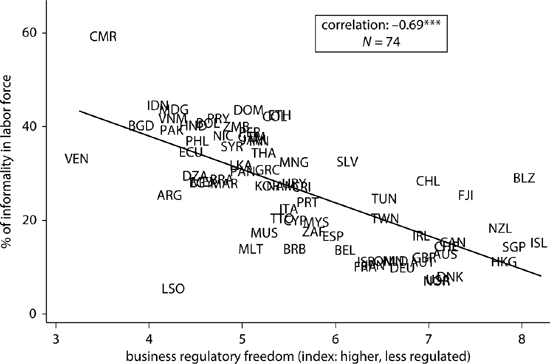

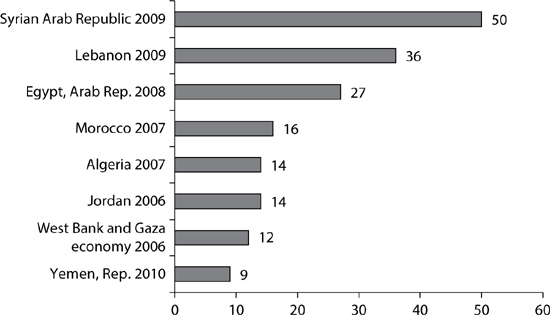

Figure 5.1 Correlation across Countries between the Size of the informal Sector and the Ease of Doing Business

Source: Loayza and others 2005.

Note: *** = 1% significance level.

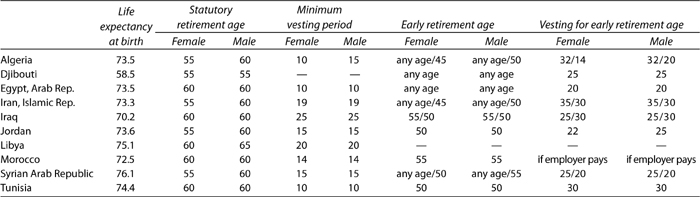

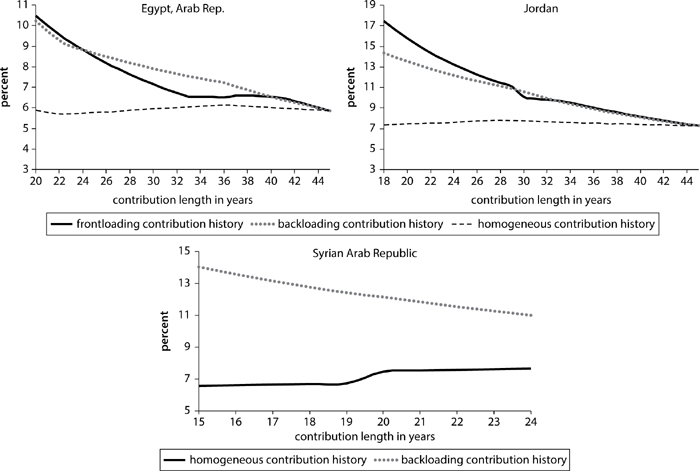

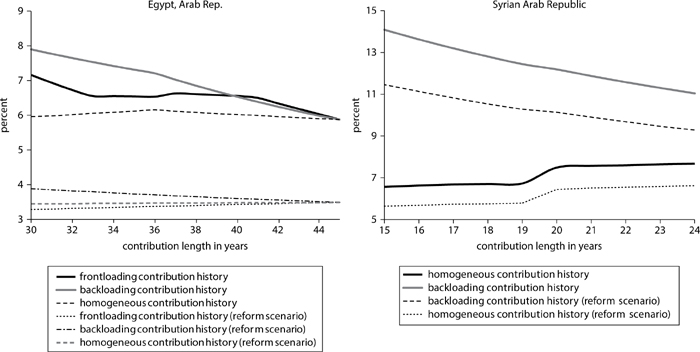

SUMMARY: Widespread informality implies that large portions of the workforce are not protected against old age, disability, and, often, health risks. Although the need to address these vulnerabilities provides a clear rationale for government intervention, the actual drivers of informality should inform policy levers and choices. Many institutional constraints determine the labor market segmentation that underpins informality in MENA, such as the design of pension systems, business and labor regulation, incentives and pay in the public sector, and the design of interventions to improve skills upgrading. This chapter analyzes these institutional constraints and presents a related set of policy interventions to effectively expand coverage and promote the creation of better quality jobs. First, the chapter discusses the importance of a healthy business environment that fosters competition and facilitates firm entry. Easing certain provisions of the labor legislation and keeping the cost of labor at a realistic level can help employment creation and reduce informality, especially if coupled with reforms geared toward protection of workers’ transitions. Realigning the pay and benefit package that is offered by public sector employment can reduce important distortions. Moreover, the low productivity dimension of informality, a phenomenon that is particularly relevant among the poorest countries in the region, calls for productivity-enhancing interventions, including those that aim to improve access and realign training and skill-upgrading programs to the needs of the informal sector. Second, the chapter discusses how reforms in the design of the social insurance system in MENA are critical for addressing informality. Limited legal coverage, the short minimum vesting requirements, generous early retirement provisions, and the use of an average wage measure from the final years before retirement for pension benefit calculation all contribute to limited coverage. Addressing the coverage gap will require governments to look beyond reforming the existing social insurance system to seek special coverage extension schemes targeted to the informal sector and to those with limited savings capacity.

This chapter is organized in two parts and addresses five distinct and complementary policy angles, each linked to the drivers of informality in the MENA region. Part 1 discusses institutional barriers to formality in MENA, including (1) the business environment, (2) labor market regulations, and (3) public sector employment bias, and provides relevant policy options. Part 1 also discusses the need for (4) addressing the productivity trap faced by informal workers, particularly through training and skills-upgrading interventions. Part 2 of this chapter focuses on (5) the social insurance system and presents barriers to coverage linked to the incentive design of pension systems in MENA. It presents policy options and recommendations for coverage extension through both improving the design of existing social insurance systems and introducing new special schemes targeting informal workers.

Although growth materialized in the last decade in MENA, not enough good jobs were created. Instead, informal employment grew, characterized by lower pay, lack of access to training, worse working conditions, and lower job tenure than formal employment. These conditions affect the vast majority of workers, whereas relatively few “insiders,” including those employed in the public sector, benefit from privileged circumstances. Reforms aimed at decreasing informality can potentially affect two aspects of this process: (1) by generating direct productivity gains and increasing job creation (increasing the “size of the pie”) and (2) by improving how equitably rents and benefits from the development process are redistributed. In this sense, many of the policy options discussed here can have an impact both on employment creation as well as on formalization and moving toward fulfilling work for all. Because of the multidimensionality of informality, it is important to acknowledge that a complex set of policy interventions might be needed to effectively overcome barriers to formality in a sustainable manner and help the growth process to become progressively more inclusive. Here, too, the mechanism through which formalization is achieved matters greatly for its effects on employment, efficiency, and growth. If formalization is based purely on enforcement, it will likely lead to unemployment and low growth. If, on the other hand, it is based on improvements in both the regulatory framework and the quality and availability of public services, it is likely to bring about more efficient use of resources and higher growth.

Certain features of the regulatory framework in MENA, encompassing the business environment, set of labor regulations, and nature of employment in the public sector, pose barriers to formality. Informality appears to be strictly intertwined with the development process and can be largely explained as a suboptimal private sector response to restrictive regulation. The first part of this chapter describes institutional barriers to formality and provides relevant policy options that extend beyond mere enforcement. In particular, this section addresses the need for a conducive business environment, the importance of less restrictive labor regulations, and, at the same time, more effective protection of workers’ income during employment transitions. Moreover, the first part of this chapter argues that the preference for public sector jobs in many MENA countries affects informality outcomes, requiring a realignment of incentives to limit queuing for these jobs. Finally, recognizing that many informal workers face a low-productivity trap because of their limited access to relevant skill acquisition, numerous skills-upgrading interventions are explored for specific MENA context.

Having to obey more stringent regulations may imply lower flexibility in firms’ employment and production decisions, and therefore, lower profits and productivity (Almeida and Carneiro 2005).

Excessive entry regulations and high taxes matter for informality and growth. Across countries, a significant correlation is found between the size of the informal sector and the ease of doing business (figure 5.1). Barriers to firm entry give discretion to public officials to exclude or advantage specific investors (World Bank 2009) and thus continue to perpetuate a dual model of development in which a few “protected” firms thrive and share rents while many small firms strive to survive. These barriers work as an impediment to growth, especially for the most productive among these outsiders, who might be excluded from important opportunities (or alternatively, who might have to divert resources from productive activities to rent-seeking activities). In parallel, corporate taxes are also systematically identified as a constraint to business and formalization. These constraints are particularly powerful in MENA. As highlighted in chapter 3, many firms in MENA never formalize, and even those that eventually register still operate informally for a significant amount of time. The region has the developing world’s highest share of firms that start out as informal (one-fourth) and the longest operating period before formalization (four years) among registered forms. The following discussion focuses on two main margins along which business environment reform can promote a more inclusive and dynamic private sector: (1) regulation of entry and (2) corporate tax reform.

