CHAPTER 3

‘These are sorcery’s things’

We began to climb the thread – it was the thread of the sky!1

When Diä!kwain commented on the line of dancers depicted in Stow’s copy of a rock painting (Fig. 7), Lucy Lloyd translated his key /Xam word as ‘sorcery’. As we saw in Chapter 2, this English word is misleading because of its modern connotations of ‘black magic’. To build a fuller understanding of what Diä!kwain meant we now need to decipher some more of the actual /Xam San words and phrases that he used.

The /Xam phrase that Lloyd translated as ‘sorcery’ is !gi:-ta didi. Like an ancient Egyptian cartouche, it can be broken down into its constituent parts. As we saw in Chapter 2, !gi: is the supernatural potency that underwrites so much of San religious experience, belief and practice. The suffix -ta (in some instances, -ka) forms the possessive. As a verb, di, with various particles, means ‘to do, act, work, make, become or happen’.2 As a noun, didi is a reduplicative plural meaning ‘doings, actions or deeds’.

Another of the words denoting supernatural potency that we examined in Chapter 2 is //ke:n. It, too, can be combined with di or didi to mean acts performed by !gi:ten, Lloyd’s ‘sorcerers’. The /Xam phrase is //ke:n-ka didi (‘the doings of sorcery’).3 We can find no instance of an informant combining /ko:öde, the third word meaning potency, with di. We are therefore unsure whether /ko:öde had slightly different connotations from the other two words that made it impossible for it to be combined with didi, or whether the informants simply did not happen to use that combination in the conversations that they had with Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd. Be that as it may, it is clear that !gi:-ta didi and //ke:n-ka didi meant the manipulation of supernatural potency by performing various deeds, what we today call rituals.

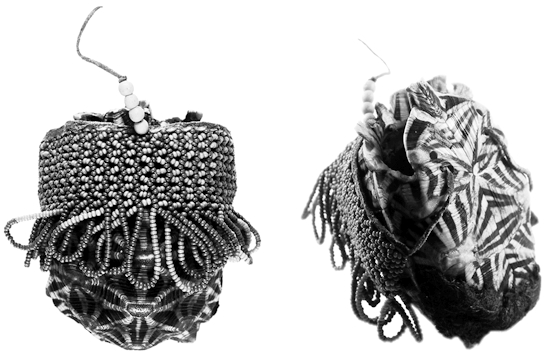

‘Sorcery’ also involved ‘things’. These ‘things’ could be either material or conceptual. Material ‘sorcery’s things’ included, and in the Kalahari still include, small bags or tortoise shells used to contain substances believed to be imbued with supernatural potency (Fig. 16). In the early 1920s, Dorothea Bleek found that Nharo San women carried small tortoise shells filled with buchu; the Nharo gave the name buchu to a category of about a half dozen aromatic herbs.4

16 A tortoise shell decorated with beads. These are used to contain potent substances. They are carried in the trance, or healing, dance, as is shown in Figures 31 and 32. Colours of beads: blue and orange.

The conceptual things involved in ‘sorcery’ included the small, invisible ‘arrows of sickness’ that malevolent Kalahari shamans are still believed to shoot into people. It was the task of benevolent shamans to draw these pathogenic ‘arrows’ out of people, either during a trance dance or, if a person is very ill, at a ‘special curing’ performed by a single shaman who enters trance without the support of clapping women. Then there were what the San call ‘threads of light’. In trance, shamans not only see but also engage with these iridescent lines. We will consider them in more detail in a moment.

‘A sorcerer’s thing’

This preamble about San words and concepts begins to throw light on somewhat enigmatic comments that Bleek and Lloyd’s informants made on the two Stow copies that are the principal focus of this chapter. We deal with them one at a time.

Today what little remains of the images in Figure 17 shows that Stow captured the main elements, though he compressed them vertically so that they would fit on his sheet of cartridge paper. There are also the faint remains of various other images that he ignored; today they are so faint as to be beyond comprehensive recording. At first we suspected that the broad ‘path’ might in fact be a remnant of a painted snake, the rest of the image having faded before Stow visited the site. But, at least as it is today preserved, there is no sign of either a head or a tail, so we cannot be sure that it was indeed part of a snake image. We therefore take Stow’s copy at face value. Overall, we can be confident that, as far as its individual images and general relationships are concerned, Stow’s copy is accurate enough for our purposes. In any event, it was on Stow’s copy that the informant commented, not on the actual rock painting.

Unfortunately, we do not have the original /Xam phonetic text relevant to Figure 17, as we do for that on Figure 7. The ‘explanation by a Bushman’ that Dorothea Bleek published seems less flowing than Diä!kwain’s remarks on Figure 7 and may suggest a different informant. A more likely explanation is that the circumstances under which Lloyd obtained the comments and noted them down may well, on that occasion, have been less conducive to expansive comment than those in which she transcribed the comments on Figure 7. Either way, in the case of Stow’s copy shown in Figure 17, we have what appears to be Lloyd’s paraphrase or perhaps an even later, pre-publication, paraphrase by Dorothea in which she inserted a parenthetical remark:

A sorcerer’s thing (said of the white path-like appearance). Men in the middle and two women at the bottom of the picture. The figure with animal’s head said to be the female Mantis.

