Italian Opera of the Primo Ottocento: Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, and Their Contemporaries

IN THE EARLY PART of the eighteenth century, Italian opera had been predominant in every country of Europe except France; by the end of the century, it was one among several national schools. Composers of Italian birth who worked mainly outside their own country—Sacchini, Salieri, Cherubini, and Spontini, among others—tended to merge their national characteristics in an international style of which the most conspicuous examples were the works of Gluck’s followers in France and, in a later line of development, the French grand opera. Alongside this cosmopolitan opera were the various national types, especially the French opéra comique and the German Singspiel, all taking on renewed life from about 1815 and destined for honorable growth during the remainder of the nineteenth century.

The two decades from 1790 to 1810, which saw the production of operas by Mozart and Beethoven at Vienna and by Cherubini, Spontini, and Méhul at Paris, were in Italy a time of relative stagnation—not in point of quantity, to be sure, but insofar as progress through acceptance of new ideas was concerned. The opera seria in Italy held conservatively to the old traditions until signs of change began to appear after 1800 with the works of (Johann) Simon Mayr (1763–1845).

Two of Mayr’s contemporaries were Ferdinando Paer (1771–1839) and Stefano Pavesi (1779–1850). Paer, one of the most talented Italians of this period, spent most of his productive life in Germany and France.1 From 1797 to 1801 he was director of the Kärntnertor Theater in Vienna; he then worked in Dresden for the next five years and finally moved to Paris, where in 1807 he served as Napoleon’s maître de chapelle and director of the Opéra-Comique. His Camilla, ossia Il sotterano, based on one of the “horror” operas of the French Revolution, was presented at Vienna in 1799; his Leonora (the same subject as Beethoven’s Fidelio), at Dresden in 1804; and an opéra comique, Le Maître de chapelle, at Paris in 1821. Pavesi, who in the latter part of his career succeeded Antonio Salieri as music director of the court opera in Vienna, produced some very successful operas in Italy.2 They included Ser Marcantonio (1810) at Milan and Fenella, ovvero La muta di Portici (1831) at Venice. Various minor masters in Italy supplied the demand for light entertainment with their comic operas, especially a characteristic one-act type, the farsa in un atto, an example of which is Adelina (1810) by Pietro Generali (1773–1832).

Mayr

Simon Mayr was a Bavarian who came to Italy at an early age. After studies at Venice, where his first opera (Saffo) was given in 1794, he settled at Bergamo.3 There he directed music in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore and founded, in 1805, a conservatory, where Donizetti was to receive his training. The most important of his operas (which numbered more than sixty) were Lodoïska (1800), Ginevra di Scozia (1801), Adelasia ed Aleramo (1807), Medea in Corinto (1813), and the heroic melodrama La rosa bianca e la rosa rossa (1813). Like Hasse and J. C. Bach, Mayr was a thoroughly Italianized German, but he was able to accomplish something that Jommelli had vainly attempted fifty years earlier: namely, to induce the Italian public to accept some changes in the forms and style of serious opera music. Like Traetta, Mayr drew often on French sources for his librettos. A case in point is his Il sacrifizio d’Ifigenia (1811; revised as Ifigenia in Aulide, 1820), in which the libretto follows closely that used for Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide, an opera that did not find acceptance in Italian theaters until the San Carlo performance of 1812. Use of French sources necessarily led him to include a considerable number of ensembles and choruses, a practice to which Mayr introduced one of his later librettists, Felice Romani, who carried it on in the librettos he afterward wrote for Mercadante, Bellini, and Donizetti.4 The use of the chorus—sometimes as a set piece, sometimes as part of the dramatic action, sometimes as background to a solo—was only one aspect of the generally greater flexibility of form that began to characterize Italian opera in the early nineteenth century.5

The old Metastasian opera seria had in principle permitted only three types of solo song—recitativo secco, recitativo accompangnato, and aria—and the three were kept separate. A soloist was seldom interrupted in the course of an aria; when the aria was concluded, the soloist exited, thereby bringing that scene to an end.6 Metastasio’s formal pattern, from which eighteenth-century composers of opera seria departed only exceptionally, gradually in nineteenth-century Italian opera came to be modified at will by a more or less thorough intermingling, in the same scene, of several soloists and different types of solo song (such as the cavatina-cabaletta for an entrance aria).7 This intermingling also extended to ensembles, choruses, and orchestral passages, the whole being organized on a broad musico-dramatic plan. Something of this kind, of course, had already taken place in the opera buffa ensemble finales in the eighteenth century, as well as in the operas of Gluck and his followers in France and Germany, but the idea penetrated only slowly to the more conservative opera seria in Italy. Mayr’s finales were usually divided into three sections: a slow concertato, a transition, and a stretta (tutti).

Another eventual new form in Italian opera of this period was the so-called scena ed aria for a single soloist, which consisted usually of a recitativo accompagnato followed by an aria, the whole in contrasting tempi and of a dramatic rather than lyrical or reflective character. Medea in Corinto exemplifies this well, for in this opera a declamatory style of recitative, accompanied by the orchestra, has entirely replaced the recitativo secco.

These formal developments were certainly foreshadowed in the works of Mayr, but their full realization was reserved for his successors. A more immediately important innovation of his was to make the orchestra richer in sonority and texture, and to use the woodwinds and brasses, not only in the overtures and set pieces but also in aria and ensemble accompaniments, to an extent hitherto unheard of in Italian opera. The harp also finds an important place in his orchestrations, as revealed in the romanza “Ov’è la bella virgine?” from his opera Alfredo il grande (Bergamo, 1819). The variety of instrumental color, and the sometimes sheerly overpowering sound of the Italian opera orchestra of the nineteenth century—as in Verdi’s Aida—go back ultimately to the example of Mayr.

Rossini

Italian composers of the early ottocento were soon to come under the domination of a young genius, Gioacchino Rossini, who began his meteoric career in 1810 with La cambiale di matrimonio, a one-act farsa staged at the Teatro San Moisè in Venice.8 There followed in rapid succession a variety of stage works, of which L’inganno felice (Venice, 1812), which is subtitled a farce, but in reality is more of a melodrama enlivened by some buffo scenes, and La pietra del paragone (Milan, 1812), a melodramma giocoso, were particularly outstanding. European fame began with Tancredi (Venice, 1813),9 an opera seria, and L’italiana in Algeri (Venice, 1813), an opera buffa, and was confirmed for all time by the worldwide success of Almaviva ossia L’inutile precauzione—better known by its later title, Il barbiere di Siviglia—in spite of the spectacular failure of its first performance at Rome in 1816.

As early as the summer of 1815, Rossini had signed a contract with the San Carlo and del Fondo theaters of Naples to provide two new works a year and to supervise productions of his own and other composers’ operas. The San Carlo offered composers one of the finest theaters in all Europe; it included a large orchestra, excellent singers, and an exceptional impresario. Rossini’s first opera for this theater was Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra, performed in October 1815. It was greeted rather coolly by the press, if for no other reason than Rossini was an outsider breaking into coveted territory. In November of that same year, a revised version of his L’italiana in Algeri was put into production at the Teatro dei Fiorentini. The following year Otello was produced at the Teatro del Fondo and thereafter was given frequently until it fell into oblivion after Verdi’s Otello came out in 1887. Although the libretto is an incredibly ridiculous caricature of Shakespeare, Rossini’s opera contains—especially in the third act—some of the most beautiful music he ever wrote.

Very few composers have equaled Rossini in rhythmic élan and sheer tunefulness. It is difficult to analyze the patent charm of these apparently effortless, seemingly artless Rossinian melodies that well forth in a ceaseless stream from his operas. Held within the frame of a persistent rhythmic motif (typically with dotted notes or in 6/8 meter), cast in short regular phrases of narrow range that are often immediately repeated, crystal clear in their harmonic implications, punctuated by occasional emphasized chromatic notes, and sometimes modulating in their second period to the rather remote mediant key instead of the familiar dominant, they seem to gather up in themselves the whole national genius for pure vocal melody as the elemental mode of musical expression. The celebrated cabaletta from Tancredi, “Di tanti palpiti,” is one such example (example 20.1). It became a hit tune of Rossini’s generation and is said to have been adopted as a favorite melody by the gondoliers of Venice. Such tunes require the lightest possible texture in the accompaniment, and they will not enter into contrapuntal combinations; in places where Rossini gives a melody to the orchestra, the voice is kept in the musical background, having perhaps detached interjections or a patter of words in monotone.

EXAMPLE 20.1 Aria “Di tanti palpiti,” Tancredi, Act I

There is some coloratura ornamentation of the melodic line in Rossini, but it is not excessive for the period. In all his operas after 1815, Rossini sought to curb the abuse of ornamentation by writing out the ornaments and cadenzas instead of leaving them to be improvised by the singers, as had been the former practice, and it is one of the minor ironies of musical history that he has sometime been accused of introducing excessive coloratura into opera, simply because his scores are in appearance more florid than those of his predecessors. Moreover, it must be remembered that in the opere serie of the nineteenth century, coloratura passages were not intended to be taken at high speed by a light voice but were to be sung rather slowly and expressively by a dramatic coloratura. Rossini was one of the last important composers to write castrato roles,10 and he was also one of the first to appreciate the value of contralto or mezzo-soprano voices in leading parts, as in L’italiana, Il barbiere, and Semiramide.

