CHAPTER 1

Back in Time

Before the cattle were unyoked, we saw a female figure emerge from a hole in the face of the cliff bearing what we at first thought to be a sick child but on a nearer approach proved to be a diminutive and emaciated old woman, the mother of her dutiful and, to do her no more than justice, affectionate bearer …

Accompanying her to a low cave formed by an enormous block of stone with a flattened undersurface now blackened by smoke and soot, we found two men of something between the Bushman and Hottentot tribes, one in an old felt hat and sheepskin cloak, smoking tobacco out of the shankbone of a sheep, the other in a red coat, lying outstretched upon his back and fast asleep, with an old musket, marked G R Tower, carefully covered beside him. A few thorn bushes served to narrow the entrance of the cave and partially to screen its inmates from the weather …

A few animals, nearly obliterated, were still visible upon the walls of their dwelling, proving it to have been an ancient habitation of their race; and the men told me they had seen drawings of the unicorn but had never known any one who could testify to the existence of the living animal.1

In this extract from his diary, the British artist and explorer Thomas Baines describes the appalling conditions in which many San people lived at the middle of the 19th century. He had sailed to the Cape of Good Hope in 1842 and, after working in Cape Town as a coach painter, embarked on an extensive journey through the interior of the subcontinent. On this journey, he compiled what is today an invaluable collection of paintings that depict not only scenery but also indigenous people. In 1858 he accompanied David Livingstone along the Zambezi river, where he was one of the first Westerners to see the Victoria Falls.

The encounter that Baines describes took place near the present-day town of Aliwal North (Fig. 2). The San whom he met and painted were bereft of the land and animals that had sustained them for millennia (Pl. 2). They drifted from place to place, clinging to what little they could derive from the Western civilization that had engulfed them. Next to the man whom he found sleeping in the rock shelter lay a musket engraved with the name of its former owner; traded tobacco provided the other man with some solace. The San, together with the pastoral Khoekhoe (formerly known as Hottentots), who had for the most part lost their herds and flocks, were caught between two ways of life.

On the rock wall behind the people were the remains of San paintings. Though blackened by smoke and soot, the few remaining images pointed to a rich cultural heritage – but Baines himself was unimpressed by them. He thought the artists were ‘ignorant of perspective’ and in ‘want of skill’.2 The poverty of the San in material things tended to persuade early travellers that they were equally poor in culture and belief, and therefore unworthy of respect.

Nevertheless, Baines did not consider the San whom he met to be poverty-stricken simply because they were, by tradition, nomadic hunter-gatherers. True, mobile people cannot carry much in the way of goods on their long treks. There was more to it, however. The 19th-century San were the victims of two centuries of harassment and dispersal. We read that the young woman in the group had no option but to carry her frail mother on her back. She had no extended family to help her. Even her daughter had been ‘detained in servitude’ by a group of people known as Bergenaars – mountain robbers, as Baines explained. The whole San social system had broken down.

2 Map of southern Africa showing places mentioned in the text. The San groups indicated speak, or spoke, mutually unintelligible languages.

The Bergenaars, a mixed-race group, lived very largely through banditry and stock theft, as did many other culturally and racially heterogeneous groups throughout southern Africa, and indeed the people whom Baines himself met.3 The remnant communities of San had no recourse but to steal cattle and sheep. They therefore joined creolized groups like the Bergenaars and defended their land with their traditional bows and arrows and with newly acquired muskets. Early on, they became feared for their lethal poisoned arrows and their cunning cattle rustling.

This state of affairs gave the colonists the excuse they sought to eradicate the hunters. In the 1770s, the Swedish naturalist and traveller Anders Sparrman wrote: ‘Does a colonist at any time get view of a Boshiesman [as the San were then known], he takes fire immediately, and spirits up his horse and dogs in order to hunt him with more keenness and fury than he would a wolf or any other wild beast.’4 No quarter, no negotiation. Another Swedish naturalist, Carl Peter Thunberg, writing at the end of the 18th century, was appalled by the treatment that the San received at the hands of the colonists. One commando raised to exterminate the Sneeuberg San ‘killed 400 Boschiesmen; of this party seven had been wounded by arrows, but none died’.5

Those who were taken alive by the colonists were no better off. Louis Anthing, who was commissioned in the 1860s by the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope to investigate the atrocities that were being committed, was shocked by what he found:

Those who went into the service of the new comers did not find their condition thereby improved. Harsh treatment, and insufficient allowance of food, and continued injuries inflicted on their kinsmen are alleged as having driven them back into the bush, from whence hunger again led them to invade the flocks and herds of the intruders, regardless of the consequences, and resigning themselves, as they say, to the thought of being shot in preference to death and starvation.6

Some British colonists (Britain having finally taken full control of the Cape in 1814) tried to blame the Dutch farmers for this state of affairs, but the missionary John Phillip found otherwise:

While England boasts of her humanity, and represents the Dutch as brutes and monsters, for their conduct towards the Hottentots and Bushmen, a narrow inspection … will bring to light a system … perhaps exceeding in cruelty anything recorded in the facts you have collected, respecting the atrocities committed under the Dutch Government.7

Materially poor, culturally rich

The San were an autochthonous people. As archaeological evidence testifies, they and their ancestors lived for many millennia throughout the whole of the subcontinent.8 Then, about 2,000 years ago, they had to contend with an influx of other peoples.9 First, there were Khoekhoe herders in the western, central and coastal regions and, later, Bantu-speaking black farmers along the east coast and the highveld of the interior. Then a more comprehensive threat came in 1652, when the Dutch established a settlement at the Cape of Good Hope. Domestic herds and their colonial owners soon spread into the interior of southern Africa. Thereafter, the San survived in the shrinking interstices of land between the more populous and resource-hungry agricultural economies. In the semi-arid parts of the central interior and in the mountains in the south-east, the San managed to sustain viable communities into the 19th century. By turns, these communities had both good and bad relations with the peoples moving into the subcontinent.

Many settlers, especially missionaries, believed that the San did not have the mental capacity to understand any form of religion. Nevertheless, some colonists did take the trouble to enquire into San beliefs. One of these was Sir James Edward Alexander. A Scottish soldier and traveller, a man of independent financial means, he journeyed up the western side of what are now South Africa and Namibia hoping ‘to discover some of the secrets of the great and mysterious continent of Africa’.10 In particular, he hoped ‘to promote trade, to civilize the native tribes that might be visited, and to extend a knowledge of our holy religion’ (ibid.). He began his long trek in 1835, a time when the colonists entertained a very low opinion of the ‘Boschmans’, as the San were then known.

Alexander, however, discovered that the San were not entirely without religious concepts, albeit very rudimentary ones:

During the journey I had often endeavoured to find out traces of religion among the Boschmans and others; but I had hitherto been very unsuccessful…. [A]mong the Boschmans I had discovered nothing to indicate the faintest trace of religion, but now I did in a singular way…. ’Numeep, the Boschman guide, came to me labouring under an attack of dysentery.

I asked him what had occasioned the disease; and he said it was from having dug for water at the place called Kuisip … without having first made an offering … to Toosip, the old man of the water.

‘Do you say any thing to him when you put down your offering at the water-place?’

‘We say, “Oh! Great father! Son of a Boschman – give me food; give me the flesh of the rhinoceros, of the gemsbok, of the wild horse [zebra or quagga], or what I require to have.”’

I was very glad he had been ill; for owing to this, I found out a trace of worship among a very wild people.11

That Alexander hardly understood this ‘trace of worship’ is today clear. But he at least saw beyond the people’s material poverty. Little by little and very slowly, the view that the San were irredeemably ‘primitive’ began to break down in more educated colonial circles, though not in rural districts.

Today, numerous San linguistic groups still live in the Kalahari Desert, where their ancestors lived for thousands of years. They include the Ju/’hoansi (formerly !Kung), /Gwi, !Kõ, and Nharo. These present-day San are not descendants of people who were recently driven into the desert by other people. They are descended from the aboriginal human populations of the African subcontinent.12 They have become one of the most thoroughly studied of the world’s small-scale, hunter-gatherer societies.13

By comparing the beliefs and rituals of these desert people with what was recorded for the groups, like the /Xam, that lived farther to the south in the 19th century, we are able to see that, notwithstanding regional variations, certain beliefs and rituals were widespread, probably pan-San. These commonalities included complex hunting observances, girls’ puberty rites and the central, all-important healing, or trance, dance.14 Where basic parallels are demonstrable, it is therefore possible to supplement the 19th-century southern ethnographic record by recourse to more recent research in the Kalahari.

