Fortunately, a Caribbean bar is not difficult to set up. Remember that in the islands, minimal is the word, so there is no real need for fancy equipment, but some basic essentials can help make your drinks as amazing as possible. You need a basic bartender’s set of tools and should consider a good blender with a strong motor. Fancy gadgets are far from necessary for a good Caribbean cocktail. Here are some of the necessities plus a few embellishments.

BAR TOWELS: They can be plain white tea towels or have all manner of sayings on them, but the fact remains that there will be spills to clean and glasses that need polishing.

CAN AND BOTTLE OPENERS: Be sure that you have an old-fashioned church key as well as the kind of wine-bottle opener that’s often called a waiter’s friend. It comes complete with a corkscrew, small knife, and bottle opener on one tool. Have good solid ones and make sure that they’re handy.

COCKTAIL SHAKER: An old-fashioned Boston shaker is made of two tumblers that fit tightly together. One tumbler is metal and the other is glass. Shaking the drink allows you to aerate it and create a bit of froth, but most important, it allows you to mix the ingredients thoroughly. Limit your displays of virtuosity to a few judicious maracas-like shakes in time to the music that’s playing.

ELECTRIC BLENDER: An electric blender with a strong motor is a must for a Caribbean bar if you’re a lover of frozen daiquiris and piña coladas.

JIGGER: This is the basic measure used for drinks. Usually a two-ended cup, the larger cone holds between 1½ and 2 ounces. The smaller cone is called a “pony” and holds either ¾ or 1 ounce. Whoops—no jigger? Remember that you probably have measuring spoons in your kitchen. Two tablespoons are equal to 1 ounce.

JUICER: You will be amazed at the flavor that real fruit can bring to a drink. You can use an old-fashioned carnival glass juicer like the one that your grandmother probably had. A wooden citrus reamer or the metal juicers that can be found in Latin American markets also work well. All drinks in this book call for fresh juice unless otherwise stated. With most of these you will need to strain the juice. Any small strainer will do for this task.

LONG-HANDLED BAR SPOON: Some drinks do not need shaking, as that will sometimes cloud the final cocktail. These should be stirred gently with a long spoon that is designed to incorporate all of the ingredients.

MUDDLER: Essentially a pestle without the mortar, a muddler allows the bartender to extract the oils from citrus pieces, or mash fruit like strawberries and passion fruit in a glass.

NUTMEG GRATER: Rum punches and other classic Caribbean cocktails need the final fillip of a dash of nutmeg. The stuff that comes out of the can or bottle will simply not do. Get yourself a modest nutmeg grater and top each drink off with a grinding of the real thing.

PARING KNIFE AND CUTTING BOARD: You’ll need these in order to cut ingredients down to size for muddling or as garnishes.

STRAINER: More accurately called a Hawthorne strainer, this is the familiar round strainer, with a springlike coil around the edge, through which a shaken drink is poured. It is designed to fit snugly over the mouth of the glass section of a cocktail shaker.

SWIZZLE STICK: If you’re traveling in the Caribbean, you may be able to find a traditional wooden swizzle stick, which has many spokes radiating from a central stem. If not, simply use a small bar whisk for the same results.

ZESTER: This is a small knife that allows you to separate the zest from the pith of citrus fruit. Some zesters make small zest, while others create larger twists.

Rum comes in many different styles and a well-stocked Caribbean bar will have varieties of each. There are basically two different types: Rum made from molasses and rum made from sugarcane juice.

Molasses-based rums are more common and come from Jamaica, Barbados, Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Bermuda, and most of the rest of the Caribbean. This is the style that we are most familiar with. Individual islands and even individual distillers have their own styles; indeed, most distilleries have two or three different types of rum in their repertoires. Increasingly, distillers are aging their rums for a final product that is more complex (and more expensive). Bacardi is known for its perfection as a mixer and many of the rums from the Spanish-speaking areas like Cuba and the Dominican Republic mirror its adaptability. Appleton and Myers’s from Jamaica are heartier and valued for their caramel undertones. Gosling’s from Bermuda seems dark in the glass, but is light to the taste. Barbados’ Mount Gay offers a range of rums from the light silver to the snifter-worthy sugarcane brandy.

Under the umbrella of molasses-based rums, the British style is hearty in Jamaica and smooth in Barbados. The Spanish style in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic is made for mixing—think Bacardi in all of its variations. Some of the rums of the Spanish Caribbean and Latin America are remarkably smooth, and there are some prize-winners there, so it’s hard to generalize.

The French style has an entirely different taste, as rum in the French-speaking islands is based on sugarcane juice rather than molasses. This gives the rum (they are actually called rhum, as I will refer to them in recipes) a winey nose. Many of these rhums are aged in oak for considerable time and take on the taste and depth of a fine old cognac. If you are lucky enough to taste one of these, don’t mix it with anything, simply pour it into a snifter and take your time.

