THE MOST EFFECTIVE treatment for breast cancer is an operation to remove it. There are two types of breast operation. Your surgeon will either remove the cancer and leave the rest of your breast tissue behind – called a ‘lumpectomy’ or ‘wide local excision’. The remaining breast tissue is then treated with radiotherapy. The other option is to remove all of your breast, including the cancer. This is called a ‘mastectomy’. If you need to have a mastectomy, your surgeon should discuss breast reconstruction with you, which is discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

Your surgeon may also need to remove some or all of the lymph nodes in your armpit. The first lymph node that your breast cancer spreads to is called the sentinel node (see here). Your surgeon may remove just the sentinel node or do a more extensive operation called an ‘axillary node clearance’. We explain the difference between these below.

If you have DCIS (non-invasive cancer), you don’t need to have any lymph nodes removed because your cancer by definition cannot spread. Most women with DCIS have only a small area of it, which can be treated with a lumpectomy. If you have a large area of DCIS and need a mastectomy, there is a chance that you might have a small invasive cancer area in the middle of the DCIS. If this happens, there is also a chance that your lymph nodes could contain cancer cells, and so your surgeon will do a sentinel lymph node biopsy at the same time as your mastectomy.

If you have invasive cancer, you will have either a lumpectomy or a mastectomy, as well as lymph node surgery.

If your cancer has grown through the breast into the skin (called a ‘fungating’ cancer), it can cause ulcers that bleed and smell. Your surgeon will do an operation called a ‘toilet’ mastectomy to remove the cancer and the affected skin. If you’re not well enough to have this operation, your doctors can try radiotherapy to treat it.

If you have breast cancer in your lymph glands but your doctors can’t find a cancer in your breast (an occult cancer), you will have an axillary node clearance, and either a mastectomy or whole breast radiotherapy.

If you have secondary cancer from the beginning, there is no urgent need to remove your breast cancer because it has already spread. You will probably start with a combination of chemotherapy, radiotherapy or hormonal therapy. Your team will monitor your breast cancer and lymph nodes during treatment, and talk to you about the pros, cons and timing of breast surgery.

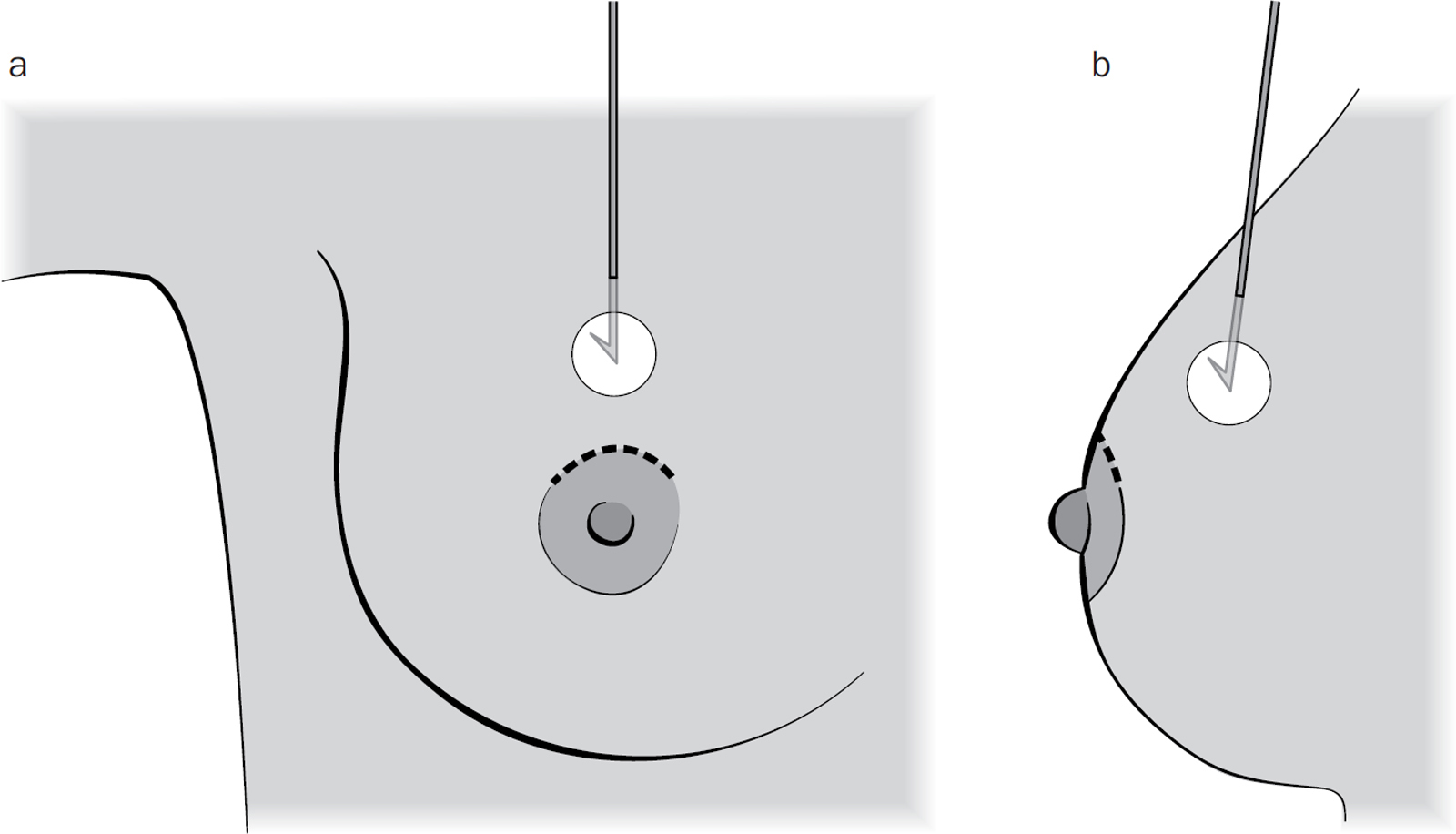

If your cancer was detected through breast screening, there may be no lump to feel. If your cancer doesn’t have well-defined edges, it can be hard for your surgeon to know exactly where it is. There are several methods that your surgeon can use to help find your cancer.

