NAME |

PAGE |

719 |

|

720 |

|

721 |

|

722 |

|

722 |

|

723 |

|

725 |

|

726 |

|

727 |

|

727 |

|

728 |

|

729 |

|

730 |

|

732 |

Have you ever noticed that there are some people who can eat just about anything and still feel great, while others may feel that their energy and vitality have just been zapped, even after eating foods that are generally considered “healthy”? For example, while I include low-fat dairy products in the list of the World’s Healthiest Foods, certain people who are lactose-intolerant need to avoid consuming these foods, while others feel great after eating them and greatly benefit from these calcium-rich foods. The reason that individuals react differently to foods and their components is because of their biochemical individuality.

While two siblings with the same parents can eat the same meals together, one may stay slim, while the other may gain weight. Even though they are eating the same foods prepared at the same time, they may have different metabolisms; while they may consume the same number of calories, their bodies don’t burn them at the same rate. The one whose body uses all the calories consumed stays slim, while the one whose body doesn’t use them all stores the extra calories as fat. Sometimes it seems that when it comes to food, one person’s “treasure” may be another’s “poison” since a food may be health promoting for one person yet depleting for another. This is because genetic and biochemical differences among individuals result in different reactions to specific foods.

One of the central tenets of the George Mateljan Foundation is to eat nutrient-rich whole foods. I also recognize that the particular foods that may be of greatest benefit to different people may vary because every person is unique in his or her genetics and biochemical individuality. So, while I have created a list of 100 foods that I have deemed the World’s Healthiest, I realize that each of these foods may not be equally beneficial for each individual.

Genetic individuality also determines the extent of the benefit that some foods can provide. For example, the extent of the benefits people derive by including flaxseeds in their “Healthiest Way of Eating” depends upon their genetic individuality. For some people, flaxseeds are a great source of a wide array of anti-inflammatory fatty acids. Yet, other people don’t have the optimal enzyme activity to properly convert the seeds’ alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) into eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), the anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids found in cold-water fish. While these people can still benefit from the many nutrients that flaxseeds have to offer, the amount of anti-inflammatory protection that they receive may be more limited. (For more on Omega-3 Fatty Acids, see page 770.)

The World’s Healthiest Foods are a compendium of 100 nutrient-rich, health-promoting whole foods; yet those that may be of highest value to you may be different than those that best support another person. It is important to recognize your own biochemical individuality and honor your uniqueness when looking for the World’s Healthiest Foods that are best for you. I have included information in the book that will help you determine which foods, if any, are not supportive of your health and help you design a healthy way of eating to better suit your individual needs.

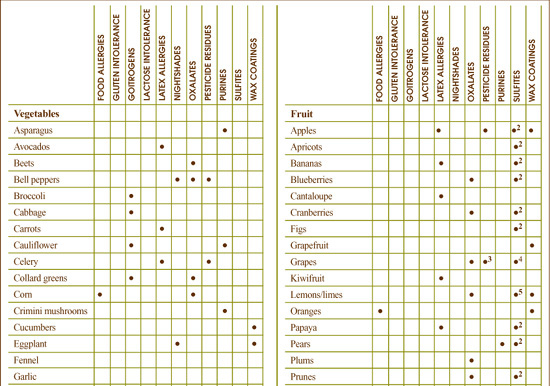

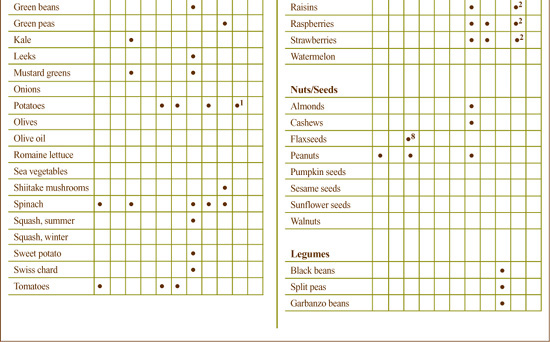

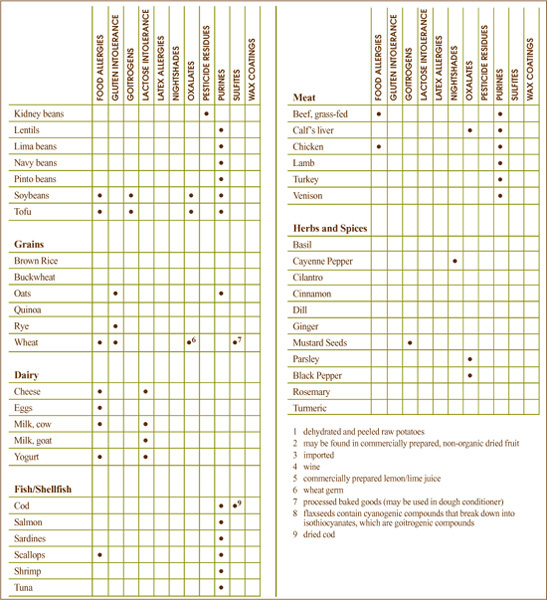

Each food chapter addresses the “Biochemical Considerations” of that particular food and includes information about whether the food is a significant source of oxalates, goitrogens, purines or other compounds that can cause challenges for individuals who have certain health concerns. Additionally, there are certain foods that are more likely to contain higher amounts of pesticide residues than others, while some foods more frequently cause allergic reactions than do others. If any of these potential concerns apply to a particular food, it is noted in that food’s chapter.

