CHAPTER 9

‘Simple’ People?

What is most striking about this inquiry is what it reveals about the way the !Kung think. The similarity of their thinking to our own suggests that the logico-deductive model of science may be very ancient, and may in fact have originated with the first fully human hunter-gatherers in the Pleistocene.1

Some of the texts and imagery concerning ‘sorcery’ that we have tried to decipher may help us to understand why, at least in his early work, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl thought that ‘primitive’ people were fantasists. Seated in his armchair and reading accounts of small-scale societies from around the world, he concluded that the minds of ‘primitive’ people were inundated by emotion and imagination to a far greater extent than the sober Westerners he knew in French academe. Part of the problem was that the early ethnographers were more interested in what they considered outlandish beliefs than in the practical, daily lives of the people whom they were studying. As a result, Lévy-Bruhl concluded that ‘primitive’ people did not have a notion of rational causality. The affairs of daily life were believed to be at the whim of unseen beings and forces.

Paradoxically, continuing Western expansion into distant parts of the world seemed to bring both a confirmation and contradiction of this proposition. Inevitably, Westerners saw themselves as different from the people they met in small-scale societies. That difference became a cornerstone in the formulation of Westerners’ own identity: the people they met were ‘other’ than themselves. Hand in hand, two identities were built up: the rational Westerner and the simple, ‘primitive’ native. Some of those ‘primitives’ were, at least in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s 18th-century theory, solitary noble savages, who stood apart from property and social inequality. Rousseau’s idealism contradicted Thomas Hobbes’s earlier (and now more famous) view that, in their natural state, human beings’ lives are ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’ as they struggle with one another. Only strong, consensual government, under which people voluntarily give up some of their freedom, can, as Hobbes saw it, offer escape from decidedly unpleasant primitiveness.

Rousseau’s and Hobbes’s contrasting views of ‘primitive’ people tended to shape the outlook of Westerners as they encountered, rather than merely read about, people like the San. For some, such as the missionaries, the San were unspeakably debased. For others, there was a nobility in their stand against the incursions of the colonists. Neither position did the San much good. Inevitably, they were brought under colonial rule.

In more recent years, anthropologists began to see past these positions. They concluded that the ‘primitives’, within their own terms, were as rational as they themselves. On the other side of the coin, even Lévy-Bruhl came to realize that many Westerners are as irrational as anyone. Many still believe that special people can rise from the dead, that prayers to God can cause natural laws to be suspended and that, when they die, their souls will be transported to an eternal, blissful place.

The study of colonialism and the ways in which people construct their own identities is today a productive industry. Archaeology itself is sometimes alleged to be a weapon of colonialism, along with Christianity and capitalism. Insensitively constructed and handled, the archaeological past can indeed seem to widen the gap between the industrial West and indigenous people. If emphasis is placed on the degree of ‘otherness’, alienation is inevitable. Colonialism itself is, of course, not monolithic. Western expansion played itself out differently in different parts of the world. In some regions, the conflict between the past as pictured by, on the one hand, Western archaeology and, on the other, by indigenous histories is more acute than in others. As attempts to deal with this situation have become more and more sophisticated, prolix and jargon-ridden theory has unfortunately put up a smokescreen that sometimes conceals down-to-earth, practical issues. Often, it seems that many studies are strong on theory but thin on specifics.

In our investigation of San thought and art, we have found the complexity and deeply interrelated nature of the cosmology, myths, rituals and art that we have discussed sufficient to dispel any notion of a naïve, prosaic ‘primitive mentality’. The lives of the San were not ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’ in pre-colonial times.

