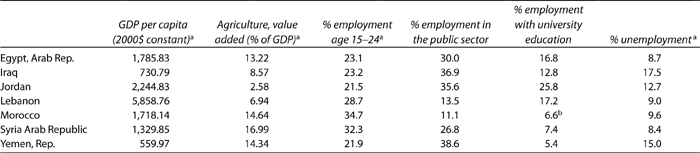

Table 2.1 Economic and Demographic Factors for Selected Non-GCC Countries

Source: Household surveys for available years.

a. World Development Indicators (WDI) dataset, last available year 1999–2008.

SUMMARY: This chapter assesses the main micro-determinants of informal employment in MENA. Analysis in the chapter quantifies the patterns of labor informality (defined as the share of all employment with no access to social security) according to age, gender, educational level, employment sector, profession, marital status, employment status, and geographic area in a selected group of non-GCC MENA countries. Countries in the MENA region are quite heterogeneous in terms of size, economic development, and demographic structure. Results indicate that the sizes of the public and agricultural sectors are perhaps the main correlates of informality in the MENA region. Countries where agricultural employment still constitutes a large share of overall employment (such as Morocco and the Republic of Yemen) display higher levels of overall informality. On the other hand, informality is lower in countries with larger public sectors and more urbanization, such as Egypt and Lebanon. The existence of a large public sector, which is still associated with generous benefits and better employment quality, creates an important segmentation between public and private employment in many MENA countries. Age, education, and firm size also represent important determinants of informality. Informality rates are generally highest among youth between ages 15 and 24, a group that accounts for 24 to 35 percent of total employment in most MENA countries, and among workers in small firms, whereas informality is generally lower among workers who have attained a university education and who work in the public administration.

Chapter 2 aims to understand the key micro-determinants of informal employment in MENA. The behavior of informal employment in MENA differs widely between GCC countries and non-GCC countries. Informal employment in GCC countries, as proxied by the share of the labor force not contributing to social security, is rather low (at 6.4 percent) and prevalent mainly among the self-employed. In non-GCC countries, using the same proxy, the share of the labor force not contributing to social security is high (at 67.2 percent) and prevalent mainly among wage earners (Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011). The main purpose of the chapter is to quantify the patterns of informal employment according to age, gender, educational level, employment sector, profession, marital status, employment status, and strata (that is, urban or rural). Based on availability of micro-data and given the general focus of the report on addressing informality from a human development standpoint, analysis in this chapter is limited to a selected group of non-GCC countries for which the relevant data are available: Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Syria, and the Republic of Yemen. This chapter consists of three main sections. The first section provides a brief macroeconomic background for these selected countries, focusing on patterns of economic and employment growth. The second section presents the profile of informality, composed of a set of statistics describing the share of workers in the informal sector according to various socioeconomic characteristics. The third section presents the main determinants (or correlates) of informality through regression analysis.

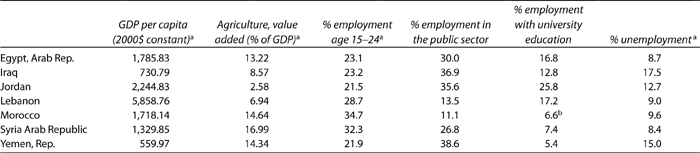

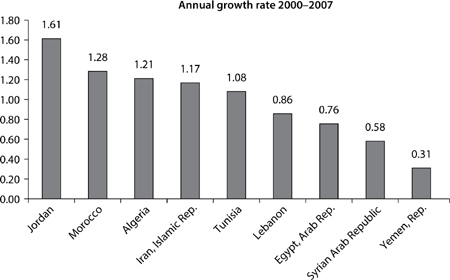

Countries in the region are quite heterogeneous in terms of size, economic development, demographic structure, and employment composition. Each of the countries included in the analysis has important economic and demographic factors that are likely to affect the level and characteristics of informal employment, such as the size of the agricultural sector compared with the secondary and tertiary sectors (higher levels of agricultural employment are associated with higher labor informality), size of the public sector (a larger public sector is associated with lower levels of labor informality), educational level of the labor force (a better educated labor force is associated with lower levels of labor informality), and age composition of the labor force (countries with younger populations are associated with higher levels of labor informality), among others (table 2.1 and figure 2.1). Important variations are found: Some of the countries are still very rural, and agricultural employment constitutes almost half of overall employment (such as the Republic of Yemen and Morocco); others have better educated workers (such as Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon); and in some countries, the public sector still accounts for a significant share of overall employment (such as Jordan, Egypt, the Republic of Yemen, Iraq, and Syria).

Table 2.1 Economic and Demographic Factors for Selected Non-GCC Countries

Source: Household surveys for available years.

a. World Development Indicators (WDI) dataset, last available year 1999–2008.

Figure 2.1 Employment Composition by Sector (Using Latest Available Year)

Source: World Development Indicators (all available non-Gulf Cooperation Council economies).

Note: Latest year available in the period 2003–2007.

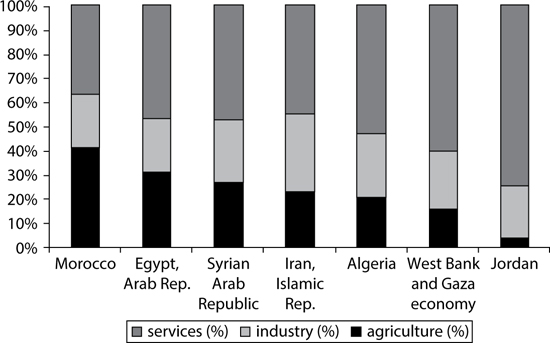

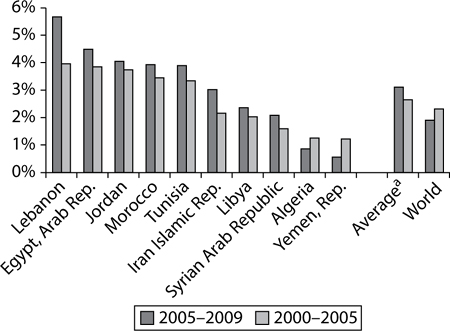

Countries in the region have displayed favorable economic growth in recent years. Some basic macroeconomic trends for the countries included in the analysis are presented to provide context to the analysis that follows. As discussed in chapter 1, the level of economic development and other macroeconomic variables, such as recent economic growth and employment composition, are likely to be important factors to understand a country’s profile and determinants of informality. This is particularly relevant in MENA, given the social, economic, and cultural heterogeneity of countries in the region. Figure 2.2 illustrates the average yearly economic growth rate of GDP per capita in a selected group of non-GCC countries for the periods 2000 to 2005 and 2005 to 2009. The region’s economic performance was above the world’s average in both time periods. Between 2005 and 2009, annual per capita growth rates showed important variation across countries, with some displaying rapid growth (such as Lebanon, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia), others moderate growth (such as the Islamic Republic of Iran, Libya, and Syria), and some poor growth (such as the Republic of Yemen and Algeria). Some countries performed much better between 2005 and 2009 compared with 2000 to 2005 (mainly Lebanon and the Islamic Republic of Iran), whereas in others, the opposite occurred (such as Algeria and the Republic of Yemen).

