This chapter will cover more than five hundred years, from the founding of Rome in 753 B.C.E. to 202 B.C.E, the year of Rome’s victory in her life- and-death war to free Italy from the occupying forces of Hannibal of Carthage. This period begins before the accepted date of the Homeric poems and ends a century after the death of Alexander, but it was not until the last decade of the third century that Rome’s relatively simple culture of farming, war, and religion attempted any literary record of its history. Thus our knowledge of women’s roles during these five hundred years depends on a very few simple inscriptions and a much later historical tradition: even Rome’s first historians, Fabius Pictor (late third century) and the elder Cato (234–149 B.C.E.) only survive at second hand, and the would-be historian of these centuries must depend on the idealistic reconstructions of Livy and the Augustan poets.

According to the Romans’ own tradition their community began without women. In the days when princes were little more than successful shepherds, Romulus, son of an Alban princess, Ilia, by the god Mars, was exposed with his twin brother Remus, suckled by a wolf and brought up by the shepherd who rescued the babies. Once he discovered his royal birth and restored his grandfather to the kingship of Alba, he left with his shepherd band to found a new community on the Palatine hill by the Tiber crossing. This was the future city of Rome. To increase the number of fighting men, he offered asylum to fugitives from nearby communities. But only enemies ever suggested that Rome should find its women among fugitives and criminals. Roman legendary tradition—first known to us from Ennius (239–169 B.C.E.)—had their founder and his men seize by force the virtuous daughters of Rome’s reluctant neighbours, the Sabines (Fig. 7.1). It was even said that the thirty virgins that were carried off gave their names to Rome’s first local citizen units, the curiae. Ideologically the myth of the “Rape of the Sabines” combines the ritual of marriage by capture (as practiced at Sparta: see Chapter 2) with a guarantee of the purity of Rome’s first mothers. The Sabines quickly became mothers in the popular version of the story: when the next campaign season came round and their angry parents mobilized the village militias to attack Rome the Sabine wives rushed on to the battlefield with their Roman babies to separate and reconcile the communities. Marriage had made them Roman, and in one of Rome’s earliest historical plays these women side with their husbands, and reproach their armed fathers, “when you have stripped the spoils from your sons-in-law, what victory inscription will you set up?” (Ennius, Sabine Women; trans. Elaine Fantham)

Figure 7.1. The reverse of a bronze coin (denarius) of L. Titurius Sabinus (89–88 B.C.E.) shows the abduction of two of the Sabine women by Romans.

Two accounts of this “rape of the Sabines” by sophisticated Augustan writers, the patriotic historian Livy and the skeptical love-poet Ovid, show the gamut of attitudes to women, from respect toward the mother of one’s children to indulgent mockery of the naive but charming young creatures needing to be fulfilled by masculine lovers. Livy’s account dates from just after 30 B.C.E.: Ovid writes a generation later, at the turn of the era.

Romulus accordingly, on the advice of his senators, sent representatives to the various peoples across his borders to negotiate alliances and the right of intermarriage for the newly established state.… More often than not his envoys were dismissed with the question whether Rome had thrown open her doors to female, as well as to male, runaways and vagabonds, as that would evidently be a more suitable way for Romans to get wives.… Deliberately hiding his resentment, he prepared to celebrate the Consualia, a solemn festival in honor of Neptune, patron of the horse, and sent notice of his intention all over the neighbouring countryside. On the appointed day crowds flocked to Rome, partly, no doubt, out of sheer curiosity to see the new town.… All the Sabines were there too with their wives and children.… Then the great moment came; the show began, and nobody had eyes or thought for anything else. This was the Romans’ opportunity: at a given signal all the able-bodied men burst through the crowd and seized the young women.

… The girls’ unfortunate parents made good their escape, not without bitter comments on the treachery of their hosts and heartfelt prayers to the God to whose festival they had come in all good faith in the solemnity of the occasion, only to be grossly deceived. The young women were no less indignant, and as full of foreboding for the future.

Romulus, however, reassured them. Going from one to another he declared that their own parents were really to blame, in that they had been too proud to allow intermarriage with their neighbours; neverthless they need not fear; as married women they would share all the fortunes of Rome, all the privileges of the community, and they would be bound to their husbands by the dearest bond of all: their children. He urged them to forget their wrath and give their hearts to those to whom chance had given their bodies.… The men too played their part: they spoke honied words and vowed that it was passionate love which had prompted their offence. No plea can better touch a woman’s heart.

(Livy 1.9, Sélincourt 1960: 43–44, abridged)

The king gave the sign for which

They’d so eagerly watched. Project Rape was on. Up they sprang then

With a lusty roar, laid hot hands on the girls.

As timorous doves flee eagles, as a lambkin

Runs wild when it sees the hated wolf,

So this wild charge of men left the girls all panic-stricken

Not one had the same color in her cheek as before—

The same nightmare for all, though terror’s features varied:

Some tore their hair, some just froze

Where they sat; some, dismayed, kept silence, others vainly

Yelled for Mamma: some wailed; some gaped;

Some fled, some just stood there. So they were carried off as

Marriage bed plunder: even so, many contrived

To make panic look fetching. Any girl who resisted her pursuer

Too vigorously would find herself picked up

And borne off regardless. “Why spoil those pretty eyes with weeping?”

She’d hear, “I’ll be all to you

That your Dad ever was to your Mum”

(Ovid, Art of Love 1.116–31; Green 1982: 169–70)

But against this vote of confidence in Rome’s women, we must balance the tale of betrayal reported by Livy in the same narrative. While the Sabines were besieging the Roman citadel on the Capitoline hill, a girl called Tarpeia, who was either daughter of the garrison commander, or a Vestal virgin (see below, under “Vestal Virgins”) showed the Sabines a secret way up to the citadel. When she asked as her reward, “what you wear on your left arms” (meaning their gold bracelets) they crushed her to death with the weight of their shields (worn over their left arms) (Fig. 7.2). The story reflects Woman as Other, untrustworthy, so petty that she puts love of finery before love of country.

Both legends are represented on coins of the late Republic (Figs. 7.1 and 7.2), but not for any message they conveyed about women. The name of the moneyer who commissioned the design, Titurius Sabinus, shows that he was advertising his name and Sabine origin, and the women were immediately recognizable signs of the stories about Rome’s connection with the virtuous past.