Changing views

The colonial concept of the San changed over time.2 Early on, they were deemed barbaric and ‘untameable’, inveterate thieves lacking in all subtlety of thought and religion. The 19th-century missionary Reverend Barnabas Shaw declared the San to be ‘slaves of passion. They are deeply versed in deceit, and treacherous in the extreme’3 (original emphasis). In some quarters, this view lasted a long time. One of the most egregious examples of it was published as recently as 1973 in a book that bore the imprimatur of a cabinet minister in the then South African apartheid government. The author wrote: ‘Actually, the Bushmen can almost be regarded as a link between man and the animal world. Man acts largely on pure reason: the animal world relies on blind instinct. The Bushman was midway between the two, often more animal than man, and many of his actions can only be explained on the basis of instinct.’4

Another 19th-century, though less pejorative, view developed under the influence of George Stow, on whose copies of rock paintings Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd asked /Xam San people to comment. It portrayed the San as ‘noble savages’ bravely defending their land against the intrusions of ‘stronger’ people. Retaining the ‘Bushman-as-inveterate-thief’ concept, Stow added a heroic gloss in a now-famous passage:

The last known Bushman artist of the Malutis was shot in the Witteberg Native Reserve, where he had been on a marauding expedition, and had captured some horses…. Thus perished the last of the painter tribes of Bushmen! Thus perished their chiefs and artists ! [sic] after a continuous struggle to maintain their independence and to free their hunting grounds from the invaders who pressed in from every side for upwards of a couple of centuries, a period which commenced with the southern migration of the Hottentot hordes, and did not end until the last surviving clans had been exterminated with the bullet and the assegai, and their bones were left to bleach amid the rugged precipices of the Malutis.5

Those declamatory words were written towards the end of the 19th century. In the 20th century a new notion took hold. The San became known as childlike, highly spiritual conservationists living in harmony with Nature, a view propagated largely by Sir Laurens van der Post.6 They came to be widely seen as an integral part of southern African ecology and a focus of sentimental philosophy:

Perhaps this life of ours, which begins as a quest of the child for the man, and ends as a journey by the man to rediscover the child, needs a clear image of some child-man, like the Bushman, where in [sic] the two are firmly and lovingly joined in order that our confused hearts may stay at the centre of their brief round of departure and return.7

In fact, van der Post’s influence on the public’s ideas about the San exceeded his actual contact with them. His knowledge of the Kalahari hunters and gatherers was slight, and he greatly exaggerated his first-hand contact with the San. His biographer J. D. F. Jones described him as ‘a master fabricator’,8 but he still has many followers. Old ideas die hard, especially when they create distance between ourselves and other people and, as in this instance, foster warm paternalistic sentiments in well-to-do Westerners.

How do these changing views of the San stand up to the evidence we have uncovered?

First and foremost, we believe that San thought and art are intrinsically fascinating. Our ‘Rosetta Stone’ opened up, though by no means fully explored, vistas on a complex world of closely interwoven concepts and images. As we claimed in our Preface, San rock art is arguably more varied, more complex, more meticulous in its minute details and more technically sophisticated than any other rock art. But it is not just beautiful. It has profound symbolic and conceptual depths that we are still researching: we have not reached the end of our journey into San thought. The way in which it is possible to trace an idea, together with its transformations, through San mythology and art speaks of minds that are far from simple.

But we now need to ask in more comprehensive terms about the type, or, more accurately, types, of San thinking that we have come across. Our understanding of San thought is founded on context and a major distinction. An example illustrates this point. When Westerners tried to transmit human speech across immense distances, they thought rationally and came up with the telephone and the wireless. Even if they were religiously inclined, they did not implore God to send the message for them. Even if they believed that the miracles described in the Bible actually took place, they did not expect parallel miracles in their scientific work. But when anthropologists and colonists came to study small-scale societies, many tended to lay more emphasis on mythical thought and on indigenous ‘superstitious’ explanations than on the people’s rationality in dealing with many practical situations. We therefore need to distinguish between San rationality in practical daily life and their thinking in what we see as non-real realms.

The ‘science’ of daily life

Fortunately for our inquiry into San thinking, two Harvard researchers studied Ju/’hoan knowledge in the early 1970s. They were Nicholas Blurton Jones, an ethologist who had studied the behaviour of preschool children as well as that of birds and mammals, and Melvin Konner, an anthropologist and psychologist.9 Their work revealed striking parallels between Ju/’hoan thinking and what we recognize as Western scientific thinking.

