In a grand house on the Bay of Naples, with servants tumbling over one another, luxury dripping from every wall, table, and couch, a banquet is being conducted among the extremely nouveaux riches. The lady of the house, Fortunata, the wife of the freed slave Trimalchio, is not eating: “not even a drop of water does she put into her mouth until she’s arranged the silver and divided the left-overs among the slaves” (Petronius, Satiricon 67.2; Arrowsmith 1959) Despite her domesticity, she draws less than universal admiration to herself; as someone at the banquet tells his neighbor:

… that’s Fortunata, Trimalchio’s wife. And the name couldn’t suit her better. She counts her cash by the cartload. And you know what she used to be? Well, begging your honor’s pardon, but you wouldn’t have taken bread from her hand. Now god knows how or why, she’s sitting pretty: has Trimalchio eating out of her hand. If she told him at noon it was night, he’d crawl into bed. As for him, he’s so loaded he doesn’t know how much he has. But that bitch has her finger in everything—where you’d least expect it too. A regular tightwad, never drinks, and sharp as they come. But she’s got a nasty tongue; get her gossiping on a couch and she’ll chatter like a parrot.”

(Satiricon 37.2–7; Arrowsmith 1959)

Rich, vulgar, yet practical, Fortunata comes into focus both through Petronius’s words, written about the time of Nero (ca. 65 C.E.) and through the preserved marvels of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the other towns of the Bay of Naples that were suffocated by ash and lava in the great eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 C.E. (Fig. 12.1).

The excavation of these towns since the eighteenth century has permitted a clearer view of the lives of Roman women of every social stratum. Rather than dealing primarily with the texts of great authors, a discussion of women at Pompeii draws on inscriptions, architecture, painting, and the bits and pieces of daily life. At Pompeii and Herculaneum, not only can one see the food in bowls still on the table, find the jewelry women wore, study the decorations for their houses; one can even hear some of their stories.

Figure 12.1. General view of the city of Pompeii.

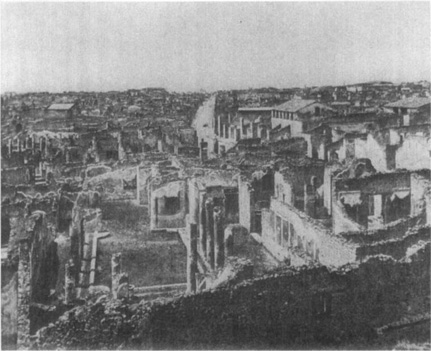

At the opposite end of the social ladder from Fortunata were such wealthy and aristocratic women as Nero’s wife, Poppaea Sabina, who had inherited property at Pompeii; like other aristocratic women with great villas around the Bay of Naples, she owned this property in her own right. Inscriptions on lead plumbing pipes like those found in the sea off nearby Puteoli testify to the ownership of villas by rich women; the sisters Marcia and Rufina Metilia (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X.1905) are a case in point. Their villas, like the well-preserved one that may have belonged to the empress Poppaea at Oplontis, just outside of Pompeii, had great gardens, extensive and richly decorated rooms of all sizes, even pools (Fig. 12.2). Although no evidence remains to indicate the empress’s personal involvement in the arrangements and furnishings of the villa, Oplontis gives a splendid indication of the style to which people such as she were accustomed (De Franciscis 1975). Their villas and houses, with wall paintings, mosaic floors, statuary and bibelots, resemble those of the rich hellenistic merchants of Delos (see earlier) more than the modest houses of Classical Athens; the parallel to the way the female owners themselves differed from Athenian women, perhaps now comparable to Hellenistic queens, is striking.

Figure 12.2. View of the villa (possibly belonging to Poppaea, wife of Nero) at Oplontis, outside of Pompeii. Dating to the middle of the first century C.E., the luxurious villa had long colonnades that gave onto gardens, as well as large numbers of richly painted interior spaces.

