This table has not survived, so we don't know exactly how the chords were computed. We know about it from references by other Greek mathematicians.

This table has not survived, so we don't know exactly how the chords were computed. We know about it from references by other Greek mathematicians.| 18 | Half is Better Sine and Cosine |

The story of the sine function goes back at least as far as the Greek astronomer Hipparchus of Rhodes in the 2nd century B.C. Like other Greek astronomers, he wanted to come up with a model that would describe how stars and planets move through the night sky. The sky was represented as a gigantic sphere (we still speak of the "celestial sphere"), and the positions of stars were specified by angles. Working with angles is difficult, so it turned out to be useful to relate the angle to some (straight) line segment. The segment they chose was the chord. As shown in Display 1, a central angle β in a circle of some fixed radius determines a chord, and we call it (or its length) the chord of β. Using chords, it was possible to compute current and future positions of stars and planets.

It is generally believed that Hipparchus constructed a table of such chords. He apparently worked with a circle of radius 3438 and then wrote out a table giving the lengths of the chords corresponding to various different angles. (Why 3438? Because then the circumference is very close to 21600 = 360 x 60, so that each minute of arc corresponds to approximately one unit of length on the circumference. This makes sin  This table has not survived, so we don't know exactly how the chords were computed. We know about it from references by other Greek mathematicians.

This table has not survived, so we don't know exactly how the chords were computed. We know about it from references by other Greek mathematicians.

The chord of an angle

Display 1

The greatest of the ancient Greek astronomers was surely Claudius Ptolemy. In his Almagest, written in the 2nd century A.D., we can learn the beginnings of the theory of chords. Most of the first chapter of this book is dedicated to proving basic theorems about chords and how they can be used to get information about "spherical triangles," triangles made by great circles on the surface of a sphere. In addition to working out theorems, Ptolemy explained how to construct a table of chords. Starting out with a few exact results, he then devised a method that allowed him to compute approximations to the chords of angles from ½° to 180°. These went into his table.

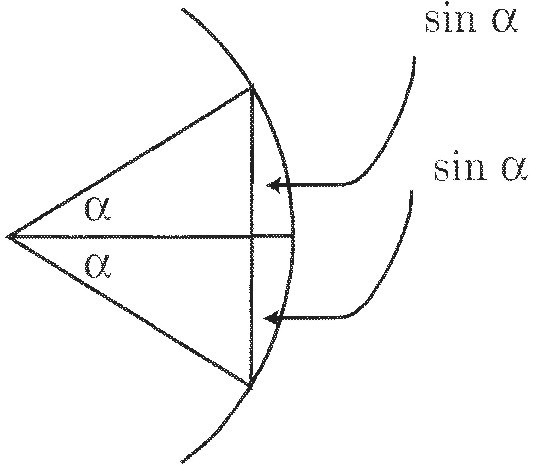

The next important step was taken in India. In a work written in the early 5th century A.D., we find a table of "half-chords." This reflected an important insight. While the chord may be the simplest way to associate a line segment to an angle, it turns out that in many situations what one needs to use is half the chord of twice the angle. This breaks the isosceles triangle associated with the chord into two right triangles, which are easier to work with. Indian astronomers understood this early on and therefore moved from tabulating chords to tabulating half the chords. The word for "chord" was jyā, which means "bow-string" (can you see the bow and the bow-string in Display 2?). Half the chord should be jyā-ardha, but since they consistently used only the half-chord they often simply used jyā or the variant form jīvā.

As you can see from Display 2, the half-chords of the Indian mathematicians are exactly the same as our sines. You can also see the other Indian trigonometric functions in the diagram. The cosine is the segment from the center to the bow-string; it was simply "the sine of the complement." The segment from the bowstring to the circle was referred to as the "arrow" (of course). We would call it the "versine", which for us is just 1 – COS(Α). The tangent was known to Indian mathematicians, but in a different context (see Sketch 28).

The sine is half the chord of twice the angle.

Display 2

There was one big difference between the Indian functions and our own, however. We think of the sine as a ratio between the segment indicated in the picture and the radius of the circle. They thought of the half-chord and the arrow as the actual line segments in a circle of a particular radius. (Ptolemy, for example, does all his computations with a circle of radius 60.) In other words, the half-chord is a segment whose length is R sin(α). Whenever any of the trigonometric segments were used, one had to take into account the radius of the circle, scaling it appropriately if the situation required a different radius. The earliest Indian tables used a circle with radius 3438. That number suggests the influence of Hipparchus, of course, but some historians argue that a radius of (360 x 60)/2π is such a natural choice that it could have been made independently.

Indian mathematicians developed very sophisticated methods for computing tables of half-chords. Since there is no way to compute exactly the length of a chord of an arbitrary angle, these methods were approximation techniques. From Āryabhaṭa in the 6th century to Bhāskara in the 12th century and onward, one finds more and more sophisticated methods for approximate computations. Many of these methods anticipate ideas that were later rediscovered by European mathematicians.

In almost every case, Indian mathematical ideas reached Europe by way of the Arabic mathematicians. That's how it was with Indian trigonometry. The Arabs learned their astronomy from India, and this included learning about tables of half-chords. Rather than translate the Sanskrit word, however, the Arabic mathematicians simply invented a word, turning the Sanskrit jīvā into jiba. For the Indian "arrow," however, they just chose the Arabic word for arrow.