A radiologist will first put a small gel clip into the cancer (see here). Before your operation, a very fine guidewire is inserted into your cancer, next to the clip, using a local anaesthetic and either ultrasound or mammogram guidance. You will then have another mammogram to make sure that the wire is in the correct position. Your surgeon removes the tissue around the tip of the wire and then takes an X-ray to make sure that they’ve removed all the right area. There are alternatives to the wire, such as a radio-isotope (see here) and microscopic magnetic beads, and your surgeon will explain which technique they will use.

To make sure there are no cancer cells left behind, your surgeon will remove a rim of normal breast tissue, called a ‘margin’, around the cancer. When your cancer is analysed, the pathologist checks to make sure that the margin under the microscope is a minimum distance of 1–2mm between the cancer and the free edge – a ‘clear margin’. If there are cancer cells closer than 1–2mm from the free edge, you have a ‘positive margin’. The margin needs to be clear for further treatments, such as radiotherapy, to have the most benefit, so if you have a positive margin, you may need to have further surgery.

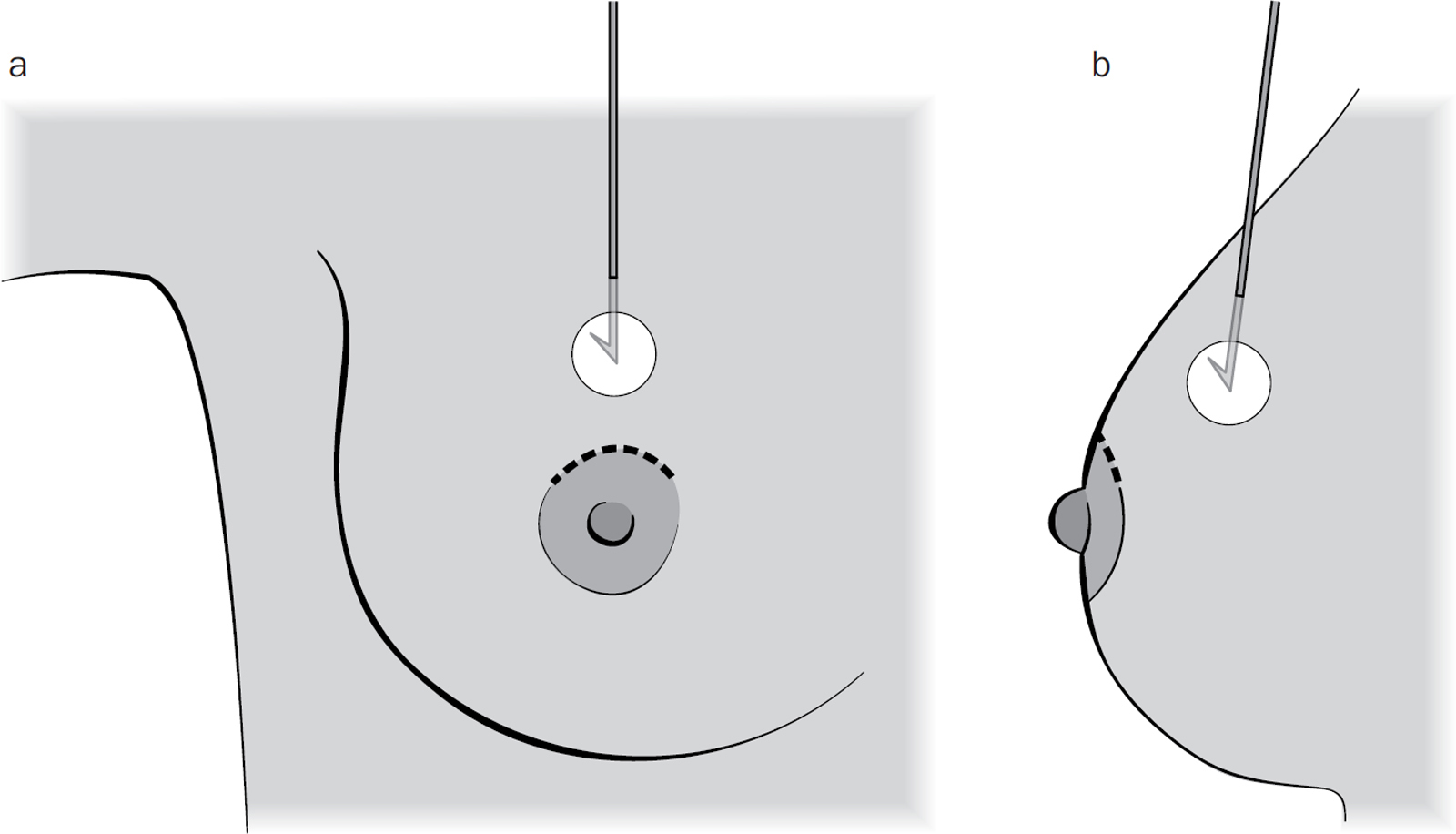

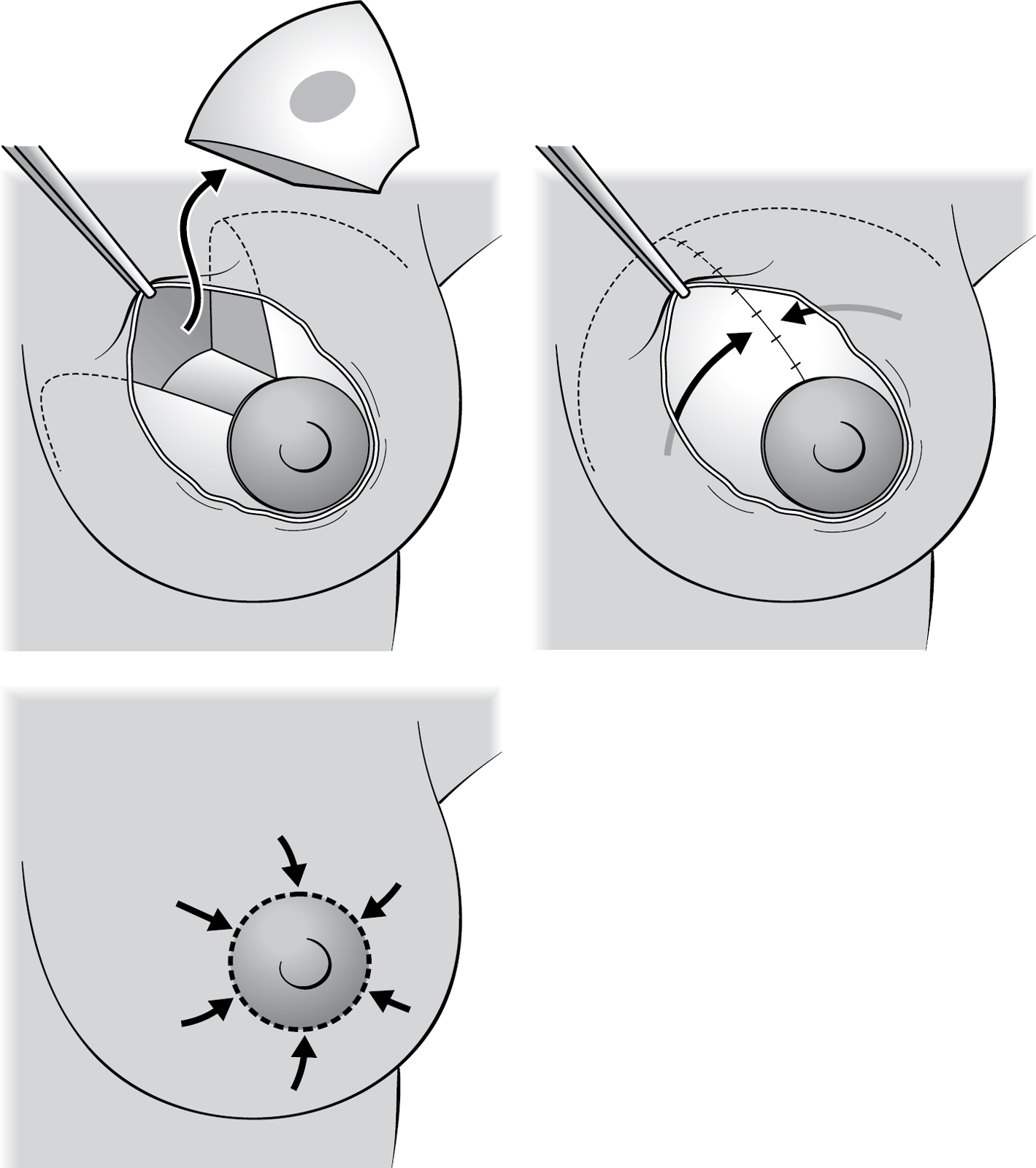

Over the last 10 to 15 years, breast surgeons have developed plastic surgery techniques to reshape, reduce and recreate breasts after cancer surgery to improve how your breast looks. This is called ‘oncoplastic surgery’ and is now taught to all new trainee breast surgeons. Breast surgeons can now hide your scar by placing it around your nipple or on the edge of the breast, making it hard to tell that you have had an operation. These techniques also mean that many women no longer need to have a mastectomy. For example, if you are small-breasted with a large cancer, your surgeon might be able to use some of your own fat or muscle to fill the gap left by the cancer. If you have very large breasts and a large cancer, your surgeon could offer you a breast reduction instead of a mastectomy.