These reverses (the “backs” of the coins) are virtually the only representation of human women among the vast range of Roman Republican coin types. Neither did the early Republic leave behind images of individual mortal women or of their activities, although this can be said as well of mortal men from the same period. Rome’s distrust of Etruscan and Greek luxury, including art, combined with its early emphasis on the subordination of the individual to the needs of the fatherland. Thus, as in the early days of the North American colonies, there was little support for the visual arts; only the family death masks (imagines) of ancestors who held public office, brought out at public funerals to demonstrate the family’s record of service, could attest to the existence of a portrait art. Polybius describes these early public funerals and the carrying of the masks as long since outmoded in his own era, the second century B.C.E. However, we would not expect him to mention masks for women, as they could not hold any public office. By Polybius’s day there were wall paintings showing scenes from Roman history, perhaps reliefs with scenes of public ceremonies, and a few portraits of important statesmen and generals, but among these no mortal women appear.

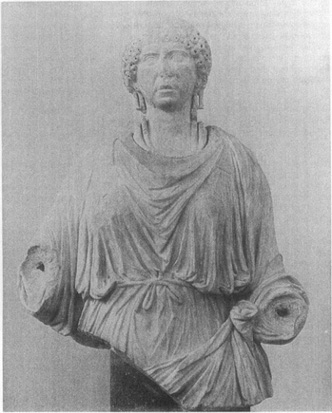

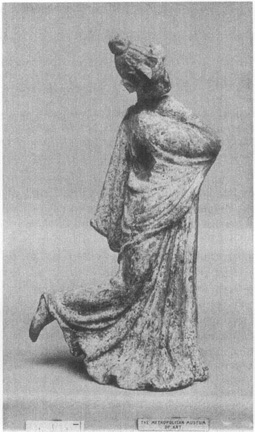

In the early Republic it seems likely that all art was religious or funerary; the preserved monuments of Rome’s neighbours in central Italy include funerary and votive images of men and women such as the fine terra-cotta votive statue from Latium (Fig. 7.3) a monument probably commemorating a third-century young woman offerant or petitioner to the god or goddess. Despite the lack of objects from early Rome, a written record does suggest the existence of statues of some women as well as death masks, statues, and battle paintings with images of men; none of these remains to us today. Several lost statues of named women are reported by the encyclopedist Pliny the Elder (d. 79 C.E.) in his history of art, and by other sources of the first and second centuries C.E:

Figure 7.2. Reverse of a denarius of L. Titurius Sabinus (89–88 B.C.E.) showing the death of Tarpeia. The woman who showed the secret path to the Roman citadel to the Sabines as they came to avenge the rape of their daughters and sisters, Tarpeia, is shown here crushed by the shields of the Sabines.

1. The equestrian statue of Cloelia (fifth century B.C.E.?): “This distinction was actually extended to women with the equestrian statue of Cloelia, as if it were not enough for her to be clad in a toga, although statues were not voted to Lucretia and to Brutus who had driven out the kings, owing to whom Cloelia had been handed over with the others as a hostage.” (Pliny the Elder 34.29; Rackham 1968: 149)

2. “A decree was passed to erect a statue to a Vestal Virgin named Taracia, Gaia, or Fufetia ‘to be placed where she wished’ an addition that was as great a compliment as the fact that a statue was decreed in honor of a woman” (undatable). (Pliny the Elder 34.25; Rackham 1968: 147).

3. The bronze statue of “Gaia Caecilia, consort of one of Tarquin’s sons” (late sixth century B.C.E.) recorded by Plutarch as found in the temple of Sancus together with her dedication of sandals and her spindle “as tokens of her love of home and her industry.” (Plutarch, Roman Questions 30; Babbitt 1972: 53).

4. The Vestal Quinta Claudia, whose statue (second century B.C.E.) in the vestibule of the temple of the Great Mother remained miraculously unburnt in the fire of 22 C.E. (Tacitus Annals 4.64, Valerius Maximus 1.8.11)

5. A seated likeness (end of second century B.C.E.) of Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi and daughter of Scipio Africanus “once stood in the colonnade of Metellus, but is now in Octavia’s Buildings” (see Chapter 9, p. 265). (Pliny 34.31; Rackham 1968: 147)

These statues, all honorific, include at least one made during the recipient’s lifetime (no. 2). She was to have decided where it should be displayed. The statue of Cloelia shown on horseback in a type that had always been associated with military valor, is important in marking a new trend, as is the statue of the Vestal “Taracia.” Pliny comments explicitly both on the honor and on the public nature of these images of women of the highest rank in Republican society.

Perhaps the most significant of these examples, at least for early Rome, is the girl Cloelia; Pliny registers predictable masculine indignation because Cloelia wears the honorific garment of the male citizen (the toga, which we know was also once worn by women) and is depicted on horseback, like a military commander. It may seem strange that she should be shown mounted, but the pose may have been adapted from the Hellenistic Greek tradition of depicting queens on horseback, or perhaps it implied honor for her deed of masculine heroism. Cloelia had been carried across the Tiber among a group of noble Roman maidens taken hostage by the Etruscans:

Figure 7.3. A terra-cotta statue of a young woman (third-century B.C.E.) from Latium. Distantly related to the korai of late Archaic Greece, the serene facial expression and elaborate hair and ornaments of the figure demonstrate the impact of outside cultural influences on art in Italy during the Roman Republic.

One day, with a number of other girls who had consented to follow her, she eluded the guards, swam across the river under a hail of of missiles, and brought her company safe to Rome, where they were all restored to their families.

(Livy. 2.13; Sélincourt 1960: 43–44).

Twice in his early history Livy shows the women acting collectively for the public good: the first instance was the crisis of the early fifth century when the exiled leader Marcius Coriolanus marched against Rome at the head of a Volscian army. When a delegation of the Senate and even priests could not make him relent,

the women of Rome flocked to the house of Coriolanus’ mother Veturia and his wife Volumnia.… They succeeded in persuading the aged Veturia and Volumnia, accompanied by Marcius’ two little sons, to go into the enemy’s lines and make their plea for peace.

(Livy 2.40; Sélincourt 1960: 150)

[The Roman mother commanded respect. At the sight of his approaching mother Coriolanus flinched but went to kiss her and received this rebuke.]

I would know before I accept your kiss whether I have come to an enemy or to a son, whether I am here as your mother or as a prisoner of war. Have my long life and unhappy old age brought me to this, that I should see you first an exile, then the enemy of your country? Had you the heart to ravage the earth which bore and bred you? When Rome was before your eyes, did not the thought come to you “within those walls is my home, with the gods that watch over it—and my mother and my wife and my children”?

