PREVIEW

Mass communication lies at the heart of political discourse. It informs governments and citizens, it defines the limits of expression (fewer in democracies than in authoritarian states), and it provides us with ‘mental maps’ of the political world outside our direct experience. The technology of mass political communication has changed dramatically over the past century, taking us from a time when newspapers dominated to the era of broadcasting (first radio and then television), and bringing us to the age of the internet, with instant information in unparalleled quantities from numerous sources, at least for the half of the world’s households that currently have access. As technology has changed, so have the dynamics of political communication; conveying and receiving news is increasingly interactive, with consumers playing a critical role in defining what constitutes ‘the news’.

This chapter begins with a brief survey of the evolution of the mass media and political communication, progressing to an assessment of the as-yet not entirely understood implications of social media. It then looks at how the political influence of mass media is felt, reviewing the key mechanisms of influence: reinforcement, agenda-setting, framing, and priming.After reviewing recent trends in political communication (commercialization, fragmentation, globalization, and interaction), the chapter compares different media outlets, and ends with an assessment of political communication in authoritarian states.There, the marketplace of ideas is more closely controlled, though the internet in general, and social media in particular, have created more space for free communication among some citizens.

CONTENTS

• Political communication: an overview

• Media development

• Media influence

• Recent trends in political communication

• Comparing media outlets

• Political communication in authoritarian states

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • Communication is a core political activity and its study forms an important part of political analysis. In particular, a free flow of communication provides one test for distinguishing between liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes. |

| • The technology of mass media has undergone rapid change over the last century, most importantly with the rise of the internet. But the political impact of the internet remains a matter of much speculation, particularly given that levels of access vary, and that half the households in the world are still unconnected. |

| • Researchers identify four classes of media effects: reinforcement, agenda-setting, framing, and priming. But much of our understanding of these effects is based on single-country studies, and comparative data on political media effects are scarce. |

| • Too often, mass media coverage is assumed to be influential without there being any evidence cited in support. A broader perspective suggests that the media provide a structure for our worldview, rather than simply an influence on it. |

| • Current trends – including the shift to more commercial, fragmented, global, and interactive media – are reshaping the environment of political communication. These developments impact politicians, voters, and the relationship between them (e.g. election campaigns). |

| • In authoritarian regimes, leaders have varied and often subtle means for limiting independent journalism, though in the internet age censorship is rarely complete. |

Political communication: an overview

Society – and, with it, government and politics – is created, sustained, and modified through mass communication. Without a continuous exchange of information, attitudes, and values, society would be impossible, as would meaningful political participation. Efficient and responsive government depends on such an exchange, without which leaders would not know what citizens needed, and citizens would not know what government was doing (or not doing). Mass communication is also a technique of control: ‘Give me a balcony and I will be president’, said José Maria Velasco, five times president of Ecuador. It is, in short, a core political activity, allowing meaning to be constructed, needs transmitted, and authority exercised.

Assessments of the quality of political communication are key to the process classifying political systems. Democracies are characterized by a free flow of information through open and multiple channels. Dahl (1998: 37) argues that a liberal democracy must provide opportunities for what he calls enlightened understanding: ‘within reasonable limits as to time, each member [of a political association] must have equal and effective opportunities for learning about relevant alternative policies and their likely consequences’. In a hybrid regime, by contrast, dominance of major media outlets is a tool through which leaders maintain their ascendancy over potential challengers. For their part, authoritarian regimes typically allow no explicit dissent at all. Media channels are limited and manipulated, and citizens – as a result – must often rely more on unofficial channels, including the internet, for their political news.

Political communication: The means by which political information is produced and disseminated, and the effects of this information flow on the political process.

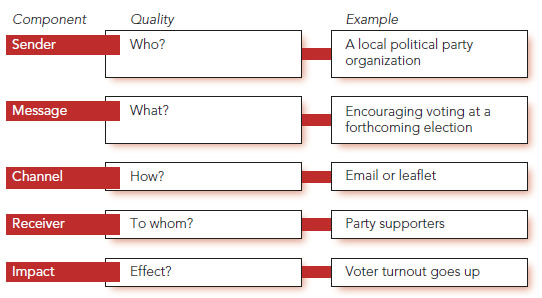

Even though much recent research in political communication focuses on the message itself and the meanings embedded within it, the transmission model is – as we will see – a helpful way of understanding the broad process of communication via mass media. This takes into consideration the sender of the message, the nature of the message itself, the channel used, the user, and the impact of the message. The danger of focusing solely on content is that we learn nothing about the receivers and even less about the political effect of the message. Blaming media bias for why others fail to see the world as we do can be tempting, but is usually superficial and unenlightening.

Jones (2005: 17) has few doubts about the importance of the media to politics in democracies. He judges that media consumption should now be seen as a vital form of political participation:

Media are our primary point of access to politics – the space in which politics now chiefly happens for most people, and the place for political encounters that precede, shape and at times determine further bodily participation (if it is to happen at all) … Such encounters do much more than provide ‘information’ about politics.They constitute our mental maps of the political world outside our direct experience. They provide a reservoir of images and voices, heroes and villains, sayings and slogans, facts and ideas that we draw on in making sense of politics.

Politics and government is only partly about creating efficient institutions and developing effective poli-cies; it is also about persuasion and information, whether this takes place in the free market of ideas or whether it is manipulated for political ends.

Media development

The political significance of the media is famously encapsulated in the quip attributed (depending on the source used) either to Edmund Burke or to Thomas Macaulay, both British politicians (see Spilchal, 2002: 44). Noting the existence of three existing political ‘estates’ (the monarchy, the peerage, and the House of Commons), Burke or Macaulay referred to the reporters sitting in the gallery of the House of Commons as the fourth estate, a term that has since been used to denote the political significance of journalists.

Fourth estate: A term used to describe the political role of journalists.

Although we take access to a variety of mass media for granted, their rise has been a relatively recent development, dating back no more than two centuries (see Figure 14.1). The first printed book dates from China in 686, the Gutenberg press started printing with moveable type in 1453, and the first newspaper appeared in 1605. But most of what we now consider mass media came with the development of new technology in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, allowing true mass communication. This, in turn, facilitated the emergence of a common national identity and the growth of the state. For the first time, political communication meant a shared experience for dispersed populations, providing a glue to connect the citizens of large political units.

