TO THE MOST SERENE PRINCESS ELISABETH, ELDEST DAUGHTER OF FREDERICK, KING OF BOHEMIA, COUNT PALATINE, AND ELECTOR OF THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE . . . And that this zeal is indeed in your Highness is obvious from the fact that neither the distractions of the court nor the customary upbringing which usually condemns girls to ignorance could prevent you from discovering all the liberal arts and all the sciences . . . And I personally have a greater proof of this, since I have so far found that only you understand perfectly all the treatises which I have published up to this time. For to most others, even to the most gifted and learned, my works seem very obscure.

René Descartes, Principles of Philosophy, 1644

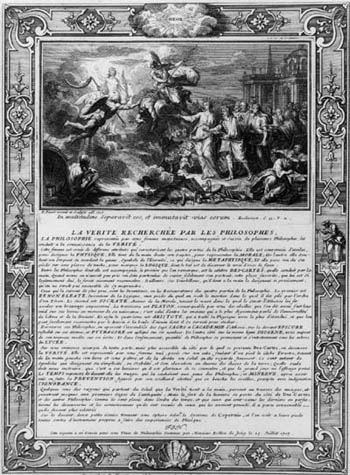

Descartes, reported his niece Catherine, was a close friend of Lady Philosophy. In the picture reproduced as Figure 13, Lady Philosophy, identifiable by her crown of stars (representing physics) and the coiled snake biting its own tail (metaphysics), leads Descartes by the hand towards the radiant goddess of Truth. In front of Truth, a helmeted Minerva aggressively fights down the monsters of Ignorance and Prejudice. Scientific instruments are piled up on the ground, and eminent Greek sages cluster behind Descartes, who can be recognised by his face, as well as from the sheet he is holding, which describes his physical theories – whirlpools of tiny particles that swarm through every nook and cranny of the universe.

This engraving has had a chequered history. It was originally designed in 1707 as the frontispiece for a doctoral dissertation, but a senior academic wrongly informed the Archbishop of Paris that it showed Aristotle wearing ass’s ears and being vanquished by the new Cartesian philosophy. Such flippancy was sacrilegious for conservative Catholics. They associated Descartes’s ideas with Protestant heresies, and suppressed the print. Some years later, it was published by an English plagiarist who removed all traces of Cartesian whirlpools and simply substituted Newton’s name for Descartes’s – scientific heroes are evidently interchangeable!1

Fig. 13 Truth sought after by the philosophers. Bernard Picart, La Vérité recherchée par les philosophes, 1707 (designed as the frontispiece for Thèse de philosophie soutenue par M. Brillon de Jouly, le 25 juillet, 1707).

This particular Lady Philosophy had a double identity. She was also Christina, Queen of Sweden, renowned throughout Europe for her learning. By her early twenties, Christina was already being celebrated as the Minerva of the North, and engravings circulated showing her in a laurel-wreathed helmet with an owl at her side. As part of her ambitious plans to reign over an intellectual European empire, she encouraged eminent scholars to join her circle. Like other monarchs, Christina used her wealth and position to affect the directions of academic research, and during her reign she tried to convert remote Stockholm into a metropolitan centre fit to rival Paris and London. In 1649, she invited Descartes to visit her court. Five months after he arrived, he was dead.2

Descartes died in Sweden in 1650: a neutral statement of facts about a death shrouded in rumours. Did Descartes succumb to cold and pneumonia, or was he poisoned to prevent him from converting the Lutheran queen to Catholicism? Perhaps, as Catherine Descartes suggested, Dame Nature was so angry at being stripped naked that she unleashed a torrent of poison to push him into the grave. And what has happened to his saintly relic, the right forefinger lovingly chopped off by the French Ambassador? And whose skull was added to his remains as they were shipped around Europe?3 Even his death has generated mysteries, so it is not surprising that his life has acquired a mythical aura. The traditional biographies resemble a philosophical fable . . .

