In this chapter, we concentrate on the way our sources represent marriage, family, and sexuality in the first eighty years of the Imperial period. The Principate, the period from the accession of Augustus as emperor in 27 B.C.E. to 68 C.E. and the death of Nero, the last of the Julio-Claudian line descended from Augustus and his wife Livia, is extraordinarily rich in wonderful art and literature. Our sources in this chapter include Virgil’s Aeneid, the elegant and classicizing sculpture of the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace), and the poems of Ovid. In addition, historians such as Suetonius have much to say about the period, legal texts remain with plentiful information about the laws concerning marriage and adultery (although, of course, they leave out much, including information about failed attempts at legislation and a sense of the range of responses to individual laws), and inscriptions provide us with a notion of the ideal standards of conduct for upper-class women. At the same time that this material offers us a sense of the complexities of personal conduct and public ideology in the period, we face the usual problems of trying to write about women from sources made almost exclusively by men; only Sulpicia’s poems preserve a woman’s voice. And, as ever, the women of the lower classes, slave women, and noncitizen women tend to receive little attention from men whose words and patronage tended to focus primarily on the representation of their own kind. Much was invisible to them since it fell outside the range of their glances.

Moral Revival in the Time of Augustus

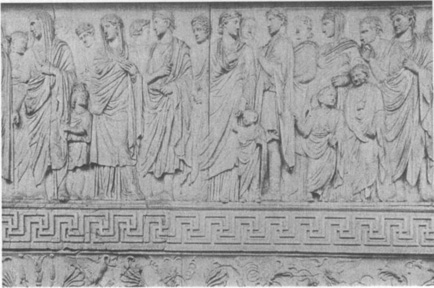

Captured in stone, the family of the emperor Augustus moves in quiet procession toward the altar at which they will offer a sacrifice in honor of the peace Augustus brings to the Empire (Fig. 11.1). Along with the images of priests and priestesses of the state religion and the members of the Senate, their idealized portraits cover the monumental reliefs on the long sides of the Ara Pacis Augustae, the Altar of Augustan Peace. Made in Rome between 13 and 9 B.C.E., the altar inaugurates a new era both in state relief-sculpture and in Roman political life. Here, apparently for the first time in Roman public art, mortal women and children are represented along with men; members of Augustus’s family, his wife Livia, his daughter Julia, her children and the foreign royal children being raised at court, and the Vestal virgins join male officials and priests in a clearly expressed display of the piety of emperor and family.

The presence of the women and children on the altar has multiple meanings, for they speak vividly not only to the totality of Imperial piety but also to the emperor’s need to appear as guarantor of peace. Through war and diplomacy he brings peace to the Empire, but, in addition, he offers his family as an assurance that the just-ended civil war can be forgotten and that succession by inheritance can prevent it from ever happening again. The Vestal virgins, keepers of the sacred fire of Rome, guarantee the security of the state as well, and their chastity plays against and casts into sharper relief the alleged fecundity of the Imperial family (Kleiner 1978).

Figure 11.1. The Imperial family in a procession on the Ara Pacis Augustae in Rome (13–9 B.C.E.). The message of dynastic continuity emerges clearly through the presence of women and children in the unusual context of a state monument.

The Augustan emphasis on reproduction that underlies the representation of family on the Ara Pacis, seems to be present in other parts of the altar, too. A panel, its imagery redolent of lush maternal nurturance, shows a woman with two infants surrounded by plants, water birds, and animals. In the panel showing Aeneas about to sacrifice a sow and her suckling young (Fig. 11.2), the imagery of fertility combines with the fulfillment of an oracle’s prediction; in Virgil’s Aeneid (3.390–98 and 8.81–84) this sign tells Aeneas that he has found his new homeland in Italy, where, as in the rich plant life that decorates the lower panels of the altar, rich growth and new life flourish. The altar comes at a time when Augustus was apparently engaged in a multifaceted program of political and moral revitalization of the Roman people; a key part of this campaign was his attempt to police sexual behavior, presumably to raise the rate of legitimate (that is, citizen) births. His new legislation on marriage and adultery (see below) testifies to the emperor’s desire to control private behavior, especially what was perceived by some as the sexual irresponsibility of the Roman upper classes.

Figure 11.2. Ara Pacis Augustae panel showing Aeneas and the sow he discovers at the mouth of the Tiber as a sign that his journey from Troy in search of a new homeland has ended in success. The fertility imagery that pervades the altar recurs here to remind Roman viewers that Augustan peace is the guarantee of fertility and a happy future.

The Aeneid and the Image of Marriage

Given Augustus’s concern to foster marriage and restore both the stability of family life and the reproductivity of the governing class at Rome, it is useful to look to Augustan literature for a representation of the high official valuation of marriage and women’s role as mother. The excerpts from Livy and Ovid cited in chapter 7 show that a woman’s honor could be a political issue, and even start a revolution. Augustus himself would quote speeches of old Roman censors that urged reluctant men to marry and reproduce. But if we look to literature for a warmer appreciation of marriage, the picture is strangely disappointing.

The Odyssey is built around the sanctity of a good marriage; in a famous passage Odysseus tells the young princess Nausicaa:

And may the gods accomplish your desire

a home, a husband, and harmonious

converse with him—the best thing in the world

being a strong house held in serenity

where man and wife agree. Woe to their enemies

joy to their friends! But all this they know best

(Odyssey 6.180–86; Fitzgerald 1961)

In contrast, Virgil’s Aeneas is a man alone, and the women who are or might have been his wives are removed as obstacles to the destiny of Rome, while the princess-bride Lavinia is a simpering cypher whom Aeneas never meets within the compass of the poem. Virgil does show a loving relationship between Aeneas and his Trojan wife Creusa, mother of his heir Ascanius, but when they must escape from Troy, she is left to follow behind the three generations of men and is lost in their panic. Rome’s destiny requires her ancestor to be a widower. The ghost of Creusa absolves Aeneas:

O my sweet husband, is there any use

in giving way to such fanatic sorrow?

For this could never come to pass without

the gods’ decree … you will reach

Hesperia, where Lydian Tiber flows

… there days of gladness lie in wait for you:

a kingdom and a royal bride. Enough

of tears for loved Creusa. I am not

to see the haughty homes of Myrmidons

or of Dolopians or to be a slave

to Grecian matrons, I, a Dardan woman

and wife to Venus’ son. It is the gods’

great Mother who keeps me upon these shores.

And now farewell, and love the son we share.

(Aeneid 2.780–89; Mandelbaum 1961)

Three times he tries to embrace Creusa’s ghost, and three times his arms clasp empty air—just as they will when he sees his beloved father’s shade in Elysium.

To ensure Aeneas’s safe welcome in Carthage, the goddesses of sex and marriage conspire to delude the honorable and generous queen Dido into love for the stranger, whom she takes as consort and sharer of power in her city. Virgil’s sympathetic and tragic Dido is perhaps the single best-known woman in all Roman literature: a widow who breaks her oath of celibacy in memory of her murdered husband and devotes herself to Aeneas. But despite the supernatural wedding ritual, Aeneas must obey divine command to leave her, and he answers her reproaches with a stern rebuke:

I am not furtive. I have never held

the wedding torches as a husband; I

have never entered into such agreements.

If fate had granted me to guide my life

by my own auspices and to unravel

my troubles with unhampered will, then I

should cherish first the town of Troy, the sweet

remains of my own people.

… And now the gods’

own messenger, sent down by Jove himself—

I call as witness both our lives—has brought

his orders through the swift air. My own eyes

have seen the god as he was entering

our walls—in broad daylight. My ears have drunk

his words. No longer set yourself and me

afire. Stop your quarrel. It is not

my own free will that leads to Italy.

(Aeneid 4.340–53, abridged; Mandelbaum 1961)

Virgil’s own text, for all its sympathy with Dido’s suicide, speaks more than once of her guilt (culpa) and Roman readers were not likely to see this unofficial and unsanctioned love as having any claim over their hero. Indeed, some readers will have associated Dido, for all her goodness, with that famous contemporary queen, Cleopatra, she who conspired with his weakness to ruin Antony and threaten Rome’s integrity. Instead of succumbing to Dido as Antony had to Cleopatra, Aeneas when freshly arrived in Latium will be offered King Latinus’s only child, Lavinia, as bride through the proxy of his envoys, and with her the kingdom she symbolizes.

This betrothal provokes the fierce war between Lavinia’s former suitor Turnus and Aeneas. The future bride and groom do not meet, but Lavinia appears twice; first we see her among the Latin matrons supplicating Minerva for their city.

And Queen Amata too

with many women, bearing gifts, is carried

into the citadel, Minerva’s temple

upon the heights: at her side walks the girl Lavinia,

the cause of all that trouble,

her lovely eyes held low. The women follow

and they perfume the altars with the smoke

of incense and their voices of lament

pour from the shrine’s high threshold.

