More than any other Greek women, Spartans have been the subject of praise or blame from antiquity to the present. This excursus begins with a note of praise from a twentieth-century feminist, but the last quotation is a strongly worded condemnation from a Greek philosopher.

Simone de Beauvoir (1952, p. 82) idealized Sparta:

Since the oppression of woman has its cause in the will to perpetuate the family and to keep the patrimony intact, woman escapes complete dependency to the degree in which she escapes from the family; if a society that forbids private property also rejects the family, the lot of women in it is found to be considerably ameliorated. In Sparta the communal regime was in force, and it was the only Greek city in which woman was treated almost on an equality with man. The girls were raised like the boys; the wife was not confined in her husband’s domicile: indeed, he was allowed to visit her only furtively, by night; and his wife was so little his property that on eugenic grounds another man could demand union with her. The very idea of adultery disappeared when the patrimony disappeared; all children belonged in common to the city as a whole, and women were no longer jealously enslaved to one master; or, inversely, one may say that the citizen, possessing neither private wealth nor specific ancestry, was no longer in possession of woman. Women underwent the servitude of maternity as did men the servitude of war; but beyond the fulfilling of this civic duty, no restraint was put on their freedom.

As we have seen in Chapter 1, fragments of early Archaic poetry are our first important sources for Spartan women; hence we have chosen to discuss them here. Later texts and brief reports about Spartan women are also extant, but archaeological and art historical sources are few. Of our sources only Alcman, who was probably born in Lydia but lived in Sparta at the end of the seventh century B.C.E., is a direct witness for women in the Archaic period. Xenophon lived in Sparta in the first quarter of the fourth century B.C.E. Other authors who comment on Sparta are late, but they often drew their information from earlier (though not necessarily trustworthy) sources. For example, Plutarch, who gives detailed information about women based on research in earlier literature, lived approximately one thousand years after the so-called constitution of the legendary Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus, which he describes. This excursus will survey what is reported about the history of Spartan women spanning approximately a 500-year period.

Our sources refer to Sparta of the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods, in several cases without raising the possibility that life in Sparta changed over time. This telescoping of history is one reason why the texts contain contradictions that are difficult to explain and reconcile on the nature of Spartan marriage, the choice of spouses, and women’s relationship to real property. We have data about Spartan women who were upper-class and royal, not about the women of the lower classes. (The population of Sparta was distributed into three groups: the Spartiates [or Spartans] were full citizens; the periokoi were free, non-citizens; and the helots were unfree workers.) Both poetic and prose texts give information on the life cycle from childhood through puberty, sexuality (including lesbianism), marriage, motherhood, and death.

Alcman wrote choral lyrics that were performed by unmarried girls, and some fragments of these Partheneia still remain to offer glimpses of an all-female aristocratic world. (For longer excerpts of the poems from which the phrases below are quoted, see Chapter 1.) The beauty of Spartan women was legendary. Like the mythical Helen, the girls of Partheneion 1 are said to have had golden hair: “The tresses of my cousin Hagesichora blossom like pure gold.… She, with her gorgeous golden hair.” Cosmetics were banished, and were, in any case, not needed, for exercising outdoors made women’s complexions glow (“Her silvery face”). These handsome women, unsecluded, are named and their attractive features and accomplishments praised. The animal imagery used for them is complimentary: “Our glorious leader … who clearly stands out herself, as if you put among the herds a racehorse, sturdy, thundering, a champion.… The girl who’s next to Agido in beauty shall race but as a Kolaxeian horse behind an Ibenian.” Fine horses connote beauty and wealth, but, like the maidens who will be married, horses must be broken in or yoked.