Figure 5.1 Correlation across Countries between the Size of the informal Sector and the Ease of Doing Business

Source: Loayza and others 2005.

Note: *** = 1% significance level.

Could reforms in the regulation of entry improve firms’ incentives to formalize? Regulation is understood to be an important determinant of formalization. First, monetary and administrative registration costs (for example, a high number of procedures requiring extensive time and effort) increase formalization costs. After LAC, MENA is the region with the highest average number of procedures to start a business. Economies such as Algeria and Djibouti and the West Bank and Gaza economy stand out as places where the registration process is particularly cumbersome, requiring more than 10 procedures and an average of between 20 to 80 days to start a business (see chapter 3). Second, discretion in the application of these procedures (for example, with connected firms potentially benefiting from less strict enforcement) increases barriers to formalization for those firms that, quality-wise, would have the potential to compete on a larger scale and fully within the regulatory framework. Thus, uneven enforcement sustains an equilibrium where few connected firms thrive, a large number of firms operate informally, and new entrants face the choice of either investing in rent seeking to secure the benevolent eye of the bureaucracy or being virtuous and thus bearing the disproportionate brunt of taxation and regulation.

Reforms to the regulation of entry have been shown to have had positive, albeit moderate, effects on formalization. Interventions include (1) reducing the costs of registration, number of procedures, and minimum capital; (2) providing information and training to entrepreneurs (such as filling out forms); and (3) facilitating registration by establishing one-stop shops for registration. No experimental evidence exists in MENA on the likely impact of these reforms. In Mexico experiments were conducted and the impact evaluated (Bruhn 2011; Kaplan and others 2011). Broadly, these studies found that simplifying the process of business registration had a moderate impact on formalization of existing firms. In contrast, they indicate that the intervention increased formalization because of more creation of new businesses by former wage earners (Bruhn 2008). Another potential reason for the limited impacts on formalization of existing firms is that results might take time because of uncertainty about reform reversal, which is not captured by these analyses. Finally, the effect of these policies tends to depend on how many firms are at the margin of formalizing. Given the differences between MENA and LAC in this domain, the effects of this type of intervention could be significantly larger in the MENA region.

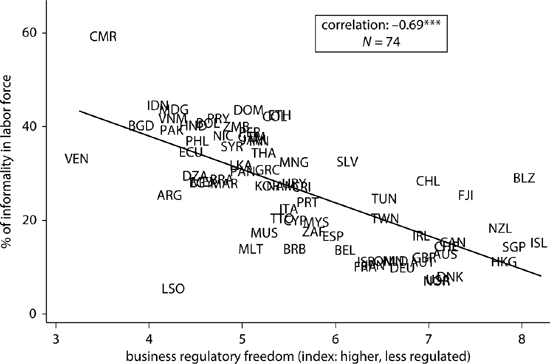

High taxation burden was the constraint to formalization most widely identified by micro- and small firms in Egypt and Morocco (figure 5.2). High taxes imply high costs of regulatory compliance if a formal business. Morocco’s corporate tax rate is one of the highest among developing countries: In 2007, it was second only to Pakistan and remained significantly above the average for developing countries in 2008. It is interesting that in Egypt (where corporate tax rates are below the developing countries average), a significantly smaller share of firms than in Morocco identified tax rates as being a major obstacle to formalization. The country’s profit taxes are also high relative to countries with similar income levels.1 Similar results were also found in countries such as Mexico, Brazil, and Bolivia. Lowering the corporate tax rate can affect tax revenue through three main channels: (1) existing formal firms may invest more and earn more income on which they pay taxes, (2) existing informal firms may be induced to formalize and start paying some taxes, and (3) new firms might be induced to operate formally. Evidence from other regions suggests that the net effect is likely to depend on whether a reduction in the tax rate is accompanied by additional enforcement and a reduction in exceptions. The short-run impact may also be negative; for example, Turkey lowered its corporate tax rate from 30 to 20 percent in 2007 and experienced a drop in overall tax revenues (Otonglo and Trumbic 2008).2 However, the converse happened in Egypt: When its corporate tax rate was lowered from 42 to 20 percent, it was accompanied by a significant increase in overall tax revenues. An experimental study in Brazil evaluated the impact of a reform that combines business tax reduction (of up to 8 percent among eligible firms) and regulation simplification and found interesting results. The emerging evidence indicates that the reform led to a significant increase in formality along several dimensions (Fajnzylber and Reyes 2010). In particular, the reform consisted of implementing a new simplified tax system for micro- and small firms, referred to as “SIMPLES.” The new national system consolidated several federal taxes and social security contributions into one single monthly payment, varying from 3 to 5 percent of gross revenues for micro-enterprises, and from 5.4 to 7 percent of revenues for small firms. Program eligibility excluded some sectors. This intervention suggests that this type of program can increase levels of registration and government revenues. Enforcement matters too. Overall, and not surprisingly, more frequent inspections are associated with lower underreporting of workers and sales (Almeida and Carneiro 2009). In MENA, firms report an average of four tax inspections per year (the highest regional average in the world). Such strict enforcement appears to be accompanied by widespread corruption, because informal payments were requested in 17 percent of inspections, significantly above the 7 percent reported in the LAC and ECA regions.

Figure 5.2 Obstacles to Formalization in Egypt and Morocco

Source: Calculations using informal ICA surveys from Morocco 2008 and Egypt 2010.

In the MENA region, investment climate reforms have accelerated in many countries in recent years. The evidence suggests that the implementation of reform matters greatly to private sector development. The recent MENA Development Report From Privilege to Competition (World Bank 2009) estimates that in response to previous reforms, private investment in the MENA region increased by only 2 percent of GDP, compared with between 5 and 10 percent in Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America. The same report estimates that the number of registered businesses per 1,000 people in MENA is less than one-third that in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and with less entry and exits of firms, the average business is 10 years older than in East Asia or Eastern Europe. Close to 60 percent of business managers surveyed did not think that the rules and regulations were applied consistently and predictably, whereas policy uncertainty, unfair competition, and corruption were identified as major concerns for investors. Discretionary enforcement of regulation is a strong deterrent to small entrepreneurs who start their businesses informally but are then forced to stay small to escape controls. Staying small may, in turn, make it prohibitively costly to formalize over time.3 Overall, the paucity of existing data on firms’ dynamics has not yet allowed identification of which margins matter most to promote formalization in the context of MENA. This is an important area where experimental evidence can effectively inform policy making.

Labor policies can affect informality through three main channels. First, excessive labor costs, whether due to labor regulation (such as high minimum wages, severance costs, or labor taxes) or strong worker bargaining power, can depress labor demand in the formal sector. Second, legislation can create incentives for workers to voluntarily work informally if perceived contributions exceed the benefits. Third, labor market institutions can impact productivity growth. Productivity gains arising from adoption of new technologies and production processes account for half of the differences in levels of economic development (the most important determinants of informality), not to mention long-run worker productivity and welfare more generally (World Bank 2007). Yet excessive restrictions on job reallocation or layoffs for economic reasons, or state- or union-induced inflexibilities, may reduce the adoption of such innovations.

Across countries, there is debate whether overly rigid employment protection legislation (EPL) is an important determinant of the labor market segmentations underlying informality. EPL is the set of rules governing the hiring and firing process that is provided through both labor legislation and collective bargaining agreements (box 5.1). Strong evidence suggests that overly rigid EPL tends to not only discourage hiring and firing but also may slow down adjustment to shocks, impede the reallocation of labor, and promote informality (OECD 2010). Recently, Fialová and Schneider (2010) established a statistically significant effect of EPL on the size of the informal sector in European Union (EU) countries. In the countries that have the most rigid EPL, the share of the informal sector is estimated to be about 3.5 percentage points higher than in countries that have the most flexible EPL. This result supports the view that unduly strict EPL leads some employers to hire workers informally to avoid costs imposed by the EPL. Specifically, strict EPL typically makes it harder for certain groups, including youth, women, and displaced older workers, to enter or reenter the labor market, at least on an open-ended contract.

