Stone Walls

What is it about stone walls that inspire? Perhaps it is that they create boundaries and corral a wild, haphazard landscape. Perhaps it is they lend a sense of earthen timelessness and permanence to a landscape; they make a bold-but-natural statement that this outdoor area is well planned, graced with a touchstone structure even as plantings come and go.

Stone walls are more expensive and time-consuming to build than other types of walls, but they stand for decades as testimony to the builder’s patience and craftsmanship. They weather well and require little maintenance. They blend with whatever you want to grow; indeed, their classy ruggedness is a dramatic, natural backdrop and a strikingly satisfying complement to the softness of plants. Finally, they serve as a seat for ruminating souls and a stage for container plants to put on their show.

In this chapter, you’ll learn to design, build, and repair these beautiful barriers. There are many types, but we have chosen project plans for five stone walls that will set your landscape apart. One of the projects is unique in that it creates two-for-one beauty where there was a horrible mowing task; the steep-hill walls double as flower beds. If you’re concerned that stone walls are too tough to build, don’t be. You may want to round up a little help for some of the heavy lifting, but stacking stone is a project you can do yourself—especially with the step-by-step instructions, photos, and illustrations provided.

In this chapter:

• Interlocking Block Retaining Wall

Designing Stone Walls

Walls can accompany stairs, enclose a patio, or frame a garden—but they also can stand alone. Walls are a powerful design tool for creating physical and visual barriers. They can conceal unappealing yard features from the rest of the garden. They set limits, draw lines, divide property. They are an ample platform for growing vines, and if they’re short enough, walls are handy overflow seating if you’re hosting a large patio party.

When deciding on a wall style and material, consider the visual impact of this feature. Walls make a statement, and their appearance will set the tone in your landscape. A tidy brick-paver wall sends a different message than a dry stacked fieldstone structure. A wall composed of natural stone blends with the landscape.

Regarding materials, you can go natural with dry stacked fieldstone, ashlar (typical, blocky wall stone), or choose among an array of manufactured “interlocking” products.

Pre-cast landscape blocks and pavers are very easy to build with. Their interlocking features and uniform shape and size greatly ease the installation process.

A dry-stacked fieldstone wall can look as though it grew right out of the earth. Natural stone belongs in the environment, and it harmonizes with other natural landscape elements. Even without mortar holding the stones together, these walls can last for generations.

Garden Walls

Garden walls may be built using mortar to bind the stones, or they may be dry-stacked. Your climate, wall dimensions, and materials will dictate the best construction method. Mortared walls usually require a reinforced concrete footing poured below the frost line so the wall does not flex and crack at the joints. To further prevent freeze/thaw damage, keep water out of a mortar wall by topping the structure with capstones, which helps seal the top of the wall and thus limit water penetration. Mortar allows you to meld together interesting and rounded, decorative stones that need sticking power. Sealing seams between rock layers will not allow plants to peek through, which can be a pro or con, depending on your desire for the overall effect.

Not all walls require mortar, and you may prefer the aged-and-tumbled look of a dry-stacked wall. These walls do not require a poured concrete base since they can flex with the movement of the earth without cracking. Dry-stacked walls freely accommodate freeze-and-thaw cycles. Constructing such a wall is like piecing together a complex puzzle: no two pieces are truly a fit until you cut and rearrange stones, wedge shards into gaps, and artfully create a continuous surface. If you’re not up for the challenge, you can hire a professional.

Tumbled concrete wall block can blend almost seamlessly with a patio or walkway made of similar material.

The classic stone garden wall recalls the origins of the building technique: as fields and pastures were cleared of rocks and impediments, the stones were simply stacked into short walls for storage. The walls also had the utilitarian job of keeping animals penned in and marking boundaries.

Retaining Walls

As the name suggests, a retaining wall holds back soil. In essence, a retaining wall turns a slope into a plateau-and-drop. Rather than a steep grade, you have a flat-planed surface supported by a sturdy wall. This allows you to readily use the flat space for planting, placing furniture, or even laying a patio. The dramatic drop adds interest and utility to a landscape. A common technique for long, sloped yards is to terrace several stepped-down retaining walls, creating earthen landings that break up the slope into manageable sections.

When building a stone retaining wall, you can use natural materials or interlocking blocks designed for the express purpose of stacking. Either can bear the weight of the heavy soil being retained, but cast blocks are DIY-friendly, durable, and easier on your wallet than natural stone. You can purchase interlocking blocks with natural finishes that blend better with the environment than some of the first-generation products did. You don’t need to worry about shaping landscaping blocks because the flat tops and bottoms of interlocking blocks are smooth and ready to stack.

You can also go natural with materials and opt for ashlar that has been split into rectangular blocks. Stacked fieldstone accomplishes a rustic look. A row of boulders is an artistic way to create a boundary.

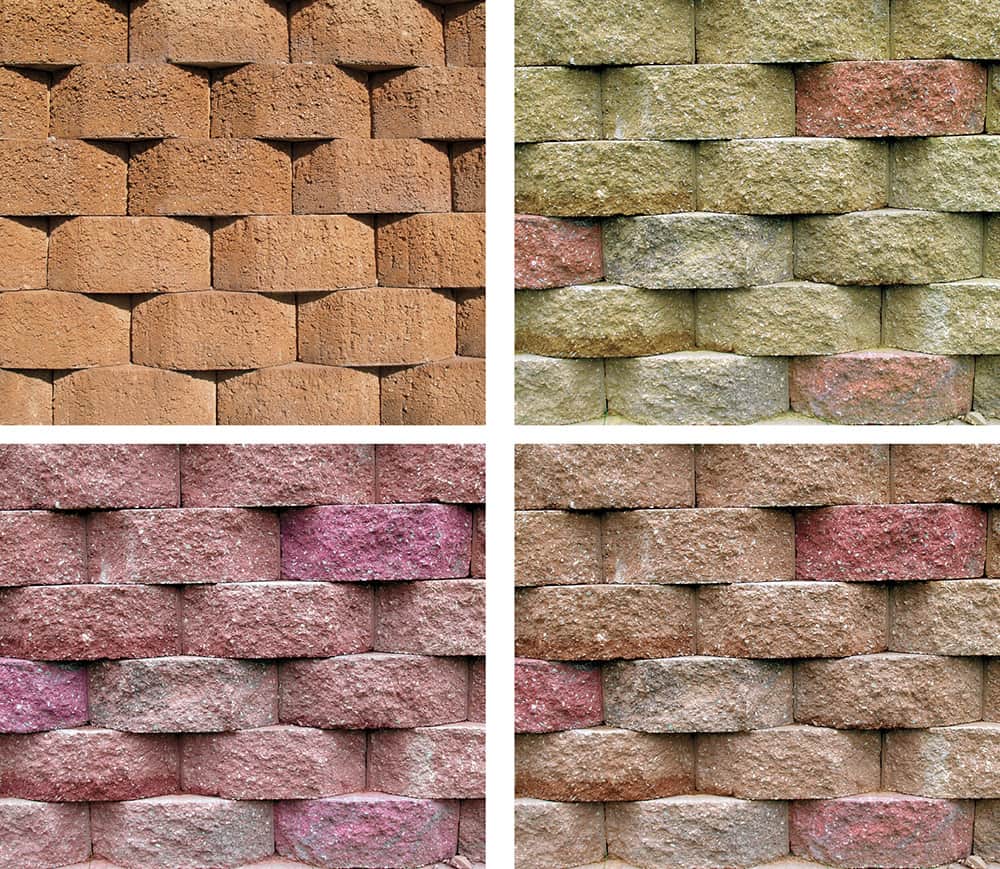

While few manufactured interlocking blocks will ever be mistaken for natural stone, the options in color, size, surface texture and shape have increased dramatically in recent years.

