6

KILLING TODAY: ECOCIDE

THE FLESH OF YOUR MOTHER STICKS BETWEEN MY TEETH

Environmental historians have a special fondness for remote islands. If, because of distance or limited nautical skills, their exchange with other societies is close to zero, external factors have a close to zero influence on their development and decline. The island is like a laboratory, in which this or that event (not infrequently a disaster) happens under controlled conditions.

Easter Island, 3,500 kilometres off the nearest land mass, South America, is therefore a kind of promised land for environmental historians. It was probably settled around ad 900 by Polynesians, who were masters in navigation and the construction of seaworthy boats, and it then experienced half a millennium of rising prosperity. According to Jared Diamond, the ecological conditions were not as optimal as on other islands settled by Polynesians, but they were sufficient to feed a large population of 20,000 to 30,000 divided into eleven or twelve clans, each with its own chief.

Of twenty-one species of plant that have since disappeared from the island, the tallest, which could grow as high as 30 metres, was especially suitable for large canoes.1 There were twenty-five species of land birds. The inhabitants lived not only on what they grew in the fields, but also on birds, dolphins and the numerous descendants of the rats that the original settlers had evidently brought along with them.

The golden age of Easter Island society must have been around the year 1500, when the number of buildings reached its peak before declining by 70 per cent through the seventeenth and into the eighteenth century.2 Easter was a theocracy; the chiefs, who had a quasi-divine status, exercised the office of high priest and, as in other Polynesian societies, mediated between the gods and men and regulated relations among the clans, chiefs and individuals.3 Earlier in its history the island may be said to have had the qualities of a medium-grade paradise, but by the time that the first Europeans arrived in the eighteenth century it offered an almost surreal picture. Easter was completely treeless and almost depopulated: the few inhabitants were, as Captain Cook reported in 1774, ‘small, lean, timid and miserable’.4 The only animals were rats and chickens. The landscape made an especially bizarre impression, since hundreds of (mostly broken) stone statues lay around. Many reached a length of 6 metres and a weight of 10 tonnes, but the largest of all was 21 metres long and weighed 270 tonnes.

A heap of half-finished or transport-ready statues was found in a quarry. The puzzle was how the inhabitants had managed to move and raise these giant sculptures, given that the island seemed to have no timber that could have been used to build the necessary wooden platforms and accessories. Today it is assumed that the figures were shown off by chiefs and clans to make an impact on others, and that at some point rivalry began over who could display the largest and most powerful. Historical dating techniques have shown that the average size of the statues grew over the centuries.5

Archaeological reconstructions make it likely that the islanders – partly because of the feverish production of statues – subjected their ecological resources to fatal predation. Deforestation seems to have begun soon after the first settlers arrived around ad 900 and was complete by the seventeenth century at the latest. We cannot know what went through the head of the man who felled the last tree; he probably gave it little thought and treated it as a simple necessity of life. When timber had still been plentiful, it had been used for burning and cooking, the extraction of charcoal and the building of houses and canoes, and not least as ancillary material for the deployment of the stone statues.

In sum, Diamond writes, ‘the picture for Easter is the most extreme example of forest destruction in the Pacific, and among the most extreme in the world…. Immediate consequences for the islanders were losses of raw materials, losses of wild-caught food, and decreased crop yields…. Lack of large timber and rope brought an end to the transport and erection of statues, and also to the construction of seagoing canoes.’6 There is no way of compensating for such a resource collapse on an island cut off from the outside world; fishing became ever more problematic as the canoes fell into disrepair, while soil erosion on the deforested, wind-swept land made agriculture less and less of a possibility. Without wood there was no longer any fuel, and in winter the inhabitants burned the last plants and grass. Decline spelled change even for the dead, since there was no wood for cremations and corpses were either mummified or buried in the ground.

Evidently this shrinking of the means of survival must have intensified resource competition in relation to food, building material, tools and symbolic representation. If decisive proof were needed that man does not live from bread alone (especially where he has none), 7 the Easter islanders certainly provide it with their persistence in a cultural practice to the point of risking their own survival. But they are not alone in this: standards of shame in the West can induce people to perish in a blazing house because they think it impossible to run naked into the street.8 Norbert Elias has several times described how excessive emotional involvement can block the detached view of a situation necessary for self-preservation.9

In the early seventeenth century, King Philip III of Spain ‘died of a fever he contracted from sitting too long near a hot brazier, helplessly overheating himself because the functionary whose duty it was to remove the brazier, when summoned, could not be found.’10 As we saw in the previous chapter, people’s decisions depend on how they perceive and interpret their situation. But it is also clear that there can be self-destructive decisions, even if, as in the case of Philip III, better solutions seem readily available. The fact is that cultural, social, emotional and symbolic factors often play a greater role than the survival instinct: one need look no further than suicide bombings to find a parallel in the contemporary world.

Philip III, like the Easter islanders, used a frame of reference that made it impossible for him to see what lay in store. It was as if the available cultural grids prevented things from being perceived in a different way, as if those involved literally could not see what else they might do. Such fatal blocks may also be produced through training and discipline. For example, in the hard-drilled armies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the order of battle meant that infantrymen had to stand and be killed: ‘Men stood silent and inert in rows to be slaughtered, often for hours at a time; at Borodino the infantrymen of Ostermann-Tolstoi’s corps are reported to have stood under point-blank artillery fire for two hours, “during which the only movement was the stirring in the lines caused by falling bodies”.’11

In other words, the perceived problem in all these cases was not at all the danger to one’s own survival but the risk of breaching symbolic or traditional codes of conduct linked to status or the obeying of orders. That risk may evidently be so great that no other option is visible. People then become prisoners of their own survival techniques.

Further striking evidence of this is provided by strategies that lasted far beyond their useful life yet continued to bind the energies and imagination of people alive at the time. For example, generations of master builders and military contractors went on constructing fortresses long after technology and forms of warfare had made them obsolete. The ever greater and more destructive power of cannons forced them to extend the external fortifications, until in a city like Antwerp these stretched for 9 miles around the central citadel. The absurdity of this constant outreach was that the actual cities to be defended ran out of space – indeed, they were constricted by their own defensive installations. Nor were there ever enough soldiers to man the fortress, and those stationed inside it cut themselves off from the enemy and were of no use if he decided to attack a position of greater interest. The building of new citadels when they were already known to be pointless was thus a case of ploughing on with formulas and procedures that had been successful under different historical circumstances.12

Another aspect overlooked in relation to the power of the forces involved is the decision either to threaten or to employ violence. Heinrich Popitz vividly illustrated this by means of the following example. On a cruise ship there are a third as many deckchairs as there are passengers. This is enough to go round, because at any one time sufficient people are occupied with something else. But the picture suddenly changes when new passengers come on board with techniques for hogging a deckchair even when they are not using it. The most effective of these is social cooperation: you ask another user to ‘keep’ your chair until you want to use it again. This has an advantage for the other user, because it is a favour that can be asked for in return.

Gradually a group that is privileged and a (perhaps numerically superior) group that is underprivileged take shape. The former can use the organizational advantage of cooperation for a common interest, in the face of which the other passengers are isolated individuals who would also like to have a deckchair but lack the power to assert their interest. This other interest does not yield an organizational advantage, especially as the disentitled have no cooperative model that might prevail over that of the entitled.

Power arises here out of a simple organizational advantage. This can even be extended at random to a third category – for example, by creating a third category of ‘guards’, who, in return for keeping order at certain times, are permitted to use a deckchair even though they do not belong to the category of those entitled to one. The fascinating aspect of this example is that the underprivileged group do not see that their inferior power is the result of an organizational advantage that the others have exploited, and from which new power can be generated. What they see is that they cannot have a deckchair, and although they may feel angry their very emotion blinds them to the real causes of their inferiority.13

Let us return here to the Easter islanders, who can tell us a lot about the importance of problem perception for the decisions that people make. Their case also shows that perceived problems can turn into very real ones and violently push for a solution. At the end of the Easter Island culture there was a terrible war. The resource conflict, due essentially to deforestation of the island, eventually led the inhabitants to become predators towards one another, as we know from the discovery of human bones with teeth marks (made to extract the marrow). This cannibalistic endgame has not only been proved archaeologically; it also features prominently in the oral heritage. Ecological degradation led to erosion not only of the soil but also of human culture.

