Corinthian women, I have come out of the house

lest you criticize me for anything. For many people

I Know have become proud, some out of the public eye,

others openly. Private people, however,

get a bad reputation for inactivity.

For there is no justice in mortal eyes

when someone suffering no wrong hates a person

at first sight before he has understood his temperament.

A foreigner above all must adapt to the city, but

I would not even approve a person who offends

his fellow citizens out of pride and insensitivity.

Yet on me this disaster has fallen unexpectedly

and broken my heart. I am done for, my friends,

and giving up all joy in life, I wish to die.

My whole life was bound up in him, as he well knows;

yet my husband has proved to be the worst of men.

Of all beings who breathe and have intelligence,

we women are the most miserable creatures.

First we have to buy a husband at a steep price,

then take a master for our bodies.

This second evil is worse than the first, but

the greatest struggle turns on whether we get a bad

husband or a good one. Divorce is not respectable

for a woman and she cannot deny her husband.

Confronting new customs and rules,

she needs to be a prophet, unless she has learned

at home how best to manage her bedmate.

If we work things out well and the husband

lives with us without resisting his yoke,

life is enviable. Otherwise it is better to die.

A man, when he is tired of being with those inside

goes out and relieves his heart of boredom,

or turns to some friend or contemporary.

But we have to look to one person only.

They say we have a life secure from danger

living at home, while they wield their spears in battle.

They are mistaken! I would rather stand three

times beside a shield than give birth once.

(Euripides, Medea 214–51. [431 B.C.E.];

trans. Helene P. Foley)

Every respectable woman in classical Athens (ca. 480–323 B.C.E.) became a wife if she could; not to marry, as Medea argues, provided no real alternative. In this passage, Euripides’ Medea has come out from seclusion in her house to express to the women of Corinth her pain over her husband Jason’s betrayal. Medea has maintained the modesty and retirement appropriate to the life of a proper Athenian wife, who should, at least ideally, have spent most of her time indoors unless she were participating in religious events. She also does not want other women to think her proud, when they come to offer their sympathy. For, as the tragic heroine Iphigeneia says in another play by Euripides, voicing a view about female solidarity standard in drama (Euripides, Iphigeneia Among the Taurians, 1061–62, ca. 414–410 B.C.E.):

We are women, a tribe sympathetic to each other

and most reliable in preserving our common interests.

Medea is a foreigner in Corinth. She helped Jason win the Golden Fleece after she fell in love with him in her native Colchis and fled with him to Greece. Now he is leaving her to marry the only child of the King of Corinth. Yet her complaints about marriage are not alien to the Greek chorus. A woman, Medea complains, must buy an unknown husband with a dowry; every bride lives the life of a foreigner in her new home; husbands can escape from the house if the marriage goes badly, but wives cannot. They are dependent on one person, for whose sake they must undertake the pains and risks of childbirth.

This passage raises central questions about the lives of women in Classical Athens. How secluded was the proper wife’s existence? How much was she able to escape the confines of her house for the supportive companionship of other women? To what degree could she expect help and legal protection from her society when mistreated? Did Athenian wives fear or resent being married off young (early teens) to a considerably older husband (late twenties or above) whom they (in contrast to Medea) did not choose or know before the wedding?

Drama is a problematic source for the lives of both women and men in Classical Athens (see further Foley 1981, Zeitlin 1985, Just 1989, Des Bouvrie 1990). Classical tragedies and comedies generally are based on myths from the remote past or (in the case of comedy) fantastic invented scenarios. The plays may simply represent what male poets (and, on stage, male actors) imagined about women, or used them to imagine. Some have argued, for example, that Medea’s speech is Euripides’ clever reply to the objections contemporary Sophists made to marriage as an institution that curtailed male freedom, not a serious response to women’s plight. We are not even certain that women were present at the theater festivals in honor of the god Dionysus to see these plays (although there is evidence on both sides, it seems more likely that some women did do so); and no female voice has survived to give us a hint of a woman’s perspective in her own words. At the same time, the vivid portraits of women in drama—often more assertive, articulate, or rebellious than those we have from sources that claim to represent historical reality more directly—may have reflected real social and historical issues and tensions, even if in a somewhat indirect fashion.

We know, for example, that Medea exaggerates somewhat in this speech. Although divorce was easy to obtain, Athenian women at least (if not the foreigner Medea), were legally and financially protected in such cases. Their dowry had to be returned with them and court cases repeatedly cite male responsibility for the welfare of female relatives (see Demosthenes [Dem.] 30.21; the eponymous archon oversaw the welfare of orphans, widows, and pregnant widows), even if we know that some guardians failed to carry out that responsibility (for example, the abuse of Demosthenes’ mother by her guardian [Dem. 27 and 28]. See also Isaeus 8.36, Aeschines 1.95–99, Andocides 1.124–27, and Dem. 48.54–55). Among the upper classes at least, marriage patterns in Athens became increasingly endogamous, and husbands may not always have been complete strangers to their wives, or the move to a new household such a radical transition. Citizen wives visited with neighbors and participated frequently in religious events, sometimes in the company of other women, and sometimes at large civic festivals; thus, a wife’s existence may not have been so restricted as Medea suggests. Nevertheless, Medea is not the only tragic wife to criticize her lot, and passages in other plays emphasize in different ways the difficulties that both the transition to marriage and a wife’s subsequent isolation presented for her.

Procne in Sophocles’ Tereus asserts that the transition to marriage was a shock after the girl’s carefree childhood:

Now outside [my father’s house] I am nothing. Yet I have often

observed woman’s nature in this regard,

how we are nothing. When we are young in our father’s house,

I think we live the sweetest life of all humankind;

for ignorance always brings children up delightfully.

But when we have reached maturity and can understand,

we are thrust out and sold

away from the gods of our fathers and our parents,

some to foreigners, some to barbarians,

some to joyless houses, some full of reproach.

And finally, once a single night has united us,

we have to praise our lot and pretend that all is well.

(Frag. 524N [583R]. [early 420s B.C.E.?]; trans. Helene P. Foley)

Clytemnestra (at Aeschylus’ Agamemnon 855ff.) gives a lengthy speech about the tortures women experience when their husbands are at war, and in Sophocles’ Women of Trachis the heroine Dejaneira expresses anxiety over the frequent absences of her husband:

Chosen partner for the bed of Heracles,

I nurse fear after fear, always worrying

over him. I have a constant relay of troubles;

some each night dispells—each night brings others on.

We have had children now, whom he sees at times,

like a farmer working an outlying field,

who sees it only when he sows and when he reaps.

This has been his life, that only brings him home

to send him out again, to serve some man or other.

(Women of Trachis, 27–35 [ca. 420s B.C.E.];

Jameson 1959)

Such passages probably do not simply represent poetic fantasies. Women did react to the absence and death of their men at war; a woman’s husband was often absent. The historian Herodotus reports that once, after a disastrous Athenian raid on Aegina, the new widows took out their brooches and stabbed to death the one male survivor. Each woman asked as she stabbed where her own husband was. The Athenians then changed the style of women’s dress so that in the future they would not need brooches (5.87). Furthermore, agricultural work and civic and military duties took husbands out of the house for extended periods. Popular culture in Athens emphasized the desirability of a man’s dedication to the interests of the city-state and to work outside the house. Xenophon, in the Oeconomicus, a treatise on household management, for example, argues for a strict division of labor by sex: the husband’s role is to take care of what is outside the house and the wife’s to care for what is inside; once he has trained his wife to perform her job properly, he can leave her in charge of her own sphere (7.17ff.; see further under “Domestic Activities” in this chapter).

Euripides’ Phaedra, who has had the misfortune to fall in love with her stepson, Hippolytus, and is struggling to resist her passion, also shows how difficult a wife’s life might be. Surrounded by suspicion (see also Euripides, Ion 398–400), with too little opportunity for achievement and too much time to brood and fantasize, the wife may find it difficult to adhere to the moral principles that she had been raised to accept. Phaedra wishes to preserve the reputation of herself (and, she later adds, her children), but she finds it impossible to distract herself from her sufferings. Even the company of other women only makes virtue more difficult to attain (see also Euripides, Andromache 943–53).

Many a time in night’s long empty spaces

I have pondered on the causes of a life’s shipwreck.

I think that our lives are worse than the mind’s quality

would warrant. There are many who know virtue.

We know the good, we apprehend it clearly.

But we can’t bring it to achievement. Some

are betrayed by their own laziness, and others

value some other pleasure above virtue.

There are many pleasures in a woman’s life—

long gossiping talks and leisure, that sweet curse.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

It would always be my choice

to have my virtues known and honored. So

when I do wrong I could not endure to see

a circle of condemning witnesses.

I know what I have done: I know the scandal:

and all too well I know that I am a woman,

object of hate to all.

(Euripides, Hippolytus, 375–84, 403–7 [428 B.C.E.];

Grene 1959)

And indeed, she seems to be partially correct in her fears, for when Hippolytus hears (against her will) of Phaedra’s passion he pours out a tirade against women: he wishes that children could be acquired in other ways, since women are an economic drain, dangerous when clever, and prone to adultery (616ff.). This speech provokes Phaedra to take action, for she is afraid that Hippolytus will inform her husband Theseus. She commits suicide, leaving behind a tablet that claims that Hippolytus tried to rape her. It is hard to tell whether such plays confirm the popular fears about women and the need to supervise their behavior closely, or whether they attack the cultural confinement of women as dangerous in itself, or both.

