In book four of The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, Adam Smith described the early events of globalization that commenced with Christopher Columbus’s discovery of the sea route from Europe to the Americas in 1492 and Vasco da Gama’s voyage from Europe to India in 1498. “The discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope, are the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind,”1 wrote Smith. History has vindicated Smith’s judgment. It is our generation’s fate to usher in another fundamental chapter of globalization, one that requires a rethinking of foreign policy by the United States and other world powers.

Smith noted that globalization should raise global well-being, “by uniting, in some measure, the most distant parts of the world, by enabling them to relieve one another’s wants, to increase one another’s enjoyments, and to encourage one another’s industry.” Smith believed that international commerce and the “mutual communication of knowledge” (the international flow of ideas and technology) would hasten that day of equality.

Smith did recognize that, in the first wave of globalization following the voyages of Columbus and da Gama, the native populations of the Americas and Asia suffered because Europe’s “superiority of force” enabled the Europeans to “commit with impunity every sort of injustice,” including enslavement and political domination. Yet Smith also foresaw a future era in which the native populations “may grow stronger, or those of Europe grow weaker” to arrive at an “equality of courage and force” that could lead to a mutual “respect for the rights of one another.”

In short, Adam Smith foresaw a world in which global trade and the flow of ideas would enrich all parts of the world, not just the European powers that initiated globalization, or the North Atlantic (Western Europe, the United States, and Canada) that first industrialized and dominated the world economy and geopolitics during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Smith’s vision has arrived. Our generation is at a cusp of history, in which centuries of European (and later American) global ascendancy are now being counterbalanced by the rise of “native populations” in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. U.S. foreign policy during the past seventy-five years, and arguably during the past 125 years, has been premised on a world economy led by the North Atlantic region, meaning Western Europe and the United States. That kind of North Atlantic globalization is now reaching an end. The tensions we see now around the world are symptomatic of the passing of the old order.

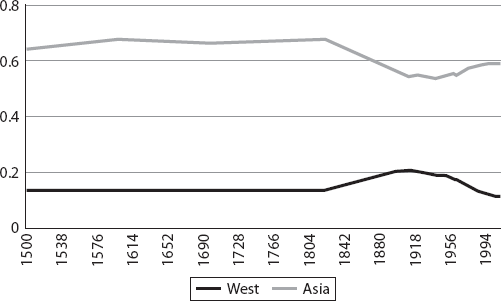

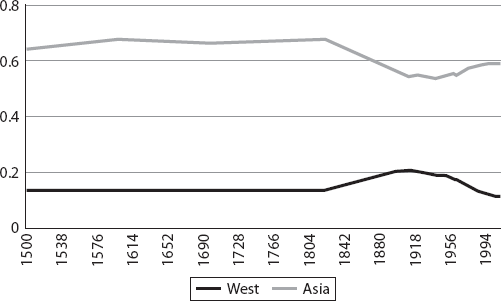

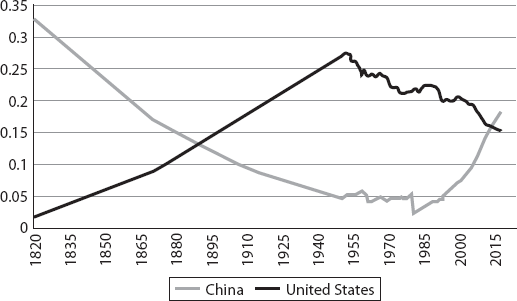

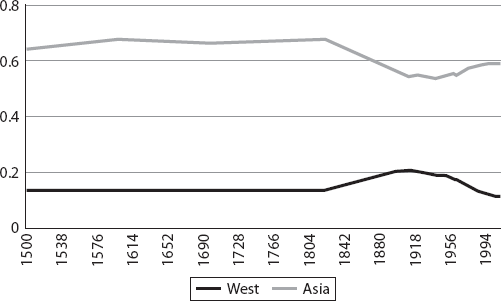

It is useful to chart the changing shares of the world’s population and output from 1500 until 2008, as estimated by historian Angus Maddison. This is done in figure 3.1 for population, and figure 3.2 for output, for two major groups: the West and Asia. The West is defined here as Western Europe plus four “Western offshoots” (Maddison’s phrase): the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Asia includes East Asia, South Asia, Western Asia, and Central Asia.