Three women were important for René Descartes: his mother, who gave him life; Lady Philosophy, the bride to whom he pledged himself; and Christina of Sweden, who took his life away again. (Kitschy though this sentence deliberately sounds, it is a relatively prosaic version. Throughout the nineteenth century, Descartes’s biographers described a fourth woman – a mechanical life-sized doll, eerily resembling his illegitimate daughter, who accompanied him all over Europe as tangible evidence of his edict that animals are machines without souls.)4

During his twenties, Descartes travelled widely, although there are strange gaps when his whereabouts remain unknown. He was only twenty-five when a series of bizarre, half-waking dreams in an overheated room gave him his life’s mission: to rebuild the world of knowledge. Just as he had learned to conquer his nightmarish visions by the power of his own mind, so too, he claimed, rational thought would vanquish superstition and solve the mysteries of nature. Like demolishing an ancient rambling city, Descartes set out to undermine the foundations of learning and construct an entirely new system based on reason. In his revolutionary rational philosophy, ideas about the world would be underpinned by facts as certain as mathematical truths.

Descartes coined philosophy’s snappiest axiom: I think, therefore I am. I know that I exist, he argued, because I know that I think. Descartes split the universe into two. On one side lay matter – not only the physical world of rocks, skies and oceans, but also the human body. On the other lay God, the angels and human minds. This Cartesian mind-body separation leads to a tricky problem: how can our brains interact with our bodies? Even Descartes admitted to feeling pangs of hunger when he needed physical food to nourish his intellectual activities, and – despite introducing God and the pineal gland into his system – he never did explain how our thoughts can govern our actions, or conversely how our sensations can influence our decisions.

Nevertheless, Descartes has often been hailed as the father of modern philosophy. His distinction between the human spirit and material objects is fundamental to one type of scientific ideology: if an observer is distinct from his surroundings, then he can observe the external world objectively. This Cartesian detachment, which implies a superior vantage point, is now often said to be masculine, because Descartes’s harsh rational and mathematical approach encapsulates many of the characteristics that are attributed to men, and rejects qualities that are traditionally seen as feminine. His system overturned older organic cosmologies that regarded living beings as integral components of a harmonious universe, which bound people’s minds and souls tightly together with God as well as with the physical world. Another way of thinking about this shift is to look at art. Medieval pictures, with their multiple scenes that depict inner as well as outer experiences, seem distorted and incoherent to us. Renaissance artists introduced a strong perspectival structure, which assumes that a single spectator is looking from a fixed external viewpoint. These pictures are reassuringly familiar and realistic because we have become used to representing the world in a Cartesian way.5

But in the mid-seventeenth century, Descartes’s ideas were enormously controversial. For his English critics, Descartes epitomised the men of reason condemned by Bacon - not the wise bees, but the dogmatic spiders who spin webs from their own selves. His Catholicism posed further difficulties. Like Galileo, who was condemned by the Inquisition in 1634, Descartes taught that the sun, rather than the Earth, lay at the centre of our planetary system. Moreover, his concepts of matter contradicted the doctrine of transubstantiation (that consecrated bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ). Threatened with persecution, Descartes resumed his travels round Europe, moving from city to city as he became involved in a series of acrimonious disputes.

He eventually retreated to the Netherlands, taking with him only the scantiest of luggage – a Bible and a book by Aquinas. Isolated from the busy Parisian world, and lacking the financial and social support of a powerful patron, Descartes dedicated himself to a life of reflection. He was in his mid-forties when he published his philosophical masterpiece, the Meditations, an eloquent exposition based on those disturbing dreams that had launched him on his personal journey of discovery from doubt to certainty.

Buffeted by theological disputes and academic intrigues, Descartes found it impossible to turn down Queen Christina’s invitation to Stockholm. Using the French Ambassador as intermediary, she had been writing to him for more than two years, and he was obliged to accept this summons from an influential, wealthy patron who demanded to be taught the most modern philosophy. Brought up as a boy, Christina resembled an intellectual cavalryman. Indifferent to clothes, food and discomfort, she devoted herself to her favourite pursuits – horse-riding, politics and academic study. Surviving on only five hours’ sleep a night, Christina spurned female company and spent lavish sums to attract Europe’s finest scholars to her court.

Demanding similar dedication from her new tutor, Christina established a rigorous timetable: five hours of lessons three times a week, to start at five in the morning – the depth of night in winter so far to the north. This was a hard regime for the man who gained his greatest insights dozing in a hot room, especially when the winter turned out to be the worst for sixty years. Descartes loyally struggled on for a couple of weeks before falling ill. Suspiciously refusing treatment from an opponent’s doctor, he rapidly succumbed to delirious fever and the hostile climate, dying a victim of his patron’s harsh demands.

