CHAPTER 7

The Imagistic Web of Myth

And Qwanciqutshaa killed an eland and purified himself and his wife.1

Modestly, Joseph Millerd Orpen entitled his 1874 article ‘A glimpse into the mythology of the Maluti Bushmen’. It is much more than a glimpse. Without his pioneering work we would know nothing about the mythology of the San people who made the rock paintings of the south-eastern mountains, some of which we discussed in previous chapters. His article is an astonishingly rich source for all students of mythology, whether they work in southern Africa or elsewhere. Its global importance was recognized early on, and it was reprinted in the journal Folklore in 1919. In more recent times, Orpen’s article has become foundational for southern African rock art researchers, but the myths that it contains have received little independent attention.

Orpen found that recording San mythology was a frustrating task. What he was hearing seemed muddled and fragmentary. Perhaps because he was familiar with the myths of ancient Greece and Rome, tales that have a beginning, a middle and an end, as well as a purpose, be it moral or explanatory, he expected something more coherent and more intelligible. Then, too, the biblical mythology with which he was familiar suggested specific types of narrative myth. Perhaps with Genesis in mind, Orpen seems to have been especially interested in creation myths. But, overall, he ascribed the apparent confusion that he encountered in part to the use of several interpreters. He also thought that Qing, the young San man who was his guide, did not know the tales properly: ‘Qing is a young man, and the stories seem in part imperfect, perhaps owing to his not having learnt them well.’2

A more persuasive reason why Qing did not know certain things became evident when Orpen asked what he thought was a straightforward, specifically mythological question concerning origins and creation: ‘Where did Coti [Cagn’s wife] come from?’ Qing replied that he did not know ‘secrets that are not spoken of’. These ‘secrets’, he said, were known by only ‘the initiated men of that dance’.3 He himself was not an ‘initiated man’ of that dance.

The rest of Orpen’s article shows that the dance of which Qing spoke was the shamans’ trance dance in which, as the young San man himself put it, ‘some become as if made and sick’ and ‘blood runs from the noses of others whose charms are weak’.4 In Chapter 2 we explained how people were ‘initiated’ into this dance. It was not by an ‘initiation ceremony’, such as many societies hold to mark entry into adulthood. Rather, novices repeatedly danced behind an experienced, older shaman, thus learning by protracted participation how to dance themselves into an altered state of consciousness and thereby visit the spirit realm.

Was Qing correct in thinking that San shamans had the answers to mythological questions such as the creation of Coti? We are inclined to think that many shamans were not as well informed as Qing supposed them to be. The point is that Qing believed shamans to have insights into the origin of mythological beings. He, and no doubt others, thought that shamans possessed knowledge about spirit beings because they frequently visited the realm in which those beings lived. Knowledge obtained via these experiences did not constitute a canon of ‘secrets’ jealously guarded by shamans, such as one associates with ‘secret societies’ in other cultures. As we have seen, San shamans speak freely about what they experience in the spirit realm. The so-called ‘secrets’ were merely matters about which people did not bother to think. That is probably what Qing meant by ‘secrets that are not spoken of’.

Orpen missed this link between mythology and the knowledge that shamans acquired by means of the dance and their trans-cosmological journeys – as have many researchers up to the present day who think of mythology as an autonomous component of San thought and belief. Yet the dance is an essential part of our understanding of San thought: indeed, Qing stated explicitly that it was San shamans who held the key to fundamental aspects of San mythology. How can we turn that key?

The surface and the depths of myths

Since the time when Orpen was writing in the 1870s, folklorists, psychologists, historians of religion, literary scholars and social anthropologists have done an immense amount of work on world mythology. Names like Claude Lévi-Strauss and Joseph Campbell immediately spring to mind. They and many others have asked fundamental questions: What is a myth? Do myths differ from, perhaps simpler, folk tales? How can we extract the ‘meaning’ of a myth from its narrative? In any event, in what sense can a myth be said to have ‘a meaning’? Why do groups of people identify themselves by their allegiance to certain myths and reject the myths of other communities and religions? In what circumstances do people recount myths? Are at least some myths closely related to rituals?

In answer to these questions, two fundamental, though not exclusive, approaches to myth have emerged. One is to see the narrative of a myth as paramount.5 This meta-linguistic approach leans heavily towards aetiological tales (e.g., how certain landscape features came about) and also towards the dramatization of moral precepts (breaches of moral codes lead to punishment). The other approach to myth plays down narrative and emphasizes internal features and the structures of the tales. The structuralist position is that, within the mythology of a community, there are fundamental elements, or building blocks, and it is the essence (their inner, often hidden, meaning) of these repeated building blocks and the ways in which they relate to one another that create the real power behind the narrative.6 Building blocks may include, among others, symbolic items of material culture, mental and corporeal experiences, repeated movements through the landscape, or, in strict structuralist terms, binary oppositions, such as day/night and life/death, and their multiple permutations. Once the narrative is seen as of comparatively minor importance, it becomes clear that individual narrators in pre-literate societies, like that of the San, can arrange and elaborate episodes and key building blocks according to what they think is appropriate at any given time.7 Always, whatever approach we pursue, myth can be understood only in its own cultural setting, no matter what cross-cultural parallels we may be able to detect.