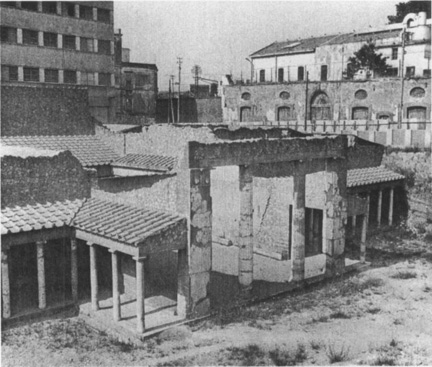

In the upper stratum of local Pompeian society, perhaps a step below that of the great ladies of the aristocracy, were other women who chose to use their wealth for the public good as well as for their own purposes. One of the most famous of these is Eumachia who, in the years before the earthquake of 64 C.E., paid for the construction of a huge public building in the most important spot in Pompeii, the Forum (Fig. 12.3). Around it were the markets, law courts, and temples of the town, and there the gathered populace might read on the building the inscription: “Eumachia, the public priestess (of Venus), daughter of Lucius, had the vestibule, the covered gallery and the porticoes made with her own money and dedicated in her own name and in the name of her son Marcus Numistrius Fronto, in honor of the goddesses Concord and Augustan Piety” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X.810, mid first century C.E.; trans. Natalie Kampen). A statue showing her in the usual pose and costume of a respectable matron (Fig. 12.4) stood in the building as a result of the generous gratitude of the cloth-cleaners; their inscription reads, “To Eumachia, the daughter of Lucius, the public priestess, from the fullers” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X.811; trans. Natalie Kampen). Argument continues about the uses to which the building was put, textile warehouse, auction house, cloth-merchants’ guildhouse, or even public meetinghouse; only Eumachia’s role as sole patron is beyond dispute, as the inscription indicates (Moeller 1972: 323–27).

Figure 12.3. View through the main entrance into the building underwritten by the Pompeian priestess, Eumachia, in the middle of the first century C.E., in the Forum of the city. The entrance is marked by a delicately carved acanthus scroll in marble against the brick of the facade.

Eumachia was not only a rich woman, a holder of an extremely important public priesthood, she was also politically involved. The building’s commission seems to have come at just the moment when her son was running for public office, and his mother’s generosity would have served him well. She commanded far greater power and wealth than many other women in Pompeii, but that did not prevent some of the others from involving themselves in financial and political affairs. A large property with a colonnaded garden belonged to Julia Felix, who rented it out. A graffito dated between 64 and 79 C.E. (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV.1136; trans. Natalie Kampen), tells us that

On the estate of Julia Felix, the daughter of

Spurius Felix, the following are for rent: an

elegant bath suitable for the best people, shops,

rooms above them, and second story apartments,

from the Ides of August until the Ides of August

five years hence, after which the lease may

be renewed by simple agreement.

Julia Felix was hardly alone in involving herself in financial affairs, since at every social level below the aristocracy, women in Pompeii seem to have handled money. Women are known from the wood and wax tablets that record money paid to sellers of goods by buyers through the agency of the banker Jucundus (Andreau 1974). Fourteen women are scattered through the more than 150 documents; they normally represent themselves in these transactions although they seem never to have acted as witnesses for the transactions of other people. In November and December of the year 56 C.E., Umbricia Januaria and Umbricia Antiochis, who may have been freed slaves of the fish-sauce merchant Umbricius Scaurus, received money for sales they had made. Umbricia Januaria’s document tells us that:

Umbricia Januaria hereby attests that she received from L. Caecilius Jucundus 11,039 sestertii, less a percentage [1–2 percent] as his commission, for the auction of goods on her behalf. This action took place at Pompeii on December 12 [56 C.E.], L. Duvius Clodius being the consul at the time.

(Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV, supplement 1, pp. 308–10;

trans. Natalie Kampen)

Figure 12.4. The statue of Eumachia, patron of the building in Figure 12.3. The statue was found in the building, having been given in honor of Eumachia by the corporation of fullers.

A few years later, in a tavern in Pompeii, one perhaps similar to the setting for the four small paintings of gamblers and drinkers with their waitress at an inn (Fig. 12.5), a graffito on the wall says, “On the fifth of February, Vettia accepted from Faustilla fifteen denarii with eight asses (the as was a small denomination) in interest” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV.8203, probably after 64 C.E.; trans. Natalie Kampen), and Faustilla reappears, again lending money at interest, on the wall of the house of Granius Romanus (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV.8204). That women lent as well as borrowed and engaged in business as well as philanthropy suggests their relative autonomy at certain social levels.