(Livy 2.40; Sélincourt 1960: 150)

Veturia’s authority and her invocation of the metaphor of land as mother decided the course of history. When Coriolanus was shamed and withdrew to ignominious exile, the Senate consecrated a temple to Women’s Fortune (Fortuna muliebris) to honor the women’s achievement.

The second intervention of the women is more conventional. In 390 when Rome was occupied by a force of marauding Gauls, the invaders demanded a ransom to leave the city. Livy mentions the women’s offering only after the event:

When it was found that there was not enough gold in the treasury to pay the Gauls the agreed sum, contributions from the women had been accepted, to avoid touching what was consecrated. The women who had contributed were formally thanked, and were further granted the privilege, hitherto confined to men, of having laudatory orations pronounced at their funerals.

(Livy 5.50; Sélincourt 1960: 396–97)

They may have been honored in other ways. Certainly Virgil shows among the rejoicing after Rome’s liberation “the chaste mothers taking the sacred objects through the city in soft carriages” (Aeneid 8.665–66; Mandelbaum 1961).

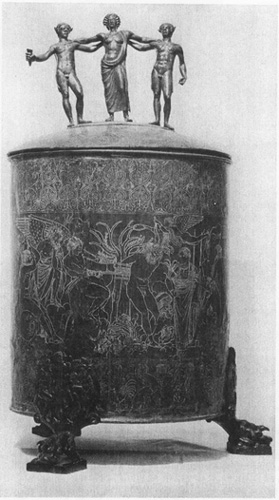

The evidence of a few exceptional artifacts shows that Rome’s material culture was surprisingly rich even in the fourth century, and that women were both patrons and users of precious objects. The inscription on the famous bronze container, called the Ficoroni cista, (Fig. 7.4):

NOVIOS PLAUTIOS MADE ME AT ROME:

DINDIA MACOLNIA GAVE ME TO HER DAUGHTER

bears witness that Roman women not only possessed but had the wealth to commission precious works of considerable sophistication. Was this a wedding gift? Certainly the exquisite bronze chest, made in Rome for a Praenestine family, uses Hellenistic techniques for its complex zoomorphic feet, its handle of Dionysus flanked by two satyrs, and its athletic scenes taken from the epic Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes.

Another of the heroines, Quinta Claudia, won her statue for service to a religious cult. In 204 B.C.E., when the barge carrying the statue of the Great Mother up the Tiber to Rome ran aground, Quinta, after a pious prayer, used her own hair as a barge rope to tow it to its destination near the site of Romulus’s original settlement on the Palatine, where Cybele’s temple was erected.

Conflicting versions of the myth of Claudia make her either a married woman or a Vestal virgin (see below under “The Vestal Virgins: A Special Civic Cult”). In either case she was suspected of unchastity and vindicated her honor by praying that the goddess would only let her move the barge if she were chaste. Romanticizing legends like this became part of Roman patriotic tradition just because Roman society was so late in producing its own literature; the first known dramatic and epic poets come five hundred years after the legendary founding of the city, almost two hundred years after the great age of Athenian drama. So the legendary traditions about queens and other women of early Rome were shaped by writers of a later age, motivated by the need to represent a Roman past as heroic and virtuous as Athenian legend had made Theseus or the early kings of Attica. In the edifying exemplary tales of Cicero and the idealizing narrative of Virgil, Livy, or Ovid, the early Romans succeeded through moral excellence, and their wives and mothers raised their voices only like Veturia, to remind their menfolk of their duty to the country.

The legends of the monarchy and early Republic introduce women into the public narrative as instruments either of political bonding or political change. Occasionally, women can also be glimpsed in their private roles as wives concerned with fertility and motherhood, and with worship and sacrifice to women’s cults. Only the Vestal virgins, the order of priestesses supposedly introduced to Rome by Romulus’s successor Numa, (traditionally dated 715–673 B.C.E.) bridge these categories, serving a public cult on behalf of the state, yet one that is in some sense private, because secluded from men.

Figure 7.4. A large engraved bronze container, the Ficoroni cista, dates to fourth-century B.C.E. Rome but was found in a tomb in Palestrina, a nearby town. It is one of the earliest signed objects from Italy, and bears the name of Novios Plautios. The style, a blend of late Classical Greek and Etruscan elements, demonstrates the degree to which early Roman art was shaped by these two cultural forces.

Roman noble families in the late Republic and Empire used their daughters’ marriages to make alliances with promising young officers or politicians, or to bind competing clans and power groups. So it was natural that in their legends of the past they should invent marriages to explain transfers of power to new dynasties. Just as Virgil gives the Trojan prince Aeneas a legitimate claim to the Latin kingdom of the shadowy King Latinus through marriage to his even more shadowy daughter Lavinia, so Numa and other successors to the monarchy of Rome are given a link to the previous king through marriage. But the women are ciphers until Rome enters the phase of Etruscan domination. Romans saw the relative prominence of women in Etruscan society as a factor in its supposed degeneracy (See Chapter 8). Hence they constructed their legends of the dynasty from Tarquinia to reflect women’s power both used and misused. So the beneficent power of Tanaquil, gifted in the interpretation of omens, and king-maker both for her husband Tarquinius Priscus and the Italian “slave” child Servius Tullius, turns in the next generation to the vicious intrigues of Tullia and her husband Tarquin the Proud (Superbus). The military absences of husbands and fathers, increasing as Rome grew powerful and her enemies more distant, is a factor in early legends and will become a major factor in both the sufferings and the evolving autonomy of Roman women (cf. Evans 1991).

The two most famous women in Roman legend, Lucretia and Verginia, are sacrificial figures, like Alcestis and Iphigenia in Greek mythology. But in contrast they earn their fame as much by their role in stimulating male political action as for their undoubted virtue. Ideologically the Roman woman’s primary virtue was pudicitia (not so much chastity, as sexual fidelity enhanced by fertility). This was the female equivalent to fides, a man’s loyalty to his friends and his country. So Romans cherished the legends of Lucretia the wife and Verginia the virgin daughter.