This traditional version combines several appealing elements – the impoverished, wandering scholar, his unjust persecution for clinging to the truth, and the seduction of the mysterious icy North. Such accounts also reiterate misogynistic stories of Eve as temptress. From her frozen retreat, wealthy Christina lures Descartes, siren-like, to his death. She is literally a femme fatale, the ice-queen so chillingly portrayed by Greta Garbo. But there was another woman in Descartes’s life – Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. Focusing on Princess Elisabeth rather than on Queen Christina enables a different tale to be told. This view of the past not only changes the roles of women, but also suggests another way of remembering Descartes.

Despite her central European title, Elisabeth (1618–80) was the granddaughter of Bacon’s witch-hunting James I and the aunt of England’s George I; moreover, she lived in the Netherlands until she was nearly thirty. Soon after she was born, her parents accepted the crown of Bohemia, a foolish decision that cost them their fortune and condemned the family to a life of poverty. That is, poverty by royal standards – according to a running family joke, they dined on diamonds and pearls, the children’s interpretation of pawning their inheritance.

Unlike her numerous brothers and sisters, Elisabeth was a sad, serious child, who resented her mother’s gay life after her father’s death. Seeking refuge in books, she was fluent in many languages. She was nicknamed ‘la Grecque’ for her knowledge of Greek and Latin, but she also spoke the international French of royal families, the English and German of her parents, and the Flemish of the local people. (She later read Descartes’s philosophy in the original Latin, translated English medical texts for him, and when she proposed that they study Machiavelli together, they both chose the Italian version.)6

It is hard to re-create the character and appearance of a princess, because all the contemporary letters and descriptions are couched in flowery, sycophantic language. Portraits are also unreliable witnesses – artists deliberately flattered their subjects, especially since profitable royal marriages were often confirmed on the basis of a picture rather than a meeting. Figure 14 shows a Dutch painting that is currently on display in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, where it hangs beneath a bearded Sophocles. It corroborates her younger sister Sophie’s description of her as a tall, slim woman with ‘black hair, a dazzling complexion, brown sparkling eyes, a well-shaped forehead, beautiful cherry lips . . .’ With a tasselled hunting spear clasped in her right hand, Elisabeth is portrayed as Diana, the stern and athletic personification of chastity. Luxurious yellow and red feathers droop from her hat, and the diagonal yellow sash and blue dress accentuate her figure. Evidently not all the family pearls were lost, since Elisabeth (and also later Sophie) is painted wearing a necklace.7

Fig. 14 Elisabeth of Bohemia. A portrait from the school of Gerrit van Honthorst.

However faithful it may be, this portrait gives no hint of Elisabeth’s embarrassment over her nose, which was long, thin and inclined to glow red. Like many talented young women, Elisabeth lacked confidence, and her sensitivity about her nose reinforced her timidity. Spurned by her mother, and mocked by the other children for her dreamy absent-mindedness, she peppered her letters with self-deprecating remarks about her appearance as well as her abilities. Elisabeth seems to have resigned herself to a studious life, recognising that impoverished, independent-minded princesses were not highly sought after as wives. Racked by anxieties about money and family, she was plagued by ill-health – lingering coughs, indigestion and many of the symptoms that we now associate with depression.

The winter of 1642: Elisabeth was twenty-four and Descartes was forty-six – almost twice her age, the same as her father would have been had he lived – when they met at one of her mother’s parties in The Hague. Picture the scene: shy Elisabeth feels obliged to converse with this famous guest and express her admiration for his work; reclusive Descartes, conscious of his ageing, may have noticed her on a previous visit, but now confronts for perhaps the first time in his life a young woman who is genuinely more interested in philosophy than fashion.

In principle, Descartes endorsed female education, even claiming that he had simplified some of his explanations about God so that women could understand them. Elisabeth needed no such condescending interpretations. Possibly it was love at first sight; certainly their protracted friendship was deeply emotional. ‘A body like those painters give to angels,’ Descartes enthused in his first letter to her; she made him feel as if he had just arrived in heaven, he gushed. Theirs was an asymmetrical relationship, yet far more complex than its obvious, simplistic description – Elisabeth the adoring yet critical pupil, Descartes the older man who appeared besotted, yet came to shun her physical presence.8

Gossip-mongers were soon spreading rumours about her boat trips along the Rhine to Descartes’s nearby home.9 Although he stripped philosophical thought to its bare essentials, Descartes was no ascetic hermit. He lived in a spacious country mansion surrounded by orchards, slept late and employed an excellent cook. Little is known either about her visits to him or about the reciprocal, but infrequent, calls he paid on her family. Their subsequent correspondence suggests that they discussed intellectual matters. Perhaps Descartes taught her mathematics and encouraged her to participate in the experimental research he was pursuing – dissections and chemical experiments. As to other activities, one can only speculate. The letters that remain were composed with such decorum that they yield no firm evidence of a sexual affair, yet they do reveal a heartfelt warmth and intimacy on both sides.

