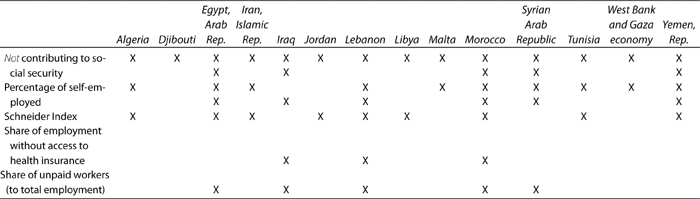

Table 1.1 Summary of Data and Definitions Used in This Report

Source: See annex table 1A.2 for information on data sources.

Note: For a detailed description of the micro-surveys used in this study, see the annex in chapter 2.

SUMMARY: This chapter provides general background on the basic measures of the prevalence of informal employment in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Informality is best understood as a complex, multifaceted phenomenon, which is determined by the relationship that the state establishes with private agents through regulation, monitoring, and provision of public services. Results indicate that some countries in the MENA region are among the most informal economies in the world. A typical country in MENA produces about one-third of its GDP and employs 65 percent of its labor force informally (using the Schneider Index and the share of the labor force without social security coverage, respectively). These stylized facts indicate that more than two-thirds of all workers in the region may not have access to health insurance and/or are not contributing to a pension system that would provide income security after retirement. At the same time, from a fiscal perspective, these results indicate that about one-third of total economic output in the region remains undeclared and, therefore, not registered for tax purposes.

There are many angles to informality. In his classic study, De Soto (1989) defines informality as the collection of firms, workers, and activities that operate outside the legal and regulatory framework. Overall informality can be studied through three main lenses: a firm-based productivity perspective, an employment perspective (workers), and a fiscal perspective (untaxed activities). Informality is a heterogeneous concept, comprising different situations such as the unregistered small firm, the street vendor, and the large registered (and hence “formal”) firm that employs some of its workers without offering written contracts or access to social security benefits:

• Firms: A generally accepted definition of “firm” informality was proposed by the Delhi Group in 1997. According to their definition, the informal sector includes private unincorporated enterprises (or quasi-unincorporated), which produce at least some of their goods and services for sale or barter, have fewer than five paid employees, are not registered, and are engaged in nonagricultural activities (ILO 2002). Studies generally measure informality at the firm level through a direct (micro-) measurement based on individual surveys, such as the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys, that explicitly ask the firm’s owner or manager for information on the years in which the firm started its operations and legally registered. A discrepancy between the two is typically considered the period during which the firm operated informally (Angel-Urdinola, Reis, and Quijada 2009).

• Workers: According to this definition, the informal sector is proxied by informal employment in either formal (small unregistered or unincorporated firms) or informal enterprises, with “informal employment” refereeing to the absence of benefit from or registration to social security or the absence of a written contract (see box 1.1. for more details on defining informality). Hence, informal sector employment includes informal employment in formal sector enterprises comprising (1) contributing family members and (2) employees; informal employment in informal sector enterprises comprising (1) own-account workers,1 (2) employers, (3) contributing family workers, (4) employees, and (5) members of producers cooperatives; and informal employment in households producing goods exclusively for their own final use and households employing paid domestic workers comprising (1) own-account workers and (2) employees.

• Untaxed Activities: From a fiscal point of view, a large informal sector constitutes a set of activities that are “hidden” for tax purposes. The United Nations System of National Accounts (EC and others 2008) distinguishes between four types of such activities: (1) informal activities, which are undertaken “to meet basic needs”; (2) underground activities, which are deliberately concealed from public authorities to avoid either the payment of taxes or compliance with certain regulations (for example, most cases of tax evasion and benefit fraud); (3) illegal activities, which generate goods and services forbidden by the law or which are unlawful when carried out by unauthorized producers; and (4) household activities, which produce goods and services for own-consumption.

If defining informality is a complex task, its measurement is even more daunting. Given that it is identified by working outside the legal and regulatory frameworks, informality is best described as a hidden, unobserved variable. Hence, accurate and complete measurement is not feasible, but an approximation is possible using indicators that reflect its various aspects. To provide an estimate of the magnitude of informality in a country, it is better to use a variety of different indicators that, taken together, can provide a more robust approximation to informality. Several direct and indirect methods are used to measure informality (Angel-Urdinola, Reis, and Quijada 2009):

• Survey methods: Informality could be measured directly using individual surveys, such as the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys, which explicitly ask the firm’s owner or manager for information on the years in which the firm started its operations and was legally registered. A discrepancy between the two is typically considered as the time when the firm operated informally. In some household or labor force surveys, interviewees are asked whether they have signed a formal contract in their current employment, or whether they are affiliated with the social security administration (meaning that they, or their employer, are contributing to a pension plan or another social protection program). A potential problem with direct measures is that the interviewee’s answer depends heavily on the phrasing of the question, and many interviewees might be reluctant to reveal their behavior (for example, in the case of firms).

• Tax audits: Tax-audit data can be used to determine the percentage of firms audited that evade taxes and to quantify the amount of tax underreporting as informal activity (as well as a firm’s legal status). The shortcoming is that tax audits are not conducted randomly typically, and hence the information is not representative of the population of firms (Perry and others 2007).

• National Accounts: An indirect method commonly used to estimate the size of the informal economy is the difference between aggregate income and aggregate expenditures from the National Accounts. This measure has the advantage of being conceptually simple. However, it has been used mainly in developed countries, because it requires independent calculations of aggregate income and expenditure.

• Multiple Indicator-Multiple Cause model: Another method that has been used recently is the Multiple Indicator-Multiple Cause (MIMIC) model, popularized by Schneider (2004), who applied it for 145 countries. This model assumes that although informal activity is not observable, its magnitude can be represented by a latent variable (in index form), and both its causes and effects can be observed and measured. This latent variable is then used in a set of two equations: First, the latent variable is the dependent variable, and its causes are the explanatory variables; second, the effects of informality are modeled as a function of the latent variable. The set of equations is then simultaneously estimated, and the fitted values of the latent variable are used to compute an estimate of the size of the informal sector as a share of GDP. This technique has been criticized because of the lack of theoretical support for the equations that are supposed to capture the causes and effects of informal activity. Nevertheless, its use remains widespread, probably as a consequence of the aforementioned difficulties to obtain broad estimates of informality.

Three indicators are commonly used to measure informality: the Schneider Index, lack of social security coverage, and prevalence of self-employment (Loayza and Wada 2010). The Schneider Index combines the MIMIC method, the physical input (electricity) method, and the excess currency-demand approach for the estimation of the share of production that is not declared to tax and regulatory authorities.2 Lack of social security coverage is often estimated as the fraction of the labor force (or employment) that does not contribute to a retirement pension scheme, as reported in the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. The prevalence of self-employment is often computed as the ratio of self-employment to total employment (as reported by the ILO). Additional measures, such as the share of total employment without health insurance and the share of unpaid workers in total employment, are also commonly used proxies of informality (Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011). Table 1.1 and box 1.2 present the different definitions used for MENA countries included in the study.

Table 1.1 Summary of Data and Definitions Used in This Report

Source: See annex table 1A.2 for information on data sources.

Note: For a detailed description of the micro-surveys used in this study, see the annex in chapter 2.

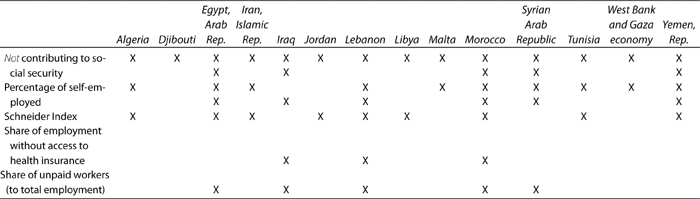

Although each indicator has its own conceptual and statistical shortcomings as a proxy for informality, taken together they provide a robust approximation to the issue. Cross-country scatter plots of the three measures of informality against each other provide evidence for the significant correlation among the three indicators, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.10 to 0.91 (which are high enough to represent the same phenomenon but not so high as to make them mutually redundant) (figure 1.1).3

Figure 1.1 Correlation among Most-Used Informality Indicators

Source: Processed from Loayza and Wada 2010.