The main point is this. In 1500, Asia was home to roughly two-thirds of the world’s population and two-thirds of the world’s output. The world was overwhelmingly poor and rural, and the world’s populous agrarian empires were in East and South Asia. By 1913, following a century of Western industrialization, the world economy was now mostly in the West, which hosted a remarkable 54 percent of global output with only 20 percent of the world’s population. Asia’s share of the world economy had declined precipitously, to only 25 percent of global output despite having 55 percent of the world’s population.

While the age of discovery and commerce after Columbus gave Europe footholds in Asia and led to European conquests of the Americas, it was the Industrial Revolution that began in England around 1750—ushered in by the steam engine, large-scale steel production, scientific farming, and the mechanization of textiles—that truly created the Western-led global economy. By 1900, the world economy was largely in Europe’s hands, both economically and politically. Asia was still the center of the global population, but no longer of the world economy.

Note specifically what had happened to China. According to the estimates, China’s share of the world economy was as high as 33 percent in 1820 but only 9 percent by 1913. By 1950, after four decades of revolution, civil war, and invasion by Japan, China’s share of world output had sunk to just 5 percent, probably the lowest in 2,000 years.

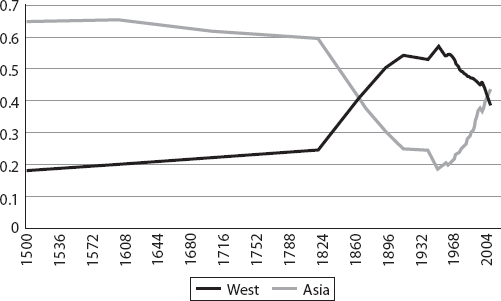

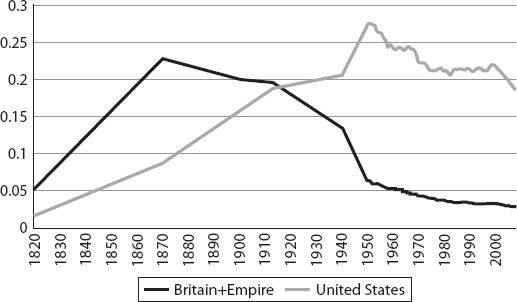

Britain was the first industrial nation, and the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, India, and other imperial possessions) dominated the world economy during the nineteenth century. The economic rise of Britain plus its empire is charted in figure 3.3. There I show the share of world output accounted for by Britain and its empire, alongside the share of the United States. The British Empire constituted the largest economic bloc in the world until the eve of World War I, when the United States equaled the empire in overall size. From the next century, the United States became the largest economy in the world, until it was overtaken by China in 2014 (according to IMF estimates).

During the second half of the nineteenth century, and at least until the start of World War I, the City of London dominated global finance and the British Navy ruled the seas. The era of British dominance is sometimes called Pax Britannica, but pax (peace) was a rosy description of an era when Europe was fighting and conquering lands throughout Africa and Asia, and suppressing violent insurrections (known as “terrorism” to the Europeans) that grew from local resistance to European rule. Britain in particular applied the foreign policy of regime change as the basis of long-term imperial rule. If a particular government in a poor, remote country threatened British interests, toppling the regime and replacing it with a friendly regime was always an option. (Twentieth-century America learned well from the British method of statecraft.)

Britain’s precipitous decline began with World War I, which stripped Britain of financial wealth and left the young generation dead on Europe’s killing fields. The interwar period, 1918–1939, was marked by a decade of instability (1918–1929) followed by the decade of worldwide Great Depression (1929–1939). World War II again utterly devastated Britain, physically, financially, and psychologically. By 1945, the baton of global leadership had decisively passed from Britain to the United States, which was eager to play its new role.