The cosmetic outcome of each operation depends on the quality of your breast tissue and your skin. Your breast tissue needs to be firm enough, and your skin needs to be healthy enough, for your surgeon to use these new techniques. Ageing and smoking can affect both, and your surgeon will be honest with you about what is and isn’t possible. Most but not all consultant breast surgeons are now trained in oncoplastic surgical techniques.

This should be a joint decision between you and your surgeon. It’s made in two stages. First, the multidisciplinary team (MDT, see here) will review all of your results and make a decision regarding breast and axillary node surgery based on the size of your breasts and the size of your cancer. As a rule of thumb, a surgeon can remove a fifth of your breast and reshape it to give you a good cosmetic result. If they need to remove more than a fifth of your breast to safely remove the cancer, they will need to consider oncoplastic techniques to fill the gap or reshape the breast, or do a mastectomy, with the option of a reconstruction.

Your surgeon will see you in a clinic to give you your results and talk to you about your surgical choices. They may need to examine you again to properly assess your breasts (how firm or droopy they are, whether they are symmetrical) and the quality of your skin. They will also ask you whether you smoke and ask about any other medical conditions. Most people accept the MDT’s recommendation, but you can ask to have something different. You may be advised to have a lumpectomy and radiotherapy, but instead choose to have a mastectomy and avoid radiotherapy, like Trish did.

