3. the best way to prepare collard greens

Whether you are going to enjoy Collard Greens raw or cooked, as a side dish or part of a main dish, I want to share with you the best way to prepare Collard Greens. Properly cleaning and cutting Collard Greens helps to ensure that the Collard Greens you serve will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

Cleaning Collard Greens

Discard damaged and discolored leaves. Rinse well under cold running water before cutting. To preserve nutrients, do not soak Collard Greens or their water-soluble nutrients will leach into the water. (For more on Washing Vegetables, see page 92.)

Cutting Collard Greens

Separating the stems from leaves and throwing the stems away was the old method of preparing Collard Greens; I encourage you to eat the stems as they are juicy, succulent and enjoyable to eat. You can cut both the stems and leaves at the same time by using one of two methods. You can either stack the leaves or roll the entire bunch of Collard Greens and then cut the leafy portion into 1/2inch slices. Cut crosswise as well. To get the best flavor and texture, it is important to cut Collard Greens into small pieces.

When you reach the point where there is no more of the leafy portion to slice and only the stems remain, begin cutting thinner slices (1/4-inch) and continue cutting to within the bottom inch of the stem; discard the last bottom inch as it is fibrous. Let sit for at least 5 minutes after cutting.

Slicing Collard Greens thin will help them to cook more quickly. The thinner you slice them, the more quickly they will cook. Cutting the stems thinner than the leaves helps them to cook at the same rate and, unless the stems are very thick, allows you to cook them together. The stems and leaves provide a good balance of flavors.

What To Do with Thick Stems

If the stem portions below the leaf are thick, you may want to cook them for 2–3 minutes before adding the leaf portion of the Collard Greens. Discard stems that are woody and hollow.

4. the healthiest way of cooking collard greens

Since research has shown that important nutrients can be lost or destroyed by the way a food is cooked, the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” Collard Greens is focused on bringing out their best flavor while maximizing retention of their vitamins, minerals and powerful antioxidants.

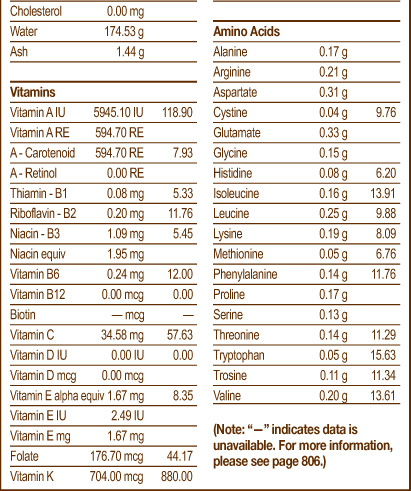

The Healthiest Way of Cooking Collard Greens: “Healthy Steaming” for Just 5 Minutes

In my search to find the healthiest way to cook Collard Greens, I tested every possible cooking method and discovered that “Healthy Steaming” for just 5 minutes delivered the best result. “Healthy Steaming” provides the moisture necessary to make Collard Greens tender and brings out their peak flavor, retains their bright color and maximizes their nutritional profile. The Step-by-Step Recipe will show you how easy it is to “Healthy Steam” Collard Greens. (For more on “Healthy Steaming,” see page 58.)

How to Avoid Overcooking Collard Greens: Cook Them Al Denté

One of the primary reasons people do not enjoy Collard Greens is because they are often overcooked. For the best flavor and texture, I recommend cooking Collard Greens al denté. Collard Greens cooked al denté are tender outside and slightly firm inside. Plus, Collard Greens cooked al denté are cooked just long enough to soften their cellulose and hemicellulose; this makes them easier to digest and allows their health-promoting nutrients to become more readily available for assimilation. Remember that testing Collard Greens with a fork is not an effective way to determine whether they are done.

Although Collard Greens are a hearty vegetable, it is very important not to overcook them. Collard Greens cooked for as little as a couple of minutes longer than al denté will begin to lose not only their texture and flavor but also their nutrients. Overcooking Collard Greens will significantly decrease their nutritional value: as much as 50% of some nutrients can be lost. (For more on Al Denté, see page 92.)

How to Prevent Strong Smells from Forming

Slicing Collard Greens thin (1/2inch) and cooking them al denté for only 5 minutes is my secret for preventing the formation of smelly compounds often associated with cooking Collard Greens. When I cook my Collard Greens, they never develop a strong smell. After 5 minutes of cooking, the texture of Collard Greens, like all other cruciferous vegetables, begins to change, becoming increasingly soft and mushy. At this point, they also start to lose more and more of their chlorophyll, causing their bright green color to fade and a brownish hue to appear. This is a sign that magnesium has been lost. This is when they start to release hydrogen sulfide, the cause of the “rotten egg smell,” which also affects their flavor. After 7 minutes of cooking, Collard Greens develop a more intense flavor, with the amount of strong smelling hydrogen sulfide doubling in quantity.

While it is important not to overcook Collard Greens, cooking for less than 5 minutes is also not recommended because it takes about 5 minutes to soften their fibers and help increase their digestibility.

Cooking Methods Not Recommended for Collard Greens

SAUTÉING”, BOILING, BAKING OR COOKING WITH OIL

You will not get good results by “Healthy Sautéing” Collard Greens. They have a low moisture content, which causes them to dry out when sautéed and become scorched before they become tender. I do not recommend boiling Collard Greens because boiling increases their water absorption causing them to become soggy and lose much of their flavor along with many of their nutrients, including minerals, water-soluble vitamins (such as C and the B-complex vitamins) and health-promoting phytonutrients. Baking Collard Greens will cause them to dry up and shrivel.

I also don’t recommend cooking Collard Greens in oil because high temperature heat can damage delicate oils and potentially create harmful free radicals.

health benefits of collard greens

Promote Optimal Health

As a Brassica vegetable, Collard Greens stand out as a food that has important health-promoting qualities. The organosulfur compounds in Collard Greens that have been the main subject of phytonutrient research are the glucosinolates and the methyl cysteine sulfoxides. Although there are over 100 different glucosinolates in plants, only 10–15 are present in Collard Greens and other Brassicas. Yet these 10–15 glucosinolates appear able to reduce the risk of a wide variety of cancers, including breast and ovarian cancers. Exactly how Collard Greens’ sulfur-containing phytonutrients prevent cancer is not clear, but several researchers point to the ability of the glucosinolates and cysteine sulfoxides to activate detoxifying enzymes in the liver that help neutralize potentially carcinogenic substances.

Promote Bone Health

If you are concerned about building or maintaining strong bones, Collard Greens are a great food for you. They are a dairy-free alternative for those seeking foods rich in calcium (they are an excellent source of this important nutrient). In addition, Collard Greens are also an excellent source of folic acid and a very good source of vitamin B6, nutrients that reduce levels of homocysteine; while homocysteine is usually associated with heart disease risk it has also been found to be damaging to bone structure as well.

Promote Antioxidant Protection

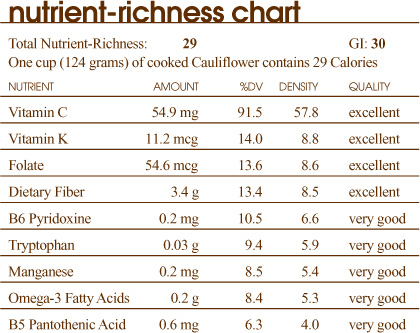

Collard Greens qualify as an excellent source of vitamin C and vitamin A (through their concentration of betacarotene) and a very good source of vitamin E. While water-soluble vitamin C protects all aqueous environments both inside and outside cells, the fat-soluble antioxidants, vitamin E and betacarotene, cover all fat-containing molecules and structures. They are also rich in manganese and zinc, two minerals that have important antioxidant properties.

Promote Vision Health

Collard Greens contain an abundance of lutein and zeaxanthin. In fact, they are the fourth most concentrated source of these carotenoids of all of the World’s Healthiest Foods. Lutein and zeaxanthin are powerful antioxidants that protect the eye from free-radical damage. Consumption of these carotenoids has been found to be associated with reduced risk of cataracts and age-related macular degeneration. Additionally, Collard Greens’ vitamin A also has vision health benefits, including promoting the eye’s adaptation to dark and light.

Additional Health-Promoting Benefits of Collard Greens

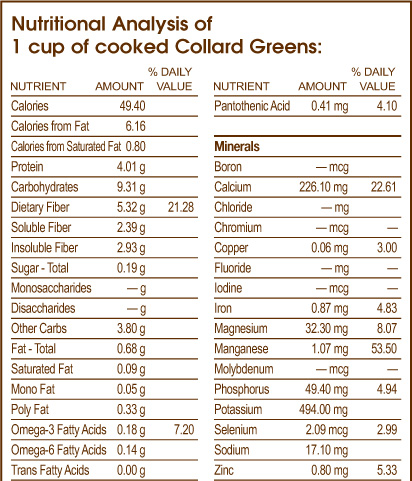

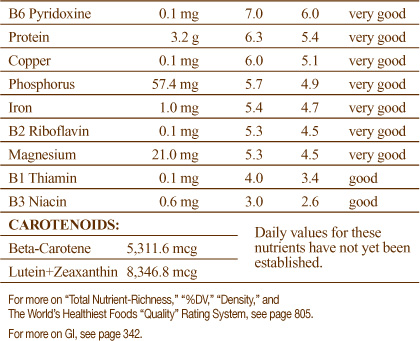

Collard Greens are also a concentrated source of many other nutrients providing additional health-promoting benefits. These nutrients include heart-healthy dietary fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, magnesium and potassium; energy-producing vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B5, niacin, phosphorus and iron; muscle-building protein; and sleep-promoting tryptophan. Since cooked Collard Greens contain only 49 calories per one cup serving, they are an ideal food for healthy weight control.

STEP-BY-STEP RECIPE

The Healthiest Way of Cooking Collard Greens

Here are questions I received from readers of the whfoods.org website about Collard Greens:

Q Is it true that eating dark green veggies such as Collards, spinach and kale will have a negative effect if you are on blood thinning medication?

A Large amounts of food high in vitamin K, such as Collards, spinach and kale, as well as other members of the Brassica family, may change the way blood thinning medications work. It is sometimes recommended to keep the amount of these foods in your diet about the same from week to week. Ask you physician whether you need to limit your intake of vitamin K-concentrated foods if you are on blood-thinning medications.

