Psychological Perspectives on Public Opinion

Given how often opinion is construed as a matter of mind, it is no wonder that psychology—the study of mind—offers crucial insights into public opinion. Why do some people believe in global warming, while others do not? Why are some people convinced that the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) is the answer to providing health care for millions of uninsured Americans, whereas others believe it represents the erosion of basic American values? Psychological concepts and research help us understand how people’s mental makeup affects how we process events and new information: how our minds change, and why they often do not. Although much public opinion research relies on methods taken from psychology, researchers sometimes neglect psychological, sociological, and communication theories when they interpret their findings, perhaps because there are so many disparate theories. But even though these scholars do not agree on a master theory of mind, a grounding in psychology is relevant to many aspects of public opinion. In this chapter we focus on psychological processes at the individual level. In Chapter 7 we explore how social and psychological factors interact in the formation and expression of public opinion.

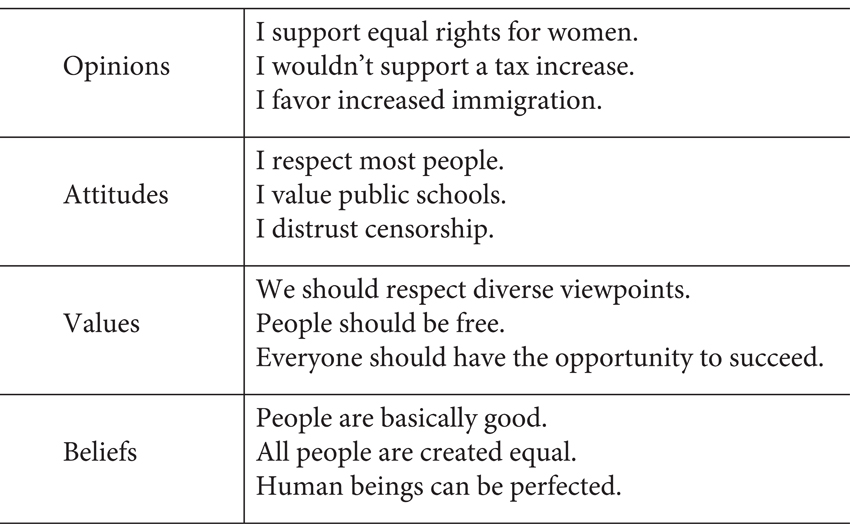

SPEAKING THE LANGUAGE: BELIEFS, VALUES, ATTITUDES, AND OPINIONS

Psychological research typically employs one or more of four basic concepts: beliefs, values, attitudes, and opinions. Scholars often have debated the definitions and even the merits of these concepts, but most contemporary discussions rely on definitions similar to the ones we present here. Statements about what and how people think are often bewilderingly vague; distinguishing among these concepts can help to bring clarity.

Beliefs

Beliefs are the cognitive components that make up our understanding of the way things are, that is, the information (true or false) that individuals have about objects and actions.1 They are the building blocks of attitudes and opinions. Beliefs are often difficult to identify, especially when they are widely shared. Such beliefs are the assumptions by which we live our lives, and we generally presume that others think of the world the same way that we do. For example, most Americans hold the belief that people can change for the better or the worse, through their choices or because of circumstances beyond their control. (Some people place more emphasis on choice, others on circumstance.) In contrast, the caste system is based on the belief that people do not—and in fact cannot—rise above, or sink below, their origins.

Some beliefs stand on their own, but many are grouped together as belief systems. These systems may be quite simple, consisting of only a few items, or they may be enormously complex, involving hundreds of related beliefs. For example, belief in castes is often part of a Hindu religious belief system that integrates beliefs about reincarnation and karma.

Belief systems, to the extent that they are “systems” at all, tend to be thematically and psychologically consistent.2 However, we often see conflicts between these belief systems. For example, in contemporary US politics, Republicans tend to hold various beliefs associated with distrust of big government—a basic premise of the Republican Party is that government regulations usually hurt the economy, that tax cuts usually help the economy, and so on—whereas Democrats tend to hold contradictory beliefs. Democrats often believe government regulations are necessary to curb the power that corporations have in a capitalist system. These clashing belief systems can often complicate or preclude compromise. Even within individuals, beliefs or belief systems can conflict, as we discuss below.

Values

Values are ideals. While beliefs represent our understanding of the way things are, values represent our understanding of the way things should be. Many researchers, following Milton Rokeach,3 distinguish between terminal and instrumental values.4 Terminal values are the ultimate social and individual goals we want to reach, like freedom or financial prosperity. Instrumental values are the constraints on the means we endorse to pursue our goals, such as honesty, responsibility, and loyalty.

Leaders of social movements often invoke values, sometimes incorporating them into a motto that describes the movement to others. Leaders of social movements often attempt to connect their activities to a desired goal. Mottoes like Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” helped to frame the American Revolution in terms of the value of freedom. Individual liberties and personal accomplishment have been important characteristics of American culture. The French Revolution was built on a slightly different set of values: “Liberty, equality, fraternity.” Note that supporters of both revolutions tended to share not only values but some beliefs—including, crucially, the belief that a revolution could bring about progress toward realizing their values.

Because values, like beliefs, tend to be taken for granted or treated as universal, people often are taken aback by value differences. One of the authors once taught at a university in another country in which collective and societal attainment is valued far more highly than individual accomplishment as generally construed in the United States. The professor confronted a student for cheating on an exam by getting answers from the person in front of her. The student said very little, except that she was “ashamed.” The professor did not realize that this situation reflected a difference in values until she discussed the incident with another student. “Yes,” the other student agreed. “I’d be ashamed as well. … Getting caught that easily is a very silly thing to do.” The student explained, “It is not wrong to cheat, but it is very embarrassing not to cheat correctly.” Many American students agree that it is not wrong to cheat,5 but perhaps not many would have said so to a professor.

Attitudes

Attitudes have been defined as relatively stable and consistent positive or negative views about a person, place, or thing.6 More often, attitudes are defined as evaluations—good or bad, likable or unlikable—that have both emotional (affective) and cognitive elements.7 Naturally, attitudes can be mixed: you may find a person likable in some ways and unlikable in others.

The distinction between beliefs and attitudes is not always sharp. After all, some beliefs are evaluative. You may believe that Apple makes good smartphones—and if you do, you probably also have a positive attitude toward iPhones. Still, the belief is distinct from the attitude. To believe that iPhones are “good” is to think that they have some particular merits—perhaps that they are highly reliable, easy to use, or attractive. If you believe those evaluations (or some of them), then you construe them as inherent characteristics of iPhones, or at least as judgments that many other people would share. You might have a positive attitude toward iPhones—or anything else—without having particular beliefs about why they are good.

Although attitudes are distinct from beliefs, they are related to beliefs and values. For example, if you believe that marijuana is harmful, or if you hold the value that people should avoid mind-altering substances, then you are likely to have a more negative attitude toward marijuana. Some theories show that our attitudes are largely built on our beliefs and values, while others posit that our attitudes influence our beliefs and values, as we will see.8

Researchers disagree about the relationship between attitudes and behavior. For some researchers, behavior is actually a component of attitude structure,9 and perhaps a particularly useful one: how people react to spiders may reveal quite a bit about their actual attitudes toward spiders. Using a more complex example, perhaps I have a friend whom I like very much. However, I may strenuously disapprove of people who live on welfare. If my friend goes on public assistance, I may decide that I no longer like him. or that people on public assistance are not so bad. Or I may just live with these conflicting feelings, retaining my beliefs while still liking my friend.

Regardless of whether or not there is overlap between attitudes and behaviors, public opinion researchers generally distinguish between the two. As scholar Bernard C. Hennessy puts it, attitudes create “predispositions to respond and/or react [and are] directive of behavior.”10 How directive? It depends. Changing people’s attitudes does not always change their behavior. And in some circumstances, people’s attitudes may not predict their behavior at all.