Although they have precedent in history, today’s spiced rums are geared for a younger American market.

These can be used to create your own infused rums or simply as flavoring agents for your Caribbean cocktails.

ALLSPICE: This berry, the size of a large peppercorn, has the taste of nutmeg, cinnamon, black pepper, and cloves. The berries are also known as Jamaica pepper and, to the eternal confusion of many, as pimento. Infuse it in rum and you’ve got a variation of Pimento Dram (page 104), a classic Jamaican liqueur.

Allspice is readily available in supermarkets. Purchase whole berries, not the powdered form. Also note that the berries can vary widely in size so use your own judgment when a recipe calls for a certain number.

CANE SYRUP: This light-colored sugar syrup has a hint of the molasses taste of sugarcane. It’s used in preparing the ’ti punch and punch vieux that are the ubiquitous drinks of the French Antilles. A simple sugar syrup (page 39) is a good substitute.

Another version of cane syrup is that from Louisiana, which goes by the name of melao de cana in the Spanish-speaking world or sirop de batterie in the French one. This heavy, dark syrup is made from pressed sugarcane but is lighter in taste than molasses. Steen’s, the brand of choice in Louisiana, can be ordered via mail (see page 162). If you’re fortunate enough to make it to the farmers’ market in New Orleans, you may purchase cane syrup prepared from heirloom canes by local farmers.

CINNAMON: The rolled-up quill of the dried pale-brown inner bark of the cinnamon tree was one of the most precious spices of the ancient Romans. Known generically as “spice” to people in the English-speaking Caribbean, it grows in the Caribbean, where it is commonly used along with its coarser, close cousin, cassia. When purchasing it, look for the quills and not the ground spice. You can grind your own in a spice or coffee grinder that is kept for this purpose. You should look for quills that are highly aromatic and keep them in an airtight container so that they do not lose their potency. Long quills make an interesting garnish to some hot drinks that use the spice as an ingredient.

CURACAO: This is an orange-flavored liqueur named for one of the islands of the Netherlands Antilles on which it is produced. It is readily available in liquor stores. Blue curaçao often turns up in Caribbean cocktails, as its color allows the final mixed drink to have the blue of a tropical lagoon.

FALERNUM: This sugar syrup takes its name from a Roman wine. It is flavored with almond, ginger, cloves, and lime, and may contain hints of vanilla, allspice, or other ingredients. It’s used in many tropical beverages in place of simple syrup and may or may not be alcoholic. It’s mainly used in the southern Caribbean and most commonly in Barbados, where it is one of the ingredients in Corn and Oil (the other is rum!). You can purchase falernum online (see page 162) or make your own (page 41).

GINGER: This rhizome of a tropical plant is probably a native of Asia. It has done so well in the New World, though, that Jamaican ginger has become well known. Ginger is used fresh, dried, or powdered in many of the region’s recipes and it turns up in ginger beers.

If purchasing powdered ginger, look for Jamaican, which is more delicate in flavor. Purchase rhizome ginger when it is firm. It can be refrigerated wrapped in paper towels or plastic bags. Don’t forget that ginger ale and the less common ginger beer can add a gingery zing to drinks along with a bit of fizz. A simple syrup prepared from ginger juice (page 39) is another lovely addition to a drink.

GRENADINE: If it’s pink and a drink, it’s probably got grenadine in it somewhere. This syrup was originally made from pomegranate juice and its name comes from grenade, the French word for pomegranate, which also gives its name to the island of Grenada. Today’s grenadines are more often than not prepared from artificial ingredients, but now that pomegranate juice has become quite readily available, it’s time to attempt to make your own grenadine (page 40).

GUAVABERRY LIQUEUR: Although I had my first taste of guavaberry liqueur in St. Croix, the beverage is the national drink of St. Maarten. Prepared from the fruit of the guavaberry bush—no relation to the guava—the liqueur is a holiday tradition on the Dutch side of the island, where carolers used to go from house to house singing, “Good morning, good morning; I come for me guavaberry” before being treated to a taste of the host’s homemade potion. Today, you can purchase guavaberry liqueur when traveling to St. Maarten, online, or occasionally in U.S. liquor stores.

MALIBU: This is a favorite brand of sweet coconut-flavored rum from Barbados. It’s a popular mixer and sold in more than eighty countries. It’s readily available and good straight or as a mixer. Try some in a piña colada.

MAUBY: I have a postcard from the early 1900s that shows a Caribbean mauby seller from Guadeloupe (facing page, top left). She’s seated next to a tray full of bottles, looking at the camera with a bottle in her hand, and dressed in traditional grande robe with a headtie around her carefully coiffed hair. Standing over her is a bare-chested workman in torn pants who is drinking thirstily from a bottle of mauby.

Mauby, called mabi in French, is a local beverage in much of the Caribbean. Until fairly recently, it was common to see vendors in the main streets of Caribbean towns with containers of mauby balanced on their heads, and virtually every housewife had her own purveyor.