Already in Tancredi the basic elements of Rossini’s operatic style are firmly established. His arias are, for the most part, in two sections: the first is slow and the second (cabaletta) is fast. Here, too, are introduced an unusual number of large ensembles. Of course, his technique of ensemble writing is best exemplified in the comic operas, above all in Il barbiere. His ensembles are always lively, realistic, and full of contrasts; musically, they are kaleidoscopic rather than symphonic as in Mozart. Their principle of unity is mainly that of steadily mounting excitement, sometimes assisted by the famous Rossinian crescendo. This is a deceptively simple device (and one easily abused), consisting in many repetitions of a passage, each time at a higher pitch and with fuller orchestration; the classic example is the “Calunnia” aria in Il barbiere di Siviglia. In Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra and Otello, he took the further step of having all the recitatives accompanied by the orchestra.

Rossini’s treatment of the orchestra, though criticized by some of his contemporaries as noisy and obtrusive, seems to us now a model of clarity, an economy of means, and a deft choice of instrumental color. Always kept tactfully subordinate when accompanying solos, it comes into its own in the ensembles and especially in the overtures, many of which are still played today, detached from the operas for which they were originally written.

Rossini’s first opera of importance after Otello was La Cenerentola (Rome, 1817), a semi-comic treatment of the tale of Cinderella, abounding in melodies from the inexhaustible Rossinian treasure-house, an excellent specimen of that hedonistic manner described by Stendhal as “seldom sublime, but never tiresome.” An equally attractive work is La gazza ladra (Milan, 1817), a semiseria type of opera, with a libretto based upon an actual event: a young French peasant girl was convicted and hung for thefts that were later discovered to have been made by a thieving magpie. In the opera, the girl is spared the fatal blow, for on her way to the place of execution, a magpie’s nest is discovered with the stolen treasures. La gazza ladra is remembered especially for its overture.

Mosè in Egitto (Naples, 1818), “a sacred story of tragic impact,” is a biblical drama that would have been appropriate to bring to the stage during Lent, even though the narrative from the Hebrew Scriptures is enlivened with a love story. Especially notable is the stirring preghiera con coro near the end of Act III. In its extensively revised version given at Paris in 1827 as Moïse et Pharaon, this opera—with its generally elevated style and many choral scenes—clearly foreshadows the more famous Guillaume Tell of 1829. La donna del lago (Naples, 1819) has a romantic libretto adapted from Walter Scott’s poem, The Lady of the Lake, but the few romantic touches in the music itself are evidently only skin deep.11 The last opera for Italy was Semiramide (Venice, 1823), a melodramma tragico, with a huge score, including one of Rossini’s finest overtures (built for the most part on themes from the opera itself), many ensembles and large choruses, and arias in a great variety of forms with much coloratura—all in all, a good illustration of the progress of Italian opera since the beginning of the century. Semiramide also has a military band on stage, a novel feature that was frequently imitated by later composers.12

After one short season in London, Rossini took up residence at Paris in 1824, where he remained for most of his life. Here he presented the French version of Mosé in Egitto (mentioned above);13 Le Siège de Corinthe (1826), created from an extensively revised form of his Italian opera Maometto II (1820); Il viaggio à Reims (1825), performed to celebrate the coronation of Charles X; and Le Comte Ory (1828), in which music from Il viaggio à Reims reappears. As Moïse and Le Siège de Corinthe were important steps toward the formation of French grand opera, so Le Comte Ory, an original and sparkling opéra comique, demonstrated Rossini’s mastery of the French comic style and in turn exercised a strong influence on the later course of French opéra comique and operetta (see chapter nineteen). With Guillaume Tell, Rossini reached the climax of both his art and his fame.14 He was then thirty-seven. Whether from distrust of his own powers, disgust at the new direction of public taste as evinced by the rage for Meyerbeer, or a combination of these and other motifs, he wrote no more operas—though the Stabat Mater of 1842 showed that he had not forgotten how to be dramatic in music. But he had carried Italian opera, as Beethoven had carried the symphony, through the transition from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century, and he had furnished in II barbiere an immortal masterpiece of opera buffa and in Guillaume Tell one of the finest examples of grand opera of the early nineteenth century.15

Donizetti

The course of Italian opera from Rossini to Verdi is summed up in the work of three composers: Gaetano Donizetti (1797–1848), Vincenzo Bellini (1801–35), and Saverio Mercadante (1795–1870). Donizetti was a composer of almost incredible fecundity, whose operas (of which there are more than seventy) make up only a fraction of his total musical output.16 During his formative years in Bergamo, Donizetti’s musical training was guided by Mayr, maestro di cappella at Santa Maria Maggiore, who placed great faith in his young pupil’s abilities as a composer. With Mayr’s encouragement, Donizetti left his native city in 1815 and went to Bologna to study with Padre Mattei. While there, Donizetti composed a one-act comedy, Il Pigmalione (1816). Although this was his first opera, it was not performed in his lifetime and therefore is not the work with which he made his debut as an opera composer.17 That distinction belongs to Enrico di Borgogna, an opera semiseria, staged at Venice in 1818. For the next twelve years, opera upon opera poured forth from Donizetti’s pen. Some were very successful opere buffe, such as L’ajo nell’imbarazzo. Others were of a more serious nature, as represented by two operas that had their premieres in Naples: La zingara (1822), an opera semiseria with spoken dialogue, and Il castello di Kenilworth (1829), an opera seria derived from a Walter Scott novel about Tudor England.18 Although the twenty or more operas that were staged prior to 1830 are little known today, their significance should not be underestimated, for they provided a wellspring from which Donizetti drew musical excerpts for inclusion in operas that appeared after that date.19

The work that has traditionally been singled out as establishing Donizetti as a leading composer of nineteenth-century Italian opera is the two-act romantic tragedy Anna Bolena (Milan, 1830), an opera in which the vocal melodies have a “broad, elastic, and freely soaring quality.”20 His success with this opera stemmed largely from the excellent libretto Felice Romani created for him. Especially memorable is the final “mad scene”: Anna—condemned to die—has lost her mind and imagines she is preparing, not for her death, but for her wedding day. Surrounded by her attendants, she wonders why they greet her with sadness and weeping. It also stemmed from Donizetti’s interjection of a more personal style into the score, a style that showed signs of moving away from some of the Rossinian conventions of operatic design.21 Anna Bolena was followed two years later by the ever popular romantic comedy L’elisir d’amore (1832), a work that has remained in the repertoire to the present day. The idyllic, sentimental charm of the familiar aria “Una furtiva lagrima” in this opera is all the more effective by contrast with the prevailing lighthearted character of the rest of the music.

Lucrezia Borgia (1833) and Lucia di Lammermoor (1835) may be taken as typical of the more violent sort of Italian operas of this period. Lucrezia was adapted from Victor Hugo’s drama and Lucia from Scott’s novel. Both are full of melodramatic situations well adapted to Donizetti’s style, and it is undeniable that his music at its best has a primitive dramatic power even when its substance is only rudimentary, as in the closing scene of Lucrezia. The score of Lucia is worked out with more critical care and its effects are less often marred by trivial melodic episodes; the famous sextet in Act II and the “mad scene” in Act III are excellent examples of Donizetti’s art. He had a Midas gift of turning everything into the kind of melody that people could remember and sing, or at least recognize when they heard it sung the next day in the streets. His tunes have a robust swing, with catchy rhythms reinforced by frequent sforzandos on the off beats.

A common musical form for arias (and sometimes duets) in Donizetti, as in all Italian opera of his time and later in the nineteenth century, is the cavatina or cantabile, an expressive, melodious slow movement, followed usually by a cabaletta, a fiery allegro with virtuoso vocal effects and a climactic close. Recitative dialogue and even phrases for the chorus might intervene between the two parts of such an aria, bringing it into connection with the ongoing dramatic action.22 Frequent ensembles and choruses were the rule in operas of this era; Donizetti keeps the chorus on stage a great deal of the time, not always for dramatic reasons but sometimes simply to add volume and color to the musical background. Another common device, heard sometimes in Spontini and increasingly often in Rossini, Donizetti, and later composers, is the declaiming of a salient melodic phrase in unison or octaves by both singers of a duet or by a whole ensemble or chorus—an electrifying effect at high moments in a scene.

Like Rossini and Bellini before him, Donizetti was invited to compose for the Paris theaters. Of his five operas originally written to French texts, the most important were La Fille du régiment (1840), an opéra comique, and the four-act grand opera La Favorite (1840). The former, still very popular, shows traces of both Rossini and Boieldieu in some of its melodies and rhythms. La Favorite is uneven, though the third act is very fine both musically and dramatically, the whole representing a composite of borrowed and newly composed music.23

Roberto Devereux, ossia Il conte di Essex (1837), a tragedia lirica in three acts, first staged at Naples, became one of Donizetti’s most widely performed operas throughout the greater part of the nineteenth century.24 The libretto derives in part from a text Romani wrote four years earlier for Mercadante’s Il conte d’Essex. Central to the plot is the conflict that develops in Queen Elizabeth’s life between her powers as a ruler and her vulnerability as a woman. Her interest in Devereux is expressed in “Ah, ritorna qual ti spero,” a cabaletta sung while she awaits his arrival.25 Roberto, however, does not respond enthusiastically to her greeting and the queen suspects that he may be in love with someone else. A scarf belonging to Sara, Nottingham’s wife, is found with Roberto; when he is asked to confess whose scarf it is, he refuses, claiming he would rather accept death than reveal her name. And death is indeed his fate, for the queen has him arrested and killed before Sara can come forth with evidence—in this case, a ring—to prove his innocence.

