Pathways

Think of a pathway as a natural narrator. It tells the colorful story that draws people into your outdoor space. Sure, you can leave to chance the discovery of all the beauty and varied features of the backyard you’ve worked so hard to create. Or you can use a pathway to gently lead visitors to your annuals bed, prize roses, water feature, arroyo and bridge, garden bench, or gazebo.

The takeaway about the projects in this chapter—beyond that they generate immense gratification and a quick transformation of your outdoor area—is they are easy to pull off. They require negligible maintenance, make your yard look established and stately, and they protect your plants from those musing meanderers who might mangle your marigolds. While these pathways projects are not difficult, they do require a design and knowledge of materials, base drainage, and borders. All in all, it’s a fun chapter with projects that promise to make your outdoor space inspiring and moving (literally).

In this chapter:

• Steppingstone Landscape Path

Designing Paths & Walkways

The purpose of paths and walkways in the landscape is twofold: to visually connect various “rooms” and features; and to map out sensible, accessible, and comfortable walk routes from point A to point B—that is, from patio to garden, from sidewalk to front porch. A utilitarian approach is to lay a path for safety reasons, creating a clear-cut pedestrian runway that is meant to purposefully usher people to a destination. But many paths are much more than a means to an end. Your path will communicate to visitors where to go and how to get there. A less formal path will encourage a slower pace, forcing exploration. Steppingstones artfully placed in a garden will merely suggest a trail through a crowd of plant life. You’ll eventually find the treasure at the end of the trail—prize roses, a gurgling fountain. The pleasure is in the journey.

While designing a path and considering materials for these projects, consider the experience you want people to have as they navigate the walkway. Do you want to guide them quickly without distraction, or do you hope they’ll discover a cozy sitting area along the way? With your goals in mind, you can begin to sketch a road map.

Think of a path as a mini highway system for your yard. You may only require a single walkway that leads from a side garage door, around the house, to the deck out back. Or, your landscape design may include pockets of interest that you want people to discover: a pond, gazebo, bench, garden, or children’s play area. In this case, you’ll need some “side streets” or back roads. Your main artery will probably serve as a safe route with the sheer purpose of clearing the way for pedestrians. Pathways may branch off of this key walkway. These are the scenic byways.

A pebble pathway contained by a loose-laid brick border provides just enough tracking for people to safely meander through a woodland backyard.

Mixing materials can lead to very interesting and pleasing pathway designs, provided it is done with some discretion and design savvy. The loose gravel and flagstone pathway above has a distinct organic quality and a sense of relaxation and flow. The smaller pathway (inset) cobbled together from sections of old railroad ties, rocks and shells certainly is unique, but there is little to tie the elements together visually. In addition, the irregular walking surface created by the short, perpendicularly laid ties and the fairly large rocks does present a tripping hazard. With pathways and steps, surprises are best avoided.

A steppingstone walkway allows grass “grout” to grow. A path is important for guiding the eye, and foot traffic, through a landscape.

Color outside the lines. A straight line is a safe and efficient form for a pathway, but adding a few jogs and bends adds great visual interest.

Materials

Choose materials and structure your paths according to their purpose and your design preferences. Brick, flagstone, concrete pavers, and gravel are popular choices for paths. Their surfaces aren’t completely smooth, promoting skid resistance that allows for safe traction. If you opt for steppingstones, be sure you consider the natural stride of everyone who will use the path regularly. Placing them just an inch too far apart can trip up walkers. (You can walk across concrete with wet feet and measure your stride to determine functional steppingstone placement.) On the other hand, if you simply want to establish a less defined walking zone, you can play with the arrangement of steppingstones and create interesting designs.

Brick, flagstone, gravel, and concrete pavers are readily available and can be formal or casual, depending on how you design the path. For instance, mortared flagstone tends to look somewhat formal, while flagstone set on sand does not. Lay flagstone on a prepared, earthen surface and you can plant rock-loving groundcover varieties such as creeping thyme and moss in between the cracks. Manufactured brick will offer a uniform, clean look. Natural brick has color variances. Recycled brick will blend well in mature landscapes and also provide a rustic look. Decorative steppingstones can jazz up a gravel path.

Suitable materials for pathways include interlocking pavers, cobblestones, flagstones, and gravel. For gravel pathways, choose small aggregates 3/8" to 3/4". The texture looks appealing, and if you choose a variety of sizes and shapes the surface will stay in place. Interlocking pavers have shapes and protrusions that are designed to fit together and create a mechanical bond. Square and rectangular pavers and cobblestones are easier to lay out in a pathway. Flagstones can be laid in a solid pattern or used as steppingstones.

Before committing to a material for your walkway surface, ask yourself these questions:

• How regularly will you use this path?

• What other materials exist in your landscape? (Think patio, retaining walls, etc.)

• What materials will complement your home’s architecture?

• Describe the setting: formal, casual, rustic-country, private, highly visible, etc.

• Who will walk on this path, and do they have special needs? (An even flagstone pathway is safer to traverse than a less uniform walkway of aggregate stone.)

• What are the site conditions? Is the area particularly soggy and prone to puddling? (Stone gets slippery when wet. And wet stone is a welcome environment for moss, which compounds the slick factor.)

