11

Behaviour Management

‘I’m definitely one for leaving them to cry – it’s definitely the only way to do it.’

Liz, mother of four

‘I’ve always refused to leave my baby to cry, thinking this cruel and unnecessary – especially when young, when they need comfort.’

Emily, mother of Imogen, aged 13 months

Leaving a baby to cry is an emotive phrase. Behaviour management, sensitively handled, is less about leaving your baby to cry and more about leaving him to sleep. It means giving your baby the chance to fall asleep alone, by putting him down sleepy but awake. Most behaviour management programmes involve returning to your baby at predetermined intervals to reassure him and yourself that everything is alright.

Four Simple Principles to the Behavioural Approach

• Cueing Helping your baby to learn a new behaviour by providing him with the same cues regularly. For example, you provide a regular bedtime routine for your baby, so that he knows when it’s time for sleep (see page 28 for more on routines).

• Extinction You stop rewarding your baby for the behaviour you don’t like. Babies find an amazing array of activities rewarding. Naturally, nearly all babies enjoy a cuddle, a song, a story, a drink, a smile, a carry, a video, or any other nurturing, companionable activity. But your baby might also find it rewarding when you yell or shout – he won’t find it pleasant but it is attention, and any sort of attention is rewarding.

• Reinforcement You reward or praise your baby when he does things the new way. For example, using a star chart (see page 126 on star charts), or telling him how pleased you are that he stayed in bed/slept all night/got up at 7am instead of 5am.

• Shaping Changing your behaviour and his gradually. For example, bringing bedtime ten minutes earlier each night or giving him less and less attention as he falls asleep each night.

You can use the principles of behaviour management to help your baby improve a whole range of sleep problems, and it works for all sorts of children, of all ages, although you may want to try one of the slower approaches if your baby is experiencing separation anxiety (see Chapter 6).

The programme works best when you believe that

• it is in everyone’s best interests

• this is the best way to do it

• you and your baby can manage it, and

• you feel supported in your choices.

It doesn’t work for everyone.

‘We tried letting Rhian cry and it didn’t work at all. There was no improvement. She would cry for one-and-a-half hours every night and fall asleep with exhaustion. We thought it wasn’t fair. She started to whimper when she saw her cot during the day. So it doesn’t always work.’

Dilys and Mick

But it does work for many others.

‘The book says it works within a week, but for myself and two friends our children were sleeping through the night sooner. The first night of the programme was the worst. This harsher treatment has not caused our second child to be less confident as some books and people suggest. She is very calm, whereas my first makes mountains out of mole-hills.’

Brenda and Dave, parents of Mark and Esme

How to do it

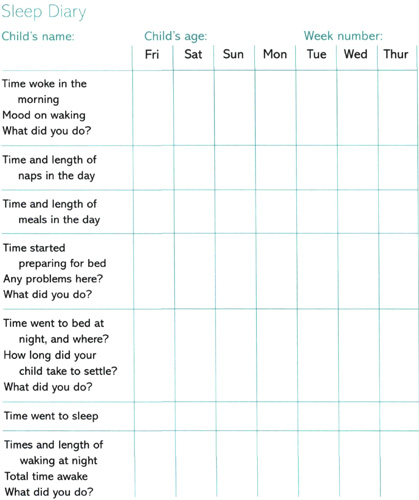

Keep a sleep diary for a week before you make any changes so that you can see where the problems and the patterns occur. Choose a week when no one is ill and nothing out of the ordinary is planned. Keep the diary and a pen next to your bed, so you can jot things down as they happen. Make a note of what the whole family did, where and when. Sometimes siblings can make a difference to your baby’s sleep pattern. Copy the chart opposite or make your own.

‘When we were having problems getting Kate to sleep through, my husband suggested I keep a sleep diary. You get in a blur – it just seems to get things in perspective.’

Tessa and Alan, parents of Jack, three, and Kate, two

Use your sleep diary to identify the problem areas: needing you to be there when he falls asleep in the evening or at night; elongated bedtimes; night waking; night feeds; late bedtimes and early mornings. This chapter deals with night waking and settling in the evening; the following chapter deals with moving the time at which your child sleeps. If you’re still feeding at night, have a look at Chapter 5 as well.

