Clinical Photographs

“Feeblemindedness” in Eugenics Texts

MARTIN ELKS

This chapter is based on an extensive study of photographs that appeared in eugenicists’ writings in the period from 1900 to 1930 (Elks 1992). The sources cited show that some pictures come from texts published in Great Britain. Eugenicists abroad shared both US eugenicists’ perspectives and their clinical texts. The sources in this chapter do not include annual reports and other forms of institutional propaganda like those noted in chapter 5 on asylums. A more complete analysis and discussion of the research reviewed in this chapter can be found in Elks 1992.

The eugenics era, a period covering approximately the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first three decades of the twentieth century, was a time when many medical and other professionals focused their attention on describing, explaining, photographing, and controlling classes of people they thought were responsible for most social problems. One such group of major concern encompassed those people labeled “feebleminded.”11 Roughly speaking, feeblemindedness was the general term used in the United States to describe conditions later referred to as “mental deficiency,” “mental retardation,” “intellectual disabilities,” and “developmental disabilities.”22 In the eugenics era, it was widely believed that feeblemindedness was one of the root causes of crime, pauperism, dependency, alcoholism, prostitution, and other social ills.33

Eugenics was “the science of the improvement of the human race by better breeding” (Davenport 1911, 1). Eugenicists believed that the major cause of intellectual disability was biological—heredity as well as inbreeding and disease, so they considered the best solution to the problem was to control who bred. They believed that feeblemindedness unchecked would reproduce so prolifically that society as a whole would degenerate. They advocated such practices as regulating the marriage of “undesirables,” strict immigration laws that would keep mentally deficient people out of the country, confinement of the feebleminded in institutions, and sterilization. Even euthanasia was suggested as a possible remedy (Hollander 1989; Elks 1993).

Many of these ideas were widely held not only by professionals, but by the general public. By 1914, eugenics was taught at major universities such as Harvard, Columbia, Cornell, and Brown (Chorover 1979). Exhibits extolling eugenics principles were common at state fairs, where families would be examined and trophies given to the “fittest families” in order to promote positive eugenics. Numerous books, journals, and associations were devoted to the public dissemination of eugenics’ ideas and policies. Prominent eugenics associations that flourished included the Eugenics Education Society, the American Breeder’s Association, and the Race Betterment Foundation.

The destructive influence of the eugenics era on the lives of persons with intellectual disability then and now cannot be downplayed (see M. Haller 1963; Ludmerer 1972; Kevles 1985; Ferguson 1994; Carlson 2001). And photography played an important role in promoting eugenics ideas and policies. The photos in this chapter appeared in eugenics texts and articles written by experts in mental deficiency and represent the embodiment of their beliefs about the cause and clinical dimensions of feeblemindedness. I refer to these images as “clinical photographs” in that they were produced by clinicians to describe various aspects of the clinical condition they referred to as “feeblemindedness.”

Armed with theories of degeneracy, genetic inheritance, intellectual disability, and intelligence testing, eugenicists led the crusade to seek out the feebleminded in order to control them and their reproduction (Davies 1930). Disability professionals took on the mandate of studying them as well as popularizing theories about the dangers of feeblemindedness. Photography was one of their most important tools (Fernald 1912, 91–97).44

THE CAMERA IN THE HANDS OF EUGENICISTS

During the eugenics era, it was widely believed that a person’s physical features, the shape of his or her body, and facial appearance revealed basic information about his or her moral character and mental abilities. They believed that the trained eye could tell whether a person was feebleminded just by looking at that person.55 In addition, they believed that the environment in which the feebleminded lived, their homes and surrounding area, could be documented as proof of their degeneracy.

Early-twentieth-century technical advances in photography and the increasing ease with which photographic images could be reproduced in books and journals proved to be a boon to professionals in the field of mental deficiency; they helped to promote these professionals’ theories. Eugenicists trusted the camera to record the facts accurately and rapidly. Photography became a diagnostic tool, a method of developing classification systems, and a way of providing empirical proof of the link between the physical body and psychological disorders and deficiencies (Gilman 1982).

Eugenics textbooks that emphasized feeblemindedness followed the popularity of theories and writings of Italian criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso. Lombroso’s theories of the born criminal and the stigmata (bodily indicators) of criminals were widely accepted in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century (Reilly 1991). His classic text L’homme criminal (1876), published in English as Criminal Man in 1911 (Lombroso [1911] 2006), provided a format for textbooks on feeblemindedness. In addition to graphs and drawings, Lombroso freely used pictures derived from photographs to illustrate and prove his ideas.66

Most eugenics texts were extensively illustrated with photographs of people with mental disabilities. Like others, Martin Barr used many photographs in two influential texts, Mental Defectives (Barr 1904) and Types of Mental Defectives (Barr and Maloney 1920). Barr was one of the advocates of photography as a useful tool in eugenics and described the camera’s utility in detail. He encouraged students and professionals to study photographs carefully so that they could gain knowledge of the types of feeblemindedness and use that information to diagnose defective children and adults (Barr and Maloney 1920, 177).