Figure 2.2 Yearly GDP Per Capita Growth Rate

Source: World Development Indicators.

a. Unweighted average (selected countries).

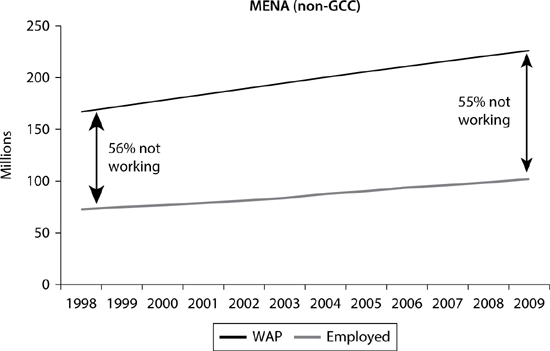

While employment growth in the region has been among the highest in the world in the past decade, the level of employment creation has been unable to keep up with population growth (see discussion in chapter 1 and figure 2.3). This demographic dynamic contributed to high unemployment rates, especially among youth, and a difficult school-to-work transition.

Figure 2.3 Growth in Employed and Working-Age Population in Non-GCC MENA Countries, 1998–2009

Source: World Bank, based on the ILO’s EAPEP (Economically Active Population, Estimates and Projections) database.

Note: GCC - Gulf Cooperation; MENA - Middle East and North Africa.

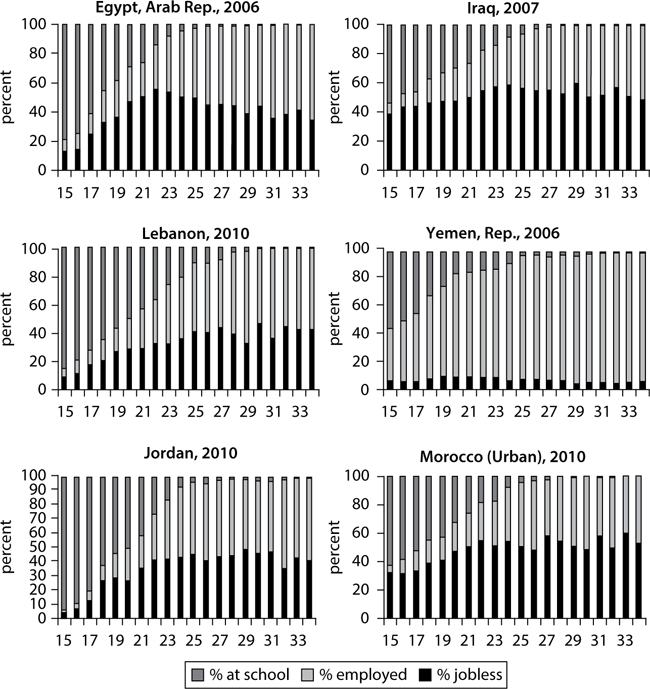

Joblessness in many MENA countries remains notable, especially among women. School-to-work transition patterns highlight the incidence of joblessness and the disadvantaged position of women in MENA. Figure 2.4 illustrates the patterns of school-to-work transition in selected countries. This transition is measured by the length of time between when 50 percent of the population is enrolled in school and when 50 percent is employed. It takes as little as one year in the Republic of Yemen to up to approximately 18 years in Iraq. In developed countries, a comparable process takes on average 1.4 years (Angel-Urdinola and Semlali 2010). Large differences exist in school-to-work transition -patterns by gender. Upon exiting the school system, the majority of women in the countries considered (except for the Republic of Yemen) enter into joblessness (that is, unemployment and/or inactivity), and only a small proportion successfully move into employment. According to the definition used, the school-to-work transition never fully occurs for women in most of the countries. This has important implications for the region’s economic growth potential. First, international experience indicates that greater economic equality between women and men is associated with poverty reduction, higher GDP, and better governance (Klasen 1999). Recent studies indicate that many economies in MENA display lower participation rates than those predicted given their age and education structures. If female labor force participation in these countries rose to the level predicted by women’s age and education structure, household earnings could increase substantially (World Bank 2003).

Figure 2.4 School-to-Work Transition (for Ages 15–35) in MENA

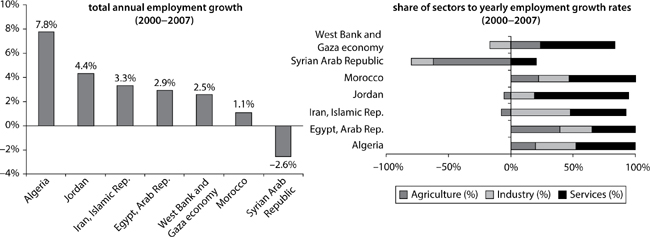

The service sector has been an important source of employment growth in recent years, with crucial implications for informality. A closer look at available data on employment growth by country between 2000 and 2007 reveals several interesting patterns. Data indicate important variation in annual employment growth across countries in the region, from an increase of almost 8 percent per year in Algeria to a decrease of almost 3 percent per year in Syria (left-hand panel of figure 2.5). As illustrated by the right-hand panel of figure 2.5, in many countries, the service sector (mainly commerce and construction) has been an important engine of employment growth, generally followed by the industrial sector. The contribution of agriculture to total employment growth has been important in some economies such as Egypt and the West Bank and Gaza economy, but it has also contributed to negative growth in employment (that is, to employment destruction) in countries such as Syria, Jordan, and the Islamic Republic of Iran. In Syria, for instance, the negative growth in employment between 2000 and 2007 is largely explained by a rapid decrease in agricultural employment.

Figure 2.5 Employment Growth between 2000 and 2007 for Selected Countries

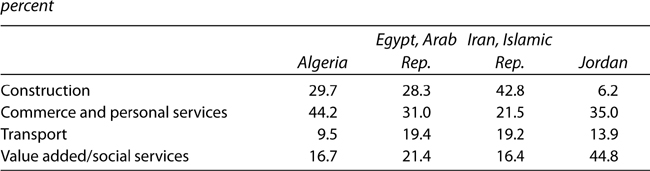

The expansion of the service sector (mainly construction and commerce) has gone hand in hand with an increase in informality and self-employment in the region. The expansion of employment in the service sector has been an important feature of many economies in MENA in recent years. As presented in table 2.2, the construction and commerce sectors account together for 40 to 70 percent of all employment growth in the service sectors recently. In Morocco, employment growth was 5.1 percent in transport and 3.7 percent in construction for the period 1998 to 2003 (World Bank 2009). These results are likely to have key implications for informality trends because construction and commerce are sectors often associated with high rates of informal employment. Indeed, as illustrated in figure 2.6, informality (as proxied by the Schneider Index and by the share of self-employment of total employment) has increased in recent years, at a time when employment in the construction and commerce sectors has been expanding.