Your surgeon may not be trained to do some or all of the more modern oncoplastic procedures, which means you may need to see a different surgeon if this is something you want to consider.

The key questions you should think about are:

● If you’re offered a lumpectomy, would you rather have a mastectomy?

● If you’re offered a mastectomy, are there any alternative operations that mean you could keep your breast?

● If you’re offered a mastectomy, do you want to stay flat or explore breast reconstruction? (See Chapter 8 for more on this.)

It is your body and your choice. Below, we list some questions to ask yourself – and then (when you’ve had a think about those) some additional questions to ask your doctor.

The most important factor should be getting your cancer treated properly. Although how your breast looks afterwards is important, your life should come before your looks.

Your breasts are sisters, not twins. One breast is always a bit bigger or droopier than the other. There’s no polite way of describing a breast that has ‘headed south for winter’, but the technical term is ‘ptosis’. Your nipples may even be at different heights. Your surgeon will try to match what you already have, but they can never promise perfection.

Your breasts can define your identity as a woman. You may love them or hate them, wish for bigger or smaller ones, flaunt them or hide them away. They may be incredibly important sexually or they may have very little feeling and you can’t see what all the fuss is about. You may have loved your breasts as a young woman, but now you’ve raised a family, you’re not that bothered about them. It’s also hard to think rationally about them when you’re dealing with a breast cancer diagnosis but knowing how important your breasts are to you can help you decide what to do.

In an ideal world, would you like to look good in clothes, in your bra or naked? You may opt for a quick, simple operation and be happy to wear a small prosthesis in your bra to make you look symmetrical in clothes, or you may choose a longer, more technical operation to try to look symmetrical naked.

Ask your surgeon to show you ‘before’ and ‘after’ medical photographs of patients who have had the operation you’re considering. If a surgeon shows you a good result and you think it’s great, then you’re both on the same wavelength. If a surgeon shows you a good result and you think it is awful, you may have to lower your expectations.

If your breast appearance is important to you and you’re having a lumpectomy, it’s normally possible for your surgeon to hide the scar, for example by placing it at the junction of the nipple– areola complex and the breast. However, this might mean that you lose some nipple sensation. If you’re not bothered, they can just cut down directly over the cancer and still leave you with a good result. Breast skin scars can occasionally widen and thicken (hypertrophic scars), and this is more common after a breast reduction. Women of African ancestry are more prone to developing bulky (keloid) scars which extend onto the rest of the breast and can be very difficult to treat. If you have ever developed a thickened scar in the past, mention it to your surgeon.

If you are planning on having children in the future and breastfeeding is important to you, you need to factor this in. You can’t breastfeed after a mastectomy because the breast tissue has been removed. Most women can still breastfeed after a lumpectomy unless they have had a breast reduction.

If you want to return to work, childcare or sport as quickly as possible you might opt for a simpler operation with a shorter recovery period in order to achieve this. Surgeons initially make decisions based on your tumour size and your breast shape. They tend to want to give you a good cosmetic result as well as removing the cancer, and this may require a lengthy operation with a long recovery period. However, the surgeon isn’t the one who has to live with the effects of the surgery, so you need to speak up and let them know what is important to you. Never feel bad about asking for something simpler than the surgeon is proposing.

The shape of your operated breast will probably change as the years go by. Radiotherapy fixes a breast in time and place. This means that as your natural breast gets bigger or smaller as you gain or lose weight, or starts to droop as you get older, the cancer side won’t change to match it. You may also develop dents in the breast where the cancer was. There are surgical options that you can try to improve the appearance, such as ‘lipofilling’ (see here) and your surgeon will be able to talk to you about them if you are interested in further surgery.

Removing your healthy breast will not improve your prognosis from breast cancer and it will not stop it coming back in the future. It is the cancer being treated now, not a cancer you might get in years to come, that affects your survival from breast cancer. You should also remember that any chemotherapy or hormonal therapy you have is treating all of you, including your healthy breast, which further reduces the chance of you developing a second cancer in your other breast. However, if you have a BRCA mutation, your surgeon may discuss removing your healthy breast because you still have a very high chance of getting a cancer in your other breast in the future.

The other reason to operate on your healthy breast is to make your breasts more symmetrical. If you have large breasts and your surgeon has suggested a breast reduction, you can ask about having a reduction on the other side. While this is a very rewarding operation for both you and your surgeon, it does mean longer surgery with a longer recovery time. Your surgeon will also need to factor in the effects of radiotherapy to the cancer side (which can shrink the treated breast and alter the final appearance), and they may suggest waiting to reduce your normal side until after you have finished radiotherapy. You can wear a small prosthesis in your bra in the meantime.

A small number of women who have had a simple mastectomy ask to have their healthy breast removed for symmetry so they are flat on both sides. Removing healthy tissue is not something that a surgeon will rush into lightly, and it may take many months or years to come to a decision that neither you nor your surgeon will regret in the future. The initial emotions you feel at the time of diagnosis may be completely different to those you feel in six to twelve months’ time. Your surgeon may also need to check that they can get the funding to do this on the NHS, as this is technically not a cancer operation.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOUR SURGEON

● What operation do you recommend, and why?

● Do I definitely need the operation? What happens if I don’t have the operation? What are the alternatives?

● How much experience have you had? Have you had oncoplastic training?

● Are there any other operations I could have that you haven’t been trained to do that might be suitable?

● Where will the scar be?

● Will I have a drain?

● Can I see photographs of patients who have had the same operation?

● I don’t want to have radiotherapy. Can I have a mastectomy instead of a lumpectomy?

● How long will I be in hospital for?

● How long will it take me to get back to normal/recover?

● How much time off work will I need?

