BY LEARNING WHAT a breast is and how breast cancer develops, it will be easier to understand why and how your doctors are treating your cancer.

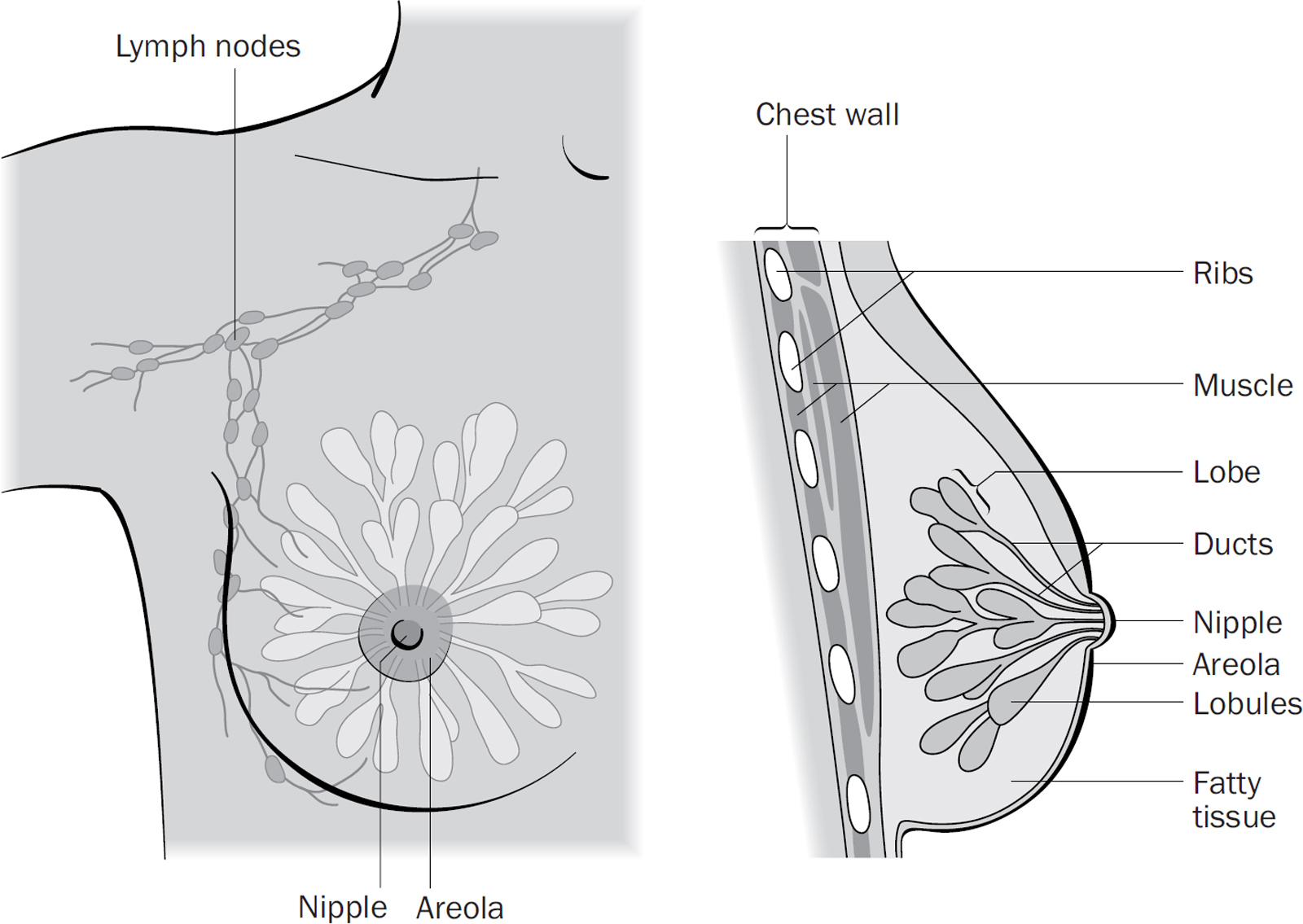

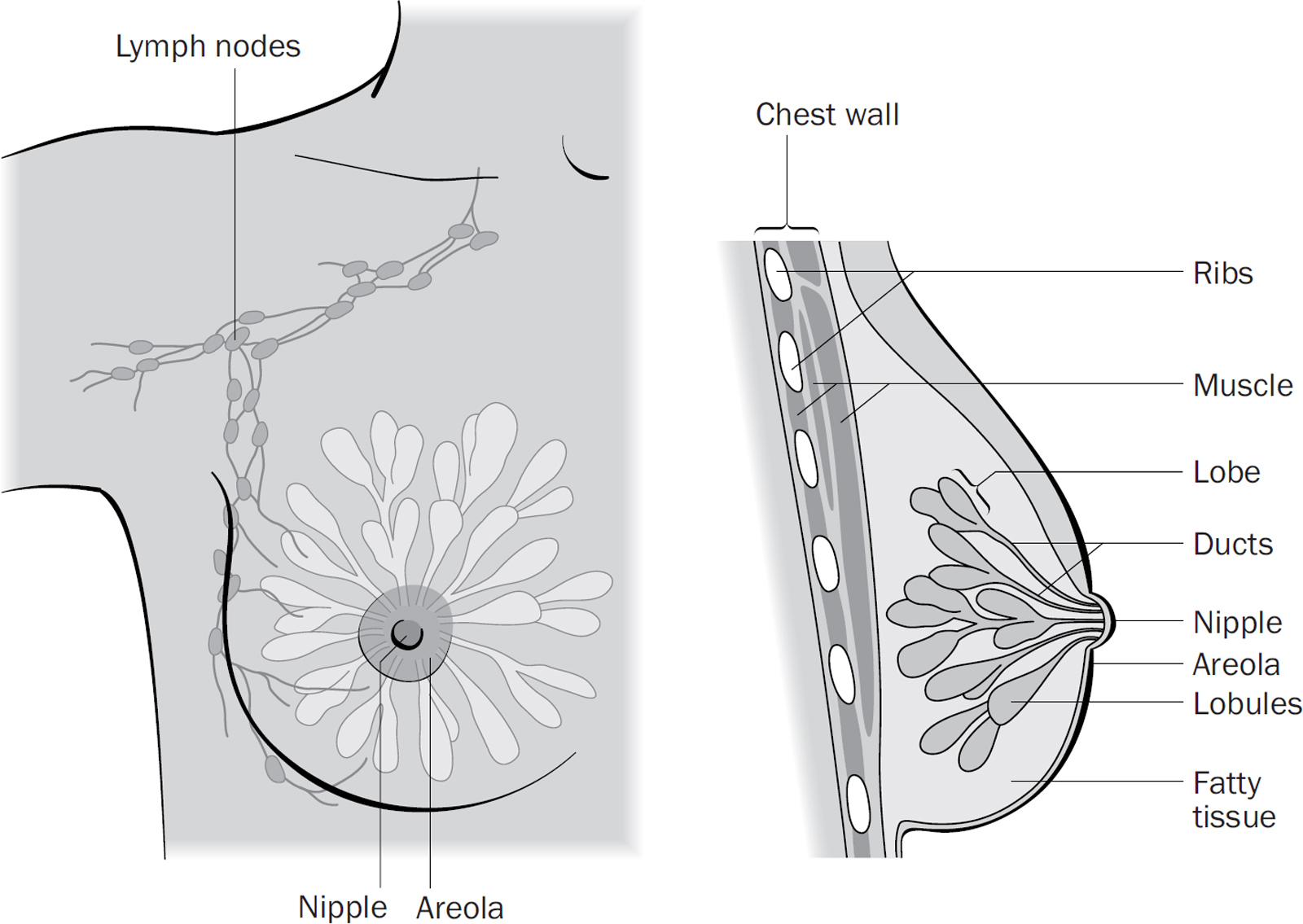

The breast sits on top of your main chest muscle (pectoralis major) and is the organ that produces milk after a woman has given birth. Your breast is shaped like a tear drop, with the tail extending towards your armpit. It is made up of lobules which contain milk-producing glands. These glands are connected by ducts which carry milk to the nipple. The ducts and lobules are surrounded by fat and connective tissue which give the breast its shape.

The breast has a network of blood vessels which supply nutrients and oxygen to the tissue, and a network of lymph vessels which drain fluid and waste products from the breast. The lymph vessels are connected to the lymph nodes (also known as glands) in your armpit.

Cells are the building blocks of your body. They divide to make more cells so your body can grow, heal and repair itself. All cells in the body have a series of checkpoints to identify and destroy abnormal cells. Cancer happens when a cell starts to grow in an uncontrolled fashion as a result of changes (mutations) in its genetic make-up which damage the normal checkpoints. This cancerous cell can now divide without restrictions, form a mass called a tumour or a cancer, and move around the body.