Table 2.2 Composition of Employment Growth in the Services Sector for Selected Countries, 2000–2007

Source: World Development Indicators and ILO’s KILM dataset.

Figure 2.6 Annual Growth of Informality for Selected Economies

Source: World Development Indicators and ILO’s KILM dataset.

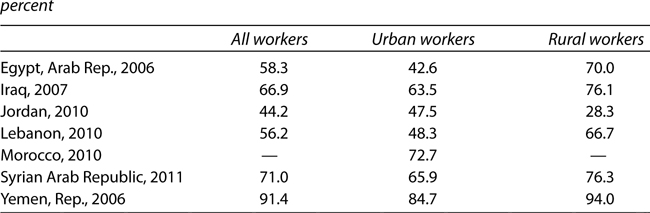

This section presents the profile of informality for the countries included in the analysis.1 The profile consists of a set of statistics describing workers in the informal sector according to various characteristics, such as socioeconomic status, educational level, age, gender, strata (urban or rural), marital status, and occupation, among others. The informality profile is presented for all workers in the sample (including the public sector), and separately for private sector workers. The analysis includes urban and rural workers. Many informality studies (Perry and others 2007) exclude rural employment from the analysis because in other regions it is predominantly informal. In MENA countries, this is not necessarily the case because of an important public sector presence (and, thus, formal employment) in rural areas. Although rural employment remains more informal than urban employment (except in Jordan), informality rates in both rural and urban areas are more comparable than in other regions of the world (table 2.3).

Table 2.3 Informality Rates for Selected Countries

Source: Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011.

Note: — = Data not reliable.

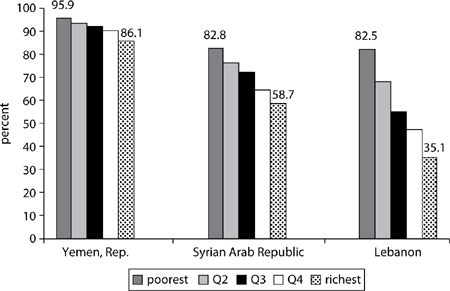

Informality is a more persistent phenomenon among the poor. As expected, informality generally decreases as wealth increases. Nevertheless, in some MENA countries, informality remains significant even among the wealthier segments of the population. In the Republic of Yemen for instance, more than two-thirds of all workers who belong to the richest households work in the informal sector. Yet, in other countries such as Lebanon, informality rates are significantly lower for the wealthiest segments of the population (figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7 Informality Rates by Quintile of Per Capita Consumption for Selected Countries

Source: Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011.

Note: Q = quintile.

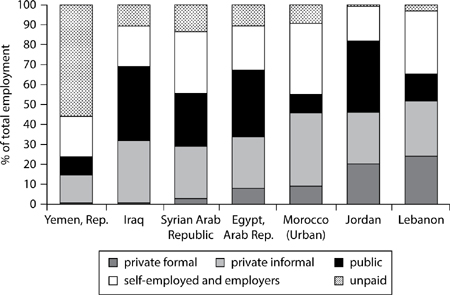

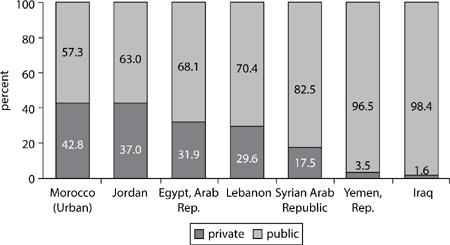

In most countries in the region, the vast majority of formal workers are employed in the public sector. Labor markets in many MENA countries are still influenced by the legacy of a large public sector, which accounts for about 29 percent of overall employment in the Arab world (Elbadawi and Loayza 2008), and civil service in many MENA countries is larger than in other countries with similar levels of income and economic structure. Historically, in countries such as Egypt, the growth in the civil service was the result of a social contract in the 1970s and 1980s whereby the government effectively offered employment guarantees to university graduates and to graduates of vocational secondary schools and training institutes. Despite the fact that employment growth in the public sector has slowed dramatically in recent years, public sector employment (government and public enterprises) in most countries still accounts for more than 60 percent of all formal sector employment in MENA (figure 2.8). In some countries, such as the Republic of Yemen and Iraq, formal employment is almost entirely associated with public employment. The public sector remains the main engine of formal employment: In Egypt about 45 percent of all new formal jobs (about 260,000) created in the economy between 1998 and 2006 were in the public sector (Angel-Urdinola and Semlali 2010).

Figure 2.8 Size of Private Salaried Formal Sector versus Other Sectors

Given the weight of the public sector in overall formal employment (figure 2.9), changes in the size of the public sector are likely to affect overall informality trends, especially given that formal private employment growth remains limited. In particular, the creation of formal private sector jobs has not been sufficient to offset the downsizing of the public sector in many countries (Radwan 2007). Radwan argues that formal businesses in many MENA countries face important challenges that restrain their capacity to grow, such as dealing with complex bureaucratic procedures; access to poor infrastructure, credit, and technologies; and high labor taxes. A recent assessment of the private sector in Morocco reveals that excessive regulation of the labor market has pushed much of the economic activity into the informal sector (World Bank 1999). At the same time, the private sector in many MENA countries is primarily composed of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which represent about 95 percent of all registered enterprises. The great majority of SMEs in MENA have fewer than five workers and are characterized by high levels of informality; low participation of women; concentration in low-growth sectors; low use of modern technologies; and a low level of product quality, competitiveness, diversification, and innovation. Overall, a large public sector and restrictive regulations contribute to squeeze the formal private sector and limit its dynamics (see chapter 5, part 1).

Figure 2.9 Distribution of Formal Employment for Selected MENA Countries

The private formal sector in the region is still nascent. Employment in the formal private sector is almost nonexistent in the Republic of Yemen and Iraq, and below 10 percent of total employment in Syria, Egypt, and Morocco, although it is somewhat larger in Jordan and Lebanon. As seen earlier, this reflects a number of factors, including the country’s production structure, the large size of the public sector, which effectively competes for resources and talent with the private formal sector, and the design of pension systems (which in the Republic of Yemen and Iraq do not extend in reality to the private sector). To the extent that formality also reflects higher productivity, more productive workers and especially firms bear the brunt of taxation. This small private formal sector coexists with a large informal sector that includes both low-productivity firms and workers, but also larger firms that have secured favorable application of regulations through rent seeking. Especially if compared with the latter, one might argue that the small formal private sector bears disproportionately the taxation burden.

