The world of the high and late Empire kept the conservative ideal of Roman womanhood it had inherited from the Republic. At the same time, the discrepancy between the gender values of the period and lived reality was as great as it had always been; women’s lives were far more variable than the ideal indicated, and there were often more extreme differences in the circumstances of women of different social strata than there were in the lives of men and women of the same social stratum. This pattern we have seen as pervasive in all our discussions of Roman women.

In this chapter, we confront a new issue: geography. How are we to assess the lives of women across a gigantic and complex empire, one whose greatest expanse in the second century C.E., included southern Scotland and the Sahara, the Atlantic coast and inland Turkey? Here were women of the frontiers to whom the Romans referred as “barbarians” and women of Athens whose cultivation and nobility were irreproachable. Not only was the Empire larger and more diverse than ever, it also played an ever-larger part in the consciousness of the city of Rome and the emperor. Rulers and their wives now came from the provinces or from provincial ancestry. Soldiers and merchants came from everywhere and carried the ideas and customs of their own lands to every corner of the Empire at the same moment that they contributed to the dissemination of Roman ideas. And finally, in 212 C.E., the emperor Caracalla issued an edict making every freeman and woman who lived in the Roman provinces a full Roman citizen. Ultimately, the period we are examining, from the middle of the first century to the end of the third, saw the creation of a new culture, one in which local ways remained visible while Romanization was taking place and in which Romanization itself gradually changed from being clearly Italian as it absorbed elements of the local cultures of province and periphery and became increasingly hybrid.

To understand this complicated world is no easy task. Not only do we deal with an expanded geographic field, but the temporal field in this chapter encompasses two and a half centuries, from the death of Nero in 68 to the legalization of Christianity under Constantine in 311–12. This period was full of changes in politics and culture, yet its history has always been difficult to write because the evidence is so scattered and ambiguous. Unlike the Augustan period, the later Empire is represented by few surviving literary texts, especially after the mid-second century, when the interpretive work of an analytic historian like Tacitus is replaced by the anonymous and often self-contradictory biographies of the compendium called the Historia Augusta, the history of the rulers. Large-scale public monuments are still constructed until the early third century, then become rare until the end of the century. Private monuments are common everywhere but, like many of the inscriptions of the period, they are often difficult to date; and the abundant archaeological material is unevenly distributed both temporally and geographically. For all these reasons, to write a chronological history of women, never an easy task in any period, becomes almost impossible.

What guides our arrangement and discussion of material in this chapter, then, is a grid with multiple and variable lines on it. Time appears most regularly where place is less visible—in our section on the women of the court. Here, because of the chronology imposed by the rulers themselves, the women of their families can be seen in time, although patterns of historical change in their lives are almost as hard to make out as they are in the lives of “ordinary” women. For them, whoever these “ordinary” women might be, place and social status make more of a difference to the way they live than time seems to, although this is probably as much a result of missing evidence as of enduring or conservative gender roles. Our scattered and varied evidence of women in the high and later Empire, presented according to their social locations, suggests that the conservative Republican gender ideals of the elite men in the city of Rome remained normative and defined “tradition” for many within the Empire. Those in other parts of the Empire who shared the social standing or the social aspirations of that conservative elite drew on this tradition, and they used the gender ideal as a way to speak of belonging, whether to a social stratum, a place, or a moral vision. It helped to define them as ROMAN. For the rest, the ideal was unknown, out of reach, or perhaps we simply have no evidence of them and their motives at all. They are, nonetheless, a crucial part of the richness of this cosmopolitan imperial environment, called by the Romans orbis terrarum, the entire world.

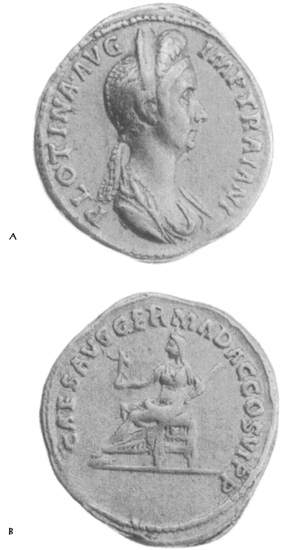

Figure 13.1. Gold coin of Plotina from Rome, ca. 112–115 C.E., with her portrait on the obverse (A), and Vesta seated on the reverse (B).

Empresses and Women of the Upper Classes

The wife of Agricola, Domitia Decidiana, was a woman of Roman traditional virtue: the marriage, says her son-in-law Tacitus, writing toward the end of the first century C.E., was characterized by concord and praiseworthy kindness between the partners: “they lived in rare accord, maintained by mutual affection and unselfishness; but in such a partnership the good wife deserves more than half the praise, just as a bad one deserves more than half the blame” (Agricola 6.1; Mattingly 1948). The Panegyric, which Pliny the Younger, governor of Bithynia under Trajan, wrote in 100 C.E. to praise the emperor, compliments Trajan on his choice of partner and lets the world know that the empress Plotina’s traditional goodness (Fig. 13.1: Coin of Plotina associated with goddess Vesta), like Domitia’s, reflected credit on her husband and his public life:

your own wife contributes to your honour and glory, as a supreme model of the ancient virtues; the chief pontiff himself, has he to take a wife, would choose her or one like her—if one exists. From your position she claims nothing for herself but the pleasure it gives her, unswerving in her devotion not to your power but to yourself.… How modest she is in her attire, how moderate the number of her attendants, how unassuming when she walks abroad! This is the work of a husband who has fashioned and formed her habits: there is glory enough for a wife in obedience. When she sees her husband unaccompanied by pomp and intimidation, she goes about in silence herself, and so far as her sex permits, she follows his example of walking on foot.

(Panegyric 83; Radice 1975)

Compare this with an inscription of late fourth century C.E., Rome, set up by a member of the non-Christian elite in honor of his wife Paulina, whom he calls “chaste, faithful, pure in mind and body.” Paulina speaks in her own voice on the back of the statue base:

The glory of my own parents gave me no greater gift than that I have seemed worthy of my husband; but all fame and honor is in my husband’s name … Because of you (husband Agorius), all hail me as blessed and holy, because you yourself proclaim me throughout the world as a good woman; I am known to all, even those who do not know me. Why should I not be pleasing, with a husband such as you?

(Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.1779 / Inscriptiones Latinae Liberae Rei

Publicae 1259; Gardner and Wiedemann 1991: 66–67)

Traditional Ideals of Womanhood

Through much of the Imperial period, the ideal of Roman womanhood remained remarkably consistent. The ideal, rooted in the social conditions of the city of Rome, the capital of the great Empire, was articulated by Roman writers, largely men of the elite (upper-class or intellectual), and it drew heavily on the language of the conservative gender ideology of the Republican and Augustan periods, not least because these men, like Agorius, never stopped reading “whatever was composed in Latin or Greek, whether the thought of wise men for whom the gate of heaven stands open, or the verses which skilled powers have composed, or prose writings” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.1779; Gardner and Wiedemann 1991: 67). Embedded in law, literature, and art, and supported in the East by comparable Greek traditions of literature (see below, Plutarch’s “Advice to Bride and Groom”) and social life, the ideal spread to the most Romanized and Hellenized parts of the Empire, often appropriated first by the local upper classes as a part of the process of assimilation and political mobility.

The Roman ideal appears most clearly in those passages in speeches to emperors, letters to mothers, and epitaphs that intend to compliment women. There the ideal was constantly reiterated in language that changed surprisingly little over the course of six hundred years. However, in other genres, it seldom finds pure and disinterested expression. We locate it in poems, histories, letters to friends, entangled in a web of political gossip, spoken in the same breath as castigation, enmeshed in and complicated by practices that seem to modern eyes to be in direct conflict with it. Two examples of upper-class Roman women of Italy mentioned in the letters of Pliny the Younger (compiled between 97 and 112 C.E.) may make the problem visible, if not clear.

[Pompeius Saturninus] has recently read me some letters which he said were written by his wife, but sounded to me like Plautus or Terence being read in prose. Whether they are really his wife’s, as he says, or his own (which he denies) one can only admire him either for what he writes, or the way he has cultivated and refined the taste of the girl he married.

(Letters 1.16.6; Radice 1975)

The letters cannot be by the wife, according to Pliny, but if they are, the credit must go to her husband for the education he has given her. Again we hear the language of Agorius’s wife Paulina, who credits all her fame and honor to her husband, and of Pliny’s discussion of Plotina, whose wonderful behavior he says is the work of the husband who formed her.

