Rome’s war in Italy against the invading Carthaginian general Hannibal (218–202 B.C.E.) brought more than religious innovations; it forced major transformations of Roman society. Italy was occupied for more than fifteen years, and the city had to mobilize new armies each year to replace her losses, changing radically the economy of the peninsula and the gender balance of power in the city. Women, either widowed by the heavy casualties or in their husbands’ absence, had to take control at least within the home. However, the austerities of the war were followed by a flush of prosperity and money beyond Rome’s power of absorption from the easier victories over Macedon and Syria. In 215, taxes had been imposed on the wealth of independent women to raise money for military pay, and a new austerity law, the Lex Oppia, restricted women’s finery and withdrew their privilege of riding in carriages; the law, unreported in the urgencies of the military narrative, only arouses the historians’ interest in peacetime when a move was made to repeal it (195 B.C.E). The repeal was supported by vigorous women’s demonstrations and a surge of masculine anxiety, provoked less by the risks inherent in repeal than by the new mood of the women. The speeches on both sides freely composed by Livy still convey vividly the anxiety of male conservatives, and the arguments that a Roman would use to justify rewarding women with greater luxury (34.3–4).

From Cato, the conservative consul, comes the fantasy of women beyond control:

Just review all the rules for women by which your ancestors controlled their license and through which they subjected women to the husbands; yet you can scarcely control them, even when bound by all these restraints. So if you will let them undermine each element and finally be raised level with men, do you think that they will be tolerable? As soon as they begin to be our equals they will be our masters … you give way to them against the interest of yourselves, your estates and your children. As soon as the law no longer imposes a limit on your wife’s extravagance you certainly will not be able to impose it.

(Livy 34.3.1–3; trans. Elaine Fantham)

More interesting is Valerius’s counterclaim, which reviews for us the occasions from the early Republic when women appeared in public to serve the state:

In the beginning under Romulus, when the Capitol was taken and there was a pitched battle in the forum, did not the women calm the fighting by their intervention between the armies? After the expulsion of the kings when the Volscian legions under Coriolanus had pitched camp at the fifth milestone, did not the wives turn back the enemy force that would otherwise have crushed the city? To leave out past history, when we needed money in the last war, did not the widows’ fund help out the treasury, and when the gods were summoned to our aid in desperate times, did not the wives set out in a body to welcome the Great Mother from Ida?

(Livy 34.5.8–10; trans. Elaine Fantham)

For Valerius, display is the woman’s glory:

Women cannot claim magistracies or priesthoods or triumphs or military decorations or awards or the spoils of war. Cosmetics and adornment are women’s decorations. They delight and boast of them and this is what our ancestors called women’s estate

(Livy 34.7.8)

Of course Cato was not alone. We can illustrate popular prejudices about women’s “extravagance” from the contemporary diatribe of a bachelor in Plautus’s comedy, The Pot of Gold. This misogynist imagines rich wives demanding luxuries and boasting of their dowries:

“Well sir, you never had anything like the money I brought you and you know it. Fine clothes and jewelry indeed! And maids and mules and coachmen and footmen and pages and private carriages. As if I hadn’t a right to them.” [He continues in his own words]—wherever you go nowadays you find more wagons in front of a city mansion than you can find around a farmyard. That’s a perfectly glorious sight, though, compared with the time when the tradesmen come round for their money. The fuller, the ladies’ tailor, the jeweller, the woollen worker, they’re all hanging round. And there are dealers in flounces and underclothes and bridal veils, in violet dyes and yellow dyes, or muffs, or balsam scented footgear; and then the lingerie people drop in on you, along with shoemakers and squatting cobblers and slipper and sandal merchants and dealers in mallow dyes; and the belt makers flock around and the girdle makers along with them, And now you may think you’ve got them all paid off. Then up come weavers and lace makers and cabinet makers—hundreds of them—who plant themselves like jailers in your halls and want you to settle up. You bring them in and square accounts. “‘All paid off now anyway,’ you may be thinking” when in march the fellows who do the saffron dyeing—some damned pest or other, anyhow, eternally after something.

(Plautus, Pot of Gold, 498–550; trans. Elaine Fantham)

The comic catalog may not be greatly exaggerated. Roman victories brought immense wealth into the hands of the military commanders and their families. An example is the account given by the Greek historian Polybius (writing after 160 B.C.E) about the family settlements of his young patron, Scipio Aemilianus. Scipio passed on his deceased grandmother’s possessions to his divorced and impoverished mother. The same passage gives an idea of the huge dowries owed by Scipio’s family to his sisters’ husbands, dowries required for them to keep his sisters in the style to which they were accustomed (see also Dixon 1985b).

(Aemilia) the sister of Scipio’s father … left her nephew a large fortune and his handling of this legacy gave the first proof of the nobility of his principles. Whenever Aemilia had left her house to take part in women’s processions, it had been her habit to appear in great state, as befitted a women who had shared the life of the great Africanus when he was at the height of his success. Apart from the magnificence of her personal attire and the decoration of her carriage, all the baskets, cups, and sacrificial vessels or utensils were made of gold or silver, and were carried in her train on such ceremonial occasions, while the retinue of maids and men—servants who accompanied her was proportionately large.

(26) Immediately after Aemilia’s funeral Scipio handed over all her splendid accoutrements to his mother. She had been separated from her husband for many years, and her means were far from sufficient to keep her in a state which was suitable to her rank. In previous years she had stayed at home on such ceremonial occasions. But now when a solemn sacrifice had to take place, she drove in all the state and splendour which had once belonged to Aemilia. All the women who witnessed the sight were moved with admiration for Scipio’s goodness and generosity.