Q Can you freeze cooked Collard Greens?

A Unfortunately, unlike many other vegetables, Collard Greens do not freeze well.

Q Does cooking vegetables alter their fiber amount or structure so as to impact blood sugar levels or digestibility?

A Cooking does alter the structure of the fiber content in foods. For example, one research study found that raw carrots’ soluble fiber has higher viscosity than blanched and microwaved carrots; this may be related to the finding that the raw carrots raised blood sugar less than their cooked counterparts. The changes in their fiber content and structure may be related to your varying response to cooked and raw vegetables.

When the cells are heated up, cellulose and other substances in the cell walls soften. The vegetable cell walls eventually collapse, opening up their structure and releasing water and other substances. That is why excessive cooking makes vegetables soft and mushy; for most vegetables, this happens within 10 minutes of heating at 98°C (about 209°F, just below boiling). That is why we recommend cooking most vegetables for about 5 minutes. Properly cooking vegetables can soften the cellulose and hemicellulose fiber just enough to make them easier to digest and allow health-promoting nutrients to become more readily available for absorption.

Plants also contain starch granules inside their cells, which they use to help store energy they capture from the sun. Starch swells when cooked in water—a process which is known as “gelatinization.”

Did you know that a study presented at the 4th Annual Conference on Frontiers in Cancer Prevention Research (October 30–November 2, 2005) found that Polish women emigrating to the United States increased their risk of breast cancer by 300% once they left their native country?

And did you know that one of the most important food habits they left behind was eating cabbage? Yes, cabbage, that seemingly simple and plain-looking food that’s found so often in the form of slaw or kraut and gets so little nutritional fanfare.

Cabbage was eaten to the tune of almost 30 pounds per year by these women growing up in Poland, but its consumption dropped to less than one-third of that amount when the women emigrated to the U.S. Along with this huge drop in cabbage consumption came a very significant increase in their risk of breast cancer.

Cabbage turns out to be one of many lesser-heralded vegetables that are actually grand champions of our health. It belongs to a family known as the “cruciferous vegetables,” and you are going to hear more and more about this family in the coming years as foods that have great potential for cancer prevention and other aspects of health promotion, including balancing hormones, protecting your skin and supporting heart health.

A Diverse Family of Vegetables

You may have eaten crucifers and not even known it! This botanical family, the “cruciferous vegetables” (their name in Latin is Cruciferae or Brassicaceae), includes many shapes, colors and sizes of vegetable. It’s only when these plants go to seed and flower that you might start to notice the family resemblance because when they flower, these plants produce a four-petal, crosslike design that gives them their name: crucifer, the Latin word for “cross-bearer.”

You’ll also hear this family of vegetables commonly referred to as “the mustards” or “mustard family” because mustards also belong to the Cruciferae.

The most important genus of plants belonging to the cruciferous family are the brassicas. (The Latin word “brassica” originally comes from the Celtic word for cabbage, bresic). Like mustard, cabbage is a very popular member of the crucifers, and you may also hear this group of foods referred to as “the cabbage family.”

Here is a More Extensive List of Vegetables That Belong to This Fascinating Family of Foods:

Cress, green cabbage, Napa cabbage, red cabbage, savoy cabbage, Chinese cabbage, bok choy, daikon (Chinese radish or Japanese radish), collard greens, mustard greens, mustard seeds, rutabaga, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, kohlrabi, turnip greens, turnip root, kale, rape (the source of rapeseed and canola oil), watercress, garden cress, horseradish, wasabi (Japanese horseradish), radish, collards, mizuna and arugula.

Sulfur Compounds and Our Health

The vast majority of research studies on cruciferous vegetables have focused on the unique sulfur-containing compounds found in these foods. (Sometimes these compounds are also called “organosulfur” compounds.)

In chemical terms, the main subtypes of sulfur compounds found in cruciferous vegetables are:

• glucosinolates

• thiocyanates (including the isothiocyanates and their star molecule, sulforaphane)

• thiosulfinates and their breakdown products, including the dithiins

• sulfoxides, including the methyl cysteine sulfoxides

• a variety of other sulfur and thiol-containing compounds (the term “thiol” always means “sulfur-containing,” and you will see it included in the chemical names of many sulfur-containing substances).

Indole-3-Carbinol

There is some confusion in the popular press about one very important phytonutrient found in the cruciferous vegetables, namely, indole-3-carbinol (I3C). This substance does not contain sulfur, but it is made from the first subtype of sulfur compound mentioned above, the glucosinolates. (An enzyme called myrosinase splits off I3C from its parent compound, indole-3-glucosinolate.) So while closely related to the sulfur compounds, I3C is not technically one of them.

Prevention of breast cancer and prostate cancer has been repeatedly associated with I3C intake from cruciferous vegetables. One of the ways that it may help promote health is by beneficially supporting the metabolism of estrogen. The liver metabolizes estrogen into either 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone (16-OH) or 2-hydroxyestrogen (2-OH) with the former suggest to promote, and the latter suggested to oppose, cancer development; their ratio is used as a biomarker for the risk of developing hormone-dependent cancers such as those of the uterus and breast. I3C promotes the conversion of 2-OH and decreases the amount of 16-OH, which confers a decreased cancer risk.

There are now a few animal studies suggesting that I3C may play a role in cancer treatment as well. There is also some debate in the research as to a direct role in cancer prevention, because I3C seems to be quickly converted during the process of digestion to a doubled form of itself called diindolylmethane (DIM).

You’ll see this debate in the world of dietary supplements, but not in the world of whole natural foods. Because in the food world, when we eat broccoli and cabbage and the other crucifers, we will be exposed to both sub-stances, both the I3C during digestion, and the DIM once our stomach acids create this substance from I3C.

Interestingly, the glucosinolates that provide us with both I3C and DIM were originally called “mustard oil glucosides” because of their discovery in mustard plants. Mustard seeds (which contain mustard oil) remain an excellent source of glucosinolates.

Sulforaphane

Along with I3C, sulforaphane is one of the best-studied cancer preventive agents in the crucifers. This isothiocyanate, which seems particularly protective against stomach cancer, was first discovered in broccoli sprouts.

Sulforaphane is the compound that has recently been shown to help repair the skin damage that can be caused by excessive exposure to UV light and is likely to be protective against stomach ulcer, and perhaps stomach cancer as well.

Since sulforaphane is chemically derived from a glucosinolate (glucoraphanin), it is sometimes referred to as a glucosinolate as well as an isothiocyanate.

Methyl Cysteine Sulfoxides

While given less attention in the popular press, these sulfur-containing compounds have been carefully studied in the cruciferous vegetables, particularly in the radishes.

These compounds appear to be created most extensively during the period of plant germination, so, like sulforaphane in broccoli sprouts, they seem to be most concentrated during the radish sprouting stage. Also like sulforaphane and I3C, their intake from food has been associated with cancer prevention and is a subject of much ongoing research interest.

When It Comes to Cruciferous Vegetables, Where Should I Start?

One of the easiest, least expensive and most nutritious places to begin is with cabbage. This familiar crucifer is available in organic form in many supermarkets year-round, and when you purchase organic, you’ll not only get all of cabbage’s cancer-protective sulfur compounds, you’ll get about 40% more vitamin C and increased amounts of other vitamins and minerals as well!

Whether it’s Napa, Rainbow, Bozi cabbage in Asia, Galician cabbage in the Mediterranean, tender Savoy or just plain old “red” and “green” as many of us would describe what we see in the market, cabbage is universally available as a fresh cruciferous vegetable.

And recipes for this cancer-preventive food abound. In addition to dry krauts, sauerkrauts and slaws, cabbage is delicious in soups, healthy sautés and many “sweet and sour” dishes.

I also encourage you to treat cabbage as a “crucifer for all seasons.” In the winter and cooler months, you can take advantage of its warmth in cabbage soups—a common practice especially in many Northern European countries. In the summer and warmer months, crisp, fresh cabbage can be used as the base for a cool, refreshing salad—such as Chinese Cabbage Salad (page 224).

From a nutritional standpoint, the beauty of taking a whole, natural food like cabbage (or any of the other cruciferous vegetables) is that it provides a full spectrum of nutrients. You don’t have to worry about the difference between I3C and DIM. You can just enjoy the vibrant colors and rich flavors and be certain that your health is being optimally supported.

With the cruciferous vegetables, you also get the option of choosing from flowers and florets, leaves, stems, stalks and roots, giving you a potpourri of textures and also maximizing the dollar value of yourfood purchase.

Although research studies have confirmed the presence of sulfur-containing substances throughout these plants, you’ll definitely want to follow my specific preparation instructions to get the maximum benefit from these sulfur compounds. The steps I take you through are extremely quick and simple, and don’t require any unusual cookware or skills. (For details, see pages 222-227.)

You’ll want to avoid overcooking any of the crucifers, but light cooking, especially my easy healthy sauté and steaming techniques, will work perfectly. As long as you remember to do a good job of chewing, these vegetables will also add excellent nutritional value to raw salads and make tasty stand-alone snacks. In every case, you’ll be taking an important step toward your healthiest way of eating.

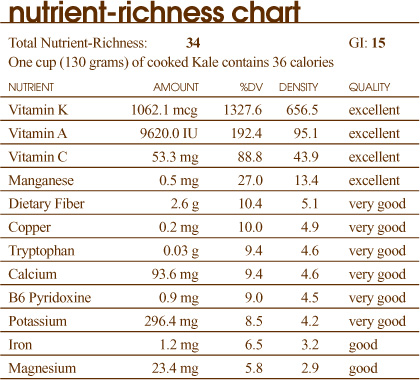

kale

highlights

Like other cruciferous vegetables, Kale is a descendent of the wild cabbage, a plant thought to have originated in Asia Minor and to have been brought to Europe around 600 BC by groups of Celtic wanderers. Both the ancient Greeks and Romans are known to have grown Kale. Although most varieties of Kale have been grown for thousands of years, there are now new varieties, such as “Lacinato” Kale, with even more robust flavor. Proper preparation is the key to enjoying the best flavor and nutritional benefits from Kale. That is why I want to share with you the secret of the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” Kale al denté. In just 5 minutes, you will be able to transform Kale into a flavorful vegetable while maximizing its nutritional value.

