When America really was first, notably in the 1940s–1960s, America promoted its interests by cooperating with other nations. The United States opened its markets to the exports of Europe, Japan, and South Korea and shared American know-how with the least developed countries—for example, by promoting the Green Revolution in India in the 1960s. The United States developed the blueprints for the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT, the forerunner of the World Trade Organization), the World Health Organization, the regional development banks, and countless other international efforts aimed at spreading economic prosperity.

The point is not that these actions were purely altruistic, imposing costs on the United States that only helped other countries. The point, rather, is that the United States invested in global public goods—in win-win activities—knowing that by playing its part, even a disproportionate part, as the world’s leading economy and military power, it would reap a significant long-term benefit along with the other nations. Leadership does not mean squeezing other nations to enrich one’s own country. Leadership is finding opportunities for mutual gain and creatively pursuing them, even funding projects entirely at times, when all countries end up ahead.

President John F. Kennedy famously put the issue of development assistance this way in his inaugural address:

To those peoples in the huts and villages across the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required—not because the Communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.

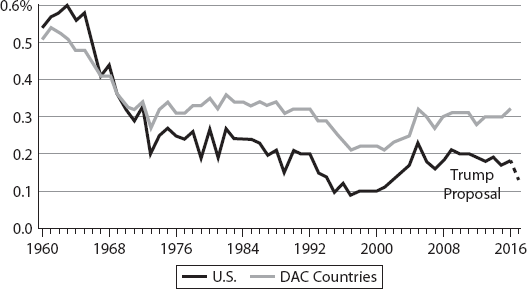

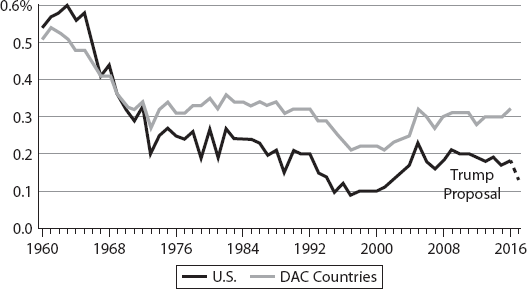

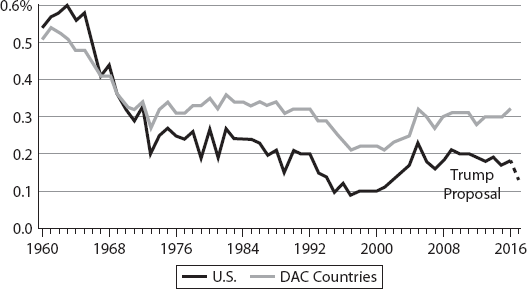

America’s efforts can be measured by official development aid (ODA) as a share of gross national income (GNI), as shown in figure 15.1. During the Marshall Plan years, U.S. aid levels were about 1 percent of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP, almost the same as GNI). During the 1950s, the aid levels trended downward, but were still on the order of 0.6 percent of GDP in the early 1960s. This fell further to 0.2–0.3 percent in the 1970s and 1980s, then plummeted below 0.2 percent at the end of the Cold War, falling to 0.1 percent of GDP in 1999 during the Clinton administration. The aid levels increased under George W. Bush, who as we’ll see made a notable effort to fight AIDS, TB, and malaria, with ODA/GNI rising to around 0.2. Under Obama the aid effort fell back again to around 0.18, and it looks set to fall further under Trump, perhaps to around 0.15.

FIGURE 15.1 Official development assistance as a percentage of national income: United States versus all donor countries, 1960–2016. Data from Net ODA, OECD.org: https://data.oecd.org/oda/net-oda.htm.

This downward trend broadly tracks America’s declining readiness to invest in global public goods generally. In the first decades after World War II—the heyday of the American Century—the United States was ready to lead in deeds as well as words. Representing around 30 percent of world GDP and more than half the combined income of the United States, Europe, and Japan, the United States not only was keen to promote the new U.S.-led internationalism, but also knew that positive results depended on America’s footing much of the bill, admittedly to its own advantage as well as that of the countries receiving the aid.

Starting in the early 1970s, the United States began to pull back from global financial leadership. In 1971, President Richard Nixon unilaterally severed the fixed exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and gold (thirty-five dollars per ounce), thereby ending the “gold standard” of the postwar monetary system. The United States refused to bear the macroeconomic costs that would have been needed to preserve the dollar’s peg to gold as was called for under the globally agreed monetary arrangements, and as was expected by other countries. The rest of the world, which was left holding dollar reserves that were now reduced in value, suffered the cost of Nixon’s unilateral action. This action marked a watershed, a turning point in America’s readiness to foot the bill for the global financial system.