This chapter explains the different “Biochemical Considerations” referenced in the food chapters. This information can be helpful in a few different ways. For example, if you know that you need to reduce your intake of goitrogenic foods owing to a thyroid condition, you will be able to see which foods have a significant amount of goitrogenic compounds. Or if you find that celery and strawberries make you feel fatigued after you eat them, and you do not regularly purchase the organically grown varieties of these foods, the information under “Pesticide Residues” will alert you to the fact that these foods are among those with the highest pesticide residues. You may then want to consider whether your body is reacting to the pesticide residues that remain on conventionally grown foods.

Biochemical Individuality helps us to understand why some individuals are sensitive to some foods, while others are not. It is possible to be sensitive to any food, and it is estimated that 60–70% of people are sensitive to one or more foods cited in the next column. People often believe that if they are not diagnosed as having a food allergy for a particular food then it is safe for them to eat that food; however, unlike food allergies, food sensitivities are not mediated by the immune system and cannot be detected through clinical analysis. Sensitivities to foods can involve many different physiological mechanisms, which is why the prevalence is higher than that cited for food allergies as discussed in the next section. For example, it is possible to have a sensitivity to milk and not be allergic to milk. As it turns out, even some of the World’s Healthiest Foods can be problematic for some individuals. These include:

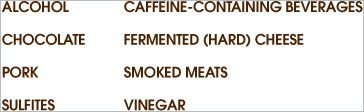

Other foods not included among the World’s Healthiest Foods most likely to cause adverse reactions include:

Food sensitivities to food additives or preservatives have also been widely published; some of these potentially aggravating compounds include tartrazine (yellow dye #5), sulfites and the preservative BHT (butylated hydroxytoluene).

Any food has the potential of causing adverse reactions in specific individuals. The types of foods to which a person may have an adverse reaction can be as unique as each individual. Your unique biochemistry may be improved by eliminating some foods from your menu.

Clinical research is accumulating evidence that a food sensitivity can also increase the severity of the symptoms of several health conditions. These include rheumatoid arthritis, asthma and other diseases not normally considered food related.

One important tip: You need to avoid the food not only in its most obvious state (e.g., wheat in bread or pasta) but also when it is used as a component in prepared foods (e.g., wheat in soy sauce, soups, cereals and baked goods labeled as made from wheat). So, be sure to read labels and to order carefully when eating at restaurants.

One way to help determine the foods to which you may be sensitive to is to follow the Elimination Plan (page 821) with the guidance of a healthcare practitioner.

Food allergies can elicit symptoms that range from mild (sneezing) to life-threatening (anaphylactic reaction) depending upon the individual. Researchers have estimated that over 3% of adults worldwide experience food allergies, with the prevalence even higher in children. As food allergies have compromising effects on health, it is important for individuals with known or suspected allergies to avoid foods to which they are sensitive.

Food allergies are defined as toxic clinical reactions involving the immune system upon exposure to an “offending” substance found in a food. An allergic reaction to a food occurs when your body identifies molecules in that food as potentially harmful and toxic; these molecules are called antigens. Immune system cells bind to the antigens causing chemicals, such as histamine, to be released. These chemicals signal scavenger immune cells to come to the site of activity and destroy the antigens. An inflammatory process can result, which is the cause of many of the symptoms of food allergy reactions.

The most common symptoms for food allergies include eczema, hives, skin rash, headache, runny nose, itchy eyes, wheezing, diarrhea, vomiting and blood in stools. Symptoms can vary depending upon a number of variables including age, the type of allergen (antigen) and the amount of food consumed.

It may be difficult to associate the symptoms of an allergic reaction to a particular food because the response time can be highly variable. For example, an allergic response to eating seafood will usually occur within minutes after consumption in the form of a rash, hives or asthma, or a combination of these symptoms. However, the symptoms of an allergic reaction to cow’s milk may be delayed for 24 to 48 hours after consuming the milk or milk-containing food; these symptoms may also be low-grade (feeling tired or a slight headache) and last for several days.

If this does not make diagnosis difficult enough, reactions to foods made from cow’s milk may also vary depending on how it was produced and the portion of the milk to which you are allergic. (Casein is the protein portion of milk, which is responsible for most allergies to cow’s milk.) Delayed allergic reactions to foods are difficult to identify without eliminating the food from your diet for at least several weeks, then slowly reintroducing it while taking note of any physical, emotional or mental changes that may occur.

It’s also worth pointing out that some people have cravings for the foods to which they are most allergic. This also adds to the confusing aspect of identifying food allergies because the immune response to these foods produces histamines and cortisol, which may make you feel better while they are actually being detrimental to your health.

Although allergic reactions can occur to almost any food, research studies on food allergies have found that some foods are more closely associated with food allergies than others. The commonness of a food allergy appears to be country specific and is often related to foods most frequently eaten (for example, rice allergy in Japan).

Although allergic reactions can occur to virtually any food, research studies on food allergy consistently report more problems with some foods than with others.