Suddenly Descartes was gone. In May 1643 he abandoned his comfortable home and moved away to a remote village in the marshes. Did he resent his academic visitors and critics from the city, or was he fleeing from Elisabeth? Later that month, he accepted her polite rebuke about his failure to meet her, pointing out that he was often tongue-tied in her presence.10 Although they rarely saw each other again, they regularly exchanged letters over the next seven years, right up to the time of his death in Sweden. Many of these letters survive – although there are tantalising gaps – and they reveal the extent to which Elisabeth influenced Descartes’s thought and writings. Descartes’s contemporaries thought his relationship with her was so important that in the first publication of his correspondence, his letters to Elisabeth were placed right at the beginning.11

Descartes was not the only scholar with whom Elisabeth conversed and corresponded, and at least two other writers dedicated their work to her. Her mother, the exiled queen, prided herself on her glittering intellectual circle, and other visitors included Margaret Cavendish’s brother-in-law, who had taught her natural philosophy. As in the Cavendish household (see Figure 4), Elisabeth could engage in dinner-table debates with guests along with Sophie, who was also interested in philosophy (she later chose Leibniz rather than Descartes as her correspondent). In particular, Elisabeth was friendly with Anna van Schurman, eleven years her senior, who lectured at Leiden University and boldly campaigned for female education. Carefully cultivating her international reputation as the Dutch Minerva, van Schurman engaged in debates with several famous men, including Descartes. Elisabeth may well have been inspired by her example, although philosophically they stood on opposing sides. Van Schurman disapproved of Descartes’s bids to revolutionise knowledge, and clung to older authorities – Aristotle and the Bible. The antagonism was mutual: Descartes broke off their relationship because he could not tolerate van Schurman’s insistence on studying the Bible in Hebrew.12

Even in liberal Holland, Descartes was perceived as a dangerous radical in the first half of the seventeenth century. His enemies accused him of overthrowing orthodox teaching, demoting the Earth and its occupants from their central spot in the universe, and disproving God’s existence. After his death, his writings were placed on the Catholic Index of Prohibited Books, and Cartesian philosophy was banned from French universities. The Cartesian, rational approach to the universe that lay at the heart of Enlightenment thought initially gained strength in the Netherlands, and only later spread to the rest of northern Europe. By choosing to ally herself with Descartes, Elisabeth was making a public declaration of her disagreement with conservative thinkers like van Schurman. Yet she maintained her own intellectual independence from Descartes – don’t believe, she reprimanded him, that I agree with you from prejudice or laziness.13

At first, their correspondence was conducted on a master–pupil basis, heavily laced with elaborate compliments on both sides. But Elisabeth nudged the relationship ahead, refusing to let Descartes adopt an entirely didactic role. To his surprise, she solved a difficult mathematical problem he sent her; perhaps her unexpected success acted as some sort of qualifying test, since the subsequent letters revolve around theological, philosophical and psychological issues. A staunch Protestant, she embarked on philosophical and theological exchanges with Descartes, a Catholic steeped in Jesuit principles. He felt stranded in a remote cultural desert, he told Elisabeth, and her searching enquiries were so unusual that it made him experience an extraordinary joy – he yearned to confess himself conquered.14

Descartes, the reserved scholar, confided in Elisabeth with unparalleled openness: his only extant reference to his mother appears in a letter to her. She reciprocated by consulting him about her most intimate experiences. Although, like many women, Elisabeth has left no systematic discussion of her ideas in a book, it is clear from her letters that she developed her own independent philosophy. Not afraid to criticise, she subjected Descartes’s ideas to intense scrutiny.