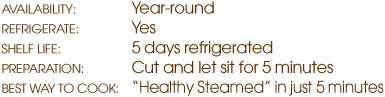

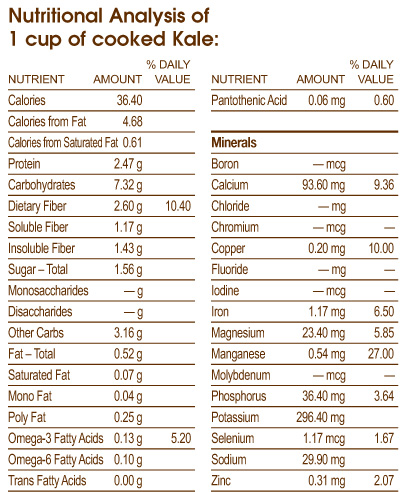

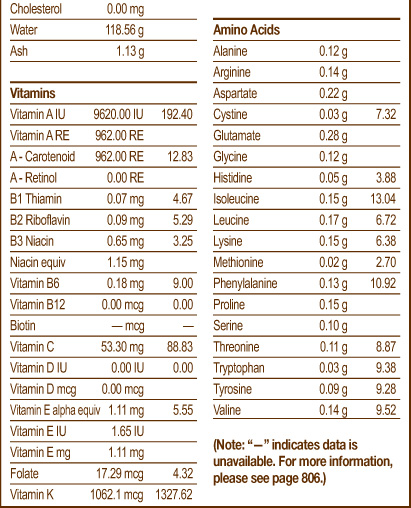

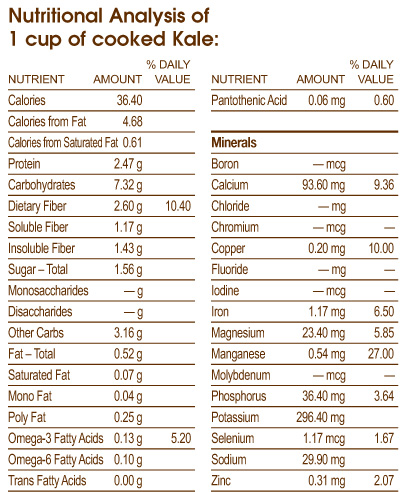

why kale should be part of your healthiest way of eating

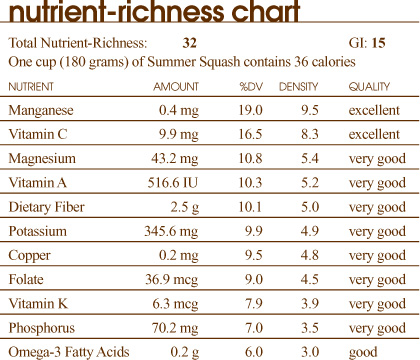

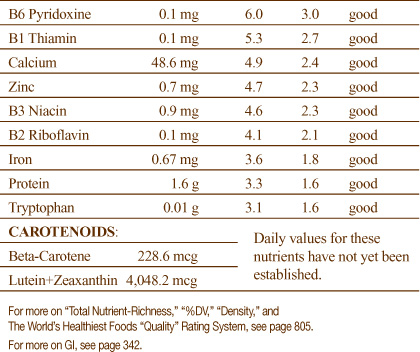

Scientific studies now show that cruciferous vegetables, like Kale, are included among the vegetables that contain the largest concentrations of health-promoting sulfur compounds, such as sulforaphane and isothiocyanates (see page 153), which increase the liver’s ability to produce enzymes that neutralize potentially toxic substances. Kale is also rich in the powerful phytonutrient antioxidants lutein and zeaxanthin, carotenoids that protect the lens of the eye. Kale is an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” not only because it is high in nutrients, but also because it is low in calories; one cup of cooked Kale contains only 36 calories, making it a great choice for weight control. (For more on the Health Benefits of Kale and a complete profile of its content of over 60 nutrients, see page 158.)

varieties of kale

Kale is a member of the cruciferous family of vegetables, which also includes broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, collard greens, mustard greens and Brussels sprouts. Its botanical name is Brassica oleracea, variety acephala, which translates to “cabbage of the vegetable garden without a head,” an appropriate description of this descendent of the wild cabbage. Kale comes in many varieties, which differ in taste, texture and appearance:

CURLY KALE

This is the variety most widely found in your local market. The frilly edged leaves and long stems come in a wide variety of colors (including green, deep blue Russian red and black) and are sold in bunches. It has a lively bitter flavor with delicious, peppery qualities. Curly Kale grown in the cold winter months is sweeter and more tender.

LACINATO

Lacinato Kale is also known as Tuscan Kale, Cavalo Nero (black cabbage) or Dinosaur Kale. It was developed in Italy in the late 19th century and features dark blue-green leaves that have an embossed texture and a slightly sweeter and more delicate flavor (with a peppery undertone) than Curly Kale.

ORNAMENTAL KALE

Originally a decorative garden plant, this variety was first cultivated commercially in the 1980s in California and is oftentimes referred to as Salad Savoy. Its leaves can be green, white or purple, and its stalks coalesce to form a loosely knit head. It has a more mellow flavor, and its texture is more tender than Curly Kale.

the peak season

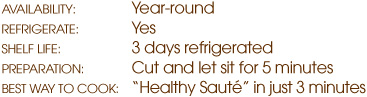

Kale is available throughout the year, but its flavor is at its peak during the cold months when the frost helps to develop a sweeter flavor and crisp texture. In hotter months, Kale is less tender and will require around 30 seconds additional cooking time.

biochemical considerations

Kale is a concentrated source of goitrogens and oxalates, which might be of concern to certain individuals. (For more on: Goitrogens, see page 721; and Oxalates, see page 725.)

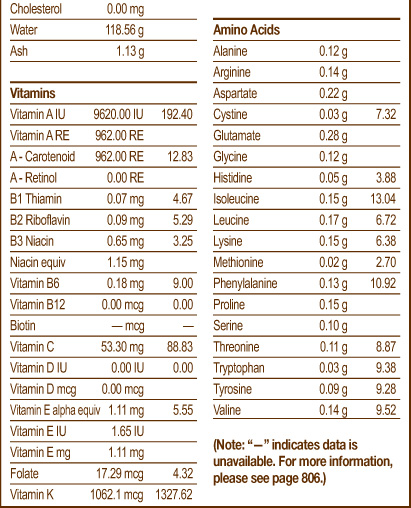

4 steps for the best tasting and most nutritious kale

Turning Kale into a flavorful dish with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 4 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

4. The Healthiest Way of Cooking

1. the best way to select kale

You can select the best tasting Kale by looking for varieties that have firm, bright, deeply colored green leaves and moist hardy stems. I have found that smaller leaves are more tender and have a milder flavor than larger leaves. By selecting the best tasting Kale, you will also enjoy Kale with the highest nutritional value. As with all vegetables, I recommend selecting organically grown varieties whenever possible. (For more on Organic Foods, see page 113.)

Avoid Kale that is wilted, shows signs of browning or yellowing, or has small holes.

2. the best way to store kale

Kale is a delicate vegetable that will become yellow and bitter if not stored properly. If you are not planning on using it immediately after bringing it home from the market, make sure to store it properly as it can lose up to 30% of some of its vitamins as well as much of its flavor.

Kale continues to respire even after it has been harvested. Slowing down the respiration rate with proper storage is the key to extending its flavor and nutritional benefits. (For a Comparison of Respiration Rates for different vegetables, see page 91.)

Kale Will Remain Fresh for Up to 5 Days When Properly Stored

1. Store Kale in the refrigerator. The colder temperature will slow the respiration rate, helping to preserve its nutrients and keeping Kale fresh for a longer period of time.

2. Place Kale in a plastic storage bag before refrigerating. I have found that it is best to wrap the bag tightly around the Kale, squeezing out as much of the air from the bag as possible.

3. Do not wash Kale before refrigeration because exposure to water will encourage Kale to spoil.

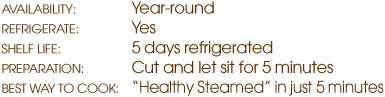

3. the best way to prepare kale

Properly cleaning and cutting Kale helps to ensure that the Kale you serve will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

Cleaning Kale

Discard damaged and discolored leaves. Rinse Kale under cold running water before cutting. To preserve nutrients, do not soak Kale or its water-soluble nutrients will leach into the water. (For more on Washing Vegetables, page 92.)

Cutting Kale

Kale’s juicy, succulent stems are rich in fiber and enjoyable to eat, which is why I offer you tips on how to prepare both the leaves and the stems. Stack the leaves, cutting the leafy portion into 1/2inch slices. When you reach the point where the leaves end and just the stems remain, make thinner slices (1/4-inch) and continue cutting to within the bottom inch of the stem; discard the last bottom inch as it is fibrous.

Slicing Kale will help it to cook more quickly. The thinner you slice it, the more quickly it will cook. Cutting the stems thinner than the leaves will help the stems and leaves cook evenly together. The combination of stems and leaves provides a good balance of flavors. After cutting, let sit for 5 minutes before cooking.

What to Do with Thick Stems

If the stem portions below the leaves are quite thick, you may want to cook them for 2–3 minutes before adding the rest of the Kale. Discard stems that are woody and hollow.

4. the healthiest way of cooking kale

Since research has shown that important nutrients can be lost or destroyed by the way a food is cooked, the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” Kale is focused on bringing out its best flavor while maximizing its vitamins, minerals and powerful antioxidants.

The Healthiest Way of Cooking Kale: “Healthy Steaming” for just 5 Minutes

In my search to find the healthiest way to cook Kale, I tested every possible cooking method and discovered that “Healthy Steaming” Kale for just 5 minutes delivered the best result. “Healthy Steaming” provides the moisture necessary to make Kale tender, bring out its peak flavor, retain its bright green color and maximize its nutritional profile. While it is important not to overcook Kale, cooking for less than 5 minutes is also not recommended because it takes about 5 minutes to soften its fibers and help increase its digestibility. The Step-by-Step Recipe will show you how easy it is to “Healthy Steam” Kale.

How to Avoid Overcooking Kale: Cook it Al Denté

One of the primary reasons people do not enjoy Kale is because it is often overcooked. For the best flavor, I recommend that you cook Kale al denté. Kale cooked al denté is tender outside and slightly firm inside. Plus, Kale cooked al denté is cooked just long enough to soften its cellulose and hemicellulose fiber; this makes it easier to digest and allows its health-promoting nutrients to become more readily available for absorption. Remember that testing Kale with a fork is not an effective way to determine whether it is done.