America’s will to leadership was further undermined by new developments in North-South diplomacy. The postcolonial nations made an appeal at the United Nations for a New International Economic Order (NIEO) that would ostensibly treat the developing countries more fairly—for example, by boosting the world relative price of primary commodities through methods such as export cartels and commodity stabilization arrangements. The developing countries began to claim, with increasing determination, that the existing international economic order was unfair to the late industrializers, and that the system needed to be reformed. If an oil cartel like OPEC could push up international prices, they reasoned, so too could cartels for products such as sugar, coffee, tobacco, cocoa, and others.

In the face of this call for global equity, the United States issued a resounding no. The international economic system, said one U.S. administration after the next, is fair enough. If developing countries wanted to catch up, they’d have to do it on their own, presumably by mastering new areas of technology and skill, not by artificial arrangements to boost the prices of their commodity exports. A few countries, such as South Korea and Singapore, were able to follow that route. Others, however, remained stuck with their traditional commodity exports and found their national income levels stagnant or declining as their populations grew while their terms of trade declined.

Just as significantly, the United States lost the political will to support the rapid catching-up of the developing countries. The call for a NIEO was taken as an affront, an appeal to naïve socialism and redistribution, a violation of the principles of market competition. The fact that many of these same countries were involved in OPEC, the ascendant oil cartel, added to the sting of NIEO. The United States made clear that it had had enough. When developing countries fell into financial crisis in the early 1980s (following sky-high U.S. interest rates), the United States took a mostly hard-line position: repay the debts or suffer the consequences.

The U.S. will to lead globally had its final moment of glory in the postcommunist revolutions of 1989–1991. After all, the emergence of postcommunist governments in Eastern Europe was the triumph, or so it seemed, of decades of America’s Cold War efforts. While America’s generosity to the newly democratic nations of Eastern Europe can easily be exaggerated, the fact remains that the United States saw that investing in Eastern Europe’s transformation, democratization, and renewed growth would enhance U.S. exports, geopolitical leadership, and returns on overseas investments.

I have already recounted the stark difference between America’s financial approach toward Poland in 1989 and Russia in 1991. The first showed U.S. financial leadership, the other the abnegation of leadership. Yes, the United States still wanted to lead after 1991, but through military dominance over its former adversary rather than through cooperative economic strategies. Official development assistance generally plummeted in the 1990s. Clinton wanted a post–Cold War peace dividend without having to reinvest any of it abroad to build a new world order. With no geopolitical competition from the Soviet Union for the hearts and minds of the world’s poor, the United States no longer had to use development assistance as an inducement for countries to join the U.S. sphere of influence.

I therefore see several reasons for America’s shrinking interest in global economic, financial, and diplomatic leadership. One was petulance. The United States was annoyed by demands for global economic reform coming from the developing countries; they would take the global system on America’s terms, or else. Another was the end of the Cold War. The United States had won; the Soviet Union had lost. The United States no longer needed to lure developing countries to its side and away from the Soviet Union. A third was arrogance. Why lead with inducements (carrots) when military power (sticks) will do just fine? The United States turned from “soft” power to “hard” power after 1991, especially since the Soviet Union was no longer present as a military counterweight (or so the United States thought, until Russia’s intervention in Syria in 2015).

Perhaps most fundamental of all, and underpinning some of the factors just named, was America’s relative decline in economic strength. The U.S. economy did not fail; much of the world caught up, or at least narrowed the gap. Europe and Japan rebuilt after the war. Developing countries invested in education and job skills. China experienced the most rapid, sustained economic growth of any large region in the world after market reforms began in 1978. The result was that America’s share of world output fell from its peak of around 30 percent in 1950 to 20 percent by 1990 and just 15 percent today. As the U.S. share declined, America’s readiness to supply global public goods fell even faster. And because the American political system after 1980 failed to redistribute wealth and income from the top to the bottom, a significant part of the U.S. population experienced an absolute decline in inflation-adjusted income, despite the overall growth of the U.S. economy.

Yet here is where America has badly misjudged its own situation and the world’s. While it is understandable that the United States would no longer bankroll global development as it did in the 1940s–1950s, the need for global public goods has not abated just because U.S. economic dominance has diminished. The global needs remain, for example, to fight global poverty and battle human-induced climate change. Rather than turning its back on such global challenges, the United States should be calling on other nations to join with it in meeting the challenges together. Instead, the United States has abdicated its responsibilities by slashing aid, relying excessively on hard power, and renouncing the instruments of global diplomacy.

