8Working capital and liquidity

THIS CHAPTER CONCENTRATES on the ways of assessing the short-term financial position and health of a company. Although the terms solvency and liquidity are often used to refer to the same thing, each focuses on a different aspect of financial viability. Solvency (discussed in Chapter 9) is a measure of the ability of a company to meet its various financial obligations as they fall due, whether they are loan repayments or creditors’ invoices. Liquidity is directly related to cash flows and the nature of a company’s short-term assets; that is, whether there is an appropriate amount of cash on hand or readily available. You may have $1m invested in stocks and shares but not enough cash in your pocket to buy a bus ticket. You may be solvent but far from being liquid.

A simple check on the short-term financial viability of a company might be first to make sure a profit was made for the year, and then turn to the statement of financial position to see if there was a large cash balance at the end of the year. If the company made a profit and shows positive cash balances, you might think all is surely well. Unfortunately, you might be wrong; positive cash balances at the year end, even when combined with profit, do not guarantee corporate survival in the short term, let alone the long term.

The statement of financial position is a snapshot of a company’s assets and liabilities at the end of the financial year. It does not claim to be representative of the position during the rest of the year. The income statement matches income and expenditure for the year. Income, and therefore the profit for the year, includes credit sales income and credit expenditure as well as cash transactions. A company might show a profit for the year but have numerous creditors, perhaps its major supplier of raw materials, requiring payment in cash within the next few weeks. It is also possible for a company to manipulate the year-end cash position. If towards the end of the financial year the company puts more emphasis and effort into collecting cash from customers and slows payment to creditors, this will result in an increase in cash balances.

Creditors provide finance to support a company and debtors tie up its financial resources. A company extending more credit to its customers than it, in turn, can take in credit from its suppliers may be profitable, but it is also running down its cash resources. This is called overtrading and is a common problem among small and rapidly growing companies. It is crucial for any business to maintain an adequate cash balance between credit given to customers and credit taken from suppliers.

Working capital and cash flow

The relationship between short-term assets and liabilities was discussed in Chapter 2. Current liabilities are set against current assets to highlight net current assets or net current liabilities. The net current assets figure is often referred to as the working capital of a company to emphasise the fact that it is a continually changing amount.

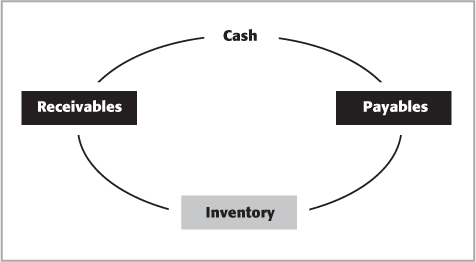

Current assets and liabilities change not only from day to day but also from minute to minute as a company conducts its business. Cash is used to pay the invoices of suppliers for the production of goods that are then sold, usually on credit, to customers, who in return pay cash to the company. The cash cycles around the business on a continuing basis (see Figure 8.1). On each turn of the cycle the company makes a profit, the goods or services being sold for more than the cost of their production, resulting in more cash available to expand the business and for the purchase or production of goods for sale.

The key to a company’s short-term financial viability is to be found in the study of working capital. Current assets consist of cash or near-cash items listed under four main headings: inventory (or stock), prepayments, receivables and cash. In the standard balance sheet presentation these are set out in order of liquidity, with cash being the ultimate form of liquidity:

- Inventory – finished goods, work in progress, raw materials

- Accounts receivable (debtors) – trade and other

- Prepayments – advance payment of expenses

- Cash – cash and bank balances, short-term deposits and investments

Inventory

The least liquid current asset is inventory (stock). When inventory is sold to customers, it moves up the current asset liquidity ranking to become part of accounts receivable and lastly to become completely liquid as a part of cash and bank balances when customers pay their invoices.

For many companies the total figure for inventory in the balance sheet is further subdivided in the notes to give the amounts held as raw materials, work in progress and finished goods. For practical purposes it is safe to assume that finished goods represent a more liquid asset than work in progress, which, in turn, is likely to prove easier to turn quickly into cash than raw materials.

Most companies can be expected to sell their inventory and turn it into cash at least once each year. If this is not the case, there should be a good reason for the company to hold that item or amount of inventory. If inventory is not turning into cash, valuable financial resources are being tied up for no immediate profitable return.

Receivables

After inventory, the next item appearing within current assets is receivables. These are divided into receivables where the cash is expected to be received by the company within 12 months of the balance sheet date and those where the cash is expected later. Often it is necessary to refer to the notes to discover the precise make-up of the total figure.

If a group of companies is being analysed, the amount disclosed for receivables may include amounts owed by subsidiary companies. These are also divided into the amount due within one year of the balance sheet date and the amount due later.

It is reasonable to assume that receivables due within one year are mainly trade receivables; that is, customers owing money for goods or services provided during the year and expected to pay the cash due to the company under the normal terms of trade. If customers are offered 30 days’ credit, they are expected to pay cash to the company within 30 days of accepting delivery of the goods or services provided.

To give the impression of income growth, a company may pursue a creative approach to sales revenue recognition – for example, counting future income in the current income statement. That something is amiss will be indicated by the much greater growth in trade receivables than in turnover. A company may opt to push inventory out to dealers on a sale or return basis and treat this as sales revenue for the year. In effect, the company is turning inventory into receivables. The income statement will show revenue and profit increasing, but there will be a mismatch evident when the growth trends of inventory and debtors are compared.