Opinions

Some researchers use “opinion” and “attitude” more or less interchangeably, but many make a distinction, as we do here. In Thurstone and Chave’s classic definition from 1929, an opinion is “a verbal expression of attitude.” They write that a man’s attitude about pacifism means “all that he feels and thinks about peace and war,” whereas if the man says that the United States was mistaken in entering World War I against Germany, that statement is an opinion.11 Under some definitions, the man might hold that opinion even if he never expresses it—but to hold an opinion generally implies that someone would express it if asked. Thus, opinions tend to be narrower and more consciously held than attitudes, more like someone’s answer to a simple question, rather than a mélange of thoughts and feelings. Indeed, for many researchers in the tradition of Thurstone and Chave, opinions primarily are the answers that people give to questions designed to investigate their underlying attitudes.

FIGURE 5.1 Beliefs, Values, Attitudes, and Opinions: A Cognitive Hierarchy. This figure depicts a model in which beliefs form the basis for values, values for attitudes, and attitudes for opinions.

Opinions may be less stable than attitudes or beliefs. Suppose that I am asked my opinion of the president’s job performance. If I am like most people, I do not have a fixed belief about how well the president is doing; I have attitudes about various things the president has done. I might opine that I strongly approve, or that I somewhat disapprove, of his performance, depending on what attitude(s) come to mind when I am asked. Even the opinions I volunteer can be inconsistent: I might say that the president is doing a great job, or a terrible one, depending on the course of the conversation.

Figure 5.1 summarizes what we have been discussing in this section. Notice how attitudes are built on beliefs and values and are finally expressed as opinions. Notice, too, that the same beliefs and values may produce divergent opinions that may even seem contradictory.

EARLY THEORIES OF ATTITUDE FORMATION AND CHANGE: THE LEGACIES OF BEHAVIORISM

You may already have noticed a problem: psychologists cannot examine attitudes (much less beliefs and values) directly. Generally, researchers infer attitudes from people’s answers to questions—their stated opinions—or from people’s behavior in experimental settings. Even if people’s opinions and actions provide accurate measures of their attitudes, often we cannot know whether those attitudes existed before they were measured, or if the research study brought them into being. Partly for this reason, researchers often use the term “attitude change” to include attitude formation. Presumably people form and change attitudes through similar processes.

Paradoxically, an enduring model of attitude change—behaviorism—originally disregards attitudes altogether. Behaviorism starts from the proposition that people, like many other animals, can be conditioned to respond in particular ways to specific “triggers,” or stimuli.12 In the early twentieth century Ivan Pavlov discovered that dogs could be conditioned to salivate in response to various sounds; “Pavlov’s dogs” remain famous to this day. 13 Pavlov studied how dogs behaved, but said nothing about dogs’ attitudes, if any, toward the sounds. However, psychologists discovered that people’s expressed attitudes as well as their behaviors could be conditioned. Behaviorists in the middle of the twentieth century reasoned that conditioning might be the main process of attitude change.14 If it was, then experimental research might lead to a comprehensive understanding of attitudes—and conditioning might make it possible to largely control people’s attitudes and behaviors.

Two variants of conditioning theories have been of special interest to public opinion scholars: classical conditioning and operant conditioning.

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning theory depends on a stimulus-response model.15 Take Pavlov’s experiments as an example. Suppose that dogs naturally salivate when they get meat; in the language of this model, salivation is an unconditioned response (UCR) to the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) of getting meat. In classical conditioning, dogs are conditioned to associate an initially neutral stimulus such as the sound of a bell—the conditioned stimulus (CS)—with the unconditioned stimulus of getting meat. Pavlov found that if he rang a bell each time he gave a dog meat, pairing these stimuli, eventually the dog would salivate whenever the bell rang, presumably because the dog associates the sound (the CS) with getting meat (the UCS). Salivation became a conditioned response (CR). (See Figure 5.2.)

But do people have anything in common with Pavlov’s dogs? Behaviorist researchers established that, yes, people also are amenable to classical conditioning. In one classic study, Arthur and Carolyn Staats presented research subjects with pairs of words: a national name projected on a screen and a word that was read to them. Supposedly, each subject’s task was to learn both sets of words. But Staats and Staats repeatedly paired the name Dutch with positive words such as gift and happy. They paired Swedish with negative words such as ugly and failure. And they paired the other national names with neutral words such as chair. At the end, subjects were asked to rate how they felt about each of the national names, on a scale from pleasant to unpleasant. Sure enough, on average, they felt more warmly about “Dutch” than “Swedish.”16 In this experiment, the response is an emotion or feeling—an evocation of attitude—rather than a manifest behavior.

FIGURE 5.2 An Example of Classsical Conditioning.

SOURCE: Adapted from Richard E. Petty and John T. Cacioppo, Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches (Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown Company, 1981), p. 41.

Conditioning surely occurs outside experimental settings. For example, as Alice Eagly and Shelly Chaiken17 describe, a child eventually learns the evaluative meaning of the words “good” and “bad” if these conditioned stimuli are repeatedly paired with unconditioned stimuli such as food or physical punishment. Classical conditioning provides a mechanism for inculcating group prejudice.18 Eagly and Chaiken describe how a child might acquire a negative attitude toward some minority group:

Imagine that the child hears a number of negative adjectives (e.g., bad, dirty, stupid) paired with the name of a particular minority group (e.g., blacks, Jews). In this application, the minority group name is the CS, and the negative adjectives are the UCSs. The UCSs are assumed to regularly evoke UCRs—in this case implicit negative evaluative responses. … With repeated pairings of the CS and the various UCSs, the minority group name comes to elicit … an implicit negative evaluative response, or negative attitude toward the minority group.19

Thus, there may be situations in which the Staats and Staats experiment could play out in real life, with potentially horrific consequences.

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning is based on the supposition that people act to maximize the positive and minimize the negative consequences of their behavior—and, by extension, their attitudes.20 We may come to adhere to attitudes that yield rewards and to reject attitudes that result in punishments.21 Figure 5.3 illustrates how such operant conditioning might work for individuals who are being indoctrinated into a cult.

In a classic example of operant conditioning from the 1950s, researcher Joel Greenspoon used verbal rewards to change what people would say.22 Subjects were asked to “say all the words that you can think of.” In one group, Greenspoon said “mmm-hmm” (a positive reinforcement) each time a subject used a plural noun; in a control group, Greenspoon said nothing. Subjects in the “mmm-hmm” group used about twice as many plural nouns as people in the control group—and almost all of them were unaware of what Greenspoon was doing. Many studies since then have used a similar approach.23 Other studies indicate that verbal conditioning really can change people’s attitudes, not just their word choice.24 However, in some cases what looks like unconscious conditioning may be simple compliance, “going along” with the experimenter without an underlying change in attitude.

Operant conditioning may have been one among many factors at work in Nazi Germany during the 1930s. German citizens were heavily rewarded for participating in activities deemed patriotic, such as saluting and attending Nazi rallies, and were severely punished for “incorrect” responses, particularly expressions of opposition to the Nazis. In the short run, these incentives tended to elicit compliance; over time, they may have led many people to feel real allegiance toward the Nazi regime.

FIGURE 5.3 An Example of Operant Conditioning.

SOURCE: Adapted from Richard E. Petty and John T. Cacioppo, Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches (Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown Company, 1981), p. 48.

In many contexts, conditioning (both classical and operant) sounds like dreadful manipulation—and if it works, it’s terrible news for democratic competence. Are we simply at the mercy of how we have been conditioned to respond? It turns out that conditioning offers a limited and flawed explanation of human behavior. A central premise of behaviorism is that people confronted with the same stimulus tend to respond in the same way. But in real life, people often respond differently, and attributing all those differences to conditioning is not helpful, if it is even plausible. If we are studying how, say, Democrats and Republicans respond differently to a speech about global warming, we certainly can’t explain these differences through conditioning alone, and in any event we don’t know how these people have been conditioned. A more realistic perspective is that conditioning is one among many of the ways that human beings can learn. It is clear that different kinds of theories may be more useful for scholars as they attempt to understand public opinion.

COGNITIVE PROCESSING: WHAT HAPPENS WHEN PEOPLE THINK

In our daily lives we are bombarded with information from various sources. Cognitive processing models (as well as some other models) construe this information as messages that our brains actively process or filter out. These approaches reject behaviorism’s model of unthinking response to a stimulus, but they also recognize that people do not pay equal attention to everything that happens around them.