The power of the belief in photography to achieve the goals of recognizing the feebleminded can be seen in the abundance of illustrations in the books and journals of this era. For example, Henry Goddard’s 1914 text Feeblemindedness: Its Causes and Consequences contains thirty-eight plates, each with multiple photographs. Martin Barr and A. B. Maloney’s Types of Mental Defectives (1920) contains thirty-one plates of up to nine photographs each, and Alfred Tredgold’s 1908 work A Textbook of Mental Deficiency (Amentia) has thirty-two such plates. Eugene Talbot’s text Degeneracy: Its Causes, Signs, and Results (1901) contains 120 illustrations, many of which are photographs. In the Journal of Heredity, the premier eugenics journal of the period, there was scarcely a page without a photograph or some other graphic image.

Eugenics textbook photographic illustrations can be sorted into three major categories. In the first group, the most numerous, were photographs of people who were supposedly feebleminded. The second included pictures of parts of their bodies—mainly ears, tongues, hands, and brains. The third offered social documentary views of feebleminded people living in what was described as their “natural habitat,” their homes and surrounding environments. I concentrate on the first two categories and only touch on social documentary toward the end of the chapter.

PORTRAITS

The vast majority of the photographs found in the texts are portraits of people who were allegedly feebleminded. The illustration at the start of this chapter (6.1), showing a person designated as a “cretinoid” in the caption, is a good example. Although most illustrations are of a single subject taken full body or from the waist up or of the shoulders and the head, group shots were also common. Rather than being photographed as individual persons, the subjects were depicted as specimens, examples of types of mental defectives, or carriers of particular diseases or conditions. Although their first names are sometimes given or their full name in rare instances, in the great majority of the captions their diagnosis is used as their designation—for example, “cretinoid” (cretin)—or they are referred to by such phrases as “case 3” and the “mongol type.” Clinical photographs of this era are the only genre of disability imagery where subjects are regularly shown nude or only partly clad (illus. 6.2).

The composition of the photos is straightforward and simple. As in the photos of criminals in Lombroso’s work and of “the types” of tribal peoples in physical anthropologists’ texts, the subject of a photo illustrating feeblemindedness was placed in the center of the frame, facing the camera or in full profile. As in illustration 6.3, it was common for textbook portraits to include the subject in two views, fully facing the camera and in profile.

In portraits taken indoors, there are no decorative backdrops. The backdrop is typically mono-colored—black, white, or gray—and it often looks as if a bed sheet were used. Although most of the portraits were taken indoors, many, especially those of higher-functioning institutionalized people and those of small groups, were taken outside with either buildings or trees in the background. Many of the outdoor shots have a snapshot quality—they are not formally posed, and the composition is not well organized—as if these pictures were taken by amateurs, albeit competent ones (the focus and the contrast are good). Although in some pictures the subjects are nude, they are most often dressed, some in normal and even dressy clothes, others in institutional garb. Instead of subjects being posed in the way most people might be in a normal picture-taking scenario, they were photographed to emphasize their abnormalities and their status as clinical subjects.

Illustration 6.4, a photograph of a man with microcephaly, is a prime example of posing a subject in order to emphasize his abnormalities. Subjects were often chosen to be featured in texts because they displayed some extreme physical characteristic that could be linked to feeblemindedness. In this illustration, the man’s head is exceptionally small and abnormally shaped even for someone classified as microcephalic. His head is also shaved, a feature of the picture that visually dramatizes the size of his head and contributes to his strange appearance. We do not know whether his hair was removed for purposes of the photo or not. Institutional staff usually shaved inmates’ heads to simplify maintenance and to control parasites.

Most clinical portraits were taken inside buildings or on the grounds of institutions or hospitals where subjects were either confined or under observation. As institutional officials began including mug shots of “patients” in their records and producing institutional visual propaganda, some of them established photographic studios on the premises. Institutions with research centers often had their own photographic facilities. Many of the photographs were likely taken by mental health professionals, some even by the authors of the studies where they were used as illustration. Others were taken by professional staff photographers. The photographs have a straightforward, clinical, utilitarian quality; the modes of presenting are repetitive to the point of being boring. No attention is paid to the aesthetics of the picture. In this regard, they are the opposite of art photography.