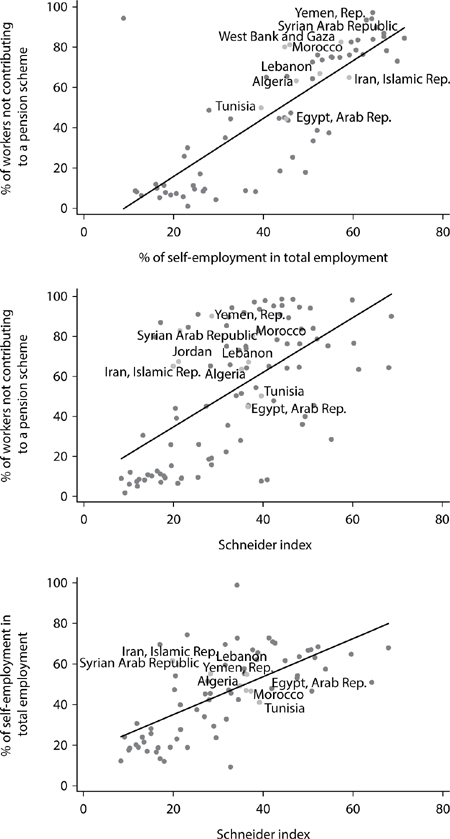

This report addresses informality from a worker’s perspective and focuses specifically on informal employment. Informal employment can be captured in many ways. Informal employment is often proxied as (1) the share of unpaid employment, (2) the share of self-employment, (3) the share of total employment not contributing to social security (Gasparini and Tornarolli 2006; Loayza and Rigolini 2006; World Bank 2009), and (4) the share of employees without a contract. Figure 1.2 displays the correlations among these different measures for countries where data are available. As illustrated by the correlations, not having access to social security is positively correlated with all other measures (and especially with not having access to health insurance), although the magnitude of the correlation varies by country and by strata (urban or rural). The strong and positive association between contributing to social security and having access to health insurance (in most cases both come bundled in the social security package) suggests also that informal workers are generally not covered against health risks.4 As seen in figure 1.2, unpaid work and self-employment are negatively correlated. This indicates that some features of informality among the self-employed are quite unique from those of unpaid workers. However, both of the aforementioned definitions are positively correlated with not having access to social security, indicating that the “share of overall employment not contributing to social security” is able to capture some of the features of informality inherent to these two different groups.

Figure 1.2 Correlations among Different Definitions of Labor Informality (Worker’s Side)

In the context of this report, the standard definition of informality will be the share of the labor force/employment that does not contribute to social security. In characterizing informal employment from the worker/social protection perspective, one core definition relates to the absence of workers’ coverage by traditional social security programs, most notably health insurance and pensions, but often also other benefits available to workers by virtue of their labor contract (Perry and others 2007). To ensure comparability across countries, and based on data availability, informal employment is defined herein as the share of overall labor force/employment not contributing to social security (and therefore not covered by a pension system and, in most cases, not covered by health insurance). Various advantages are found by selecting this definition. The first is data availability. As presented in Table 1.1, data used to proxy alternative definitions of workers’ informality, such as health insurance coverage, lack of contract, and unpaid employment, are not available for many countries in the MENA region. Second, the lack of social security coverage captures well different aspects of informal employment and thus is more likely to portray the common features of informal employment. In particular, as seen in figure 1.2, unpaid work and self-employment are negatively correlated, suggesting that some features of informality among the self-employed are quite different when compared with those of unpaid workers. However, both of these definitions are positively correlated with not having access to social security, indicating that this definition is able to capture some of the features of informality inherent to these two very different groups. Finally, the definition has been used often in other regional studies on informality, which allows for comparability between MENA and other world regions (ILO 2002; Perry and others 2007; World Bank 2009).

There are costs and benefits to informality. In many countries the informal sector often represents a very resourceful part of the economy and is a source of creativity and dynamism. However, important costs are associated with informality, such as unprotected work, low firm productivity, and tax evasion. A traditional view of informality argues that, in general, workers and firms in the informal sector would prefer to be formal (such as by registering with the state, paying taxes, or being affiliated with social security), but regulatory and administrative barriers prevent them from doing so. As argued by Perry and others (2007), however, considerable evidence in Latin America suggests that the informal sector is fairly heterogeneous, with workers and firms that have been excluded from the formal economy coexisting with others that have opted out on the basis of implicit cost-benefit analyses. This latter concept of “exit” posits that at least some of those in the informal sector are there as a matter of choice. Specifically, some workers and firms, upon making some implicit or explicit assessment of the benefits and costs of formality, actually prefer operating informally. A wide range of degrees to which exit or exclusion holds in any economy are found. Hence, these two perspectives are complementary characterizations rather than competing hypotheses.

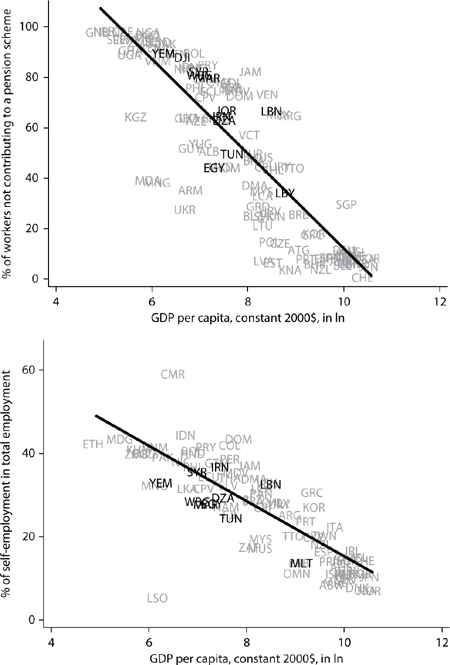

Informality is a fundamental characteristic of underdevelopment. As depicted in figure 1.3, a larger informal sector is often associated with lower GDP per capita. For most countries in the region, the share of informal to total employment is mostly aligned where it should be given the level of economic development. A two-way relationship can explain the strong and negative association between informality and economic development. On the one hand, widespread informality induces firms to remain suboptimally small, use irregular procurement and distribution channels, and constantly divert resources to mask their activities or bribe officials. As such, informality may be a source of economic retardation because it is associated with misallocation of resources and loss of the advantages of legality (such as police and judicial protection, access to formal credit institutions, and participation in international markets) (Loayza and Wada 2010). On the other hand, low levels of economic development affect the capacity and quality of institutions to enforce regulation, collect taxes, and provide services that firms deem worth paying for through taxation (such as social security and infrastructure). At the same time, a powerful spurious effect could drive this association, because informality and low income could result from policies and institutions that affect negatively both. Measurement issues might also affect this correlation, because in countries with higher informality more GDP escapes formal measurement. Informality also has positive implications for the labor market, because it provides employment to a significant share of the population, may be a source of innovation and entrepreneurship (many firms start operating informally when they are small and formalize as they grow), and serves as a safety net in periods of transition. As such, at a given level of distortion, it is preferable to a fully formal economy where agents are unable to circumvent regulation-induced rigidities and would not otherwise be able to exist without the flexibility provided by the informal sector.

Figure 1.3 Informality and Economic Development

Source: Loayza and Wada 2010.

Note: GDP = gross domestic product.

