in lowest terms. Since a and b have no common factors, at least one of them must be odd. Now, by the Pythagorean Theorem,

in lowest terms. Since a and b have no common factors, at least one of them must be odd. Now, by the Pythagorean Theorem,| 29 | Beyond the Pale Irrational Numbers |

Legend has it that Pythagoras became fascinated with numbers by listening to music. If you pluck a taut string on a lyre or a guitar, you hear a musical note. If you pluck two strings at once, the notes may or may not sound good together. It is said that Pythagoras noticed how the harmonic quality of the notes depends on the ratio of the lengths of the strings. When it is the ratio of two small whole numbers, the strings sound good together. For example, if one string is twice the length of the other, a 2 : 1 ratio, the notes are an octave apart; if the ratio is 3 : 2, the notes form a "perfect fifth." But if the ratio is something like 1 1 : 8, the notes are dissonant. Having realized this, the Pythagoreans1 put a lot of effort into understanding ratios. And they made an amazing discovery: there are lengths whose ratios cannot be expressed by numbers at all!

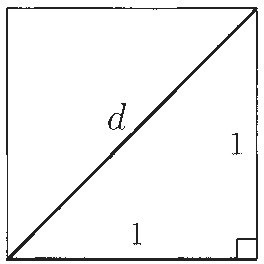

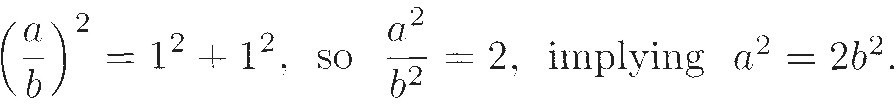

One such ratio relates the diagonal of a square to its side. No one really knows how the Pythagoreans' proof went, but Aristotle says that it involved a contradiction based on even and odd numbers. Here, in modern notation, is an ancient proof like that: Start with a 1-by-l square, and suppose that the ratio of its diagonal d to its side is a : b, where a and b are whole numbers. Then d can be written as a fraction  in lowest terms. Since a and b have no common factors, at least one of them must be odd. Now, by the Pythagorean Theorem,

in lowest terms. Since a and b have no common factors, at least one of them must be odd. Now, by the Pythagorean Theorem,

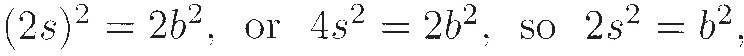

This means that a2 is even, so a must be even. (If a were odd, a2 would be odd as well.) Since a is even, we can write it as 2s, where s is some other whole number. Then, substituting 2s for a, we have

implying that b2 is even, so b must be even. So a and b are both even! That can't be, as we saw, so the only logical escape is to recognize the original hypothesis as false. That is, the ratio d : 1 cannot be expressed as the ratio of whole numbers.

Today we would say that  and call it an irrational number, but the Pythagoreans called the two segments "incommensurable" (cannot be measured together) because there is no common unit of measurement for which d is a units and 1 is b units. The ratio itself they called "irrational" or "inexpressible."

and call it an irrational number, but the Pythagoreans called the two segments "incommensurable" (cannot be measured together) because there is no common unit of measurement for which d is a units and 1 is b units. The ratio itself they called "irrational" or "inexpressible."

Similar arguments easily produce other pairs of incommensurable segments. Greek mathematicians absorbed the discovery well. They concluded that numbers and segments were two dramatically different kinds of quantities. Numbers belonged in arithmetic, segments in geometry. The link between them was the notion of ratio, but ratios of segments were far more complicated than ratios of numbers. A theory of ratios of general quantities was eventually created, probably by Eudoxus, a physician and legislator who was a pupil of Plato, in the 4th century B.C. It is the content of Book V of Euclid's Elements.