Stone Wall Solution

No matter how small your yard, mowing a steep slope can be a dreadful task. And if you’re an avid gardener, you’d much rather groom a series of luscious planting beds than maneuver a lawnmower on a treacherous hill. That’s why the front yard of this small, city lot was transformed with a series of beautiful stone walls. The following pages show you exactly how this landscape project was accomplished.

Although building a dry-stacked stone wall like this one is time-consuming, it does not require special masonry skills. And it is usually less strenuous than working with manufactured concrete landscape blocks, which are typically heavier than limestone.

DESIGN VARIATION: Adding outcroppings. To help support mounds of soil and plants within each tier, place small boulders as outcroppings within the tiers. Strategically set to support the greatest elevation changes, these rocks are partially submerged in the soil to help them stay in position. In some spots, the wall stone can be shaped to wrap around the boulder (inset).

This limestone retaining wall blends naturally into the hillside and complements the bungalow house beyond.

How to Build a Dry-stack Stone Retaining Wall

How to Build a Dry-stack Stone Retaining Wall

Once your design is complete and has received any required municipal building permits, begin the excavation. For this wall, a 12"-wide × 7"-deep trench was dug along the edge of the sidewalk, with care taken not to disturb the soil below. Smooth the bottom of the trench, making sure it is level with the horizon (which is typically not parallel with the grade of the sidewalk). Then, spread a 2" layer of compactable 3/4" open-grade gravel, which is angular and contains no crushed material. The angled surfaces of the stones help to lock them in place, preventing shifting, and the absence of crushed material allows water to drain more easily. Pack the 2" layer using a power plate compacter, the top of a maul or a tamper. Add another 2" of gravel and pack again, continuing until you have a smooth, level 4"-thick base. (The remaining 3" of trench depth allows the first course of stone to be below grade.)

TIP: A power plate compactor is faster and more effective than hand tamping, and you can rent one from most home centers and rental companies. They weigh nearly 200 pounds but move along easily when running. Wear hearing and eye protection, gloves, and reinforced-toe boots.

Lay the base course of rocks directly onto the compacted sub-base, following your plan. As with any wall construction, the base course sets the stage for the rest of the project. For this first layer, you can use stones that have odd shapes or different thicknesses, as long as the top surfaces are all even and level. Pound down any high spots using the top end of a maul: it is ideal for tamping down the high end of a stone or for packing smaller areas of gravel. The tool’s weight and long handle make it easy to lift and drop, and the flat top works as a mini plate compactor. Check for level front-to-back and side-to-side. If you can’t get it perfect, err on the side of a slightly higher front edge than back.

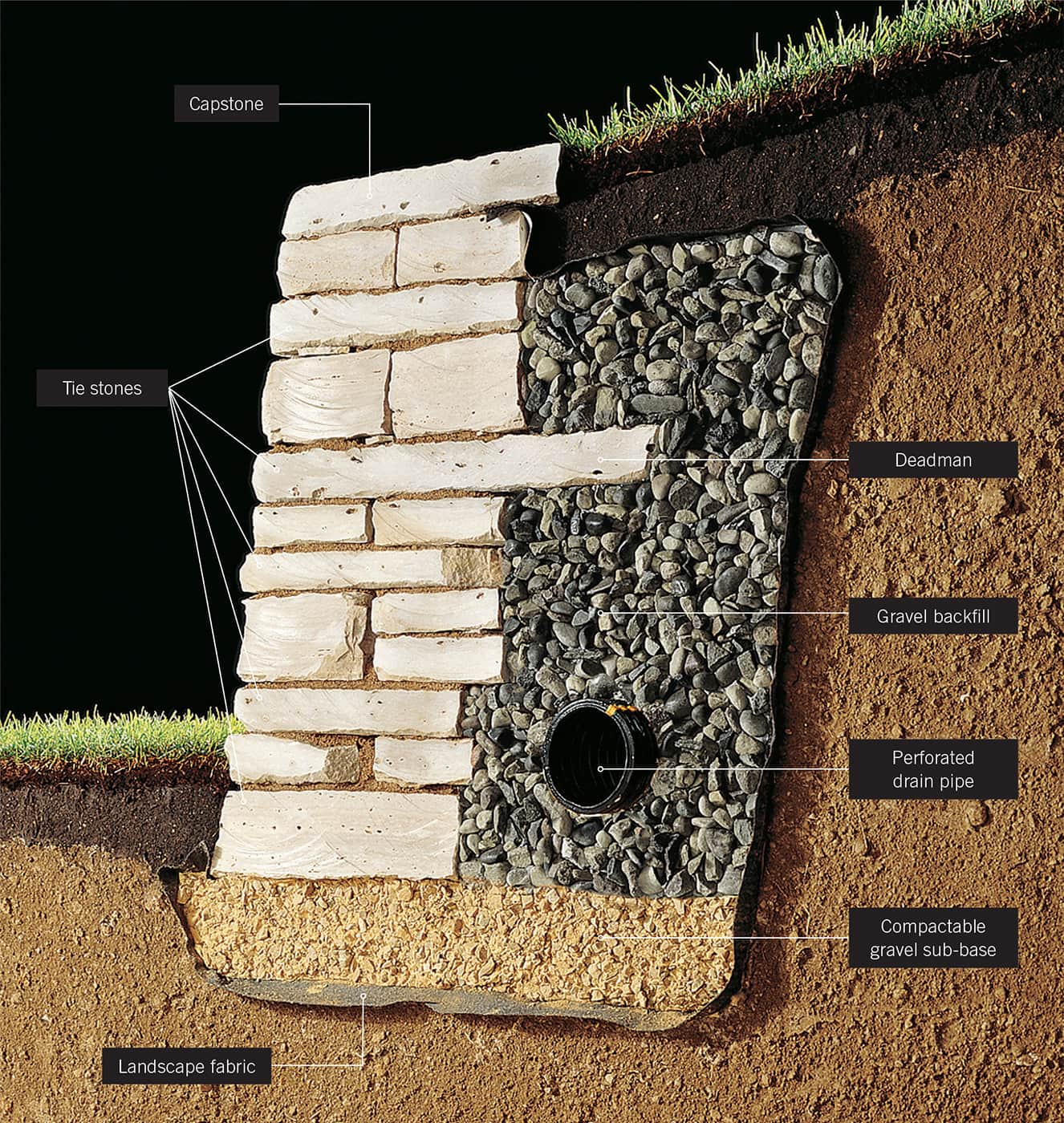

Install the next course, which should be fully above grade in most cases. As you install each stone, flip and turn it until you have a solid fit. You might need to try a different one for compatibility with neighboring stones and with the base. Set the front face of each new row 1/4" back from the previous row (called the setback). Regardless of their finished height, stone walls require an 8"- to 10"-wide layer of 3/4" gravel behind them. If your site has clay soil, which is prone to hydrostatic pressure and can cause any retaining wall to bulge and heave, use open-grade gravel (without crushed fines that harden when they dry) behind the wall to allow rain and melting snow to drain through.