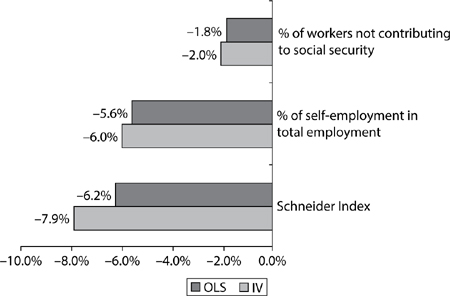

The evidence suggests that higher levels of informality are associated with lower levels of economic growth. Loayza and Wada (2010) conducted a simple regression analysis of the association between informality and growth for all countries for which data are available (that is, using the Schneider Index, self-employment as a share of total employment, and share of the labor force not contributing to social security). Using all available informality proxies, the authors find that higher informality is associated with lower economic growth. The dependent variable is the average growth of GDP per capita over 1985–2005. Loayza and Wada (2010) consider a period of about 20 years for the measure of average growth to achieve a compromise between merely cyclical, short-run growth (which would be unaffected by informality) and very long-run growth (which could be confused with the sources, rather than consequences, of informality). They include a proxy for the overall capacity of the state as a control variable (level of GDP per capita and initial ratio of government expenditures to GDP) in the regression. The explanatory variables of interest are the three informality indicators, considered one at a time. Regression analysis uses both ordinary least-squares (OLS) and instrumental-variable (IV) methods. It should be noted, however, that results from cross-country regressions often encounter skepticism because of the many potential sources of spurious correlation. The authors’ estimates indicate that controlling for the country’s initial level of expenditures and GDP, an increase of one standard deviation in any of the informality indicators leads to a decline of 0.7−1 percentage points in the rate of GDP per capita growth (figure 1.4). Loayza, Oviedo, and Serven (2005) identify informality as one of the main channels through which regulation affects growth, with a heavier regulation burden reducing growth and inducing higher informality.

Figure 1.4 Effect of Informality on Growth

Source: Processed from Loayza and Wada 2010.

Note: IV = instrumental variable; OLS = ordinary least-squares.

Important adverse consequences of labor informality on other human development outcomes are seen, such as less protection at old age, lower access to and affordability of “quality” health care, and reduced employment quality (high working hours, unsafe conditions, and low pay). Social insurance systems in most MENA countries are historically based on Bismarckian principles, whereby pension, health, and disability benefits are linked to employment in the formal sector. As a result, formal sector actors (public and private sectors, employers and employees) have contributed to social security programs and in return have been covered by relatively generous, multidimensional benefit packages. Those outside the formal sector, in both urban and rural areas, have traditionally had limited or no access to formal risk management instruments or other government benefits. At the same time, noncontributory antipoverty and social protection programs developed recently in MENA remain limited in scope and reach, in most cases, a very narrow portion of society. In this sense, nearly all MENA countries are characterized by “truncated welfare systems.” Informal workers in MENA are likely to use inadequate mechanisms to cope with social risks, such as informal and less effective social safety net arrangements or by selling assets or withdrawing children from school (which can have long-term adverse consequences). Emerging evidence also finds that informality is associated with lower life expectancy and health outcomes. Using data from the Republic of Yemen, Cho (2011) finds that, controlling for other factors, individuals living in households having a head working in the formal sector are associated with better health outcomes: lower malnutrition for children, low out-of-pocket expenses, and low adult morbidity.

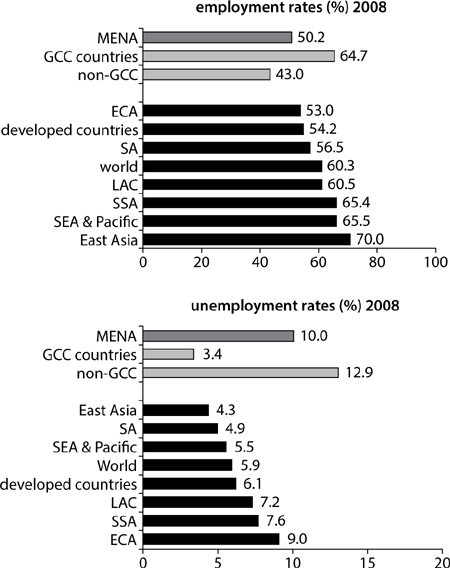

On average, the MENA region displays lower levels of employment and higher levels of unemployment than any other region in the world. Some basic macroeconomic trends comparing the MENA region to other regions in the world and, within MENA, non-GCC to GCC members are presented to provide context to the analysis that follows.5 The level of economic development and other macroeconomic variables, such as recent economic growth and employment composition, are likely to be important factors for understanding a country’s profile and determinants of informality. Figure 1.5 illustrates the patterns of employment in MENA (subdivided into non-GCC and GCC countries) versus other regions. Differences between GCC and non-GCC countries are notable. GCC countries display high employment rates and low unemployment rates in comparison to the rest of the world. On the other hand, non-GCC countries show low employment rates (mainly because of low levels of female employment) and by far the highest unemployment rates in the world (at 13 percent in 2008).

Figure 1.5 Employment and Unemployment Rates in MENA

Source: World Development Indicators dataset.

Note: ECA = Europe and Central Asia; GCC = Gulf Cooperation Council countries; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SA = South Asia; SEA = Southeast Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa.

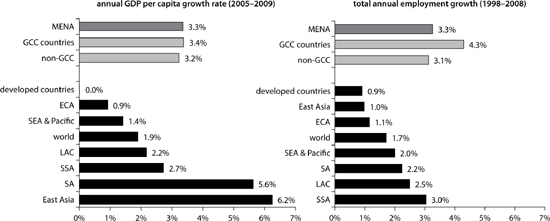

In recent years, MENA countries have displayed positive economic growth and rapid employment growth, especially for women. Although annual GDP per capita growth rates among GCC and non-GCC countries have been rather similar in recent years and generally above the world average, annual employment growth rates have been significantly larger for GCC than for non-GCC countries (suggesting that GCC countries show higher employment elasticities to growth) (figure 1.6). In the MENA region, as in many other regions in the world, employment growth rates for the period 1998–2008 have been higher for women than for men. In particular, during this period, the growth rate of female (male) employment was 6.4 percent (4.2 percent) in GCC countries and 3.8 percent (2.9 percent) in non-GCC countries. Despite such rapid increases in female employment, female employment levels in the region remain the lowest in the world.

Figure 1.6 Economic Growth and Employment Growth

Source: World Development Indicators dataset.

Note: ECA = Europe and Central Asia; GCC = Gulf Cooperation Council; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SA = South Asia; SEA = Southeast Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa.

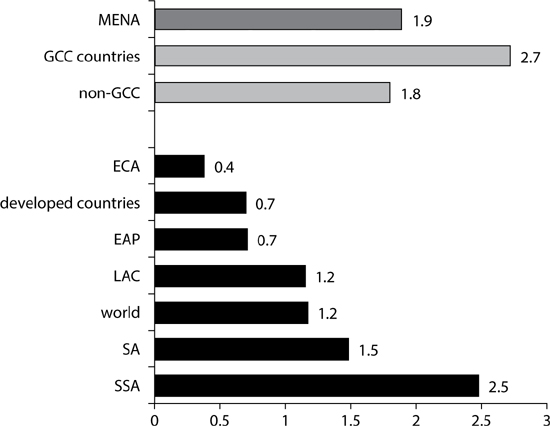

At the same time, population growth in the MENA region has been faster than in other regions. Annual population growth of 1.9 and 2.7 percent per year in GCC and non-GCC countries, respectively (figure 1.7), is among the highest in the world (and equivalent to those in Sub-Saharan Africa). While MENA countries created jobs at a higher pace than other countries in the world, the level of employment creation did not keep pace with population growth. Unemployment rates in GCC countries remain low at the time this report was written, but rapid population growth (especially if these countries continue to receive flows of international migrants) poses important potential risks for increasing unemployment and informality.

Figure 1.7 Annual Population Growth Rates (%) (2005–2009)

Source: World Development Indicators dataset.

Note: ECA = Europe and Central Asia; GCC = Gulf Cooperation Council countries; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SA = South Asia; SEA = Southeast Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa.

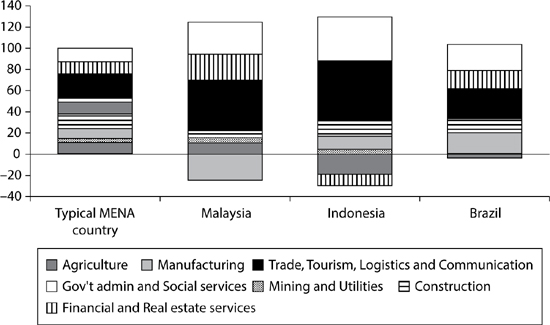

MENA countries differ significantly from other middle-income countries in the composition of employment generation (World Bank 2011). In the typical country in MENA, agriculture contributes to a larger extent to employment growth than in other middle-income countries. In other regions, there was a shift of labor away from agriculture towards services. In the typical MENA country, the contribution of manufacturing and private services, especially the trade, tourism, logistics and communication sectors (figure 1.8) is low. These sectors were the main contributors to employment growth in comparable middle income countries (such as Malaysia or Indonesia). Hence, jobs created in the typical MENA country were low-quality jobs, skewed toward low value-added sectors, which reflects the lack of structural transformation. In GCC countries, employment growth took place largely in the construction sector (jobs taken up by expatriates) and the creation of higher paid public sector jobs directed to nationals.