Breast cancers develop from the cells in the ducts, lobules and connective tissue of the breast. Breast cancer first spreads through the lymph vessels to lymph nodes. The first lymph node in your armpit that your cancer spreads to is called the sentinel node. Breast cancers are normally slow-growing (although there are exceptions), and it can take several years for one cancerous cell to become a mass that can be seen on a mammogram or that you can feel.

Initially, breast cancer cells don’t have the ability to move around the body and ‘invade’ your lymph nodes or other organs. These cancers are called ‘non-invasive’ (ductal carcinoma in situ or DCIS). Once the cells have developed the ability to spread, the cancer is called an ‘invasive’ breast cancer. (We explain these terms in more detail on 12–14.)

If you have primary breast cancer it means that your breast cancer hasn’t spread beyond the lymph nodes in your armpit, is treatable and can potentially be cured. Sometimes your cancer can come back in your breast, the surrounding skin or your chest wall, called a ‘local’ recurrence. Alternatively, your cancer may spread to your bones or organs, such as your liver, lungs or brain, and this ‘distant recurrence’ is known as secondary breast cancer (also called metastatic or advanced cancer). At the moment, there aren’t any treatments that can cure a cancer that has spread, but there are lots of treatments that can slow down the spread, prolong your life and help with any symptoms you may have (see Chapter 23 for more on this).

There are three ways that breast cancer may be suspected. If any of them happen to you, you will be referred to your local breast unit for further tests.

The most common change is finding a lump in your breast. However, you may notice a rash on your nipple or breast, thickening, puckering or dimpling of the skin, in-drawing of your nipple or bloody discharge from your nipple. You may also have felt a lump in your armpit. Very rarely, you may notice an ulcer on your breast which is caused by a breast cancer that has grown through the skin (called a ‘fungating’ cancer). If you have any of these changes, you should see your GP for an urgent referral to your breast unit.

In the UK, women between the ages of 50 and 70 are invited to have a mammogram (breast X-ray) every three years through the National Breast Screening Programme. Your mammogram might show something that needs further investigation, and this can sometimes be an early breast cancer.

You may have had a scan or a test to investigate another medical problem which showed either a cancer in your breast, or evidence of secondary cancer, such as a broken bone or a nodule in your liver. It is uncommon to find breast cancer in this way.

Breast cancer is diagnosed using a ‘triple assessment’: an examination by a doctor or nurse, imaging (X-rays and/or scans) of the breast and armpit, and a biopsy of any suspicious areas. These should all happen during your first visit to the breast unit, but sometimes your biopsy may have to be done a few days later.

You will be seen by a doctor or nurse in the clinic. They will ask you about any breast changes, your family history of breast and ovarian cancer, and any medical conditions you might have. They will then examine your breasts and armpits, and, if they are concerned, will arrange for you to have some scans.

The standard tests are a mammogram and an ultrasound scan (abbreviated as ‘USS’) of any lump or area of concern. If you are younger than 40, mammograms are not routinely done and you may just have an ultrasound to start with; mammograms are hard to interpret in young women because their breasts are dense. If the radiologist sees a suspicious area in your breast, you will also have an ultrasound scan of your armpit to look at the lymph nodes.

A small tissue sample called a ‘biopsy’ (technically a ‘core biopsy’) will be taken of any suspicious area in your breast or armpit. This is normally done at the same time as your ultrasound. It doesn’t take long to do, and a local anaesthetic is used to numb the area first. It may feel a little uncomfortable, but it shouldn’t hurt (though areas closer to the nipple are more sensitive). If the suspicious area is seen only on a mammogram, your biopsy will be taken using a special mammogram machine. You may feel that the lump has got bigger after the biopsy. This is due to swelling and bruising in the breast and is quite normal. If you have a rash on your breast or nipple, your doctor may take a very small skin sample called a ‘punch biopsy’. Your biopsy will be examined by a pathologist to find out what type of breast cancer you have (see Chapter 3, here).

After the core biopsy, you may have a small gel clip inserted into the cancer that can be seen on future scans. There are two reasons for doing this:

1. If your cancer can’t be felt, the clip guides your surgeon during your operation (see here).

2. If you are having chemotherapy before surgery, your cancer can shrink and sometimes disappear. The clip will guide your surgeon, so they know which part of your breast to remove.