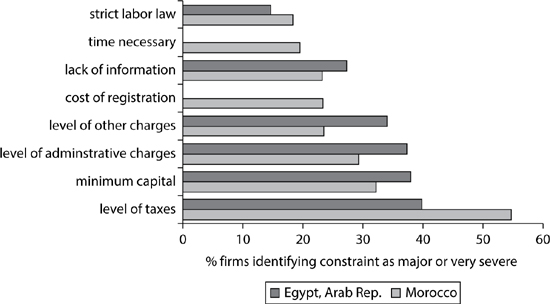

Perceptions of employers. The extent to which labor regulations are perceived by employers as a constraint to expanding their formal employment varies among MENA countries but in general is higher than in other regions. According to ICA surveys, labor regulations and mandatory contributions are considered by firms as a factor that constrain many enterprises from expanding formal employment. Table 5.1 shows the percent of firms indicating employment regulations and skills and education of labor are a major or severe obstacle. The MENA region has the highest share of employers dissatisfied with the existing labor regulations, although it should be noted that the skills and education of the labor force are a more significant problem for all regions than employment regulations. In Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria, labor regulations are perceived by firms as a major constraint to expanding formal employment, although this is true to a lesser extent in Algeria, Jordan, Morocco, and the West Bank and Gaza economy (figure 5.3). Manufacturing firms, service firms, and hotels in Egypt report that they would hire a net of 21 percent, 9 percent, and 15 percent more workers, respectively, if there were fewer restrictions on hiring and firing workers (Angel-Urdinola and Kuddo 2010). Similarly, according to enterprise surveys, firms in Lebanon would be willing to hire more workers (by an average of more than one-third of the workforce) in the absence of existing restrictions on labor regulation. The results of the enterprise survey analysis support those of previous studies (Pierre and Scarpetta 2006), showing that firms in countries with more stringent employment regulations are more likely to report labor regulations as a major or very severe obstacle, even after controlling for other factors such as GDP and unemployment. Overall, EPL as an obstacle to business growth tends to be more pronounced in countries that are more likely to enforce it (including through court challenges) and less of a problem in countries where the capacity of labor market institutions is weaker.

Table 5.1 Employment Regulations and Skills and Education of Labor as a Major or Severe Obstacle for Expanding Employment

Region |

Employment regulations |

Skills and education of labor |

Eastern Europe and Central Asia |

18.7 |

43.2 |

Africa |

17.3 |

32.6 |

East Asia and Pacific |

14.5 |

33.8 |

Latin America and the Caribbean |

29.5 |

42.5 |

South Asia |

19.0 |

24.8 |

Middle East North Africa |

36.2 |

Source: BEEPS 2008 and Enterprise Surveys.

Figure 5.3 Share of Firms Identifying Labor Regulations as a Major Constraint in Doing Business in MENA (%)

Source: World Bank: www.enterprisesurveys.org.

In most MENA countries, labor regulation is a key mechanism for protecting workers’ rights, because collective bargaining is not widespread. Trade unions in MENA rarely represent many workers effectively (although exceptions are found, as in Tunisia, where unions are influential social partners). Moreover, workers have limited ways of challenging private employers; for instance, in many countries in the region, strikes remain illegal. Thus, labor regulations have an important role to play in protecting workers (Angel-Urdinola and Kuddo 2010). Below, key aspects of EPL that can affect informality are explored, including (1) hiring regulations and contract types, (2) minimum wage, (3) firing regulations, and (4) tax wedges.

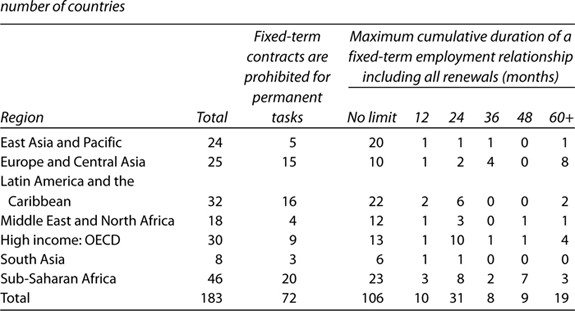

Hiring regulations and contract types. Hiring regulations in MENA are generally aligned with international standards, and MENA countries are joining the international trend in increasing the prevalence of fixed-term work contracts. In general, MENA countries do not have strict hiring regulations compared with international standards. In reforming labor legislation in the region, most attention is paid to relevant arrangements associated with fixed-term employment, which in the past was deemed to be an exceptional form of employment, conditioned by the nature of work or other objective conditions. In recent years, fixed-term work has been increasing not only in EU15 countries4 but also in MENA (table 5.2).5 Fixed-term contracts are heavily concentrated among young people and other new labor market entrants, such as the formerly unemployed and those with lower education levels, that is, among people who have weaker bargaining power. For these workers, fixed-term work can provide a bridge to formal employment and an opportunity to gain experience and skills. Among MENA countries, Morocco has the most restrictive laws: Fixed-term contracts are prohibited for permanent tasks, the duration is limited to 12 months, and renewal is prohibited. At the other end of the spectrum, no restrictions or limits are placed on the use of fixed-term contracts in Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, and the Republic of Yemen.

Table 5.2 Arrangements for Fixed-Term Contracts around the World in 2010

Source: Doing Business 2011 database.

Fixed-term employment contributes to more flexible labor markets. It provides a buffer for cyclical fluctuations in demand, allowing companies to adjust employment levels without incurring high firing costs. Fixed-term work also allows companies to reap market opportunities by engaging in projects of short duration without bearing disproportionate personnel costs. This is especially important in labor markets where permanent employment is protected by strict regulations and high firing costs. To counterbalance the latter, some countries have established a minimum service length of one to three years with the same employer for a worker to be eligible to claim severance pay, making short fixed-term contracts less attractive.

Although temporary jobs can be useful for promoting employment opportunities, they can also lead to undesirable labor market outcomes and informality. From the firm’s perspective, temporary jobs can provide a “screening” device, allowing the firm to evaluate workers’ ability or adequacy for the job. They can also act as a buffer, facilitating a firm’s adjustment to temporary demand shocks, thereby avoiding costly adjustments to its “core” labor force (European Commission 2010). Conversely, temporary contracts can simply be a convenient way for firms to reduce labor costs. From the workers’ perspective, fixed-term jobs are subject to higher turnover and pay lower wages on average. Estimates show that in the EU, temporary workers earn on average 14 percent less than workers on open-ended contracts after controlling for a number of personal characteristics. Temporary workers also tend to have reduced access to training provided or subsidized by firms. Labor market reforms are met with resistance by the segments of the society benefiting from the status quo, and so it is likely that fixed-term contracts will become more and more common. From the perspective of improving coverage, more temporary work contracts are desirable if they provide access to basic social risk management tools to workers.

Minimum wage and wage rigidities. Minimum wages affect informality through at least two channels. First, if the minimum wage is set higher than what employers are willing to pay for an unskilled worker, the latter’s employment is likely to be undeclared. Second, minimum wage policy can reduce tax evasion where underreporting is a problem (World Bank 2008) (see box 5.2 for a brief overview of minimum wages).

Although the evidence of the impact of statutory minimum wages on informality is limited, a large body of empirical literature, albeit inconclusive, exists on the impact of statutory minimum wages on worker flows, particularly in the United States. In the United States, although early studies tended to find a negative impact of minimum wages on job retention for individuals at, or close to, the minimum wage, more recent studies have generally found no significant impact (Abowd and others 2005; Zavodny 2000). Draca and others (2008) found that the introduction of a minimum wage in the United Kingdom in 1999 led to insignificant changes in firm entry and exit patterns (OECD 2010). Evidence from other countries is limited. Abowd and others (2005) found no impact of real minimum wages on entry into employment in France, but a strong positive impact on exit from employment. By contrast, Portugal and Cardoso (2006), exploring a specific Portuguese reform that in 1987 dramatically lifted minimum wages for very young workers, found that raising minimum wages had a significant negative effect on both separations and hirings. The effect of introducing a higher minimum wage appears to be large and negative in Colombia and small or negligible in Costa Rica and Mexico. In Brazil, evidence was found of a positive effect of an increase of minimum wage on employment; however, this was mainly the result of changes in the composition between hours worked and number of jobs (Maloney and Medez 2003).

Less is known about the impact of minimum wages on informal employment, but some findings show that a rise in the minimum wage has a positive impact on wages in the informal sector, through what is known as the “lighthouse” effect—as workers in the informal sector use the minimum wage as a reference for their own wages. Although minimum wages are not legally binding in the informal sector, they still seem to influence informal sector wage distribution. From the labor supply side, the minimum may be a benchmark for “fair” wages. On the demand side, employers may pay a wage comparable to the formal sector market wage for a particular occupation so that employees will not leave for a similar job in the formal sector, or employers may not be willing to provide all legislated labor benefits but at least will pay the minimum wage. In particular, Lemos (2004) found adverse effects of higher minimum wages on employment in both the formal and informal sectors in Brazil. Based on data from Costa Rica, a country with a complex minimum wage policy, Terrel and Gindling (2002) found that employers responded to a minimum wage increase by increasing the hours of full-time workers and decreasing them for part-time workers, who, in turn, switched to self-employed work in the informal sector. The subsequent increase in supply of workers in the informal sector then placed downward pressure on wages in the informal sector.

