CHEMOTHERAPY (OR ‘CHEMO’) is a cancer treatment used to kill cancer cells, although healthy cells are also affected. The drugs damage cells and stop them growing. Normal cells can usually repair the damage, but cancer cells can’t and so they die.

Most patients have chemotherapy after their surgery but before radiotherapy. This is called ‘adjuvant chemotherapy’.

You may be advised to have chemotherapy before surgery, particularly if you are young, have positive nodes or have inflammatory breast cancer (see here). Chemotherapy is also used to try and shrink a large cancer so you don’t need a mastectomy, and sometimes the breast cancer completely disappears. This is called ‘neoadjuvant chemotherapy’. It is more effective in women with triple negative cancers. If your cancer is HER2-positive, having neoadjuvant chemotherapy means you can have an additional drug called Perjeta that also targets HER2 and can improve your prognosis (see Chapter 11). It can also buy you time to get the results from a BRCA test (see here) which could affect your surgical decisions.

If you have primary breast cancer, surgery gives you the greatest chance of a cure. Chemotherapy is used to reduce the risk of a recurrence. We discussed how doctors determine whether you will benefit from chemotherapy in Chapter 3 (here). Before recommending chemotherapy, your oncologist will also consider your general health and lifestyle. Chemotherapy can be gruelling, even for the youngest, fittest patients. It is offered to older patients, but your doctor needs to make sure that you’re fit enough to cope with it, and that the benefits outweigh the risks.

Some cancer patients refuse chemotherapy for a variety of reasons. The most common reason is not wanting to lose their hair (although there are now cold caps to help you keep it – see here) or wanting to try alternative therapies instead. Please remember, if your doctors are recommending chemotherapy, it means that your risk of the cancer coming back is already high and, at the moment, there aren’t any other comparable treatments that have been proven to reduce this risk.

If you have primary breast cancer, your chemotherapy will normally take between three and five months. It is given in ‘cycles’, a cycle being the time between each treatment. Each cycle can be one, two or three weeks long, depending on which drugs you are having. The cycles give your body time to recover and repair the healthy cells that were damaged, and let you recover from the side effects before the next cycle starts.

If you have secondary breast cancer, you may be recommended to have treatment for the rest of your life. Which drugs you have will depend on the extent of your disease and where in your body it is. Breast cancers can become resistant to chemotherapy drugs, so you might have to switch from one drug to another to keep the cancer under control.

You will have blood taken before each cycle to make sure that your immune system is strong enough to cope with chemotherapy. The test measures the number of neutrophils (a type of white blood cell) in your blood. Because chemotherapy affects your bone marrow (where blood cells are made), the number of neutrophils in your blood tends to fall with every cycle. If you don’t have enough neutrophils, your chemotherapy will be postponed until your blood test reaches a threshold level where it is safe to give you another dose. The blood test will also check that your liver and kidneys are working well enough to withstand the next dose.

If you have neoadjuvant chemotherapy, you may have a breast MRI to monitor the response of your cancer to chemotherapy. If the MRI indicates that your cancer is growing, your oncologist will stop treatment, ask your surgeon to operate, and then continue chemotherapy once you’ve recovered from the surgery.

Your oncologist will see you regularly to ask you about the side effects you may have had and answer any questions. They will examine you, review your blood tests and scans and prescribe drugs to help with the side effects and any other drugs you need to take at home.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOUR ONCOLOGIST/SPECIALIST ONCOLOGY NURSE

● Why are you recommending chemotherapy?

● What happens if I don’t have it?

● How will you know if it’s working?

● What happens if it doesn’t work?

● Where will I have chemotherapy?

● How long does it take?

● What are the side effects, when will they happen and how long will they last?

● Are there research trials I could go on to?

● Is there anything I should and shouldn’t do during treatment?

● How long does it take for the side effects to start?

● What do I need to monitor at home?

● What do I do if I feel unwell at home during the day, in the evenings and at weekends?

There are several different chemotherapy drugs that are used in different combinations. Your oncologist will decide which is best for you based on the specific details of your breast cancer and the results from years of research trials.

You will get detailed information about each of the drugs you have, and that information can also be found on, and downloaded from, the Macmillan, Breast Cancer Care and Cancer Research UK websites (see here for details). Most chemotherapy drugs are given with other medicines, like antihistamines and steroids, to stop you getting an allergic reaction, and to help with sickness and vomiting.

These are the some of the common drugs that are used:

● FEC (Fluorouracil (5FU), Epirubicin and Cyclophosphamide)

● FEC-T (FEC then a Taxane – Docetaxel (Taxotere) or Paclitaxol (Taxol))

● T-FEC (Taxane then FEC)

● AC or EC (Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) or Epirubicin and Cyclophosphamide)

● Platinum-based (Carboplatin and Cisplatin)

● CMF (Cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate and 5FU)

Most chemotherapy regimens now include a taxane (third-generation chemotherapy). If you have a BRCA mutation or a triple negative cancer you will probably get a platinum-based agent.