Although drama generally represented potential problems and crises in life, it could also reflect or even exaggerate popular ideology about the normal role of women. Legally, wives in Athens were not permitted to make important social and financial decisions without the supervision of a guardian, and Aristotle argues in his Politics that the virtue of a wife consists in her obeying her morally superior husband (see especially, 1252a-b, 1254b). Some wives on the Greek stage, unlike Medea, actually revel in subordinating themselves to their husband’s needs and wishes, as popular culture thought that they should. Alcestis, who agreed to die in her husband’s stead, was a mythical ideal. (For the embarrassing consequences this sacrifice could have for her husband Admetus, see Euripides’ Alcestis. For representations of Alcestis as a marital ideal in art, see Fig. 3.15 and Chapter 13). In the passage below, Euripides’ Andromache, former wife of the dead Trojan hero Hector and now concubine to Achilles’ son Neoptolemus, tries to persuade his wife Hermione to defer consistently to her husband. The rich young Spartan Hermione, the spoiled darling of her parents Menelaus and Helen, has been trying to manipulate her husband and to get rid of his concubine and her child, since she is childless; she turns to her father whenever she is in trouble.

Your husband does not despise you on account of my drugs,

but because you are not fit to live with.

That’s my magic charm. It is not beauty, my good woman,

but virtues that keep our husbands happy.

When you get annoyed at something, Sparta’s the big deal

in your mind and Skyros counts for nothing.

You are a have among have nots. For you Menelaos

is greater than Achilles! This is why your husband hates you.

A woman must be content, even when married off

to a poor husband, and not fight over family resources with him.

If you had a husband who ruled in snowbound Thrace,

where one man shares his bed with many women

in rotation, would you kill them all? You’d be caught

tainting all women with your own incontinence.

How shameful! Though admittedly we’ve got a worse

case of this disease than men, even if we conceal it well.

Dearest Hector, for your sake I assisted in your love affairs

when Aphrodite tripped you up and many times

I nursed your bastards at my breast,

rather than betray some bitterness toward you.

With such virtuous conduct I won my husband’s

approval. But you, you’re even afraid to let

a drop of rain fall on your husband.

(Euripides, Andromache 205–28 [ca. 419 B.C.E.];

trans. Helene P. Foley)

The passage suggests that a wealthy wife might use her family position and her dowry as leverage against her husband. When Xenophon in the Oeconomicus proposes that a couple would do best to treat the wife’s dowry as joint property (7.13), he also seems to hint that it could, in less ideal circumstances, become a bone of contention. Furthermore, since a Greek wife was only “lent” in marriage to her husband’s family for the purpose of producing legitimate heirs, that family continued to have some stake in her future and could potentially reappropriate her to serve their own needs (see later under “Silenced Women” in this chapter).

It should be noted in considering Andromache’s advice that men could and did have concubines in Athens. If the women were not Athenians, their children were not Athenian citizens after Pericles’ citizenship law of 451–450 B.C.E. which defined as legitimate the children of two Athenian citizens. The foreign Medea in the passage quoted at the beginning of this chapter has been rejected in favor of a Corinthian wife, who could give Jason a socially advantageous marriage and children. The famous statesman Pericles, however, divorced his wife and took up with the foreign hetaira, Aspasia; in defiance of his own law, he eventually had his child by her declared legitimate after the death of his children by his first wife. Isaeus 6 demonstrates the problems that could arise when a husband allegedly adopted the children of his mistress, whom he preferred to his wife, and tried to make them his legitimate heirs.

Although, as was said above, there are many cases where male poets invented fantastic female characters to argue out difficult social conflicts and create women who act in ways not permitted to them in life, these striking pictures of the complex problems of a wife’s existence seem to express genuine contradictions in her role, if only in the male imagination. As we shall see, Classical Athenian sources consistently give us conflicting views on women (for a general discussion of interpretive issues, see Pomeroy 1975, Gould 1980, Blok 1987, and Just 1989). And virtually all of those sources, with the exclusion of archaeology, are tendentious. Historians’ views are constrained by their conception of what events are worthy to be recorded. Thucydides rarely mentions women in his history of the Peloponnesian Wars, for he writes about political and military events from which women were largely excluded. The anthropologically oriented Herodotus, on the other hand, considers both family and public life worthy of his investigations. The second-century C.E. historian Plutarch (whose sources are often early) was particularly interested in the status of women in the various societies that he discusses. Rhetoricians and orators—we rely on the law court speeches of Lysias, Demosthenes, Isaeus, and others here—shape their testimony to convince an audience of their cause, and philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, and Xenophon generally argue for and refine social ideals, rather than attempt to reflect the status quo. The fine arts may idealize, fantasize, or romanticize, and it is often hard to draw the line between depictions of life and representations of myth or even between wives, slaves, and prostitutes in Attic vase paintings (Williams 1983). Yet if we take all of these sources together, Classical Athens seems to have attempted, far more strictly than in Archaic Greece, to define both legally and informally the relation of the family and the individual to the state and of private life to public life. These changes affected the relations between men and women and may well have created the kinds of tensions that we have seen in the dramatic representations of distressed wives quoted earlier.

The Athenian democracy was a “men’s club” whose active members were restricted to men descended from parents who were both Athenian citizens. After Pericles’ citizenship law of 451–450 B.C.E., citizen women were carefully distinguished from those who were not, such as slaves, and residents of foreign descent, for the purpose of determining the citizenship of their children; but female citizens did not participate in governing the democracy. Indeed, before the Hellenistic period women were excluded from government and the military throughout Greece. Yet, unlike the laws attributed to Lycurgus at Sparta, which prescribed a public system of education for women, the laws attributed to Solon in sixth-century Athens were largely restrictive and may have aimed to reduce outward manifestations of inequality among men, as well as to strengthen the individual oikos (family, household, or estate) and to control family life. Under oligarchic, aristocratic, or monarchic governments, some women belonged to the ruling elite and wielded informal power such as we saw in the Homeric poems of the Archaic age. Since most of the population had no political rights, the possession of such rights did not pointedly distinguish men from women. The attempt by democratic Athens to buttress the equality of all its male citizens and to give them substantial responsibilities in the public sphere apparently, except in the case of religion, increasingly relegated to the private sphere all other free Athenians, whether women or resident aliens (free men or women protected by Athenian law but not entitled to the privileges of male citizens). (See further Just 1989: 22–23.) Solon’s laws affecting women seem to have been designed for a number of purposes. One important function was to ensure the preservation of individual households and provide them with legitimate heirs.

That law, too, seems absurd and ridiculous, which permits an heiress, in case the man under whose power and authority she is placed by law is himself unable to consort with her, to be married by one of his next of kin. Some, however, say that this was a wise provision against those who are unable to perform the duties of a husband, and yet, for the sake of their property marry heiresses, and so under cover of law, do violence to nature. For when they see that the heiress can consort with whomever she pleases, they will either desist from such a marriage, or make it to their shame, and be punished for their avarice and insolence. It is a wise provision, too, that an heiress may not choose her consort at large, but from the kinsmen of her husband, that her offspring may be of his family and lineage.

(Solon 20.2)

Still further, no man is allowed to sell a daughter or a sister, unless he finds that she is no longer a virgin.

(Solon 23.2; Perrin 1982)

Law-court cases from the fourth century B.C.E. in Athens still reflect tensions over which relatives should be permitted to marry an heiress (epikleros; see further under “Silenced Women” in this chapter).

Another purpose of Solon’s legislation was to curb women’s informal influence on their husbands.

On the other hand, he did not permit all manner of gifts without restriction or restraint, but only those which were not made under the influence of sickness, or drugs, or imprisonment, or when a man was the victim of compulsion or yielded to the persuasion of his wife. He thought, very rightly and properly, that being persuaded into wrong was no better than being forced into it, and he placed deceit and compulsion, gratification and affliction, in one and the same category, believing that both were alike able to pervert a man’s reason.

(Solon 21.3; Perrin 1982)

Isaeus 6 is one of a number of court cases presenting the idea that the whole political system is threatened if an individual man’s reason is undermined by a woman’s influence: “the woman who destroyed Euctemon’s reason and laid hold of so much property is so insolent, that… she shows her contempt not only for the members of Euctemon’s family, but also for the whole city” (6.48; see also Demosthenes 46.14, Isaeus 2.19).

Solon’s laws were also intended to control public appearances of women, including their expression of private emotion in public (for Solon’s laws curbing such behavior, especially in the context of funerals, see Chapter 1).