Lucretia’s domestic tragedy became a public revolution (see Chapter 8). Raped in her husband’s absence by King Tarquin’s son (himself a kinsman of her husband), Lucretia summoned her father, husband, and maternal uncle, declared herself dishonored and killed herself “rather than be an example of unchastity to other wives.” Romans believed that popular outrage at her death provoked the expulsion of the Tarquin dynasty and the creation of the free people’s government (res publica). Lucretia’s husband, Collatinus, and her uncle, Lucius Junius Brutus, led the revolution and were among the first annual elected magistrates. But gender ideology pointed the moral of the story with contrasting depictions of the bad wives and the good:

Now Ardea was beset by Roman forces

and suffered the slow stalemate of a siege.

While there was time and enemies shunned battle,

the camp relaxed and left its soldiers idle:

Young Tarquin entertained his friends with feasting

and wine in plenty. Then the prince spoke out:

“while Ardea’s defiance keeps us fighting

and will not let us take our weapons home

how well do you think our marriages are cherished,

and do our wives have any thought of us?”

Each man proclaims his wife in competition

as tongue and heart grow hot with draughts of wine,

till Collatinus rises and gives answer.

“Words are worth nothing, let us trust in deeds:

The night is young: to horse! Let’s ride for Rome.”

The plan’s approved, the horses are made ready

and bear their masters home; the royal palace

is their first call: they find the door unguarded.

The royal brides with garlands at their throats

carouse all night with wine jugs by their side.

From there they seek Lucretia. She was spinning

baskets of soft wool set before her couch.

The slave girls spun their portion in the lamplight,

their mistress spoke to them in gentle tones.

“Hasten dear girls, for we must send your master

the cloak that we have woven very shortly.

But what news have you heard? For you hear gossip.

How long now do they say the war will last?

You soon will fall, Ardea, to better men.

O wicked town, to keep our husbands from us.

Only let them be safe! But mine is daring

and rushes into danger with drawn sword.

My heart fails when I think of him in battle,

I faint and icy cold seizes my breast.”

She broke off, weeping, dropped the tautened threads

and let her gaze fall sadly in her lap.

This too became her; chaste tears made her lovely,

her beauty matched the goodness of her heart.

(Ovid, Fasti 2.720–58; trans. Elaine Fantham)

Lucretia’s work on her husband’s cloak evokes the main domestic duty of the Roman wife—wool-working, including carding, spinning, and weaving the heavy cloth of the toga and other garments; a later Roman epitaph claims

“Stranger, I have but a little to say. Stand and read. This is the ugly tomb of a fair woman. Her parents gave her the name Claudia. She loved her husband with her heart and bore two sons. One she has left on earth, the other she has placed beneath it. Her talk was charming and her walk was graceful. She kept her house, and worked the wool. That is all”

(Warmington 1940: 1.18)

The tale of the girl Verginia, more complex, allows the maiden no initiative, but brings home to modern readers the importance of women’s free status to protect them from sexual abuse. Sixty years after the expulsion of the Tarquins, ten commissioners were appointed to codify the laws of Rome; one of them, Appius Claudius, lusted after Verginia, the well-bred daughter of one gallant soldier absent on military service, and betrothed to another, the tribune Icilius. In order to get possession of her, Appius suborned a man to claim that she was not a freeborn girl but his own slave. In Rome, as in Greece, the masters of slave women had the unrestricted use of their bodies. So when Verginia’s father could not prevent the monstrous verdict,

he took Verginia and her nurse over to the shops by the shrine of Cloacina.… Then he snatched a knife from a butcher, and crying “there is only one way, my child, to make you free,” he stabbed her to the heart.

(Livy 3.48.5; Sélincourt 1960: 236)

Again the demonstration of injustice provokes a popular uprising and the reassertion of liberty. It is significant that each major step in the development of Roman political progress was associated by legend with the defense or vindication of women against abuse by those outside the family. We might see a parallel with the way in which the expansion of Roman Imperial power would be justified by the defense of client-communities against the aggression of foreign states.

While we may contrast the moral initiative of the married Lucretia with the passive innocence of the virgin, both legends reflect the continuing role of the father. In Roman family law the father (paterfamilias) was also lord of the descendant family. His control (patria potestas) carried the right of life and death over the entire household, which included his children and other slave and freed dependants. In principle he determined the survival or exposure to die of any child born to his wife or in his household, and his wife was powerless to protest the infanticide of a legitimate and healthy child. But given the high child mortality, family pressure might shame a reluctant father into bearing the cost of rearing a third son or second daughter (Rawson 1986).

In the most common form of early Roman marriage a daughter would pass from her father’s control into the manus (hand) of her husband, losing membership in her own gens (family) to enter his. Her position in domestic law would differ little from that of her own daughters. But although she no longer took part in the domestic cults of her own family, it is not clear how much she could share in her husband’s family cults. Descriptions of household ceremonies to Vesta and the Lares (goddess of the hearth, and gods of the household supplies), show daughters rather than wives supporting the paterfamilias in the daily rites.

For a complex series of financial and political reasons, the natal family of a woman might not wish to give her away in a manus marriage. There was another, looser, form of marriage without manus, already attested to in the Twelve Tables, Rome’s earliest law code, written around 450.

Any woman who does not wish to be subjected in this manner to the hand of her husband should be absent three nights in succession every year, and so interrupt the usucapio (prescriptive right) of each year.

(Table VI of the XII Tables, Lewis/Reinhold I. 105 1990: 111)

While tradition explicitly denies the existence of divorce in early Rome, there are many signs of mistrust between husband and wife. Inconsistent traditions report that the laws of Romulus authorized a husband, in consultation with his wife’s relatives, to put her to death for adultery or for drinking wine (Dionysius of Halicarnassus 2.25), or to repudiate her for poisoning his children or counterfeiting his keys or for adultery. (Plutarch Romulus 25). Women were often suspected of poisoning, since they lacked weapons for killing but had access to the preparation of food. On one occasion in the fourth century a great number of Roman wives were given a collective public trial and found guilty of poisoning their husbands (Livy 8.22). Even in the more sophisticated second century the elder Cato (235–149) declared that any woman who committed adultery would also resort to poison—presumably of her husband. What is behind this paranoia? Food poisoning from heat and contamination? Or the ill-effects of love potions (amatoria)? When a wife’s standing depended on her reproductive capability and her husband was impotent or indifferent she might well turn to untested aphrodisiacs. The “poisoning of children,” too, may refer to abortion (or miscarriage) rather than the crimes of a wicked stepmother against children by a previous wife. But Rome was a prudish society; it is often difficult to guess the reality behind veiled euphemisms.