Although Kale is a hearty vegetable, it is very important not to overcook it. Kale cooked for as little as a couple of minutes longer than al denté will begin to lose not only its texture and flavor but also its nutrients. Overcooking Kale will significantly decrease its nutritional value: as much as 50% of some nutrients can be lost. (For more on Al Denté, see page 92.)

How to Prevent Strong Smells from Forming

Slicing Kale thin (1/2inch slices) and cooking it al denté is my secret for preventing the formation of smelly compounds often associated with cooking Kale. When I cook my Kale, it never develops a strong smell. After 5 minutes of cooking, the texture of Kale, like all other cruciferous vegetables, begins to change, becoming increasingly soft and mushy. At this point, it also starts to lose more and more of its chlorophyll, causing its rich green color to fade and a brownish hue to appear. This is a sign that magnesium has been lost. This is when it starts to release hydrogen sulfide, the cause of the “rotten egg smell,” which also affects the flavor. After 7 minutes of cooking, Kale develops a more intense flavor, with the amount of strong smelling hydrogen sulfide doubling in quantity.

Cooking Methods Not Recommended for Kale

SAUTÉING, BOILING, BAKING OR COOKING WITH OIL

You will not get good results by “Healthy Sautéing” Kale. Kale has a low moisture content, which causes it to dry out when sautéed, so it will become scorched before it becomes tender. Boiling Kale increases its water absorption, causing it to become soggy and lose much of its flavor along with many of its nutrients, including minerals, water-soluble vitamins (such as C and the B-complex vitamins) and health-promoting phytonutrients. I also don’t recommend cooking Kale in oil because high temperature heat can damage delicate oils and create harmful free radicals.

Here is a question that I received from a reader of the whfoods.org website about Kale:

Q Can Kale be frozen?

A Unfortunately, unlike other vegetables, fresh Kale does not freeze well. Yet, if you have prepared a Kale recipe, you can freeze it in an airtight container. It may not taste as fresh as it was when originally prepared, but at least you will still be able to enjoy it at a later date.

health benefits of kale

Promotes Optimal Health

As a Brassica vegetable, Kale stands out as a food that may protect against cancer. Its organosulfur phytonutrient compounds, including the glucosinolates and the methyl cysteine sulfoxides, have been the main subject of Brassica vegetable research. Exactly how Kale’s sulfur-containing phytonutrients prevent cancer is not clear, but several researchers point to the ability of these compounds to activate detoxifying enzymes in the liver that help neutralize potentially carcinogenic substances. For example, scientists have found that sulforaphane, a potent glucosinolate phytonutrient found in Kale and other Brassica vegetables, boosts the body’s detoxification enzymes, possibly by altering gene expression, thus helping to clear potentially carcinogenic substances more quickly.

Promotes Vision Health

Kale is the most concentrated source of the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin of all of the World’s Healthiest Foods. These carotenoids act like sunglasses, filtering ultraviolet light and preventing damage to the eyes from excessive exposure to it. Studies have shown the protective effect of these nutrients against the risk of cataracts. In one study, people who had a diet history of eating lutein-rich foods like Kale had a 50% lower risk for new cataracts. Kale is also an excellent source of vitamin A, notably through its rich supply of betacarotene. Vitamin A is also very important to promoting optimal vision health.

Promotes Antioxidant Protection

In addition to being a rich source of the antioxidants lutein, zeaxanthin and betacarotene, Kale is also an excellent source of vitamin C, the body’s primary water-soluble antioxidant. Vitamin C can disarm free radicals and prevent damage in the aqueous environment both inside and outside cells. It helps protect many different bodily components from oxidative damage including our DNA as well as our cholesterol (oxidized cholesterol can lead to atherosclerosis). In addition, vitamin C helps to keep our immune system strong.

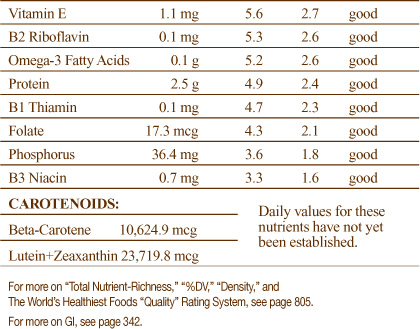

Additional Health-Promoting Benefits of Kale

Kale is a concentrated source of many other nutrients providing additional health promoting benefits. These nutrients include free-radical-scavenging manganese and copper; heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids, dietary fiber, folic acid, vitamin B6, vitamin E and potassium; bone-building calcium, magnesium and phosphorus; energy-producing iron, vitamin B1, vitamin B2 and niacin; muscle-building protein; and sleep-promoting tryptophan. Since Kale contains only 36 calories per one cup serving, it is an ideal food for healthy weight control.

STEP-BY-STEP RECIPE

The Healthiest Way of Cooking Kale

When you compare fruits and vegetables on a nutritional basis, there is no question that vegetables are more nutrient-rich and contain a much wider variety of nutrients than fruits. If you think about the lives of the plants, this difference makes sense. In the world of vegetables, we eat many parts of the plants that either grow very close to the soil (like stems and stalks) or beneath the ground itself (like roots). This closeness to the soil brings the plant into contact with the diversity of soil minerals, and almost all vegetables are richer in minerals than fruits for this reason. Fruits are also more of an end-stage occurrence: in the case of an apple tree, for example, the tree has already lived and developed for a good number of years before it produces a significant amount of edible fruit. Unlike a root, which is in charge of nutrient delivery from the soil up into the rest of the plant, the fruit—like an apple—is not nearly as active in supporting the life of the plant (although its seeds are dramatically important in allowing the tree to produce new offspring and create future generations of apple trees). Because the stems, stalks and roots are more involved in the plant’s life support, they also tend to have a greater variety of vitamins, especially B-complex vitamins, than fruits.

Most fruits have a concentrated amount of sugar, and for this reason, are higher in calories and less nutrient-rich than most vegetables. Starchy root vegetables like potatoes are closer to fruits in calorie content, but green leafy vegetables are enormously lower in calories and greater in nutrient-richness.

In summary, if you had to choose between fruits and vegetables as a foundation for your health, you would do best to select vegetables because of their greater nutrient diversity and nutrient-richness. Luckily, however, it is not an either-or situation, and you can take pleasure in the delights of both fruits and vegetables while increasing your reliance on the World’s Healthiest Foods!

Bitter, a characteristic also known as pungent, is one of our four basic tastes (along with sweet, salty, and sour). We have between 20,000 and 50,000 taste buds on our tongue, and some of these taste buds—especially the ones across the back of the tongue—have receptors for bitter taste. A bitter taste can function like a warning signal and help prevent us from eating foods that would be toxic to us. But bitter foods can also be good for us.

The reason some vegetables have a bitter taste does not mean that there is anything wrong with them. Bitterness can represent something natural and healthy, and bitter vegetables can be a great addition to your “Healthiest Way of Eating”! For example, many of the health-promoting phytonutrients that act as powerful antioxidants (including glucopyranosides like salicins, some flavonoids and polyphenols) can add a bitter flavor to your vegetables. Most vegetables contain antioxidant nutrients, and most of these antioxidant nutrients are bitter.

Fresh raw vegetables are rarely bitter. Sometimes the bitter flavor of some vegetables is developed with prolonged cooking. This is the reason I recommend steaming or sautéing your vegetables, methods that cook your vegetables very quickly.

Some vegetable flavors intensify when they are overcooked. More than likely one of the reasons that the Chinese eat more vegetables than Americans is because they cook them very lightly, and doing so makes them much more enjoyable. When you overcook vegetables, they can become mushy, lose their enjoyable flavors and may become undesirably bitter. Cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts and especially mustard greens are good examples how overcooking your vegetables can make them more bitter. Although mustard greens are bitter even when they are raw, overcooking will add to their bitter taste. When cruciferous vegetables are overcooked, they begin to produce sulfur compounds and emit that rotten egg smell that is closely associated with an increasingly bitter flavor.

Here are some suggestions for the 30% of the population who can’t tolerate the bitter taste of vegetables:

Young Vegetables are Less Bitter

Young vegetables are less bitter and, because they are more tender, require less cooking. Baby bok choy, baby eggplant, baby spinach, baby squash and baby carrots are examples of very young vegetables that are rarely bitter. (Most of the bagged baby carrots sold in markets are not actually baby carrots but are formed to look like baby carrots. Baby carrots can be identified since they are usually sold with their tops on.) But remember that while young vegetables are less bitter, they are also less nutritious because young vegetables are not developed fully, and they have not yet reached their peak nutritional value. Restaurants solve the bitter problem by serving baby vegetables.

Select the Right Dressing

Selecting a dressing that satisfies your personal taste can help mellow the bitter taste of your vegetables. I have found that using dressing with extra virgin olive oil is the best way to blend the rich taste of vegetables. Olive oil makes your vegetables tasty and satisfying, especially when the olive oil binds with the flavors of lemon, garlic, salt and pepper in the favorite Mediterranean tradition. In my experience, tamari (soy sauce) also tames a bitter taste. Adding a few drops of tamari to your vegetables, especially cruciferous vegetables, gives them a mellow, sweeter flavor.

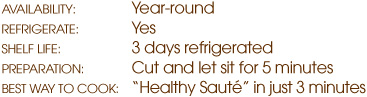

mustard greens

highlights

Spunky and soulful, Mustard Greens are native to Asia and are pungent members of the cruciferous family of vegetables with a very intense flavor. Brown seeds from this plant are used to make the condiment mustard.

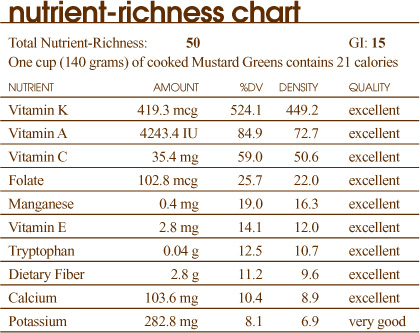

why mustard greens should be part of your healthiest way of eating

Scientific studies now show that cruciferous vegetables, like Mustard Greens, are included among the vegetables that contain the largest concentrations of health-promoting sulfur compounds, such as glucosinolates and isothiocyanates (see page 153); these phytonutrients increase the liver’s ability to produce enzymes that neutralize potentially toxic substances. Mustard Greens are also rich in the powerful phytonutrient antioxidants lutein and zeaxanthin, carotenoids that are concentrated in the lens of the eye.

varieties of mustard greens

Mustard Greens are a member of the cruciferous family of vegetables, which also includes broccoli, cauliflower, kale, collard greens, cabbage and Brussels sprouts, and are well-known for their many health-promoting properties. Mustard Greens are the leaves of the mustard plant, Brassica juncea. Mizuna is a Japanese Mustard Green with a jagged edge, green leaves and a mild peppery flavor. It is a popular salad green.