● When will I be able to drive?

Most surgeons will do everything they can to help you get a good result. Sometimes, though, they need to compromise on the appearance of your breast so they can treat the cancer properly. Smoking and vaping, for example, narrow the blood vessels in your body so your breast and skin don’t get as much blood as a person who doesn’t smoke. More complex operations, such as a breast reduction, carry a far greater risk of complications and your surgeon might not want to take that chance. If you have medical problems that affect your heart and lungs, such as very high blood pressure or emphysema, the risks from a long general anaesthetic are higher, and your surgeon may guide you towards a quicker, simpler operation.

You will be offered this operation if your cancer is small compared to the size of your breast. An incision is made in the skin, and the cancer is removed with a margin of normal breast tissue. Your surgeon may then move and stitch the remaining breast tissue to close the gap. The skin is normally closed with dissolvable stitches that lie underneath the skin, followed by a waterproof dressing so you can shower afterwards. This is a short operation, and you will go home either the same day or within 24 hours.

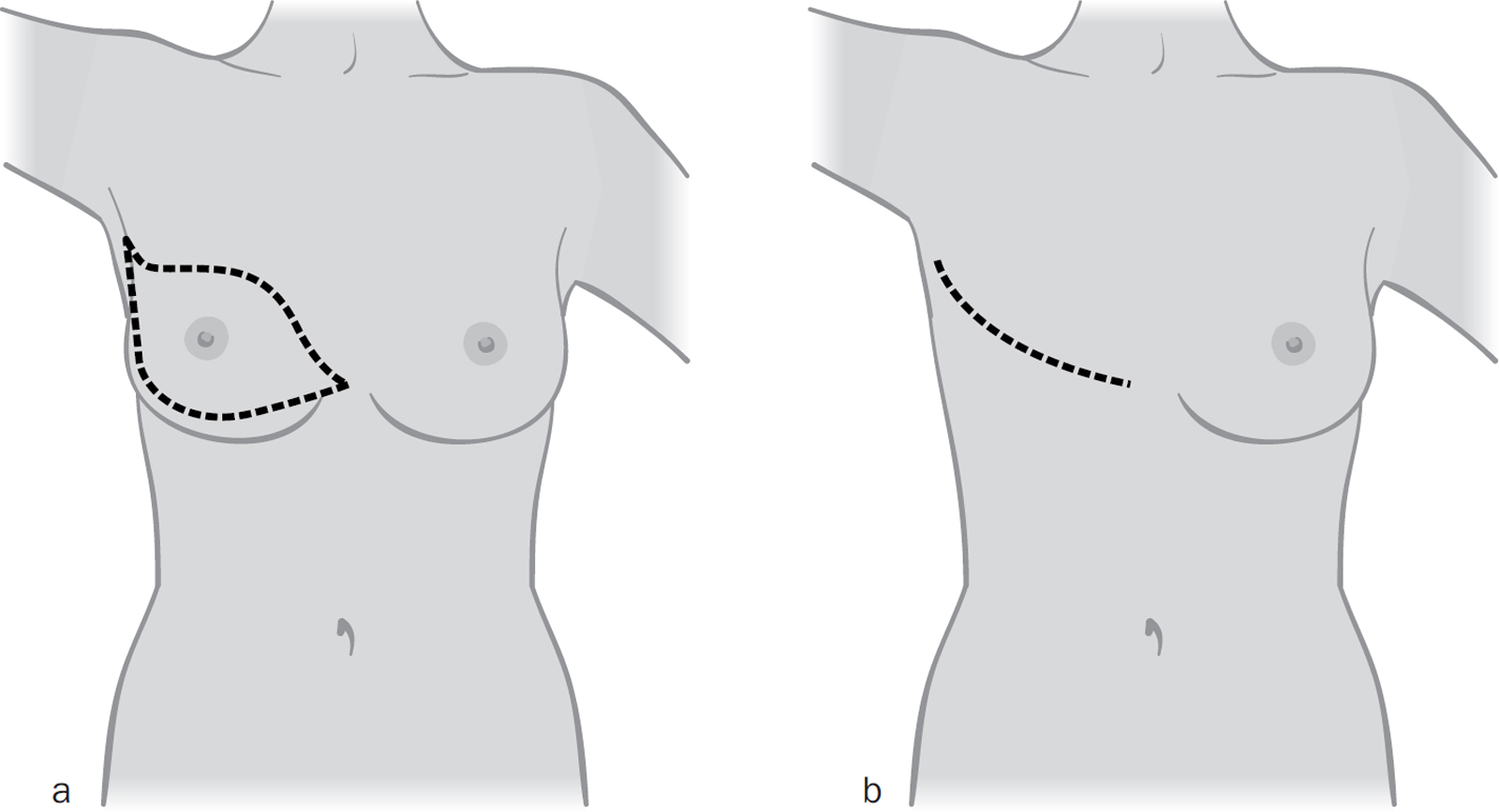

If you have a large cancer in a very large breast, your surgeon can remove up to half of your breast tissue (including the cancer) and skin and reshape the remaining tissue to create a smaller breast. Your surgeon can’t promise you an exact cup size, but most women having breast reduction end up with a C–DD cup. It takes several hours and you may stay in hospital overnight.

There are several different scar patterns. The most common approach is called a ‘Wise pattern’ which is like an anchor that also goes around the nipple. Most women having this operation lose some or all of their nipple sensation, and there is a small chance that you might lose the nipple itself because of problems with wound healing and poor blood supply. Your breast will be quite swollen for several months afterwards.