When you’re ready to start your new routine pick a time to do it. Some parents find that it’s better to do it in the day first, when they have more energy. Others find that it works better to concentrate on the evening and night first and let the day fall into place. The weekend is often a good time to start so that you can catch up on the sleep you lose more easily. Keep a sleep diary while you are using the new routine. It will show you where you are making progress and where you may need to make more changes. If you are following one of the programmes with the support of a health professional or friend, your sleep diary will probably help them to see what is going on as well.

Devise and stick to a simple and relaxed pre-bedtime routine (see Chapter 3 for ideas about routines). Once you’ve tucked your child into bed and kissed him goodnight, you have four options.

Option 1: Cold Turkey

If you want to achieve some results quickly, leave your child to sleep and do not go back at all. You may have to bear a lot of crying, but it is likely that after the first few days your child will go to sleep easily on his own. However, this approach often fails because it is too traumatic for parents and babies alike. Leaving your child to sleep like this can be quite shocking for both of you, especially when your previous goodbyes have been long.

‘Leaving Thomas to cry from six weeks did work over a couple of months and not feeding him until 4am or later gradually encouraged him not to bother waking.’

Jane

Option 2: Controlled Crying

Alternatively, leave your baby to sleep but return every so often to reassure yourself and him.

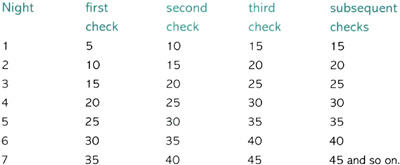

After the bedtime routine on the first night, stay out of sight for five minutes; if he is still crying after this time, return and reassure him that you are still there. If he is standing up, lay him down; if he is still lying down, gently stroke him. Then leave. This time wait for ten minutes; if he is still crying and shows no signs of quietening, go in again and repeat what you said before. The next time leave it for 15 minutes. On the first night, leave a maximum of 15 minutes between all subsequent visits. The whole procedure may take anything between two or three hours the first night. Older children usually take longer and tiny babies less time.

On the second night, wait for ten minutes before you go to reassure him for the first time, and then 15 and then a maximum of 20 for all successive visits. This time the total time until he sleeps should be shorter. On subsequent nights increase the waiting times by five minutes.

Leave your baby to go to sleep for this many minutes before you return to reassure him briefly. There’s nothing magical about these timings. Decide what you and your baby can manage and stick to it.

Some parents like to look their child straight in the eye and say something like ‘Go to sleep now’; others prefer to deliberately avoid their child’s gaze and just pat their child’s back or lay him down again, or you could try the approach on page 21. It’s up to you. The important thing is to do the same thing on each occasion, and make it simple and minimal. Do not give him anything that he cannot get on his own. You want him to be able to go to sleep without needing you. So don’t offer a bottle or a cuddle or a song. It is important to sound and behave confidently. Your confidence is your child’s security.

Karen and Phil tried the checking approach with David for three and a half months of disturbed nights before they realized that they had been doing it wrong:

‘We used to go in to David three or four times a night, using the controlled crying technique each time. But it just didn’t seem to work – he kept on waking up. We were just so tired. I’d got to the point where I really hated him. I thought, “I’ve made a big mistake having children at all.”

It was only after we’d been battling with it for three and a half months that I read somewhere that we shouldn’t be giving him a bottle whenever he woke, because he would wake up just to get it. I’d been giving him one because I just hadn’t realized that there comes a time when babies don’t need something at night. So we stopped the bottle, it was only water, and within two nights he slept through. Only for six hours, but it was wonderful. It really works, you just have to do it properly.’

If he calms down significantly while you are out of the room, do not go back in to him. A visit from you at this point may make him start all over again. Check on him once he is finally asleep, if you want to, but leave it at least half an hour so that you can be sure he is deeply asleep.

Be prepared for a test time on the third, fourth or fifth night. Your baby has understood that this is the new routine and is making one last-ditch attempt to get things back to where they were and his cries may be longer and more bitter than before. Once this long night is over you should be almost there, although for some people the process is longer.