(27) After this there arose the matter of Scipio’s obligation to the daughters of the great Africanus. When Scipio came into his inheritance it was his duty to pay each of the daughters half their portion. Their father had arranged to pay each of them fifty talents. Half of this sum had been paid to the husbands of each by their mother at the time of their marriage, but the other half was still owing.… Roman law laid it down that this part of their dowry that was still due should normally be paid to them over a period of three years; the first payment, consisting of the personal property, being made within ten months, according to the usual custom. Scipio however instructed his banker to pay each of the daughters within ten months the entire twenty-five talents

(Polybius 31.26–27; Scott-Kilvert 1979)

Polybius’s motive is praise of his young patron, but the values of wealthy women appear clearly from the context. While men feared any attempt by young wives to be noticed in public (different noblemen allegedly divorced their wives for being seen with a freedwoman, for attending the games, and even for appearing in public uncovered [Valerius Maximus 6.3.10–12]), wealthy husbands used their older wives as indexes of their affluence—a form of conspicuous consumption noted by Thorstein Veblen in his Theory of the Leisure Class (1899).

Religious ceremonies were the women’s equivalent of military parades; their luxury, however much a matter of competition between women, also reflected glory on their husbands. Even Virgil, in the pageant of Roman history depicted on Aeneas’s great shield, mentions the women of Rome only as they are seen riding to a religious occasion in carriages, (see Chapter 7). Whether the funerary carriages shown on Etruscan funerary urns were the same as those of living women in Rome is unclear (see Chapter 8). That the carriage was a sign of high status and wealth is beyond doubt.

Dowries were known well before the second century, but it is at this time that they developed from a practical transfer of household goods or a plot of land to major economic tools. They feature as a grievance in Cato the elder’s invective against the increasing power of women:

To begin with, the woman brought you a big dowry: next she retains a large sum of money which she does not entrust to her husband’s control, but she gives it to him as a loan: lastly when she is annoyed with him she orders a “reclaimable slave” to chase him about and pester him for it.

(Cato, quoted by Gellius 17.6.8; Gardner 1986: 72)

It was too easy for the husband to rely on the use or interest from his wife’s dowry money, and find himself in difficulties when required to return it on divorce. Lawyers refined the classification of dowry, distinguishing the woman’s original paternal gift from any additional wealth that accrued to her. They even devised rules to cover the proportion that the husband could retain in the event of divorce. One-sixth was retained for the support of each surviving child, while deductions for marital faults ranged from one-eighth for minor offenses to one-sixth if the wife were divorced for adultery (Gardner 1986 ch. 6 Dowry, at p 112). These are modest enough deductions when we bear in mind that an adulterous wife could be lawfully killed when caught in the act by her father; if we are to believe Cato’s speech On the Dowry, her husband had the same right.

When a man has launched a divorce, the arbitrator is like a Censor to the woman. He has the authority to impose what seems good to him, if the woman has acted in any wrong or disgusting fashion. She is fined if she drinks wine; if she has had a dishonorable relationship with another man, she is condemned.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

If you were to take your wife in the act of adultery, you could freely kill her without a trial; whereas if you were to commit adultery … she would not dare to lift a finger against you, nor would it be right

(Gellius 10.23; trans. Fantham)

It was seen as an imbalance in society if any women controlled larger estates than men of the same class. One sign of public anxiety is the Voconian Law of 169 B.C.E. that forbade a man in the top property class from making his daughter heir to more than half of his fortune; behind such legislation is the knowledge that money once left to a daughter passed out of the family.

Despite such indications of women’s growing economic power, it seems that the disciplining of women, even for public offenses, was still a family rather than a public concern. Thus in the widespread scandal of the Bacchanalian conspiracy (186 B.C.E.) women found guilty of participating in the alleged orgies were handed over by the magistrates to their kinsmen for punishment. This could mean execution, or simply confinement on a country estate, where they could be kept out of the public eye. But if anecdotal evidence for the father’s protection of his daughter’s chastity may well belong to this period, there are signs that married women were passing out of their husbands’ control. While the military commander was away campaigning for years at a time in Macedonia or Spain his wife would have a household staff to help her manage his affairs; admittedly the law still required women to conduct any legal business through the intermediary of a male tutor, but it became increasingly common for women to appoint their own puppets, freedman, or family clients who would do what they were told (cf. Evans 1991).

The most memorable woman of the Republic stands at the beginning of accelerating political and intellectual change. Cornelia (180?–105? B.C.E.), daughter of Scipio Africanus and wife of Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, was widowed after she had borne twelve children, only three of whom survived. Her daughter Sempronia married the national hero Scipio Aemilianus, and her sons Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus attempted social reforms that brought immediate violence and prolonged political change. Rome had no royalty yet, but the widowed Cornelia had the status of a princess; she had even refused an offer of marriage from King Ptolemy of Egypt. Instead, she devoted herself to the education of her two sons. She brought Greek philosophers, Blossius from Cumae and Diophanes from Mytilene, to educate the young men, and surely also conversed with the scholars herself.

But there is a conflict in the accounts of Cornelia; we find it natural to assume that she encouraged her sons in their political idealism and attempts to transfer to Rome the practices of Greek democracy. Yet by the end of the Republic, historians could cite verbatim letters written by Cornelia to her younger son Gaius denouncing his revolutionary activities.

I would venture to take a solemn oath that except for the men who killed Tiberius Gracchus no enemy has given me so much trouble and toil as you have done because of these matters. You should rather have borne the care that I should have the least possible anxiety in old age, that whatever you did you thought it sinful to do anything of major importance against my views, especially since so little of my life remains.… Will our family ever desist from madness? … Will we ever feel shame at throwing the state into turmoil and confusion? But if that really cannot be, seek the tribunate after I am dead.