Foods most commonly associated with allergic reactions:

Foods less commonly associated with allergic reactions:

If you suspect food allergy to be an underlying factor in your health problems, you may want to avoid commonly allergenic foods. To do so, you may want to consider consulting a nutritionist or other healthcare practitioner well versed in nutrition who can assist you both in identifying the foods to which you may be allergic and in designing nutritious meal plans that avoid these foods. The Elimination Plan, on page 821, a wonderful tool for identifying foods that trigger adverse reactions, may be recommended.

Certain grains, such as barley, oats, rye and wheat are often classified as members of a non-scientifically established grain group traditionally called the “gluten grains.” The idea of grouping certain grains together under the label “gluten grains” has come into question in recent years as technology has given food scientists a way to look more closely at the composition of grains. Some healthcare practitioners continue to group these grains together under the heading of “gluten grains” and to ask for elimination of the entire group on a wheat-free diet. Other practitioners now treat wheat separately from these other grains, based on recent research that does not support that these other grains elicit the same response as wheat, which is unquestionably a more common source of food allergies than any of the other “gluten grains.” Although you may initially want to eliminate the non-wheat “gluten grains” from your meal planning if you are implementing a wheat-free diet, you may want to experiment at some point with reintroduction of these foods. You may be able to take advantage of their diverse nutritional benefits without experiencing an adverse reaction. Individuals with wheat-related conditions like celiac sprue or gluten-sensitive enteropathies should consult with their healthcare practitioner before experimenting with any of the “gluten grains.”

Some foods contain goitrogens, naturally occurring substances that can interfere with the function of the thyroid gland. Goitrogens get their name from the term “goiter,” which means an enlargement of the thyroid gland. If the thyroid gland is having difficulty making thyroid hormones, it may enlarge as a way of trying to compensate for this inadequate hormone production. “Goitrogens” are compounds in foods that make it more difficult for the thyroid gland to create its hormones.

In the absence of thyroid problems, no research evidence suggests that goitrogenic foods will negatively impact your health. In fact, the opposite is true: soy foods and cruciferous vegetables, two groups of foods that are known to contain goitrogens, have unique nutritional value and eating these foods has been associated with decreased risk of disease in many research studies.

Because carefully controlled research studies have yet to be done on the relationship between goitrogenic foods and thyroid hormone deficiency, healthcare practitioners differ greatly on their perspectives as to whether people who have thyroid problems, and notably a thyroid hormone deficiency, should limit their intake of goitrogenic foods. Most practitioners use words like “overconsumption” or “excessive” to describe the kind of goitrogen intake that would be a problem for individuals with thyroid hormone deficiency. Here the goal is not to eliminate goitrogenic foods from the meal plan, but to limit intake so that it falls within a reasonable range. A standard one cup serving of cruciferous vegetables two to three times per week and a standard four-ounce serving of tofu twice a week is likely to be tolerated by many individuals with thyroid hormone deficiency (although please get your doctor’s perspective before undertaking this modification in an already suggested dietary plan).

Two general categories of foods have been associated with disrupted thyroid hormone production in humans: soybean-related foods and cruciferous vegetables. In addition, a few other foods not included in these categories—such as peaches, strawberries and millet—also contain goitrogens. The following are some of the most well-known goitrogen-containing foods.

Included in the category of soybean-related foods are soybeans themselves, soy extracts and foods made from soy, including tofu and tempeh. While soy foods share many common ingredients, it is the isoflavones in soy that have been associated with decreased thyroid hormone output. Isoflavones are naturally occurring substances that belong to the flavonoid family of nutrients. Flavonoids, found in virtually all plants, are pigments that give plants their amazing array of colors. Most research studies in the health sciences have focused on the beneficial properties of flavonoids, and these naturally occurring phytonutrients have repeatedly been shown to be highly health supportive.

The link between isoflavones and decreased thyroid function is, in fact, one of the few areas in which flavonoid intake has been called into question as being problematic. Isoflavones like genistein appear to reduce thyroid hormone output by blocking activity of an enzyme called thyroid peroxidase, which is responsible for adding iodine to the thyroid hormones. (Thyroid hormones must have three or four iodine atoms added on to their structure in order to function properly.)

For individuals who need to limit their intake of goitrogenic foods, limiting the intake from soy foods is often much more problematic than with other foods since soy appears in so many combinations, and it is often a hidden ingredient in packaged food products. Ingredients like textured vegetable protein (TVP) and isolated soy concentrate may appear in foods that would rarely be expected to contain soy.

A second category of foods associated with disrupted thyroid hormone production is the cruciferous family of foods. Foods belonging to this family are called “crucifers” or Brassica vegetables and include broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, mustard, rutabagas, kohlrabi and turnips. Isothiocyanates are the category of substances in crucifers that have been associated with decreased thyroid function. Like the isoflavones, isothiocyanates appear to reduce thyroid function by blocking thyroid peroxidase and also by disrupting messages that are sent across the membranes of thyroid cells.

Goitrogen-containing foods include:

Although research studies are limited in this area, cooking may help inactivate the goitrogenic compounds found in food. Both isoflavones (found in soy foods) and isothiocyanates (found in cruciferous vegetables) seem to be heat sensitive, and cooking appears to lower the availability of these substances. In the case of isothiocyanates in cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, as much as one-third of this goitrogenic substance may be deactivated when broccoli is boiled in water. Unfortunately, boiling also depletes broccoli of such a high percentage of its other health-promoting nutrients that I cannot recommend this cooking method. Those with thyroid problems who have been advised by their healthcare practitioner to limit excessive consumption of goitrogen-containing foods should simply take care to consume no more than a one cup serving of crucifers two to three times per week. (Please check that your healthcare practitioner does not want you to limit it any further.)