Descartes’s system sent women conflicting signals. His establishment of a detached, objective spectator reinforced his own superiority as the older, experienced philosopher. As a man, he wandered freely round Europe, while illness and convention confined Elisabeth to domestic self-observation. On the other hand, his emphasis on the power of an intellect detached from its body implies that a woman is just as capable of rational argument as a man. By the logic of his own philosophy, Elisabeth should be able to engage with Descartes as an equal. Her constant questions and criticisms forced Descartes to explain and also to modify his opinions, while her preoccupation with emotions, morality and her own health pushed Descartes in new intellectual directions.

The year after his abrupt departure, Descartes published his Principles of Philosophy, which he had been working on throughout the period he had known Elisabeth. Modern philosophers regard Descartes’s Meditations as his greatest work, yet Descartes himself saw it only as a preliminary to his Principles of Philosophy, which was intended to be a systematic exposition of his entire life’s thought.15 And he dedicated this major book to Elisabeth, a remarkable testament of his high esteem. Dedications were normally ingratiating attempts to flatter a patron, but this one was different. Despite her title, Elisabeth had no money, and Descartes deliberately avoided the excessively ornate language adopted by authors hoping for financial backing. Instead, he wrote a short but scholarly and eloquent disquisition on virtue. Elisabeth’s mind, he concluded, was unique: only she understood his ideas. Publicly declaring himself her ‘most devoted admirer’ who was captivated by her wisdom, majesty and gentleness, Descartes consecrated his book ‘to the Wisdom which I perceive in you (because my Philosophy itself is nothing other than the study of wisdom)’.16

For Descartes, this philosophy of wisdom was not restricted to abstract ideas, but embraced everything to do with daily life. For modern readers, his Principles of Philosophy looks far more like a book about science than philosophy. Studded with diagrams, it discusses topics like mechanics, astronomy and magnetism. Like Newton, Descartes drew no hard lines between science, philosophy and theology, and it was only towards the end of the eighteenth century that these subjects started to split apart into separate disciplines. Newton became celebrated as the world’s first scientist, while Descartes became the founding father of philosophy. By dividing up the scholarly territory, both England and France could boast their national heroes.

Three weeks after the Principles appeared, Elisabeth was ready to send Descartes her considered opinion. Naturally, she opened by professing herself unworthy of such an honour, declaring herself indebted to him for allowing her to share in his glory. The niceties over, she launched into some detailed criticisms, adopting a tactic that typifies her comments on his work. Unerringly placing her finger on a weak point, she disguised her acuity by claiming that the problem lay in her own weak intellect. ‘I’m afraid,’ ran the formula, ‘that you will, with justification, withdraw your opinion of my ability, when you learn that I don’t understand . . .’ And then in for the kill. Like the huntress of her portrait (see Figure 14), she fooled her victim into a sense of false security before she pounced. Descartes tried to wriggle out of tight corners. Yes, he agreed, I didn’t explain mercury’s weight very thoroughly because I hadn’t studied the metal properly, but my account was probably about right. The holes she picked in his magnetic theory, central showcase of Cartesian physics, were potentially even more threatening. After a few unconvincing sentences, he hastily drew the letter to a close: ‘I humbly beg Your Highness to forgive me, if I only write in great confusion. I haven’t got the book with me . . . and I’m constantly on the move.’17

Even in her very first letter, Elisabeth first elaborated her inferiority, and then rhetorically took advantage of this self-abasement to force Descartes into confronting his philosophical weaknesses. I’ve been hesitating to write, she told him, because I’m so ashamed of my disordered thoughts. But now I’ve plucked up my courage, she continued disingenuously, and I beg you to explain how a person’s soul, which consists only of thinking matter, can cause the body to move. Writing with feigned ignorance, she had immediately targeted the central lacuna in Descartes’s system. Only five days later he replied, graciously acknowledging the force of her criticism – your question is indeed, he admitted, the most sensible one to ask, and he set out to persuade her that his model worked.18

Elisabeth forced him to modify his earlier position. In her letters, she repeatedly prodded him, diplomatically masking her attacks as she pushed him further. Please excuse my stupidity, she protested with false naivety in her second letter, but your revised explanation still limps badly – you just haven’t convinced me that a purely spiritual soul can move a person’s body. You’re right, he apologised, I didn’t explain myself very well and I left some things out. And then he sketched out a new scheme incorporating a third mysterious substance that somehow unified the soul with the body. Descartes liked this philosophical sticking plaster so much that he included it in the Principles of Philosophy. But Elisabeth disagreed. Once again, she wrote, I’m embarrassed to send you further evidence of my ignorance, but . . . You yourself taught me about the importance of sceptical doubt, and I don’t see how this hypothetical third substance works. Silence. No response. Elisabeth had neatly used a Cartesian argument to foil Descartes himself, and he apparently didn’t like it (although, of course, the reply may have been lost).19