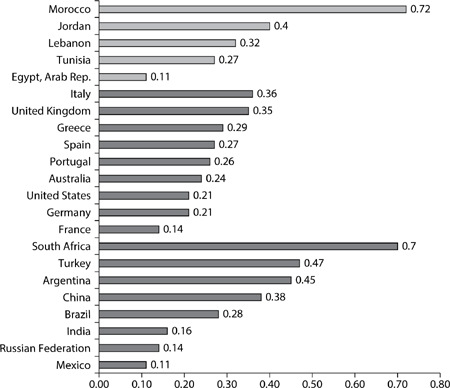

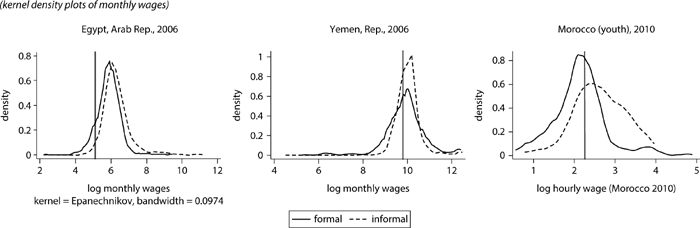

About half of all MENA countries do not have a legal minimum wage; those that do set them with considerable variation. Djibouti and the West Bank and Gaza economy are examples of MENA members that have no minimum wage in practice (Angel-Urdinola and Kuddo 2010). In countries with minimum wages, settings vary, complicating cross-country comparisons. For example, minimum wages are set at a monthly rate in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia, whereas Morocco has a minimum hourly wage. Figure 5.4 presents the ratio of minimum wages to average value added per worker in selected countries. In countries that have minimum wages in some form, the ratio of minimum wage to average value added per worker varies from 1.80 in Zimbabwe and 1.17 in Mozambique to 0.05 in Burundi and Gabon. In the reviewed MENA countries, the ratio varies from 0.11 in Egypt to 0.72 in Morocco. A high minimum wage can be damaging in some low-paid sectors and regions with below-average wages; it is also typically more damaging for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) because these enterprises tend to be more labor intensive and financially weaker. This likely contributes to keeping many SMEs smaller than they might otherwise be and gives them an incentive to remain informal. In Egypt, despite the relatively low minimum wage, a significant number of workers earn below the minimum wage, which suggests low levels of enforcement. However, the wage distribution for both formal and informal workers in Egypt seems quite centered (and compressed) close to the minimum wage; this suggests that the minimum wage may serve as a benchmark wage for new entrants in the labor market (figure 5.5).

Figure 5.4 Ratio of Minimum Wages to the Average Value Added per Worker in elected Countries in 2010

Source: Doing Business 2011 database.

Note: Because of a lack of consistent cross-country data on average earnings, the average gross national income per capita is used as a proxy for average earnings. This ratio is adjusted to represent the percentage of population of working age as a share of the total population.

Figure 5.5 Hourly Wage Distribution and Minimum Wages in Egypt, the Republic of Yemen, and Morocco

Source: Calculations using Egypt’s 2006 Labor Market Panel Survey.

Note: The vertical line illustrates the level at which the minimum wage is set; only wages in urban areas are considered.

Overall, minimum wages do not appear to be binding in most MENA countries. In most MENA countries, minimum wages are rather low, and sanctions for noncompliance with minimum wage rules are weakly enforced. Independent of how high or low the minimum wage is relative to average wages, the extent to which minimum wage policy affects employment outcomes and the wage distribution depends on its enforcement. Although most MENA countries with defined legal minimum wage have regulations on enforcement, enforcement is rather weak, inspections are rare due to a lack of resources, and fines are rarely imposed. A fairly significant mass of workers (those to the left of the vertical bar in figure 5.5) report wages below the minimum wage, which indicates that the minimum wage is unlikely to be a significant constraint to formal employment in most MENA countries. Centralized wage setting can, however, be an important determinant of informality. In Tunisia, in parallel to the general minimum wage, employer and employee representatives negotiate a pay scale based on professional levels in each sector; the differences are significant in some sectors. In reality, a relatively high minimum wage for university graduates is institutionalized, which likely contributes to the high graduate unemployment. The bargaining process is such that on the employee side, wages are monopolistically negotiated by unions whose members are all employed, thus possibly resulting in artificially high wages. This especially affects first-time job seekers. Those who cannot afford to wait for a formal job at or above the minimum wage will tend to accept lower wages in informal jobs.6

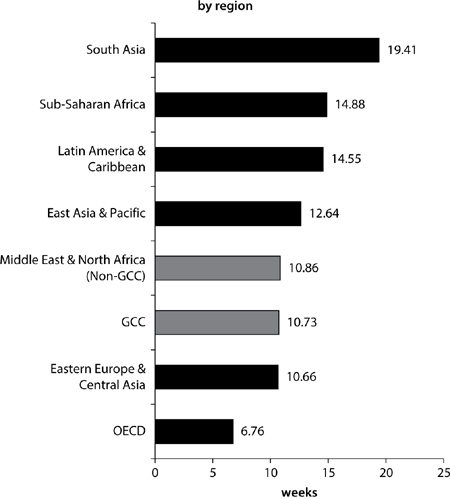

Firing arrangements. The strictness of firing regulations and the associated cost can affect the incentives of firms to keep workers informal. In general, the procedures for dismissal often require notification or even approval by unions, workers’ councils, the public employment service, a labor inspector, or a judge (table 5.3). Some countries also mandate retraining and reassignment to another job and establish priority rules for dismissal or reemployment of redundant workers. In Tunisia, companies must notify the labor inspector of planned dismissals in writing one month ahead, indicating the reasons and the workers affected. The inspector may propose alternatives to layoffs. If these proposals are not accepted by the employer, the case goes to the regional tripartite committee comprising the labor inspector, the employers’ organization, and the labor union. The committee decides by a majority vote: If the inspector and union reject the proposal, no dismissal is possible. The committee may also suggest retraining, reduced hours, or early retirement. Only 14 percent of dismissals end up being accepted. As a result, annual layoffs occur in less than 1 percent of the workforce, compared with more than 10 percent in the average OECD country. In Egypt, the employer has the right to close down or downsize the establishment, but it is a cumbersome process. Currently the employer may pay terminated workers one month of salary for each of the first five years of service, and one and a half month’s salary for each year after that, one of the most generous severance payments in the world. Eliminating or limiting some or all of the associated firing restrictions would give employers greater flexibility in responding to market fluctuations. Employers must have reasonable freedom to dismiss employees or they will be reluctant to hire and more inclined to operate in the informal sector.

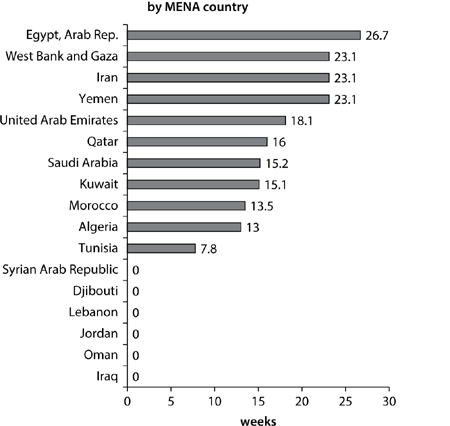

Most countries mandate severance pay with layoffs but differ in important details including extent of coverage, eligibility conditions, cause of dismissals, generosity of benefits, and level of benefits associated with seniority. Some countries require a minimum number of years worked before a worker is entitled to severance pay. In MENA severance pay for redundancy dismissal (for workers with 10 years of job tenure) is the highest in Egypt with 27 weeks of salary paid, followed by the Islamic Republic of Iran, the West Bank and Gaza economy, and the Republic of Yemen, at 23 weeks each (figure 5.6). In general, firing costs in poor countries are 50 percent higher than in rich countries. Some argue that this is justified because governments in poor countries do not have enough resources to provide unemployment insurance, so the cost should be borne by businesses. However, heavy regulation of dismissal is also associated with more unemployment, so those who want to work in poor countries frequently get neither a job nor unemployment insurance (World Bank 2004).

Figure 5.6 Severance Pay for Redundancy Dismissal (Average for Workers with 1, 5, and 10 Years of Tenure, in Salary Weeks)

In labor markets with less rigid and less costly firing regulations, appropriately designed unemployment insurance (UI) schemes can provide adequate protection to workers. This allows firms to discontinue unproductive employee–employer relationships, while maintaining adequate income protection through UI, a powerful support for creating higher productivity, good quality (formal) jobs. According to many (including Auer 2007; Auer and others 2004; Grazier 2007), legislative focus should be shifted from protection of jobs to protection of transitions, so that the individual risk of unemployment and income loss is reduced, while the potentially negative effects of job protection are avoided.