Non-invasive breast cancer (ductal carcinoma in situ or DCIS) develops in the cells of the breast ducts. This cancer does not have the ability to spread to other parts of your body. There are three grades (low, intermediate and high) which describe how close the DCIS is to becoming an invasive cancer. If DCIS isn’t treated, it may develop into an invasive cancer in the months or years ahead. This is more likely to happen if your DCIS is intermediate- or high-grade, which is why surgery is recommended for it. At the time of writing, there are currently several trials investigating the treatment of low-grade DCIS to compare monitoring (‘wait and see’) with the standard surgical treatment, so national treatment guidelines for this kind of DCIS may change in the future.

Invasive breast cancer has the potential to spread to other areas of the body. There are several different types, depending on which cell in the breast the cancer has grown from:

This accounts for 80 per cent of all breast cancers worldwide and develops from the breast ducts. It is also called NST (no special type) or NOS (not otherwise specified). It develops from cells in the milk ducts and is usually easy to see on a mammogram. There are some uncommon special types of invasive ductal cancer (tubular, medullary, mucinous, papillary and cribriform) that develop from specialised cells in the milk ducts. These are usually slow-growing and have an excellent prognosis. (‘Prognosis’ is an estimate of the likelihood that your cancer will come back. An excellent prognosis means that there is only a small chance that this will happen.)

This accounts for 15 per cent of all breast cancers worldwide and develops from the breast lobules. It can be difficult to feel clinically and to see on a scan because the cells grow in sheets instead of forming a cluster like the invasive ductal cells. There are two types of lobular cancer. Classic lobular cancer is the most common type and is slow-growing. Pleomorphic lobular cancers are faster growing and can have a worse prognosis.

This is a combination of ductal and lobular cancer cells and is usually treated like invasive ductal cancer.

This is a rare, aggressive form of breast cancer that looks like a breast infection (mastitis). Cancer cells block the lymph vessels in the breast and skin so the breast is warm, red and swollen.

This is a rare cancer that affects the cells of the nipple ducts, the surface of the nipple and the areola (the darker area around the nipple). The nipple develops a red and scaly rash which can become an ulcer and destroy the nipple. Most women with Paget’s disease will also have DCIS, and some will have invasive breast cancer as well.

This is a very rare cancer that develops from the connective tissue in the breast. Most are benign (non-cancerous) but a small number can be malignant (cancerous). It rarely spreads to other parts of the body, and it is unlikely you will need any further treatment after your surgery.

WHAT HAPPENS IF YOUR DOCTOR CAN’T FIND YOUR BREAST CANCER?

If you notice a lump in your armpit and a core biopsy shows breast cancer cells, your surgeon will arrange for you to have a mammogram and ultrasound scan. Sometimes, these scans don’t show a cancer in your breast. In this case, you will have an MRI scan, but sometimes this can also be normal. If the cancer in the breast can’t be found, you will have surgery to remove your involved lymph nodes, with either a mastectomy or radiotherapy to the whole breast, probably followed by chemotherapy.

WHAT HAPPENS IF YOU HAVE SECONDARY BREAST CANCER WHEN YOU ARE DIAGNOSED?

In around 1 in 20 people with breast cancer, the cancer has already spread to other parts of the body when it is diagnosed (see Chapter 23). This may be devastating if it happens to you, and you and your doctors will have lots of decisions to make regarding how to treat your cancer. With primary cancer, the main treatment is surgery to remove the cancer. However, once your cancer has spread, the aims of treatment are to control the cancer (slow down or stop it spreading further), and to relieve any symptoms you have. This normally involves a combination of chemotherapy, hormone and targeted therapies, and most women have treatment for many months or years. Breast surgery itself becomes less important because the cancer has already spread, and your surgeon and oncologist will talk to you about whether you should have an operation.

In the UK, you have two treatment options. You can stay with the National Health Service (NHS) or have your treatment in the private sector (either through an insurance policy or paying yourself). If you’re not already privately insured when you get breast cancer, you can’t take out insurance to cover your treatment.

The NHS is fantastic when it comes to treating breast cancer. It has strict time targets so that everyone suspected of having cancer must be seen within two weeks. Your GP normally refers you to your local breast unit, but you can ask to be sent to a different hospital if you prefer. One of the breast team will see you, and you will be allocated to whichever surgeon is working in the hospital on the day you get your results. A different surgeon may then do your operation, together with his or her trainees. The NHS is a teaching environment, and junior surgeons will be supervised by your consultant while they perform certain parts of your operation. If you do want to be seen by a specific surgeon you can ask to see them personally, but it’s not always possible (for example, they may be on holiday). Once you’ve been diagnosed with cancer, it is recommended that you start your cancer treatment within 31 days from your diagnosis, whether this is surgery or chemotherapy.