Without in any way diminishing the importance of narrative, it is principally the ‘building-block’ approach to San myths that we take up in this chapter. But we do not follow a strict structuralist approach.8 The building blocks that we identify are not binary oppositions. Rather, they are ‘happenings’ that derive from San trance experiences. These ‘happenings’ give a flavour to narratives and obliquely refer to the status of shamans in San society: they cannot be said to ‘structure’ the narratives in a Lévi-Straussian sense.

At the outset, we need to emphasize that what we have to say does not apply to all San tales. Some scholars distinguish between folk tales and myths, though they acknowledge that the distinction is often hard to draw. It is easy to declare the tale of Little Red Riding Hood to be a folk tale and the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt to be a sacred narrative, but there are often in-between tales that seem to have a bit of both categories. Acknowledging that there are no hard-and-fast definitions, we take narratives that involve origins and transformations to be myths. These transformations include, for instance, people turning into spirit beings, animals changing into other animals, people turning into animals and vice versa, and transformations effected by the movement of people or animals from one cosmological plane to another. These are the narratives that we discuss. But it is not always easy for people from another culture to detect evidence for transformation. As a result, researchers have sometimes discarded narratives as simple cautionary tales for children when, in fact, they are constructed on a foundation that implies, rather than explicitly describes, transformations.

In this chapter we do not attempt to analyse a single San myth in great detail.9 Instead we explore a relationship that is implied by the three registers of our Rosetta Stone (see Preface and Fig. 1). We begin this task by highlighting some aspects of painted panels of rock art images. We then show that principles detectable in those panels help us to uncover parallels between San rock paintings and what we argue are the imagistic, rather than narrative, patterns of myths.10 The anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse uses ‘imagistic’ to denote religions that do not have written scriptures;11 accepting that meaning, we extend its use to cover the deployment of an open-ended set of images in religious experience, myth and art.

Spiritual panoramas

Westerners who confront complex panels of San rock art images, some of which stretch for some metres, do not know where to start looking (see Pls 5, 21). How can they decipher them? Should they start at the left and move towards the right? Or should they do it the other way around? Can the panels be seen as comic-strips? Soon they conclude that a panel of many images does not have a beginning and an end in that sense. Frustrated, they then seek to break the panel up into clusters of images that seem to have been made by one painter at a single time and that appear, possibly by the actions performed by human figures, to constitute a unit – so-called ‘activity groups’.12 Homing in on these units, some of which appear to be narrative whereas others are less easy to categorize, modern viewers isolate images that they think were made by different painters and so miss intentional interrelationships between earlier paintings and those that were added by subsequent painters. In the end, researchers lose sight of the whole panel and what its entirety may have meant to San people.

The first thing to realize is that large, complex panels of rock paintings were cumulatively constructed over many years. They were not planned with a ‘completed’ form in mind. Rather, they were open-ended and invited the participation of generations of independent painters. Many panels are in their present state not because the painters considered them complete, but, more tragically, because the traditional San way of life in the region came to a catastrophic end. Consequently, we need to study the ways in which painters added to panels and related their contributions to already-existing images. This is an ongoing line of research.13 This simple and really rather obvious point already begins to undermine an exclusively narrative approach to rock art panels, the approach that sees them as conglomerations of petty narratives of daily life with a light seasoning of ‘mythology’.

One feature of San rock art panels that especially moves from narrative to essence needs to be emphasized when we approach the relationship between rock paintings and mythology. We mentioned it in Chapter 2, and called it synecdoche – a part stands for a whole.14 We can now introduce a new distinction. ‘Fragments of the dance’ (Chapter 2) are of two kinds: those that can be seen by anybody at a dance and those that cannot be seen by everyone. In speaking of the first kind we may use the word ‘realistic’, as we would when referring to a painting of, say, a dance rattle that minutely shows the individual cocoons or antelope ears from which its segments were made. Realistic fragments of the dance include:

– people bleeding from the nose

– people bending forward at the waist

– people with their arms held in a backward or outward position

– women clapping

– a fly whisk

– dance rattles

The other kind of ‘fragment of the dance’ comprises conceptual entities, things that can be ‘seen’ only by shamans in trance. They include:

– the ‘threads of light’ to which we return in the next chapter

– lines from the top of the head that depict the spirit leaving the body

– transformations of people into animals

– entry into the spirit realm through holes in the ground or the rock face

All these painted fragments of the dance probably operated on at least three levels: First, they implied the significance of the whole dance. It was through the trance dance that people were healed and society was protected from malign influences. Second, the fragments drew attention to key moments in shamans’ spiritual journeys from this world to the spirit realm. As the Kalahari San still say, the ‘breakthrough’ into the spirit realm is terrifying but also immensely beneficial for the community. Third, by their very nature, each fragment focused on an individual. The dance was certainly a communal ritual, but, notwithstanding the combined activity of a community, it is the individual shaman who achieves breakthrough into the spirit realm. Each time an individual danced and entered the spirit world, it was a new, valued and specific instance of one person’s journey. As Megan Biesele writes, ‘Ju/’hoansi themselves treat these experiences as unique messages from the beyond, accessible in no other way save through trance, and they regard narratives of the experiences as documents valuable to share.’15 Similarly, in rock art panels individual revelations are embedded in the commonwealth of knowledge. A particular kind of relationship between certain individuals and their communities is thus implied by San rock art.

Often panels that at first glance appear to be assemblages of beautiful depictions of animals turn out to be peppered with fragments of the dance. Even within a single activity group, one may find, say, six men walking in a line. Only one of them bleeds from the nose, but that figure clearly implicates the others in the religious activity of reaching out to the spirit realm. At the level of the whole panel, such figures implicate those around them. The same is true of the dance itself. Biesele found that ‘all who come to the dance experience an uplifting energy which they feel to be a necessary part of their lives’.16

Then we must recall that the rock face is a contextualizing ‘veil’ between this world and the spirit realm: sometimes, as we saw in Chapters 4 and 5, images appear to issue forth from (or enter into) the spirit world through steps and cracks in the rock on which they are painted.17 Fragments of the dance thus combine with the liminal nature of the rock face on which they were painted to unite the whole panel in a mosaic of spiritual experiences. In some ways, San rock art panels are like stained-glass windows in medieval cathedrals: the ‘light’ from the spiritual domain shines through them and animates them so that they become manifestations of spiritual things rather than mere ‘pictures’. Both San paintings and ecclesiastical stained glass induce enveloping mental states of awe, fear and comfort.

How do these thoughts about painted panels and mythology help us to approach specific San myths?

The San cosmos

Everything that the San did, thought and experienced, be it what we would (not altogether appropriately) call secular or sacred, happened within a specific cosmological framework. Herein lies the key to understanding both San myth and art. Once we understand the levels that made up the totality of the San cosmos, the nature of the movements from place to place that occur in myths and the ways in which the images are painted on the rock combine to make overall sense.

Clues to the structure of the 19th-century San cosmos are scattered throughout the texts that Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd collected and those that Orpen obtained from Qing.18 These beliefs persist among San groups in the present-day Kalahari. We now outline the San cosmos and then move on to see how an appreciation of the levels of that cosmos help us to understand otherwise obscure myths.

Briefly, the San recognized three cosmological levels. In the middle was the level on which they lived their daily lives, hunted animals and gathered plant foods. Above was a level of spiritual things. Here were god and other spirit beings, all of whom lived alongside god’s vast herds of animals. As Qing put it when Orpen asked him where Cagn was, ‘Where he is, elands are in droves like cattle.’19 Below the level of daily life was a subterranean spiritual realm, accessible by means of holes in the ground and waterholes. Here, under water, dwelt the rain-animal and other spirit beings.

This summary may be misleading because it implies more rigidity in San cosmology than the people themselves would have recognized. Again, we must distinguish between the rather philosophical ‘systems’ that we construct from a collection of indigenous statements and the less formalized, day-to-day thinking of people. The San spirit realms overflowed into the level of daily life, and shamans had the ability to travel with some frequency between the three levels. An out-of-body journey, beginning on the level of daily life, could proceed by entering a hole in the ground or a waterhole and then, after subterranean travel, rise up to the realm above. The three levels thus interacted, and the fundamental San religious experience was movement between cosmological levels.

The purposes for these journeys were multiple. Some shamans went to the spirit realm to plead for the sick; others fought off malevolent shamans who tried to infect people with sickness; others sought information about the location of animals; still others were more concerned with capturing a subaquatic rain-animal in the lowest level and then leading it through the sky so that its blood and milk could fall as rain. But shamans were not the only people who could experience the spirit realms. Ordinary people could address god and ask for blessings of food. They could also encounter spirit beings, such as shamans in the form of lions (Chapter 6). Everyone was continuously aware of the proximity of spiritual things.