Base & Borders

We’ll delve into the specifics of preparing the base for your path in later sections of this book, but for now let’s underscore the importance of setting a solid foundation. Whether your path is purely for foot traffic or primarily a decorative statement (most often, the goal is both of these), you must take steps to secure the base and plan for drainage. You won’t need to install culverts or hire the Army Corps of Engineers for this task. A simple half-inch slope from the center of your path to its edges will direct water away from the middle, preventing puddles and unsafe, slippery conditions. This is called crowning. You’ll notice that your street is slightly crowned, directing water toward the curb and into drainage grates. You will need a similar, much smaller-scale, system for you landscape path.

A tamped firm base with good drainage is vital to a successful pathway project. Compactible gravel makes an excellent base.

Next, consider how you will edge your path. A decorative border is optional, but it allows another opportunity to mix and match materials so as to marry the many different materials used throughout the landscape. For example, if your patio is composed of tumbled concrete pavers, but your home has stone accents, you can create a stone path with a brick border to bring the contrasting surfaces together. Play with the possibilities. Install a brick border along a gravel path, place native rock boulders alongside a sandstone path, or set stone slabs alongside a path of cobbled concrete pavers. Play with different textures and colors as well.

Aside from brick and stone, consider other ways to define your path. Hedges establish an attractive green border, while plastic edging available at home centers will do a fine job of preventing plants and turf from invading your walkway.

Pathways normally require a border to contain the surfacing material and create a mowing edge. Brick pavers can be laid flat or buried deeper on end (called soldier style).

Loose Rock Landscape Path

Loose-fill gravel pathways are perfect for stone gardens, casual yards, and other situations where a hard surface is not required. The material is inexpensive, and its fluidity accommodates curves and irregular edging. Since gravel may be made from any rock, gravel paths may be matched to larger stones in the environment, tying them in to your landscaping. The gravel you choose need not be restricted to stone, either. Industrial and agricultural byproducts, such as cinder and ashes, walnut shells, seashells, and ceramic fragments may also be used as path material.

For a more stable path, choose angular or jagged gravel over rounded materials. However, if your preference is to stroll throughout your landscape barefoot, your feet will be better served with smoother stones, such as river rock or pond pebbles. With stone, look for a crushed product in the 1/4" to 3/4" range. Angular or smooth, stones smaller than that can be tracked into the house, while larger materials are uncomfortable and potentially hazardous to walk on. If it complements your landscaping, use light-colored gravel, such as buff limestone. Visually, it is much easier to follow a light pathway at night because it reflects more moonlight.

Stable edging helps keep the pathway gravel from migrating into the surrounding mulch and soil. When integrated with landscape fabric, the edge keeps invasive perennials and trees from sending roots and shoots into the path. Do not use gravel paths near plants and trees that produce messy fruits, seeds, or other debris that will be difficult to remove from the gravel. Organic matter left on gravel paths will eventually rot into compost that will support weed growth.

A base of compactable gravel under the surface material keeps the pathway firm underfoot. For best results, embed the surface gravel material into the paver base with a plate compactor. This prevents the base from showing through if the gravel at the surface is disturbed. An underlayment of landscape fabric helps stabilize the pathway and blocks weeds, but if you don’t mind pulling an occasional dandelion and are building on firm soil, it can be omitted.

Construction Details

Loose materials can be used as filler between solid surface materials, like flagstone, or laid as the primary groundcover, as shown here.

How to Create a Gravel Pathway

How to Create a Gravel Pathway

Lay out one edge of the path excavation. Use a section of hose or rope to create curves, and use stakes and string to indicate straight sections. Cut 1 × 2 spacers to set the path width and establish the second pathway edge; use another hose and/or more stakes and string to lay out the other edge. Mark both edges with marking paint.

Remove sod in the walkway area using a sod stripper or a power sod cutter (see option, at right). Excavate the soil to a depth of 4" to 6". Measure down from a 2 × 4 placed across the path bed to fine-tune the excavation. Grade the bottom of the excavation flat using a garden rake.

NOTE: If mulch will be used outside the path, make the excavation shallower by the depth of the mulch. Compact the soil with a plate compactor.

Lay landscaping fabric from edge to edge, lapping over the undisturbed ground on either side of the path. On straight sections, you may be able to run parallel to the path with a single strip; on curved paths, it’s easier to lay the fabric perpendicular to the path. Overlap all seams by 6".