‘I did the five-minute routine suggested by the counsellor. She said it would solve the problem in six weeks. It actually took three months to do. We got it down to one night waking – I could live with that. It is painful. They can cry for a long time if you keep going back. I wrote down everything that happened – how I felt, what I did. It allowed me to see how things had changed. I did some sewing or the ironing so that I didn’t feel so resentful when she kept going for two hours.’

Kim, mother of Rowan and Lloyd

Option 3: the Kissing Game

Try this procedure if your child appears anxious at bedtime or needy in the day or if you don’t feel right leaving him alone to sleep. It is particularly suitable for children between six months and two years, but it can be used for pre-schoolers too.

After a relaxed bedtime routine, kiss your baby goodnight, and promise to return in a minute to give another kiss. In fact, you should return almost immediately to give another kiss, take a few steps away and then another kiss, put away something in the room and then kiss again, pop outside for a few seconds and then another kiss, and so on. So long as your child is lying down with his head on the pillow, or on the cot mattress, he gets more kisses, but no more chat, cuddles, stories, plays or drinks. Just kisses until he is asleep. Think of yourself as being on a piece of elastic – bobbing back and forth to your child.

If your child jumps out of bed, keep it light. Say something like ‘Come on now, you know the deal, into bed and I’ll give you a kiss.’ Then help him back to bed. Some children cry from crossness and some giggle, but none are frightened by this approach.

When your child is almost asleep it’s difficult to judge whether to go in again for another kiss. Again it’s up to you, but remember that you have made a contract with your child – you’ll kiss him in a minute if his head is on the mattress. Maybe it’s worth the risk of rousing him just one more time so that he’s completely secure about the programme.

The programme requires a lot of energy and time initially, but it can be enjoyable for parents and baby alike, in spite of the sore lips! Be prepared to give up to 300 kisses on the first night over a three-hour period and remember to put your dressing gown on when you get up at night, because you could be busy for some time and feeling cold is a powerful disincentive to seeing it through. Gradually, it will take less time and fewer kisses for your baby to sleep.

As with the controlled crying approach, some children test their parents’ resolve – often on night five. If you can weather that storm, the next couple of nights should be the last on the programme. Most children are sleeping easily within a week.

If kisses seem to take too long or your back can’t manage all that bending, then a pat on the hand or the head works just as well. Just make the same sort of contact each time.

Sometimes parents live in ways that make this sort of intensive procedure difficult to do. If you are a single parent, start the programme on a Friday, and ask a friend or your mother to have the baby for Saturday and Sunday afternoon so you can sleep. By then your baby should be falling asleep more quickly.

Kate used the kissing game with Jade when, at 18 months, she seemed frightened to go in her cot.

‘Jade suddenly stopped wanting to go to bed, it was as if she was scared that if she touched the mattress she would disappear. I didn’t know how to go from pacing up and down to putting her down. At the 18-month check-up I told the health visitor all about it and she told me about the kiss-and-retreat programme. The first night they think it’s a game so they play along with it until they doze off. The second night they fight it. When she has a tantrum it’s really upsetting to watch because she head-butts the wall. She was scooting down to the end of the bed and I was trying to put her back up to the pillow. It was 45 minutes to one hour of constant head-butting and screaming, she was so tired at the end of it she just conked out. On the third night she tried everything she could. But it worked because after a week I stood by the door, and after that outside the door. Then I shut the door and she called to me and I said: “Go to sleep, I’m here.” And after that I thought I might as well go downstairs, so I did and she was fine.’

Angela and Neil used the same approach with Alex when he was eight months old:

‘The problem was that I’d lay there for ages rocking him. He’d sleep for 20 minutes and be awake again. I was up four or five times a night. He basically catnapped. I ended up sleeping with him in the double bed. The health visitor gave me a plan: put him in his cot, give him a kiss, shut the curtains, say “Night-night”, and walk away. When he starts creating go back and comfort him. Don’t make eye contact. Drop the side of the cot, put my body-weight on him. Say “Everything’s OK, mummy’s here”. The first night was horrendous. It took me an hour each time he woke, straightening the bedding, no eye contact. I sat on the end of the bed with my back to him and then gently worked that bit further out of the room. But it only took about two nights. He went from going to bed at 11 pm, and then up at 12, 2am, 4am, and 6am with two catnaps in the morning and three in the afternoon to 40 minutes in the morning, two to two-and-a-half hours in the afternoon, tea, a play, and then upstairs for a long bath, a regular routine in his room for a bottle, and a book. He’s usually in bed by about 8pm and sleeps through until 7am or 8am. He’s definitely happier during the day and he doesn’t look like Count Dracula any more with his red eyes and white face.’