% increase in sales revenue compared with % increase in accounts receivable

Faced with an unacceptably large level of credit extended to customers, a company may factor or securitise trade receivables (see Chapter 2). This will result in a reduction in the level of receivables shown in the balance sheet – the true level is disguised. Always read the notes provided in the accounts for trade receivables. For a normal, healthy company, the growth in levels of turnover, inventory and trade receivables can be expected to be compatible. Any significant differences should be studied.

Receivables shown in the balance sheet may be assumed to be good debts. Customers owing the company money are expected to pay their bills when they fall due. Any known or estimated bad debts will have been written off through the income statement. Bad debts can be either deducted from sales revenue to reduce income for the year or charged as an expense in arriving at the profit for the year. Almost every type of business experiences bad debts. Customers may become bankrupt, flee the country or otherwise disappear; or there may be fraud.

Bad debts may be written off individually as they are incurred or there may be a regular percentage of sales revenue written off each year. Often a percentage charge is made, based on historical experience for the particular company and the sector in which it operates. If there is a substantial or material bad debt, the company may make reference to this in the annual report. If a major customer is declared bankrupt, this should be drawn to shareholders’ attention in the annual report, even if the company hopes eventually to recoup all or most of the debt. Such an event is important when forming a view as to the future potential of the company. It may collect the debt but how is it going to replace the revenue involved?

Prepayments and accruals

Sometimes a company will show prepayments or payments in advance as an item within current assets. Prepayments are money the company has paid in the current year for goods or services to be received in a future year. For example, a company may pay the rent or insurance on property months in advance. For most forms of analysis, prepayments are treated as being as liquid as debtors.

Current liabilities often contain an amount for accruals. These may be considered the reverse of prepayments. Accruals are expenses relating to the current year that have yet to be settled in cash. Trade payables are the suppliers’ outstanding invoices for goods and services delivered during the year. Accruals relate to other operating expenses, such as power and light, paid in arrears rather than in advance.

Cash

Cash is as liquid as it is possible to be. It consists of money in the company’s hands or bank accounts. Cash is immediately available to provide funds to pay creditors or to make investments.

Why do companies need to hold cash? Cash as an asset is worthless unless it is invested in productive assets or interest-bearing accounts. Companies hold cash for the same reasons as individuals. John Maynard Keynes, a successful investment analyst as well as a notable economist, identified three reasons for keeping cash rather than investing it in other assets:

- Transaction

- Precaution

- Speculation

The transaction and precautionary motives should, ideally, dictate the appropriate size of a company’s cash and bank balances. A company with no cash cannot continue in business. It would be unable to pay suppliers or employees. Cash is essential to fulfil the everyday routine transactions of the business. A company with insufficient cash in hand has no cushion to cover unbudgeted costs. Just as individuals try to keep some cash readily available, so companies need cash at short notice for the equivalent corporate experience.

Speculation, the third reason for holding cash, is generally less relevant to companies, since directors are on the whole not encouraged to gamble with shareholders’ money. For individuals, surplus cash used for investment with a view to the longer term, perhaps planning for retirement, can be said to be precautionary, whereas that used to buy lottery tickets, back horses or play poker is definitely for short-term speculation – money that may be lost but life can still continue.

One important aspect of the internal financial management of a company is to achieve the delicate balancing act of having precisely the right amount of cash available at any time. To have too much is wasteful; to have too little is dangerous.

How much money a company needs depends on what it does. A company that can confidently look forward to regular cash inflows, such as a food retailer, has less need to maintain substantial cash balances than a company with more discrete or uneven cash inflows, such as a construction company or a heavy goods manufacturer.

The only way to assess whether a particular company’s cash balances are adequate is to compare them with those of previous years and those of other companies in the same kind of business. The ratios described later provide useful measures by which you can make comparisons.

In assessing a company’s liquidity, it must be remembered that the timing of the balance sheet may have significant implications for the level of cash balances. A retail company producing accounts in January, following the Christmas sales period, might be expected to show little stock but a high cash balance. The company would be more liquid at the end of January than in December.

Cash and cash equivalents

Companies often invest cash that is not immediately required for running the business in short-term marketable securities or even overnight on money markets. Such investments appear as part of current assets in the balance sheet and are assumed to be readily turned into cash. For financial analysis purposes they are treated as being as liquid as cash. US GAAP and IFRS define cash equivalents as including short-term non-risk investments that are readily convertible into cash and with no more than three months’ maturity. IFRS allow bank overdrafts to be included in cash. The changes in cash equivalents can be tracked in the statement of cash flows (see Chapter 4).

Current liabilities

Current liabilities are the total amount of creditors due for payment within one year, indicating how much the company will have to pay in cash in the near future. Many of the ratios that measure and assess a company’s liquidity and solvency use the total figure for current liabilities. For most purposes this is perfectly acceptable, but it will produce somewhat cautious results. Typically, five items appear in the balance sheet under this heading:

- Accounts payable (creditors) – trade and other

- Accruals – expenses not paid at the end of the year

- Bank loans – short-term loans and other borrowings

- Tax – amounts due for payment with the coming year

- Dividends – dividends declared but not yet paid to shareholders

Loans and other borrowings that fall due for repayment in the coming year are correctly shown as part of current liabilities in the balance sheet. Other short-term bank borrowing may also appear within current liabilities. Often, as with an overdraft in the UK, this is because they are repayable on demand. It may be argued that it is overcautious to include them among “creditors falling due within one year” when calculating liquidity or solvency ratios.

Measuring liquidity

Cash and receivables are defined as the liquid or quick assets of a company. A liquid asset is already cash or capable of being turned into cash within a fairly short time. To look only at the total of current assets in the balance sheet is not a sufficient guide to the liquidity of a company.