Put a stone sliver (shim) in any wedge-shape openings along the back sides; then fill behind it with gravel. The shim prevents gravel from passing through the spaces.

TIP: Keep a bucket of limestone chips handy to fill gaps and function as shims. These shims become tightly affixed under the weight of the wall.

Stabilize the stones. Natural stones’ irregular shapes sometimes make a slight “rocking” movement unavoidable. You can compensate by shimming with a stone chip (called chinking) under the offending rock. Where needed, you can knock off protruding edges of stones with a maul. Try to avoid leaving gaps between neighboring stones, but where they occur, fill vertical spaces with a stone chip and gravel.

Each row of stones is stepped back (battered) 1/4" along the front faces. It’s a subtle graduation, apparent only when compared with a level. Battering adds significant strength to a dry-stacked wall. Use various sizes of levels to check each stone as you install it, adjusting for level front-to-back and side-to-side. Continue to backfill with gravel as you add each new course.

TIP: If your soil is very sandy, you can add landscape fabric between the gravel backfill and the soil behind it. Do not lay fabric directly against the back of the wall.

Construct the return wall as you build so you can weave them into the courses of the main wall. The return walls (the sections that run alongside the steps and into the hill) need to extend into the soil at least 6" beyond their exposed portions. The hidden portions must also be supported with packed gravel and a course of base stone.

Install the top course using the longest, flattest stones you have (many stoneyards sell these stones separately as “capstones”). Avoid capstones that are more than 2" thick. Dry-lay and level the entire top course. Then, tip back each stone so you can set the top courses back into a 1"-thick bed of mortar applied to the rear halves of the surfaces of the stones below. This keeps the capstones from sliding or becoming otherwise displaced. Backfill with gravel: To allow room for a layer of soil and plants, stop adding gravel backfill when you’re 5" shy of the top of the wall. You may choose to place landscape fabric on top of the gravel before adding the soil.

TIP: To prevent soil from seeping past the top layer of stone, you can pack mortar along the back of the capstone row as well.

Stone-Terrace Accent Wall

Rough-cut wall stones may be dry-stacked (without mortar) into retaining walls, garden walls, and other stonescape features. Dry-stack walls are able to move and shift with the frost, and they also drain well so they don’t require deep footings and drainage tiles. Unlike fieldstone and boulder walls, short wall-stone walls can be just a single stone thick.

In the project featured here, we use rough-split limestone blocks about 8 by 4 inches thick and in varying lengths. Walls like this may be built up to 3 feet tall, but keep them shorter if you can, to be safe. Building multiple short walls is often a more effective way to manage a slope than to build one taller wall. Called terracing, this practice requires some planning. Ideally, the flat ground between pairs of walls will be approximately the uniform size.

A dry-laid natural stone retaining wall is a very organic-looking structure compared to interlocking block retaining walls (see page 118). One way to exploit the natural look is to plant some of your favorite stone-garden perennials in the joints as you build the wall(s). Usually one plant or a cluster of three will add interest to a wall without suffocating it in vegetation or compromising its stability. Avoid plants that get very large or develop thick, woody roots or stems that may compromise the stability of the wall.

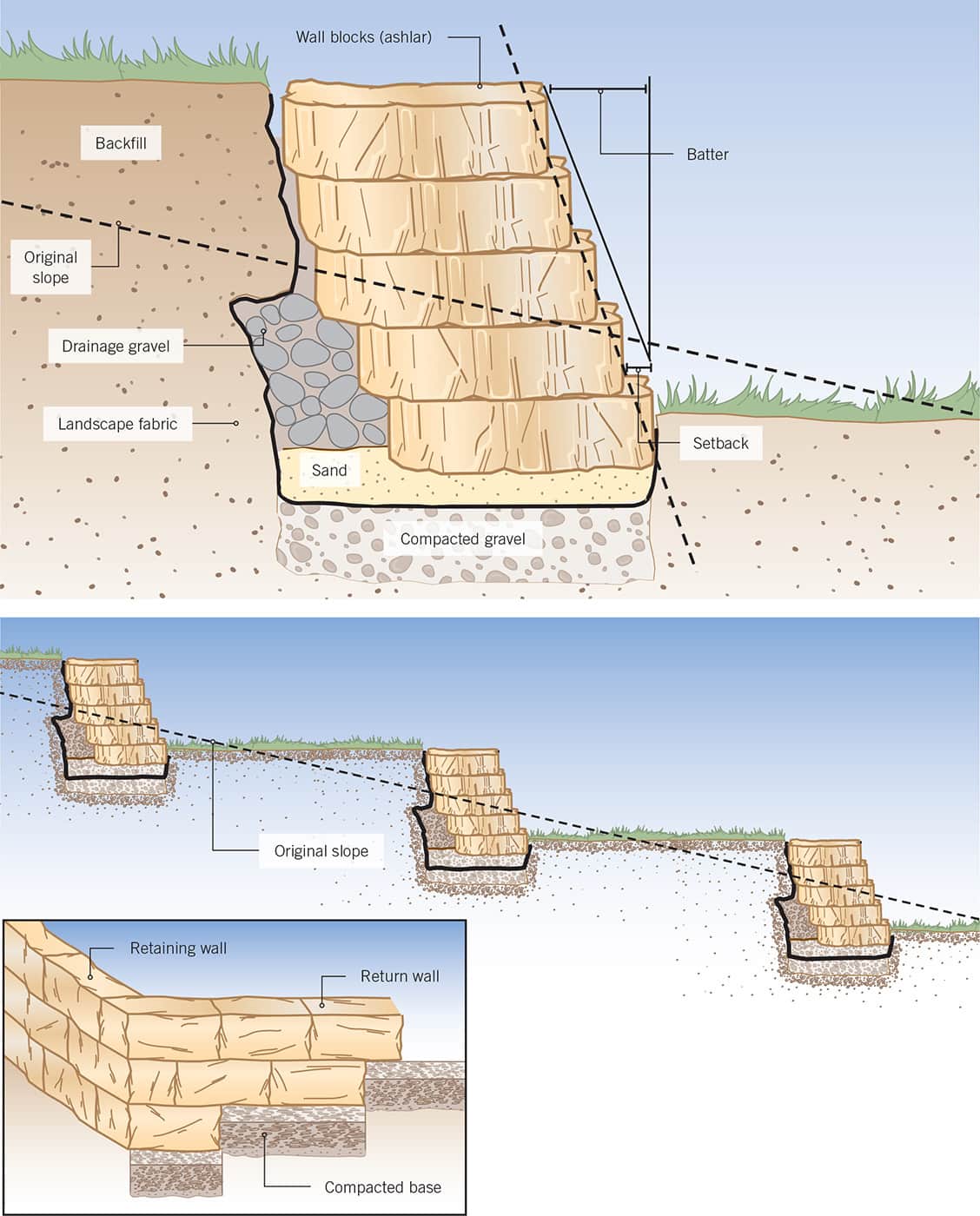

A well-built retaining wall has a slight lean, called a batter, back into the slope. It has a solid base and the bottom course is dug in behind the lower terrace. Drainage gravel can help keep the soil from turning to mud, which will slump and press against the wall.