!Khwa, girls and frogs

As we pointed out in Chapter 1, it is significant that San informants seldom referred directly to myths when they commented on copies of rock paintings. The art cannot be said to be in any general, overall sense illustrative of mythology. More frequently, the images reminded informants of ‘sorcery’, the ‘things and deeds of sorcery’ and rain-making. There were, however, two occasions when the San commentators seem to have referred to a tale of people being transformed into frogs. It was recorded in a number of versions. Lucy Lloyd entitled one of these ‘The girl’s story; the frogs’ story’.20

Before considering this tale, we need to note that the site at which Stow claimed one of the relevant paintings (Fig. 46) existed has not been relocated. Dorothea Bleek ‘hunted in some of the many kloofs [Dutch for ‘narrow valleys’] and under several waterfalls’ when, in the late 1920s, she was preparing Stow’s copies for publication, but she was unsuccessful. Subsequent researchers and our own efforts have fared no better, but one of us (SC) did find a collapsed rock shelter next to a waterfall on the farm that Stow mentions as being the location of the paintings. Perhaps the lost images are now buried under the fallen rock. Nevertheless, some researchers privately express doubts as to the authenticity of Stow’s copy, and we are inclined to agree that reservations may well be in order. For one thing, paintings of frogs are extremely rare, and, for another, the putative frog images in Stow’s copy are stylistically unusual. Still, the myth to which the 19th-century informant referred interests us in its own right because of the elements it combines.

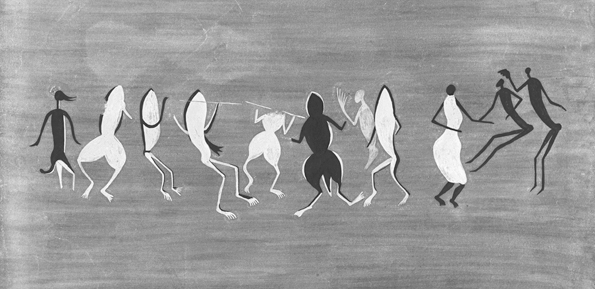

46 George Stow’s copy of a San rock painting that purports to depict a line of frogs. It reminded a /Xam informant of a tale in which the rain turned people into frogs because a girl at puberty had misbehaved. Colours: white, black, dark red.

Two of Bleek and Lloyd’s informants commented on Stow’s Plate 45 (see Fig. 46). We do not have a phonetic transcription of the comments of either, only Lloyd’s summary and her interpolated remarks. One of the informants said:

The water is destroying these people, changing them into frogs, because a girl had been eating touken, a ground food.

The second informant said:

They become frogs. The girl whose fault it is in the brown dress (the sixth figure from the right), the Rain being angry with her. The third said to be her father, fourth her mother. The figure to the extreme left was hunting and is blown by the wind into the water.

We give our own brief summary of the myth to which Dorothea Bleek believed the informants were referring. In dramatized performance and as transcribed by Lloyd it was much longer:

A girl who was ill lay in a hut. The other people went out to seek chrysalides [Chapter 6]. A young child remained at home and observed what happened. The ill girl went to the waterhole and killed a Water-child. As a result, !khwa turned her and the other people as well into frogs. !Khwa was as large as a bull, and his children were the size of calves.21

This is the kind of San tale that appears trivial if the significances of its elements are unknown to the modern reader. It could easily be dismissed as a simple folk tale seemingly featuring the ‘watermeide’ that we encountered in Chapter 4. Indeed, for the informants who cited the narrative in response to Stow’s copy, it seems to have been taken as a cautionary tale for young girls to behave themselves. But we need to dig deeper. As fragments of the dance are scattered through panels of rock art images, so too are certain pivotal concepts – building blocks – scattered through myths. They give the whole myth significance and coherence, and, moreover, link myths one to another conceptually rather than narratively. We therefore need to know something about San understandings of the ill girl, waterholes and frogs.

As in some comparable /Xam accounts of rituals, the girl is at puberty (what, in Lloyd’s translation, the /Xam called ‘a new maiden’) and is consequently secluded in a hut.22 At this time of life, she possess supernatural powers. Diä!kwain explained that if a ‘new maiden’ curses a man, the rain will strike him dead with lightning: ‘For, she when she is a maiden, she has the rain’s magic power [!khwa ka /ko:öde].’ Here, as in some other tales, !khwa is personified and must be treated with respect. Girls ambivalently poised at puberty can command the supernatural potency of the rain.

The transformation into frogs takes place at a waterhole. The narrator spoke of ‘descending’ into a ‘spring’. As we have seen, the /Xam word !khwa was used to mean both water and rain: !khwa wells up in waterholes and falls from the sky. It will be recalled that shamans of the rain claimed to dive into waterholes to capture a !khwa-ka xoro, a rain-animal (Chapter 5). Both water and waterholes are mediators between levels of the San cosmos, between material and spiritual realms. As such, they are powerful places of transformation.23

The third element is frogs. They, too, are mediators between levels of the cosmos: they live in water and on dry land.24 Qing gave a comparable explanation of the tailed figures shown in one of Orpen’s copies (Fig. 33). He said that they ‘live mostly under water; they tame elands and snakes’.25 That they ‘live mostly under water’ implies that they are amphibious. The concept of amphibiousness intrigued some painters, and they expressed it by depicting creatures that could live both on land and under water. There is, for instance, a single (as far as we know) painting of a pair of crabs (Fig. 47).26 One may suppose that it is the quirky sport of an imaginative painter, but crabs’ associations of transition between land and water are implied by the close juxtaposition of depictions of leather bags (not shown in Figure 47). As we saw in Chapter 6, getting into a bag was, for the /Xam, a mode of transformation and transition. The painting goes further in that it shows that the smaller of the two crabs lacks pincers. Why? Crabs are territorial and may attack other crabs if they trespass on their territory. In such fights, a vanquished crab may lose its pincers (in time, they will grow again). If the amphibious crabs are shamans who have passed through the transformation of water, they probably represent a battle in the spiritual (subaquatic) realm, such as shamans often report.27