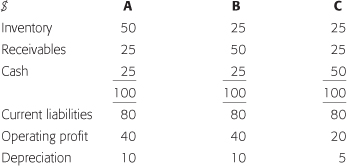

Although the three companies above have identical current assets of $100, their liquidity is quite different. Company C is the most liquid. At the year-end it has $50 in cash and can expect to receive $25 in the near future from customers. Although company B has the same amount of liquid assets as C ($75), it is not as liquid as it has less cash immediately available. Company A is the least liquid with 50% of current assets being held as inventory, which will probably take much longer to turn into cash than debtors.

Current ratio

A simple guide to the ability of a company to meet its short-term obligations is to link current assets and liabilities in what is commonly termed the current ratio. This appears to have been developed by bankers towards the end of the 19th century as one of their first and, as it proved, one of their last contributions to financial analysis. It links total current assets and total current liabilities.

Current ratio = current assets ÷ current liabilities

Current assets consist of cash balances, short-term deposits and investments, receivables, prepaid expenses and inventory. Current liabilities include payables, short-term bank borrowing and tax due within the coming year. The combination of the two in the current ratio provides a somewhat crude guide to the solvency rather than the liquidity of a company at the year end.

For the three companies in the example there would be no difference in the current ratio. As each company has $80 total current liabilities the ratio is:

$100 ÷ $80 = 1.25

For every $1 of current liabilities, each company is maintaining at the year end $1.25 of current assets. If the company paid all its short-term creditors, it would have $0.25 left for every $1 of current asset used. As a rough guide, for most companies, a current ratio of more than 1.5:1 can be taken as an indicating the ability to meet short-term creditors without recourse to special borrowing or the sale of any non-current assets.

Liquid ratio

However, its inability to distinguish the short-term financial positions of the three companies highlights the comparative uselessness of the current ratio. A stricter approach is to exclude the year-end inventory from current assets to arrive at what are called liquid assets. Liquid assets comprise cash and assets that are as near cash as makes no difference – cash and cash equivalents. This ratio is sometimes called the acid test, but it is more often termed the liquid or quick ratio.

Liquid ratio = liquid assets ÷ current liabilities

For the three companies the liquid ratio is as follows:

$ |

A |

B & C |

Liquid assets |

50 |

75 |

Current liabilities |

80 |

80 |

Liquid ratio |

0.62 |

0.94 |

The liquid ratio is easy to calculate directly from the balance sheet and there are two reasons to support its use. First, it is difficult to know precisely what physically is included in the figure for inventory disclosed in the balance sheet. Second, even good inventory often proves difficult to turn quickly into cash. Where inventory consists mainly of finished goods ready for sale, valued at the lower of cost or net realisable value, a company trying to turn such inventory quickly into cash would be unlikely to achieve this value; potential buyers can usually sense when a seller is desperate to sell and will hold out for the lowest possible price. Thus a prudent approach to assessing the ability of a company to meet its short-term liabilities assumes inventory will not provide a ready source of cash.

Company A is now identified as being potentially less liquid than companies B and C. There is still no revealed difference between B and C. Both have an identical liquid ratio of 0.94:1. For most businesses, to have $0.94 readily available in cash or near cash for every $1 of current liability would be seen as very safe. Such a company could, without selling any inventory or borrowing money, immediately cover all but 6% of its short-term liabilities. A potential supplier, having first checked that the previous year’s accounts disclosed a similar position, might justifiably feel confident in extending credit to such a company.

Whether the fact that company A has a liquid ratio of 0.62 would make suppliers unwilling to deal with it would depend on further knowledge and analysis. But clearly, through the use of the liquid ratio, company A is now isolated as being in a different short-term financial position from B and C.

Although the liquid ratio appears to be an improvement on the current ratio, it has still proved impossible to distinguish between companies B and C in the example. A further refinement is to consider current liabilities not only with current and liquid assets but also with a company’s cash flow generating capability.

The simplest definition of cash flow is profit without any deduction for depreciation. Depreciation is merely a book-keeping entry and does not involve a physical movement of cash. If depreciation is added back to the trading or operating profit shown in the income statement, the resulting figure provides a rough indication of the cash flow being generated by the company during the year. On this basis, the cash flow for A and B is $50 and for C is $25.

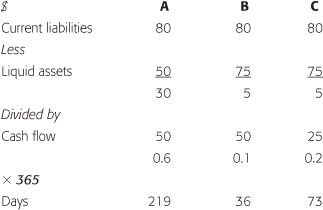

A company wishing to pay creditors will first make use of its liquid assets. If it is assumed that inventory is not capable of being turned rapidly into cash, then, before borrowing money to pay creditors, the company will rely on cash being made available from its operations. The current liquidity ratio calculates how many days, at the normal level of cash flow generation, would be required to complete the payment of creditors.

Current liquidity ratio = 365 × ((current liabilities – liquid assets) ÷ cash flow from operations)

For the three companies in the example:

If the only sources of finance other than liquid assets proved to be cash flow from operations, it would take company A 219 days, more than seven months, to complete payment of its current liabilities, whereas company B would require 36 days and company C 73 days. Assuming all three companies were operating in the same business sector, creditors assessing them would rightly feel least confident of company A.

Ratios in perspective

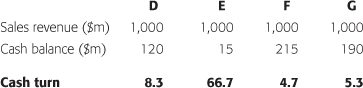

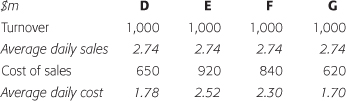

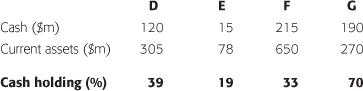

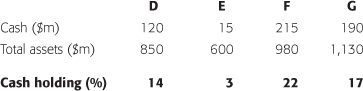

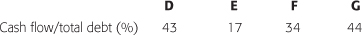

To explore further how the short-term financial position and viability of different companies can be analysed and compared, here is another example. Company D is a department store group, E is a food retailer, F is a heavy goods manufacturer and G is a restaurant chain.