These are some of the chemo drugs used for secondary cancer, but they may only be available as part of a research trial:

● AC (see above)

● Capecitabine (Xeloda)

● Carboplatin

● Cisplatin

● Eribulin (Halaven)

● Gemcitabine (Gemvar)

● Vinorelbine (Navelbine)

Additional targeted therapies for secondary cancer such as CDK4/6 inhibitors (immunotherapy) are discussed in Chapter 11.

Most drugs are given into a vein (intravenously), but some come as tablets. There are three ways to give chemo intravenously:

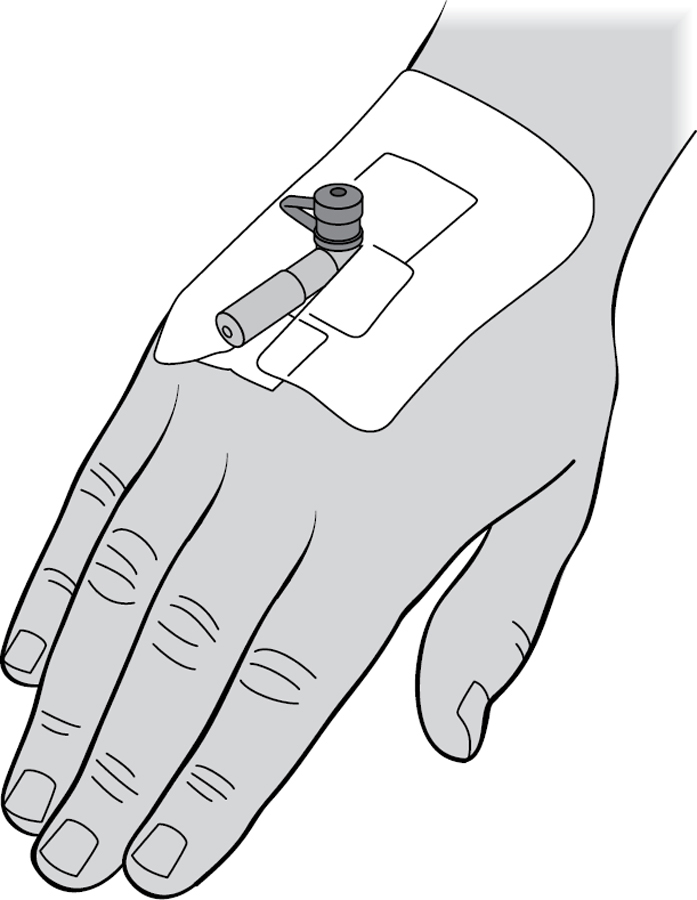

A cannula is a short plastic tube put into a vein, normally on the back of your hand. It is removed after each treatment. Chemotherapy drugs can irritate and scar your veins which can make it harder to find a good vein each time.

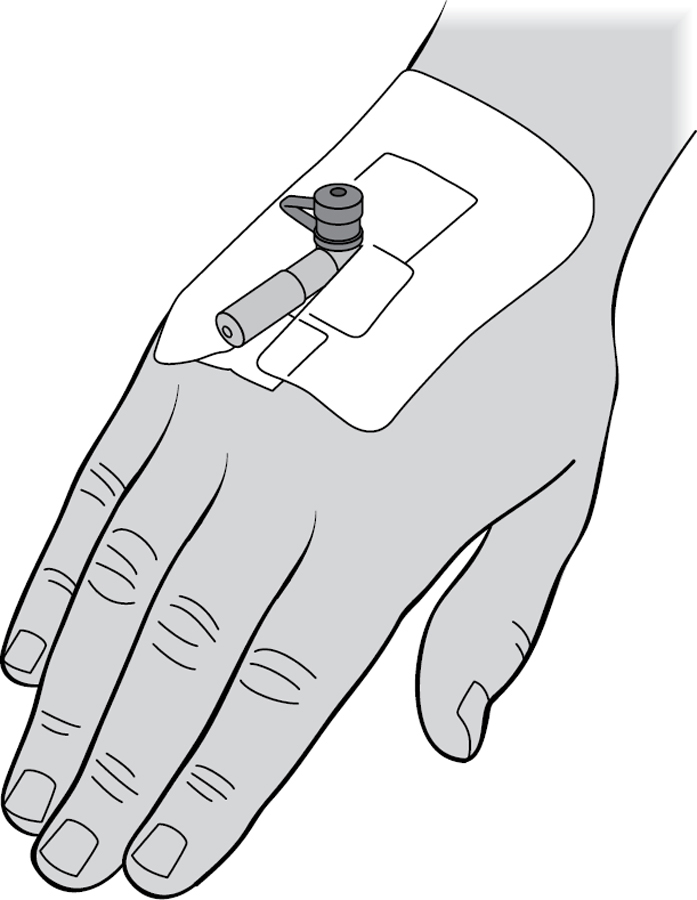

This is a much longer cannula which is put into a vein in your arm, just above your elbow, and ends in a large vein that goes to your heart. It’s put in using local anaesthetic and stays in place until you have finished chemotherapy. You can also have blood taken through it. It’s covered with a waterproof dressing which needs to be changed every week. You can buy coloured PICC line covers from websites such as Live Better With Cancer: https://livebetterwith.com