Around 1680 the chiefs and high priests were overthrown by military men; the eleven or twelve clans decided to band together into larger fighting groups,14 and many inhabitants retreated to the protection of caves and tunnels. No more statues were erected, and those belonging to rivals were toppled and destroyed; stone slabs that had served as platforms were now used to protect cave entrances. As a further defensive measure, one group dug a deep trench that created a kind of peninsula, while a further technological advance saw the introduction of deadlier obsidian spearheads. In short, the island sank into a state of surreal destructiveness, which no longer offered a chance of survival to the great majority. John Keegan, military historian that he is, paints the picture of an absolute war that spelled the end first of politics, then of culture, and finally of human life.15

The island experiment, which was subject to no external influences, ended when the inhabitants used up their last resource: themselves. Of the few left after the war, the majority were bought up by Peruvian slave traders in the eighteenth century.16 In 1872 the island had no more than 112 inhabitants. The greatest insult that could be hurled at someone in Easter Island was: ‘The flesh of your mother is stuck between my teeth.’

GENOCIDE IN RWANDA

Now let us go back to Rwanda. The genocide there could take place with such dizzying speed because the many were killing the few (Hutus made up 90 per cent of the population). But, this being so, what accounts for the seemingly bizarre feeling among the Hutu that they had to defend themselves at all costs against the Tutsi? Why this sense of a deadly threat that had to be tackled, come what may?

The first part of an answer, as we have seen, is that first the German and then the French colonial authorities had considered the Tutsi to be a racially superior group and placed them accordingly. This better material and psychological position survived the colonial period and continued to have its effects after the country gained independence in 1962. The second part is that the history of conflict after 1962 had been long and bloody. Before the genocide began in April 1994, Rwanda had been the scene of a civil war in which Tutsi rebels had fought to wrest power from a Hutu-dominated government. With the assassination of the Hutu president, Juvénal Habyarimana, the previously rather blurred ethnic conflict acquired deadly sharp contours.

A civil war is a situation of chronic insecurity and extreme danger for the population of a country, and individuals can do no more than try to mitigate the real and perceived threats and do all they can to stay alive. The key issues, then, are orientation, transparency and a lessening of fear and confusion. These too require a clear identification of friend and enemy, of ‘us’ and ‘them’. Tutsi is what the enemy is, and the enemy is anyone who is Tutsi. It is even necessary to kill Hutus who try to protect or hide Tutsis, or who speak out publicly against mass killing. This is the self-referential system that forms the backdrop to the violence.

CROWDING

But the festering civil war was only one part of it. At the time, Rwanda was the country with the highest population density in Africa and one of the highest anywhere in the world; there had been rapid demographic growth, much as there is today in many parts of Africa, despite the disastrous living conditions. Such a situation, especially amid civil war and a general outbreak of violence, is likely to increase the propensity of individuals to act violently. Take, for example, the closely studied Kanama commune in north-west Rwanda, where between 1988 and 1993 the population per square mile shot up from 1,740 to 2,040, the average household size grew from 4.9 to 5.3 persons, and all (!) young men under twenty-five lived in their parents’ home. It has been calculated that, on small farms in the area, one person lived off only one-fifth of an acre in 1988 and as little as one-seventh of an acre in 1993.17 Most members of a family could not survive only on the produce of its farm but had to seek additional income from unskilled jobs, brickmaking, and so on. The percentage living below starvation level (1,600 calories per day) rose sharply, and with it the potential and gravity of conflict.

Even such critical demographic-ecological trends are interpreted with various grids. Thus, in Rwanda the conflicts and massacres of the years preceding the true genocide had already formed ethnically coded images of ‘us’ and ‘them’ groups, which guided people’s actions when mass violence broke out in the aftermath of Habyarimana’s assassination. Ecological, demographic and geographical factors tend to be played down, or simply categorized under ‘ideology’, in studies of violence and genocide, but in reality the perception of problems and their causes plays a decisive role for the active participants.

The perception of problems and possible solutions also has something to do with how the world is thought about more generally. It may be that murder is not actually defined as murder but regarded and understood as (in the case of the Holocaust) ‘special treatment’, ‘fulfilling a law of nature’ or a ‘final solution to the Jewish problem’ or (in the case of Stalinism) ‘the dying out of classes’ in accordance with the laws of history. The common interpretation of these as verbal smokescreens is a false trail. The Nazis really did consider the Jews to be vermin on the body of the Volk – which is why they killed them with Zyklon B, a poison used for pest control. In Rwanda people cut down other people as if they were ‘harmful weeds’ – which added special meaning to the act of killing by machete blows.18 (It also suggested to the outside world that the genocide was not a planned operation but a spontaneous outbreak of violence, as if the violence had originated with individuals and the weapons had been lying around in their houses.) Metaphors generally played an egregious role in the Rwandan genocide; the very weapons of murder were known in everyday language as ‘work tools’ (ibikoresho).19

Killing as work, mass murder as a kind of agricultural task akin to weeding or pest control: this is also the background to the commonest insult used for Tutsis, ‘cockroaches’.

The ethnically pure Rwanda of the Hutu imagination would be a ‘field’, the Hutus themselves ‘children of farmers’, their task to keep the ‘field’ in good order. ‘They killed like people go to the fields, going home when they get tired.’20 This is the deadly logic that justifies the total eradication of the Tutsi: ‘In “clearing the bush”, care had to be taken not only to cut the “high grass”, that is, the adults, but also to tear up the “young shoots”, that is, the children and young people. In fact, the extreme cruelty towards the unborn, babies and children was beyond all imagination.’21

There should be no mistaking the importance of metaphor for how people behave. Much of what outwardly looks like rationalizing imagery may be a self-evident reality, a tangible fact, for those whom it points towards a certain course of action.22 The same is true of the extreme paternalist view of politics expressed in the two interview extracts at the beginning of chapter 4. If I regard a president as my ‘father’, his assassination triggers a different motivational dynamic from the one that arises if I see him as a replaceable member of a functional elite.

Such things need to be understood by anyone who wishes to reconstruct what people see as their problems and how they aim to solve them. The perception of killing as a defensive action is an important element of self-justification for the perpetrators of genocide.

In Rwanda, the ‘accusation in a mirror’ technique23 also played a central role: that is, a genocidal fantasy was attributed to the other side, spreading the belief that it was bent on the total annihilation of one’s own side. Nor was this by any means only a social-psychological phenomenon; it was explicitly recommended as a propaganda technique, whereby ‘the party which is using terror will accuse the enemy of using terror’.24

The intended consequence was that Hutus in whom the sense of threat was instilled would be prepared to defend themselves, and would see any kind of homicidal attack or systematic murder on their part as a necessary means to that end. A further twist in the spiral came when stories were spread around that Tutsis were actually carrying out murders and massacres – that is, that the stage-settings of a terrifying fantasy world were becoming a reality. All these were well-known devices for the production of a dynamic of escalation, tried and tested most recently in Yugoslavia’s terminal wars and the Kosovo conflict.

The social proximity of the two groups, before mass killing separated them in practice, was a potential source of the violence, not an obstacle to it. In the imagined deadly threat of the Tutsi ‘them’ to the Hutu ‘us’, it was extremely important that mobility had been blurring the line between the two groups. One function of the murderous violence was to restructure reality by making the boundary crystal-clear.

WHAT DID THE KILLERS SEE?

There were five elements to the killers’ perception of society that could make the killing appear meaningful to them. First, there was a high degree of fear and insecurity, and therefore a great need for orientation, that could be addressed through violence. Second, a perception of ever more restricted prospects in work and life led to a considerably greater potential for increased violence. Third, there was a perceived threat of being annihilated if one did not take ‘defensive’ action against the imagined killers on the other side. Fourth, killing was defined as ‘work’ that needed to be carried out, within a more general vision of the society and nation as a ‘field’ that made the task of ‘cultivation’ seem absolutely useful. Fifth, the killers could assure themselves of the normality and meaningfulness of their action by thinking that everyone else did what they were doing.

Outwardly the genocidal violence seemed to be a primitive, spontaneous eruption, but from the inside it felt amazingly controlled and purposive. Underlying it was not only a history of murder and violence in civil war, with the associated fear and disorientation, but also ecological-demographic problems that made the situation of young men in particular seem more and more constricted and hopeless. This was a key element raising the individual propensity to violence.