Figure 1.8 Sectoral Contribution to Annual Employment Growth in Typical MENA Country and Selected Other Countries, Average for 2000s

Source: World Bank 2013.

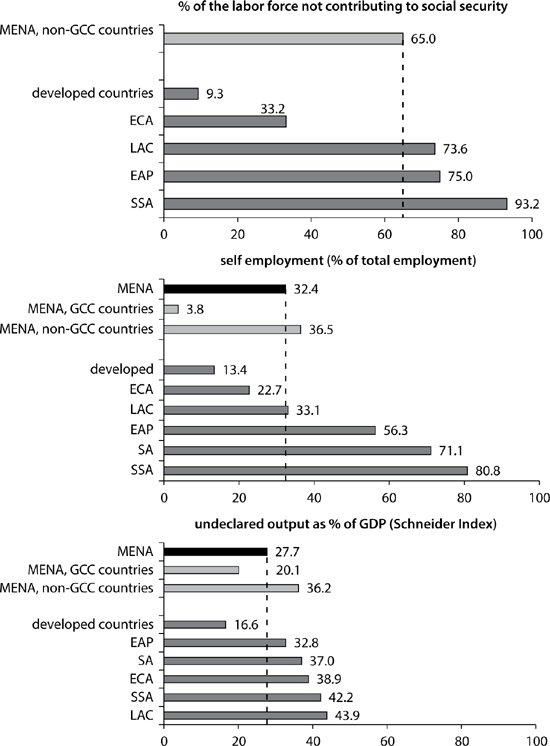

A typical country in MENA produces about 28 percent of its GDP and employs 65 percent of its labor force informally. Using available data, Loayza and Wada (2010) assess the prevalence of informality in MENA using three commonly used proxies of informality: (1) the Schneider Shadow Economy Index, (2) the share of the labor force not contributing to social security, and (3) the share of self-employment to total employment (figure 1.9). These stylized facts indicate that more than two-thirds of all workers in the region may not have access to health insurance and/or are not contributing to a pension system that provides income security after retirement age. At the same time, from a fiscal perspective, these results indicate that about one-third of total economic output in the region remains undeclared and therefore, not registered for tax purposes.

Figure 1.9 Prevalence of Informality in MENA versus Other Regions

Source: Schneider et al., 2010 for Schneider Index; WDI for self employment and pension scheme.

Note: EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; GCC = Gulf Cooperation Council; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SA = South Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa. The periods covered are the latest years in 2000–10 for pension scheme, 2000–11 for self-employment, and 1999–2007 for the Schneider index, respectively. Data on social security contributions in GCC countries are only available for Bahrain, 2007 (20 percent), and Qatar, 2008 (4.4 percent) (Palleres-Miralles, Romero, and Whitehouse 2012).

The degree of informality in the median country in MENA is lower than that of most developing countries, but much higher than that of the median developed country. As illustrated by figure 1.9 and using the lack of coverage measure, the typical MENA country has a labor informality rate larger than ECA, and lower than LAC, EAP, SA, and SSA. Using the Schneider Index, the median country in MENA has a lower informal production than the other developing regions. Using the share of self-employed, a typical MENA country is as informal as a typical country in LAC, more informal than a typical country in ECA, and less informal than a typical country in EAP, SA, and SSA.

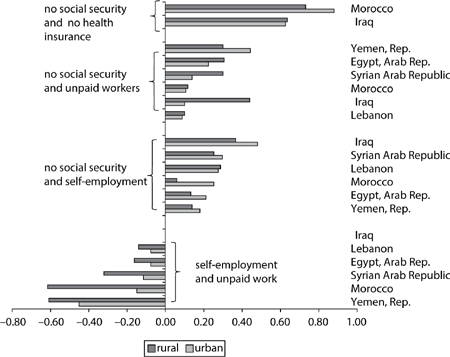

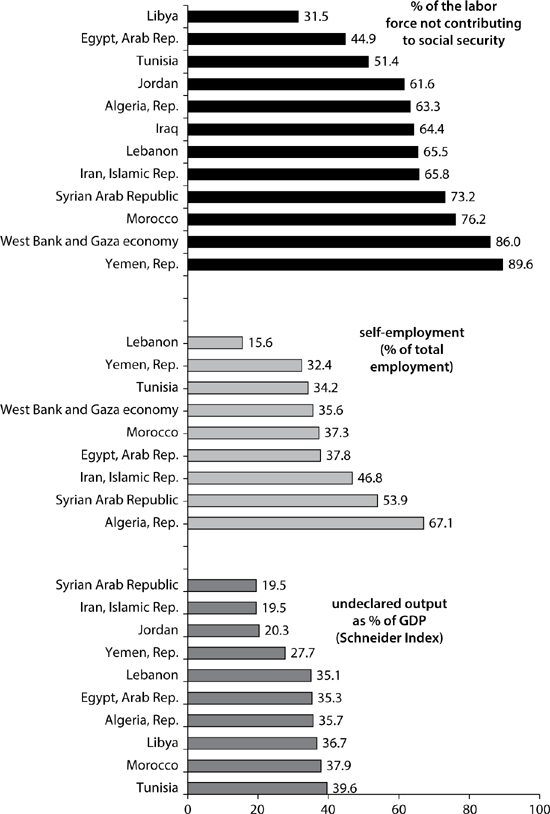

Important variations are found in the prevalence of informality across non-GCC countries, depending, among other factors, on the availability of natural resources and labor. Non-GCC countries are quite heterogeneous in terms of size, availability of resources and labor, economic development, and demographic structure, all factors that influence the size of the informal economy (see chapter 2 for a more thorough discussion). The prevalence of informality varies significantly across countries in this group (figure 1.10). In general, resource-rich/labor-abundant economies (such as the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Syrian Arab Republic) tend to display high informality rates in the region as proxied by the share of the labor force not contributing to social security (between 66 and 73 percent) and by the share of self-employment to total employment (between 32 and 54 percent). However, their share of undeclared output to total GDP (at around 20 percent) is comparable to that of GCC countries. This occurs because this group of countries generally has few, but large, formal firms (many in the energy sector) that are capital intensive, thus rendering lower informality in production than in labor (Loayza and Wada 2010). On the contrary, resource-poor/labor-abundant economies (such as Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco) display a high share of undeclared output (between 35 and 40 percent of GDP) and a lower share of the workforce not contributing to social security (between 45 and 76 percent), which is consistent with a higher share of medium size (and semiformal) labor-intensive firms.

Figure 1.10 Correlation among Most-Used Informality Indicator

Source: Processed from Loayza and Wada 2010.

Note: Time periods are as follows: Schneider Index, average 1999–2007; self-employment, 1999–2007; not contributing to social security (S.S.), 2000–2007.