FIGURE 14.1: The evolution of mass media

Mass media: Channels of communication that reach a large number of people.Television, radio, and websites are examples. Until the advent of social media, mass media were one-to-many and non-interactive.

Newspapers

Widespread literacy in a shared language permitted the emergence of popular newspapers in Western states, the key development in political communication during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Dooley and Baron, 2001). Advances in printing and distribution opened up the prospect of transforming party journals with a small circulation into populist and profitable papers funded by advertising. By growing away from their party roots, newspapers became not only more popular but also, paradoxically, more important to politics.

In compact countries with national distribution, such as Britain and Japan, newspapers built enormous circulations, and owners became powerful political figures. In inter-war Britain, for example, four newspaper barons – Lords Beaverbrook, Rothermere, Camrose, and Kemsley – owned papers with a combined circulation of over 13 million, amounting to one in every two daily papers sold. Stanley Baldwin, a prime minister of the time, famously described such proprietors as ‘aiming at power without responsibility – the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages’ (Curran and Seaton, 2009: 64).

Although newspapers remained significant channels of political communication, their primacy was supplanted in the twentieth century by broadcasting. Cinema news-reels, radio, and then television enabled communication with the mass public to take place in a new form: spoken rather than written, personal rather than abstract, and – increasingly – live rather than reported. Communication also went international, beginning in the 1920s with the development of shortwave radio, used by Britain and the Netherlands to broadcast to their empires. Nazi Germany, the United States, the Soviet Union, and other major Western states then followed. Shortwave radio continued to provide an inexpensive and easy link with the outside world for many countries through to the Cold War and beyond.

Domestically, broadcasting’s impact in Western liberal democracies was relatively benign. A small number of national television channels initially dominated the airwaves in most countries after the Second World War, providing a shared experience of national events and popular entertainment. By offering some common ground to societies which were, in these early post-war decades, still strongly divided by class and religion, these new media initially served as agents of national integration.

Even more dramatic was the impact of broadcasting on politicians themselves. A public speech to a live audience encouraged expansive words and dramatic gestures but a quieter tone was needed for transmission from the broadcasting studio direct to the living room. The task was to converse with the unseen listener and viewer, rather than to deliver a speech to a visible audience gathered together in one place.The art was to talk to the millions as though they were individuals.

President Franklin Roosevelt’s fireside chats, broadcast live by radio to the American population in the 1930s, exemplified this new approach. The impact of Roosevelt’s somewhat folksy idiom was undeniable. He talked not so much to the citizens but as a citizen and was rewarded with his country’s trust. In this way, broadcasting – and the medium of radio, specifically – transformed not only the reach, but also the style, of political communication (Barber, 1992).

Broadcasting has also made a substantial contribution to political communication in most low-income countries, albeit for different reasons. In the developing world, broadcasting (whether radio or television) has two major advantages over print media. First, it does not require physical distribution to each user; second, it is accessible to the one in five of the world’s population who cannot read.

These factors initially encouraged the spread of radio. Villagers could gather round the shared set to hear the latest news, not least on the price of local crops. Today, satellite television and mobile phones are also accessible to many of the world’s poor, expanding opportunities not only for downward communication from the elite, but also for horizontal communication between ordinary people. In Kenya, for example, internet access was expensive and slow until just a few years ago, when the government opened up the mobile phone market.This sparked a fierce war for market share among carriers, leading to a simultaneous reduction in prices and a broadening of options. Safaricom became a successful local provider, and many Kenyans now have access to M-Pesa, a mobile banking platform that allows bills to be paid and funds moved online. How this dramatic communications revolution will impact politics in Kenya, and other developing countries that follow in Kenya’s wake, remains to be seen.

Just as some lower-income countries have moved directly to mobile phones, eliminating the need for an expensive fixed-wire infrastructure, so also have they developed broadcasting networks without passing through the stage of mass circulation newspapers. The capacity of ruling politicians to reach out to poor, rural populations through these radio and television networks remains an important component of governance in hybrid and authoritarian regimes.

Social media

The rise of the internet and the growing use of social media (see Table 14.1) has brought perhaps the fastest and most widespread changes ever seen in mass communication. The internet has made copious new amounts of information available (albeit of variable quality), while social media have fundamentally changed the ways in which governments and citizens communicate, and in which citizens communicate with one another.

Social media: Interactive online platforms with designated recipients, which facilitate collective or individual communication for the exchange of user-generated content. Social media bridge mass and personal communication.

TABLE 14.1: Forms of social media

| Features | Examples | |

| Social networking | Allow people to connect with one another and to share information and ideas. | Facebook (created in 2004) is the best known, but others include LinkedIn, MySpace, Academic, and Google+. |

| Media sharing | Otherwise known as content communities. Allows users to upload pictures, videos and other media. | YouTube (created 2005), Reddit, and Pinterest. |

| Collaborative sites | Allow users to post content. | Wikipedia is the best known, created in 2001. |

| Blogs and microblogs | Allow users to share ideas and hold online conversations on matters of shared interest. | Twitter (created 2006) is the best-known microblog, although several social networking sites include microblogging options. |

The internet connects people who would not otherwise be able to communicate with one another, potentially encouraging political communication and debate across a wide variety of sectors. Political leaders and parties can communicate more often and more directly with citizens via social media, although the most active users are already politically active, and many of the posts provided are partisan. Studies find that while most people agree that the internet offers access to a wider range of views than is the case with traditional media, it has also increased the influence of more extreme views, and poses new challenges to users in separating truth from fiction (Pew Research Center, 2011).

It is also important to note that access to the internet is far from equal. Many people have no access at all (because they have no access to electricity and/or computers and/or smartphones and/or broadband services), authoritarian regimes such as China and Iran continue to censor the internet, even in wealthy countries there are still many older citizens who decline to go online, and there are many people who do not use the internet for news, or use it only in a selective manner. And access to the internet does not mean that it will necessarily be used for political ends, as shown by the case of Singapore (listed as a flawed democracy in the Democracy Index). While this affluent island state has one of the highest rates of internet penetration in the world, many of its people remain uncomfortable about using the internet to exchange political information because of the tight controls and regulations imposed by the government (Lee and Willnat, 2009). The regime also discourages research into political communication; the technology is advanced but understanding of its impact lags substantially.