The traditional beverage is prepared from the fruit and bark of several small fragrant Caribbean trees: Columbrina elliptica or Columbrina aborescens. The liquid is then diluted with water, flavored with vanilla, and sweetened with sugar. There are many different recipes for preparation, but several include aniseed. The drink can be fermented as a sort of root beer with a kick or consumed unfermented. Mauby is reputed to have a variety of medicinal uses, ranging from curing children’s ailments to calming stomachaches. It’s a sort of root beer panacea. Today, things have changed; mauby is not simply sold in markets as bits of bark and twigs, but it is packaged in cellophane and even sold in bottled form to be diluted to taste. Since the method of preparation will depend on the type of mauby you find, I will leave this one up to you. Simply follow the package directions. Then add ice and savor.

MOLASSES: Called melasse in French and melao de cana in Spanish, this by-product of sugarcane refining is a spicy thread that runs through the history of blacks in the New World. Molasses was one of the Americas’ principal sweeteners until the middle of the nineteenth century. It is easily available at the supermarket near the sugar products. Try using a spoonful instead of sugar in lemonade or limeade.

NUTMEG AND MACE: Two of the spices that Columbus was looking for when he stumbled upon the Caribbean—nutmeg and mace—are from the same tree. The nutmeg is the seed and the mace is the lacy aril that covers it. Grenada, the Caribbean’s Spice Island, is one of the world’s largest producers of nutmeg today. Nutmeg has been a popular spice in Caribbean cocktails for centuries and a grating is indispensable to a true rum punch.

Get a nutmeg grater and whole nuts, which will release a small bit of oil when pressed if they are good quality. Buy in small quantities and store in an airtight container, as nutmeg rapidly loses its aroma. (Nutmeg novices should know that the nutmeg may come within its shell. The red casing on the outside is mace; remove it, then crack the shell to get at the nutmeg.)

ORGEAT: This almond-flavored syrup is a mix of almonds and orange flower water and may contain barley water. It can be used solo or mixed with water. In the Spanish-speaking world, it is the basis of the summer drink horchata, but it is also used as an ingredient in several mixed drinks, such as mai tais. Orgeat can be found in specialty stores and Spanish markets or ordered online (see page 162).

SORREL: The deep red flower of the hibiscus family is sometimes known as roselle (rosella) and in Spanish as flor de Jamaica. It is African in origin and is consumed in Egypt under the name of carcade or karkade. The podlike flowers of the plant are dried and steeped in water to make a brilliant red drink that has a slightly tart taste. It is a traditional Christmas drink with or without rum. Formerly found in Caribbean markets at Christmastime, sorrel is now available in them almost year-round. Fresh sorrel is available at Christmastime.

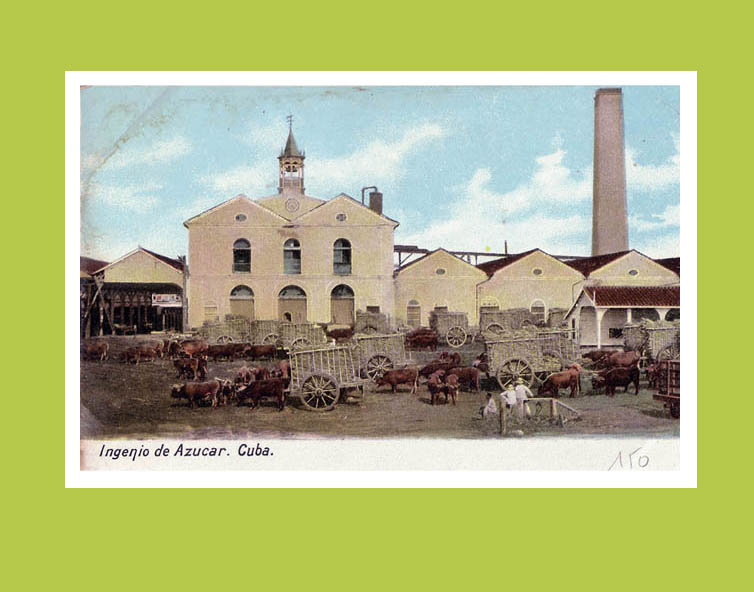

SUGARCANE: This “honey-bearing reed” was brought to the Caribbean from the Canary Islands by Columbus on his second voyage in 1493. Until recently, the refined superfine white sugar crystals have been most popular. Many people now prefer the pure cane taste of Muscovado (a.k.a. Barbados) or Demerara sugar, which is the last sugar in the barrel after the molasses has been drained off. Sugarcane can be mail-ordered or occasionally found in Caribbean and Asian neighborhoods. The sweet juice known as gurapo in Cuba is an interesting base on which to build a cocktail. Long, thin sticks cut from sugarcane stalks can be used as garnishes in drinks or as skewers for cocktail nibbles.