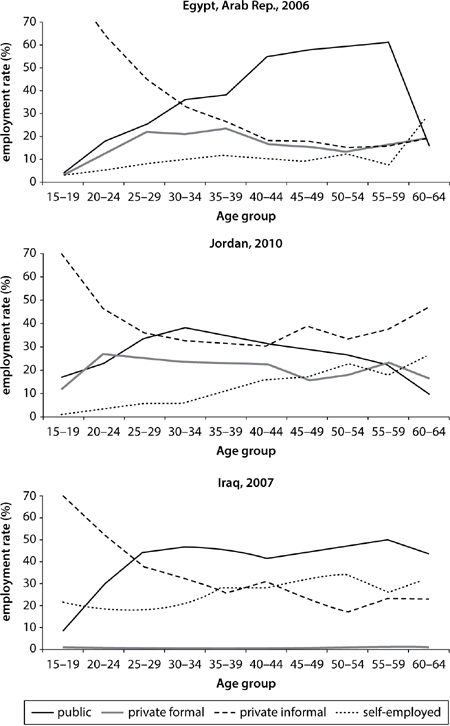

An important transition is made from informal employment into public sector employment as young people reach prime age adulthood. Figure 2.10 illustrates employment patterns by age for urban workers in a selected group of countries. Informality rates are very high among youth between ages 15 and 24. After age 24, informality decreases rapidly until individuals reach prime working age (40 to 45 years). After age 40, informality rates are lower (20 to 30 percent). This rapid decrease in informality rates goes hand in hand with a rapid increase in public employment, which suggests that informal workers enter into public sector jobs as they move from youth into adulthood. Not surprisingly, many individuals in the region queue in the informal sector until they find a job in the public administration. Still, one has to be cautious in interpreting these results as they are likely to reflect vintage effects since, especially in countries like Egypt, more public sector jobs were available to earlier cohorts of workers. These trends are very different from those observed in Latin America. In Mexico, for instance, although informality rates also decrease by age, the observed transition occurs not between informality and public employment, but between informality and self-employment (Perry and others 2007).

Figure 2.10 Employment Status by Age for Selected Countries, Urban Areas Only

Self-employment is low among youth and young adults but increases rapidly after individuals reach age 50, suggesting a transition from public employment into self-employment as individuals retire from the public administration. As illustrated by figure 2.10, the share of individuals who work in the formal private sector remains almost nonexistent in countries such as the Republic of Yemen and Iraq (at all age groups), which suggests a very limited formal private sector. Even in more dynamic and diversified economies, such as Egypt, Jordan, and Morocco, formal private sector employment accounts for a maximum of 25 percent of overall employment at all age groups. Finally, interesting patterns are seen in the trend in self-employment by age. Although overall rates of self-employment remain low, especially among youth, the share of self-employment to overall employment increases steadily as people reach retirement age, suggesting that workers (especially those who decide to retire early) transition from public employment into self-employment.

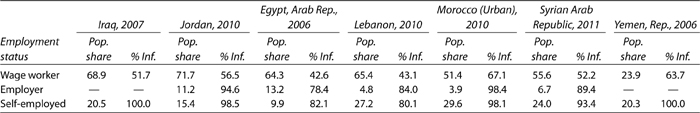

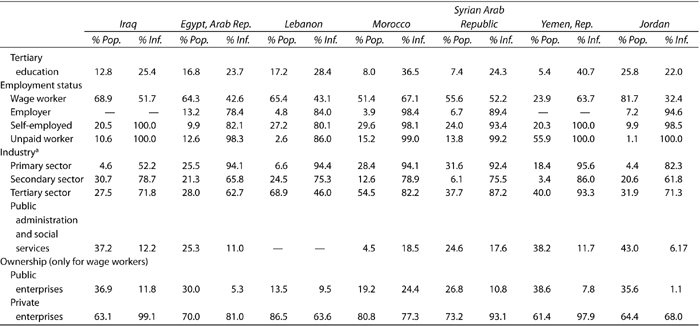

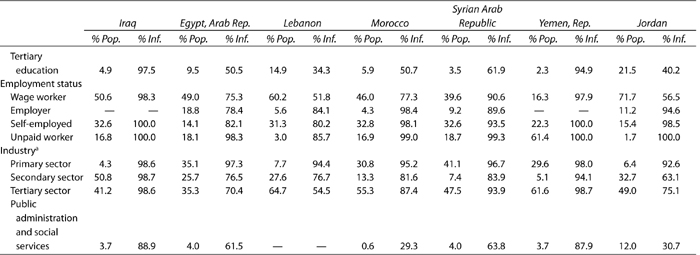

Informality rates are generally higher for wage earners outside the public administration and the self-employed. Results indicate that informality rates among wage earners (who account for 50 percent of overall employment for most countries in the analysis) range between 40 and 60 percent. Informality rates among the self-employed (who account for 15 to 36 percent of all employment for most countries in the analysis) are even higher, from 80 percent in Lebanon to almost 100 percent in Iraq and the Republic of Yemen (table 2.4). The promotion of self-employment/micro-entrepreneurship continues to be a core strategy to boost employment, and so creation of new, flexible, and innovative mechanisms to ensure pension and social security coverage for the self-employed should be developed and implemented (see chapter 5).

Table 2.4 Informality Rates by Employment Status

Source: Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011.

Note: Inf. = informality; Pop. = population; — = not available.

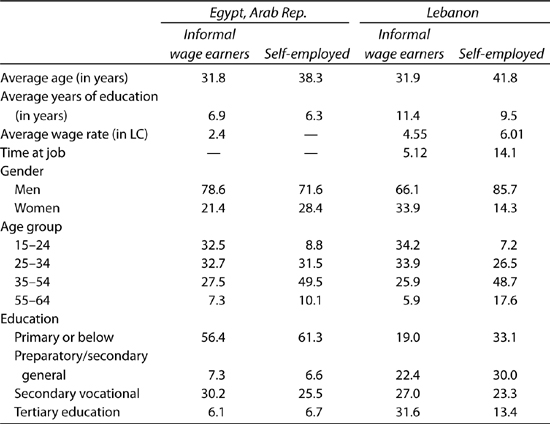

Self-employed individuals have somewhat different profiles than informal wage earners. As mentioned earlier, self-employed workers in MENA are generally informal because they rarely participate in social security contributing schemes. Nevertheless, this group of workers displays somewhat different characteristics as compared with other informal workers (mainly wage earners). Table 2.5 presents a set of descriptive statistics for Lebanon and Egypt highlighting important differences in the characteristics of workers in these two groups:

• Self-employed are generally older and less educated. Results in table 2.5 indicate that in Egypt and Lebanon, self-employed workers are older than informal wage earners (6 years older in Egypt and about 10 years older in Lebanon, on average). In both countries, the majority of self-employed (almost half) is between 35 and 54 years of age. The share of youth (15–24) who work as self-employed is very low (9 percent in Egypt and 7 percent in Lebanon). Self-employed workers are less educated than informal wage earners. On average, self-employed workers in Egypt (Lebanon) have attained one (two) years of education fewer than informal wage earners. In Lebanon, only 13.4 percent of all self-employed have attained tertiary education compared with 31.6 percent among wage earners.