The Rwandan genocide was not the result of a climate war, but nor was it due only to political and social-historical factors. Jared Diamond considers that high population density was at least one determinant, and it may well be that this is one of those cases where a problem that plays (or appears to play) no role in our own lifeworld has escaped our notice in a different context. In fact, it is not so long ago that the fantasy of being a ‘people without living space’ gave rise to a completely new geopolitical orientation in Germany, which made a war of annihilation and conquest seem a desirable and feasible way of opening up space for new German settlements in the East. It would be wrong to think that the underlying perception then was merely ‘ideological’: Nazi and other ideologies played a flanking role, but the real purpose was to gain new spatial resources, raw materials and slave workers.

The planned conquest of space in the East was different in kind from the problem that the Hutu thought they faced in Rwanda. But the point is that ideologies and ‘big pictures’ are subordinate to more down-to-earth matters in human perceptions, interpretations and decisions. Just as an early mastermind of annihilation might have had his eye on a dazzling academic career, or an SS Obersturmbannführer on a nice property on the Polish lakes, so might a young Hutu from Kanama have glimpsed the prospect of escaping his cooped-up life in the parental home if he fell in with the government’s plan to massacre the Tutsi. Such focused considerations may be much more significant than ‘racial fanaticism’, ‘ethnic cleansing’ or ‘ethnocide’ for the perpetrators of violence. Let us therefore now look at another genocide, which took place ten years after the one in Rwanda – just the other day, in fact.

DARFUR – THE FIRST CLIMATE WAR

First aircraft would come over a village, as if smelling the target, and then return to release their bombs. The raids were carried out by Russian-built four-engine Antonov An-12s, which are not bombers but transports. They have no bomb bays or aiming mechanisms, and the ‘bombs’ they dropped were old oil drums stuffed with a mixture of explosives and metallic debris. These were rolled on the floor of the transport and dropped out of the rear ramp which was kept open during the flight. The result was primitive free-falling cluster bombs, which were completely useless from a military point of view since they could not be aimed but had a deadly efficiency against fixed civilian targets. As any combatant with a minimum of training could easily duck them, they were terror weapons aimed solely at civilians. After the Antonovs had finished their grisly job, combat helicopters and/or MiG fighter-bombers would come, machine-gunning and firing rockets at targets such as a school or a warehouse which might still be standing. Utter destruction was clearly programmed.25

The air raids were not the end of the story. The violence then began in earnest. Janjaweed militiamen, riding horses or camels or driving Toyota Landcruisers, would surround the village, then move in to plunder it, rape the women, burn the houses down and kill any remaining inhabitants.26

This was the opening act, in July 2003, to the genocide in Darfur, in western Sudan. What was first reported to Western TV viewers as a tribal conflict between ‘Arab horseback militias’ and ‘African farmers’ looks, on closer examination, to have been a war by a government on its own population, in which climate change played a decisive role. Ethnically speaking, Darfur is an intricate web of ‘Arab’ and ‘African’ tribes, where ‘Arab’ is usually associated with nomadic lifestyles and ‘African’ with settled farming. A further complexity is the distinction between ‘native Arabs’ and those who first entered the country in the nineteenth century, mainly as Islamic preachers and traders. This core group of a quasi-colonial foreign elite, as Gérard Prunier puts it, was supplemented by slave and ivory dealers, who put themselves on the same level as the native Arabs. Although they had come from outside as conquerors, they eventually merged with the indigenous group, but to this day retain an elite position in Darfur society.27

The Janjaweed, infamous for their brutality, first appeared in the late 1980s at various trouble spots, in a role ‘halfway between being bandits and government thugs’.28 They are recruited from former highwaymen, demobilized soldiers, young men from mostly ‘smaller Arab tribes having a running land conflict with a neighbouring “African” group’, common criminals and young unemployed. These people receive money for their work: ‘$79 a month for a man on foot and $117 if he ha[s] a horse or a camel’. ‘Officers – i.e. those who could read or who were tribal amir – could get as much as $233.’29 Their weapons are provided to them.

As in Rwanda ten years earlier, then, these were by no means men who killed spontaneously out of hatred or revenge, but rather ‘organized, politicized and militarized groups’.30 At the time of writing, between 200,000 and 500,000 inhabitants of Darfur have died as a result of their work. There had been massacres in the earlier period too, but at least since 1984, when a disastrous famine hit the country, the history of violence has been closely bound up with ecological problems.

There have been conflicts for seventy years or more between Darfur’s settled farmers (‘Africans’) and nomadic herdsmen (‘Arabs’),31 but they have become increasingly severe as a result of soil erosion and greater livestock numbers.32 Elements of modernization and judicial dispute resolution, which were introduced in more peaceful times thirty or so years ago, swept away traditional strategies for problem-solving or reconciliation without establishing new or functioning forms of regulation.33 Instead, during the last thirty years, there has been a tendency for weapons to be used straightaway even in small local conflicts.34

In the disastrous drought of 1984, the sedentary farmers tried to protect their meagre harvests by blocking access to their fields by ‘Arabs’ whose pastureland had dried up. As a result, the nomads were unable to use their traditional marahil, or herding routes and feeding places. ‘In their eagerness to push towards the still wet south, they started to fight their way through the blocked off marahil. Farmers carrying out their age-old practices of burning unwanted wild grass were attacked because what for them were bad weeds had become the last fodder for the desperate nomads’ depleted flocks.’35

Here we see quite clearly that climate-induced changes were the starting point for the conflict. The lack of rainfall – in many parts of Darfur it declined by more than a third for a whole decade – meant that the northern regions were no longer suitable for livestock and that the herdsmen had to tear up their roots there and move south as full nomads.36 Furthermore, the drought produced large numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs), who were accommodated in newly built camps; as many as 80,000 starving people were on the move trying to reach one. The government’s first reaction was to declare them all ‘Chadian refugees’ and to order their deportation en masse, in an operation known as ‘Operation Glorious Return’.37

At the same time, a dramatic rise in population figures, averaging 2.6 per cent a year, led to overuse of pasture and other land and added to the anyway high potential for conflict. Whereas disputes over land and water had traditionally been settled at conciliation meetings chaired by a third party with government support, a different policy came into operation after General Al-Bashir’s military putsch in 1989. Now gov-ernment-backed militias increasingly intervened, making the conflicts sharper and more likely to end in violence.

Today’s conflicts are between government troops or militias and the twenty rebel organizations, so that an overview is as impossible for the participants as it is for outside observers. The largest rebel group – the Darfur Liberation Front (DLF), formed in February 2003 – initially campaigned for the independence of Darfur, but soon decided to go for a country-wide solution and renamed itself the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/SLA). In addition there is now a Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), which also seeks to weaken the government in Khartoum.38

The war in Darfur began when SLA guerrillas attacked the airport at El Fasher, and the government retaliated with the raids on villages described earlier. Nomadic Arab tribesmen then used these as an opportunity to appropriate farmland and animals. ‘As the clashes intensified, the government in Khartoum dismissed the governors of northern and western Darfur, who had come out in favour of a negotiated solution.’39 Government aircraft continued to bomb villages indiscriminately and deployed the Janjaweed to fight against the rebels. These have since engaged in a genocide interrupted only by periodic attempts to achieve a ceasefire. Violence has become a permanent feature of the situation. Neither the rebels nor the government are capable of a decisive victory, and nothing suggests that the opposing sides are genuinely interested in peace. Moreover, not only the Janjaweed but also the regular army and rebel troops have been inflicting violence on civilians.40

The high toll of the brutal fighting in Darfur has all the characteristics of a climate war; it also represents a new type of simmering warfare to be found in African societies in fragile or broken states. In chapter 7, ‘Killing Tomorrow’, we shall return to the point that one of the main differences between the civil wars of today or tomorrow and classical interstate wars is that the parties have no interest in ending the conflict and many political and financial interests in keeping it alive.41 Violence markets and violence economies have come into being – non-state areas in which business is done with weapons, raw materials, hostages, international aid, and so on. Obviously, no trader in violence is keen to see his business come to an end; he will therefore regard any attempt to restore peace as an unwelcome disturbance.42

A study published in June 2007 by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) summed up the situation as follows. In Darfur environmental problems, combined with excessive population growth, have created the framework for violent conflicts along ethnic lines – between ‘Africans’ and ‘Arabs’. So, conflicts that have ecological causes are perceived as ethnic conflicts, including by the protagonists themselves. The social decline is triggered by ecological collapse, but this is not seen by most of the actors. What they do see are armed attacks, robberies and deadly violence – hence the hostility of ‘them’ to ‘us’.