Incommensurability continued to be a productive irritant in Greek and medieval European thought for quite a long time. Indian and Arab mathematicians, on the other hand, had no qualms about dealing with "surds" (as roots of rationals were often called). They simply accepted the notion that there must be numbers whose squares were 2 or 3 or 5, etc., and set about finding ways to work with them. For instance, in 9th-century Egypt, Abū Kāmil worked with surds of all sorts, both as coefficients and as solutions to algebraic problems. In Baghdad around 1000 A.D., Abū Bakr al-Karaji wrote a book on arithmetic and algebra in which he described how the Greeks' geometric irrationals could be treated as numbers. In 11th-century Persia (now Iran) the poet/astronomer Omar Khayyám examined Eudoxus' theory of proportions from a numerical viewpoint that was well ahead of its time. And in 12th-century India, Bhāskara II2 described rules for calculating with square roots of non-square integers.

All of this knowledge was transmitted to Europe, initially through contact with Arab culture and then by examining Greek manuscripts preserved in Byzantium. Europeans thereby inherited two different points of view. One, from the Greeks, treated numbers and magnitudes as very different and connected only by the notion of ratio. The other, from the Arabs, used a broader concept of number that included whole numbers, fractions, and various kinds of roots.

Unification of these two viewpoints came by way of decimal fractions, as in Simon Stevin's book, The Tenth.3 In another book, Stevin said explicitly that rationals and irrationals alike are equally entitled to be called numbers, and his approach showed that they could all be ordered in a way that we now call the "number line." Decimal fractions greatly simplified calculation with fractions and roots, so they were quickly accepted by scientists and engineers throughout Europe. Thus, when Descartes coordinatized the plane in La Géométrie of 1637, his assertion that all the points on his axis corresponded to real numbers (as he named them) was not controversial. The fact that some were rational and some were not was irrelevant to his main ideas and to the subsequent mathematical advances of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, most notably the methods of calculus. The question of rationality versus irrationality retired to the rooms reserved for abstract mathematics, often ignored but never forgotten.

For instance, at that time it wasn't clear whether or not π is rational. It surely isn't exactly  or even

or even  but might it not be some exotic quotient of gigantic integers? The question remained open until 1761. when Swiss mathematician/physicist Johann Lambert proved that π is irrational. Almost two decades later his famous compatriot, Leonhard Euler, proved the irrationality of e, the natural base of logarithms. Investigations of these and other specific irrationals appeared in European mathematical literature during the 18th and 19th centuries.

but might it not be some exotic quotient of gigantic integers? The question remained open until 1761. when Swiss mathematician/physicist Johann Lambert proved that π is irrational. Almost two decades later his famous compatriot, Leonhard Euler, proved the irrationality of e, the natural base of logarithms. Investigations of these and other specific irrationals appeared in European mathematical literature during the 18th and 19th centuries.

How many of these irrational numbers existed was also not clear. The first irrationals discovered were n-th roots of rational numbers. All such numbers are solutions to polynomial equations with integer coefficients: they are called algebraic numbers. A simple example  which is a solution to x2 – 2 = 0. So are the roots of 2x5 – 4x + 1 =0, which are far more complicated. Are all irrational numbers algebraic? The existence of some that are not was suspected as early as late 17th century, when John Wallis conjectured that π was such a number. Such numbers had a collective name — transcendental — but their existence was unproven until the 19th century.

which is a solution to x2 – 2 = 0. So are the roots of 2x5 – 4x + 1 =0, which are far more complicated. Are all irrational numbers algebraic? The existence of some that are not was suspected as early as late 17th century, when John Wallis conjectured that π was such a number. Such numbers had a collective name — transcendental — but their existence was unproven until the 19th century.

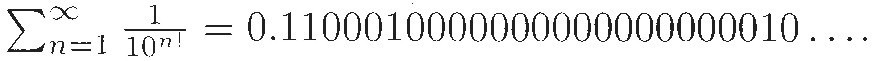

Verifying that a number is transcendental means proving that there is no polynomial equation with integer coefficients for which that number is a solution. That's hard. The first provably transcendental number, constructed in 1851 by Joseph Liouville of France, was

(the 1s appear at positions 1!, 2!, 3!, etc.) The "obvious'' candidates were stubbornly elusive. Finally, in 1873, the French mathematician Charles Hermite succeeded in proving that er is transcendental for all rational numbers r, but predicted that π would be a much more difficult challenge. That challenge was met nine years later by Ferdinand Lindemann of Germany.