In addition to the general characteristics of eugenics photography just discussed, other special features define the genre, such as measurement of body parts, the presence of a “helping hand” in the photo, and documentation of brains and other body parts.

MEASUREMENT

Aside from the portrait genre of disability photographs, eugenic clinical photographs often show the subjects next to rulers, calipers, and other measuring devices. These devices’ obvious function is to show the reader the dimensions of the subject’s body, typically his or her overall size or the magnitude of his or her head. Although in some photos the measuring device’s practical function is obvious, in others, such as illustration 6.5, it is not. (Also see illustration 6.2, left side.) In this illustration, it is difficult to decipher what the ruler is measuring, and no information is provided in the text describing what the reader is to learn from viewing it.

In illustration 6.6, a boy is posed with a man holding a large caliper. The purpose of the instrument is made clear by the caption: “Making head measurements during a mental examination. The shape of the head is often important.”

These measuring devices not only gauged the physical characteristics of subjects but provided a symbol of the alleged science behind the study of feeblemindedness. After all, precise measurement is the trademark of science.

HELPING HAND

By “helping hand,” I mean that in addition to the person who is judged feebleminded in the photo, part of the body of a staff person, usually his or her hand, is visible. The helping hand is most often an attempt to guide or control the subject being photographed. The helping hand usually comes from an anonymous person who is outside the frame. Although it is present in many pictures, it is primarily associated with pictures of lower-functioning intellectually disabled persons, those who were called “idiots” and “imbeciles” (illus. 6.7). It is seldom present in portraits of “morons,” which was what higher-functioning persons with intellectual disabilities were called at the time.

The presence of the helping hand in the images varies from minimal—barely visible—to demonstrably intrusive. In a few examples, two people are present (illus. 6.8). The helping hand can be holding the subject in a standing position or manipulating him or her into a favorable pose or even keeping him or her from leaving the frame. The force of the contact of the helping hand varies from barely a touch to a strong grab.

What does the helping hand tell us about picture taking and the relationship between the photographer and the subject? For the most part, it is there because the person taking the picture could not rely on the subject to pose as desired. The helping hand tells us that the positioning of the body was largely involuntary and that the composition was largely in the picture taker’s hands.

Although the presence of the helping hand in some photos can be construed as a symbol of the subject’s rebellion—that the subject was resisting the photo opportunity—that interpretation is farfetched. In the great majority of the photos, the helping hand is an indicator of the subject’s dependency and is a powerful communicator of the feebleminded person’s incompetence (Fernald 1912).

BRAINS

Pictures of the diseased and deformed brain extracted from the sculls of dead feebleminded persons are in most eugenicists’ texts on so-called mental defectives. Some illustrations even include profiles of the subject alive juxtaposed with pictures of his or her postmortem brain. Photographs of the brain represent physical evidence of eugenicists’ belief that the most common cause of feeblemindedness was defective brains. In fact, with the exception of some severely disabled people, a viewer cannot really tell the difference between the brains of people labeled feebleminded and the brains of anyone in the general public. Nevertheless, some brains taken from some dead people diagnosed as feebleminded did exhibit abnormal patterns. These brains were featured in the texts. The inference was that it was only a matter of time before other brain anomalies in feebleminded people would be recognizable by scientists.

Pictures of brains concretized feeblemindedness—reified it as a physical, objective condition with clear visible causes. The captions of photographic illustrations of brains focused on their relative size, shape, convolutions, and special diseased-related abnormalities. Seeing is believing, and the more people saw pictures of abnormal brains, the more they believed that such brains were the source of mental deficiency (illus. 6.9).

Eugenicists thought that external parts of the body, in addition to brains, revealed feeblemindedness or mental deficiency as well. These abnormalities were called the “stigmata of degeneracy.” A typical list included “facial asymmetry, harelip, protruding or malformed ears, facial grimaces, strabismus or other eye difficulty, high, cleft, or missing palate, deformities of the nose, irregular impacted teeth,” as well as peculiarities in the shape of the head, malproportioning in general physique (such as unduly long arms or legs), gigantism or dwarfism, extreme awkwardness, and so on (Pressey and Pressey 1926, 40).