(Excerpt preserved by Cornelius Nepos “On the Latin Historians;”

Horsfall 1989: 43)

It is a pity to challenge the authenticity of the earliest letter surviving from a Roman lady, and in the past these letters have been doubted simply because men questioned her ability to write them. That is not the issue. These letters served too well the propaganda of conservative reaction against the continued attempts at radical reform in the next generation. As a child of Scipio, Cornelia was herself exempt from criticism; so once she was dead it was opportune to “find” letters in which she turned on her sons as Veturia had once denounced Coriolanus.

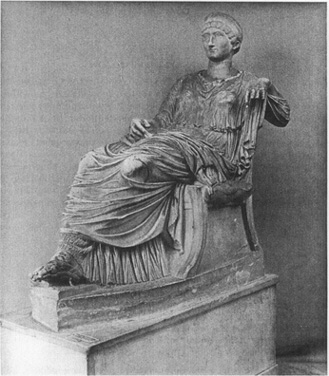

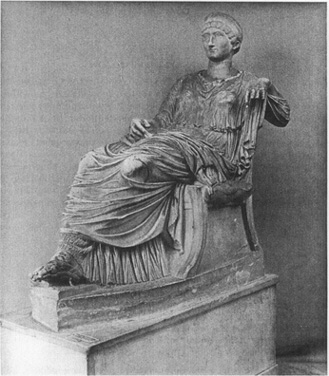

The marble base survives of the now-lost statue of Cornelia (seated like Whistler’s Mother), the first likeness of a secular Roman woman set up by her contemporaries in a public place. Art historians have been able to show that her statue was copied by a Greek sculptor of classicizing taste from the image of the seated Aphrodite by Pheidias. In turn the “Cornelia” became the model for a series of seated Roman ladies, culminating four hundred years later in the portrait said to be of Helena, mother of the emperor Constantine (Fig. 9.1).

This calm Hellenizing likeness of the Roman mother was to be manipulated for political ends. Erected after her death by the next wave of reformers to honor her as mother of the Gracchi, and set in the portico of defeated political enemies, her statue would survive the counterrevolution of Sulla, to be displayed in the renamed portico, now in honor of Octavia, sister of Augustus. But apparently during the conservative reaction against the attempts of later reformers to extend power to the popular assembly, the reference to her famous sons on its base was discreetly filed away and replaced, to put her status as daughter of Africanus before her role as mother (Coarelli 1978). Cornelia may have turned in her grave, but she will not be the only deceased woman commemorated for virtues she neither possessed nor esteemed.

Life was very different for the wives of ordinary peasant soldiers. The prolonged absence of husbands must have forced hardship and initiative onto both peasant women and city wives. This description of the upbringing of the best Roman soldiers from an ode of Horace (65–8 B.C.E.) shows how the mother’s authority had to replace the absent father:

They were a hardy generation, good

farmers and warriors, brought up to turn

the Sabine furrows with their hoes, chop wood

and lug the faggots home to please a stern

mother at evening when the sun relieves

the tired ox of the yoke …

(Horace, Odes 3.6; Michie 1963: 138)

An extreme case of these peasant households occurs in Livy, when the chief centurion Spurius Ligustinus is displayed volunteering for service in Macedonia in 173 B.C.E. No wonder he volunteers, since he is at the top of his profession, and has won many prizes and decorations. It is worthwhile to use his biography to reconstruct that of his wife:

Figure 9.1. Statue (early fourth century C.E.) of a woman of the Constantinian court (Helena, mother of Constantine!) that may replicate the seated statue of Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, the first public statue of a Roman woman who was not a priestess.

“My father left me an acre of land and a little hut in which I was born and brought up, and to this day I live there. When I first came of age, my father gave me as wife his brother’s daughter, who brought with her nothing but her free birth and her chastity, and with these a fertility which would be enough even for a wealthy home. We have six sons and two daughters, both of whom are now married. Four of our sons have assumed the toga of manhood. Two wear the boy’s bordered toga.”

(Livy 42.34; trans. Elaine Fantham)

Quite so, and our hero, now fifty, has served twenty-two years away from the little hut and the eight children, with only brief periods at home between campaigns. He may have brought home good prize money, but he has not had to bring the children up, or find food to put in their mouths each day. To appreciate this woman’s burden of motherhood we should also add to the eight surviving children the miscarriages and stillbirths so frequent in ancient society. Of course the family (essentially only one set of in-laws!) may have helped her out. But who would plant and harvest their piece of land until the children were old enough to help? Such a woman learned independence with a vengeance.

Our sources are indifferent to the life of the poor in town and country. At the bottom of the heap must be the slave women of the country, though Cato seems to have paid the slave women on his model farm for breeding (and his instructions to his overseer suggest that the overseer’s wife has at least a chance of idle gossip); but when Varro’s manual on farming recommends providing sturdy women for the shepherds it is clear just how harsh were the conditions under which they would live.

See that the housekeeper perform all her duties. If the master has given her to you as wife, keep yourself only to her. Make her stand in awe of you. Restrain her from extravagance. She must visit the neighbouring and other women very seldom, and not have them either in the house or in her part of it. She must not go out to meals or be a gadabout. She must not engage in religious worship herself or get others to engage in it for her without the orders of the master and mistress … she must be neat herself and keep the farmstead neat and clean. She must clean and tidy the hearth every night before she goes to bed (other duties omitted).