The girls mentioned in Partheneion 1 seem to belong to at least two different age groups (see Chapter 1). The oldest are Hagesichora and Agido, who serve as models for the other girls, who are younger and who vie for their leaders’ attention. There is plenty of evidence for homoerotic friendships between men in many places and in all periods of Greek history. Plutarch describes the relationship of younger with older women in Sparta as sexual and educational and parallels it with the better-known relationship of boys with men:

Whether a boy’s standing was good or bad, his lover shared it.… Sexual relationships of this type were so highly valued that respectable women would in fact have love affairs with unmarried girls. Yet there was no rivalry; instead, if individual males found that their affections had the same object, they made this the foundation for mutual friendship, and eagerly pursued joint efforts to perfect their loved one’s character.

(Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 18; Talbert 1988: 30–31)

Some of Alcman’s language is explicitly erotic. Competent translators convey these sentiments in various ways. The following selection provides an example of one of the major problems confronting the reader who must encounter the ancient evidence through the lens of translation. The first quotation from Partheneion 1 is from the translation by Bing and Cohen (1991), which is quoted in full in Chapter 1:

and no longer coming to Ainesimbrota’s house will you say:

“if only Astaphis were mine,

if Philylla would look my way,

or Demareta, or lovely Vianthemis—

but Hagesichora wears me out with desire.”

In Charles Segal’s (1985: 174) version, the girls are more coy and elusive:

Nor if you go to the house of Anesimbrota will you say, “May Astaphis be mine; may Philylla cast her glances at me and Damareta and the lovely Vianthemis”; but rather you will say, “Hagesichora wears me down.”

Richmond Lattimore’s (1970) translations are usually close to the Greek, but in this passage he adopts euphemisms:

… nor go to Ainesimbrota’s

house and say:

Let Astaphis be on my side;

let Philylla look my way;

give me Damareta, lovely Ianthemis

… Maidens, we have come to the peace desired,

all through Hagesichora’s grace.

The Greek text itself is difficult to establish. David Campbell prefers an alternate version of the Greek (reading terei “guard” instead of teirei “wears out”).1 The possibility that the text refers to an intimate relationship between Hagesichora and other women is mentioned only in the commentary:

… nor will you go to Aenesimbrota’s and say, “If only Astaphis were mine, if only Philylla were to look my way and Damareta and lovely Ianthemis”; no, Hagesichora guards me.

(Campbell 1988: 367)

However, the erotic allusion is probably correct, for such language is not confined to Partheneion 1, but appears in other Partheneia:

A girl declares her erotic feelings toward Astymeloisa who may be the leader of a chorus: … and with desire that looses the limbs, but she looks glances more melting than sleep and death.… If she should come near and take me by the soft hand, at once I would become her suppliant.

(Partheneion 2, frag. 3; Segal 1985: 178. See full quotation in Chapter 1)

Spartans were the only Greek girls for whom the state prescribed a public education. This education included a significant physical component. In Partheneion I girls are praised for swiftness in the comparisons with racehorses. Spartan women were the only Greek women we know of who stripped for athletics, as Greek men did, and engaged in athletics on a regular basis. Some sources report that total nudity, even in public in the presence of men, was not unthinkable for Spartans, as it was for other respectable Greek women. Thus in Plato’s Republic, the proposal that women exercise in the nude is considered not only radical, but laughable. (See Chapter 3 “Ancient Critical Reactions to Women’s Roles in Classical Athens”.) When Spartan women participated in footraces at Olympia in honor of Hera, goddess of marriage, they wore a short chiton like those worn by the legendary Amazons (see Chapter 4):

Every fourth year the Sixteen Women weave a robe for Hera; and the same women also hold games called the Heraea. The games consist of a race between virgins. The virgins are not all of the same age; but the youngest run first, the next in age run next, and the eldest virgins run last of all. They run thus: their hair hangs down, they wear a shirt that reaches to a little above the knee, the right shoulder is bare to the breast. The course assigned to them for the contest is the Olympic stadium; but the course is shortened by about a sixth of the stadium. The winners receive crowns of olive and a share of the cow which is sacrificed to Hera; moreover they are allowed to dedicate statues of themselves with their names engraved on them. The attendants who help the Sixteen to run these games are women. As with the Olympic festival they trace back these girls’ games to antiquity, declaring that Hippodameia in gratitude to Hera for her marriage to Pelops established the Committee of Sixteen and with their help inaugurated the Heraean festival.