(Aeneid 11.478–83; Mandelbaum 1961)

In the last book she appears again, when her mother speaks of Aeneas as her unwanted son-in-law. “Lavinia’s / hot cheeks were bathed in tears; she heard her mother’s / words; and her blush, a kindled fire, crossed / her burning face” (Aeneid 12.70–72).

Nor do women as mothers receive sympathy against the background of masculine urgency and the nation’s fate. Two scenes are particularly revealing. The first occurs in Sicily when Juno, disguised, deceives the tired Trojan women into burning the fleet so that they may settle there, and they are scolded by the child Ascanius: “What is this new madness? Where are you aiming now, alas, poor wretched citizens?1 You are not burning the Argive foe and enemy camp. These ships are your future hope. See here am I, your Ascanius!” His future and Rome are their reason for existing. One mother alone, for love of her son Euryalus, follows the men to Latium, and she is treated in such way as to provide a bitter contrast between Ascanius’s promises and her own reality. To Euryalus, volunteering for a dangerous mission, Ascanius swears that if Euryalus perishes

she shall be a mother to me, lacking

only the name Creusa. No small honor

awaits her now for bearing such a son.

Whatever be the outcome of your deed,

I swear by this my head, as once my father

was used to swear, that all I promised you

in safe and prosperous return belongs

forever to your mother and your house.

(Aeneid 9.297–302; Mandelbaum 1961)

When Euryalus’s mother hears of his death and wails in mourning, Virgil reports her lament, but the same Ascanius orders her to be taken into custody and confined indoors to stop her upsetting the Trojan fighting men (Aeneid 9.500–502). For all Virgil’s poetic compassion, he represents the state as a structure in which women must ever serve men’s needs or be suppressed.

Adultery and Resistance to Marriage and Reproduction

The disruptions of the civil war years and the changing mores of Roman upper-class life had a profound impact on the behavior of Roman women and men, as the previous chapters have shown. Claims that adultery was rife in Rome weave through the writings of Ovid, as when he has the old “hag” Dipsas say,

Maybe in the days when Tatius ruled, the grubby Sabine women refused to be taken by more than one man; now Mars tries men’s souls in far off wars, and Venus rules in her Aeneas’ city. The lovely ladies are at play; the only chaste ones are those no one has courted.

(Ovid, Amores 1.8.35–44; trans. Natalie Kampen)

He also laughingly claims, at Amores 3.4, “A man is really a bumpkin who takes his wife’s unfaithfulness seriously; he doesn’t know enough about the morals of Rome” (trans. Natalie Kampen). Horace, in Satire 1.2, advises men to avoid adultery and matrons as more trouble than they are worth; “It’s safer to go second class, I mean go with freedwomen” (trans. Natalie Kampen). With a freedwoman, he never worries

About her husband just dropping in from the country, the door

Splitting open, the dog yapping, house in an uproar of crashing

And pounding on all sides, my girl tumbling head over heels

Out of bed, as white as a sheet, while her maid (and accomplice)

Shrieks it’s not her fault—deathly afraid of her legs

Being broken as punishment—the wife, thinking now to herself

“There goes my dowry,” while I eye myself sprinting off

In a panic, my tunic undone, and trying to salvage

My money, to safeguard my future and save my behind

(trans. S. Palmer Bovie)

Clearly, sex with a free married woman could cause a man some terrible problems. However, adultery was defined by law and custom as sex with a married woman other than one’s wife; a free man still had sexual access legally to his slaves, to women whose work as prostitutes or barmaids put them outside the law’s concern, and to concubines. None of these cases counted as adultery for him, although a married woman was an adulteress if she had sex with anyone but her husband (Digest 48.5.1).

An odd footnote to the principle that adultery was extramarital sex by a married woman appears in Seneca’s discussion of adultery and lust in a text on legal controversies; the author presents models of disputation that may or may not be based on reality. In one he mentions a case of “the man who caught his wife and another woman in bed and killed them both” (Seneca the Elder, Controversies 1.2.23; Winterbottom 1974). That women had sexual relationships with one another is rarely alluded to by male authors, and then usually in so veiled or unclear a way as to make the whole question especially difficult. When Ovid tells the tale of Iphis, a girl brought up as a boy who falls in love with his/her betrothed, he has the hero(ine) complain bitterly to the gods about the cruelty of her fate; she calls her feelings and her identity “monstrous” and rejects the pleasure of the homoerotic. The gods give her one of the rare happy endings for a woman in the Metamorphoses when they turn her into a man on her wedding day (Ovid, Metamorphoses 9.666–791). Martial, writing at the start of the second century, makes explicit reference to the women who behave like men and have sex with girls as well as boys (Martial, Epigrams 1.90 and 7.67), and so does the Greek poet Lucian, whose courtesan won’t tell her curious friend exactly what two women do in bed (Dialogues of the Courtesans 5). The veiled references and insinuations may add up to just one more form of libertine behavior as the writers proceed with their usual castigation of female frivolity.

In a voice of deepest seriousness, the philosopher Seneca, writing to his mother from his exile in Corsica, where he seems to have been sent because of accusations of adultery with Caligula’s sister Julia Lucilla, lays out a striking yet typical landscape of sexual irresponsibility:

Unchastity, the greatest evil of our time, has never classed you with the great majority of women; jewels have not moved you, nor pearls; to your eyes the glitter of riches has not seemed the greatest boon of the human race; you, who were soundly trained in an old-fashioned and strict household, have not been perverted by the imitation of worse women that leads even the virtuous into pitfalls; you have never blushed for the number of your children, as if it taunted you with your years, never have you, in the manner of other women whose only recommendation lies in their beauty, tried to conceal your pregnancy as if an unseemly burden, nor have you ever crushed the hope of children that were being nurtured in your body; you have not defiled your face with paints and cosmetics; never have you fancied the kind of dress that exposed no greater nakedness by being removed.

(Seneca, Consolation to his Mother 16.3–5; Basore 1964/1979)

Not only adultery and makeup, shameless dress and conduct were deemed scandalous; the open refusal to bear children brought women much criticism. A poem by Propertius to his Cynthia, written before 23 B.C.E. (see Chapter 10) suggests some resistance by men as well as women; “Why should I beget children for national victories? / There will be no soldier of my blood! / … You alone give me joy, Cynthia; let me alone please you. / Our love will mean far more than fatherhood” (Propertius, Elegy 2.7; trans. Natalie Kampen). His concern may be with an early version of the Augustan marriage laws that might have separated his beloved from him, perhaps forcing him to marry a “respectable” bride, but the poem suggests that the law was withdrawn or abrogated and the lovers thus were saved.

The possible loss of his mistress to an abortion prompted Ovid to write,

She who first began the practice of tearing out her tender progeny deserved to die in her own warfare. Can it be that, to be free of the flaw of stretchmarks, you have to scatter the tragic sands of carnage? Why will you subject your womb to the weapons of abortion and give dread poisons to the unborn? The tigress lurking in Armenia does no such thing, nor does the lioness dare destroy her young. Yet tender girls do so—though not with impunity; often she who kills what is in her womb dies herself.

(Ovid Amores 2.14.5–9, 27–28, 35–38; trans. Natalie Kampen)

A more even tone on the subject of abortion, less concerned with castigating women for immorality or vanity or with fear for the life of the beloved, comes through the writings of the doctor Soranus who practiced medicine in Rome in the later first century, C.E. He discusses contraception and abortion, giving preferred methods for both; he indicates that opinion was divided in the medical community about the permissibility of abortion:

For one party banishes abortives, citing the testimony of Hippocrates who says: “I will give to no one an abortive”; moreover, because it is the specific task of medicine to guard and preserve what has been engendered by nature. The other party prescribes abortives, but with discrimination, that is, they do not prescribe them when a person wishes to destroy the embryo because of adultery or out of consideration for youthful beauty; but only to prevent subsequent danger in parturition if the uterus is small and not capable of accommodating the complete development, or if the uterus at its orifice has knobbly swellings and fissures, or if some similar difficulty is involved. And they say the same about contraceptives as well, and we too agree with them.

(Soranus, Gynecology 1.19.60; Temkin 1956)

Soranus’s position as a professional doctor meant that he saw as his patients wealthy women and their valued slaves rather than those whose poverty might have motivated their desire to limit the number of children they had; similarly, he considered legitimate the medical rather than social or emotional reasons for a woman to require an abortion or to use contraception. It does not follow that contraception and abortion were inaccessible to poor women through midwives, or that upper-class women avoided such practices except for medical reasons. Essentially, both in the medical world and in the world of the poet, sexuality, male and female, was under scrutiny and the subject of some disagreement, predictable in a time of social and political transformation.