As a community of peasant soldiers, Rome needed sons, and stressed the need by calling the lowest unpropertied class proletarii, “producers of manpower.” Fertility was precious, and explains the tradition that the first Roman to divorce was Spurius Carvilius Ruga, in or around 231 B.C.E. It is clear from Gellius’s text, cited below, that this was not the first divorce in Rome, but a new kind of “no-fault” divorce. Earlier wives may have been divorced for adultery or other serious breaches of conduct without the return of their dowries, but Ruga was divorcing his wife for barrenness, thus setting a legal precedent for returning the dowry when the wife was guilty of no offense (Watson 1967).

Servius Sulpicius in his treatise On Dowries declares that legal measures to define wives’ property first became necessary when Spurius Carvilius … a nobleman, divorced his wife, because there were no children from her body, in the five hundred and twenty-third year of the city. Indeed, Carvilius is said to have greatly loved the wife that he repudiated, and to have held her very dear for her sweet character. But he put the sanctity of his oath before his love and inclination, because he had been required by the censors to declare that he would have his wife “for the sake of begetting citizen children.”

(Aulus Gellius 43; trans. Elaine Fantham)

The oath Carvilius had to swear before the quinquennial review of the censors was simply a reiteration of the Roman formula of marriage. It is clear that these magistrates aimed to foster the birthrate by verifying whether citizens were married and pressuring bachelors to marry; but men had many motives for wanting children, especially sons. A father needed an heir not only to inherit the family property and continue its name, but to maintain the cult of ancestors, and to tend the father’s tomb after death. Hence he had the right to retain his children after a divorce. It was surely a powerful deterrent to a wife anxious to escape a wretched marriage that she could not do so without losing her children (on divorce, see Treggiari in Rawson 1991).

At Rome’s beginnings infertility was not only a family but a national hazard; Ovid describes such a crisis in Romulus’s time to explain the cult of Lucina, goddess of childbirth, and the ancient fertility rites of the Lupercalia.

For once when cruel misfortune kept wives barren

and women bore few pledges of their love

Romulus (who was ruling when this happened)

cried out, “We raped the Sabines to no purpose.

If our offenses brought us war, not manpower,

we would have profited to have no brides.”

Beneath the Esquiline a grove untended

for many years grew in great Juno’s honor;

in supplication there both wives and husbands

bowed down and prayed for help on bended knees.

Then suddenly the tree tops stirred and murmured

mysterious words, as if the goddess spoke.

“The sacred goat must impregnate your women,”

she said. The crowd was dumb with puzzled fear.

There was an augur (time has lost his name)

who came an exile from Etruscan soil;

he slew the goat and made the women offer

their backs for beating with the strips of hide.

So when the moon began its tenth new crescent

the wives were mothers and their husbands sires.

Lucina, thanks to you! The grove has named you

[a pun on lucus],

or else your role as goddess of the light

[another pun, on lux].

Gentle Lucina, pity pregnant women,

and bring to birth the burden of their wombs.

(Ovid Fasti 2.423–55; trans. Elaine Fantham)

Wives who wished to conceive offered themselves at the Lupercalia to be whipped by the Luperci, young men dressed in goatskins, who raced round the foot of the Palatine, striking with thongs of goathide any woman in their path. Juno, the protectress of marriage, also presided over childbirth, under the name Lucina, with other vaguer spirits to help the woman in labor, whether the baby came head first (helped by Porrima, “the forwarder”) or feet first in a breech birth—which needed the aid of Postverta “the turner” (Aulus Gellius 16.16.4).

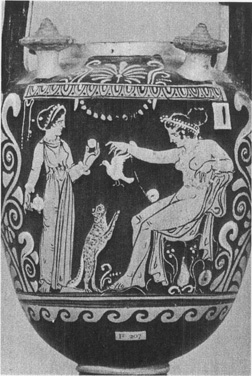

It might be said that Rome had subordinated its goddesses as it subordinated its women. Neighboring cities honored patron goddesses like Diana of Aricia (the goddess whose priest-consort had to fight a challenger each year for his continued privilege), or Juno, represented on coins armed and in goatskin headdress, as warrior patroness of Lanuvium. Unlike the Greek goddess Hera, whose imagery as wife and mother obscures any reference to a military identity, the Juno of Lanuvium seems to draw on the model of Athena, warrior-goddess, as well as on local Italian traditions. The denarius of the mid-first century that shows a girl making a cult offering of food to Juno’s sacred serpent (Fig. 7.5) confirms an incidental allusion made by Propertius, writing in the late first century B.C.E. According to Propertius, if the serpent refused food, this proved the girl was not a virgin. This coin is one of very few images of women’s cult activities from the Republican centuries.

At Rome, Juno had been merely Jupiter’s consort, grouped with his child Minerva in the Etruscan Trinity that occupied the three chambers of the Capitoline Temple. Her public worship was subordinated to that of Jupiter and cult acts in her honor seem to have been confined to women. But it would be oversimplifying to speak generically of “women’s cults.” Noncitizens were excluded and even citizen-women observed separate cults based on their caste or social standing. Thus a woman born to patrician parents was herself a patrician unless she married a plebeian; then her caste, like her clan, became that of her husband.

This caste division is reflected in two anecdotes, one reflecting the political implications of intermarriage, the other its religious consequences. Once again a male historian presents women as motivators of political change. Livy attributes the final successful agitation of the leading plebeians for access to the highest magistracy—the consulship—to the jealousy felt by one sister, with a plebeian husband, for her sibling, whose patrician husband was consul, and escorted by lictors (Livy 6.34). Condescendingly, (“a woman’s feelings are affected by little things” (tr Radice)) the historian blames the petty jealousy of the weaker sex, when it is quite clear (but not so good a story) that the women’s father and the plebeian husband had agreed to agitate for this political “reform” and had the power to make it happen.

Figure 7.5. Reverse of a denarius of L. Roscius Fabatus (64 B.C.E.) showing the feeding of the goddess Juno’s serpent.