Comparisons of this kind highlight the large number of mutually unintelligible San languages.15 When four young Ju/’hoan boys from the northern Kalahari were brought to Cape Town in 1879, it was found that their language was unintelligible to the southern /Xam San people.16 Many San languages have unfortunately died out in comparatively recent times. One of these, the /Xam language, was chosen for the new, post-apartheid South African national motto: !Ke e: /xarra //ke – People who are different come together.17

In the 19th century, a gradual (though unfortunately still incomplete) reassessment of the San was initiated by a small group of people whose work provides the foundation for our investigation of what the San themselves said and thought about the paintings they made in their rock shelters. This group comprised the Bleek family, Joseph Orpen and George Stow.

A remarkable family

Today the history of the Bleek family is well known. Indeed, a scholarly industry has grown up around its various members.18 Wilhelm Bleek (1827–1875) was a German philologist, who came to southern Africa in 1855 to compile a Zulu grammar. While he was working on the Zulu language in the British colony of Natal he heard about the San. He wrote: ‘During the first few months of this year [1856] the Bushmen descended from their impregnable hiding places in the Kahlamba mountains [Drakensberg] to steal cattle again.’19 After a brief but linguistically productive sojourn in Natal, Bleek moved to Cape Town in 1856 to become a court interpreter and, later, curator of the valuable library owned by the British governor, Sir George Grey.

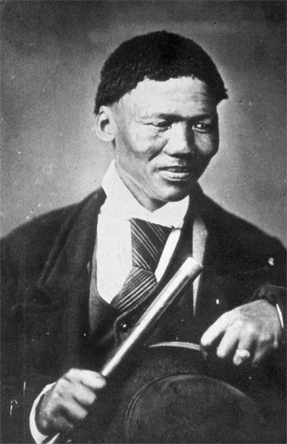

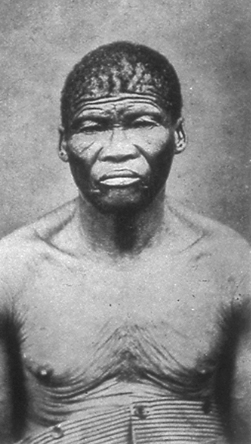

Bleek’s life took a momentous turn soon after he moved to the Cape. He learned that some San men, convicted of sheep-stealing and even murder, had been taken to a jail in Cape Town. He saw this as an opportunity to study their little-known language. He realized that Zulu and other Bantu languages were not in any danger, but that the San languages, quite different from those Bantu languages, were threatened with extinction as a result of the frontier conditions we have described. Eventually, Bleek persuaded Sir George Grey’s successor, Sir Philip Wodehouse, to allow some of the San convicts who spoke the /Xam language to live with him in his suburban house. There were six major /Xam informants – ‘teachers’ would be a better word – from the central Cape and, later, four young boys from the Kalahari Desert. The names of the /Xam informants will crop up in subsequent chapters: /A!kunta, //Kabbo, /Han≠kasso, ≠Kasin, !Kweiten-ta-//ken and Diä!kwain (Figs 3a, 3b). The symbols indicating clicks are explained in the introductory Note on Pronunciation.

Wilhelm Bleek was joined by his sister-in-law Lucy Lloyd (1834–1914). Although she had no formal training, she proved to be a talented linguist. While Bleek concentrated principally on working out /Xam grammar, Lloyd took down statements in phonetic script and prepared parallel English transliterations. All in all, Bleek and Lloyd compiled over 12,000 manuscript pages of personal histories, word lists, myths, and accounts of rituals – an astonishing compendium of information (Fig. 6). (The references that we give to the notebooks should be understood as follows: the initial B or L indicates whether the notebook was compiled by Bleek or Lloyd. The first numerals are the numbers that Bleek and Lloyd assigned to the informants; the next numeral is the number of the notebook; the final numeral is the page number, the notebook pages being numbered consecutively through the whole series.)

3a /Xam San people whom the Bleek family interviewed in the 1870s: Diä!kwain.

3b /Xam San people whom the Bleek family interviewed in the 1870s: //Kabbo.

3c /Xam San people whom the Bleek family interviewed in the 1870s: a group of /Xam prisoners at the Cape Town Breakwater Jail.