17 George Stow’s copy of a rock painting that a /Xam informant said was ‘a sorcerer’s thing’. Curiously, the central figure was said to depict ‘the female Mantis’. Colours: dark red, black, white.

Despite the problems concerning the recording of these remarks and their preparation for publication, this ‘explanation’ contains two key San concepts that we can elucidate with the help of other passages in the Bleek family manuscripts. They are:

– ‘A sorcerer’s thing’

– ‘the female Mantis’

Remarkably, these two concepts appear to be the two sides of a single coin in this particular context.

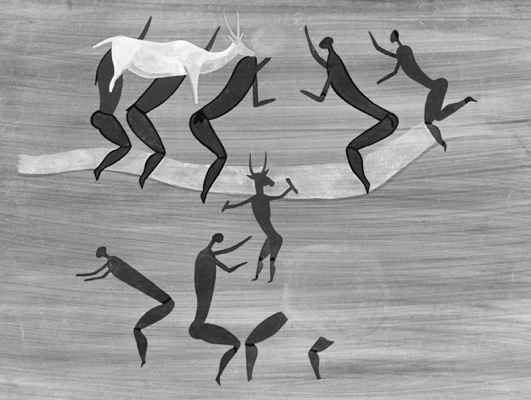

First, the informant spoke of ‘A sorcerer’s thing’. As the parenthesis makes plain, he was referring specifically to the ‘path-like’ motif, the broad, undulating white band with a red line on its lower side: clearly, he did not think that it was an ordinary path through the veld. As the parenthesis implies, the notion of a path was introduced by either Lucy Lloyd or Dorothea Bleek. Nevertheless, five human figures seem to be moving along it, three towards the right and two towards the left. But they and those below the ‘path’ are not in the commonly depicted walking postures in which lines of unidirectional figures are often painted (Fig. 18): the figures in the copy are in postures more akin to those of dancers. We suspect that the informant’s invocation of ‘sorcery’ was triggered, at least in part, by what he took to be a painting of dancing people. Because he situated the images in the realm of ‘sorcery’ – the manipulation of supernatural potency – it is there that we must look for further insights.

It seems likely that the informant thought that the ‘thing’ to which he was referring was one of the conceptual ‘threads of light’ that San shamans say they see in trance – that is, in the spirit realm that they reach by activating potency. When we listen to San people talking about things like ‘threads of light’, it would be easy for us to pass over what they say as fanciful or perhaps merely, and vaguely, ‘mythological’. There is, however, much more to it. ‘Threads of light’ lead us to the centre not just of San religious beliefs but to the actual generation of some of those beliefs.5 To understand how this particular San belief was formed, we need to leave mythology for a moment and turn to another discipline altogether.

18 A procession of striding human figures. Most wear skin cloaks; some carry quivers and bows. Colour: dark red.

Neuropsychological laboratory research has shown that bright undulating lines, sometimes reminiscent of a spider’s web, at other times less ordered, are a type of entoptic phenomenon, that is, a visual hallucination produced by the structure and functioning of the human brain when it enters certain altered states, such as trance.6 These lines and other geometric forms (e.g., zigzags, grids and flecks) differ from religious visions (e.g., those in the Christian tradition that include, say, the Virgin Mary) in that they derive not from the cultural milieu of the visionary but from the neurological structure and electro-chemical functioning of the human brain.

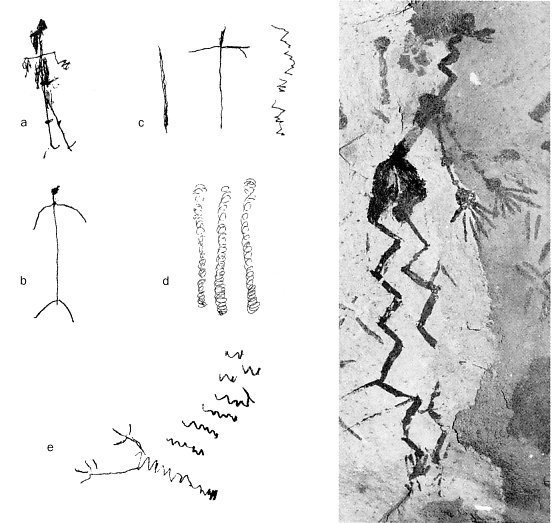

An interesting aspect of entoptic phenomena is that people sometimes feel that they are blending with the geometric forms.7 The psychologist Richard Katz asked Ju/’hoan shamans and men who had never experienced trance to draw self-portraits. The ordinary people drew stick figures while the shamans’ drawings ‘violate the ordinary rules of anatomy: as the body lines become fluid, body parts become separated’ (Fig. 19).8 This experience is seen in a San painting of a man with zigzag legs and neck (Fig. 19).