The elaboration likelihood model (ELM) is a prominent example of cognitive processing approaches. Richard Petty and John Cacioppo25 developed this model in reaction to earlier “cognitive response” models, which they felt were too narrow. The model considers how people process messages that pertain to controversial issues, especially to messages intended to be persuasive. Elaboration refers to “the extent to which a person thinks about the issue-relevant arguments contained in a message.”26 Elaboration ranges from low—unthinking acceptance or rejection of the arguments—to high—complex thought processes such as active counterargumentation.

Petty and Cacioppo argue that a recipient of a persuasive message analyzes and evaluates issue-relevant information, comparing it to information already available in memory. Sometimes the recipient scrutinizes the message closely—elaboration is high—and relatively enduring attitude change may result. At other times the recipient of the message lacks the motivation or ability to process it closely, and elaboration is low. In that case, the recipient may then rely on peripheral factors, such as the attractiveness of the source or emotional appeal, for a more temporary attitude change. Or the recipient may discount the message entirely.

Crucially, the model considers influences on recipients’ motivation and ability. Motivation may be high when an issue seems directly relevant, when recipients feel a sense of personal responsibility, or when people are predisposed to think about such questions (called “need for cognition”). Ability may be high if a message is repeated, if it is readily comprehensible, if recipients have prior knowledge, and if they are relatively free from distractions. If either motivation or ability is low, then elaboration is unlikely. Figure 5.4 is a diagram of the elaboration likelihood model.

Consider the implications of this model for public opinion scholars and those who design persuasive messages. The ELM suggests that there are two ways to produce attitude change: (1) by encouraging people to do a great deal of thinking about the message (the central route) and (2) by encouraging people to focus on simple, compelling cues (the peripheral route), although the resulting change may be ephemeral. For example, in political campaigns, probably most voters will not be highly motivated to ponder the various candidates’ arguments and positions; for them, peripheral appeals may be more effective than elaborate policy arguments. However, some voters will be highly motivated, and they are more likely to be persuaded by more detailed arguments. Accordingly, campaigns may run frankly superficial campaign advertisements while providing extensive information on their Web sites.

Notice that the ELM serves primarily as a descriptive rather than an explanatory model.27 That is, the model does not explain “why certain arguments are strong or weak, why certain variables serve as (peripheral) cues, or why certain variables affect information processing.”28 Nevertheless, as Eagly and Chaiken note, “the model represents a powerful and integrative empirical framework for studying persuasion processes.”29

A related theoretical framework describes mental heuristics.30 Mental heuristics, essentially, are shortcuts for reaching a plausible (and perhaps sound) conclusion with far less effort than a complete cognitive analysis requires. For example, if I am deciding how to vote on a ballot issue, I may follow the opinion of a pundit I trust instead of doing my own research. Like the ELM and many other models, heuristic models assume that people think about their opinions, but also that they may not think very hard about those opinions. We say more about heuristics in later chapters.

FIGURE 5.4 The Elaboration Likelihood Model.

SOURCE: Adapted from Richard E. Petty and John T. Cacioppo, “The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion,” p. 126 in Leonard Berkowitz, ed., Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 19, 123–205. (San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1986).

CONSISTENCY AND JUDGMENTAL THEORIES: ATTITUDES COME IN PACKAGES

Attitudes are neither formed nor changed in a vacuum. The attitudes that we hold now affect the ways in which we process new information and assess persuasive messages. Existing attitudes form a frame of reference, a basis of comparison, for new ideas. Further, changing one attitude may result in changing a whole network of related attitudes. The models we have considered so far have relatively little to say about these interconnections; the theories we consider next place them front and center. Consistency theories describe how attitudes interact and how these attitudinal interactions are likely to affect opinion expression and attitude change. Judgmental theories emphasize how people’s attitudes influence the ways in which they interpret new information. Let us consider each in turn.

Consistency Theories

All consistency theories describe cognitions (beliefs, attitudes, and so on) as being consistent, inconsistent, or irrelevant to one another. According to Leon Festinger,31 two cognitions are consistent, or consonant, when one somehow “follows from” the other—perhaps according to logic, experience, or cultural norms. For example, “I love my children” is consonant with “I enjoy spending time with my children.” Two cognitions are inconsistent when the opposite of one cognition follows from the other: “I take good care of myself” is dissonant with “I eat lots of unhealthy foods.” Cognitions are mutually irrelevant when knowledge of one tells you nothing about what you might expect regarding the other—the belief that “the Dallas Cowboys are excellent” presumably has no bearing on whether “it will probably rain tomorrow,” or vice versa. Consonance and dissonance are subjective judgments. To many people, “I love my children” seems dissonant with “I often don’t enjoy my children at all,” although these cognitions might not be at all contradictory.

Balance Theory. Balance theory, formulated by Fritz Heider,32 applies consistency to triadic relationships among an observer and two other people or entities. Here is an informal, real-life example. One of our student advisees came to office hours to discuss a problem she was having with two of her roommates. She liked both roommates a great deal, and they liked her—but they disliked each other. As you would expect, this dynamic made everybody miserable. From the advisee’s point of view, obviously her roommates “should” just get along. Heider would say that she was experiencing tension caused by imbalance. The advisee might have eliminated the imbalance by getting her roommates to like each other (if possible); by “choosing sides” and beginning to dislike one of them; or by moving out, escaping the situation—which is what she decided to do.

Heider33 would present these relationships as shown in Figure 5.5. In Heider’s figures, P represents the perceiver (in this case, the advisee), O is some other person or entity, and X is either a third person or some attribute of O. So, in this case, O and X are the two roommates. The plus and minus signs in the figure indicate an attitude or relationship. Thus, (P + O) indicates that P likes O; (O – X) indicates that O and X are in conflict. Balance exists if all three signs in a triad are positive or if exactly two are negative (e.g., “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”). Otherwise, there is imbalance, and probably discomfort.

If balance theory seems far too simple, of course it is. (To be fair, Heider’s discussion is far more elaborate than our summary here.) Still, it is genuinely useful. Scholars have applied balance theory to phenomena such as how voters perceive candidates’ issue positions. For example, Jon Krosnick found that voters tend to be biased toward perceiving that candidates they like agree with the voters’ own positions on issues, and that disliked candidates disagree with those positions.34 Thus, individual voters seem to be trying to maintain a balanced triad among themselves, their candidates, and their issue positions. More recent examples of balance theory in practice include an analysis of consumer reactions to a cause-related marketing campaign.35

Congruity Theory. One obvious limitation of Heider’s balance theory is that it cannot distinguish degrees of liking or belonging among the elements. It does not “care” whether P is madly in love with O or faintly warm. Congruity theory, as presented first by Charles Osgood and Percy Tannenbaum,36 extends balance theory by allowing for gradations of liking—shades of gray. Messages that conflict with our prior attitudes can case “incongruity,” a state of cognitive imbalance. According to the model, people resolve these imbalances through what D. W. Rajecki describes as a compromise between the initial polarities. For example, “when a disliked person endorses a liked other, the resultant attitude will be the same toward both. By reason of association with each other, the person you initially disliked intensely will improve somewhat in your estimation.”37

FIGURE 5.5 An Illustration of Balance Theory.

SOURCE: Adapted from F. Heider, The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations (New York: Wiley, 1958).

Congruity theory accommodates the fact that we sometimes disagree with our friends or our political leaders and yet continue to like and support them.38 However, if our disagreements become more frequent or more important, we may decide to achieve balance by acquiring different friends, or supporting other political leaders, whose views are closer to our own.