When credit does go to a woman, Ummidia, it is hardly unproblematically rendered.

Ummidia Quadratilla is dead, having almost attained the age of seventy-nine and kept her powers unimpaired up to her last illness, along with a sound constitution and sturdy physique which are rare in a woman. She died leaving an excellent will: the grandson inherits two-thirds of the estate, and her granddaughter the remaining third.… He lived in his grandmother’s house but managed to combine personal austerity with deference to her sybaritic tastes. She kept a troupe of pantomime actors whom she treated with an indulgence unsuitable in a lady of her high position, but Quadratus never watched their performances either in the theatre or at home, nor did she insist on it. Once when she was asking me to supervise her grandson’s education she told me that as a woman, with all a woman’s idle hours to fill, she was in the habit of amusing herself playing draughts or watching her mimes, but before she did she always told Quadratus to go away and work: which I thought showed respect for his youth as much as her affection.

(Pliny the Younger, Letters 7.24.1–5, abridged; Radice 1975)

Ummidia’s wealth allows her trivial and morally ambiguous pastimes, but she raises her grandson responsibly, keeps him out of the way of her games and her mime troupe, and then leaves all her wealth to her proper heir. Pliny does not mention another proper use of her money, but we can learn it from inscriptions; Ummidia was as generous a patron to her community as Pliny was to his, and she is on record as giving to her hometown, Casinum, a temple, an amphitheater and a stage (Raepsaet-Charlier 1986: 649, no. 829; Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI.28526; Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X.5183 = Inscriptiones Latinae Liberae Rei Publicae 5628).

What emerges from these two letters is a sense that female virtue in the old Republican version is no longer the only form (was it ever?) for upper-class womanhood. Education and wealth may be both problematic and respectable at the same time. The writing wife, framed as her husband’s creature, is nevertheless part of the game, part of a literate, writing world; the rich old lady, freed from male control and able to do as she likes, nevertheless, like the men of her class, acts responsibly to her grandson and generously to her community. In neither case is virtue clearly expressed since the women involved are crossing some essential boundaries: both letters reflect the responses of a judgmental and conservative, though not unsophisticated, man, to these complex gender practices. Throughout this chapter we will continue to see representations of women behaving around, against, and near the ideal; however, only when compliments are paid to a mother, wife, or empress are women pictured as fully exemplifying this ideal.

Empresses

Pliny the Younger’s Panegyric, delivered in 100 C.E. emphasized virtues of modesty and restraint in speaking of Trajan’s wife Plotina and the emperor’s sister Marciana; the two women lived harmoniously in his household, united without envy or quarrels in their loyalty to the ruler (Panegyric, 83; see above, under “Traditional Ideals of Womanhood”). The ideal takes the usual form: self-effacing wives and mothers, dutiful and modest, placing family before everything except perhaps Rome itself. When Hadrian gave his funeral orations for Plotina (in 121 or 123?) and for his mother-in-law Matidia, the niece of Trajan (in 119), he stressed these same virtues once more. After speaking of his personal grief at the death of Matidia, Hadrian went on to describe her fidelity to her husband’s memory.

[She mourned him] during a long widowhood in the flower of her life, a woman of the greatest beauty and chastity, [very obed]ient to her mother, herself a mother most indulgent and a most devoted kinswoman, helping all. A burden to no man nor disagreeable to any man, and in her relations with me of extraordinary [goodness], with such modesty that she never asked anything from me [for herself and often] did not ask what I would rather have been asked by the women of my family. She in her good will prayed with many extended vows for such [good fortune] to befall me, and preferred to rejoice in my good fortune rather than benefit from it.

(Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 14.3579; Smallwood 1966: 56 n. 114)

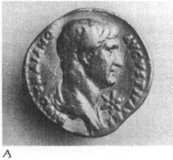

Despite the laudable harmony of Trajan’s household, fourteen years elapsed after he became emperor in 98 before any of the women of his family were depicted on coins, including his wife Plotina, his sister Marciana (whose death in 112 may have provided the impetus for the coinage) and her daughter Matidia. Restraint in providing public honors to the women of the court characterized the reign of Trajan, as it had also the time of Augustus (at least in Rome and the West). The types the Trajanic coins use for these women include association with Vesta, Fides, and Pietas, all about traditional virtues of home, hearth, religion, and children (with Matidia) (Fig. 13.1). As far as we know, none of the Imperial women is represented on the historical reliefs of the period, but Plotina and Marciana did receive the honorific Imperial title of Augusta soon after 100, when Pliny commended them for their modesty in declining the Senate’s first offer of the title (Panegyric 84). Marciana and her daughter Matidia were the first Imperial women to receive the title without being either wife or mother of an emperor; other honors, however, came to them and Plotina only after Trajan’s death. His successor Hadrian, who was married to Sabina, daughter of Matidia and thus grandniece of Trajan, saw his association with these Imperial women as a guarantee of his own authority; for this reason, he declared Plotina Augusta in 128, and had both women deified on their deaths, starting with Matidia in 119 C.E.: “he bestowed special honors upon his mother-in-law with gladiatorial games and other ceremonies” (Historia Augusta, Hadrian 9, Magie 1967–68). Along with the funeral oration, he honored her with coins with the label DIVA AUGUSTA MATIDIA (British Museum Collection III: p. 281, nos. 328–32), and erected to her a temple whose remains have been identified in the Campus Martius in Rome. And, making his motives ever clearer, he issued a significant coin on the obverse of which Trajan’s portrait appears with the label Divus Traianus, while the reverse shows Diva Plotina (Fig. 13.2); his claims to the throne are thus doubly secured by his wife’s lineage and by his own adoption, and he merits the throne as well by the pious honors he offers to his adoptive ancestors (Boatwright 1991a, and Temporini 1978).

In his lifetime, Hadrian’s adopted son and successor Antoninus Pius had honored his deceased wife Faustina (d. 141) with a temple in the Roman Forum, had instituted charitable donations to worthy girl children from the Italian countryside (puellae Faustinianae [Historia Augusta, Antoninus 8]), and had named her diva on coins. The emperors who follow become ever more encrusted with honors, ever more clearly godlike, and their wives participate in the process. As these honors escalate in number and hyperbole, the tension increases between traditional womanly reticence and self-effacement on the one hand, and honors, funeral orations, coins, portraits, benefactions, and titles on the other (Faustina the Younger’s honors: Dio 72.5, Historia Augusta, Marcus 26.8, Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 14.40, and BMC IV, nos. 700–705). By the time of Septimius Severus’s reign (197–211), the empress Julia Domna will be addressed as Mater Senatus (mother of the Senate: BMC V, clxxvi and cxcv ff.) and Mater Castrorum (mother of the military camps: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 8.26598, a title first used apparently for Faustina the Younger when she accompanied her husband Marcus Aurelius to his campaigns in the eastern part of the Empire in 175, as in Dio 72.5, Historia Augusta, Marcus 26.8). Automatically granted the title of Augusta, she represents the trend away from the earlier tradition of emperor and empress as first among equals; yet at the same time, her many titles and honors retain their connection to motherhood and the primacy of family.

Figure 13.2. Qold coin of Hadrian, minted after 122 in Rome. On the obverse (A) is the divinized Trajan; on the reverse (B) Diva Plotina. Hadrian used these images to construct his new divine family.

Only rarely does our evidence provide information about the occupations and interests of individual empresses, about their social and political influence, or about their daily lives. Whether they had public prominence or were seen as essentially modest and retiring, the empresses do seem to have exercised private influence; the evidence is, however, very spotty. Julia Titi, the daughter of the emperor Titus, nominated the consul for 84 C.E., according to the later historian Dio (67.4.2), and Vitellius’s wife, Galeria, about whom we also know relatively little, saved the consul Galerius Trachalus from execution in 68 (Tacitus, Histories 2.60.2).

Plotina, self-effacing as she may have been, is said to have given advice in domestic matters just as Livia and the other empresses had. Thus we hear that Trajan betrothed his grandniece Vibia Sabina to Hadrian, “Plotina being in favor of the match, while (he himself), according to Marius Maximus, was not greatly enthusiastic.” (Historia Augusta Hadrian 2.10). Another abridged collection of Imperial lives (Epitome de Caesaribus 42.21; trans. Elaine Fantham) reports that when Trajan let his officials extort from the provincials, Plotina “reproached him for neglecting his own good name … and as a result she made him detest unjust exactions.” This comment is interesting both for Plotina’s role as moral arbiter and for her concern with the world outside of the city of Rome.