Legal Definitions and Prescriptions on Marriage and Adultery

It is in this context of changing sexual standards that Augustus’s new legislation on marriage and adultery was written and the Ara Pacis carved. They came on the heels of changes in custom that had gradually removed the vaunted absolute power of the father of a family over all his male and female dependents; by the late Republic, for example, few marriages followed the old pattern in which a father passed his daughter and her property into the absolute control of her husband and his family. Paternal power over life and death, power to force a son or daughter to divorce, and family judgment and punishment of the civil crimes of its dependent members all became less common than the texts suggest they were in the early Republic (Rawson 1986: 1–57 and 121–44).

The Augustan laws, designed to penalize those citizens who remained unmarried or childless (women between twenty and fifty and men after the age of twenty-five (see below) and those who committed adultery or married women or men of the “wrong” social rank or status (see below), had as their ostensible goals the moral revitalization of the upper classes, the raising of the birth rate among citizens, and the policing of sexual behavior in the attempt to reintroduce conservative social values and control the social conduct of an upper class seen as more interested in pleasure and autonomy than in duty and community. The laws may, however, really have been attempts to reconfigure social and property relationships; the years of changing customs, of loosened paternal power and of social chaos in the time of the civil wars of the first century, B.C.E., may have set laws out of tune with contemporary practices to such an extent that they were seen as ineffectual in representing reality. Augustus, addressing changed circumstances in a language of conservative values and moral revival, proposed legislation that would make the state and its courts the arbiters of private conduct. The laws, first issued probably in 18 B.C.E. and amended by supplementary legislation more than twenty-five years later in 9 C.E. as the Lex Papia Poppaea, are today known mainly in fragmentary and sometimes distorted form in the writings of later jurists and historians who cite them.

Issues of marriage and reproduction that once had been mainly under the control of families now became, at least on paper, public and the purview of the community as a whole. The laws penalized people who did not marry or have children by attacking their eligibility to inherit wealth.

Unmarried persons, who are disabled by the Lex Julia from taking inheritances and legacies, were formerly deemed capable of taking the benefit of a trust. And childless persons, who forfeit by the Lex Papia, on account of not having children, half their inheritances and legacies, were formerly deemed capable of taking in full as beneficiaries of a trust.

(Gaius, Institutiones 2.286; Poste 1890)

And both the Lex Julia on marriage and its revision in the Lex Papia Poppaea rewarded women for having larger families. Normally, as Ulpianus (third century, C.E.) says, “Guardians are appointed for males as well as for females, but only for males under puberty, on account of their infirmity of age; for females, however, both under and over puberty, on account of the weakness of their sex as well as their ignorance of business matters” (Ulpianus, Rules, 11.1; trans. S. P. Scott in Leftkowitz and Fant #195).

Guardianship terminates for a freeborn woman by title of maternity of three children, for a freedwoman under statutory guardianship by maternity of four children: those who have other kinds of guardians … , are released from wardship by title of three children.

(Gaius, Institutiones 1.194, Poste 1890)

Accordingly, when a brother and sister have a testamentary guardian, on attaining the age of puberty the brother ceases to be a ward, but the sister continues, for it is only under the Lex Julia and Papia Poppaea and by title of maternity that women are emancipated from tutelage; except in the case of Vestal Virgins, for these, even in our ancestors’ opinion, are entitled by their sacerdotal function to be free from control.

(Gaius, Institutiones 1.145; Poste 1890)

Thus, women benefited by the new legislation through having larger numbers of children. Upper-class women and men also sometimes gained by these laws since the emperor could confer the exemption of three children on those who, like the empress Livia and Pliny the Younger, did not in fact have three living children of their own.

Augustus may have hoped by legislating privileges for the fathers and mothers of three or more children to ensure an increased birth rate, but we have far more evidence for low reproductivity than for happy fertility among the members of the upper class. Augustus’s daughter Julia might give her husband five healthy children, and in turn Julia’s daughter Agrippina gave birth to nine, but he himself only produced one child by any of his wives, and since this child was a daughter we may be sure that he and Livia did what they could to produce a son—and failed. Our evidence for infertility, miscarriage, and death in childbirth is so random that we need to include samples from both the previous generation (Cicero’s daughter died in childbirth after her second child; neither child survived) and the next century. We know, for example, that Ovid, Seneca, and Pliny the Younger each married three times, and that only Ovid saw a child, one daughter, grow up. Pliny’s young wife miscarried and her early death may have been connected with the complications of pregnancy. Another example of combined infertility and death in childbirth leading to the extinction of a blood line is that of Augustus’s own adoptive father Julius Caesar, whose daughter Julia, married to Pompey, miscarried and died soon after in childbirth. The implications for women’s expectation of life are clear here: to conceive was not guaranteed, to miscarry was all too frequent, to die in childbirth was a high probability, and the survival of infants with or without their mothers was a cause for real rejoicing. It is not surprising that in the generation before Augustus, Catullus had used as a simile for the preciousness of his love for Lesbia the preciousness of the single small grandson born to an aging grandfather by his daughter and only child (Catullus 68.119–24).

Freedwomen also benefitted from the new laws as Dio Cassius, writing in the third century C.E., explains: “since, among the freeborn there were far more males than females [of reproductive age?], he (Augustus) allowed all who wished, except the senators, to marry freedwomen, and ordered that their offspring should be held legitimate.” (Dio Cassius 54.16.1–2; Cary 1980). Further, freedwomen could also benefit from the law by attaining a degree of autonomy in the making of their wills; normally, a freedwoman or freedman owed a certain amount of work or share of profits to her or his former owner and remained in a position of legal dependency on the owner whose permission was needed for financial and legal transactions and who inherited the majority of the freedwoman/man’s property (Gardner 1986: 194–96).

The Lex Papia Poppaea afterwards exempted freedwomen from the tutelage of patrons, by prerogative of four children, and having established the rule that they could henceforth make testaments without the patron’s authorization, it provided that a proportionate share of the freedwoman’s property should be due to the patron, dependent on the number of her surviving children.

(Ulpianus, Epitome 29.3–6; Abdy and Walker 1876)

Underlying much of this legislation, and embedded in the notion of moral restructuring of social life, was a concern with revitalizing and purifying the family life of the citizens of Rome. It may well have been intended in part to use that purified family life to remind Romans of the moral and social structures that had once, at least theoretically, united a homogeneous community. Thus, part of the law tried to prevent marriage with people of immoral character.

By the Lex Julia senators and their descendants are forbidden to marry freedwomen, or women who have themselves followed the profession of the stage, or whose father or mother has done so; other freeborn persons are forbidden to marry a common prostitute, or a procuress, or a woman manumitted by a procurer or procuress, or a woman caught in adultery, or one condemned in a public action, or one who has followed the profession of the stage.

(Ulpianus, Epitome 13–14; Abdy and Walker 1876)

What may be indicated in these laws is a relaxation of paternal control over marriages among the citizens of Rome. Such control was exercised by the emperor in his arrangements for his daughter Julia, although she clearly managed to circumvent other forms of control for a while.

Julia was betrothed first to Mark Antony’s son and then to Cotiso, King of the Getans, whose daughter Augustus himself proposed to marry in exchange; or so Antony writes. But Julia’s first husband was Marcellus, his sister Octavia’s son, then hardly more than a child; and, when he died, Augustus persuaded Octavia to let her become Marcus Agrippa’s wife—though Agrippa was now married to one of Marcellus’s two sisters, and had fathered children on her.2 At Agrippa’s death, Augustus cast about for a new son-in-law, even if he were only a knight, eventually choosing Tiberius, his step-son; this meant, however, that Tiberius must divorce his wife, who had already given him an heir.

(Suetonius, Augustus 63–65; Graves 1957)

Being a political pawn was certainly the fate of men and women of the Imperial house, but arranged marriages were usual, as well, for the young sons and daughters of the propertied classes, as Ovid tells us in his autobiographical poem (Tristia 4.10), “When I was but a boy, I was made to marry an unworthy wife— / not for long!” (trans. J. Ferguson in Chisholm and Ferguson 1981: 272). Roman law in this period permitted either party to sue for divorce with relatively little fuss, and the sources suggest that arranged marriages might be susceptible to that end for all sorts of reasons, not only political ones.

Conduct within marriage was also to be controlled by the state, as was sexual behavior outside of wedlock. The Lex Julia de adulteriis of 18 B.C.E., a part of the larger Lex Julia, includes sections on adultery, homosexuality, and seduction.

… the Lex Iulia for the suppression of adultery punishes with death not only those who dishonour the marriage-bed of another [man] but also those [men] who indulge their ineffable lust with males. The same Lex Iulia also punishes the offence of seduction when a [male] person, without the use of force, deflowers a virgin or seduces a respectable widow. The penalty invoked by the statute against offenders is confiscation of half their estate if they be of respectable standing, corporal punishment and relegation in the case of baser persons.