If you’d like to try this approach with the support of your health visitor, it’s worth showing her a copy of an article by Dr Olwen Wilson who devised the programme. (See the further reading section on page 155 for a complete reference which you can order through your local library.)

Option 4: Gradual Withdrawal

This is the option for you if you don’t want your child to cry at all. It’s based on the idea that a series of small changes is easier to get used to than one large one. The idea is to distance yourself gradually from your child as he goes to sleep, only moving further away when your child has got used to the previous position.

Take it in tiny stages. If you’re lying down with your baby to get him to sleep, sit on the edge of the bed instead, and then when he’s happy with that, move to a chair by the bed. Then move the chair little by little across the room. Finally sit outside his door for a few evenings, just so that he can call to you if he needs to. After that you should be able to get on with your evening. Each position may take two or three nights. Don’t rush it. Go at the pace your baby can manage. You will need to offer your baby a lot of reassurance that he can manage each new position. If you stay firm it will work.

Some parents find that they begin gradually and are able to speed up the process later. Marion used this technique to get Richard to sleep alone:

‘When Richard was four I was still lying with him to get him to sleep. I was happy with the arrangement but Richard’s sister. Barbara, who was eight, wasn’t. She felt it was unfair, because I didn’t lie with her. I suppose I might have gone on lying with him but for two or three chance events. Firstly, one night James put Richard to bed and came down after the usual half an hour saying that he had lain on the sofa in the children’s room, instead of on Richard’s bed because he had a book he wanted to read and Richard hadn’t been upset, but had fallen asleep in the same way as usual. So I tried the same approach and it worked.

Then James was offered a job at the other end of the country and had to furnish a flat within a few days, so he needed the sofa from the children’s room. Having nothing now to lie on and being a single parent during the week I had to readjust the sleeping arrangements. I told Richard that I needed to spend half an hour with Barbara after he went to bed and that I would just be downstairs if he needed me. It worked amazingly well. I came down after the statutory two songs and a chat, Richard went to sleep and Barbara got some quality time alone with me which she had never had before.’

Use the gradual withdrawal approach to move your baby from your bed to his own. But this time it’s him rather than you who moves a little further away every two or three nights. On the first night try putting him in his cot with the side down, or on a mattress on the floor next to your bed; after that raise the side on his cot and leave him sleeping next to your bed a little longer. Then gradually begin to move the cot or mattress further across the room and finally into his own room. You can have as many stages on the route to his bedroom as you like.

Variations on a Theme

All these approaches have good points and bad points. Generally, the quickest results mean the most tears. Whichever you choose, stick with it for at least three nights, be prepared for a test night, and be consistent. Some parents have adapted the behavioural approach to fit in with the sort of relationship they have with their children, and feel it works. One mother kept her baby in her bed but patted her back instead of feeding her:

‘When Hannah was 27 months I decided to stop breastfeeding her as it was starting to annoy me. I couldn’t sit down without her being attached to me. We couldn’t even look at books together. Firstly, I stopped feeding her in the day. That was the easiest. I just didn’t sit down and we went out a lot! After a couple of weeks it was going quite well so I decided to stop her feeding in the night too. When she woke up I lay in her bed next to her (firmly on my front!) and patted her on the back until she went to sleep. After a few days she didn’t ask for a feed at bedtime so I decided that was the time to stop altogether.’

Dawn, mother of Rebecca, six, Hannah, four, and Lucy 18 months

Another mother, Kim, knew what would work for her third baby, Eden:

‘We’ve started a sleep routine now that Pete’s got a clear stretch at work. The old routine was that I breastfed Eden until she eventually fell asleep on me. Then she might get up and play for a bit, and then I’d feed her again, she played again – she kept going until she was really tired. Yesterday we went upstairs and looked at her brother and sister in bed and asleep. Then we went into her room and read a story, and she lay down and went to sleep with me stroking her hand. She slept for six hours.