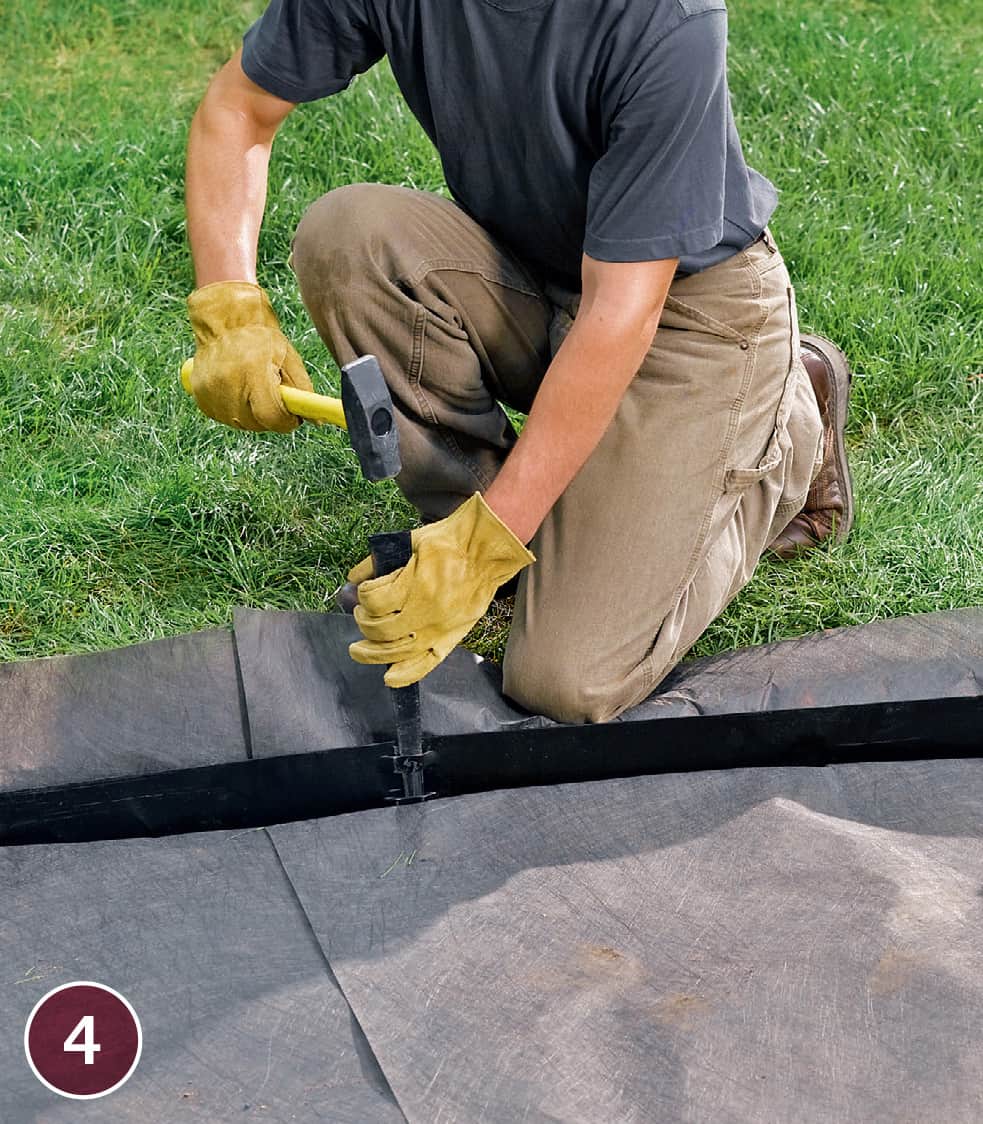

Install edging over the fabric. Shim the edging with small stones, if necessary, so the top edge is 1/2" above grade (if the path passes through grass) or 2" above grade (if it passes through a mulched area). Secure the edging with spikes. To install the second edge, use a 2 × 4 spacer gauge that’s been notched to fit over your edging (see facing page).

Stone or vertical-brick edges may be set in deeper trenches at the sides of the path. Place these on top of the fabric also. You do not have to use additional edging with paver edging, but metal (or other) edging will keep the pavers from wandering.

Trim excess fabric, then backfill behind the edging with dirt and tamp it down carefully with the end of a 2 × 4. This secures the edging and helps it to maintain its shape.

Add a 2"- to 4"-thick layer of compactable gravel over the entire pathway. Rake the gravel flat. Then, spread a thin layer of your surface material over the base gravel.

Tamp the base and surface gravel together using a plate compactor. Be careful not to disturb or damage the edging with the compactor.

Fill in the pathway with the remaining surface gravel. Drag a 2 × 4 across the tops of the edging using a sawing motion, to level the gravel flush with the edging.

Set the edging brick flush with the gravel using a mallet and 2 × 4.

Tamp the surface again using the plate compactor or a hand tamper. Compact the gravel so it is slightly below the top of the edging. This will help keep the gravel from migrating out of the path.

Rinse off the pathway with a hose to wash off dirt and dust and bring out the true colors of the materials.

Steppingstone Landscape Path

A steppingstone path is both a practical and appealing way to traverse a landscape. With large stones as foot landings, you are free to use pretty much any type of fill material in between. You could even place steppingstones on individual footings over ponds and streams, making water the temporary infill that surrounds the stones. The infill does not need to follow a narrow path bed, either. Steppers can be used to cross a broad expanse of gravel, such as a Zen gravel panel or a smaller graveled opening in an alpine rock garden.

Steppingstones in a path serve two purposes: they lead the eye, and they carry the traveler. In both cases, the goal is rarely fast, direct transport, but more of a relaxing stroll that’s comfortable, slow-paced, and above all, natural. Arrange the steppingstones in your walking path according to the gaits and strides of the people that are most likely to use the pathway. Keep in mind that our gaits tend to be longer on a utility path than in a rock garden.

Sometimes steppers are placed more for visual effect, with the knowledge that they will break the pacing rule with artful clusters of stones. Clustering is also an effective way to slow or congregate walkers near a fork in the path or at a good vantage point for a striking feature of the garden.

In the project featured here, landscape edging is used to contain the loose infill material (small aggregate), however a steppingstone path can also be effective without edging. For example, setting a series of steppers directly into your lawn and letting the lawn grass grow between them is a great choice as well.