The queen’s rage is unleashed in several of her numbers, but nowhere more effectively than when she signs the death warrant in Act II and sings “Va, la morte sul capo ti pende,” with its extremely disjunct and wide-ranging vocal part (example 20.2). A far different kind of dramatic intensity is generated in this same act when the discovery of the scarf initiates three different reactions from Elizabeth, Roberto, and Nottingham, which they express with ever increasing tension in the trio “Alma infida, ingrato core.”

Donizetti’s Don Pasquale (Paris, 1843) is an opera buffa worthy to be named, together with Rossini’s II barbiere di Siviglia and Verdi’s Falstaff, among the masterpieces of nineteenth-century comic opera. The libretto, adapted by Giovanni Ruffini from an earlier text by Anelo Anelli (both men had at one time been political prisoners), was created within the Paris circle of Italian political exiles. Beneath the veneer of the commedia dell’arte plot, in which an amorous old man is outwitted, simmers a conflict between old conservative ways and revolutionary new ones. That this conflict may be reconciled, thereby averting a tragic outcome, is revealed in Donizetti’s score.

The comedy of Don Pasquale is delightful in itself; that it is also touched with deeper feeling and thus lifted above the level of mere amusement is particularly evident in the duet of Norma and Don Pasquale in Act III, a poignant juxtaposition of buffoonery and pathos. The recitatives in this opera are patterned after a secco style but are accompanied by sustained strings instead of a keyboard instrument. The chorus is limited to brief appearances in Act III, a departure from the more extensive role it usually plays in comic opera; it introduces the first scene, accompanies the offstage serenade sung by Ernesto in the second scene, and reappears briefly to support the principals in the final ensemble.

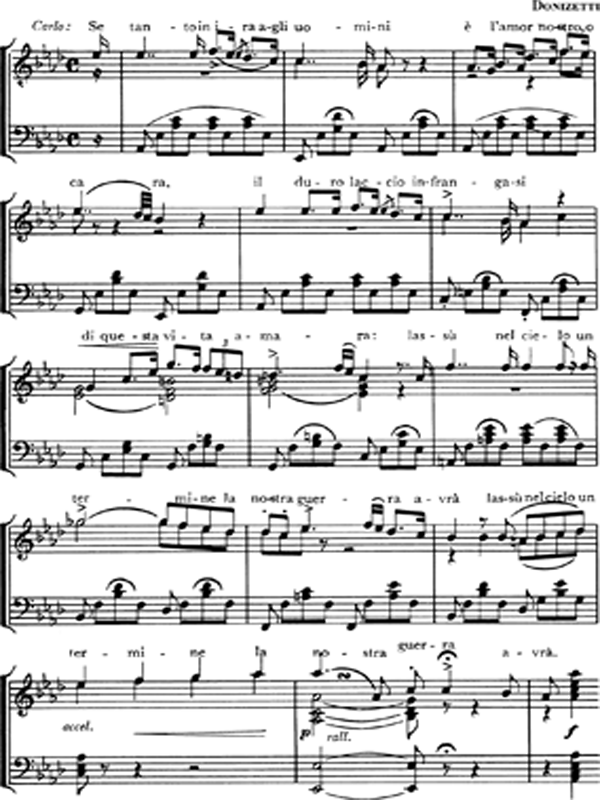

EXAMPLE 20.2 Roberto Devereux, Act II

Robert Devereux—Donizetti. © Kalmus Publications/Belwin Mills Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Used by permission of Warner Bros. Publications U.S., Inc., Miami, Fla. 33014.

In 1843 Donizetti went to Vienna to conduct productions of Italian opera at the Kärntnertor Theater. In addition to those of other composers for the stage, among them Verdi’s Nabucco, he prepared his own operas for performances, including two written especially for Vienna, Linda di Chamounix (1842) and Maria di Rohan (1843). Linda, the better of the two, is an opera semiseria with mingled comic, romantic, and pathetic scenes, matched with unaffectedly expressive music (example 20.3). While in Vienna, he also began to compose Don Sébastien, a five-act grand opera on a libretto by Scribe. This, his last complete opera, was performed at the Paris Opéra in 1845. Two years later it was presented in a German version at Vienna, followed in 1847 by an Italian version for La Scala at Milan. Although Donizetti considered this his most important work, Don Sébastien was unable to hold the interest of opera audiences beyond the end of the nineteenth century.

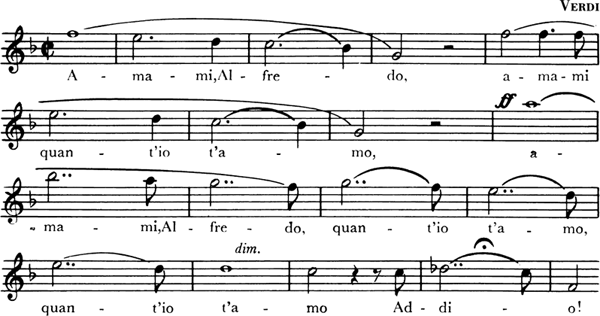

EXAMPLE 20.3 Linda di Chamounix, Act II

Bellini

While the music of Donizetti’s serious operas represents the heartier, more extrovert qualities of Romanticism, that of Bellini’s is marked by the more inward and lyrical qualities. Bellini’s principal early operas were Il pirata (1827) and La straniera (1829). His European fame spread quickly with La sonnambula and Norma, both of them produced at Milan in 1831.26 Beatrice di Tenda (1833), the first of his operas to be published in full score, was written for Venice and his last opera, I Puritani di Scozia, was written for Paris and performed there in 1835.27

When Bellini died at the age of thirty-four, he had written only ten operas. At the same age, Rossini had written thirty-four operas and Donizetti, thirty-five. One reason for this difference in the rate of production is evident from a glance at the autograph score of Norma, which is full of cancellations and emendations. Bellini worked more slowly because he was more particular about his librettos and more fully dedicated to an ideal union of words and music. He had a loyal collaborator in Felice Romani, who furnished the librettos for all his important operas except I Puritani. One consequence of Bellini’s sensitiveness to the text is that his recitative not only is more musical and flexible than that of his contemporaries but also, at the right dramatic moments, rises to extraordinary intensity of expression, as in the marvelous scene that opens the second act of Norma.

Bellini’s melodies are of incomparable elegance, evolving in long lines usually without much obvious repetition of motifs but sometimes with subtle irregularities in the length of the phrases. The elegiac, melancholy character of some of Bellini’s music (example 20.4) has often been compared to Chopin’s, and indeed the two composers are similar not only in this respect but also in that both require a sympathetic interpreter to do them justice.28 It must never be forgotten, in dealing with Italian opera of this period, that everything depends on the singers. Composers most often wrote their parts with certain singers in mind, and many a melody that looks banal enough on the page becomes luminous with meaning when sung by one who understands the Italian bel canto and the traditions of this type of opera.29 This is especially true of Bellini, in whose works the whole drama is concentrated in melody to a degree surpassing even Rossini, Donizetti, and Verdi. Yet Bellini’s harmony, while never calling attention to itself, is considerably more varied and interesting than that of Donizetti, and his treatment of the orchestra, particularly in the later works, is by no means negligible.

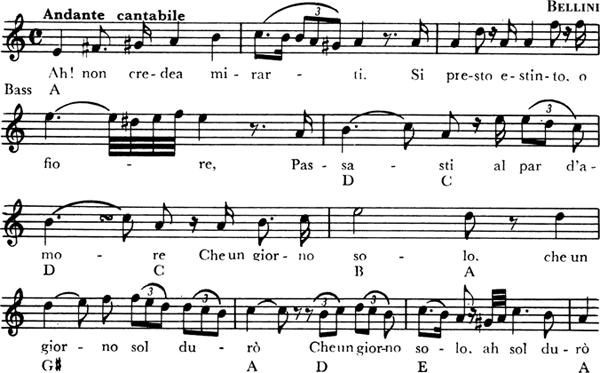

EXAMPLE 20.4 La sonnambula, Act II, finale

The principal place of instrumental music (aside from the overture) in the operas of these two composers is in the introduction to a scena; comparison of any such orchestral passages in Donizetti with the introduction to the first act of Bellini’s Norma will strikingly demonstrate the latter’s superiority. In the accompaniments, Bellini’s orchestra is, of course, completely subordinated to the singer. Like all his contemporaries, he frequently gives the melody to both voice and instruments, ornamented for one and plain for the other; or he may realize the melody in unbroken continuity in the orchestra while the voice joins in with fragmentary phrases—but it is always one and the same melody. Another device, found equally in Rossini, Donizetti, and Verdi, is the announcement of an aria by playing the first phrase or two in the orchestra before the singer begins. This has a superficial resemblance to the “false start” or “Devisenaria” of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century opera arias, where the voice sings an opening phrase and then breaks off to begin again, but the difference between the two procedures is significant: in Scarlatti or Handel, the beginning is like a sonorously proclaimed title; in Donizetti or Bellini, it is a seductive appeal for the audience’s attention. It also has the practical purpose of giving the singer time to become disengaged from the business of the preceding recitative and come downstage into position for his or her aria.