If you have a large tumour in a small breast, your surgeon can use some of your own tissue (a ‘mini-flap’) to fill the gap so you don’t need a mastectomy. They use fat from either your back (TDAP or Thoracodorsal Artery Perforator flap) or your side (LICAP or Lateral Intercostal Artery Perforator flap), and you will end up with one long scar extending from the breast onto your chest wall. The operation is sometimes done in two stages. At the first operation, your surgeon simply removes the cancer. Once your results come back and they know that the margins are clear, they will do a second operation a few weeks later to fill the gap in the breast with the flap. This operation takes several hours and has a longer recovery time than a standard lumpectomy. You will be advised not to lift anything heavy for two to three months, and this might not be practical if you are very active or have small children.

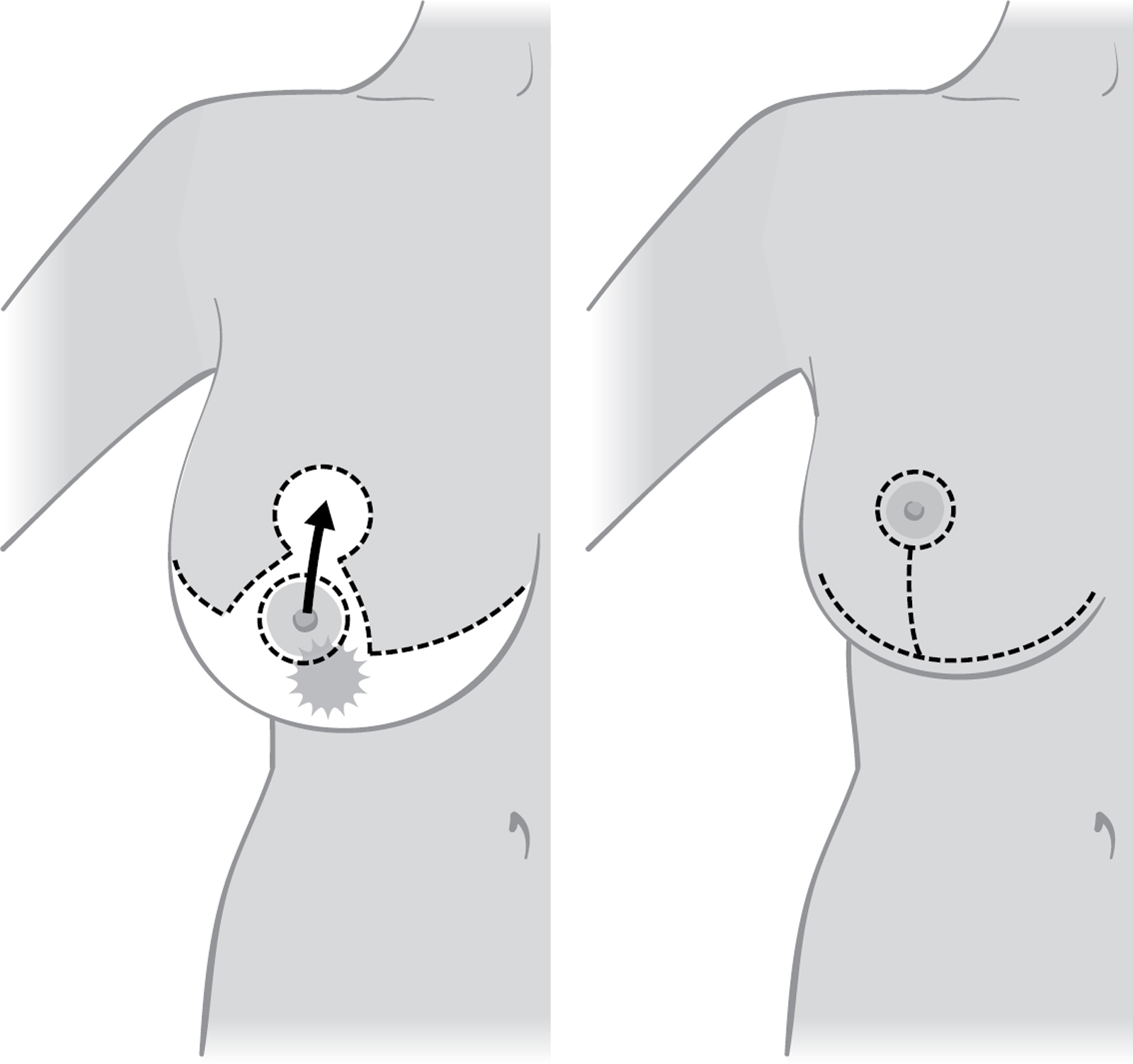

If your cancer involves the nipple or lies directly beneath it, your nipple has to be removed as part of the cancer operation. If your breasts are large enough, your surgeon might be able to rotate some of your breast tissue and skin to fill the gap, followed by a nipple reconstruction at a later date if you want one (see Chapter 8 for more on this). If you have small breasts, you can either have a lumpectomy (leaving you with a scar in the middle of your breast where your nipple was), or a mastectomy with a reconstruction if you prefer.

A mastectomy means removing all of your breast tissue together with the breast skin and nipple, leaving you with a low, curved scar on your chest wall. Your surgeon will try to streamline the scar, but you may be left with a small ‘dog-ear’ that can be neatened up at a smaller operation in the future. The skin is normally closed with dissolvable stitches that lie underneath the skin, with a waterproof dressing on top. Many women have a ‘cuddly bit’ at the edge of the breast that blends into the skin and fat of your back that you don’t normally see because the breast hides it. When the breast tissue is removed, it may be very noticeable when you look in the mirror.