(Cato, On Agriculture 143; Hooper and Ash 1936: 125)

In the case of those who tend the herds in mountain valleys and wooded lands and keep off the rains not by the roof of the steading but by makeshift huts, many have thought it advisable to send along women to follow the herds, prepare food for the herdsmen, and make them more diligent. Such women should, however, be strong and not ill-looking. In many places they are not inferior to the men at work … being able either to tend the herd or carry firewood and cook the food, or to keep things in order in their huts. As to feeding their young, I merely remark that in most cases they suckle them as well as bear them.… when you were in Liburnia you saw mothers carrying logs and children at the breast at the same time, sometimes one, sometimes two [not necessarily twins] showing that our newly delivered women who lie for days under their mosquito nets, are worthless and contemptible.… In Illyricum it often happens that a pregnant woman, when her time has come, steps aside a little way out of her work, bears her child there, and brings it back so soon that you would say she had not borne it but found it.

(Varro, On Agriculture 2.10.6–8; Hooper and Ash 1936: 409–411)

The city slave would live in a house, but in cramped quarters, feeding on leftovers, depending for his prospects of freedom and a family upon the master’s whim. An educated male slave, or a personal lady’s maid, might hope for early freedom, but if the maid had borne children to a slave partner, either he or she would have to pay for their liberty. She might be punished or sold if she offended her mistress—perhaps by pleasing her master too well—as suggested by the lead curse tablet from the Republican period aimed at the destruction of a female slave:

Danae, the new maidservant

of Capito. Accept this offering

and destroy Danae. You have cursed

Eutychia, the wife of Soterichus.

(Degrassi Inscriptiones Latinae

Liberae Rei Publicae II.1145;

trans. Elaine Fantham)

Or again she might be sold for failing to gratify her master! The slave woman who was not sold away from her partner or child could be sent away from them to hard labor on the country estate. The death of a master or mistress could free large numbers of slaves by their will, or it could uproot them to be sold away from the only home they knew. In Rome as in Greece slave women who did not earn their freedom before they grew old would become the cheapest and most abused of slaves. The ultimate poverty for the free man was to be reduced to “one old slave woman.” The worst fate was to be that unwanted creature.

The skilled slave who earned freedom was in the position of many immigrants in American society; by hard work in a small shop, or Thermipolium (wine bar) or a workshop weaving and dying textiles, the freedman or woman might afford the rent of an apartment and even make savings, to buy and train their own skilled slaves. But either might have to use the first savings to buy a partner’s freedom (contubernalis) and that of any children they might have had.

The funerary reliefs of the late Republic in Rome, set into the walls of tombs along the roads leading into the city and thus visible to the passing world, occasionally document the kind of freed slave families who had saved a bit of money and now wished to take their place among the free citizens of Rome. The surviving examples of freed persons’ tomb reliefs from the first century B.C.E. are few in number (Fig. 9.2), but they offer inscriptions that give names as well as images of couples and kin such as Blaesus, freedman of Caius and Blaesia, freedwoman of Aulus, slaves of the same family. The strangely haunting relief of a mother, father, and child (Fig. 9.3) belongs to the same type so favored by freed slaves from this period into the first century C.E. The woman extends an admonitory hand to touch her husband, as the little boy peeps out from behind them. The inscription with its many names cannot be used to identify the self-absorbed family group set before us, but the woman’s gesture is based on a scene from high art, showing the divine couple Venus and Mars; yet the simple and veristic style of the relief seems worlds away from such classical sources. For the freed slaves who commissioned this group of reliefs, upward mobility came from the public self-representation of family, something to which only a free person was entitled, since a slave had no right to her or his own children, or to make a legal contract such as marriage. And despite the frequently rough style of many of these images, status was also sought by the use of models based on the tastes of the upper classes; men with grim death-mask faces, women with ever youthful and relatively idealized features, poses based on classical prototypes all contributed to the freed slave’s sense of belonging to the legitimate world of free Romans.

Figure 9.2. Tombstone of a couple who were freed slaves, from a tomb in Rome, first century B.C.E. Their names appear in inscriptions on the stone that would have been inserted into the front of a tomb enclosure; the stone was to be seen by passersby.

Figure 9.3. Tombstone of a family group, mother, father, and child, from the late first century B.C.E. in Rome.

Little is known of women’s training in crafts, though wool-working was the basic chore of the household slave, to which she would return in any unoccupied hours. There is more evidence for women trained as entertainers. In the funeral epitaph for the child actress Eucharis quoted here, Licinia her patroness is more likely to have been an ex-actress and freedwoman of the Licinii than a member of that noble family.

EUCHARIS, FREEDWOMAN OF LICINIA, A MAIDEN TRAINED AND

ACCOMPLISHED IN ALL THE ARTS: SHE LIVED FOURTEEN YEARS.

Stop, you whose wandering glance lights on this house,

of death: linger and read our epitaph.

Words that a parent’s love gave to this child

When her remains had reached their resting place.

Just as my youth was green with budding talent

and growing years promised a hope of fame,

The grim hour of my death came on too soon

Forbidding life and breath beyond this time,

Skilled as a pupil of the Muses’ teaching

I who so recently danced to grace the show

Of noble patrons, I who first appeared

before the people in a Greek performance,

See! in this grave the cruel fates have placed

My ashes, unresponsive to my song.

My patroness’s love and care and praise

Are silenced by the pyre, and still in death.

The daughter left her father to lament,

The later born preceded him in doom.

Twice seven birthdays lie with me engulfed

In death’s abode, and everlasting gloom.

Please as you go pray earth lie soft upon me.

(Inscriptiones Latinae Liberae Rei Publicae II. 803;

trans. Elaine Fantham)

Women who lived by sex might buy girl slaves or raise foundlings to work for them when they had aged, but we should not exclude the training of women in crafts and catering. They had no monopoly on the luxury crafts and trades, but the demand for both men and women increased with Roman prosperity, and is attested to by the named specializations of the slave women whose ashes fill the columbaria (underground group burial chambers) of the early empire.