With Bellini, as with Donizetti, the chorus is an important factor. It is most conspicuous in I Puritani, where Bellini was adapting himself to grand opera on the scale required at Paris, but it is also used effectively in Norma, as in the opening scene—a chorus was practically obligatory in the first scene of an opera at this time—and in the cavatina “Casta diva,” where the chorus forms part of the quiet musical background for Norma’s solo. A few choral scenes in Bellini’s other operas, notably those in the second act of La sonnambula, suggest in some inexplicable way the feeling of Greek drama or the early Florentine favola in musica.

Mercadante

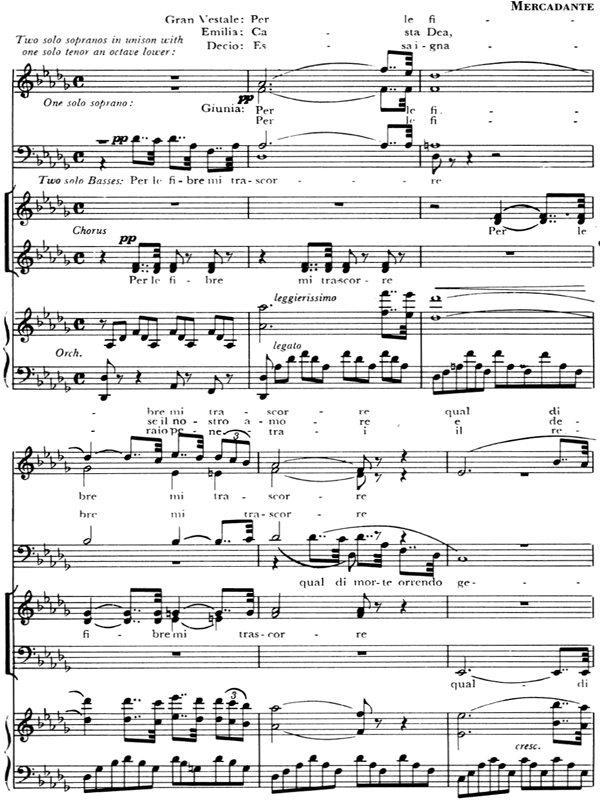

One of the most popular composers in Italy in the 1820s and 1830s was Saverio Mercadante (1795–1870), a Neapolitan and pupil of Zingarelli.30 Mercadante can perhaps be characterized as a Janus-faced composer; his works written before 1837, including the successful Elsia e Claudio (Milan, 1821), an opera semiseria, and I Normanni a Parigi (Turin, 1832), are stylistically related to the Italian operas of his contemporaries, whereas those written after 1837, the so-called reform operas, point toward the mature style of Verdi. The pivotal work is Il giuramento (1837), composed under the influence of Mercadante’s contact with French grand opera during a sojourn in Paris. It initiates some of the “reforms” that Mercadante described in his oft-quoted letter addressed to Florimo, librarian at the Naples Conservatory, where Mercadante served as director from 1840 until his death. Further manifestation of these reforms can be found in what many consider Mercadante’s best operas, Il bravo (Milan, 1839) and La vestale (Naples, 1840).31 Example 20.5, from the latter work, illustrates the full-bodied, rich texture and lusty melodic sweep of his style, as well as another new trait in nineteenth-century Italian opera—the frequent use of the more remote flat keys.

None of the changes in Italian opera from 1800 to 1840 had overturned the foundations already established. Starting from the axiom that music should prevail over drama, the Italians had always held to two principles of opera: the solo voice, and therefore melody, as the essential vehicle of musical expression; and division into distinct numbers, mainly recitatives and arias, as the governing rule of the musical structure. Beginning with Mayr and Rossini, composers in the nineteenth century made the orchestra more colorful and gave it more to do, but they never questioned the supremacy of melody in the total musical scheme; rather, they tried to make the melody more expressive and thus to bring it, with the aid of harmony, rhythm, and instrumental color, into closer relation with the drama. Similarly, while loosening the formal structure of opera by giving prominence to ensembles and choruses, they never renounced the general principle of separate numbers; rather, they made the numbers longer and more diversified within themselves, combining soloists and chorus, and replacing the three-part da capo aria with the cantabile-mezzo-cabaletta, or the old recitative-aria combination with the more ample and varied scena ed aria. The first impulse toward the expansion of the orchestra came from Germany through (Johann) Simon Mayr; the model for the greater flexibility of form was French opera, but French opera as developed mainly by foreigners, resident at Paris—Gluck, Cherubini, Spontini, Paer, Rossini, Meyerbeer—who had brought into French opera certain traits from their own countries. Thus opera in Italy, which at the turn of the century had been a rather local affair, gradually began to assume a more cosmopolitan character, though without sacrifice of its individuality. This process of adjustment, already well advanced in Donizetti and Bellini, was to be carried to its final stage by Verdi.

EXAMPLE 20.5 La vestale, Act II, finale

Verdi

Donizetti’s last important work, Don Pasquale, was produced in 1843. For the next fifty years, the history of Italian opera is dominated by a single figure, that of Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901). Verdi began where his countrymen left off;32 he brought the older Italian opera to its greatest height, and finally in his own person embodied the change from that style to the more subtle and sophisticated manner of the later nineteenth century. An Italian of the Italians, faithful to their instincts, a clear-sighted and indomitable artist, he maintained almost single-handedly the cause of Italian opera against the tide of enthusiasm for Wagner and in the end vindicated the tradition of Scarlatti and Rossini alongside that of Keiser and Weber.33 The old struggle between Latin and German, southern and northern music in opera—the singer against the orchestra, melody against polyphony, simplicity against complexity—was incarnate in the nineteenth century in the works of Verdi and Wagner, who represented the two ideals in all their irreconcilable perfection.

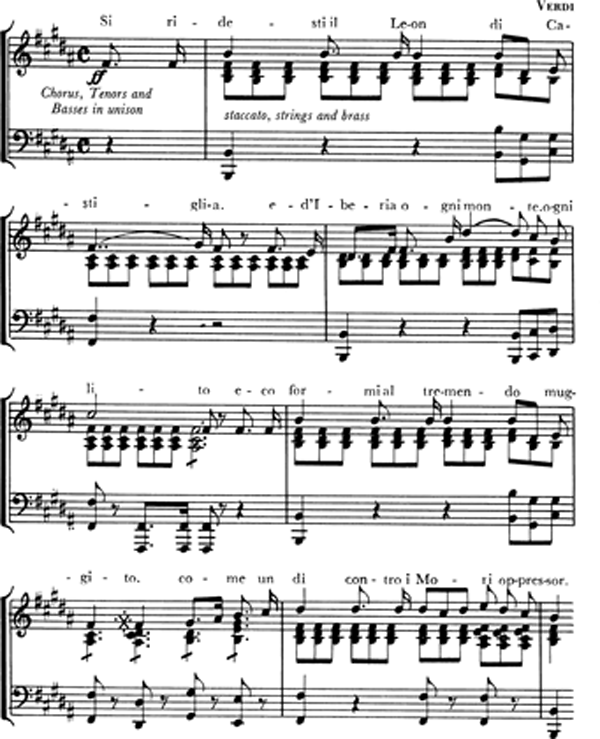

Verdi’s first triumph was achieved at Milan in 1842 with the biblical opera Nabucodonosor (generally known as Nabucco), followed a year later by I Lombardi alla prima crociata—both works, with their large choruses and melodramatic situations, recall Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable.34 His international fame began with Ernani (1844), on a libretto arranged by Francesco Piave from Victor Hugo’s drama.35 The music of these early operas showed Verdi as a composer with a sure feeling for the theater and a melodic gift in which the facility of Donizetti was combined with greater breadth of phrase and ferocious energy of expression (example 20.6).

Verdi was immensely popular in Italy because he brought to the accepted forms and idiom of opera just that touch of dynamic individuality that was needed. But there was a further reason only indirectly connected with the music itself. Italy during the Risorgimento—the Italian nationalist movement (c. 1815–70)—was seething with revolution, and Verdi’s early operas came to play an important part in the patriotic movements of the 1840s and 1850s.36 Though their scenes and characters ostensibly had no connection with contemporary events, the librettos were filled with conspiracies, political assassinations, appeals to liberty, and exhortations against tyranny, all of which were readily understood in the intended sense by sympathetic audiences. Examples include “Va, pensiero,” a chorus in Nabucco (Part III) sung by the Hebrew slaves, with the line “O mia patria, si bella e perduta” (O my homeland, so beautiful and lost), and a chorus in Macbeth sung by Scottish exiles, with the line “O patria oppresa” (O oppressed homeland). In addition to Nabucco and Macbeth, several other operas—I Lombardi, Ernani, I due Foscari, Giovanna d’Arco, Atilla, and the so-called occasional opera La battaglia di Legnano—gave rise to fervent demonstrations and made Verdi’s name a rallying cry for Italian patriots. Even Rigoletto, based on a very good adaptation by Piave of Victor Hugo’s Le Roi s’amuse, was attacked by the censors, and the names of historical characters (especially King Frances I of France) as well as several other details had to be changed before production was permitted.

