CHAPTER 6

Truth Hidden in Error

The lion on the other side belongs to the other lot of people.1

In the list of illustrations at the beginning of George William Stow’s The Native Races of South Africa (1905), Plate 10 is mistakenly described as ‘Bush-man Painting of Elands and Lions’.2 In the original rock painting there are no lions. The erroneous description was probably written by Lucy Lloyd, who selected some of Stow’s copies for inclusion in his posthumously published book. Some 30 years before, Stow had himself fallen into the same trap when he commented on what eventually became Plate 12 of Rock Paintings in South Africa (1930),3 the focus of this chapter (Pl. 20). In this instance, he believed that he could detect not just depictions of lions but, in addition, accoutrements of a lion hunt. His comment differs from those of a Cape /Xam San informant on the same copy in a way that illustrates the chasm between a Western predilection to discern rather crude narratives in the arts of small-scale societies and the subtlety and elusiveness of those cultures’ thought.

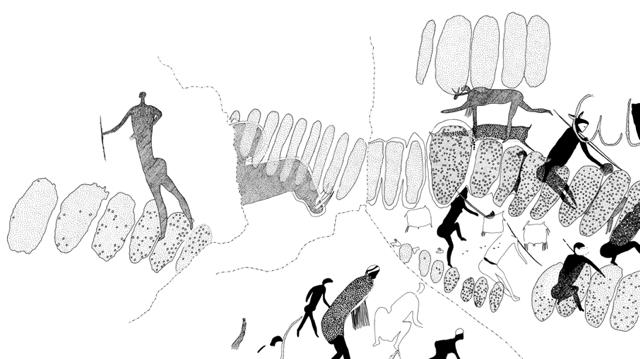

Today, we know that, as in many of his copies, Stow rearranged the images in Plate 20 and, in doing so, created false groupings. A far more accurate copy made by the German ethnographer and explorer Leo Frobenius4 in the 1920s and our own tracing of the images made in 2009 (Fig. 37) both show that the elongated ovals are not arranged in such uniform lines, nor are they as regularly shaped as Stow has them. More significantly, he completely rearranged the right-hand side of the panel. Of the many images that he did not include, we point to the head and neck of a serpent that appear to issue from a crack in the rock face just to the left of his copy (compare Pls 20 and 21 with Fig. 37). As we show in this chapter, it is key to understanding the panel as a whole.

Believing that San rock art in general was a literal representation, or ‘history’, of daily life,5 Stow began his personal explanation of Plate 206 by saying that he detected a lion hunt and that the rows of oval shapes depicted shields that the San made from eland hide and used:

especially in attacking the lion, when this piece of defensive armour was fastened on to their backs, so that should the brute spring upon them they threw themselves on the ground and drew themselves up under it after the manner of the tortoise, and thus afforded their companions an opportunity of rescuing them.7

Stow’s essentially literal approach to the art led him astray. In the first place, there is no evidence that the San hunted lions. Generally, they gave them a wide berth and even left meat for them after a kill so that they would not pursue the departing hunters.8

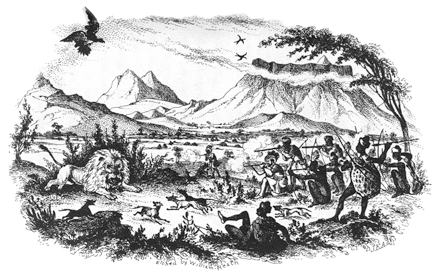

Stow’s lion-hunting explanation receives a more fundamental blow. The two supposed ‘lions’ are in fact the remains of partially faded eland paintings.9 His mistaken understandings of them are at centre left and right of Plate 20. The white paint that the San used to depict the neck, dewlap, head and lower legs of an eland fades more swiftly than the red used for the rest of the body. As a result, the bulky hump of the eland that remains after the white paint has disappeared has sometimes been mistaken for a lion’s head and mane. To emphasize this interpretation, Stow added lines at the neck to separate it from the mane: there are no such lines in the image itself; he deliberately doctored his copy to suit his perception that they were lions. Sometimes, though not here, the red line along an eland’s neck projects from the hump and confirms the species depicted. Figure 3810 shows how early travellers pictured a lion with a large mane; parallels between this illustration and partially preserved San paintings of eland are clear. Indisputably, the images in question do not depict lions. Just as there are so few scenes that can be identified as ‘antelope hunts’,11 so another supposed painted ‘record’ of the San’s way of life falls away. Moreover, why did the San painter depict so many finely detailed ‘shields’ in three rows (there are over 50)? Stow offers no explanation. (We label the ‘shields’ as ‘scutiforms’ because their general shape may be said to resemble shields.)

37 A recent tracing of the panel of images shown in Stow’s copy (Pl. 20) and in the photograph in Plate 21. In the centre, a serpent with tusks emerges from the rock face. Colours: see Plate 21.

38 An etching of a lion hunt in colonial times, published by Sir James Alexander in the 1830s. The large mane of the lion, especially noted by early travellers, was sometimes thought to be suggested by the hump of partially preserved San rock paintings of eland antelope.