The same basic techniques used to stack natural stone in a retaining wall may be used for building a short garden wall as well. Obviously, there is no need for drainage allowances or wall returns in a garden wall. Simply prepare a base similar to the one shown here and begin stacking. The wall will look best if it wanders and meanders a bit. Unless you’re building a very short wall (less than 18 inches), use two parallel courses that lean against one another for the basic construction. Cap it with flat capstones that run the full width of the wall (see page 114).

A natural stone retaining wall not only adds a stunning framework to your landscape, but it also lends a practical hand to prevent hillsides and slopes from deteriorating over time.

Cross-Sections: Stone Retaining Walls

A stone retaining wall breaks up a slope to neat flat lawn areas that are more usable (top). A series of walls and terraces (bottom) break up larger slopes. Short return walls (inset) create transitions to the yard.

How to How to Build a Stone Retaining Wall

How to How to Build a Stone Retaining Wall

Dig into the slope to create a trench for the first wall. Reserve the soil you remove nearby—you’ll want to backfill with it when the wall is done.

Level the bottom of the trench and measure to make sure you’ve excavated deeply enough.

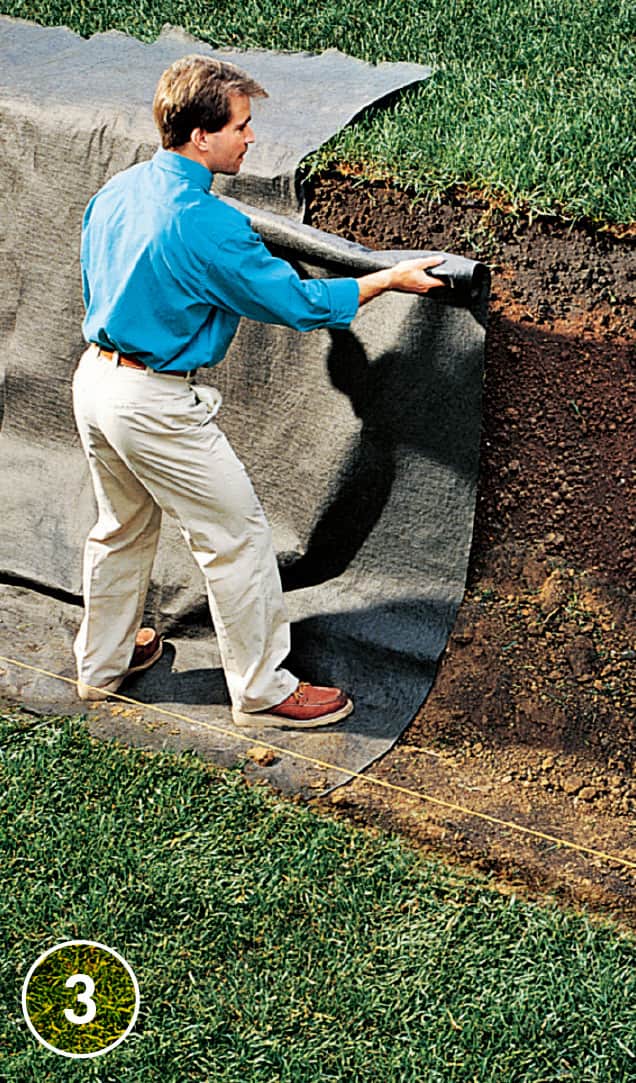

After compacting a base, cover the trench and hill slope with landscape fabric, and then pour and level a 1" layer of coarse sand.

Place the first course of stones in rough position. Run a level mason’s string at the average height of the stones.

Add or remove gravel under each stone to bring the front edges level with the mason’s string.

Begin the second course with a longer stone on each end so the vertical gaps between stones are staggered over the first course.

Finish out the second course. Use shards and chips of stone as shims where needed to stabilize the stones. Check to make sure the 1/2" setback is followed.

Finish setting the return stones in the second course, making adjustments as needed for the return to be level.

Backfill behind the wall with river rock or another good drainage rock.

Fold the landscape fabric over the drainage rock (the main job of the fabric is to keep soil from migrating into the drainage rock and out the wall) and backfill behind it with soil to level the ground.

Trim the landscape fabric just behind the back of the wall, near the top.

Finish the wall by capping it off with some of your nicer, long flat stones. Bond them with block-and-stone adhesive.