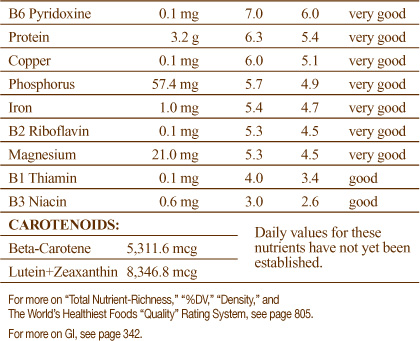

the peak season available year-round.

biochemical considerations

Mustard Greens contain goitrogens and oxalates, which might be of concern to certain individuals. (For more on Goitrogens, see page 721; and Oxalates, see page 725.)

STEP-BY-STEP RECIPE

The Healthiest Way of Cooking Mustard Greens

tomatoes

highlights

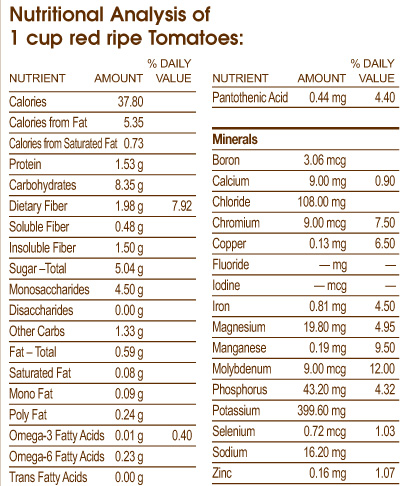

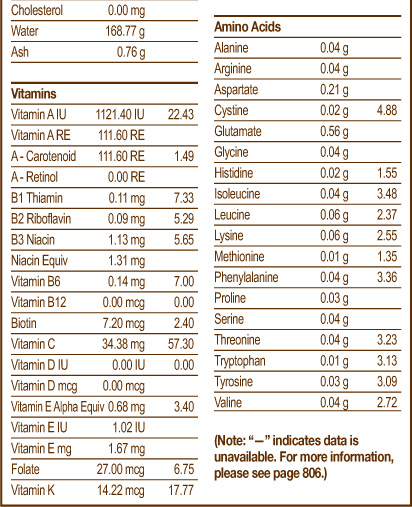

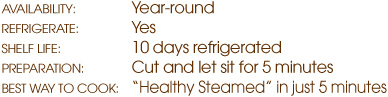

Are Tomatoes really a vegetable or are they a fruit? The confusion arises from the fact that although Tomatoes are typically enjoyed as a vegetable, botanically they are classified as a fruit. Historically, this question caused such controversy due to a tariff dispute (different tariffs were imposed on fruits versus vegetables) that it finally took a decision by the United States Supreme Court in 1893 to declare that Tomatoes would be officially considered a vegetable! While fresh raw Tomatoes are nutritious favorites in green salads and sandwiches, scientific research is now discovering that you may derive even more health benefits from Tomatoes by enjoying them cooked. That is why I want to share with you a quick and easy way to prepare Tomatoes. By using the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” Tomatoes, you can maximize the availability of their important carotenoids and enhance their flavor in just 5 minutes!

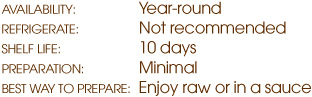

why tomatoes should be part of your healthiest way of eating

Tomatoes contain health-promoting carotenoid phytonutrients, including betacarotene, lutein, zeaxanthin and lycopene, which provide antioxidant protection. In the area of food and phytonutrient research over the last five years, few nutrients have received as much attention as lycopene. While lycopene has been found to protect cells, DNA and LDL cholesterol from oxidation, as well as provide Tomatoes with their brilliant red color, it is the synergy of the entire complement of nutrients found in Tomatoes that provides them with their optimal health-promoting benefits. Additionally, they are an excellent source of both vitamins A (because of their carotenoids) and C, powerful antioxidants that provide anti-inflammatory protection and neutralize free radicals that damage cells.

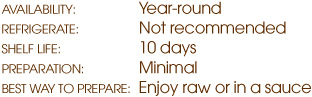

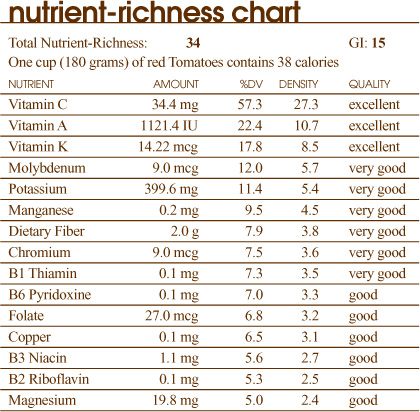

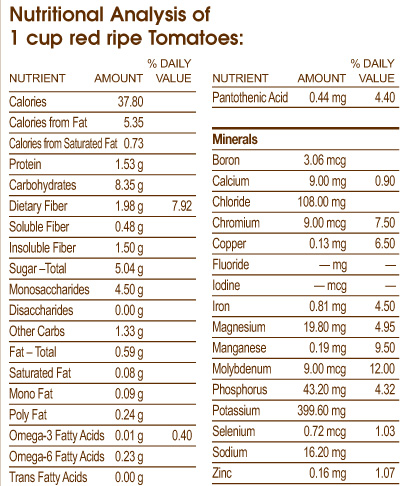

Tomatoes are an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” not only because they are high in nutrients, but also because they are low in calories: one cup of raw Tomatoes contains only 38 calories, so they are great for weight control. (For more on the Health Benefits of Tomatoes and a complete analysis of their content of over 60 nutrients, see page 168.)

varieties of tomatoes

Although Tomatoes are closely associated with Italian cuisine, they were originally native to South America. Tomatoes are members of the Solanaceae (Nightshade) family of vegetables and come in shades of red, yellow, orange, green or brown. The Tomato is the fruit of the plant Lycopersicon lycopersicum. The leaves of the plant are inedible as they contain toxic alkaloids. There are literally thousands of different varieties of Tomatoes, but those most commonly found at local markets fall into five categories:

CHERRY TOMATOES

Red, orange or yellow in color, these round, bite-sized Tomatoes are most often used in salads and as a garnish.

PLUM TOMATOES OR ROMA/ITALIAN TOMATOES

These small, red, egg-shaped Tomatoes contain less juice than slicing Tomatoes, making them an ideal choice for cooking, especially if you are making Tomato sauce.

SLICING TOMATOES

These red, round, juicy varieties are the ones most commonly found at your local market and include the flatter beefsteak Tomato. This is the variety featured in the photographs in this chapter.

HEIRLOOM TOMATOES

Although there is no standard definition for Heirloom Tomatoes, most experts consider them to be varieties that have been passed down through several generations of a family and developed to bring out their best characteristics. Besides offering a wonderful rainbow of colors, shapes and tastes in hundreds of varieties, Heirloom Tomatoes are important because they help preserve the natural biodiversity found in nature. They are soft Tomatoes with limited shelf life, so they are not generally widely distributed, but they can be found at farmer’s markets, natural food stores and supermarkets with more expansive produce sections.

GREEN TOMATOES

Green Tomatoes are unripe Tomatoes and have less nutritional value than ripe Tomatoes because the concentrations of phytonutrients that impart the red coloration to ripe Tomatoes have not yet developed.

the peak season

Although Tomatoes are available throughout the year, their peak season runs from July through October. These are the months when their concentration of nutrients and flavor are highest, and their cost is at its lowest.

biochemical considerations

Tomatoes are members of the nightshade family of vegetables, which might be of concern to certain individuals. Tomatoes are also one of the foods most commonly associated with allergic reactions and are one of the foods suspected to cause a reaction in individuals with latex allergies. (For more on: Nightshades, see page 723; Food Allergies, see page 719; and Latex Food Allergies, see page 722.)

4 steps for the best tasting and most nutritious tomatoes

Turning Tomatoes into a flavorful dish with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 4 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

4. The Healthiest Way of Cooking

1. the best way to select tomatoes

You can select the best tasting Tomatoes by looking for ones that are deeply and evenly colored as well as firm and heavy for their size. These are signs of a delicious tasting Tomato, and those with a rich red color have a greater supply of the health-promoting phytonutrient, lycopene. Tomatoes should be well shaped and smooth skinned. Ripe Tomatoes will yield to slight pressure and have a noticeably sweet smell.

It is impossible to ship fully ripened Tomatoes without damaging them; therefore, most Tomatoes are picked green and are exposed to ethylene gas to make them red after they have reached their destination. That is one more reason why Tomatoes from local farmers will usually have better flavor because they are not picked prematurely and are allowed to remain on the vine until ripe. By selecting the best tasting Tomatoes, you will enjoy Tomatoes with the highest nutritional value.

As with all vegetables, I recommend selecting organically grown varieties of Tomatoes whenever possible. Organically grown Tomatoes are not exposed to ethylene gas and are not covered with the wax coating used on conventionally grown Tomatoes to extend their shelf life. If you purchase conventionally grown Tomatoes, it is best to peel off the skin. (For more on Organic Foods, see page 113.)

Avoid pale Tomatoes with wrinkles, cracks, bruises or soft spots. I have found that ones with a puffy appearance seem to have inferior flavor and will cause excess waste during preparation.

When purchasing canned Tomatoes, it is best to purchase brands that are produced in the United States; many foreign countries do not have the same high standards for controlling the lead content of the containers. This is an especially important consideration with canned Tomatoes because their high acid content can corrode the container’s metal and result in migration of lead into the food.