Congruity theory has interesting applications in politics. Research has shown that not only do people tend to like politicians who agree with them on some issue, but they tend to move toward the issue positions of politicians they like. Eagly and Chaiken39 discovered that American politicians behaved like congruity theorists. That is, politicians tended to (1) associate themselves with popular causes, (2) disassociate themselves from unpopular causes, and (3) avoid taking positions on issues on which voters are sharply divided. Politicians often behave in these ways toward issues that they cannot personally influence, and even on purely symbolic issues such as what baseball team they support.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory. Cognitive dissonance arises when an individual’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors are not aligned. Since Festinger’s book A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance was published in 1957, well over 1,000 studies of cognitive dissonance have been published. These studies have assessed various aspects of Festinger’s theory, challenged hypotheses derived from the theory, and related it to different contexts, including marketing and religion.40 As we have seen, Festinger argued that two cognitions could be dissonant, that is, mutually inconsistent. He further argued that cognitive dissonance—awareness that one’s cognitions are at odds—causes discomfort, and so people act to reduce it. For example, I may feel that eating ice cream makes life worth living and also believe that it is bad for my health. Every time I see ice cream, or even think of it, I may feel conflicted: “I really want that! I really shouldn’t have it!” If I can find a way to avoid that conflict, I will. Recent work has also looked at exercise motivation through the lens of cognitive dissonance.41

How people deal with cognitive dissonance will partly depend on the intensity of the cognitions and the value people attach to them. If I highly value eating ice cream and really don’t think much about my health—or don’t think that ice cream is very dangerous—then I will probably keep eating ice cream. Conversely, if I place a high value on “eating healthy,” then I will probably stop. Dissonance is at its most powerful when the two cognitive elements are important and evenly valued—if I am really worried about my health but I really love ice cream.

Festinger describes three basic ways to reduce dissonance:

1. A person can change one of the cognitions so that the relationship becomes consonant. For example, I might convince myself that eating ice cream is safe after all—or, on the contrary, I might convince myself that, actually, apples are far tastier and more refreshing.

2. A person can “add” consonant cognitions to one side. For example, I may tell myself that when I eat ice cream, I am happier, more productive, maybe even more likely to exercise, and I get more calcium—so surely, overall, I am better off eating ice cream than not.

3. A person can alter the importance of the cognitions. For example, if I can avoid ice cream for a while, although I will not stop liking it, I may at least think less about how much I like it.

It is clear that cognitive dissonance is an important psychological state for researchers to study so they can determine how people react when faced with conflicting cognitive elements.42 But how does cognitive dissonance apply specifically to public opinion research? Fundamentally, it is a deceptively simple idea that tends to complicate our assumptions about people’s goals. As Festinger analogizes, cognitive dissonance leads one to actively reduce dissonance, as hunger inspires one to reduce hunger. This is a subtle yet powerful motivation, although it is difficult to tell just how powerful. Often we think of people as seeking safety, prosperity, love, and friendship; to think of them as trying to minimize internal conflict may shed a different light on many opinions and behaviors.43 Also, we can consider cognitive dissonance as a potential cause of opinion change—not only within individuals, but in the wider public. Changing attitudes on various social issues can be considered instances of many individuals experiencing and working through cognitive dissonance.

Judgmental Theories: Adaptation Level Theory and Social Judgment Theory

The underlying principle of most judgmental theories is that all stimuli can be arranged in some meaningful order on a psychological dimension. That is, attitudes toward an object can be arranged from the most negative (unfavorable) to the most positive (favorable) in the same way people might be arranged from most attractive to least attractive, shortest to tallest, and so forth. How positive or negative something feels or how it is rated on an attitude scale depends on the frame of reference.44 That is, our past experiences play an important role in the ways that we interpret new information.

In adaptation level theory, a person’s adaptation level is that point on the dimension of judgment that corresponds to the psychological neutral point. As Petty and Cacioppo explain, “If you were to put your hand in a bucket of very cold water, eventually your hand would adapt to the water temperature so that the cold water would feel neutral or normal. Subsequent judgments of how cold or warm another bucket of water felt would be made relative to the water temperature to which your hand had previously adapted.”45 Adaptation level is important because other stimuli we experience are judged in relation to this level, which serves as an anchor or reference point.

Philip Brickman, Dan Coates, and Ronnie Janoff-Bulman conducted an interesting study on adaptation level theory, testing the proposition that extremely positive events do not increase one’s overall level of happiness.46 Brickman and associates asked people who had won from $50,000 to $1,000,000 in the Illinois state lottery how pleasant they found seven ordinary events like watching television and eating breakfast. People in a control group of nonwinners were asked the same questions. Brickman and associates suggested that this positive event—winning the lottery—should raise the winners’ adaptation level so that more mundane events become less pleasurable than they used to be. Indeed, lottery winners rated these events as less pleasant than the controls, even though earlier studies had found no differences in overall pleasure ratings between the two groups.

The researchers speculated that the extra pleasure of winning the money is offset by the decline in pleasure from ordinary events. Indeed, we have a similar personal example to share. An accountant one of us knows won the state lottery—$18 million. And when the accountant-turned-millionaire, who is now able to enjoy the finer things of life, was asked if the pleasure of eating breakfast was reduced since winning the lottery, she answered, “Not on my [new] front porch!”

Social judgment theory assumes that people tend to arrange stimuli in a meaningful order; however, it posits that these stimuli are subject not only to contrast effects, but also to assimilation effects. That is, people interpret (and often distort) each other’s attitudes, using their own attitudes as a reference point or anchor. Attitudes that are relatively close to one’s own are assimilated (seen as closer than they actually are), but attitudes that are quite discrepant from one’s own are contrasted (seen as further away than they actually are).47

How do we develop such misperceptions? Social judgment theory posits that people divide each attitudinal dimension—the spectrum of possible attitudes on some subject—into three “latitudes.” The latitude of acceptance includes the range of attitudes that people find acceptable—attitudes not too far from their own. The latitude of rejection comprises the range of opinions that they find objectionable. Finally, the latitude of noncommitment comprises the remaining positions: attitudes that people do not find immediately acceptable or unacceptable.

If someone else’s expressed attitude falls within my latitude of acceptance, I am likely to assimilate it as a reasonable position not far from my own. I also am more likely to change my own attitude, moving toward the other person’s—splitting the difference, so to speak. On the other hand, if someone else’s expressed attitude falls in my latitude of rejection, I am likely to contrast it, and my own attitude may move even further in the opposite direction. Attitudes in the latitude of noncommitment are most likely to be perceived accurately and least likely to produce attitude change in either direction. For example, say that you and a friend are discussing the issue of abortion. Assimilating your friend’s attitude on abortion toward your own attitude would probably make you regard your friend’s statements as “fair,” “unbiased,” and so forth, increasing the likelihood of attitude change. However, contrasting your friend’s attitude on abortion would likely lead you to regard your friend’s statements about abortion as “unfair” or “biased,” reducing the likelihood that your attitude will change.

Of course, there are many theories from psychology that deal with how people process information to form their own attitudes and opinions. We have presented only a few to give you an idea of how the psychology of the individual can have a profound impact on the opinions of the whole. The fields of social psychology, sociology, and communication have provided even more rich theoretical perspectives to examine. While providing such a list of theories can seem overwhelming, each contributes to the understanding of public opinion in unique ways. We consider some of the more important contributions below.

MOTIVATIONAL THEORIES: SAME ATTITUDE, DIFFERENT REASON

Why do we hold the opinions we do? Consistency theories suggest one set of subtle reasons: for example, to minimize the discomfort caused by cognitive dissonance. But there are many reasons for holding opinions. In the 1950s two separate groups of investigators elaborated so-called functional theories about the diverse reasons behind human attitudes. Other theories describe and explain how our concerns about our own self-image affect the attitudes we hold and the opinions we express. One of these theories, impression management theory, is discussed here because of its close links to cognitive dissonance theory. Several related theories are discussed in the following chapters.

Functional Theories

Functional theories posit that people tend to form attitudes that serve various functions. These theories do not necessarily explain how people form functional attitudes; they do not assume that people consciously choose attitudes to be functional. For example, Daniel Katz’s 1960 article “The Functional Approach to the Study of Attitudes”48 describes four functions that attitudes might serve for a person:

1. Adjustment (utilitarian): People tend to form attitudes that help them to gain rewards and avoid penalties—stated in economic language, to maximize their net utility. If I burn myself on a hot stove once, I will probably henceforth be wary of hot stoves. If studying on a test helps me earn a high score—and if I value scoring highly on tests—I will probably have a warmer attitude toward studying. The adjustment function depends on perceptions of utility: I may come to love a “lucky shirt” if I believe it is possible for shirts to bring luck.

