Introduction

Returning Unity to Yoga

with the Seasons

If over the millennia yoga had been handed down from mother to daughter through a female lineage, what would an authentic women’s yoga be like?

This was the unanswered question that beckoned me onto the path of Seasonal Yoga. Patanjali is considered the father of yoga, and over the millennia yoga has been handed down from father to son, through a male lineage. If Patanjali had had a sister, what is the yoga she would have handed down to us? And if her wisdom had been included in the yoga canon, how would we be different, both on and off our yoga mats? During a period of meditation, I asked (an imaginary) Patanjali’s sister for guidance on creating an authentic united yoga. This is the answer that came back to me: “Listen to the earth—that’s all. Listen to the earth.”

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are divided into four padas, and this gave me the idea to divide my inquiry into one pada for each season of the year: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. That is how the seed of Seasonal Yoga was born.

Understanding the Division of Yoga

My quest to discover a reunited yoga led me to read stories that explained the origins of our male-female division, telling of how women had been spiritually disenfranchised. It appears that Patanjali’s sister would have been forbidden to study the sacred texts or to recite mantras, and because she was considered inherently sinful and impure due to her cycles and connection with the earth, she would not have been an appropriate candidate for sacred knowledge.1

Because of these things, it is interesting to realize that there is legend of feminine energy within the origins of yoga. I read books that told a fascinating story of how once upon a time God had been considered to be a woman.2 Hindu scriptures say that the Goddess invented the alphabet and inscribed the first written words onto slabs of stone.3 That it was women who mapped out the stars and the phases of the moon. That in days gone by her blood had been regarded as holy and her fertility was a cause for celebration and pride. And that both he and she had tended the sacred fire and that the thread of sacred knowledge was held in trust and passed down through the generations, by both him and her. At one time the earth itself was revered as a goddess and the sacred was discovered through our everyday lives on earth.

I also read fascinating tales of the mother origins of yoga. Patanjali is oftentimes referred to as the father of yoga. What is less well known is that Patanjali had a mother and that she was called Gonika.4 Gonika was a wise woman and she was looking for someone upon whom to bequeath her knowledge of yoga. One day as she stood by a waterfall that flowed into a river, she scooped up a handful of river water into the cupped palms of her hands, and in a worshipful gesture she offered the water to the sun, saying, “This knowledge has come through you; let me give it back to you.” Into her praying hands a serpent fell from heaven, and she called him Patanjali. Pata means both “serpent” and “fallen”; anjali is the worshipful gesture of her cupped hands.

Patanjali did not “father” yoga; rather, he organized the knowledge of yoga that had been handed down to him by his mother, Gonika, into the Yoga Sutras. Legend has it that the yoga that both Patanjali and Gonika inherited was born from the womb of the earth itself. The womb of creation gave birth to the yoga that has been passed down through the generations.5

Even though yoga came with this sense of unity, it was lost along the way. Around 200 CE the sage Patanjali compiled the Yoga Sutras, a collection of 196 aphorisms outlining a systematic guide to the practice of yoga. These bite-size chunks of knowledge were passed down orally through the male lineage from father to son.

Patanjali was affiliated with the principles of the classical Sâmkhya, a school of thought that proposed that existence consisted of two primordial, interdependent principles: purusha, pure consciousness, which is gendered male, and prakriti, nature incarnate, which is gendered female. Purusha is the observer and prakriti is the observed—the seer and the seen. Prakriti is the feminine principle, she who gives birth to and creates the manifest world of matter. The aim of yoga, as outlined in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, is to reach a state of enlightenment by transcending nature. It is a dualistic, transcendent philosophy that outlines the steps required for the yogi to disentangle himself from the natural world and so attain a state of pure consciousness (samadhi).