As of 2015, just over half the households in the world still did not have internet access, with rates of connection ranging from 82 per cent in Europe to 60 per cent in the Americas, 39 per cent in Asia and the Pacific, and 11 per cent in Africa (see Figure 14.2). It might also be suggested that the historic Western dominance of platforms such as social media and search engines created a new form of information imperialism, even if that pre-eminence is now being countered by their Chinese equivalents (Jin, 2015).The sheer variety of opinions that are now available online might also militate against the idea of homogenization, and might actually exert the opposite effect.

FIGURE 14.2: Global internet access

Source: International Telecommunication Union (2015)

In seeking to understand the political influence of the mass media, we can use the transmission model as a guide. This distinguishes five components in any act of political communication: who says what to whom, through which medium and with what effects (see Figure 14.3). Working our way through these components, it soon becomes clear that the media are a structure within which many people live their political lives. In turn, there are four potential mechanisms of influence: reinforcement, agenda-setting, framing, and priming (Figure 14.4). Each of these has contributed to academic thinking about how we should address media impact, and together they provide a helpful repertoire in analysing the more tangible effects of the media.

Transmission model: A model that intreprets any communication as consisting of a sender sending a message through one or more channels to a receiver with potential effects.

In the 1950s, before television became pre-eminent, the reinforcement thesis – also known as the ‘minimal effects model’ – held sway (Klapper, 1960). The argument then was that party loyalties initially transmitted through the family acted as a political sunscreen protecting people from media effects. People saw what they wanted to see and remembered what they wanted to recall.

In Britain, for instance, where national newspapers were strongly partisan, many working-class people brought up in Labour households continued to read Labour papers as adults. The correlation between the partisanship of newspapers and their readers reflected self-selection by readers, rather than the propaganda impact of the press. Given strong self-selection, the most the press could do was to reinforce readers’ existing dispositions, encouraging them to stay loyal to the cause and to turn out on election day.Those effects may have been significant but they hardly justified the more extreme statements about the power of the media.

Self-selection: The biased choice of media sources made by an individual. For example, people who are already racist may choose to visit racist websites, complicating the task of estimating the impact of those sites.

The reinforcement theory is still relevant. Consider,for example, the polarized environment in some segments of the American media. The typical viewer of Fox News or reader of the Wall Street Journal is more likely to be a conservative drawn to these outlets than to be an ex-liberal converted to the right as a result of stumbling upon their news coverage.To some extent, at least, Fox News and the Wall Street Journal preach to the converted.

Alternatively, consider the internet.The web allows voters to seek out, and be reinforced by, any shade of opinion with which they already sympathize, experiencing the kind of confirmation bias discussed in Chapter 6. In the main, opponents will choose not to go there, except if they are one of the few who wish to know their enemy. Here, too, the effect of self-selection is to facilitate reinforcement but limit conversion.

FIGURE 14.3: The transmission model of political communication

FIGURE 14.4: Mechanisms of media impact

Even so, the reinforcement account is past its best as a primary perspective on media effects. In the era of the internet, we can no longer imagine the typical voter as living wholly in an information silo dominated by one political outlook. This was understood as long ago as the 1970s and 1980s, when the agenda-setting role of the media won more attention. This perspective contends that the media (and television in particular) influence what we think about, though not necessarily what we think. The media write certain items onto the agenda and, by implication, keep other issues away from the public’s gaze.Thus the influence of the media stems not only from what is said but also from what is not said (Lazarsfeld and Merton, 1948).

In an election campaign, for example, television directs our attention to major candidates and to the race for victory; by contrast, fringe candidates and the issues are often treated as secondary. Walter Lippman’s widely quoted view (1922) of the press articulated the agenda-setting perspective: ‘it is like a beam of a searchlight that moves restlessly about, bringing one episode and then another out of the darkness and into vision’. In deciding how to reduce a day’s worth of world events into the span of a 30-minute evening broadcast (including commercials), programme editors set the agenda and exert their impact, asking questions such as these:

• Will the story have a strong impact on the audience?

• Does the story involve violence? (‘If it bleeds, it leads.’)

• Is the story current and novel?

• Does the story involve well-known people?

Because news programmes often focus on the exceptional, their content is invariably an unrepresentative record of events. Policy fiascos receive more attention than policy successes; corruption is a story but integrity is a bore; a fresh story gathers more coverage than a new development of a tired theme. As a result, agenda-setting creates a warped image of the world.

But we should recognize two limitations to the agenda-setting perspective. First, editors do not select stories on a whim, but are instead highly sensitive to the potential impact of different items on audience size and appreciation, and are paid to demonstrate their news sense; if they consistently fail to do so, they lose their jobs. Hence it is naive to attribute broad agenda-setting power to editors simply because they make specific judgements about what is to appear on screen or on the front page. They too reflect the agenda.

A more nuanced view, that the media circulate rather than create opinions, is implicit in Newton’s assessment of the relationship between journalists and society (2006: 215):

Implicit in many statements about media effects on society is the idea that somehow the media are quite separate from society, firing their poison arrows from a distance. In fact, the media are part of society; journalists and editors do not arrive on Earth from Mars and Venus, they are part of society like the rest of us.

Second, the explosion of channels in the electronic era means that agenda control is no longer as strict as in the heyday of broadcast television. Even if people still search for reinforcement, they can, if they wish, follow even the most specialized political interests through some media outlet somewhere. As the media become more pluralistic, so consumers acquire the capacity to follow their noses and shape their own agendas.

The framing of a story – the way in which reports construct a narrative about an event – is a more recent attempt to understand media impact. This is a prime example of the interpretive approach to understanding politics, and reflects Plato’s observation that ‘those who tell the stories also rule society’. The journalist’s words, and the camera’s images, help to frame the story, providing a narrative which encourages a particular reaction from the viewer.

For example, are immigrants presented as a stimulus to the economy, or as a threat to society? Do media in particular European countries portray membership of the European Union critically or posi-tively? Is a criminal who has been sentenced to be executed receiving their just deserts, or a cruel and unusual punishment? As the concept of a ‘story’ suggests, the journalist must translate the event covered into an organized narrative which connects with the receiver: the shorter the report, the greater the reliance on the shared, if sometimes simplistic, presup-positions which Jamieson and Waldman (2003) term ‘consensus frames’.