Not surprisingly, Lucy Lloyd’s /Xam informant did not confirm Stow’s view, but he did follow the copyist’s mistaken identification of lions. Probably Lloyd (who, it will be remembered, had never seen any rock paintings) was influenced by Stow’s interpretation of these partially preserved images and consequently told her informant that they depicted lions. Then we must also recall that the informant himself was unfamiliar with the conventions of rock paintings in the region where Stow worked. He was therefore not in a position to contradict Lloyd. He simply accepted that two of the images in Plate 20 depicted lions. Now, in retrospect, we may add ‘fortunately’, because his error led to some fascinating insights.

A brief remark

Fifty years after Lloyd recorded the San comments, her niece, Dorothea Bleek, was puzzled when she came to prepare Stow’s copies for publication. Understandably, she described the informant’s observation on Plate 20 as a ‘rather incomprehensible interpretation’:

Lion to the right. His daughter in white close to it. The lion on the other side belongs to the other lot of people.

At first glance, this puzzling statement may seem to be a prosaic identification of a species (lions), as is the case with San comments on other copies of rock paintings.12 But it differs from those explanations because, in this instance, the informant went on to point to baffling relationships between the supposed lions and the people depicted adjacent to them. Fundamentally, whatever he may have meant by ‘daughter’ and ‘belongs to’, he did not see the images as simply reflecting daily life. Though brief, the statement is pregnant with meaning.

The informant’s comments are thus paradoxically both incorrect and correct. He was incorrect in that the two images in question do not depict lions: they are eland. He was, however, correct in the sense that his initially puzzling statement expresses genuine San beliefs about lions. We are therefore left asking: How can a lion be said to have a ‘daughter’? In what sense can a lion ‘belong’ to a group of people? The answers to these questions lead us to a set of San beliefs that illuminate other rock paintings in which lions are indisputably depicted. We consider one of them towards the end of this chapter. But now we need to examine how the informant’s error opened up a far-reaching line of inquiry.

The San and lions

For the San, the lion was much more than a dangerous predator. It was fearfully associated with the spirit realm.13 Megan Biesele14 says that, for the Ju/’hoan San, lions are ‘the ancient dark enemies of human beings’, and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas found that the Ju/’hoansi ‘treated the lions and the gods in somewhat the same way’. If the Ju/’hoansi chanced upon a lion, they addressed it as n!a (‘big’ or ‘old’), a term that they use when speaking of the gods.15 As is the case in numerous societies, the San employed avoidance, or respect, words when referring to powerful things or beings. Nineteenth-century /Xam children, for instance, were taught to avoid the word for lion, //khã, and use instead /kuken, which means ‘hair’.16 The hair around a lion’s paw, unlike, say, a dog’s, makes small diagnostic prick marks in the sand; as //Kabbo put it, ‘a lion’s feet are hairy; a dog’s feet are not hairy’.17 For the San, spoor (tracks) are important; they believe that there is a close association between an animal and its spoor. For instance, when hunting an eland, they take care not to cross the antelope’s spoor in case they frighten the animal in some mystical way (Chapter 9).18

Another /Xam avoidance word for lion was /kerre-/e. Lloyd translated it as ‘lighting in’.19 The exact meaning of /kerre-/e is unclear, but her translation suggests, we believe rightly, something intangible, ethereal. The /Xam also used the phrase tsá a: /na: /hoken e. Literally, taken word by word, it means ‘thing whose head black/dark is identical with’. The /Xam used /hoken to denote any dark colour, but, generally, the word has connotations of danger and inimical influences. Lloyd translated the whole phrase as ‘thing whose head’s darkness it is’. In both this phrase and /kerre-/e light is played off against darkness. /Han≠kasso explained why his people used these two complementary phrases: ‘for we feel that it walks at night after lying asleep while the sun was up’.20 Moreover, the nocturnal lion was believed to have the supernatural ability to cause the sun to set and thus to bring darkness in which it could conceal itself.21 Being both nocturnal and diurnal, such lions bridged the opposition night/day.

Perhaps the bright shining of a lion’s eyes in the darkness beyond the light of a campfire suggests why it was called ‘lighting-in’. As one /Xam man put it: ‘Dost thou not think (that) our fathers also said to me, that the lion’s eye can also sometimes resemble a fire at night?’22 (original parenthesis). According to the /Xam, failure to use either /kerre-/e or the phrase tsá a: /na /hoken e as an avoidance word could cause the flies, who overheard everything, to tell the lion that he had been disrespected (owls and crows performed a similar function).23 He would then come in the night and snatch the miscreant from his hut.24 Moreover, offended lions knew where to go to find the man with whom they were angry because they had the ability to acquire knowledge through dreams, as, too, did San shamans.25 Lions were believed to be sentient creatures with supernatural abilities.