The world of taverns and cheap food shops saw other women at work as well. Asellina may have owned this tavern after 64 C.E. when earthquake damage necessitated so many repairs to buildings (Fig. 12.6), and its walls repeat her name as well as those of Zmyrina, Maria, and Aegle, who may have been waitresses; their single and somewhat exotic names as well as the content of the graffiti suggest that they were slaves, but they nonetheless engaged in the public world of politics as well as of work (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV.7862–64, 7866, and 7873). The graffiti all use the word rogat and tell us that a candidate for office is being proposed for the consideration of the passerby. Men and women of the lower classes seem to have favored these public declarations as did respectable matrons such as Taedia Secunda, the grandmother of a candidate of the mid-first century C.E. (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV.7469), even though it is clear that neither women nor slaves of either sex could vote (Franklin 1980; Bernstein 1988). At Asellina’s tavern, one of the waitresses speaks to her customers in her own voice in a highly idiomatic Latin: “The lovely Idone greets those who will read this. Idone says that here you may drink for nine dupondii,” and she tells us prices for better wines as well (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV. 1679; trans. Natalie Kampen).

Figure 12.5. A waitress serves customers in a tavern at Pompeii in the mid-first century C.E. This is part of a set of wall paintings that include men playing dice and, perhaps as a consequence of the wine and the dice, getting into a fight.

Figure 12.6. View of the interior of the tavern of Asellina, a Pompeian woman known to have employed several other women as waitresses.

The graffiti on Pompeian walls (they date mostly from the mid-first century C.E.) speak of waitresses and other working people as well. In one (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV.8259; trans. Natalie Kampen), Severus the weaver writes that his coworker Successus “loves the tavern maid whose name is Iris, but she really doesn’t care about him; even so, he begs and tries to get her to pity him. His rival writes this. Farewell.” The badly damaged frescoes from the workshop of the dyer Verecundus showing a woman selling articles at a table and the dyers at work let us know that men and women slaves and perhaps free workers might often have labored together and developed their friendships at work.

Words of love and admiration slid easily into obscenity with the aid of wine as some of the tavern walls tell us: “I fucked the bar girl” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV.8442; trans. Natalie Kampen) or “Here Euplia laid strong men and laid ‘em out” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV.2310b; trans. Natalie Kampen). A similar story appears on the walls of brothels in Pompeii, although the pictures use a romanticized language unlike these raw words. Above the cubicles (Fig. 12.7) in which undernourished and unglamorous slave prostitutes worked for equally unglamorous men, beautiful boys and girls frolicked in wall paintings. The pictures show clean and lovely young people in comfortable settings with bed linen and pictures on the walls; their varied poses as well as the idealization of the imagery tells the customers the lies they want to hear as they contemplate a few minutes escape (Brendel 1970:61–66).

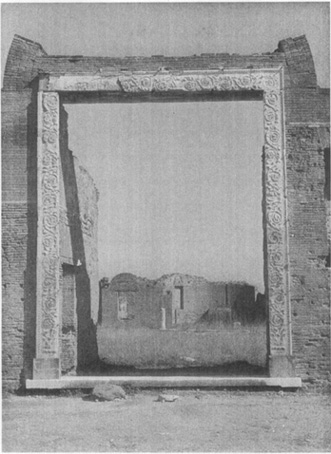

Whether prostitutes or saleswomen, shoppers in the marketplace or high-ranking priestesses, Pompeian women moved freely through the town. In its public spaces they saw buildings constructed with women’s money, statues to women, women at work, and women commemorated even in death. The publicly displayed tombs and tombstones so typical of the outskirts of Roman towns and cities all over the empire bring us still more evidence of women. Here were funerary monuments set up by women for their husbands (Fig. 12.8): on the grave monument (first century C.E.), of C. Munatius Faustus erected in his memory by his wife Naevoleia Tyche, were a portrait of Tyche and a relief of a funeral ceremony (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X.1030; trans. Natalie Kampen) . On the facade the inscription reads,

Naevoleia Tyche, freedwoman of Lucius, for herself and Caius Munatius Faustus, member of the Augustal priesthood and country-man to whom the decurions, with the consent of the people, granted a bisellium (an honorific seat) for his merits. When she was alive, Naevoleia Tyche had this monument built also for her freedmen and those of Caius Munatius Faustus.