From this the ratios covered so far in this chapter can be calculated.

Companies D, F and G show a current ratio of close to, or better than, 1:1. For every $1 of current liability at the year end they have $1, or more, available in current assets. The food retailer (E) and the restaurant chain (G) can be expected to operate with a lower current ratio than the department store group (D) or the heavy goods manufacturer (F). Their business is based on the sale of food, with lower investment in inventory than for the other businesses represented in the example; and they do not normally offer long credit terms to their customers.

The differences between companies’ financial positions are reinforced by the use of the liquid ratio. The manufacturer (F), with $1.24 in liquid assets for every $1 of current liability, shows the highest level of short-term solvency. As a potential creditor, possibly considering becoming a supplier, to company F, the 1.24:1 cover would provide reasonable confidence that invoices would be paid in full and on time.

However, before committing to a working relationship with F it would be necessary to compare this company with others in the same business to discover if 1.24:1 was typical. If a potential supplier to company E studied other food retailers, it would be seen that between 0.1:1 and 0.5:1 is typical. Thus on the basis of this ratio alone dealing with company E would appear reasonably safe.

As both the department store (D) and the manufacturer (F) have liquid ratios of more than 1:1, they will show a negative current liquidity ratio. They could pay all their short-term liabilities from liquid assets and still have some left over. In practice, having seen the negative values for the liquid ratio, potential creditors would not find it worth calculating the current liquidity ratio for these companies as this would not give them a better appreciation of their likely financial exposure in dealing with the companies.

The food retailer (E) discloses the highest figure for the current liquidity ratio. If the company used all its readily available liquid assets to pay current liabilities and there were no other immediately available sources of cash, it would require a further 601 days (20 months) of operating cash flow to complete payment. Before drawing any conclusions about the acceptability of this and any other ratio, it is necessary to obtain some benchmarks for comparison. If the food retailer’s 601 days is compared with the department store’s –73 days, it is clear that they have different short-term financial positions, and that, although they are both retailers, they are in completely different businesses.

The food retailer can confidently expect a more consistent and regular pattern of future daily sales than the department store. Customers make purchases more regularly in food supermarkets than in department stores. A creditor to company E can be reasonably confident that the next day some $2.7m, the average daily sales figure (see below), will pass through the cash tills in the supermarkets. The sales of the department store, although also averaging $2.7m per day, are more likely to be skewed in terms of their cash impact towards Christmas or other seasonal periods.

Creditors of the food retailer need not be concerned about the 601-day current liquidity ratio. In the UK and the US, current liquidity ratios of up to 1,200 days (four years) for food retailers are not unusual. In continental Europe, largely because of different working relationships with suppliers, ratios two or three times greater than this are to be found.

The key to interpreting this ratio, as with all others, is to obtain a sound basis for comparison. Different countries, as well as different business sectors, often have different solvency, liquidity and cash flow experiences and expectations.

Working capital to sales ratio

A good indicator of the adequacy and consistent management of working capital is to relate it to sales revenue. For this measure, working capital, ignoring cash and investments, is defined as follows:

Working capital = inventory + trade receivables – trade payables

For the four companies in the example the figures are as follows:

A negative figure for working capital denotes the fact that a company had, at the year end, more trade payables than inventory and trade receivables. This is acceptable, providing creditors have confidence in the company’s continuing ability to pay its bills when they fall due. Normally, such confidence is directly linked to its business sector and its proven record of cash flow generation. What is acceptable for the food retailer and the restaurant chain is not acceptable for the heavy goods manufacturer, because its cash inflow over the next few days is much less certain.

As a general rule, the lower the percentage disclosed for this ratio the better it is for the business. If the department store group were to increase turnover by $1m, this ratio suggests that an additional $120,000 of working capital would be required. For the heavy goods manufacturer, an additional $285,000 would be required to support the same $1m sales increase. However, for the food retailer and restaurant chain, for which the ratio is negative, an increase in sales revenue would appear to lead to a decrease in their working capital. This might well be the case for a company experiencing steady growth and maintaining creditors’ confidence.

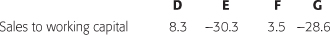

Alternatively the sales to working capital ratio could be used. This produces ratios of:

What is the trend in this ratio over a number of years? Is it showing improvement or decline? How may the movement be explained? A company may be increasing sales revenue by dealing with lower-quality customers who take longer to pay – or never pay. A company increasing inventory in order to give customers a better service may see a decline in the ratio.

Receivables to payables ratio

More detailed analysis can be completed using specific ratios focusing on particular aspects of the working capital management and structure of companies. For example, the relationship between credit given to customers and credit taken from suppliers can be assessed and compared by linking trade debtors and creditors.

Trade receivables ÷ trade payables

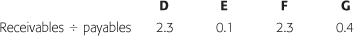

For the four companies in the example the figures are as follows:

This ratio shows that for every 100 units of credit taken from suppliers, company D, the department store, and company F, the heavy goods manufacturer, were extending 230 units of credit to their customers. Company G, the restaurant chain, gives only 40 units of credit to its customers for every 100 units of credit it receives from suppliers. Further evidence of the aggressive use of suppliers’ finance by company E, the food retailer, is provided as this ratio shows that for every 100 units of supplier credit the company extends only 10 units to its customers.