The UNEP soberly noted that lasting peace will not be possible in Sudan so long as environmental and living conditions remain as they are today. But those conditions are now marked by shortages that pose a threat to survival (because of drought, desertification, deficient rainfall), and which are further exacerbated by global warming. The road from ecological problems to social conflicts is not one way.

ECOLOGY OF WAR

‘Deploying technologies that make our forces more efficient also reduces greenhouse gas emissions.’ This bald statement comes amid the final recommendations of the report National Security and the Threat of Climate Change, which was written by a number of high-ranking American officers and published by the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA).43 It may seem surprising that such senior military men should not only warn of the increased security risk due to climate change but also call for more ecological methods of waging war. Yet they do not limit themselves, as in an EU report published in 2008,44 to water and soil conflicts, violence associated with migration and wars over raw materials; they further outline the implications of global warming for military technology and strategy.

Bad experiences of sandstorms in Iraq, for example, give reason to suppose that military equipment may malfunction in the hot dry conditions of many future theatres of war. The CNA report complains that frequent extreme weather events such as storms and hurricanes limit naval operations and use up equipment at a faster rate, already making it necessary in the hurricane season to station aircraft inland and to move ships away from harbour.45 It also makes the historical point that extreme weather has not infrequently affected the fortunes of war: the examples range from the typhoons that twice saved Japan from Mongol invasion through to the Scud missiles that Saddam could not fire at Israel because of the stormy conditions.

Logistical problems occur especially when troops rely on oilfired generators and have to wait for an endless convoy of tankers; energy-saving devices may thus lead not only to lower greenhouse gas emissions but also to increased battle readiness.46 Finally, rising sea levels pose a threat to many US military bases: the Diego Garcia atoll, for example, which has a major logistical function for operations in the Indian Ocean, will disappear, and so too will the Kwajalein atoll in the South Pacific and Guam in the West Pacific. The need to abandon such important positions will set up a vicious circle of rising transport costs and increased fuel expenditure.47 All these dangers, the report concludes, make it essential that the impact of climate change is systematically built into national security and defence planning.

It is doubtful that such collateral damage has already been factored into calculations of the economic costs of global warming48 – indeed, the whole subject still awaits scientific analysis. Since the causes of violent conflict within and between countries will not diminish, greater empirical and theoretical efforts will need to be invested in the development of an ecology of war.

Neither in civil wars nor in international conflicts do the contending sides pay much heed to environmental concerns. In Afghanistan, for example, the endless warfare of recent decades means that

eighty per cent of the country has been subject to soil erosion; fertility has declined, salinization increased and groundwater levels fallen dramatically, while desertification has spread over large areas and wind and water erosion is widespread. According to Abdul Rahman Hotaky, chairman of the Afghan Organization for Human Rights and Environmental Protection (AOHREP), other factors alongside war and war-related expulsions are the increasing length of droughts, improper use of natural resources, weak central government and the lack of an environmental policy.49

Seventy per cent of forest has disappeared, and nothing has been grown for the last two decades on 50 per cent of agricultural land.

In the Vietnam War, defoliants exposed 3.3 million hectares of land and forest to toxic chemicals; ‘the result was immediate and lasting damage to the soil, nutrient balances, irrigation systems, plant and animal life, and probably also the climate.’50 More than thirty years later the forests have not returned. In 1995 the World Bank concluded that Vietnam’s biodiversity has been permanently altered.51 Moreover, ecosystems have been rendered more unstable and soil erosion has become more intense.

Apart from these direct consequences of resource destruction, including groundwater contamination by oil and other materials of war and the conversion of whole regions into ‘no go areas’ littered with landmines, the secondary ecological impact has also been devastating. In the outskirts of Khartoum alone, the uncontrolled settlement of nearly 2 million refugees has led to the mushrooming of slums that lack clean water, drainage systems or any other infrastructure; the situation is no different in other towns in Sudan. Areas up to 10 kilometres around the refugee camps have turned into wasteland as people have cut down every last tree for firewood, and of course this affects the future too, since fuel for cooking and burning is one of life’s necessities. The Janjaweed raiders not only burn down whole villages but usually also fell or torch nearby trees to prevent the return of any refugees who remain alive.

FAILING SOCIETIES52

But rapid desertification anyway means that most refugees will never again live in their place of birth, since the soil there is no longer good for anything. Between 1971 and 2001, two-thirds of forest in northern, central and eastern Sudan disappeared; a third had been lost in Darfur by 1976, and 40 per cent is now gone in southern Sudan. The UNEP predicts a total loss of forest in some regions within the next ten years. The dramatic decline in rainfall has already turned millions of hectares of land into desert. A temperature rise of 0.5 to 1.5 degrees Celsius, which is highly likely to happen, would cut rainfall by a further 5 per cent and make the cultivation of cereals even more difficult. In the El Obeid region, for example, yields will fall from roughly half a tonne to 150 kilograms per hectare.53 At the time of writing, approximately 30 per cent of Sudan’s land surface is desert, but another 25 per cent will become so in the years ahead.

Not much imagination is required to visualize what it would mean for a Central European country to lose a quarter of its farmland, even though its economy would be much less dependent on agriculture and it would have many ways of coping with the shortfall through more intensive farming, increased imports, higher-yield plant strains, and so on. In an agrarian society like Sudan, however, with far fewer resources for survival, a change in environmental conditions is felt not as a constraint but as a disaster that directly threatens the lives of individuals and their families. There is no room for manoeuvre if the daily food supply falls below the level that the body needs to maintain itself. Neither psychological nor sociological knowledge is required to understand that violence is an option in such situations, especially where it is already prevalent in the surrounding society. Every square kilometre of new desert may then be a direct or indirect source of violence, since it limits people’s space for survival whether they realize it or not.

Because of their disastrous political and economic structure, countries like Sudan have no means to compensate for harvest failure or loss of land; they therefore repeatedly depend upon international relief operations, with all the implications that this has for corruption, the economics of violence and the perpetuation of refugee camps (see the next chapter).

Since fragile or failing states like Sudan are considerably more vulnerable to environmental risks, and have fewer means to cope with them, a natural disaster such as a flood affects them much more severely than it does a region like eastern Germany or central England, and climate change hits them much harder than it does Mediterranean regions, where desertification is also rapidly advancing. The European Union makes provision for payments to badly affected agricultural regions, whereas there is no question of compensation to people enduring desertification in Sudan. Their responses to their situation – over-farming of the remaining land, chopping down of the last trees, and so on – which are driven by sheer necessity, mean that the ecological problems will grow worse in the future. Political structures that do not curb violence, resting neither on the rule of law nor on the promotion of social welfare, serve to sharpen and perpetuate the problems rather than to mitigate them. As the example of Darfur shows, conflicts sparked by ecological factors are then seen as opportunities to play off one group against another, to stir up tensions along ethnic lines, and to keep them alive for as long as possible.

In large parts of Sudan, war has been the normal state of things for much of post-colonial history; the total number of deaths it has caused is estimated at 2 to 3 million, not counting the genocide in Darfur. Average life expectancy in southern Sudan is forty-two years, the literacy rate is 24 per cent, and the mortality rate for children under five is 25 per cent. That is how things look in a country where war, with a few breaks, has been the rule for more than forty years.