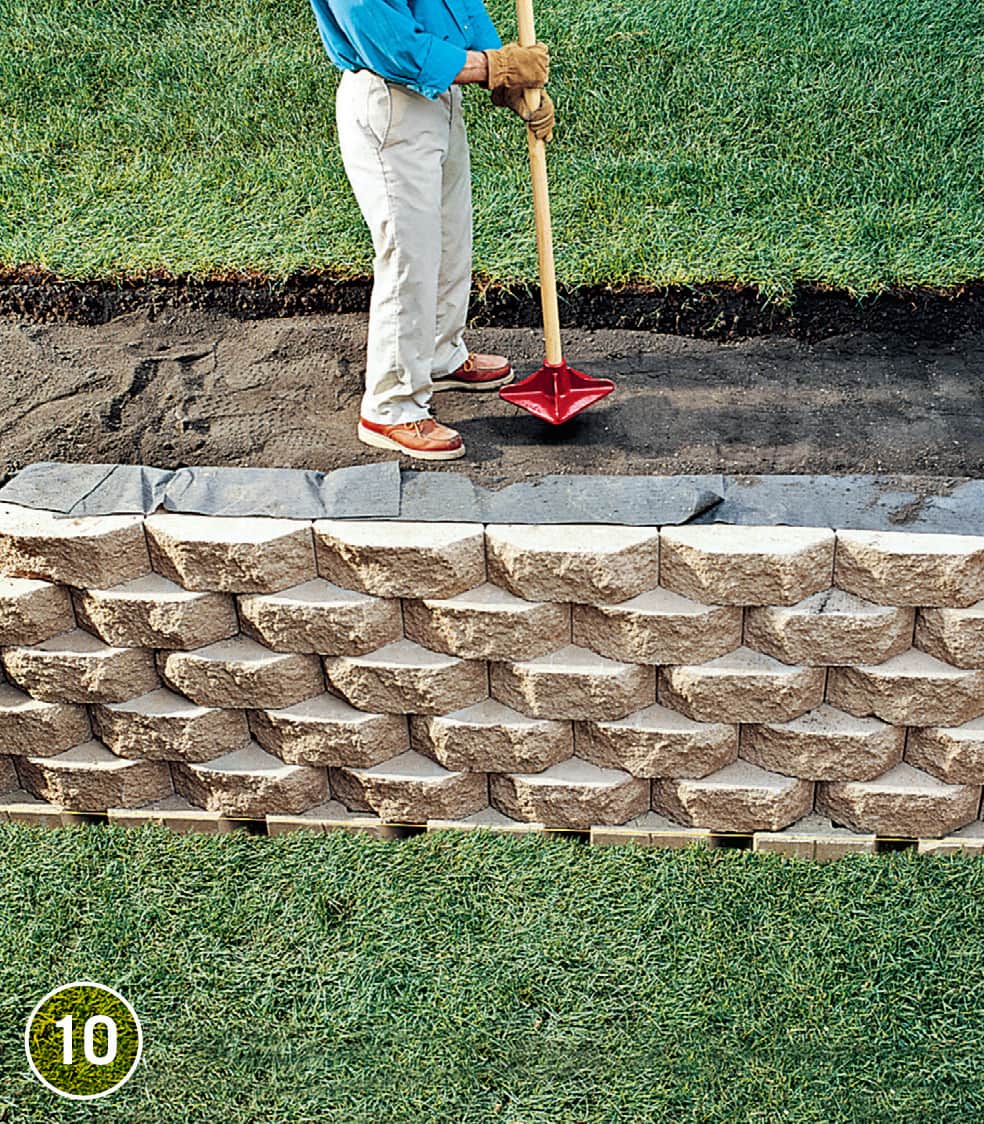

Level off the soil behind the wall with a garden rake. Add additional walls if you are terracing.

Interlocking Block Retaining Wall

Think of retaining walls as shelves in your landscape where colorful plants can be on display, or as layers that carve nooks out of a sloped area to make the space more user-friendly. The fact is, keeping grass alive on a steep slope is virtually mission impossible. You can prevent erosion and form levels of usable space by building a retaining wall, or series of walls.

Retaining walls may be functional—serving to literally “retain” land at various levels on a slope; or purely aesthetic, as a way to add visual, vertical interest to a flat landscape. In this case, you’ll be bringing in soil to backfill the retaining wall. Regardless of the reason for building a retaining wall, the materials available today make the job much like putting together a puzzle. You don’t need mortar, and you can find interlocking block in various textures and colors that complement existing architectural features. Some types of block simply stack, while others are held together by an overlapping system of flanges. These flanges automatically set the backward pitch as blocks are stacked. Still, some blocks use fiberglass pins.

Terraced retaining walls work well on steep hillsides. Two or more short retaining walls are easier to install and more stable than a single, tall retaining wall. Construct the terraces so each wall is no higher than 3 ft.

Design Considerations

If your slope exceeds 4 feet in height, create a terrace effect with a series of retaining walls. Build the first retaining wall, then progress up the slope and build the next, allowing several feet between layers. The bleacher effect provides shelves for plantings and reduces erosion.

If your retaining wall will exceed 4 feet in height, consider bringing in a professional to assist with the job. The higher the wall, the more pressure—thousands of pounds—it must withstand from soil and water. Also, significant walls may require a building permit or specially engineered design. Keep in mind, interlocking block weights up to 80 pounds each, so you’ll want to draft some helpers regardless of the project height. You can use cut stone rather than interlocking block and the project steps are the same. Both materials are durable and easy to work with.

Finally, tune into potential drainage issues before breaking ground. A wall can be damaged when water saturates the soil behind block or stone. You may need to dig a drainage swale in low-lying areas before beginning. This project includes a drainpipe to usher water away from the wall.

Increase the level area above the wall (A) by positioning the wall well forward from the top of the hill. Fill in behind the wall with extra soil, which is available from sand-and-gravel companies. Keep the basic shape of your yard (B) by positioning the wall near the top of the hillside. Use the soil removed at the base of the hill to fill in near the top of the wall.

How to Build a Retaining Wall Using Interlocking Block

How to Build a Retaining Wall Using Interlocking Block

Interlocking wall blocks do not need mortar. Some types are held together with a system of overlapping flanges that automatically set the backward pitch (batter) as the blocks are stacked, as shown in this project. Other types of blocks use fiberglass pins (inset).

Excavate the hillside, if necessary. Allow 12" of space for crushed stone backfill between the back of the wall and the hillside. Use stakes to mark the front edge of the wall. Connect the stakes with mason’s string and use a line level to check for level.

Dig out the bottom of the excavation below ground level, so it is 6" lower than the height of the block. For example, if you use 6"-thick block, dig down 12". Measure down from the string to make sure the bottom base is level.

Line the excavation with strips of landscape fabric cut 3 ft. longer than the planned height of the wall. Make sure all seams overlap by at least 6".

Spread a 6" layer of compactable gravel over the bottom of the excavation as a sub-base and pack it thoroughly. A rented tamping machine, or jumping jack, works better than a hand tamper for packing the sub-base.

Lay the first course of block, aligning the front edges with the mason’s string. (When using flanged block, place the first course upside down and backward.) Check frequently with a level, and adjust, if necessary, by adding or removing sub-base material below the blocks.