TIA MARIA: A Jamaican coffee liqueur, Tia Maria was invented in Jamaica around World War I. It is a mix of Jamaican Blue Mountain coffee and other ingredients. It’s a prime mixer for making a Jamaican coffee with good Jamaican rum.

VANILLA: The pods of this relative of an orchid develop their deep coloring and taste after a lengthy period of processing. First used by the Aztecs, vanilla is one of the world’s master spices and is used in much of the baking of the Creole world. Anyone who has seen the fat, oily beans in the market in Guadeloupe will opt to prepare their own extract by adding a vanilla bean to a small vial of dark rum for a particularly Caribbean addition. Make your own vanilla rum by infusing a few vanilla beans in the alcohol. Just pop them in, replace the top, and let the bottle sit in a cool place for a week or so. Voila!

Drinks are often enhanced by a dash or two of something other than the alcohols that go into their mixing. Often these add a subtle bitterness or give the drink the hint of sweetness that makes it sing. The complexity that is given by these additions is one of the things that distinguishes a professionally made potion from that of a mere amateur.

BITTERS: Bitters are alcohols that have been infused with the essence of herbs and roots. Essentially they’re tinctures and they are often as strong as 80 or 90 proof. They were originally marketed in Europe as digestive aids. Bitters certainly are known for settling upset stomachs and a dash or two in a glass of club soda or ginger ale can work wonders for the queasy. Even though they’re used in small quantities, bitters should not be used in nonalcoholic beverages because they contain alcohol and could be harmful to those who are allergic to it. For those without such allergies, a dash of bitters in a French lemonade gives the fizz complexity and makes it seem more adult. Popular bitters include such brands as Angostura, which are the classic Caribbean brand, and Peychaud’s, which are from New Orleans.

There is a second category of bitters that includes beverages such as Campari or Fernet Branca or Cynar. They, too, have their digestive claims, and a small glass of Fernet Branca or a dash or two in a glass of water or soda is considered a hangover cure by some hard-drinking folks I know. These bitters can be consumed as aperitifs, but a dash or two can also be used to add complexity to cocktails.

Some folks are making their own bitters today and myriad recipes can be found on the Web. Jamie Boudreau has an interesting post including a do-it-yourself recipe for cherry bitters on SpiritsandCocktails.com. Those with less initiative may want to just go to the Fee Brothers Web site (see page 162). It’s a bartender’s secret source and offers six types of bitters including orange bitters, mint bitters, peach bitters, and grapefruit bitters. You can order Peychaud’s through the Sazerac company Web site (see page 162).

SWEETS: Simple syrup is just what it claims to be: a syrup that is simple to prepare. It is a sweetening agent and is used in most drinks to counterpoint the acidity of lemon or lime. It can also be used to sweeten everything from iced tea to mixed drinks. There are numerous ways to prepare simple syrup; the easiest and most common is to use one part water to one part sugar. Others prefer a heavier syrup and use two parts sugar to one water.

I’m a two-to-one person. You can just use one cup of sugar if you prefer.

makes about 1 cup

2 cups sugar

1 cup water

Combine the sugar and water in a small saucepan and bring to a simmer over medium heat, stirring occasionally. Continue to simmer and stir until all of the sugar has dissolved, about 3 minutes. Allow the syrup to cool to room temperature and then pour it into a sterilized decorative bottle that can be fitted with a speed pourer. The syrup will keep in the refrigerator for 1 month.

You can prepare a ginger syrup by substituting ginger juice for half of the liquid in the simple syrup recipe. Make ginger juice by grating ginger into cheesecloth and squeezing it, or purchase it from www.gingerpeople.com.

You can prepare grenadine by replacing the water in the simple syrup recipe with pomegranate juice, which is readily available.

Once you’ve mastered the simple syrup, then it’s a short step to making your own flavor-infused syrups. Try a simple lavender syrup. It can be used to sweeten lemonade and as a cooling drink with the addition of club soda or plain tap water.

makes about 2½ cups

3 cups water

½ cup lavender flowers

3 cups sugar

Put the water and lavender flowers in a 3-quart saucepan and bring to a boil over medium heat. Lower the heat and allow it to simmer for 3 to 5 minutes. Remove from the heat and allow it to infuse for 5 minutes.

Strain the liquid into a bowl, pressing down on the lavender flowers to make sure that all of the liquid is released. Return the liquid to the saucepan and add the sugar. Stir until all of the sugar is dissolved and then bring to a simmer over medium heat. Remove the syrup from the heat and allow it to cool. Decant it into a sterilized bottle. (I use the stoppered bottles that French lemonade comes in and boil them and remove the labels before use.)

The syrup will keep in the refrigerator for several weeks.