The yoga of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, known as Raja Yoga, the royal path, presents us with a path of transcendence that places the masculine spirit (purusha) above feminine matter (prakriti). Hence, a schism develops between the natural and the spiritual world. Heaven and earth no longer coexist; they are now on parallel lines destined never to meet. Women are considered to be closer to the earth; they menstruate and give birth and so are considered to be impure; they are also considered to be inherently sinful and so not suited to following the spiritual path. Men are considered to be closer to heaven; they no longer worship the earth; now they worship sky gods. The yoga canon created from this divorce of genders over millennia was devised by a group of people who had never experienced menstruation, pregnancy, giving birth, breastfeeding, or menopause, and so it was only one half of a united experience.

Reinventing the Wheel of Yoga

Why does it matter what the attitudes toward women were when Patanjali was compiling his Yoga Sutras? Surely today’s yoga has moved beyond all this? And yet we are constantly advised to check that the yoga that we practice has an authentic lineage, which will be a male lineage passed down from father to son over millennia.

To create an authentic united yoga we must reunite heaven and earth, and then once again we will rediscover the spiritual within our everyday lives. Spirit no longer transcends the everyday world; rather, it is immanent and found to be within all living things. When women and the earth are rejected as impure and unspiritual, we create a hell on earth. When all genders and the earth are respected and embraced as an important part of spiritual life, we create heaven on earth.

The good news is that we can choose to unite our efforts to a yoga that is healthful, wholesome, and healing. Every time we step onto our yoga mats we can choose to reinvent yoga. With each breath, with each movement, we learn to listen to and love our body and to respect our own and the earth’s natural rhythms and cycles. In this way yoga has the potential to be the balm that heals and makes us whole again. Of course, as in acquiring any other skill, it requires practice and discipline. When we reimagine yoga, we all are the richer for it. All genders can then enjoy a yoga that has been made whole again. Heaven and earth are reunited.

Uniting Yoga with the Ebb and Flow of the Seasons

The word yoga can be translated as “union,” as in a marriage. This union, or marriage, between complimentary opposites helps us find balance in our lives. Hatha Yoga teaches us to look within our self and to discover within our own body the energies of both the sun and the moon. Through our yoga practice we learn to balance our ha, solar energy, and our tha, lunar energy.

The sun is, quite naturally, at the center of our Seasonal Yoga inquiry. Planet Earth rotates on a tilted axis and revolves around the sun. It is this journey of our planet spinning its way around the sun that gives us the alternating cycles of night and day, light and dark, summer and winter.

Modern-day life in the twenty-first century is fast-paced and unrelenting. We can be turned on and tuned in twenty-four hours a day. Our 24/7 society means that many of us work longer and more unsociable hours, which can take a heavy toll on body, mind, and soul. The boundaries between public space and private space have become blurred; and so, it can be more difficult to withdraw and simply take time out just to be. We recognize that there are many benefits to modern-day living, but our health is endangered when we disconnect from our own and the earth’s natural rhythms. When we marry seasonal awareness with our yoga practice, a path that leads to a saner, healthier, more balanced, and more harmonious way of living is revealed to us.

The Equinoxes and Solstices

There is an ebb and flow to our lives: the sun rises, the sun sets; tides rise and fall; the moon waxes and wanes. A flower, our heart, the moon, the sea—all these things have a rhythm. A flower opens and closes its petals in response to dawn and dusk. The year ebbs and flows in a perpetual dance of sunlight and shadow. Like the moon, the year also has periods of waxing and waning. An awareness of this ebb and flow of the year can help us know when it is a good time to push forward and take action and when it is better to take a more contemplative approach. It also helps us feel connected to and supported by the earth.

On the one hand, our yoga practice takes us on a journey inward that leads us along a path that spirals into the very center of our being, and the prize is self-knowledge. On the other hand, when we develop an awareness of, and a connection to, the seasons, we are led along a path that spirals outward and leads us to attaining knowledge of the world and beyond. Our yoga practice reveals to us a cosmos within ourselves that is a mirror image of the outer cosmos. Our seasonal awareness connects us to the outer world as it is in the here and now. With dedicated and sincere practice of both yoga and seasonal awareness, we gain an enlightened realization of the nature of our true selves and of the world.