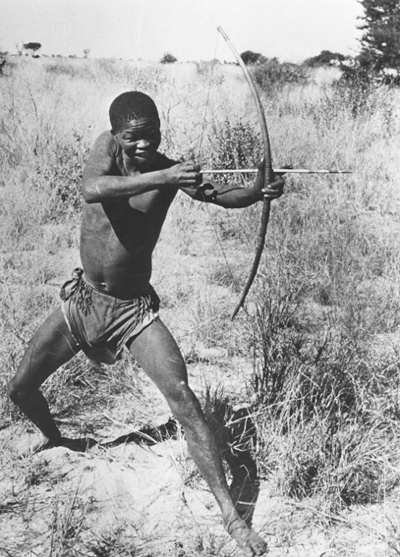

Fundamentally, the Ju/’hoansi do not confuse the sort of thinking that is required to conduct a successful hunt with the thinking that underwrites non-rational beliefs about animals that come to the fore in myths (Figs 56a, 56b). The Ju/’hoansi realize that confusing the two ways of thinking would be disastrous. Non-rational beliefs play only a small role in people’s practical interactions with animals.

In thinking about animal behaviour and, especially, the all-important task of tracking, the Ju/’hoansi are careful to distinguish between data and interpretation. Moreover, hunters discriminate between what they themselves observe and hearsay. Nor do they confuse the animal behaviour that they have inferred from their close observation of animal tracks with what they think may happen as the hunt unfolds. A concomitant point that Blurton Jones and Konner do not make is that a certain amount of ‘theory’, explicit or tacit, is necessary for someone to interpret, even simply to recognize, animal tracks. Still, the San do not confuse hypotheses with observable facts, and they seem uninterested in formulating overarching theories.

We reach an interesting point when we come to the explanations that Ju/’hoansi advance for animal behaviour. Why do animals behave in the sometimes strange and erratic ways that they do? This is where the issue of anthropomorphism enters. There has been a long-standing popular belief that, because the San are said to think of animals as people, they do not draw a distinct line between the two. But, as is so often the case, what Westerners think is a distinction between themselves and other peoples itself turns out to be false. Blurton Jones and Konner concluded that Ju/’hoan explanations for why animals behave in certain ways came close to the explanations that many Westerners advance. The San say that an animal does what it does simply because it wants to, thus imputing human-like characteristics to the animal. This does not mean that the Ju/’hoansi think that animals are people any more than Westerners think their dogs are people when they impute human-like motivations to them. In any event, in dealing with the animals they hunt, and other animals as well, the Ju/’hoansi are more interested in what animals do than in why they do it.

The skills needed to infer what an animal is doing, or will do, from its tracks is fundamental to hunter-gatherer life. They are learned in practice. The Ju/’hoansi do not teach in any formal way. Young men pick up much useful information as people sit around a fire in the evening to discuss the events of a hunt. But, apart from that, the Ju/’hoansi say, ‘You teach yourself’ by participating in hunts.10 According to their egalitarian ideals, the notion of a person lecturing another, even if there is a marked age difference, is anathema.

56a San tracking and hunting skills are legendary.

Once hunters are onto an animal track they learn from one another and thus build up better understandings. As they follow the track, they discuss possible inferences from the details they are able to pick up, changing their minds as new evidence comes to light. As Blurton Jones and Konner remark, the hunters argue in a way not dissimilar to the discussions that they themselves had in their interviews with a number of Ju/’hoan individuals, or, for that matter, in seminars with Western students. The San’s willingness to change their explanations in the light of new data parallels the way in which Western science works.

Non-rational beliefs about animals are, with few exceptions, kept distinct from practical knowledge. One exception is beliefs about infants being ‘possessed’ by birds while they are sleeping. If children clench their hands while asleep, the parents may conclude that they are doing what a bird does with its talons. Infant deaths are sometimes attributed to bird possession.11 As a result, an elaborate ritual must be performed. But the important point is that the Ju/’hoansi never referred to this sort of belief, or to the many myths in which animals behave as if they were people, when they were telling Blurton Jones and Konner about tracking and the kind of animal behaviour that may be inferred from tracks. Nor did the San ever invoke the mythical, remote past.