EXAMPLE 20.6 Ernani, Act III

A similar situation arose with regard to Un ballo in maschera; the authorities in Naples insisted on transforming the original Gustavus III of Sweden into an imaginary Count of Warwick (Riccardo), repositioning this fantastic and bloody melodrama from the eighteenth to the seventeenth century, and changing the location from Sweden to a city in the United States (Boston).37 It was during the popular demonstrations attending the preparation of this opera that crowds in front of his hotel shouted “Viva Verdi”—a cry of double meaning, for the letters of the composer’s name formed the initials of “Vittorio Emanuele Re D’Italia,” and thus he came to be identified with the cause of Italian national unity.

Verdi’s principal librettists were Temistocle Solera (Oberto, Nabucco, I Lombardi, Giovanna d’Arco, Attila), Francesco Piave (Ernani, I due Foscari, Macbeth, Il corsaro, Stiffelio, Rigoletto, La traviata, Aroldo, Simon Boccanegra, La forza del destino), and Salvatore Cammarano (Luisa Miller, Il trovatore). The literary sources of the librettos were various: from Schiller came Giovanna d’Arco, Luisa Miller (Kabale und Liebe), I masnadieri (Die Räuber), and Don Carlos; from Victor Hugo, Ernani and Rigoletto; from Dumas the Younger, La traviata (La Dame aux camelias); from Scribe, Les Vêpres siciliennes and Un ballo di maschera; from Byron, I due Foscari and Il corsaro; from the Spanish dramatist Gutierrez came Il trovatore and Simon Boccanegra; and from another Spaniard, the Duke of Rivas, La forza del destino.38 Schiller was one of Verdi’s favorite authors,39 the other being Shakespeare, from whose writings he drew Macbeth, Otello, and Falstaff (the last two arranged by Arrigo Boito), as well as the projected, but never completed, King Lear and Hamlet.

(PHOTO, © 1993 KUVASUOMi KY MATTI KOLHO. COURTESY OF THE SAVONLINNA OPERA FESTIVAL)

With the exception of Falstaff and one early unsuccessful work, the plots of Verdi’s operas are serious, gloomy, and violent; the earlier works especially are typical examples of the blood-and-thunder romantic melodrama, marked by situations of strong passion in rapid succession, giving vivid contrasts and a theatrically effective sweep to the action, however questionable the details may be from a dramatist’s viewpoint. Influences upon this type of plot may be traced through Meyerbeer in France and through Mayr, Mercadante, and Donizetti in Italy; but whereas in the French operas horror and violence serve to reinforce the humanitarian message, now they are being used for their own sake. The obscurity of many of Verdi’s plots is due largely to the extreme condensation upon which the composer insisted, and often a careful reading of the libretto is necessary in order to understand the action. Whatever may be thought of the subject matter, it cannot be denied that it always offered the kind of opportunity Verdi needed to exercise his special gifts.

With the production of Il trovatore and La traviata in 1853, a climax of Verdi’s work in the purely Italian opera was reached. We may therefore pause here to indicate some of the essential characteristics of the style by which Verdi was known and loved in his own land. The essence of Verdi’s early style is a certain primitive directness, an uninhibited vigor and naturalness of utterance. This results often in melodies of apparent triviality, which are nevertheless patently sincere and almost invariably appropriate to the dramatic situation. His effects are always obtained by means of voices.40 His orchestration grew constantly more expert and original from the earliest to the latest operas,41 but the orchestra never has the symphonic significance or the polyphonic texture of Wagner’s. The overtures (especially those for Luisa Miller, Nabucco, Les Vêpres siciliennes) are important, but many of his operas begin with only a short orchestral prelude, or no prelude at all (Otello, Falstaff). The ballet music is seldom distinguished, and most of the instrumental music for ball scenes, marches, and the like (often performed by a military band on stage) lacks individuality. Nature painting and the depiction of the fantastic, so important in contemporary German Romantic opera, find little place in Verdi.42 His interest is in the expression of human passions in song, to which all else is subordinated, and through that medium he creates a musical structure of sensuous beauty and emotional power, basically simple and uncomplicated by philosophical theories, with an appeal so profound, so elemental, that it can hardly be conveyed or even intelligibly discussed in any other language than that of music itself.

The heart of the melodramatic, romantic Verdi is to be found in three works: Ernani, Rigoletto, and II trovatore. The last is particularly rich in traits that mark the composer’s works in this period: the roaring unison of the “Anvil Chorus”; the unbelievable contrast of moods in the “miserere” scene; the nostalgic sentiment of Azucena’s “Ai nostri monti”; Manrico’s lusty bravura aria “Di quella pira”—these and other melodies from this opera are so well known that citation or comment is superfluous. Rigoletto, almost equally agonizing in its plot and situations, is a more unified whole and superior in character delineation; its famous quartet is one of the finest serious dramatic ensembles in all opera.

In contrast to the naked brutality of Rigoletto, Il trovatore, and some of the other early works, La traviata is a refined drawing-room tragedy that concerns ordinary people, contemporary with the time of its creation; its more restrained, almost intimate, musical style had already been foreshadowed in Luisa Miller (1849). Several details in La traviata are significant in the light of Verdi’s future development. The orchestra is of relatively greater dramatic importance: in the ballroom scene of Act I, it furnishes a continuous background of dance music against which a conversation is carried on;43 the opening strain of the prelude, with its pathetic minor harmonies in the divided violins, recurs most effectively at the beginning of Act III to set the mood for the closing scenes of the opera. Then, too, there is an occasional vocal phrase that demonstrates a greater freedom in the melodic line, a beginning of emancipation from the usually all-too-regular patterns of the early Verdi (example 20.7).44 The entire scene, which culminates in this beautiful passage, is a fine example of moving dramatic declamation.

Several of Verdi’s operas make systematic use of recurring themes. Mere repetition of previously heard themes was not at all uncommon in operas of the first half of the nineteenth century, and instances may also be found in Mozart, Grétry, and Monteverdi. Verdi’s procedure should not be confused either with the simple earlier practice or with Wagner’s system of leitmotifs (to be discussed in chapter twenty-two); it consists rather in introducing a musical phrase already associated with a certain dramatic situation into a later situation with the purpose of underlining the similarity—and also perhaps, by implication, the contrast—between the two.45 In Ernani the motif of the pledge and in Rigoletto that of Monterone’s curse recur at appropriate moments in the opera; I due Foscari offers further examples, as do also Ii trovatore and especially La traviata. The use of recurring themes in Aida and Otello is thus only a continuation and refinement of Verdi’s earlier practice and of course has nothing to do with any alleged Wagnerian influence.

EXAMPLE 20.7 La traviata, Act II

With regard to the ensembles in Verdi, one can do little but refer the reader to the scores. Telling declamation, perfect dramatic timing, and an infallible sense of climax mark them all; perhaps the most remarkable feature is the composer’s endless inventiveness in sound combinations, his reveling in sweet and powerful sonorities. The sotto voce ensembles, such as those in the Paris version of Macbeth, have an indescribably mysterious, suggestive quality.

Verdi was not a composer who studied the scores of his rivals with a view to excelling them on their own ground; secure in his own musical and dramatic instincts, he pointedly avoided too close acquaintance with other composers’ music. Almost the only specific non-Italian influence that can be traced in his works is that of Meyerbeer, for whom he had considerable admiration. Il trovatore, in its bewildering array of incidents and musical effects, is very reminiscent of Meyerbeer, and the character of Azucena, the gypsy mother, has often been compared to that of Fidès, the mother of John of Leyden in Meyerbeer’s Prophète.

The magic attraction of Paris for Italian composers was still strong, and it is not surprising that Verdi should have aspired, like Cherubini, Spontini, Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti before him, to the satisfaction of a Paris success. He made some essays in the grand opera style in his early career, especially in Giovanna d’Arco. I Lombardi had been adapted and successfully performed at Paris in 1847, under the title Jerusalem. An even more thorough adoption of grand opera style occurred in 1855, when Verdi composed Les Vêpres siciliennes, using Scribe’s five-act libretto based upon the historical subject of the massacre of the French by the Sicilians in 1282. The story reads almost like a travesty of all the devices for which Verdi’s operas were famous; the music, with the exception of the overture, is in general inferior to Verdi’s usual style.

A greater success was obtained with Don Carlos, another work along grand opera lines, excessively long in the original 1867 version for Paris, but containing many fine individual numbers, such as the duet in Act II, “Dieu, tu semas dans nos âmes.”46 A particularly intense scene occurs at the opening of Act IV; here the superior intellect and uncompromising will of the old Grand Inquisitor is pitted against the resolute will of the king, vividly dramatizing the conflict between church and state. Although based upon Schiller’s dramatic poem, Verdi’s Don Carlos is a faint reflection of the eighteenth-century playwright’s original work, which had its world premiere in 1787. The libretto in French, prepared for Verdi by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, retains the principal characters—the elderly king, his virtuous wife, the king’s son Don Carlos, the Marquis of Posa, and the king’s mistress. The action centers on Don Carlos’s attempts to win the love of the queen (the king’s third wife) and on Posa’s plan to have Don Carlos support his efforts to win religious independence for the Low Countries, which were subjected to Spanish rule. Not satisfied with the way Schiller’s play begins, the librettists created a new opening scene; they also eliminated many of the lesser characters and revised various aspects of Schiller’s text, including the final scene. After the Paris premiere, Don Carlos was shortened from five to four acts for an 1884 Italian production in Milan. Two years later, Verdi again revised the score, reinstating the opening act that was previously eliminated along with other changes.