Lactose, or milk sugar, forms about 4.7% of the solids in cow’s milk and 4.1% in goat’s milk. Many individuals lack the enzyme, lactase, which is needed to digest lactose. For this reason, food intolerances to milk and dairy products are among the most common food intolerances seen by healthcare practitioners. Some individuals with lactose intolerance can better tolerate hard cheese and yogurt than other forms of dairy products.

The bacteria used to produce cheese and the time required for the cheese to ferment both work to lower lactose levels. Therefore, hard cheese may have much reduced lactose levels compared to milk (0–3 grams per ounce compared to 10–12 grams per cup of cow’s milk). Because time is a factor in the reduction of lactose, as a hard cheese is aged, the lactose content will decrease towards the zero end of its range. Therefore, many individuals with lactose intolerance may be able to eat moderate amounts of hard, aged cheese without a problem. This does not apply to soft cheese, which may be identical to cow’s milk in terms of lactose content, containing from 6–12 grams per ounce.

Some individuals with lactose intolerance may be able to also enjoy yogurt, as long as it is good quality yogurt made with active cultures. That is because these active cultures of beneficial bacteria predigest some of the lactose during the yogurt making process, and can also help digest it once inside your body. As noted above, this benefit only applies to yogurt with live active cultures as cultures that have been killed during the production process will not deliver the same benefit.

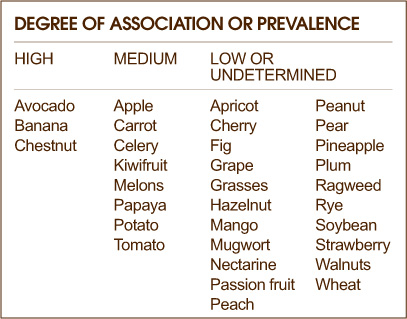

Between 30–50% of individuals who have allergies to latex may also have allergic reactions to certain plant foods. These allergic reactions may be either immediate or delayed hypersensitivity reactions, with symptoms ranging from hives to asthma to anaphylaxis.

Currently, the most conclusive evidence suggests that foods that cross-react with latex are those that contain enzymes called chitinases, which have similar protein structures to those found in latex. These include such foods as avocados, bananas and chestnuts. Researchers are also currently investigating other classes of compounds that may cross-react with latex, including patatin found in potatoes; however, this research is not yet as conclusive as that involving the chitinase-containing foods.

Latex food allergies have been found to be more prevalent in healthcare workers and those who have undergone medical procedures as these individuals have a greater exposure to medical supplies made of latex, including latex gloves.

Usually, it is best for individuals with latex allergy to avoid eating potentially problematic foods; however, some evidence suggests that cooked forms of the foods may be acceptable. Preliminary research has shown that cooking can deactivate the enzymes that may be responsible for the cross-reaction with latex. Consult your healthcare practitioner for more guidance on this topic.

According to the American Latex Allergy Association, the foods in the chart above have been found to have an association with latex food allergies.

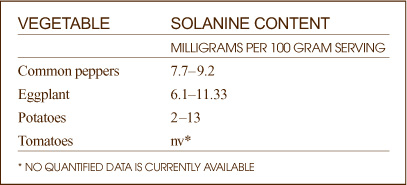

Nightshades are a diverse group of foods, herbs, shrubs and trees belonging to the scientific order called Polemoniales and to the scientific family called Solanaceae. While this botanical family is very diverse, containing such plants as tobacco, mandrake and belladonna, it also contains commonly consumed vegetables such as the potato, pepper, tomato and eggplant.

Most of the health research on nightshades has focused on a special group of substances found in all nightshades called alkaloids. There are four basic types of alkaloids found in nightshade plants, but steroid alkaloids are those most commonly found in the nightshade plants that are consumed as food.

While nightshades may be of more concern to individuals with nerve-related or inflammatory health conditions, some healthcare practitioners recommend that individuals who don’t have existing problems related to nightshade intake may want to still take precautions to avoid excessive intake of alkaloids from these foods.

The steroid alkaloids in nightshade foods—primarily solanine and chaonine—have been studied for their ability to block activity of an enzyme in nerve cells called cholinesterase. If the activity of cholinesterase is too strongly blocked, the nervous system control of muscle movement becomes disrupted, and muscle twitching, trembling, paralyzed breathing or convulsions can result. The steroid alkaloids found in potato have clearly been shown to block cholinesterase activity, but this block does not usually appear strong enough to produce nerve-muscle disruptions like twitching or trembling.

It has also been suggested that nightshade alkaloids may alter mineral status and cause inflammation that can damage joints, but whether alkaloids can contribute to joint damage of this kind is not clear from current levels of research. Some researchers have speculated that nightshade alkaloids can contribute to excessive loss of calcium from bone and excessive deposition of calcium in soft tissue. For this reason, these researchers have recommended elimination of nightshade foods from the meal plans of all individuals with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis or other joint problems like gout. Other practitioners recommend that individuals with these inflammatory conditions eliminate nightshade foods from their meal plan for two to three weeks to determine whether these foods are contributing to joint problems (the same applies to individuals with existing nerve-muscle related problems).