47 The theme of being under water as a way of conveying the sensations of altered states of consciousness is uniquely expressed in a painting of two crabs in what may be a pool of water. The small crab has lost its pincers, probably in combat with the larger one. Colour: black.

Another painting shows antelope-headed figures rising from a deep crack in the rock (one bleeds from the nose): around them are not only fish and eels, underwater creatures, but also what we take to be amphibious turtles (Fig. 48).28 /Han≠kasso told Lloyd that both the tortoise and the ‘water tortoise’ were ‘things that the rain puts aside as its meat. Therefore Bushmen fear them greatly.’29 Seen in the context of other paintings of amphibious creatures, the line of frogs in Figure 46 implies hazardous transition between realms, the foundation of the myth to which the informant referred.

48: Figures, one of whom bleeds from the nose, rise up out of a deep cleft in the rock that has been smeared with black paint. The large figure has an antelope head. The under-water theme is expressed by the presence of fish, eels and turtles. A cluster of about 12 fly whisks point to the trance dance. Colours: shades of red, black, white.

The point we make here is that, though this tale of frogs may seem trivial as a narrative, its elements are rich in cosmological and ‘sorcery’ connotations. Still, we doubt that the tale was indeed the subject of the rock painting in Figure 46 and that the images were merely illustrative of it. It seems more likely to us that the significance of the paintings for those who made and viewed them lay in the rarely depicted frog-like creatures. The principal subject of the painting, if it can be said to have one, is the cosmological mediation that frogs imply. And, as we have seen in previous chapters, transition is a concept that suffuses San rock art.

Honey and transition

The way in which cosmological levels were projected onto the specific natural environment in which a community of San people lived is more clearly evident in two myths that Qing related to Orpen.30 Neither appears in our other 19th-century source, the Bleek and Lloyd Collection. Although they come from markedly different climatic and physical environments some 600 km (373 miles) apart, there are nevertheless notable parallels between the collections.31 Exactly what constitutes those parallels is, we argue, what we are now discussing: the ‘building blocks’ of the San cosmos and trans-cosmological travel.

The first of the two myths that we examine features Cogaz, who, in Orpen’s collection, was Cagn’s elder son:

Cagn found an eagle getting honey from a precipice, and said, ‘My friend, give me some too;’ and it said ‘Wait a bit,’ and it took a comb and put it down, and went back and took more, and told Cagn to take the rest, and he climbed up and licked what remained on the rock, and when he tried to come down he found he could not. Presently, he thought of his charms, and took some from his belt, and caused them to go to Cogaz to ask advice; and Cogaz sent word back by means of the charms that he was to make water to run down the rock, and he would find himself able to come down: he did so, and when he got down, he descended into the ground and came up again, and he did this three times, and the third time he came up near the eagle, in the form of a large bull eland; and the eagle said, ‘What a big eland,’ and went to kill it, and it threw an assegai, which passed it on the right side, and then another, which missed it, to the left, and a third, which passed between its legs, and the eagle trampled on it, and immediately hail fell and stunned the eagle, and Cagn killed it, and took some of the honey home to Cogaz, and told him he had killed the eagle which had acted treacherously to him, and Cogaz said ‘You will get harm some day by all these fightings.’32

If we adopt the narrative approach to this myth, we can perhaps say that it is a cautionary tale: it is unwise to try to take other people’s honey. Indeed, it ends with Cogaz’s admonition: ‘You will get harm some day by all these fightings.’ But, if we look beneath the narrative surface, we find the levels of the San cosmos, a desire for potency, and the supernatural abilities of shamans who possess ‘charms’ and who can control the rain. This, we argue, is the real impact of the tale, however subliminal: the myth is an affirmation of the tiered cosmos and the powers of shamans to transcend it in their endeavours to maintain social harmony and the health of the community.

In broad terms, then, the tale concerns honey and trans-cosmological travel, together with a mixture of reality and supernatural events. But there are also mythical equivalents to the ‘fragments of the dance’ that are scattered through painted panels. To decipher the myth we need to look beneath the narrative surface to these less obvious elements.