Not only has the United States turned its back on development assistance; it has turned its back on global diplomacy as well. The United Nations was America’s creation, the remarkable vision of Franklin D. Roosevelt as the best hope to keep the peace after World War II. So too was the web of new international institutions within and alongside the United Nations. U.S. diplomats seemed to be everywhere for the first quarter-century after the war, helping to launch development programs, instill environmentalism, and share the fruits of science. But then, for the same reasons that the United States cut back on global development financing, it began to cut back on global diplomacy as well. The bipartisan foreign policy of the Roosevelt-Truman-Eisenhower era increasingly gave way to dissension. Hard-liners decided that U.S. military dominance, rather than diplomatic persuasion and development financing, was the real key to securing America’s interests.

From the late 1970s onward, international treaties became increasingly suspect to the American right wing. Since 1994, the U.S. Senate has not ratified a single UN treaty, the last being the Chemical Weapons Convention in 1993. Ratification requires a two-thirds majority, implying bipartisan support, and generally the Republican Party has stood nearly united against ratification. Here are some of the important UN treaties pending Senate ratification, with few if any prospects for adoption:

| 1979 |

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, signed but not ratified |

| 1989 |

Convention on the Rights of the Child, signed but not ratified |

| 1989 |

Basel Convention on Transboundary Hazardous Wastes, signed but not ratified |

| 1991 |

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, not signed |

| 1992 |

Convention on Biological Diversity, signed but not ratified |

| 1996 |

Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, signed but not ratified |

| 1997 |

Kyoto Protocol, signed with no intention to ratify |

| 1997 |

Ottawa Treaty (Mine Ban Treaty), not signed |

| 1998 |

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, not signed |

| 1999 |

Criminal Law Convention on Corruption, signed but not ratified |

| 1999 |

Civil Law Convention on Corruption, not signed |

| 2002 |

Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture, not signed |

| 2006 |

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, not signed |

| 2007 |

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, signed but not ratified |

| 2015 |

Paris Climate Agreement, signed but declared intention to withdraw in 2020 |

In many of these cases, the United States stands alone or almost alone against the rest of the world. Only four countries have failed to ratify the convention on elimination of discrimination against women (CEDAW)—the United States plus Somalia, Sudan, and Iran. Only the United States is not a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Only the United States is not a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Almost all countries have ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; the United States stands with Uzbekistan, Libya, Chad, Belarus, and a few others in not ratifying that treaty.

During the last quarter-century, the Republican Party has completely turned its back on global environmentalism, largely because the coal, oil, and gas lobbies came to dominate the party. In 1992, Republican president George H. W. Bush signed three major multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) at the Rio Earth Summit: the Convention on Biological Diversity, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification. Yet that proved the be the last gasp of Republican Party environmentalism. Since then, the U.S. Senate has turned its back on the treaties and on related global environmental measures.

Regarding the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the Senate simply refused ratification after Bush signed the treaty. Several western-state Republican senators argued that protecting biodiversity under the treaty would undermine private property rights. In the end, private land rights took precedence over the survival of biodiversity.

Regarding the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Senate ratified the treaty but then refused to implement it, and likewise refused to consider the 1997 Kyoto Protocol that would have put the treaty into operation. The 2015 Paris Climate Agreement has now superseded the Kyoto Protocol. The agreement was designed by the Obama administration and other negotiating partners to circumvent the need for Senate ratification. Instead, the Republican Senate leadership successfully convinced President Trump to announce plans to withdraw from the agreement in 2020, the earliest possible date under the terms of the agreement.

Regarding the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), the Senate ratified the treaty but did absolutely nothing to support it. The aim of the UNCCD is to support dryland countries to confront and overcome the scourges of drought and land degradation. Dryland regions such as the African Sahel, the Horn of Africa, the Arabian Gulf, and Western and Central Asia, are exceedingly vulnerable to global warming and the overuse of surface water and groundwater. The dryland regions have become conflict hotspots in part because of food and water insecurity. Yet the United States has not utilized the UNCCD as an instrument of response, turning to military approaches instead.

With Trump’s presidency, the United States is completing the move from postwar leader to twenty-first-century rogue state. Trump is not just cutting aid and rejecting global treaties. He is undermining UN diplomacy itself. Trump and UN ambassador Nikki Haley have taken delight in thumbing their noses at UN diplomats, with Haley declaring repeatedly that “we are taking down names” of countries that oppose the United States, and threatening to cut aid to countries that cross the United States diplomatically.

Trump and Haley have already made good on their threat to cut funding to the UN itself; on Christmas Eve 2017, America’s gift to the world was a $285 million cut in the United Nations’ regular budget. Technically, the UN regular budget reflects a consensus decision of the body’s 193 member states, but the United States was clearly the prime mover in pushing for the cut. Indeed, Nikki Haley, the U.S. ambassador to the UN, accompanied the Christmas Eve announcement with a warning that the United States would be on the lookout for further reductions.