Once the plebeians acquire the right to the consulship, a parallel instance of the “caste problem” generates a religious innovation for women—the new cult of plebeian chastity:

A quarrel … broke out among the married women at the shrine of Patrician Chastity … Verginia, daughter of Aulus, a patrician married to a plebeian, the consul Lucius Volumnius, had been prevented by the matrons from taking part in the ceremonies on the grounds that she had married outside her patrician rank. A short altercation followed, which when feminine tempers ran high, blazed out into a battle of wills. Verginia proudly insisted and with reason, that she had entered the temple of Patrician Chastity as a patrician and a chaste woman, who was the wife of one man, to whom she had been given as an unmarried girl and was ashamed neither of her husband nor of his honours and achievements. Then she confirmed her noble words by a remarkable deed. In the Vicus Longus, where she lived, she shut off part of her great house, large enough to make a shrine of moderate size, set up an altar in it, and then summoned the married plebeian women. After complaining about the insulting behaviour of the patrician ladies, “I dedicate this altar” she said “to Plebeian Chastity, and urge you to ensure that it will be said that it is tended more reverently than the other one, if that is possible, and by women of purer life. Thus just as the men in our state are rivals in valor, our matrons may compete with one another in chastity.”

(Livy 10.23; Radice 1982: 319–20)

One phrase here deserves separate comment: “the wife of one man” is not a fancy phrase for monogamy. In Roman thinking the Univira, who had slept only with one man, and never remarried after the loss of her husband, was most honored as the sexual ideal; but the ideal was in conflict with both the widow’s need for a social protector and society’s need for children; there would come a time when it was overridden by legislation (see Chapter 11).

But although the mass of Romans, rich and poor, were plebeians, there was a further division of status marked by both dress and cult. The respectable married matrona was to be identified by her long stola, an overgarment worn over her dress and covering her ankles, and the vittae or headbands covering her hair; this was said by later authors to distinguish her from respectable noncitizens and from the half-world of unmarried women living by their sex. On a statue of a matron (Fig. 7.6) from the time of Augustus (27 B.C.E.–14 C.E.) we can see the stola with its shoulder straps, rarely depicted except apparently to honor ladies of a later era for their old-fashioned virtues. The stola and certainly the vittae seem to have gone out of fashion by the time this statue was made.

In general, noncitizen women were excluded from cult as they were from citizen marriage. But in his poem celebrating the rites of the Roman calendar, Ovid seems to invite married women and freed women alike—“Latin mothers and daughters-in-law, and you who lack the long overdress and fillets”—to share in the ritual washing of Venus on April 1. In honor of Fortuna Virilis (Fortune of men) all the women also offered incense and a drink of honeyed milk and poppyseed and bathed together in the men’s bath. Ovid explains the ritual as guaranteeing that men would be blinded by the goddess to the bodily defects of their womenfolk (Fasti 4.133–60). Although modern scholars have sought to keep respectable and free-living women apart by distinguishing the two rituals, the poet carefully includes all women in each of the different cult acts.

Normally, however, only the religious observances of the matronae are reported. In the crisis of the Hannibalic invasion after 218 B.C.E. religious rites proliferated to reassure the civilian population, and a series of collective women’s offerings is recorded; in the first year of the war the matrons gave a bronze statue to Juno the Queen (Livy 21.62). Next year they offered a formal banquet, with a couch spread to receive her image (Lectisternium). Women of slave origin contributed separately to the cult of Feronia (Livy 22.7). The most interesting sequence of female cult and cooperative action occurred in 207:

Figure 7.6. Statue of a matron from Rome (ca. 27 B.C.E. to 14 C.E.) wearing a stola over her tunic, long and without sleeves, the garment may have been decorated with stripes to indicate the rank of the woman.

[To expiate a prodigy] the priests decreed that three times nine virgins should go through the city in procession singing a hymn. But when they were rehearsing the hymn composed by Livius Andronicus in the temple of Jupiter the Stayer, lightning struck the temple of Juno the Queen on the Aventine.

The soothsayers declared that this portent concerned the married women who must placate the goddess with an offering. All the married women resident in Rome or inside the tenth milestone were summoned by edict of the aediles, and themselves elected twenty-five women to receive contributions from their dowries. From these they made a golden bowl as a gift and carried it up to the Aventine, where a sacrifice was made with due holiness and decency.

(Livy 27.37.7–10; trans. Elaine Fantham)

(The women’s contributions were almost certainly gold ornaments from their personal effects melted down to compose the bowl, rather than money realized by sale of property.) As for the virgins’ processional hymn, Livy reports in detail the special ritual devised for the occasion.

From the temple of Apollo two white cows were led through the Porta Carmentalis into the city. Behind them were carried two statues of Juno the Queen in cypress wood; then seven and twenty maidens in long robes marched, singing their hymn in honor of Juno the Queen.… Behind the company of girls followed the Decemvirs, wearing laurel garlands and purple-bordered togas. From the gate they proceeded along the Vicus Iugarius into the Forum.

In the Forum the procession halted, and passing a rope from hand to hand the maidens advanced, accompanying the sound of their voice by beating time with their feet (timing their song by the rhythm of their steps). Then … they made their way to the Clivus Publicius and the temple of Juno the Queen. There the two victims were sacrificed by the Decemvirs and the cypress statues borne into the temple.

(Livy 27.37.11–15; trans. Elaine Fantham)

It was essentially only in religious acts that young maidens would be seen in public; so Virgil describes the only public appearance of the princess Lavinia, accompanying her mother to the temple.

And Queen Amata, too,

with many women, bearing gifts, is carried

into the citadel, Minerva’s temple

upon the heights: at her side walks the girl

Lavinia, the cause of all that trouble,

her lovely eyes held low.

(Aeneid 11.477–80; Mandelbaum

1971: 290)

One group of women was more public than private; the six Vestal virgins, who were chosen before the onset of puberty to live for thirty years in celibacy tending the sacred fire of the round temple of Vesta in the heart of the Forum. A coin (Fig. 7.7) of Clodius Vestalis minted in 41 B.C.E. has an image of his ancestor, the Vestal Quinta Claudia, on the reverse. This image may copy the statue erected in her honor by the Senate (see above); in any case, it is the only known likeness of a named woman found on public coinage of the Republic and dates from the period of the civil wars that ended the Republic.

Figure 7.7. Denarius of Clodius Vestalis (41 B.C.E.), the reverse of which shows the seated figure of Quinta Claudia, the Vestal who had a statue erected in her honor by the Senate in Rome.