The empress’ clear awareness of public matters in the provinces can be seen in a letter she wrote to Hadrian after Trajan’s death (117 C.E). Inscriptions in colloquial Greek record her formal request to the emperor on behalf of Popillius (head of the Epicurean school at Athens) as well as her letter to Popillius. In the damaged Greek inscription we can see her adherence to Epicurean doctrine as she speaks of the principles of “our school.” The letter to the emperor reads,

How much I am interested in the sect of Epicurus you know very well, Master. Your help is needed in the matter of its succession; for in view of the ineligibility of all but Roman citizens as successors, the range of choice is very narrow. I ask therefore in the name of Popillius Theotimus, the present successor at Athens, to allow him to write in Greek that part of his disposition which deals with regulating the succession and grant him the power of filling his place by a successor of peregrine status,1 should personal considerations make it advisable; and let the future successors of the sect of Epicurus henceforth enjoy the same right as you grant to Theotimus; all the more since the practice is that each time the testator has made a mistake in the choice of successor the disciples of the above sect after a general deliberation put in his place the best man, a result that will be more easily attained if he is selected from a larger group.

(Inscriptiones Latinae Liberae Rei Pablicae II. 7784.4–17; Alexander 1938: 161)

The interest of empresses in philosophical matters reappears in information about Julia Domna’s patronage of Philostratus and the suggestion that she was even called Julia the philosopher (Bowersock 1969: 103). Julia Domna, Dio says, also took care of petitions and letters for Caracalla when he was emperor, from 211 to 217, (Dio 78.18.2–3 and 79.4.2–3) and held public receptions for the most prominent men, just as did the emperor (Dio 79.4.2–3).

The empresses traveled extensively with their husbands, as we gather from reports (some much later and of questionable reliability) of Plotina’s being with Trajan at his death on campaign (Historia Augusta, Hadrian 5.9–10) and of Faustina’s having accompanied Marcus Aurelius (Dio 72.5). Sabina traveled with Hadrian to Egypt (ca. 130 C.E.) where her friend Julia Balbilla commemorated the visit and her own poetic skill in Greek epigrams on the thigh of the Colossus of Memnon. Despite her Roman name, Balbilla was a Greek noblewoman and her epigrams adopt the dialect and language of Sappho (who lived almost a thousand years before her!) In part of a poem to honor Sabina and the trip to Egypt, Balbilla also proudly identifies herself:

Memnon, son of Dawn and revered Tithonus, sitting before the Theban city of Zeus or Amenoth, Egyptian king, as the priests who know the ancient tales relate, Hail! and may you be keen to welcome by your cry the august wife too of the Lord Hadrian …

I do not judge that this statue of yours can perish, and I perceive within me that your soul shall be immortal. For pious were my parents and grandparents. Balbillus the wise and Antiochus the king, father of my father. From their line do I draw my noble blood and these are the writings of Balbilla the pious.

(Bowie 1990: 63)

Like many wives of Imperial governors, and like some of the Julio-Claudian women as well,2 the women of the later courts traveled into worlds far beyond the imaginings of the writers of the Twelve Tables whose laws placed such clear constraints on the mobility and autonomy of Roman women.

Pliny’s evocation of Plotina as a retiring and rather dull matron becomes more colorful when we see the evidence of the travel, the cultivated interests, and the interventions behind the throne of the empress; if she, the least flamboyant of her century, had such a cosmopolitan life, we must see Sabina, Faustina, and the others as at least comparable. This hardly means, however, that these were women who exercised the influence of Augustus’s empress Livia. Their lives were apparently more private, more involved with other Imperial women, with family and property, and with literary interests (Boatwright 1991a). The orator Fronto, teacher of the Imperial heir Marcus Aurelius, thought it appropriate to write the following cloyingly conventional birthday greeting to Marcus’s mother Domitia Lucilla using the Greek language. However, he was sufficiently in awe of her standards (or her standing) that he first asked his pupil Marcus to check the correctness of the letter (mid-second century, and see the earlier letter about women’s birthday celebrations in the introduction).

To the Mother of Marcus

Willingly by heaven, yes, with the greatest pleasure possible have I sent my Gratia (his wife) to keep your birthday with you, and would have come myself had it been lawful. But for myself … this consulship is a clog around my feet …

The right thing, it seems, would have been that all women from all quarters should have gathered for this day and celebrated your birth-feast, first of all the women that love their husbands and love their children and are virtuous, and secondly all that are genuine and truthful, and the third company to keep the feast should have been the kind-hearted and the affable and the accessible and the humble-minded; and many other ranks of women would be there to share in some part of your praise and virtue, seeing that you possess and are mother of all virtues and accomplishments befitting a woman, just as Athena possesses and is mistress of every art.

(Fronto, Correspondence 2.7; Haines 1962)

Although the empresses seem to have had a voice in discussions about the succession in the second century, that voice was far quieter than those of the Severan Julias. Kin of Julia Domna, the three Julias (Julia Maesa, Domna’s sister, and Maesa’s two daughters, Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea) determined the succession and removal of emperors. Soaemias’s son Elagabalus became emperor through the intervention of mother and grandmother, and was replaced by his cousin Alexander Severus, son of Mamaea, by the manipulations of his mother and grandmother; Julia Maesa remained at the center of the politics of the period from 211 until her death in 226: “When he [Elagabalus] went to the camp or the Senate-house, he took with him his grandmother [Julia Maesa] … in order that through her prestige he might get greater respect—for by himself he got none.” (Historia Augusta Elagabalus 12.2–3; Magie 1967–68)3

The intervention or “interference” of the Imperial women in state affairs was always seen as problematic by Roman writers. These men always see such involvements as inappropriate and dangerous, for the women are crossing gender boundaries that are meant to keep social order. Perhaps this is why they constantly elide political and sexual transgressions, for both create disorder. No matter how self-effacing the women of the court may have been, no matter what the official claims of their virtue, there seem always to have been rumors of incompatibility or scurrilous tales in circulation about Imperial sexual adventures. Hadrian’s wife Sabina may have been chaste, but like Plotina she was childless and “he would have dismissed his wife … for being moody and difficult, if he had been a private citizen, as he himself used to say” (Historia Augusta Hadrian. 11; trans. Elaine Fantham). Marcus Aurelius’s empress Faustina, daughter of his predecessor Antoninus Pius and mother of his many children “allegedly had once seen gladiators pass by and was inflamed with passion for one of them. While troubled by a long illness she confessed to her husband about her passion.” The same author goes on to intimate that Faustina’s son Commodus was actually fathered by a gladiator:

[H]er son Commodus was actually begotten in adultery, since it is reasonably well-known that Faustina chose both sailors and gladiators as paramours for herself at Caieta. When [the emperor] was told about her so that he might divorce her—if not execute her—he is reported to have said, “if we send our wife away, we must give back her dowry too”—and what dowry did she have but the empire, which he had received from his father-in-law when adopted by him at Hadrian’s wish

(Antoninus. 19; Birley 1976)

The political goal of this kind of gossip is obvious: the writer damages the reputation of the emperor in an environment where his inability to control his wife speaks worlds of his other inadequacies. A passage about Marcus Aurelius giving Imperial posts to his wife’s lovers is just such a piece of scandal (Historia Augusta. Antoninus 29) exploiting the spicy combination of sexual transgression and political interference. Unquestionably late, unreliable, and often profoundly silly, Historia Augusta (late third and fourth century) reveals the persistence of this standardized gossip about female transgression.