There are a number of things that the San say must be avoided when out hunting. Many are purely practical, such as using gestures rather than noisy speech to communicate. Others come under the heading of what Westerners call superstitions. For example, /Xam hunters took care not to step on an eland’s spoor.12 Then, when they reached the carcass, they did not allow their shadows to fall on the animal because this was believed to make the eland ‘lean’.13 Today the Ju/’hoansi hold comparable beliefs. They say that a boy who has shot his first eland must not run fast after the wounded animal because ‘if he runs fast, the eland will also run fast’.14 Nor, as we saw in Chapter 3, should he urinate, because if he does so the eland is said to urinate and lose the poison. When the successful boy approaches the dead eland, he crouches down behind an old man and places his arms around him – the position that is adopted by an experienced shaman and a novice who is learning to enter trance.15 Approaching a dead eland with all its extreme potency is akin to approaching the spirit realm in the trance dance. Tcheni (dance), it will be remembered, is the Ju/’hoan respect word for eland.

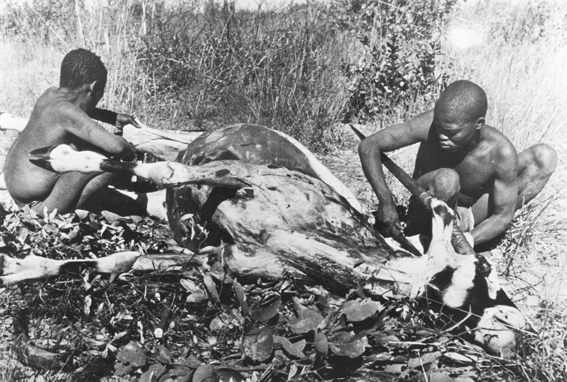

56b When the San have killed an animal, here a gemsbok, they cut it up; it is the task of the man who owned the fatal arrow to distribute the meat.

Hunters need to respect many other observances, but these are kept separate from the actual business of tracking. The supernatural is not allowed to interfere with the efficiency required for survival in daily life. It is peripheral to the main business of tracking. In Western contexts, there are comparable practices: for instance, crossing oneself in a dangerous situation or not walking under a ladder. Some Westerners observe these superstitions, perhaps laughingly; others take them more seriously.

Observing these practices does not materially affect the outcome of a San hunt one way or the other. But, like so many comparable practices in the West, they may give the hunters a degree of self-confidence that is beneficial. The practices may not have material outcomes, but they may have psychological benefits.

Overall, Blurton Jones and Konner’s findings were confirmed by Louis Liebenberg, who has had much experience with Kalahari San people. By going on a great many hunts with them he was able to compare the way they think with a Western philosophy of science.16 Agreeing with what Richard Lee says in the epigraph to this chapter, he argues that the origin of scientific thinking lay in the very earliest human practice of tracking animals and that tracking contributed to the evolution of humans from pre-humans. Going further than Blurton Jones and Konner, Liebenberg believes that the ways in which hunters change their minds as new evidence comes to light presaged the hypothetico-deductive method whereby scientists make and modify (or reject) hypotheses in the light of new evidence.17

Another realm

When we leave practical daily life and the extraordinary skills that the San have in tracking animals, we encounter another sphere of thought. Here we are in the realm of myth and the supernatural. There is a central principle that helps us to understand this mode of thinking. It is transformation.

In mythology worldwide, people transform into animals and vice versa. ‘They all become mantises’ is a phrase we discussed in Chapter 3; we also learned that the Mantis himself can change into a snake, a louse, a hartebeest and ‘a little green thing that flies’. Then, too, a lion can turn into a hartebeest.18 A /Xam !gi:xa could turn into a bird when he wished to find out what was happening in a distant part of the country.19 Another transformation that a /Xam shaman could effect for the same purpose was into a jackal.20 Are these beliefs about transformations markedly different from the Western tradition? No, they are not. In the Bible, Moses’ staff transforms into a serpent21 and the Holy Spirit can become a dove;22 in Catholic ritual, wine and bread transform into the blood and flesh of Christ. In Greek mythology, Hippomenes and Atalanta are changed into lions, and King Minos kept a half-bull, half-man Minotaur in his labyrinth on Crete.