Mourning

In some cases, it seems certain that Solon’s laws prevented women from acting as they had earlier. As has already been shown in Chapter 1, Solon’s legislation on funerals prescribed that only close kin could mourn for the dead, thus prohibiting the ostentatious practice among the aristocracy of hiring women mourners and denying older women a source of income. Nevertheless, sources indicate that funerary legislation continued to be passed at Athens in the three centuries after Solon, and there is both archaeological (the shifting degree of ostentation in funerary monuments, discussed further below) and literary evidence that the regulation of women’s role in lamenting the dead and of funerary practices in general continued to be a disputed issue (see further, Humphreys 1983, Loraux 1986, and Foley 1993). Drama, for example, continued to represent women who resist the limited role permitted to them and/or persist heroically in carrying out the special responsibilities to dead kin that their culture assigned to them. The most famous case is Sophocles’ Antigone. After the battle at Thebes for succession between her brothers Eteocles and Polyneices, her uncle Creon pronounces an edict that bans burial for the traitor Polyneices, who attacked his own city. Antigone defies the edict and publicly embarrasses her uncle. Particularly chagrined to be challenged by a woman, Creon moves quickly to silence the voice of his niece. In the end, Antigone’s championing of the rights of the dead receives divine support. The prophet Tiresias tells Creon that the gods are offended by the pollution from the corpse. Creon must bury Polyneices and rescue Antigone from the cave in which he has imprisoned her to die. Too late, Creon finds Antigone dead and his son Haimon, Antigone’s fiance, kills himself over her body. In her first confrontation with Creon, Antigone offers the following defense of her disobedience to the edict:

For me it was not Zeus who made this proclamation.

Nor did Justice dwelling with the gods below

define such laws for humankind.

I did not think your orders had such power

that you, a mortal, could outrun

the gods’ unwritten and unfailing rules.

Not merely of today or yesterday, they live

forever, and no one knows from where they came.

For their sake I was not about to pay a penalty

to the gods, fearing the will of any man.

I knew that I would die; how could I fail to know,

even if you had not decreed it? If I die

before my time, I call this death a gain.

When someone lives with many sorrows

as I do, how could dying be unprofitable?

For me to meet this fate is thus a trivial grief.

But if I had permitted my mother’s dead son

to remain an unburied corpse, I would

have grieved at that; at this I do not grieve.

Now if I seem to have played the fool,

perhaps it is a fool who charges me with folly.

(Sophocles, Antigone 450–70 [ca. 442–41 B.C.E.];

trans. Helene P. Foley)

Similarly, in Euripides’ Suppliants, the mothers of the seven champions who attacked Thebes come to Athens for help. Thebes has refused to allow their sons to be buried. The mothers expect to acquire the right to mourn their sons extravagantly in public. Instead, Theseus appropriates the bodies of the slain from them. He has Adrastus, the surviving leader of the champions, pronounce a public funeral oration, and then takes the bodies away for cremation. The mothers remain to the end of the play eager to embrace the remains of their sons; but they are not even permitted to hold the urns containing their ashes. Theseus excuses his actions in a fashion that serves to justify Athens’ own contemporary restriction of women’s public lamentation of the dead:

ADRASTUS: Sorrowful mothers! Draw near your children!

THESEUS: Adrastus! That was not well said.

ADRASTUS: Why? Must parents not touch their children?

THESEUS: To see their state would be mortal pain.

ADRASTUS: Yes, corpse wounds and blood are a bitter sight.

THESEUS: Then why would you increase the women’s woe?

ADRASTUS: I yield.

(lines 941–47 [420s B.C.E.]; Jones 1959)

Such passages raise interesting questions. Funeral orations and funerary legislation recommended or required curtailment of public grief. Tragedy and other sources represent contradictory views on women’s public expression of emotion. In Aeschylus’s Seven Against Thebes, for example, the hero Eteocles first encounters the chorus of young women praying excitedly to statues of the gods and bringing them offerings in the hope of acquiring their protection from the enemy encamped outside Thebes’ walls. Eteocles views their activities as disastrous to the effort of the Theban warriors to defend their city. Plutarch even argues that women’s mourning for the god Adonis, a religious rite discussed later in this chapter, threatened the war effort during the Peloponnesian Wars: “the women were celebrating … the festival of Adonis, and in many places throughout the city little images of the god were laid out for burial, and funeral rites were held about them, with wailing cries of women, so that those who cared anything for such matters were distressed, and feared lest all that powerful armament, with all the splendor and vigour that were so manifest in it, should speedily wither away and come to naught” (Nicias 13, Perrin 1982).

Similarly, Athenian democracy celebrated its war dead and did not wish grief to undermine its heroizing of the dead and the dedication of its soldiers to the interests of the state. Plutarch also tells us that when Pericles returned to Athens after subduing Samos and delivered a funeral oration in 440 B.C.E., many of the women crowned him with garlands. But Elpinice, the sister of Cimon, one of the few women of Athens to have a (dubious) reputation of her own (see Plutarch, Cimon 4.5–7), reportedly came up to him and said.

“This was a noble action, Pericles, and you deserve all these garlands for it. You have thrown away the lives of these brave citizens of ours, not in a war against the Persians or the Phoenicians, such has my brother Cimon fought, but in destroying a Greek city which is one of our allies.” Pericles listened to her words unmoved, so it is said, and only smiled and quoted to her Archilochus’s verse, “Why lavish perfumes on a head that’s grey?”

(Plutarch, Pericles 28. Scott-Kilvert 1960)

In a fashion traditional to Athens’s archaic past, the aristocratic Elpinice wielded political influence for and through her brother Cimon (even long after his death, as here), for whom she twice interceded with Pericles; her advanced age may also explain the liberties she feels free to take here. Pericles, as a representative of the new ideology of Athens, dismisses her speech and her claims to authority.

Like the words of the elderly Elpinice, women’s lamentations also potentially challenged the war effort, because they stressed the consequences of death for the survivors. Yet when male characters in tragedy imagine their own deaths, they hope for burial, care after death, and lamentations from the women of their family (for example, Orestes in Euripides’ Iphigeneia Among the Taurians, 700–705). And what if a man died in a private context or a whole country became exhausted by war and its rhetoric, as may have happened during the long (431–404 B.C.E.) Peloponnesian Wars between Sparta and Athens? The families of such men may have resented the absence of a public opportunity to display grief over private deaths (the reemergence of ostentation in private grave monuments during the last quarter of the fifth century may also indicate resistance to funerary legislation curtailing such display). The overall dramatic contexts in which the actions of Antigone or Theseus occur suggest (although this case cannot be made here) that poets may be expressing ambivalence about the state control of burial practice and the suppression of women’s lamenting voices in the public arena of Athens. We know that women continued to have an important informal influence on private funerals, for the speaker of Isaeus 8.21–22 claims that, although he had been planning to conduct his grandfather’s funeral from his own house, he acceded to the wishes of his grandmother, who wished to lay out and deck the corpse, to conduct it from the house of the deceased.

Silenced Women

Advice to the parents of the dead was a traditional feature of public funeral orations, and Pericles urged those couples who were physically capable to produce more children. Exploiting the traditional view that young women who lacked male supervision and a male relative to conduct transactions that required meeting men were in danger of losing their respectability, Pericles offers to war widows a warning unique in extant funeral orations:

If I also must say something about a wife’s virtue to those of you who will now be widows, I will state it in a brief exhortation. Your reputation is glorious if you do not prove inferior to your own nature and if there is the least possible talk about you among men, whether in praise or blame.

(Thucydides 2.45.2, 431 B.C.E.)

In contrast to the public praise and blame of women in the Archaic period, poets, law-court speeches, and philosophers all express the view that respectable women (wives, mothers, daughters, sisters, and other close female relatives of the speakers) should remain silent or subdued in public and avoid being discussed by men. Orators avoid naming living respectable women unless they wish to cast a slur on their names (Schaps 1977). Not only women’s names, but women themselves were supposed to keep out of public view, with the important exception of their appearances at funerals and festivals as various cults and rituals required. “A woman who travels outside the house must be of such an age, that onlookers might ask, not whose wife she is, but whose mother.” (Hyperides, frag. 205 Jensen; Golden 1990: 122). Thus in vase painting, respectable women are rarely portrayed out-of-doors, except at festivals or in cemeteries and wedding processions.1 At Lysias 3.6, the speaker claims that his sister and nieces had lived in the women’s quarters with so much concern for their modesty that they were embarrassed even to be seen by their male relatives (see also Demosthenes 47, Isaeus 3.13–14, Lysias 1.22–23):

Hearing that the boy was at my house, he came there at night in a drunken state, broke down the doors, and entered the women’s rooms: within were my sister and my nieces, whose lives have been so well-ordered that they are ashamed even to be seen by their kinsmen. This man, then, carried insolence to such a pitch that he refused to go away until the people who appeared on the spot, and those who accompanied him, feeling it a monstrous thing that he should intrude on young girls and orphans, drove him out by force.