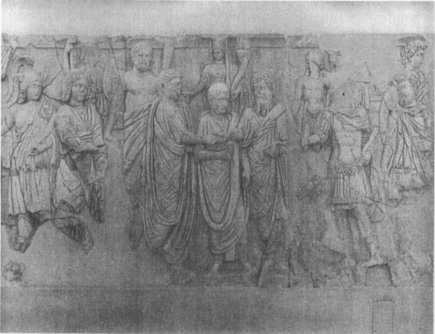

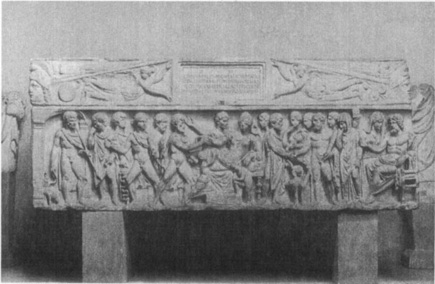

In contrast with such scandalous rumors, the representations of the wives of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius in state art and inscriptions provide us with a view of court women that more closely resembles the praise literature of speeches. Stressing marital loyalty (even a kind of affection) and dynastic duty, these monuments erase both the scandalous and the cosmopolitan elements of the lives of the empresses. The Column Base of Antoninus Pius, dated to 161 in Rome, shows the emperor and Faustina I ascending together to the heavens on the back of a strange youthful figure, a psychopomp or being who bears the soul away (Fig. 13.3). Just as the deceased Sabina is borne aloft on the back of an eagle on a relief (after 136–37) in which Hadrian sits watching, the apotheosis of Antoninus and Faustina suggests the marital harmony so important to the public self-representation of the Imperial family as family. Similarly, in the coins of Imperial couples that present husband and wife clasping right hands in a gesture (the dextrarum iunctio) associated with the concord of treaties and of marriage, the visual imagery of the state puts on parade a dutiful and harmonious couple. In fact, the public ideology of concord reached into the private realm (if we can even separate them by this modern polarization) when the senate decreed, on the death of Faustina II (175?), that “silver images of Marcus and Faustina should be set up in the temple of Venus and Roma and that an altar should be erected whereon all the maidens married in the city and their bridegrooms should offer sacrifice.” (Dio 72.31.1); they may be shown, on a coin, at the altar below the larger figures of the emperor and empress who join hands as Concordia brings them together (Reekmans 1957; Davies 1985).

Figure 13.3. Base of the Column of Antoninus Pius from Rome, erected around the time of his death, ca. 161 C.E. On the front is the apotheosis of Antoninus and Faustina, his wife, watched by the goddess Roma and the personification of the Campus Martius, the place where the funeral pyres of the emperors and their families burned.

The imagery of the good wife persisted, despite the scandal-mongering, in the state-sponsored public images for Faustina’s daughter, wife of their adopted son Marcus Aurelius. The coins associate Faustina the Younger with Marcus and their son Commodus (161–75 C.E.) and put her face on the obverse of coins whose reverses often show Felicitas (fruitfulness / good fortune), Felix Temporum (the prosperity of the era), Fecunditas (fertility) or Juno Lucina (protector of women in childbirth) with large numbers of children; the numbers and ages of the children seem to change with the births and deaths of the Imperial offspring (Fig. 13.4). The emperor and his wife thus emerge as the model not just of a dutiful but of a harmonious and fertile marriage: their domestication becomes the pattern of Roman marital harmony, as the state’s ideology penetrated the private once more (Fittschen 1982). This aristocratic image of marital concord has earlier models (see Chapter 12), but the Antonine dynasty appears to make the first broad public use of it. This may spring from the urge to win a more intimate loyalty from the empire’s people to their rulers as quasi-kinfolk; it may also indicate a state policy of reinforcing traditional (if reformulated) Roman concerns with domestic morality and reproductive responsibility. And as always, such visual ideology serves more powerfully than any speech or decree to remind people of the peace attending civil and dynastic stability.

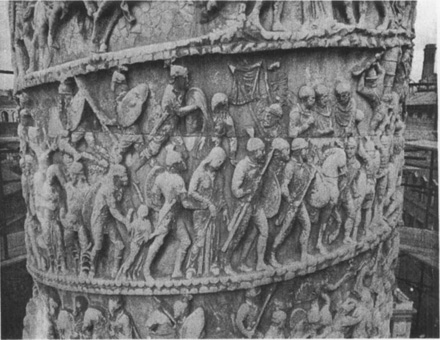

The most interesting and latest case of the construction of the harmonious Imperial family with its virtuous wife is also the most obvious in its political motives. Septimius Severus, the Roman general from North Africa who overcame other contenders for the Imperial throne after the civil wars at the end of the second century, married Julia Domna, a Syrian aristocrat whom the third century texts describe variously as dramatically beautiful, intellectual, long-suffering, adulterous, powerful, and dangerous (for example, Dio 78.18, Herodian 4.3.8–9, or Historia Augusta, Severus 21.6–8). They are frequently represented together with their two sons Geta and Caracalla (or in various combinations) from the early childhood of Geta until Septimius Severus’s death in 211. Gold coins show Julia, her heavy looped and braided hair identifying her immediately, with her two boys. The nearly adult sons appear with their parents (riding in their father’s carriage, watching their mother make a sacrifice, Caracalla shaking hands with his father as Geta stands between them and Julia Domna looks on approvingly) (Fig. 13.5) on the family arch set up in 206–9 to commemorate their visit to Septimius’s birthplace, Leptis Magna (in Libya). And finally, as adults, the sons joined their parents and Caracalla’s wife and father-in-law on the Arch set up by the moneychangers in Rome. The vast public imagery of the family was reinforced by the many statue-groups that graced town squares and temple precincts in all parts of the empire; a great series is preserved at Perge, the town from which at least one other major Imperial family group, Hadrianic in date, remains to indicate the way the Imperial family image structured the cityscape.

Figure 13.4. Coin of Faustina the Younger from Rome, ca. 161–176 C.E. The reverse (shown) carries the label Felix temporum, the happy future guaranteed by the woman and her six children, presumably the same number the empress had at the time the coin was minted.

Only when we notice the frequent erasure or destruction of the head of Geta is the fiction of the happy family exposed: Geta was murdered by his brother Caracalla when their father died in 211, and Caracalla then decreed that Geta’s image be removed from all monuments (a practice called damnatio memoriae, erasure of memory.) The blank space where Geta’s head had been (now replaced by a modern one) on the handshake scene of the Leptis Arch, like the empty place on the arch in Rome, reveals the importance of the family myth—and its fragility. Official representation used Julia Domna as a linchpin to create a family, and thus gave an empress a central place in dynastic iconography in order to insist on a legitimate past and secure future for the people of the Roman empire (Kampen 1991).

Figure 13.5. Relief with Septimius Severus clasping the hand of his son Caracalla as his second son Geta and his wife Julia Domna (second from the left) look on. The relief dates to about 206 C.E. and comes from the Severan family arch at Leptis Magna in modem Libya.

What we have been seeing is, first, the discrepancy between texts and visual images that results from their differing traditions and functions and so projects conflicting impressions of the empress. Second, despite changes over time in the way the empresses were depicted and honored, there remained a core of imagery tied to the traditional gendered virtues of the Roman elite; this they preserved and disseminated to the world at large. The women of the court, regardless of how sophisticated and complex they might have been, always are praised in terms of conservative domestic behavior. Finally, all our evidence points to the existence of a long-standing public discourse, going back to the time of Livia and Augustus, about the empress’s sexuality. When she is represented for state purposes, it is often because her image acts as an indication of the stable and happy future assured by her reproductive contribution to the dynasty. When she is reproached or slandered, it is through the use of her political interference as it is associated with murderous or adulterous desires and acts: sexuality and power go wrong together, and each is a sign for the other, for each is about the transgression of social boundaries essential to preserving the Roman order. This order in turn depends on an ideal womanhood, defined both by the praise of the empress as a norm and the condemnation of transgressions attributed to her. As the Roman world expanded, the empress’s image remained of value for social reproduction on a vast scale.

Women of Wealth

Like the women of the court, rich women throughout the Roman Empire appear to us through the veils of ideology, genre, and chance. Not only do we know them only as far as we have surviving evidence, evidence shaped by the conventions of each genre from praise literature and public art to gossip, but we also read them as texts written by a small number of people who construct them according to their own interests, and these are not always the interests of the women themselves. Adding to these complexities the expanse of the Empire compounds the problems we met in the discussion of the empresses, since now local traditions may intervene. Thus, regional ideals may modify the ideal of womanhood diffused throughout the Empire in part by the image of the empress; how much diversity there was remains difficult to assess because of the uneven and scattered evidence.

The same problems are generated by the random and probably unrepresentative evidence of the conduct of wealthy women. Thus, for example, Pliny the Younger’s letters (late first to early second century) tell us a good deal about the vocal and influential upper-class women of Italy who brought lawsuits to preserve their own interests (as when the embarrassed writer had to act on behalf of his mother’s old friend Corellia Hispulla in her suit against a very important man [Letter 4.17], or when he represented a mother who brought a criminal case against two freedmen she accused of poisoning her son and forging a will to make themselves his heirs [Letter 7.6]). In addition to being implicated in their fathers’ and husbands’ legal affairs (for example, Letter 3.9), Pliny tells us that women were called as witnesses in political cases and exerted pressure themselves (Letters 3.11 and 9.13).