Meanwhile, more and more students in engineering and science were learning the powerful methods of calculus that had been developed during the 18th century. Some of their teachers — notably Augustin Louis Cauchy in France and Richard Dedekind in Germany — became increasingly uncomfortable as they tried to explain the slippery concept of the real-number continuum to those students. They began to search in earnest for a more precise description of the real numbers.

In the last half of the 19th century, two very different, equally elegant models of the continuum appeared in Germany almost simultaneously. Building on Cauchy's work with sequences, Georg Cantor approached the question arithmetically, starting with decimal expressions of rationals. Richard Dedekind, on the other hand, took a fundamentally geometric approach. The next few paragraphs present a broad-brush outline of the main ideas of both theories. To do that, we authors must engage in an almost embarrassing amount of printed hand-waving, ignoring or finessing many significant logical issues and hoping that thereby the big pictures will emerge more clearly.

Cantor, building on the work of Karl Weierstrass, began by observing that any point on the line can be approximated from below to within any desired degree of accuracy by an increasing sequence of decimal fractions. For instance, the sequence 1, 1.3, 1.33, 1.333, . . . approaches the point labeled  which is called its limit. The shorthand for this sequence is the infinite decimal 1.333.... A similar sequence is determined by the point which is between 1 and 2. Squaring shows that it is between 1.4 and 1.5, between 1.41 and 1.42, and so on. This yields the sequence 1, 1.4, 1.41, 1.414, 1.4142,. . .; it can approach as closely as your computational perseverance permits. The visual intuition that any point can be trapped uniquely within successive powers-of-tenths intervals survives a more formal logical treatment. That is, choosing points for 0 and 1 determines a one-to-one correspondence between all the points on the line and all infinite decimals — well, almost. Some fussy special cases need attention, but they can be handled. With a bit of permissible logical tinkering, this approach leads to a representation of the real numbers as the set of infinite decimals.

which is called its limit. The shorthand for this sequence is the infinite decimal 1.333.... A similar sequence is determined by the point which is between 1 and 2. Squaring shows that it is between 1.4 and 1.5, between 1.41 and 1.42, and so on. This yields the sequence 1, 1.4, 1.41, 1.414, 1.4142,. . .; it can approach as closely as your computational perseverance permits. The visual intuition that any point can be trapped uniquely within successive powers-of-tenths intervals survives a more formal logical treatment. That is, choosing points for 0 and 1 determines a one-to-one correspondence between all the points on the line and all infinite decimals — well, almost. Some fussy special cases need attention, but they can be handled. With a bit of permissible logical tinkering, this approach leads to a representation of the real numbers as the set of infinite decimals.

This is good news and bad news. The good news: We now have a unified representation of all real numbers, rational and irrational alike, and we can tell which is which from their decimal expressions. It is not hard to show that the decimal for any rational number must eventually have a finite repeating pattern, so all the other infinite decimals represent irrationals. The bad news: Doing arithmetic with infinite decimals is pretty much impossible. Worse, treating an infinite sequence as an actually infinite "thing," not merely a potentially unending process, was unacceptable to many mathematicians of that day. The time of Cantor's set theory had not yet come (but would soon), and the idea of a number system as a set of objects with well-behaved, but abstract, arithmetic operations was just beginning to take shape.

In an 1872 paper, Cantor generalized this model to encompass limits of all rational-number sequences that "ought to" have them. Almost half a century earlier, Cauchy had described such sequences (now commonly called Cauchy sequences) by means of a convergence test that did not presuppose the existence of a limit.4 Defining two such sequences equivalent if their difference sequence converges to 0 creates equivalence classes in which all the sequences in a particular class "ought to" have the same limit. By describing ways to add and multiply them, Cantor turned that set of equivalence classes into a model of the real number system. Moreover, since each class contains an infinite-decimal sequence, the infinite decimals can still be used to represent them.