(first quarter of the fourth century B.C.E.; Lamb 1960)

Lycurgus (Against Leocrates 40) tells us that after the battle of Chaeronea in 338 B.C.E. free women stood in their doorways to ask from passersby news of their relatives, thus behaving in a fashion “unworthy of themselves and of the city.” Only courtesans went to parties with men, opened the front door themselves, or spoke to passersby in the street (see Isaeus 3.13–14 and Theophrastus, Characters 28.) This anonymity protected women from contact with men who were not family members, but it also makes it extremely difficult to study the history of Athenian women. In court cases, for example, speakers often found it hard to document the lives of respectable women. Laws governing the inheritance of property were not strictly agnatic (exclusive to the male line), but males preceded females in the right to inherit and relationships traced through males took precedence over those through females. Women were sufficiently obscure that it was possible to contest a rival’s claim to an inheritance by arguing that his mother had not been a legitimate child of her father or that his mother had not been a lawful wife of his father but had been a hetaira or concubine. In the following speech of 375 B.C.E. a grandson claims a large inheritance from his mother’s father, who was named Ciron. Endogamous marriage was common among the upper class. Ciron’s first wife was his cousin; she gave birth to one daughter who became the speaker’s mother. The speaker bases his claim on the presumption that if his mother had lived she would have been an epiklêros (heiress or, literally, “attached to the estate” of her father) when Ciron died, since there was no son to inherit the estate. In families where the surviving children were female, the estate of the father passed through such daughters to their sons. (See the laws of Solon quoted earlier in this chapter.) Wealthy heiresses were likely to be claimed in marriage by their next of kin (who would have inherited the property if the heiresses were not alive), even if they were already married. (See Isaeus 3.64–67.) Although according to law, children were members of their father’s family and remained with them after the death of their father just as they would have stayed with their father in case of divorce, the speaker argues that his mother and her offspring retained ties to Ciron:

As was natural, seeing that we were the sons of his own daughter, he [that is, Ciron] never performed a sacrifice without us, but whether the occasion was trivial or important, we were always at his side, taking part with him in the ceremony.… The conduct of our father and the knowledge that the married women of the district had of our mother shows that she was Ciron’s legitimate daughter. When he married her, our father celebrated a marriage feast with his relatives and three friends and presented the marriage sacrifice to the members of his tribe in accordance with their laws. Later, his wife was selected, along with the wife of Diocles of Pitthos, by the women of the district to preside at the Thesmophoria and to carry out the customary rites with her colleagues. When we were born he introduced us to his tribe with the usual oath that we were born of an Athenian woman legally betrothed.

(Isaeus 8.15–19 [383–363 B.C.E.]; trans. Sarah B. Pomeroy)

Here the speakers find it necessary to prove that their mother was Ciron’s legitimate daughter, and they make their case not only by citing Ciron’s actions, but by referring to the activities of the women of the district.

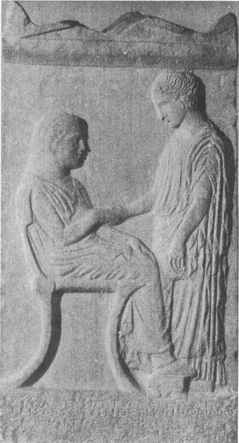

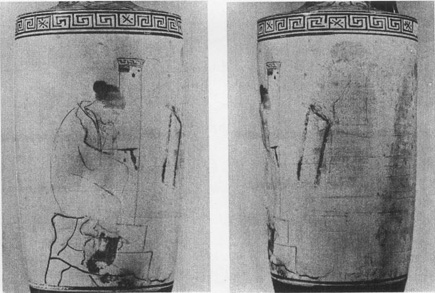

Named Women

Inscriptional evidence is exceptional in naming and even celebrating individual citizen women. An inscription on a black-figure vase of the fifth century B.C.E. celebrates the victory of a girl named Melosa in a girl’s carding (wool-working) contest (Attic, fifth-century B.C.E. Friedländer/Hofleit 1948: p. 165 177m). Priestesses (unlike other respectable women) are named in a number of religious contexts (see below), and after she died, a woman’s name might be inscribed on her tombstone along with the names of her closest male relatives (see Mnesarete’s stele in the Introduction to Part I). The genealogy of some women can be established in this way. For example, her mother and father set up the tombstone of a little girl named Aristylla (Fig. 3.1), who died about 430–425 B.C.E., perhaps in the plague that ravaged Athens in the early years of the Peloponnesian War. A brief epigram gives the names of her parents, Ariston and Rhodilla. Aristylla stands before her mother, their hands clasped. The handshake is a common motif on Athenian gravestones, symbolizing both the leave-taking of the dead who must journey to the Underworld and the union of family members that continues even in death. Arystilla’s tender age is indicated by her close-cropped hair and the small bird she holds in her left hand, a favorite plaything of young girls. Her mother Rhodilla is characterized as a proper Athenian matron by her backed chair with footstool, the mantle draped over her legs, and the veil pulled up over her head.

Figure 3.1. Tombstone of Aristylla (ca. 430–425 B.C.E.) shows the dead girl taking the hand of her mother. The meditative character of the image is typical of funerary imagery of the period, the wakes with mourners tearing their hair have largely disappeared from the art of the fifth century.

The woman commemorated by another gravestone was named Pausimache (Fig. 3.2). The epigram carved just above her head reads:

Figure 3.2. Tombstone of Pausimache (ca. 390–380 B.C.E.), who holds a mirror and whose inscription speaks of her goodness and good sense.

It is fated that all who live must die; and you, Pausimache, left behind pitiful grief as a possession for your ancestors, your mother Phainippe and your father Pausanias. Here stands a memorial of your goodness and good sense for passers by to see.

(Clairmont 1970: No. 13, p. 77)

Pausimache probably died unmarried, since no husband or children are mentioned. She is shown gazing into a mirror, not a symbol of vanity as in Renaissance art, but of the beauty and grace admired in Greek women. The mirror may also have a more specific reference, to the wedding of which Pausimache has been deprived by her early death, for brides are often shown holding a mirror as they prepare for the ceremony.

Often, when the inscription on the tombstone is metrical the woman alone is named, but without the addition of the names of male relatives she could not be identified, either by strangers who were her contemporaries or by later historians. An epigram on a relief from the Athenian port of Piraeus from the beginning of the fourth century B.C.E. is typical in emphasizing the dead woman’s decorum and productivity:

The memory of your virtue, Theophile, will never die

Self-controlled, good, and industrious, possessing every virtue.

(Peek 1955: 1490)

Despite the attempt to regulate women’s public activity and reputation, women in classical Athens legitimately appeared in public contexts when they engaged in ritual activities. Women’s participation in civic cults and their role as religious officials often represented a significant opportunity to contribute, at least symbolically, to the welfare of the city-state as a whole. The Athenian state religion, with its many cults, festivals, and rituals, was an integral part of everyday life, and women participated as much as men. Women of all social positions, both native Athenians and foreigners, worshiped together, though some cults and rituals were restricted to a more limited group, such as married women (possibly including concubines) at the Thesmophoria. These rituals apparently helped to mark and facilitate a girl’s transition to marriage and motherhood, to celebrate her role as weaver, and to harness women’s reproductive powers to promote the fertility of the entire society.

From early childhood, girls took part in religious rituals. Aristophanes mentions three activities in which groups of girls of the same age participated.2 Some of these activities were probably similar to those of Spartan girls. (See Chapter 2 discussion of Alcman, Partheneia.) Girls wove, ground grain, carried burdens, and danced in ritual contexts (choruses of girls danced at the Greater Panathenaia and perhaps at other festivals). In this passage the girl is probably meant to be understood as grinding grain and carrying figs (a symbol of fertility) for Athena:

Once I was seven I became an arrephoros.

Then at ten I became a grain grinder for the goddess (lit. the Archegetis or “first leader”).

After that, wearing a saffron robe, I was a bear at Brauron.

And as a lovely young girl I once served as a basket bearer, wearing a string of figs.

(Aristophanes, Lysistrata 641–47 [412 B.C.E.]; trans. Helene P. Foley)

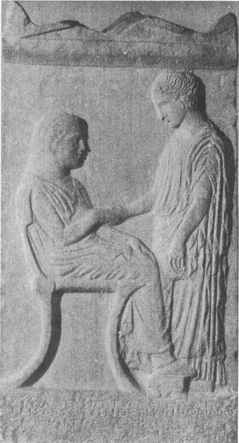

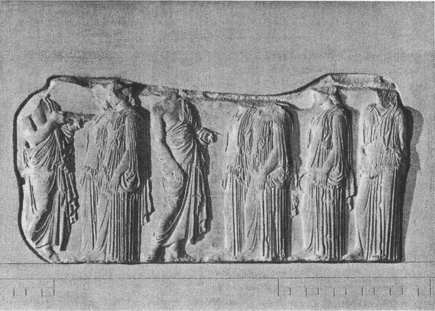

Several monuments and artifacts give additional evidence for these activities. A section of the Parthenon frieze (ca. 440–432 B.C.E., Fig. 3.3) represents the culmination of the Panathenaic procession in honor of Athena. At the right, the Archon Basileus, the chief magistrate of the Athenian state religion, assisted by a small child, folds the new peplos, a robe woven especially for the goddess. Behind the Archon, the priestess of Athena Polias receives two girls who bring stools on their heads. The girls are probably the Arrephoroi, who had helped in the weaving of the peplos, along with their other duties in the cult of Athena. Each year two (or four) girls between seven and about ten were chosen as Arrephoroi in the cult of Athena Polias on the Acropolis. They lived for a time near the Erechtheum, no doubt under the supervision of the priestess of Athena, and were present when the weaving of the peplos began. The culmination of their service was a secret ritual described by Pausanias (1.27.3): they carried something given them by the priestess down an underground passage on the slope of the Acropolis, deposited it at a special place, and brought something else back up. Two Loutrides or Plyntrides also removed garments from the statue of Athena on the Acropolis and washed them.