(Pausanias 5.16.2; Frazer 1965: 1: 260)

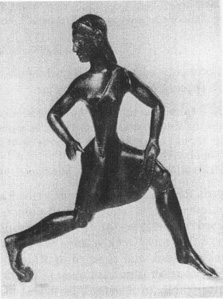

The image of a young athletic woman shown in seminudity (Fig. 2.1) is extraordinary in the context of Archaic Greece. Compared with the heavily draped korai from other parts of the Greek world, the seminude woman in this statuette seems striking, but it was meant neither as “heroic,” nor, as far as we can tell, erotic; rather it was a straightforword representation of the racing costume mentioned in the written texts. This statuette should be compared with the korai discussed in Chapter 1. (See further discussion of the female nude in Chapter 5.)

Figure 2.1. Statuette of a young female athlete shown in a short sleeveless dress, not unlike that of an Amazon. Such an image is unusual in the context of Archaic Greece, where female figures (other than prostitutes) are normally shown in layered garments that cover the whole body.

The naming of girls in the Partheneia and the fact that the names of victors in the footraces were inscribed on statues of themselves indicate that women were not excluded from the public sphere and suggest that some, at least, were literate. Women who participated in choirs that performed choral lyric certainly knew how to sing and dance and had memorized the myths and historical events narrated in the poems, for example those concerning the Pleiades mentioned in Partheneion 1. Unlike Athens, Sparta produced at least two female poets: their names are known, but their works are not extant. Athenaeus (13.600f.) refers to a poet named Megalostrata who was Alcman’s contemporary, and Aristophanes (Lysistrata 1237) mentions a poet called Cleitagora. Iamblichus (De Vita Pythagorica 189–94, 267, 269) names several Spartan women who became Pythagoreans (Poralla, 1985: 72, 79, 118), while Plato (Protagoras 342D) remarked on the intellectual culture of Spartan women: “there are not only men but women also who pride themselves on their education; and you can tell that what I say is true and that the Spartans have the best education in philosophy.” In view of the notorious lack of culture among Spartan men, it would appear that Spartan women were, in terms of their superior education, more like men in other Greek cities.

According to the reference to the “Sixteen Women” in the passage from Pausanias, quoted earlier, Spartans, like other Greek women, could weave. But Spartans were forbidden to engage in banausic, or money-making occupations: they gained their sustenance from the work of the lower classes on plots of land that were distributed to Spartans at birth, but which reverted to the community when they died. We do not know whether public land was allocated to female babies, or whether females were supported by the allocations made to men in their families. All male Spartans were educated to become warriors, and the women’s principal task was to give birth to warriors. Xenophon draws attention to the eugenic goals of Spartan marriage and to elements in the education of Spartan women that were different from the experiences of Athenians:

For it was not by imitating other states, but by devising a system utterly different from that of most others, that he [Lycurgus] made his country preeminently prosperous.

First, to begin at the beginning, I will take the begetting of children. In other states the girls who are destined to become mothers and are brought up in the approved fashion, live on the very plainest fare, with a most meager allowance of delicacies. Wine is either withheld altogether, or, if allowed them, is diluted with water. The rest of the Greeks expect their girls to imitate the sedentary life that is typical of handicraftsmen—to keep quiet and do wool-work. How, then, is it to be expected that women so brought up will bear fine children?

But Lycurgus thought the labor of slave women sufficient to supply clothing. He believed motherhood to be the most important function of freeborn women. Therefore, in the first place, he insisted on physical training for the female no less than for the male sex: moreover, he instituted races and trials of strength for women competitors as for men, believing that if both parents are strong they produce more vigorous offspring.