(Justinian, Institutes 4.18.2–3; Thomas 1975)

The law permitted women to bring third-party accusations against adulterous husbands but granted only to men the right to accuse a spouse of adultery and to divorce or to kill an adulterous wife (or to kill an adulterous daughter) found in flagrante (under certain circumstances). Thus, the new laws were not intended to bring equality to men and women but rather (ostensibly) to regulate sexuality, to bring it into line with the standards of an idealized righteous past. These laws also must have made clear to the senatorial aristocracy that a new age was beginning, one in which the state would increasingly intervene in family affairs in an attempt to enforce what it characterized as a return to old social values.

It is unclear how the Augustan laws actually affected women’s lives since the love poetry and satire of the period do not explicitly mention these laws and the first references to them by historians come only in the late first century C.E. Suetonius, writing in his life of Augustus at the end of the first century C.E., tells us that the emperor “was unable to carry it (the Lex Julia) out because of an open revolt against its provisions, until he had abolished or mitigated a part of the penalties, besides increasing the rewards [for more children] and allowing a three years’ exemption from the obligation to marry after the death of a husband or wife” (Suetonius, Augustus 34.1; Rolfe 1970).

Other sources indicate that the Lex Papia Poppaea, to which this passage of Suetonius refers, stipulated that two years was the maximum allowable delay for remarriage:

The Lex Julia allows women a respite from its requirements for one year after the death of a husband, and for six months after a divorce: but the Lex Papia allows a respite for two years after the death of a husband and for a year and six months after a divorce.”

(Ulpianus, Epitome 14; Abdy and Walker 1876)

Although it seems impossible to assess the actual impact of the laws on individuals, their broader message to men and women of the upper classes was that the state would now play an ever-increasing role in their private lives and that role would symbolize the growing control by the emperor over their public lives as well.

Imperial Women and Dynastic Ideology

That sexuality functioned symbolically in this period seems clear from such stories as that of Suetonius on Augustus’s response to the demands of the members of the equestrian class3 for repeal of the marriage laws.

When the knights … persistently called for its repeal at a public show, he [Augustus] sent for the children of Germanicus and exhibited them, some in his own lap and some in their father’s, intimating by his gestures and expression that they should not refuse to follow that young man’s example.

(Suetonius, Augustus 34.2; Rolfe 1970)

Using his family as an ideologically motivated tableau vivant, Augustus provided a living example of the same messages contained in the Ara Pacis sculpture (Zanker 1988: 157–58). Ceremonies would have used the Imperial women in a comparable way, as when Horace describes Livia and Octavia welcoming Augustus back from Spain: “Rejoicing in her peerless husband, let his consort, after offering sacrifices to the righteous gods, now advance, and the sister of our famous chief, and, with the suppliant fillet decked, mothers of maids and sons just saved” (Ode 3.14.5–10; Bennett 1978).

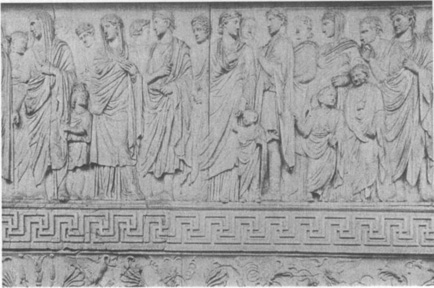

The public display of sculptured portraits of the women and children of the court made similar statements, since many were apparently set up as family groups. The examples of the elegant and classicizing marble busts (Fig. 11.3) of the Imperial family from the amphitheater of Arsinoe-Crocodilopolis (Medinet el Fayyum in Egypt) (4–14 C.E.), or of the large bronze statues of the family from Veleia in Italy both include Livia. Her portraits, many showing her simply dressed in the long, heavy garments of the matron, her hair often covered by a mantle, build on Hellenistic traditions; virtually no Roman female portraits remain from the Republican period as models for the imagery of Imperial women, but Hellenistic queens such as Berenice or Cleopatra did offer an important prototype that blended ideal beauty, recognizable facial features, and royal identity.

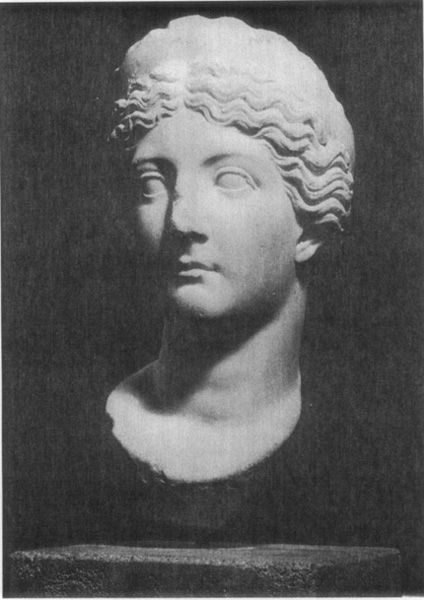

Even when statues of the Imperial women of the period come to us without the archaeological evidence of placement in family groups, they often contain their own stylistic and iconographic codes to communicate the values being promulgated by Augustus. These draw on the Hellenistic models just mentioned, as well as on the imagery of divinities. The portrait of Livia (Fig. 11.4) wearing the diadem of the fertility goddess Ceres (Greek Demeter), dated to the time of Tiberius, conflates empress and goddess to emphasize Livia’s maternal role. Similarly, the statue probably of Livia (Fig. 11.5) with a cornucopia, sign of plenty associated with goddesses and personifications such as Fortuna or Salus, Well-being (dated after 41 C.E.), merges fertility, the maternal, and the Imperial in such way as to reinforce the ideas most important to the dynasty: a revived world born of the peace and security brought by Augustus. With the portraiture of Livia, the Roman artists of the court created an appropriate imagery of the empress-matron, an imagery that could represent an important individual, perhaps the most important woman in the Roman world, while at the same time communicating concepts of royalty, family, and gender ideology.

Figure 11.3. Portrait bust of the empress Livia from Egypt, ca. 4–14 C.E. The simple hairstyle and crisply idealized features are typical of the portraits made while Augustus was still alive.

Dynastic Concerns and the Autonomy of Women of the Court

Here it is important to stop and note that the image of Imperial harmony, of the submission of the Imperial family to dynastic needs, is by no means the whole picture. The Imperial women, as we know from literary and archaeological remains, used their positions to construct roles that permitted some of them a degree of autonomy, influence and even opposition to the dominant Imperial ideologies of the period.

Livia and Agrippina the Younger can provide us with examples. Livia’s relative autonomy emerges in stories about her meetings with ambassadors and envoys while Augustus was otherwise occupied; her importance to Augustus can be seen in the episode in which we learn that the emperor took notes on Livia’s advice and studied them later; and her influence, expressed by writers who clearly worried about it, comes through in the stories about her role in advancing favored members of the court (Suetonius, Augustus 84.2 and Claudius 4.1).

Figure 11.4. Portrait bust of Livia from Rome, after 14 C.E., the year Augustus died. The more elaborate hairstyle and the diadem signal her status as lulia Augusta, adopted into Augustus’s own house and sharing in his status; the diadem may also connect Livia with Ceres, the fertility goddess, a connection made useful politically by the fact that in the year 14 her son Tiberius inherited the throne.

Figure 11.5. Portrait statue probably of Livia as a goddess, from Rome but found in Pozzuoli on the Bay of Naples. In the year 41, with the ascent to the throne of her grandson Claudius, who made Livia a goddess, such images become appropriate.

With Agrippina the Younger, we have an imperial woman who used her mother’s imagery to foster her own political interests (Wood 1988). Before she fell from favor with her son Nero who sent her into exile, Agrippina the Younger is said to have wanted the power to rule as his regent; she used the imagery of her mother to support her claims. Agrippina the Elder, wife of Germanicus and mother of Caligula and his sister Agrippina, was a central figure in the dynastic sequence, as we have already seen, both because of her connection with Augustus and because, persecuted by Tiberius, she distanced Caligula from his much-loathed predecessor and functioned as an image of the noble martyr.