Figure 3.3. A detail of the east frieze of the Parthenon (ca. 440–432 B.C.E.) in Athens shows part of the Panathenaic procession for Athena, the frieze wrapped around the outside of the cella (the inner chamber housing the statue of the goddess) and presented the idealized citizenry of the city as handsome young men with their horses, beautiful young women with baskets and other gifts for Athena, and the mature men who governed the city.

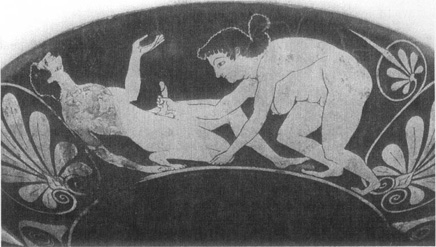

Since there were only two (or four) Arrephoroi per year, it was a great honor reserved for girls of noble families. Any girl, by contrast, could take part in the rites of Artemis at Brauron, although sources differ on what proportion of eligible girls may have participated.3 Because the sanctuary was on the east coast of Attica, far from Athens, the girls stayed at least overnight, in a stoa built for this purpose. Girls of different ages, but still before puberty, participated in races in honor of Artemis at her sanctuary at Brauron (Fig. 3.4). The ritual was known as the Arkteia (playing the she-bear), and the girls were dubbed “bears” after the animal that was associated with the huntress Artemis. Sometimes the girls ran nude, as here, at other times in a short garment, the chitoniskos (the nudity may indicate the girl’s wild, premarital state). These girls hold crowns of leaves and probably ran around an altar that is not preserved. The palm tree at right stands for Delos, the sacred island where Artemis and her brother Apollo were born (on the Arkteia, see further Kahil 1977 and Sourvinou-Inwood 1988b). Choruses of young girls participated in an all-night vigil on the Acropolis during the Great Panathenaia (Euripides, Heracleidae 777–83), and in spring maidens carried branches of sacred olive wrapped in wool in the procession to the temple in the Delphinium, where they supplicated Apollo and Artemis (Plutarch, Theseus 18.2).

Figure 3.4. Vase fragment (ca. 430 B.C.E.) with racing girls, probably at the sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron. This is one of the rare cases of female nudity in an image unconnected with prostitution, its outdoor setting is marked by a tree.

As an adult, a woman had the opportunity to participate in many cults, some alongside men and others limited to women. In the Panathenaic procession in honor of Athena, while men rode horseback and led the sacrificial oxen, women carried various objects for use in the sacrifice, including offering trays (cf. Fig. 3.5) and incense-burners. Women are most numerous on the east frieze of the Parthenon, which represents the head of the Panathenaic procession and the final preparations for sacrifice. The two young women shown at left in Figure 3.5 are the kanêphoroi, named for the offering trays (kanoun) they carry. These marriageable young women were given the exceptional honor of a share in the Panathenaic sacrifice. Each pair of women is met by one of the marshals who organize the procession and keep it moving according to plan. The marshal at the left holds a kanoun that he has taken from one of the women. Metic girls (resident aliens) carried water-jars and stools and parasols for aristocratic girls in the procession.

Figure 3.5. East frieze of the Parthenon (ca. 440–432 B.C.E.), with the maidens who carried trays as part of the procession in honor of Athena. The woman at the head of this group (left) has handed the tray to the marshal facing her.

Perhaps the most famous festival restricted to women was the Thesmophoria, a fertility rite for Demeter, travestied by Aristophanes in his Women at the Thesmophoria. Women, almost exclusively married citizens (concubines may have been included), organized their own festival, and spent three days living in Demeter’s hilltop sanctuary near the Pnyx. All public business in the Agora was suspended for the rite. We know very little of the well-kept secrets of this festival. A late source (scholion to Lucian, Rabe 275–76; Winkler 1990) tells us:

The Thesmophoria are a Greek festival containing mysteries.… They are celebrated, according to the more mythical account, because when Kore [the goddess Persephone] was seized by Plouto [god of Hades, the Greek underworld] while picking flowers, there was a swineherd named Eubouleus tending his pigs in that place and they were all swallowed up in the chasm along with Kore. Women known as Bailers, who have stayed pure for three days, bring up the rotten remains of objects that had been thrown down into the pits. Descending into the secret chambers, they bring the material back and place it on the altars. They believe that whoever takes some of it and scatters it along with his seed will have a good crop. They also say there are serpents down in the chasms, who eat most of what is thrown in: therefore the celebrants clap and shout when the women are bailing and when they replace those figures—to make the serpents go away, whom they consider to be the guardians of the secret chambers.

The passage goes on to say that the unspeakable objects thrown into the pits with the pigs are replicas of snakes and male genitals made from dough; all these, including the pigs, which are associated with female genitalia, help to promote fertility. Elsewhere we learn that during the Thesmophoria the women camped out on the hillside, imitating the life of humankind before agriculture, fasted and mimicked the mourning of Demeter for her lost daughter, and finally celebrated a feast in honor of birth (kalligeneia). (See further Brumfield 1981: 70–103)

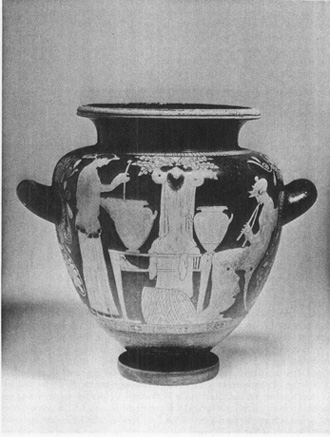

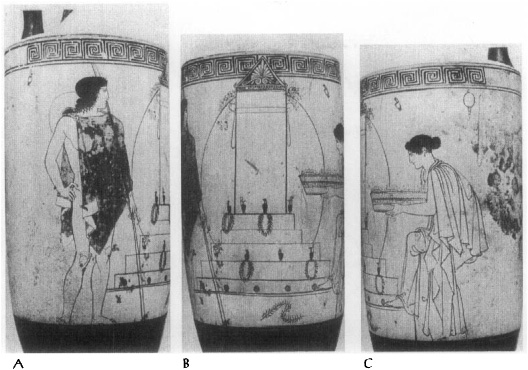

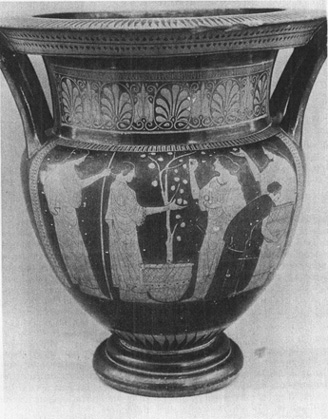

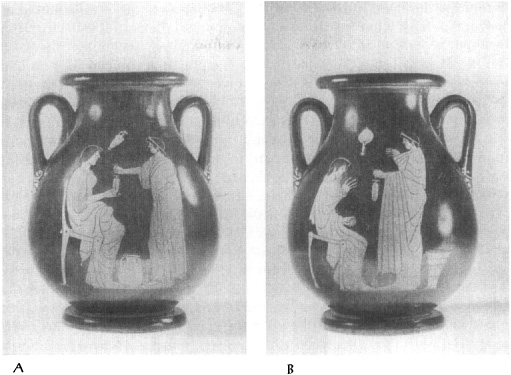

Dionysus was another important deity in the lives of women in classical Athens. Women may have attended the theatrical festivals in his honor (see earlier), and if so, they could have acquired considerable knowledge of contemporary literature. Although the evidence for historical maenadism (maenadic rituals performed by actual women and recorded in inscriptions, rather than represented in art and literature) does not begin before the fourth century B.C.E., women played important roles in cults such as the Lenaia and the Anthesteria. The Lenaia was a festival of Dionysus in which women were especially prominent; the name derived from lenai, a synonym for maenad, the god’s female devotée. In Fig. 3.6A the focus of the ritual is a mask of Dionysus affixed to a column and decorated with leaves and branches. The woman at the left ladles wine from a stamnos (the same type of vessel as this one), perhaps into the kantharos carried by the middle women on the reverse of the vase. This is the ritual shape of wine cup associated with the god Dionysus (cf. Fig. 3.6B). Other offerings are the meat and breads heaped on the table in front of him. The seated woman playing the flutes is crowned with the god’s sacred ivy. On the ground in the center is a long object like a flat basket, which was used to carry the mask of Dionysus to the sanctuary where it would be set up for worship.

Figure 3.6. A: Vase (ca. 450 B.C.E.): Cult rituals in honor of the god Dionysus, a favorite of women in both Greek and Roman culture.