In a key insight, the late economic historian Charles Kindleberger observed that the 1930s was an interregnum between British global economic leadership to the 1920s and American leadership from the early 1940s onward.2 In Kindleberger’s interpretation, the Great Depression occurred with such ferocity, depth, and persistence because there was no single leader to stop the crisis. Britain was too weak to contain the depression, while the United States was too inexperienced to take the global mantle of leadership. Indeed, the United States insisted on facing the Great Depression on strictly national terms, without an orchestrated global recovery effort.

Months after the start of World War II, with France’s quick capitulation to Nazi Germany and Britain’s near defeat soon after, the United States and the Soviet Union became the last redoubts against German domination of Europe. Churchill famously declared that Britain would fight on, from Canada if necessary, until the New World came to the rescue of the Old. The United States did step in, but it lent—rather than gave—Britain the armaments to fight Hitler. As a result, Britain was in debt to the United States, and the United States was well positioned to replace Britain as the dominant world power.

The end of World War II marked (by and large) the end of the European empires in Africa and Asia, though the process of decolonization stretched out over decades and was often violent. The United States often confused decolonization with the Cold War and therefore became a voluntary heir to various anticolonial struggles (which I’ll look at in more detail in chapter 6)—most notably and destructively in Vietnam, where the United States fought unsuccessfully against the national unity of Vietnam for two decades after France’s withdrawal in 1955. Similarly, the United States tried to assert its will in the postcolonial Middle East, in part to keep the Soviet Union out and in part to keep America’s oil companies in.

With Europe’s empires gone, the newly independent nations of Africa and Asia had a new opportunity to invest in their own futures, especially in education, public health, and infrastructure. At least some of the countries made good on that opportunity. China began to stir with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. What had been 200 years of growing European dominance began to give way to a process of “catching up,” whereby at least some of the formerly colonized countries began to adopt modern technologies, spread literacy and disease control, and generally achieve economic development at a pace faster than in the leading North Atlantic countries through incorporation into global production systems. The gap between the North Atlantic leaders and developing-country “followers” finally began to narrow.

The greatest success story was Asia. First, Japan quickly recovered from World War II and began to build an industrial powerhouse. Then came the “Asian tigers”: Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea. And then came China, with the market reforms commencing in 1978, when Deng Xiaoping ascended to power after Mao Zedong’s death. Asia’s example inspired market reforms in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union from the mid-1980s, made possible by the rise to power of Mikhail Gorbachev. The initial results were more political than economic. Eastern Europe peacefully broke away from the Soviet Union in 1989, and then the Soviet Union itself dissolved into its fifteen republics at the end of 1991.

In 1992, U.S. exceptionalists looked out over the world and saw confirmation of their vision of a U.S.-led (and dominated) world. The great enemy was gone. The bipolar power structure of the United States and the Soviet Union was now a unipolar world, and the “End of History”—as Francis Fukuyama famously termed the era, seeing it as “the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government”3—was, they imagined, at hand.

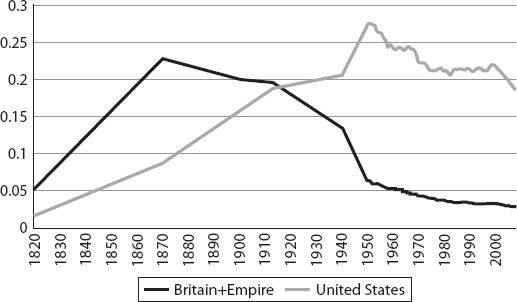

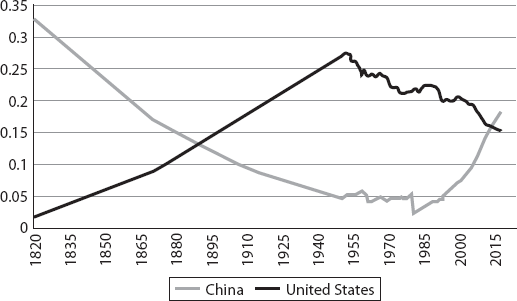

What the exceptionalists didn’t realize is that 1992 would also mark an inflection point in the acceleration of China’s growth. Figure 3.4 shows the U.S. and Chinese share of world output from 1820 until today, using estimates by Angus Maddison for 1820–1979 and the International Monetary Fund for 1980–2017. America’s share of world output peaked in 1950 and has been on a gradual decline since then. China’s output share was very low during most of the century (less than 5 percent, compared with a share of global population of around 20 percent) but then soared after 1978. In 1992, the United States produced 20 percent of world output and China a mere 5 percent. After a quarter-century of supercharged Chinese growth, in 2016 the U.S. share had declined to 16 percent and China’s had slightly overtaken the United States at 18 percent (according to IMF estimates). China has caught up with history.