In normal circumstances, this ratio should remain reasonably constant from year to year. Large and erratic shifts either way may signal a change in credit policy or business conditions.

Average daily sales and costs

Another indicator linking a company’s short-term cash flows and financial position is its average daily sales (ADS) and average daily costs (ADC). You can divide the total sales and cost of sales by 240 to more closely represent the number of working days in the year, but, given the broad nature of the analysis, it is as effective to use 365 days as the denominator.

The cost of sales is found in the income statement in most annual reports. The figure normally includes purchases but not always staff wages and associated expenses. If there is difficulty in obtaining a truly comparable cost of sales figure for all the companies being analysed, then, by deducting the operating or trading profit from sales revenue, you will get an approximation of cost of sales.

Although comparing the ADS and ADC gives a broad idea of how much more a company receives than it spends each day, in reality companies whose trade is seasonal will spend much more than an average amount to build up stock before their peak periods for sales. They will also receive more than average from sales during peak periods.

The cash cycle

The management of working capital is critical to company survival. Continual and careful monitoring and control of inventory levels and cash payment and collection periods are essential. Working capital, particularly in connection with inventory, is also a popular focus for fraud and misrepresentation. Inventory can be overvalued or phantom inventory devised to produce an apparent improvement in profit.

The best way to monitor working capital and cash position is to use the liquid ratio, which is calculated directly from the balance sheet, and the cash cycle, which effectively combines operating activity with year-end position. The liquid ratio assumes that any inventory held has no immediate value. These two ratios should then be compared with those of previous years to test for consistency and identify any trends and, with appropriate benchmark companies, to assess conformity with the business sector.

The ability of a company to react to unexpected threats or opportunities by adjusting the timing and level of cash flows – its financial adaptability – is an important consideration. One way of assessing this from a more pessimistic viewpoint is to use the defensive interval, which indicates how long the company might survive and continue operations if all cash inflows ceased (see below).

When combined with other information from the balance sheet, ADS and ADC can help you understand the way in which the cash is flowing around the business in the cash cycle or working capital cycle ratio.

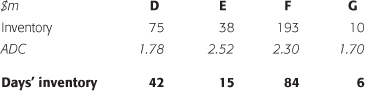

To discover how long a company’s cash is tied up in inventory, the balance sheet figure for inventory is divided by ADC to give the number of days that inventory appears to be held on average by the company. The ADC figure is used because inventory is valued at the lower of cost or net realisable value so there is no profit element involved. To use ADS would result in the number of days being understated.

The longer inventory is held, the longer financial resources are tied up in a non-profit generating item; the lower the number of days’ inventory shown, the faster is the turnover of the inventory. Each time inventory is turned the company makes a profit and generates cash.

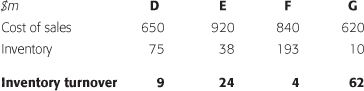

In the example, the companies hold, on average, 37 days of inventory. As you would expect, the heavy goods manufacturer (F) has the highest level and the restaurant chain (G), with fresh food, the lowest. The crucial factor is how these levels compare with those of other similar businesses.

Another way of looking at the efficiency of inventory levels is to calculate the inventory turnover for the year; this can be done by dividing the annual cost of sales by year-end inventory. The higher the resulting figure, the more effective is a company’s management of inventory. However, a company with a high inventory turnover may be maintaining inventory levels too low to meet demand satisfactorily, with the result that potential customers go elsewhere.

These figures provide an alternative view of how effectively companies are managing their inventory.

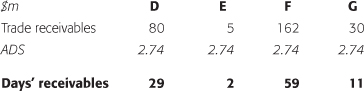

To discover the level of credit being offered to customers (trade receivables), average daily sales (ADS) is used as the denominator. The figure for trade receivables is usually found in the notes to the accounts and not on the face of the balance sheet.

In the example, the average figure for what is sometimes called the credit period is 25 days. In effect, the companies are lending their customers money for that period until cash is received, and they must provide the necessary finance to support this.

In the case of the department store group (D), it can be assumed that cash is used to purchase inventory, which is displayed for 42 days before it is bought by a customer, who does not actually pay for it for another 29 days. The time from taking the cash out of the bank to receiving it back, plus a profit margin, is 71 days. The faster the cycle, the better it is for the company.

For example, if the ADC for the department store is $1.8m and it proved possible to reduce the level of inventory by one day, the cash cycle would speed up, the profit margin would be achieved one day earlier and more profit would be made in the year. Also the assets employed in the business would decrease by $1.8m, being one day’s less inventory. If the time taken to collect cash from its customers could be reduced by one day, there would be a reduction of assets employed in the business of $2.7m and a corresponding increase in rate of return.

Cutting inventory or receivable levels reduces the assets employed in the business and increases profit, thus increasing the return on total assets (see Chapter 6). There is a direct link between the efficient management of cash flows and the overall profitability of a business.

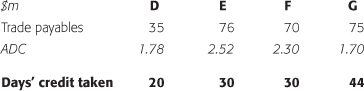

Trade creditors represent the amount of money the company owes its suppliers for goods and services delivered during the year. These are normally found, as are trade receivables, not on the face of the balance sheet but in the notes to the accounts. As trade payables are shown at cost in the balance sheet, they are divided by average daily cost.

In the example, the average length of credit the companies are taking from their suppliers (the reverse of credit given to customers) is 31 days.