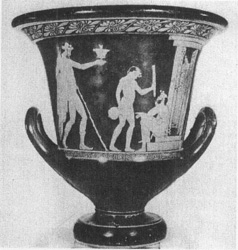

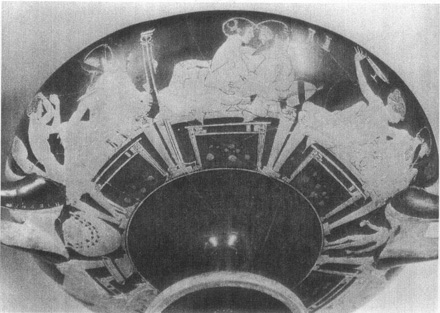

The Basilinna, the wife of the Archon Basileus, played a key role in the celebration of the Anthesteria, a three-day festival of Dionysus in late winter. She made secret offerings on behalf of the city at Dionysus’s sanctuary, administered a sacred oath to fourteen women (the Gerarai) who performed rituals under her direction, and became for one night the symbolic wife of the god. The wedding of Dionysus and the Basilinna took place at the Boukoleion, a building that otherwise served as the headquarters of the King Archon (Basileus). In a red-figure vase of c. 440 the Basilinna sits on the bridal bed that we glimpse through open doors, awaiting the god. He approaches unsteadily, after a generous sample of the new wine that was celebrated in this festival (Fig. 3.7). Dionysus is preceded by a young satyr holding a wine pitcher called a chous (this second day of the festival was called Choes, after the shape), and an old satyr casually guards the door to the chamber (see further Simon 1963 and 1983).

Figure 3.6 B: Vase (ca. 450 B.C.E.) as in A. Woman with a ritual wine cup, or kantharos.

Figure 3.7. Vase (ca. 440 B.C.E.) showing the drunken Dionysus coming to visit his bride, the Basilinna, who waits within the doorway of the house.

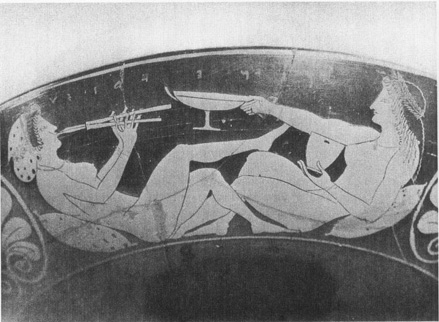

Both vase paintings and literary passages generally suggest that Dionysiac rites involved release from ordinary life and its cares. Dionysus was the god of wine, and his worship could include departure from household tasks, dancing to the excited rhythms of the aulos (often translated “flute,” but actually closer to the modern oboe) and drums. For these reasons, we can understand some of its special appeal to the relatively confined and secluded women of Athens (Kraemer 1979). In poetry and vases female worshipers of Dionysus wear fawnskins, wreathe their hair with ivy and snakes, and carry a thyrsus, a branch topped with ivy leaves (see Fig. 3.8). Although the actual worship of Dionysus by Attic women was more subdued, the following passage from Euripides’ Bacchae, in which the chorus of women try to convert Thebes to Dionysus, may convey something of the spirit of Dionysiac worship:

O Thebes, nurse of Semele,

wreathe yourselves with ivy!

Abound in bryony, green

and brilliant with berries!

Make yourself a bacchant with branches

of oak and pine and

fringe your dappled fawn skins

with tufts of white wool!

Treat your violent wands

with reverence. The whole earth will dance at once!

Bromius is he who leads his bands

to the mountain, to the mountain where

the crowd of women waits

driven from their looms and shuttles

by Dionysus!

Euripides, Bacchae 105–19 [ca. 406 B.C.E.];

trans. Helene P. Foley)

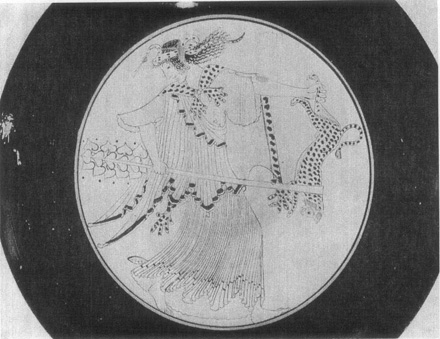

Figure 3.8. Interior of an Attic white-ground cup by the Brygos Painter, ca. 480 B.C.E., A maenad, a female follower of the wine god Dionysus, appears wearing an animal-skin cape, a snake in her hair, and carrying a thyrsus and panther in her hands, all these testify to the maenad’s wildness.

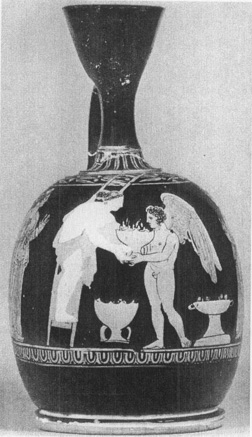

In the late fifth century, when Athens had a large foreign population, many cults from abroad were introduced, such as that of the Asiatic vegetation god Adonis (see the passage from Plutarch quoted earlier, and the discussion of Theocritus 15 in Chapter 5), whom the goddess Aphrodite loved and lost. His worship seems to have been especially popular with nonaristocratic women and hetairai. The rites for Adonis were held at night during the hot season of late July. Groups of women celebrated on the rooftops, lamenting for the beautiful young dead god Adonis. Special miniature “gardens for Adonis,” broken terra-cotta pots with seeds, were made to sprout quickly and then set out to wither in the sun on the roofs of houses. On a red-figure lekythos (Fig. 3.9), Aphrodite herself, assisted by Eros, carries the little gardens up a ladder as mortal attendants, devotees of the divine couple, look on (see further Weill 1966).

Figure 3.9. Perfume vase (ca. 380 B.C.E.) showing Aphrodite climbing a ladder to place a little “Adonis garden” on a rooftop, as did the women of Athens who commemorated the death of the goddess’s young lover.

The Haloa, a festival named for the threshing floor on which it took place, was celebrated for Demeter and Dionysus at Eleusis. Again, we only have a glimpse of women’s roles in this ritual from a late ancient source, which expresses embarrassment at important fertility rites that would have made far more sense to those who performed them:

On this day there is also a women’s ceremony conducted at Eleusis, at which much joking and scoffing takes place. Women process there alone and are at liberty to say whatever they want to: and in fact, they say the most shameful things to each other. The priestesses covertly sidle up to the women and whisper into their ear—as if it were a secret—recommendations for adultery. All the women utter shameful and irreverent things to each other. They carry indecent images of male and female genitals. Wine is provided in abundance and the tables are loaded with all the foods of the earth and sea except those that are forbidden in the mystical account, that is, pomegranate, apple, domestic birds, eggs, and of sea creatures red mullet, eruthinos [a hermaphrodite fish], blacktail, crayfish, and dogfish. The archons set up the tables and leave them inside for the women while they themselves depart and wait outside, showing to all inhabitants that the types of domestic nourishment were discovered by them [the Eleusinians] and were shared by them with all humanity. On the tables there are also genitals of both sexes made of dough.

(Rabe 279–81; Winkler 1990)

Priestesses

Cults of female divinities regularly had priestesses as their chief personnel, but, like their male counterparts, these women were not chosen for extraordinary piety or after special religious training. Generally the priesthood was either hereditary within a family or was “bought” by a wealthy family for one of its members, for a limited term in office (see further, Turner 1984). Although they were subject to state audits (Aeschines 3.18), there is little evidence that the priestesses profited from their office in any way, although the decree for the building of the Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis specifies that the priestess shall receive the skins of sacrificial animals (Inscriptiones Graecae I3 35; Meiggs and Lewis 1969, no. 44) and the Priestess of Demeter at Eleusis apparently received fees from initiates (see the Chapter 13).

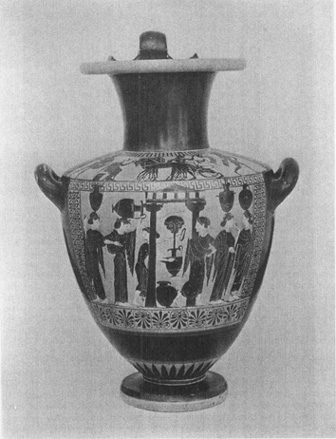

Before the fifth century, references to priestesses in Athens are few and vague, e.g., Herodotus’s mention that when the Spartan king Cleomenes tried to enter the Acropolis in 508, the priestess of Athena told him it was unlawful for a Spartan (5.72). Yet by the middle of the sixth century, in the wake of the reorganization of the Panathenaic festival in 566, we find numerous depictions in vase painting of the cult of Athena, including a woman who may be identified as her priestess on the Acropolis (Fig. 3.10). Here a sacrificial procession led by the priestess approaches a statue of the goddess on the Acropolis. Two men lead an ox that will be sacrificed at the altar that stands between priestess and statue. The priestess does not wear any sacerdotal clothing, but is marked by her proximity to altar and statue and by her gesture of holding out purificatory branches toward the goddess she serves. The subject is essentially the same as that depicted much more grandly on the Parthenon frieze a century later (cf. Figs. 3.3 and 3.5).

In the fifth century and later, many priestesses are known by name from inscriptions. By far the most famous, and the subject of much scholarly controversy, is Lysimache, who was priestess of Athena for sixty-four years in the later fifth and early fourth centuries (Pliny, Natural History 34.76). She appears in an inscription on a statue base; the statue, now lost, may well have depicted Lysimache as priestess of Athena. She has been identified as the model for Lysistrata, in Aristophanes’ play, and both names, Lysimache and Lysistrata, meaning “disbander of armies,” occur in later generations of the Eteoboutad family that held the hereditary priesthood of Athena Polias (see Lewis 1955).