The /Xam also believed the lion to have another mystical ability that is difficult to understand, but that may be related to both /kerre-/e and the longer phrase tsá a: /na /hoken e. /Han≠kasso told Lloyd: ‘When the lion is still coming, his head’s reflection comes in sight before him, it looks like a real lion. His head’s reflection (it is) with which he deceives us’26 (original parenthesis). The word /Han≠kasso used was /hu/hunta. Dorothea Bleek’s Bushman Dictionary gives /hu/hunta tentatively as ‘image (?), shadow (?), reflection (?)’ and exemplifies it with only the passage I have quoted;27 it was not a common word. Even though we may not fully understand the meaning of /hu/hunta, we can see that the lion was believed to adopt a supernatural form, a mystical simulacrum, in order to deceive people.

That ‘mirage’ is only part of the lion’s transformative powers. It shared with shamans an ability to transform itself in other ways. For instance, it could turn itself into a hartebeest in order to trick hunters to follow it; then, when they came close to it, the animal turned back into a lion, causing much terror.28 It also turned itself into a person by putting ‘its tail over its head: then it trots (along) like a man’29 (original parenthesis). The /Xam believed that lions had a supernatural ability to become like people.

Lions and shamans

The other side of the coin is people, more precisely shamans, turning into lions. The San believed that any lion encountered in the veld could be a transformed shaman, especially if it behaved in a strange way. For instance, in a story about a young man who was carried off by a lion, we learn that a lion that does not die after being wounded is actually a ‘sorcerer’ (!gi:xa) in his leonine incarnation.30 This sort of transformation was sometimes evident when a shaman healed people by sniffing (‘snoring’) sickness out of them: he made a noise like a lion.31 A lion, or perhaps a shaman in that form, could enter into a man and cause sickness. Another shaman, who was healing a sick man, ‘snored’ the lion out of him. When this happened, the healer himself became like a lion and tried to bite people: ‘Then people give him buchu to smell, and he sneezes the lion out.’32 Moreover, it was said that lion’s hair grew on the back of a shaman in violent trance; people rubbed fat on him to remove the hair and sang protective songs to calm him.33 If people did not take care of a trancing shaman in this way, he would turn into a lion.34 There was thus a dangerous transferral of leonine qualities from the sickness to the shaman.

Indeed, one shaman, !Nuin-/kúïten, killed a settler’s ox while on a nocturnal /xãun, a word that Lloyd translated as ‘magical expedition’ – one of what she called the ‘deeds of sorcery’ (Chapter 3).35 The farmer pursued him and fatally wounded him. Before all this happened, !Nuin-/kúïten tried to avoid strife in his camp by concealing his lion’s body from other people.36 But he was not entirely successful. Diä!kwain recalled: ‘My father used to tell me what !Nuin-/kúïten used to do when he became a lion, he walked treading upon hair (lion’s hair)…. For it looks as if someone big has gone along here…. [W]e see his spoor’37 (original parenthesis). Shamans were so much like lions that they, too, were believed to ‘walk on hair’.

Present-day Kalahari San retain the belief that a shaman can transform into a lion. One man told Richard Katz: ‘These great healers went hunting as lions, searching for people to kill…. When a healer changes into a lion, only other healers can see him. To ordinary people he is invisible.’38 Another man said: ‘When I turn into a lion, I can feel my lion-hair growing and my lion-teeth forming. I’m inside that lion, no longer a person. Others to whom I appear see me just as another lion.’39 Mathias Guenther also found that, among the San, ‘the lion was a trance dancer’s most common spirit incarnation’.40 Conversely, lions are unable to distinguish between themselves and shamans in leonine form; a man who can turn into a lion is able to go out and mix with a pride of lions.41 These are the experiences of benign shamans. The moment of incarnation is, however, so complete and intense that onlookers feel it as much as the shaman himself.42

Lorna Marshall learned that malevolent shamans too ‘can take the form of lions and fly through the air’43 – the /xãun, or out-of-body journeys, of which the /Xam spoke. The Ju/’hoansi use the word jom to mean a pawed creature and, as a verb, to travel abroad in the form of a lion and perhaps kill people.44 The Nharo San take this idea further. They use the phrase xam.ti.≠xíí to denote a shaman; it means ‘lion’s eye’ and refers to a shaman’s ‘supposed ability to travel across the sky as a shooting star’45 – another reference to light and lions’ eyes.

When a nocturnal trance dance is taking place, lions are often heard roaring in the darkness beyond the firelight. Guenther caught the essence of these unnerving moments: ‘Their roars add to the sense of awe and dread that hangs over people at this moment [of transformation] in the dancer’s experience, as it complements mystical peril from spirit beings with potential real danger from actual animals.’46 In the Kalahari today, when San people refer to ‘an eerie or strange time’, such as an eclipse, they use the expression, ‘Lions are walking.’47

Lions and human communities

These beliefs about lions and shamans are central to San thought. Indeed, the Ju/’hoan have a concept that they call !kui g!oq; it deals with dangerous relations between people and carnivores and involves notions of ‘bad luck’. It is much discussed around campfires.48 Taking note of !kui g!oq and the other beliefs, we can begin to understand what Lucy Lloyd’s informant meant when he said that one of the supposed lions in Stow’s copy had a daughter and that the other ‘belonged to’ a group of human figures. In a long account of lions and some of their habits, //Kabbo said that ‘[t]hey talk, they also are people’, but ‘people who are different’.49 Like people, they have brothers, wives, daughters and sons: they live in family groups. The informant’s remark that the lion’s daughter is depicted is therefore understandable.