Wisdom, Descartes declared, included knowing how to stay healthy. Descartes the doctor is an unfamiliar figure, but he constantly dispensed medical advice to his friends, and informed the Duke of Newcastle (Margaret Cavendish’s husband) that ‘the preservation of health has always been the principal end of my studies’.20 Under Elisabeth’s influence, Descartes became increasingly interested in the links between mental and physical health, another aspect of the mind-body dualism so central to his system. At the outset of their correspondence, Elisabeth made Descartes swear the Hippocratic oath so that she could confide in him freely, and she sent him frequent reports on her condition. It seems to have been a gratifying arrangement for both parties: he provided a willing listener to her litany of complaints, while her gratitude and flattery led him to relish his role of paternal sage, the physician who would teach her how to cure her body with her soul. And when she was desperate, he obeyed her calls for help, travelling to her bedside to comfort her in person rather than through the mail.

Elisabeth was no passive recipient of Descartes’s ideas. Under her guidance, their mutual emotional self-indulgence prompted Descartes to ponder more deeply on how feelings can produce physical symptoms. Faced with remedying Elisabeth’s frailty, Descartes shifted his focus. Instead of worrying about the impact of health on psychological well-being and intellectual performance, he started to concentrate on using the mind to cure the body. Elisabeth taught him that she was burdened with a body that was ‘very easily affected by the afflictions of the soul’; his injunction to rise nobly above her sickness was not, she protested, helpful for someone whose spleen and lungs had already succumbed to the physical effects of melancholy. Worrying about Elisabeth’s indigestion led Descartes to agree: ‘the soul undoubtedly has a strong effect on the body, as can be seen from the great changes caused by anger, fear and other emotions’. Elisabeth’s outpourings induced him to formulate recipes for getting better: ‘When the mind is full of joy, that greatly helps the body to feel good.’ Before meeting Elisabeth, Descartes had prescribed medicine to make men wiser. Three years into their correspondence, he commented that the best way to live longer was to stop being afraid of death.21

Thought itself was therapeutic, advised Descartes. When Elisabeth plunged into a long period of decline in 1645, Descartes tried to rally her spirits. Ordinary people, he told her, succumb to their misfortunes, but superior beings – intellectuals like you and me, he meant – can make their reason overcome their emotions. Elisabeth’s protracted periods of illness and despair often corresponded to major upheavals in her life – her brother’s conversion to Catholicism, her own exile after being accused of inciting another brother to murder, and the beheading of her uncle, Charles I. Descartes may have been deeply sympathetic, but he did believe in the rational approach. Instead of conventional messages of consolation, he often sent cold analyses that read more like philosophical treatises. And this is, indeed, what they became. Descartes kept copies of his letters to Elisabeth, carefully filing them with other important documents. Their discussions formed the basis of his last book, Passions of the Soul, which explored – again – how the mind and the body interact.

A dose of Seneca, Descartes prescribed. No better way of restoring her spirits, he insisted, than studying the recommendations for happiness set out by this Roman Stoic. Without waiting for her acquiescence, a couple of weeks later he sent off a critique, the first in a series of letters rehearsing his arguments for his Passions of the Soul. Descartes was not simply analysing what Seneca had written. Instead, he was expounding what he thought Seneca should have said. Her opinion, he wrote, would both instruct him and help him to refine his commentary.

Elisabeth was not convinced by his interpretations. First came the self-demeaning flattery – please continue correcting Seneca, she begged, because your gifts of exposition make it all seem like common sense. Next were the reservations – however, I do have a small doubt . . . And then, straight to a fundamental problem. How can we reason our way to happiness, when so many misfortunes are beyond our control? If illness can take away our powers of thought, she asked, then how can the mind and body be completely distinct? And, she continued, since our health can influence our mental state, then the fact that I have a female body must surely affect how I think?22