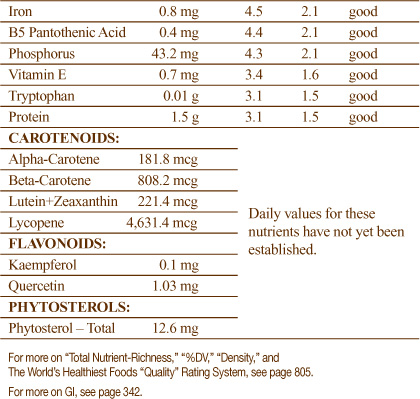

2. the best way to store tomatoes

For optimal freshness and nutrition, it is best to use Tomatoes the same day you purchase them. If you are not going to use them immediately after bringing them home from the market, be sure to store them properly as they can quickly lose their flavor as well as up to 30% of some of their vitamins.

Tomatoes continue to respire even after they have been harvested; their respiration rate at room temperature (68°F/20°C) is 35 mg/kg/hr. Slowing down the respiration rate with proper storage is the key to extending their flavor and nutritional benefits. (For a Comparison of Respiration Rates for different vegetables, see page 91.)

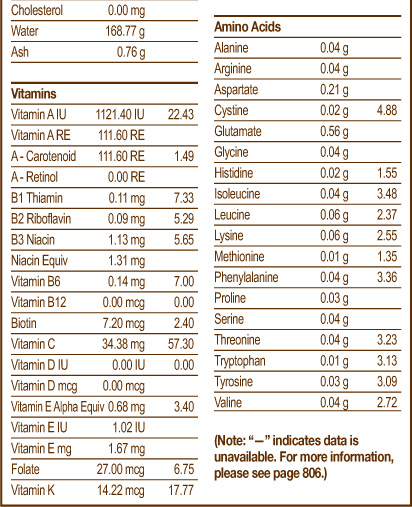

Tomatoes Will Remain Fresh for Up to 10 Days When Properly Stored

Most Tomatoes picked in the field are green, but they will continue to ripen after they are harvested. When you bring them home, it is best to store your Tomatoes at room temperature and out of direct exposure to sunlight. They will keep for up to 10 days depending upon variety and how ripe they are when purchased.

Refrigerating unripe Tomatoes will destroy their flavor and cause them to become spongy. Tomatoes are sensitive to cold; refrigeration impedes their ripening process as well as reduces their flavor by diminishing flavor components like (2)-3-dexenal.

If Tomatoes begin to become overripe at room temperature, and you are not yet ready to eat them, you can store them in the refrigerator. If possible, place them in the butter compartment, which is the warmest part of the refrigerator, where they will keep for one or two more days. Remove them from the refrigerator about 30 minutes before using them so that they can regain their maximum flavor and juiciness.

How to Store Tomatoes That Are Already Sliced

To store a Tomato that has been cut, place it in an airtight container or a storage bag, with all excess air removed from the bag, and refrigerate. Since the vitamin C content starts to quickly degrade once the Tomato has been cut, you should use it within one to two days.

How to Ripen Tomatoes

To hasten the ripening process, place Tomatoes in a paper bag with a banana or apple. The ethylene gas emitted by these fruits will help speed up the ripening process. When ripening Tomatoes, it is best to place them stem side down.

3. the best way to prepare tomatoes

Whether you are going to enjoy your Tomatoes raw or cooked, I want to share with you the best way to prepare them. Properly cleaning and cutting your Tomatoes helps to ensure that the Tomatoes you serve will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

Cleaning Tomatoes

Rinse Tomatoes well under clear running water before cutting. (See Washing Vegetables, page 92.)

Removing Pulp and Seeds

If you want to preserve the visual appeal of a broth that contains Tomatoes, remove the pulp and seeds from the Tomatoes before cooking. This will prevent the broth from turning opaque. The excess pulp can be saved to use in soup. (Details on how to remove the pulp and seeds can be found in the Step-by-Step on the bottom of page 169.)

Chopping Tomatoes

Cut the Tomato into quarters or eighths and then cut across the wedges (this can be done with or without seeds and pulp removed).

Slicing Tomatoes

With a sharp knife, cut out stem of the Tomato using a circular motion. Cut across the circumference of the Tomato into slices of desired thickness.

Peeling Tomatoes

To peel Tomatoes, plunge them into boiling water for 20–30 seconds. The peel will come off easily after you dry them.

Preparing Sun-Dried Tomatoes

Sun-dried Tomatoes have deep intense flavor but must be rehydrated before using. Place them in hot water for 10–15 minutes or until soft, or let them sit in extra virgin olive oil overnight.

4. the healthiest way of cooking tomatoes

For the best flavor, I recommend enjoying Tomatoes raw. They are a great addition to salads or sandwiches and can be used as a garnish or made into a salsa. However, studies are now finding that cooked Tomatoes can provide you with nutritional benefits not found in raw Tomatoes.

The Healthiest Way of Cooking Tomatoes: “Healthy Sautéing” for just 5 Minutes

In my search to find the healthiest way to cook Tomatoes, I tested every possible cooking method and discovered that “Healthy Sautéing” Tomatoes for just 5 minutes delivered the best result. “Healthy Sautéing” retains their bright color and maximizes their nutritional profile. (For more on “Healthy Sauté,” see page 57.)

Cooking Methods Not Recommended for Tomatoes

DON’T COOK TOMATOES WITH OIL

I don’t recommend cooking Tomatoes with oil because high temperature heat can damage delicate oils and potentially create harmful free radicals. My commitment to the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” includes avoiding the formation of free radicals whenever possible because they can cause inflammation. Adding extra virgin olive oil to Tomatoes immediately after they have been cooked is a wonderful way to enhance their flavor, as well as your absorption of their carotenoid phytonutrients, without increasing your exposure to free radicals. (For more on Why It Is Important to Cook Without Heated Oils, see page 52.)

Serving Ideas from Mediterranean Countries:

Traveling through the Mediterranean region, I found that Tomatoes were prepared in many different ways:

In Spain, gazpacho (cold Tomato soup) is their most famous cold soup.

Italians made the Tomato sauce served on pasta famous.

In France, ratatouille (Tomato and eggplant) is a favorite dish.

In Greece, besides using them raw in salads, they like to bake Tomatoes with onions.

In Turkey, they stuff Tomatoes with rice, pine nuts and cinnamon.

An Additional Way to Enjoy Cooked Tomatoes:

Quick Broiled Tomatoes: Cut Tomatoes in half horizontally. Sprinkle with fresh herbs, such as basil, oregano or parsley. Place them 5 inches from the broiler, with cut side up and broil for about 5 minutes. Tomatoes are done when they are tender, yet still holding their shape. Take care not to burn them. Drizzle with lemon, extra virgin olive oil, garlic, salt and pepper. Garnish with goat cheese.

Here is a question I received from readers of the whfoods.org website about Tomatoes:

Q Aren’t Tomatoes fruits and not vegetables, as you have them classified?

A You are correct: from a botanical perspective, Tomatoes are considered to be fruits. Yet, like other fruits that are used in savory dishes—such as avocados and bell peppers—Tomatoes are considered vegetables from a culinary perspective. When I chose to create food categorizations for the World’s Healthiest Foods, I needed to decide whether to do so based upon botanical guidelines or culinary guidelines. I chose the latter because I felt that it would be of better service to people since most people are used to thinking of food in terms of how they use it in a meal rather than in terms of scientific explanations. This is the reason that I put Tomatoes (and avocados and bell peppers) under the Vegetables category. It is also the reason that I chose to include foods such as quinoa and buckwheat, which are not botanically “grains,” in the grains section as that is the way that people think of them from a culinary perspective.

health benefits of tomatoes

Promote Antioxidant Protection

Tomatoes are extremely rich in nutrients that have antioxidant activity. They are an excellent source of vitamin C as well as vitamin A, owing to their concentration of provitamin A carotenoids such as alpha- and betacarotene. Tomatoes also contain the carotenoids lutein, zeaxanthin and lycopene. It is because of lycopene that Tomatoes have recently been gaining center stage in the nutrition research arena as it is an important antioxidant, able to protect cells, lipoproteins and DNA from oxygen damage. Yet, while lycopene is a nutritional star on its own merits, researchers are finding out that it is not lycopene alone, but the entire array of important nutrients found in Tomatoes, which delivers the incredible health protection associated with eating Tomatoes.

Promote Heart Health

More and more studies are finding that there is an important link between Tomatoes and heart health. Studies have found that regularly eating Tomatoes or Tomato-based products (including Tomato sauce/paste or ketchup) provides protection against LDL oxidation, one of the first steps in the progression of atherosclerosis, while also conferring a reduced risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD). Higher blood levels of lycopene have also been found to be protective against CVD. In addition to lycopene, Tomatoes provide numerous other heart-healthy nutrients such as betacarotene, vitamin C, potassium, folic acid, dietary fiber and vitamin B6.

Promote Optimal Health

Tomatoes may play an important role in cancer prevention. In a recent meta-analysis that combined the results of 21 studies, men consuming the highest amounts of raw Tomatoes were found to have an 11% reduction in their risk for prostate cancer, while those eating the most cooked Tomato products had a 19% reduction in prostate cancer risk. While lycopene seems to play a role in cancer prevention, including its suggested ability to activate cancer-preventive liver enzymes, researchers now believe that it is the whole array of health-promoting nutrients in Tomatoes, not just lycopene, which provides optimal cancer protection benefits.

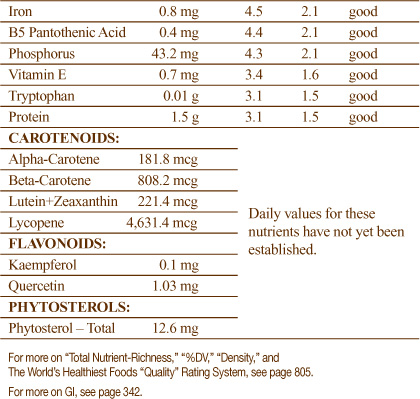

Additional Health-Promoting Benefits of Tomatoes

Tomatoes are also a concentrated source of other nutrients providing additional health-promoting benefits. These nutrients include bone-building vitamin K, magnesium and phosphorus; sulfite-detoxifying molybdenum; free-radical-scavenging manganese, copper and vitamin E; blood sugar-regulating chromium; energy-producing vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B5, niacin and iron; muscle-building protein; and sleep-promoting tryptophan. Since Tomatoes contain only 38 calories per one cup serving, they are an ideal food for healthy weight control.