Nicotine is another alkaloid compound found in nightshade plants. Although they contain dramatically less nicotine than tobacco, nightshade plants that we consume as foods do contain some nicotine; however, the levels of nicotine in all nightshade foods are so low that most healthcare practitioners have simply ignored its presence in these foods as a potential compromising factor in our health. I both agree and disagree with this conclusion. While the amount of nicotine in nightshade foods is very small, it still seems possible that some individuals might be particularly sensitive to the nicotine found in nightshades, and that even very small amounts might compromise function in the bodies of these individuals.

The most famous food members of the nightshade family include potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), tomatoes (Lycopersicon lycopersicum), many species of sweet and hot peppers (all species of Capsicum, including Capsicum annum) and eggplant (Solanum melongena). Less well-known, but equally genuine nightshade foods include ground cherries (all species of Physalis), tomatillos (Physallis ixocapra), garden huckleberry (Solanum melanocerasum), tamarillos (Cyphomandra betacea), pepinos (Solanum muricatum) and naranjillas (Solanum quitoense). Pimentos (also called pimientos) belong to the nightshade family and usually come from the pepper plant, Capsicum annum. Pimento cheese and pimento-stuffed olives are therefore examples of foods that should be classified as containing nightshade components. Although the sweet potato, whose scientific name is Ipomoea batatas, belongs to the same plant order as the nightshades (Polemoniales), it does not belong to the Solanaceae family found in this order; it belongs to a different plant family called Convolvulaceae and thus does not carry the same concerns.

The seasoning paprika is also derived from Capsicum annum, the common red pepper, and the seasoning cayenne comes from another nightshade, Capsicum frutenscens. Tabasco sauce, which contains large amounts of Capsicum annum, should also be considered as a nightshade food. It may be helpful to note here that black pepper, which belongs to the Piperaceae family, is not a member of the nightshade foods.

The following chart reflects the solanine alkaloid content of three of the most commonly consumed nightshade foods: peppers, eggplants and potatoes.

Steaming, boiling and baking all help reduce the alkaloid content of nightshades. Alkaloids are only reduced, however, by about 40–50% from cooking. For non-sensitive individuals, the cooking of nightshade foods will often be sufficient to make the alkaloid risk from nightshade intake insignificant. However, for sensitive individuals, the remaining alkaloid concentration may still be enough to cause problems.

Green spots on potatoes or sprouting on potatoes usually corresponds to increased alkaloid content; this increased alkaloid content is one of the main reasons for avoiding consumption of green or sprouted potatoes. Thoroughly cut out all green areas, especially green areas on the peel, before cooking potatoes. If you know you are sensitive to nightshades, it’s best to discard the whole potato. A bitter taste in potatoes after they have been cooked is usually a good indication that excessive amounts of alkaloids are present.

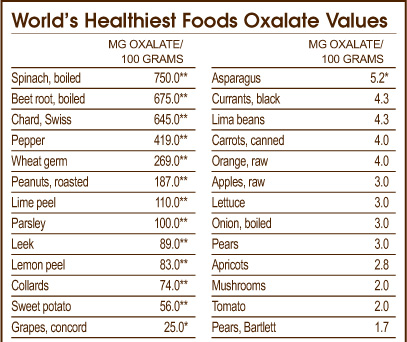

Oxalates (oxalic acid) are naturally occurring substances found in plants, animals and humans. In nutritional terms, oxalates belong to a group of molecules called organic acids and are routinely made by plants, animals and humans. Our bodies always contain oxalates, and our cells routinely convert other substances into oxalates. For example, vitamin C is one of the substances that our cells routinely convert into oxalates. In addition to the oxalates our bodies make, oxalates can come into the body from the outside, from certain foods that contain them.

A few, relatively rare health conditions require strict oxalate restriction. These conditions include absorptive hypercalciuria type II, enteric hyperoxaluria and primary hyperoxaluria. Dietary oxalates are usually restricted to 50 milligrams per day in individuals with these conditions. These relatively rare health conditions are different than a more common condition called nephrolithiasis in which susceptibility to kidney stone formation is increased.

The formation of kidney stones containing oxalate is an area of controversy in clinical nutrition with respect to dietary restriction of oxalate. About 80% of kidney stones formed by adults in the U.S. are calcium oxalate stones. It is not clear from the research, however, that restriction of dietary oxalate helps prevent formation of calcium oxalate stones in individuals who have previously formed such stones. Since intake of dietary oxalate accounts for only 10–15% of the oxalate found in the urine of individuals who form calcium oxalate stones, many researchers believe that dietary restriction cannot significantly reduce risk of stone formation.

In addition to the above observation, recent research studies have shown that intake of protein, calcium and water influence calcium oxalate stone formation as much as, or more than, intake of oxalate. Finally, some foods that have traditionally been assumed to increase stone formation because of their oxalate content (like black tea) actually appear in more recent research to have a preventive effect. For all of the above reasons, when healthcare providers recommend restriction of dietary oxalates to prevent calcium oxalate stone formation in individuals who have previously formed stones, they often suggest “limiting” or “reducing” oxalate intake rather than setting a specific milligram amount that should not be exceeded. “Reduce as much as can be tolerated” is another way that recommendations are often stated.