Prepare as for lavender syrup, substituting 3 tablespoons minced fresh peppermint leaves and 2 tablespoons minced fresh spearmint leaves for the lavender. This liquid is a perfect way to keep the minty flavor at its peak in a mojito.

makes about ¾ cup

1 cup water

3 ounces fresh ginger, smashed

½ teaspoon black peppercorns, crushed

¼ teaspoon minced jalapeño chile

1 cup sugar

Put the water, ginger, peppercorns, and chile in a small nonreactive saucepan and bring to a boil over medium heat. Lower the heat and allow it to simmer for 3 to 5 minutes. Remove from the heat and allow it to infuse for 5 minutes.

Strain the liquid into a bowl, pressing down on the solids to make sure that all of the liquid is released. Return the liquid to the saucepan and add the sugar. Stir until all of the sugar is dissolved and then bring to a simmer over medium heat. Remove the syrup from the heat and allow it to cool. It will keep in the refridgerator for several weeks.

Falernum is a sweetening agent that is used in Barbados and that is difficult to find Stateside. Adjust the flavorings to suit your taste. I like mine a little sweet.

makes 1 liter

12 limes, zested

2 tablespoons sugar

8 whole cloves

Dash of almond extract

1 liter Barbadian-style white rum, such as Mount Gay or Cockspur

Put the zest, sugar, cloves, and almond extract in a large glass container or jar, add the rum, and loosely cover. Keep in a sunny place for 4 days. Strain it to remove the solids and pour the liquid into a bottle that can be fitted with a speed pourer. The falernum will keep for several months at room temperature.

Some cocktails look especially pretty when presented in a sugar-rimmed glass. Prepare your own mixture of sugar that combines all of the flavors of the island of Grenada, the region’s very own spice island.

makes 1½ cups

½ cup dark brown Muscovado sugar

1 cup superfine sugar

2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1 teaspoon ground nutmeg

½ teaspoon ground mace

¼ teaspoon ground allspice

Put the sugar in the bowl of a heavy mortar or a food processor and pound or grind it until it is reduced to fine crystals. Then add the remaining ingredients to the bowl and stir to mix until well combined. This will keep for several weeks in a glass jar. When ready to use, pour it into a saucer and lightly wet the rim of the glass. Dip it in the sugar and you’re ready to go.

GLASSES: The French have a saying: “The eyes eat first.” I could adapt it to Caribbean cocktails and say, “The eyes drink first.” An attractive, appetizing cocktail is what you want, so glasses are important. Before you’ve made a drink, ask yourself what kind of glass will best show this off? Or, what type of glass will give your drink a bit of extra flair? There is such an abundance of choice today that the mind boggles.

Glass types that are given with the recipes are only suggestions, not hard and fast rules. If you prefer a stemmed glass as I do, use it even if you’re drinking a tall colada. Your glasses are an extension of your own taste and, just as you would personalize the drink they contain, you should personalize the glasses. A final note: remember, glasses do not have to be purchased in sets. What better way to distinguish an individual’s drink than by having each drink in a different glass? Think of all of those different heirloom glasses and those unmatched ones that lurk at the back of the closet. Now’s the time to get them out, wash them to a bright sparkle, and use them. That’s one way not to lose your drink at a cocktail party.

The basic glass types follow, but don’t be afraid to be adventurous. If you like a stemmed glass—use it. Love that jelly jar with the decorations of red flowers that you remember from childhood? Use it! This is the time to have fun.

Bucket Glass (Old Fashioned): Short and squat with a thick base, this type of glass will come in handy when you make a caipirinha or any drink that requires a muddler. Sizes range from 6 to 8 ounces and it’s usually used for simple drinks like rum and soda.

Champagne Flute: Years ago Champagne was served in saucers allegedly shaped like Marie Antoinette’s breast. The long, thin flutes came into favor around the 1980s and are great because the bubbles keep longer. The smaller 6-ounce flutes are good for sours and the larger 10-ounce flutes can serve for other light cocktails that require a bit of flair.

Collins (Highball): This tall, thin, 8- to 10-ounce glass can be used for any drink that needs a bit of ice or that needs soda to top it off. It can be perfect for a dark and stormy or a rum punch.

Fruit Containers: Don’t forget that pineapples can be hollowed out and make perfect drink containers, as do brown coconuts. I’ve even seen small melons used.

Hurricane (Poco Grande): This curvaceous glass is named for the rum drink that is the hallmark of Pat O’Brien’s in New Orleans. It’s a classic Caribbean bar glass used for everything from piña coladas to shandys.

Irish Coffee Glass: This heat-resistant glass usually resembles a footed mug and is used for hot beverages like grogs.

Julep Cup: This classic silver cup conjures up images of the Kentucky Derby and drinks sipped on white columned verandas. In the Caribbean, though, the silver mug is put to good use serving rum juleps.

Martini: The triangular shape of a martini glass evokes thoughts of cool frosty gin with a whiff of vermouth. Think of it, though, when you need a glass that can be quickly chilled and will keep a drink cool since the fingers never touch the bowl. This makes it perfect for a classic daiquiri.