Neither Bleek nor Lloyd was able to visit San people in their homeland. The colonial frontier conditions and Bleek’s commitments in Cape Town did not allow for what would in any case have been a long and hazardous journey. There were therefore many aspects of /Xam daily life they were not able to observe. Nor were they able to see any rock paintings first-hand in the rock shelters where they were painted or engravings on open rock surfaces near waterholes. They had to depend entirely on copies made by other people.

After Bleek died in 1875, Lloyd continued with the work, eventually publishing Specimens of Bushman Folklore in 1911. It made public only small parts of the manuscript notebooks. By that time, Bleek’s daughter Dorothea (1873–1948) had become involved in the work, and after Lloyd’s death in 1914 she continued to publish sections of the vast manuscript collection. Dorothea died in 1948, bringing to an end one of the world’s greatest ethnographic enterprises. Today the entire collection has been electronically scanned and is available to researchers worldwide.20

Joseph Millerd Orpen

The Bleek family’s research received a considerable boost in 1874. In that year Joseph Millerd Orpen (1828–1923), a British representative in the Eastern Cape, sent a package to the editor of the Cape Monthly Magazine in Cape Town. He had co-led an expedition into southern Lesotho in an unsuccessful attempt to capture the renegade chief of the Hlubi, a sub-section of the Zulu nation. This man, Langalibalele (his name means Scorching Sun), had escaped over the Drakensberg escarpment into a maze of valleys and ranges that constitute the Maloti mountains of present-day Lesotho.

Orpen’s package contained what became a key document in our understanding of the southern San belief system.21 It told how he had met a young San man by the name of Qing, and how this man became his guide to a number of painted rock shelters, some 600 km (370 miles) to the east of where the Bleek family’s informants lived.22 Orpen also sent the editor copies that he had made of four rock paintings on which Qing had given fascinating if somewhat enigmatic comments (Pl. 14).

The editor sent the copies and, a few days later, the text of Orpen’s article to Bleek, who, in turn, showed them to his /Xam informants. Immediately, new vistas opened up. Bleek was able to compare his informants’ remarks with those that Orpen had recorded. He found that certain mythological figures were present in the tales of both regions, though the myths differed.23

A prominent part of the unity discernible between the /Xam collection and Qing’s myths is the presence of the San trickster-deity. ‘Cagn’ is Orpen’s Bantu-language transcription of the name that the Bleek family gave as ‘/Kaggen’. In his ‘Remarks’ on Orpen’s article Bleek wrote that Cagn ‘is not only the same as the chief mythological personage in the mythology of the Bushmen living in the Bushmanland of the Western Province, but his name has evidently the same pronunciation’.24 Depending on the orthography used, the dental click can be given as a ‘c’ or as a solidus (/). We retain the two spellings of the name to distinguish between the being’s appearances in Bleek’s and Orpen’s collections.

George William Stow

Another key figure in the study of San thought and rock art was also in contact with the Bleek family. He was George William Stow (1822–1882).

Stow came to South Africa from England in 1843 and eventually became a self-taught but respected geologist. He was well known in colonial intellectual circles. In the 1860s and 1870s, he developed an interest in the San and made many copies of rock paintings and engravings in what is now the region encompassed by the eastern Free State and the Eastern Cape provinces of South Africa. A large section of his book The Native Races of South Africa25 is devoted to the San and, at the time of his death, he claimed he was collecting copies of rock paintings to include in a ‘history of the manners and customs of the Bushmen, as depicted by themselves’.26

Bleek’s first glimpse of Orpen’s copies made him long to see ‘that splendid collection of Bushman paintings which Mr. C. G. Stowe [sic] is said to have made’.27 Bleek’s wish was soon fulfilled, and a portion of Stow’s collection arrived in Cape Town – sadly, just before Bleek died in 1875. After Stow’s death in 1882, Lucy Lloyd purchased the entire collection from his widow. Continuing the work of her brother-in-law, she sought San comments on a number of Stow’s copies.

Lloyd also obtained the manuscript of Stow’s The Native Races of South Africa. She invited George McCall Theal, the Keeper of the Archives of the Cape Colony and Colonial Historiographer, to edit the huge manuscript. She also selected and prepared a number of Stow’s copies of rock paintings and engravings for inclusion in the book. Theal remarked that ‘they are reproduced by chromolithography, so that they are indistinguishable from the originals, except that most of them have been reduced in size’.28 He could not have known that subsequent developments in printing techniques would, in the 21st century, lead to more accurate reproductions of Stow’s copies (see Pls 16–18, 20; see Figs 7, 12, 17, 21, 46).29 Much edited, Stow’s book was published in 1905.