The choice of the nonsense word jiba was a problem. Because Arabic is written without vowels, the word was written simply as jb. It was inevitable that readers would see it as an actual word, jaib, which mean could mean "cove," "bay," or "pocket." In his astronomy book The Canon, al-Bīrūnī says jaib was the Arabic equivalent to the Sanskrit jiva, so that version was already current by the late 10th century.

As they did in every other case, the Arabic mathematicians added their own ideas to the subject. In fact, Arabic trigonometry became quite sophisticated. They discovered the connections between trigonometry and algebra. For instance, they knew that solving cubic equations would help solve the problem of computing sines of arbitrary angles. They deepened and expanded what was known about spherical triangles, making computational astronomy easier. They also added other functions to the theory (still thought of as specific segments, however). We discuss that development in Sketch 28.

When European mathematicians discovered this material, there was, as usual, a rush to translate and study the Arabic works. When it came time to translate jaib, the translators chose the Latin word sinus, which originally meant "bosom" and had come to be applied to the hollow created by the fold of a tunic at the bosom, and from that to any hollow of that shape, including a cove or a bay. (Our word "sinuous" descends from the same Latin root: something is sinuous if it has lots of coves and hollows.) This is how we get the word "sine." For the "arrow,'' the word used at first was the Latin equivalent, sagitta. It's a pity that later "sagitta" became the much more boring "versine" — it would be more fun to talk about the "arrow."

During most of this period, the main application of trigonometric ideas was in astronomy. Astronomers mostly use spherical trigonometry, so it was this topic that filled most of the books. In the 15th century, however, trigonometry began to become an object of interest in itself. The most important trigonometrical work from that period was a book by Johannes Müller, who is usually known as Regiomontanus because he was born in the city of Königsberg. ("Königsberg" means "the king's mountain," and "Regiomontanus" is Latin for "from the king's mountain.")

Regiomontanus wrote On All Sorts of Triangles1 around 1463, but the book wasn't published until several decades later. Though it is clear that he knew about the Arabic work on the tangent function, in his book he uses only the sine. The book contains the basic theory and applications to the geometry of both plane and spherical triangles. For Regiomontanus, the sine is still not a ratio; as in the ancient Indian works, it is the length of a particular line segment. The book includes a large table of sines, computed with respect to a circle of radius 60,000. This radius was known as the "total sine," and the computations had to take it into account.

What about the cosine? Well, every so often one needed to use the sine of the complementary angle, that is, one needed sin(90°– α). (See Display 3.) At this point, however, no one seems to have given that quantity a special name. It was just the sine of the complement. Two centuries later, however, sinus complementi had become co. sinus and then cosinus.

The sine of the complement

Display 3

Regiomontanus's book was enormously influential. Over the next few decades, several other books on the subject were written. Some of them were just reworkings of the material in Regiomontanus, but a few introduced new ideas. In the mid-16th century, Georg Joachim Rheticus explained how to define the sine and other functions in terms of right triangles, without reference to an actual circle. (See Sketch 26.) Thomas Fincke invented the words tangent and secant.

Finally, Bartholomew Pitiscus invented the word trigonometry and used it in the title of his book, first published in 1595. The title page of Pitiscus's book, Trigonometry, or the Measurement of Triangles, advertises that it will include material that can be applied to surveying, geography, and astronomy. (See Display 4.) Pitiscus's book became a standard reference and textbook, and established trigonometry as an independent mathematical topic with many different applications.

Trigonometry continued to be very popular in the 17th century. This was the time of the rise of algebra (see Sketch 8), and trigonometry offered a way to use algebraic techniques to solve geometric problems. It was also sometimes used to solve algebraic problems. For example, François Viète showed that one could solve certain cubic equations using trigonometric functions, neatly reversing what the Arabic mathematicians had done centuries before.

Title page of the 3rd edition of Pitiscus's trigonometry

Display 4

All of this trigonometry still looked very different from what we learn today. For one thing, the sine was still a particular line segment drawn in a circle of a particular radius, rather than a ratio. For another, no one had yet thought of the sine as a function in the modern sense. Both of these changes happened only after the calculus was invented, and they were really cemented in place by Leonhard Euler in the 18th century. It was Euler who convinced people that they should think of the sine as a function of the arc in a unit circle (that is, that they should think of it as a function of an angle measured in radians). Euler's influence was great, and it is because of his work that we approach trigonometry as we do today.

Graph of y = sin x

Display 5

What about the sine curve, the graph of the sine, like the curve in Display 5? Well, in the 17th century, Gilles de Roberval sketched a sine curve when he was computing the area under a cycloid. It was only at this point that the sinuous form of the sine curve became clearly visible.

For a Closer Look: We first learned the etymology of the word "sine" from a chapter in V. Frederick Rickey's (still unpublished) "Historical Notes for the Calculus Classroom.'' You can see a more recent discussion in [142, Section 8.1.2]. The best book on the early history of trigonometry is [177], Maor's [120] is a readable popular account that emphasizes the more recent history. A shorter account of the history of trigonometry is [70, ch. 1].

1 The original title is in Latin: De Triangulis Omnimodis.