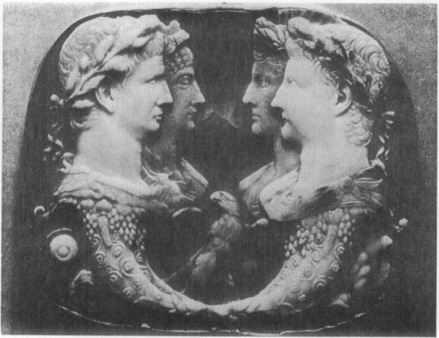

The Gemma Claudia (Fig. 11.6), with its paired busts of Claudius with his bride Agrippina the Younger facing her deceased parents Agrippina the Elder and Germanicus, was probably made at the expense of a rich citizen as a gift for the marriage that took place in 49 C.E. (Wood 1988, 422). The parallel images of mother and daughter clearly served the men of the dynasty in connecting them to Augustus and legitimating their own claims to power; just beneath that surface, however, rest the claims of Agrippina the Younger herself (Wood, 1988). That she was conscious of these claims seems possible from the reports by Tacitus that he consulted “memoirs of the younger Agrippina, the mother of the emperor Nero, who commemorated for posterity the story of her life and of the misfortunes of her family” (Tacitus, Annals 4.53; trans. Natalie Kampen). There, he tells us, he read the story of Tiberius’s refusal to allow Agrippina the Elder to remarry after Germanicus’s death, as a sign of his fear of her potential strength; there too was the story of her protest to Tiberius for intimidating her allies, including her cousin Pulchra. She is quoted as saying, “Pulchra is a mere pretext; the only reason for her destruction is that, utterly foolishly, she chose Agrippina for her admiration.” The emperor responded by reminding Agrippina that “just because she was not a ruler, it did not mean she had been wronged” (Tacitus, Annals 4.52; trans. Natalie Kampen). The stories of the life of Agrippina the Younger preserved in Tacitus’s Annals speak of a woman whose desire for power was characterized as “masculine despotism” (12.7), who set up a colony of veterans in Germany (12.26), and who sat beside Claudius and received with him the homage of the family of the conquered ruler of Britain. “It was really a novelty, utterly beyond ancient ways, for a woman to sit before the Roman standards. In fact, Agrippina bragged that she was actually a partner in the empire which her ancestors had won.” (Annals 12.37)

Figure 11.6. The Qemma Claudia, a carved gemstone from Rome, made about 48–49 C.E., and probably representing Claudius, with his wife (also his niece) Agrippina the Younger, facing Qermanicus and the elder Agrippina, his wife, Qermanicus and Agrippina are the parents of Agrippina the Younger, and Qermanicus is the brother of Claudius.

Less dramatic than the stories of empresses as power-hungry and adept at manipulation, but equally significant in marking the dynamic relationship between individual authority and dynastic teamwork, the inscriptions that appeared on the statue bases of Imperial women are explicit in naming the ties of kinship. In these examples from Thasos in the Greek-speaking East, the relation of individual and dynasty is clear: “The people [of Thasos set up a statue of] Livia Drusilla, wife of Augustus Caesar, divine benefactress,” and “The people [of Thasos set up a statue] of Julia, daughter of Augustus Caesar, our benefactress, following the tradition of her family” (Inscriptionae Latinae Selectae 8784; trans. K. Chisholm in Chisholm and Ferguson 1981: 168). Similarly, “Livia dedicated a magnificent temple to Concord, / and gave it to her husband.” (Ovid, Fasti 6.637–38; trans. J. Ferguson in Chisholm and Ferguson 1981: Elg(b) p. 204). The empress’s patronage of a temple dedicated to the spirit of harmony, both civil and marital harmony, reinforces the messages about the imperial dynastic and moral programs (Flory 1984); these practices of patronage and representation also set the pattern for the relationship of women to state art throughout the next two centuries.

Even in the domestic environment, representations of the Imperial programs of dynastic harmony and well-being could be seen, as Ovid tells in a poem written from exile in Asia. Clearly meant to demonstrate to all readers (including those connected to the emperor whom the poet hoped to convince) that he continued utterly loyal to Augustus despite his sufferings, Ovid writes:

nor is my piety unknown: a strange land sees a shrine to Caesar in my house. Beside him [Augustus] stand the pious son [Tiberius] and priestess wife [Livia], deities not less important than himself now that he has become a god. To make the household group complete, both of the grandsons [Germanicus and Drusus] are there, one by the side of his grandmother, the other by that of his father

(Ex Ponto 4.9.105–10; Wheeler 1975)

The reign of Augustus established several crucial patterns that would remain in effect to varying degrees for several hundred years. First, the Imperial family was a family and its continuity under a dignified and protective father and a noble and fertile mother guaranteed the health and happiness of the Roman people, its children. Second, this notion of the model family was disseminated throughout the empire on works of art, coins, and domestic shrines, in the patronage of buildings and the inscriptions that marked them, and in the ceremonies and choreographed public appearances of members of the court. Representation and political program were consciously and effectively joined, and women played a major role in both.

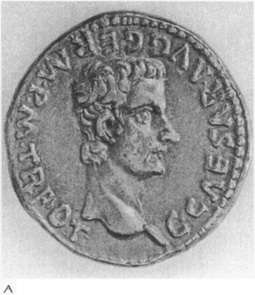

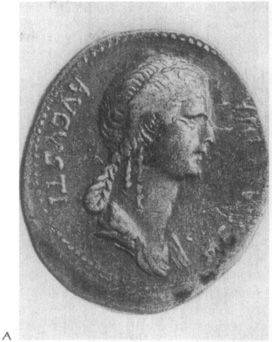

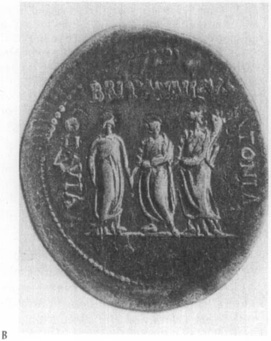

Although moral revival seems less an issue than dynastic propaganda to the emperors of the Julio-Claudian line, all continue to represent the Imperial women and children as symbols of legitimacy and the security of a peaceful future. The great court cameos of the period, the Grand Camee de France (Fig. 11.7), on which Livia sits beside Tiberius and the divine Augustus floats overhead, like the Gemma Claudia (Fig. 11.6), all use family relations symbolized through women as well as sons to document the ruler’s right to rule and his provision of a safe future. As we have just seen, these images can also function to document the power of women, whether as conduits for dynastic claims or for their own ends. Coins do so as well, although the mint in Rome was for a long time more reticent about showing the women and children of the court than were the mints of the eastern provinces. In the east, where the Imperial cult included worship of Livia during her lifetime, even though such would have been unacceptable in Rome, coins from Asia Minor show her as Demeter the mother-goddess with Gaius and Lucius, Augustus’s heirs at the time, or with Augustus and Tiberius (Fig. 11.8). (See Chapter 6, “Hellenistic Ruler Cult.”) Later, however, the women and children of the court begin to appear on the coins of Rome and the west as when Caligula represented Agrippina the Elder in order to demonstrate his relationship to Augustus and the Julian house (Fig. 11.9). A coin of the time of Claudius from Caesarea shows his third wife Messalina (Agrippina the Younger was his fourth wife) on the obverse and his mother Antonia and son Britannicus on the reverse (Fig. 11.10); the coin stresses the emperor’s legitimacy through his mother’s relationship to Augustus (she was his niece), and uses Messalina as mother of the new era to underline the security of succession. Women thus reinforce the emperor’s claims to rule.

What we have been considering is not the sexuality of real Roman women, if such could ever be recuperated, nor the “real” personalities of Livia and her kinswomen, but rather the ideological construction of that sexuality by elite men in their capacities as rulers and as writers. They paint a picture of a society debating the political and moral character of sexuality, a sexuality that threatens the new social order and must be contained within the framework of marriage and reproduction, a sexuality particular to the elite of Rome.

Figure 11.7. The Qrand Camee de France, a large carved gemstone made in Rome, perhaps about 20 C.E. At the center Livia sits beside her son Tiberius as other family members look on under the benevolent gaze of the now divine Augustus, the barbarian families in the lowest register play against the Imperial family to express the triumphant nature of Roman peace.

The Virtues of Women

All women’s lives were affected profoundly in various ways by the social ideology being articulated in laws and dynastic imagery by the emperor. From the “best” of women to the “worst,” the terms were set and debated within the frame of family and reproduction even when women’s lives at every social level frequently moved out of the frame. What should a woman be, then, and in whose opinion?

Figure 11.8. Bronze coin from Asia Minor showing Lucius and Gaius, the sons of Augustus’s daughter Julia and the intended heirs of Augustus; they both died before they could take the throne.

At one pole stands Julia, the daughter of the emperor. To the public she must have seemed Livia’s opposite, the “Other” to Augustan matronly morality. Since we can know Julia only through the scabrous jokes Romans told about her and through the court gossip that constructed her as the farthest pole of promiscuity, what we see is a dreadful warning to all those fast-living women whose conduct Augustan policy aimed to transform. It should be noted that no such warning applied to the emperor himself; Suetonius recounts Augustus’s taste for extramarital affairs and tells how in his old age Livia even procured women for him (Augustus 71.1). And Seneca writes:

The deified Augustus banished his daughter, who was shameless beyond the indictment of shamelessness, and made public the scandals of the imperial house—that she had been accessible to scores of paramours, that in nocturnal revels she had roamed about the city, that the very forum and the rostrum, from which her father had proposed a law against adultery, had been chosen by the daughter for her debaucheries, that she had daily resorted to the statue of Marsyas [a famous spot for prostitutes], and, laying aside the role of adultress, there sold her favors, and sought the right of every indulgence with even an unknown paramour.