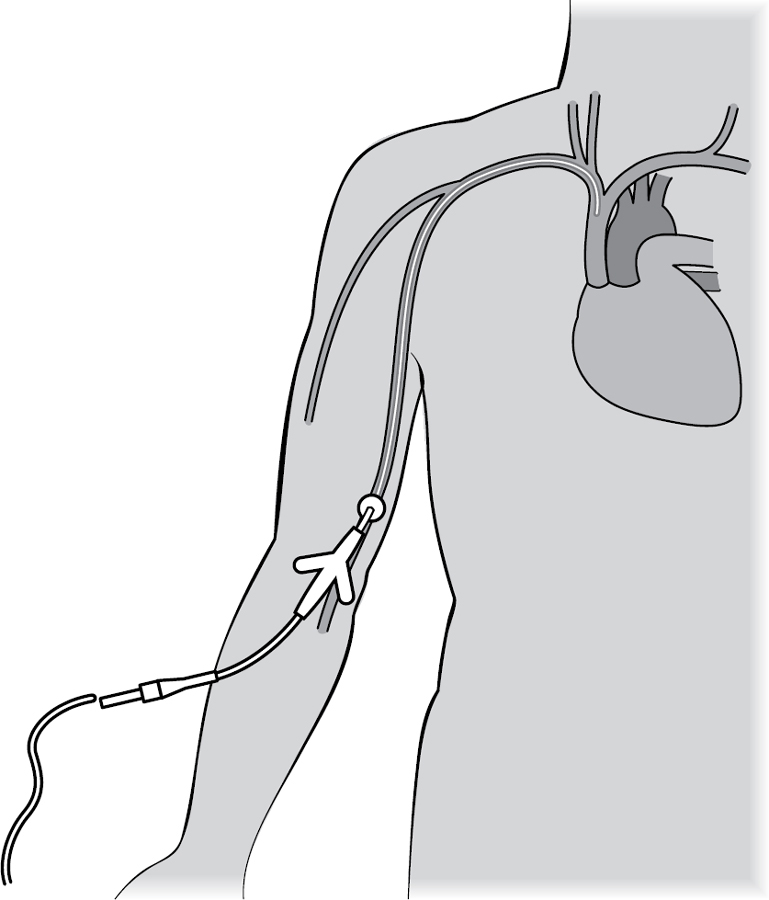

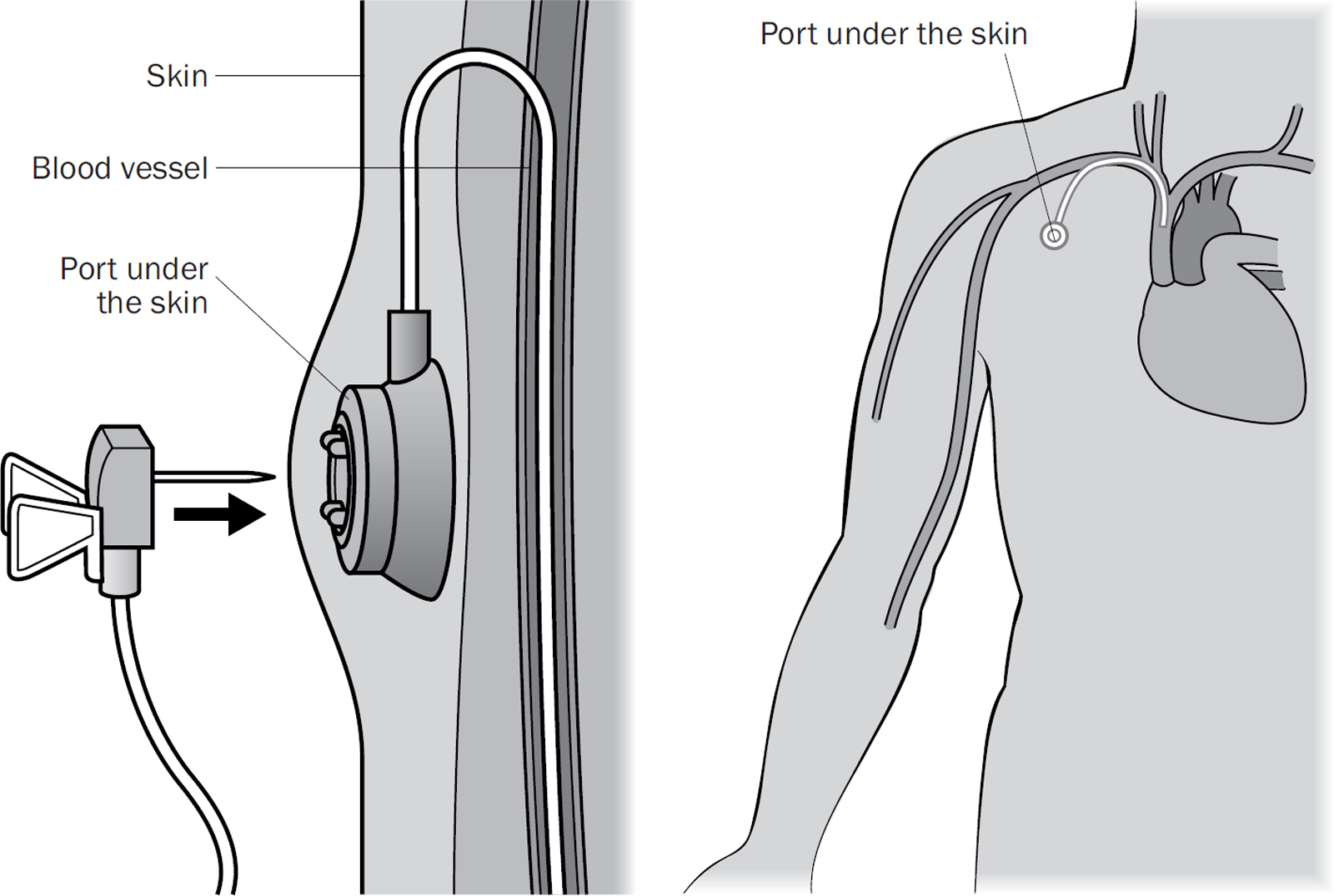

A long cannula is put into a large central vein in your chest. It’s connected to a ‘port’ which sits just under your skin, normally below your collarbone. The drugs are given through the port which is punctured using a needle, and trained nurses can also take blood from it. It is normally put in using local anaesthetic and sedation and stays in until you have finished chemotherapy.

Most patients will have chemotherapy in an oncology day unit in a hospital. You should be given a tour of the unit before you start. If not, ask for one as it makes it less scary on the day. Also ask what food and drink is available, as a lot of units provide only tap water (you can take your own food and drink in with you). Most units have large, comfortable reclining chairs for you to sit in, and if you’re going privately you’ll probably be shown directly to your own cubicle. Alternatively, you may sit on a trolley. There will probably be other patients sat in the chairs next to you. Some hospitals now have mobile chemo units, which means that if you live a long distance from the hospital, the chemo van may come to a place near you. A few large primary care centres (GP practices) can also give chemotherapy.

You can wear whatever you like! You need to be comfortable as you may be there for several hours. If you have a port or a PICC (see here and here), your nurse needs to be able to access it, so wear a short-sleeved top, and no polo necks. You may want to dress up and make an occasion out of it, especially for your last cycle, so feel free to get inspired.

Once your blood results have come back (if you have them on the day of chemo), and there is a free chair for you to sit in, you will meet a chemotherapy nurse who will give you your drugs. In our experience, chemo nurses are fantastic at making you feel as relaxed as possible. They also know about the side effects of the drugs you’re being given and how scary it feels, so talk to them. Some drugs are left to infuse into your veins over an hour, while others (like FEC) have to be injected slowly by hand, which means the nurse will sit with you for one to two hours while they administer them. Having chemo can be lonely, especially if everyone around you has visitors. It’s nice if you can find a relative or friend to come and sit with you. On the other hand, you might just want to get lost in a book or a film/box set.

The time varies depending on which drugs you are having, and how they are being given. It normally takes one to two hours. If you are using a cold cap, you may be in the chemo unit for up to six hours (see here).

Most people feel well enough to make their own way to the hospital, either by driving or using public transport. However, after you have had chemo you may not feel well enough to drive yourself home. Sometimes the side effects kick in quickly, and you may feel sick or tired on the bus or Tube home. We advise getting someone to take you home each time if you can, especially if you have some distance to travel.

WHAT SHOULD YOU TAKE?

This is what we took with us:

● Entertainment – books, magazines, crosswords, headphones to listen to music, a tablet loaded with box sets or films

● Phone and a charger

● Food and drink – water can taste awful, so taking squash to flavour it can help

● Warm socks and slippers or flip-flops so you don’t slip when going to the toilet

● Gloves, a scarf and a warm blanket if you are cold-capping (see here)

It normally takes 12–24 hours for the effects to kick in, and often starts with a funny taste in your mouth followed by flu or hangover symptoms which get worse over the next couple of days. This slowly improves over the next few days until you feel almost normal. Everyone has a different pattern, and you will come to learn which are your really bad days. As the cycles progress, you will find that you don’t bounce back as quickly or as high as you did in the beginning, since the drugs gradually accumulate in your body. However, you will still get your good days and weeks, and it’s worth bearing in mind that, as you get more tired, you’re nearing the end of your treatment.