Calculating the cycle

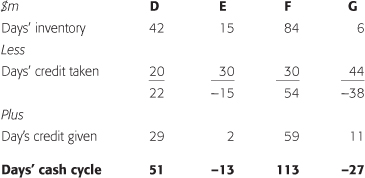

Cash flows out of the bank into inventory, from inventory into customers’ hands then back into the bank. The suppliers of the inventory are paid cash and the cash cycle is complete. The three ratios can now be combined to give the cash cycle or working capital cycle.

Cash cycle = days’ inventory – days’ trade payables + days’ trade receivables

The average cash cycle is 31 days. The two extremes are the heavy goods manufacturer (F) with a cash cycle of 113 days and the restaurant chain (G) with –27 days. It is possible now to return to the simple representation of the cash flow cycle shown earlier in this chapter and apply the average figures produced from the analysis (see Figure 8.2).

The average cash cycle experienced by the companies was for cash to be tied up in inventory for 37 days; after goods had been sold to customers it took a further 25 days for the cash to be received. The average company therefore required 62 days’ finance to cover inventory holding and credit extended to customers. As the average company took 31 days’ credit from its suppliers, it had to finance only 31 days of the cash cycle itself. Suppliers provided 31 out of the required 62 days’ finance for the average company’s investment in working capital.

The cash cycle can provide an indication of the short-term financial implications of sales growth. If the average cash cycle of 31 days is used, this suggests that for every $100 of sales $8.50 working capital is required.

31 ÷ 365 × 100 = 8.50

If the company plans to increase sales by $1m, some $85,000 additional working capital must be found to support the growth.

The use of creditors to finance this operating cycle is normal. The degree to which short-term creditors’ money is used depends partly on what is normal or acceptable within a business sector, and thus accepted by suppliers, and partly on the financial management policy of the individual company. In retail companies, particularly food retailers, it is not uncommon for trade creditors to be used to finance the business to the extent that a negative number of days is disclosed for the cash cycle.

A negative figure for the cash cycle indicates an aggressive and positive use of suppliers’ money to finance a company’s operations. A cash cycle of –10 days could be interpreted as the company taking cash out of the bank, holding it for 10 days as inventory and selling it to customers who pay within 1 day: a total of 11 days. Then the company retains the cash, including the profit margin, in the business, or invests it for interest, for a further 10 days before paying suppliers the money owed.

However, most businesses do not have negative cash cycles. Food-processing companies supplying retailers, for example, will have comparably high cash cycles.

Manufacturers can be expected to hold much more inventory than retailers. In the case of company F, there is some 84 days’ inventory including raw materials, work in progress and finished goods. Manufacturers are not cash businesses as are many retailers, and they are unable to collect cash from their customers as quickly. Company F, on average, is offering customers 59 days’ credit, twice as long as the department store group (D). This is supported by the average days’ credit being taken by the retailers. The credit taken by retailers is often the credit given by manufacturers. Lastly, manufacturers are unlikely to be able to take much more credit from their suppliers than can retailers. The heavy goods manufacturer (F) takes some 30 days’ credit from its suppliers, as does the food retailer (E).

The heavy goods manufacturer therefore experiences a cash cycle of 113 days, representing the finance the company must provide for working capital. Different types of businesses produce different standards of ratios.

It could be argued that the cash cycle should be produced by taking the average of opening and closing inventory, receivables and payables. This is found by adding the current and previous year’s figure for each item and dividing the result by two. Given the broad nature of the analysis being undertaken, it is probably just as effective to use the year-end figures set out in the most recent balance sheet.

Assessing the cash position

Current assets include the year-end cash balances of the company. At the same time, current liabilities may show some short-term bank borrowing. It may seem odd that a company can have positive cash balances on one side of the balance sheet and short-term bank borrowing on the other. Such a situation is normal, however, particularly when dealing with a group of companies. If subsidiary companies are, while under the control of the holding company, operating independent bank accounts, one may have a short-term bank loan and another may have positive cash balances. In the assessment of liquidity, short-term bank borrowing should be set against positive cash balances to provide a net cash figure.

It is not normally possible to gain detailed information concerning a company’s banking arrangements from its annual report. Moreover, the level of short-term borrowing shown at the year end as part of current liabilities may not be representative of the rest of the year.

What constitutes a good cash position?

Too little cash might indicate potential problems in paying short-term creditors. Too much cash, as an idle resource, may indicate poor financial management. Cash itself is no use unless it is being used to generate additional income for the company. Cash balances may produce interest when deposited in a bank, but a company should be able to generate more net income by investing the money in its own business.

Too much cash may make a company an attractive proposition to a predator. A company that is profitable and well regarded in the marketplace, with an appropriately high share price, may not have substantial cash balances. All available cash may be reinvested in the business to generate more profit. Such a company may regard a less profitable but cash-rich company as an attractive target for acquisition.

Various ratios can be used to gain some indication of the adequacy of a company’s cash position. It is useful to have some idea of what proportion of current assets is being held in the form of cash and short-term investments. Short-term investments may be treated as the equivalent of cash.

For the example companies, the percentage of cash to total current assets is as follows:

The more liquid a company is, the higher is the proportion of current assets in cash or near-cash items. The restaurant chain (G) held almost twice as much cash, represented as a proportion of current assets, at the year end as the department store group (D). The heavy goods manufacturer (F) and food retailer (E) maintained lower levels of liquidity.

It might also be of interest to see what proportion of a company’s total assets is held in liquid form either as cash or as short-term investments.

Under this measure, there is little difference to be observed between D, F and G. For every $1 of total assets, company F had more than 22¢ retained in highly liquid assets. Company E is the least liquid, holding just over 2% of total assets as cash or short-term investments.

The speed with which cash circulates within a company can be assessed by linking sales revenue for the year with year-end, or average, cash balances.