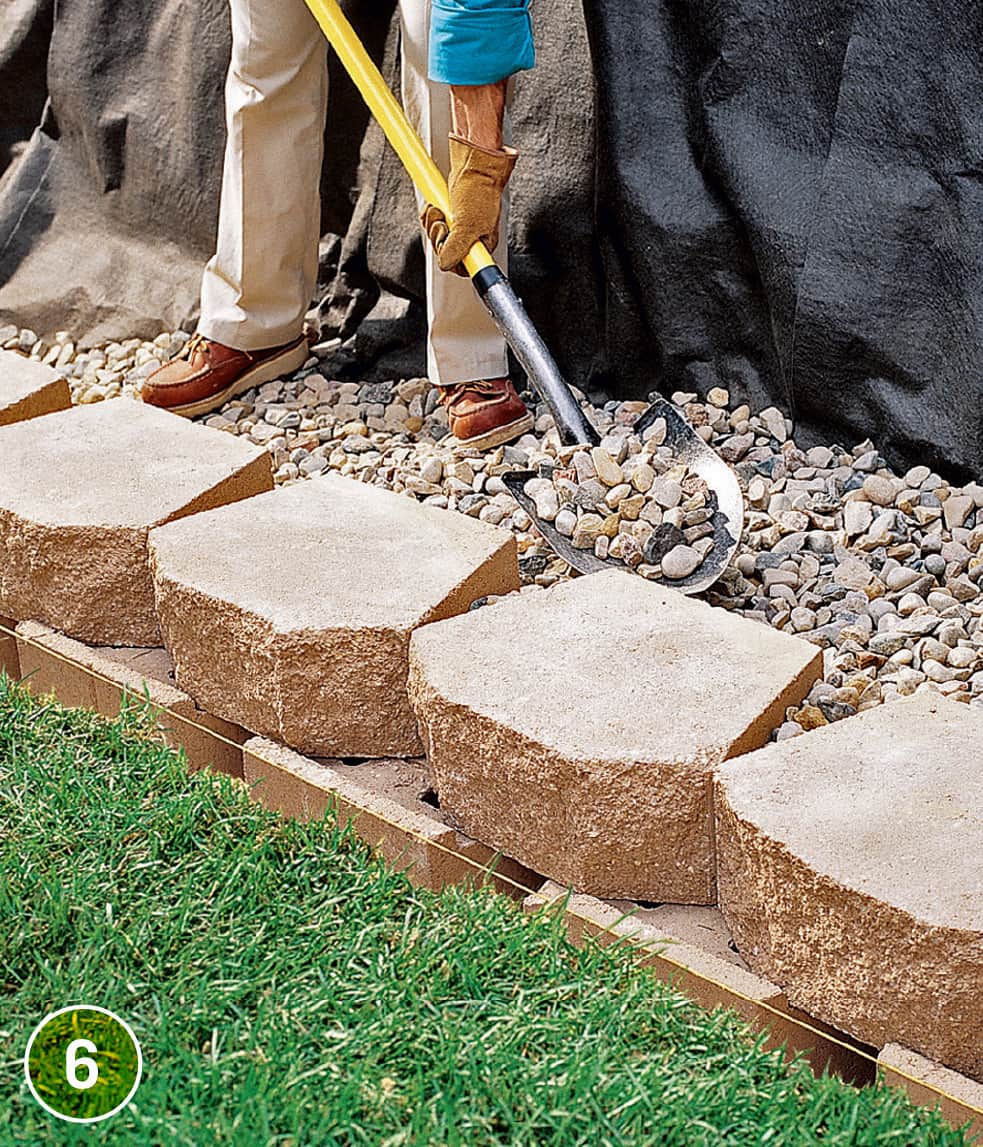

Lay the second course of block according to manufacturer’s instructions, checking to make sure the blocks are level. (Lay flanged block with the flanges tight against the underlying course.) Add 3" to 4" of gravel behind the block and pack it with a hand tamper.

Make half-blocks for the corners and ends of a wall and use them to stagger vertical joints between courses. Score full blocks with a circular saw and masonry blade, and then break the blocks along the scored line with a maul and chisel.

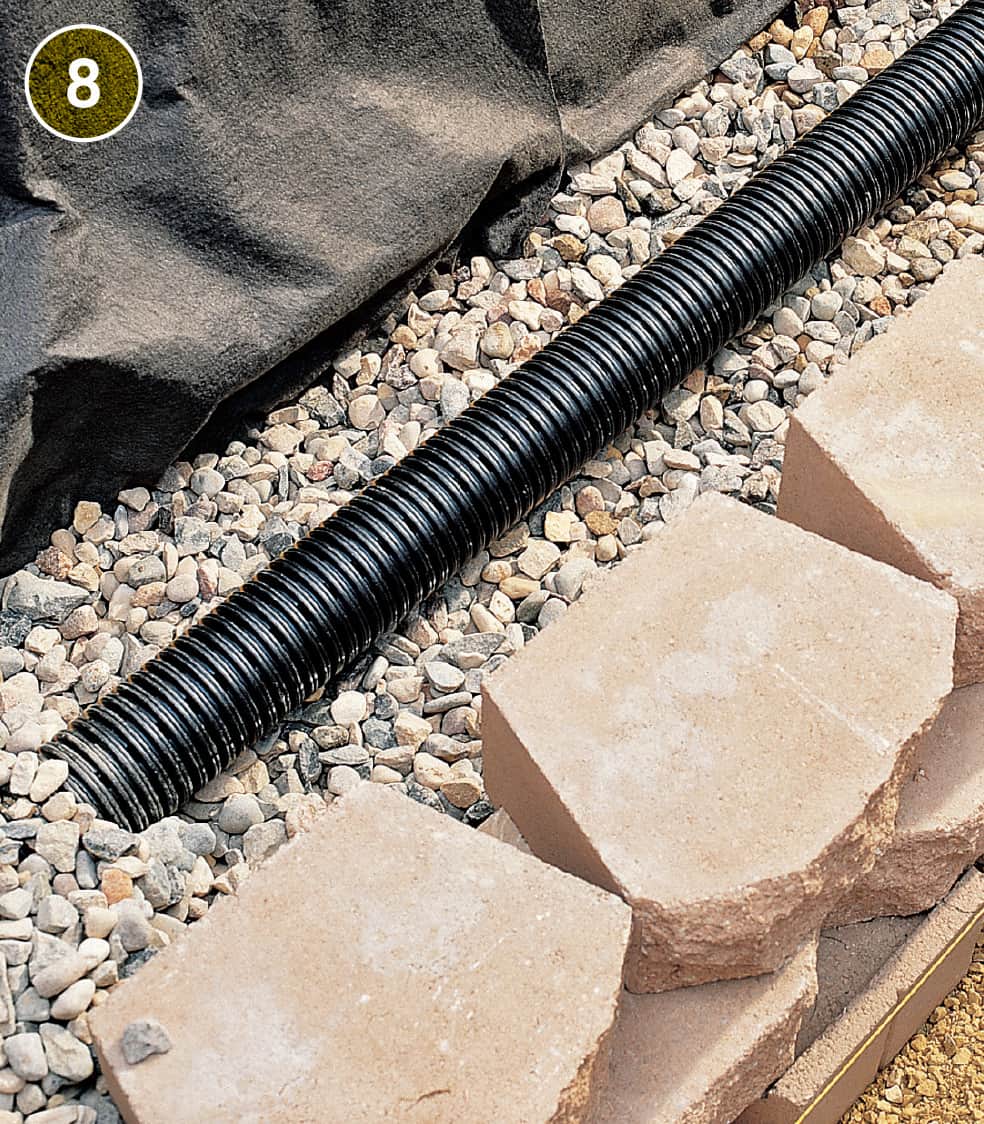

Add and tamp crushed stone, as needed, to create a slight downward pitch (about 1/4" of height per foot of pipe) leading to the drainpipe outlet. Place the drainpipe on the crushed stone, 6" behind the wall, with the perforations face down. Make sure the pipe outlet is unobstructed. Lay courses of block until the wall is about 18" above ground level, staggering the vertical joints.

Fill behind the wall with crushed stone and pack it thoroughly with the hand tamper. Lay the remaining courses of block, except for the cap row, backfilling with crushed stone and packing with the tamper as you go.

Before laying the cap block, fold the end of the landscape fabric over the crushed stone backfill. Add a thin layer of topsoil over the fabric, and then pack it thoroughly with a hand tamper. Fold any excess landscape fabric back over the tamped soil.

Apply landscape construction adhesive to the top course of block, and then lay the cap block. Use topsoil to fill in behind the wall and to fill in the base at the front of the wall. Install sod or plants as desired.