19 Richard Katz asked ordinary Kalahari San people and trance dancers to draw pictures of themselves. (a) and (b) are drawings made by ordinary people. (c), (d) and (e) are drawings made by trance dancers to show how they conceive of their bodies. The Drakensberg rock painting on the right depicts a comparable self-conception. Colour of rock painting: dark red.

The ways in which visionaries understand zigzags, bright lines and other geometric entoptic forms is, of course, culturally controlled. They take them to be something for which their particular religious tradition has prepared them. All people who enter altered states of consciousness have the potential to see these iridescent lines simply because they are generated by the human brain. On the other hand, people do not necessarily see or value them. In some traditions people ignore the lines and other geometric forms as ‘noise’ that intervenes before they experience ‘true’ visions. That San !gi:ten, who strive to enter trance in medicine dances and other circumstances like special curings, report seeing these visual percepts should therefore come as no surprise. Indeed, shamans around the world report seeing iridescent geometric forms.9 The San are no exception.

Shamans in most San groups speak about engaging with bright ‘threads of light’ when they are in an altered state of consciousness. Indeed, the ethnographic evidence is abundant.10 It is reasonable to conclude that the ‘threads’ of which they frequently speak are the widely reported, neurologically created incandescent lines seen in some altered states. That much is straightforward and indisputable. The important question is: how do the San understand what they see?

In some instances, they speak of these ‘threads’ as if they were a path. Bleek and Lloyd’s informant //Kabbo, himself a 19th-century /Xam San shaman,11 spoke of ‘a Bushman’s path’ that led to a hole in the ground: at death, people followed this path to the spirit realm.12 A 21st-century Ju/’hoan shaman, Cgunta /kace:, similarly spoke of following one of these threads or paths to ‘a big hole’ leading to the spirit world: ‘My teacher showed me the line to the underground hole.’13 In the 1960s, other Ju/’hoan shamans told Katz that, having entered trance (!aia) they follow a path to an opening through which they enter the spirit realm.14 To gain access to this ‘path’ they ‘slip out of their skins’.15 Trans-cosmological travel involves transformation.

Old K”xau, another Ju/’hoan shaman, told Megan Biesele what happens after shamans pass through the hole:

When we emerged, we began to climb the thread – it was the thread of the sky…. When I emerge I am already climbing, I am climbing threads that lie over in the South…. I climb one and leave it, then I go climb another one. Then I leave it and climb on another. Then I follow the thread of the wells, the one I am going to enter!16

The experience of going down into a hole seems to transmute into the experience of rising up into the sky.

The Ju/’hoansi explain that they also walk or glide along these ‘paths’. On the other hand, if they take them to be cords or ropes, they say that they climb them on their way to the supernatural realm in the sky. There they meet and entreat ≠Gao N!a, the great god. The Harvard musicologist Nicholas England learned that the great god sometimes facilitates travel to his place in the sky by letting ‘down a cord to assist the soul’s ascent’.17 The lesser god //Gãuwa also ‘moves from the sky to the ground and across the veld on invisible fibres which criss-cross the surface of the veld like a spider’s web’.18 The fact that different shamans speak of either holding or walking along the ‘threads of light’ does not imply confusion or contradiction. There is a measure of idiosyncrasy in the ways in which individual San shamans interpret the visual products of their nervous systems.

Some shamans speak of engaging with the threads of light in dreams. Sometimes a thread breaks, and a climber falls to earth: ‘His body at home will just sleep.’ Meanwhile the marooned shaman has to wait until it is dark again. He then makes his way back to his camp.19 But usually the threads hold. A Ju/’hoan shaman exclaimed: ‘Isn’t the thread a thing of n/om, so it just has its own strength? You learn to work with it.’20 The threads are, in Bleek and Lloyd’s phrase, truly ‘things of sorcery’.

In the rock paintings of the south-eastern mountains of South Africa and Lesotho we find depictions of long, sometimes bifurcating, thin red lines. Usually, they are fringed with white dots, but numerous variants are known (Fig. 20). The lines interact in a number of ways with other images: in addition to people being shown walking and dancing along them or holding them as if they are cords, the lines sometimes enter and leave the bodies of eland; in other instances, they enter and exit from human figures. Significantly, they frequently enter and emerge from notches or steps in the rock face on which they are painted. These inequalities in the rock become the holes to which the San say the threads lead.