In the late 1920s Dorothea Bleek was faced with a dilemma. Lloyd had died in 1914, but the entire collection of Stow’s copies of rock paintings had remained in the Bleek family unseen, except by specially privileged visitors to their home in Cape Town. Understandably, Dorothea was anxious to publish the rest of Stow’s collection. Before doing so, she tried to track down the original paintings in the rock shelters where Stow had copied them over 60 years earlier, as have others since then.30 For the most part she was successful in finding the sites, but others still remain lost. Once in the sites, Dorothea discovered that Stow had, in most instances, done a certain amount of re-arranging of the images to suit the size and rectangular shape of the paper on which he was reproducing them. She noted some of his interventions in her commentary on the plates in what became one of the great monuments of southern African rock art research: Rock Paintings in South Africa: from Parts of the Eastern Province and Orange Free State, Copied by George William Stow, with an Introduction and Descriptive Notes by Dorothea F. Bleek.31

Unfortunately, Stow’s contribution to our understanding of San rock art has been misconstrued and has indeed become misleading. At the root of the problem is the failure of later rock art researchers to distinguish between the copies that he made, his comments on them and the further comments that Bleek and Lloyd elicited from their 19th-century /Xam San informants. In addition to rearranging images, Stow also omitted what we now know are highly significant paintings and deliberately or accidentally falsified other images to suit his preconceived ideas about the original narrative purpose of the art. Writers have used Stow’s copies on the false assumption that they are accurate and that his comments on them derived from personal contact with San people.32 In fact, he had next to no direct contact with indigenous interpretations of the paintings. By his own account, he thought that the art was a ‘history’ of the San people ‘written’ by themselves. In at least one instance he completely forged a copy to provide an illustration of a hunting practice that he believed the San must have depicted somewhere – if only he could find it. It purports to depict a man disguised as an ostrich; he appears to be hunting a flock of those birds. Stow inexplicably faked what is his most influential copy and thereby precipitated a modern-day cause célèbre that ranks alongside other infamous archaeological frauds.33

Knowing the problems posed by Stow’s copies, one is tempted simply to ignore them. Researchers are, however, tied to them, because it was on these copies that the Bleek family obtained indispensable comments by San people. This is why we considered it essential to find the rock shelters whenever possible and to compare Stow’s copies with the original paintings. Then, having checked Stow’s copies in the actual rock shelters, we began to decipher what the informants said and to compare Bleek and Lloyd’s transliterations with the /Xam San words that the informants used. This is how the three registers of our ‘Rosetta Stone’ are interconnected: taken together, they lead us into the thought world of the San.

Three registers

1: THE ART

Southern African rock art is more varied than this book may at first suggest. This is because we concentrate on San comments on San rock paintings and ignore other rock art traditions. The incoming Khoekhoe herders and the Bantu-speaking farmers also made their own rock art, though their sites are neither as prolific nor as widespread as those of the San.34 Some researchers have investigated interaction between the San and other peoples and the ways in which this interaction may be reflected in the art.35

San paintings are found on the walls of open rock shelters (Pl. 4; Fig. 4). They are principally concentrated in the mountainous rim of the interior plateau: the Cederberg in the west and the Drakensberg and Maloti ranges in the east (Fig. 2). Fewer images, generally of a less fine kind, occur in the interior. As we shall see, the images found in the mountains comprise what we may (tendentiously) call ‘realistic’ images of animals and human beings, as well as a rich repertoire of more mysterious images. Often the human figures seem to be performing recognizable activities, such as walking in a line and dancing, and this has led researchers to follow Stow and mistakenly to consider the paintings a narrative of daily life.36 This is one of the misconceptions that our decipherments of San comments on the art challenge.

It is difficult to date the paintings. We do, however, know that in certain parts of southern Africa they were being made up to the end of the 19th century. At the other end of the time scale, the oldest date that we have for images comes from southern Namibia: excavated pieces of stone with painted representational images were dated to 27,000 years BP.37 More recent work based on AMS radiocarbon dating techniques has shown that depictions of eland antelope in the Drakensberg were being made about 2,900 years ago.38 The images that we discuss in this book belong to this more recent period, that is, from about 3,000 years ago to the end of the 19th century.