Operas of the period between La traviata and Aida include Simon Boccanegra, Un ballo in maschera, and Il forza del destino. Simon Boccanegra failed at its first appearance (1857) but was successful in a thoroughly revised version in 1881.47 Un ballo in maschera (1859) is remarkable both for certain experimental details in the instrumental writing (for example, the canonic treatment of one of the themes in the prelude) and for the beginning of Verdi’s later buffo style in the music given to Oscar, the page—a new idiom that is carried through the role of Fran Melitone in La forza del destino and reaches fruition in the pages of Falstaff. In Un ballo comedy is allowed to pervade even the most serious of scenes, thereby creating a score in which the comic and the tragic are blended and balanced. Also of particular interest is the exceptionally long and well-wrought duet sung by Riccardo and Amelia at the midpoint of Act II. La forza del destino, first staged at St. Petersburg in 1862, is a somber melodrama distinguished by a score in which we can trace still further the progress of Verdi toward that long, breathed, broadly rhythmed, infinitely expressive melody that we associate with the composer’s later style.

Early in 1870 Verdi accepted a commission to write a work for a new opera house at Cairo, to be produced as a festival performance in connection with the opening of the Suez Canal, and this resulted in Aida. The plot, based on a story by the French Egyptologist François Mariette, was sketched by Verdi and his friend Camille du Locle and put into poetic shape by Antonio Ghislanzoni. Ghislanzoni’s share really amounted to little more than turning Verdi’s ideas into verse, for the composer himself dictated the layout of scenes and even details of the dialogue, on the basis of his long experience with the theater.48 The libretto is even more effective theatrically than the librettos of Verdi’s earlier operas, since the details of the plot are clearer, the psychology of the characters more lifelike, and the action simpler and more straightforward. The first performance at Cairo in December 1871 was followed two months later by an equally successful one at La Scala in Milan.

Aida was in every respect the culmination of Verdi’s art up to that time, uniting the melodic exuberance, the warmth and color of the Italians with the pageants, ballets, and choruses of grand opera. Aida is Italian opera made heroic, grand opera imbued with true human passion, a fusion of two great nineteenth-century styles. Verdi here surpassed himself in his own domain: he had never written better solo arias than Radames’s “Celeste Aida” or Aida’s soliloquy “Ritorna vincitor”; the finale of Act II exceeds in splendor anything from the earlier operas; and the closing scene is a climax in the expression of that mood of tragic poignancy of which Verdi had always been a master. But beyond such matters as these are still more significant advances. Music and drama are more tightly interwoven, and this in turn affects the form as a whole; for while Aida is still a number opera, the score possesses more continuity than any of Verdi’s previous works. This is due in part, but not entirely, to two devices: (1) the use of recurring themes, more extensively and systematically than in any of the other operas, and (2) a pervasive, subtle exoticism. The latter is not the product of borrowed Egyptian native tunes but of Verdi’s own sensitiveness to color, expressed not only in melodies of modal turn, with chromatic intervals, but also in original harmonies and many details of instrumentation (see, for example, the introduction to Act III). Even the ballet music, usually rather perfunctory with Verdi, here has a richness of harmony and scoring, a freshness of melodic and rhythmic invention, which make it of equal interest with the rest of the opera.

In a word, the production of Aida saw Verdi, then aged fifty-eight, at the summit of his career—wealthy, successful, the acknowledged master of Italian opera, the idol of his countrymen, a world-famous figure. Had he never written another note, his high position in the history of opera would have been secure. After the triumphal reception of the Requiem (1874), he himself felt that his active days as a composer were over. A mood of depression gripped him in the years around 1880, due to both political and musical conditions in Italy at the time. Wagnerian music and Wagnerian philosophy were threatening the very foundations of Italian art, and while Verdi was far from feeling envious of Wagner, he was alarmed at what he felt was a false course on the part of many of his countrymen. In 1889 he wrote: “Our young Italians are not patriots. If the Germans, basing themselves on Bach, have culminated in Wagner, they act like good Germans, and it is well. But we, the descendants of Palestrina, commit a musical crime in imitating Wagner, and what we are doing is useless, not to say harmful.”49 Although Verdi sensed the “irrepressible conflict” between German and Italian opera, he hesitated long before committing himself to battle. He was weary, haunted by distrust of his own powers, and apprehensive of public failure. For sixteen years after Aida, no new opera came from his pen. It was not until 1887, when the composer was more than seventy years old, that Otello appeared, the greatest Italian tragic opera of the nineteenth century and the triumphant answer of Italian art to the threat of German domination.

Verdi decided to counter the Nordic myth as operatic subject matter with a return to purely human drama. He chose Shakespeare’s Otello and Falstaff as subjects for his librettos, the arrangement of which was the work of Boito, to whose skill and devotion much of the credit for both works must be given. Boito’s adaptations of Shakespeare are excellent. In Otello, especially, the delicate problem of shortening the poetry so as to leave scope for the development of the music is handled with skill, and the action of the original is followed closely. Boito altered a few details and added only the verses of Iago’s “Credo” in Act II.50

As to the music of Otello, we must beware of regarding it as a complete break with Verdi’s earlier style. It is rather the culminating point of an evolution. Not all the older practices are abandoned. There are precedents for: the storm at the opening of Act I (compare Rigoletto); the drinking song and chorus in the same act; the serenade in the garden scene of Act II, with its accompaniment of bagpipes, mandolins, and guitars; the duets, conventional enough in their placing at the end of Acts I and II; the ensembles, especially the magnificent one at the end of Act III; and the superb theatrical close of this act, with Iago’s melodramatic “Ecco il Leone!” which is in the best tradition of Italian opera. There are recitatives and arias—for example, Iago’s “Credo,” Otello’s “Ora e per sempre addio!” Desdemona’s “Salce” and “Ave Maria.” But all these forms and styles in Otello have a finish and perfection, a close connection with the drama, surpassing anything previous. Moreover, certain procedures are definitely new with this work. Perhaps the most obvious of these is the continuity of the music throughout each act—that is, the absence of separate numbers, as in the earlier operas. But closer attention shows that this does not involve a radical change in structure; the divisions are still there, only their boundaries are a little less distinct; instead of a double bar, there is an interlocking or a transition. The sense of unity is also strengthened by the magnificent use Verdi makes of the recurring motif of “the kiss,” first heard in the orchestra near the end of the love duet in Act I and returning twice with indescribably poignant effect in the closing scene of the opera.

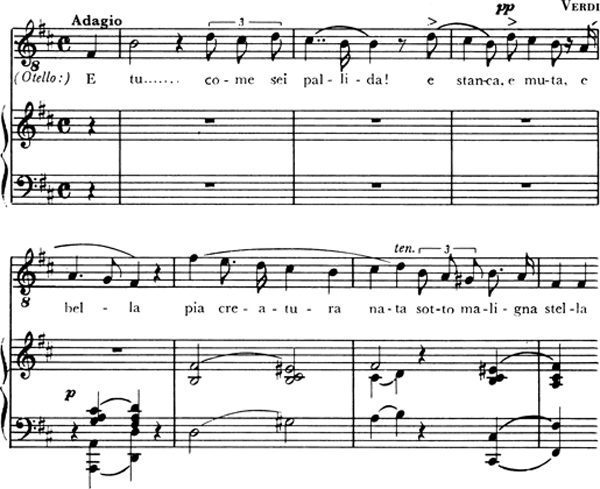

Much of the continuity of style in Otello must also be attributed to the libretto, which offers few opportunities for numbers of the traditional sort, being instead made up for the most part of scenes of continuing action that are most appropriately set to a different kind of music—a flexible, dramatically powerful, sensitive, and infinitely varied melody, supported by the orchestra with characteristic rhythmic motifs for each scene and organized in long periods by means of the harmonic structure: “dramatic declamation in strict time substituted for classical recitative on the one hand and Wagnerian polyphony on the other.”51 This declamation does include both strict recitative (used especially effectively for the dialogue between Otello and Emilia at the end of the scene of Desdemona’s murder in Act IV) but also melodic phrases of the most pronounced arioso character, with extreme compression of emotion. No such free, passionate, long-spun melodic line had been heard in Italian opera since Monteverdi’s Poppea. It is clearly enough the model for Puccini and other later Italian composers, who constantly aimed at, but seldom attained, the pathos of Verdi in this style (example 20.8).