There can be little doubt that the painted lines depict ‘threads of light’, the ‘things’ by which shamans entered and returned from the spirit realm.21 They are the route to the other world, and the paintings and the ethnography combine to show that the spirit realm was believed to lie behind the walls of rock shelters. Not only the lines but also other images, such as those of animals, appear to enter or exit from cracks or steps in the rock walls. This feature of the paintings has led researchers to refer to the rock face itself as a ‘veil’ between this world and the spirit realm.22 This point can hardly be overemphasized. The rock was highly significant, and, as an interface between realms, it became a distinct context in which the painters situated their images.

20 Part of a densely painted panel of San images now preserved in the South African Museum, Cape Town. A ‘thread of light’ can be seen weaving its way through the images. The large supine figure, surrounded by fish and eels, holds a fly whisk and has blood lines on its face. A buck-headed snake bleeds from the nose. Colours: dark red, black, white.

Bearing these San beliefs and rock paintings in mind, we argue that when, in 1875, the /Xam informant spoke of ‘A sorcerer’s thing’, he was thinking of something that only a shaman can see. He said that the broad, undulating line in Figure 17 was a depiction of the hallucinated lines along which shamans move on their way to the spirit realm. That the figures appear to be dancing reinforced his view.

The informant was drawing on widespread San concepts to explain what he was told was a copy of a specific rock painting. But was he right? Here we must enter three reservations.

First, we must allow that the informant may have identified the undulating line in Figure 17 as something different from what the painter intended it to represent. If so, he was nevertheless speaking about a genuine, widely held San belief that related to the activities of shamans. What he said remains significant even if he was wrong about this particular painting. A researcher who discounts what the informant said because he may have misunderstood the copy of the rock painting misses an important source of information.

Second, painted red lines usually fringed with white dots are characteristic of the south-eastern mountains; they are not commonly found in the region where Stow made this copy, nor in the informant’s homeland, about 100 km (62 miles) to the west.

Third, a researcher familiar with the lines characteristic of the south-east would not readily identify Stow’s ‘path-like’ image in Figure 17 as one of them. It is much broader than the lines painted in the south-eastern mountains. Nevertheless, it may be another variant of the ‘threads of light’ concept. It may be an idiosyncratic take on the hard-wired, neurologically generated form. The feet of the figures do seem to relate to the thin red line along the lower margin of the ‘path’ rather than to the broad white band.

Be that as it may, the important point is that the 19th-century informant noticed a relationship between the undulating motif and the apparently dancing human figures. Confronted with copies of what Bleek and Lloyd told him were San rock paintings, he drew on San concepts to explain them as best he could and may have concluded that it must represent a ‘path’ to the spirit realm. The fundamental fact that he had been told that these were copies of San rock art images made him think of ‘sorcery’ because that was the area of San belief that he associated with rock art images. He was thus predisposed to suggest an interpretation drawn from ‘the deeds of sorcery’.

The Mantis

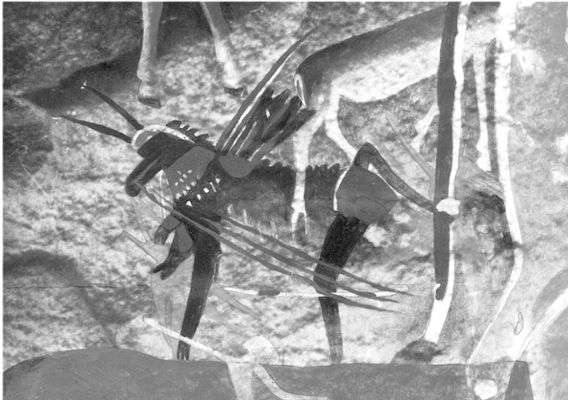

This general understanding of the images in Figure 17 as some of ‘sorcery’s things’ is supported by comments that Lloyd obtained on another of Stow’s copies (Fig. 21). Here, too, there is another reference to the Mantis. This time we have what appears to be more like a verbatim translation than the probably summarized remarks on Figure 17, though with an insertion by Lloyd to aid identification of a figure at which the informant was presumably pointing. The informant again begins by identifying the images as ‘sorcery’s things’:

These are sorcery’s things. I think that one man, to the right of the spectator, having killed a hartebeest becomes like it with his companions. The Mantis going with them. The others had helped him. They become Mantises. The Mantis is not there.

At first glance, this is one of the most puzzling of the statements that Bleek and Lloyd’s informants offered on Stow’s copies. The modern reader can detect little in the explanation to relate it to the copy. Yet it is a gateway to a deeper understanding of what is, for many Westerners, a strange set of beliefs. Whatever thought processes the copy triggered in the informant’s mind, he brought together ideas concerning:

– ‘the Mantis’ and the ‘female Mantis’

– hartebeest hunting

– ‘sorcery’s things’

21 George Stow’s copy of a crowded panel of San rock paintings. This copy shows antelope-headed figures, a baboon, what is probably an ostrich and attenuated human figures. The largest figure is only partially preserved. Colour: dark red.