Moreover, leonine shamans can be associated with – ‘belong to’, in the informant’s phrase – groups of people. In the Kalahari today, people speak about malevolent leonine shamans who ‘belong to’ a distant camp coming to a trance dance to harm members of that group. In response, one or more of their own shamans enter trance so that they can fight off the marauders in the spirit realm. The next day, after the excitement of the dance has subsided, people gather to hear about spiritual experiences of this kind. They feel reassured that their shamans were able to protect them. At this time, the malevolent shamans who come during the night are explicitly said to belong to a distant, often only vaguely identified, group. As a result, the source of sickness and social discord is located outside the small, tightly knit band. Destructive friction that would be caused by identifying the source within the small social group is thus avoided. The informant’s suggestion that two groups of people are depicted in Plate 20, each with its own ‘lion’, fits in with these beliefs.

It is now clear that, overall, the informant was saying something that parallels the other San comments on rock paintings that we have discussed. Though he did not use the word, he interpreted the images in terms of what Lloyd called ‘sorcery’. No other interpretation makes sense of lions ‘belonging’ to groups of people and having relatives. Ironically, we know that the painter of the images had no such ideas in mind. He or she depicted eland, not lions, and it was probably the relationship between the human figures and eland as sources of potency that mattered to him or her. This conclusion fits well with other images in Stow’s copy on which the informant did not comment.

Other ‘things of sorcery’

In the top left corner of Plate 20 there are two figures with antelope heads and one that appears to have ears or short horns. As we pointed out in Chapter 2, transformation into antelope is a common feature of San religious beliefs and rock art.

Centre right are two figures with lines emanating from their armpits. One has an arm raised in a commonly painted gesture. Similar lines are associated with two lower figures and with one centre left. Patricia Vinnicombe argues that such lines probably do not represent decorative tassels made of leather thongs, as some researchers have thought, but rather perspiration.50 As she points out, perspiration was associated with supernatural potency; it could be good or bad. These contrasting manifestations of sweat potency are seen in two /Xam myths. In a tale about the Mantis and a troop of baboons, the trickster-deity ‘anointed the child’s eye with (the perspiration of) his armpits’ as part of a long process of healing’51 (original parenthesis). The bad aspect of sweat is seen in a myth of a female hyena who poisons ‘Bushman rice’ (termite eggs) with the ‘blackened perspiration of her armpits’ and gives it to the wife of the Dawn’s-Heart Star (Jupiter); it turns her into a lioness or lynx.52

Sweat played a prominent role in the San trance dance. As we saw in Chapter 2, Qing told Orpen that ‘the dancers put both hands under their armpits, and press their hands on’ the sick person.53 Among the /Xam, a sick or injured man was rubbed with sweat from a man’s armpit, sweat mixed with a protective medicinal plant.54 Richard Lee reports that the sweat worked up by a vigorous Ju/’hoan trance dance is the visible expression of potency on the body.55 He describes it as ‘a most important phenomenon in healing’: ‘Sweat is rubbed onto and into the body of the person being healed.’56 The potency is in the smell of the sweat. That is why a shaman in trance is rubbed with the sweat from another shaman’s armpits to protect him while his spirit is away on out-of-body travel.57 Further, Lorna Marshall suspected that people threw their legs over a shaman who has fallen in trance ‘to get sweat on to the man directly from the backs of their knees, a sweaty place’.58 Lines, generally shorter than those from a figure’s armpits, are sometimes painted at its knees. These lines, like the armpit lines, may represent sweat.

A dramatic lion panel

Occasionally, researchers find exceptionally complex panels of images that show us the experiential reality of transformation into a lion in unequivocal detail. These panels can be used to contextualize and illuminate less detailed groups of images. An effective test of any interpretation of rock art images is to see to what extent it dovetails with diverse details in a range of rock paintings. The more features of a panel of images that an explanation clarifies in terms of authentic San beliefs and practices, the more confidence we shall have in it. Repeated links between images and beliefs show that a connection is not accidental. It is to such a panel in the Eastern Cape Province that we now turn.