• In Lebanon, self-employed workers have more stable jobs and earn relatively higher wages. Despite being less educated, self-employed workers in Lebanon (which account for about 33 percent of all employment) earn on average wages that are 30 percent higher than those among informal wage earners, which could reflect experience. Also, self-employed workers claim to have worked in the same job for 14 years (on average) as compared with 5 years among informal wage earners.

Table 2.5 Self-Employed versus Informal Wage Earners (Basic Characteristics)

Note: LC = local currency; — = not available.

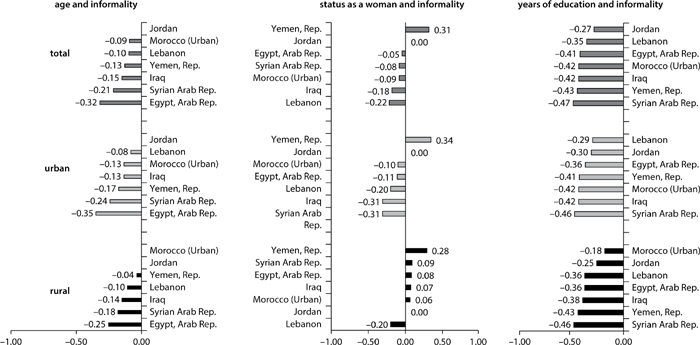

Age, gender, and education also constitute important correlates of informality. Figure 2.11 presents a basic set of correlations between informal employment and individual characteristics such as age, gender, and years of education. Not surprisingly, results indicate that age and education are negatively correlated with informality (that is, higher age and more education are associated with less informality). The size of the correlation between years of education and informality is large for all countries (from −0.35 in Lebanon to −0.47 in Syria), suggesting an important negative relationship between education and informal employment. Nevertheless, the magnitude of the correlation between age and informality varies across countries and strata. For instance, the negative association between age and informality seems to be larger in Egypt, Syria, and Iraq than in Morocco, the Republic of Yemen, and Lebanon, and generally stronger in urban than in rural areas (figure 2.11 shows results only for urban areas).

Figure 2.11 Basic Correlations by Strata (Informality and Individual’s Characteristics)

Source: Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011.

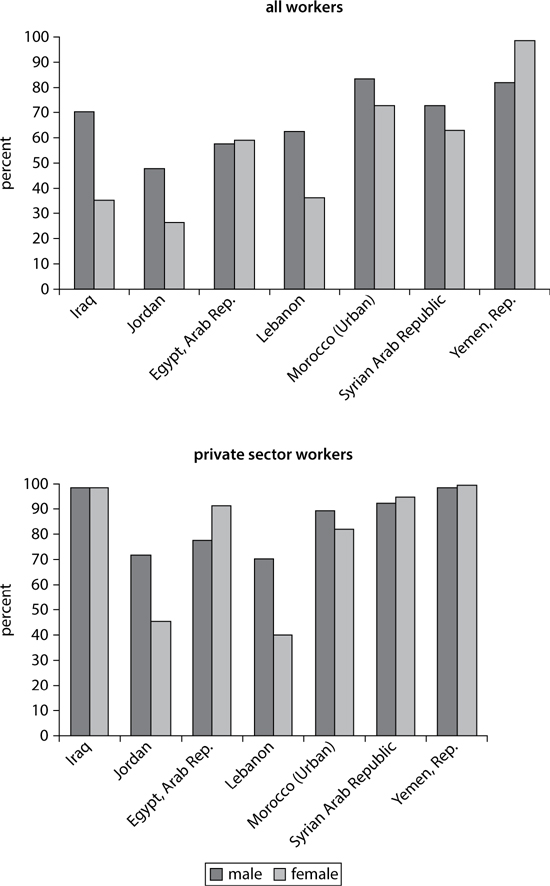

Being a woman is associated with higher informality rates in some countries and with lower informality rates in others, mainly depending on the overall structure the country’s employment (figure 2.11). In countries where agricultural employment constitutes an important share of overall employment, such as Egypt and the Republic of Yemen, being a woman is associated with higher levels of informality because women are often employed in unpaid/subsistence agriculture. In countries where public employment represents a significant share of overall employment, such as Iraq, and Syria, being a woman is associated with lower levels of informality. Given low overall levels of female labor force participation in these countries, women who participate in the labor force (generally those with higher levels of education) self-select into public sector jobs. Hence, as illustrated in figure 2.12, informality rates are higher among men than among women in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Morocco, and Jordan, and higher among women than among men in the Republic of Yemen. However, once the sample is restricted to private sector workers, informality rates between men and women are equally high in most countries.

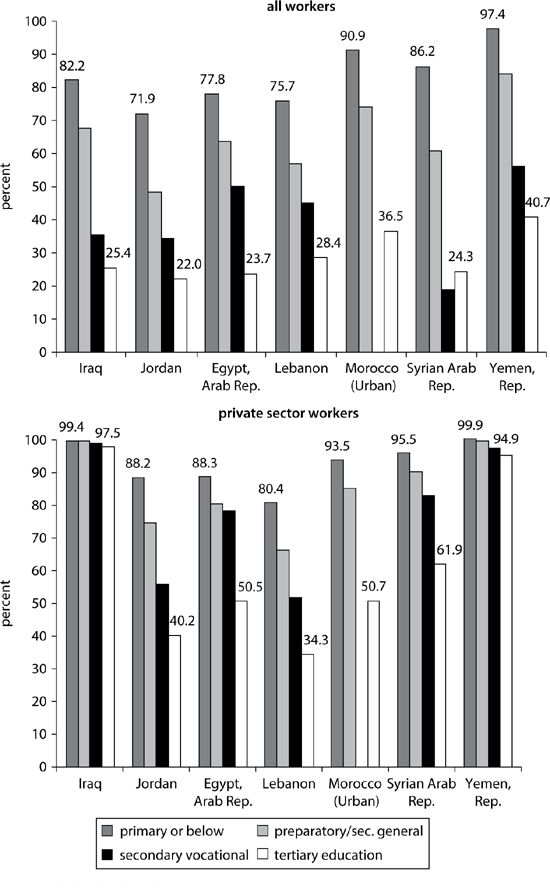

Figure 2.12 Informality Rates by Gender

Over workers’ life cycles, an increase in employment in the public sector mirrors the decline in informal salaried employment. A closer look at informality rates by age group and educational attainment indicates important differences for workers in the private sector. Informality rates are generally highest among young people between the ages of 15 and 24, a group that in most countries in the sample accounts for 24 to 35 percent of total employment. Above age 25, informality rates decrease rapidly up to age 54 in most countries. Informality rates increase again for workers between ages 55 and 64 (which make up 5 to 8 percent of total employment in most countries) as some workers find employment in the informal sector after they retire from their formal jobs. Informality rates among workers who attained primary and/or basic education (who account for at least 50 percent of overall employment in most countries in the region) are generally much higher than among workers who attained secondary vocational and/or tertiary education. Differences in informality rates by age and education are less pronounced for workers in the private sector. Indeed, in some countries such as the Republic of Yemen and Morocco, differences in informality rates by age and educational attainment for workers in the private sector are negligible (figures 2.13 and 2.14).