Workers themselves feel better protected by a support system for unemployment than by EPL (European Commission 2006). This is particularly important in a world characterized by the gradual disappearance of lifelong jobs and an increasing need for job mobility. Only a few countries in the region have UI systems, namely, Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, the Islamic Republic of Iran, and Kuwait (table 5.4). Even in countries with UI systems in place, such as Egypt, systems are underutilized because of a lack of public awareness about UI benefits among plan members, restrictive eligibility conditions, the difficulty of and the stigma attached to documenting a “just-cause” firing decision, and low overall layoff risks among covered open-ended contract employees (Angel-Urdinola and Kuddo 2010). The shift from rigid firing rules to less restrictive regulation accompanied by unemployment insurance creates the precondition for a more efficient allocation of resources. In simple terms, the easier it is for firms to discontinue a formal employment contract tomorrow, the more likely the firm will create that job today. This is especially true in sectors exposed to a volatile product market. Of course, the argument for economic efficiency should not justify reducing worker protection to inadequate levels, but rather shifting the form of protection from protecting jobs to protecting income for workers in transition through UI. By contributing to UI, employees and employers share the social costs of unemployment, but not in a manner that forces firms to maintain unproductive employment in downturns or to limit their incentives to open up vacancies when demand is stronger (World Bank 2008).

Table 5.4 Existence of Unemployment Protection Legislation around the World

Source: Doing Business 2011 database.

Tax wedge. Labor taxes create a wedge between the labor cost to the employer and the worker’s take-home pay. Studies suggest that a higher tax wedge reduces both employment and economic growth (World Bank 2007). For example, a 10 percent reduction in the tax wedge (the difference between the cost of labor and take-home pay) could increase employment between 1 and 5 percent (Kugler and Kugler 2003; Rutkowski 2003). The literature for developing countries and emerging markets economies is limited, but a World Bank study on Turkey concluded that labor tax cuts would not have a major impact on formal employment (Betcherman and Pages 2007). An across-the-board reduction of 5 percent in pension contributions paid by employers would bring about a 0.8 percent increase in employment overall and would reduce the unemployment rate by about 0.2 to 0.3 percent. The effect could be stronger (an increase in employment of almost 1.5 percent) if the reduction in pension contributions was targeted at workers younger than 30 years old, who have less bargaining power to capture most of the tax reduction in higher wages.

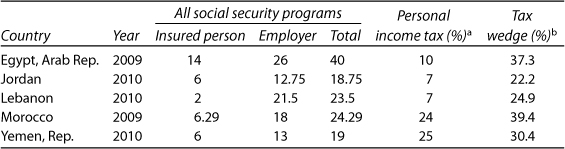

Labor taxes in countries such as Morocco (where they account for about 39 percent of total labor cost) and Egypt (37 percent) are as high as the average for OECD countries. In Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon, social security contributions are the dominant component of labor taxes (table 5.5). Social security contributions in these countries (paid by both the employer and the employee) account for the bulk of the tax wedge. In all reviewed MENA countries, social security contributions are paid largely by the employer; employees pay only a minor part. Table 5.5 shows the calculation of the tax wedge in some MENA countries, and figure 5.7 shows the tax wedge in various countries.

Table 5.5 Contribution Rates for Social Security Programs, 2009/2010, and Tax Wedge on Average Wages in Private Sector

Source: Calculations based on SSA and ISSA (2008, 2009, and 2011).

a. Data refer to effective rates on average wage.

b. The tax wedge is calculated as a sum of social security contributions paid by the employer and the employee, and the personal income tax is expressed as a percentage of total labor cost. Total labor cost is gross wage plus employers’ social security contributions. Gross wage is net wage plus employees’ social security contributions and the personal income tax.

Policy implications for MENA. MENA countries could ease certain provisions of labor legislation to achieve more compliance and improved employment outcomes, while shifting from protection of particular jobs to protection of transitions. Overall, even though certain provisions in labor legislation in some MENA countries might be rigid de jure, de facto they are widely evaded. It is unlikely that merely improving enforcement would result in reducing informality. As discussed in this section, the rigidity of certain labor regulations in some countries contributes to the prevalence of informality (for example, hiring arrangements in Morocco, and firing arrangements in Tunisia and Egypt). A shift toward a richer and more flexible set of labor contracts (including more fixed-term contracts and fewer open-ended contracts), despite their drawbacks, would provide opportunities for young workers and new entrants to join the formal sector through flexible working arrangements with social insurance coverage. Such policy reforms that ease regulations and make them more realistic to comply with should be supported by a reform of social protection systems to better protect the income position of workers and their employment transitions.7 For example, recent experience shows that moderately strict EPL, when combined with a well-designed system of unemployment benefits and a strong emphasis on active labor market programs, can help create a dynamic labor market while also providing adequate employment security to workers (OECD 2008). Adequate safety nets could also play an important role in protecting workers from sudden job loss, help them transition between jobs, and prevent more people from slipping into poverty. The newly legislated unemployment insurance schemes in Jordan and Egypt provide an example to be considered by other countries in MENA.

Keeping the cost of labor at a realistic level via affordable social security contributions in MENA and relaxing wage rigidities are likely to reduce informality. In general, institutionalized minimum wages in MENA are neither high (with the exception of Morocco) nor binding. Yet centralized wage setting mechanisms, such as those discussed in the case of Tunisia, contribute to informality by artificially setting high wage floors for certain occupations and skill levels. In addition to keeping minimum wages at low levels that can be realistically enforced, wage-setting mechanisms in MENA should benefit from some kind of quantitative anchor to provide an objective baseline measure on changes in productivity. In countries where minimum wages are high (whether economy wide or sector specific), and where it is not politically feasible to reduce them, governments could consider reducing the minimum wage for youth to at least improve transitions of new entrants into formal employment, while maintaining the higher-level minimum wages that protect well-established workers. This section has also shown that the cost of labor attributable to labor taxes is not very binding in MENA, with the exception of Morocco and Egypt. In general, tax wedges could be reduced through social insurance reforms that reduce the social security contribution rates (as already legislated in Egypt) or by shifting a portion of the labor taxes toward other general revenue taxes such as consumption taxes.

Engaging in a more inclusive social dialogue is key to sustaining these types of reforms. Important political economy aspects to labor market reform are found. In particular, the traditional tripartite structure that convenes government actors, trade unions, and employer representatives is likely to show a bias for the status quo of protective regulation for employed, unionized workers. Including representation from the outsiders, informal workers, youth, and the unemployed would likely rebalance the dialogue toward facilitating entry in labor markets, improving mobility, and promoting a more equitable redistribution of returns across different strata of the population.

The widespread preference for public sector jobs in many MENA countries has important implications for informality. The presence of large public sectors has been explained as the consequence of an implicit social contract in the Arab region that promised well-compensated public sector jobs to those reaching higher levels of educational attainment (Yousef 2004). Recently hiring has slowed, and in practice, public sector jobs are offered only to those who are sufficiently patient to queue for them. Yet the preference for public employment is very widespread. For example, according to the 2010 youth survey in Egypt, 70 percent of youth say it is best to work for the public sector. This preference for public sector jobs is grounded in a rational evaluation of costs and benefits. On average, public sector jobs (1) are better compensated than similar private sector jobs; (2) offer full job security, good fringe benefits, and solid social status; and (3) tend not to require as much effort as private sector jobs. Jordan, Syria, and Egypt have the highest proportion of the workforce in the public sector in the region (30 percent in each of Jordan and Syria and 39 percent in Egypt). In Syria, the average public sector wage is 32 percent higher than the average private sector wage (representing both formal and informal workers). Even in Egypt, where public sector pay is considered low, the average wage in the public sector is 6 percent higher than the average wage in the formal private sector.8 The public employment bias and the queuing phenomena also exist in Jordan, where public sector wages are on average 20 percent higher than private sector wages.9 Bodor and others (2008) show that in Morocco public sector employees, regardless of the level of education, have better career paths, in terms of wages and pension benefits, than those working in the private, formal nonagricultural sector and the informal agricultural sector.

The existence in some countries of a distinct single registry for those seeking public sector jobs indirectly contributes to the prevalence of informality. In Jordan and Syria, those who wish to work in the public sector must register with an agency. This registry is the institution of the “queue”; once registered, an individual does not need to exert any effort to procure a public sector job, he or she just needs to wait for his or her turn in the queue. In Syria, the total number of registered jobseekers was over 1.7 million persons in 2009. When the Syrian government attempted to use this registry to offer training, with the opportunity for private sector placement upon conclusion, it found that those in the registry were typically unwilling to accept the prospect of formal private sector employment. They believed that presence in the social insurance agency’s administrative records would lead to deletion from the public sector job queue. Therefore, only a quarter of those offered formal jobs took them.10 In contrast, informal employment was acceptable to the same individuals; many of them were already engaged in informal employment.11

In the short run, MENA governments should consider eliminating institutionalized public sector employment queues. In the medium and long run, a reform of civil service by realigning incentives is needed. Modernized public employment and placement services should require active job search effort from applicants. Placement services should place workers based on their interests, training, and skills, instead of an expressed preference for public or private employment. Workers currently in formal private sector jobs should not be disqualified from moving into public sector jobs later in their careers. In the long run, civil service reforms should establish stronger performance evaluation measures, linking worker compensation to performance. Further, public sector wage scales should be rationalized so they no longer constrain flow of talent into the private sector.