Before tackling the decipherment of that tripartite nexus of belief, we dispose of what seems to be an ambiguity. The phrase ‘to the right of the spectator’ may be an explanatory interpolation by Lloyd or Dorothea Bleek that refers to the present-day viewer of the copy (the ‘spectator’). On the other hand, the phrase may be the informant’s and refer to the large figure right of centre: it may be regarded as watching the other figures and so be a ‘spectator’. Again, we are not sure which words are Lloyd’s or Dorothea’s and which are direct transcriptions of the informant’s words. The point is, however, not germane to an understanding of the overall meaning of the /Xam man’s observations. We are still left confronting what he meant by ‘The Mantis’ and ‘Mantises’.

The identity of the Mantis is fairly easily established. He is the central figure in southern San mythology.23 He is prominent in both the Cape and Maloti collections of San myths (Chapters 7 and 8). Belief in him was widespread. In the /Xam language his name is /Kaggen. That this word also denotes the praying mantis insect led to the false colonial belief that the San were so debased as to ‘worship’ an insect. In fact, the /Xam San no more worshipped an insect than Christians worship a lamb. Yet, as we shall see, there are occasions when /Kaggen can get feathers (wings) and fly.24 But, for the most part, he is what we may call a trickster-deity, as we discussed in Chapter 1. He was responsible for creating the world, but also for deceiving people; for taking hunters to antelope, but also for helping an antelope to escape. There are always two sides to the Mantis.

Importantly, it seems that /Kaggen was the first shaman. Indeed, the Mantis as the ur-shaman is an understanding that is key to much of /Xam San thought. In many of the tales in which he is protagonist, he behaves like an ordinary San man: he hunts, has a family, and is both wise and foolish. But he also possesses the abilities of a San shaman. He can transform himself into, for example, a hare, a puff adder, a vulture, a louse, a hartebeest, or a ‘little green thing’ that flies.25 Diä!kwain tried to explain /Kaggen’s protean nature to Lloyd soon after the Guy Fawkes celebrations of 5 November 1875:

The Mantis imitates what people do also, when they want us who do not know Guy Fox [sic] to be afraid. They change their faces, for they do not want us who do not know to think it is not a person. The Mantis also … cheats them that we may not know that it is he.26

He could ‘change his face’ into many things. You never knew where you were with the Mantis. In addition, the myths tell of the Mantis diving into waterholes and flying through the air, both shamanic feats. To accomplish ‘miracles’, such as these, he trembles (!khauken), as do shamans when they enter trance.27 He also foretells the future by dreaming, as San shamans do.28 Like a ‘Lord of the Animals’ in other cultures, /Kaggen was believed to possess all large antelope and so their potency: he controlled them as shamans of the game do when they seek to control the movements of antelope. Finally, in one of the /Xam tales he calms the Blue Crane by rubbing her with his sweat, a clear act of shamanic healing29 (for more on myth see Chapters 7 and 8).

At this point, we can return to the puzzling statement that the informant gave in response to Figure 21: ‘The figure with animal’s head said to be the female Mantis.’ Is this another of the Mantis’s many manifestations?

An initial guess may be that the informant was referring, not to the Mantis himself, but to his wife. But the Mantis’s wife is the Dassie (rock rabbit, or hyrax); nowhere is she said to be antelope-headed. A more likely explanation is that the informant was referring to the sexual ambivalence of the Mantis, that is, to another manifestation of his trickster status. He is said to have a digging stick fitted with a bored stone, as well as a man’s bow and arrows.30 The bored stone was associated exclusively with the digging sticks that women used to dig up edible roots.31 Women used bored stones not merely to weight their digging sticks. They also used them to beat the ground and thereby to call up the spirits of the dead.32 The Mantis is also left-handed,33 another indication of femininity in San thought. Finally, he looks after children34 and has a skin for carrying a child.35

Another possibility is suggested by an account that the missionary John Campbell recorded in the mid 19th century. San living near the present-day town of Taung said that the female, lesser god whom they called Ko appeared at a dance and told them where to find game:

She is a large, white figure and sheds such a brightness around, that they hardly see the fire for it; all see her as she dances with them…. They cannot … feel what she is; but should a man be permitted to touch her, which seldom happens, she breathes hard upon his arm, and this makes him shoot better…. After Ko comes up from the ground, and dances a short time with them, she disappears, and is succeeded by her nymphs, who likewise dance a while with them.36

Is this the ‘female Mantis’? Today San shamans in the Kalahari still speak of the bright light that they see in the dance. Here are two such accounts:

During the dance I usually see a light that comes from the people around me. This light goes straight up to the sky. I begin to see this light when I start healing during the dance. First I get filled with pain, then the light comes. It takes away all the pain. When there is no light, I feel pain. When the light arrives, the pain disappears.37

When you take it [medicine], it feels like all ailments are cured and then you feel a light inside you. The strength of the medicine is that it teaches you to see the light. Later you will be able to see the light without taking medicine…. When you see the light during a healing dance, it is so bright that it looks like daylight even though it is actually evening. This light brings about very special kinds of things. I become so tall that I see people as small, as if they are standing far below me. It’s like I am flying over them. Although I am physically blind, I can see everything in this light.38

The light of which these men speak is neurologically generated but interpreted as a being from the spirit realm. The mental experience with which it is associated includes the sensation of attenuation and rising up as well as flight. It is possible, but again by no means certain, that Lloyd’s informant was thinking of this light when he spoke about the ‘female Mantis’.