The age that celebrated the dead Cornelia saw increased emphasis on individuality, as noblemen composed their autobiographies in Greek or Latin and noblewomen earned the privilege of a public eulogy at their funeral. The practice begun by the conservative Catulus’s eulogy of his mother (Cicero, De Oratore 2.44), was exploited for self-advertisement by Caesar himself:

My aunt Julia’s family was descended from Kings on her mother’s side, and her father’s is related to the gods. For the Marcii Reges, whose name her mother bore, descend from Ancus Marcius. The Julii, the clan from which my family comes, descend from Venus herself.

(Suetonius, Caesar 6.2; trans. Elaine Fantham)

Cicero himself accepted from Caesar’s murderer, M. Junius Brutus, the commission to write a laudatory biography of Brutus’s cousin Porcia, modeled on the traditional spoken eulogy (Plutarch, On the Virtues of Women 242e). Clearly the politicians saw praise of their womenfolk as a means to their own or their family’s distinction, but their own political conflicts soon led to a situation where the women had to share in political as well as public burdens.

Two generations of civil war from 90 to 30 B.C.E. killed and exiled the heads of many noble families and left the initiative to the surviving women; a Valeria Messalina showed her initiative in accosting and winning in marriage the autocrat Sulla; more conventional women used their position for political influence. Caecilia Metella extended her protection to save Cicero’s client Roscius from his personal and political enemies, while Sallust could name the now-unidentifiable Praecia, mistress of a disreputable consul Cethegus, as the bestower of office to whom all aspirants should apply. Some women were more interested in money than politics. Cicero’s wife Terentia, for example, ran her financial affairs through her steward Philotimus, and seems to have exploited Cicero’s enforced absence from 51 to 47 to profit at her husband’s expense.

You write to us that my resources and yours and Terentia’s will be available. Yours no doubt, but what resources of mine can there be? As for Terentia, to say nothing of innumerable other incidents, doesn’t this cap all? You asked her to change 12,000 Sesterces, that being the balance of the money. She sent me 10,000 with a note that this was the amount outstanding. When she nibbles such a trifle from a trifle, you can see what she will have been doing when a really large amount is involved.

(Cicero, Letters to Atticus 11.24.3; Shackleton Bailey 1965–66: 61–63)

When this action on her part led to divorce, Cicero had to raise the funds to return her dowry, while negotiating to retain a fraction for the expensive Athenian education of their twenty-year-old son. This seems to have been in the form of property, but there was difficulty in securing the rentals from another freedman of Terentia. Further troubles arose when Cicero tried to protect the children’s rights in his own new will, and ensure that they received the proper share of their mother’s fortune. Whatever the ultimate settlement, Terentia’s continued wealth enabled her to remarry more than once and she lived to be more than a hundred.

In contrast, Cato’s half-sister Servilia had more influence than money. Independence was forced upon her. Servilia’s father, mother, and uncle Livius Drusus were killed or died when she was a child and her first husband was murdered by Pompey a decade later. She used her skills to make alliances through the marriage of her daughters with rising politicians from different groups, and even after the death of Caesar, who had once been her lover, one of her sons-in-law, Lepidus, was a privileged Caesarian who could help her secure changes in a senatorial decree on behalf of the “tyrannicides,” her son Brutus and her son-in-law Cassius.

Power like Servilia’s surely came from family connections, but she can hardly have achieved so much without an education. It is a pity that there is so little evidence for the education of the daughters of Rome, and certainly not enough to measure improvement. Cornelia, wife of Pompey and daughter of Metellus Scipio, must have been exceptional:

The young woman had many charming qualities apart from her youth and beauty. She had a good knowledge of literature, of playing the lyre, and of geometry, and she was a regular and intelligent listener to lectures on philosophy

(Plutarch, Pompey 55; from Fall of the Republic; Warner 1972: 216)

This is more like a Greek education than a Roman; music and geometry were not part of the Roman curriculum even for men. Usually girls would receive their early education from attending the instruction of their brothers, and thus might acquire Greek, read Homer and some Latin poetry, and do some elementary exercises in Latin composition; but they would be married by the age that their brother moved on to a tutor in rhetoric. Cicero offers further evidence for women’s interest in philosophy, when he reports to Atticus that his friend Caerellia has pirated from Atticus’s copyists a prepublication copy of his work On Ends.

Caerellia, in her amazing ardor for philosophy no doubt, is copying from your people. She has this very work On Ends. Now I assure you (being human, I may be wrong) that she did not get it from my men. It has never been out of my sight.

(Cicero, Letters to Atticus 13.21a, (327); Shackleton Bailey 1965–66: 215)

Caerellia also corresponded with Cicero, who in his turn wrote routinely to provincial governors on behalf of her business interests. He had reason to oblige her, since he was literally in her debt (Letters to Atticus 12.51; Shackleton Bailey 1965–66).

Surely some of these educated and leisured women wrote poetry? Certainly Cicero in his defence of Caelius (64) makes fun of his enemy Clodia (on whom see Chapter 10) as a composer of dramatic Mimes, but his mocking use of the Greek word for “poetess” is more likely to be a witty metaphor for her intrigues and perjury. Clodia herself did not appear in court, but in this period of anomalies women are reported as speaking in court for the first time. Valerius Maximus reports that Maesia of Sentinum earned the name Androgyne for pleading in her own defense before the praetor. Her case probably belongs to the period of Sulla’s return, when Italian communities were stripped of civil rights; this was a period of lawlessness, in which men were on the run and women might have to defend themselves and their property from physical or legal attack (Marshall 1990). Less charitably, Valerius reports:

Afrania, wife of the Senator Licinius Bucco, was addicted to lawsuits and always pleaded her own case before the praetor, not for lack of friends to speak for her but because she was quite shameless. So from her constant harassment of the magistrate’s tribunals with this unnatural yapping she became a notorious example of female abuse of court, so much so that the very name of Afrania is used as a charge against women’s wicked ways. Her breath lasted out until the second consulship of Caesar with Servilius [46 B.C.E.].