2. Ego-defensive: People can deploy attitudes to protect themselves from unflattering truths about themselves and “harsh realities in [their] external world.”49 For example, someone whose careless driving causes an accident may become angry at the car, the weather, the other driver—anything that helps deflect responsibility for driving badly. Or someone stuck in a bad job may blame “the welfare cheats,” when in fact good jobs are scarce for reasons that have nothing to do with welfare programs.

3. Value-expressive: Sometimes people’s attitudes express their values. A young person who values independence from adult conventions may prefer “edgy” clothes as an expression of that value. People who consider themselves environmentalists may be willing to pay extra for hybrid cars because they feel it is the green thing to do. (To an observer, a value-expressive attitude may seem completely reasonable or rather silly, but that is irrelevant to the theory. The theory considers how attitudes are functional, not whether they are rational.)

4. Knowledge: Katz writes that people “seek knowledge to give meaning to what would otherwise be an unorganized chaotic universe.”50 Knowledge in this sense may not be objectively true; its function is to help people feel that they understand their world, where they fit in it, and how they should behave in it. For example, people’s attitudes about romantic relationships help them know how to behave—but what two people “know” about love may be sharply contradictory.

Functional theories such as Katz’s imply that attempts at persuasion—changing other people’s attitudes—should be informed by an understanding of what function(s) the attitudes serve. Consider a public health official who is designing a campaign to persuade smokers to quit. One obvious approach is to try to change their attitude that smoking is an acceptable choice by educating them about the dangers of smoking. That may work for smokers who know little or nothing about why smoking is dangerous; they may well be willing to learn (the knowledge function) and change their attitudes accordingly. However, most smokers already know that smoking is dangerous; an attempt to “educate” them is not likely to help. A smarter approach looks for deeper insights into smokers’ attitudes and how they are functional.

For example, many smokers express the attitude that once you start smoking, there isn’t much point in stopping—at least right now—because smoking isn’t that dangerous, and smoking for one more day or week or month or year doesn’t really matter. This attitude can serve an ego-defensive function: smoking is addictive, and many smokers have tried and failed to quit, so it is functional (in one sense) to believe that there is little point in trying again. Smokers who believe that may pooh-pooh an attempt to scare them or may simply feel worse about the long-term consequences of their behavior without seeing any reason to change now. Recent smoking cessation advertisements take a different approach. First, they state that in fact, people who stop smoking now can expect large health improvements fairly soon. Second, they reassure smokers that they really can quit, and that it doesn’t matter how many times they have tried to quit in the past. Thus, the ads not only challenge a rationalization for continuing to smoke, but also address the fear behind the rationalization.

Critics of functional theories often complain that they are ad hoc. Who can determine which functions really matter, for which people, at which times? Scholars other than Katz have described functional approaches to the study of attitudes, including, among others, Herbert Kelman;51 Mehta R. Grewal and F. R. Kardes;52 and M. Brewster Smith, Jerome Bruner, and Robert White53—whose do you choose? These and related questions are fair ones, but we do not have to wrestle with them here. We believe that thinking of attitudes as (at least possibly) functional, rather than as personality quirks or straightforward reactions to information and experience, is worthwhile even if no one theory is entirely satisfactory.

Impression Management Theory

Impression management theory can be construed as a functional theory of attitude and behavior that posits one prime function: people present an image to others in order to achieve a particular goal—most often, to attain social approval.54 Whereas cognitive consistency theories assume that people strive for internal consistency, impression management theory assumes that people strive to convey as positive and consistent an external image as possible, even if that image is inconsistent with their internal attitudes.

In fact, James Tedeschi, Barry Schlenker, and Thomas Bonoma55 proposed impression management theory as an alternative to dissonance theory. As Schlenker states: “Irrespective of whether or not people have psychological needs to be consistent … there is little doubt that the appearance of consistency usually leads to social reward, while the appearance of inconsistency leads to social punishment.”56 Usually, if researchers can detect an instance of apparent cognitive dissonance, the people they are studying also realize that they appear inconsistent to others. People are likely to avoid such inconsistencies if they can or to work harder on impression management if they notice that they have slipped up.57

For example, if I say that people should always honor their civic obligations, I would probably also say that I would gladly serve jury duty if asked. Even if, in truth, I would try to avoid serving jury duty, or would complain bitterly about it, I am unlikely to say so in public—not because I would then wrestle with cognitive dissonance, but because I would look like a petty hypocrite. If I happen to blurt out something negative about jury duty, I would probably backtrack (perhaps by saying, “Still, someone has to do it”)—again, not to restore “balance,” but just to look better. Meanwhile, in another social setting I might sound a lot more cynical about civic obligations in general, and jury duty in particular, in order to fit in better.

Impression management theory provides one account of the obvious: participants in public opinion research may fudge, mislead, or even lie outright to appear more favorable in the eyes of the researcher. This phenomenon is known as social desirability bias. Even in an anonymous survey, people may all but swear that they will vote, when in fact the odds are against it. Or they may answer questions about racial attitudes in ways that they think will appeal to the interviewer. This behavior is not necessarily intended to be deceptive; all of us sometimes try to choose our words so as not to offend other people. Researchers always have to reckon with the possibility of social desirability bias.

LINKS BETWEEN ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIOR: WHAT PEOPLE THINK AND WHAT THEY DO

Social desirability bias frames a problem: What is the relationship between attitudes and behavior, between what people think—or, really, what they say they think—and what they do? As we mentioned, people often say they will vote, and then don’t. But many questions about attitudes and behavior are more subtle. How well do Army recruits’ statements about eagerness for combat predict their actual combat performance? If people say they intend to donate bone marrow, how likely are they to do so? When women are asked whether they want more children, how well do their answers predict whether they bear another child? Howard Schuman and Michael Johnson, summarizing the results of studies on these and other topics, say that the associations between attitudes and behaviors “seem to vary from small to moderate in size”: strong enough to be worth considering, but far from strong enough to confidently predict individuals’ behaviors. Some researchers have questioned whether there is much point in studying attitudes at all, if one wants to understand actual social behavior.58 We think there is importance to this line of research. But why then are the relationships between attitudes and behaviors so intricate at best?

Measurement Issues

As we have already considered in Chapter 3, there are many methodological problems in public opinion research. Studies of the links between attitudes and behavior pose some special difficulties. One is that different research methods seem to produce contradictory evidence. Kelman notes that survey-based studies often indicate stronger relationships than experimental studies that examine people’s actual behavior in research settings.59 In general, many researchers give more credence to experimental studies than to survey studies in which people simply self-report their behaviors.60 However, many topics are not amenable to experimental study. Eagly and Chaiken suggest that survey research often examines attitudes that “are more important and involving”—and therefore, perhaps, more influential—than in most experimental studies.61

Intuitively, some attitudes are better suited to predicting particular behaviors than others. Icek Ajzen formalized this intuition as the principle of correspondence: attitudes best predict behaviors when they correspond to the behaviors “in terms of action, target, context, and time elements.”62 For example, people’s general attitude about environmental protection may not strongly predict their willingness to donate to an environmental group such as the Sierra Club. After all, giving money to the Sierra Club doesn’t directly protect anything. People’s attitudes about the effectiveness of the Sierra Club may better predict their willingness to donate to it.

Individual Differences

Individual differences can account for some inconsistencies in attitude–behavior relationships. You probably have some friends who exhibit high consistency between their attitudes and behaviors. If they tell you they think something, you can almost rest assured that their actions will be true to their words. However, you can probably think of just as many or more friends whose behaviors are much less consistent with their attitudes. They may say one thing and act in a completely different way.

As Perloff notes, your friends who fit the latter category may have a strong attitude about an issue, but they might withhold their opinion or may take the opposing viewpoint.63 You may even know some habitual “devil’s advocates” who wait to hear what other people say, then routinely disagree with the majority opinion. Perloff describes two key individual differences that influence this consistency (or lack thereof) between attitudes and behaviors: self-monitoring and direct experience.