While the ability of oxalates to lower calcium absorption exists, it is actually relatively small and definitely does not outweigh the ability of oxalate-containing foods to contribute calcium to the meal plan. If your digestive tract is healthy, and you do a good job chewing and relaxing while you enjoy your meals, you will still get significant benefits—including absorption of calcium—from calcium-rich plant foods like soybeans and dark green leafy vegetables that also contain oxalic acid. Ordinarily, a healthcare practitioner would not discourage a person from eating these nutrient-rich foods because of their oxalate content.

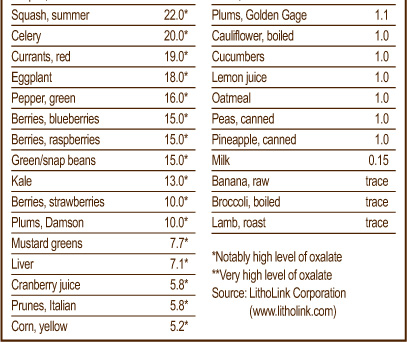

For a detailed list of foods that contain concentrated levels of oxalates, please see “Worlds Healthiest Foods Oxalate Values” chart on the previous page.

Cooking has a relatively small impact on the oxalate content of foods. Cooking has been shown to have negligible effects on oxalates when they are contained in the root or stalk of the plant. When oxalates are contained in the leaves, cooking has been shown to reduce their concentration, but not dramatically. A lowering of oxalate content by about 5–15% is the most you should expect when cooking a high-oxalate food. It does not make sense to me to overcook oxalate-containing foods in order to reduce their oxalate content. Because many vitamins and minerals are lost from overcooking more quickly than are oxalates, the overcooking of foods (particularly vegetables) will simply result in a far less nutritious diet that is minimally lower in oxalates.

For certain foods, it’s important to buy organic whenever possible. These foods are those fruits and vegetables whose conventionally grown “alternatives” have been found to contain high levels of pesticide residues.

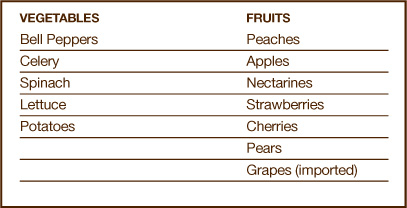

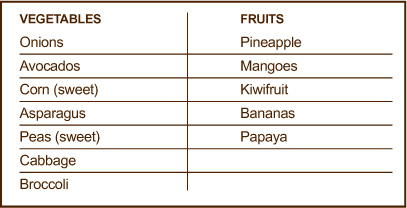

In the mid-1990s, the Environmental Working Group developed the “Dirty Dozen,” a list of high-risk, pesticide-containing foods. In 2006, they updated this list. I suggest that if you must prioritize your purchasing of organic produce, you focus on avoiding those that are included in the “Dirty Dozen.”

The reason we want to reduce our exposure to pesticides is because many of these agricultural chemicals are known toxins. In fact, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has classified 73 pesticides authorized for agricultural use as potential carcinogens (cancer-causing agents). And while other pesticides that have not received classification as “toxin” are deemed “safe,” the true nature of their impact may not really be known.

That is because many of the safety tests done focus on the effect of high doses of single pesticides rather than looking at more chronic low-dose impact, notably during times of development when an individual is more sensitive. Additionally, the effect of exposure to multiple chemical sources and the subsequent contamination that people experience (many of these chemicals are fat-soluble and therefore are stored in fatty deposits in the body) has not been studied as it is nearly impossible to assign specific health effects to one rather than another rather than the complex interplay of the chemicals.

Yet, independent research has been conducted focusing on exposure during fetal development and childhood, which has shown that pesticides can have life-long detrimental effects upon physical functioning. For more information about why organic foods, which are grown without pesticides and other agricultural chemicals, are better for health, please see page 171.

In their report (www.foodnews.org), the Environmental Working Group also identified the 12 fruits and vegetables least likely to have concentrated pesticide residues. If you are unable to purchase all organically grown produce, these are the conventionally grown varieties you can purchase with the least amount of concern.

Phytic acid, also referred to as phytate, is a naturally-occurring substance found in grains and beans. While this compound has been found to have some unique health-promoting properties, it has also garnered attention because of its ability to reduce absorption of certain minerals.

Concerns around phytic acid come from its ability to bind to minerals and lower their absorption. Researchers have suggested that in areas of the world where the diet is highly focused on grains to the exclusion of other foods, phytic acid may be responsible for the prevalence of mineral deficiencies. Therefore, there may be some concern as to the extent which ingesting phytic acid in whole grains and soybeans can impact the absorption of important dietary minerals, such as calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc and chromium.

While phytic acid may reduce mineral absorption, the amount to which it can really have a negative impact, given a well balanced diet that does not exclusively focus on grains and beans, is questionable. For most people, healthcare practitioners would not advise that individuals reduce their intake of whole grains or beans because of their phytic acid content. In addition, phytic acid has numerous health benefits.