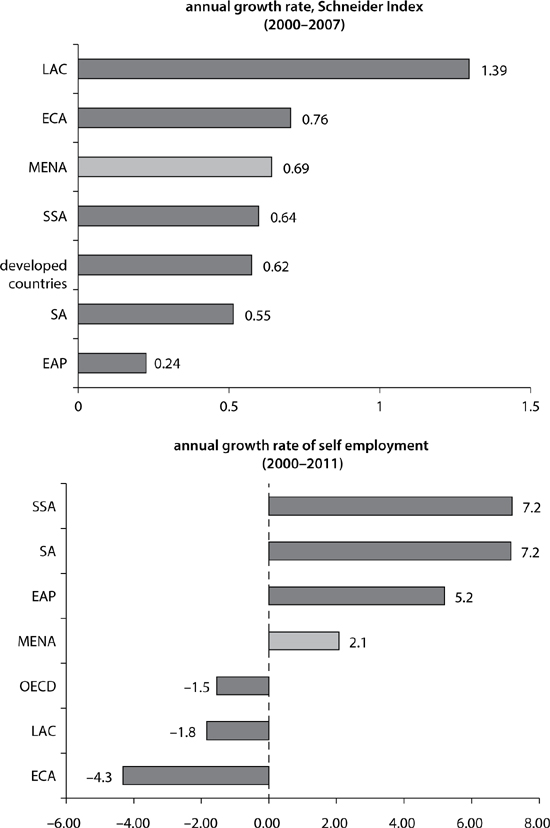

Informality in the MENA region has been rising in recent years, as proxied by the Schneider Index and the share of self-employment to total employment. However, the increase in the share of undeclared/informal output to total GDP in recent years has been a global trend (figure 1.11). Within the region, important differences are seen in the growth rate of informality between GCC and non-GCC countries. First, informality, as proxied by the Schneider Index, has been growing faster in non-GCC countries than in GCC countries. Second, although self-employment has been rising in non-GCC countries, it has been declining rapidly in GCC countries. It is worth noting that self-employment in non-GCC countries (at 37 percent) remains somewhat lower than in other developing regions such as South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (71 and 81 percent, respectively) (Loayza and Wada 2010).

Figure 1.11 Annual Growth Rates of Informality

Source: Processed from Loayza and Wada 2010.

Note: EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SA = South Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa.

This report focuses its analysis and discussion on non-GCC MENA countries. A discussion of the aggregate trends in GCC and non-GCC countries is important to provide a comprehensive overview of informality throughout the region, but the different dynamics in labor markets in GCC and non-GCC MENA economies and the lack of micro-data make in-depth analysis of the informality phenomenon in GCC countries outside the scope of this report. Hence, all results from this point forward focus only on non-GCC countries, and any references to “MENA” need to be understood to refer to only non-GCC countries.

Informality can be the result of exclusion or of a rational exit in opting out of the coverage system. The option to participate in the informal sector reflects cost and benefit considerations but is not always voluntary or desirable (Loayza and Wada 2010). From the perspective of a worker or a firm, joining the informal sector can be seen as either “exiting” the legal framework or “being excluded” from it. In the former case the informality option implies a voluntary decision, whereas in the latter it is derived from segmentation or segregation. In both cases, however, what matters is that informality in the economy results from a combination of factors affecting the potential gains, costs, and restrictions related to legally established firms and workers. Formality entails costs of entry (in the form of lengthy, expensive, and complicated registration procedures) and costs of permanence (including payment of taxes, compliance with mandated labor benefits and remunerations, and observance of environmental, health, and other regulations). The benefits of formality potentially consist of police protection against crime and abuse, recourse to the judicial system for conflict resolution and contract enforcement, access to legal financial institutions for credit provision and risk diversification, and, more generally, the possibility of expanding markets both domestically and internationally. At least in principle, formality also reduces the need to pay bribes and prevents incurrence of penalties and fees to which informal firms are likely subjected. Informality is more prevalent when the regulatory framework is burdensome, the quality of government services to formal firms is low, and the state’s monitoring and enforcement power is weak (Friedman and others 2000; Johnson and others 1997; Loayza and Rigolini 2009; Schneider and Enste 2000). According to Galal (2005), the current regulatory framework in Egypt, for instance, discourages formality, leading to an annual loss in tax revenues equivalent to 1 percent of GDP.

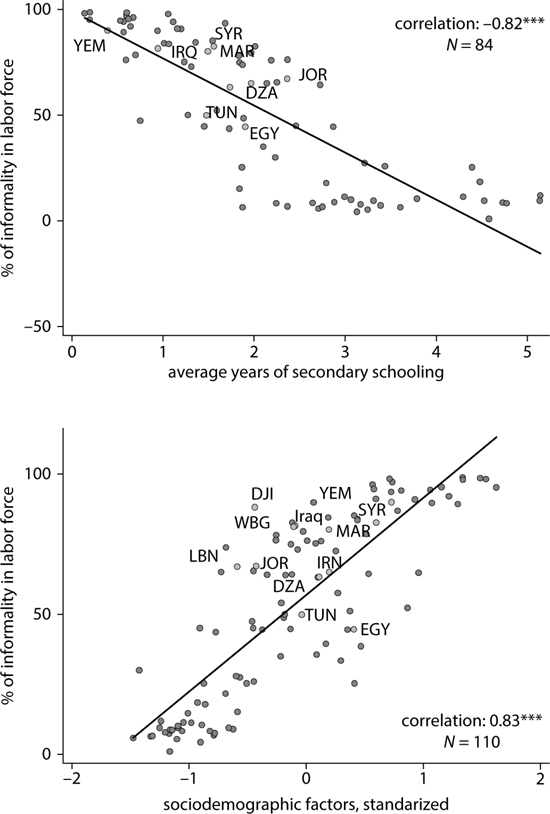

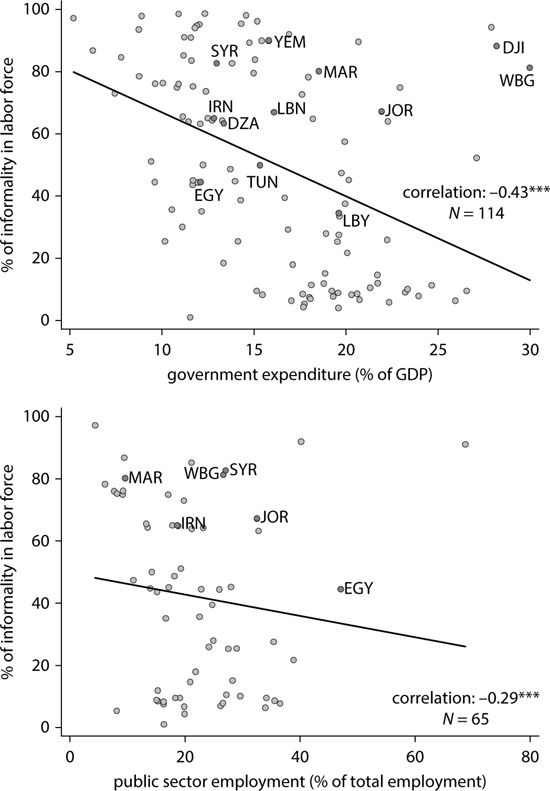

The prevalence of informality depends on structural characteristics of countries, such as governance, productivity, and economic composition. Loayza and Wada (2010) analyze the structural factors that influence informality: (1) a country’s governance structure and regulatory framework (which will affect the opportunity cost of informality), (2) labor productivity, demographics, and employment composition, and (3) the size of the public sector. To illustrate the relative importance of these determinants, Loayza and Wada (2010) first calculate a series of correlations between proxies for the aforementioned factors and the level of informality (as proxied by the share of the labor force not contributing to social security) for all countries where data are available. The authors find that, remarkably, the majority of correlation coefficients between these structural factors and informality are statistically significant, ranging between 0.29 and 0.83. Second, the authors use cross-country regression analysis to evaluate the importance of each proposed explanation regarding the causes of informality. The authors’ regression results indicate that law and order, business regulatory freedom, education, and sociodemographic factors are all remarkably robust determinants of informality, with informality decreasing as these factors improve. Similarly, informality decreases when the production structure shifts away from agriculture and when demographic pressures from youth and rural populations decline. The main results are summarized as follows:

• Governance and regulation: A country’s governance structure will directly affect the opportunity cost of informality. The prevalence of informality is influenced by the extent to which countries enforce law and regulation (more enforcement is associated with more compliance, especially if penalties are costly) and by the level of labor market regulatory freedom (more regulation/higher labor costs provide incentives for firms to bypass regulation) (figure 1.12).6 Controlling for other factors, Loayza and Wada (2010) find that a 1 percent increase in the index of business regulatory freedom (index of law and order) is associated with 5 to 6 (2 to 3) percent lower informality worldwide.