By comparison with these and other cases Pliny recounts about his years in Rome, the mention of cases in which women were involved under the writer’s governorship in Bithynia (110–12 C.E.) are few; two concern men’s petitions that involve women and one is a request for the emperor’s permission to let the governor’s wife travel for family reasons (10.59, 10.106 and 10.120). Clearly the disputes that needed the emperor’s opinion were rarely initiated by women during Pliny’s governorship; these letters to Trajan over the course of approximately twelve months are all that Pliny has to tell us about the women in his Eastern province.

More useful than the novel of Apuleius, Metamorphoses, for information about the lives of women in his own homeland of North Africa, is the second-century author’s account in the autobiographical Apologia of the circumstances of his marriage to the mature widow Pudentilla. This stylized defense speech throws light on the differing attitudes and motives of a moneyed woman’s male relatives to the question of her remarriage. Prevented from marrying again by the greed of her father-in-law, who feared that her money would pass away from his grandchildren (her sons), the widow finally fell sick “injured by the prolonged inactivity of her sexual organs, and because the lining of her womb was inflamed she often came near to death with her pains. Doctors and mid-wives agreed that the illness had been brought on by deprivation of married life.… while she was still in her prime she should heal her condition by marriage” (Apologia 69; trans. Elaine Fantham). So Pontianus, her elder son, encouraged his friend Apuleius to marry her, but once Pontianus himself married, his new father-in-law pushed him to prosecute Apuleius as a fortune hunter who had seduced Pudentilla by witchcraft. Pudentilla herself does not appear in court. Instead, the prosecution argues from one of her letters (written in Greek) “Apuleius is a wizard: I have been bewitched by him into infatuation: come and rescue me, while I am still able to control myself” (Apologia 82; trans. Elaine Fantham). Apuleius in turn shows that the letter has been distorted by selective quotation, and restores the context to reinterpret the widow’s purpose: “now, as our vicious accusers would persuade you, Apuleius is a wizard and I have been bewitched.” Quoting her explicit affirmation of sanity and acceptance of marriage, Apuleius constructs his defense (83, 84). We see a shrewd and mature widow whose personal life has been first sacrificed to the greed of her own father-in-law, then threatened by the greed of a new male interloper—her son’s father-in-law. Such family disputes in which the woman is merely an acompaniment of the coveted money and property, and her marriage a matter of men’s self-interested manipulation, cannot always have been so lurid as the case Apuleius sets before us, but they persisted as a social injustice into the nineteenth century. Here in second-century Africa the educated and articulate Pudentilla does not appear as a witness to confirm her intentions, but must depend on her new husband to represent her in the courts.

Far more widely distributed evidence about women of wealth and influence comes from the inscriptions of the Roman Empire. All over the Empire and in diverse communities women functioned as benefactors and participants in the public world and used their money to enhance their own and their families’ prestige and to fulfill social and religious responsibilities (Nicols 1989). Among the most interesting samples are inscriptions on public buildings and statue bases that tell of the patronage given and honors received by women in many parts of the Empire. For example, from a synagogue in Asia Minor comes a third-century inscription in Greek for Tation who helped finance the construction and decoration of the building:

Tation, daughter of Straton, son of Empedon, having built with her own money this hall and the court enclosure, made a gift of it to the Jews. The Jewish community honored Tation … with a wreath and the right of precedence.

(Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum 2.738; trans. Natalie Kampen)

These inscriptions, naming women of prominent families, including women of the court, also provide an important source of information about gender ideals and practices among the elite of the municipalities and provinces for which no literary evidence survives. Since they are meant to honor the benefactor as much as the recipients, their emphasis is on the social aspects of good character and family and on public material contributions rather than on domestic virtues.

Women of important families gave donations and patronage to the districts where their estates were located, to their birthplaces, and to regions where their own religious responsibilities or their husbands’ political duties took them, as indicated by the following inscription (abbreviations expanded from the inscription are indicated by lower-case letters):

TO CASSIA

CORNELIA

PRISCA Daughter of Caius, Most distinguished Lady

WIFE OF AUFIDIUS FRONTO Consul, Pontifex,

PROCOnsul of ASIA, PATRON OF THE COLONY

PRIESTESS OF AUGUSTA

AND OUR FATHERLAND.

THE PEOPLE OF FORMIAE

gave this base PUBLICLY IN RETURN FOR THE BRILLIANCE

OF HER GENEROUS BENEFACTION.

This late second-century inscription on a statue base from Formiae on the coast south of Rome honors a lady of the senatorial class in terms of her own gift, but it defines her identity by her husband’s Imperial magistracy and local patronage before mentioning her own religious office. Other evidence shows that she was in fact the granddaughter of Cornelius Fronto, tutor of Marcus Aurelius (see above). Her priesthood serves Augusta, the empress Julia Domna, and Patria “the native land,” not an Italian title or local to Formiae but almost certainly conferred on her by a Greek civic community in Asia while her husband was governor, the most prestigious senatorial office he could hold. Italian and Greek, public and private, personal and marital honors are combined in this inscription (Année Epigraphique 1971: 34; trans. Elaine Fantham), one of many that could be cited.

Inscriptions permit reconstruction of the long-standing traditions of public benefactions and patronage of wealthy women; both civic and religious honors were granted them in the eastern and western provinces (Nicols 1989, and Forbis 1990). From Utica in North Africa an inscription of the late second or early third century associates the wife and young daughters of the Proconsul Accius Julianus with him as patrons of the community, no doubt in order to guarantee continuity of patronage when the women outlived the middle-aged consul. The women share the senatorial honorific of their husband and father:

TO L. ACCIUS IULIANUS ASCLEPIANUS, MOST DISTINGUISHED MAN,4 CONSUL AND CURATOR OF THE COMMUNITY OF UTICA

AND TO GALLONIA OCTAVIA MARCELLA, MOST DISTINGUISHED LADY, HIS WIFE

AND TO ACCIA HEURESIS VENANTIA, MOST DISTINGUISHED YOUNG WOMAN

AND TO ACCIA ASCLEPIANILLA CASTOREA, MOST DISTINGUISHED YOUNG WOMAN

THEIR DAUGHTERS. THE COLONY IULIA AELIA HADRIANA AUGUSTA OF UTICA

MADE THIS DEDICATION TO THEIR PERPETUAL PATRONS.

(Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 8.1811;

trans. Elaine Fantham)

In Africa and central Italy women received the extraordinary status of civic patrons, and in Egypt a woman was named “father of the city” in a move that demonstrates the extent to which the occupation of a public role could confuse gender titulature (Sijpestein 1987: 141–42). The extent to which these honors carried any rights to membership in town councils or to the holding of other public offices remains unclear; the third-century jurist Paulus says that women may not hold civil offices (Digest 5.1.12.2), but contemporary inscriptions from Roman Greece and Asia Minor mention women officeholders, including magistrates (Pleket 1969). This is the well-documented case with Plancia Magna of Perge, on the coast of Asia Minor, around 120 C.E. (Boatwright 1991b). The daughter of a senator who had given the City Games and had been rewarded with the title of city founder, Plancia held several important public positions such as demiourgos, the magistrate whose name was used to identify the year; she also held a major religious position, as the inscription on the base of a statue erected by the community tells us:

PLANCIA MAGNA

DAUGHTER OF MARCUS PLANCIUS VARUS

AND DAUGHTER OF THE CITY

PRIESTESS OF ARTEMIS

AND BOTH FIRST AND SOLE PUBLIC PRIESTESS

OF THE MOTHER OF THE GODS

FOR THE DURATION OF HER LIFE

PIOUS AND PATRIOTIC.