Phytic acid has some very beneficial properties. It is a well-known antioxidant, able to scavenge free radicals that may cause oxidative damage to the body’s cells. Researchers are also investigating its ability to promote genetic health and enhance immunity, two other functions which, in addition to its antioxidant activity, may help to explain why laboratory studies have found phytic acid to inhibit the formation of tumors in the colon and other locations. Other proposed benefits for phytic acid include helping balance blood sugar levels, decreasing plasma cholesterol and triglycerides, and chelating heavy metals.

The processing and cooking of grains and soybeans lowers their phytic acid content, often by more than 50%. The sprouting of raw grains also lowers their phytic acid content.

Since acidic conditions can reduce the amount of phytate, sourdough whole grain breads have been found to have lower phytate content and less impact on mineral absorption than other types of bread.

Purines are natural substances found in all of the body’s cells and in virtually all foods. The reason for their widespread occurrence is simple: purines provide part of the structure of our genes and the genes of plants and other animals. A relatively small number of foods, however, contain concentrated amounts of purines. For the most part, these high-purine foods are also high-protein foods.

When purines get broken down completely, they form uric acid. In our blood, uric acid serves as an antioxidant and helps prevent damage to our blood vessel linings, so a continual supply of uric acid is important for protecting our blood vessels.

However, uric acid levels in the blood and other parts of the body can become too high under a variety of circumstances. Since our kidneys are responsible for helping keep blood levels of uric acid balanced, kidney problems can lead to excessive accumulation of uric acid in various parts of the body. Excessive breakdown of cells can also cause uric acid build-up. When uric acid accumulates, uric acid crystals can become deposited in our tendons, joints, kidneys and other organs. This accumulation of uric acid crystals is called gouty arthritis, or simply “gout.”

Low-purine diets are often used to help treat conditions like gout in which excessive uric acid is deposited in the tissues of the body. The average daily diet for an adult in the U.S. contains approximately 600–1,000 milligrams of purines. In a case of severe or advanced gout, dietitians will often ask individuals to decrease their total daily purine intake to 100–150 milligrams.

Although, for most individuals, purines in the diet are of little concern and may actually be beneficial because of the antioxidant activity of uric acid, in several other conditions, in addition to gout, purines may present a problem. These are rare conditions in which purine metabolism is disrupted, leading to problems such as anemia, failure to thrive, autism, cerebral palsy, deafness, epilepsy, susceptibility to recurrent infection and the inability to walk or talk.

A 3.5-ounce serving of some foods can contain up to 1,000 milligrams (mg) of purines. These foods include:

• Anchovies

• Herring

• Liver

• Mackerel

• Meat extracts

• Mussels

• Sardines

• Yeast

A 3.5-ounce serving of the following foods can contain 50–100 milligrams (mg) of purines:

• Beef

• Cod

• Lamb

• Lentils

• Scallops

• Bouillon (made from meat or poultry)

• Shrimp

• Turkey

• Venison

A 3.5-ounce serving of the following foods can contain 5–50 milligrams (mg) of purines:

• Asparagus

• Cauliflower

• Chicken

• Kidney beans

• Lima beans

• Mushrooms

• Navy beans

• Oatmeal

• Peas

• Salmon

• Spinach

• Tuna

Recent research has shown that the impact of plant purines on gout risk is very different from the impact of animal purines. This research has demonstrated that purines from meat and fish clearly increase our risk of gout, while purines from vegetables fail to change our risk. In summary, this epidemiological research (on tens of thousands of men and women) makes it clear that all purine-containing foods are not the same and that plant purines are far safer than meat and fish purines in terms of gout risk.

If you are not at risk for gout or other health problems related to purine metabolism, you would be unlikely to consume greater than the U.S. average for purine intake even if you ate more than ten servings of the foods in the last group. If you have been placed on a low purine diet that calls for no more than 150 milligrams of dietary purines, you may still be able to consume a 3.5 ounce serving of these foods per day without exceeding the 150 milligram limit for your overall diet.

Research on cooking and purine content is very limited. Animal studies in this area have shown definite changes in purine content following the boiling and broiling of purine-containing foods such as beef, beef liver, haddock and mushrooms. However, even though these cooking processes affect purine content, the nature of the changes is not clear.

On the one hand, boiling high-purine foods in water can cause breakdown of the purine-containing components (called nucleic acids) and eventual freeing up of the purines for absorption. For example, in some studies, when animals were fed cooked versus non-cooked foods, the animals eating the cooked version experienced greater absorption and excretion of purine-related compounds.

From this evidence, it might be tempting to conclude that cooking high-purine foods actually increases the amount of available purines. On the other hand, when foods were boiled, some of the purines were freed up into the cooking water and thus lost from the food (because the water in which the food was boiled was discarded after cooking). From this evidence, the exact opposite conclusion would make sense: cooking of high-purine-containing foods reduces the amount of purines they provide.

Conventionally raised cows may be treated with a compound called recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH). Canada has banned the use of this hormone in cows, based on research from Canadian scientists. Their report on rBGH noted that cows injected with the growth hormone reportedly have an 18% increase in the risk of infertility, a 50% increase in the risk of lameness and a 25% increase in the risk of mastitis (one concern is that cows with mastitis are treated with antibiotics). Another independent Canadian scientific committee found there was no direct risk to human health.

rBGH increases the content of insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) in cow’s milk. IGF-1 in cow’s milk is similar enough to the IGF-1 in humans to trigger biological activity. Our risk of breast and prostate cancer may be increased from routine consumption of cow’s milk partly in relationship to this IGF-1 mechanism. However, the same mechanism may also reduce our risk of colon and lung cancer. All of the risks described above are still a matter of debate, however, in the research literature.