Even within the more or less formal arias, the melody is a long way removed from the singsong, regularly patterned tunes of some of the early operas. It is no less expressive than these, no less vocal, but nobler, more plastic, more richly interwoven with the orchestra, more intimately wedded to the harmony. In the harmonic idiom itself, Verdi never went to Wagnerian lengths of chromaticism, though no composer was more alive to the effectiveness of a few judicious chromatic alterations. He was also aware of the broadening conceptions of tonality that prevailed at this time, as witness the freedom of his harmonic vocabulary and the range of his modulations.52

EXAMPLE 20.8 Otello, Act IV

Inasmuch as it has been claimed that Verdi in his later operas was imitating the Wagnerian music drama, it may be well not only to emphasize again the continuity of the musical style of Otello with that of Verdi’s preceding works but also to point out certain fundamental differences that remain between the two composers. In the first place, Otello and Falstaff are both singers’ operas; in spite of the greater independence of the orchestra, it is never made the center of the picture, and the instrumental music does not have either the self-sufficiency or the symphonic range of development that it has in Wagner. Second, Verdi never adopted a system of leading motifs; the formal unity of his operas is like that of the classical symphony rather than the Romantic tone poem, that is, a union of relatively independent individual numbers with themes recurring only in a few exceptional cases. Third, Verdi’s operas are human dramas, not myths. Their librettos have no hidden world, no symbolism, no set of meanings below the surface. They are free of any trace of the Gesamtkunstwerk or other theories. And finally, there is about Verdi’s music a simplicity, a certain Latin quality of serenity, which the complex German soul of Wagner could never encompass. It is a classic, Mediterranean art, self-enclosed within limits that by their very existence make possible its perfection.

As Otello was the climax of tragic opera, so Falstaff (1893) represented the transfiguration of opera buffa. Written on a libretto arranged by Boito from Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor and the Falstaff episodes from the two parts of Henry IV, it is not only a remarkable achievement for an octogenarian but a magnificent final crescendo of a great career.53 Excelling all earlier works in brilliancy of orchestration, wealth of spontaneous melody, and absolute oneness of text and music, it is a technical tour de force, abounding in the most subtle beauties, which often pass so quickly that only a close acquaintance with the score enables the listener to perceive them all. Because of this very fineness of workmanship and perhaps also because of the profound sophistication of the ideas underlying the music,54 Falstaff has never become so popular with the public as any of the other three comic operas with which alone it can be compared—Mozart’s Figaro, Rossini’s Barbiere, and Wagner’s Meistersinger. Falstaff is the kind of comedy that can be imagined only by an artist who is mature enough to know human life and still be able to laugh.

The score is a blend of traditional forms and free structures, with the musical design governed solely by the demands of the drama. The vocal lines consist of lively tunes, devoid of melismas; the orchestration is light and delicately colored. Throughout the score, various operatic traditions are parodied. Interestingly, the composer parodied himself in the conspiracy scene at the end of the first part of Act III.

Verdi took his leave of opera with a jest at the whole world, including the art of music: Falstaff ends with a fugue, that most learned of all forms of composition, to the words “Tutto nel mondo è burla” (All the world’s a joke). At the beginning of the opera, Falstaff is alienated from society; at the end, he becomes an accepted part of the social structure, with a reunion of all the characters mirrored in the polyphonic equality of the fugue.

Boito and Ponchielli

Arrigo Boito (1842–1918) was more than a librettist; he was also a novelist, composer, and critic.55 In his writings, he was extremely outspoken about the degree of conformity within the Italian operatic tradition; at the same time, he expressed interest in a type of opera that would permit a union of the arts. Boito admired Wagner and had been one of his ardent Italian disciples but in later years was converted to Verdi by the music of Aida and the Requiem. The precepts of operatic composition advocated by Boito in prose did not find manifestation in his own opera, Mefistofele, of which he wrote both libretto and music. The premiere of Mefistofele at La Scala in 1868, which he himself conducted, was a disastrous failure. His score was the target of criticism from the traditionalists, who were determined to thwart the aspirations of one whose sympathies were with the Scapigliati, an association of musicians, artists, and other intellectuals who in the mid-1860s and 1870s focused upon freeing artistic creativity from the shackles of tradition. Seven years later, Boito brought forth a revised score of Mefistofele, one in which the portions that caused a furor in 1868 were eliminated. Other changes that showed Boito finally gave in to the traditionalists included the recasting of the role of Faust from a baritone to a tenor and the addition of a few numbers, such as the duet “Lontano, lontano, lontano.”This new version of Mefistofele, consisting of a prologue and four acts, was first staged at Bologna in 1875, to considerable acclaim. With it, Boito presents a score that he has painted with bold strokes of originality, showing little dependence on what had become the conventional fourfold structure (tempo d’attacco, cantabile, tempo di mezzo, cabaletta) for operatic scenes.

Mefistofele holds much closer to the model of Goethe’s Faust than either Berlioz’s or Gounod’s settings. The score includes many marginal Wagner-like disquisitions on the characters and events of the drama. Boito’s music is interesting and original in many respects but Mefistofele, although still fairly often performed, has never become as great a popular success as Gounod’s more conventional work. Mefistofele was the only opera Boito completed. Nerone was left unfinished at his death but was given in 1924 in a version arranged by Arturo Toscanini and Vicenzo Tommasini.56

Whereas Boito was a leader among the “advanced” Italian composers of the 1860s, the chief figure among the “conservative” group, which found its ideal in the operas of Verdi’s middle period, was Amilcare Ponchielli (1834–86).57 He had several operas produced prior to making a successful debut at La Scala with I Lituani (1874). Antonio Ghislanzoni, author of the text for Verdi’s Aida, was the librettist. Ponchielli’s score was acclaimed for its orchestration, its large scale choral numbers, and especially for the instrumental music of the overture and the lengthy ballet, a feature that is also prominent in his La Gioconda and Il figliuol prodigo. In I Lituani the duet prevails, not the aria (of which there are only two in the opera), as the primary vehicle for advancing the drama.

La Gioconda (1876), with libretto by Boito, is Ponchielli’s most famous opera and it still holds the stage in Italy and elsewhere. It is an old-fashioned melodramatic work, in which the heroine commits suicide as a way to help two lovers escape. Although La Gioconda achieved considerable success at its La Scala premiere, the opera was nevertheless revised by the composer for each of its subsequent productions in Venice (1876), Rome (1877), and Milan (1880), this last providing the definitive version. Several aspects of the Gioconda score deserve special notice. One can be found in the contrapuntal writing that pervades many parts of the score. Another occurs in the finale to Act III: the orchestra concludes the act with a fortissimo and largamente restatement of the main melody that prevails in the preceding vocal number. Use of recurring thematic material in this manner to conclude a major structural division of an opera was to become a feature of works by Italian composers who succeeded Ponchielli.

1. Della Corte, L’opera comica italiana. 2:199ff; Engländer, “Paërs Leonora and Beethovens Fidelio.”

2. Excerpts from Pavesi’s operas are in Gossett, ed., Italian Opera, 1810–1840, vol. 37.

3. See Freeman, “Johann Simon Mayr and His Ifigenia in Aulide”;Allitt, J. S. Mayr: Father of Nineteenth-Century Italian Music.

4. Mayr’s La rosa bianca e la rosa rossa was set to Felice Romani’s first libretto.

5. See Balthazar, “Mayr, Rossini, and the Development of the Early Concertato Finale.”

6. As early as his Lodoïska, Mayr broke with the tradition of exit arias.

7. The cavatina and cabaletta types of solo song will be discussed later in this chapter.

8. For a discussion of Rossini’s works created for Paris, see chapters eighteen and nineteen. See also Stendhal, Vie de Rossini (untrustworthy for facts but lively reading); Strunk, ed., Source Readings (1950 ed), 808–26; and biographical studies by Osborne, Radiciotti, Ballola, and Weinstock. See also Grempler, Rossini e la patria.

9. Tancredi is based on a play by Voltaire, but Rossi’s libretto for the first performance in Venice omitted the final death scene. Instead of having Tancredi die in combat, Rossi permits Tancredi’s life to be spared so that he can learn of Amenaide’s innocence. When Tancredi was staged in Ferrara one month later (March 1813), it was given a tragic ending together with a new musical setting by Rossini. In all subsequent performances during the nineteenth century, Rossini reinstated the Venetian finale, apparently guided by audience preference for the lieto fine. Both versions of Tancredi have been published in the new edition of Rossini’s operas, the Ferrara version having come to light in 1974. See Gossett, “Happy Ending for a Tragic Finale.”

10. The castrato role in his Aureliano in Palmire (1813) was sung by Giambattista Velluti, one of the last great castrati, who also appeared in Meyerbeer’s Il crociato in Egitto (1824).

11. Scott’s poem was published in 1810. For more on Walter Scott’s influence on opera librettos, see Mitchell, The Walter Scott Operas; idem, More Scott Operas.

12. Cf. Longyear, “The Banda sul Palco: Stage Bands in 19th-Century Opera.”

13. The French version of Mosè in Egitto was also presented in an Italian version and entitled Mosè e Farone. See Conati, “Between Past and Future: The Dramatic World of Rossini.”

14. For more on Guillaume Tell, see chapter eighteen.

15. In 1980, the city of Pesaro (Rossini’s birthplace) inaugurated the Rossini Opera Festival, which, in conjunction with Fondazione Rossini, is committed to presenting all of Rossini’s operas.

16. See Weinstock, Donizetti and the World of Opera in Italy, Paris, and Vienna; Ashbrook, Donizetti and His Operas; Zavadini, Donizetti: Vita, musiche, epitolario; Ashbrook and Budden “Gaetano Donizetti.”

17. The first performance took place in October 1960 at the Teatro Donizetti, Bergamo. See Ashbrook, Donizetti and His Operas, 597n. 30.

18. Scott’s Kenilworth, translated into Italian in 1821, had already served as a source for other theatrical productions, among them Eugène Scribe’s libretto for Auber’s Leicester ou Le Château de Kenilworth (1823) and Gaetano Barbieri’s play entitled Elisabetta al castello di Kenilworth (1824).