The productivity dimension of informality is especially predominant in the poorer countries, in rural areas where low-skilled workers are engaged in micro-entrepreneurship and low-yield agricultural work. Programs aiming at increasing productivity in the informal sector are potentially important interventions to promote inclusive growth and avert a productivity trap. However, effectively tackling productivity improvements in the informal sector, particular in rural areas, is a complex agenda, which involves not only effectively upgrading skills, but also creating opportunities that would allow for returns to training to materialize. As such, complementary investments in infrastructure and access to markets are needed. An exhaustive analysis of policies to increase productivity is outside the scope of this report; this section focuses on policy and program options that improve access to training opportunities and realign training programs to the needs of informal workers.

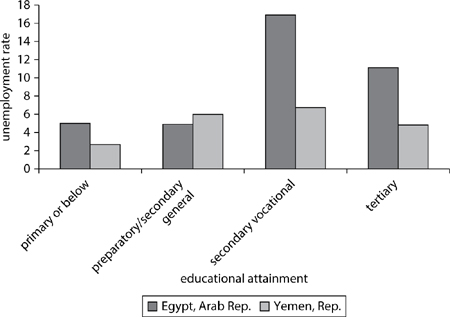

Improving access to training. Informal workers have limited opportunities to benefit from training provided by governments, employers, and private training providers. Active labor market programs (ALMPs), which include training and skills-upgrading programs, are interventions provided by the government or by nongovernmental organizations that aim at increasing workers’ employability. In MENA, government provision of such programs is mainly directed to the unemployed. This may be because of the belief that the unemployed are more vulnerable and worse off than the employed, regardless of job quality. However, the working poor could actually be worse off than certain groups of the unemployed in some countries. Workers from higher income households might be able to afford to be unemployed and queue for better quality jobs, whereas those from poor households are forced to take available low-quality and low-wage informal sector jobs. Figure 5.8 shows that unemployment is lowest among those with the lowest skill levels. This would suggest that those who can afford to stay in the education system could also be those who can afford to stay unemployed and wait for better jobs. In addition to government provision, the private sector plays a large role in providing fee-based training programs in MENA. However, an evaluation of privately provided ALMPs targeting young people in MENA revealed that the informal sector rarely has access to such programs: 80 percent of beneficiaries are educated males from middle- or high-income groups in urban areas (Angel-Urdinola, Semlali, and Brodmann 2010). It is also worth mentioning that only 5 percent of all surveyed training programs target rural areas, where a large share of informal workers reside. Finally, as shown in chapter 3, informal salaried workers working in informal firms or small firms are less likely to receive on-the-job training where they work.

Figure 5.8 The Relationship between Educational Attainment and the Unemployment Rate in Urban Egypt and the Republic of Yemen

Source: Egypt 2006 Labor Market Panel Survey, the Republic of Yemen 2006 Household Budget Survey.

To address low access to training, as well as to provide incentives for firms and workers themselves to pursue training, governments may extend their provision of ALMPs to informal sector workers through direct targeting (for example, through training cooperatives or vouchers). Training vouchers can be used to empower recipients to buy training in the open market and thereby promote competition between public and private providers of training and the efficient delivery of training services. The Jua Kali program in Kenya, which offered training vouchers to those working in the informal sector in the mid-1990s, provides an interesting perspective on the response of public training institutions to the demand for skills created by the vouchers. The Jua Kali vouchers produced a positive supply response to the demand created for skills, but mainly from master craftspersons in the informal sector and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Programs were tailored to the needs of voucher recipients and offered in off-hours to fit work schedules. The Jua Kali voucher program was successful in its pilot stage in expanding the supply of training to workers in the informal sector. Evidence was also noted of its positive impact on the earnings of participants as well as strengthened capacity of local Jua Kali associations responsible for distribution of the vouchers (Steel and Snodgrass 2008). A commonly used policy intervention to address the underprovision of training by firms is the establishment of training funds, financed through general revenue or some payroll taxes. However, financing training through general revenues is regarded as less distorting to employment outcomes than through payroll taxes (and thus preferable). Training funds can be used to target firms with low levels of training, such as SMEs. For example, in the Republic of Korea, all firms pay a training levy, but the government provides reimbursement to employers who offer training. When the government found that mostly larger firms were actually providing training and benefiting from the reimbursement, they provided additional incentives to SMEs to establish a training consortium through which they could collectively mobilize resources for training while benefiting from a higher reimbursement rate and a subsidy to hire financial managers (Lee 2009).

Tailoring training to informal workers’ needs. Traditional training programs generally require a minimum level of literacy and proficiency and do not adequately address the need for a general and flexible set of skills that is typical of informal employment, especially in rural areas. General literacy skills are a barrier to productivity as well as a barrier for informal workers to access and benefit from training programs, especially in rural areas. Although the expansion of the basic education system in MENA has been remarkably successful in initially enrolling almost all children in rural and urban areas, the dropout rates are still high, and education quality often lags behind in rural areas, leaving rural agricultural workers with low levels of literacy.12 This is especially important given the evidence that literacy is associated with increased productivity. An often cited example is that literacy improves the use of fertilizers when workers can adequately read and comply with directions written on the labels. General education reforms addressing the low literacy and quality of education, particularly among rural workers, are necessary conditions for improved productivity in the medium term. However, in the shorter run, rural workers could benefit from training programs that are made accessible to them, and for which literacy is not a necessary precondition. Such training should also be associated with support for micro-entrepreneurship and accessing markets, so as to broaden the set of available opportunities.

How training is delivered matters too. Training programs for the informal poor need to offer clear, concrete, and immediate reasons to motivate enrollment and ensure that individuals participate and benefit from the program. Many informal workers are too poor to take time off from work to participate in daytime training. Thus, programs should provide opportunities to combine earning and learning as well as flexible schedules. If alternative schedules are offered, such as evenings and weekends, beneficiaries can then continue to contribute to household income and/or take care of their children during regular hours, thereby increasing beneficiary retention (Singh 2005). Moreover, experience shows that nonformal training programs should be adapted to the work context surrounding the beneficiaries, that the teaching methods should be participatory, and that some of the program instructors should ideally come from the neighborhood itself, because they bring with them insights on community needs. Unless the training is provided in the rural villages or is hands-on at the homes of the informal workers, it can be difficult to attend for several reasons: lack of transportation, insufficient infrastructure, and lack of lights along roads. Women face additional challenges because they may not be allowed to travel without male company.

Although school dropouts constitute a majority of informal workers in many MENA countries, very few “second-chance” programs are aimed at providing learning in a nonformal manner. Second-chance programs can provide enhancement of an individual’s literacy, work skills, equivalency education, and life skills training, crucial characteristics that facilitate integration into society. Education equivalency programs are designed for those who have missed opportunities for early and traditional education and are unlikely to return to a formal learning environment. People who have dropped out of school at an early age are generally poor and very vulnerable. Second-chance programs are usually provided in a nonformal manner (often via accelerated learning) because this increases the likelihood of reaching informal and vulnerable workers. Life skills include social and coping skills, and improving relations with family, community members, and authority figures, while increasing the beneficiary’s own self-confidence. They can also include counseling and mentoring and components related to risky behaviors. Participants are more likely to benefit from work skills training once life skills and coping mechanisms are included in the general training (Angel-Urdinola and Semlali 2010).

The traditional approach to training programs in the MENA region is not well suited for the informal sector. Training appears to be associated with a positive impact on labor market outcomes when offered as part of a comprehensive package. According to the survey of privately provided ALMPs in MENA, about 70 percent focus solely on hard skills and are provided in classrooms, less than 20 percent provide some type of practical experience and/or apprenticeships, less than 35 percent focus on soft skills, and only 14 percent provide some type of employment services and/or labor market intermediation (Angel-Urdinola, Semlali, and Brodmann 2010). Country-specific evidence confirms that similar approaches also prevail among publicly provided ALMPs. Many countries, particularly in the OECD and Latin America, have moved toward a comprehensive training model that includes provision of classroom and workplace training, monitoring, job search and placement assistance, and soft skills training. Evaluations of “comprehensive” youth programs from Latin America indicate that programs can have a significant positive impact on employment and earnings of program participants, especially for women, if they are organized with flexible schedules, based on public-private partnerships (that is, demand driven), combined with internships and practical experience (in addition to in-class training), provide a combination of soft and hard skills, and are monitored and assessed for impacts. In many Latin American economies, youth unemployment rates soared during the late 1990s. To address this, the Chilean government designed what is known as the “Chile Joven” program, which offered comprehensive “demand-driven” training programs to unemployed youth. The program was so successful that similar models were customized in Argentina, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and República Bolivariana de Venezuela. Depending on the specific needs identified, these programs can be targeted to either the general unemployed youth population or to specific marginalized groups.