Several U.S. groups have opposed the use of the hormone. The best way to ensure that you buy milk that has not been treated with rBGH is to buy organic dairy products.

Sulfur-containing compounds (sulfites) are among the most frequently used preservatives in the U.S. food supply. Sulfites are used to extend the shelf life of dried fruits, wines, shellfish and many processed foods by preventing oxidation, reducing discoloration and inhibiting bacterial growth.

Unfortunately, many people cannot “tolerate” sulfites. It has been estimated that one out of every 100 people may have adverse reactions to sulfites. These reactions can be particularly acute for those who suffer from asthma; the U.S. Food and Drug Administration estimates that 5% of asthmatics may experience a reaction when exposed to sulfites.

The following is a list of foods that may contain sulfites. Only specific forms of some foods (such as bottled lemon juice) contain sulfites.

• Dried apricots, dried apples and other dried versions of fruits

• Grapes—as well as wine made from grapes

• Lemons—bottled lemon juice

• Potatoes—dehydrated and peeled raw potatoes

• Shrimp

• Scallops

• Cod (dried)

• Wheat—processed baked goods (may be used in the dough conditioner)

Foods that are classified as “organic” do not contain sulfites since federal regulations prohibit the use of these preservatives in organically grown or originally produced foods. Therefore, concern about sulfite exposure is yet another reason to purchase organic foods.

As noted above, sulfites are not allowed to be used in organic foods. Therefore, if you want to avoid sulfites, it is best to purchase organic foods whenever possible, especially when it comes to foods listed above as well as processed foods.

There are some foods for which the sulfite-free version appears different than ones containing sulfites, For example, sulfite-free apricots are almost dark brown in color compared to the bright orange of apricots preserved with sulfites.

If you purchase foods that are not organically grown or organically produced, you will want to be diligent about reading packaged food labels to identify whether they contain sulfites. The following are the names of sulfite-containing preservatives as they may appear on the label:

• Sulfur dioxide

• Sodium sulfite

• Sodium bisulfute

• Potassium bisulfite

• Sodium metabisulfite

• Potassium metabisulfate

While preservatives need to be declared on the label, some foods are exempt from labeling laws. If you have questions about specific products, contact the manufacturer.

When eating in restaurants or purchasing foods from delis and other take-out locations, don’t hesitate to ask whether the foods you are considering eating contain sulfites.

Wines often contain sulfites. Migraine headaches and nasal and gastric discomfort are some of the symptoms associated with reactions to the sulfites contained in the wine. Conventional wines may also contain additional chemical additives to help protect against oxidation and bacterial spoilage to increase their shelf life. Selecting organic wines help some individuals avoid the headaches caused by conventionally produced wines.

Selecting organic red wines will help you avoid sulfites as well as help protect the environment because the grapes are grown without the use of chemical fertilizers, herbicides or insecticides. According to the USDA’s National Organic Program, “organic” or “100% organic” wines cannot contain any sulfites to display the USDA organic seal. However, be careful not to confuse “organic” wines with those that indicate they are made from organically grown grapes. Wines produced from organically grown grapes may not have met the USDA guidelines for “organic” and therefore may still contain sulfites.

Conventionally grown fruits and vegetables are often waxed to prevent moisture loss, protect them from bruising during shipping and increase their shelf life. Waxes are also said to help reduce greening in potatoes, but contrary to popular belief, waxes not only do not help reduce greening, but can actually increase potato decay by cutting down on gas exchange in and out of the potato.

When purchasing conventionally grown fruits and vegetables, you should ask your grocer about the kind of wax used even if you are going to peel the produce; carnauba wax (from carnauba palm tree), beeswax and shellac (from the lac beetle) are preferable to petroleum-based waxes, which contain solvent residues of wood rosins. Yet, it is not just the wax itself that may be of concern, but the other compounds often added to it: ethyl alcohol or ethanol for consistency, milk casein (a protein linked to milk allergy) as “film formers” and soaps as flowing agents.

Unfortunately, at this point in time, the only way I know of to remove the wax from conventionally grown produce is to remove the skin, as washing will not remove the wax or any bacteria trapped beneath it. If you choose to do this, use a peeler that takes off only a thin layer of skin, as many healthy vitamins and minerals lie below the skin.

Organically grown produce does not contain wax coatings, allowing you to enjoy all of the nutritional benefits offered by the skin.

Q Is it true that some waxes used on vegetables may contain casein (milk protein) to which many people are allergic?

A Many foods that have not been produced organically get subjected to treatments that make them easier to transport and have longer shelf lifes. In addition, conventionally grown foods can be packaged in materials that have been injected with additives designed to permeate the food. In many cases, coatings and packaging additives can be placed in a category of accidental additives that do not have to be disclosed. You’ll find some fascinating discussion of the wax-and-casein issues in the websites below. The third website will give you an actual example of a produce wax available in the marketplace that contains casein.

(1) http://www.star-k.org/kashrus/kk-vegetables-wax.htm

(2) http://www.foodproductdesign.com/archive/1997/0497CS.html