(Valerius Maximus 8.3.2; trans. Elaine Fantham)

It was among the early achievements of the heroine we know as Turia (of whom more will be said in Chapter 11) that she drove bands of brigands away from the family estate and later vindicated her legal claim to it, but it is likely that Turia mobilized the household for defense without actually fighting, and financed and secured legal advocacy without appearing in court.

The most honored example of a woman speaker also emerges from the upheaval of civil war; Hortensia, daughter of a great orator and widow of the Republican Servilius Caepio, pleaded before the triumvirs in 42 B.C.E. to remove the special taxes imposed on the womenfolk of the proscribed. The historian Appian (second century C.E.) is probably drawing on his invention when he makes Hortensia argue the injustice of this tax on the basis of gender:

Why should we pay taxes when we have no part in the honours, the commands, the statecraft for which you contend against each other with such harmful results? “Because this is a time of war,” you say. When have there not been wars, and when have taxes ever been imposed on women, who are exempted by their sex among all mankind?

(Appian, Civil War 4.32; White 1979: 197)

Her eloquence and the unprecedented sight of noblewomen brutally driven away from the triumviral tribunal provoked such public indignation that the women won their concessions. Hortensia is admired, whereas Afrania is abused, because Hortensia was appealing in defense of a whole social group, before an irregular magistracy imposing an irregular tax (Snyder 1989, p 126).

But Appian’s civil war narrative, despite its gratifying tribute to wifely fidelity, cover a period of unprecedented disturbance, when an outlawed senator might have to hide in a sewer or a roofspace, or disguise himself as a charcoal burner to escape his assassins (cf. Civil War 4.13).

In this disturbance one woman herself became a military leader. Fulvia had been wife to the radical tribune Clodius and the Caesarian Curio before she married her last husband Mark Antony. (Cicero, who hated Antony, told him in public that he was doomed because he had at home the fatal monster that had killed Clodius and Curio before him). When Antony was commander in chief in the East, perhaps before his relationship with Cleopatra began, Fulvia combined with Antony’s brother Lucius to lead a rebellion of Italian cities against Octavius’s land confiscations (Babcock 1969). The story of their propaganda war has been revealed by the insults scratched on the slingshots of either side: “Octavius, you suck!” “Octavius the wide-arsed!” “L. Antonius and Fulvia, open wide your asses!” (Hallett 1977 pp 157–8). In Rome the ultimate insult to a man was “to suffer the woman’s lot”; that is, to be penetrated, and most vulgar abuse exploits this.

Yet it was Fulvia who summoned Antony’s friends with their armies and rallied the defenders of Perusia. When L. Antonius was defeated and forced to surrender, Fulvia finally slipped away to join Antony in Greece. She fell sick and died at Sicyon. With typical incomprehension Appian offers a hostile and trivializing obituary: “the death of this turbulent woman, who had stirred up so disastrous a war on account of her jealousy of Cleopatra, seemed extremely fortunate to both of the parties who were rid of her” (Civil War 4.55; White 1972).

Fulvia’s death freed Antony for a new marriage alliance, and Octavian used Octavia, the younger of his two sisters, in a vain attempt to make a lasting tie with his rival. As Plutarch describes her, Octavia was a model wife, reenacting the peacemaking role of the original Sabine brides, bearing her husband children, and even, in the style of the late Republic, securing him military forces.

Octavia had sailed with him from Greece, but at her request he sent her away to her brother when she was pregnant, having already borne him one daughter. She went to meet Caesar on the journey and taking his friends Maecenas and Agrippa with her, she met … and begged him not to neglect her, since from being a very happy woman she had become most wretched. For now all men looked to her as the sister of one commander and wife of the other. “If the worst should happen,” she said, “and war break out, it is uncertain which of you is fated to win and which to lose, but my role will be wretched in either case.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

When the agreement was made that Octavian should give Antony two legions for the Parthian war, and Antony should give Caesar a hundred warships, Octavia obtained over and beyond the agreement twenty swift ships from her husband for her brother and a thousand soldiers from her brother for her husband.… Antony took with him Octavia and his children by her and Fulvia, and set off for Asia.

(Plutarch, Antony 35; trans. Elaine Fantham)

In Plutarch’s last chapter, after Antony and Cleopatra are dead, Octavia is seen supervising the upbringing and marriages of all Antony’s children: his son by Fulvia, Iullus Antonius, she married to Marcella, her younger daughter by her first husband. Antony and Cleopatra’s daughter, Cleopatra Selene, she married to Juba of Mauretania. In turn she secured the marriage of her own daughters by Antony to Domitius Ahenobarbus, the grandfather of Nero, and to Octavian’s stepson Drusus, destined to be ancestor of two emperors, Caligula and again Nero. In his sister, Octavian had the best of models for the ideal of domestic loyalty that he would set before the women of Rome.