Pilsner: This is the typical 10- to 14-ounce tapered, footed beer glass that can work as an all-purpose glass when serving a tall drink that requires ice.

Snifter: This glass has a low foot, wide bowl, and a tapered mouth, and was created for savoring the finest brandies and cognacs. It’s designed to warm the liquid in the hands and concentrate its aroma. Some aged rums from the French Caribbean and some top-label brands from the rest of the region demand the respect of a snifter.

GARNISHES: Now that you have the perfect glass, it’s time to consider the small elements that will make the finished drink look professional. Sure, there are swizzle sticks and flexible straws and plastic floating mermaids that can hook over the edge of the glass. The following garnishes, though, are natural and will add a bit of Caribbean flair and flavor to your concoctions and make you look like a major mixologist.

Sugarcane: This is the raw material for the beverages in this book, but if you can obtain a stalk of it, cut it down into stirring spears with a very sharp knife. (Be extremely careful with cutting it, as it is hard to do! See page 138 for directions.)

Citrus Fruit: Certainly limes can be sliced and placed on the edge of a glass, but how boring. Think instead of curls of zest cascading from the side of a glass or a pinwheel of mixed citrus fruit skewered with a long toothpick or a banderilla of wedges of blood orange, lime, and grapefruit (you can add lemon, too). Use the color of the fruit and the flexibility of the peel (remember to remove as much of the white pith as possible), and your only limit is your imagination.

Coconut: Toast curls of fresh coconut meat that has been shaved with a vegetable peeler for great cocktail nibbles (page 130). They’re also perfect when crumbled on top of piña coladas and other coconut-flavored drinks.

Cucumber: Spears of cucumber are not just for Pimm’s cups. They are also good in savory drinks like Bloody Marys or in cooling drinks like an Isle of Pines.

Flowers: Mother Nature’s own decorations can be used to enhance any Caribbean cocktail; just be sure to consult a botanist or the local botanical garden or check online to make sure they’re edible before you end up with a party disaster. Look for edible flowers in the produce section of your grocery.

Herbs: No one would attempt a mojito without spearmint, so think of adding herbs as garnish. Why not garnish a high-octane limeade with a sprig of peppermint or add a little je ne sais quoi to a Bloody Mary with a bit of cilantro? Decide which fresh herb will set off the flavors of your drink to your liking, then proceed judiciously.

Husk Tomatoes: Also called tomatillos, these small sweet tomatoes have a papery outer skin that can be pulled back to display them. Add a tall wooden skewer and voilà—a beautiful drink! Small cherry tomatoes can do the same job, but they’re not nearly as exotic or exciting.

Kiwi: When slightly underripe, kiwis can be peeled and cut into circles that can be slit on one side to fit over any glass. They give a welcome change from the citrus that usually is presented there.

Melon: Getting serious about garnishing? Then, it’s time to invest in a melon baller. Try a skewer of watermelon, cantaloupe, and honey-dew balls or a single melon ball instead of a maraschino cherry. They add color and flavor to any tall drink.

Okra: I’ve never let an opportunity go by to use okra in some form. A pod of pickled okra is a perfect way to finish off a rum Bloody Mary. Use hot okra for additional zing to the drink.

Olives: These are a no-brainer and perfect in any savory drink. Don’t forget the wide array of olives currently available. I’m a sucker for the ones that are stuffed with anchovies, but you may prefer the almond- or blue cheese–stuffed olives.

Pineapple: There’s nothing that quite does the job as well as a spear of sweet, slightly acidic pineapple. Try the sweetest one you can find in your next piña colada and you’ll understand why it’s such a classic.

Spices: Two spices are traditionally used as garnishes in the region. Cinnamon sticks are used in drinks both cold and hot. Look for extra-long quills (some of the longest I’ve ever seen I purchased in the Plaza del Mercado in San Juan, Puerto Rico). And as for nutmeg, it simply wouldn’t be a rum punch without a grinding of fresh nutmeg on the top. Get yourself a nutmeg grater and use it fresh each and every time.

Strawberries: They do grow in the Caribbean region. I remember decades ago watching in amazement as women brought them down from the hills above Port au Prince, Haiti. Use them sparingly; one or two should do the trick as a garnish for strawberry daiquiris.

Umbrellas: It wouldn’t be a Caribbean cocktail without a fancy Japanese umbrella somewhere. Check the Internet sources (see page 162) and you can get some of your very own to play with.

Caribbean drinks gain their brilliant color and fantastic taste from the use of the region’s bounty of tropical fruit. Here are some that might turn up in your glass.

BANANAS: Any northerner who journeys to the Caribbean is astonished at the number of varieties of bananas. They range in size from the tiny, delicate ones with slightly sharp taste known as bananes-figues in the French-speaking Caribbean to large black-skinned ripe ones. Because of their form, they have always been identified with sexuality. In French Creole the small ones are called “go get dressed little boy” and the large ones, “Oh, Mama. God help me!”