We begin by noting that honey was not only a valued food for the San, their gods and the spirits of the dead:33 it also appears in numerous myths from all San groups, not just the /Xam and Maloti people. Along with fat, another greatly desired food, the Ju/’hoan San of the Kalahari Desert consider honey anomalous because it can be both eaten and drunk. As the 19th-century /Xam man //Kabbo put it, ‘They will eat the honey’s liquid fat.’34 The idioms ‘to eat fat’ and ‘to eat honey’ can mean to have sexual intercourse; they also refer to the collaborative interaction of men and women in the trance dance.35 Importantly, honey has much potency and is the name of one of the Ju/’hoan medicine songs that are sung at trance dances. As Lorna Marshall put it: ‘These dances are named for these things because the things are vital, life-and-death things and they are strong, as the curing medicine in the music is strong.’36 As we have seen, when a man dances the Giraffe Dance he ‘becomes giraffe’; the same is true of the Honey Dance: he ‘becomes honey’.37 One Ju/’hoan shaman, /Gao, told how he received his Honey Song: ‘It was daytime, and he was awake when //Gãuwa appeared to him and bid him follow to a tree that had a beehive in it. //Gãuwa pushed /Gao in the hole in the tree where the baby bees and the honey were. Bees and honey both have n/um.’38

Even as a man may possess honey potency, so too may he own a beehive and mark it as his property. Anyone who stole another man’s honey ran the risk of being killed.39 Stow reported that the San of the south-eastern mountains owned hives that were lodged in the cliffs; these hives could be inherited.40 To reach them, the San hammered wooden pegs into the rock to act as footholds.41 People returned to their hives seasonally each year.42 In the more open, treeless /Xam San country, the people exploited underground hives; honey may also be found in old termite mounds that bees have taken over.43 In a /Xam myth, /Kaggen digs out honey for the little springbok.44 As we saw in Chapter 6, these underground honey hives were closed by a large stone,45 as were the locust holes that shamans controlled.

In the Drakensberg there are rock paintings of people apparently climbing ladders to hives from which swarms of bees emerge.46 As we saw in the previous chapter, there are also paintings that show the nested catenary curve form that honeycombs assume in the wild; many such images have minutely painted bees.47 Why would the San have painted honeycombs? A probable answer is that honey and the activity of obtaining it was, like hunting eland, indicative of the acquisition of potency. Confirmation of this suggestion comes from paintings that show hives and bees explicitly associated with dancing shamans, a number of whom bleed from the nose and wear dancing rattles (Fig. 44). The close association between bees, honey, potency and trance dancing is indisputable.

The background to the myth is now becoming plainer. The surface narrative is that the eagle probably owned a hive high on a cliff, and Cagn tried to obtain some of his honey. But honey also represents potency: Cagn, himself a shaman, tried to obtain the eagle’s potency. The theme of combat between shamans is taken up in other myths and rock paintings. But, as often happens in /Xam myths, Cagn was tricked and, in this instance, left hanging on the rock face. Eventually, after using his ‘charms’ (probably buchu), he was able to climb down by means of water. It is not clear whether ‘to make water’ means to urinate or simply to wet the rock. Either way, water is, as we saw in Chapter 4, a mediator between cosmological levels.

Passing between cosmological levels is still more clearly evident in what followed. Cagn ‘descended into the ground and came up again, and he did this three times’. This is a common form of San (and other) shamanic travel. For instance, Kxao Giraffe, an old Ju/’hoan shaman, told how his ‘protector’, the giraffe, told him that he would enter the earth: ‘That I would travel far through the earth and then emerge at another place.’ Then he rose to the upper level of the cosmos: ‘When we emerged, we began to climb the thread – it was the thread of the sky.’48 Prior to that, water had facilitated his underground travel: ‘We travelled until we came to a wide body of water. It was a river. He took me to the river. The two halves of the river lay to either side of us, one to the left and one to the right.’49 In that manner, Kxao Giraffe reached the place where the spirits were dancing. There he learned how to trance dance.

When Cagn emerged from his third passage underground, he transformed himself into a large bull eland, the most potent and the fattest of all animals. Then, in an episode that recalls a /Xam myth about a fight that /Kaggen had with the meerkats (his affines) who had killed his eland and acquired its potency,50 Cagn is able, by the potency of the eland, to deflect the eagle’s assegais (spears). Finally, !khwa again comes to Cagn’s rescue, and hail (Chapter 5) kills the eagle.

Eland and precipices

In another of Qing’s myths we encounter a similar cosmological structure along with some highly evocative imagery.51 It concerns Qwanciqutshaa, a mythical ‘chief [who] used to live alone’, who had ‘great power’ and through whom Cagn ‘gave orders’:52

And Qwanciqutshaa killed an eland and purified himself and his wife, and told her to grind canna-, and she did so, and he sprinkled it on the ground, and all the elands that had died became alive again, and some came in with assegais sticking in them, which had been stuck by these people who had wanted to kill him. And he took out the assegais, a whole bundle, and they remained in his place; and it was a place enclosed with hills and precipices, and there was one pass, and it was constantly filled with a freezingly cold mist, so that none could pass through it, and those men all remained outside, and they ate sticks at last, and died of hunger. But his brother (or her brother), in chasing an eland he had wounded, pursued it closely through that mist, and Qwanciqutshaa saw the elands running about, frightened at that wounded eland and the assegai that was sticking in it, and he came out and saw his brother, and he said, ‘Oh! my brother, I have been injured; you see now where I am.’ And the next morning he killed an eland for his brother, and he told him to go back and call his mother and his friends, and he did so, and when they came they told him how the other people had died of hunger outside; and they stayed with him, and the place smelt of meat.