Steppingstones blend beautifully into many types of landscaping, including rock gardens, ponds, flower or vegetable gardens, or manicured grass lawns.

How to Make a Pebbled Steppingstone Path

How to Make a Pebbled Steppingstone Path

Excavate and prepare a bed for the path as you would for the gravel pathway (see pages 76 to 79), but use coarse building sand instead of compactable gravel for the base layer. Screed the sand flat so it’s 2" below the top of the edging. Do not tamp the sand.

TIP: Low-profile plastic landscape edging is a good choice because it does not compete with the pathway.

Moisten the sand bed, then position the steppingstones in the sand, spacing them for comfortable walking and the desired appearance. As you work, place a 2 × 4 across three adjacent stones to make sure they are even with one another. Add or remove sand beneath the steppers, as needed, to stabilize and level the stones.

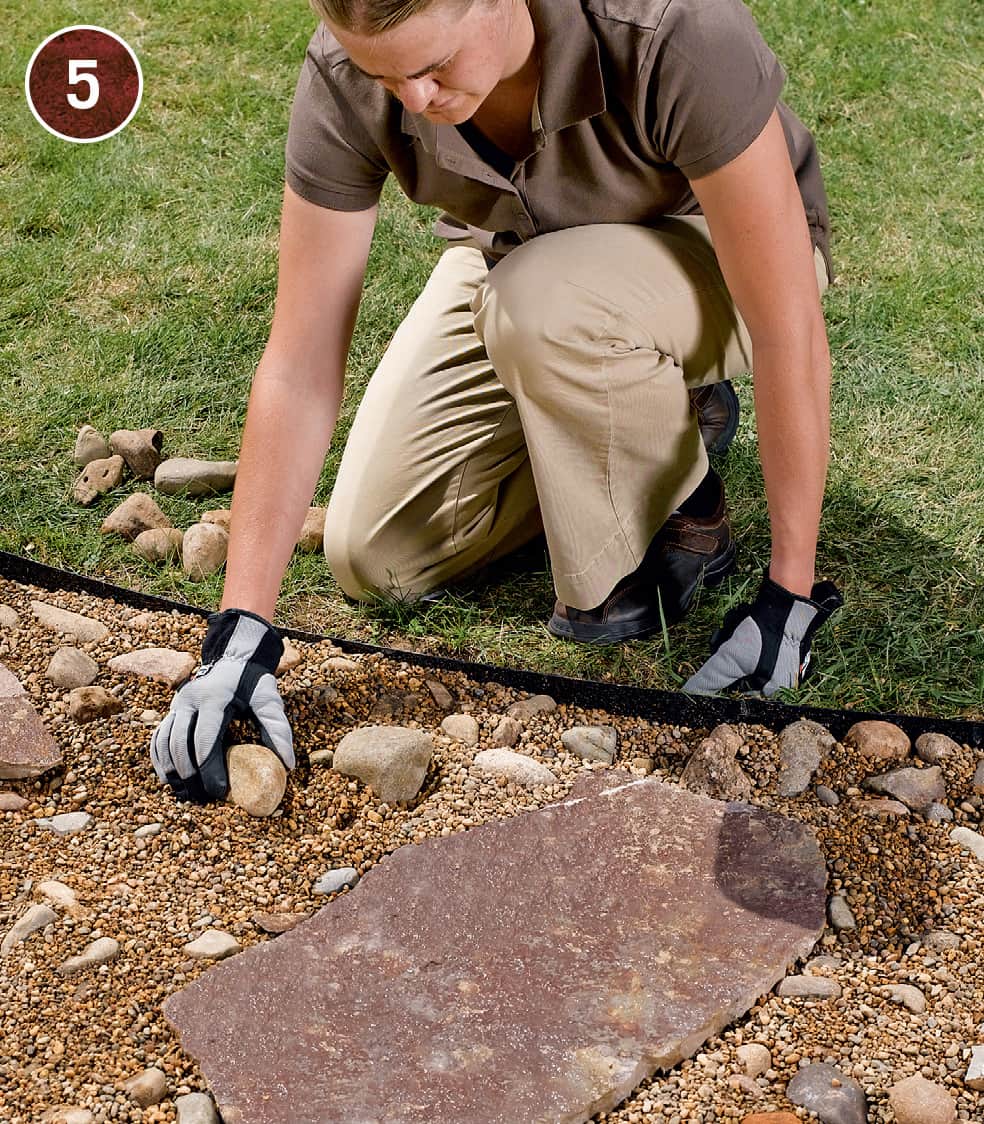

Pour in a layer of larger infill stones (2"-dia. river rock is seen here). Smooth the stones with a garden rake. The infill should be below the tops of the steppingstones. Reserve about one third of the larger diameter rocks.

Add the smaller infill stones, that will migrate down and fill in around the larger infill rocks. To help settle the rocks, you can tamp lightly with a hand tamper, but don’t get too aggressive—the larger rocks might fracture easily.

Scatter the remaining large infill stones across the infill area so they float on top of the other stones. Eventually, they will sink down lower in the pathway and you will need to lift and replace them selectively to maintain the original appearance.

Variations

Move from a formal space to a less orderly area of your landscape by creating a pathway that begins with closely spaced steppers on the formal end and gradually transforms into a mostly-gravel path on the casual end, with only occasional clusters of steppers.