At 2am I went in and stroked her hand for six minutes until she calmed down and went out for a couple of minutes. When I went back in she was standing up and I talked to her about the teddies. I had a resigned calm about me – I didn’t force her, I knew I was going to do it. In my heart of hearts I didn’t want to be separated from her, but I’ve had to decide for all our health that I need to do it. I carried on leaving her for two minutes and going in for six. It took 40 minutes. In the end I left her for five minutes and she went off. She woke up at 6am and I brought her into my bed. I felt it was long enough to have gone without a feed.’

Just occasionally a baby cries so hard he vomits:

‘We were assured that the controlled crying technique would only take two weeks. But it was terrible. It was barbaric. Both her and our suffering was indescribable. She would scream for hours, bang her head against the cot, pull out her hair, stick her fingers down her throat and make herself sick and, worst of all, cut the inside of her mouth with her nails so that when we went in there would be blood dripping from her mouth.’

Fiona, mother of Phoebe

Even more rare and more worrying still is the baby who passes out when he cries. In both cases it’s a good idea to visit your GP once again to rule out physical causes for these reactions (or see Chapter 10 on alternative help). If you still want to try a behavioural approach, try a more gradual one, so that your baby doesn’t become so upset.

Making it Work

Charts: One for Both of You

Many parents find it helpful to carry on charting their progress, while using a behavioural programme. The sleep diary is a good way to do this. It can be reassuring for you if you’re finding the programme difficult, and it can help you to see where the weak points are in your strategy when you feel like giving in. It can also be useful to discuss your chart with the professional or friend who is supporting you.

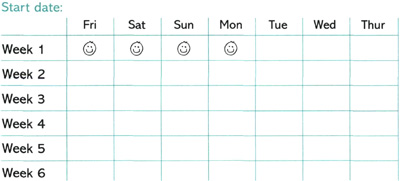

Your toddler may find star charts exciting. Copy the one below or make your own.

Star chart

Goal: e.g. Jo goes to sleep alone ![]() e.g. Sam stays in his bed

e.g. Sam stays in his bed ![]()

Either buy some stickers or draw on a star for each night your child achieves the goal you set. Some children like to put up their own sticker, or choose which colour pen you use to draw the star.

Do it as soon as your toddler wakes and make a point of praising him at the same time. If you have had a bad night just ignore the star chart. Don’t underline his failure by drawing attention to it and don’t give a sticker just to make him feel better – giving a ‘free’ one diminishes his effort in gaining the others.

You may find that the sticker alone is motivation enough for your child. But some children lose interest after three or four stickers so it may be worth building in a small present or a treat once you are sure that the star chart is beginning to work. However, don’t mention the treat before you see which way the wind blows because failing to get a star is one thing, but failing to get a present is another. When you are convinced that your child will make progress with this scheme, offer him a present if he keeps up the good work for just three or four more days. In this way the star chart acts as a motivator and a reward.

Try not to use the star chart to threaten your child at night. If he is finding the programme hard work, it won’t make it any easier for him to do it if you say: ‘Right then, you’ve got up again, there’s no star for you in the morning.’ This will only leave him with a double anxiety – that he must go to sleep alone and yet not get a star. Whatever you do in the morning, you then lose. If you give him a star he may think he can get up each night; if you don’t give him one he will believe that he went to sleep on his own for nothing.

It’s better to avoid talking about the star chart altogether unless you can do it in a positive way. For example: ‘Which sticker are you going to choose tomorrow – a rainbow or a Mickey Mouse?’ Or ‘Can you remember what you get in the morning when you go to sleep nicely?’ Or ‘You only have to get one more sticker and then we can go swimming/buy that toy/have your friend to play.’

Climbing Out of Bed

It’s easier to help your cot-bound baby to learn to go to sleep alone because he has to stay where he is. When faced with a new bedtime routine many toddlers protest by getting out of bed and coming to find you.

There are three behavioural ways you can help your child learn to stay in his bed.