Finally, the media may exert a priming effect, encouraging people to apply the criteria implicit in one story to new information and topics. For example, the more the media focuses its coverage on foreign policy, the more likely it is that voters will be primed to judge parties and candidates according to their policies in this area, and perhaps even to vote accordingly. Similarly, it is possible that coverage of racist attacks may prompt some individuals to engage in similar acts themselves, should the opportunity arise in their neighbourhood.

Recent trends in political communication

Four broad changes in political communication have been underway in higher-income countries, the combined effect of which has changed the nature of news and the choices available to consumers.Where the mass media once performed a nation-building function, their emerging impact today is to splinter the traditional national audience, as media become more commercial, fragmented, global, and interactive.

Commercialization

The commercialization of the mass media has meant the decline of public broadcasting and the rise of for-profit media treating users as consumers rather than citizens. It also allows media moguls such as Rupert Murdoch to build transnational broadcasting networks, achieving on a global scale the prominence which the newspaper barons of the nineteenth century acquired at national level.

Such developments have threatened the previously cosy links between national political parties and national broadcasters. Parties no longer called the shots and politics has had to justify its share of screen time. In an increasingly commercial environment, Tracey (1998) claims that public service broadcasting has become nothing more than ‘a corpse on leave from its grave’. In a similar way, McChesney (1999) argues that commercialization has shrunk the public space in which political issues are discussed. Channels in search of profit devote little time to serious politics, and instead concentrate on soft news, or ‘news you can use’. Certainly, profit-seeking media have no incentive to supply public goods such as an informed citizenry and high voter turnout, which were traditional concerns of public media.

Against this, commercial broadcasters reply that it is preferable to reach a mass audience with limited but stimulating political coverage than it is to offer extensive but dull political programming which, in reality, only ever reached a minority with a prior interest in public affairs (Norris, 2000). Specialist political programmes continue for political junkies but such broadcasts can no longer be foisted on unwilling audiences.

Fragmentation

With more channels and an enhanced ability to down-load and consume programmes on demand, consumers are increasingly able to watch, hear, and read what they want, when they want, and how they want. Long gone are the days when TV viewers were restricted to a few major stations or networks, and in many countries young people are now more likely to be found watching via the internet than through the traditional TV set (Murrie, 2006). Distribution by cable, satellite, the internet, and mobile devices allows viewers to receive a greater range of content, and through the use of DVRs and on-demand services, viewers can record and create programming to suit their personal tastes and schedules.

In the US, these changes are reflected in the falling audience shares for nightly news on the three major television networks (ABC, CBS, and NBC), which fell from 42 per cent of the adult population in 1980 to just 16 per cent in 2012 (Pew Research Center, 2013). Printed newspaper circulations are also plummeting throughout the developed world: by 23 per cent for dailies in the United States and by 16 per cent in Western Europe between 2006 and 2015 (World Association of Newspapers, 2015). Local and evening newspapers are closing (though some are reinventing themselves online), with some shift of printed material to generally less political free papers.

The political implications of this transition from broadcasting to ‘narrowcasting’ are substantial. Governments, parties, and commercial advertisers have more difficulty reaching a mass audience when viewers can simply choose another channel online or via their remote control. Where earlier generations would passively watch whatever appeared on their television screen, the internet is inherently user-driven, and TV is rapidly following suit; people decide for themselves where to go.

Overall exposure to politics falls as voters become harder to reach. In response, political parties are forced to adopt a greater range and sophistication of market-ing strategies, including the use of personalized but expensive contact techniques such as direct mail, email, social networks, and telephone – as skilfully exploited by Barack Obama in securing donations and volunteers for his successful election campaigns in 2008 and 2012 (Kreiss, 2012).

In this more fragmented media environment, politicians continue their migration from television news to higher-rated talk shows, blurring the distinction between the politician and the celebrity in the expanding Pollywood zone where Politics meets Hollywood (Street, 2011: ch. 9). They compete for followers on Facebook and Twitter against sports personalities, movie stars and the latest reality show. The sound bite, never unimportant, becomes even more vital as politicians learn to articulate their agenda in a short interview, or an even briefer commercial.

Just as the balance within the media industry has moved from public service to private profit, so fragmentation has shifted the emphasis in political communication from parties to voters. Politicians rode the emergence of broadcasting with considerable success in the twentieth century, but they are experiencing a rougher ride in the new millennium of fragmented media. As Mazzoleni (1987) pointed out, the balance of power between parties and the media has switched from a ‘party logic’ to a ‘media logic’.

Globalization

In 1776, the English reaction to the American Declaration of Independence took 50 days to filter back to the United States. By 2003, global viewers were watching broadcasts of the invasion of Iraq in real time. We now take for granted the almost immediate transmission of newsworthy events around the world, and even authoritarian governments find it harder than ever to isolate their populations from international developments. Even before the internet, communist states found it difficult to jam foreign radio broadcasts aimed at their people. Dis-cussing the collapse of communist states, Eberle (1990: 194–5) claimed that ‘the changes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were as much the triumph of communication as the failure of communism’.Today, China’s iron curtain of censorship can easily be circumvented by those of its people who take the trouble to access the range of overseas blogs and sites documenting the latest developments within their country.

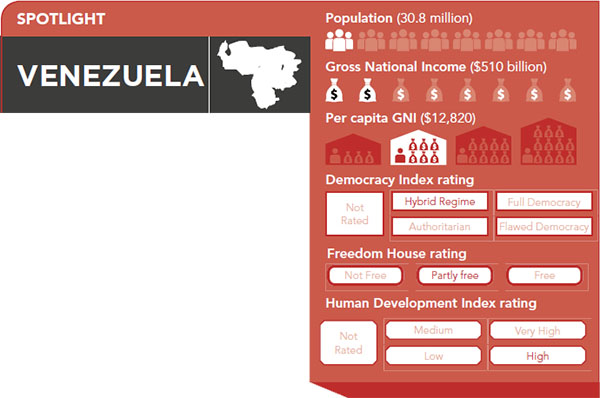

Brief Profile: Venezuela should by all rights be a Latin American success story, but a combination of political and economic difficulties has left it languishing as a hybrid regime in the Democracy Index. It is rich in oil (as well as coal, iron ore, bauxite, and other minerals) but most of its people live in poverty. The wealth of the rich, displayed through European cars, manicured suburbs, and gated communities, coexists with public squalor. Much of the failure can be attributed to Hugo Chávez, elected president in 1998 on a populist left-wing platform. His supporters, known as chavistas, claim that his policies of economic nationalization and expanded social programmes helped the poor, but his critics charge that they contributed to inflation and unemployment. He died in 2013, but his successor Nicolas Maduro has built on the Chávez legacy, continuing to distort the economy, demonize opponents and over-politicize the country’s culture.