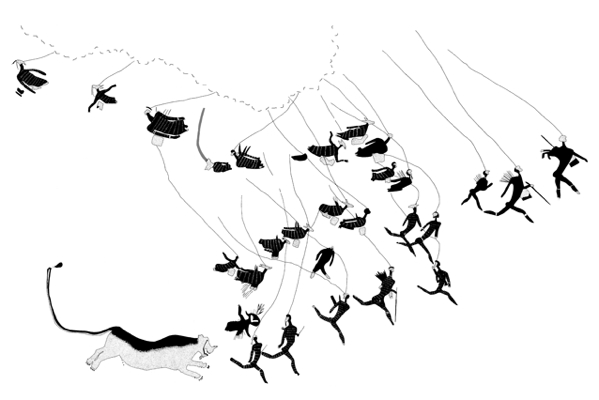

This panel shows a running lion with whiskers and teeth; it is pursuing ten human figures (Fig. 40). Any impression that this is a depiction of a real lion chasing real hunters in a real incident is soon dispelled. The whole scene is filled with indications as to the supernatural context of the event.59

Even at first glance, the unnaturally long feline tail suggests that we are not looking at a realistic depiction of a lion. But there is much more in the panel. Two of the fleeing figures bleed from the nose and are therefore clearly in trance.60 They look back over their shoulders at the lion. The long lines that emanate from the tops of their heads almost certainly represent their spirits leaving their bodies via what the San believe is a hole in the top of the head (Chapter 2).61 Trancers report a peculiar sensation in this part of the body: ‘When the top of your head and the inside of your neck go “za-za”, that is the arrival of num [potency].’62

40 A San rock painting showing a mystical lion pursuing 10 fleeing human figures, some of whom have hooves and bleed from the nose. Above them 16 figures appear to take to the air, their legs tucked beneath them in a kneeling posture. Some have antelope heads and some bleed from the nose. Lines probably depicting their spirits leaving from the tops of their heads lead to a hollow in the rock.

Above the fleeing human figures are 16 transformed figures that have been called ‘trance buck’ or ‘flying buck’. With antelope heads, they are part-human, part-antelope and depict a benign transformation of a shaman into an antelope coupled with the experience of flight in trance.63 Like the running human figures, they too have long lines leading from the tops of their heads. The lines lead to a hollow in the rock. At least three of these ‘trance buck’ bleed from the nose. Some are in the kneeling posture into which a trancing shaman often falls; others, more comprehensively transformed, have no legs. A number have their arms in the backward position that some shamans adopt when potency, as a Ju/’hoan man put it, ‘is going into your body, when you are asking god for power’.64 Both the fleeing men and the trance buck are hirsute and thus recall the growth of hair on a shaman in violent trance.65 On the far left an isolated figure, not shown in figure 40, bends forward in the posture that trancers assume when their potency boils painfully in their stomachs; a spirit line leaves from the top of its head. All these features indisputably situate the panel in the context of the trance dance and its mystical experiences.

The enigmatic rectangular forms at some of the figures’ chests may depict the small ‘medicine bags’ in which shamans carry various substances. These bags are often slung around the neck so that they hang down onto the chest. In addition to containing potency-imbued substances, bags have transformative powers. In a /Xam myth, /Kaggen transforms himself into a ‘flying thing’ (a praying mantis) by getting into a bag.66 Elsewhere he describes himself: ‘I shall have wings, I shall fly when I am green, I shall be a little green thing.’67 Getting into a leather bag was like ‘getting into an animal’ – like diving into a deep, dark pool of potency. The trance buck also have lines coming from their chests. It is possible that these lines depict sweat, but their position suggests that they more probably (or in addition) represent the tingling or pricking sensation that San shamans feel in the sternum and which they associate with the ‘boiling’ of their potency. A Ju/’hoan shaman explained: ‘Then your front spine and your back spine are pricked with these thorns.’68

Near and just above the head of the lion is a uniquely elaborated figure with outstretched arms and complex emanations from its head and chest. Its head is turned towards the viewer of the panel. Because it differs from all the other figures, and because of its position above the first of the fleeing figures, we suggest that it may represent a specific shaman who is attempting to control the charging feline and thus protect the people it is pursuing.

In summary, we can say that, in Figure 40, we have a vivid representation of a spiritual encounter between a lion that may have ‘belonged’ to one group of people and the terrified, fleeing shamans of another group. There is little doubt that the painter of this panel spelled out what more laconic painters implied by their depictions of solitary lions. As San shamans often say, the spirit realm can be a fearful place, not something with which ordinary people should meddle.

Rare depictions

Two groups of people, each associated with a lion, set the stage for the sort of supernatural conflict of which the /Xam San spoke and of which the Kalahari San still speak. However, the San seem to have been reluctant to make images of such threatening creatures.69 It is therefore not surprising that rock paintings of lions are comparatively rare. For example, Harald Pager found only 45 depictions of felines among the 12,762 images in his Drakensberg research area.70 Nevertheless, as Vinnicombe pointed out, such images are ‘consistently repeated’.71

The rock art with which Bleek and Lloyd’s informants were personally familiar consisted of the engravings on the central and more western parts of the interior of South Africa. Here, too, depictions of lions are rare.72 Generally though, rock engravings tend to be one or two images on a stone: ‘scenic groups’, though sometimes found, are uncommon. Yet some lion engravings are meticulous and, to our eyes, beautiful.