Combine concrete stepping pavers with crushed rock or other small stones for a path with a cleaner, more contemporary look. Follow the same basic techniques used on these two pages, setting the pavers first, then filling in between with the desired infill material(s).

Cast Concrete Steppers

Traditional walkway materials, such as brick and stone, have always been prized for both appearance and durability, but they can be expensive. As an easy and inexpensive alternative, you can build a new concrete path using prefabricated pathway forms. The result is a beautiful pathway that combines the custom look of brick or natural stone with the durability and economy of poured concrete.

Building a path is a great do-it-yourself project. Once you’ve prepared a base for the path, mix the concrete, fill and set the form, and lift the form to reveal the finished design. After a little troweling to smooth the surfaces, you’re ready to create the next section using the same form. Simply repeat the process until the path is complete. Each form creates a section that’s approximately 2 square feet using one 80-pound bag of premixed concrete.

DIY-friendly concrete casting forms are sold in several sizes and configurations. You simply lay them on a prepared surface, fill them with concrete, and remove them once the concrete has set; then, place the form next to the poured section and add another until your pathway is complete. Once all the concrete has dried, you can fill in the gaps between the pavers to further simulate the look of a genuine paver walkway.

How to Estimate Concrete

How to Make a Cast Concrete Path

How to Make a Cast Concrete Path

Prepare the project site by removing sod or soil and excavating the pathway area. Level as needed and add 2" to 4" of compactible gravel to form a sub-base. The base should be a few inches wider than the planned pathway thickness.

Mix a batch of concrete for the first section. Adding colorant to the dry concrete mix gives the concrete the appearance of pavers or cobblestones. Note the ratio of colorant you add to the first batch of concrete so you can repeat it and maintain consistent color. The mixture should be fairly stiff so it holds its shape as it dries instead of slumping.

Place the form at the start of your path and level it. Shovel the wet concrete into the form to fill each cavity. Rap or bounce the form lightly to help settle the concrete. Drag a piece of 2 × 4 across the top in a zigzag motion to strike off the excess concrete.

Remove the form carefully. Test it first by slowly pulling up on the form to make sure the concrete will hold its shape. If it sags, press the form back down, let the concrete dry for a few minutes, and try again. Once you have removed the form, clean off any dried material and reposition it to pour the next section. Repeat as needed.

After removing each form, trowel the edges of the section to create the desired finish. For a nonskid surface, lightly brush the concrete with a broom or whisk broom before the concrete dries. Damp-cure the entire path for 5 to 7 days.

Variation: Quick-and-Easy Steppingstone Path

Place steppingstones in a desired pathway on your lawn. Rotating the stones for jaunty angles and asymmetrical lines is an easy way to liven up a backyard path. Steppingstones are available in a wide variety of textures, shapes, and sizes, so take the time to select what’s right for your garden. Here, natural stones on turf provide a useful and decorative accent.

Allow the steppingstones to remain on the lawn for several days to kill the grass. This provides an outline for excavation and makes turf removal much easier.

Dig around the outline for each stone and excavate the soil or turf. To allow room for a layer of sand to stabilize the steppingstone, dig each hole 2" deeper than the height of the stone. Spread sand in each hole.

Place steppingstones in sand-filled holes, adding or removing sand until each steppingstone is stable. Sand serves as grout, filling in the small gaps between the hole and the surrounding turf.