Mark Snyder developed the self-monitoring concept, which he describes as “the extent to which people monitor (observe, regulate, and control) the public appearances of self they display in social situations and interpersonal relationships.”64 Snyder developed a scale that classifies people as high self-monitors or low self-monitors. As Perloff notes:

High self-monitors are adept at controlling the images of self they present in interpersonal situations, and they are highly sensitive to the social cues that signify the appropriate behavior in a given situation. … Low self-monitors are less concerned with conveying an impression that is appropriate to the situation. Rather than relying on situational cues to help them decide how to act in a particular situation, low self-monitors consult their inner feelings and attitudes.65

Thus, high self-monitors are more likely to express public opinions that are different from their private opinions. Low self-monitors are likely to have private and public opinions that match, and so their attitudes may better predict their behaviors.66

Moreover, attitudes based on direct experience may predict behaviors better than other attitudes do. Russell Fazio and Mark Zanna assert that attitudes based on direct experience are “more clearly defined, held with greater certainty, more stable over time, and more resistant to counter influence.”67 For example, if a five-year-old says he is “never gonna do drugs,” he is more likely basing this statement on television advertisements he has seen and on comments made by his teachers, rather than on having seen his friends “do drugs.” Based on the research by Fazio and Zanna, the five-year-old’s statement would be more meaningful and would be more likely to predict his behavior if he had actually witnessed a friend having a bad physical reaction to a drug.

Social and Situational Factors

Many social factors, such as cultural norms, may affect the linkages between attitudes and behavior. A classic study from 1934, explained in Box 5.1, demonstrates how social norms may affect attitude expression—in this case, how the norm of politeness may prevent people from acting on prejudiced attitudes.

When do attitudes predict behaviors? It is clear that there are a lot of cognitive and situational factors that must be considered in order to answer this question. One such concept related to the attitude–behavior relationship is attitude accessibility.68 That is, attitudes are thought to guide behavior partially through the perception process. Attitudes that are highly accessible (i.e., that come to mind quickly) are thought to be more likely to guide perception and therefore behavior. Studies indicate that more accessible attitudes predict behavior better than less accessible ones, independent of the direction and intensity of attitude expression.69 Thus, knowing how quickly someone can express an attitude or opinion can provide useful information about how that person is likely to behave.

Theory of Planned Behavior

Naturally some researchers have grappled with the attitude–behavior problem by developing more complex models. Icek Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, which is based on Martin Fishbein and Ajzen’s theory of reasoned action, illustrates this general approach.

Traveling America: Weak Links Between Prejudiced Attitudes and Prejudiced Behavior

In 1930 sociologist Richard LaPiere visited a hotel “in a small town known for its narrow and bigoted ‘attitude’” toward Chinese people. LaPiere was traveling with a young Chinese student and his wife, whom he describes as “personable [and] charming.” The hotel clerk accommodated them without hesitation. Two months later, he called the same hotel to ask if they could accommodate “an important Chinese gentleman.” The response was “an unequivocal ‘No.’”1 Curious, LaPiere arranged with the student and his wife to conduct an extensive field study over the next two years. Of this study, LaPiere notes:

In something like ten thousand miles of motor travel, twice across the United States, up and down the Pacific Coast, we met definite rejection … just once. We were received at 66 hotels, auto camps, and “Tourist Homes,’ refused at one. We were served in 184 restaurants and cafes scattered throughout the country and treated with what I judged to be more than ordinary consideration in 72 of them.2

Six months after the trip, LaPiere sent each of these establishments a questionnaire that asked, “Will you accept members of the Chinese race as guests in your establishment?” Remarkably, 92 percent of the establishments that responded said that they would not accept Chinese. All but one of the rest said that it would depend on circumstances. Yet in fact, almost all these places had accepted Chinese guests—even in dozens of cases in which LaPiere sent the couple ahead, to ensure that proprietors were not simply deferring to him.

Strictly speaking, LaPiere’s question did not measure an “attitude,” but most people would agree that the responses evinced anti-Chinese prejudice. Why wasn’t this prejudiced attitude manifest in proprietors’ behavior? Donald T. Campbell suggests3 that, face to face, the attitude was trumped by a prevailing social norm of politeness. Answering “no” to a written survey question hardly seems rude; telling particular people, to their faces, that they must leave is rude in the extreme. Thus, the subjective cost of expressing prejudice is much greater in person than in responding to the questionnaire. Campbell’s explanation is both social and situational: it posits that how people act on their attitudes may crucially depend on the specific circumstances.

Another possible explanation is that the Chinese couple did not trigger the negative attitude that the proprietors associated with the words “members of the Chinese race.” Many Americans harbor negative attitudes toward various social groups in the abstract: “convicted criminals,” “illegal immigrants,” or “Tea Party supporters.” Yet they may respond warmly to people who in fact belong to some group they disparage. To paraphrase LaPiere, people’s reaction to a “symbolic social situation” may have little or no bearing on their reaction to “real social situations.”4

SOURCES: Richard T. LaPiere, “Attitudes vs. Actions,” Social Forces 13 (1934): 230–237; Donald T. Campbell, “Social Attitudes and Other Acquired Behavioral Dispositions,” in Psychology: A Study of Science, ed. S. Koch (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963), 94–172.

1Richard T. LaPiere, “Attitudes vs. Actions,” Social Forces 13, no. 2 (December 1934): 231–232.

2Ibid., 232.

3Donald T. Campbell, “Social Attitudes and Other Acquired Behavioral Dispositions,” in S. Koch, ed., Psychology: A Study of Science (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963), 94–172.

4LaPiere, “Attitudes vs. Actions,” 233.

First consider the theory of reasoned action, which attempts to explain voluntary behaviors. This theory assumes that people rationally calculate the costs and benefits of various actions. In evaluating a possible behavior, people consult their attitudes toward the behavior, including beliefs about its consequences. They also consult subjective norms: whether (they believe) other individuals and groups think the behavior should or should not be performed. These factors influence their behavioral intentions, and ultimately, their actual behavior.70

In general, the theory of reasoned action predicts that people will behave in ways that lead to favorable outcomes and that meet the expectations of others who are important to them. This makes sense; after all, most of us want to get along with others in this world and would also like social, financial, or other rewards. At the same time, the theory has obvious limitations. For example, it takes no account of situational characteristics such as people’s access to information. Even so, it has been usefully applied to various topics, including voting and presidential elections,71 family planning,72 and consumer product preferences.73

Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior (see Figure 5.6) was developed to help account for a wider range of behaviors, including those that are mandated or that may result from situations outside of the person’s control. The theory posits that all behaviors can be regarded as goals, which may or may not be achieved. For example, you may have the goal of voting in an election, which may be frustrated if your car breaks down on the way to vote. One crux of this theory is the person’s perceived behavioral control: one’s perception of how easy or difficult it is to perform the action. As shown in Figure 5.6, perceived behavioral control affects behavior in two ways: it influences the intention to perform the behavior, and it may have a direct impact on the behavior.

Obviously the theory of planned behavior can be applied to many kinds of behaviors. People may vote, and express political opinions, very differently if they have subjective norms in mind than if they are simply speaking their minds.

FIGURE 5.6 Theory of Planned Behavior.

SOURCE: Adapted from Icek Azjen, “The Theory of Planned Behavior,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 (1991):182.

In most of the preceding discussion, attitudes and behaviors have appeared to be straightforward computations or even reflexes. While early psychology texts, such as William James’s The Principles of Psychology,74 devoted considerable attention to emotional processes, behavioralist theories had no use for them. When behavioralism began to wane in the 1950s, the attention turned to computer metaphors: information processing, logical consistency, decisionmaking algorithms.