Because chemotherapy targets any cells that are rapidly dividing, this means that your hair, skin, nails, taste buds, the lining of your gut, and your bone marrow (which produces blood cells) are all affected and this explains the various side effects. Most of these side effects disappear when you finish chemo, although you may be left with some ‘collateral damage’ – long-term side effects that might not improve, such as numbness in your fingers and toes, called ‘peripheral neuropathy’ (see here). It can take six to twelve months to fully recover. Some studies suggest that chemotherapy can biologically ‘age’ you by up to 10 years, though this will depend on which drugs you receive and how you react to them.

Before we start talking about the side effects, here are the two most important lessons we learned to minimise your body’s reaction to the drugs:

1. Drink 2–3 litres of water every day. It helps flush out the chemotherapy, it rehydrates you and you will feel better for it.

2. Walk for 30 minutes every day. Try to do this even when you feel ghastly; even when you have to stop to catch your breath, spit or be sick every 10 minutes; even when you can only walk to the end of the road and back because you’re so out of breath. Lots of studies have shown that regular exercise reduces the side effects of chemotherapy, and we both saw the benefits from daily exercise. Try to persuade someone to walk with you. You’ll hate us for making you do it, but it will make you feel better. We promise. If you’re an athlete, we cover training and exercise during chemotherapy in Chapter 18.

The most common side effect of chemotherapy is hair loss and it’s the one that most people are afraid of. You lose all your hair – pubic, leg, chest, underarm, facial hair, and, towards the end of your treatment, your eyebrows and eyelashes (because they grow more slowly). Hair loss normally starts at around Day 13. Your pubic hair often falls out first, followed by clumps of hair that collect on your hairbrush or the bottom of the shower.

Even though Liz knew this was going to happen, she still cried in the shower when her first clump of hair came out. Being bald can be very hard to cope with, especially if your hair is an important part of your image. Losing your hair can stop you feeling feminine and make you very self-conscious when you leave the house. There are lots of ways to cope with being bald, which we’ll cover below, and you can even have fun with it. But first, let’s talk about cold-capping, which is something you can do to try and keep the hair on your head, like Trish.

This is a tight rubber cap with freezing cold fluid running through it, covered with a neoprene hat with a chin strap to keep it in place. The freezing temperature lowers the blood flow to your scalp and reduces the effect of the drugs on your hair. It works in around half the people who try it, and it worked for Trish. (She had short hair to start with, and only had a bit of thinning, although she still lost her eyebrows, eyelashes and pubic hair.)

The cap has to fit tightly to work, especially at the top of your head where hair loss would be most obvious. Be fussy and make sure it fits properly. You wear the cap for half an hour before and up to one hour after each infusion. You will feel cold, and you might get an ‘ice cream headache’, so wear warm gloves, scarves and socks, and you could also take a heated electric blanket. It’s a good idea to take some paracetamol beforehand.

You must be really gentle with your hair. If it is very long, you might want to cut it to shoulder length so it’s easier to manage. Wash it no more than once or twice a week with a gentle shampoo; take care when brushing (use a wide-toothed brush or comb and hold your hair at the roots) and avoid heat (such as hairdryers and straighteners).

When your hair does start to fall out, you might want to shave it off in one go rather than deal with the mess (and emotional fall-out) of losing it over a few days or weeks and having a very straggly, thinning, head of hair. The shave is never going to be easy. Some people make an occasion of it and throw a party or open a bottle of bubbly and get their partner to do it. If this isn’t something that appeals, you can ask your hairdresser to do it, like Liz did. However you do it, you will almost certainly cry. Most hairdressers can squeeze you in on the day (as it’s hard to predict when you need to do it) and they normally don’t charge you.

There are many options for covering your head. Synthetic wigs are available on the NHS, but you may have to pay some of the cost. Human hair wigs are more realistic, but also more expensive. You may find a shorter hairstyle is more practical or choose a longer wig and cut it short as your hair starts to grow again. Wigs can be very hot to wear, especially if you have hot flushes, and you may find you don’t wear yours around the house.

Many people prefer to wear a scarf or hat instead. There are lots of websites selling headwear for cancer patients, ranging from simple cotton beanies to showy turbans for special occasions. Macmillan and Breast Cancer Care have a good list of retailers on their websites (see 178 and 181 for details). Tying headscarves is an art in itself – you can find videos on YouTube. If you do buy a hat, it might be too big for you without your hair, but you can buy hat adjuster pads that stick inside the brim to make them fit.

You may decide to be ‘bald and proud’, like Liz. It is scary going out in public for the first time (you’ll think everyone is looking at you and talking about you) but it gets easier. You can have fun with temporary tattoos and henna crowns, or even have a Turkish shave in a men’s barber shop. If you want to shave your head to keep it smooth, use a fresh blade every time, and get someone to help you do the parts you can’t see.