It would be fairer to the society of the late Republic to form a picture of the lives of aristocratic women from those living before the civil war. Here we must recognize two patterns of family structure unfamiliar to recent society: first the likelihood of marriages ending in the death of the husband (usually ten years older than his wife) or the young wife, as a consequence of childbirth; second an accepted pattern of divorce and remarriage, leading to a wide age spread between siblings and half-siblings growing up in the same household. Thus, for example, Octavian’s half-sister by his father’s first wife was ten years older than the younger Octavia, his full sister, while his mother’s remarriage to Marcius Philippus seems to have brought him further half-sisters (see Bradley 1991, chapters 6 and 7; analysis of key social factors, p. 171).

Even before the outbreak of civil war in 50, any well-born woman of the period might live through this sequence of remarriages; consider the best-known biography of a private woman—the life of Cicero’s daughter Tullia. Born in 76 B.C.E., she was married in her teens to a man in his late thirties, and lost him to a natural death when he was just over forty. After a brief union with the patrician Furius Crassipes, ending in divorce, she and her mother decided on her last disastrous marriage to Cornelius Dolabella during her father’s absence as governor of Cilicia, while he was still trying to find for her a husband not submerged in debt. Dolabella’s role as a supporter of Caesar may have helped the women after Pompey’s defeat but the man himself was useless. After the loss of Tullia’s first pregnancy they lived apart, and a year later Cicero seriously debated whether to press for divorce so that the baby she was carrying might be brought up by her family. But his own financial need, which prevented him completing the payment of the dowry, also obstructed the divorce. In 45 B.C.E. Tullia died of postpuerperal complications after bearing a son who probably died within weeks. She was just over thirty. But although Cicero never recovered from her loss and tried to erect a shrine in her memory, his many letters convey no idea of her personality. Was she gentle? Was she witty? Was she cultured? The famous letter of condolence from Servius Sulpicius, then governing a Greece ruined by Roman warfare, balances the little that the future had to offer a woman of her class against the conventional record of Tullia’s past satisfactions:

But I suppose you grieve for her. How often must you have thought, and how often it has occurred to me, that in this day and age they are not most to be pitied who have been granted a painless exchange of life for death! What was there after all to make life so sweet a prospect for her at this time? What did she have or hope? What comfort for her spirit? The thought perhaps of spending her life wedded to some young man of distinction? Do you suppose it was possible for you to choose from this modern generation a son-in-law suitable to your child? Or the thought of bearing children herself, whose bloom would cheer her eyes, sons who could maintain their patrimony, would seek public office in due course, and act in public affairs and their friends’ concerns like free men? Was not all this taken away before it was granted? The loss of children is a calamity, sure enough—except that it is a worse calamity to bear our present lot and endure.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Tell yourself that she lived as long as it was well for her to live, and that she and freedom existed together. She saw you, her father, Praetor, Consul and Augur. She was married to young men of distinction. Almost all that life can give, she enjoyed: and she left life when freedom died. How can you or she quarrel with fortune on that account?.

(Cicero, Letters to his Friends. 4.5 (248); Shackleton Bailey 1978: 248)

The vicarious achievements of Tullia’s past are not peculiar to this generation. Many recur in the moving elegy composed by Propertius for another Cornelia, the stepdaughter of Octavius who would become Augustus Caesar, but Cornelia could add pride in her three children to Tullia’s record of virtue and family glory. This is a man’s perception of a good woman, and it is men who gave this poem its title as “the queen of elegies,” but Cornelia’s account of her life is still worthy to be the last quotation, because it best represents the ideals and realities of life for the only women we come to know from the time of the Roman Republic, the women of the privileged and endangered ruling class. Like Hortensia she is depicted as speaking in her own defence—but before the last judgment of Hades:

THE DEAD CORNELIA ADDRESSES HER JUDGES

I was born to this, and when the wreath of marriage

Caught up my hair, and I was a woman grown,

it was your bed, my Paullus, that I came to

and now have left. The carving on the stone

says SHE WED BUT ONCE. O fathers long respected

victors in Africa, be my defense …

I asked no favours when Paullus was made censor:

no evil found its way within our walls.

I do not think I have disgraced my fathers:

I set a decent pattern in these halls.

Days had a quiet rhythm: no scandal touched us

from the wedding torch to the torch beside my bier.

A certain integrity is proof of breeding:

the love of virtue should not be born of fear.

Whatever the judge, whatever the lot fate gives me,

no woman needs to blush who sits at my side—

not Cybele’s priestess, Claudia, pulling to safety

the boat with the holy image, caught in the tide:

not the Vestal who swore by her robe she would rekindle

the fire they said she had left, and the ash blazed flame:

and most of all not you my mother, Scribonia—

all but the way of my death you would have the same …

For my children I wore the mother’s robe of honor;

It was no empty house I left behind.

Lepidus, Paullus, still you bring me comfort

you closed my eyes when death had made me blind.

Twice in the curule chair I have seen my brother;

they cheered him as a consul the day before I died.

And you, my daughter, think of your censor-father,

choose one husband and live content at his side.

Our clan will rest on the children that you give it,

Secure in their promise I board the boat and rejoice.

Mine is the final triumph of any woman,

that her spirit earns the praise of a living voice.

(Propertius Elegies 4.11; Carrier 1963: 191–92 excerpted)

If we are too conscious of a public voice, of a censor’s wife upholding official virtue; if these claims ring hollow because historians remind us that Cornelia’s mother Scribonia was deserted by Augustus the day after she bore him a daughter, who would herself submit to enforced dynastic marriages followed by exile and disgrace; if we follow the careers of Cornelia’s sons Lepidus and Paullus, to their consulships in 1 and 6 C.E.—the elder condemned to death for conspiracy, the younger “spared the perils of marrying a princess” (Syme 1939: 422)—this is to let the hazards of closeness to a rising dynasty blind us to the other, personal, values that Cornelia implies. We have deliberately broken off before the most moving and timeless part of her poem, where she turns to bid farewell to her husband and children. The reader may seek this out and read it privately.