Form of government  Federal presidential republic consisting of 23 states and a Capital District. State formed 1811, and most recent constitution adopted 1999.

Federal presidential republic consisting of 23 states and a Capital District. State formed 1811, and most recent constitution adopted 1999.

Legislature  Unicameral National Assembly of 165 members elected for fixed and renewable five-year terms.

Unicameral National Assembly of 165 members elected for fixed and renewable five-year terms.

Executive  Presidential. A president elected for an unlimited number of six-year terms, supported by a vice president and cabinet of ministers.

Presidential. A president elected for an unlimited number of six-year terms, supported by a vice president and cabinet of ministers.

Judiciary  Supreme Tribunal of Justice, with 32 members elected by the National Assembly to 12-year terms.

Supreme Tribunal of Justice, with 32 members elected by the National Assembly to 12-year terms.

Electoral system  President elected in national contest using a plurality system. National Assembly elected using mixed member proportional representation, with 60 per cent elected by single-member plurality and the balance by proportional representation.

President elected in national contest using a plurality system. National Assembly elected using mixed member proportional representation, with 60 per cent elected by single-member plurality and the balance by proportional representation.

Parties  Multi-party, with a changing roster of parties currently dominated by the United Socialist Party of Venezuela.

Multi-party, with a changing roster of parties currently dominated by the United Socialist Party of Venezuela.

Recent technological developments also facilitate underground opposition to authoritarian regimes. A small group with internet access now has the potential to draw the world’s attention to political abuses, providing source material for alert journalists. The governments of Iran and Saudi Arabia have each suffered from overseas groups in this way, though both regimes remain in place. The internet can also be used by small groups to convey less edifying messages. Both al-Qaeda and the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) have been adept at releasing online images that can be seen by anyone with access to the internet, containing propaganda, warnings, and scenes of violence intended both to encourage supporters and to scare enemies.

Political communication in Venezuela

One of the sources of Venezuela’s low ranking in indices of democracy is its poor record on media freedom. As elsewhere in Latin America, the media establishment is privately owned, but this status does not prevent chronic intervention by government. In its Freedom of the Press report, Freedom House ranks Venezuela as Not Free, and the annual reports published by Reporters Without Borders (a French-based group that promotes press freedom) charge the government with imposing pressure on independent media. The means used include a travel ban on editors and media executives, the biased adjudication of court cases involving journalists, a reduction in access to newsprint, and even death threats against journalists.

The 1999 Venezuelan constitution guarantees freedom of expression, but a 2004 law includes wording that limits expression; for example, news that could ‘incite or promote hatred’ or foment the ‘anxiety’ of Venezuelan citizens can be banned, as can media coverage considered to ‘disrespect authorities’. Regulations also allow the president to interrupt regular television programming to deliver what are known as cadenas, or live official broadcasts that can include attacks on the opposition.

The constitution also guarantees the rights of citizens to access public information, but journalists find it hard to implement these rights. The government actively bars access to information that would reflect poorly on its policies. For example, when reports broke of the possible outbreak of a mosquito-borne disease in a coastal province of Venezuela, President Maduro accused journalists who wanted to issue public warnings of practising ‘terrorism’, and issued orders for their prosecution.

The political style of former president Hugo Chávez provides a good example of a populist leader using broadcast media to influence the poorer voters who are his natural support base. Many callers to his lengthy Sunday morning broadcast show, Aló, Presidente, petitioned the president for help in securing a job or social security benefit, usually citing in the process the callousness of the preceding regime. The president created a special office to handle these requests. In Chávez’s governing style, we see how the leader of a hybrid regime can strengthen his authority through dominance of the broadcast media even against the opposition of many media professionals themselves.

Further evidence of globalization can be seen in the rise of global 24-hour news stations. These trace their roots to national all-news stations such as CNN, which began broadcasting in the United States in 1980. It was followed by CNN International in 1985, and then by BBC World (1991), Deutsche Welle from Germany (1992), Al-Jazeera from Qatar (1996), NHK World from Japan (1998), RT from Russia (2005), and France 24 (2006).These stations have not always proved profitable, and they reach only those audiences that have access to the necessary cable or satellite providers, but access to global television broadens the options for sources of political information.

Interaction

Undoubtedly the most important development in political communication has been its increased interactivity. Radio phone-ins allow ordinary people to listen to their peers discussing current issues, without mediation by a politician; blogs perform the same function in cyber-space. Messaging systems and social media are inherently interactive, allowing peer-to-peer interchanges which tend to crowd out top-down communication from politicians to voters.

The growth of interactive platforms sits uneasily alongside the reactive role expected of most voters in a representative democracy. Implicitly, a new generation schooled on interactive media is raising an important question to which politicians have yet to find an adequate answer: why should we listen to you when we have the option to interact electronically with friends of our own age who share our interests?

Interaction is a key theme in speculation about the future of political communication, with a series of scenarios developed by the Dutch Journalism Fund (Kasem et al., 2015) offering alternatives that range from dominance of the political, economic and social agenda by a handful of internet giants to a world dominated by start-ups and cooperative relationships, with government restricted to a facilitating role.The conclusion of René van Zanten, general director of the Netherlands Press Fund, is particularly interesting:

The most important thing to emerge seems to be the new and very important role that users play in the process … News is no longer the news that journalists and editors think is important. People have opinions about that.They show you the way to their world by clicking and scrolling. Media had better take that seriously and prepare not only for new ways of publishing, but also new ways of defining news.

Comparing media outlets

One danger in discussing the mass media lies in treating its various channels as uniform – as though books, films, newspapers, radio, television, and websites were identical in their partisanship and effects. True, the same content can increasingly be accessed in a variety of media – newspapers and television news can both be accessed on the internet, for example – so we should not overstate the importance of the platform. ‘Yet the medium is the message’, was the famous claim by Marshal McLuhan, who argued that the medium used influenced how the message was received (McLuhan, 1964). Even in an era of social media, there remains value in contrasting the impact of the two key channels of the mass media age: broadcast television and newspapers.