Losing your eyelashes and eyebrows can be even harder to cope with as they help define your face. You might want to get your eyebrows ‘micro-bladed’ (semi-permanent make-up) before you start treatment. The free ‘Look Good Feel Better’ course (see here) will teach you how to draw on eyebrows, and there are lots of videos online. A fine eyeliner can help mimic eyelashes. False lashes are hard to stick on when you don’t have any of your own and should be avoided if your skin is sensitive or sore. Your brows and lashes normally grow back within 2–3 months. There are expensive serums available that claim to speed up regrowth, but we’re not aware of the evidence behind them. We didn’t use them, and our lashes and brows grew back a few weeks after we finished chemo.

Your hair should start to grow back a couple of weeks after your last cycle, with a full head of hair within six months. When your hair does grow back, it may be a different colour and texture from your original hair, and often it first grows back as grey ‘chemo curls’. No one really knows why this happens. If you are young, your hair may return to your normal colour and texture, but if your hair had already started to go grey, it may remain grey and curly.

Your new hair will be fragile, like baby hair, and you don’t want to damage it, so wait at least six months before colouring it. Ideally get your hairdresser to do this for you, but if you can’t wait that long, use vegetable-based and henna dyes, and avoid anything permanent.

Because chemotherapy reduces the number of white blood cells (neutrophils) needed to fight infection, you’re more likely to get an infection during chemo which could potentially become life-threatening within a few hours if it isn’t treated. This is called ‘neutropenic sepsis’. It happened to both of us.

Your neutrophils start to drop halfway through each cycle and should return to normal in time for your next treatment. You may be given a course of antibiotics to reduce the risk of infection and your oncologist may also prescribe a drug called G-CSF. This stimulates your bone marrow to make more white blood cells. G-CSF is given as a daily or weekly injection (you can learn to give it yourself into the skin of your tummy or thigh). It can sting a little and does have significant side effects (bone pain, headaches, fever and flu-like symptoms), but it’s worth it to reduce the risk of you getting an infection.

The earliest warning sign of neutropenic sepsis is usually a rise in your temperature. You’ll be told to check your temperature twice a day. It is worth spending money on an accurate digital thermometer that goes in your ear because the cheaper models you put under your tongue can break and give faulty readings. You’ll be given a 24-hour emergency contact number, and you should call it if you have any of the following symptoms:

● your temperature is above 37.5°C or 38°C (depending on the advice you’ve been given)

● you suddenly feel unwell, even with a normal temperature

● you feel shivery and can’t stop shaking

● you have symptoms of an infection such as a cold, sore throat, cough, passing urine frequently or diarrhoea

You need to take these symptoms seriously, as any infection could be life-threatening. When you call the hospital, you will be told to either go straight to the oncology unit or to the A&E department. Unless you are very poorly, you don’t need to call for an ambulance, but you should leave the house within 15–20 minutes.

It’s a good idea to have an overnight bag packed ready to go, with a toothbrush, toothpaste and mouthwash, hand cream and lip salve, Vaseline, phone charger, notebook and pen, pyjamas, socks and slippers, a nice pillowcase (hospital ones aren’t soft), a list of the tablets you’re taking, something to entertain you, squash or flavoured water and snacks that you can eat (hospital food isn’t always the best thing to eat when you feel sick and everything tastes funny).

Liz was told she needed to pack a bag but didn’t because she never thought she would get a serious infection. When her temperature did rise and she had to go into hospital, she felt so awful it was hard to concentrate on what to pack.

You need to be quickly assessed by a doctor or nurse and given antibiotics into a vein within 60 minutes of being seen, usually before any blood tests or scan results come back. It is vital that you get these antibiotics promptly. Make sure you tell the person seeing you that you are having chemotherapy, so they know how important it is to give you the antibiotics quickly.

If your blood tests confirm that you have an infection you will be kept in hospital for a day or two (occasionally longer) to have more antibiotics through a cannula, before being sent home with antibiotic tablets. Often the blood results are normal and the high temperature was a false alarm, but it is better to be safe than sorry.

HOW TO REDUCE YOUR INFECTION RISK

● Stay away from anyone with a cough or cold, tummy bug or chickenpox.

● Avoid places like Jacuzzis, and public transport in the rush hour, especially in winter.

● If you have pets, always wash your hands after touching them, and wear gloves when cleaning up after them.

● Make sure you wash your hands before you eat and after you’ve been to the toilet.

● Clean your bottom gently but thoroughly after opening your bowels, and always wipe front to back.

● Brush your teeth and use a mouthwash after every meal.

● Use moisturiser and hand cream to stop your skin cracking.

● Use gloves when gardening and washing up, and don’t trim the cuticles of your nails.

● Use a fresh blade every time you shave or use an electric shaver.

You are at risk of getting an infection from contaminated food. You should avoid food that is out of date, in damaged packaging or loose (such as bread rolls, salad from salad bars, food from deli counters and ‘pick’n’mix’ sweets that other people may have touched).