He noticed, too, that, during the time immediately succeeding marriage, it was usual elsewhere for the husband to have unlimited intercourse with his wife. The rule that he adopted was the opposite of this: for he laid it down that the husband should be ashamed to be seen entering his wife’s room or leaving it. With this restriction on intercourse the desire of the one for the other must necessarily be increased, and their offspring was bound to be more vigorous than if they were surfeited with one another. In addition to this, he withdrew from men the right to take a wife whenever they chose, and insisted on their marrying in the prime of their manhood, believing that this too promoted the production of fine children. It might happen, however, that an old man had a young wife; and he observed that old men keep a very jealous watch over their young wives. To meet these cases he instituted an entirely different system by requiring the elderly husband to introduce into his house some man whose physical and moral qualities he admired, in order to beget children. On the other hand, in case a man did not want to cohabit with his wife and nevertheless desired children of whom he could be proud, he made it lawful for him to choose a woman who was the mother of a fine family and of high birth, and if he obtained her husband’s consent, to make her the mother of his children.

He gave his sanction to many similar arrangements. For the wives want to take charge of two households, and the husbands want to get brothers for their sons, brothers who are members of the family and share in its influence, but claim no part of the money.

Thus his regulations with regard to the begetting of children were in sharp contrast with those of other states.

(Constitution of the Lacedaemonians 1.2–10; Marchant 1984, 137–41)

Plutarch doubtless read Xenophon’s description of Spartan society. His version agrees with Xenophon’s: for example, both report with approval that girls were given a physical education and that newly married couples did not sleep together frequently. (For the education of girls at Athens, see Chapter 3, excerpt from Xenophon, Oeconomicus.) But Plutarch adds some curious antiquarian details about the transvestism of brides and a communal way of life for men that endured after marriage:

Aristotle claims wrongly that he (that is, Lycurgus) tried to discipline the women but gave up when he could not control the considerable degree of license and power attained by women because of their husbands’ frequent campaigning. At these times the men were forced to leave them in full charge, and consequently they used to dance attendance on them to an improper extent and call them their Ladyships. Lycurgus, rather, showed all possible concern for them too. First he toughened the girls physically by making them run and wrestle and throw the discus and javelin. Thereby their children in embryo would make a strong start in strong bodies and would develop better, while the women themselves would also bear their pregnancies with vigor and would meet the challenge of childbirth in a successful, relaxed way. He did away with prudery, sheltered upbringing, and effeminacy of any kind. He made young girls no less than young men grow used to walking nude in processions, as well as to dancing and singing at certain festivals with the young men present and looking on. On some occasions the girls would make fun of each of the young men, helpfully criticizing their mistakes. On other occasions they would rehearse in song the praises which they had composed about those meriting them, so that they filled the youngsters with a great sense of ambition and rivalry….

There was nothing disreputable about the girls’ nudity. It was altogether modest, and there was no hint of immorality. Instead it encouraged simple habits and an enthusiasm for physical fitness, as well as giving the female sex a taste of masculine gallantry, since it too was granted equal participation in both excellence and ambition. As a result the women came to talk as well as to think in the way that Leonidas’ wife Gorgo2 is said to have done. For when some woman, evidently a foreigner, said to her: “You Laconian women are the only ones who can rule men,” she replied: “That is because we are the only ones who give birth to men.”

There were then also these inducements to marry. I mean the processions of girls, and the nudity, and the competitions which the young men watched, attracted by a compulsion not of an intellectual type, but (as Plato says) a sexual one. In addition Lycurgus placed a certain civil disability on those who did not marry, for they were excluded from the spectacle of the Gymnopaediae….3