Figure 12.7. Interior of one of the several brothels in Pompeii; dated to the last years of the city, the brothel had small frescoes of heterosexual love-making painted above the entrances to the cubicles where the prostitutes worked. Whether these pictures tell us anything about actual sexual practices or are instead as “optimistic” as any advertising is unclear.

A travertine altar-shaped tomb (ca. 20 C.E.) erected by the Ceres priestess Alleia Decimilla commemorated her husband and son, both community officeholders (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X.1036), and a large tomb for Agrestinus Equitius Pulcher in the Porta Nocera cemetery was paid for by his wife Veia Barchilla (D’Avino 1967: 108). Eumachia’s tomb stands nearby as does the tomb of M. Octavius and his freedwoman wife Vertia Philumene (Etienne 1977: 333). Upper- and middle-class tombs thus testify both to Pompeian women’s use and even control of money and to the family relationships their social standing permitted them. Being honored by a funeral paid for with public money, as were the priestess Mamia and others, was the final testimony to their importance in the community.

Upper-class women lived with husbands, children, slaves, freed slaves, and assorted kin, in grand houses. How they used the space is by no means clear, however; nothing in the spatial arrangements or decorations reveals especially gendered places in the house. A few things are clear though: because ladies had slaves to do the domestic work, the kitchen was not the feminine preserve it became in modern times. Neither is there evidence for women’s use of separate sitting rooms or dining rooms. Only when an area was given over to production work is women’s presence attested to; thus the house of M. Terentius Eudoxus had a peristyle that was used as a weaving workshop. Graffiti in the porticus name men and women as textores (weavers) and netrices (net-makers) (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum IV. 1507). Such use of space in a private house for production probably involved household slaves, and the finds of loom-weights in gardens and peristyles in other houses in Pompeii suggest that men and women slaves worked generating income for families all over town.

Figure 12.8. The first-century C.E., tomb monument of C. Munatius Faustus and Naevoleia Tyche in the cemetery of Porto Ercolano at Pompeii. The form recalls an altar, and many of the tombs at Pompeii incorporate reliefs with portraits or scenes of the occupations of the deceased.

Houses for families of modest means were more the rule in some districts in Pompeii than the great mansions; with their smaller rooms and more limited spaces, these two-story houses dominated residential areas such as the Via dell’Abbondanza. The main streets of these neighborhoods had shops to which women and their slaves could walk, and they could easily have walked to public baths like the Stabian and Forum Baths that had sections for women from the second century, B.C.E. on. The women’s baths are discreetly tucked away in corners of the much larger men’s bathing and exercise areas, an arrangement comparable to what one can still see today in old towns in the Middle East. In some middle- and lower-class districts of the first century C.E., houses contained small workshops for production by families, and one can even find one-room shops with what seem to be living quarters in small mezzanines that speak of meager earnings. Relatively few domestic articles remained for archaeologists in these modest houses, but beds, marble tables, and bronze lamps can be seen along with pottery for daily use and storage. As is the case in the houses of the rich, space use and use of many objects are not clearly gendered, nor can one tell from the way things look whether women or men had a greater role in decorating and furnishing the house.

Women did decorate themselves at Pompeii as elsewhere in the Roman world; both sculpture and paintings reveal norms for women’s appearance, and cosmetic jars and jewelry, earrings, pins, and golden hairnets, provide specific evidence. A painting of a young couple, she with gold jewelry and holding a stylus and tablet, presents three important ideas: the representation of the couple, a woman’s attractiveness, and female literacy (Fig. 12.9). Such an image locates a woman in a world that combines the very old traditions—marriage and female beauty as natural and necessary—with the notion of female competence; this last is hardly surprising as a motif in the Pompeii we have been exploring, a place where women own property, do business, pay for construction, hold honorific and cultic office, and go about in public.