Some other tips to avoid infection include:

● Buy vacuum-packed meat and cheese.

● Avoid raw and rare meat, raw fish, shellfish and blue cheese.

● Cook eggs until the yolks are firm.

● Keep and prepare raw meat and vegetables separately.

● Wash and peel all raw fruit and vegetables.

● Always wash your hands after preparing food.

Chemotherapy alters your sense of taste and smell. You will have a funny taste in your mouth (often chalky or metallic) and things you normally love to eat and drink may taste awful. It can be hard to find things you do want to eat and drink. Although your taste may come back a little before each cycle, things never taste quite the same until after you’ve stopped treatment.

Working out what to eat can be very hard. There are several cookbooks available to help. Our favourite was The Royal Marsden Cancer Cookbook edited by cancer dietician Dr Clare Shaw (Kyle Books, 2015). It tells you what to try for different tastes, what to eat when it’s painful to swallow and what to eat if you need to gain or lose weight. Many recipes can be cooked in bulk and frozen in your good weeks.

If your mouth is very sore, stick to soft foods such as ice cream, smoothies, yoghurt and mashed potato. Try using strong flavourings (e.g. chilli, soy sauce) so you can actually taste something. Pineapple can help when things taste chalky and your tongue is coated. Experiment with new combinations and if you find something that works, stick with it. Liz survived on soggy Weetabix and maple syrup for breakfast because even sugar grains were too scratchy on her mouth. Trish had cheese on toast (with the crusts cut off) for supper every day for three months. If you’ve really lost your appetite or are very nauseous, set a reminder on your phone every couple of hours (or ask someone to prompt you) and try to get something down. Finally, it’s okay to drink alcohol and eat chocolate on your good days. Enjoy your taste buds while they’re recovering.

Although we recommended that you drink 2–3 litres of water a day, chemo gives it a horrible taste. Use lemons or cordial to flavour it and get used to carrying a bottle around with you and refill it at every meal time. Tonic water can also help to cut through the chalky taste in your mouth. You may find tea and coffee taste differently too, so if you want a hot drink, try hot squash or adding Bovril, Marmite or Vegemite to hot water.

Headaches are common and these normally respond to paracetamol, though occasionally you may need a stronger painkiller like codeine. You may get red flushed cheeks and acne on your face, and steroids can make your face look swollen. You can also get a painful spot on the edge of your eyelid called a stye. Use a hot compress to reduce the swelling and see your GP if it doesn’t settle.

The lining of your nose can get sore and bleed because you lose your protective nose hairs. Smear some Vaseline inside your nostrils to keep them moist. Your lips will get dry and can crack and split, so make sure you use a thick lip balm (such as Lanolips) regularly. The inside of your mouth can become sore and you may get ulcers on your tongue and gums. Your GP can prescribe an oral gel (such as Gelclair) that coats the ulcers and eases the pain. Your gums can bleed, and you might find it painful to swallow. Use a soft baby toothbrush after every meal with a gentle toothpaste like Biotene. Then rinse your mouth with a gentle medicated mouthwash such as Difflam, which your GP can prescribe.

You can get indigestion which your GP can treat with a tablet or a medicine. Most people feel sick, and you may vomit. Your oncologist will prescribe you an anti-sickness tablet (such as Ondansetron, Cyclizine or Emend). If one tablet doesn’t work, tell your doctor and they can try another – don’t suffer in silence. Lemon and ginger tea, sweets and biscuits can also help with nausea, and some people use magnetic wrist bands to ease the sickness.

Your bowel habits will change, and you will either have frequent watery stools (diarrhoea) or not go for days at a time (constipation). When you do eventually go, it may be painful and cause haemorrhoids (piles). Try changing your diet and adding more fruit and fibre (such as figs and prunes which are natural laxatives), if you can stand the taste of them. You will probably also need a variety of medicines and tablets to help as well, which your oncologist or GP can prescribe for you.

Your nails will soften, crack, split, or even fall off, and you may get brown spots underneath them. A nail-strengthening polish can help stop your nails feeling sore. Some people develop ‘hand-foot syndrome’ which causes a tightness, burning or redness in the skin of your hands and feet, peeling, cracked skin, blisters, ulcers and difficulty walking or using your hands. Use a thick hand cream regularly to keep your skin soft, wear gloves when washing up, use gentle, moisturising hand soap and don’t spend a long time soaking in hot water. Wear sensible, well-fitting shoes.

Chemotherapy can also damage the nerves in your fingers and toes (called ‘peripheral neuropathy’) which reduces your ability to feel pain and changes in temperature and makes it difficult to do fiddly tasks such as doing up buttons. These symptoms normally improve but they can be permanent. If you are affected, your oncologist may need to reduce your chemotherapy dose.

You might have generalised aches and pains, notice that your arms and legs swell, or get cramps. Regular painkillers will help with the aches and pains. Sit or lie with your legs raised on a cushion to help the swelling go down.