Dedekind's geometric approach focused on the points of the number line that don't have rational labels. He observed that each point separates the rationals into two disjoint sets — all rationals less than the point, and all the rest. Since there is a rational number in any interval of the number line, no matter how small, different separating points must determine different pairs of sets. If the chosen point is rational, then that number is the least element of the "upper" set. If there is no least rational in the upper set, that pair must correspond to an irrational point. Dedekind defined ways to add and multiply these pairs so that they behaved like numbers. This made the pairs of sets, now known as Dedekind cuts, a model of the real numbers.

These formal representations of the continuum did not sit well with some contemporary mathematicians. One of the most outspoken critics was Leopold Kronecker, a prominent professor at the University of Berlin, who declared that "irrational numbers do not exist."5 For measurement, he had a point. The difference between any irrational and a nearby rational number can be made as small as we please, so rational approximations are always good enough for such purposes. (Using 3.14159265 instead of π in calculating the circumference of the Earth makes a difference of about 2 inches.) But while the rationals may be sufficient for calculation, it is the irrationals that provide the conceptual richness of continuity that underlies calculus and analysis.

At the root of Kronecker's displeasure was the fact that both constructions regarded infinite sets as complete things, rather than simply as processes that could be continued at will. Dedekind's cuts were actual sets. Cantor's equivalence classes of sequences were infinite sets as well. Moreover, both treated the set of all such objects — the real numbers — as an object itself. Kronecker, who did not like any sort of actual infinity, regarded talk of an infinite collection of infinite collections as sheer lunacy.

Once Cantor had crossed that barrier and started to think about the real numbers as a whole, he found some astonishing things. Using one-to-one correspondence to define "being of the same size," he showed that there are different sizes of infinite sets. He showed that the set of all real numbers is larger than the set of rationals. In other words, there are far more irrational numbers than rational ones. This may not seem so surprising to you. After all (you might say to yourself), most roots of rationals are irrational, and there are lots of those. But here's the next surprise: Dedekind pointed out to Cantor that the set of all algebraic numbers is the same size as the set of rationals. This means that most irrational numbers are transcendental!

Kronecker's skepticism notwithstanding, the real numbers are so useful that today everyone accepts them. Many mathematicians have continued to investigate transcendental numbers. Their quest was encouraged by David Hilbert's famous 23-problem challenge for the 20th century, delivered in his address to the Second International Congress of Mathematicians in 1900. Problem 7 asked what could be said about numbers of the form αβ, where α is algebraic (and not 0 or 1) and β is an algebraic irrational. An example is  In 1934, both Aleksandr Gelfond of Russia and Theodor Schneider of Germany proved that all such numbers are transcendental.

In 1934, both Aleksandr Gelfond of Russia and Theodor Schneider of Germany proved that all such numbers are transcendental.

Despite these and other impressive results, membership in the profusion of transcendentals remains largely mysterious. Even such simple, inviting combinations as π + e, πe,, and πe are still among the "undecided." We know that most real numbers are irrational, and most irrational numbers are transcendental. But we don't know what most transcendentals look like. There's a lot more to be done.

For a Closer Look: Julian Havil's [85] gives an accessible account of irrational numbers and their history. The best description of Dedekind's "cuts" is the original one, which makes up the first half of [41]. You can read about Hilbert's problems and their solvers in [180].

1 For more about Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, see page 17.

2 See page 26 for the distinction between Bhāskara I and Bhāskara II.

3 See Sketch 4 for more about this.

4 A sequence {a} is Cauchy if, for any ε > 0, there is some natural number N such that, for all

5 Stated in a letter to Ferdinand Lindemann; see p. 204 of [85].