These are our suggestions as to what the informant could have meant by ‘the female Mantis’. But we remain unsure: this is indeed a puzzling statement.

The Mantis and the hartebeest

In attempting to understand what the informant meant by his remarks about hartebeest hunting and the Mantis, the essence of his comments on Figure 21, we must first ask what he thought he was looking at when he was shown Stow’s copy. Did he see what we today think we see?

The context of becoming Mantises was, he quite clearly said, a hartebeest hunt. The words he used are ‘having killed a hartebeest’. Yet, remarkably, there is no depiction of a hunt in Figure 21, let alone a hartebeest. The nearest thing to a hunt is the figure on the extreme right. It holds a bow and probably has arrows secured in a band or kaross around its shoulders – a commonly painted practice (Fig. 22). Significantly, this figure has a clear antelope head and long, slender horns. The horns are not those of a hartebeest (Figs 23a, 23b); they are more like eland horns, though they curve forward like a rhebok’s horns rather than point straight backwards. Some decades ago, researchers would have immediately identified this figure as a hunter in an animal disguise headdress stalking his prey. As we have seen, the art was formerly widely believed to comprise hunting scenes and other representations of daily life. In Chapter 2 we considered dancing figures that do indeed seem to be wearing caps with small antelope horns, so the hunting explanation needs to be revised (Figs 12–14).

As for the rest of Stow’s copy, the informant saw a group of human figures in various postures. One, in the centre, has its arms raised in a distinctive and oft-repeated clapping posture (a fragment of the dance) that may have suggested the ‘arms’ of a praying mantis, but the informant’s invocation of the Mantis seems to be more general than a reference to this image alone. He said: ‘They become Mantises.’

22 A San rock painting of a baboon-like therianthrope with horns. It bleeds copiously from the nose and carries a bow and arrows (from a coloured photograph). Colours: black, dark red, white.

23a San rock painting of hartebeest heads. The horns and ears are meticulously drawn. Colours: dark red, black.

23b San rock painting of hartebeest heads. The horns and ears are meticulously drawn. Colours: dark red, black.

Other figures in Stow’s copy have attenuations of the body or neck and antelope heads. There is also, probably, an ostrich and, more clearly, a baboon. How would the /Xam informant have responded to such a varied group of, principally, human figures? We suggest that, all in all, he thought he was looking at a depiction of a dance – but not a procession of dancers, as in Figure 7. In Figure 21 it was his knowledge of the shamanic dance and the transformations and mental experiences that take place in it that triggered his remarks. Such transformations are, of course, conceptual ‘sorcery’s things’. Indeed, the informant himself explicitly said: ‘These are sorcery’s things.’

‘Sorcery’s things’, yes, but more specifically they are in some way connected with both hartebeest hunting and the Mantis. The underlying conceptual framework that brings those two apparently disparate elements together is discernible in other parts of the Bleek and Lloyd Collection. We consider the elements one at a time.

Hunting is not merely an economic practice. It is in fact a part of the San conceptual milieu that is related to ‘sorcery’. Even a common activity like hunting is hedged around with beliefs and rituals. In the first place, the 19th-century /Xam San spoke of an empathetic, supernatural bond that they believed existed between a hunter and the antelope that he is tracking, after having wounded it with a poisoned arrow.39 To ensure success, the hunter must behave as he wishes the antelope to behave. He limps and keeps his eyes downcast. If he runs fast, the antelope will run fast and escape. He also refrains from urinating, lest the wounded animal also urinates and so loses the poison. If he has to return to camp before having found the wounded antelope, he must spend a restless night so that the antelope too will not sleep and regain its strength. While in the camp, the man must not smell the scent of a cooking pot: ‘The hartebeest will also smell what the man has smelt, and the poison which the man has shot into the hartebeest will become cool.’40

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas41 describes watching a Ju/’hoan hunter unconsciously imitating a hunted antelope:

Witabe, too, was completely absorbed. Although he did not run after the wildebeest, he got to his feet and gazed after them, unconsciously making a gesture with his hand representing the head and horns of a wildebeest. He moved his hand in time with their running, saying softly: ‘Huh, huh, boo. Huh, huh, boo’, the sound of their breath and grunting as they ran.42

In a sense, the hunter becomes the antelope. He thinks himself into the animal.