The custom was to capture women for marriage—not when they were slight or immature, but when they were in their prime and ripe for it. The so-called ‘bridesmaid’ took charge of the captured girl. She first shaved her hair to the scalp, then dressed her in a man’s cloak and sandals, and laid her down alone on a mattress in the dark. The bridegroom—who was not drunk and thus not impotent, but was sober as always—first had dinner in the messes, then would slip in, undo her belt, lift her and carry her to the bed. After spending only a short time with her, he would depart discreetly so as to sleep wherever he usually did along with the other young men. And this continued to be his practice thereafter: while spending the days with his contemporaries, and going to sleep with them, he would warily visit his bride in secret, ashamed and apprehensive in case someone in the house might notice him. His bride at the same time devised schemes and helped to plan how they might meet each other unobserved at suitable moments. It was not just for a short period that young men would do this, but for long enough that some might even have children before they saw their own wives in daylight. Such intercourse was not only an exercise in self-control and moderation, but also meant that partners were fertile physically, always fresh for love, and ready for intercourse rather than being sated and pale from unrestricted sexual activity. Moreover some lingering glow of desire and affection was always left in both….

What was thus practiced in the interests of breeding and of the state was at that time so far removed from the laxity for which the women later became notorious, that there was absolutely no notion of adultery among them.

(Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, 14–15; Talbert 1988: 24–26)

It is important to read such descriptions in the light of the authors’ desire to contrast Sparta with their own societies. In Athenian thought, Spartan women served as the “Other” vis-à-vis Athenian women. For example, Spartan women spent their time out-of-doors and spoke freely to men; Athenians ideally stayed indoors and scarcely spoke to their husband. (See further, Chapter 3.) Therefore, writers exaggerated the differences between them. Like Amazons (see Chapter 4), Spartans were also exploited as a means of praising or blaming the women in an author’s own state or women in general. Some ancient commentators considered that Sparta, when ordered by the Lycurgan constitution, had been a utopia. Thus some of the provisions in Plato’s ideal Republic resemble those ascribed to the archaic constitution of Lycurgus. (See Chapter 3, “Ancient Critical Reactions to Women’s Role in Classical Athens.”) Xenophon and Plutarch praised and criticized the treatment of women and women’s influence in Spartan society.

Included in the works of Plutarch are a collection of quotations purported to be the words of Spartan women, most of whom are undatable. They are consistent with the report in the Life of Lycurgus and other sources quoted earlier in showing that wit (not silence) was attributed to women; they were not “laconic.” The quotations also indicate that some women, at least, subscribed to the Spartan ideal that encouraged men to be brave in war. Cowardice, for example abandoning one’s shield and running from the battle, was not tolerated. Unlike most other Greek women, Spartans refused to lament over men who died in war (cf. Chapters 1 and 3). Rather, they took pride in the bravery of their sons:

After hearing that her son was a coward and unworthy of her, Damatria killed him when he made his appearance. This is the epigram about her:

Damatrius who broke the laws was killed by his mother,

She a Spartan lady, he a Spartan youth.

Another [Spartan] woman, when her sons fled from a battle and reached her, said, “In making your escape, vile slaves, where is it you’ve come to? Or do you plan to creep back in here where you emerged from?” At this she pulled up her clothes and exposed her belly to them.

A woman, when she saw her son approaching, asked how their country was doing. When he said: “All the men are dead,” she picked up a tile, threw it at him and killed him, saying: “Then did they send you to bring us the bad news?”

As a woman was burying her son, a worthless old crone came up to her and said, “You poor woman, what a misfortune!” “No, by the two gods, a piece of good fortune,” she replied, “because I bore him so that he might die for Sparta, and that is what has happened, as I wished.”

When an Ionian woman was priding herself on one of the tapestries she had made (which was indeed of great value), a Spartan woman showed off her four most dutiful sons and said they were the kind of thing a noble and good woman ought to produce and should boast of them and take pride in them.

Another woman, as she was handing her son his shield and giving him some encouragement, said, “Son, either with this or on this.”