Game-Plan 1: Back to Bed

If your child gets out of bed, lead him back straight away and without comment. If you are trying a gradual withdrawal approach or the kissing game, then carry on with the same approach as though nothing had happened. If you are trying a cold turkey or controlled crying approach, leave his bedroom once you’ve put him to bed again and sit outside his door. In this way the back-to-bed routine will be quicker and less frustrating than if you tried to watch television or eat dinner. If you are following the cold turkey plan, continue to sit outside his door until he falls asleep; with the controlled crying plan, return to him only when it is the set time to do so (use the timing charts from page 116). Try to put him back to bed without shouting or forcing him, no matter how tired or frustrated you are. Your child may find these emotional reactions rewarding, and stay awake just to hear you shout some more.

‘I recently resolved the bedtime nonsense with Alice (nearly three years old). I told her she was going to learn to go to sleep. I put her in her bed, then sat outside her room. Each time she got up I put her back without a fuss or a row, tucked her in and told her “Goodnight”. The first night it was three hours before she stopped coming out – as she got tired, the visits became more frequent! Within ten days she had stopped coming out and only rarely does so now. It was fairly painless. Things improved when we resolved to improve them and gave ourselves a time limit (two weeks), and stuck to it. This is very hard to do when you are exhausted and worn down.’

Gillian

Max, who has a rare antibody deficiency which causes him severe pain, used to wake between eight and 15 times a night. But Catherine and Trevor tried the same approach as Gillian:

‘The sleep therapist told us that part of Max’s sleep problem had been caused by the pain Max experienced and part was the result of the perfectly understandable things we’d done to help him cope with the pain. She was marvellous, she advised us to wait until Max had a spell of being fit and then tackle the part of the sleeping problems that were to do with us. We put him to bed and then sat outside his door. Every time he came out we put him back to bed. We had to keep a record of how many times it happened. Max broke all the records. The first night he got up 217 times in two hours! (Our sleep therapist was amazed – before that the worst case had only been 84 times.) The next night it was much better – only a hundred and something. Within the week he was staying in bed.’

Game-Plan 2: Back to Bed and Close the Door (for use with the cold turkey or controlled crying approaches)

Do the same as in game-plan I above, but this time tell your child that you are going to close the door and keep it closed for one minute. Tell him that if he is still in bed when you open the door you will leave it open and come and see him when the time is up, if he is out of his bed then you will shut the door for two minutes. Every time your child is still out of bed when you open the door close it again for a minute longer than you did last time. It may be hard for your child to understand all this at once. So you could just say, ‘Get into bed, I’ll open the door in a minute’.

The only trouble with this approach is the undignified battles you may have with the door handle: you and your toddler on opposite sides of the door pushing and pulling. If you find yourself in this position, give thanks that you have such a tenacious child, but that you are still physically stronger than he is.

Game-Plan 3: Door Fixed Ajar (for use with the cold turkey or controlled crying approaches)

This solution is recommended by Dr Christopher Green in his book Toddler Taming (1995). He calls it the rope trick. Many children are frightened when their bedroom door is shut at night, but nevertheless make a habit of coming out. You could try tying the door with some string so that it is just ajar. The gap you leave should be small enough to stop them squeezing out but wide enough to allow sufficient light to enter the room. It is imperative that if you choose this method of controlling your child’s wanderings, you make the gap too small for him to force his head through and get it stuck. Make the gap too large and this technique can be dangerous.

Alternatively, a stair gate fixed across the bedroom door can work well unless your child can climb over it. Move away any objects from the doorway that could be climbed.

Ten Point Plan for Success

• Keep a sleep diary for a week before you start.

• Agree your goal. Sleep all night long? Go to sleep on his own? Stay in his own bed all night?

• Agree your method: cold turkey/controlled crying/kisses/gradual withdrawal/other.

• Agree exactly how you will do it: what will you say?/How will you say it?

• Agree who will do it: taking turns every night/one night off – one night on. If you are a lone parent, ask a friend or your mother to help.

• Tell the neighbours what you are doing.

• Explain the programme to your child if appropriate.

• Pick the right time: start the programme when you can afford to be more tired than usual, or can go to bed earlier than usual, when there are no other changes in your baby’s life, and no one is ill.

• Keep a record and talk about it to each other or to someone else you trust.

• Try for at least three nights.

And … enjoy your sleep, and a happy child in the morning, eventually!