Arroyo

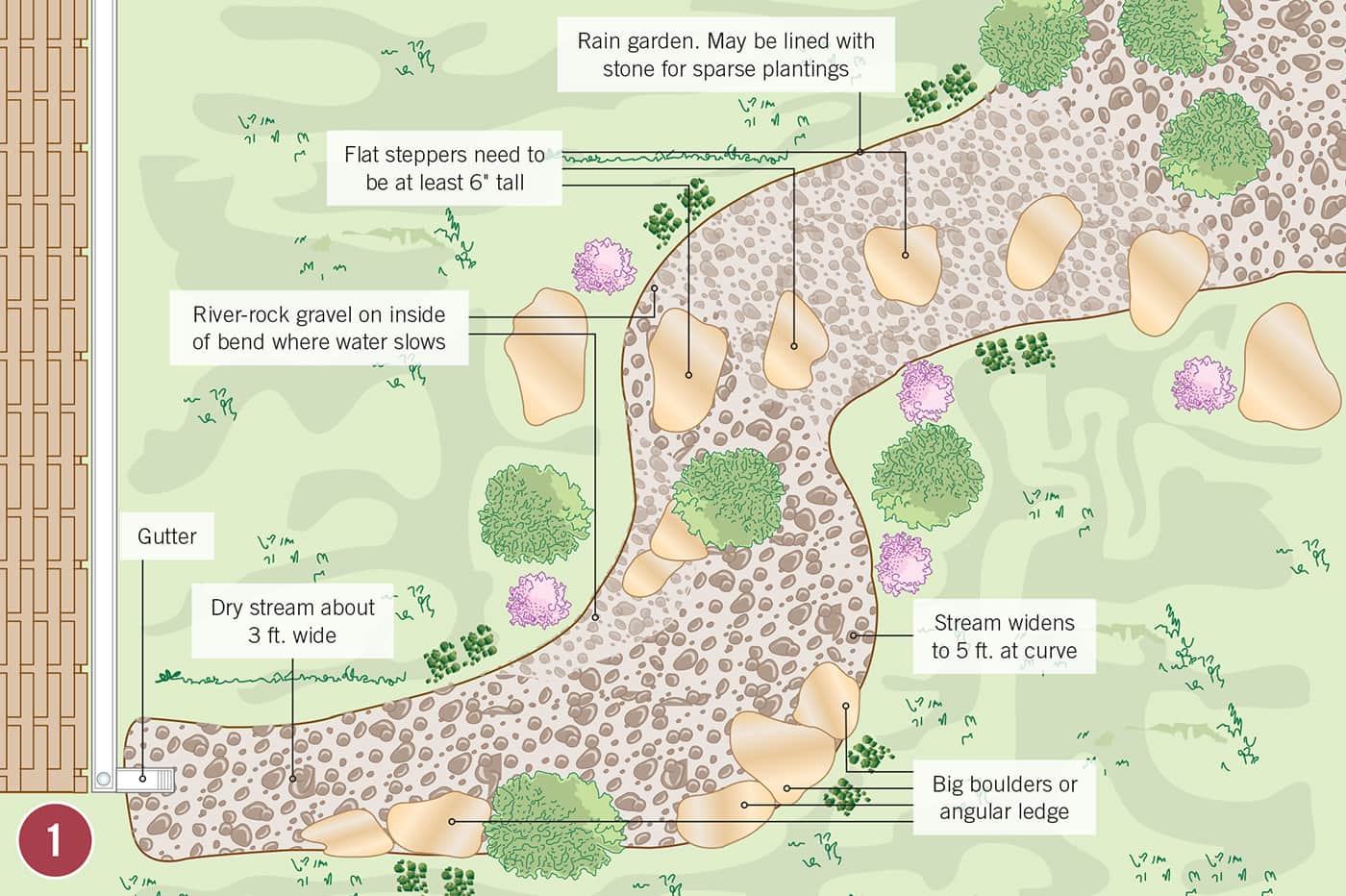

An arroyo is a dry streambed or watercourse in an arid climate that directs water runoff on the rare occasions when there is a downfall. In a home landscape an arroyo may be used for purely decorative purposes, with the placement of stones evoking water where the real thing is scarce. Or it may serve a vital water-management function, directing storm runoff away from building foundations to areas where it may percolate into the ground and irrigate plants, creating a great spot for a rain garden. This water management function is becoming more important as municipalities struggle with an overload of storm sewer water, which can degrade water quality in rivers and lakes. Some communities now offer tax incentives to homeowners who keep water out of the street.

When designing your dry streambed, keep it natural and practical. Use local stone that’s arranged as it would be found in a natural stream. Take a field trip to an area containing natural streams and make some observations. Note how quickly the water depth drops at the outside of bends where only larger stones can withstand the current. By the same token, note how gradually the water level drops at the inside of broad bends where water movement is slow. Place smaller river-rock gravel here, as it would accumulate in a natural stream.

Large heavy stones with flat tops may serve as step stones, allowing paths to cross or even follow dry streambeds.

The most important design standard with dry streambeds is to avoid regularity. Stones are never spaced evenly in nature, nor should they be in your arroyo. If you dig a bed with consistent width, it will look like a canal or a drainage ditch, not a stream. And consider other yard elements and furnishings. For example, an arroyo presents a nice opportunity to add a landscape bridge or two to your yard.

Important: Contact your local waste management bureau before routing water toward a storm sewer; this may be illegal.

An arroyo is a drainage swale lined with rocks that directs runoff water from a point of origin, such as a gutter downspout, to a destination, such as a sewer drain or a rain garden.

How to Build an Arroyo

How to Build an Arroyo

Create a plan for the arroyo. The best designs have a very natural shape and a rock distribution strategy that mimics the look of a stream. Arrange a series of flat steppers at some point to create a bridge.

Lay out the dry stream bed, following the native topography of your yard as much as possible. Mark the borders and then step back and review it from several perspectives.

Excavate the soil to a depth of at least 12" (30 cm) in the arroyo area. Use the soil you dig up to embellish or repair your yard.

Widen the arroyo in selected areas to add interest. Rake and smooth out the soil in the project area.

Install an underlayment of landscape fabric over the entire dry streambed. Keep the fabric loose so you have room to manipulate it later if the need arises.

Set larger boulders at outside bends in the arroyo. Imagine that there is a current to help you visualize where the individual stones could naturally end up.

Place flagstone steppers or boulders with relatively flat surfaces in a steppingstone pattern to make a pathway across the arroyo (left photo). Alternately, create a “bridge” in an area where you’re likely to be walking (right photo).

Add more stones, including steppers and medium-size landscape boulders. Use smaller aggregate to create the streambed, filling in and around, but not covering, the larger rocks.

Dress up your new arroyo by planting native grasses and perennials around its banks.

Classic Garden Bridge

An elegant garden bridge invites you into a landscape by suggesting you stop and spend some time there. Cross a peaceful pond, traverse an arroyo of striking natural stone, or move from one garden space to the next and explore. While a bridge is practical and functions as a way to get from point A to point B, it does so much more. It adds dimension, a sense of romanticism, and the feeling of escaping to somewhere special.

The bridge you see here can be supported with handrails and trellis panels, but left simple as pictured, its Zen appeal complements projects in this book, including: arroyo, garden pond, and rain garden. We think the sleek, modern design blends well in the landscape, providing a focal point without overwhelming a space.