Although the NHS is great, there are some benefits to private treatment:

● You can choose which surgeon you see.

● You will get more time with your surgeon in clinic appointments.

● You will probably get a nicer room in hospital.

However, it can be hard to know which surgeon to choose. If you wish to have your treatment privately, look at private hospital websites. Your GP may be able to recommend a private surgeon, and you can always ask your NHS surgeon whether they do private work.

Having private treatment should not change which treatments you have. Every breast surgeon should follow the same national guidance (see Chapter 6), whether they are working in the NHS or the private sector. If a private surgeon is offering you something radically different from what you’d get on the NHS, you should be wary. Private doctors are not as closely scrutinised as those in the NHS. If in doubt, discuss things with your GP.

Liz had all her treatment on the NHS, while Trish was treated privately through a personal insurance policy. The treatment Trish had privately was exactly the same as she would have had on the NHS, but she was reassured that her consultant surgeon would do her operation without trainees being involved. There were also some comfort advantages (she got a single room in the hospital and the chemotherapy unit had its own chef).

Breast cancer treatment is planned on an individual basis, because every patient is different. Below we introduce the different professionals and explain how they work together to plan and deliver your treatment.

If you have cancer treatment on the NHS, your case will be discussed with a team of doctors and nurses at a multidisciplinary team meeting (also called an ‘MDT’). In the US, this team is called a ‘Tumor Board’. The MDT makes sure that your diagnosis of breast cancer is accurate, agrees a treatment plan (taking into account your type and size of cancer, whether it has spread and your general health) using the latest evidence-based guidelines (explained in Chapter 3), and discusses any research trials that might be relevant to you (see Chapter 6). If you are being treated privately, your surgeon should use an MDT as well. The key people in an MDT include:

Breast surgeons are doctors who specialise in breast surgery. A consultant is the most senior surgeon who has finished all their specialist training.

Plastic surgeons are surgeons who specialise in repairing or reconstructing missing tissue or skin, like a breast reconstruction. Your breast surgeon may work together with a plastic surgeon if you need a breast reconstruction (see Chapter 8). They normally only get involved in MDTs in larger hospitals, as most small hospitals don’t have plastic surgeons on site.

Breast radiologists are doctors who specialise in looking at breast and body scans. Radiographers are specially trained technicians who do mammograms and ultrasounds.

Breast pathologists are doctors who specialise in looking at breast tissue under the microscope and they write your pathology report (see Chapter 3).

Breast oncologists are doctors who specialise in treating primary and secondary breast cancer with chemotherapy, radiotherapy and Herceptin, and other targeted therapies. They will estimate your prognosis (see Chapter 3) and plan what extra treatment you need.

Radiotherapy specialists and radiotherapists are nurses and technicians who will give you information, help plan and deliver your treatment, and look after you during radiotherapy.

Breast care nurses and oncology nurses are specially trained to look after breast cancer patients. They work with the doctors in out-patient clinics and will look after you, give you information and offer emotional support. They are usually your first port of call if you have a problem and you should feel able to discuss any worries that you might have about your possible treatment plan with them.

The MDT coordinator makes sure that all the treatment plans agreed in the MDT are properly recorded, and that you have all your treatments promptly, according to the NHS cancer pathway targets (see Chapter 6). If you are having a second opinion, they will make sure that all your scans and reports have been sent from your first hospital.

It normally takes a week or two from the date of your biopsy for your results to be processed and discussed at the MDT. Sometimes, you may need to have further tests or biopsies before you can be treated. This could be another ultrasound scan to look at a different area in the breast, or an MRI scan. MRI scans are not done routinely, but may be needed if you have lobular cancer, very dense breasts or have cancer in your lymph nodes but no visible cancer on a mammogram (this is called an occult cancer).

It can take several weeks for these extra scans and biopsies to be performed and analysed, and it is hard not to feel anxious that the cancer is spreading. Remember that it can take several years for a breast cancer to grow, and it is more important for your team to get all the information they need so you can have the correct treatment, instead of rushing ahead and possibly missing something important.

One of the first things you should do after being diagnosed with breast cancer is make an appointment to see your general practitioner (GP). If you don’t have a GP, or if the GP you do have is not someone you feel you can approach, now is the time to find a good GP local to you and re-register. To find one, see the excellent NHS Choices website: www.nhs.uk.