However, more recently researchers have been studying mood and emotions from many different perspectives and backgrounds, including investigations of the role of emotions in approval of politicians and perspectives on social issues75 They find that emotions play a crucial role in how we act, what we think, and who we are—and therefore, in every manifestation of public opinion. It is difficult to imagine an election cycle in American politics without also thinking of the constant barrage of negative—and often fear-inducing—messages that dominate media advertising. Rather than focus on the positive qualities of candidates or issues, much time and effort is spent painting the opposition—whether a candidate or those opposed to an issue—in the poorest light possible. While voters typically complain about such “gutter politics,” these emotional appeals have proven effective and therefore remain a key component of many close political contests. We briefly consider two major efforts to integrate emotion: the cognitive and the social approaches.

Cognitive Approaches

Cognitive approaches to emotion seek to determine how emotions develop and how they interact with what we typically think of as cognition, or logical, conscious thought processes. Robert Zajonc, a leader in this area, focused on the relationship between thinking and feeling, or affect. Zajonc posited that information processing models in which cognition precedes affective evaluation were fundamentally wrong. He argued that affect is ubiquitous—the “major currency” of social interaction—and that it probably precedes cognition.76 People have emotional reactions before they know why. Sometimes people never even consider why, and if they do, they may misunderstand the reasons. Public opinion polls that ask people’s opinions on various issues, without tapping their feelings, may fundamentally misrepresent their views.

Researchers suggest that emotions and cognition work in tandem to motivate our attitudes and behavior. For example, Lyn Ragsdale has studied people’s emotional reactions to presidents. Ragsdale found that people seem to weigh the emotional aspects of evaluation at least as strongly as the presidents’ stands on issues or their economic situation—indeed, more strongly.77 This result is alarming if we assume that people’s emotions are contrary to reason. But emotions may convey information about other people—including presidents—that is valuable even if it isn’t readily translated into dispassionate cognitions.78

Social Approaches

A very different perspective on emotions is provided by social psychologists who examine what are called social emotions, including embarrassment, pride, and shame. Over a century ago, Charles Cooley was among the first psychologists to describe the social role of emotions.79 Cooley centered on pride and shame as managing devices that helped maintain a social bond and even hold the social system together. Writing in this tradition, Rowland Miller and Mark Leary80 and Thomas Scheff81 argue that many emotions are social emotions, as they usually arise from interactions with other people.82

These social emotions depend on the implied presence and attention of others. They depend on our concern about what others are thinking of us, and they would not occur if we were unaware of others’ presence or did not care what others thought.83 As such, these emotions surely lie at the root of the social comparison processes we discuss in Chapter 7, such as false consensus, although they are rarely considered as such. More recently, public opinion scholars have found other relationships between emotion and opinion outcomes.84

It is interesting to note that both social and cognitive perspectives suggest the important link between emotions and the separation of humans from other animals. It is no coincidence that one of the first scientists to describe the role of emotion in both cognitive and social perspectives was Charles Darwin, who devoted an entire book to the interplay of biology, emotion, and communication.85 It is clear that emotion—whether approached from a cognitive or a social perspective—is increasingly playing an important role in public opinion research.

Beliefs and values generally affect the attitudes we hold, which are expressed as opinions. Much research has focused on how people form their attitudes. Early studies focused on the behaviorist views of classical and operant conditioning. More recent research has rejected conditioning’s premise that all individuals will respond in the same way to the same stimulus and has developed several alternative explanations.

Cognitive response theories assume the brain is sorting through much information, ignoring or rejecting some and using the rest to derive opinions. The Elaboration Likelihood Model and the theory of heuristics attempt to describe this cognitive process by emphasizing the notion that we are constantly taking mental shortcuts to make decisions, form opinions, and process the vast amount of information that comes our way.

Attitudes are also studied in relationship to one another. Consistency and judgment theories focus on the interdependent relationship of attitudes. Cognitive dissonance and social judgment theories are among the most well known in this category. Researchers are also interested in functional aspects of opinion expression—determining what motivations are involved when forming and expressing opinions. Some hold that the individual’s goal is to achieve consistency in attitudes held. Others argue that the individual goal is social approval, causing one to choose the position he or she considers most favored by an important social group.

Emotions also play a role in the development of public opinion. Zajonc’s work in particular argues that affect has an influence on, and can be a precursor to, opinion. The study of emotion can have profound implications for the study of public opinion.

Individuals certainly have some similarities in how opinions are formed and maintained, but there are also key differences in how people collect information and choose which information and knowledge to value, as well as the role that emotions play in opinion formation. Public opinion can be thought of as an outcome of cognitions, emotions, and key social interactions. Though it makes analyzing the public opinion process more complicated, many who study public opinion now acknowledge that an “all of the above” approach is probably the most appropriate way to think of the entire system of opinion formation. While there are certainly individual and rational factors in play, the public opinion is heavily influenced by social factors and pressures. Perhaps it is best to think about public opinion arising at the intersection of cognitions, emotions, and social forces—a subject we cover in the next chapter.

NOTES

1. Richard M. Perloff, The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the 21st Century, 4th ed. (New York: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2010), 46.

2. Philip E. Converse, “Information Flow and the Stability of Partisan Attitudes,” Public Opinion Quarterly 26, no. 4 (1962): 578–599.

3. Milton Rokeach, The Nature of Human Values (New York: Free Press, 1973).

4. Ken-Ichi Ohbuchi, Osamu Fukushima, and James T. Tedeschi, “Cultural Values in Conflict Management—Goal Orientation, Goal Attainment, and Tactical Decision,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 30 (1999): 51–71.

5. Stephen F. Davis, Patrick F. Drinan, and Tricia Bertram Gallup, Cheating in School: What We Know and What We Can Do (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

6. Robert B. Cialdini, Richard E. Petty, and John T. Cacioppo, “Attitude and Attitude Change,” Annual Review of Psychology 32 (1981): 357–404. See also Daryl J. Bem, Beliefs, Attitudes, and Human Affairs (Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, 1970); and Stuart Oskamp, Attitudes and Opinions (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1977).

7. Alice H. Eagly and Shelly Chaiken, “Attitude Structure and Function,” in D. T. Gilbert, Susan T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey, eds., Handbook of Social Psychology (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998), 269–322.

8. Icek Ajzen, “Nature and Operation of Attitudes,” Annual Review of Psychology 52 (2001): 27–58; Martin Fishbein, “An Investigation of the Relationships between Beliefs about an Object and the Attitude toward That Object,” Human Relations, 16, no. 3 (1963): 233–239.

9. Perloff, Dynamics of Persuasion; Milton J. Rosenberg and Robert P. Abelson, “An Analysis of Cognitive Balancing,” in Milton J. Rosenberg et al., eds., Attitude Organization and Change (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1960), 112–163; Steven J. Breckler, “Empirical Validation of Affect, Behavior, and Cognition as Distinct Components of Attitude,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 47, no. 6 (1984): 1191–1205.

10. Bernard C. Hennessy, Public Opinion, 5th ed. (Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, 1985).

11. Louis Leon Thurstone and E. U. Chave, The Measurement of Attitude (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1929), 7.

12. Clark L. Hull, Principles of Behavior: An Introduction to Behavior Theory (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1943); Edward L. Thorndike, The Fundamentals of Learning (New York: Teacher’s College Press, 1932).

13. I. P. Pavlov, Conditioned Reflexes (New York: Dover Publications, 1927/2003).

14. B. F. Skinner, The Behavior of Organisms (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1938).

15. Jodene R. Baccus, Mark W. Baldwin, and Dominic J. Packer, “Increasing Implicit Self-esteem through Classical Conditioning,” Psychological Science 15, no. 7 (2004): 498–502. See also Christina Dalla and Tracey J. Shors, “Sex Differences in Learning Processes of Classical and Operant Conditioning,” Physiology & Behavior 97, no. 2 (2009): 229–238.

16. Arthur W. Staats and Carolyn K. Staats, “Attitudes Established by Classical Conditioning,” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 57 (1958): 37–40. See also Arthur W. Staats, “Paradigmatic Behaviorism: Unified Theory for Social-Personality Psychology,” in Leonard Berkowitz, ed., Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (San Diego: Academic Press, 1983), 125–179.

17. Alice H. Eagly and Shelly Chaiken, The Psychology of Attitudes (Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1993).