Unfortunately, Sudan is not the only country whose future will become still bleaker as a result of climate change. The ‘Failed State Index’ for 2006, which lists sixty states threatened with failure, includes Sudan right at the top. It is based on a number of indicators, social (demographic pressure, refugee numbers, inter-ethnic conflicts, chronic migration), economic (sharp inequality, economic problems) and political (delegitimation of the state, deficient public services, human rights violations, criminal security apparatuses, elite rivalry, weight of foreign political actors). African societies are the most highly placed, but holiday paradises such as Sri Lanka (25th) and the Dominican Republic (48th) appear along with a number of South American countries.54

All told, 2 billion people today live in countries that count as insecure, failing or failed – which in effect means that their lives are in greater danger than they would be in other parts of the world. Societies listed in this index are highly vulnerable to further negative changes of a political, economic or ecological kind – apart from anything else because a further limitation of their scope for development will increase the risk of wars and violent conflicts.55 There is a clear correlation between poverty and military violence. The statistical probability of an outbreak of war in a country with a per capita income of $250 is 15 per cent, while for one with an income of $5,000 or more it is less than 1 per cent.56

Paradoxically, the prospects are even worse if the country has many resources such as diamonds, oil or precious woods. The ‘curse of raw materials’ makes it especially attractive to rapacious national and international entrepreneurs of violence. Moreover, as the case of Somalia shows, civil wars and the like create niches or strongholds for organized crime and international terrorists. We must bear in mind that these countries have often reached or crossed the critical threshold of ungovernability, and that they have neither administrative or economic buffer zones nor transnational connections that might ward off crises or soften their impact. Any environmental shock, be it drought, flood, storm or earthquake, may thus lead directly to a social disaster.

Vulnerable societies, particularly those that failed to build stable civil structures in the wake of colonialism and post-colonial wars, are more prone than others to violent conflict resulting from environmental changes – partly because the state does not have a monopoly of force, but private monopolists and oligopolists also engage in acts of violence.57 Another reason why the security situation in these countries is so serious is that poverty is at its greatest and the costs of violence at their lowest.58

Climate change, then, sharpens inequalities within and between countries – between core and periphery, and between developed and less developed regions. It will inevitably result in further migration and refugee flows. That this will lead per se to greater levels of violence cannot be proven in the current state of research, but environmentally determined migration (for example, where land and water run short or, in economic terms, demand outstrips supply) must certainly be regarded as a potential source of violence. In such cases, competition breaks out among those seeking to acquire the scarce resource, and when survival is at stake there is always violence in the air. In sum, the social and political consequences of climate change may be seen as cumulative risks and vulnerabilities for fragile societies, whose situation may grow even worse as a result.

Since the 1990s, resource conflicts within and between states have been a central focus of climate change research.59 Attempts have also been made to correlate various forms of ecological decline with certain social-economic consequences.60 For a long time, however, researchers have offered no unified approach to analysis of the social and political consequences of environmental change, and no considerations have been presented as to what all this really means for the theory of society and social development. Some local studies have, it is true, investigated how development possibilities have been affected by sudden and sometimes wholly unpredictable outbreaks of violence partly due to ecological changes,61 but up to now there has been a failure to collate and theorize the existing material. This is all the more regrettable since domino effects appear in these societies – for example, if a developing potential for innovation is disturbed by social disasters, and capacities for long-term adaptation and prevention in the face of climate change are further weakened.

It is becoming clear that path dependence may translate into greater risks and lasting blockages to social development. Roughly thirty countries threaten to collapse in the near future.62 In view of this, the continuing paucity of research into the links between ecology, violence and development is truly disconcerting.63 Patently it is false to assume that different national development paths simply mirror different levels in modernization processes; it may be that they do not correspond at all to classical images of advanced or backward development but reflect ‘something else’ that has found no place in conventional Western theories of society. This is also the case when – as in some Islamic countries – secularization or other elements of modernization are absent or are being reversed. Clearly the OECD countries are no longer the ‘blueprint’ for state-building; civilizing and de-civilizing processes may take place in quite different ways from those familiar until now.

STATE COLLAPSE

Fragile statehood means first of all that state institutions and organizations do not function adequately because of a lack of political will, a legitimacy deficit or financial shortfall. In extreme cases, a total collapse of state organs such as the army, police and civil service gives rise to lawlessness and obscure power relations.64 And if state infrastructure implodes, the danger arises that all other social structures will collapse in short order.65

Fragile societies often display weak national integration,66 consisting of a multiplicity of ethnic, cultural, religious, regional or political groups that compete with one another for resources, enter into conflict and form alliances. Modernization pointing towards an ethnically homogeneous nation-state has not taken place. Without a stable monopoly of force and the rule of law, the state can scarcely intervene to mediate and regulate conflicts, so that the action of police or militias may, as in Darfur, actually make these worse. Fragile societies also suffer from other problems: urbanization rates in poor countries are among the highest in the world, and refugee flows and internal migration have led to a huge build-up on the outskirts of cities.67 In Lagos, one of the world’s megacities, 3 million out of the 17 million inhabitants live literally amid the garbage, without fresh water, sewers, streets, electricity, police or medical care.

Some elements of uneven development are simply beyond people’s ability to cope. Global media carry fragments of culture and lifestyle into corners where, not many years ago, people did not even realize that they shared the planet with fully industrialized societies. Changed ways of life and new expectations thus clash abruptly with traditional norms; there are no periods of gradual adjustment. At the same time, selective modernization – for example, better medical provision, rising educational standards or new economic forms – creates acute legitimacy problems for politicians and traditional elites. The reduction of infant mortality triggers demographic explosions that lead to the overrepresentation of young people in the population – a phenomenon which contributed to the social disaster in Rwanda and also played a role in the Sudanese debacle.68

Fragile societies are therefore under pressure from many sides: traditional structures undergo erosion, without being replaced by well-functioning modern ones; there is no state monopoly of force but a plethora of competing, often private, players; the vulnerability to social, climatic or other natural changes is extremely high, and the ability to handle them extremely low. When things reach a certain point, the state no longer plays an active role but simply provides opportunity structures for political, entrepreneurial and military elites to impose their interests. At the most, it offers the population a paternalistic frame of reference, which, as in Rwanda, is highly suited to violent mobilizations.

The retreat of the state unleashes domino effects: social conflicts, whatever their origin, become ethnicized; power relations shift among clans and other ethnic groups; and violence increases both within and between groups.69 The collapse of state and society creates space for the brutal assertion of interests and a confusing spectrum of violence and its perpetrators. The organization, rituals and norms of conflict change quickly as the boundaries to violence break down;70 this may occur at all levels and eventually lead to genocide.

Once again the availability of violence as an option is clear. Local, splintered problems are matched by local, splintered forms of violence; where regulatory institutions are lacking (or have been destroyed), there is generally a dramatic rise in violent conflict.71 As it is not attractive to live under such conditions, many gamble their all on seeking an improvement – and any such prospects usually exist only in another country.

Political theorists since Hobbes have assumed that a permanent war of all against all is the norm in the absence of the state, but this is not accurate in the case of societies such as Somalia or Sudan. What characterizes them, rather, are repeated flare-ups of selective violence against particular social groups. War and violence are indeed normal conditions there, but this does not mean that everyone is equally affected. Although theory does not provide for them, there are constellations of fragile statehood with a high degree of violence that may last for an unpredictably long time.

VIOLENCE AND CLIMATE CHANGE

The above examples show that, at least initially, the consequences of climate change are not so much wars between states or threats to their territorial sovereignty as shortages of drinking water, declining food production, increased health risks and land degradation and floods that reduce living space.72 Violent conflicts and climate change are thus linked in a series of stages and only exceptionally present a direct cause– effect relationship. This is why for a long time most researchers have overlooked or denied the connection between the two. Environmental changes due to global warming are treated simply as one variable in the interplay of factors that lead to violent conflicts. But this is trivial in so far as neither individual nor collective violence is ever monocausal, and it is even questionable in principle whether the origin and development of violent processes could be given such an explanation. The very category of ‘climate refugee’, so hazy in international law, makes it clear that the decision to flee may result from war, massacre, extreme weather, rising sea levels or loss of a subsistence base; several of these typically come together when people decide to seek salvation elsewhere. Nothing that brings human beings to make a far-reaching decision can be traced back to a single cause.

The main reason why social processes do not operate in accordance with a mechanical causality is that people act within specific social situations and relationships. The various influences impact not causally but relationally on decisions to flee or remain, fight or collaborate, and so on: that is, they change the position of the agent within a reality that is itself changing. Moreover, every decision produces new consequences, which may unintentionally or unexpectedly change the action situation. ‘If I had known that …’, people say when they are faced with unintended consequences of their actions, thereby making it clear both that they had other alternatives and that things could have worked out differently. New problems arise and need to be solved in the course of action – problems that no one reckoned with at the starting point in the chain of decisions and actions. Hence the chain of causes that historians construct has a far greater necessity than the relevant sequence of actions could have had at the time, and hence too it is never the case that the people who acted at the time could see all the consequences of their actions. For, unlike the historian, they never know how things are going to work out. The origin and development of social processes can never be attributed to a single cause, and they never unfold in accordance with causal laws. It is therefore a banality to say that climate change is not a direct cause of armed conflicts.