After your mastectomy, you will be given a soft cotton temporary prosthesis to put in your bra until the skin underneath has fully healed. This can move around because it is so light, so you may want to use a safety pin to attach it to your bra. After six to eight weeks, your breast care nurse will arrange for you to be fitted for a more permanent prosthesis. These are made of silicone, and come in different shapes, sizes and colour tones, with or without a nipple. If you were treated privately, you may have to pay for a prosthesis from a department store or specialist supplier. Alternatively, you could ask your GP to refer you to an NHS prosthetic fitting service at your local breast unit.

Some complications, such as loss of nipple sensation and asymmetry between your breasts, are unavoidable because of the techniques your surgeon uses. Asymmetry can develop several months or years later because of radiotherapy, weight loss/gain and the ageing process.

The most common side effect after breast surgery is a seroma. This is a collection of tissue fluid in the space where you had your surgery, and the fluid does not contain cancer cells. Everybody produces some seroma fluid which is normally absorbed over several weeks. You may, however, produce a lot of fluid which can make your breast feel tight and uncomfortable. If this happens to you, tell your breast care nurse and they will arrange to drain the fluid in the breast clinic using a needle and syringe. This doesn’t normally hurt, because they drain the seroma through the scar which is numb.

There is a small chance that you will get a wound infection. The risk is greater if you are having more complex surgery, such as a breast reduction, or if you have diabetes or smoke. You may be given a short course of antibiotics to reduce the risk of you getting an infection.

There is a small chance that you might bleed after the operation. This can happen in the first couple of hours after you wake up and may mean you will need another small operation to stop the bleeding. Alternatively, you might develop a blood clot inside the breast over the next couple of days. This can usually be drained in the clinic, but you might need another small operation to remove it.

If you have a mastectomy, there is a small (15–30 per cent) chance that you will be left with chronic pain after your operation, and this can be permanent. It is called post-mastectomy pain syndrome (PMPS) and we don’t know why it happens. You may have a burning or a tingling sensation in the skin on the chest wall and upper arm. There are several different types of painkillers that can be used to treat this, and your surgeon and GP will be able to help you.

Your armpit is also called your ‘axilla’. You will be advised to have one of two operations, depending on the results of your triple assessment (see Chapter 2 and here).

If the ultrasound scan of your armpit was normal, your surgeon will remove the first node that breast cancer spreads to (the sentinel node) to make sure that it doesn’t contain cancer cells. Even though your nodes looked normal on the scan, there is still a 20–30 per cent chance that there might be tiny cancer deposits which are too small to see.

Two techniques are used to find the sentinel node (some surgeons use just one and some use both together). The first technique uses a small amount of a radioactive tracer liquid which is injected into your breast, normally on the day of your operation. The liquid gets trapped in the sentinel node and your surgeon uses a probe to find it. You are not radioactive after the operation, and it is safe for you to be around your family. The total amount of radiation that you receive is tiny (less than you get from the environment over a three-month period).

The second technique uses a small amount of blue dye which is injected near your nipple while you are asleep. This fluid is also carried in the lymph vessels to the nodes and stains them blue so your surgeon can easily see them. Your surgeon removes all the radioactive nodes and/or all the blue nodes – normally one to three in total.

Newer techniques are being introduced, such as magnetic microscopic beads and fluorescent dyes. Your surgeon will explain these to you if they plan to use them.

The sentinel node biopsy is normally done through a small scar just below the hairline in your armpit, but sometimes your surgeon can remove the node through your breast scar. If you are having a mastectomy, the surgeon will use the mastectomy scar to remove the node.

Some breast units have a machine that can analyse your sentinel node for cancer cells in real time while you’re having your operation (OSNA, or One Step Nucleic Acid Amplification). If the node is positive, your surgeon can remove the rest of your armpit lymph nodes while you are still asleep, instead of having another operation a few weeks later.

If your triple assessment showed that you have cancer cells in your lymph nodes, your surgeon will remove most of the lymph nodes in your armpit. This is called an axillary node clearance. There are three levels of nodes in your axilla. Level I nodes are low in your armpit, Level II nodes are higher up, and Level III nodes are higher still, next to the major blood vessels and nerves that supply your arm. Your surgeon will normally remove all the nodes in Levels I and II (10–20 in total). Level III nodes are not routinely removed because of the much higher risk of developing side effects, such as lymphoedema (see here) and because removing these nodes does not improve your prognosis.

The axillary node clearance operation is done through a scar below the hairline in your armpit. If you are having a mastectomy, it is done through the breast scar.

Seromas, wound infections and bleeding (described here and here) can also occur in the armpit. You will probably be told not to lift anything heavy for the first couple of weeks, to allow the wound to heal and reduce the chance of these problems occurring.

If you have a sentinel node biopsy, the skin around your nipple will be stained blue from the dye. This normally fades over a few months, but it can last for up to a year. The dye may also turn your urine blue-green for a day or two, but this is nothing to worry about. There is a very, very small chance (2 in every 1,000 patients) of developing a serious allergic reaction to the blue dye, which normally happens during the operation while you are still asleep and can usually be treated with anti-allergy drugs, such as steroids and antihistamines.

Trish developed a small seroma in her armpit following her sentinel node biopsy. She had it drained twice but the fluid reaccumulated each time. Many months later, the seroma became infected (possibly because her immune system was low due to chemotherapy) and had to be drained in an operation. It took several weeks to heal but eventually Trish’s armpit felt normal again.

After either operation, you may notice a patch of skin on your upper inner arm that feels numb, like ‘pins and needles’. There is a nerve that runs between the nodes in your armpit which provides sensation to that patch of skin. Sometimes your surgeon has to stretch the nerve or cut it during surgery, and this causes the numbness. If the nerve was stretched, then the feeling will return over time. If the nerve is cut, then that patch of skin will be permanently numb.