Carrier, C. 1963. The Poems of Propertius. Bloomington Ind.

Hooper, W. D. and H. B. Ash. 1936. Cato and Varro: on Agriculture. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Horsfall, N. 1989. Cornelius Nepos: A Selection. Oxford.

Mandelbaum, A. 1961. The Aeneid of Virgil. New York.

Martin, C. 1979. The Poems of Catullus. Baltimore Md.

Michie, J. 1963. The Odes of Horace. New York.

Perrin, B. 1917. Plutarch: Lives. Loeb Clasical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Scott-Kilvert, I. 1979. Polybius: the Rise of the Roman Empire. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Shackleton Bailey, D. R. 1965–66. Cicero’s Letters to Atticus. Vols. 1–6, Cambridge.

——— 1978. Cicero’s Letters to his Friends. Vols. 1 and 2. Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Warner, R. 1958. Plutarch: the Fall of the Roman Republic Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

White, H. 1972 Appian’s Roman History Vol. 3, Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.

Babcock C. L. 1969. “The Early Career of Fulvia” American Journal of Philology 86: 1–32.

Beard, M. and M. Crawford, 1985. Rome in the Late Republic; Problems and Interpretations. London.

———, 1989 with J. North and S. F. Price, Pagan Priests. Cambridge.

Bradley, K. 1991 Discovering the Roman Family. Oxford.

Carp, T. 1983 “Two Matrons of the Late Republic.” Women’s Studies VIII 189–200, reprinted from H. P. Foley, ed., (1981) Reflections of Women in Antiquity. New York, 343–54.

Coarelli F. 1978. “La Statue de Cornélie, Mère des Gracches et la crise politique à Rome au temps de Saturninus” in Le Dernier Siècle de la République Romaine et L’Epoque Augustéenne. Strasburg 1978: 13–28.

Corbier, M. 1991. “Family Behavior of the Roman Aristocracy: Second Century B.C.-Third Century A.D.” Women’s History and Ancient History, ed. S. B. Pomeroy. Chapel Hill, N.C. 173–95.

Crawford, M. 1976. Roman Republican Coinage. Cambridge.

Crook, J. A. 1967. Law and Life of Rome. Ithaca, N.Y.

Delia, D. 1991. “Fulvia Reconsidered,” Women’s History and Ancient History, (see Corbier) 197–217.

Degrassi A. 1963–65. Inscriptiones Latinae Liberae Rei Publicae. Florence.

Dixon, S. 1984. “Family Finances: Tullia and Terentia,” Antichthon 18, 78–101.

———, 1985a “The Marriage Alliance in the Roman Elite,” Journal of Family History 358–78.

———, 1985b “Polybius on Roman women and Property,” American Journal of Philology 106: 147–70.

———, 1989. The Roman Mother. Norman, Okla.

Evans, J. K. 1991. War Women and Children in Ancient Rome New York.

Gardner, J. F. 1986. Women in Roman Law and Society Bloomington, Ind.

Hallett, J. 1977. “Perusinae Glandes and the changing Image of Augustus, American Journal of Ancient History 2: 151–71.

Kleiner, D. E. E. 1977. Roman Group Portraiture: The Funerary Reliefs of the Late Republic and Early Empire. New York.

Marshall, A. J. 1990. “Roman Ladies on Trial: the Case of Maesia of Sentinum” Phoenix 44: 46–59.

Phillips, J. E. 1978. “Roman Mothers and the Lives of Their Adult Daughters,” Helios 6: 69–80.

Pomeroy, S. B. 1976. “The relationship of the married woman to her blood relatives at Rome,” Ancient Society 7: 215–27.

Rawson, B., ed. 1986. The Family in Ancient Rome: New Perspectives. Ithaca, N.Y.

———, ed. 1991 Marriage, Divorce and Children in Ancient Rome. Oxford.

Sailer, R. 1984. “Familia, domus and the Roman conception of the Family.” Phoenix 38: 336–55.

——— 1986 “Patria potestas and the Stereotype of the Roman Family” Continuity and Change 1: 7–22.

Scafuro, A., ed. 1989 The Women of Rome. Helios I and II

Snyder, J. M., 1989. The Woman and the Lyre: Women Writers in Classical Greece and Rome. Carbondale, 111.

Treggiari, S., 1984. “Digna condicio; Betrothals in the Roman Upper Class.” in Studies in Roman Society, Classical Views/Echos du Monde Classique 3: 419–51.

——— 1991 “Divorce Roman Style: How easy and how frequent was it?” in Marriage, Divorce and Children, ed., B. Rawson, 47–68.

Corbier, M. 1991. “Divorce and Adoption as Roman Familial Strategies, in Marriage Divorce and Children in Ancient Rome ed., B. Rawson. Oxford 47–78.

Dixon, S. 1991. “The Sentimental Ideal of the Roman Family.” In Marriage Divorce and Children ed., B. Rawson 99–113.

Fantham, E. 1991. “Stuprum: Public Attitudes and Penalties for Sexual Offences in Republican Rome,” Classical Views/Echos du Monde Classique 10: 267–91.

Gardner, J. F. and T. Wiedemann 1991. The Roman Household. Oxford.

Hallett, J. P. 1982. Fathers and Daughters in Roman Society: Women and the elite family Princeton, N.J.

Treggiari, S. 1981. “Concubinae,” Papers of the British School at Rome 49: 59–81.

——— 1991. Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges. Oxford.

Watson, A. 1967. The Law of Persons in the Later Roman Republic. Oxford.

——— 1971. Roman Private Law around 200 B.C. Edinburgh.