What would the engravings with which the /Xam informants have been familiar have looked like? At a site some 150 km (93 miles) to the east of the place where Diä!kwain lived there are engravings of grotesque creatures made by scraping the patina from the rock to leave a lighter colour image. Their tufted tails suggest that they depict lions. Often they have an exaggerated mouth that is wide open (Fig. 41). These images seem to emphasize the fearful killing and maiming ability of lions – their /hoken, or ‘dangerous darkness’. Whatever conclusion we come to, we should see these grotesque images, not from a Western perspective, but within the framework of San beliefs about lions. Perhaps they depict prowling leonine shamans, just the sort of creature that roars in the darkness beyond the firelight. If not the Devil himself, they probably represent a shaman who, ‘as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour’.

41 A San rock engraving of two mystical lions with large open jaws.

Why did the San depict lions?

What, then, can we say about the comparatively few paintings of felines that do exist? Vinnicombe summed up her discussion of depictions of felines in terms of general, one could say abstract, symbolism:

These records of Xam Bushman attitudes towards the larger carnivores suggest that lions and leopards were associated with harm as opposed to benefit, with disease as opposed to health, insecurity not security, malevolence rather than benevolence, with death as opposed to life. The essence symbolised by carnivores – the large biting animals – was the opposite of the essence symbolised by herbivores – the large non-biting animals. Antelope were regarded as a constructive force in Bushman symbolism. Lions and leopards were destructive.73

She was right in broad terms. The San do think of felines as negatively opposed to the positive taxon of herbivores.74 But we do not believe that they painted disembodied symbols of abstract concepts that floated contextless on the rock face. Rather, they placed their painted images in contexts that gave them a specificity and experiential reality. In coming to this conclusion, we need to distinguish between, on the one hand, the ‘philosophical’ system of San thought that we ourselves construct by inferring meanings and associations from a variety of statements given by San people, and, on the other hand, the actual social and cognitive contexts in which the San painted their images. But what was this context?

The act of painting was part of a complex, multi-stage ritual. For the San, the rock face was not a tabula rasa, a blank slate, on which ‘artists’ could paint whatever they wished.75 On the contrary, it was an ‘interface’ between this world and the spirit realm, and therefore a meaningful context that semantically ‘framed’ images placed on it.76 A painting of a lion, situated on this interface, may have triggered, in San viewers, associations of darkness, fear and the supernatural simply by being, in the first instance, a manifestation of a malevolent shaman, but the San themselves probably did not think of the image as a symbol consciously painted to convey such abstract qualities and states. Rather, they reified feelings of fear and impending doom (the Ju/’hoan concept of !kui g!oq) in material – concrete – images of malevolent, leonine shamans whom they had experienced in the spirit world. San manipulation of painted symbols was not so much abstract as experiential and specific.

But why did the San sometimes depict solitary lions in amongst other images? A clue may be found in what we already know about the relationship between San image-makers and their images. We know that San images were more than ‘pictures’: they were powerful things in themselves, objects that influenced people’s beliefs and behaviour. Some depictions of eland, for instance, were reservoirs of potency to which dancing shamans could turn when they felt that they needed more potency.77 In this way, images continued to function long after they were made.

Something similar, though in some sense in reverse, may have existed between image-makers and their depictions of lions.78 Taking into account San beliefs about the very nature of images and the transitional rock face on which they were placed, we argue that the act of depicting a lion gave the image-maker some control over what the image depicted – that is, over a malevolent shaman who, if not confronted and defeated, would cause havoc in the painter’s band. The image reified otherwise abstract and, for ordinary people, benevolent shamans’ rather nebulous visionary experiences of conflicts with malevolent leonine shamans in the spirit realm.

Depictions of lions thus achieved two complementary things. First, because everyone knew that painted and engraved images were more than simple pictures, those of lions confirmed the existence of dangerous leonine shamans; they materialized otherwise vague threats. Second, though at the same time, the images reassured people of the image-maker’s control over malevolent shamans: the image-makers had, after all, made the images and thereby ‘nailed down’ the leonine spirit beings that endangered their community. In doing so, the image-makers, who were probably in many cases themselves shamans, entrenched their respected position in the community as protectors against supernatural influences; image-making and subsequent engagement with images was embedded in the social matrix and had social consequences.79

‘Formlings’ and the spirit realm

We have left until last the most puzzling feature of Stow’s copy (Plate 20), the one that he thought depicted shields used in lion hunts. Can some truth be hidden in his error?

Today, the overall shape and packed nature of Stow’s scutiforms will remind most southern African rock art researchers of a class of images known as ‘formlings’. This word is a hybrid English-German neologism that the German explorer and ethnographer Leo Frobenius concocted in the 1930s to denote a type of rock art image that is common in Zimbabwe80 but that is also found, though less frequently, in the northern parts of South Africa,81 and occasionally elsewhere as well.82 The word itself is neutral: it means little more than ‘shapes’. Broadly described, formlings are cigar-shaped ovals, often with lighter-coloured caps, that may be found individually but that are more often stacked together in groups ranging from 2 to more than 20.