These beliefs about hunting go only some way to contextualizing the informant’s comments on Figure 21. In order to have made these observations about the images he must have had a pre-existing notion that, in some way, linked the Mantis to hartebeest. What was this link? A /Xam man said: ‘Our parents used to ask us, Did we not see that the hartebeest’s head resembled the Mantis’s head? It feels that it belongs to the Mantis: that is why its head resembles his head.’43 The way in which a hartebeest’s horns bend backwards does resemble the antennae of a mantis. What people in one culture take to be a resemblance may not be apparent to people in a different culture. In this case, a visual relationship between hartebeest, praying mantises and the Mantis himself, though not obvious to Westerners, was a traditional /Xam San belief.

But there is more to the relationship than mere resemblance. The hartebeest was also one of the Mantis’s many manifestations: ‘The Mantis is one who cheated the children, by becoming a hartebeest, by resembling a dead hartebeest.’44 He could transform himself fully into a hartebeest to the extent that people could not be sure whether they were looking at an antelope or their trickster-deity.

An easily missed implication in what the /Xam man said in response to Stow’s copy (Fig. 21) is that this transformation of people into Mantises happened after the death of a hunted hartebeest. Here we encounter another connection in the closely woven fabric of San ideas and beliefs. After killing a large antelope, the San almost invariably hold a trance dance: there is meat and potency in abundance. The transformation may therefore have been a result of people dancing hartebeest potency. Lorna Marshall was told that, when a man dances the Giraffe Dance, he ‘becomes giraffe’; the same is true of the Honey Dance: he ‘becomes honey’.45 This point explains why the informant said the hunter ‘becomes like it [a hartebeest]’ – and then, in what may appear to be a contradiction, ‘They become Mantises.’ Dancing and hunting are closely related in San thought in another way. The Ju/’hoan respect word for eland, the most potency-filled animal, is tcheni, which means ‘dance’.46 When hunters are tracking an eland, a man may whisper ‘Tcheni is hiding behind that tree.’ They are hunting ‘dance’.

In what sense, then, was ‘[T]he Mantis going with them’, that is, with the hunters? Although he protects hartebeest, the Mantis sometimes leads hunters to animals. As we have pointed out, his unpredictability was at the heart of /Xam San beliefs about him. To secure his assistance, people prayed to him. In the first half of the 19th century, Arbousset and Daumas recorded such a San prayer. The missionaries considered it ‘material and gross’ and indicative of ‘an idolatrous people’, though today it may not, in essence, sound markedly different from many Christian prayers: ‘Give us this day our daily bread.’ After all, the man was praying with his children, not just himself, in mind:

Lord, is it that thou dost not like me?

Lord, lead to me a male gnu.

I like much having my belly filled;

My oldest son, my oldest daughter,

Like much to have their bellies filled.

Lord, bring a male gnu under my darts.47

The word that Arbousset and Daumas translated as ‘Lord’ was ’kaank. It is clearly a form of /Kaggen, the apostrophe at the beginning being the then-common way of indicating a click. Similar prayers addressed to the /Xam trickster-deity /Kaggen were not recorded, but in the Kalahari the Ju/’hoansi call upon their great god //Gãuwa and the (usually malevolent) spirits of the dead to assist them in hunting. Sometimes they do this during a medicine dance: ‘//Gãuwa help us [to get game]; we are dying of hunger.’48 Lorna Marshall writes of a Ju/’hoan man who composed a song that hunters sometimes sing when they are out looking for animals:

//Gãuwa must help us that we kill an animal.

//Gãuwa, help us. We are dying of hunger.

//Gãuwa does not give us help.

He is cheating. He is bluffing.

//Gãuwa will bring something for us to kill next day

After he himself hunts and has eaten meat,

When he is full and is feeling well.49

Although //Gãuwa (also known as ≠Gao!Na) is the great god of the Ju/’hoansi, we can detect elements of the trickster in his supposed behaviour: ‘cheating’ and ‘bluffing’ are prominent characteristics of /Kaggen.

Again, there is a measure of ambivalence. The Mantis loved the hartebeest and the eland. One /Xam man expressed this belief memorably: ‘[H]e made his heart of the Eland and the Hartebeest.’50 The Mantis therefore sometimes tried to frustrate the hunter of a hartebeest. Describing the ways in which the Mantis worked to save a hunted hartebeest and how a hunter may nevertheless be successful, a /Xam man said that the Mantis would come to the hunter’s hut. If the man’s wife chased him (in his insect form?) away, and thus did not properly respect him, he would enable the hartebeest to escape.51