Even in its heyday, broadcast television was far from all-powerful. By the 1980s, it had certainly become the pre-eminent mass medium in all democracies, and even today remains a visual, credible, and easily digested format which reaches almost every household. Consider election campaigns. Here, the broadcasting studio has become the main site of battle.The party gladiators participate through appearing on interviews, debates, talk shows, and commercials; merely appearing on television confirms some status and recognition on candidates. Ordinary voters consume the election, if at all, through watching images, whether on television, computer screens, or smartphones.

But to say that the studio is the site of battle is one thing; to say that it determines the outcome is quite another. In fact, it is difficult to demonstrate a strong connection between television coverage of campaigns and voter responses. For instance, one frequent observation about the electoral impact of television is that it has primed voters to base their decision more on personalities, especially those of the party leaders. But compared to when? Even the claim that the broadcasting media as a whole have led voters to decide on personality neglects the importance of personalized press coverage of the parties in earlier times.

To be sure, some studies have shown a modest increase in recent decades in the focus of media coverage of election campaigns on party leaders (Mughan, 2000). However, it is far from proven that votes are increasingly cast on the basis of the personalities of leaders and even less clear that any such increase is attributable to broadcasting. Certainly, research does not support the proposition that television has rendered the images of the leaders the key influence on electoral choice.

Where television may initially have made a broader but larger contribution is in partisan dealignment: the weakening of party loyalties among voters (see Chapter 17). Because of the limited number of channels available in television’s early decades, governments required balanced and neutral treatment of politics. The result was an inoffensive style that contrasted with the more partisan coverage offered in many national newspapers. In the Netherlands, for instance, television helped to break down the separate pillars comprising Dutch society in the 1950s, providing a new common ground for citizens exposed to a single national channel: ‘Catholics discovered that Socialists were not the dan-gerous atheists they had been warned about, Liberals had to conclude that orthodox Protestants were not the bigots they were supposed to be’ (Wigbold, 1979: 201).

Despite the primacy of television, it would be wrong to discount the political impact of newspapers. Falling circulation notwithstanding, quality newspapers possess an authority springing from their longevity. In nearly all democracies, newspapers are freer with comment than is television. In an age when broadcasters still lead the provision of instant news, the more relaxed daily schedule of the press allows print columnists to offer interpretation and evaluation.

While television tells us what happened, newspapers place events in a broader context. The press helps to frame the political narrative in a way that television finds difficulty in matching. Broadcast news can only cover one story at a time whereas newspapers (in print or online) can be scanned for items of interest and can be read at the user’s convenience. Newspapers offer a luxury which television can rarely afford: space for reflection. For such reasons, quality newspapers remain the trade press of politics, read avidly by politicians themselves. In countries with a lively press tradition, newspapers retain a political significance greatly in excess of their circulation.

The way in which the mass media have developed, and been integrated into national politics, varies significantly across societies, yielding distinctive media structures. One ground-breaking study of these structures in liberal democracies (Hallin and Mancini (2004) distinguished between three different types:

Anglo-American: In this model, market mechanisms predominate and the mainly private media respond to commercial considerations. Reflecting the early achievement of mass literacy, newspaper circulation still remains relatively high. The notion of journalism as a news-gathering profession is entrenched, while the media and political worlds inhabit distinct spheres, with the former acting as a self-appointed watchdog over the latter. There are contrasts within the model, though: for example, public broadcasting and partisan national daily newspapers remain more significant in the UK than in the United States, where commerce dominates and newspapers are primarily local.

Northern European: Here, the media are seen as responsible social actors with their own contribution to make to society in general, and to political stability in particular. Newspapers and even television networks represent particular groups (e.g. religions, trade unions, political parties) but do so in an environment shaped by an interventionist state. Public broadcasting is significant and the government subsidizes private media in support of both their information and representation functions. Regulations governing media coverage, such as the right to privacy and to reply, are more extensive than in the Anglo-American structure. Journalistic professionalism is fully supported, but is tempered by an awareness of the media’s role as an actor in, and not merely an observer of, politics and society.

Southern European: In Greece, Portugal, and Spain, authoritarian regimes initially acted as a brake on the development of universal literacy, mass circulation newspapers, and a vibrant civil society. Even following the democratic transitions of the 1970s, governing parties still strongly influenced public broadcasting, while newspapers and other television stations were subject to party political influence. Television became a potent vehicle of popular entertainment but newspaper circulation remained low, with journalists seeing themselves as providing ideologically loaded commentary, rather than hard news. In these party-dominated Southern European countries, the political position of the media remains even more subdued today than in the Northern European format. Elements of this format can also be found in many non-Western countries (Hallin and Mancini, 2012).

There are several telling contrasts among the three models, for example in regard to the task of the journalist. In the Anglo-American world, journalists are news-gathering professionals who speak truth to power and engage in a combative relationship with government. In Northern Europe, journalists are less adversarial: they are expected to add greater sensitivity to the national interest, political stability, their newspaper’s outlook and the social group it serves. In Southern Europe, journalism focuses less on information and more on commentary from an ideological perspective.

The value of Hallin and Mancini’s scheme is being eroded by the contemporary media trends discussed earlier in the chapter. Within Western liberal democracies, the tendency is to a more Anglo-American approach, especially in conceptions of the journalist’s task. Still, the authors provide insight into where the media in the Western world are coming from – if less so on where they are going.

FIGURE 14.5: Media structures in liberal democracies

Source: Adapted from Hallin and Mancini (2004), who also refer to the Anglo-American structure as ‘liberal’; to the Northern European structure as ‘democratic corporatist’; and to the Southern European structure as ‘polarized pluralist’.

Media structure: Refers to historically stable patterns of media use and, in particular, to the relationships between media, the state, and the economy. Components include the extent of newspaper circulation, the scope of public broadcasting, the partisanship of the press, and internet access.

Newspapers also influence television’s agenda: a story appearing on evening TV news often begins life in the morning paper. This agenda-influencing role, it is worth noting, does not depend on a newspaper’s circulation. But when a voter sees a story covered both on television and in the press, the combined impact is likely to exceed that of either medium considered alone (Miller, 1991).