Your surgeon will send your GP a letter telling them about your diagnosis within a couple of days. Your GP can prescribe any medication that you need to take, advise on minor side effects and negotiate with the hospital on your behalf if needed. Incidentally, having cancer means you are eligible for free prescriptions in the UK, so ask your GP for the relevant form to fill in.

Your GP is not a cancer specialist, but they may be a (relative) expert on you. They know your other medical conditions, how you have reacted to serious illness in the past, your family circumstances and your wider support networks. A good GP is an ‘active listener’, able to hear your story and help you make sense of what’s happening and help support your family. Some GPs are trained in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which can help a lot if you need to deal with anxiety and negative thoughts (see here). Most GP practices often have nurse practitioners (highly trained nurses) who may see patients and prescribe drugs and give injections like Zoladex (see Chapter 13).

The final person to mention is your dentist. If you are going to need chemotherapy or bisphosphonates to strengthen your bones, try to get a check-up before you start, as your body won’t tolerate drillings and fillings well during treatment.

Before agreeing to your treatment plan, you may want to see a second surgeon to get a second opinion. Your GP should be able to refer you to another surgeon, or you may choose to see someone privately. Before you see them, you must think carefully about your reasons for getting a second opinion. Do you want someone to tell you what you want to hear, even if it means getting a third or a fourth opinion? Or do you want another sensible opinion, and if that’s the same as your initial surgeon, will you then stick with the original treatment plan?

Everyone is entitled to a second opinion, but it could delay your cancer treatment. Your new surgeon must discuss your case in their own MDT which could take a week or two. In most cases, those extra couple of weeks will make no difference to your overall survival from breast cancer, but if getting your surgery as quickly as possible is your top priority, then getting a second opinion might not be in your best interests.

We cover all of the treatments described below in detail in further chapters, but here is a brief summary of which treatments you might be advised to have:

The main treatment for primary breast cancer is surgery (see Chapter 7). If you have invasive breast cancer, you will almost certainly be advised to have an operation to remove it. The two main operations are a lumpectomy (just the cancerous bit is removed) or a mastectomy (the whole breast is removed). If you need to have a mastectomy, your surgeon should discuss breast reconstruction with you (see Chapter 8).

You will also have an operation to remove one or more of the lymph nodes in your armpit – either a sentinel node biopsy or an axillary node clearance. If you only have DCIS, your cancer cannot spread to your lymph nodes, so you do not need to have your lymph nodes removed. The one exception is if you have a large area of DCIS and need to have a mastectomy – there is a small chance that you may have a small invasive cancer in your breast, and your surgeon will then remove a few lymph nodes at the same time as carrying out your mastectomy.

Chemotherapy is recommended if you have a high risk of developing secondary breast cancer in the future, and if you already have secondary breast cancer. It is normally given after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy), but, as we will explain here, your surgeon may recommend that you have it first (neoadjuvant chemotherapy). Chemotherapy drugs kill cells that are growing quickly, like cancer cells, but they also affect some of the normal cells in your body (see Chapter 10).

If your cancer is ‘HER2-positive’ (sometimes written as ‘HER2+ve’), you will be offered a drug called Herceptin which will greatly improve your prognosis. At the time of writing, Herceptin has to be given with chemotherapy. You may be given other drugs that also target HER2+ve cancers. If you have secondary breast cancer, you may be given one of several other drugs that specifically target breast cancer cell growth (see Chapter 11 for more details).

Radiotherapy is used to reduce the risk of a local recurrence – when your cancer comes back in your breast or chest wall and lymph nodes (see Chapter 12). Everyone who has a lumpectomy needs to have radiotherapy to treat the breast tissue left behind. You may also need it after a mastectomy or if you have cancer in your lymph nodes. Radiotherapy is also used to treat symptoms of secondary breast cancer, and for pain control.

If your cancer is sensitive to oestrogen (ER-positive, usually written as ‘ER+ve’), you will be given tablets to lower the levels of oestrogen in your blood and reduce the risk of your cancer returning in the future (see Chapter 13). If you are pre-menopausal, your oncologist may also discuss treatment to switch off your ovaries to further lower your oestrogen levels (see here).

Getting diagnosed with breast cancer can be very frightening, and you may feel like there is too much information to take on board. We know – we’ve been there. Once your diagnosis has started to sink in a little, one of your first questions may be, ‘How long have I got?’. In the next chapter, we’re going to tell you how your doctors estimate what your chances of surviving breast cancer are, and what additional treatments, on top of your surgery, you might need.