Transformations of this kind are not part of daily life – there is no empirical evidence for them. We therefore need to ask how human beings came to believe that they could change into animals or that one animal could change into another. Is it merely a matter of imagination, or is there more to it? To answer that question, we return to Chapter 1 and the San’s great trance dance. The experiences of the dance – flying to distant places, seeing ‘threads of light’, passing under ground and under water – all originate in the human nervous system as it enters certain altered states, though they are elaborated and embroidered by those who experience them.23

We see this sort of neurologically created transformation in a classic Western instance: a man turns into a fox. The American psychologist and philosopher William James recorded the experiences of a friend who had ingested hashish: ‘I thought of a fox, and instantly I was transformed into that animal. I could distinctly feel myself a fox, could see my long ears and bushy tail, and by a sort of introversion felt that my complete anatomy was that of a fox.’24 Similarly, the French novelist Théophile Gautier, having ingested marihuana resin, wrote: ‘After some moments of contemplation and by a strange miracle, I myself melted into the objects I regarded: I became that very object.’25 In altered states, people can transform into animals or objects.

Having ingested mescaline, another Western subject reported as follows:

I see pulsating stars outlining the shape of a dog overlaying a spiral-tunnel of lights, changing to a real dog which is barking with the words ‘Arf, arf’ coming out of his mouth, changing into a toy dog on wheels changing into a sports car on the same wheeled platform in the desert with the sun high in the sky, changing back into the toy dog still barking, changing back to the sports car with the Road-Runner and another cartoon character driving in the same desert scene.26

Here we observe the shifting, mercurial nature of visions. This Western example reminds us of the Shoshone shaman’s vision in which spirits change form, ‘now a man, now an animal’ (Chapter 8).27 Changing hallucinations can be bewildering.

In yet another report, a Western subject blends not with an animal but with a lattice or fretwork: ‘The subject stated that he saw fretwork before his eyes, that his arms, hands, and fingers turned into fretwork and that he became identical with the fretwork…. “The fretwork is I.”’28

These reports (especially the last) parallel what Richard Katz found when he asked Ju/’hoan shamans to draw pictures of themselves, and men who had never experienced trance to do the same (see Chapter 3). Figure 19 A and C show the way that non-trancers drew themselves while B, D and E show the trancers’ self-images. The bodily transformations that the shamans experience are clear: ‘The fretwork is I.’

The Western transformation into fretwork and the San drawings that Katz obtained illustrate transformation into the iridescent geometrical visual percepts known as entoptic phenomena or form constants, one of which (bright sinuous lines) we saw was one of the ‘things of sorcery’ (see Chapter 3). We must not lose sight of the fact that these mental states need not be induced by psychotropic substances. They can also be caused by rhythmic movements, drumming, fasting, pain, meditation, and certain pathological conditions including migraine. San people in the sort of altered state that routinely occurs without hallucinogens in the dance see and blend with these neurologically produced forms, as they do with objects and creatures in the material world. The reported transformations take place during a dance that consciously focuses on altered consciousness: whatever role imagination may play in other contexts, in the dance it is human neurology that effects San shamans’ transformations.

‘Intellectual brilliance’

The upshot of this evidence is that transformation, among the San and indeed worldwide, is not merely a matter of a fertile imagination, though imagination clearly plays an important role. Although the neurological details may not be fully known, neuropsychological research has shown that the experience of transformation is indisputably wired into the human nervous system. All people, no matter what their cultural background, have the potential to experience culturally informed transformation.29 Transformation is therefore ‘real’ to those who experience it, and it can be repeatedly induced.

So far, we have considered only instances in which subjects have experienced radically altered consciousness. But such transformations are also part of the dreams that everyone experiences. In dreams, people feel themselves changing into animals, other people and things. San transformations are therefore not exceptional: they are part of worldwide experience. The human brain is tuned to transformation.