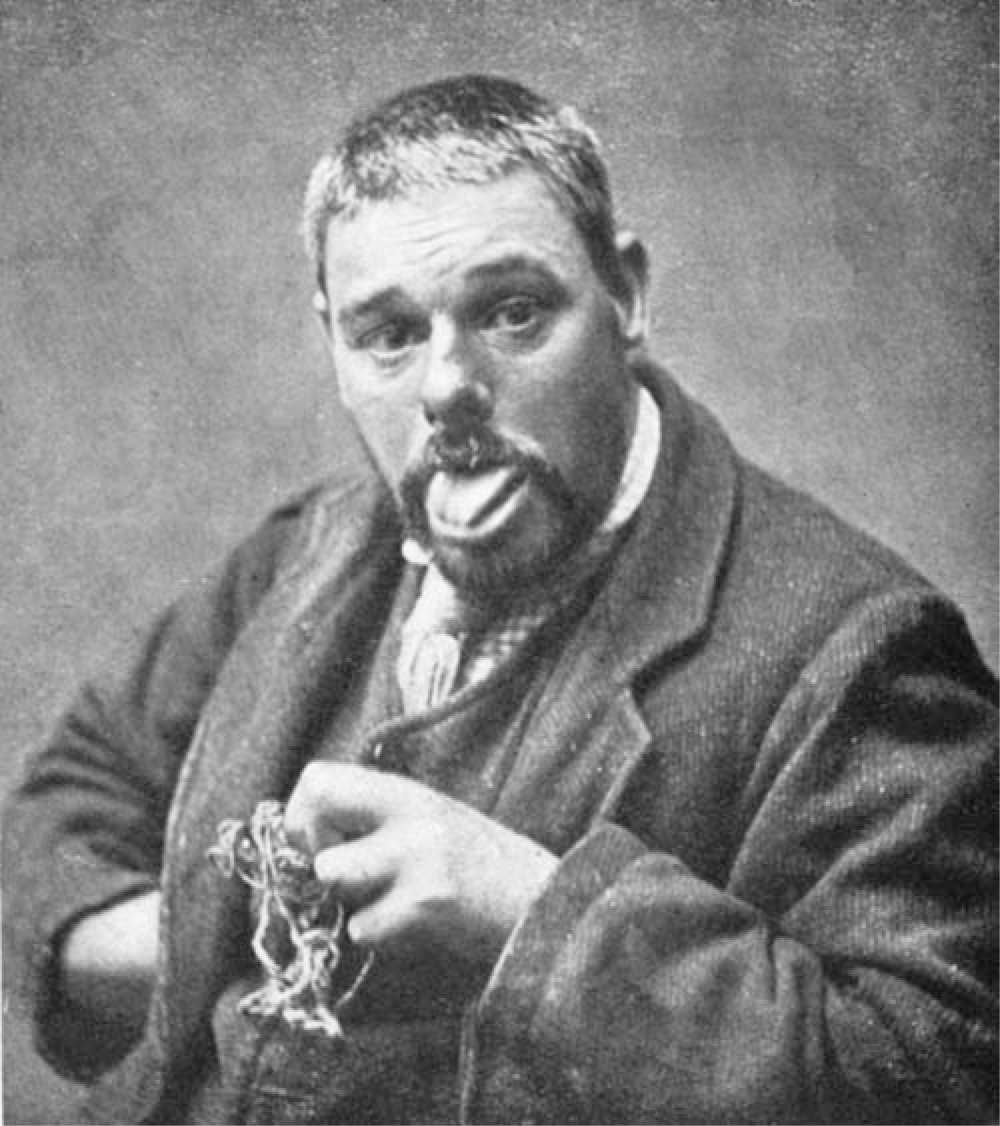

The list was endless, but certain body parts were singled out for documentation, photographed, and featured in texts. The mouth was one. Reference to the mouth may be found frequently in case descriptions of idiots and imbeciles.77 Alfred Tredgold described the mouth of the feebleminded person this way: “The lips are often thick, coarse, prominent, and unequal in size. The mouth is heavy and flabby-looking, generally open, and devoid of either refinement or firmness” (1908, 84). Photos showing close-ups of the mouth and captions making reference to the mouth’s position, shape, or size were common.

One type of mouth associated with feeblemindedness was what eugenicists called “the gape” (illus. 6.10). The term referred to a mouth that was open beyond that which was considered consistent with a normal relaxed mouth. The gape could be caused by an abnormally large tongue—common in syndromes referred to as “mongolism” and “cretinism”—or just be a characteristic of the way a person held his or her mouth.

6.10. “A mischievous, excitable imbecile; usually grimacing as shown.” From Tredgold 1916, plate VI.

Particular-shaped mouths and tongues were used in eugenics texts as the personification of feeblemindedness. When being photographed, subjects were posed so that their mouths or tongues were highlighted and thus so that the abnormality the picture takers wanted to illustrate was emphasized (illus. 6.11).