The budget cuts will make it that much harder for UN agencies to prevent wars, help millions of people displaced by conflicts, feed and clothe hungry children, fight emerging diseases, provide safe water and sanitation, and promote access to education and health care for the poor.

President Trump and Ambassador Haley make much of the bloated costs of UN operations, and there certainly is room for some trimming. But the world receives an astounding return on its investments in the UN, and member countries should be investing far more, not less, in the organization and its programs.

Consider the sums. The UN regular budget for the two-year period 2018–2019 will stand at around $5.3 billion, $285 million less than the 2016–2017 budget. Annual spending will be around $2.7 billion. The U.S. share will be 22 percent, or around $580 million per year, equivalent to around $1.80 per American per year.

What will Americans get for their $1.80 per year? For starters, the UN regular budget includes the operations of the General Assembly, the Security Council, and the Secretariat (including the secretary-general’s office, the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the Department of Political Affairs, and administrative staff). When a dire threat to peace arises, such as the current standoff between the United States and North Korea, it is the UN’s Department of Political Affairs that often facilitates vital, behind-the-scenes diplomacy.

In addition, the UN regular budget includes allocations for the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the UN Development Program, the World Health Organization, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the UN’s regional bodies (for Asia, Africa, Europe, Latin America), the UN Environment Program, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (for disaster response), the World Meteorological Organization, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, UN Women (for women’s rights), and many other agencies, each specializing in global responses to crises, conflicts, poverty, displacement, environmental hazards, diseases, or other public needs.

Many UN organizations receive additional “voluntary” contributions from individual countries interested in supporting specialized initiatives by agencies such as UNICEF and the World Health Organization. Those agencies have a unique global mandate and political legitimacy, and the capacity to operate in all parts of the world.

The silliness of the U.S. attack on the size of the UN budget is best seen by, once again, comparing it to the Pentagon’s budget. The United States currently spends around $700 billion per year on defense, or roughly $2 billion per day. Thus, the total annual UN regular budget amounts to around one day and nine hours of U.S. military spending. The U.S. share of the UN regular budget equals roughly seven hours of Pentagon spending. Some waste.

Trump and Haley are squeezing the UN budget for three reasons. The first is to play to Trump’s political base. Most Americans recognize the enormous value of the UN and support it, but the right-wing fringe among Republican voters views the UN as an affront to the United States. A 2016 Pew survey put U.S. public approval of the UN at 64 percent, with just 29 percent viewing it unfavorably.1 Yet the Texas Republican Party, for example, has repeatedly called on the United States to leave the UN.

The second reason is to save on wasteful programs, which is necessary in any ongoing organization. The mistake is to slash the overall budget, rather than reallocate funds and increase outlays on vitally needed programs that fight hunger and disease, educate children, and prevent conflicts.

The third, and most dangerous, reason for cutting the UN’s budget is to weaken multilateralism in the name of American “sovereignty.” The United States is sovereign, Trump and Haley insist, and therefore can do what it wants, regardless of opposition by the UN or any other group of countries.

This attitude was on display in Haley’s speech to the UN General Assembly session on Jerusalem. The UN Security Council had voted fourteen to one against the United States to oppose Trump’s moving the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem; countries friendly to the United States and Israel warned vigorously that Trump’s move not only violated international law but would threaten the peace process. The UN General Assembly also took up the issue, voting 128 to nine against the United States, with thirty-five abstentions, despite harsh U.S. warnings of aid cutoffs. Haley told the rest of the world:

America will put our embassy in Jerusalem. That is what the American people want us to do, and it is the right thing to do. No vote in the United Nations will make any difference on that. But this vote will make a difference on how Americans look at the UN and on how we look at countries who disrespect us in the UN. And this vote will be remembered.2

This approach to sovereignty is exceedingly risky. Most obviously, it repudiates international law. In the case of Jerusalem, resolutions adopted by the General Assembly and the Security Council have repeatedly declared the final status of Jerusalem to be a matter of international law. By brazenly proclaiming the right to override international law, the United States threatens the edifice of international cooperation under the UN Charter.

Yet another grave danger is to the United States itself. When America stops listening to other countries, its vast military power and arrogance often lead to self-inflicted disasters. America Firsters like Trump and Haley bristle when other countries oppose U.S. foreign policy; but these other countries are usually giving the United States their good and frank advice that the United States would be very wise to heed. The Security Council’s opposition to the U.S.-led war in Iraq in 2003, for example, wasn’t intended to weaken America, but to protect the United States, Iraq, and indeed the world, from America’s rage and shocking blindness to the facts.

How the rest of the world might react to such posturing by the United States is clear from the Turkish foreign minister’s succinct rejoinder to Haley: “Dignity and sovereignty are not for sale.”3 The United States can continue to be a bully and to go its own way, but the world will not give in.