How to Add a Curve to an Interlocking Block Retaining Wall

How to Add a Curve to an Interlocking Block Retaining Wall

Outline the curve by first driving a stake at each end and then driving another stake at the point where lines extended from the first stakes would form a right angle. Tie a mason’s string to the right-angle stake, extended to match the distance to the other two stakes, establishing the radius of the curve. Mark the curve by swinging flour or spray paint at the string end, like a compass.

Excavate for the wall section, following the curved layout line. To install the first course of landscape blocks, turn them upside down and backwards and align them with the radius curve. Use a 4-ft. level to ensure the blocks sit level and are properly placed.

Install subsequent courses so the overlapping flange sits flush against the back of the blocks in the course below. As you install each course, the radius will change because of the backwards pitch of the wall, affecting the layout of the courses. Where necessary, trim blocks to size. Install using landscape construction adhesive, taking care to maintain the running bond.

Use half blocks or cut blocks to create finished ends on open ends of the wall.

Dry-stack Garden Wall

Stone walls are beautiful, long-lasting structures that are surprisingly easy to build provided you plan carefully. A low stone wall can be constructed without mortar using a centuries-old method known as dry-laying. With this technique, the wall is actually formed by two separate stacks that lean together slightly. The position and weight of the two stacks support each other, forming a single, sturdy wall. A dry-stone wall can be built to any length, but its width must be at least half of its height.

You can purchase stone for this project from a quarry or stone supplier, where different sizes, shapes, and colors of stone are sold, priced by the ton. The quarry or stone center can also sell you Type M mortar—necessary for bonding the capstones to the top of the wall.

Building dry-stone walls requires patience and a fair amount of physical effort. The stones must be sorted by size and shape. You’ll probably also need to shape some of the stones to achieve consistent spacing and a general appearance that appeals to you.

To shape a stone, score it using a circular saw outfitted with a masonry blade. Place a mason’s chisel on the score line and strike with a maul until the stone breaks. Wear safety glasses when using stonecutting tools.

It is easiest to build a dry-stone wall with ashlar—stone that has been split into roughly rectangular blocks. Ashlar stone is stacked in the same running-bond pattern used in brick wall construction; each stone overlaps a joint in the previous course. This technique avoids long vertical joints, resulting in a wall that is attractive and also strong.

How to Build a Dry-Stone Wall

How to Build a Dry-Stone Wall

Lay out the wall site using stakes and mason’s string. Dig a 6"-deep trench that extends 6" beyond the wall on all sides. Add a 4" crushed stone sub-base to the trench, creating a “V” shape by sloping the sub-base so the center is about 2" deeper than the edges.

Select appropriate stones and lay the first course. Place pairs of stones side by side, flush with the edges of the trench and sloping toward the center. Use stones of similar height; position uneven sides face down. Fill any gaps between the shaping stones with small filler stones.

Lay the next course, staggering the joints. Use pairs of stones of varying lengths to offset the center joint. Alternate stone length and keep the height even, stacking pairs of thin stones if necessary to maintain consistent height. Place filler stones in the gaps.

Every other course, place a tie stone every 3 ft. You may need to split the tie stones to length. Check the wall periodically for level.

Mortar the capstones to the top of the wall, keeping the mortar at least 6" from the edges so it’s not visible. Push the capstones together and mortar the cracks in between. Brush off dried excess mortar with a stiff-bristle brush.

Mortared Garden Wall

The mortared stone wall is a classic that brings structure and appeal to any yard or garden. Square-hewn ashlar and bluestone are the easiest to build with, though fieldstone and rubble also work well and make attractive walls.

Because the mortar turns the wall into a monolithic structure that can crack and heave with a freeze-thaw cycle, a concrete footing is required for a mortared stone wall. To maintain strength in the wall, use the heaviest, thickest stones for the base of the wall and thinner, flatter stones for the cap.

As you plan the wall layout, install tie stones—stones that span the width of the wall (page 127)—about every 3 feet, staggered through the courses both vertically and horizontally throughout the wall. Use the squarest, flattest stones to build the “leads,” or ends of the wall first, and then fill the middle courses. Plan for joints around 1 inch thick and make sure joints in successive courses do not line up. Follow this rule of thumb: cover joints below with a full stone above; locate joints above over a full stone below.

Laying a mortared stone wall is labor-intensive but satisfying work. Make sure to work safely and enlist friends to help with the heavy lifting.

A mortared stone wall made from ashlar adds structure and classic appeal to your home landscape. Plan carefully and enlist help to ease the building process.

How to Build a Mortared Stone Wall

How to Build a Mortared Stone Wall

Pour a footing for the wall and allow it to cure for 1 week. Measure and mark the wall location so it is centered on the footing. Snap chalk lines along the length of the footing for both the front and the back faces of the wall. Lay out corners using the 3-4-5 right angle method (see page 140).

Dry-lay the entire first course. Starting with a tie stone at each end, arrange stones in two rows along the chalk lines with joints about 1" thick. Use smaller stones to fill the center of the wall. Use larger, heavier stones in the base and lower courses. Place additional tie stones approximately every 3 ft. Trim stones as needed.

Mix a stiff batch of Type N or Type S mortar, following the manufacturer’s directions. Starting at an end or corner, set aside some of the stone and brush off the foundation. Spread an even, 2" thick layer of mortar onto the foundation, about 1/2" from the chalk lines—the mortar will squeeze out a little.

Firmly press the first tie stone into the mortar so it is aligned with the chalk lines and relatively level. Tap the top of the stone with the handle of the trowel to set it. Continue to lay stones along each chalk line, working to the opposite end of the wall.

After installing the entire first course, fill voids along the center of the wall that are larger than 2" with smaller rubble. Fill the remaining spaces and joints with mortar, using the trowel.

As you work, rake the joints using a scrap of wood to a depth of 1/2"; raking joints highlights the stones rather than the mortared joints. After raking, use a whisk broom to even the mortar in the joints.

Drive stakes at the each end of the wall and align a mason’s line with the face of the wall. Use a line level to level the string at the height of the next course. Build up each end of the wall, called the “leads,” making sure to stagger the joints between courses. Check the leads with a 4-ft. level on each wall face to make sure it is plumb.

If heavy stones push out too much mortar, use wood wedges cut from scrap to hold the stone in place. Once the mortar sets up, remove the wedges and fill the voids with fresh mortar.

Fill the middle courses between the leads by first dry-laying stones for placement and then mortaring them in place. Install tie stones about every 3 ft., both vertically and horizontally, staggering their position in each course. Make sure joints in successive courses do not fall in alignment.

Install capstones by pressing flat stones that span the width of the wall into a mortar bed. Do not rake the joints, but clean off excess mortar with the trowel and clean excess mortar from the surface of the stones using a damp sponge.

Allow the wall to cure for one week and then clean it using a solution of 1 part muriatic acid and 10 parts water. Wet the wall using a garden hose, apply the acid solution, and then immediately rinse with plenty of clean, clear water. Always wear goggles, long sleeves and pants, and heavy rubber gloves when using acids.

Repairing Stone Walls

Damage to stonework is typically caused by frost heave, erosion or deterioration of mortar, or by stones that have worked out of place. Dry-stone walls are more susceptible to erosion and popping while mortared walls develop cracks that admit water, which can freeze and cause further damage.