Ears were another body part given attention. Like brains, ears were examined for their shape, size, and various abnormalities. In addition, their position on the head was noted. Asymmetrical ears, where one ear was not the exact duplicate of the other, was a sign of mental deficiency, as were various irregular-shaped ears. Illustration 6.12 is from a page devoted to “ear anomalies” in Tredgold’s 1929 book Mental Retardation. The two pictures on the top are from the same person and show asymmetry. The ear on the lower left was described as “deformed and elongated,” whereas the one on the lower right was distinguished by having a “supernumerary auricle.”

The forlorn fellow in illustration 6.13 is labeled in the caption as possessing “constitutional inferiority.” The caption makes special mention of his “jug handle ears.”

Hands and arms were also frequently featured. The hand irregularities found in people with Down syndrome are commonly shown (illus. 6.14).

In addition to abnormalities in specific body parts, eugenicists believed a person’s body type and posture could reveal feeblemindedness. Thus, many textbooks had full-body illustrations of subjects in which they pointed out characteristic stances of particular categories of mental deficiency (illus. 6.15).

SHOWCASED SYNDROMES

Professionals documented and described specific major syndromes associated with feeblemindedness. These syndromes included microcephaly, “mongolism,” and “cretinism,” all of which were considered to have demonstrable physical manifestations.

Although the eugenicists’ views were reprehensible, their observations did lead them to occasional correct inferences. People who are classified as microcephalic have small craniums and other body abnormalities that make the condition obviously visible. In addition, the condition is clearly linked with intellectual disability and has a hereditary component. The eugenicists, however, carried these conclusions a large step further. For them, it was in many respects the paradigmatic case of feeblemindedness; it embodied all of their beliefs about mental deficiency.

Pictures of people with microcephaly abound in eugenics writings. Most are individual profile portraits, a pose that best showed the individuals’ small, unusually shaped skulls (see illus. 6.4). In addition, many photos show people with the condition juxtaposed with individuals with hydrocephaly, a condition in which there is an abnormal amount of fluid accumulation in the cavities of the brain. This fluid can cause pressure inside the skull, which brings on a progressive enlargement of the head and mental disability. Photographs that juxtapose an abnormally large head with an abnormally small head exaggerate the appearance of the abnormalities in both subjects—the small head looks even smaller, and the large head looks even larger. The juxtaposing of extremes in general, not just of people with unusually large or small heads, but of abnormally tall and abnormally short people, and so on, is used extensively in eugenics illustrations (illus. 6.16).

Another extensively displayed syndrome was what mental health professionals called “mongolism.” Today such people are diagnosed as having Down syndrome. Believing that people with this syndrome were genetic throwbacks to what were considered inferior races and that they resembled certain Asian peoples, Mongolians, eugenic scientists coined the name “mongolism.” Although the resemblance between people with Down syndrome and Mongolians was fanciful, texts juxtaposed pictures of people with the syndrome with pictures of Asian Mongols in an attempt to concretize the theory (illus. 6.17).

As I pointed out in earlier illustrations, people with Down syndrome, like those with microcephaly, have facial and body characteristics that are easy to recognize. People with the syndrome were photographed and included in texts at various ages from birth to old age. The large “mongol tongue” was a favorite photograph (illus. 6.18).

Aspects of Down syndrome shown in photographs also included forehead furrows, eyes, profile, posture, hands, ears, and feet. People with Down syndrome were regularly displayed in group photographs, too (illus. 6.19). Notice that the man in the center front is pulling at the mouth of the person to his left. Is he imitating a doctor who would pull the tongue down?

One easy way to exaggerate an abnormality, stigmata, or peculiarity was to multiply it by grouping people with the same deviancy together. The exaggeration was even further enhanced if they were wearing similar clothing. This approach can be seen in illustration 6.20, showing children with Down Syndrome and captioned “a group of Mongols.” Note the helping hand on the upper left.

“Mongols” were also juxtaposed with other categories presumably to document their similarities and differences and to add validity to “mongolism” as a distinct type. One such other category was “cretins” (see illus. 6.1 at the beginning of the chapter). Like “Mongols” and microcephalics, cretins—in reality, people with hypothyroidism—were photographed in ways that would emphasize the physiology of their condition. Cretins were more often photographed naked to show their underdeveloped bodies. For similar purposes, they were regularly photographed next to people of normal size (illus. 6.21).

CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

Eugenicists’ believed that inferior persons would affect later generations by passing undesirable traits to them. As they saw the situation, this detrimental cycle needed to be stopped.88 Thus, as part of their arsenal of intervention, they developed classification systems to sort out the various types and grades of feeblemindedness. Classification schemes provided experts with a guide they could use to implement their genetic-control policies—for instance, in determining who should be institutionalized or sterilized.