Bananas are major players in several Caribbean cocktails for their creaminess and taste. Bananas should be purchased when their skins are unblemished and they are firm to the touch. They should never be refrigerated or they’ll begin to turn black.

CARAMBOLA: Called star fruit or five-fingered fruit, this multisided fruit becomes a translucent yellow when ripe. Its juice is consumed in the Caribbean and it is frequently used as a garnish in drinks. If you wish to juice them, the pale, slightly acidic juice adds a wonderful fillip to fruit punches and is great on its own with rum. Carambola is readily available at specialty greengrocers.

CHERIMOYA: Sometimes called the custard apple, this fist-sized fruit has a custard-like flesh that tastes like a mixture of vanilla ice cream and banana. Cherimoyas range in color from green to grayish brown to black. They are frequently used as the basis for fabulous beverages. A cherimoya should be eaten when it gives slightly when pressed with a finger and has a characteristically sweetish smell. They are found fresh only in specialty shops and in the subtropical areas of the United States. The rest of us have to content ourselves with canned or frozen pulp and juice.

CHILES: These fruits cross-pollinate with the alacrity of rabbits and have different names wherever you find them. There are Scotch Bonnet, wiri wiri, bird peppers, and more in the Caribbean, where the milder ones turn up occasionally as garnishes in drinks.

COCONUT: No one is exactly sure how the coconut arrived in the New World. They are thought to have originated in Southeast Asia, but the nut floats and it seems to have arrived in this hemisphere before the Europeans. For centuries, the coconut palm was virtually the staff of life for the peoples of the Caribbean.

In the summer in many Caribbean neighborhoods, jelly coconuts (the green fruit whose meat is still a jellylike mass) are hawked on the streets by vendors who open them and then pour the coconut water into plastic containers. And of course there are always the hairy brown coconuts that peer out at us from greengrocers’ bins with whimsical faces made from their “eyes.” They can be transformed into coconut milk, grated coconut, and just about any other coconut product you may need; they also make great serving vessels for many drinks.

Note that the liquid in a coconut is coconut water. Coconut milk is what results when grated coconut meat is infused in coconut water. Alternatively, if you’re in a real pinch, unsweetened canned coconut milk can be used. Some piña colada recipes call for cream of coconut, a canned thicker liquid. Coco Lopez is the brand to get.

To prepare coconut milk, open a brown or dry coconut by heating it in a medium oven for 10 minutes. (The coconut will develop “fault” lines.) Remove from the oven and use a hammer to break open the coconut along the “fault” lines. Remove the shell, scrape off the brown peel, and grate the white coconut meat. (You should get 1½ to 2 cups of tightly packed grated coconut. Using a food processor prevents skinned fingers.) Add 1 cup of heated coconut water or 1 cup boiling water to the grated coconut meat and allow the mixture to stand for half an hour. Strain the mixture though cheesecloth, squeezing the pulp to get all of the coconut milk.

GUAVA: This fruit is native to the Americas; there are over 100 edible varieties. A rich source of minerals and vitamins A and C, guavas are eaten at various stages of their development. When green, they are slightly tart; when ripe, they are sweeter. In the Caribbean, guava juice is popular and often found prepackaged in supermarkets. Try Loosa or Ceres brands or one of the Israeli varieties that will give your drinks the true flavor of this tropical fruit.

KIWI: Originally from China, this green fruit used to be known as the Chinese gooseberry until the 1950s. Its name change and marketing history are the stuff of business school textbooks and now the fuzzy-skinned green fruit that tastes of bananas and strawberries is virtually ubiquitous. Kiwis turn up as garnishes in the Caribbean and they can also be juiced, but strain out the seeds if juicing, as they will make the liquid bitter.

LIMES: Caribbean limes are similar to Key limes with thin greenish-yellow skins that turn yellow when overripe. Limes are the prime ingredient in most of the region’s drinks. In the French-speaking islands of the region, they are cut en palettes: sliced around the outside of the fruit’s center core so that each wedge is seedless. They are served at the side of the plate as condiments along with rum and sugar for the preparation of the French Caribbean’s ubiquitous ’ti punch. Caribbean limes rarely make their way to northern markets. Instead, select the juiciest regular (Persian) limes that you can find with no blemishes or soft spots, or purchase Key limes.

MANGO: This tropical fruit par excellence is known by some as “the king of the fruits.” More than 326 varieties have been recorded in India, although the fruit is thought to have originated in the Malaysian archipelago. Mangoes arrived in the New World (Brazil) in the fifteenth century and in the Caribbean after 1872. The most common mangoes in the Caribbean are Julie mangoes, which are flattened, light green ovals.

Mangoes are often pureed in drinks. Sucking the juice out of a ripe mango is one of the messier liquid delights of the region. Once a hard-to-find specialty fruit, mangoes are becoming more readily available in the States and Europe. If you cannot find them at regular greengrocers, look in shops selling Caribbean and tropical produce. Mangoes should be purchased when they are firm but yield slightly to the touch. A sniff will tell you if they are aromatic and ripe.