(De Beneficiis 6.32.1; Basore 1964/1979)

At the opposite pole are such matrons as Scribonia, the mother of Julia who joined her daughter in exile even though Augustus had left her to marry Livia and, as a Roman father, had exercised the right to control his daughter’s marriages and her fate. Scribonia, like the courageous, self-sacrificing matrons who set examples to the community through their willingness to urge their husbands and sons to dignified suicide, demonstrates both the ideal of family loyalty and the spiritual authority of mature wives and mothers.

Figure 11.9. (A) Gold coin (aureus) of Caligula (37–38 C.E.) from Lyon on the reverse of which (B) is a portrait of Agrippina the Elder, his mother, daughter of Julia and granddaughter of Augustus; the purpose of the portrait honoring emperor and mother is as much to connect Caligula with Augustus as it is to honor Agrippina.

Figure 11.10. Coin of Claudius, dated about 46 C.E. and minted in Caesarea. On the obverse (A) is Messalina, his wife at the time; on the reverse (B) are his mother Antonia and his son Britannicus, along with Octavia. The Imperial family romance thus continues to frame the dual messages of connection to Augustus and to a secure future for the dynasty and so for Rome.

The funeral eulogies for two upper-class matrons, Murdia and Turia, who lived in the time of Augustus indicate the virtues their male kin found worthy of commemoration. Murdia (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.10230) had been married twice and had children by both marriages; no blame attaches to the two marriages even though many funeral inscriptions praise men and women alike for being married to one partner for a lifetime. The rarity of a single marriage received note in an age when elite women married very young (probably in their midteens rather than their late teens as seems to have been the case with women outside the aristocracy) to men who were often considerably older than they; hence these women sometimes outlived their husbands rather than divorcing them. How common divorce actually was, as opposed to the frequency with which it was mentioned as a castigation of the moral standards of the age, we do not know, but remarriage appears to have been no rarity. Murdia’s son by her first marriage, having commented on the fairness of her will, goes on to say that she was motivated to dispose of her goods as she did because

Consistent in her nature, she preserved by her obedience and good sense the two marriages to worthy men that her parents had made for her; as a married woman she became yet more agreeable because of her merits, and her loyalty made her dearer just as her judgement [concerning her will] left her more honored. After her death, the citizens agreed in praising her. The way she divided her estate in her will displays a grateful and loyal spirit toward her husbands, fairness to her children, and justice in her rectitude.

The funeral tribute of all good women should be simple and similar because their natural goodness, over which they keep guard, does not require variations in language. Further, it is enough that all of them have done the same things that gain them a good reputation; in lives tossed by smaller storms there is less room for original ways to praise a woman. For all these reasons, it seems right to focus on conventional virtues in order not to lose anything of the best and thereby debase what remains.

In this sense, then, my dearest mother won the greatest praise of all, because she was like other good women in her modesty, decency, chastity, obedience, wool-work, zeal and loyalty; at the same time, she was at least the equal to any in her virtue, labor, wisdom and the dangers she faced.

(trans. Natalie Kampen, adapted from Horsfall 29–31

and Lefkowitz and Fant 1982: 139)

For Turia (this conventional name masks the fact that her real identity is still uncertain), her husband delivered a eulogy about 10–9 B.C.E., which, although naming the same virtues celebrated in the Eulogy for Murdia, adds public dimensions that resulted from the chaos of the civil war years. Turia and her sister avenged the murders of their parents; Turia herself raised and found dowries for female kin, protected her husband’s interests when he was in exile and helped to bring him back, and secured the punishment of those responsible for his misfortunes. These splendid and courageous actions are recalled, along with her virtues, by the proud and affectionate husband.

“Why … recall your inestimable qualities, your modesty, deference, affability, your amiable disposition, your faithful attendance to the household duties, your enlightened religion, your unassuming elegance, the modest simplicity and refinement of your manners? Need I speak of your attachment to your kindred, your affection for your family—when you respected my mother as you did your own parents and cared for her tomb as you did for that of your own mother and father—you who share countless other virtues with Roman ladies most jealous of their fair name? These qualities which I claim for you are your own, equalled or excelled by but few; for the experience of men teaches us how rare they are.

… In our day, marriages of such long duration, not dissolved by divorce but terminated by death alone, are indeed rare. For our union was prolonged in unclouded happiness for forty-one years.”

(Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.1527; trans. Lefkowitz and Fant #207)

The only shadow across the face of the marriage was the couple’s inability to have children, an inability for which Turia took responsibility.

“Disconsolate to see me without children … you wished to put an end to my chagrin by proposing to me a divorce, offering to yield the place to another spouse more fertile, with the only intention of searching for and providing for me a spouse worthy of our mutual affection, whose children you assured me you would have treated as your own.”

(Ibid.)

He, horrified, refused and says, “I could not comprehend how you could conceive of any reason why you, still living, should not be my wife, you who during my exile had always remained most faithful and loyal” (Ibid.)

In these two eulogies, women’s virtues include modesty, propriety, fidelity, industry, and honor. Care in the management of property joins the list as evidence of the prosperity of the two women. However, we do not see here the kind of romantic love and physical passion that Propertius, Ovid, or Sulpicia (see below) describe in their poems; the evidence seems to suggest that Romans associated these intense emotions with affairs rather than with upper-class marriage.

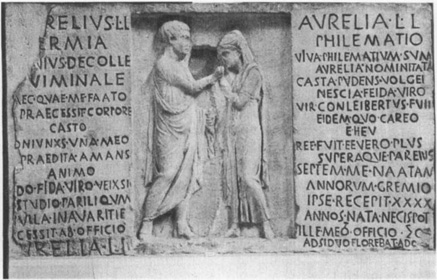

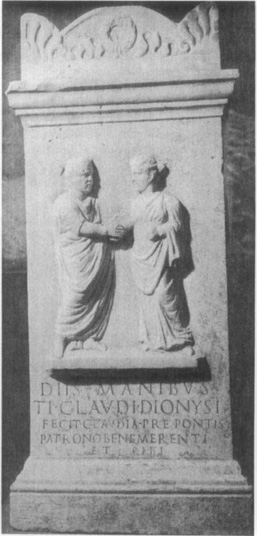

The language of praise for women of the lower strata keeps to the same set of attributes (without the discussion of property, however) and focuses on the same list of virtues. Thus, from first-century Rome comes the tombstone of the freedman butcher Lucius Aurelius Hermia and his wife, “chaste in body, my one and only, a loving woman who possessed my heart, she lived as a faithful wife to a faithful husband with affection equal to my own, since she never let avarice keep her from her duty.” She, Aurelia Philematium, tells us, “I was chaste and modest; I did not know the crowd; I was faithful to my husband,” The inscription shows that he was her fellow freedman, and she lived with him from the time she was seven (although not explicitly as his wife) until her death at forty. (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.9499; trans. Lefkowitz and Fant #137). In a relief, the couple stand between the two inscriptions, he togate and she veiled and drawing his right hand to her lips (Fig. 11.11). Such affectionate images are rare for any level of Roman society in this period, but the traditional gesture associated with marriage, the clasping of right hands, appears in several reliefs of freed slave couples throughout the period; a funerary altar from the Vatican dated to the time of Claudius commemorates T. Claudius Dionysius and was set up by his wife and freedwoman Claudia Prepontis who joins hands with him on the relief (Fig. 11.12).

Marital fidelity and harmony, then, are the expressed virtues of women both at the top and in the lower reaches of Roman society in this period; from Livia to Turia to Claudia Prepontis, the public image of the Roman woman is dominated by private imagery. Among the elite, marriages were arranged in the early Empire for economic and political alliances, but the ideology of marriage as we see it here presumes the growth of mutual respect, affection, and loyalty; most desirable for women are a single husband and children and lives that bring honor not only on themselves and their offspring but on their ancestors as well. Similar values appear in the epitaphs of the lower classes in spite of the lack of ancestors or wealth to be honorably used and passed on. The representations of marital affection in word and image have, for freed slaves, the additional function of underlining their freedom itself. Marriage was, after all, the prerogative of the free, and no slave could claim possession of her or his offspring; an iconography of marriage and family asserted social status for this part of the Roman populace (Zanker 1979).

Figure 11.11. Tombstone from early first-century C.E. Rome, made for Lucius Aurelius Hermia and his wife Aurelia Philematium. He wears the citizen’s toga and she, her head modestly covered, lovingly and humbly kisses his hand.