• Productivity, demographics, and employment composition: A higher level of education is associated with lower informality because investments in human capital increase productivity and hence make business regulations less onerous and formal returns potentially larger. Other things equal, Loayza and Wada (2010) find that an additional year of education of the labor force is associated with a 5 to 6 percent lower level of informality worldwide (figure 1.13). Furthermore, a production structure tilted toward agriculture, rather than toward the more complex processes of industry, favors informality by making legal protection and contract enforcement less relevant and valuable. Finally, a demographic composition with larger shares of youth or rural populations is likely to increase informality by making monitoring more difficult and expensive, by placing bigger demands on resources for training and acquisition of abilities, by creating bottlenecks in the initial school-to-work transition, and by making the expansion of formal public services more problematic (Fields 1990; ILO 2004; Schneider and Enste 2000).7

• Size of the public sector: Informality may also be affected by the size of public sector. Informality tends to be less prevalent in economies with a larger state presence (figure 1.14). In fact, in economies heavily dominated by the state, informality is practically nonexistent, as in the former Soviet Union and other communist countries in Eastern Europe. The influence of the state on informal employment can be direct, through the absorption of labor and economic production. This is especially important for the MENA region, given the state’s traditionally important role as source of formal employment. The influence can also be indirect, through the links that the government establishes with private firms, by requiring them to register officially and comply with its regulations. Furthermore, given a sufficient level of quality, the size of the government can affect the state’s ability to monitor and enforce formal taxes and regulations.8

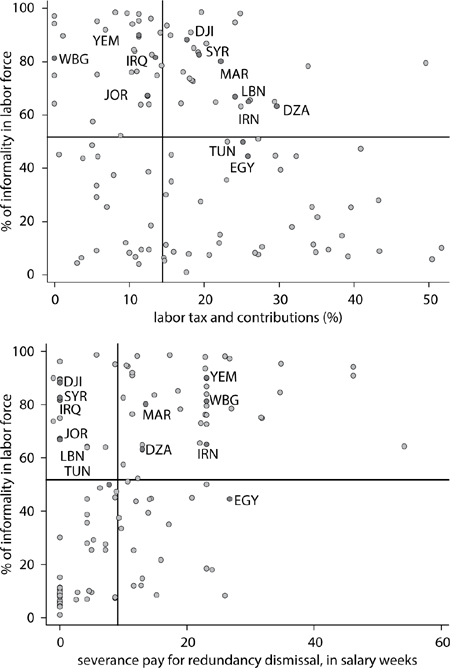

• Labor costs: Demand for formal employment will be determined by direct and indirect labor costs relative to informal workers. Higher indirect costs of labor, generally in the form of stricter employment protection legislation and/or high labor taxes, are associated with higher levels of informality (Botero and others 2004; Djankov and Ramalho 2009; Grubb and Wells 1993). This is likely to be important in MENA, where, compared with international benchmarks, firing regulations are rather strict and labor taxes are rather high (Angel-Urdinola and Kuddo 2010). Figure 1.15 illustrates proxies for indirect labor costs (labor taxes and severance pay for redundancy dismissals) using available data from the Doing Business 2011 dataset and compares a selected group of non-GCC countries with respect to the world median (represented by the horizontal and vertical lines in the figure). Some economies in the region that display high levels of informality (such as Morocco, Syria, Lebanon, West Bank and Gaza economy, and Algeria) are also associated with high levels of labor taxes and with high severance payment schemes. Although some authors find a positive and significant relationship between the generosity of severance pay schemes and informality, the relationship between labor taxes and informality is inconclusive here (that is, some countries from ECA and OECD display high levels of labor taxes and low levels of informality).

Figure 1.12 Correlation between Informality and Governance/Regulation

Figure 1.13 Correlation between Informality and Education/Demographic Factors

Source: Processed from Loayza and Wada 2010.

Figure 1.14 Correlation between Informality and Government Size

Source: Processed from Loayza and Wada 2010.

Figure 1.15 Correlation between Informality and Indirect Labor Costs

Source: Based on Doing Business 2011 data.

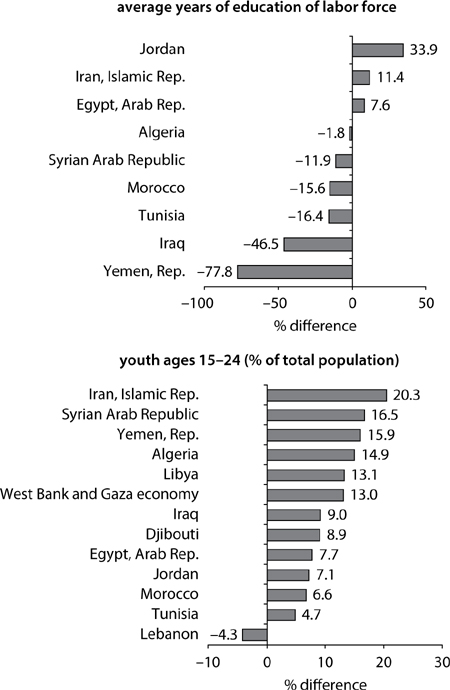

MENA’s large youth bulge and educational deficit has important implications for the region’s prevalence of informality. Loayza and Wada (2010) illustrate the importance of structural factors on informality for a selected group of countries in the MENA region where data are available. The authors find that MENA countries, while being quite heterogeneous, have characteristics that are associated with higher prevalence of informality. In particular, MENA countries have a large youth bulge and still display important education deficits. As mentioned before, countries with a larger youth to total population ratio are associated with higher informality levels. The right-hand panel of Figure 1.16 illustrates the percentage difference between the youth bulge in MENA versus the world’s median for a selected group of countries. Results indicate that with the exception of Lebanon, the youth bulge for all other countries in the region is larger than the world’s median (ranging from 5 percent in Tunisia to 20 percent in the Islamic Republic of Iran). At the same time, some countries in the region, such as Iraq and the Republic of Yemen, display important education deficits, which are associated with lower levels of productivity (and thus higher levels of informality).

Figure 1.16 Percentage Difference in Education and Youth Bulge with Respect to the World Median

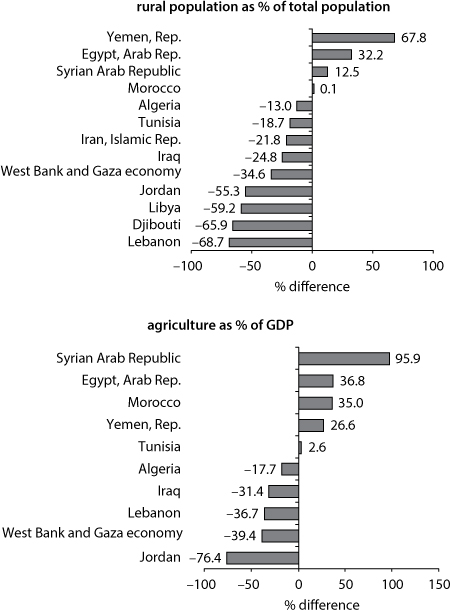

Some countries in the region remain very rural by world standards. As illustrated by Figure 1.17, the share of total population living in rural areas in countries such as the Republic of Yemen, Syria, Egypt, and Morocco is high by world standards. Not surprisingly, in these economies the share of agricultural to total economic output tends to be a larger component of the total economy. Because the agricultural sector remains largely informal in developing countries, countries with relatively large agricultural sectors will likely display higher informality rates than countries with relatively small agricultural sectors (such as Jordan and Lebanon).

Figure 1.17 Percentage Difference in Rural Population and Agricultural Output with Respect to the World Median

Source: Processed from Loayza and Wada 2010.