Given the rise of online newspaper readership, the dramatic decline in the circulation of printed copies is an incomplete guide to the continuing significance of newspapers. Indeed, migration to the internet has allowed the leading newspaper groups to engage a new international audience, albeit usually with little commercial benefit.

Still, the drop in both newspaper readership and viewing of television news does pose a significant threat to the quality of political communication and, hence, to the political process itself. Quality newspapers (local as well as national) and major broadcasting networks traditionally provided the means by which society gathered news about itself and the wider world. But as the advertising revenues of traditional media decline, so it becomes more difficult to maintain expensive networks of professional journalists to gather, report, and interpret the news.The danger is that the profession of journalism becomes populated with amateurs, as low-cost media look for no-cost content from readers and others.

We may live in an information-rich age, but more does not always mean better. In fact, the hard news-gathering performed by many traditional media groups, whether directly or through contracts with news agencies, compares favourably with the ‘comment-rich, fact-poor and analysis-thin’ character of blogs, many of which just react to stories generated offline (McCargo, 2012).There is some truth in the comment of Brian Wil-liams (former anchor of NBC Nightly News) that ‘these days he’s up against a guy called Vinny who hasn’t left his apartment in two years’ (quoted in Fox and Ramos, 2012: 10). Fox and Ramos go on to make the general point:

As traditional journalistic outlets shrink and blogs and other internet outlets ascend to greater levels of prominence, citizens experience increasingly unfil-tered news and information. Many blogs lack a traditional journalistic hierarchy in which an editor, who has the power to withhold publication, can demand writer accountability and accuracy.

If it is to be sustained, professional news-gathering and interpretation (whether by print or broadcast journalists) may need to be reinterpreted as a public good and provided with a public subsidy. In any event, the decline of broadcast television and newspapers in the internet age poses a major challenge to the quality of political communication.

Political communication in authoritarian states

Just as democracy thrives on a flow of information, so authoritarian rulers limit free expression; this leads to media coverage of politics which is subdued and, usually, subservient. It has also led to relatively little research on the dynamics of political communication in authoritarian systems. Far from acting as the fourth estate, casting a searchlight into the darker corners of government, journalists in authoritarian states defer to political authority. Lack of resources within the media sector limits professionalism and increases vulnerability to pressure. Official television stations and subsidized newspapers reproduce the regime’s line, while critical journalists are harassed and the entire media sector develops an instinct for self-preservation through self-censorship.

The consequence is an inadequate information flow to the top, expanding the gap between state and society, and leading ultimately to incorrect decisions. A thoughtful dictator responds to this problem by encouraging the media to expose malfeasance at the local level, thus providing a check on governance away from the centre. But there is no escape from the paradox of authoritarianism. By controlling information, rulers may secure their power in the short run, but they also reduce the quality of governance – potentially threatening their own survival over the longer term. The more developed the country, the more severe is the damage inflicted by an information deficit at the top.

How exactly do authoritarian rulers limit independent journalism? The constraints are varied and sometimes subtle. An understanding of these limitations contributes to an appreciation of authoritarian rule. In her study of sub-Saharan Africa before the wave of liberalization in the 1990s, Bourgault (1995: 180) identified a typical list of means for limiting media development and coverage:

• Declaring lengthy states of emergency which formally limit media freedom.

• Passing broad libel laws that can be selectively applied.

• Threatening the withdrawal of government advertising.

• Selectively restricting access to newsprint.

• Requiring publications and journalists to be licensed. • Taxing printing equipment at a high rate.

• Requiring a bond to be deposited with the government before new publications can launch.

As we saw in Chapter 4, authoritarian states are also most often low-income states, and limited resources undoubtedly hold back the development of the media. Restricted means stifle journalistic initiative and increase vulnerability to pressure. Sometimes impoverished journalists are reduced to publishing favourable stories (or withdrawing the threat to write critical ones) in exchange for money. The established media in authoritarian states become channels for propaganda rather than for hard political news.

Propaganda: Information used to promote a particular political cause or ideology with a view to changing public opinion.

In much of post-communist central Asia, large parts of the media remain in state hands, giving the authorities direct leverage. The state also typically retains ownership of a leading television channel. The outcome is subservience:

From Kazakhstan to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Belarus and Ukraine, the story is a dismal one: tax laws are used for financial harassment; a body of laws forbids insults of those in high places; compulsory registration of the media is common. In Azerbaijan, as in Belarus, one-man rule leaves little room for press freedom. (Foley, 1999: 45)

The justification for these restrictions is typically an overriding national requirement for social stability, nation-building, and economic development. The sub-text is that we cannot afford Western freedoms until we have caught up, and perhaps not even then. Before the Arab Spring, for instance, the Egyptian government expected that ‘the press should uphold the security of the country, promote economic development, and support approved social norms’ (Lesch, 2004: 610). A free press is presented as a recipe for squabbling and disharmony.

Even though many of these justifications are simply excuses for authoritarian government, we should not assume that the Western idea of a free press gar-ners universal appeal. Islamic states, in particular, stress the media’s role in affirming religious values and social norms. A free press is seen as an excuse for licence. The question is posed: why should we import Western ideas of freedom if the practical result is the availability of pornography? When society is viewed as the expression of an overarching moral code, whether Islamic or otherwise, the Western tradition of free speech appears alien – and even unethical.

The remaining states with a nominal communist allegiance also keep close control over the means of mass communication. In China, access to information has traditionally been provided on a need-to-know basis. The country’s rulers remain keen to limit dissenting voices, even though they do now permit ‘newspapers, maga-zines, television stations and news web sites to compete fiercely for audiences and advertising revenue’ (Shirk, 2011: 2). In 2011, the Communist Party even cancelled Super Girl, a television talent show with a peak audience of 400 million, fearing the subversive effect of allowing the audience to vote for their favourite act.