Figure 11.12. The funerary altar of T. Claudius Dionysius and Claudia Prepontis, made in Rome about 40–50 C.E. and depicting the couple clasping right hands in the marital gesture (dextrarum iunctio) that signaled the legitimacy of marriage.

Sex Outside the Ideal

One pole of female sexuality is thus defined by marriage and reproduction, but, as we have already seen from Ovid and Horace, there were other kinds of behavior, other discourses of sexuality, present in the period. The mass-produced lamps, bowls (Fig. 11.13), and other clay objects stamped with images of heterosexual intercourse, images that catalogue more positions than Ovid himself could recommend, are paralleled in the erotic paintings of the brothels and houses of Pompeii (see Chapter 12); they suggest a significant clientele for low-cost as well as expensive images of sex and a distinct taste for an erotic “art” in which idealized young couples cavort in cozily domesticated interiors. Despite the frequent use of garlands as interior decoration, the viewer would hardly associate these couples with newlyweds, especially since they seem to be drawn from a Hellenistic tradition of books (said to be by prostitutes; hence, pornography: the writings of prostitutes) that catalogued sexual positions (Brendel 1970: 63–68 and Richlin 1992: passim). Rather, the uniformly bronzed young men and their “milky white” partners belong to the world of love poetry, a world outside of marriage.

Figure 11.13. Arretine bowl from Rome, made in the late first century B.C.E. or early first century C.E. Like the Pompeian paintings of lovers from the brothel (Fig. 12.7), the couple appear alone, attentive, and gentle with one another.

An affair of sexual passion with a mistress of one’s own class or a lower class was the focus of much love poetry by the men of the later Republic and the Imperial period; the poems tell of men’s desire and their attitudes to love and sex, and they sometimes construct personalities (though seldom voices) for the mistresses. No woman’s perspective is available to counter what Ovid tells us in the Art of Love:

It’s all right to use force—force of that sort goes down well with

The girls: what in fact they love to yield

They’d often rather have stolen. Rough seduction

delights them, the audacity of near-rape

Is a compliment—so the girl who could have been forced, yet somehow

Got away unscathed, may feign delight, but in fact

Feels sadly let down. Hilaira and Phoebe, both ravished

Both fell for their ravishers.4

(Art of Love 1.673–80; Green 1982)

Similarly, no woman answers Soranus’s notion about the pleasure felt even by a woman who has been raped. The physician argues that “the emotion of sexual appetite existed in [her] too, but was obscured by mental resolve” (Soranus Gynaecology 1.37; Temkin 1956).

No woman defends Corinna against Ovid’s charges of unfaithfulness, or even accuses him of being, perhaps, such an egotist that he has driven his mistress away! Only Propertius allows his Cynthia to speak in her own defense, as when, having told the reader often of his mistress’s infidelities, he goes to her house early to see if she is alone. She scolds him: “What are you doing at this hour, spying on your mistress!? Do you think my ways resemble the likes of you? I’m not so easy: to know a single lover like you is enough for me, or maybe a truer one” (Propertius Elegies 2.29a.31–35; trans. Natalie Kampen). But here, as in the long poem (IV.7) when Cynthia speaks to him from the grave of the wrongs he did her and of the day when they will be reunited in the underworld, the poet remains always in control of his Cynthia’s words; they are always his, as are the words of Tarpeia about her treachery during the Sabine war (Elegies 4.4) and those of Cornelia (4.11) who speaks, like Cynthia, from beyond the grave (see Chapter 10 for the Cornelia Elegy).

Sulpicia

Only one female poet speaks in her own voice, and of her we know little. Preserved among the works of Ovid’s contemporary, Tibullus, a few poems by Sulpicia remain. Although there are modern critics who argue that Sulpicia is a fiction invented by a male poet (see Chapter 13: Pliny the Younger on the man whose wife is said to have written well), many accept the poems as the work of a woman. In the pieces quoted here, the poet speaks in the voice of a young and unmarried woman from an upper-class background of the Augustan period; her guardian still has some control over her, but she is able, nonetheless, to conduct a passionate love affair with a man whom she calls Cerinthus.

This first excerpt is addressed to M. Valerius Messala Corvinus, her guardian, an aristocratic writer, scholar, and politician and a patron of Tibullus. In it the poet argues against having to spend her birthday in the country. In the second piece she tells Cerinthus that the plan has changed and she will be allowed to stay in town.

My hateful birthday is at hand, which I must celebrate

without Cerinthus in the irksome countryside.

What can be sweeter than the City? Or is a country villa

fit for a girl, or the chilly river in the fields at Arezzo?

Take a rest, Messalla, don’t pay so much attention to me;

journeys, my dear relative, are often untimely.

When I’m taken away, I leave my mind and feelings here,

since force keeps me from acting as my own master.

([Tibullus] 3.14; Snyder 1989 131–32)

Do you know of the dreary journey just lifted off your girl’s mind?

Now she gets to be in Rome on her birthday!

Let’s all celebrate that day of birth,

which has come to you by chance when you least expected it.

([Tibullus] 3.15; Snyder 1989 132)

In the following three fragments, all addressed to Cerinthus, the poet speaks of love and desire; the language she uses, like the pseudonym, reflects the same poetic practices used by her male contemporaries. Just how autobiographical the poems are remains as unclear as the degree to which the writer speaks in a particularly “feminine” style (Santirocco 1979).

Finally a love has come which would cause me more shame

were Rumor to conceal it rather than lay it bare for all.

Won over by my Muses, the Cytherean goddess brought me

him, and placed him in my bosom.

Venus has discharged her promise; if anyone is said

to have had no joys of his own, let him tell of mine.

I would not wish to entrust anything to sealed tablets,

lest anyone read my words before my lover does.

But I delight in my wayward ways and loathe to dissemble

for fear of Rumor. Let me be told of:

I am a worthy woman who has been together

with a worthy man.

([Tibullus] 3.13; Snyder 1989: 130)

It is pleasing—the fact that in your carefree way you allow

yourself so much on my behalf, lest I suddenly take a bad fall.

So you care more for a skirt—a wench loaded down with

her wool-basket—than for Sulpicia, daughter of Servius.

There are people concerned about me, and they especially worry

that I might give way to that lowly mistress of yours.

([Tibullus] 3.16; Snyder 1989: 133)

Light of my life, let me not be so burning a concern to you

as I seemed to have been a few days ago,

If in my whole youth I in my folly have ever done anything

which I admit to have been more sorry for

Than last night, when I left you alone,

wanting to hide my passion.

([Tibullus] 3.18; Snyder 1989: 134)

The picture of a proud young woman in love and vacillating between arrogance and vulnerability, self-protection and desire, may be unrepresentative of anything but Sulpicia herself; no other poems of the period by women remain to be compared with hers. Her poems convey a definite personality even as they follow some of the conventions of love poetry. The wish to shout one’s love from the heights, the anger at being taken for granted, the adoring apologies and the admissions of passion are all standard as is the silence of the voice of the beloved. What is missing is the characterization of the beloved as venal, duplicitous or trivial; neither is the poet a suppliant figure starving for a kind word or gesture. Sulpicia’s gender and her class seem to play a role in shaping these few fragments and their projection of her personality; further, they give us our only hints about how a woman might articulate her own desire and point of view about love.

No information remains either about the likelihood of a young girl from the upper classes carrying on a love affair in which loss of virginity was involved; such girls seem to have married so early that there may not have been much time or opportunity for premarital experiments. Further, we know nothing about the language of affection used by women nor about whether same-sex eroticism ever occurred among girls (as opposed to adult lesbian sexual activity hinted at in some texts either as castigation of wealthy women or as entertainment for male voyeurs by prostitutes or female slaves). Even such information as when women had their first children or when they went through menopause is minimal and always contested by scholars; they use data compiled from the thousands of inscriptions on funerary monuments from all over the Roman empire to assess numbers of children, mortality rates, and differing valuations of family members according to geographical location, social class, and time period (Shaw 1987). Despite the difficulties of using such material, scattered, inconsistent, and never scientifically quantifiable, and in spite of the problems of interpretation that come from inscriptions’ formulaic and selective quality, it is possible to suggest a few things about women’s reproductive and family lives. Lower-class people married later than those from the upper classes, death in childbirth and infant mortality rates rose as economic and social level fell, and the expressed valuation of daughters rose over time until the number of mentions of daughters on late antique tombstones matched sons (Saller and Shaw 1984). But what sexual and emotional life felt like to women remains obscure because of the way the sources silence their voices.

Chastity and Community

Let your women keep silence in the churches: for it is not permitted unto them to speak; but they are commanded to be under obedience, as also saith the law. And if they will learn any thing, let them ask their husbands at home: for it is a shame for women to speak in the church.