The search for a classification system that was comprehensive, definitive, and easy to use was of the utmost importance (Barr 1904, 78). Barr and Maloney’s widely adopted classification system laid out in Types of Mental Defectives (1920) listed five major types of mental deficiency: “idiot,” “idio-imbecile,” “imbecile,” “moral imbecile,” and “backward or mentally feeble.” In addition, each of these major categories had up to four subcategories, yielding a total of twelve classifications or “grades.” The scheme took into account physical and behavioral characteristics as well as intellectual functioning. It was widely endorsed by professionals, including doctors.99

Barr and Maloney’s text contains twelve plates of photographs corresponding to the twelve categories of feeblemindedness, each plate with up to eight photographs. For example, seven photographs on one page are labeled “Idiots: Profound Apathe [sic]” (illus. 6.22). On the next page are eight photographs of people labeled “Idiots: Superficial Excitable” (illus. 6.23).

To the eugenicists, “superficial excitable idiots” apparently looked different from “superficial apathetic idiots,” who in turn looked different from those considered representative of the other categories, such as “idio-imbeciles,” “middle-grade imbeciles” and so on. As the illustrations show, they do look different, but not because of any physical anomalies. The individuals pictured in the collection labeled “Idiots: Profound Apathe” appear to be younger, more often in chairs, and less dressed up than those in the collection “Idiots: Superficial Excitable.” In addition, the illustrations do not match the written descriptions of the characteristics. Nevertheless, the text, accompanied by the photographs, asserted that each type and grade had a characteristic appearance and that it was possible on the basis of inspection to recognize it.

Barr and Maloney claimed that by arranging the photographs side by side from the lowest grade, “idiots,” to the highest, “high-grade imbeciles,” it was possible to grasp visually the range of mental defect (Barr and Maloney 1920, 50). When the pictures are carefully examined next to one another, however, they do not accomplish this aim. The best indicators of the types of feeblemindedness in the photographs are not the physiological identifiers named in the classification system, but rather the format and composition of the photographs: the choice of subjects’ age, the presence or absence of the helping hand, how the subjects are dressed, their posture and facial expression. “High-grade imbeciles” could be identified because their portraits were often taken only from the waist up, the subjects are wearing stylish clothes, and the picture was taken in a studio (illus. 6.24). All these aspects of the photos could be manipulated by the photographer or by others involved in the picture taking.

Further, it is not clear from the images how “high-grade imbeciles” differ in appearance from people not diagnosed with a mental disability. If the individuals shown did not look feebleminded, as the eugenicists defined it, how did they illustrate “feeblemindedness”?

It would appear that the “ascending scale of mental defect” coincided with an ascending scale of socially valued characteristics. The bottom of the scale carried images of abnormality, disability, and dependence (e.g., plain clothing and helping hands), whereas the upper parts of the scale carried images of independence and achievement (studio portraits, stylish clothing, books, and jewelry). There was no neurological reason why studio portraits and good clothes should not have been as valid for “idiots” as for “high-grade imbeciles.”

In 1930, a leading eugenicist, Paul Popenoe, pointed out the wooliness of associating mental competence with appearance in an article based on a study he did focusing on photographs of boys of similar age and dress in similar poses and positioned in front of the same backgrounds and in the same settings (see Popenoe 1930). Some had been diagnosed as feebleminded, others as highly intelligent. Popenoe asked test participants to look at the photos and guess the boys’ intelligence quotients (illus. 6.25). Their judgments were inaccurate, no better than chance. Except for three or four photographs showing people of the very lowest intelligence, the participants could not predict intelligence by appearance in any reliable way. (See also Popenoe 1929.)

The inappropriate and inaccurate use of photographs by eugenicists as scientific proof is obvious when one reviews the thousands of pictures used as illustrations in eugenics texts. Some assertions about the photographs are just plain absurd. Many photographs were taken of conditions that are impossible to be captured in photos—for example, the picture of a person with “echolalia” in Barr and Maloney’s text (1920, 157) (illus. 6.26). Barr and Maloney defined echolalia as a “parrot-like repetition of words and sentences which may or may not be fully comprehended by the speaker” (157). Echolalia, however, has no visible photographic features. People do not look “echolalic.” The caption in the picture is the only element in the photo that would lead to the interpretation that the subject has echolalia. The belief in the validity of photography in general and of this specific photograph led the viewer to see in the photograph the condition identified in the caption.