Images unfortunately cannot answer all the important questions about women in Pompeii; archaeological evidence fails to tell us just how much women could and did enter into public life and to what extent their physical mobility was limited by their sense of propriety and duty or by the intervention of fathers and husbands. Surely many of the aristocratic women of Rome felt little need to ask permission to move as they pleased or to enter into political negotiation and intrigue, but the same situation is harder to imagine for the wealthy and middle-class local families of Pompeii. Little information remains even to tell us about the involvement of such women in religious cult, although Mamia, a public priestess who erected a temple (early first century C.E.) “to the spirit of Augustus by herself and with her own money” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum X.816; trans. Natalie Kampen), and Eumachia, priestess of Ceres, indicate the importance of wealthy women as benefactors. Paintings in temples and houses document the presence of religious groups, such as that of Isis, that were especially popular among women (Fig. 12.10). A number of images of the Egyptian goddess and her rituals appear (see ch. 6 above), for example, at the estate of Julia Felix, but there is no way to know if the owner had a special interest in Isis. And finally, the evidence fails to tell us enough about relationships among women, between workers like the waitresses who call on us to vote for their favorite candidate, between free women and their slaves, between businesswomen like the moneylender Faustilla and the women in debt to her.

Figure 12.9. Wall painting of a couple from a house in first-century C.E. Pompeii; she holds a writing implement and tablets and he a scroll to testily to their learning and thus their status.

Figure 12.10. Wall painting from first-century C.E. Pompeii, it depicts a ritual at the temple of Isis and includes the white-clad priests, priestesses, and followers of this Egyptian goddess whose cult had attracted women since the Hellenistic period.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 C.E. covered the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum and the villas and farms around them. In one sense the eruption was one of the greatest tragedies of all time; in another sense, it did a great favor to archaeology in preserving, as nowhere else, traces of daily life for women and men in every social stratum. Although the difficulties of interpreting this material are enormous, the reader of Chapter 13 will be keenly aware of the extent to which other periods in Roman history lack comparable minutiae about how people lived, ate, dressed, worked, and played.

Arrowsmith, W. 1959. Petronius: The Satyricon. New York.

Andreau, Jean. 1974. Les Affaires de Monsieur Jucundus. Rome.

Bernstein, Frances. 1988. “Pompeian Women and the Programmata.” In Studia Pompeiana et Classica in honor of Wilhelmina F. Jashemski, edited by R. I. Curtis, 1:1–18. New Rochelle, N.Y.

Brendel, Otto J. 1970. “Scope and Temperament of Erotic Art in the Greco-Roman World.” In Studies in Erotic Art, edited by Theodore Bowie and C. V. Christenson, 3–69. New York.

Castren, Paavo. 1975. Ordo Populusque Pompeianus: Polity and Society in Roman Pompeii. Rome.

D’Avino, Michele. 1967. Women of Pompeii. Naples.

De Franciscis, A. 1975. The Pompeian Wall Paintings in the Roman Villa of Oplontis. Recklinghausen.

Digest of Justinian 1985. Translated by Alan Watson. Philadelphia.

Etienne, Robert. 1977. La Vie Quotidienne à Pompéi. 2d ed. Paris.

Franklin, James, Jr. 1980. Pompeii: The Electoral Programmata Campaigns and Politics, A.D. 71–79. Papers and Monographs of the American Academy in Rome 28. Rome.

La Rocca, E., M. de Vos, and E. de Vos. 1976. Guida Archeologica di Pompei. Milan.

Moeller, Walter. 1972. “The Building of Eumachia: A Reconsideration.” American Journal of Archaeology 76, no. 3: 323–27.

D’Arms, John. 1970. Romans on the Bay of Naples. Cambridge, Mass.

Grant, Michael, et al. 1975. Erotic Art in Pompeii. London.

Heyob, Sharon K. 1975. The Cult of Isis among Women in the Graeco-Roman World. Leiden.

Jashemsky, Wilhelmina. 1979. The Gardens of Pompeii, Herculaneum and the Villas destroyed by Vesuvius. New York.

Packer, James. 1975. “Middle and Lower Class Housing in Pompeii and Herculaneum.” In Neue Forschungen in Pompeii, edited by Bernard Andreae and Helmut Kyrieleis, 133–47. Recklinghausen.

Richardson, Lawrence, Jr. 1988. Pompeii: An Architectural History. Baltimore, Md.

Ward Perkins, John B., and Amanda Claridge. 1978. Pompeii A.D. 79. New York.

Will, Elizabeth Lyding. 1979. “Women in Pompeii.” Archaeology 32, no. 5: 34–43.