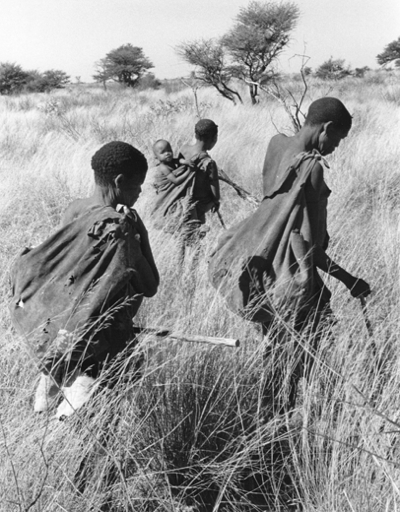

All in all, the strangeness that many Westerners sense in much San mythology and art is no different from the strangeness of Western religious thought. In the Middle Ages and later, people living in Western communities were sometimes burnt alive because they refused to subscribe to the mental experiences of others. The San do not take such violent action. For them, everyone is entitled to believe whatever they choose to believe about the spirit realm, though there are, of course, experiential commonalities that produce beliefs to which everyone can respond. But they do not allow their religious experiences and beliefs to interfere with the normal round of daily life – for the San, hunting and gathering (Figs 57a, 57b). For them, their religious experiences were (and still are) ‘real’. They just did not allow them to affect the outcome of the hunt. They do not necessarily know they are making this distinction; they do not draw an explicit distinction between the sacred and the secular. Non-real things are just not allowed to skew the tracking process.

Blurton Jones and Konner therefore concluded: ‘The two areas seem to be completely different compartments of intellectual life.’30 They went further and argued that, overall, the similarities between the thought processes of Westerners in general and the Ju/’hoansi suggest that ‘[w]e have gained little or nothing in ability or intellectual brilliance since the Stone Age…. Just as primitive life can no longer be characterized as nasty, brutish, and short, no longer can it be characterized as stupid, ignorant, or superstition-dominated.’31

This is our conclusion too. As we have tried to decipher the relationship between the endlessly intricate and varied San rock art and the often initially opaque statements about images that 19th-century researchers recorded, we have been repeatedly struck by the subtlety of San thought and its interrelatedness. The early San and their present-day descendants cannot be called ‘simple’.

Indeed, the integration of San life, myth and art has been our theme. The art was not the sport of quirky individuals. One of the points that gave Egyptologists confidence in their decipherment of the Rosetta Stone was the parallelism between its three registers and, moreover, the way in which, together, they unlocked the hieroglyphics in so many Egyptian monuments. So, too, with the San. The verbatim 19th-century texts and the 20th- and 21st-century accounts of San life and thought mesh in detail with the art: central concepts and cognitive images run through the texts, paintings and myths (flight, travelling under ground, passing through water or mist, ‘threads of light’). The ethnographic record and the painted images illustrate, illuminate and extend one another.

57a Women are highly skilled in detecting signs of edible roots among the grasses of the Kalahari Desert.

57b Back in the camp women prepare the roots and melons for consumption.

‘Tactible’ ideas

Can we say more than ‘run through’? What happens when imagistic ideas are given materiality? Contemplating the diversity of art (visual and verbal), the influential anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote: ‘If there is a commonality [among all arts worldwide] it lies in the fact that certain activities everywhere seem specifically designed to demonstrate that ideas are visible, audible, and – one needs to make up a word here – tactible, that they can be cast in forms where the senses, and through the senses emotions, can reflectively address them.’32 This is what San rock art images did: they made abstract ideas and mental experiences visible and ‘tactible’. The complex, ritualized act of making the images brought ephemeral experiences under control and made them manipulable.

Geertz also made the point that, in looking at works of art, we need to ask what made them important to those who fashioned them or possessed them. He then added that the factors that brought about this importance ‘are as varied as life itself’.33 Questioning the existence of a ‘universal sense of beauty’ as a sufficient motive for making art, Geertz claimed, quite rightly in our view, that if we wish to go beyond ‘an ethnocentric sentimentalism’ we need some ‘knowledge of what those arts are about or an understanding of the culture out of which they come’.

Today we know, at least in large measure, what San rock art ‘is about’: it deals with the vast web of San religion and cosmology. Once made, the images that were a part of that web and took on a life of their own. As performances of myths and shamans’ accounts of their visits to the spirit realm fed back into and helped to shape that web, so too the images fed back into San concepts and, at the same time, impacted on social relationships. We have been able to use the three registers of our ‘Rosetta Stone’ to move beyond any superficial appeal to what Geertz calls a ‘universal sense of beauty’ and to situate painted San images in the web of San thought, a web that, like some spiders’ webs, has a coherent pattern but no finality, neither a beginning nor an end.