(Année Epigraphique 1965, no. 209; trans. Elaine Fantham)

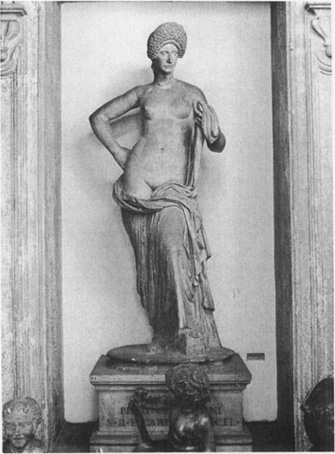

Plancia Magna gave to the city a monumental entrance-gate, parts of which still survive as do a number of its inscriptions and the graceful draped statue of Plancia (Fig. 13.6) that was one of many to decorate the gate. Included among the statues and Greek and Latin inscriptions were the deified Nerva, the deified Trajan and Marciana, the still-living Plotina and Hadrian, and also Plancia’s father and other members of her family and the community of Perge. Paying homage to the Imperial family as well as to her own blood and community family, Plancia used a traditional iconography of cult and kinship to foster the continuing success of her family (Boatwright 1991b).

Figure 13.6. Portrait of the municipal priestess and patron Plancia Magna of Perge, Asia Minor, dated to about 120 C.E.

Women like Plancia Magna or Cassia Cornelia Prisca (both second century C.E.) clearly controlled a substantial private fortune and shared in the ideology of public service for public glory that seems to have motivated generations of Roman men. Even in the Republican period before women had legal power to give away money, the provincials of Greece and Asia had honored governors’ wives with statues most probably in thanks for intercession with the governor in local issues. Now the practice was extended to the wives of local magnates as a routine response to benefactions and incentive to their continuation. There is no reliable way of estimating how many women of the Empire received honors from communities in the form of statues and inscribed bases, nor how many gave and on what scale, but the evidence points to a clear connection between honors and the importance of a woman’s family (Van Bremen 1983). Women who were chosen as priestesses may not have exercised power in any political sense, but they resembled benefactors in the sense that their public functions did bring them a certain prestige and authority. It was usual in the upper classes for women to be chosen as priestesses; their offices might be little more than a political compliment, as was the case for Cassia Cornelia Prisca, or they could mean a long-term renunciation of domestic life. The Vestals continued throughout the Imperial period to have social and religious importance, and their portrait statues, ranging in date from the second to the fourth century, can still be seen not only in the museums of Rome but also near the house of the Vestals in the ruins of the Roman Forum.

In the Greek part of the Roman Empire, women of “good” family might combine their secular lives with honorific services as priestesses, like Plutarch’s friend Clea, priestess of Delphic Apollo. From Plutarch’s dedications to Clea of his essays, “On the Bravery of Women” (see below) and “On Isis and Osiris” (late first or early second century), it is clear that she was a learned and revered lady, more like a city councillor or committeewoman than the inspired prophetesses whom we associate with Delphi.5 Oracles of Apollo, especially in Roman Asia Minor, did have power in that they often determined which women became priestesses. Even priestesses of Athena might be appointed by an oracular decision of Apollo. These priestesses were celibate, but an inscribed oracle from Miletus (late second to early third century C.E.) appoints a widow, Satorneila, the mother of two grown sons:

Late, O townsmen, concerning a priestess of Athena

have you come to hear the divine inspired voice—

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

for it was necessary that the honor of the priesthood of the self-appearing maiden

be received by a woman with the blood of noble ancestors

but after she had previously obtained her share of the gifts of Aphrodite,

for the Cyprian goddess vies with virgin Athena,

since the one is uninitiated in love and the bride chamber,

but the other rejoices in marriage and melodious bridal songs.

Accordingly, in obedience to the fates and and to Pallas,

appoint chaste Satorneila as holy priestess.

(Drew-Bear and Lebek 1973)

Priestly offices may, then, have been a way to honor and reward a benefactress, or they may have provided income for needy women or past priestesses in a community (Gordon 1990).

The picture of women’s political participation through honors, patronage, and officeholding comes to us from the inscriptions and the odd literary passage as a positive, praiseworthy phenomenon. Fathers, husbands, and sons may be named (they usually are) or unmentioned, but what we see is an indication of the public functioning of wealthy upperclass women. This is true as well for freedwomen with money who were to be found in Italy as patrons for local craftsmen’s guilds; these patrons are often named mater, as for example Claudia, the wife of a freedman from Faleri Piceni, who is called “mother of the brotherhood of fullers” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 9.5450, undated; trans. Natalie Kampen). These inscriptions suggest the blurring of lines between public and private; for example, a third-century freeborn woman from Sentinum, Memmia Victoria, whose son was a local officeholder (decurio), was named mater of an artisans’ group (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 11.5748).

Women play public roles through private wealth, they enter public consciousness although they are private citizens unable to vote or (apparently) hold office in government, and they influence public events through acts of generosity that keep the men of their families in the public eye as potential officeholders. At every level in the upper classes, from Julia Domna’s patronage of the rebuilding of the temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum to the financing by Ummidia Quadratilla of Casinum’s temple and amphitheatre, women demonstrate the ambiguity of the terms “public” and “private” for the Roman world. And the inscriptions demonstrate as well the possible differences that social status and region can make to women’s lives even as they cling to the traditional list of feminine virtues.

Autonomy and Ambivalence

By comparison with the evidence from inscriptions, the comments of male authors on the (relative) autonomy of women seem striking in their ambivalence. The discussions about the education of wives that appear in the writings of Juvenal, Pliny, and Plutarch, all writing around 100 C.E. offer a picture of what in women’s lives and character most irritated, enraged, and provoked laughter among Roman (and Greek) men of a certain class and what they envisioned as the solution.

Yet a musical wife’s not so bad as some presumptuous

flat-chested busybody who rushes around the town

gate-crashing all male greetings, talking back straight-faced

to a uniformed general—and in her husband’s presence.

She knows all the news of the world

(Juvenal, Satires 6.398–403; Green 1967)

if she’s so determined to prove herself eloquent, learned,

she should hoist up her skirts and gird them above the knee

scrub off in the penny baths.6 So avoid a dinner partner

with an argumentative style, who hurls well rounded

syllogisms like slingshots, who has all history pat:

choose someone rather who doesn’t understand all she reads.

I hate these authority citers, … who with antiquarian zeal

quote poets I’ve never heard of. Such matters are men’s

concern

(Juvenal Satires 6.445–52; Green 1967)

The classical solution to such autonomous behavior is suggested by the Roman Pliny and his Greek contemporary Plutarch, since both wrote of women’s education in ways designed to overcome the undesirable characteristics Juvenal so gleefully skewers. Pliny writes (early second century) of his joy in his sweet young wife’s love for his work;

Because of her love for me, she has even gone so far as to take an interest in literature; she possesses copies of my writings, reads them repeatedly, and even memorizes them.… When I recite from my works, she will sit nearby, behind a curtain, eager to share the praise I receive. She has even set some of my poems to music, and chants them to the accompaniment of a lyre, untaught by any music-teacher, but rather by the best of teachers, love.

(Pliny, Letters 4.19.2 and 4; Radice 1975)

Plutarch, even as he mentions casually in his Advice to Bride and Groom (late first to early second century) that his wife Timoxena composed an essay for a friend against the use of cosmetics, advises his friend Pollianus, to whom his own essay is addressed, to educate his wife by oral instruction:

As for your wife, you must collect useful material from every source, like the bees, and carrying it in your own self share it with her and discuss it with her, making the best of these doctrines dear and familiar to her. For to her

Thou art her father and lady mother

yes, and a brother too [quoting Iliad 6.429]

This kind of study … diverts women from absurd conduct; for a woman studying geometry will be ashamed to dance, and she will not swallow any beliefs in magic spells while she is under the spell of Plato’s or Xenophon’s arguments.

(Plutarch, Advice to Bride and Groom 145c–d; trans. Elaine Fantham)7

Looking back over our evidence about the roles played by women of the privileged classes and about the reaction of our various sources to women’s public activities, there is a constant tension throughout this period of more than two hundred years between female autonomy and achievement and male response. Often the discomfort of Roman writers in the face of public and political roles for women is palpable. Both within the court (as in the stories of Plotina’s intervention to ensure that Hadrian was made Trajan’s successor: Historia Augusta, Hadrian 4.4 and 4.10) and outside (as when governors’ wives are portrayed as seeking power), power is condemned as inappropriate precisely because it is political. Yet throughout the Empire, inscriptions congratulate women for their generous use of private and family money for the public good, and the political implications for gaining authority and power for women seem to pose no problem. From the evidence we may draw two conclusions: (1) female political interference, like sexual misconduct, transgressed socially acceptable boundaries for upper-class life, no matter how common it was; and (2) there were alternative, socially acceptable frameworks for elite female autonomy, varying throughout the Empire but consistent in valuing public benefaction and religious service. In the end it is the contradictory and uneven nature of the evidence itself that poses the greatest problem for us in understanding the lives of elite women in the last centuries of the Roman Empire.