Illustration 6.27, showing a so-called idiot savant, demonstrates this same issue. An idiot savant was defined as a person who was feebleminded but had an unusual skill. For example, he or she might be incompetent in basic life skills but be able to accurately add large numerals in his or her head. Other savants could tell the day of the week that any given date occurred on. Although there is no visible sign of this condition that can be photographed, the simple act of placing a caption labeling the person pictured as an idiot savant in a eugenics text made him or her “look” as if he or she were indeed an idiot savant.

Why include in eugenics texts so many illustrations of people who had no outward signs of feeblemindedness? As I have already suggested, eugenicists believed that feeblemindedness was a threat. Although they held that the cause of feeblemindedness was mainly biological, they worried that in many cases feeblemindedness was difficult for the untrained person to recognize. They wanted to warn the world that higher-functioning mental defectives, “morons,” were out there and dangerous. This picturing of people who did not look feebleminded alerted the general public to the unrecognizable danger that surrounded them.

THE HOVEL AND THE NOTORIOUS FEEBLEMINDED

Although illustrations in eugenics texts were mostly of feebleminded people taken in institutions and hospitals, some emphasized what was considered to be feebleminded persons’ “natural” environment. These photographs are found in case studies of families published by eugenicists.

In the case study of the Hickories, the caption of one photo (illus. 6.28) reads: “A HOME THAT SHOULD BE BROKEN UP: In this cabin live two of the Hickories (second cousins) and their two young children. Both husband and wife are decidedly feebleminded, and it is certain that all their children will be. It is sometimes a crime for society to break up a family: but it is unquestionably a crime for society not to break up this one, segregating the members for life” (Sessions 1917, 297).

The “natural habitat” of the feebleminded was most often labeled a “hovel.” Dilapidated and poorly constructed, maintained, and furnished, the hovel was substandard housing where, according to the eugenicists, people lived a disorganized and depraved lifestyle. The hovel became a symbol of those feebleminded people. In photographs, the housing conditions of “degenerate families” were portrayed as dismal: roofs sloping in the wrong direction, construction from scraps of building materials, holes in the roofs and sides, crumbling structures. Such housing was often located in rural settings, with animals either cohabiting with the family or housed nearby.

Feebleminded people who lived outside the boundaries of institutions were feared for what was considered their criminal and excessive reproductive tendencies. Pictures of hovels in eugenics literature went along with eugenicists’ interest in seeking out and documenting the heritage of feebleminded families who became notorious for their “debauchery.” Their real names usually did not appear in the texts, but such names as “Kallikak,” “Juke,” “Nam,” “Hickory,” and “Piney” became the stereotype of feebleminded families in their habitat.

Many photos include family members in front of their hovel. These illustrations shared some of the same qualities of the muckraking photos discussed in chapter 5 on asylum photography. Rather than being carefully posed and well focused, the photos are often blurry and off kilter, techniques that compounded the impression of disorganization yet gave the feeling of candid authenticity. They were produced to serve the same purpose as institutional muckraking images—to expose the people’s horrible living conditions. But here the location is not the institution, but the horror of community living. The irony here is that the institutional muckraking photographs were directed at the evils stemming from the practices that the eugenicists were promoting, but the eugenicists used the same photographic techniques as the muckrakers.

Illustrations 6.29 and 6.30 are taken from Henry Goddard’s famous study of a branch of the Kallikak family, a line that allegedly produced generations of decadent feebleminded relatives. Many years later biologist Steven J. Gould asserted that the Kallikak photos in these illustrations, which appeared in Goddard’s book The Kallikak Family (1912), were retouched to make the eyes and mouths look sinister (see Gould 1981). The director of photographic services at the Smithsonian, James H. Wallace Jr., agreed with Gould’s judgment that the eyes, eyebrows, mouth, nose, and hair in the photos had been retouched to give the impression of evilness. The assertion that Goddard was engaged in conscious skullduggery in his photographic touchups and that the modifications of the pictures cast the subjects as evil has nevertheless been debated (Francher 1987; Elks 2005). The details of the argument aside, whether a conscious intent in the zealous pursuit of eugenics ideology or an attempt to improve the pictures’ visual quality, the Kallikak photo modifications remind us to be skeptical about the claims eugenicists made about these photographic images.

The image of the hovel is one of poverty, squalor, and an animal-like, unhealthy, and disease-ridden lifestyle. It is a particularly powerful image because eugenicists believed that the feebleminded created their own environment. The hovel and the accompanying notorious family studies were the eugenics movement’s “central, conformational image: that of the degenerate hillbilly family, dwelling in filthy shacks and spawning endless generations of paupers, criminals, and imbeciles” (Rafter 1988, 2).