At the heart of this myth is the death of eland, a pivotal San image in both myth and rock art. Like Cagn, Qwanciqutshaa himself had a herd of eland.53 They were a kind of alarm system for him: when he saw them running wildly about, he knew that trouble was brewing. These mystical herds were all concentrations of potency in the upper level of the tiered San cosmos.

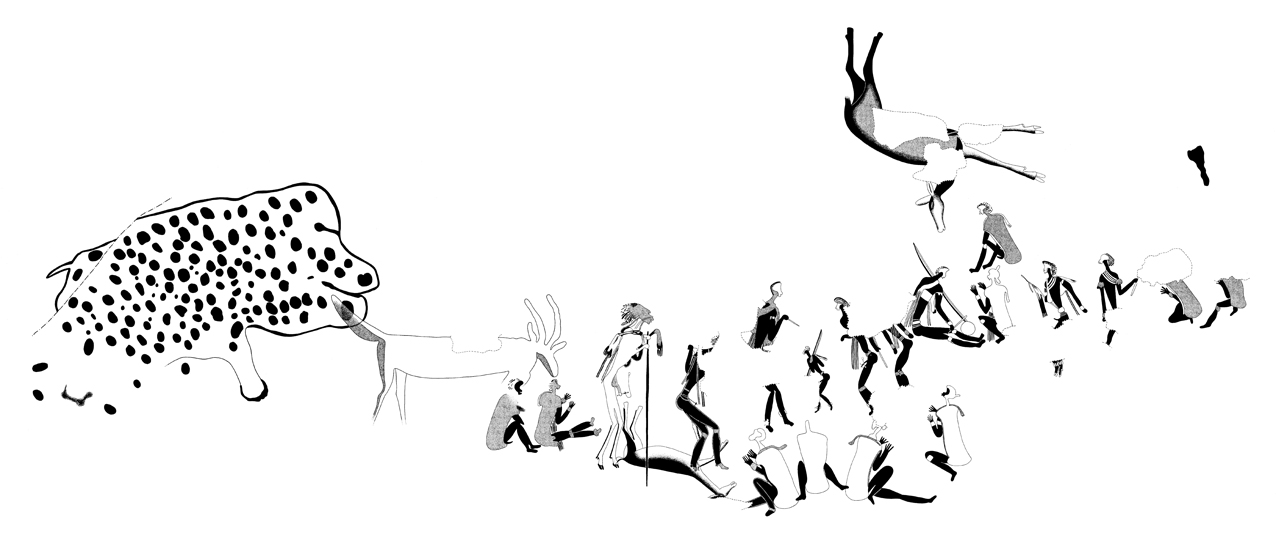

49 A large spotted rain-animal emerges from a step in the rock. A man plays a musical bow, while others dance and clap. A dead eland above is probably the source of the potency they are activating. Colours: shades of red, white, black.

Redolent with connotations, the myth links the registers of our Rosetta Stone and opens up a way into the complexity of San thought patterns. Neither San myth nor art can be deciphered without an appreciation of the dying eland’s unifying role: it is at the centre of the web of San thought, ritual and rock art.54

The eland was /Kaggen’s favourite creature, though the trickster-deity is not mentioned in this story. A series of /Xam myths tells how he created the eland in a waterhole, an opening between the levels of San cosmology, and fed it on honey, that cherished food imbued with potency. As the eland grew in size, he anointed its flanks with honey and water.55 To /Kaggen’s great distress, the eland was killed: ‘Then he wept; tears fell from his eyes, because he did not see the Eland.’56 Diä!kwain explained /Kaggen’s continuing affection for the eland:

The Mantis does not love us, if we kill an Eland … the Hartebeest was the one whom he made after the death of his Eland. That is why he did not love the Eland and the Hartebeest a little, he loved them dearly, for he made his heart of the Eland and the Hartebeest.57

Understandably, /Kaggen was constantly with the eland. The /Xam said that he sat ‘between the Eland’s horns’ and, by various ruses, tried to trick hunters so that the eland could escape from them.58

The eland was and still is believed to have more potency than any other animal. Understandably, the Ju/’hoan San like to perform a trance dance next to the carcass of an eland so that they can harness its released potency (Fig. 49). As they pull back the skin of a dead eland, a sweet odour arises: it is taken to be evidence of the eland’s potency. Here we have an explanation of Qing’s opening statement: ‘And Qwanciqutshaa killed an eland and purified himself and his wife.’ Those who killed an eland ran the risk of offending Cagn and had to observe certain customs to avoid the suffering that could follow. Para-doxically, the killing of an eland was a transgression and also a prelude to the ‘purification’ that was subsequently needed.