Inspect stone structures once a year for signs of damage and deterioration. Replacing a stone or repointing crumbling mortar now will save you work in the long run.

A leaning stone column or wall probably suffers from erosion or foundation problems and can be dangerous if neglected. If you have the time, you can tear down and rebuild dry-laid structures, but mortared structures with excessive lean need professional help.

Stones in a wall can become dislodged due to soil settling, erosion, or seasonal freeze-thaw cycles. Make the necessary repairs before the problem migrates to other areas.

How to Rebuild a Dry-Stone Wall Section

How to Rebuild a Dry-Stone Wall Section

Study the wall and determine how much of it needs to be rebuilt. Plan to dismantle the wall in a V shape, centered on the damaged section. Number each stone and mark its orientation with chalk so you can rebuild it following the original design.

TIP: Photograph the wall, making sure the markings are visible.

Capstones are often set in a mortar bed atop the last course of stone. You may need to chip out the mortar with a maul and chisel to remove the capstones. Remove the marked stones, taking care to check the overall stability of the wall as you work.

Rebuild the wall, one course at a time, using replacement stones only when necessary. Start each course at the ends and work toward the center. On thick walls, set the face stones first, and then fill in the center with smaller stones. Check your work with a level and use a batter gauge to maintain the batter of the wall. If your capstones were mortared, re-lay them in fresh mortar. Wash off the chalk with water and a stiff-bristle brush.

Tips for Repairing Mortared Stone Walls

Tint mortar for repair work so it blends with the existing mortar. Mix several samples of mortar, adding a different amount of tint to each and allow them to dry thoroughly. Compare each sample to the old mortar and choose the closest match.

Use a mortar bag to restore weathered and damaged mortar joints over an entire structure. Remove loose mortar (see below) and clean all surfaces with a stiff-bristle brush and water. Dampen the joints before tuck-pointing and cover all of the joints, smoothing and brushing as necessary.

How to Repoint Mortar Joints

How to Repoint Mortar Joints

Carefully rake out cracked and crumbling mortar, stopping when you reach solid mortar. Remove loose mortar and debris with a stiff-bristle brush.

TIP: Rake the joints with a chisel and maul or make your own raking tool by placing an old screwdriver in a vise and bending the shaft about 45°.

Mix Type M mortar, and then dampen the repair surfaces with clean water. Working from the top down, pack mortar into the crevices using a pointing trowel. Smooth the mortar when it has set up enough to resist light finger pressure. Remove excess mortar with a stiff-bristle brush.

How to Replace a Mortared Stone Wall

How to Replace a Mortared Stone Wall

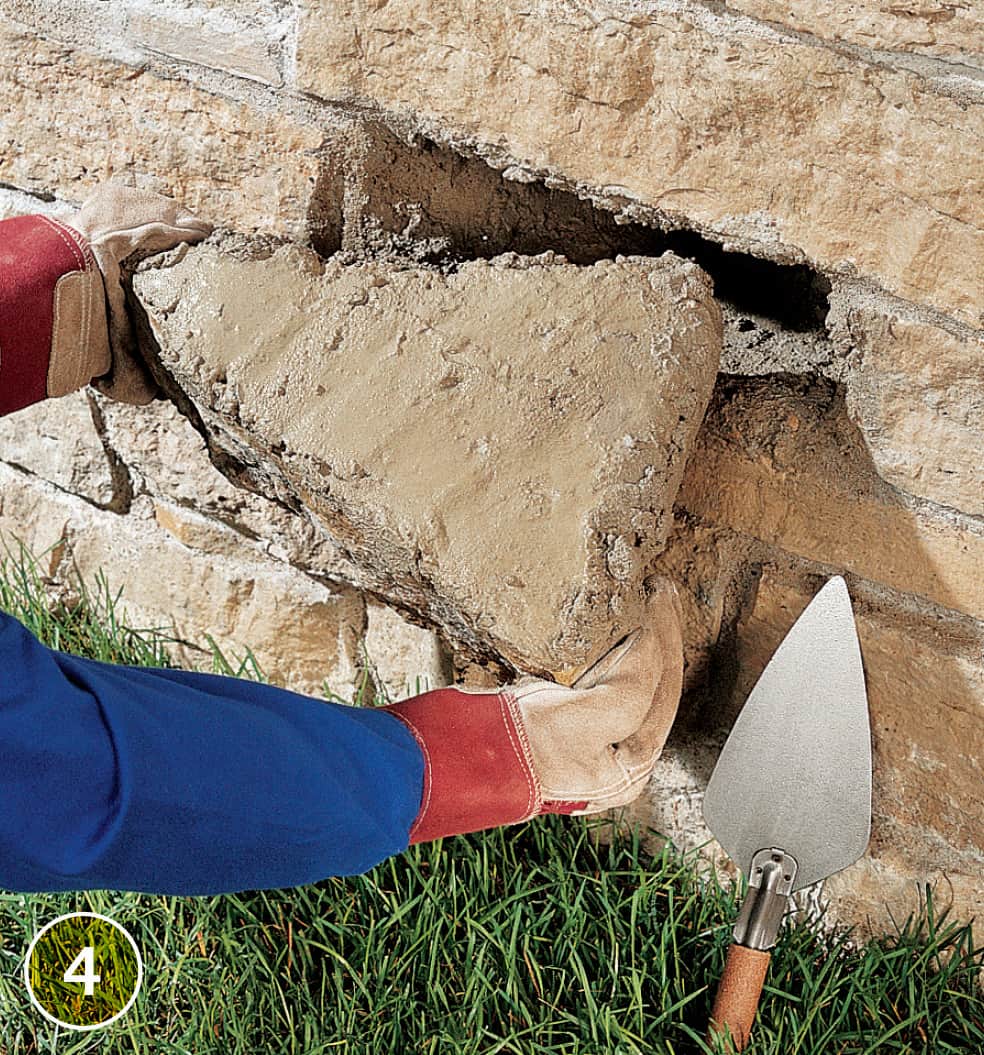

Remove the damaged stone by chiseling out the surrounding mortar using a masonry chisel or a modified screwdriver (opposite page). Drive the chisel toward the damaged stone to avoid harming neighboring stones. Once the stone is out, chisel the surfaces inside the cavity as smooth as possible.

Brush out the cavity to remove loose mortar and debris. Test the surrounding mortar and chisel or scrape out any mortar that isn’t firmly bonded.

Dry-fit the replacement stone. The stone should be stable in the cavity and blend with the rest of the wall. You can mark the stone with chalk and cut it to fit, but excessive cutting will result in a conspicuous repair.

Mist the stone and cavity lightly, and then apply Type M mortar around the inside of the cavity using a trowel. Butter all mating sides of the replacement stone. Insert the stone and wiggle it forcefully to remove any air pockets. Use a pointing trowel to pack the mortar solidly around the stone. Smooth the mortar when it has set up.

SLOPES & CURVES

SLOPES & CURVES

TOOLS & MATERIALS

TOOLS & MATERIALS

PREPARATION TIPS

PREPARATION TIPS