DEBORAH KALLIKAK

Eugenicists believed that a feebleminded person could be saved from a life of debauchery through training and careful supervision in segregated institutions. The threat that person posed could be minimized by locking up him or her. Like charity organizations focused on physical disabilities, eugenicists had their own version of before-and-after photography of the feebleminded that illustrated how custodial care could improve lives and save society. The institutional propaganda photos included in chapter 5 showed how orderly and productive the feebleminded could be behind institution walls.

A single person would occasionally be showcased as the “poster child” of what proper care and supervision could accomplish. Deborah Kallikak was one such person. H. T. Reeves called her “the World’s Best Known Moron” (1938, 199). Deborah was a member of the infamous Kallikak family that Goddard featured in his widely read book. The study on which the book was based falsely documented the feebleminded line of the Kallikak family tree for a purpose: to show how the progeny on the “bad side” of the kin were prostitutes, criminals, and prolific producers of their degenerate kind (Smith 1988). Illustration 6.31 is a portrait of Deborah that appeared in Goddard’s book. It was taken at the Vineland Training School for Feeble-Minded Boys and Girls in Vineland, New Jersey, where she was an inmate. She is pictured as an attractive, well-dressed young lady. Note the fine dress, the bow in her hair, and the book she is holding.

The juxtaposition of complimentary pictures of Deborah with the touched-up pictures of her relatives in front of their hovel was meant to illustrate how she had been saved by eugenicists’ intervention. The degenerate children on the porch (illus. 6.30) represented how she was before that intervention, and the young lady sitting in a refined manner (illus. 6.31) showed her as she was after it was accomplished.

Deborah was institutionalized at Vineland for eighty-one of her eighty-nine years, in spite of the fact that she demonstrated competence in a number of ways, including serving as the nanny for the children of institutional staff and housemaid for the institution’s director (Smith 1988, 29). Until his own death in 1957, Goddard continued to refer to her as feebleminded and as a potential threat to society if set free. She died in 1978 at the Vineland Training School.

CONCLUSION

Eugenicists were for the most part wrong about the correlation between appearance and feeblemindedness and in almost all other aspects of their doctrine (Gould 1981). Their ideas and classification systems are laughed at today. However, for the people labeled feebleminded, the eugenicists’ mistakes were costly. These mistakes fueled a bigoted ideology and its subsequent abuses (e.g., Black 2003). We can only imagine how many ordinary lives were disrupted and changed forever when individuals were labeled feebleminded.

The “objectivity” of clinical photographs was an illusion. Through photography, eugenicists created an imaginary disease, feeblemindedness (Smith 1988; Trent 1994). Their textbook and journal illustrations are better described, however, as rhetoric rather than science. Nevertheless, the belief in the truth of photographs helped to elevate eugenics to scientific social policy.

![]()

1. The terminology used in this chapter reflects the clinical vocabulary used during the period. The term feebleminded was spelled two ways, with or without a hyphen after feeble. For histories of mental retardation in the United States, see Ferguson 1994, Trent 1994, Noll and Trent 2004.

2. The term feeblemindedness was used inconsistently. Although most professionals used it the way I am using it, others used it to refer only to people who were “higher-functioning mental defectives.”

3. One eugenicist who was the leader in the field of intellectual disability, the psychologist Henry Goddard, showed his contempt for people with feeblemindedness when he stated: “The feebleminded person is not desirable, he is a social encumbrance, often a burden to himself. In short it were better both for him and for society had he never been born” (1914, 558; for another statement like this one, see Barr 1904, 102).

4. Intelligence testing—which was at a rudimentary state of development in the eugenics era—was also ranked high as a diagnostic tool. I have not included it in my discussion.

5. Earliest clinical textbooks described the links between mental disorders, on the one hand, and body types, facial features, and expressions, on the other (e.g., Morel 1857). Early pioneers in the field of mental disorders advocated the use of pictures, even photography, in identifying and diagnosing mental patients (Diamond [1856] 1976, 18–21).

6. For examples, see the format used in Tredgold’s 1908 text on mental deficiency and Goddard’s 1914 text on feeblemindedness.

7. Elizabeth Kite, Goddard’s fieldworker, made the following observation on one of her field trips: “Three children, scantily clad and with shoes that would barely hold together, stood about with drooping jaws and the unmistakable look of the feeble-minded” (quoted in Goddard 1914, 77).

8. The Eugenics Record Office outlined ten such dangerous “varieties of the human race” (Laughlin 1914, 16).

9. The system was first published by Martin Barr (1904), who was chief physician at the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children and an early president of the American Association on Mental Deficiency.