The higher the figure for cash turn, the faster the cash circulation and the better it is for a company; each time it completes the circuit its profit margin is added. Once again, different levels of cash turn are expected and acceptable for different types of business. The food retailer has the most rapid cash turnover (66.7 times in the year) and the heavy goods manufacturer the slowest (4.6 times).

For any company, the main source of cash should be its normal business activity. The way in which a company finances its operations depends partly on the type of business and partly on its stage of growth and maturity. The restaurant chain (G) has the highest cash flow margin (32%) and cash flow rate of return on assets or CFROA (28.3%). A high level of internally generated cash is to be expected of a mature and successful company, whereas a younger and rapidly growing company is likely to have a different balance between sources of cash inflow.

To gain a better picture of the operating performance of a company, calculate the CFROA or the cash flow rate of return on investment (CFROI) and treat this in the manner described for ROTA analysis in Chapter 6. The higher the operating cash flow to total assets ratio the better. It shows the ability of the company to reinvest in the business or that more cash is likely to be available for future upgrades and replacements. Company E again falls behind in this respect.

The cash flow margin and CFROA provide a useful supplement to the statement of cash flows in showing the ability of a company to generate cash flow from operations. They also offer an insight into how successful a company is in converting sales revenue into cash. For every $1 of sales revenue, company D produces 15¢ of cash flow and G produces 32¢. The higher this ratio the better it is for a company.

Defensive interval

Another measure of the adequacy of liquid resources is the defensive interval. If an extreme position is taken and it is assumed that a company, for whatever reason, ceases to have any cash inflows or sources of credit, its survival would be limited to the length of time that existing cash balances and short-term investments could support operations before the company was forced to rely on another source of finance to meet its obligations. This ratio, the defensive interval, is calculated by dividing cash and investments by ADC.

Cash and cash equivalents ÷ average daily cost

The more liquid a company the longer is the defensive interval.

The previous ratios showed the restaurant group (G) to be the most liquid company, so it should come first when the defensive period is calculated. If all other sources of finance were closed to company G, it would theoretically be able to maintain its basic operations for almost four months (112 days) before running out of liquid resources. The food retailer (E) would, on the basis of a similar calculation, have cash flow problems within one week.

Another way of calculating the defensive interval is to use the average daily operating cash outflow of a company. If operating profit is deducted from sales revenue and depreciation is added back, a rough indication of total operating cash outflows is produced. Alternatively, the statement of cash flows can be checked to see if it provides details of cash payments to suppliers and employees’ remuneration.

Lastly, when assessing liquidity, the figure for cash shown in a company’s balance sheet will truly reflect the cash in hand or in the bank at the end of the year. It does not necessarily provide information on what currencies are involved or where the cash is actually held.

Profit and cash flow

There need be no short-term relationship between the profit a company displays in the income statement and the amount of cash it has available at the year end. There are a number of reasons for this. For example, a charge is made each year in the income statement for depreciation that does not affect cash balances. Differences between changes in cash position and reported earnings normally result from the following:

- Operating activities. There may be timing differences between the impact of cash flowing in or out of the business and that of transactions appearing in the income statement. Non-cash expenses such as depreciation are recognised in the income statement.

- Investing activities. Capital investment – purchasing fixed assets – or corporate acquisition or disinvestments may be contained within the balance sheet but not the income statement.

- Financing activities. Raising capital or repaying loans will change the cash position but not the profit in the income statement.

It is worth looking at the relationship between operating cash flow and profit (before any exceptional items appearing in the income statement).

Cash flow from operations ÷ profit from operations

This ratio should be higher than 1, and to make sure it is consistent it should be calculated for a number of years. Cash flow should be greater than profit – there is no deduction for depreciation – to give confidence in the quality of earnings. If net income is greater than operating cash flow, creative accounting may be being used to massage income. Or there may be potential liquidity problems with insufficient cash available to cover operating costs, dividends or for future investment. A high ratio may indicate a conservative depreciation policy masking true profitability.

The working capital cycle discussed earlier can be disrupted if it is necessary for a company to use financial resources outside the current assets and current liabilities area. When a company makes capital investments, or pays dividends to shareholders, interest on borrowings or tax, the amount of cash within the working capital area is reduced.

Financial management indicators

The interest cover ratio neatly combines profitability and gearing (leverage); a low-profit company with high debt will have a low interest cover. Gearing is an important factor in survival assessment. A highly geared low-profit company is more at risk than a low-geared high-profit company. A broad measure of the way in which a company is financed is provided by the debt/equity ratio. An alternative is the debt ratio, which expresses total debt (liabilities) – long-term loans and current liabilities – as a percentage of total assets, allowing appreciation of the contributions by debt and equity (see Chapter 9).

The total debt ratio measures the proportion of total assets financed by non-equity and gives an indication of short-term future viability. The higher the proportion of assets seen to be financed from outside sources rather than by shareholders, the higher is the gearing and the greater is the risk associated with the company. A general rule is that if the ratio is over 50% and has been steadily increasing over the past few years, this is an indication of imminent financial problems. For almost any type of business, a debt ratio of over 60% shows a potentially dangerous overreliance on external financing.

In the example, the highest geared company E with a total debt/equity ratio of 320% ($320 ÷ $100) has 83% of total assets financed by debt and 17% by equity. Another way of expressing this would be to use the asset gearing ratio. When equity is funding less than 50% of the total assets, the ratio moves to above 2. Company E has an asset gearing of 6 ($600 ÷ $100) and D’s is 1.7 ($850 ÷ $500).