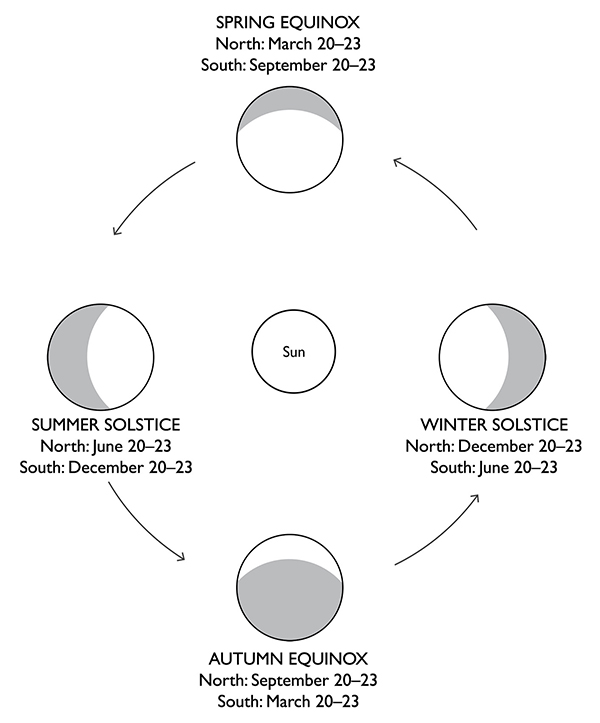

One of the simplest ways of developing a seasonal awareness is to become aware of and to observe the four cardinal solar points around the wheel of the year. These are the two solstices and the two equinoxes.

• The winter solstice is when we have the shortest day.

• The summer solstice is when we have the longest day.

• The spring equinox is when day and night are of equal length before we tip into the lightest phase of the year.

• The autumn equinox is when day and night are of equal length before we tip into the darkest phase of the year.

Broadly speaking, for our Seasonal Yoga inquiry we can divide the year into two halves. Between the winter solstice and the summer solstice is the “light” half of the year, when the days are getting longer. Between the summer solstice and the winter solstice is the “dark” half of the year, when the nights are getting longer. Your first steps on the path of Seasonal Yoga might be to simply work with the wheel of the year to develop an awareness of where you are energy-wise in the year. You can then pinpoint whether you are in the lighter or darker half of the year and whether the sun’s energy is waxing or waning.

The light half of the year, between the winter solstice and the summer solstice, can be compared to the inhalation. It is energizing, is expansive, and supports activity. It is associated with sunlight, fire, radiating, expansion, waxing, pushing, effort, action, extroversion, and outer activities.

The light half of the year takes us from the heart of winter to the height of summer. During this time, the sun’s energy is waxing, the light is expanding, and the days are getting longer and warmer. We move from winter into spring and then into summer. This is the growing season, and seeds that are planted now will grow and expand. Generally speaking, this light half of the year favors an outward focus, with an emphasis on action and outward achievements. We use the season’s fiery, expansive energy to make things happen and to get things done. During the light half of the year, our yoga practice can help us stay connected to our inner wisdom and be guided by it when taking action in the world.

The dark half of the year between the summer solstice and the winter solstice can be compared to the exhalation. It is relaxing, regenerating, renewing and supports letting go. It is associated with moon, night, waning, drawing inward, yielding, incubation, hibernation, reflection, contemplation, rest, and regeneration.

The dark half of the year takes us from the height of summer into the depths of winter. During this time, the sun’s energy is waning, the dark is expanding, and the days are getting shorter and nights longer. We move from summer to autumn and into winter. As autumn and winter progress, nature starts to gradually die back, and we enter a period of dormancy and decay. Broadly speaking, the dark half of the year favors an inward focus, with an emphasis on contemplation and rest. We use the watery energy of the season to incubate ideas, to find rest and renewal, and to dream and plan. During the dark half of the year, our yoga practice can help us remain positive and stay connected to our inner light.