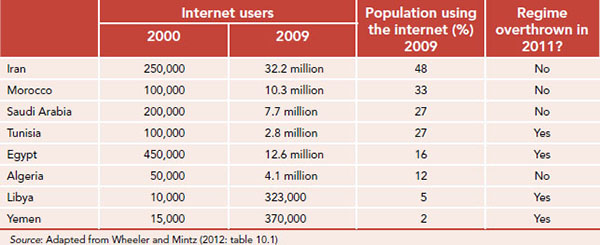

The use of online platforms for interaction among citizens has weakened political control in some authoritarian regimes, the case of the Arab Spring offering a revealing illustration. As Table 14.2 shows, internet access grew dramatically in the first decade of the new millennium in the Middle East and North Africa, allowing peer-to-peer communication among alienated urban youth, as in Iran’s Blogistan (Sreberny and Khiabany, 2010). This growth was not confined to those countries experiencing regime change in 2011 but became a significant factor in some overthrows, notably in Egypt and Tunisia.

Online facilities not only permitted rapid circulation of news about the latest protest venues, but also created a rare free space for social interaction – for example, between people of the opposite sex (Bayat, 2010). The word on the tweet proved harder to censor than the word on the street. In this way, social media created a model of a free and exciting democratic society against which authoritarian political systems in the Arab world seemed ever more ossified. Facebook became the freedom forum, leading Lynch (2011: 301) to claim boldly that ‘the long term evolution of a new kind of public sphere may matter more than immediate political outcomes’. Wheeler and Mintz (2012: 260–1) argue along similar lines when they suggest that ‘The ground for significant political change in authoritarian contexts can be readied by people using new media tools to discover and generate new spaces within which they can voice their dissent and assert their presence in pursuit of bettering their lives.’

TABLE 14.2: The internet id="pg-267-28" and the Arab Spring

Although the Chinese government is keen to promote e-commerce, internet users who search for ‘inappropriate’ topics such as democracy or Tibetan independence will find their searches blocked and their access to search engines withdrawn. The government even pays selected citizens to post pro-government messages online (Fox and Ramos, 2012: 8). Of course, sophisticated users find a way round the regime’s electronic censorship, producing a parallel communications system which may eventually prove to be politically transforma-tive, but for now the Great Firewall of China holds.

He (2009) describes political communication in China as taking place in two separate ‘discourse universes’.The first is the official universe, which occupies the public space, while the second is the private universe, which consists mainly of oral and person-to-person communication. He argues that applying Western theories of political communication to the Chinese context is difficult, because these models assume free and democratic elections. Since most political communication in China is controlled by the Communist Party, and takes the form of propaganda, a specialized field of political communication studies has less meaning there than it does in the West.

In hybrid regimes, control over the media is less extensive than in authoritarian states. The press and the internet are often left substantially alone, offering a forum for debate which perhaps offers some value, as well as danger, to the rulers. Yet the leading political force also dominates broadcast coverage, even where explicit or implicit censorship is absent.To some extent, such an emphasis reflects political reality: a viewer is naturally most interested in those who exert the greatest influence over their life.

Latin America provides a good example. In many countries on the continent, a tradition of personal and populist rule lends itself well to expression through broadcasting media which reach many poor and illit-erate people seeking salvation through ‘their’ leader. Foweraker et al. (2003: 105) describe the origins of this tradition in the twentieth century, when ‘populist leaders in Latin America made popular appeals to the people through mass media in newspapers and especially radio’.These authors comment that contemporary pop-ulism continues in the same vein, albeit now operating through television.

In Russia, pressures on the media – from powerful business people, as well as politicians – remain intense, an influence deriving from the centrality of television to political communication. As in Latin America, broadcasting is the main way of reaching a dispersed population for whom free television has greater appeal than papers for which they must pay. In a 2008 survey, 82 per cent of Russians said they watched television routinely, compared with just 22 per cent who said they were regular readers of national newspapers (Oates, 2014: 134). The television audience in Russia for nightly news programmes is substantial. In the size and interest of its audience, Russia’s television news is the equivalent of soap operas elsewhere. Particularly during elections, television showcases the achievements of the administration and its favoured candidates; opposition figures receive less, and distinctly less flat-tering, attention.

With over 100 laws governing media conduct in Russia, and the occasional journalist still found murdered by unknown assailants, self-censorship – the voice in the editor’s head which asks ‘Am I taking a risk in publishing this story?’ – remains rife. Because editors know on which side their bread is buttered, there is no need for politicians to take the political risk involved in explicit instruction. The internal censor allows the president to maintain deniability. ‘Censorship? What censorship?’ he can ask, with a smile.

By comparison with television, the internet and the press are less explicitly controlled in Russia, an important change to the all-embracing censorship of the communist era. Internet access, in particular, has allowed younger people in urban areas to express and organize opposition to the authoritarian style of President Vladimir Putin. As befits a competitive authoritarian regime, dominance of the major media does not imply complete censorship.

• How does the medium impact the political message?

• Which exerts more inûence on people’s political values: (a) the internet, (b) broadcast television, or (c) friends and family?

• To what extent do social media add to or detract from the idea of opinion reinforcement?

• Do the media shape or reêct public opinion?

• What are the likely implications of the decline of newspapers and broadcast television, and the growth of the internet, as a source of political news?

• Is the problem of propaganda notably worse in authoritarian than in democratic systems, or are the attempts to inûence public thinking simply couched di˚erently?

KEY CONCEPTS

Fourth estate

Mass media

Media structure

Political communication

Propaganda

Self-selection

Social media

Transmission model

FURTHER READING

Ekström, Mats and Andrew Tolson (eds) (2013)

Media Talk and Political Elections in Europe and America. An analysis of the links between media and elections, including chapters on the political interview, political debates, and uses of the internet to engage with voters.

Hallin, Daniel C. and Paolo Mancini (2004) Comparing Media Systems:Three Models of Media and Politics.This influential book presents an original classification of media systems.

Hallin, Daniel C. and Paolo Mancini (eds) (2012) Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World.This collection applies the classification in Comparing Media Systems:Three Models of Media and Politics to a wider range of countries.

Reinemann, Carsten (ed.) (2014) Political Communication. An edited collection of the current state

of understanding about political communication, including chapters on its role in various facets

of politics. Robertson, Alexa (2015) Media and Politics in a Globalization World. An assessment of the impact of globalization and technology on the relationship between media and politics.

Semetko, Holli A. and Margaret Scammell (eds)

(2012) The Sage Handbook of Political Communication. An edited collection that helps bring together themes in a fragmented and multidisci-plinary field.

Street, John (2011) Mass Media, Politics and Democracy, 2nd edn. A survey of the evolving relationship between mass media and politics, including chapters on media bias, media control, and the politics of journalism.