Figure 3.10. Black-figure vase (ca. 550–540 B.C.E.) with the cult statue of Athena on the Acropolis, a priestess and two men with an ox approach the altar before the statue. The most sacred statue of Athena was a small and crude wooden one. This image may reflect another statue of Athena that stood in a second temple on the Acropolis or in the open.

One other priestess of the fifth century whom we know by name was Theano. When Alcibiades was condemned in absentia in 415 for parodying the mysteries of Demeter, Theano refused to curse him publicly, as had been required of all priests and priestesses (Plutarch, Alcibiades 22.4).4 The name Theano can hardly be accidental, since in Homer this is the name of the priestess of Athena at Troy (Iliad 6.297–300). This suggests that some priestesses may have taken on “professional” names during their term in office.5

We should not underestimate the importance of women’s religious role in Athens. (See the section on religious dedications by women in Chapter 1 for an example of a religious dedication made by a Classical woman.) Plutarch tells us that during a struggle between the followers of Megacles and Cylon in the seventh century, those followers of Cylon who took refuge at altars were slaughtered; but those who supplicated the wives of the archons were spared. (Solon 12.1) In passages cited earlier, women’s role as lamenters of the dead was viewed by moralizing writers as potentially disruptive; other writers suggest that religion could lead women into adultery. In Lysias 1 (see later under “Adultery”) the defendant’s wife was first seen by her future lover at her mother-in-law’s funeral. Plutarch dismisses allegations that the architect Pheidias arranged assignations for Pericles with freeborn Athenian women who came to the Acropolis on the pretext of looking at works of art (Pericles 13.15). Yet it is less the unreliable allegation than the reported pretext for the women’s presence that is of interest here (see also the interest of the chorus of women at Euripides’ Ion 184ff. in observing the religious monuments at Delphi).

In drama women often cite their important role in religion when they protest against their literary reputation for adultery, drinking, or irresponsibility. Sometimes they recall the city’s interest in their religious upbringing (Aristophanes, Lysistrata 641–47, quoted earlier). In the passage below, Euripides’ Melanippe offers the most powerful defense of her sex for its role in religion (women did not serve as prophets in Athens, but they did at the other places in Greece mentioned here):

Men’s blame and abuse of women is vain—

the twanging of an empty bowstring.

Women are better than men and I will prove it.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

They manage the house and guard

within the home goods from the sea.

No house is clean and prosperous without a wife.

And in divine affairs—I think this of the first importance—

we have the greatest part. For at the oracles of Phoebus

women expound Apollo’s will. At the holy seat of Dodona

by the sacred oak the female race conveys

the thoughts of Zeus to all Greeks who desire it.

As for the holy rituals performed for the Fates

and the nameless goddesses, these are not holy

in men’s hands; but among women they flourish,

every one of them. Thus in holy service woman

plays the righteous role. How then is it fair for

the race of women to be abused? Will not

the empty censure of men cease; and those who think

all women should be blamed alike if one is found

erring? Let me make further distinctions.

There is nothing worse than a bad woman,

and nothing better than a good one.

Only their natures differ …

(The Captive Melanippe, frag. 13,

Page Greek Literary Papyri [420s B.C.E.?];

trans. Helene P. Foley)

As additional defenses against their reputation, women cite the contributions they make to the city in the form of sons (Aristophanes, Women at the Thesmophoria), or their thrifty management of the household, which is far less corrupt and more generous than the actions of men in the assembly (Women at the Assembly). Sometimes they announce that if they had been allowed a public voice in poetry, they would have sung an answer to the other sex, who are just as guilty of adultery and betrayal as women (Medea 410–30).

Domestic Activities

Women also participated in religious rituals more closely associated with their roles in the family. Domestic cults required daily tending. Marriages, funerals, and the care of the dead at family tombs may have been less ostentatious and less assertively public than in the Archaic period, but they still offered occasions to mark women’s contribution to the continuity of individual oikoi, a continuity Athenian law and custom made a point of protecting.

Care of the Dead

We have already discussed women’s more subdued role as lamenters of the dead. Yet the care of the dead did not end with the funeral and burial. The grave had to be continually visited and provided with offerings, and this responsibility fell primarily to Athenian women. On a typical funerary vase (Fig. 3.11), the visitor arrives with a large basket of offerings at a particularly elaborate tomb, a tall stele standing atop a stepped platform and crowned by a floral acroterion. The offerings that fill the steps are of two types, wreaths and small jugs of perfumed oil, the same shape as the vase on which this scene is painted. Another lekythos of this type floats in the background. This shape, especially when covered with a white slip, as here, was made exclusively for funerary use. The visitor is dressed only in the sleeveless fine linen chiton that became fashionable in Athens during the fifth century. From the middle of the century, in both sculpture (cf. Fig. 3.5) and vase-painting, the sheer garment clings to the body, revealing the forms underneath. But this should be taken more as a reflection of artistic taste than as a deliberate attempt to eroticize women’s bodies, especially on a solemn occasion like this. We should not assume that women actually went out in public dressed in transparent clothing, any more than the nude male warriors in Greek art reflect actual battle practice.

Figure 3.11. Funerary vase, or lekythos (ca. 440 B.C.E.) in the white-ground technique, which permitted delicate use of outline for depictions of scenes of mourners. The youth at left, nearly nude and carrying a spear (A), is perhaps an apparition of the deceased, a male relative of the woman who visits his tomb (B and C).

On another vase of similar type (Fig. 3.12), a young woman, coming to lay an offering at the tomb of a dead relative (her mother?) is confronted by an apparition of the deceased. The offering is a kind of sash that will be tied around the stele, which already has two such ornaments. Such epiphanies of the deceased at their tombs are not uncommon on white lekythoi of the late fifth century. They are not to be taken literally, but simply offer the viewer a “portrait” of the deceased that often corresponds to the types found on contemporary marble gravestones (cf. Fig. 3.1 and Mnesarete in the Introduction to Part I). Here the woman rests her chin on her fist in a dejected pose, as if brooding over her own death.

Figure 3.12. White-ground lekythos (ca. 430 B.C.E.) with a scene of a beribboned stele to which a woman comes bearing another sash. At left is a seated woman, perhaps the deceased.

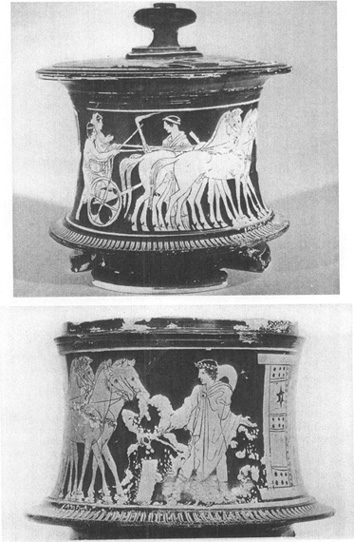

Weddings

The central event of an Athenian wedding was the procession in a simple chariot from the home of the bride to that of the groom (Figs. 3.13 and 3.14), and court cases often cite this moment as proof of a wife’s legitimacy. The procession traditionally took place at night; hence the presence of figures carrying torches to light the way. The bride, still veiled, stands in the car as her husband mounts it in preparation for the journey. Other relatives follow the chariot on foot, bringing gifts for the couple. This small cylindrical vase with lid is a pyxis, a box for women’s toiletries. Such an object would have been a typical gift for the bride. On the day after her wedding, an Athenian woman was visited by her female friends and relatives. In Figure 3.15 the bride stands at the right, in front of the doors to her bedroom, receiving her guests. The gifts include nuptial vases filled with greenery, and one woman plays with a pet bird. On the wall behind are hung a mirror, attribute of the bride (cf. Fig. 3.2) and a wreath. All the women have been given mythological names; the bride is Alcestis, prototype of the virtuous wife because of her loyalty to her husband and willingness to die in his place. This unusual object is known as an epinetron because it was meant to be placed over a woman’s knee, the roughened upper surface used for carding wool.

Figure 3.13. Pyxis (ca. 440–430 B.C.E.) for cosmetics, ornamented with a bridal scene. The attendant family and friends bear gifts including a large jar and a box, perhaps containing jewelry, household goods, or the bride’s trousseau. The door to the left is a sign for the house.

Figure 3.14. Pyxis as in Figure 3.13, here showing the bride carried in a chariot to her new home. The composition of bride and charioteer is reminiscent not only of other wedding scenes but also of the abduction of Persephone by Hades as it appears in Greek art (cf. Fig. 1.8). The god Hermes leads the couple to their new home. 100

Figure 3.15. Epinetron (ca. 420 B.C.E.) with scenes of a bride and her guests and gifts. The epinetron is a curved piece of ceramicware placed over the leg of a woman who then cards the raw wool on it.