This relationship between /Kaggen and the hartebeest may explain a 19th-century /Xam statement that Sigrid Schmidt, the German folklorist who has catalogued Khoisan myths and folktales, and indeed many other researchers find puzzling:52 ‘My father-in-law [//Kabbo] had Mantises, he was a Mantis’s man.’53 The word Lloyd translated as ‘had’ is /ki. It means ‘to have’ or ‘to possess’.54 /Xam ⊙pwaiten-ka !gi:ten, or game shamans, were said to ‘possess’ creatures as varied as springbok and locusts. At first glance it appears that //Kabbo possessed praying mantises in this way. The puzzling statement, therefore, may simply mean that //Kabbo was a !gi:xa who ‘possessed’, not only mantises, but hartebeests themselves. In discussing the concept of possessed animals and potency, Richard Katz and Megan Biesele make the important point that it does not imply any sort of exclusivity; they suggest that ‘stewardship’ gives a better idea of how the San think of this sort of possession. The shaman conserves potency and sees to its proper use for the benefit of the whole community.55

Another link between hartebeests and /Kaggen is that they shared a nickname. The /Xam called the hartebeest ‘old man Tinderbox owner’,56 and the Mantis was also called ‘Tinderbox’, the /Xam word being ‘//Kandoro’. This word can be broken down into its constituents: //kan means ‘to possess’, while doro is a ‘tinderbox’ or the fire-sticks that the San twirl to light a fire.57 As we saw in Chapter 2, fire activates supernatural potency as shamans dance around it; fire causes potency to ‘boil’ in the shamans, rise up their spines and ‘explode’ in their heads.58 As we have seen, /Kaggen was himself a shaman, probably the first shaman. In this, he parallels the Ju/’hoan great god ≠Gao!Na who provided the people with fire-sticks.59 Many beliefs are pan-San.

We can now begin to fathom what the informant meant when he commented on the Stow copy (Fig. 21). When, in Lloyd’s translation, he said, ‘They become Mantises’, he was probably substituting ‘mantises’ for ‘hartebeests’. The people who had killed a hartebeest became hartebeest-Mantises. Lloyd, mistaking his meaning, seems to have enquired where the Mantis himself was in the picture. The informant replied, logically enough, ‘The Mantis is not there.’ The Mantis was invisible. //Kabbo said that /Kaggen ‘can be by you, without your seeing him’,60 and Arbousset and Daumas learned that ‘one does not see him with the eyes, but knows him with the heart’.61 This may be why no convincing depictions of mantises have been found in San rock art.62

/Kaggen was an invisible, pervasive, omnipresent, protean presence inhabiting crucial areas of San life, especially those of doubtful outcome, such as hunting.63 If he is not visibly there in the hunt, where is he? This a question that Joseph Orpen put to Qing. He replied:

We don’t know, but the elands do. Have you not hunted and heard his cry, when the elands suddenly start and run to his call? Where he is, elands are in droves like cattle.64

There is a mystical region of plenty where /Kaggen lives. We consider it in more detail in Chapters 7 and 8.

In sum, we make the following points to clarify the /Xam man’s puzzling comments on Stow’s copy (Fig. 21):

1 ‘Having killed a hartebeest, [the hunter] becomes like it with his companions.’ As /Kaggen can change into a hartebeest, so too can a man, especially a shaman, who has hunted a hartebeest and appropriated its potency.

2 ‘The Mantis going with them.’ The hunters had implored /Kaggen to assist them in killing an antelope.

3 ‘The others had helped him. They become Mantises.’ Either the hunters become hartebeests by behaving as if they were wounded, or, more likely, they are subsequently transformed at the ensuing dance.

4 ‘The Mantis is not there.’ The informant says that the painter did not depict /Kaggen himself. /Kaggen was an unseen presence, even though he was ‘with them’ in the dance.

Our decipherment of the informant’s comment may at first seem to be a number of confused contradictions, but his words can be understood by setting them in the overall context of San thought. A single San remark cannot be understood in isolation. Even if we cannot formulate a precise, consistent explanation in the English language, we can begin to sense the mercurial nature of San beliefs about supernatural things and the way that they infiltrate the activity of hunting.

‘Sorcery’s things’

When asked to comment on Stow’s copy of San rock paintings (Fig. 21), the 19th-century /Xam San man began with a general remark: ‘These are sorcery’s things.’ Certain aspects of the copy, perhaps ones not immediately apparent to a modern Western viewer, made him think of ‘sorcery’ rather than mundane daily life. It is unclear whether he meant that the individual images depicted ‘sorcery’s things’ (like arrows of sickness and threads of light) or whether he was referring to the paintings themselves. Were rock paintings themselves ‘sorcery’s things’, as were the tortoise-shell boxes used to contain powerful substances? Were they made as things to be used in shamans’ attempts to reach the spirit realm? If images went in and out of the rock face, as they most certainly do, were they merely ‘pictures’ or were they actual ‘things’ that led through the ‘veil’ into the spirit realm? If paintings of eland were reservoirs of potency on which shamans, and perhaps other people as well, could draw, the images themselves were indeed ‘sorcery’s things’.

‘Sorcery’ was a complex concept with many manifestations. One of its principal contexts was, as we see in the next chapter, discovered through San people’s comments on some otherwise inexplicable rock paintings of strange creatures.