If improved and combined with theoretical knowledge taught by Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), traditional apprenticeships13 could contribute to more productive employment within the informal sector in MENA. Traditional apprenticeships are distinct from formal apprenticeships, which are registered with a government agency and administered by employers. The flexibility of traditional apprenticeships in combining hands-on training, work and learning, their affordability and self-financing, their connection with future employment, and their generally low entry standards make them attractive to disadvan-taged informal workers. However, master craftspersons rarely provide theoretical knowledge alongside practical experience and often teach outdated technologies, and there are few market standards available for judging the quality of the training provided. Traditional apprenticeships suffer from the low education of those being trained, and the choice of trades tends to follow gender biases (Johanson and Adams 2004). If public financing for TVET institutions shifted to focus on outcomes (such as success in serving target populations of master craftspersons and apprentices) rather than financing inputs (such as classrooms, courses offered, or instructors hired), both apprenticeships and TVET could be made more relevant. Performance-based budgeting for public institutions could provide incentives to upgrade technical skills for master craftspersons and improve their pedagogy (Ziderman 2003). More attention and accountability could be given to these institutions in partnership with apprenticeships for addressing the low levels of basic education that handicap training of apprentices and master craftspersons and for providing the complementary theoretical training needed to accompany the practical training of apprenticeships (Van Adams 2008).

Training programs targeted toward the low-skilled, self-employed, and micro-entrepreneurs among informal workers, or those individuals with the inclination to become self-employed, could help informal workers transition into higher productivity and higher value-added self-employment. The great majority of participants in informal self- or household-based enterprises have had little formal education or training when entering self-employment. Some, especially woman entrepreneurs, may have had none at all. The knowledge and skills used in their businesses have likely been acquired from parents and other relatives in family enterprises. The self-employed can benefit from both technical training specific to their industry, such as on the use of modern production techniques in agriculture, as well as general entrepreneurship and business skills training. The latter could include bookkeeping, financial literacy, marketing, communication, life skills, and simple risk management. International experience has shown that a comprehensive package offering a set of services that both includes training and facilitates access to credit can be successful in improving entrepreneurial ventures. Moreover, micro-franchising programs are an emerging approach that entails helping individuals replicate an existing business rather than starting an original one. Box 5.3 presents two case studies of productivity-enhancing programs from Egypt and Jordan.

Finally, moving toward more integrated and innovative social safety net systems that link income support to the poor with strategies to foster productivity should be considered in the context of MENA. The “Chile Solidario” Conditional Cash Transfer Project provided the poor with the means to attend training while linking them to employment opportunities. This well-targeted social protection project assisted extremely poor families, mostly in Chile’s rural areas. A social worker worked with anyone in the family in need. Each individual’s needs were evaluated and the social worker then linked the person to the appropriate services, including literacy classes, soft skills training, help with job searches, links to internship opportunities/subsidized employment opportunities, or self-employment assistance programs. The connection to the social worker was important for understanding the needs of the client and for accurately informing the client of available opportunities, because many poor are not aware of the services available to them. Conditional Cash Transfers in the form of a stipend were provided conditional upon training participation. Without this stipend, the poorest would not have been able to participate (Angel-Urdinola and Semlali 2010).

Numerous barriers to formality exist in MENA, requiring a complex set of policy interventions. Restrictive business and labor market regulation, the prominent role of the public sector as employer in a number of countries, and the productivity gap facing informal workers are all important barriers to inclusive growth and formalization. Although different and complementary policy interventions that relax these barriers can be effective toward this goal, the process of formalization matters, and policy interventions to address informality should extend beyond mere enforcement and should aim to reduce informality in a sustainable manner while helping the growth process become progressively more inclusive.

A healthy business environment and labor regulations that foster more mobility in labor markets, while protecting workers during job transitions, are important. The evidence suggests a negative correlation between the ease of doing business and the size of the informal sector. In MENA, barriers to entry, high taxes, and discretionary enforcement of regulation all collude to promote informality. Simplifying entry regulation, reducing compliance costs, and moving toward a fairer implementation of regulation are all necessary, and emerging evidence from other countries suggests that these interventions can be effective to move beyond informality. A large portion of employers in MENA perceive labor regulations as a major obstacle to business development and more employment growth. In some MENA countries, certain labor regulation provisions are rigid, including hiring arrangements in Morocco and firing arrangements in Tunisia and Egypt. Rigid EPL promotes informality, because firms can respond to rigid labor regulations by reducing overall employment or shifting employment into conditions of informality. Easing certain provisions of labor legislation to achieve more compliance, supported by a reform of social protection systems to better protect the income position of workers and their employment transitions (for instance, through the introduction of unemployment benefits and a strong emphasis on active labor market programs), can decrease informality and promote employment creation. In parallel, it is also important to keep the cost of labor at a realistic level, including through affordable social security contributions. The generosity of public sector employment conditions (including pay, benefits, and job security) in some countries also contributes to higher informality and important segmentations, making the need for a reform of civil service even more pressing.

Many informal workers face a productivity trap. Especially in the poorer countries and in rural areas, the low productivity of jobs is the predominant aspect of informal employment. Low productivity is a result of different factors, including poor skills and limited opportunities, particularly in rural areas. The evidence shows that informal workers consistently have limited access to training and skills-upgrading opportunities. Although complementary investments in infrastructure and access to capital and markets will be necessary to increase the returns associated with skills upgrading, targeting such programs to informal workers can be one effective way to address the productivity trap. Providing incentives to firms (such as through training cooperatives for small firms) and workers (such as with vouchers) to engage in training will address some of the determinants of underprovision of these programs. To make these interventions more effective, reorienting and tailoring the delivery and design of training toward the particular needs of informal workers is necessary. Second-chance programs, traditional apprenticeship, and training specifically designed for the self-employed and micro-entrepreneurs are examples of interventions that are likely to be effective in the context of MENA.