Roman tradition held that the goddess Vesta had no image in her oldest shrine in the forum, although a coin of Cassius Longinus seems to show the goddess with her ritual ladle (simpuvium) in a form that suggests the existence of statuary models. According to Pliny the Elder, the shrine also contained as talismans for the generative survival of the nation a sacred phallus (fascinum), the Di Magni (household gods) of Troy, and a sacred Trojan image of Athena known as the Palladium. It would have been hard for a man to verify these details, since the shrine was closed to all men. Certainly the Vestals sacrificed their own years of fertility to transfer their powers to Rome and the renewal of the generations.

Although the Vestals’ relief (Fig. 7.8) from a public monument, perhaps from the time of Tiberius (14–37 C.E.), is far later than the period covered by this chapter, it shows a scene that may have been common in the Republic also. The six Vestals were frequently seen at public banquets and games where they received special seats of honor; they had the right to make their own wills, unlike other women of the time, and were treated in some ways like men. On the other hand they were bound by ritual and taboo. If the sacred flame went out, it could not be relit from an ordinary firebrand, but had to be rekindled by rubbing a boring stick into a hole. On June 5 each year the Vestals sacrificed a pregnant heifer, and ritually burned both mother and fetus, cleansing the temple with these ashes and other special materials; during the days of cleansing from this sacrifice to the Vestalia on June 15 it was ill-omened for any young woman to marry. The Vestals’ unique service to the state earned special privileges and penalties, described here by Plutarch, writing at the beginning of the second century C.E.

Figure 7.8. Fragment of a marble relief from Rome showing Vestals banqueting (ca. 14–37 C.E.). The relief probably came from a public monument commissioned by the state, although it is no longer possible to know its original location or purpose.

They had power to make a will in the lifetime of their father; they had a free administration of their own affairs without guardian or tutor, … when they go abroad they have the fasces [a ceremonial bundle of rods and ax that symbolized power over corporal and capital punishment] carried before them; and if in their walks they chance to meet a criminal on his way to execution, it saves his life, upon oath made that the meeting was an accidental one, and not concerted or of set purpose. Any one who presses on the chair on which they are carried is put to death.

If these Vestals commit any minor fault they are punishable by the high priest only, who scourges the offender, sometimes with her clothes off, in a dark place with a curtain drawn between; but she that has broken her vow is buried alive.… A narrow room is constructed underground to which a descent is made by stairs; here they prepare a bed and light a lamp and leave a small quantity of food, such as bread, water, a pail of milk, and some oil; so that a body which has been consecrated and devoted to the most sacred service of religion might not be said to perish by such a death as famine. The culprit herself is put in a litter which they cover over and tie her down with cords on it, so that nothing she utters may be heard. They then take her to the Forum. All people silently go out of the way as she passes.… When they come to the place of execution, the officer looses the cords and then the high priest lifting his hands to heaven, pronounces certain prayers to himself before the act and then he brings out the prisoner, being still covered, and placing her upon the steps that lead down to the cell turns away his face with the rest of the priests. The stairs are drawn up after she has gone down, and a quantity of earth is heaped up over the entrance to the cell, so as to prevent it being distinguished from the rest of the mound. That is the punishment of those who break their vow of virginity.

(Plutarch, Numa 10; trans. R. Warner in Fuller 1959: 49–50)

In view of the genuine reverence felt for this cult, it is not surprising that Augustus, when finally elected chief priest in 12 B.C.E., copied the device of the plebeian Verginia and created his own domestic version of the public worship. Augustus took control of the cult of Vesta by incorporating a new shrine of the goddess into his own residence on the Palatine. The emperor thus identified his domestic hearth with the sexual renewal of Rome and her empire; even as chief priest he might not enter the shrine, but he could surely control its attendants (Beard 1980).

How did it affect Roman women when the early phases of Roman society encountered the influence of the Greek cultures of Sicily and south Italy? It used to be thought that access to Greek works of art and mythology at Rome in the years of Etruscan domination was followed by intellectual isolation and cultural impoverishment in the early Republic, until finally in the third century Roman forces in south Italy renewed contact with the richer cultures of Greater Greece (Magna Graecia). More recently excavations in the Forum Boarium, one of the oldest parts of Rome, have revealed fifth-century reliefs with Greek mythological subjects and encouraged the belief that Greek influence returned quickly to Rome, or was never absent.

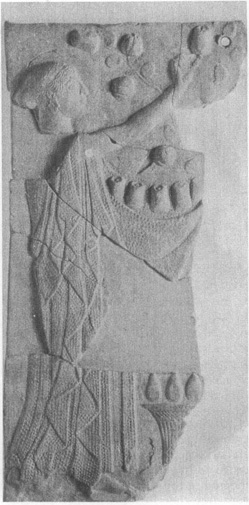

Although the life of respectable Greek women in southern Italy may have been as circumscribed as in mainland Greece, it is fully represented in art, both sacred and secular, reverent and luxurious. In southern Italy, especially in the city of Locri, the cult of Kore (the Maiden) was associated with that of Aphrodite and honored with votive terra-cottas in various shapes. Besides the figurines of the goddess herself, models of naked kneeling women have been found singly at the feet of female burials, and in mass deposits alongside shrines of Kore (Fig. 7.9), while the clay tablets of Locri (see Chapter 1) illustrate every phase of preparation for a marriage either of the Maiden to Hades or of a mortal woman like those who served the goddess. (Fig. 7.10).

Figure 7.9. Mold-made terra-cotta figures of kneeling women from Locri, fifth century B.C.E. Such statuettes came from the deposits associated with shrines of Kore, as well as from women’s burials.

Although Ceres and Libera (Proserpina) were identified with Demeter and Persephone, their cult, shared with the Italic god Liber (Bacchus), and established at Rome at the beginning of the fifth century, presents a striking contrast with the Greek cult. The cult of Ceres seems to have been a political measure to appease social discontent. Certainly Libera/Proserpina did not have any separate cult, and the worship at the new temple in the Forum Boarium was primarily a cult of Ceres as patroness of Rome’s commercial traders in wheat and other imports.

Women’s rituals in Sicily and southern Italy are also reflected by the many vases that appear to celebrate marriage, and may have been created as wedding gifts or furnishings. These often depict women holding mirrors or putting on their jewelry, while winged figures of Eros or Nike hover benevolently around them. One elaborately ornate vase-type, the lebes gamikos (Fig. 7.11), combined such scenes with elaborate lids and free-standing figurines of doves or cupids (Trendall 1988). It is clear that women’s religious and secular interests were important in the Greek communities of southern Italy. Their chief cult, that of Demeter and Persephone, was wealthy and honored with votive gifts: their weddings, their self-adornment, and their beauty were depicted on vases commissioned or produced for mass retail sale. The sensuality and luxury of such artifacts, produced and used in Greek communities in southern Italy during the third century B.C.E., may lead us to question whether Roman life in this period was dominated by the moral puritanism that later writers like Cicero, Sallust, and Livy claim for the past that they idealized.