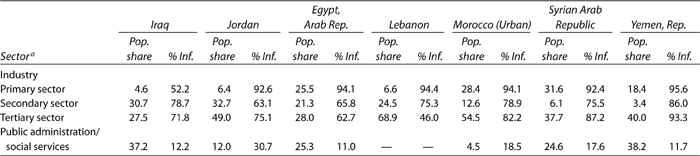

Informality is generally higher in the primary sector, with important implications for countries with a large agriculture sector. Results suggest that the great majority of workers in agriculture and mining activities (which account for as little as 5 percent of employment in Iraq and as much as 30 percent in Morocco) work in the informal sector (table 2.6). In the tertiary sectors (that is, services), informality rates vary among countries, ranging from 46 percent in Lebanon to 93 percent in the Republic of Yemen. Among workers employed in the public administration/social services (which in countries such as Egypt, Iraq, and Syria account for as much as one-third of total employment), informality rates are below 20 percent. This is probably explained by the existence (in some countries) of fixed-term contracts in the public sector.

Table 2.6 Informality Rates by Sector of Employment

Source: Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011.

Note: Inf. = informality; Pop. = population; — = not available.

a. Primary sector (agriculture); secondary sector (manufacturing and construction); tertiary sector (wholesale, transport, services), public administration, and social services (including education and health).

Although a profile of informality is informative, the main drawback is that it cannot be used to disentangle its determinants. For example, the fact that a group of workers (such as agricultural workers) displays high rates of informality may be due in large part to other characteristics of the group (such as the educational level of the group’s members). To provide more insights about the determinants or correlates of informality, this section assesses informality through regression analysis using a simple probit regression model. The dependent variable of the regression model is a binary variable that takes a value of one if the worker is employed in the informal sector (that is, if the worker does not contribute to social security) and zero otherwise. Separate regressions are provided for the full sample and for workers in the nonagricultural sector.2 The main independent variables used include (1) strata (an urban dummy), (2) demographic characteristics of the worker (a male dummy, a married dummy, and the worker’s age group), (3) the highest educational level attained by the worker, (4) employment status and sector of the worker, and (5) ownership of the firm where the worker is employed (using a dummy for publicly owned firms). As these are cross-sectional regressions, results should not be interpreted causally.

Figure 2.14 Informality Rates by Highest Educational Level Completed

The main results are summarized as follows:

• Strata: In many countries, especially in Latin America (Perry and others 2007), rural employment is mainly associated with agricultural activities and mainly informal. In MENA countries, this is not necessarily the case, because of an important public sector presence (and, thus, of formal employment) in rural areas. Controlling for other factors, urban workers are only 3 to 12 percent less likely to be employed informally than otherwise similar workers in rural areas in Egypt and Lebanon. Although rural employment remains more informal than urban employment, informality rates in both rural and urban areas are comparable. Indeed, in some countries such as Iraq, Morocco, and the Republic of Yemen, the difference in the probability of workers’ formality between urban and rural areas is small and/or not statistically significant (table 2.7).

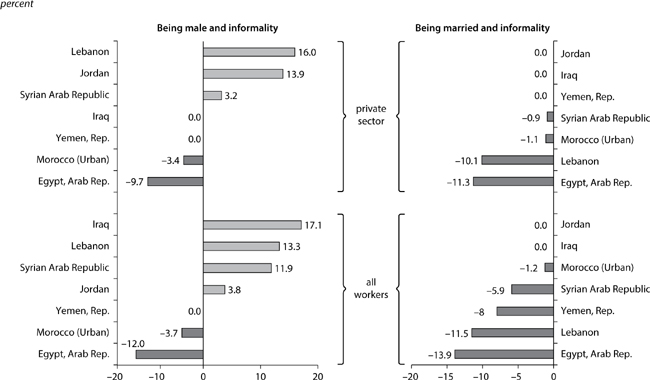

• Gender: The effect of being male on the probability of working in a formal job varies across countries (figure 2.15 and table 2.7). In Egypt and Morocco, controlling for other factors, being a male worker is associated with a 4 to 12 percent lower probability of being employed informally, as is generally the case in many developing countries (see Perry and others 2007 for estimates from Latin America). On the other hand, in Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria, being male is actually associated with a 6 to 17 percent higher probability of working in the informal sector. This result is probably due to female workers (generally educated ones) participating in the labor force who tend to queue for formal jobs in the public sector (Angel-Urdinola and Semlali 2010). In the Republic of Yemen, gender does not seem to be an important determinant of informality.

• Marital status: In the MENA region, important associations are found between marriage and labor outcomes. Recent literature shows that having good and stable employment is an important social requirement for individuals, especially young men, to get married. For instance, Assaad, Binzel, and Gadallah (2010) use Egypt’s Labor Market Panel Survey of 2006 (ELMPS 06) to study the role of employment (that is, having a good, fair, or poor job) on the timing of marriage. The authors find that having a better job leads men to a faster transition into marriage. These results are consistent with the findings herein, as being married, controlling for other factors, is associated with a 10 to 14 percent lower probability of working in the informal sector in Egypt and Lebanon, and a 2 to 8 percent lower probability in Morocco, the Republic of Yemen, and Syria (figure 2.15 and table 2.7). In Jordan, marital status is not significantly associated with informal employment.

