on high heat?

A There are documented health risks associated with the char-broiling and gas grilling of foods. In general, these risks are associated with the formation of heterocyclic amines (HCAs). Most HCAs are well documented carcinogens, and keeping their levels to a minimum in your diet can decrease your cancer risk.

HCAs form most easily at high temperatures. Under 325°F, the formation of these compounds is very low. As temperatures increase above 400°F, the formation of HCAs can increase by 700%–1000%. Gas and charcoal grilling often (but not always) involve higher temperatures.