Gender and Social Position: Problems of Definition

The lives of women outside the world of grand families, social authority, or large-scale patronage are known to us through evidence that is even more scattered and inconsistent than what remains about elite women. Even the way we speak of this group is plagued by uncertainties. Should these women be called “lower class?” Is there such a thing as a homogeneous “middle class” of freeborn and freed slave artisans, businesspeople, minor priestesses, and professionals? Does it cross geographical boundaries and look the same in city and country, in east and west?

Where, for example, should we place an exceptional figure like Pamphila of Epidaurus in Greece? Our sources tell us that she came from Egypt and was the daughter of one scholar, Soteridas, and the wife of another with whom she lived at Epidaurus about the time of Nero (mid-first century C.E.); she composed some thirty-three books of historical materials (Hypomnemata Historika), which a certain Dionysius and other male scholars characteristically ascribed either to her father or her husband. She also composed epitomes of Ctesias’s histories (more than five hundred years old by that time) and treatises “On Disputation,” “On Sexual Desire,” and other topics. Luckily the bare notice in Suda, the tenth-century encyclopaedia, can be amplified by Pamphila’s own introduction to her work as reported by the Byzantine anthologist Photius (ninth century):

She says that after thirteen years of living with her husband since she was a child, she began to put together these historical materials and recorded what she had learned from her husband during those thirteen years, living with him constantly and leaving him neither night nor day, and whatever she happened to hear from anyone else visiting him (for there were many visitors with a reputation for learning). And she added to this what she had read in books. She separated all this material that seemed to her worthy of report and record into miscellaneous collections, not distinguished according to the content of individual extracts, but at random, as she came to record each item, since as she says, it is not difficult to classify extracts, but she thought a miscellany would be more enjoyable and attractive.

(Photius 175 S 119b; trans. Elaine Fantham)

Photius adds condescendingly that her style, shown in the prefaces and other comments, was “simple, being the work of a woman,” like her thought itself. Yet this extensive work was still used and quoted with respect by antiquarians a century or more after her death. Noble in her learning, child, wife, and friend of scholars, is Pamphila noble in social standing or would we today consider her to be a member of the cosmopolitan middle-class intelligentsia, those who might live in several parts of the Empire during the course of their lives? Is there anything particularly Greek (or Egyptian) about her life? To have been part of a world of learned visitors, with a library at hand, suggests a degree of prosperity that may or may not accompany noble birth or official standing in Greece of the first century C.E.

Once we leave behind the society of the court, and the great landowners with inherited wealth and power, we must imagine the communities of the Empire as mosaics of all kinds of people ranged along continua determined by ethnic, linguistic, financial, legal, and occupational variables, not all of which have analogies in the modern world. To this must be added once again the fact of geographical diversity. Although women of the highest social classes in all parts of the Empire probably shared a rather cosmopolitan life, just as they seem to have been equally subject to conservative norms of gender, this was not necessarily always the case for other women. Not only affected by regional differences, these women will have experienced the world differently inside each region according to their status, income, and the degree of Romanization prevailing in their area.

Tombstones, Social Ideals, Social Realities

The ideal of Roman womanhood, as we have seen it in the context of depictions of upper-class women, certainly played a role in shaping representations of women elsewhere, but there are clear differences in the way this worked. For example, the sexual division of labor—domesticity for women, outside occupations for men—seems to have determined the roles and character attributes that most lower-class families commemorated in women’s funerary monuments all over the Empire; the deceased are represented with their families and described in the vocabulary of traditional domestic and feminine virtues: one wife is mourned as “the best and most beautiful, a wool-worker,8 pious, modest, thrifty, pure and home-loving” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.11602 [undated]; trans. Natalie Kampen). This kind of representation is usually found on funerary reliefs, the modesty of whose form and content indicates recipients outside the wealthy classes. The majority of these stelai give only names and ages, but a good many offer other information as well.

To the spirits of the dead. T. Aelius Dionysius the freedman [auc. lib.?] made this while he was alive both for Aelia Callitycena, his most blessed wife with whom he lived for thirty years with never a quarrel, an incomparable woman, and also for Aelius Perseus, his fellow freedman, and for their freedmen and those who come after them.

(Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.10676 [from Rome undated, but possibly

second century, C.E.]; trans. Natalie Kampen)

Thus, mixed in with formulaic statements of respect and affection such as “she is worthy of commemoration [bene merenti]” or that she lived with a husband without quarrels [sine ulla querella], we learn a bit about relationships and demographics. An interesting case of rich detail comes from Rome and tells about Valeria Verecunda, the first important doctor in her neighborhood, who lived thirty-four years, nine months and twenty-eight days; her daughter Valeria Vitalis made the monument for “her sweetest mother” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.9477 [34th century, C.E.]). The deceased may be honored not only by her immediate family but also by fellow slaves, an owner or patron, or fellow freedmen and women. All this conforms to our understanding of familia in the Roman world as conceptually broader than the modern nuclear family. Slaves and freedpeople often constructed family for themselves both from the families of their owners and from each other as a parallel to the ties of duty and affection in free families, and the use of such terms as collibertae, “fellow freedwomen,” or contubernales, “companions in slavery” marks these relationships (Lattimore 1942).

Themes of affection and of praise for much-loved mothers, for sweet-natured and well-educated little girls, and for chaste and unquarrelsome wives are common all over the Empire. The inscriptions from Rome and large provincial towns parallel in words the repeated images on tombstones from such far-flung regions as Phrygia in Asia Minor. There, and to a lesser extent in Italy too, combs, cosmetic jars, hairpins, and sandals stand next to wool baskets, spindles, distaffs, and needles, and to keys and lockplates, to evoke the combination of personal beauty and domestic duty, wool-work and protection of the house and its contents (Fig. 13.7). Some of the Phrygian stones pair husbands’ symbols with those of the wife to show the sexual division of labor in visual form: his objects may be scrolls and tablets, sheep and oxen, metal tools or construction materials. In other words, his imagery is more varied and concerned either with literacy as a mark of status or officeholding, or, through the use of attributes, with a money-earning occupation (Waelkens 1977). Beauty and domestic labor for women; culture and occupational identity for men.

The iconography of virtue among those prosperous enough for tombportraits indicates a similar tradition of gender differentiation. Women’s funerary portrait statues, and this is true in reliefs and sometimes too in the choice of myths for sarcophagi, show a clear preference for Venus (love and beauty) (Fig. 13.8), Ceres or Salus (fertility), Diana (Virginity and Courage) and Hygeia (Health), whereas men prefer Mars (war), Hercules (strength), and Mercury (money-making). The message is conveyed through the use of the odd, very Roman combination of identifiable portrait heads with contemporary hairstyles and bodies copied from famous Greek statues of the gods. These funerary portraits, mimicking the use by the Imperial family of portraits in the guise of deities, were popular in the tombs of the later first, second, and early third centuries of our era; the evidence suggests that their patrons were mostly wealthy freed slaves and that the practice tended to be localized in Rome. To have a large-scale portrait statue that uses the formal typology of the grand Greek tradition was certainly to have pretensions to wealth and culture! (Wrede 1981).

Figure 13.7. Tombstone from Dorylaion in Phrygia, an inland section of Asia Minor. Dated to the late second or early third century C.E., it places the objects associated with men’s and women’s lives into twin doors, perhaps doors to the next world or to the house of the deceased.

Pretensions to culture can also be seen in the sarcophagi that become popular in Italy and the East after about 130 C.E. Sometimes the deceased or her family chose a design and had it made to order, or bought a partially completed piece and had inscriptions and portraits added; in either case women’s and men’s virtues are represented (though differently) through the use of divine and mythological imagery. A good example is the sarcophagus of Metilia Acte from the late second century C.E. in Ostia (Fig. 13.9). She was a priestess of Magna Mater, her husband a priest; the sarcophagus shows them as Alcestis and Admetus, she who volunteered to die instead of her husband and whose virtue was rewarded by her return to the living. Here both loving devotion and hopes for victory over death appear, and Metilia receives a heroizing commemoration through the appropriation of myth (Wood 1978). Similarly ostentatious monuments to the dead, like the sarcophagi of Asia Minor, in the third century C.E., show men as philosophers, women as muses, and both as readers—cultured people. We thus see the virtues that were considered most appropriate for women and men and the way these reinforced and expressed social expectations that were rooted in a gendered division of labor.