18. Shmuel Lissek, Alice S. Powers, Erin B. McClure, Elizabeth A. Phelps, Girma Woldehawariat, Christian Grillon, and Daniel Pine, “Classical Fear Conditioning in the Anxiety Disorders: A Meta-analysis,” Behaviour Research and Therapy 43, no. 11 (2005): 1391–1424.

19. Eagly and Chaiken, Psychology of Attitudes, 400.

20. Skinner, Behavior of Organisms.

21. See, e.g., Richard E. Petty and John T. Cacioppo, Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches (Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown, 1981).

22. Joel Greenspoon, “The Reinforcing Effect of Two Spoken Sounds on the Frequency of Two Responses,” American Journal of Psychology 68 (1955): 409–416.

23. For example, see Leonard Krasner, “Studies of the Conditioning of Verbal Behavior,” Psychological Bulletin 55 (1958): 148–170; Leonard Krasner, “The Therapist as a Social Reinforcement Machine,” in Hans H. Strupp and Lester Luborsky, eds., Research in Psychotherapy (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1962), 61–94; Leon H. Levy, “Awareness, Learning, and the Beneficent Subject as Expert Witness,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 6 (1967): 365–370; and Richard D. Singer, “Verbal Conditioning and Generalization of Prodemocratic Responses,” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 63 (1961): 43–46.

24. Some of these studies are described in Petty and Cacioppo, Attitudes and Persuasion.

25. Richard E. Petty and John T. Cacioppo, “The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion,” in Leonard Berkowitz, ed., Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (New York: Academic Press, 1986), 19:123–205.

26. Ibid., 128.

27. Richard E. Petty, Pablo Briñol, and Joseph R. Priester, “Mass Media Attitude Change: Implications of the Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion,” in Jennings Bryant and Mary Beth Oliver, eds., Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2009), 125–164. See also Shu-Hui Chen and Kuan-Ping Lee, “The Role of Personality Traits and Perceived Values in Persuasion: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Perspective on Online Shopping,” Social Behavior and Personality 36, no. 10 (2008): 1379–1399.

28. Petty and Cacioppo, “Elaboration Likelihood Model,” 192.

29. Eagly and Chaiken, Psychology of Attitudes, 323.

30. A classic discussion is Shelly Chaiken, “The Heuristic Model of Persuasion,” in Mark P. Zanna, James M. Olson, and C. Peter Herman, eds., Social Influence: The Ontario Symposium (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1987), 3–39.

31. Leon Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson, 1957), esp. 11–15.

32. Fritz Heider, “Attitudes and Cognitive Organization,” Journal of Psychology 21 (1946): 107–112.

33. Fritz Heider, The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations (New York: Wiley, 1958).

34. Jon A. Krosnick, “Psychological Perspectives on Political Candidate Perception: A Review of Research on the Projection Hypothesis” (paper presented at the meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, 1988).

35. Debra Z. Basil and Paul M. Herr, “Attitudinal Balance and Cause-related Marketing: An Empirical Application of Balance Theory,” Journal of Consumer Psychology 16, no. 4 (2006): 391–403. See also Christian S. Crandall, Paul J. Silvia, Ahogni N. N’Gbala, Jo-Ann Tsang, and Karen Dawson, “Balance Theory, Unit Relations, and Attribution: The Underlying Integrity of Heiderian Theory,” Review of General Psychology 11 (2007): 12–30, doi: 10.1037/1089–2680.11.1.12.

36. Charles E. Osgood and Percy H. Tannenbaum, “The Principle of Congruity in the Prediction of Attitude Change,” Psychological Review 62 (1955): 42–55.

37. D. W. Rajecki, Attitudes, 2nd ed. (Sunderland, MA: Sinauer, 1990), 64.

38. Ahmet Usakli and Seyhmus Baloglu, “Brand Personality of Tourist Destinations: An Application of Self-congruity Theory,” Tourism Management 32, no. 1 (2011): 114–127.

39. Alice H. Eagly and Steven J. Karau, “Role Congruity Theory of Prejudice toward Female Leaders,” Psychological Review 109, no. 3 (2002): 573–598.

40. Richard M. Perloff, The Dynamics of Persuasion (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1993).

41. Nikos L. D. Chatzisarantis, Martin S. Hagger, and John C. K. Wang, “An Experimental Test of Cognitive Dissonance Theory in the Domain of Physical Exercise,” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 20 (2008): 97–115.

42. For a review of cognitive dissonance theory research see Eddie Harmon-Jones and Cindy Harmon-Jones, “Cognitive Dissonance Theory after 50 Years of Development,” Zeitschrift fÜr Sozialpsychologie 38 (2007): 7–16.

43. George A. Akerlof and William T. Dickens, “The Economic Consequences of Cognitive Dissonance,” American Economic Review 72, no. 3 (1982): 307–319.

44. Joel Cooper, Russell H. Fazio, and Frederick Rhodewalt, “Dissonance and Humor: Evidence for the Undifferentiated Nature of Dissonance Arousal,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 36 (1978): 280–285; Joel Cooper, Mark P. Zanna, and Peter A. Taves, “Arousal as a Necessary Condition for Attitude Change Following Induced Compliance,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 36 (1978): 1101–1106.

45. Petty and Cacioppo, Attitudes and Persuasion.

46. Philip Brickman, Dan Coates, and Ronnie Janoff-Bulman, “Lottery Winners and Accident Victims: Is Happiness Relative?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 36 (1978): 917–927; Muzafer Sherif and Carl I. Hovland, Social Judgment: Assimilation and Contrast Effects in Communication and Attitude Change (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1961).

47. Eagly and Chaiken, Psychology of Attitudes, 368; Muzafer Sherif and Carolyn W. Sherif, “Attitude as the Individual’s Own Categories: The Social Judgment-Involvement Approach to Attitude and Attitude Change,” in Carolyn W. Sherif and Muzafer Sherif, eds., Attitude, Ego-Involvement, and Change (New York: Wiley, 1967), 130.

48. Daniel Katz, “The Functional Approach to the Study of Attitudes,” Public Opinion Quarterly 24 (1960): 163–204.

49. Ibid., 170.

50. Ibid., 175.

51. Herbert C. Kelman, “Compliance, Identification and Internalization: Three Processes of Attitude Change,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 2 (1958): 51–60.

52. Rajdeep Grewal, Raj Mehta, and Frank R. Kardes, “The Timing of Repeat Purchases of Consumer Durable Goods: The Role of Functional Bases of Consumer Attitudes,” Journal of Marketing Research 41 (2004): 101–115.

53. M. Brewster Smith, Jerome S. Bruner, and Robert W. White, Opinions and Personality (New York: Wiley, 1956).

54. Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (New York: Anchor Books, 1959); Robert M. Arkin, “Self-Presentation Styles,” in James T. Tedeschi, ed., Impression Management Theory and Social Psychological Theory (London: Academic Press, 1981), 311–333.

55. James T. Tedeschi, Barry R. Schlenker, and Thomas V. Bonoma, “Cognitive Dissonance: Private Ratiocination or Public Spectacle,” American Psychologist 26 (1971): 685–695.

56. Barry R. Schlenker, Impression Management: The Self-Concept, Social Identity, and Interpersonal Relations (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole, 1980), 204.

57. V. M. Desai, “Does Disclosure Matter? Integrating Organizational Learning and Impression Management Theories to Examine the Impact of Public Disclosure Following Failures,” Strategic Organization 12, no. 2 (2014): 85–108.

58. A classic expression of skepticism is Allan W. Wicker, “Attitudes versus Actions: The Relationship of Verbal and Overt Behavioral Responses to Attitude Objects,” Journal of Social Issues 25, no. 4 (1969): 41–79.

59. Herbert C. Kelman, “Attitudes Are Alive and Well and Gainfully Employed in the Sphere of Action,” American Psychologist 29 (1974): 312.

60. See Shirley S. Ho and Douglas M. McLeod, “Social-psychological Influences on Opinion Expression in Face-to-Face and Computer-Mediated Communication,” Communication Research 35, no. 2 (2008): 190–207.