Unlike many landscape and garden bridges that are large, ornate, and designed to be the center of attention, this low cedar bridge has a certain refined elegance that is a direct result of its simple design.

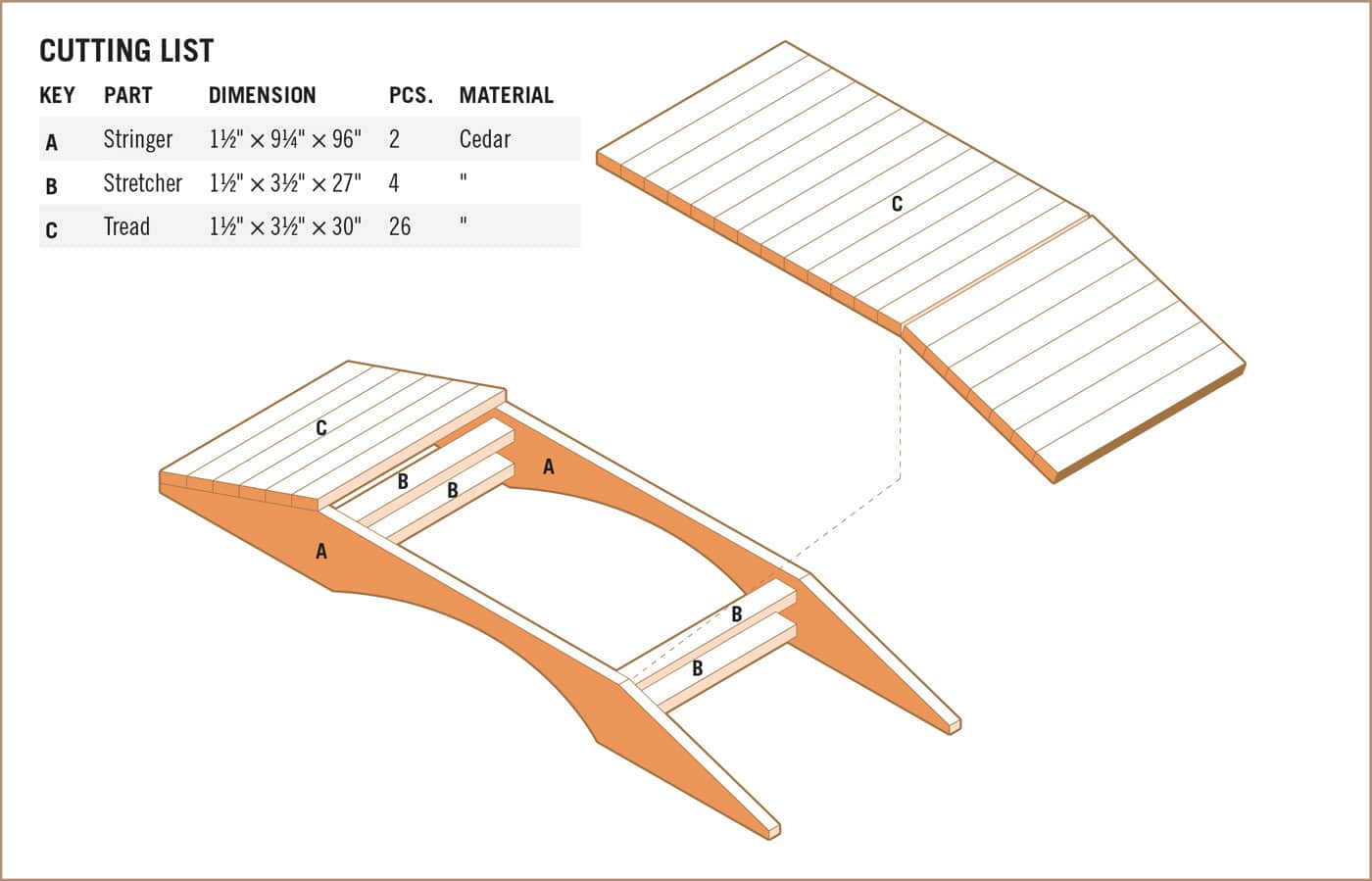

CLASSIC GARDEN BRIDGE

CLASSIC GARDEN BRIDGE

Preparing Bridge Pieces

Study the cutting list carefully and take care when measuring for cuts. The building blocks of this bridge are: stringers, a base, and treads. Read these preliminary instructions carefully, then study the steps before you begin.

Stringers: This first step involves cutting the main structural pieces of the bridge. The stringers have arcs cut into their bottom edges, and the ends of stringers are cut at a slant to create a gradual tread incline. Before you cut stringers, carefully draw guidelines on the wood pieces:

• A centerline across the width of each stringer

• Two lines across the width of each stringer 24 inches to the left and right of the centerline

• Lines at the ends of each stringer, 1 inch up from one long edge

• Diagonal lines from these points to the top of each line to the left and right of the center

Base: Four straight boards called stretchers form the base that support the bridge. Before cutting these pieces, mark stretcher locations on the insides of the stringers, 1 1/2 inches from the top and bottom of the stringers. The outside edges of the stretchers should be 24 inches from the centers of the stringers so the inside edges are flush with the bottoms of the arcs. When working with the stretchers, the footboard may get quite heavy, so you will want to move the project to its final resting place and finish constructing the project there.