19. For example, excerpts from his Enrico di Borgogna, Otto mesi, Imelda, and Il paria were adapted for Anna Bolena.

20. Lang, The Experience of Opera, 122. Anna Bolena is the first of what is sometimes referred to as Donizetti’s “trilogy of operas about Tudor queens.” The other two are Maria Stuarda (1835) and Roberto Devereux (1837). All three, it should be emphasized, were conceived independently and were never intended to be produced as a trilogy.

21. Philip Gossett, in his study of the autograph score of Anna Bolena, discusses the way this opera illumines the process by which Donizetti establishes a style that is both mature and uniquely personal. See his Anna Bolena and the Artistic Maturity of Gaetano Donizetti.

22. Cavatina does not define a particular kind of solo song. Its connotations are as varied as the scores in which the term appears, from the cavatina in Graun’s Montezuma to that in Weber’s Der Freischütz, from the slow-fast cavatina-cabaletta type in Mayr’s operas to the multipurpose application of the term in the works of Donizetti. Cantabile-tempo di mezzo-cabaletta designates the three-part form with an intervening section.

23. Self-borrowings are characteristic of Donizetti’s operas, often involving highly improbable reuse of materials.

24. There was even a production in New York in 1849. Successful revivals have been staged in Italy and the United States ever since the 1960s.

25. With the exception of Sara’s romanza, every number in this opera has its cabaletta. See, in particular, Roberto’s “Come un spirito angelico” followed by the allegro cabaletta “Bagnato è il sa di lagrime” in Act III.

26. Bellini’s operas were also in great demand in America in the 1830s, especially La sonnambula and Beatrice di Tenda.

27. Studies of Bellini’s life and works include those by Weinstock; Adamo and Lippmann; and Brunel. See also Bellini, Epistolario; Pastura, Bellini secondo la storia; Maguire, Vincenzo Bellini and the Aesthetics of Early Nineteenth-Century Italian Opera.

28. Cf. Dahlhaus, Die Musik des 19. Jahrhunderts, 96–98.

29. In Bellini’s case, Giovanni Battista Rubini and Guiditta Pasta were the two singers for whom he wrote some of his most famous music.

30. Florimo, La scuola musicale di Napoli; Notarnicola, Saverio Mercadante; idem, Saverio Mercadante nella gloria. See also Walker, “Mercadante and Verdi.” Facsimiles of some of the operas cited are in Gossett, ed., Italian Opera, 1810–1840, vols. 14–22.

31. See Ballola, “Mercadante e Il bravo”; Perna, La vestale di Saverio Mercadante.

32. Lists of Italian opera composers of the early and middle nineteenth centuries may be found in Adler, Handbuch der Musikgeschichte, 2:908, 912–14. The most important of them are P. A. Coppola (1793–1877), composer of La pazza per amore (1835); G. Pacini (1796–1867), Saffo (1840); the brothers Luigi (1805–59) and Federico (1809–77) Ricci, whose best work was the jointly composed Crispino e la comare (1850);A. Cagnoni (1828–96), Don Bucefalo (1847); E. Petrella (1813–77), Marco Visconti (1854) and Jone (1858);and F. Marchetti (1831–1902), Ruy Blas (1869).

33. See Budden, The Operas of Verdi; Weaver, ed, Verdi; Conati, Encounters with Verdi; Kimbell, Verdi in the Age of Italian Romanticism; G. de Van, Verdi’s Theater: Creating Drama through Music; Phillips-Matz, Verdi: A Biography; Rosselli, The Life of Verdi.

34. Between the second and third scenes of Act III of I Lombardi, Verdi has inserted a violin solo that borders on a mini-concerto. The solo violin also has an important part underpinning the famous trio of this same act.

35. In this same year, Nabucco had productions in Berlin, Barcelona, Stuttgart, Malta, Oporto, and Corfu and soon thereafter was staged in St. Petersburg, London, New York, and Buenos Aires.

36. Verdi, born and raised in the Duchy of Parma, had firsthand experience of foreign oppression, for after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, that portion of northern Italy previously held by the French was assigned to the Habsburgs of Austria.

37. In 1857 Verdi accepted a commission from the Teatro San Carlo at Naples, for which he planned an opera based on Shakespeare’s King Lear. When the singers engaged for the 1857–58 season did not measure up to his expectations, he changed plans and set a libretto that Scribe had written for Auber in 1833—Gustav III, ou Le Bal masqué. The Naples censors, however, rejected this libretto, even after Verdi agreed to make the requisite changes. The reason given was that an assassin had recently attempted to take the life of Emperor Napoleon III. Since Verdi was by this date committed to producing his opera, albeit in its revised format, he looked to Rome to stage the work in 1859. Presentday productions of Un ballo frequently adopt the original scenario, locating it in eighteenth-century Sweden, with a king as the victim of the assassin. Antonio Somma prepared the librettos for Il re Lear and Un ballo di maschera.

For a description of the New York premiere of Un ballo in maschera, see chapter twenty-nine.

38. The date of first performance for each of the operas cited is as follows: Oberto (1839), Nabucco (1842), I Lombardi alla prima crociata (1843), Ernani (1844), I due Foscari (1844) Giovanni d’Arco (1845), Attila (1846), Macbeth (1847), I masnadieri (1849), Il corsaro (1848), Luisa Miller (1849), La battaglia di Legnano (1849), Stiffelio (1850), Rigoletto (1851), Il trovatore (1853), La traviata (1853), Les Vêpres siciliennes (1855), Simon Boccanegra (1857), Aroldo (1857), Un ballo in maschera (1859), La forza del destino (1862); Don Carlos (1867), Aida (1871), Otello (1887), and Falstaff (1893).

39. It is understandable why Verdi, having experienced the absolutism imposed by the foreign powers who ruled his native land, was so attracted to Schiller’s dramas, for in them Schiller gives vent to his lifelong abomination of tyranny in all its guises.

40. Consider, for example, the prologue to Simon Boccanegra, where Verdi uses four characters whose roles are scored for three baritones and one bass to convey the mournful quality of that scene.

41. See the “Introduzione” to Act I of Rigoletto, with its three orchestras, playing together. Cf. Chusid, “Notes on the Performance of Rigoletto

42. There are, of course, exceptions. See, for example, Attila.

43. Cf. also the last scene of Un ballo in maschera, and the waltzes in Strauss’s Rosenkavalier.

44. The model for the melody in example 20.7 can be found in “O Pia mendace” from Pia de’ Tolomei, 1837) by Donizetti. See Budden, The Operas of Verdi, 2:36.

45. Cf. Roncaglia, “Il ‘tema-cardine’ nell’opera di Giuseppe Verdi”; Kerman, Opera as Drama, 155ff.

46. Even before Don Carlos made its way to the stage of the Paris Opéra, Verdi had decided the work was too long and he cut out whole sections from the score. This excised material was discovered in the library of the Opéra in the 1960s and has since been restored to the score, making it possible to record the opera in its unabridged French language version.

47. Verdi, with the help of Boito, revised Simon Boccanegra, eliminating those elements which were not part of his “Italian” vocabulary. A similar revision of Don Carlos was made in 1884.

48. For details, see [Verdi], I copialettere, 631–75; Werfel and Stefan, eds., Verdi: The Man in His Letters, 278–87.

49. Letter to Franco Faccio, 1889, quoted in Toye, Giuseppe Verdi, 196ff. The sentiments here expressed dated from many years previous. See also Franz Werfel’s novel, Verdi, for an imaginative treatment of this phase of the composer’s life.

50. See Kerman, “Verdi’s Otello, or Shakespeare Explained”; Roncaglia, L’Otello di Giuseppe Verdi.

51. From a review of the first performance in Secolo, quoted in Toye, Giuseppe Verdi, 191.

52. See, for example, the tonal scheme of the duet at the end of Act I: G-flat–F–C–E–D-flat.

53. Following the premiere in Milan, the La Scala opera company took Falstaff on the road with performances in Genoa, Rome, Venice, Vienna, and Berlin. The opera, in a French-language version, was also presented in Paris, presumably in the spring of 1894. In the course of all these productions, Verdi made a number of significant changes to the score, with most of them designed to improve the pace of the dramatic action. Ricordi published several versions of Falstaff, including a French version, but no one version takes precedent over the others, for each has its merits.

54. Cf. Noske, “Ritual Scenes in Verdi’s Operas.” See also Hepokoski, Giuseppe Verdi: Falstaff.

55. For an overview of Italian operas that had successful premieres in the twenty-two-year period between Verdi’s Aida and Falstaf see Nicolaisen, Italian Opera in Transition, 1871–1893. On Boito, see biographies by Nardi and Mariani; Nicolaisen, Italian Opera (chap. 4). See also Boito, Tutti gli scritti; Scarsi, Rapporto poesia-musica; Smith, The Tenth Muse. An important collection of letters is contained in Medici and Conati, eds., Carteggio Verdi-Boito.

56. In both Mefistofele and Nerone, there exists a struggle for supremacy between opposites (the dualism of good and evil, God and the Devil) that defies resolution. See Borriello. Mito, poesia e musica nel Mefistofele.

57. See De Napoli, Amilcare Ponchielli: La vita, le opere; Nicolaisen, Italian Opera, chap. 3.