Moreover, the surge of information technology, which will underpin the next generation of global economic growth, is spreading rapidly throughout the world; the technological revolution will create global wealth, not U.S. wealth alone. China is now by the far the world’s largest Internet user, with around 740 million users in mid-2017, compared with around 290 million American users.4 Broadband access is soaring in all regions of the world, and Internet-based information and communications technologies (ICTs) will transform virtually every sector of the modern world economy: agriculture, mining, manufacturing, energy, transportation, finance, law, medicine, public administration, and others. The United States will not be the only, and often not the first, country to make the transformation to the new ICT-based systems. These will be developed and deployed in all parts of the world.

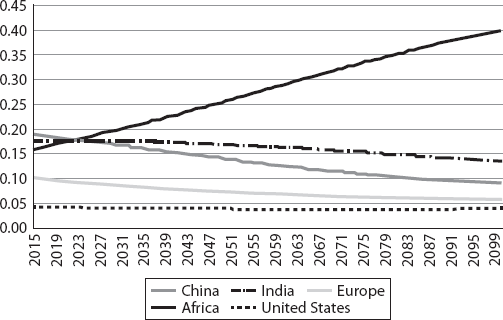

Population trends will also shift the weight of the world economy toward Asia and Africa. Consider this: In 1950, the United States, Canada, and Europe constituted 29 percent of the world’s population. By 2015, this had declined to 15 percent. By 2050, the share will decline further, perhaps to around 12 percent (based on UN projections5). Africa, by contrast, had just 9 percent of the world’s population in 1950, 15 percent in 2015, and around 25 percent expected as of 2050. The U.S. share of the world population in 2050 will be around 4 percent, not too far from its current share.

Here is the key point: The dominance of the North Atlantic was a phase of world history that is now closing. It began with Columbus, took off with James Watt and his steam engine, was institutionalized in the British Empire until 1945 and then in the so-called American century, but has now run its course. The United States remains strong and rich, but no longer dominant.

We are not heading into the China century, or the India century, or any other, but a world century. The rapid spread of technology and the near-universal sovereignty of nation-states means that no single country or region will dominate the world in economy, technology, or population. This is especially true because China’s share of the world’s population will decline sharply, and with it, China’s share of world output. As of 2015, China constituted 20 percent of world population and roughly 18 percent of world output. According to the UN “medium-fertility” projection shown in figure 3.5, China’s share of the world’s population will decline to 10 percent by 2100. It will be Africa’s rapidly growing population that will soar as a share of the world’s total.

FIGURE 3.5 Population shares by major countries and regions, 2015–2100: UN medium-fertility projection

Moreover, with world population growth slowing and the world population aging, countries will be populated by older people. The median age of the Chinese population (the age at which half are older and half younger) was twenty-four years in 1950 and rose to thirty-seven years as of 2015. It is projected to rise to fifty years by 2050. Americans, too, will be no spring chickens, with a median age of forty-two years as of midcentury. History has shown that a bulge of youth in the population has often been tinder for conflict; now we will have a bulge of the elderly.

The United States must rethink its foreign policy exceptionalism in a world that has changed fundamentally, with rapid “catch-up” growth in Asia and now Africa, a worldwide IT revolution still picking up speed, and major changes in global population patterns. The great foreign policy challenge of our age will be to manage cooperation among many competing and technologically advanced regions, and most urgently to face up to our common environmental and health crises. We should move past the age of empires, decolonization, and cold wars. The world is arriving at the “equality of courage and force” long ago foreseen by Adam Smith—but unless we adopt a new foreign policy, we will find that the world has left us behind as we stubbornly insist on going it alone.