(Plutarch, Sayings of Spartan Women 240–41; Talbert 1988: 159–61)

“Spartan” in English connotes asceticism and self-denial. According to Plutarch, under the Lycurgan constitution, this definition applied to the women as well as the men. But in the fourth century B.C. and the Hellenistic period some Spartan women were extremely wealthy and were conspicuous consumers. For example, Spartan women were the first women to own racehorses that were victorious at Panhellenic festivals. Like wealthy male owners, they did not themselves participate in the race, but employed charioteers (for other women who owned racehorses see Chapter 5).

Inscription recording one of the Olympic victories (in 396 and 392 B.C.E) of the horses of Cynisca:

My father and brothers were kings of Sparta.

I, Cynisca, victorious with my chariot of fleet horses,

erected this statue. I declare that I am the only woman

in all of Greece, who has won this crown.

(Inscriptiones Graecae 5.1.1564a;

Moretti 1953: p. 40, no. 17)

Sparta’s power declined in the fourth century, and Aristotle and other commentators felt that the distribution of wealth among women was at least partly responsible. As we have seen, Plutarch quotes Aristotle and agrees with him in pointing out that a man’s continual absence in military service, eating and sleeping in the barracks with his fellow soldiers, and going away for lengthy campaigns, affected family relationships and women’s status. He asserts that the men of Sparta obeyed their wives and allowed them to intervene in public affairs more than they intervened in private ones (Agis 7.3) But Plutarch, who was a Neoplatonist and who was optimistic about women’s moral and intellectual potential, rejected Aristotle’s conclusion that women were responsible in large part for the decline of Sparta. Aristotle viewed Sparta as a gynaiko-kratia (that is, a state ruled by women), and as such, contrary to the natural hierarchy in which men were to rule women. (See excerpts from Aristotle in Chapter 3, “Ancient Critical Reactions to Women’s Roles in Classical Athens.”) In Athens and some other Greek states women were not permitted to own land or to manage substantial amounts of wealth. Aristotle also criticized the Spartan system of land-tenure, which permitted women to own land and to manage their own property:

Again, the license of the Spartan women hinders the attainment of the aims of the constitution and the realization of the good of the people. For just as a husband and a wife are each a part of every family, so may the city be regarded as about equally divided between men and women; consequently in all cities where the condition of women is bad, one half of the city must be regarded as not having proper legislation. And this is exactly what happened in Sparta. There, the lawgiver who had intended to make the entire population strong in character has accomplished his aims with regard to the men, but has neglected the women, who indulge in every kind of luxury and intemperance. A natural consequence of this lifestyle is that wealth is highly valued, particularly in societies where men come to be dominated by their wives, as is the case with many military and warlike peoples, if we except the Celts and a few other races who openly approve of male lovers. In fact, there seems to be some rational justification for the myth of the union of Ares with Aphrodite, since all military peoples are prone to sexual activities with either men or women. This was evident among the Spartans in the days of their supremacy, when much was managed by women. But what is the difference between women ruling, or rulers being ruled by women? The result is the same. Courage is a quality of little use in daily life, but necessary in war, and yet even here the influence of the Spartan women has been negative. This was revealed during the Theban invasion of Laconia4 when the women of Sparta, instead of being of some use like women in other cities, caused more confusion than the enemy. It is not surprising, however, that the license of the women was characteristic of Spartan society from the earliest times, for the men of Sparta were away from home for long periods of time as they fought first against the Argives and then against the Arcadians and Messenians. When they returned to a peaceful life, having grown accustomed to obedience by military discipline, which has its virtue, they were prepared to submit themselves to the legislation of Lycurgus. But when Lycurgus attempted to subject women to his laws they resisted and he gave up, as tradition says. These, then, are the causes of what happened and thus it is clear that the constitutional shortcoming under discussion must be assigned to them. Our task, however, is not to praise or blame, but to discover what is right or wrong, and the position of women in Sparta, as we have already noted, not only contravenes the spirit of the constitution but contributes greatly to the existing avarice. This problem of greed naturally invites an attack on the lack of equality among the Spartans with regard to the ownership of property, for we see that some of them have very small properties while others have very large ones, and that as a result a few people possess most of the land. Here again is another shortcoming in their constitution; for although the lawgiver rightly disapproved of the selling and buying of estates, he permitted anyone who so desired to transfer land through gifts or bequests, with the same result. And nearly two-fifths of all the land is in the possession of women, due to the fact that heiresses are numerous the customary dowries are large. The regulation of dowries by the state would have been a better measure, abolishing them entirely or making them, at any rate, small or moderate.