‘Climate change’, write Gleditsch and Nordas,

will probably have many serious effects, particularly transition effects, on peoples and societies worldwide. The hardships of climate change are particularly likely to add to the burden of poverty and human insecurity of already vulnerable societies and weak governments. Thus, climate change can be seen as a security issue in a broad sense, and efforts to halt or reverse it may well warrant a peace prize. However, so far there is little or any solid evidence that we are going to see an increase in armed conflicts as a result of climate change.73

One cannot agree with this in the case of Darfur or other African countries, especially as more recent research has identified correlations between temperature rises and violent conflicts and suggested that civil wars south of the Sahara will be 60 per cent more frequent by the year 2030.74 A study of climate effects on the development of conflicts in the Middle East also comes to disturbing conclusions.75 It may be, then, that there is evidence of greater potential violence in the wake of rising temperatures, declining rainfall or lower harvest yields,76 and there may be cases in which the disappearance of resources has led not to violence but to migration or contractual solutions.77 But all this shows is that environmental changes due to global warming produce new sources of violence, with which people cope as best they can.

It is ridiculous to claim, however, as Nils Peter Gleditsch does repeatedly, that one can speak of an increased potential for violence only when enough case studies have been published in specialist academic journals. For violence is never monocausal: it always arises in specific social constellations and historical situations, and years spent compiling hundreds of case studies will never establish a direct and straightforward connection between climate change and violence, in the sense familiar from the natural sciences. This is true of any other social fact, moreover. What is lacking is a theoretical framework that makes it possible to describe, or even better predict, factors leading to social breakdown and converting a latent potential into a direct application of violence. Only such a framework can allow one to assess what is specific and what is generalizable in individual case studies; otherwise one just piles up studies and is unable to see the wood for the trees – a practice that Margaret Mead, in her discipline of anthropology, called ‘Bongo-Bongoism’: ‘Yes, it may be that hunger often leads to violence, but among the Bongo-Bongos I studied things are more complicated …’

In any event – and this is largely agreed among social scientists – we can say that the consequences of climate change will reinforce and deepen survival problems and the potential for violence; they will interact with political, economic, ethnic and other social-historical factors and may also lead to the open use of force.78 The pioneering work of a research team under Günther Bächler has established that ‘violent actions are not attributable to drought, flooding or sea levels per se, but rather to the weakness of political institutions, the unsustainability of social-economic structures or the dissolution of traditional conditions of life.’79

At present, the main climate triggers of conflict are food or water shortages and social breakdown following extreme weather events or mass migration.80 In general, climate-driven environmental changes make survival difficult where failed states and barren conditions leave little scope for compensatory adjustment. Whether hunger, thirst, land loss, expulsion, ethnic conflict or warlord rivalry over power and resources then lead to open violence depends on the exact local balance between existential threats and compensatory opportunities. The danger of conflicts is never smaller as a result of climate change; and here too there are intensification effects, such as the special difficulty of adjusting to climate change where the state is fragile or has failed.81 This means that, at a later stage, the resources for a functioning state in the affected regions will be further weakened by advancing climate change82 – a vicious circle that the asymmetry of global society will make more frequent in the years and decades to come. But here a few more remarks are in order about the already discernible links between environmental stress and the potential for violence.

Ecological problems such as soil degradation and resource shortages have been widely discussed at national and international level since the publication of Limits to Growth83 and the emergence of the ecological movement in the 1970s. All the more striking is it, then, that the social implications have received so little attention up to now. Only discussion of the water wars of the early 1990s, and of the ever growing numbers of refugees on the coasts of Tenerife, Gibraltar, Andalusia and Sicily, has given subtle hints that climate change may have a social and political side that goes beyond weather trends and snow cover in ski resorts.

Recently, eco-social linkages have been seen in the conflicts between nomads and farmers in Nigeria, Ethiopia and Kenya, and in the genocides in Rwanda and Darfur. Although violent conflicts are always a product of several parallel, uneven developments,84 the structural causes of violence, such as state collapse, the emergence of ‘violence markets’ and the exclusion or extermination of population groups, are reinforced and accelerated by ecological problems and the disappearance of soil, water and other resources. Salinization adds to the problems by reducing areas of farmland and triggering migration flows. It is then the search for new pastures or agricultural land, rather than ecological decline per se, which may directly unleash conflicts with other groups.85 The same applies to the border conflicts that will become more frequent as waterways that used to constitute natural frontiers run dry.86 Internal migration triggered by environmental changes also leads to major conflicts and may be understood as an indirect consequence of climate change. It is estimated that there are currently 24 million internal refugees around the world.

A further threat is the breakdown of protection systems. Alongside the increasing intensity and frequency of hurricanes, tsunamis and drought, rising sea levels are the main danger to development and survival in many parts of the world. The 15 to 59 centimetre rise predicted by the year 2100 will cause the flooding of parts of megacities, where the poor will be the hardest hit. In Lagos, for instance, which today has a population of 17 million, the consequences could destabilize the whole of West Africa; western coastal areas of the continent are themselves exposed to flooding, while further south Mozambique, Tanzania and Angola are in particular danger. Nor are these problems limited to Africa. The floods in New Orleans in 2005 put hundreds of thousands to flight and showed that, even in stable societies, infrastructure can be destroyed with lightning speed and relief organizations stretched to breaking point. The disaster also made it clear how quickly social order can break down.

The greater frequency of extreme weather events is already hitting poorer, more vulnerable groups in society, especially slum dwellers, who are the least able to protect themselves or to make the necessary adjustments. Natural disasters may destroy large chunks of existing infrastructure, sometimes on a recurrent basis, so that transport, supply and health systems are weakened and the state is further destabilized.

The spread of infectious diseases and food crises poses another set of problems. As we said before, development and conflict research has established a clear correlation between poverty and susceptibility to violence,87 but disease and malnutrition are further consequences of climate change. According to the IPCC, the expected temperature increases will cause infectious illnesses such as malaria and yellow fever to spread faster and to affect previously untouched regions such as East Africa.88 In southern Africa alone, the total infected areas are likely to double by 2100, when some 8 million people will be infected. Already the number of additional malaria cases due to climate change is thought to be running as high as 5 million, with 150,000 deaths.89

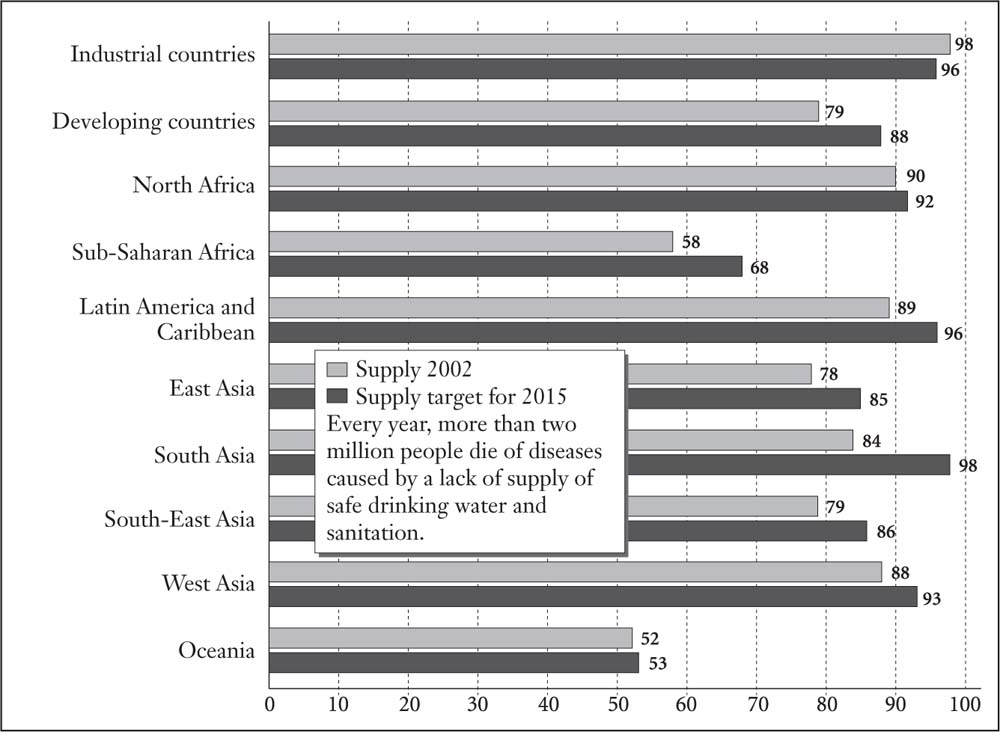

Figure 6.1 Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water, by region

Source: WHO/UNICEF 2004.