Cash flow indicators

Cash flows are difficult to manipulate, so the statement of cash flows offers a valuable source of information about the financial management of a company (see Chapter 4). It can be helpful to express the figures in the statement in percentage terms, especially when comparing several years or several companies. It also helps to highlight trends (see Chapter 5). Chapter 6 discussed how substituting operating cash flow for profit in some of the ratios of profitability and rates of return can assist the appreciation of a company’s performance.

Companies producing regular positive cash flow are better than those that “eat” cash flow. Operating cash flow is a crucial figure, representing the degree of success management has had in generating cash from running the business. It can be used in several illuminating measures of performance and position:

Operating cash flow ÷ interest

Operating cash flow ÷ dividend

Operating cash flow ÷ capital expenditure

Operating cash flow ÷ total debt

The first three ratios will show what proportion of a company’s cash flow is being allocated to pay for external finance, reward shareholders and reinvest in the fixed assets of the business.

For most companies, an operating cash flow interest of at least 2 or 200% is to be expected. Linking operating cash flow to dividend payments provides some assurance that sufficient cash was produced directly from the business in the year to cover the payment of dividends. All the ratios should be calculated for a number of years to assess their consistency.

Companies cannot easily manipulate or disguise their cash flows or disguise their financial structure. These can be combined in the cash flow/debt ratio. The higher the ratio the safer is the company. A minimum of 20% is often used as a guide level, indicating that it would take five years of operating cash flows to clear total debt. If the ratio were 10%, ten years’ cash flows would be required. The cash flow from the business expressed as a percentage of the total of all non-shareholder liabilities indicates the strength of cash flow against external borrowings.

The poor cash flow of E, the least profitable of the companies, produces a cash flow/total debt ratio of 17%. Another way of interpreting this ratio would be to say that it would take E 5.9 years ($500 ÷ $85) of current cash flow to repay its total debt. The period would be 2.3 years for D and G, and 3.0 years for F.

The statement of cash flows can be used to assess what a company is doing with its available cash. Is it being used to pay tax and dividends or for reinvestment in the business in non-current assets? A comparison with previous years’ figures will reveal whether the company has a consistent policy on the level of investment.

The statement can also be used to spot signs of potential problems. A company suffering from growth pangs or overtrading may show an increase in the level of receivables linked to sales revenues as more customers are offered extended credit terms. At the same time credit taken from suppliers increases to an even greater extent as the company finds it difficult to make the necessary payments on time. During this process cash balances and short-term investments decline rapidly as cash is used up. Any major changes observed in the levels of inventory, debtors, creditors and liquid balances shown in the statement of cash flows may reflect either the careful management of working capital or a lack of control by the company.

Lastly, the statement can be used to help decide whether the costs of capital and borrowings are consistent and of an appropriate level. Each year the proportion of cash flow being used to pay dividends to shareholders (cash dividend cover) and interest on borrowings (cash interest cover) should be checked.

Cash dividend cover = operating cash flow ÷ dividends

Cash interest cover = operating cash flow ÷ interest charge

Summary

- Reading the annual report and discovering that a company made a profit for the year and has several million in cash in the bank at the year end is not sufficient evidence that it is safe.

- The statement of financial position and the statement of cash flows are crucial in understanding the short-term financial position of a company. The year-end short-term assets and liabilities are set out in the statement of financial position; details of the major sources of cash inflows and the uses made of these during the year are provided in the statement of cash flows. This statement also shows, normally as its starting point, the amount of cash generated from a company’s operations during the year through the income statement.

- The liquid ratio (quick ratio) is the simplest and probably most effective measure of a company’s short-term financial position. It is assumed that inventory will not prove an immediate source of cash so it is ignored. It is easy to calculate this ratio for the current and previous year directly from the balance sheet. The result gives a simple indication of the liquidity of a company and to what extent this is consistent between the two years. The higher the ratio the greater confidence you can have in the short-term survival of the company. A 1:1 ratio indicates that for every $1 of its short-term creditors and borrowings the company is maintaining $1 in cash or assets that can realistically be turned into cash in the near future.

- As with all ratios, before interpreting the figures, it is essential to compare the subject company with others either in the same industry sector or of similar size or business mix. A low liquid ratio may be perfectly acceptable for a food retailer but not for a construction firm.

- The liquid ratio is no guide to the profitability or cash flow generation of the company. A profitable company with a healthy cash flow is less likely to suffer short-term financial problems than one with a less positive performance. Yet both companies might have an identical liquid ratio. The current liquidity ratio provides a useful means of combining a company’s liquidity with its cash flow generating capability. The lower the number of days in the current liquidity ratio the safer the company is likely to be from short-term liquidity and solvency problems. As a rough rule for most businesses, warning bells should sound if the ratio is seen to be moving to over 1,500 days (four years).

- The liquid and current liquidity ratios provide a fairly straightforward indication of a company’s short-term position. But to gain real insight into its liquidity and financial management, you should study the statement of cash flows, covering at least two years. If the cash inflow from operations (profit plus depreciation) is not consistently the major source of the company’s funds, try to find out why and then decide whether it is reasonable to assume that this state of affairs can continue.

- The ability of a company to react to unexpected threats or opportunities by adjusting the level and timing of its cash flows – its financial adaptability – is an important consideration. One way of assessing this from a more pessimistic viewpoint is to use the defensive interval. This indicates for how long the company might survive and continue operations if all cash inflows ceased.

- The cash cycle helps you see how a company is managing cash flows through investment in inventory, credit provided to customers and credit taken from suppliers. The faster the cash circulates through the business the lower is the amount of capital tied up in operating assets and, as every time the cash completes the circuit a profit is taken, the higher is the rate of return achieved.