COLOUR PLATES

Pl. 1 A line of eland antelope moves past low cliffs with painted rock shelters and up into the San spiritual hinterland that lies beyond the high peaks.

Pl. 2 In the 18th and 19th centuries travellers and explorers, such as the artist Thomas Baines, came across the impoverished remnants of San groups.

Pl. 3 Today, San groups living on the fringes of more complex economies still practise the trance, or healing, dance. As the women clap the rhythm, the feet of the dancing men make a rut in the sand.

Pl. 4 In the Drakensberg mountains large rock shelters beneath sandstone cliffs were occupied by the San, and they made their paintings there.

Pl. 5 On a rock in the shelter shown in Plate 4 the San painted a multitude of eland. Why did they think it necessary to depict so many eland?

6 In this dance clapping women stand on either side of dancing men who bend forward and support their weight on dancing sticks.

Pl. 7 A painting of a circular trance dance. The curved line may represent the dance rut or a hut in which there is a sick person and three clapping women. The pointing finger indicates the shooting of supernatural potency.

Pl. 8 The eland was believed to have more supernatural potency than any other animal. The San painted it in various ways. It is here represented in lateral view. (see also Pl. 9).

Pl. 9 The eland was believed to have more supernatural potency than any other animal. The San painted it in various ways. In this painting, it is depicted in lateral view. (see also Pl. 8).

Pl. 10 The eland was believed to have more supernatural potency than any other animal. The San painted it in various ways: here with its head turned to look backward.

Pl. 11 The eland was believed to have more supernatural potency than any other animal. In this painting, the San have represented it lying down.

12 Transformation is a theme in San rock art. Flying creatures are common. In this painting, a figure with a white face has emanations from the back of its neck. Its arms have white feathers.

13 Transformation is a theme in San rock art. Flying creatures are common. The ‘swift-person’ in this image has a forked tail and complex wavy lines in its body.

14 Joseph Orpen’s article ‘A glimpse into the mythology of the Maluti Bushmen’, published in 1874, illustrated four groups of San rock art images. The Sehonghong rain-capture scene [see Figs 30–31] is in the top right corner of the fold-out.

15 The high Drakensberg over which Orpen’s expedition climbed in 1873.

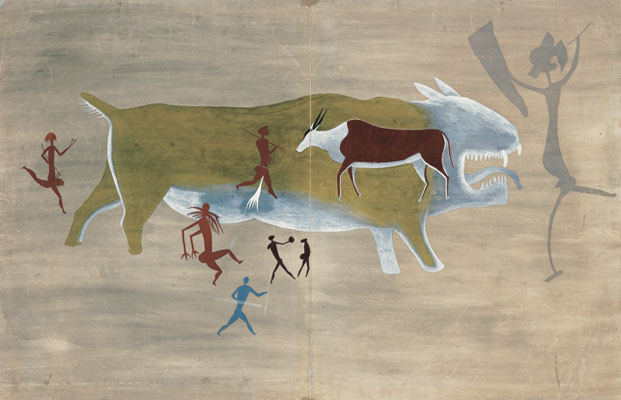

16 One of George Stow’s 1870s copies of rain-animals (see also Pls 17–18). It was through these copies that the Bleek family first learned of San beliefs about rain-making.

17 One of George Stow’s 1870s copies of rain-animals (see also Pls 16, 18). It was through these copies that the Bleek family first learned of San beliefs about rain-making.

18 One of George Stow’s 1870s copies of rain-animals (see also Pls 16–17). It was through these copies that the Bleek family first learned of San beliefs about rain-making. In this painting a man bleeds from the nose as he holds his arms in the backward posture.

19 A San man apprehends a rain-animal in a way that is comparable to the action depicted in Pl. 18.

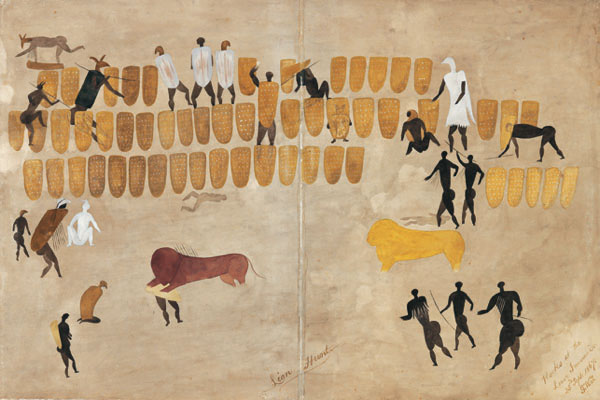

20 George Stow’s copy of the complex panel shown in Plate 21. Stow rearranged many of the images. In the painting itself a tusked serpent can be seen emerging from a facet in the rock face (see Pl. 21 and Fig. 37).

21 Scene copied by George Stow in Plate 20. A tusked serpent can be seen emerging from a facet in the rock face (see also Fig. 37).

22 In a hollow beneath a boulder a San artist painted a lion with a long tail pursuing a number of men (Pls 23–24, Fig. 40).

23 In a hollow beneath a boulder (Pl. 22) a San artist painted a lion with a long tail pursuing a number of men (Fig. 40). One of the antelope-headed flying figures is shown in Plate 24.

24 In a hollow beneath a boulder (Pl. 22) a San artist painted several antelope-headed flying figures, one of which is shown here. It bleeds from the nose. This detail forms part of the scene depicted in Plate 23 and Figure 40.

25 A coloured photograph of eland and a dead rhebok around which people dance. A swarm of bees can be seen. A ‘thread of light’ leads from a hartebeest on the right to a flying creature on the left.

26 A ‘freezingly cold mist’, here seen from above, lies between the level of the rock shelters and the summits of the high Drakensberg (Fig. 27). It was ‘the rain’s breath’ and guarded the place where the San trickster-deity lived with his vast herds of eland.

27 A ‘freezingly cold mist’, here seen from below, lies between the level of the rock shelters and the summits of the high Drakensberg (Fig. 26). It was ‘the rain’s breath’ and guarded the place where the San trickster-deity lived with his vast herds of eland.

28 A hilltop in the semi-arid terrain where the /Xam San lived. A waterhole can be seen in the left-hand end of the ravine. Rock engravings are in the foreground; they overlook the waterhole.

29 A transformed San shaman stands next to an upside-down buck, a source of supernatural potency. He has blood coming from his nose and antelope hoofs. He holds a long stick and a flywhisk. A ‘thread of light’ hangs around his body. He is in the San spirit realm.