STEP-BY-STEP RECIPE

The Healthiest Way of Cooking Tomatoes

Here are questions I received from readers of the whfoods.org website about Tomatoes:

Q Are Tomato skins good for you to eat? Do they provide any special benefits?

A The skins of Tomatoes are definitely good to eat. They contain many nutrients including fiber and lycopene. Additionally, Tomato skins are a concentrated source of flavonoid phytonutrients. A recent study found that 98% of flavonols—a specific type of flavonoid—contained in Tomatoes are actually found in the skin. Extracts made from Tomato skins have also been found to have anti-aller-genic properties, probably because of their concentration of another flavonoid called naringenin chalcone.

Q I keep on hearing about the health benefits of lycopene. Is lycopene the reason that Tomatoes are so good for us?

A Tomatoes have become well regarded for their concentration of lycopene, a carotenoid phytonutrient whose antioxidant strength is even greater than that of betacarotene, capable of protecting cells, cholesterol and DNA from oxidative damage. Yet, recent research has suggested that the benefits of Tomatoes may be anything but lycopene-limited. Study after study shows that intake of Tomatoes or Tomato-based foods is associated with better health status, yet the results have not been as consistent for isolated lycopene, For example, in research when animals were given either lycopene or Tomatoes, those given the whole food were found to be better protected from disease.

The Tomato-lycopene link is a great example of how whole foods may be richly endowed with a particular superstar nutrient, yet it may be the food’s whole matrix of nutrients, rather than just isolated ones, that provide the most benefit. So, the next time you think of taking lycopene supplements, you may want to add some sliced Tomatoes to your salad or sandwich instead.

Yes. Organically grown food is your best way of reducing exposure to toxins used in conventional agricultural practices. These toxins include not only pesticides, many of which have been federally classified as potential cancer-causing agents, but also heavy metals such as lead and mercury, and solvents like benzene and toluene. Minimizing exposure to these toxins is of major benefit to your health. Heavy metals damage nerve function, contribute to diseases such as multiple sclerosis, lower IQ and also block hemoglobin production, causing anemia. Solvents damage white cells, lowering the immune system’s ability to resist infections. In addition to significantly lessening your exposure to these health-robbing substances, organically grown foods have been shown to contain substantially higher levels of nutrients such as protein, vitamin C and many minerals.

How do organic foods benefit cellular health?

DNA: Eating organically grown foods may help to better sustain health since recent test tube and animal research suggests that certain agricultural chemicals used in the conventional method of growing food may have the ability to cause genetic mutations that can lead to the development of cancer. One example is penta-chlorophenol (PCP) that has been found to cause DNA fragmentation in animals.

Mitochondria: Eating organically grown foods may help to better promote cellular health since several agricultural chemicals used in the conventional growing of foods have been shown to have a negative effect upon mitochondrial function. These chemicals include paraquat, parathion, dinoseb and 2,4-D; they have been found to affect the mitochondria and cellular energy production in a variety of ways including increasing membrane permeability, which exposes the mitochondria to damaging free radicals, and inhibiting a process known as coupling that is integral to the efficient production of ATP.

Cell Membrane: Since certain agricultural chemicals may damage the structure and function of the cellular membrane, eating organically grown foods can help to protect cellular health. The insecticide endosulfan and the herbicide paraquat have been shown to oxidize lipid molecules and therefore may damage the phospholipid component of the cellular membrane. In animal studies, pesticides such as chlopyrifos, endrin and fenthion have been shown to overstimulate enzymes involved in chemical signaling, causing imbalance that has been linked to conditions such as atherosclerosis, psoriasis and inflammation.

How can organic foods contribute to children’s health?

The negative health effects of conventionally grown foods, and therefore the benefits of consuming organic foods, are not just limited to adults. In fact, many experts feel that organic foods may be of paramount importance in safeguarding the health of our children.

In two separate reports, both the Natural Resources Defense Council (1989) and the Environmental Working Group (1998) found that millions of American children are exposed to levels of pesticides through their food that surpass limits considered to be safe. Some of these pesticides are known to be neurotoxic, able to cause harm to the developing brain and nervous system. Additionally, some researchers feel that children and adolescents may be especially vulnerable to the cancer-causing effects of certain pesticides since the body is more sensitive to the impact of these materials during periods of high growth rates and breast development.

The concern for the effects of agricultural chemicals on children’s health seems so evident that the U.S. government has taken steps to protect our nation’s young. In 1996, Congress passed the Food Quality Protection Act requiring that all pesticides applied to foods be safe for infants and children.

Organic foods that are strictly controlled for substances harmful to health can play a major role in assuring the health of our children.

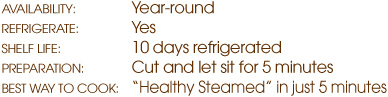

brussels sprouts

highlights

Originating in northern Europe, Brussels Sprouts were named for the capital of Belgium, where they still remain an important local crop. They were introduced to England and France in the nineteenth century, and the French who settled in Louisiana brought them to the United States.

As with all vegetables, proper preparation is the key to bringing out the best flavor and nutritional benefits from Brussels Sprouts. That is why I want to share with you the secret of the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” Brussels Sprouts al denté. Because Brussels Sprouts are such a hearty vegetable, many people have the misconception that they take a long time to prepare, but in just 5 minutes, you can bring out their best flavor, maximize their nutritional value and transform Brussels Sprouts into a flavorful vegetable you will enjoy.

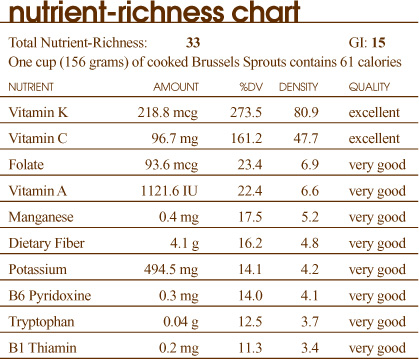

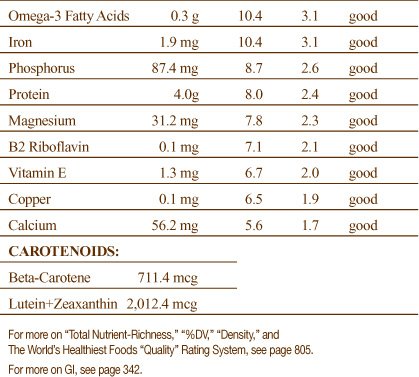

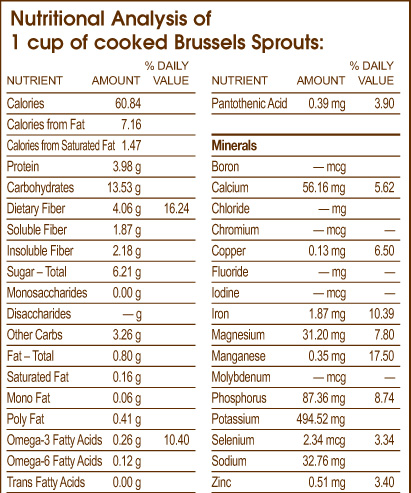

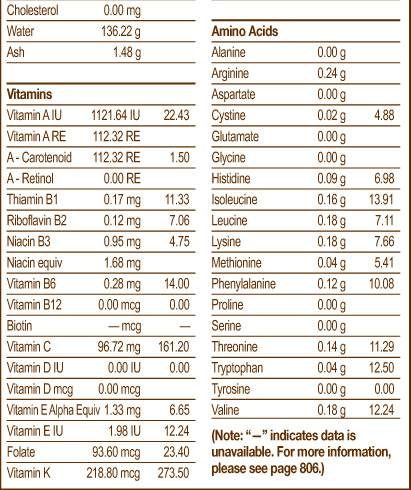

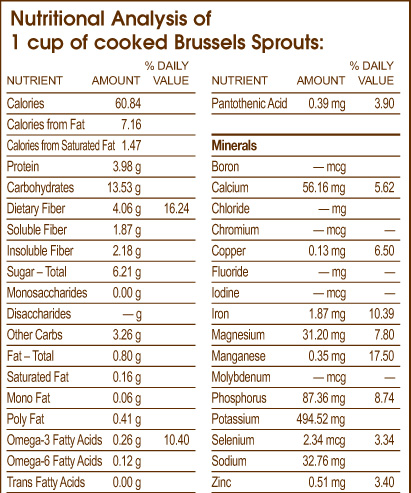

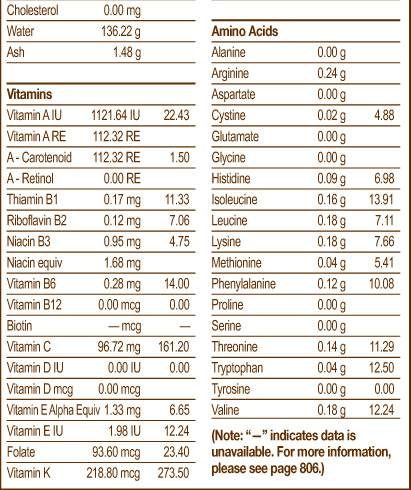

why brussels sprouts should be part of your healthiest way of eating

Although they may look like small cabbages, Brussels Sprouts are anything but small when it comes to nutritional value. Along with vitamins C, A and E, which provide powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protection, Brussels Sprouts are very rich in vitamin K and folate. Additionally, scientific studies now show that cruciferous vegetables, like Brussels Sprouts, contain large concentrations of health-promoting sulfur compounds such as glu-cosinolates and isothiocyanates (see page 153), which increase the liver’s ability to produce enzymes that neutralize potentially toxic substances. Brussels Sprouts are also rich in the powerful phytonutrient antioxidants lutein and zeaxanthin. (For more on the Health Benefits of Brussels Sprouts and a complete analysis of their content of over 60 nutrients, see page 176.)

Brussels Sprouts are an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” not only because they are high in nutrients, but also because they are low in calories: one cup of cooked Brussels Sprouts contains only 61 calories.

varieties of brussels sprouts

Brussels Sprouts are a member of the cruciferous family of vegetables which also includes broccoli, cauliflower, kale, collard greens, cabbage and mustard greens. The most popular and widely available variety of Brussels Sprouts are sage green in color. This is the variety featured in the photographs in this chapter. There are also some varieties with a red hue. Although Brussels Sprouts are usually removed from the stem and sold individually, you may occasionally find them at the market still attached to the stem.

the peak season

Brussels Sprouts are available throughout the year, but their flavor is at its peak during the cold months when the frost helps to develop a sweeter flavor. In hotter months, Brussels Sprouts are less tender and will require around 1 minute additional cooking time.

biochemical considerations

Brussels Sprouts are a concentrated source of goitrogens, which might be of concern to certain individuals. (For more on Goitrogens, see page 721.)