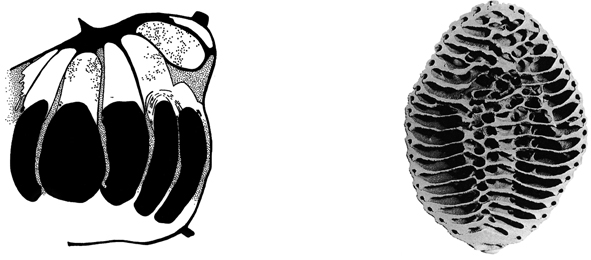

42a ‘Formlings’ painted in Zimbabwe. and 42b A section of a termite mound from which the ‘formling’ images may derive.

By and large, there have been two approaches to finding out what formlings mean. One way is to see them as grain bins,83 stockaded villages,84 quivers, mats, xylophones,85 beehives86 and clouds.87 Another perspective is to accept them as pure, abstract symbols. Peter Garlake, for instance, argues that formlings symbolize the gebesi, the general area between the diaphragm and the waist that painfully contracts when a San shaman enters trance.88

More recently, archaeologist Siyakha Mguni has convincingly argued that at least some formlings in Zimbabwe depict the internal structure of termite mounds and, in some instances, the mounds’ relationship with entities in the environment, such as trees (Figs 42a, 42b). Termites were an important source of nutrition for the San, and their nests were probably seen as the foci of potency;89 some of the features of termite nests, he suggests, are exaggerated in accordance with San beliefs about supernatural potency.

Can the same be said of the Eastern Cape images that Stow copied? Termites were certainly a valued food.90 The Bleek and Lloyd Collection tells how the /Xam dug ‘Bushman rice’ (termite larvae) out of the ground:91 ‘They eat the flying ants, when the ant’s rain has fallen.’92 Termite chrysalises were a nutritious food for the /Xam San. But they were also implicated in supernatural events. Lloyd learned that the /kitten-/kitten, a little black bird, ‘bewitches the ants’ chrysalides, when it feels summer is there, and they fly out’.93 The chrysalises were not simply a prosaic food: they were supernaturally controlled. Depictions of termite mounds may therefore have pointed to openings into the nether realm over which shamans had control. In the piles of earth raised by these insects we see the nether world breaking through into the realm of daily life. As the rock paintings themselves proclaim, the sphere of the spirits was never far away.

While we acknowledge that some formlings in Zimbabwe probably represent termite mounds, we have come to another conclusion, one that takes us back to an older idea and one that Mguni also suggested: at least some may depict honeycombs. Figure 43 shows a set of honeycombs in a vertical crack in the rock face of a shelter about 12 km (7.45 miles) from the site of the painting in question. The stacked nature of the combs and their oval shapes certainly recall the painted scutiforms in Plate 20. The dots painted on the scutiforms may represent either bees themselves or the cells that are clearly visible in Figure 43. Numerous comparable paintings in the Drakensberg have been persuasively interpreted as honeycombs.94

43 Natural honeycombs occur in stacks in the cracks of rock faces. The individual cells and the bees themselves can be seen here.

Bees and honey were important to the San throughout southern Africa in interrelated ways. The Cape San called /Kaggen’s wife the ‘Dassie’ (hyrax, rock rabbit), a small mammal that lives in cliffs95 where bees have their hives, while among the Ju/’hoansi the wife of the principal deity, though not a dassie (there are few cliffs and consequently few dassies in the Kalahari Desert), is said to be the ‘Mother of the Bees’.96 This association seems to have been widespread. Wilhelm Bleek noticed that, in Orpen’s transcription, the name of Cagn’s wife was Coti. This name he thought ‘may be identical’ with the first syllable of /Huntu!katt!katten (Orpen’s initial ‘C’ being the dental click, /), which means a dassie, but he cautiously added that ‘this is not certain’.97

The Cape San used a bull-roarer (!goin !goin) to cause the bees to swarm and leave their hives so that people could collect honey in safety.98 The San bull-roarer was a flat piece of wood some 32 cm (12.5 in) long and 3 cm (1.18 in) wide that was attached to a length of string about 40 cm (15.7 in) long and thereby to a stick that could be used to twirl the flat wood and produce a roaring sound.99 In one account, the people are said to ‘beat the goin !goin’.100 The word that Lloyd translated as ‘beat’ is !kauken; in addition to the obvious meaning, it was used to mean to tremble as a man’s spirit leaves his body in trance.101 In the /Xam text, the men took the honey home to the hungry women and a dance ensued: the women clapped, while the men danced. The dance lasted through the night until dawn.