Figure 13.8. Tomb statue of a woman following the model of an earlier Greek statue of Aphrodite, perhaps one such as the “Venus de Milo.” This portrait from Rome of the later first or early second century C.E. uses the artistic connections to assert noble virtues of the deceased, who is presented as Venus.

Figure 13.9. Sarcophagus of Metilia Acte and her husband Junius Euhodus, from Rome in the third quarter of the second century C.E. The centralized composition focuses the viewer’s eye on the dead woman, reclining on her couch; the narrative elements on either side explain the death of Alcestis in her husband’s place (on the left) and her virtue rewarded by her return from the dead (on the right).

Most funerary images for nonaristocratic women were much simpler and less expensive, resembling the majority of commemorative inscriptions in that they choose to display family rather than gods or myths. In almost every part of the northern and western provinces and Italy, and some parts of the east as well, we find reliefs, ash urns, and altars with husbands and wives, children and parents, facing the viewer as if caught by a nineteenth-century photographer in all their stiff dignity. A family group on a stele made for residents of Dacia (modern Romania) (Fig. 13.10) resembles those of soldiers from Britain, although style and frame differ; in Aquileia in northern Italy another family looks out as silently as one from a painted stele in Thessaloniki in northern Greece. The traditions for such family images go back to the funerary stelai of Classical Athens as well as to Republican Rome, and remain alive as a favored setting for women of the “lower classes” in the Imperial period.

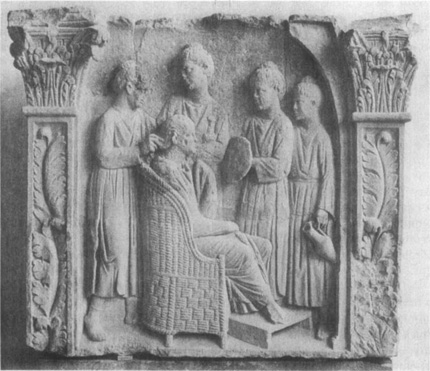

Some tombstones in the provinces that show women with families provide a sense of regional differences as well as similarities. Although few offer visions of worlds outside the context of family and domestic labor, there are bits of evidence for variation in the degree to which women assimilated into Roman ways. The tombstones show interesting distinctions between the eastern and western provinces through artistic traditions and the use of Greek names and language rather than the Latin of the West. But in addition, the tombstones of some more remote areas, away from coasts, cities, or trade routes, indicate that a number of women may have kept indigenous names, costumes, and customs even after men of their social stratum had taken on Roman ways. The evidence does not permit any statistical conclusions here since the tombstones that remain with both inscriptions and images are few and limited to those people who were prosperous enough to have tombstones and Romanized enough to want them with Roman words and decoration. Umma, a first-century woman from Noricum (modern Austria), wears a splendid local-style felt hat (Fig. 13.11) that goes with her non-Roman name, and other women in the northern and western provinces sometimes wear local brooches or carry local baskets or purses. Local taste is also evident in the large funerary monuments of wealthy merchants near Trier in Germany; many show family portraits and men hunting, but they include panels with the deceased in his place of business while his wife, seated in a local wicker chair on another part of the monument, is prepared for the day by her hairdresser and other attendants (Fig. 13.12). These late second- and third-century tombstones of a richer and more assimilated group nonetheless show their sexual division of labor (her inactivity brings him status) in localized forms.

Figure 13.10. Stele of a family from Roman Sarmizegetusa in Dacia, a province along the Danube, dated to the second or third century C.E.

The little we know about women in the provinces comes mainly from these many kinds of tombstones, from their rare petitions reported in the codes of Imperial law, from the odd references to a local issue in need of a governor’s attention, and from the broad context of changes in the empire. These changes came not only from conquest but from the entrance of soldiers and merchants into new areas (especially the non-Hellenized northern provinces). Intermarriage is hard to track and harder still to quantify, but two laws will certainly have accounted for a growth in the marriages of Roman citizens from all over the Empire with local women. One was Septimius Severus’s permission for soldiers who served twenty-five years to marry (Herodian 3.8.4 [first half of the third century]); this regularized some relationships between local women and the troops stationed on the frontiers of Empire. The second, and by far the more important law, was Caracalla’s edict of 212 that made all free residents of the Empire full citizens with the right to contract legal marriages. How much these new laws changed women’s lives in the provinces remains uncertain because the evidence has to be extrapolated from names and biographical data on tombstones such as we have described, but the impact on their sons, now eligible to serve in the army, and their daughters, now able to marry soldiers, would have meant some changes in patterns of mobility and Romanization. Nevertheless, inscriptions, reliefs, literature, and other testimonia for provincial women both before and after 212 remain firmly rooted in a gendered ideology and division of labor, and the tombstones continue to represent women with families and the signs of traditional domestic labor and virtue.

Only a minority of nonelite Roman women were represented in other forms by inscriptions and visual images, and these differ from one another according to region as well as class: though small in numbers, they raise fascinating questions about the social constraints and possibilities of gender and class in this period. There are a number of inscriptions and a far smaller number of reliefs or paintings that characterize women by work outside the house (Kampen 1981). Dating most of this material presents enormous problems to scholars, since so few of the inscriptions vary from formula and so many have no archaeological provenance that could add to the information deducible from spelling and letter forms; for this reason, we give almost no dates for the inscriptions we discuss here.

Figure 13.11. Tombstone of a woman named Umma, who lived in first-century C.E. Noricum (modern Austria). Her magnificent fur hat, like her name, testifies to the continuing presence of local customs, even after the process of Romanization had begun.

Figure 13.12. Funerary monument from third-century C.E. Neumagen, near Trier; like so many of the tomb markers in this area of Gallia Belgica, the “Eltempaarpfeiler” made for a merchant and his wife took the form of a tall structure decorated with portraits and scenes of everyday life. This detail shows the matron attended by her servants.

Among the inscriptions we find references to net-makers, including one who made gold nets, perhaps for women’s hair: “Viccentia, sweetest daughter, maker of gold nets, who lived for nine years and nine months” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.9213 [undated]; trans. Natalie Kampen). We also see fabric and clothing workers (such as Lysis the mender or sarcinatrix from Rome who was described as being eighteen years old, thrifty and modest: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.9882), dyemakers and perfumers, and vendors of fruit and vegetables. Many of these inscriptions name the women’s kin, age, status, and sometimes even the locations of their shops:

To the Spirits of the Dead. For Abudia Megiste the freedwoman who was most pious, M. Abudius Luminaris her patron and husband made [this monument]. She was most worthy [bene merenti]. She dealt in grain and beans at the Middle Stairs [wherever they were]. Her husband made this monument for himself and his freedmen and freedwomen and heirs and for M. Abudius Saturninus his son who belonged to the senior Esquiline tribe [a sign of social status] and who lived eight years.

(Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.9683 [from Rome, undated];

trans. Natalie Kampen)

The woman on a small relief, probably from the second century C.E., from Ostia (Fig. 13.13), Rome’s port city, appears surrounded by the produce and game she sold; even though we know nothing about her identity beyond her occupation, the specificity of the objects lets us know what the patrons of the relief felt was most important. For the working women of our inscriptions and images, as for the people whose lives take symbolic form from the tools and attributes of their lives on Phrygian tombstones, the naming and the representing of things, beans and chickens, wool baskets and mirrors, become a way to identity.

Little information remains about the qualifications and training of workers, although two categories of material are helpful here. The first comes from manuals such as those written about medical practice. In the Gynecology of Soranus,9 written in Greek in the second half of the first century C.E., one can find instructions for midwives and information about their qualifications; Soranus says the best are trained in theory as well as in all branches of therapy, can diagnose and prescribe, and are free of superstition (Soranus, Gynecology 1.2.4; Temkin 1956). Soranus also gives information about the qualifications of wet nurses. His description of the ideal wet nurse, that she be in her prime and have given birth two or three times, insists on the need for experience with children as well as specific physical qualifications (Bradley 1986). He lists emotional characteristics such as self-control and sympathy:

Figure 13.13. Small marble shop relief of a saleswoman from Ostia, dated to the mid-second century C.E. Cages of chickens and rabbits form the counter on which are a basket for live snails and two monkeys for the entertainment of customers and passersby.