(1 Cor: 14.34–35)

Writing toward the end of the Julio-Claudian period (died ca. 67 C.E.), St. Paul admonishes men to assert their authority over their women and to silence their public voices. What his motivation was for this famous statement remains open to debate, but in it one can read the tensions that were palpable in so many communities in the first centuries B.C.E. and C.E., over the proper roles of women and over what many men perceived as the dangerous incursions of women into public spheres. Both sexuality and voice are thus manifestations of personal autonomy, and both become the textual signs that reveal the underlying social tensions felt in this period about women’s proper roles.

St. Paul’s attitudes toward sexuality are often seen as characteristic of an early Christian combination of asceticism and misogyny, but however they might be interpreted, some of his opinions are shared by others in this period in the Roman world. When he recommends celibacy, it is to men and women alike and in the interests of focusing the minds of the faithful exclusively on the things of the spirit (7.34); in the same passage, however, he advises those who would marry rather than burn (7.8–9) to treat one another with equal care.

It is good for a man not to touch a woman. Nevertheless, to avoid fornication, let every man have his own wife, and let every woman have her own husband. Let the husband render unto the wife due benevolence: and likewise also the wife unto the husband. The wife hath not power of her own body, but the husband: and likewise also the husband hath not power of his own body, but the wife.”

(1 Cor: 7.1–4).

Seneca’s comments on equality of chastity in marriage sound rather similar:

You know that a man does wrong in requiring chastity of his wife while he himself is intriguing with the wives of other men; you know that, as your wife should have no dealings with a lover, neither should you yourself with a mistress.

(Epistle 94.26; Gummere 1971)

And Musonius Rufus calls on young couples (frag. 14) to make love “to build a wall for the city,” through their marital harmony and their progeny. Sexuality thus becomes a discourse on social values and functions. To Paul, celibacy and concentration on the end of the old order (“But this I say, brethren, the time is short: it remaineth, that both they that have wives be as though they had none” [7.29]) are supremely important. Marital harmony as a positive value expressed through women’s submission and through equal affection is both secondary and a kind of stopgap necessary to maintain social order within the community before the end of time. To Seneca, equal chastity in marriage signals an investment in the Stoic order and concern for self-control, and for Musonius Rufus, most explicitly, marital sexuality is a part of the maintenance of the community both in harmony and in posterity. At no level are these points of view about equality for women and men on a broader social level (Paul 11.3 and 8–9) or about an autonomous and asocial realm of sexual desire; sexuality for men and women is part of the social fabric here just as in the Augustan laws and works of art.

What we have seen in this chapter is the extent to which women’s roles especially in relation to voice, desire, and sexuality were contested and under debate in the Augustan and Julio-Claudian period. The debates were not always in fact about women or sexuality, but they frequently focused on women as the locus for the expression of concerns about a broad range of social tensions from class relationships to the political structure and so on. We began with the construction of socially responsible sexuality in the Augustan laws and public art and moved from there to notions of marital affection expressed in private art and epitaphs. Philosophical texts as well as the literature of resistance, the satires of Horace and elegiac poems of Ovid and Propertius, and even the exhortations of St. Paul frame the social and psychic struggles of the period in terms of sex, marriage, and reproduction; women were the signs—although not the voices—that remain to tell us about those struggles.

1. This is the only time the women’s citizenship is acknowledged.

2. Plutarch suggests that this was all Octavia’s idea (Life of Antony 87.2)

3. This was the class whose wealth and status were slightly below that of the senatorial families.

4. Typically these rapists were heroes and future divinities, Castor and Pollux the sons of Zeus. Ovid’s next role model for rape is the hero Achilles, whose mother was divine.

Abdy, J. T., and B. Walker. 1876. The Commentaries of Gaius and the Rules of Ulpian. Cambridge.

Bovie, S. P. 1959. Horace: Odes and Satires. Chicago.

Basore, J. 1964 / 1979. Seneca: Moral Essays. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Bennett, C. E. 1978. Horace: Odes and Epodes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Cary, E. 1980. Dio Cassius: Roman History. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Chisholm, K., and J. Ferguson. 1981. Rome: The Augustan Age: A Source Book. Oxford.

Fitzgerald, Robert. 1961. The Odyssey. Atlanta, Ga.

Graves, Robert. 1957. Suetonius: Lives of the Caesars. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Green, P. 1982. Ovid: The Erotic Poems. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Gummere, R. L. 1971. Seneca: Epistulae Morales. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Horsfall, N. 1982. “Allia Potestas and Murdia: Two Roman Women.” Ancient Society 12, no. 2: 27–33.

Lefkowitz, M., and M. Fant. 1982. Women’s Life in Greece and Rome. Baltimore, Md.

MacLeod, M. D. 1961. The Works of Lucian. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Mandelbaum, A. 1961. The Aeneid of Virgil. New York.

Poste, E. 1890. Gaii Institutionum iuris civilis. 3d ed. Oxford.

Rolfe, J. C. 1970. Suetonius. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Temkin, O. 1956. Soranus: Gynaecology. Baltimore, Md.

Thomas, J. A. C. 1975. Justinian, Institutes. Cape Town.

Wheeler, A. L. 1975. Ovid: Tristia and Ex Ponto. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Winterbottom, M. 1974. The Elder Seneca. Vol. 1, Controversiae. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Brendel, Otto J. 1970. “The Scope and Temperament of Erotic Art in the Greco-Roman World.” In Studies in Erotic Art, edited by Theodore Bowie and Cornelia Christenson, 3–69. New York.

Flory, Marleen B. 1984. “Sic Exempla Parantur: Livia’s Shrine of Concordia and the Porticus Liviae.” Historia 33, no. 3: 309–30.

Gardner, Jane. 1986. Women in Roman Law and Society. London.

Hofter, M. 1988. “Porträt,” in Kaiser Augustus und die verlorene Republik, Mainz: 291–343.

Horsfall, Nicholas. 1982. “Allia Potestas and Murdia: Two Roman Women.” Ancient Society 12, no. 2: 27–33.

Kleiner, Diana. 1978. “The Great Friezes of the Ara Pacis Augustae. Greek Sources, Roman Derivatives, and Augustan Social Policy,” Melanges de l’École française à Rome, Antiquité 90.2: 753–85.

Lefkowitz, M., and Maureen B. Fant. 1982. Women’s Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation. Baltimore, Md.

Rawson, Beryl, ed. 1986. The Family in Ancient Rome. Ithaca, N.Y.

Richlin, Amy, ed. 1992. Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome. New York.

Sailer, Richard, and Brent Shaw. 1984. “Tombstones and Roman Family Relations in the Principate: Civilians, Soldiers and Slaves.” Journal of Roman Studies. 74: 124–56.

Santirocco, Matthew. 1979. “Sulpicia Reconsidered.” Classical Journal 74, no. 3: 229–39.

Shaw, Brent. 1987. “The Age of Roman Girls at Marriage: Some Reconsiderations,” Journal of Roman Studies 77: 30–46.

Snyder, Jane. 1989. The Woman and the Lyre: Women Writers in Classical Greece and Rome. Carbondale, 111.

Wistrand, Erik. 1976. “The So-called Laudatio Turiae.” Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis Goteborg.

Wood, Susan. 1988. “Memoriae Agrippinae: Agrippina the Elder in Julio-Claudian Art and Propaganda.” American Journal of Archaeology 92, no. 3: 409–26.

Zanker, Paul. 1979. “Grabreliefs romischer Freigelassener.” Jahrbuch des deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts 90: 267–515.

———. 1988. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, trans. A. Shapiro Ann Arbor, Mich.

Dixon, Suzanne. 1988. The Roman Mother. London.

Gardner, Jane F., and Thomas Wiedemann. 1990. The Roman Household: A Sourcebook. London.

Garnsey, Peter, and Richard Sailer. 1987. The Roman Empire. Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Phillips, Jane. 1978. “Roman Mothers and the Lives of Their Adult Daughters.” Helios 6: 69–80.

Pomeroy, Sarah B. 1975. Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York.

Purcell, Nicholas. 1986. “Livia and the Womanhood of Rome.” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 32: 78–105.

Richlin, Amy. 1981. “Approaches to the Sources on Adultery at Rome.” In Reflections of Women in Antiquity, edited by Helene P. Foley, 379–404. New York.

Stehle, Eva. 1989. “Venus, Cybele, and the Sabine Women: The Roman Construction of Female Sexuality.” Helios 16, no. 2: 143–64.

Treggiari, Susan. 1973. “Domestic Staff at Rome in the Julio-Claudian Period, 27 B.C. to A.D. 68.” Histoire Sociale: Revue Canadienne 6: 41–55.

———. 1991. Roman Marriage. Oxford.

Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 1981. “Family and Inheritance in the Augustan Marriage Laws.” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 27: 58–80.

Wiedemann, Thomas. 1989. Adults and Children in the Roman Empire. London.