As we gain more experience working with the wheel of the year, we learn to recognize and work with the season’s alternating cycles of light and dark, and to more skillfully ride the prevailing energy of the season. The common thread that runs through both our yoga practice, and our work with the seasons, is that both disciplines teach us the wisdom of when it is better to push and when it is better to yield.

In his Yoga Sutras Patanjali has very little to say about the practice of asana, other than in Yoga Sutra 2:46: Sthira-sukham asanam, or “Asana must have the dual quality of alertness and relaxation.” 6 In other words, we maintain a state of equanimity in a challenging yoga pose by learning to balance pushing and yielding. In yoga this is referred to as balancing effort (sthira) with relaxation (sukha). The word sthira can be translated as steadiness, firmness, alertness, strength, or effort. The word sukha can be translated as comfort, agreeable, flexible, or relaxation.

As you become more experienced at recognizing the prevalent pushing or yielding energy of the season, you will also fine-tune your ability to choose yoga practices that balance your own energy flow. For example, in winter there is a natural tendency to want to hibernate, so you might honor this by choosing restful, restorative (langhana) poses. On the other hand, in winter you might also want to choose energizing (brahmana) poses to boost your happy hormones and ward off the winter blues.

When practicing yoga, the breath provides a perfect barometer to measure whether we have achieved the correct balance between effort and relaxation. Our yoga practice teaches us to ride the ebb and flow of the breath, which in turn prepares us to skillfully ride the ebb and flow of the seasons in an ever-changing world. We learn to befriend and observe the breath, and the quality of the breath gives us clues to whether we are putting in too much or too little effort. If the breathing becomes ragged, labored, or erratic we know that our practice has become too effortful and we need to balance this with a more relaxed approach. We are aiming for a long, smooth, even, calming breathing pattern.

The beauty of the Seasonal Yoga approach is that it is tailor-made to fit your needs during every season of the year. Each of the seasonal chapters in this book will help you familiarize yourself with the prevalent energy of the season and show you how you can use this awareness to create balance in both your yoga practice and your life.

How to Use This Book

You can dip into this book all year round to find seasonal inspiration and guidance. Each of the eight seasonal chapters consists of the following elements:

• Summary of the relevant seasonal themes and pointers for how best to work with the opportunities and challenges of the season

• Yoga practice inspired by the season

• Seasonal meditation or visualization

• Tree wisdom section

• Set of seasonal meditation questions

Although most of the elements of the book are self-explanatory, to get the full benefit of the book, I recommend that all readers start by reading Chapter One. After that, you could either read through the whole book, which will give you a feel for the Seasonal Yoga approach, or dip into the book season by season to get ideas for the season you are in.

The various mindfulness exercises, visualizations, meditations, and yoga practices in this book have all been chosen to be specifically relevant for a particular season. However, if you like a particular practice, it’s fine to use it throughout the year.

I hope that this book is one that you will return to often over the seasons and across the years. Each time you use the methods outlined in the book you will increase your confidence to tune in to and align yourself with the seasonal energy, and you will gradually, over time and with experience, establish your own rhythm of responding to the changing seasons. I hope that the outcome of this is that you learn to care for yourself, your loved ones, and the planet in a sustainable, loving, and compassionate way.

1. Lynn Teskey Denton, Female Ascetics in Hinduism (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2004), 25.

2. Merlin Stone, When God Was a Woman (Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace, 1976).

3. Barbara G. Walker, The Women’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1983), 685.

4. B. K. S. Iyengar, The Tree of Yoga (London: Thorsons, 2000), 74.

5. Georg Feuerstein, The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy and Practice (Prescott, AZ: Hohm Press, 2001), 214.

6. T. K. V. Desikachar, The Heart of Yoga: Developing Personal Practice (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International, 1995), 180.