Treads: Cut the treads to size according to the cutting list. Once laid on the stringers, treads will be separated with 1/4-inch gaps. Before you install the treads, test-fit them to be sure they are the proper size.

How to Build a Garden Bridge

How to Build a Garden Bridge

Use a circular saw to cut the ends of stringers along the diagonal lines, according to the markings described on the previous page.

Tack a nail on the centerline, 5 1/4" up from the same long edge. Also tack nails along the bottom edge, 20 1/2" to the left and right of the centerline.

Make a marking guide from a thin, flexible strip of scrap wood or plastic, hook it over the center nail, and slide the ends under the outside nails to form a smooth curve. Trace along the guide with a pencil to make the arc cutting line.

Use a jigsaw to make arched cut-outs in the bottoms of the 2 × 10 stringers after removing the nails and marking guide.

Assemble the base by preparing stringers as described on facing page and positioning the stretchers between them. Stand the stringers upright (curve at the bottom) and support bottom stretchers with 1 1/2"-thick spacer blocks for correct spacing. Fasten stretchers between stringers with countersunk 3" deck screws, driven through the stringers and into the ends of the stretchers.

Turn the stringer assembly upside down and attach the top stretchers.

Attach treads after test-fitting them. Leave a 1/4" gap between treads. Secure them with 3"-long countersunk deck screws.

Sand all surfaces to smooth out any rough spots, and apply an exterior wood stain to protect the wood, if desired. You can leave the cedar untreated and it will turn gray, possibly blending with other landscape features.

TEST YOUR IDEAS

TEST YOUR IDEAS

TOOLS & MATERIALS

TOOLS & MATERIALS

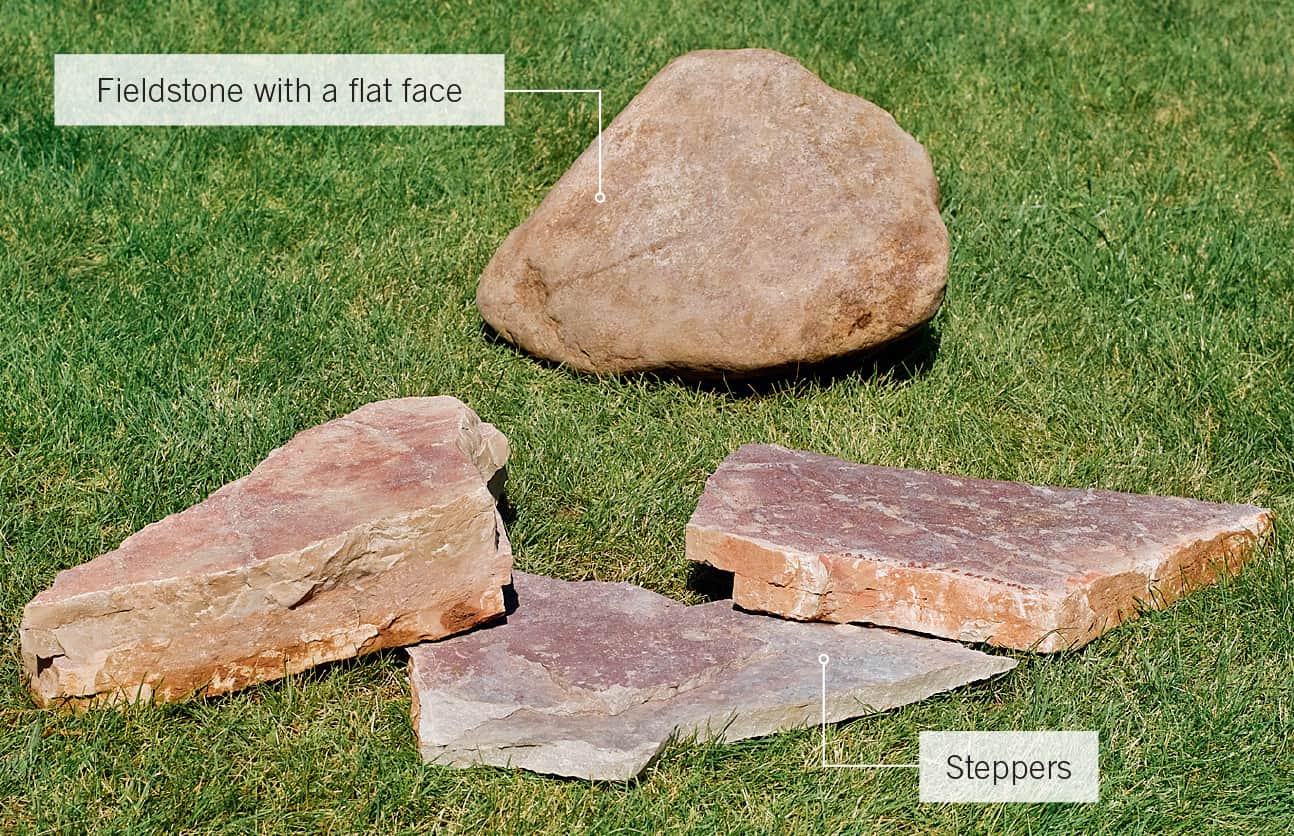

CHOOSING STEPPERS

CHOOSING STEPPERS

How to Make DIY Cast Concrete Steppers

How to Make DIY Cast Concrete Steppers