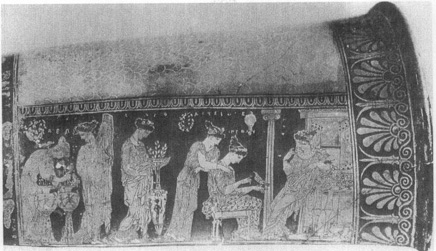

In the last third of the fifth century, young brides and grooms are shown together in moments of quiet intimacy that convey a new, more romantic and idealized notion of heterosexual love (see Sutton 1981). In creating the imagery of the ideal couple, artists take liberties with some of the realities of life. The groom, for example, is regularly shown as a beardless ephebe, a young man of approximately seventeen to nineteen years of age, although we know that most Athenian men did not marry before their mid- to late twenties, when they certainly had a full beard. The bride, on the other hand, may well seem more mature than the fourteen- or fifteen-year-old girl she often was. On a loutrophoros, the vessel used to hold water for the bridal bath (Fig. 3.16), the groom typically leads his new bride gently by the hand toward the marriage chamber. The little Erotes (Cupids) that flutter about the bride add a touch of romantic fantasy. Such scenes, decorating gifts for the new bride, were no doubt meant to calm her fears of the unknown by painting a rosy picture of her wedding day and of the handsome stranger she had yet to meet.

Women in the Household

The life of respectable women (the wives and female relatives of citizens, and very probably of resident aliens as well) within the household was secluded, primarily in order to protect their role as producers of legitimate heirs; it was less secluded, however, than popular ideals might have allowed. Furthermore, as might be expected, women had informal opportunities to influence the men in their families and sometimes violated the laws attempting to regulate their reproductive powers.

Figure 3.16. Vase for water for a bride’s bath (loutrophoros), probably a wedding gift, A. The groom leads the bride toward the bedroom, B. indicated by the doorway (ca. 430 B.C.E.).

After marriage, a young woman assumed responsibility for the prosperity of her husband’s household and for the well-being of its members. The Oeconomicus of Xenophon, a Socratic dialogue written in the second quarter of the fourth century B.C.E., describes the management of the oikoi of the wealthiest Athenians. Young wives, apparently with little training for the job, sometimes managed large households. Xenophon and his interlocutor Socrates are critical of the girl’s lack of domestic education:

Socrates said, “As for a wife—if she manages badly although she was taught what is right by her husband, perhaps it would be proper to blame her. But if he doesn’t teach her what is right and good and then discovers that she is ignorant of these qualities, wouldn’t it be proper to blame the husband? Anyhow, Critobulus, you must tell us the truth, for we are all friends here. Is there anyone to whom you entrust a greater number of serious matters than to your wife?

Critobulus replied, “No one.”

“Is there anyone with whom you have fewer conversations than with your wife?”

Critobulus answered, “No one, or at least not very many.”

“And you married her when she was a very young child who had seen and heard virtually nothing of the world?”

“Yes.”

(3.11–13; trans. Sarah B. Pomeroy)

Socrates tells Critobulus of the conversation Ischomachus had once had with his wife when they were newly married and he was describing her function in his household:

“ ‘Certainly, you will have to stay indoors and send forth the group of slaves whose work is outdoors, and personally supervise those whose work is indoors. Moreover, you must receive what is brought inside and dispense as much as should be spent. And you must plan ahead and guard whatever must remain in reserve, so that the provisions stored up for a year are not spent in a month. And when wool is brought in to you, you must see that clothes are produced for those who need them. And you must also be concerned that the dry grain is in a good condition for eating. However, one of your proper concerns, perhaps, may seem to you rather thankless: you will certainly have to be concerned about nursing any of the slaves who becomes ill.”

(Oeconomicus 7.35–37. On nursing the sick, see also [Dem] 59.56)

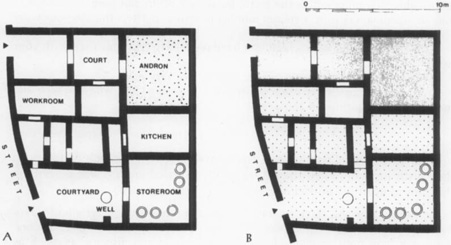

Women are repeatedly said to inhabit “women’s quarters” in the most remote and protected part of the house. The wife, other freewomen in the household, and female slaves normally lived and worked in these women’s quarters. Plato (Laws 781c) captures the nature of these confined spaces when he describes women as a race “accustomed to a submerged and shadowy existence.” Although these quarters are not always easy to locate in the archaeological remains, some traces can be seen in the plan of a house excavated on the north slope of the Areopagus in Athens (see Fig. 3.17). The men’s quarters on the north side of the house and the women’s quarters on the south side each have their own entrance. There is no access to the Andron (men’s quarters) from the women’s quarters.6 Even a household of modest means usually included a female slave so that the wife was not obliged to perform chores out-of-doors where she might encounter men who were not close kin and who therefore posed potential threats to her chastity and the legitimacy of the family’s heirs.

As might be expected, scenes depicting husband and wife together after the wedding are rare, but portrayals of women together in the women’s quarters without any men present are common. The principal activity portrayed on vase paintings as characteristic of respectable Athenian women who stayed at home was weaving and the making of clothing for the family. This was a woman’s most important contribution to the economy of the household and, from the time of Homer’s Penelope, the symbol of the virtuous and industrious wife. Socrates advises a man who is having trouble supporting a large group of female relatives to put them to work making wool; they will contribute to the household and be happy to be occupied (Xenophon, Memorabilia 2.7.2–14.) On a red-figure cup (Fig. 3.18), a seated woman draws strands of wool from a basket (kalathos) and smoothes them over her leg, as a friend watches.

Figure 3.17. A. Plan of a house (fifth century, B.C.E.) on the north slope of the Areopagus in Athens, with indications of the separation of men’s and women’s quarters and the placement of the latter in an area with no direct connection to the andron, the room for men’s gatherings. B. Women’s quarters are marked by + and men’s are shaded.

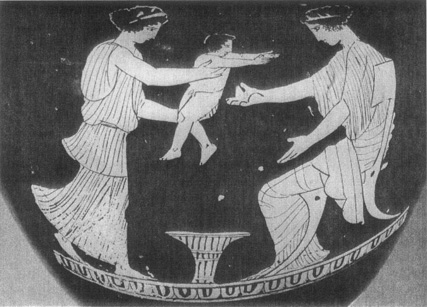

Child care was of course a main preoccupation of the women’s quarter of an Athenian house, though the subject is not commonly shown in vase painting. In one unusual example (Fig. 3.19), the mother is handed her child by a slave girl. The kalathos in the middle is not in use, but is simply a token of the respectable housewife. The babies depicted on Athenian vases are inevitably male, perhaps reflecting the concern of all Athenians to produce a male heir.

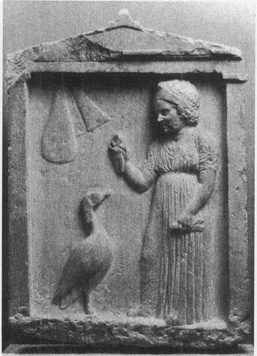

Playing with dolls and nurturing pet animals prepared a girl for marriage and motherhood. Dolls were dressed as girls of marriageable age. Little girls are often distinguishable from grown women in Greek art only by their small stature. Their chignons and long dresses are those of mature women, and Greek artists of the classical period still had difficulty in rendering convincingly a child’s face. A girl on a gravestone, in one example (Fig. 3.20), wears a fine linen chiton, girded high above the waist, as was fashionable in this period, and a fillet in her wavy hair. But the girl is probably meant to be only five or six. Her name is Plangon (Doll), and the doll that she so prominently displays may be a play on the name. Beside the toy, she is shown with her favorite pet, a goose.

Figure 3.18. Interior of a cup (ca. 470 B.C.E.), with a woman watching as another works wool from a wool-basket. The furniture, a klismos chair with its saber-curved legs and a padded stool, indicates in abbreviated form the decoration of the house.

Figure 3.19. Vase (ca. 450 B.C.E.), with a baby brought to his seated mother. The swirling skirt of the hurrying attendant and the outstretched arms of mother and infant give the scene a sense of emotional immediacy as attractive as the composition, in which the chair curve and the flip of the servant’s hem follow the curves of the vase.

Figure 3.20. Grave stele of Plangon, a young girl with a doll and a pet goose (325–320 B.C.E.).

Hanging in the background are textiles that may include the sakkos, worn loosely over the hair. Unlike boys of the same age, girls were rarely portrayed nude (the vases found at Brauron discussed above are an exception, see Fig. 3.4).

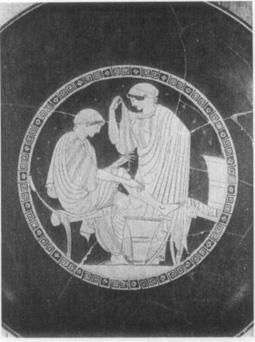

The evidence of vase painting also suggests, however, that women at home engaged in more intellectual activities than we would suspect from written sources, especially reading and playing music. For example, in Figure 3.21, the seated woman hunches over an opened bookroll. She is no doubt reading aloud to the three women who accompany her, one of them holding a chest that could contain jewelry or other valuables. Scenes in the women’s quarters seldom include any men, but they do show that it was common for small groups of women to gather, whether for work (weaving) or for relaxation.

Women’s Work Outside the Home