Like Bacon, Descartes wanted to associate men with self-discipline and intellectual activity. Elisabeth undercut Descartes’s arguments by pointing to the weakness of her own body. At first sight her debating strategy might seem strange, because it apparently reinforces arguments of female inferiority. Surviving correspondence reveals that this question plagued several female philosophers of the period. They worried about their tendency to blush and weep, uncontrollable behaviour that seemed to confirm their sensitivity to inner passions. But by stressing this physical vulnerability, learned women could emphasise their superlative intellectual powers: how much cleverer they must be than their male peers, with such obstacles to overcome! Mary Evelyn, wife of the famous diarist, was described as ‘a great mistress of her passions’ – high praise, suggesting that, like a man, she could control her emotions and exert her powers of thought.23

Back and forth went the letters, right through the winter. Elisabeth relentlessly hammered away, pointing out contradictions and forcing Descartes to explain his ideas, to redefine his terminology and make it more precise. For instance, under her urging, he acknowledged and spelt out the distinction between an infinite God and an infinite universe. Some of their head-on confrontations stemmed from their opposing religions. Descartes had claimed to base his entire system on certainty, yet he soon reintroduced God as an irrefutable escape route from sticky positions. For Elisabeth, the question of free will remained a major obstacle. If God is omnipotent, she demanded, how can people perform evil deeds that destroy happiness? Again, she used a Cartesian argument against Descartes himself – since God lets us feel free, she declared, therefore we effectively are. His back against the wall, Descartes fell back on vague terms like ‘incomprehensible’, ‘of another nature’. In the end, he admitted, only faith can convince us of God’s powers.24

Unconvinced by Descartes’s attempts to explain how an immaterial soul might interact with a human body, Elisabeth defied him to define the passions. A few weeks later, in November 1645, he reported that he was still thinking how best to do this. The following spring, stimulated by their correspondence, he sent her a draught copy of the opening sections of his Passions of the Soul.25 Now ignored except by specialists, this was his last book, the culmination of his life’s thought. Advising Elisabeth how to make herself well provided the therapeutic basis of Descartes’s prescriptions for living a good life, one that is ethical as well as enjoyable. How to be good and feel good – the most important question philosophers can ask.

For Descartes and his contemporaries, sadness, anger and the other emotions belonged to medicine, because they were associated with physical conditions. But they were also central to moral philosophy, which – Descartes insisted – was the ultimate wisdom because it demanded knowing all the other sciences. By persuading Descartes to focus on her sickness, Elisabeth had not diverted him on to a side track away from philosophy. On the contrary, she goaded him into clarifying issues about the relationship between the mind, the body and God that were central to his whole system. Swayed by Elisabeth, Descartes placed a new emphasis on personal experience and observation, moving his arguments from the purely metaphysical to a more physical plane.26

A few months after this sequence of letters came to a close, Descartes and Elisabeth met for the last time. On 15 August 1646, Elisabeth reluctantly left for Berlin, banished by her mother during the scandal surrounding the assassination of a young Frenchman, who was rumoured to have seduced both her mother and her sister. Perhaps Descartes suspected that they might never meet again – was he secretly relieved that she was moving far away? Certainly the tone of their letters became more intimate and relaxed, slightly gossipy even.

This time it was Elisabeth who nominated the intellectual tonic to revive her spirits – not Seneca, but Machiavelli, an appropriate diet for a princess victimised by political intrigues. She reassured Descartes of her success in applying his rational medicine to dispel her depression, and even managed to joke about the catarrh-ridden pedantic brains of her acquaintances. Yet despite avoiding a visit, Descartes continued to worry about her. This concern for Elisabeth provides one explanation for his decision to seek the support of Queen Christina via his close friend Hector-Pierre Chanut, the French Ambassador to Sweden. Descartes had never looked for patronage before, and he probably hoped that he could enlist Christina’s protection for Elisabeth. As a first step, he sprinkled gratuitous flattering references to Elisabeth throughout his correspondence with Chanut. The lack of subtlety confirms his intentions: in his opening letter, without even pausing to start a new sentence, Descartes the ingratiating diplomat contrived to link the two women, praising their shared royalty that enabled them to ‘surpass by a long way the learning and virtue of other men’.27