There is no explicit reference to this being a trance dance (as we have pointed out, no /Xam word meaning ‘trance’ was recorded), but a part of the narrative suggests that the /Xam were performing a trance dance after eating honey. The informant who spoke about the bull-roarer described a significant moment: ‘Therefore, the sun shines upon the backs of their heads.’ In an added note he explained: ‘The men are those, on the backs of whose heads the sun shines’, and Lloyd explained: ‘literally, the holes above the nape of their neck’.102 What did the informant mean? The Kalahari Ju/’hoansi consider dawn to be an especially potent time in a trance dance that lasted all night. Lorna Marshall saw what happens at this transitional time: ‘Always at dawn comes a high moment, and sunrise is often the highest of all. As the sun rises, the people sing the Sun song. They feel that the n/um is very strong then.’103 The Ju/’hoansi call the area at the back of the neck the n//au: it is the spot from which their shamans expel sickness that they have drawn out of people.104 We have found nothing in the Bleek and Lloyd collection to suggest that the /Xam expelled sickness through this spot, but it was clearly important to them – the parallel with the Ju/’hoansi is striking.105

44 A group of men dance along a ‘thread of light’ while bees swarm above them. On the right one of the dancers bleeds from the nose and bends forward towards a strange creature that holds decorated dancing sticks. Colours: shades of red, white.

In the Kalahari today, honey is believed to have much potency, and the Ju/’hoansi have a medicine dance named ‘Honey’.106 Moreover, they like to dance when the bees are swarming – not, of course, actually in a swarm (Fig. 44). They believe that the bees are messengers of the Great God.107 Writing about trance dances, Marshall says that when a man dances the Giraffe Dance he ‘becomes giraffe’; the same is true of the Honey Dance: he ‘becomes honey … Bees and honey both have n/um.’108 Like other ‘strong’ things, honey transforms people.

For the /Xam, honey was also a creative substance. /Kaggen used it in his creation of the first eland: ‘The Mantis put the honey in the water; he called the Eland, it was a big Eland. Then the Eland came leaping out of the reeds…. The Eland came up and stood; the Mantis moistened its hair and smoothed it with the honey-water.’109

The discovery of oval, stacked honeycombs near the site on which Stow based his copy (Pl. 20), and the rich beliefs about bees, potency and the trance dance, seem to us highly significant. Further, the position of the combs in a crack in the rock face may have suggested to the San an interconnection between this world and the spirit realm behind the rock face. It is therefore significant that just next to some of the scutiforms there is a marked crack and angle in the rock. Out of this opening to the underworld emerges a rearing serpent with strange tusks (Fig. 37). Another discovery at this site throws light on this serpent.

Music and transition

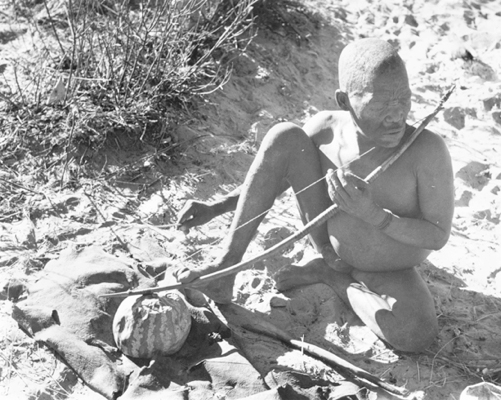

As one of us (SC) was working on this panel, he found, hidden among the faded images, at least seven men playing musical bows; four of them are shown in Figure 37. Still today, the San rest one end of a bow on their shoulder and then tap the string with a stick – as the figures in the paintings are doing. The lower end of the bow is placed on a resonator, usually a gourd or melon (Fig. 45). Among the /Xam, /Han≠kasso told of /Kãunu, a rain-maker who was able to call up the rain by striking his bow string: ‘he sat and took up the bow, while we were asleep … we heard the bow-string as he was striking it there’. He was a ‘real medicine man’ with great power: ‘the clouds came up … it rained there, poured down until the sun set’.110 The tusked serpent emerging from a crack in the rock face is therefore probably a rain-snake (Chapter 5) summoned by the bow players, who were, in turn, empowered by the potency of honey. In a comparable painting, a bow player seems to summon a bulky, spotted rain-animal from an angle in the rock (Fig. 49).

45 A Kalahari San man playing a musical bow. He rests the lower end of the bow on a melon to act as a resonator.

There is in Plate 21 a remarkable coming together of San beliefs and rituals – all of which Stow missed. Although there are neither lions nor shields depicted, we have nevertheless learned a great deal about San beliefs concerning lions and shamans. We also find that potency is represented by painted honeycombs and that shamans play musical bows to activate potency and call up the rain-snake. The permeability of the rock face is implied by the honeycombs that lodge in clefts and by the emerging serpent. All in all, the panel is a portal to a spiritual dimension. Yet it was built up over time, probably by a series of painters. Each participated in the panel and developed ideas implicit in the work of his or her predecessors. Carefully deciphered, this panel gives us a good idea of how San rock art ‘works’ – very differently from traditional Western art. But there are still unfathomed depths of meaning.

As we see in the following two chapters, honey and bees play a role in San mythology. We therefore ask: does San mythology hold any clues that can help us to decipher the meanings of the art? In answering this often-asked question, we are led to an understanding of how the San perceived the landscapes in which they lived. Again, an important truth is brought home to us: San thought, religious experience and ritual formed a closely interrelated network.