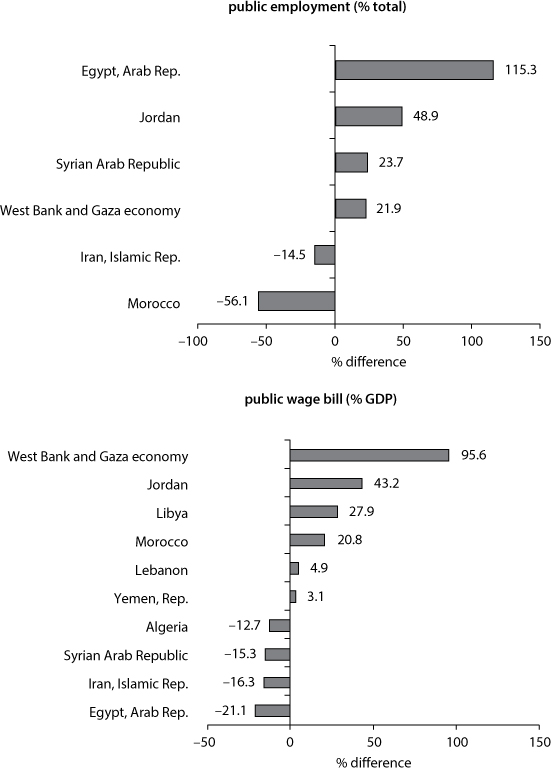

Finally, the public sector still plays a major employment and economic role in many countries in the region. Almost by definition, the large majority of employment in the public sector is formal. As such, controlling for other factors, countries with relatively larger public sectors are likely to be associated with lower prevalence of informality. Figure 1.18 indicates that some countries in the region (such as Egypt, Jordan, and Syria) have public sectors that are quite large by international standards.

Figure 1.18 Percentage Difference in Public Employment with Respect to the World Median

Source: Processed from Loayza and Wada 2010 and WDI dataset.

Informality is a fundamental characteristic of underdevelopment. Higher levels of informality are associated with lower levels of economic growth. Widespread informality implies that a large number of people and economic activities operate outside the legal-institutional framework. International evidence indicates that widespread informality induces firms to remain suboptimally small, use irregular procurement and distribution channels, and constantly divert resources to mask their activities or bribe officials. Conversely, formal firms will be able to use resources with less regulatory restrictions, which enables them to be less labor intensive compared with their country’s labor endowments. Informality may also be a source of further economic retardation because it is associated with misallocation of resources and entails losing the advantages of legality, such as police and judicial protection, access to formal credit institutions, and participation in international markets. At the same time, informality constitutes an important source of employment growth and of dynamism in many economies.

Important adverse consequences of labor informality on human development outcomes are found. Informal workers in MENA have limited or no access to formal risk management instruments to cope with social risks. Social insurance systems in most MENA countries historically have been based on Bismarckian principles, in which formal sector actors (public and private sectors, employers and employees) contributed to social security programs, in return for relatively generous, multidimensional benefit packages, often including health insurance, old-age pension, disability and workers’ insurance, and, in some cases, housing, child care, and sports and recreation benefits. Those outside the formal sector, in both urban and rural areas, have had limited or no access to formal risk management instruments or other government benefits. As a result, informal workers cope with many risks though informal safety net arrangements.

Although not as high as in other developing regions, informal employment is rather prevalent in most MENA countries. Moreover, in some of them, informality is nearly as high as in the most informal countries in the world. This observation is important because a large informal sector denotes misallocation of resources (labor in particular) and inefficient utilization of government services, which can jeopardize the countries’ growth and poverty-alleviation prospects. A typical country in MENA produces about one-third of its GDP and employs 65 percent of its labor force informally (using the Schneider Index and the share of the labor force without social security coverage, respectively). These are remarkable statistics, especially from a human development perspective. These stylized facts indicate that more than two-thirds of all workers in the region may not have access to health insurance and/or are not contributing to a pension system that would provide income security after retirement age. At the same time, from a fiscal perspective, these results indicate that about one-third of total economic output in the region remains undeclared and, therefore, not registered for tax purposes.

Important variations are seen in the prevalence of informality across non-GCC MENA countries, depending on the availability of natural resources and labor. Resource-rich/labor-abundant economies (such as the Islamic Republic of Iran, Syria, and the Republic of Yemen) tend to display the highest labor informality rates in the region (as proxied by the share of the labor force not contributing to social security and the share of self-employment to total employment) but low undeclared output to total GDP (explained by the capital intensity of their production). Resource-poor/labor-abundant economies (such as Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, and Morocco) display a high share of undeclared output and a lower share of the workforce not contributing to social security, likely reflecting their higher share of medium size (and semiformal) labor-intensive firms.

Still, not all is negative about informality: The informal sector is likely to be an important mechanism for employment transition, especially among youth. Given that informality entails misallocation of resources and lower growth, should it be reduced at all costs? The answer to this important policy question is “no.” Although informality is suboptimal with respect to a situation of streamlined regulations and adequate provision of public services, it is indeed preferable to a fully formal economy that is unable to circumvent its regulation-induced rigidities. Also, the informal sector could be an important source of economic dynamism and may provide some needed flexibility for small firms to grow and operate productively. The crucial policy implication is that the mechanism of formalization matters greatly for its effects on employment, efficiency, and growth. If formalization is based purely on enforcement, it will likely lead to unemployment and low growth. On the other hand, if it is based on improvements in both the regulatory framework and the quality and availability of public services, it will bring about more efficient use of resources and higher growth. Also, the informal sector is a mechanism for workers to cope with unemployment risks and/or a sector of employment transition, especially for youth as they acquire experience.

Annex table 1A.2 Definitions and sources of variables Used in regression Analysis

Variable |

Definition and construction |

Source |

Non-contributor to pension scheme |

Labor force not contributing to a pension scheme as the percentage of total labor force. Average of 2000–2007 by country. |

World Development Indicators, various years |

Self-employment |

Self-employed workers as percentage of total employment. Country averages but periods to compute the averages vary by country. Average of 1999–2007 by country. ECA countries are excluded (Loayza and Rigolini 2006). |

ILO, data retrieved from laborsta.ilo.org |

Schneider Shadow Economy index |

Estimated shadow economy as a percentage of official GDP. Average of 1999–2007 by country. |

Schneider 2007; Schneider, Buehn, and Montenegro 2010 |

Law and Order |

An index ranging 0 to 6 with higher values indicating better governance. Law and Order are assessed separately, with each subcomponent comprising 0 to 3 points. Assessment of Law focuses on the legal systems, and Order is rated by popular observance of the law. Average of 2000–2007 by country. |

PRS group, data retrieved from https://www.prsgroup.com |

Business Regulatory Freedom |

An index ranging 0 to 10 with higher values indicating less regulated. It is composed of following indicators: (1) price controls; (2) administrative requirements; (3) bureaucracy costs; (4) starting a business; (5) extra payments/bribes; (6) licensing restrictions; and (7) cost of tax compliance. Average of 2000–2007 by country. |

Gwartney, Lawson, and Norton 2008, the Fraser Institute. Data retrieved from www.freetheworld.com |

Labor Regulatory Freedom |

An index ranging 0 to 10 with higher values indicating less regulation. It is composed of following indicators: (1) minimum wage; (2) hiring and firing regulations; (3) centralized collective bargaining; (4) mandated cost of hiring; (5) mandated cost of worker dismissal; and (6) conscription. Average of 2000–2007 by country. |

Gwartney, Lawson, and Norton 2008, Fraser Institute, data retrieved from www.freetheworld.com |

Average years of secondary schooling |

Average years of secondary schooling in the population aged 15 and over. The most recent score in each country is used. |

Barro and Lee 1993, 2001, and calculations |

Sociodemographic factors |

Simple average of following three variables: (1) youth (aged 10–24) population as a percentage of total population; (2) rural population as a percentage of total population; (3) agriculture as a percentage of GDP. All three variables are standardized before the average is taken. Average of 2000–2007 by country. |

Calculations with data from World Development Indicators, ILO, and the UN |

Public sector employment |

Public sector employment as a percentage of total employment. Country averages but periods to compute the averages vary by country. Average of 2000–2007 by country. |

ILO, data retrieved from laborsta.ilo.org |

Government expenditure |

General government final consumption expenditure as a percentage of GDP. Country averages but periods to compute the averages vary by country. Average of 2000–2007 by country. |

World Development Indicators, various years |

Note: ECA = Europe and Central Asia; GDP = gross domestic product; ILO = International Labour Organization; UN = United Nations.