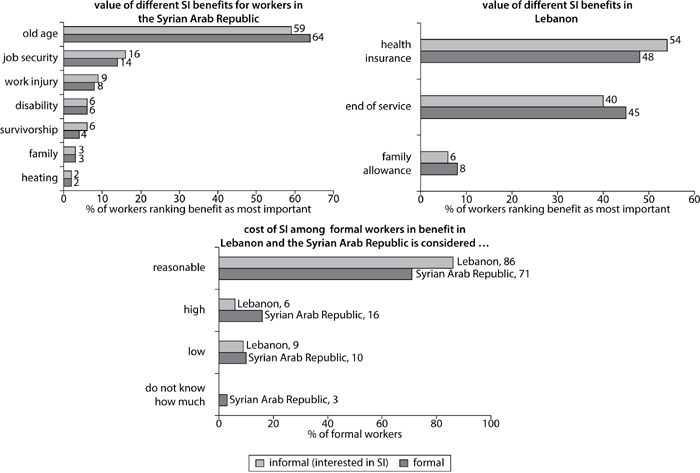

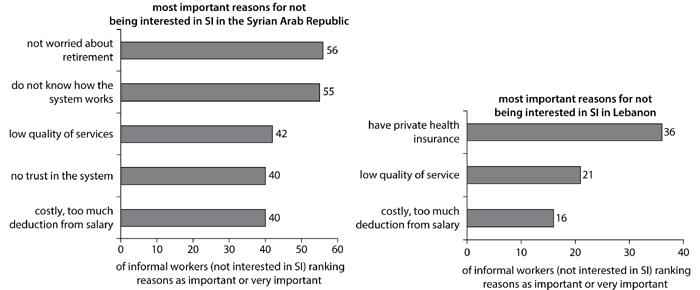

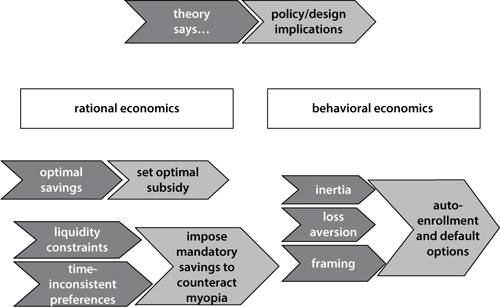

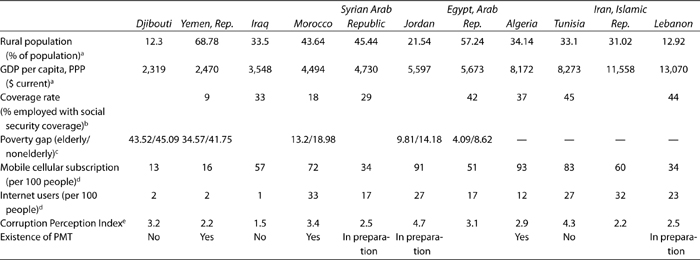

Lack of social insurance coverage exposes workers and their families to important risks and vulnerabilities. In MENA, these vulnerabilities loom large, with about 67 percent of the labor force not protected against a plethora of social risks, of which loss of income in old age may be the most pressing. Government interventions that effectively expand access to risk management instruments can be beneficial both from the perspective of individual/household welfare and for society as a whole, because evidence exists that private markets are likely to underinsure social risks, such as loss of income-generating capacity due to old age, disability, health conditions, or layoffs. This is particularly true for the poor, who might engage in suboptimal strategies, such as selling productive assets or withdrawing children from school, to respond to shocks. From a societal point of view, important negative externalities can be found from having too much uninsured risk, including an adverse impact on productivity. If the rationale for government intervention is clear, assessing what drives lack of coverage is key to informing which policies are most likely to succeed in expanding it. For example, if most workers are observed to voluntarily opt out of social security systems because of a rational cost-benefit analysis, then improving the perceived quality of public service, including outreach and communication about benefits, would be needed. Specific design features of pension systems, including vesting periods, early retirement, and legal coverage provisions, might also provide different incentives for workers to contribute to social insurance. Furthermore, a significant portion of the population might not possess sufficient saving and contributory capacity to pay for the true cost of the socially optimal degree of protection against these risks, which would justify government intervention to improve coverage with some level of subsidy beyond traditional contributory mandatory social insurance schemes. A complex set of reforms is likely to be needed, which includes moving beyond a sole focus on enforcement of mandatory social insurance rules (especially under existing designs and lack of financial sustainability) toward a coverage extension strategy that acknowledges the realities of the informal economy in MENA.

Part 2 of this chapter introduces a conceptual framework for social insurance coverage extension policies. In this context, it discusses design features of pensions systems in MENA, with special attention to the need for improving the design and incentive structure of existing formal sector pension schemes as a precondition for feasible and successful coverage extension efforts. Following that, a structured description of alternative coverage extension strategies is presented, including a set of guiding principles to select such strategies for specific vulnerable population groups. Finally, it concludes with a section on how the often disregarded evidence from the emerging field of behavioral economics could support better designed social insurance coverage extension policies.

Although the costs and benefits to informality have been discussed, the vulnerability associated with informal employment is a social concern requiring government action. The main objectives of this section are to describe (1) how the design of social insurance systems affects incentives to be informal and (2) the policies governments should consider to alleviate the social problems caused by informality. In line with the emphasis of this report on informal employment, policies aimed at extending social insurance coverage are the focus of the following discussion, because they provide a means for individuals to reduce vulnerability and excessive exposure to social and economic shocks, and to ultimately improve social welfare.

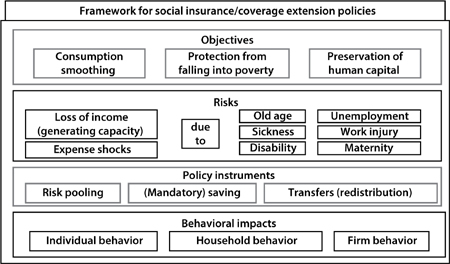

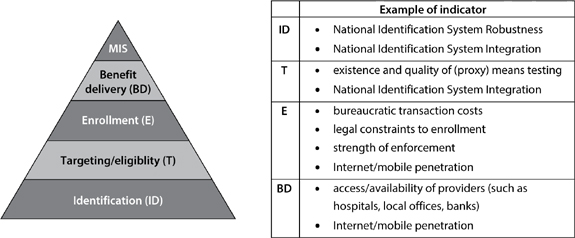

The ultimate objective of coverage extension policies is to improve social welfare by providing individuals with access to the risk management tools of social insurance systems. A framework for social insurance/coverage extension policies is illustrated in figure 5.9. Social insurance systems provide protection against certain social and economic risks, such as the loss or sudden reduction in income (generating capability) due to old age, disability, work-related injury, death of an income-generating family member, sickness, loss of income due to maternity, or loss of a job.14 The realization of any of these risks, at least temporarily, undermines an individual’s employment income-generating capacity, and in some cases a medical care-related expense shock is incurred as well (for example, with sickness, disability, and work injury). The social insurance system is designed to intervene in such cases to at least temporarily provide income support and cover a significant portion of the shock’s expenses. These interventions are in line with the underlying objectives of (1) consumption smoothing (limiting the extreme fluctuation of individual and household consumption and welfare), (2) poverty alleviation (preventing social and economic shocks from forcing individuals or households into poverty), and (3) preserving investment in human capital (in the cases of health insurance, disability, and work injury benefits, there is a direct objective to prevent the—further—deterioration of health). In a broader social insurance context, temporary income support measures are justified as an attempt to prevent households from reducing their investment in human capital (such as spending on education) when social and economic shocks occur.

Figure 5.9 A Framework for Social Insurance/Coverage Extension Policies: Objectives, Social and Economic Risks, Policies, Instruments, and Behavioral Impacts

Source: Adaptation of the broader framework presented in Robalino and others 2010.

Social insurance programs typically entail a combination of risk pooling, (mandatory) saving, and explicit redistributionary transfer mechanisms (Holzmann and Koettl 2010). The optimal choice of a policy instrument depends on the nature of the risk. In general, low-probability shocks with potentially devastating impact are best protected against through risk pooling. In contrast, the loss of income-generating capacity in old age is a high-probability (thus predictable) event; therefore (mandatory) saving-type pension schemes are more appropriate. Saving and risk pooling are, in theory, contributory mechanisms ensuring the financial sustainability of the social insurance systems and ensuring that any redistribution among plan members happens based only on the ex ante unknown realization of risks (that is, in a random manner). The discussion to follow defines a necessary role for redistributionary transfers, especially for ensuring protection to low saving capacity individuals (and households) who cannot afford to pay the true cost of a universally guaranteed social insurance package. Such transfers play an especially critical role in coverage extension policies.

Understanding behavioral impacts is especially important for the design of coverage extension policies given the need to induce voluntary compliance and enrollment. Given the nature of informality, relying only on enforcement of mandates is not sufficient and can be counterproductive. Economic actors respond to incentives. For example, self-employed individuals decide to register and enroll in social insurance schemes based on whether they find their participation beneficial given the information they have and the level of effort required. Firms make employment offers with or without associated enrollment in the mandatory pension system dependent on factors such as the related additional cost of labor. Employees and employers may negotiate over a worker’s enrollment as part of a total compensation package. Households may optimize social insurance participation of one household member based on the degree of protection offered to the entire household. A focus on expected behaviors is necessary for understanding the true effect of policy interventions. Later in this chapter it will be shown that the lessons learned from behavioral economics about bounded rationality can significantly inform the design of coverage extension policies.

The link between pension design and coverage: A review of key options. This section describes an array of pension system designs and their features as related to coverage. The designs of old-age pensions vary greatly in achieving wide coverage, and few systems manage to provide access specifically to informal sector workers. In their simplest form, old-age pension systems are mandatory saving schemes that prevent myopic undersavings for old age and curb intentional undersavings and abuse of often generous social safety nets that redistribute income to those in need.

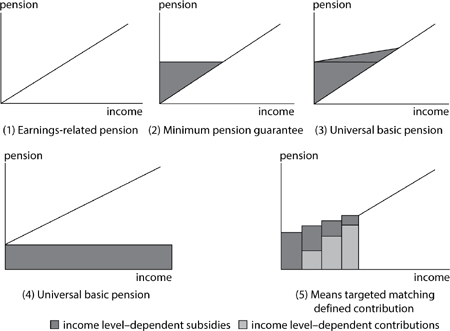

Earnings-related pension schemes (see panel 1 of figure 5.10) provide old-age pension benefits dependent on individual contributions; they work, in effect, as saving mechanisms from the perspective of the individual and can be designed as defined benefit (DB) or defined contribution (DC).15 In MENA, pension benefits are determined through a set of parameters taking into account the individual’s contribution performance over the active life cycle (such as number of contributory periods, and some average wage measure reflecting earnings before retirement or over the entire contributory life span). These are known as DB schemes. The expected value of pensions may be quite different than the value of lifelong contributions. If the pension benefits are systematically higher than the value of contributions, contingent government liabilities emerge, giving rise to implicit pension debt. Mandatory pension schemes in MENA tend to be pay-as-you-go (PAYG), as opposed to “funded,” in their underlying financing mechanism, with pension benefits financed by the contributions of active age plan members.16 Pure earnings-related mandatory pension schemes are rare and lack the minimum old-age income feature that most modern pension schemes possess in one way or another. By definition, mandatory earnings-related pension schemes in general, regardless of their design or financing mechanism, do not offer protection to informal sector workers; these schemes typically require that employers register their employees with the social insurance authority, report their earnings. and pay wage-proportional employee and employer contributions, while earnings of informal sector workers are rarely observed. Later in this section, the specific design features of PAYG pensions systems in MENA that pose challenges to participation are explored.

Figure 5.10 Old-Age Pension Design and Coverage: Options Ranging from Pure Earnings-Related Pensions to Pure Noncontributory Flat Pensions