(Aristotle, Politics 2.6.5–11 [1269b-1270a];

Spyridakis and Nystrom 1988: 183–84)

The difficulties we face in evaluating the status of women in antiquity are nowhere more compelling than in the case of Sparta. Objectivity has eluded both ancient and modern commentators who have picked through the conflicting fragments of ancient evidence to select “facts” that corroborate their views. Their opinions vary according to their conceptions about “the good life” within “the properly governed state.” According to legends associated with the Lycurgan constitution, Sparta, like Plato’s Republic, was a totalitarian state, where the totality of life was subject to regulation and supervision: neither protection of private property nor freedom of the individual were matters for concern. But, as we have seen, Aristotle, with the advantage of hindsight, criticized Sparta’s failure to curtail women’s freedom and to regulate women’s ownership of private property. In contrast, a feminist like Simone de Beauvoir, focusing on traditions about communal property and the amelioration of women’s lot, might prefer it to Classical Athens.

1. Malcolm Davies (p. 26, line 77) reads teirei.

2. Born in 506 B.C.E.

3. The festival of the naked boys, or boys without armor.

4. Under Epaminondas in 369 B.C.E.

Bing, Peter, and Rip Cohen. 1991. Games of Venus. New York.

Campbell, David A. 1988. Greek Lyric. Vol. 2. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Davies, M. 1991. Poetarum Melicorum Graecorum Fragmenta. Vol. 1 Oxford.

Frazer, J. G. 1965. Pausanias’s Description of Greece, New York (originally published 1898).

Lattimore, Richmond. 1970. Greek Lyrics. Chicago and London (originally published 1955).

Marchant, E. C. and G. W. Bowersock, 1968. Xenophon VII. Scripta Minora. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass. (originally published in 1925 without supplement).

Moretti, L. 1953. Iscrizioni Agonistische Greche. Rome.

Segal, Charles. 1985. “Archaic Choral Lyric: Alcman.” In The Cambridge History of Classical Literature, vol. 1, Greek Literature, edited by P. E. Easterling and B. M. W. Knox, Cambridge, 168–85.

Spyridakis, Stylianos V., and Bradley P. Nystrom. 1988. Ancient Greece: Documentary Perspectives. Dubuque, Ind.

Talbert, Richard. 1988. Plutarch on Sparta. London.

Beauvoir, Simone de. 1952. The Second Sex. New York. (Originally published as Le Deuxième Sexe, Paris, 1949)

Poralla, Paul. 1985. A Prosopography of Lacedaemonians. 2d edition by Alfred S. Bradford. Chicago.

Calame, Claude. 1977. Les choeurs de jeunes filles en Grèce archaïque. Vols. I and II. Rome.

Kunstler, Barton Lee. 1987. “Family Dynamics and Female Power in Ancient Sparta.” In Rescuing Creusa, edited by Marilyn B. Skinner, 31–48 [Also published in Helios, n.s. 13, no. 2: 31–48.]

Mossé, Claude. 1991. “Women in the Spartan Revolutions of the Third Century B.C.” In Women’s History and Ancient History, edited by Sarah B. Pomeroy, 138–53. Chapel Hill, N.C.

Page, Denys L. 1951. Alcman. The Partheneion. Oxford.

Scanlon, Thomas F. 1988. “Virgineum Gymnasium. Spartan Females and Early Greek Athletics.” In The Archaeology of the Olympics, edited by W. Raschke, 185–216. Madison, Wis.