Water is, of course, a key factor in the whole issue of health. Sub-Saharan Africa has the worst water supply situation anywhere in the world today,90 and any improvement is made more difficult by the growing resource shortage.91 Up to now the greatest effect of climate change in Africa has been the decreased precipitation, especially in West Africa, and in future North Africa too will have to reckon with sharply downward trends. In the last thirty years rainfall in the Sahel region has declined by 25 per cent;92 we have already discussed the impact on other regions in Sudan. Soil degradation, water shortages and extreme weather events such as drought or floods are already having an effect on productivity, especially in arid and semi-arid regions; this trend will become more pronounced in the years ahead. With the predicted temperature rise of 2 degrees Celsius by 2050, 12 million people in Africa alone would face starvation; a rise of 3 degrees would push the total up to 60 million.93

Another future cause of conflict will be the drying up of rivers and lakes. A long-smouldering dispute between Iran and Afghanistan goes back to the closure by the Taliban in 1998 of the dam sluices on the Helmand River, which cut the flow of water into the Iranian Hamoun lake region. Soon afterwards all three lakes in the region dried up; the surrounding ‘marshes turned to dust bowls. Hundreds of villages on either side of the border were overwhelmed by shifting sand dunes and ravaged by summer dust storms…. The old irrigation channels round the lake disappeared beneath the sand.’94 There are many similar situations where countries lying upstream channel off so much river water that virtually nothing is left for those downstream – a classical instance being the River Jordan, which supplies very little water to the country after which it is named.95

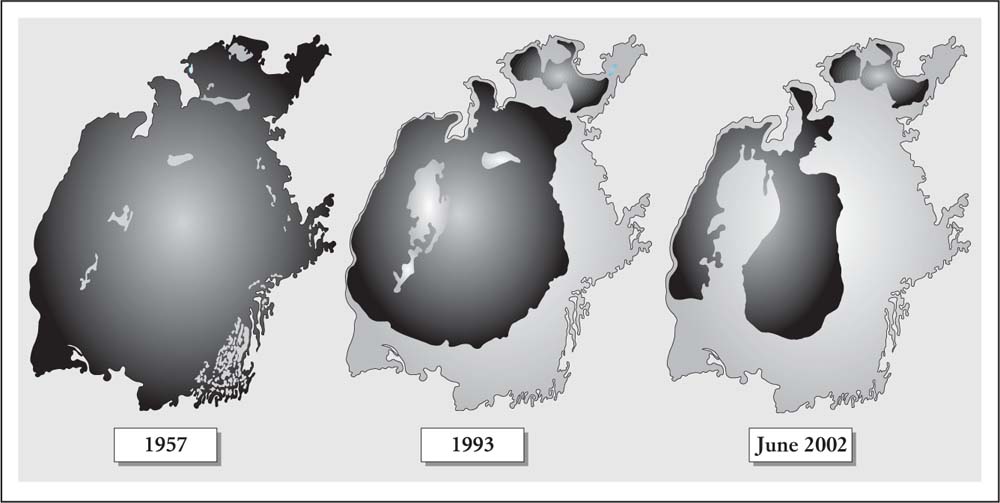

Even more spectacular is the disappearance of lakes that mark the boundary between states. Lake Chad, for instance, has by now lost 95 per cent of its original area, owing partly to decreased rainfall, partly to diversion for irrigation projects. Previously, four countries – Niger, Nigeria, Chad and Cameroon – lay on Lake Chad; today neither Niger nor Nigeria has any shores by it. Since people began to settle on the dried-out bed of the lake, border disputes have broken out between neighbouring countries – Nigeria and Cameroon, for example.96 Similar things have been happening on the Aral Sea, through which the Kazakhstan–Uzbekistan frontier runs.

Figure 6.2 The shrinking of the Aral Sea, 1957–2002; the sea became divided in two in 1989–90

Source: Philippe Rekacewicz, GRID/UNEP.

The social consequences of climate change give rise to the following conflict scenarios.

- – The number of violent local and regional conflicts over access to land and freshwater will increase.

- – Migration between countries will grow, together with the numbers of internal refugees, leading to violence at both local and regional level.

- – The shrinking of lakes and drying up of rivers, as well as the disappearance of forest and nature reserves, will generate cross-border resource conflicts.

- – One country’s adaptation to climate change (dam construction, water extraction from rivers and underground basins) will create problems in one or more other countries, again leading to interstate conflicts.

In addition, international trade disputes will increase in relation to such resources as diamonds, wood, oil and gas. Since violent conflicts tend to develop a dynamic of their own, further problems will arise that appear solvable only through the use of greater violence. The scale of the resulting refugee flows cannot be accurately predicted today – forecasts vary between 50 and 200 million so-called climate refugees by the year 2050, in comparison with current Red Cross estimates of 25 million.97 Social processes cannot, however, be simply projected from existing situations, since it is not possible to predict how countries will react to immigration pressure or how great the conflicts will be that trigger further refugee flows. For example, the war in Iraq alone resulted in 2 million Iraqi exiles abroad (mainly in Syria and Jordan) and 1.8 million internal refugees.98 It has been calculated that there were already 25 million environmental refugees in 1995 – well above the figure for ‘normal’ refugees (22 million).99

This is another source of disquiet in many governments and international organizations. At the end of 2007, the United Nations Security Council held a debate for the first time on climate change and security, and in 2009 UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon was instructed by the General Assembly to produce a report on the issue. In March 2008 the European Union published a joint report by High Representative Javier Solana and the European Commission, under the title Climate Change and International Security, which Solana supplemented with further material in December 2008.100 All the findings concur that global warming will bring considerable security problems in the short, medium and long term, even though these will vary greatly from region to region.

In terms of climate as well as economics and security challenges, the Western countries may remain islands of bliss for another few decades in comparison with less favoured parts of the world. But they too will inevitably be drawn into climate wars – or, to be more precise, into the waging of climate wars. On the other hand, not all of these will look like what have traditionally been thought of as wars.

INJUSTICE AND UNEVENNESS

The consequences of climate change are unfairly distributed, because those who bear the largest responsibility for it are likely to suffer the least harm and to have the greatest opportunity to benefit. Conversely, those parts of the world which have scarcely yet added to the emissions that cause global warming will be the ones hardest hit. The industrial countries emit an annual average of 12.6 tonnes of CO2 per capita, while the poorest countries limit themselves to 0.9 tonnes. Nearly a half of all emissions worldwide come from the old heartlands, despite the rapid catching-up on the part of the newly industrializing countries.101

Monsoon irregularities will primarily affect the countries of SouthEast Asia. Floods will mainly hit people in the world’s major delta regions, such as those in Bangladesh and India, for example. The impact of rising sea levels will be worst on small island states (the countless Pacific islets, for example) or low-lying coastal cities like Mogadishu, Venice or New Orleans. Rich countries such as the Netherlands will find it fairly easy to improve their dyke defences; communities in Kansas will be able to afford reforestation after storm damage much more readily than those in Kerala.102

This relative injustice becomes absolute when whole populations lose their livelihood – for example, if island clusters like Tuvalu are flooded or the homelands of the Inuit disappear. The government of Tuvalu has applied for asylum in Australia and New Zealand on behalf of its population; the Inuit, supported by human rights organizations, want to sue the United States as the chief producer of greenhouse gases.

At present there is little prospect that international disparities will be confronted; international environmental law is still in its early stages, and individual countries are neither compelled to sign up to it nor bound by its provisions. There are no international courts of justice to punish violations of the principles of sustainable development or environmental protection. Binding measures against even higher emissions of greenhouse gases, for example, require the complex negotiation of treaties and agreements, but the main problem is that most of these only provide for signatory states to incur obligations on their own initiative, and that it is therefore difficult or impossible to sanction those which fail to meet their targets. Some countries, moreover – the USA and Australia, in the case of the Kyoto Protocol – tend not to endorse binding declarations that they think will be disadvantageous to them economically.