After almost three years of negotiations, Descartes finally set off for Sweden, having unfortunately missed the warship that Christina had sent to collect this intellectual trophy. Within a couple of days of his arrival, Descartes was – at least, according to him – singing Elisabeth’s praises to Christina. Possibly attempting to boost Elisabeth’s hopes, he emphasised Christina’s generosity and virtue. Nevertheless, he confided, Christina seemed woefully ignorant of modern philosophy – he wasn’t sure whether she would be dedicated enough to tear herself away from her old-fashioned studies of classical philology. Descartes omitted to mention that the Greek tutor was thirty years younger than him, but his scantily concealed desire to make Elisabeth jealous by praising Christina suggests that emotional as well as intellectual rivalries were involved.28

Elisabeth replied with sarcastic dignity. Don’t think for an instant that your glowing description of Christina has made me jealous, she retorted. I’m happy to learn about such an accomplished woman, one who helps to remove the imputations of stupidity and weakness too often cast at women – although you do seem to have discovered even more marvels in the Queen than her reputation would suggest.

Elisabeth thanked Descartes for his kindness in bringing her to the Queen’s attention. I’m happy, however, she concluded pointedly, that your high regard for Christina won’t oblige you to remain in Sweden. Written more than two months before Descartes died, this letter must surely have reached him. But he didn’t reply.29

Descartes was buried in unconsecrated ground, exhumed seventeen years later, and is now in his third Parisian resting place. Apart, that is, from his skull and his forefinger, whose whereabouts remain uncertain. His reputation has fluctuated. Since Descartes himself believed that the most important thing in life is ‘to procure, as far as possible, the good of others’, he would presumably have wished to be remembered for the moral guidance that he composed under Elisabeth’s prompting. But this aspect of his work, together with his extensive research into optics, astronomy and many other scientific topics, is now forgotten. He is predominantly celebrated as a philosopher who dramatically altered the way we think, even though nobody agrees with him. As Voltaire put it: ‘He was wrong, but at least it was with method.’30

Christina continued to study classical texts and ancient philology, just as Descartes had feared. Five years later, she created an international scandal by converting to Catholicism and abdicating. Descartes–Christina myths developed in two directions. Descartes’s followers accused her of luring him to his death, even though there were other valid reasons for his journey to Sweden, including seeking patronage for Elisabeth. Reciprocally, Scandinavian critics blamed Descartes for his malign influence on Christina. Historians on both sides are trying to unravel these historical tales.31

Elisabeth immediately relinquished all hope of Swedish patronage. Judging from Chanut’s response, she must have sent him a curt note demanding the return of her letters – no copies to be made, she specified (unsurprisingly, she refused to change her mind when Chanut informed her that Christina would find them interesting). Elisabeth, then aged thirty-one, apparently never discussed Descartes’s death, but her relatives found her obvious depression hard to cope with. For the next seventeen years she lodged in a succession of family homes, coming to epitomise the unmarried and unwelcome older sister who can always be relied upon to help out at deaths and weddings. She then entered a Protestant convent, eventually becoming its head. At last this wandering princess achieved an identity of her own, ruling over a large household of aristocratic women and administering a territory of 7,000 people. Although she turned to religion rather than reason for consolation, she continued to discuss intellectual topics by letter. She corresponded with Leibniz, and also with philosophers interested in reconciling Christianity and Cartesianism. Provoking much scandal, she provided a refuge for her old friend and Descartes’s opponent, Anna Van Schurman, who was being vilified for her attachment to a heretical minister. Elisabeth’s sister Sophie reported that she calmly ordered her coffin, and then died like a guttering candle. A century later, her tomb was opened, and her silk robe crumbled to dust on contact with the air.32

Elisabeth may seem a solitary figure, but she was not a lone pioneer. She often encountered other scholars – women as well as men – and was bound in to the correspondence network stretching throughout Europe. In the middle of the eighteenth century, she was celebrated as the leader of a philosophical sect called the female Cartesians. Viewed in retrospect, these intellectual women formed an underground movement amongst Descartes’s followers who criticised Cartesian ideas from within. In principle, if human beings are defined by their reason, then their bodies are irrelevant. So for the female Cartesians, Descartes’s famous maxim I think, therefore I am could be converted into I think, therefore I am ungendered. However, this scattered, diverse group flourished only briefly, and female scholarship soon became suppressed in France. Ironically, Elisabeth and the other Cartesian women had helped to construct a masculine philosophy that came to exclude women. Using a new vocabulary, modern French feminists reiterate many of Elisabeth’s original arguments against Descartes. But they are caught in the same trap as her – how can you fight rationalist thought with rational weapons?33