4 A Drakensberg rock shelter in which the San painted many images. The peaks in the background reach 10,000 ft (3,000 m).

The paintings were made with naturally occurring ochres, the colours of which could be altered by heating. Ochre and other pigments were mixed with various media that sometimes included animal blood and fat (Chapter 8). The paint was applied with a brush made from antelope hairs, or in some cases, with a finger. Much of the art is amazingly fine: many images are exquisite cameos. The head of an antelope, for instance, may be no larger than a single joint of a finger, yet the eye, mouth and ears are meticulously depicted (Pls 8–11; Fig. 5).

Apart from the paintings, there is also engraved San rock art – ‘petroglyphs’, as these images are sometimes known. They were either scored or pecked through the outer patina of rocks to leave a lighter-coloured image. Engraved rocks are found principally in the interior of the subcontinent.39 They are scattered on low hilltops. We refer to them briefly in Chapter 3; later we consider the role they seem to have played in rain-making (Chapters 4 and 6). Quite different engravings depicting the settlement layouts of Bantu-speaking agriculturalists have also been found. They occur in the eastern parts of South Africa.40

In our Preface we acknowledged the doubtful use of ‘prehistoric’ to describe the statements of 19th-century San informants but nevertheless suggested that the art took us back into indisputably prehistoric times. Questions that now arise are: Did the meanings of specific categories of images change over time? How far back can we project 19th-century indigenous interpretations? In answer to these difficult questions, we can say that even though we can detect regional and stylistic differences, and changes in religious emphasis through time, the core religious ceremony – the healing, or trance, dance – is always present. Painted stones found in southern Cape and Drakensberg excavations and dated to around 2,000 years ago bear images of diagnostic dance postures that suggest the trance dance still observable in the Kalahari.41 We discuss this dance in Chapter 2. Some of the dance images are indistinguishable from paintings on the walls of open rock shelters that have been dated stylistically to the last few hundred years.42 The anthropologist Alan Barnard has written, ‘As with all Bushmen, the medicine dance is the central rite of their religious practice.’43 We suspect that, although there were temporal and regional variations in emphasis within the San rock art tradition,44 the geographically widespread nature of the principal San ritual (the trance dance) and the dated southern Cape stones point to the high antiquity of the main San beliefs and rituals.

5 A fine example of a painted eland head. The artist has shown the mouth, nose, eye, tuft of red hair on the forehead and other details. The head, including horns, is approximately 10 cm (3.9 in) long. Colours: see Plate 9.

Contemplating the new, and often significantly more accurate, copies that we and others45 have been able to make of the paintings that Stow copied, we wonder whether the Bleek family’s San commentators would have said anything different if they had seen the originals in the rock shelters. On the other hand, do some of the striking images that they never saw because Stow omitted them actually confirm their interpretations? Generally, though not in every instance, we have found that it is now possible to construct more detailed explanations than those that the 19th-century San offered. These advances have been possible because researchers have been able to expand their knowledge of San thought exponentially since the middle of the 20th century by consulting the present-day Kalahari San and by detailed analysis of the Bleek and Lloyd Collection.

All in all, the detailed ‘fit’ between the art and what 19th-century San people said about the images and, moreover, their beliefs in general, demonstrate beyond reasonable doubt the relevance of those indigenous explanations to the rock art. Indeed, parallels between the 19th-century explanations and the painted images recall the complementarity between the registers of the Rosetta Stone.

2: SAN TEXTS

The 19th-century San texts that we decipher are key to our enquiry into the thinking of the San rock painters, but they pose many problems, more than we can discuss fully here. Questions arise concerning the informants themselves and the ways in which their explanations were recorded. We need to ask: Did the informants understand what they were being asked? Were they simply guessing? How can we judge the reliability of their comments? Did they have first-hand knowledge of rock art?