1. Own-account workers are workers working on their own account or with one or more partners, holding a job defined as a self-employed job, and not having engaged on a continuous basis any employees to work for them during the reference period (ILO 1993).

2. The currency demand method was developed by Tanzi (1980, 1983) who assumes that transactions in the informal economy take place in the form of cash payments, which are most easily hidden from authorities. Hence, an increase in informality is likely to go hand in hand with an increase in currency demand. The excess demand for currency is estimated econometrically, controlling for factors traditionally associated with currency demand (such as income and interest rates) as well as factors associated with an increase of activity in the informal economy (such as direct/indirect tax burden, government regulation). The physical input (electricity consumption) method takes electricity consumption as a proxy for overall economic activity. Kaufmann and Kaliberda (1996) estimate the growth of the informal economy as the difference between the growth rate of official GDP and the growth rate of electricity consumption.

3. Additional descriptive statistics on these three informality indicators for countries in MENA are presented in the annex.

4. In all countries included in the analysis there is a positive correlation (ranging from 0.17 in the Republic of Yemen and 0.45 in Iraq) between being self-employed and not contributing to social security and a positive correlation (from 0.10 in Lebanon to 0.40 in the Republic of Yemen) between being an unpaid worker and not contributing to social security. At the same time, in all countries included in the sample, there is a negative correlation between being an unpaid worker and being self-employed (from −0.11 in Lebanon to −0.51 in the Republic of Yemen). This indicates that not contributing to social security captures some of the aspects of informality faced by both unpaid workers and self-employed, which are two very different groups. Correlations are available upon request.

5. Economies that belong to the non-GCC MENA group are Algeria, the Arab Republic of Egypt, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, and the Republic of Yemen as well as the West Bank and Gaza economy. Countries that belong to the GCC MENA group are Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

6. Law enforcement is measured by the Index on the Prevalence of Law and Order obtained from The International Country Risk Guide. The index is a proxy for both the quality of formal public services and the government’s enforcement strength. To measure labor regulation, the Index of Business Regulatory Freedom and Labor Market Regulatory Freedom is used, taken from Fraser Foundation’s Economic Freedom of the World report.

7. Labor productivity is proxied by (1) the average years of secondary schooling of the adult labor force (from Barro and Lee 2001) and (2) an index of sociodemographic factors composed of the share of youth in the population, the share of rural population, and the share of agriculture in GDP, obtained from the WDI dataset.

8. Government size is proxied by (1) the share of employment in the public sector to total employment (from ILO’s LABORSTA dataset) and (2) government consumption expenditure as a percentage of GDP (from WDI).

Angel-Urdinola, D., and A. Kuddo. 2010. “Key Characteristics of Employment Regulation in the Middle East and North Africa.” SP Discussion Paper 1006. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Angel-Urdinola, D., J. G. Reis, and C. Quijada. 2009. “Informality in Turkey: Size, Trends, Determinants and Consequences.” Mimeo. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Angel-Urdinola, D., and K. Tanabe. 2011. “Micro-Determinants of Informal Employment in the Middle East and North Africa Region.” Mimeo. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Barro, R. W., and J.-W. Lee. 1993. “International Comparisons of Educational Attainment.” Journal of Monetary Economics 32 (3): 363–394.

________. 2001. “International Data on Educational Attainment: Updates and Implications.” Oxford Economic Papers 53 (3): 541–563.

Botero, J. C., S. Djankov, R. La Porta, F. Lopez-de-Silanes, and A. Shleifer. 2004. “The Regulation of Labor.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (4): 1339–1382.

Cho, Y. 2011. “Informality and Protection from Health Shocks: Lessons from Yemen.” Unpublished manuscript. Washington, DC: World Bank.

De Soto, H. 1989. The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World. New York: HarperCollins.

Djankov, S., and R. Ramalho. 2009. “Employment Laws in Developing Countries.” Journal of Comparative Economics 37 (1): 3–13.

EC, IMF, OECD, UN, and World Bank. 2008. System of National Accounts 2008. European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations, and World Bank, New York.

Fields, G. 1990. “Labour Market Modeling and the Urban Informal Sector: Theory and Evidence.” In The Informal Sector Revisited, ed. David Turnham, Bernard Salomé, and Antoine Schwarz, 49–69. Paris: OECD.

Friedman, E., S. Johnson, D. Kaufmann, and P. Zoido-Lobaton. 2000. “Dodging the Grabbing Hand: The Determinants of Unofficial Activity in 69 Countries.” Journal of Public Economics 76 (3): 459–493.

Galal, A. 2005. “The Economics of Formalization: Potential Winners and Losers from Formalization in Egypt.” In Investment Climate, Growth, and Poverty, ed. Gudrun Kochendorfer-Lucius and Boris Pleskovic. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Gasparini, L., and L. Tornarolli. 2006. “Labor Informality in Latin America and Caribbean: Patterns and Trends from Household Survey and Micro-data.” Mimeo. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Grubb, D., and W. Wells. 1993. “Employment Regulation and Patterns of Work in EC Countries.” Economic Studies 21. Paris: OECD.

Gwartney, J. D., and R. Lawson, with S. Norton. 2008. Economic Freedom of the World: 2008 Annual Report. Vancouver: Economic Freedom Network.

Hart, K. 1973. “Informal Income Opportunities and Urban Employment in Ghana.” Journal of Modern African Studies 11 (1): 61–89.

ILO (International Labour Organization). 1993. “Resolutions Concerning International Classification of Status in Employment.” Adopted by the 15th International Conference of Labour Statisticians. Geneva: ILO.

________. 2002. “Decent Work and the Informal Economy: Sixth Item on the Agenda.” 90th International Labour Conference: 2002. Report VII (2A). Geneva: ILO. http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc90/pdf/rep-vi.pdf.

________. 2004. Global Employment Trends for Youth. Geneva: ILO.

Johnson, S., D. Kaufmann, A. Shleifer, M. I. Goldman, and M. L. Weitzman. 1997. “The Unofficial Economy in Transition.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 159–239.

Kaufmann, D., and A. Kaliberda. 1996. “Integrating the Unofficial Economy into the Dynamics of Post Socialist Economies: A Framework of Analyses and Evidence.” Policy Research Working Paper 1691. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Loayza, N., A. M. Oviedo, and L. Serven. 2005. “The Impact of Regulation on Growth and Informality Cross-Country Evidence.” Policy Research Working Paper 3623. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Loayza, N., and J. Rigolini. 2006. “Informality Trends and Cycles.” Policy Research Working Paper 4078. Washington, DC: World Bank.

________. 2009. “Informal Employment: Safety Net or Growth Engine?” Mimeo. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Loayza, N., and T. Wada. 2010. “Informal Labor in the Middle East and North Africa: Basic Measures and Determinants.” Mimeo. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Pallares-Miralles, M., C. Romero, and E. Whitehouse. 2012. “International Patterns of Pension Provision II: A Worldwide Overview of Facts and Figures.” Social Protection and Labor Discussion Paper 1211. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Perry, G., W. Maloney, O. Arias, P. Fajnzylber, A. Mason, and J. Saavedra-Chanduvi. 2007. Informality: Exit and Exclusion. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Schneider, F. 2004. “The Size of the Shadow Economies of 145 Countries All over the World: First Results over the Period 1999 to 2003.” DP 1431. Bonn: IZA.

Schneider, F., A. Buehn, and C. E. Montenegro. 2010. “Shadow Economies All over the World : New Estimates for 162 Countries from 1999 to 2007.” Policy Research Working Paper Series 5356. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Schneider, F., and D. Enste. 2000. “Shadow Economies: Size, Causes, and Consequences.” Journal of Economic Literature 38 (1): 77–114.

Tanzi, V. 1980. “The Underground Economy in the United States: Estimates and Implications.” Banca Nazionale des Lavoro 135:4.

________. 1983. “The Underground Economy in the United States: Annual Estimates, 1930–1980.” IMF Staff Papers 30:2.

World Bank. 2009. “Turkey Country Economic Memorandum: Informality: Causes, Consequences, Policies.” Report 48523-TR. Washington, DC: World Bank.

________. 2013. Jobs for Shared Prosperity: Time for Action in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.