Figure 7.10. Terra-cotta plaque from fifth-century B.C.E. Locri. A woman picks fruit, here, while on other plaques from the series at the temple of Kore women perform ritual acts, all apparently in preparation for the marriage either of Kore to Hades or of the dedicant of the plaque.

In Rome and central Italy almost no representations of women survive before the first century B.C.E.; even in a funerary context they are symbolized only by the plainest female ornament. A pair of sandals, a makeup box or bowl are sometimes shown in relief on simple stone funerary cippi, as markers for the gender of the dead, parallel to the tools of various trades found on the cippi of their male counterparts. But the more affluent women’s lives may have been more luxurious than the archaeological remains indicate. The cosmetics and trappings not attested to by material remains can be recovered from comic scripts from the end of the third century. The plays were adapted from Greek comedies, but their success implies Roman interest in the frivolous Greek world to the south. A surviving fragment by Naevius (ca.270–204 B.C.E.), Rome’s first comic playwright, delights in portraying a flirtatious girl dancer from Tarentum, the chief city of Apulia:

Figure 7.11. Wedding vase (lebes gamikos) from Campania, south of Rome, by the Danaid Painter, showing a scene of women with pets in an interior; dated to the fourth century B.C.E. The female nudity depicted here is in contrast to Athenian vases, where only prostitutes are shown nude.

She gives herself to each in turn, and passes from hand to hand like a member of a dance troupe; she nods to one man, winks at another, caresses this man and embraces the other; her hand is busy over here, she stamps her foot over there, she gives her ring for one to admire, and entices another with a pout of her lips. While she sings with one man, she writes messages with her finger to another.

(Naevius, Tarentilla, frag. 2; trans. Elaine Fantham)

The inexpensive colorful statuettes of dancers, acrobats, chatting women and fluttering cupids produced from molds are of a type widespread in Hellenistic Greek culture and bring before us this world of flirtation and play (Fig. 7.12). The terra-cotta figurine (of a dancer) found in Apulia is a typical product of south Italian Greek culture. The images of a pleasure-loving life and the interest in female beauty offered by so many forms of south Italian art find a match in the representation of women in the art and culture of Rome’s other neighbours, the Etruscans to the north. Etruscan culture was older than that of Rome, and continued to flourish long after its brief century of domination in early Rome (617–510 B.C.E.) and the shrinking of Etruscan power within the area enclosed by the Arno and the Tiber. But whereas the life of women in Greek Sicily and southern Italy remained private and separate from that of men, we have seen that Roman women, perhaps as a legacy of Etruscan influence in early Roman society, had a recognized role in public. Even so, both Greek and Roman women might well have envied the luxury and social importance of women in the culture of the great Etruscan cities that will be described in Chapter 8.

Figure 7.12. Terra-cotta figurine from south Italy (third-century B.C.E.) representing a dancing woman in a flowing garment and wreath, her elongated body and small head typical of the Hellenistic terra-cottas found at Tanagra and Myrina; this one comes from Taranto where the type was also extremely popular. See also Chapter 5, Figures 5.5 and 5.6.

Babbitt, F. C. 1936/1972. Plutarch: Moralia. Vol. 4. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Green, P. 1982. Ovid: The Erotic Poems. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Fuller, E. (ed.) 1959. Plutarch: Lives of the Noble Romans. R. Warner trans. New York.

Lewis, N. and Reinhold, M. 1990. Roman Civilization: Selected Readings, vol. 1. New York.

Mandelbaum, A. 1961. The Aeneid of Virgil. New York.

Martin, C. 1979. The Poems of Catullus. Baltimore, Md.

Rackham, W. 1952/1968. Pliny: Natural History. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Radice, B. 1982. Livy: Rome and Italy. Books 6-10. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Scott-Kilvert, I. 1979. Polybius: the Rise of the Roman Empire. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Sélincourt, A. de. 1960. Livy: The Early History of Rome. Books 1-5. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Warmington, E. H. 1940. Remains of Old Latin. Vol. 4. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Beard, M. 1980. “The Sexual Status of Vestal Virgins.” Journal of Roman Studies 70: 12–27

———, 1989. with J. North and S. F Price, Pagan Priests. Cambridge.

Crook, J. A. 1967. Law and Life of Rome. Ithaca.

Degrassi A. 1963–65. Inscriptiones Latinae Liberae Rei Publicae. Florence.

Evans, J. K. 1991. War Women and Children in Ancient Rome. New York.

Gardner, J. F. 1986. Women in Roman Law and Society. Bloomington, Ind.

Pomeroy, S. B. 1976. “The Relationship of the Married Woman to Her Blood Relatives at Rome,” Ancient Society 7: 215–27.

Rawson, B., ed. 1986. The Family in Ancient Rome: New Perspectives. Ithaca, N.Y.

Saller, R. 1984. “Familia, Domus and the Roman Conception of the Family,” Phoenix 38: 336–55.

1986. “Patria Potestas and the stereotype of the Roman family,” Continuity and Change 1: 7–22.

Trendall, A. D. 1989. Red Figure Vases of South Italy and Sicily: A Handbook. London.

Watson, A. 1967. “The Divorce of Carvilius Ruga” Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeshiedenis. 33: 38–50.

Gardner, J. F., and T. Wiedemann. 1991. The Roman Household. Oxford.

Hallett, J. P. 1982. Fathers and Daughters in Roman Society: Women and the Elite Family. Princeton, N.J.

Lewis, N., and M. Reinhold 1980 Roman Civilization Volume I Selected Readings: The Roman Republic and the Augustan Age. New York.

Scafuro, A. 1989. “Livy’s Comic Narrative of the Bacchanalia” in Studies on Roman Women ed., A. Scafuro, Part 2, Helios Vol. 16.2, 119–42.

Stehle, E. 1989. “Venus, Cybele and the Sabine Women: The Roman Construction of Female Sexuality” in Studies on Roman Women ed., A. Scafuro Part 2: 143–64.

Treggiari, S. 1991. Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges. Oxford.

Watson, A. 1971. Roman Private Law around 200 B.C. Edinburgh.