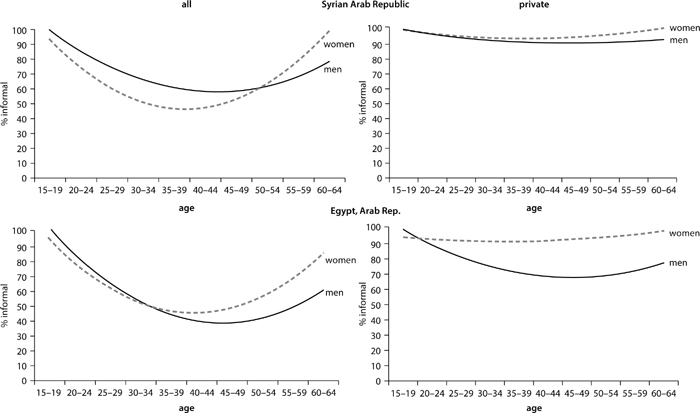

• Age: Controlling for other factors, younger workers are more likely to work in the informal sector (table 2.7). Results from Egypt, the Republic of Yemen, and Syria indicate that adults aged 35 and older are 13 to 34 percent less likely to work in the informal sector than youth aged 15 to 24. In Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, and Morocco, the association between age and informality is less strong, because adults 25 and older are only 2 to 8 percent less likely to work in the informal sector than youth aged 15 to 24. It is worth noting that acquiring informal jobs is a way for young individuals to enter the labor market, gain experience, and eventually move into formal employment, as informality decreases quickly with age. The effect of age on informality is generally lower in magnitude for private sector workers. This is expected since the private sector in MENA remains largely informal. To better illustrate this phenomenon, figure 2.16 shows informality rates by age for men and women for Syria and Egypt. Results in the left-hand panel show that informality rates decrease rapidly as age increases up to ages 40 to 45 and increases again thereafter as individuals retire. Results also indicate that early retirement is quite common, especially among women. In the private sector (shown in the right-hand panel of figure 2.16), informality rates by age are rather flat and high, especially for women, suggesting that the negative slope between age and informality is driven by workers entering public sector employment as they reach prime working age.

• Highest educational level attained: Controlling for other factors, more education is associated with a lower probability of being employed in the informal sector. The negative relationship between attaining higher education and having a lower probability of being employed informally is much lower for private sector workers (confirming the results presented in the profile of informality). Controlling for other characteristics, attaining middle school (high school) is associated with a 5 to 18 (12 to 37) percent lower probability of working in the informal sector compared with otherwise similar workers who attained at most primary school. Attaining tertiary education is associated with up to a 47 percent lower probability of being employed informally compared with otherwise similar workers who attained at most primary school. In some countries (for example, Iraq, Syria, and the Republic of Yemen), having completed high school decreases the probability of workers being employed informally as much as (or even more than) having attained tertiary education. Generally, one would expect the opposite result (as in Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon), namely, a lower probability of being employed informally for workers with tertiary education. Finally, to control for heterogeneity in skills beyond educational attainment, quintile dummies (omitting the lowest quintile) representing the results of a cognitive nonverbal test (measuring workers’ logical and analytical skills) in Lebanon and Syria are included. Interestingly, this factor was not a significant determinant of informality (results are available upon request).3

• Sector of employment: Controlling for other factors, the association between informality and sector of employment varies across countries. In countries where the tertiary sector is more developed toward high value-added services such as financial services, transport, tourism, and communications (such as in Egypt and Lebanon), workers in the tertiary sector are associated with a 4 to 13 percent lower probability of working informally compared with workers in the secondary sector (manufacturing and construction). On the other hand, in countries where the tertiary sector is mainly geared toward low value-added personal services and wholesale or retail (such as in the Republic of Yemen and Syria) workers in the tertiary sector are associated with a 4 to 25 percent higher probability of working informally compared with workers in the secondary sector. Workers in public administration and social services are associated with 6 to 14 percent lower informality rates than otherwise similar workers in the secondary sector.

• Public sector employment: Controlling for other factors, this variable is perhaps the most important determinant of informality. In all countries where information about firm ownership is available, workers in the public sector are associated with a 30 to 85 percent higher probability of working formally compared with otherwise similar workers in the private sectors. Indeed, as illustrated in figure 2.9, the public sector hosts a significant share of all formal employment. As such, changes in the size of the public sector relative to the private sector will likely be important determinants of informality dynamics (box 2.2).

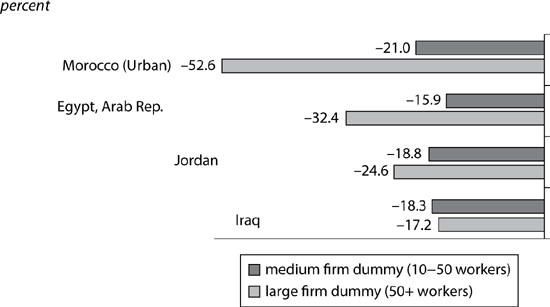

• Firm size: Data on firm size were only available for a few countries in the region (Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Morocco). For these countries, firm size dummy variables are included in the regression analysis (small-size firm dummy, fewer than 10 workers; medium-size firm dummy, 10 to 50 workers; and large-size firm dummy, more than 50 workers). Regression coefficients are shown in figure 2.17; the results indicate an important association between informality and firm size. Workers in medium-size (large-size) firms are 16 to 21 (17 to 53) percent less likely to work in the informal sector compared with workers in small-size firms.

Table 2.7 Marginal Increase in the Probability of Being “Informal” according to the Characteristics of the Worker (Nonagricultural Employment Only)

Source: Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011.

Note: All = all workers; Priv. = private sector workers. All coefficients are multiplied by 100. Coefficients that are not statistically significant are denoted by N.S. Underlined coefficients are significant at a 10 percent confidence level. Other coefficients are significant at a 5 percent confidence level. Omitted categories: Age group: 15–25; Education: primary education or below. Employment sector: secondary sector (manufacturing and construction); Ownership: private firms. — = not available.

a. Tertiary sector (wholesale, transport, services).

b. Public administration and social services (including education and health).

Figure 2.15 Marginal Increase in the Probability of Being “Informal” according to Gender and Marital Status

Source: Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011 (see table 2.7 for more details).

Figure 2.16 Informality Rates by Age Group (Syrian Arab Republic and the Arab Republic of Egypt)

Figure 2.17 Marginal Increase in the Probability of Being “Informal” according to Firm Size (Omitted Category, Small Firms, 2–9 Workers)

Source: Angel-Urdinola and Tanabe 2011.

Socioeconomic conditions in the region are quite heterogeneous, which has important implications for informality. Each country included in the analysis has important economic and demographic factors that are likely to affect the level and characteristics of informal employment, such as the size of the agricultural sector compared with the secondary and tertiary sectors (higher levels of agricultural employment are associated with higher labor informality), the size of the public sector (a larger public sector is associated with lower levels of informality), the educational level of the labor force (a more educated labor force is associated with lower levels of labor informality), and the age composition of the labor force (countries with younger populations are associated with higher levels of labor informality), among others. There are important variations across countries: Some of them are still very rural, and agricultural employment constitutes almost half of overall employment (the Republic of Yemen and Morocco); some countries have more educated workers (Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon); and in some, the public sector still represents a significant share of overall employment (Egypt, the Republic of Yemen, Iraq, Jordan, and Syria).