As we have seen, the /Xam informants who came from the Northern Cape were interviewed by Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd. The work was laborious. Lloyd described how //Kabbo ‘watched patiently until a sentence had been written down, before proceeding with what he was telling’.46 She found that ‘he much enjoyed the thought that the Bushman stories would become known by means of books’.47 The informants soon adjusted to the unfamiliar circumstances of dictation. Lloyd wrote of Diä!kwain: ‘It was difficult for him to dictate at 1st, which is probably why I could not get this properly and as he 1st told it to me. I have now heard again that this is the right story.’48

Today we cannot tell to what extent the manner of dictation affected what the /Xam people had to say. In their homeland, the tales were dramatized and acted out; the narrators could give free rein to their histrionic skills. Sitting in a Victorian suburban garden was a different matter altogether. The recording process was also punctuated with questions that Bleek and Lloyd put to the people. Unfortunately, those questions were not recorded, so we do not know to what extent the narratives were shaped by the recorders.

Some of the /Xam informants had worked for colonial farmers and had acquired Dutch names, but that contact seems to have been fairly recent. /Han≠kasso said that his father, Ssounni, ‘possessed no Dutch name, because he had died before the Boers were in that part of the country’.49 //Kabbo (whose acquired Dutch name was Jantje Toorn) still lived for part of the year at a waterhole called //Gubo or Blauputs, its recently acquired Dutch name. It had been ‘owned’ by his grandfather and father.50 He still moved seasonally to another waterhole.51

When these people were shown copies of rock art, they never doubted that they were looking at pictures made by their own people. Diä!kwain made it clear that his father had made rock engravings of gemsbok (large antelope) and quagga (a type of zebra) at a place called !Kánn ‘before the time of the boers’.52 The Cape informants’ familiarity with rock paintings, as distinct from rock engravings, was further attested by a myth that Lloyd obtained from /Han≠kasso. It begins thus:

Little girls they said, one of them said, ‘It is //hára, therefore I think I shall draw a gemsbok with it.’ Another said, ‘It is tò therefore I think I will draw a springbok with it.’ Then she said, ‘It is hára therefore I think I will draw a baboon with it.’53

Clearly, /Han≠kasso was familiar with the practice of painting and, moreover, he had some knowledge of the ingredients used in the preparation of paint. /Hára is black specularite and tò red haematite.

In the region of the Maloti, we have no doubt that Qing was knowledgeable, though not omniscient. Orpen described him as a young man who had ‘escaped from the extermination of their remnant of a tribe in the Malutis’. He was ‘the son of their chief’ and ‘had never seen a white man but in fighting’.54 Confused by what seemed to him muddled accounts of myths, Orpen blamed ‘imperfect translation’. He was not able to record Qing’s actual words phonetically, as did Bleek and Lloyd; we have only his summary translation. As we see in later chapters, however, we have new reasons for believing that not only was the translation reliable but also that Qing had an intimate knowledge of the beliefs and rituals of his people.

The Bleek family was in a better position. They had the ability to record the actual /Xam San words in phonetic script. But even that approach was not plain sailing. As we have seen, the Cape informants were familiar with the practice of making rock art, but they were unfamiliar with the conventions of the art of the more eastern regions of the subcontinent where Stow and Orpen worked and where the copies were made. Consequently, many of their explanations are puzzling and researchers have ignored them, believing the informants to be ignorant and uncomprehending. In turning away from these San explanations, researchers have missed a pivotal opportunity. The situation is paradoxical though not hopeless. To be sure, the copies are, to varying degrees, inaccurate and, moreover, the informants were unfamiliar with some of their conventions. Yet the comments that they offered drew on a fund of authentic San beliefs and practices, and indeed led Bleek and Lloyd into otherwise unknown areas of San belief. A central element of this book is therefore our attempt to draw a distinction between Stow’s questionable work and the /Xam people’s comments; we then extract otherwise missed information from the people’s actual words. As we shall see, appropriately analysed, apparently opaque comments can afford valuable insights into the decipherment of San images.

One way of assessing an informant’s explanations is to ask whether what he said illuminates other panels of images that (a) confirm the overall context of what is depicted and (b) expand what we learned from the informant’s initial comments. In the recent case of a woman of San descent living in the Eastern Cape, we found that she described practices that are recorded in the San ethnography but about which she could not have known except by an authentic San tradition. Where her testimony paralleled what we know from other sources, she was able to expand our knowledge. At one point, however, she used what she said was her own San language but was in fact isiXhosa minus prefixes and suffixes. We must remember that informants are ordinary human beings who may enjoy the attention that researchers give them and the social distinction that remains with them after the researchers have departed. Being human, they sometimes try to please and to retain their hold on the researchers’ interest.