In San thought, ‘purification’ is an inappropriate word. This is another translation problem. What Qing meant was that Qwanciqutshaa performed a trance dance and, during it, he was able to combat any evil influences that may have come upon him and his household as a result of the killing. The role of the trance dance in what Orpen called ‘purification’ is clear: during the dance, all the people present are ‘cured’ by the laying on of hands. The shamans draw sickness from them and then cast it back into the darkness from which it came; they also travel to Cagn and plead for the sick. It was thus through a trance dance that Cagn’s anger could be assuaged and people could be ‘purified’. The ambivalence of an eland kill lies in the death of a highly potent animal and then the using of its potency to protect the killer.

The first killing of an eland in the myth about Qwanciqutshaa was followed by ‘purification’. The second had a similar sequel. Qwanciqutshaa’s brother wounded, apparently mortally, an eland, which then frightened Qwanciqutshaa’s eland herd. Moreover, Qwanciqutshaa himself claimed to be ‘injured’. The next day he killed an eland ‘for his brother’ so that his brother could be ‘purified’ by the dance that would follow. The second killing ends with evocative words: ‘and they stayed with him, and the place smelt of meat.’ The brother and his family moved up through the freezing mist, known to the San as ‘the rain’s breath’,59 to transcend the tiered cosmos and participate in what Orpen thought of as an act of ‘purification’.

Three points are of interest here. First, the wounding of the eland facilitated access to the upper reaches beyond the mist (Qwanciqutshaa ‘pursued it closely through the mist’) and, by implication, simultaneously angered Cagn (‘The Mantis does not love us, if we kill an Eland’). Second, a result of the brother’s killing the eland and Qwanciqutshaa’s subsequent ‘purification’ was that ‘his mother and his friends’ stayed with Qwanciqutshaa. When the San kill a large animal, such as an eland, people gather from scattered camps to share the abundance of meat and to enjoy the relaxed social relations and healing dance that ensue. Third, smell is, in San thought, a vehicle for potency: if ‘the place smelt of meat’, it was filled with protective eland potency that can deflect assegais and arrows of sickness (Chapter 2) and protect people from sickness. The other people who had to remain outside, and were thus not able to participate in the dance, ‘died of hunger’.

A performance of the whole myth was probably much enjoyed by those listening. The San are not solemn about their mythology: still today, there is much dramatization, interruption and hilarity. But on such occasions there is also more than entertainment. A performance of the Qwanciqutshaa myth subtly reinforced the status of shamans as key figures in the nexus of eland, dancing, the banishment of sickness and movement between levels of the cosmos.60 Each performance of the myth, even if there are variations in the narrative, reinforced fundamental cosmological and religious beliefs.

‘There’s magic in the web of it’

Myth and art come together in a striking way in numerous rock shelters hidden in secluded kloofs, or as Qing put it, ‘enclosed by hills and precipices’. In these shelters, painted panels often contain abundant images of eland – old bulls, cows, foals and yearlings, sometimes painted one on top of another (Pls 5, 25). Why did the San keep on painting eland after eland? In addition to being reservoirs of potency, the ever-growing painted herds may have created an ambience in which it was easy to sense the presence of Cagn. As Qing said, ‘Where he is, elands are in droves like cattle.’61 People could turn to the paintings for spiritual sustenance and reassurance.

Although eland feature in San myths, it is now clear that San rock paintings did not ‘illustrate’ myths in the way that pictures illustrate a child’s book. Nor is there any evidence that that ‘mythology’ can be put forward as anything but a superficial and vague explanation for the complexity of San rock art. Once we break away from the restricting fetters of a narrative approach to mythology, we can begin to enquire about the significance of the repetitive elements in so many tales. Immediately, we find ourselves in the realm of cosmology and the ‘sorcery’ that transcends cosmological levels and thereby brings not only social viability but also personal happiness to human communities. If we can speak of fragments of the dance, we can also speak of ‘myth elements’ or ‘building blocks’, pregnant nuggets of significance that, in many but not all San myths, together provide a foundation on which narratives may be variously deployed.

While material fragments of the dance repeatedly crop up in San myths (for example, people bleed from the nose), it is the conceptual ones that most subtly give the narrative its deeper significance (for example, people entering holes in the ground or passing through a barrier of mist). Both rock art and myths are thus tightly woven webs of reality and purely conceptual elements. Both straddle the divide between the material world and the spirit realm. Both wrestle with and try to clarify elusive relationships between these two supposed spheres of existence and the emotions that they elicit in people.

In the next chapter, we discuss the cosmological mise en scène of Qing’s myths. We also show that elements of the process of reconciling conceptual and material worlds can be seen in the beliefs of other cultures.