Several factors make informality in the MENA region a persistent phenomenon that may continue to rise in the years to come. The current demographic transition, the reduced importance of public employment, and the increase in private low-productivity employment are all likely to contribute to an increase in informality in the near future. Declining fertility and mortality rates, coupled with an increasing share of young people who attain tertiary education (notably women), are important factors contributing to the expansion of the informal sector. Informal employment is increasingly becoming (even for some educated individuals) a permanent state of employment associated with low pay, poor working conditions, and limited mobility to the formal sector. One of the main reasons for the increase of informal employment in MENA is the decline in public sector employment as a share of total employment. The creation of formal private sector jobs has not been sufficient to offset the downsizing of the public sector in many countries. Formal businesses in many MENA countries face important challenges that restrain their capacity to grow, such as dealing with complex bureaucratic procedures; access to poor infrastructure, credit, and technologies; and high labor taxes. Overall, the formal private sector is very small in most MENA countries, and some might argue that this sector might also unfairly bear the brunt of paying all taxes.

Informality is a more pronounced phenomenon among the poor. Informality rates among workers generally decrease as their household wealth increases. Nevertheless, in some countries informality remains significant even among the wealthier segments of the population. In the Republic of Yemen and Morocco, for instance, more than two-thirds of all workers who belong to the richest households work in the informal sector. This result has important implications. As indicated in chapter 1, informal employment in non-GCC countries, albeit large, produces little output relative to its employment share, suggesting very low levels of worker productivity. This generally occurs when informal workers are constrained in access to credit, services (such as utilities), and/or technology.

Contrary to other developing regions, patterns of urban and rural informality in MENA are somewhat similar, because of the presence of the public sector in rural areas. Urban workers are only 5 to 12 percent less likely to be employed in the informal sector than otherwise similar workers in rural areas. Controlling for age and education, in countries such as Iraq, Morocco, and the Republic of Yemen, the probability of being employed in the informal sector does not vary across urban and rural workers.

The size of the public sector and the size of the agricultural sector are perhaps the main determinants of informality in the MENA region. Countries in the MENA region are quite heterogeneous in terms of size, economic development, and demographic structure. Countries where agricultural employment still constitutes a large share of overall employment (such as Morocco and the Republic of Yemen) are associated with higher levels of overall informality. On the other hand, countries with larger public sectors and more urbanization such as Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon are associated with lower levels of overall informality. The existence of a large public sector, which is still associated with generous benefits and better employment quality, creates an important segmentation between public and private employment in many MENA countries. At the same time, the private sector in many MENA countries is primarily composed of small and medium enterprises, which account for about 95 percent of all registered enterprises. In all countries where information about firm ownership is available, workers in the public sector are associated with a 45 to 80 percent lower probability of working informally as compared with otherwise similar workers in the private sector. Self-employed and agricultural workers in most MENA countries are associated with a 10 to 20 percent higher likelihood of being employed informally compared with otherwise similar workers employed as wage earners.

Age, gender, firm size, and education also constitute important determinants of informality. Informality rates are generally highest among young people between ages 15 and 24, a group that in most countries in the sample accounts for 24 to 35 percent of total employment. Above age 25, informality rates decrease rapidly in most countries. Attaining secondary technical and tertiary education is associated with a 40 percent higher probability of being employed formally compared with otherwise similar workers who attained at most a primary education. The relationship between gender and informality varies across countries. In Egypt and Morocco, controlling for other factors, being a male worker is associated with a 4 to 12 percent lower probability of being employed informally, as women generally queue for formal sector jobs. On the other hand, in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon, being a male is actually associated with a higher probability of working in the informal sector as is generally the case in many developing countries. Finally, results indicate an important association between informality and firm size. Workers in medium and large firms are 16 to 53 percent less likely to work in the informal sector compared with workers in small firms.

Annex Table 2A.1 Description of the Data Used for the Micro-Analysis

Note: Inf. = informality; Pop. = population; — = not available.

a. Industry = primary sector (agriculture); secondary sector (manufacturing and construction); tertiary sector (wholesale, transport, services); public administration; and social services (including education and health).

Note: Inf. = informality; Pop. = population; — = not available.

a. Industry = primary sector (agriculture); secondary sector (manufacturing and construction); tertiary sector (wholesale, transport, services); public administration; and social services (including education and health).

1. Because of data restrictions, the analysis in the remainder of this chapter as well as in chapters 3 and 4 is restricted to non-GCC MENA countries. Tunisia is excluded from the analysis because of a different and not comparable -definition of informality. An overview of informality trends in Tunisia is given in box 2.1.

2. Results including agricultural employment are very similar to those presented in the chapter and are available upon request.

3. The cognitive test used “Raven’s Progressive Matrices,” a nonverbal test in which individuals have to identify the missing piece of a particular pattern among multiple choices. Respondents are given five minutes to answer as many of the 12 matrices that are included in the test as possible. The matrices become progressively more difficult and require greater cognitive capacity. This test is independent of language, reading, or writing skills and focuses on measuring observation skills, analytical ability, and intellectual capacity. A score (out of 12) for each respondent is calculated based on the number of correct answers completed in the allocated time frame. See chapter 4 for a detailed description.

Angel-Urdinola, D., S. Brodmann, and A. Hilger. 2011. “Labor Markets in Tunisia: Recent Trends.” Mimeo. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Angel-Urdinola, D., and A. Semlali. 2010. “Labor Markets and School-to-Work Transition in Egypt: Diagnostics, Constraints, and Policy Framework.” MPRA Paper 27674, University Library of Munich, Germany.

Angel-Urdinola, D., and K. Tanabe. 2011. “Micro-Determinants of Informal Employment in the Middle East and North Africa Region.” Mimeo. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Assaad, R. 2009. “Labor Supply, Employment and Unemployment in the Egyptian Economy, 1988–2006.” In The Egyptian Labor Market Revisited, ed. R. Assaad, 1–52. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Assaad, R., C. Binzel, and M. Gadallah. 2010. “Transitions to Employment and Marriage among Young Men in Egypt.” Middle East Development Journal 2 (1): 39–88.

Elbadawi, I., and N. Loayza. 2008. “Informality, Employment and Economic Development in the Arab World.” Journal of Development and Economic Policies 10 (2): 25–75.

Klasen, S. 1999. “Does Gender Inequality Reduce Growth and Development? Evidence from Cross-country Regressions.” Policy Research Report Working Paper 7. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Perry, G., W. Maloney, O. Arias, P. Fajnzylber, A. Mason, and J. Saavedra-Chanduvi. 2007. Informality: Exit and Exclusion. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Radwan, S. 2007. “Good Jobs, Bad Jobs, and Economic Performance: A View from the Middle East and North Africa Region.” In Employment and Shared Growth, ed. P. Pace and P. Semeels, 37–52. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 1999. “Kingdom of Morocco: Private Sector Assessment Update.” Report 19975-MOR. Washington, DC: World Bank.

________. 2003. “Unlocking the Employment Potential in the Middle East and North Africa toward a New Social Contract.” MENA Development Report. Washington, DC: World Bank.

________. 2009. “Morocco: Skills Development and Social Protection within an Integrated Strategy for Employment Creation.” Mimeo. Washington, DC: World Bank.