However distant it seems, the creation of an international environmental organization and court of justice is urgently needed103 – although the planet will probably be a couple of degrees warmer by the time they take shape.

The unjust distribution of the consequences of climate change, and of the capacity to cope with them, is not only further proof that life is unfair; it has also created considerable potential for conflict, as we can see from the complex human rights issue of how to compensate Pacific island or Arctic dwellers whose living space is already disappearing as a result of floods or global warming. Furthermore, the distribution of causes and effects is unjust in the relationship between generations, where the conflict potential is marked in a number of respects.

In the 1950s, the emissions curve generated by the industrial countries rose steeply; the cause of the problem, whose full scale is only now visible to us, is therefore at least half a century old. But the causes of climate change not only go back many decades but have persisted throughout the intervening period and become global as the developing countries have modernized in turn. A reversal is therefore hard to imagine, and for all the mutual promises it even seems utopian to believe that emissions will be held at their present level.

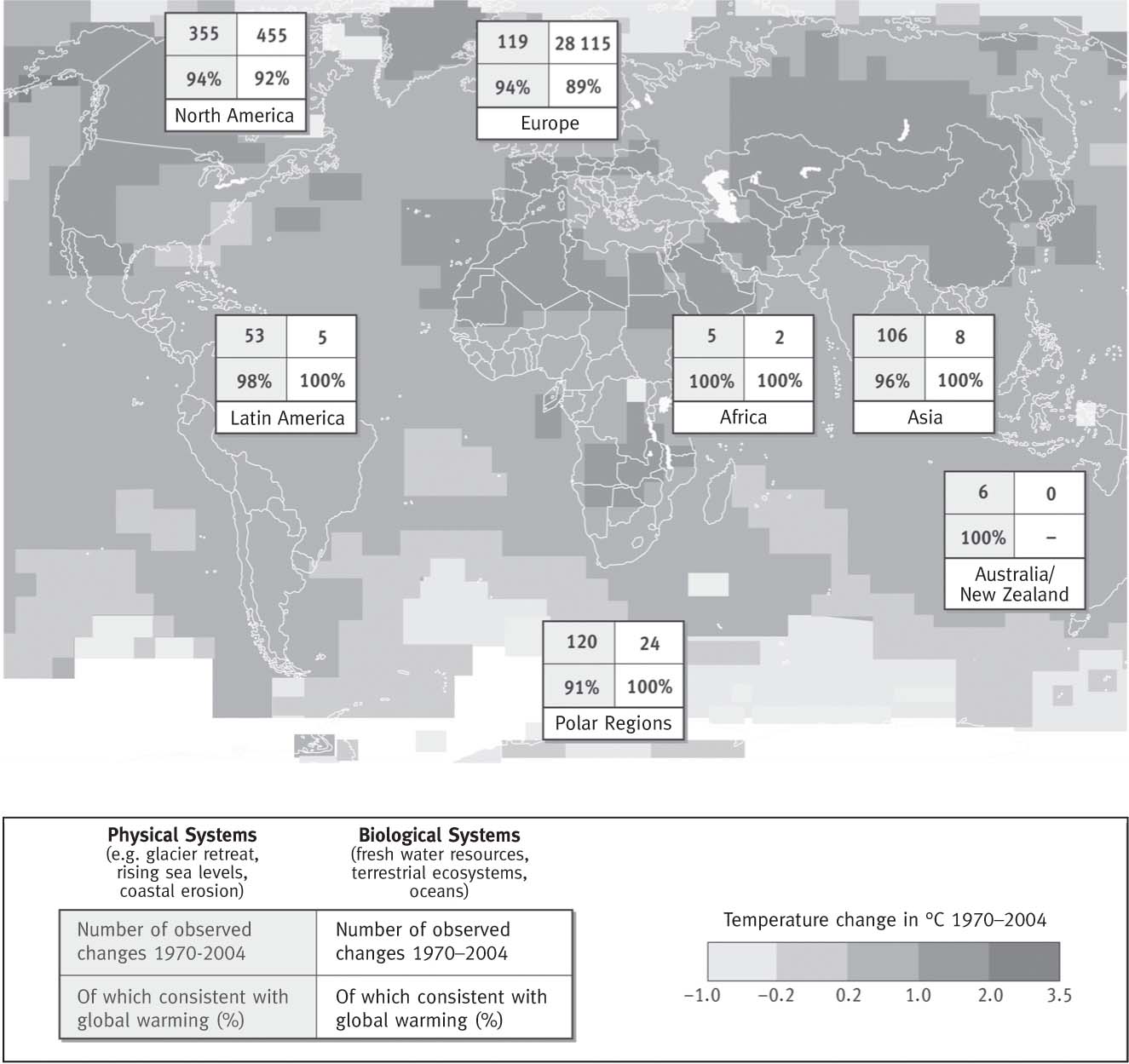

Figure 6.3 World map of climate effects

Source: IPCC.

In any case, there is the further problem that the climate is slow to respond. Present and future generations will unfortunately have to deal with a time lag of half a century, whose climate effects would show even if everyone stopped driving a car tomorrow, even if no more aircraft took to the skies, and even if all factories shut down forthwith. Such larger-than-life prospects hardly encourage anyone to do something to counter them.

The global, but very unevenly distributed, effects of climate change also raise considerable problems of justice in interstate relations.104 It is true that many international programmes are under way to strengthen adjustment capacity – for instance, those coming under the IPCC or the Global Environment Facility (GEF) – but there is reason to doubt their effectiveness. It is certainly frustrating that today’s and tomorrow’s generations will have to cope with what their predecessors leave behind, especially since, although the effects are already palpable, plans to improve matters remain highly vague.

The measures devised and applied today will yield results, if at all, only in a distant future, while in the meantime the reshaping of life-worlds keeps running in the background. Since the consequences of what is done will stretch over generations, it may well be asked whether there is any scope at all for people living today to produce outcomes from which they themselves will benefit.

Yet another complication is that, although some effects of climate change are already discernible, the new significance of extreme heatwaves, storms or downpours may be fully intelligible only in a scientific framework. No one today says: ‘The weather’s gone crazy’, but rather: ‘It’s global warming at work.’ Yet knowledge of this comes from scientific research and models; those who lose their livelihood from the melting of Arctic ice and can see for themselves what is happening are few in number, and their special lifeworld is wholly unlike that of Mediterranean peoples, for example. For the moment their experience may still even seem exotic.

Other people, however, can perceive the impending catastrophe only by means of models, and psychologically these arouse little motivation to change personal behaviour or to prioritize activities and interests in a new way. This is true even in prosperous, well-educated Western societies, which can afford the luxury of looking at environmental problems in a time span longer than a quarter of a century. But the unevenness of development and especially the moves by non-Western societies to catch up radically undermine the urgent development of environmental awareness and problem-solving strategies.

Arguments based on justice that involve tolerance or acceptance of catching-up modernization play an ambiguous role in this respect. We cannot, it is said, deny to third world societies the kind of technological and economic modernization that the West has to thank for its own locational advantages, high standard of living and relative security for the future. This raises the question of whether justice requires creating the possibility for others to eliminate the foundations for long-term human survival. But the real point here is that questions and arguments centred on justice weigh heavily in discussions of climate change and will become even more explosive in the future; it is already evident that those who profit from a further increase in deadly emissions are already playing the justice card to push through their anachronistic conception of modernization, whereas those who have no chances in their place of birth claim it is just that they should at least be able to live somewhere, even if it is not where they would like to live.

To sum up: the industrial modernization processes in full swing in Asia today, which, as we see from the Chinese case, are not subject to democratic control, give no indication of how they might incorporate a more rational approach to resource conservation and survival interests, or of how the trap of ‘catching-up justice’ might be dismantled. In fact, the phenomena of injustice and unevenness have considerable significance for social and democratic theory and raise a set of key questions. What does transgenerational injustice imply for the possibility of conceiving oneself as a political subject? Or for the sense that one can achieve something through one’s actions? Or for the range of ideas about how something might be changed? What does politics mean in such circumstances, beyond the mere processing of external constraints?

VIOLENCE AND THEORY