You will probably find it hard to concentrate on anything in the first few days of chemo, and this is called ‘chemo brain’. It can feel like you are living in a foggy cloud, and you literally can’t focus on a book or the TV for more than a few minutes at a time. You might struggle to find the right words or to remember simple things. It normally gets better as each day passes, so ride it out. It might help to keep a notepad close to hand to write down important things. Liz did jigsaws because she could dip in and out for a few minutes at a time and feel she’d accomplished something. Some people are still affected months and even years later. Liz still gets words muddled up from time to time, and that’s three years after treatment. Doing puzzles and brain-training games can help, as well as yoga and mindfulness techniques (see Chapters 14 and 18 for more on this).

Chemotherapy drugs and the medication given to reduce side effects can make you fatigued. Fatigue means mental and physical exhaustion that doesn’t get better after resting. We cover this in more detail in Chapter 15 (here).

If you are given steroids to help with the side effects, they can cause insomnia for a couple of days. This means that you can’t get to sleep and lie awake all night, which can be exacerbated if you’re in a lot of pain or are worrying. Make sure you’ve taken your painkillers. If you can’t get back to sleep, don’t fight it. Watch a TV show, read a magazine or chat to friends on forums (someone is always awake at 3am!).

Chemotherapy can affect your ovaries and bring on an instant menopause. See Chapter 16 for advice on symptom control and fertility preservation.

If you have diabetes, the combination of irregular and unusual meals along with steroids can make your diabetes unstable, with your blood sugar either too high or too low. If you take insulin, you will need to check your blood sugar level more regularly during treatment. Your oncologist may need to liaise with your diabetes specialist, your GP and/or a dietician to ensure that you have a workable plan for getting through chemo.

There is no magic formula for getting through chemo, but here are some of the things that worked for us. We hope they will help you too.

Make a ‘chemo caddy’ – a little box or bag that you keep next to you when you are lying on the sofa. It should have lip balm, hand cream, your thermometer, painkillers, a small notebook and pen, and a magazine or two. Invest in a warm, fleecy blanket to snuggle under. You might want to keep a duplicate set of toothbrush/toothpaste/mouthwash in a downstairs bathroom so you can brush your teeth after eating when you don’t have the energy to climb the stairs.

You need to take your temperature regularly, monitor your side effects and look out for signs of an infection. Keep a notepad close by to write down symptoms as they happen, because chemo brain can make it hard to remember things. You might also want to record your pulse rate, energy levels, exercise, sleep and bowel movements, and most smartphones have health apps that you can use to do this.

The free Macmillan ‘My Organiser’ app is a great resource (search for it on the Apple App Store or Google Play). It will set up reminders on your phone telling you when to take your tablets and drugs, as well as your appointments for blood tests and hospital visits. It also has links to the side effects of the drugs you’re taking as well as somewhere to store your emergency contact numbers.

You won’t feel great during chemotherapy but you’re not meant to feel really terrible, though it’s hard to know what is the normal level of suffering when you’re having it for the first time. Don’t suffer in silence. If in doubt, call your oncology nurse and ask them for advice. Remember – you’re never alone.

It’s so important not to put your entire life on hold during chemo. How much you can work, play and join in family life will depend partly on how often you have your infusions, which drugs you’re on and what your responsibilities are. You will soon work out the pattern of your bad and good days or weeks. When you feel well enough, meet up with friends, have a massage or go away for the weekend. If you have a special occasion like a wedding to go to, your doctor might be able to rearrange your chemo day so you’re well enough to go.

And what about sex? Everyone feels differently about sex during chemotherapy. You may find that it’s the last thing on your mind, but intimacy and sex can be a good way of connecting with your partner when everything around you feels like it’s falling apart. See Chapter 17 for advice on relationships, sex and contraception.

Children, elderly relatives and pets are a fact of life. Ask family and friends to help with school runs, washing and ironing, walking the dogs, etc. If your house isn’t spotless and your family eats take-away meals when you’re feeling rough, who cares? It can be equally difficult if you live alone and there’s no one to help look after you. Online forums and social media can help connect you with other people. It may also be worth asking someone to stay with you during your chemo ‘bad days’.

No matter how bad you feel on your very worst days, you will get through chemotherapy, and we promise you that in a year from now, you won’t remember how bad you felt. Liz wouldn’t have believed you if you had told her this at the time, especially on her really bad days, but honestly, one year later she couldn’t remember what it was like or how she felt. It’s only when she gets a really bad cold that she remembers the days spent curled up on the sofa feeling miserable.

If you have secondary breast cancer and chemo is for life, you may need to have hard conversations with your oncologist about the trade-off between the side effects of chemo and the risk of delaying it for a treatment break, or stopping it altogether. We discuss this in more detail in Chapter 23.

Reading this chapter won’t have been easy, and nobody wants to have chemotherapy. However, we hope that we’ve been able to throw you a lifeline and help you get through chemo if you need it.