We should also remember that, even as we speak to people in pre-literate societies, we change them: our questions sometimes direct them to aspects of their lives and contradictions in their beliefs about which they do not usually think. Furthermore, what they say in answer to our questions is sometimes shaped by what they think we want to hear or are in a position to comprehend. They may therefore filter out things that they themselves do not think necessary to understand. And, of course, they do not even mention things they consider so obvious that they cannot imagine anyone not knowing about them. Perhaps most importantly, scholars now point out that the so-called ‘primitive societies’ studied by anthropologists had long histories. We should not assume that such societies experienced no change for thousands of years: they were not human fossils.

Nevertheless, we should surely notice that, whatever changes people in recent so-called ‘primitive societies’ went through in their deep past, they remained within what we may loosely call a prehistoric framework until the time of their contact with the expanding West or other peoples. Even when this happens, and an important component of a society changes (say, its economy), it does not follow that the people’s entire way of thinking changes. Writing of the Kalahari San, anthropologists Jacqueline Solway and Richard Lee make a significant point: ‘The evidence for long-established trade relations between foragers and others has been glossed by some as evidence for the fragility of the foraging mode of production. But if it was so fragile, why did it persist?… The majority of the world’s foragers are, for whatever reason, people who have resisted the temptation (or threat) to become like us.’55 We should also remember that Christianity has lasted for 2,000 years, Judaism and Buddhism even longer. Christianity and Judaism persisted through the fall of the Roman Empire, the medieval period and the industrial revolution, yet, whatever happened around them, Christians and Jews steadfastly continued to believe in certain named supernatural beings and their interventions in daily human life. Change is complex. Major economic and political change beyond the ebb and flow of daily human relations is a piecemeal, stop-go process. It is a researcher’s task to sort out what changed in the past and what did not. Both change and continuity in the past must be demonstrated, not simply assumed.

Ultimately, researchers have to consider each San explanation of a rock painting individually. Each must be analysed and assessed. None can be taken at face value.

3: ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS

The Bleek family was meticulous and tried to be ‘scientific’. On the right-hand notebook pages Bleek and Lloyd used two columns, one for the phonetic transcription and one for the English transliteration. The left-hand pages were, for the most part, reserved for additional notes and explanations (Fig. 6).

At first, the informants assisted the process of translation by giving Cape Dutch words that they had learned. They also soon picked up some English. They thus had a foot in two worlds: they were thoroughly familiar with their own heritage, but they had also seen the encroaching Western way of life.

6 A double page from one of Lucy Lloyd’s notebooks (L.V.22); it is dated 21 June 1874. The right-hand page carries the phonetic /Xam text and an English transliteration. The entry concerns the capture of a ‘water-cow’.

Finally, we must remember that Bleek and Lloyd were learning the /Xam language with its clicks and tones that are utterly unfamiliar to Westerners. One of the techniques they used to find the /Xam words for various things was to show the informants illustrated books, point to the things depicted and then ask for the relevant /Xam words. This sort of identification covered animals and different kinds of people. Bleek and Lloyd also took informants to the museum in Cape Town where they gave the /Xam words for various species. These strategies had a significant outcome. When they were shown copies of rock paintings, the /Xam were caught between identifying the things depicted and, as was sometimes more clearly the case, providing a summary of San beliefs about those things. In deciding between what needed mere identification and what called for more complex explanations and interpretations, some informants were caught in a dilemma. This seems to be why some comments are simple identifications of what is depicted, whereas others are, at least for our purposes, more interesting and complex.

Recurrent ‘sorcery’

Overall, Bleek and Lloyd’s informants gave what we may call prosaic identifications of images in the copies 12 times. It seems in these instances that they were responding in the same way that they had responded to other pictures which they had been shown to elicit the /Xam words for various things. They simply identified what they saw depicted and added nothing further.

By contrast, they referred more frequently to what the researchers called ‘sorcery’ than to anything else (Chapters 2 and 3). Along with ‘sorcery’, we include rain-making (Chapters 4 and 5). On four occasions they recalled a myth of which the copies reminded them; in two of these instances the myth involved the rain in a mystical way. In total, the informants referred to ‘sorcery’, rain-making and myths 15 times. This total shows that they did not see the art as a naïve narrative of daily life but rather as something with power and religious connotations. This is certainly the case with the first comment that we decipher. It helps us to grasp what Bleek and Lloyd meant by ‘sorcery’.