In addition to the above, there are three specific complications following armpit surgery that can affect the use of your arm: shoulder stiffness, lymphoedema and cording. The risk of getting any of these is higher after an axillary clearance.

Your shoulder will feel sore and stiff after your operation. You should have been given a series of exercises to do that can also be found on the Breast Cancer Care website (see here). These start gently and build up as you get more movement in your arm. It is really important that you do them at least three times a day to help you get your movement and function back.

You may still have a stiff shoulder despite doing the exercises, and occasionally this can turn into a ‘frozen shoulder’. If your pain and stiffness isn’t getting better, you should see your GP. They may need to refer you to a physiotherapist or orthopaedic surgeon for further treatment.

Lymphoedema is when fluid collects in the soft tissues of your arm (and sometimes your breast) because the lymph vessels were cut during surgery when your surgeon removed the nodes, which causes your hand and arm to swell. After a sentinel node biopsy, your risk is 5–10 per cent (1 in 10–20) in your lifetime. After an axillary clearance, your risk is 25 per cent (1 in 4). It can take several years to develop, and there is no cure, which means that once you develop it, you will always have a swollen arm.

Your breast care nurse will tell you what signs to look out for, and there is detailed information on the Macmillan and Breast Cancer Care websites (see here). The first signs are swelling, tightness or discomfort in your fingers and hand, such as a ring or watch strap feeling tight, or long-sleeved clothing becoming hard to get on. If this happens, you should contact your breast care nurse who will refer you to your local lymphoedema unit.

To reduce your risk of developing lymphoedema, you should use your arm normally and continue to do your shoulder exercises. Regular exercise, such as swimming and walking, will help. Try to avoid gaining a lot of weight, as this increases the pressure on the lymphatic system and can lead to the development of lymphoedema.

There is no hard evidence to say that having blood or your blood pressure taken from your ‘at risk’ arm will definitely increase the risk of you developing lymphoedema. However, most doctors will still advise you to use the other arm where possible. Keep your arm moisturised, and use strong sunscreen on holiday, as sunburn can also increase the risk of developing lymphoedema.

After armpit surgery, you are more likely to get an infection in your hand or arm following a small cut or graze because you have fewer nodes to fight infection. This infection can then spread and become serious. The infection can also increase the risk of you getting lymphoedema. Use simple precautions like wearing gloves when gardening, using clean, fresh razors when shaving your underarms, and keep any cuts or grazes clean. If you think you might have an infection (the cut looks red, hot, swollen or is painful), see your GP immediately as you may need antibiotics.

Lymphoedema is treated in three ways: massage, compression and surgery. Massage involves a special technique called manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) to slowly move the fluid away from your swollen arm. It must be done by a trained lymphoedema therapist. They may teach you to do MLD yourself. The second treatment involves wearing a compression glove or a sleeve for the rest of your life, which reduces and prevents further swelling. The ones issued free on the NHS are skin tone in colour, but you can buy patterned ones online. New surgical techniques have recently been developed in Europe where lymph nodes from other areas in your body, such as your groin, are transplanted into your arm. These transplanted nodes are then able to help drain the fluid from your swollen arm. This operation may soon be available in the UK.

You could develop tight, rope-like structures called ‘cords’ that run from your armpit scar down your inner upper arm. Your arm will feel painful and tight, and the cords stop you being able to fully move your shoulder and get your arm above your head. We still don’t know why they form.

The first treatment is to continue with your shoulder exercises as the cords will often snap by themselves as you stretch your arm. This isn’t painful. You may feel a ‘pinging’ sensation or even hear a pop as they snap, followed by relief as you can suddenly move your arm. Lying on the side of your bed and letting your arm hang off the edge is often very effective, as gravity helps you get a better stretch.

When you have radiotherapy, you have to lie with your arms above your head so your breasts are in the right position to be treated. If cording means that you can’t get your arms above your head, your radiotherapy will need to be delayed. You may need to see a physiotherapist to help massage the area and snap the cords.

Cording happened to Liz, whose radiotherapy was delayed by three months as a result. Despite doing all the stretching exercises she still couldn’t get her arm above her head. After two sessions with a trained physiotherapist, she could fully move her arm again.

Your surgeon removes all the cancer they can feel, but sometimes there may be cells close to the margins that can only be seen with a microscope (in other words, you have a ‘positive margin’). Up to 4 in every 10 women need further surgery to get a clear margin. In rare cases, you may even need a third operation if the margins still aren’t clear. If you have small breasts or have had a breast reduction, your surgeon may need to do a mastectomy to get clear margins.

If your sentinel node biopsy was positive, your surgeon will discuss further treatment to the axilla. This may be a completion axillary node clearance, or radiotherapy (see Chapter 12) to the armpit at the same time as your breast radiotherapy.

If you have a visible defect after your surgery or radiotherapy and have enough fat, your surgeon can use your own fat to fill in the defect. Fat is harvested from your tummy or thighs, cleaned and then injected into the breast. You may need several operations to get a good result. Lipofilling does not increase the risk of the cancer coming back.

If your cancer comes back as a nodule in the skin, your surgeon will remove the nodule with a rim of normal tissue around it. If your cancer comes back in your breast after a lumpectomy, your only option is a mastectomy. This is because you have already had radiotherapy, and you cannot have radiotherapy again. Surgery to the breast and armpit is quite complicated as every breast is different and every patient is different, so there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ operation. We hope that you’ve now got a better understanding of why your surgeon has recommended a specific operation to you.

If you need to have a mastectomy, your surgeon should talk to you about having your breast reconstructed. This is even more complicated and can take two or three consultations with your medical team to come to a final decision. We guide you through all the various options in the next chapter to help you decide what to do.