ORANGE: Oranges are so common that we give them culinary short shrift, but a fresh squirt of orange juice can brighten up any cocktail. Bitter oranges are the basis of the Caribbean liqueur known as curaçao and blood oranges are making their way into the drinks lexicon of the region. Oranges, like all citrus, should be selected when they are heavy for their size, as this indicates that they are juicy. As with all citrus, bottled juice is no substitute and canned is unthinkable!

PASSION FRUIT: The fruit from the passionflower can resemble a thick-skinned yellow or purple plum. Inside, numerous small black seeds are encased in a yellow- or orange-colored translucent flesh, which is wonderfully tart and almost citrusy. Called maracudja in some parts of the French-speaking Caribbean and granadille in others, it’s called granadilla in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean (where the juice is known as parcha).

Better known for its juice, passion fruit’s tart taste can be found in drinks throughout the region. The juice’s distinctive flavor can be found in numerous liqueurs mixed with everything from rum to cognac, and many commercial fruit juice mixes. Fresh passion fruit is increasingly available in the northern United States and the juice and passion fruit–flavored liqueurs (such as Alizé) are readily available.

PINEAPPLE: While many of us connect pineapples with Hawaii, they were first seen by Europeans in the Caribbean. Columbus noted them on his journey to Guadeloupe in 1493. Although they’re familiar to Americans, most of us have not savored the rich sweet taste of a pineapple that has ripened to maturity in the sun. The flavor when combined with that of fresh coconut is the hallmark of a perfect Caribbean piña colada (page 82). You can tell a ripe pineapple by its heft (it should feel heavy for its size) and by its aromatic smell. Canned pineapple or canned pineapple juice is no substitute for the juice of the ripe fruit unless you’re stranded on an iceberg!

POMELO: Chadec is the French name for this thick-skinned fruit, also called a shaddock. Thought to be the ancestor of the grapefruit, the fruit is used for juice; grapefruit can be substituted.

SOURSOP: The shape of this tropical fruit has earned it the nickname of bullock’s heart in some countries. Inside the spiny, leathery, dark-green skin, the pulp is white and creamy and slightly granular. Called corossol in the French-speaking Caribbean and guanabana in the Spanish-speaking countries, the soursop is native to the Caribbean and northern South America. It can also have a smooth green or greenish brown skin. Outside of the region, the fruit is usually consumed raw or in juices like Cuba’s Champola or Puerto Rico’s Carato.

The soursop rarely appears in northern markets, as they don’t travel well. However, if you’re lucky, select one that is slightly soft to the touch without too many blemishes. The pulp is also available frozen.

TAMARIND: This tropical tree produces a brown pod that is processed into an acidulated pulp used for flavoring. Tamarind can be purchased in shops selling Indian products as well as those selling Caribbean products. It usually comes in the form of a prepared pulp, which can be kept for a week or longer in the refrigerator. Prepared tamarind can also be frozen. Tamarind juice is also available, but use with caution as it can have prodigious laxative qualities.

UGLI: This grapefruit-sized fruit isn’t ugly at all. It is a cross between a grapefruit, an orange, and a tangerine—often called tangelo. It is a fruit of Jamaican origin and has a sweet citrus taste. It appears on Caribbean tables as juice and marmalade, and glazed and dipped in chocolate in candies. Ugli fruit can occasionally be found in supermarkets or at the greengrocers.

WATERMELON: An immigrant to the Caribbean, the watermelon is believed to have originated in southern Africa. Its high water content makes it perfect for quenching summer thirsts. The flesh can range in hue from pale orange to bright red. Seeded or seedless, thin skinned or thick, the watermelon means summer to many and is perfect for juicing. On the Caribbean’s Mexican coast, watermelon agua frescas are refreshers that are sold streetside, while other parts of the region simply use the fruit wedges as garnishes for drinks.

Folks thump and shake and sniff, but there are really few sure ways of picking a sweet watermelon other than tasting it. The juice is a great and unexpected addition to fruit punches and goes surprisingly well with white rum.

Bar spoon = ½ ounce

1 teaspoon = ½ ounce

1 tablespoon = ½ ounce

2 tablespoons (pony) = 1 ounce

3 tablespoons (jigger) = 1½ ounces

¼ cup = 2 ounces

cup = 3 ounces

cup = 3 ounces

½ cup = 4 ounces

½ cup = 5 ounces

¾ cup = 6 ounces

1 cup = 8 ounces

1 pint = 16 ounces

1 quart = 32 ounces

750 ml bottle = 25.4 ounces

1 liter bottle = 33.8 ounces

1 medium lemon = 3 tablespoons juice

1 medium lime = 2 tablespoons juice

1 medum orange =  cup juice

cup juice