4 steps for the best tasting and most nutritious brussels sprouts

Turning Brussels Sprouts into a flavorful dish with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 4 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

4. The Healthiest Way of Cooking

1. the best way to select brussels sprouts

You can select the best tasting Brussels Sprouts by looking for ones that are firm and compact with a vibrant, bright green color. Since most Brussels Sprouts are sold off the stem, it is a good idea to select ones of comparable size so that they will cook in a similar amount of time. By selecting the best tasting Brussels Sprouts, you will also enjoy Brussels Sprouts with the highest nutritional value. As with all vegetables, I recommend selecting organically grown varieties of Brussels Sprouts whenever possible. (For more on Organic Foods, see page 113.)

Avoid Brussels Sprouts that are yellow or have wilted leaves. Be sure they are not puffy or soft in texture.

2. the best way to store brussels sprouts

Brussels Sprouts will turn soft, yellow and bitter if not stored properly. Make sure to store them well so that they will retain their flavor and nutrient concentrations.

Brussels Sprouts continue to respire even after they have been harvested; their respiration rate at room temperature (68°F/20°C) is 276 mg/kg/hr. Slowing down the respiration rate with proper storage is the key to extending their flavor and nutritional benefits. (For a Comparison of Respiration Rates for different vegetables, see page 91.)

Brussels Sprouts Will Remain Fresh for Up to 10 Days When Properly Stored

1. Store fresh Brussels Sprouts in the refrigerator. The colder temperature will slow the respiration rate, helping to preserve their nutrients and keeping Brussels Sprouts fresh for a longer period of time.

2. Place Brussels Sprouts in a plastic storage bag before refrigerating. I have found that it is best to wrap the bag tightly around the Brussels Sprouts, squeezing out as much of the air from the bag as possible.

3. Do not wash Brussels Sprouts before refrigeration because exposure to water will encourage Brussels Sprouts to spoil.

3. the best way to prepare brussels sprouts

Properly cleaning and cutting Brussels Sprouts helps to ensure that the Brussels Sprouts you serve will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

Cleaning Brussels Sprouts

Before washing Brussels Sprouts, remove stems and any yellow leaves. Rinse them well under cool running water. To preserve nutrients, do not soak Brussels Sprouts or the water-soluble nutrients will leach into the water. (For more on Washing Vegetables, page 92.)

Cutting Brussels Sprouts

Cutting Brussels Sprouts into equal size pieces will help them to cook more evenly. Since the smaller you cut Brussels Sprouts, the more quickly they will cook, I recommend cutting Brussels Sprouts into quarters. Cutting the Sprouts into smaller pieces helps maximize the formation of health-promoting compounds when you let them sit for at least 5 minutes before cooking.

4. the healthiest way of cooking brussels sprouts

Since research has shown that important nutrients can be lost or destroyed by the way a food is cooked, the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” Brussels Sprouts is focused on bringing out their best flavor while maximizing their vitamins, minerals and powerful antioxidants.

The Healthiest Way of Cooking Brussels Sprouts: “Healthy Steaming” for Just 5 Minutes

In my search to find the healthiest way to cook Brussels Sprouts, I tested every possible cooking method and discovered that “Healthy Steaming” for just 5 minutes produced the best result. “Healthy Steaming” provides the moisture necessary to make Brussels Sprouts tender, brings out their peak flavor, retains their bright color and maximizes their nutritional profile. The Step-by-Step Recipe will show you how easy it is to “Healthy Steam” Brussels Sprouts. (For more on “Healthy Steaming,” see page 58.)

How to Avoid Overcooking Brussels Sprouts: Cook Them Al Denté

One of the primary reasons people do not enjoy Brussels Sprouts is because they are often overcooked. For the best flavor, I recommend that you cook Brussels Sprouts al denté. Brussels Sprouts cooked al denté are tender outside and slightly firm inside. Plus, Brussels Sprouts cooked al denté are cooked just long enough to soften their cellulose and hemicellulose fiber; this makes them easier to digest and allows their health-promoting nutrients to become more readily available for assimilation.

Although Brussels Sprouts are a hearty vegetable, it is very important not to overcook them. Brussels Sprouts cooked for as little as a couple of minutes longer than al denté will begin to lose not only their texture and flavor, but also their nutrients. Overcooking Brussels Sprouts will significantly decrease their nutritional value: as much as 50% of some nutrients can be lost. (For more on Al Denté, see page 92.)

How to Prevent Strong Smells from Forming

Cutting Brussels Sprouts into quarters and cooking them al denté for only 5 minutes is my secret for preventing the formation of smelly compounds often associated with cooking Brussels Sprouts. When I cook my Brussels Sprouts, they never develop a strong smell. After 5 minutes of cooking, the texture of Brussels Sprouts, like all other cruciferous vegetables, begins to change, becoming increasingly soft and mushy. At this point, they also start to lose more and more of their chlorophyll, causing their bright green color to fade and a brownish hue to appear. This is a sign that magnesium has been lost. This is when they start to release hydrogen sulfide, the cause of the “rotten egg smell,” which also affects the flavor. After 7 minutes of cooking, Brussels Sprouts develop a more intense flavor, with the amount of strong smelling hydrogen sulfide doubling in quantity.

While it is important not to overcook Brussels Sprouts, cooking for less than 5 minutes is also not recommended, because it takes about 5 minutes to soften their fibers and help increase their digestibility.

Cooking Methods Not Recommended for Brussels Sprouts

BOILING, BAKING OR COOKING WITH OIL

Boiling Brussels Sprouts increases their water absorption causing them to become soggy and lose much of their flavor along with many of their nutrients, including minerals, water-soluble vitamins (such as C and the B-complex vitamins) and health-promoting phytonutrients. I don’t recommend baking Brussels Sprouts as they will dry up and shrivel. I also don’t recommend cooking Brussels Sprouts in oil because high temperature heat can damage delicate oils and potentially create harmful free radicals.

While blanching is often used as a preliminary step for freezing vegetables, it’s important to realize that the vegetables experience nutrient loss when blanched. Commenting on her study that found that microwaving broccoli caused a great loss in flavonoids than steaming, study co-author, Dr. Cristina Garcia-Viguera, noted that “Most of the bioactive compounds in vegetables are water-soluble; during heating, they leach in a high percentage into the cooking water. Because of this, it is recommended to cook vegetables in the minimum amount of water (as in steaming) in order to retain their nutritional benefits.” A second study, published in the same issue of the Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, provides similar evidence. In this study, Finnish researchers found that blanching vegetables prior to freezing caused losses of up to a third of their antioxidant content. Although slight further losses occurred during frozen storage, most bioactive compounds including antioxidants remained stable. The bottomline: how you prepare and cook your food may have a major impact on its nutrient-richness and blanching can lead to additional nutrient loss. While I would not say that you should never freeze your vegetables if you have an extra supply on hand, I think that this research further supports how fresh vegetables cooked in minimal amounts of time with the least amount of water exposure is the best way to prepare them with respect to retaining optimal nutrient concentrations.

health benefits of brussels sprouts

Promote Optimal Health

Plant phytonutrients found in Brussels Sprouts enhance the activity of the body’s natural defense systems to protect against disease, including cancer. Scientists have found that sulforaphane, a potent compound created in the body from the glucoraphanin phytonutrient contained in Brussels Sprouts and other Brassica family vegetables, boosts the body’s detoxification enzymes, helping to clear potentially carcinogenic substances more quickly. Sulforaphane has been found to inhibit chemically induced breast cancers in animal studies and induce colon cancer cells to commit suicide.

In addition, men who consume Brussels Sprouts have been found to have less measured DNA damage than those who do not consume any cruciferous vegetables. Reduced DNA damage may translate to a reduced risk of cancer since mutations in DNA allow cancer cells to develop. Other beneficial sulfur-containing compounds in Brussels Sprouts include indoles and isothiocyanates.

Promote Healthy Skin

Brussels Sprouts are an excellent source of vitamin C, the body’s primary water-soluble antioxidant. Vitamin C supports immune function and the manufacture of collagen, a protein that forms the ground substance of body structures including the skin, connective tissue, cartilage, and tendons. In addition, Brussels Sprouts are a very good source of vitamin A, through their concentration of betacarotene; both of these nutrients play important roles in defending the body against infection and promoting supple, glowing skin. Brussels Sprouts are also a good source of the omega-3 fatty acid, alpha-linolenic acid; among its many important functions, alpha-linolenic acid supports skin health.

Promote Digestive Health

Add Brussels Sprouts to your diet, and you’ll increase your intake of both soluble and insoluble fiber. Dietary fiber nourishes the cells lining the walls of your colon, which promotes colon health. Feeding Brussels Sprouts to research animals was found to beneficially affect their intestinal flora and the production of short chain fatty acids, both of which promote digestive heatlh.

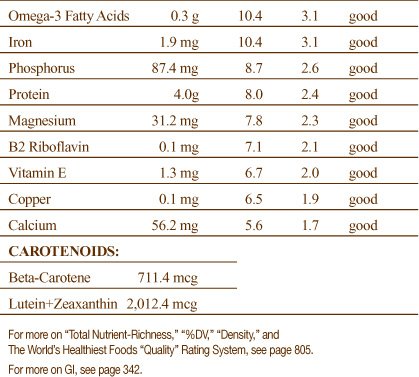

Additional Health-Promoting Benefits of Brussels Sprouts

Brussels Sprouts are also a concentrated source of many other nutrients providing additional health-promoting benefits. These nutrients include bone-building calcium, magnesium, vitamin K, copper and manganese; heart-healthy folate, vitamin B6, potassium and vitamin E; energy-producing iron, vitamin B1, vitamin B2 and phosphorus; muscle-building protein; and sleep-promoting tryptophan. Since Brussels Sprouts contain only 61 calories per serving, they are an ideal food for healthy weight control.

STEP-BY-STEP RECIPE

The Healthiest Way of Cooking Brussels Sprouts

green beans

highlights