PREVIEW

Given that voters in democracies have a choice, how do they decide which party to support? This is the most intensively studied question in political science, and yet there is no agreed answer. Media coverage of election results tends to focus on often small and short-term shifts in party support, while academic studies are focused on broader and longer-term sociological and psychological questions such as social and economic change, electoral stability, and on how voters decide.

This chapter begins with a discussion of the long-term forces shaping electoral choice; specifically, party identification and trends suggesting that the ties between parties and voters are eroding. It then goes on to look at the impact on voter behaviour of social class and religion. As these older long-term pillars of electoral stability weaken, there is more room for new influences to affect voting choices. The chapter addresses three of these: political issues, the economy, and the personality of leaders.

The chapter also looks at rational choice analysis of voters and parties, a topic which gives us a case study of one of the theoretical approaches we reviewed in Chapter 5. It then discusses the more specific question of voter turnout: the declines witnessed in recent decades in many democracies, the impact of turnout on the quality of democracy, and the implications of compulsory voting. The chapter closes with a review of voters and voting in authoritarian states, and of the different ways in which they limit, manipulate, and coerce their voting publics.

CONTENTS

• Voters: an overview

• Party identification

• How voters choose

• Voter turnout

• Voters in authoritarian states

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • Party identifi cation lies at the heart of approaches to understanding voters, but there are questions about how much it applies outside its birthplace of the United States. And while partisan dealignment is an important trend, it is not always clear when it began or to what extent it is still active. |

| • The social bases of voting have weakened since the 1960s, although religion continues to play an important role in several countries. |

| • The rational choice approach offers a different way of looking at voters and parties. It raises intriguing theoretical puzzles, such as the apparent irrationality of turning out to vote. |

| • The evidence for more short-term explanations regarding voter choice – such as issue voting, the economy, and the personality of leaders – is variable. |

| • The decline in voter turnout has been important but this trend may now be weakening. Political science has generated clear fi ndings about the features of both the individual voter and the electoral system that encourage turnout. |

| • Voting in authoritarian states is less a matter of free choice (and thus of understanding voter motives) than a matter of the manipulation of choice (and thus of understanding the motives of ruling regimes). |

Voters: an overview

If elections lie at the heart of representative democracy, as we saw in the previous chapter, then voters are the lifeblood of those elections. Although the primary role of voters in a representative democracy is to decide between the choices offered by parties, the values, preferences, agendas, instincts, and understandings of voters all combine to influence what options parties place on the campaign table.The challenge is to understand how voters make up their minds, in which regard there are several different options.

Explanations can be broadly categorized into the sociological and the psychological. The former include a focus on the social and economic background of voters, such that parties of the left might have an advantage among poorer voters, the less educated, ethnic minorities, and residents of cities, while those of the right might tend to attract the support of wealthier and older voters, the better educated, and residents of the suburbs and rural areas. By contrast, psychological explanations focus on what goes on in the mind of voters, and what they think about parties, candidates, and issues. The argument here is that choices increasingly depend on dynamic factors such as changing public agendas and less on static factors such as social class.

Identification with a party has long been a key element linking these two approaches. Voters develop a long-term commitment to ‘their’ party, which in turn shapes their values, opinions, and voting choice. This psychological attachment will in turned be shaped and reinforced by the social position of voters: their family background, their peer group, and their workmates. There has been a weakening of the bonds between voters and parties, however, as social divisions weaken, education becomes more available, people have become more mobile, parties change in order to widen their appeal, and some voters become more disillusioned with politics as usual.

Increasingly, shorter-term influences have supplemented long-term influences in explaining voter behaviour: not just which party to support, but also whether to vote at all. As the impact of social class and religion declines, so voters are more likely to be influenced by the particular issues they care about most, the state of the economy, and the personalities of party leaders and candidates. Voter choice is increasingly responsive, rather than based on ‘push’ factors such as social class or religion. When it comes to the economy, for example, most voters choose less on the basis of their grasp of complex economic issues than on the basis of factors that make intuitive sense: the number of people out of work, the number of new jobs being created, changes in the cost of living, and the state of the national economy.

Voter behaviour in authoritarian regimes, meanwhile, is subject to quite different influences, driven primarily by the desire of leaders and elites to retain their hold on power using means which would not be acceptable in a democracy. In a democratic setting, voting is an autonomous endeavour; voters will have their opinions formed by multiple influences, but it is still ultimately up to them how to vote. In authoritarian regimes, voters are more likely to be influenced by having their choices restricted, whether through a limit on the number of parties running, or through manipulation and coercion, or through the use of illegal means to shape election outcomes. Even in democracies, it is important to note, ruling politicians use their privileged position to tilt the playing field in their favour; they have more access to more funds, exploit their name recognition, offer what amounts to bribes to their constituents, and structure the electoral system in their favour. That said, democratic leaders have fewer such techniques available than their authoritarian counterparts.

Party identification

The starting point for any discussion of voting in liberal democracies is The American Voter (Campbell et al., 1960). This classic book established a way of studying voters, and of thinking about how voters decide, which remains influential. Its authors obtained national sample surveys of individual voters and assessed the attitudes expressed in these polls. The task was judged to be one of objective investigation into subjective states – the behavioural approach at work. Other traditions, notably those placing the individual voter in the social and spatial context provided by family, friends, neighbours, workmates, electoral districts, and regions, lost ground.

The central concept in The American Voter was party identification, meaning a commitment to a particular party which helps voters decide which party to vote for as well as providing them with a road map through the remote world of politics. As with many other identities, party allegiance emerges in childhood and early adolescence, influenced by parents and peer groups, and then deepens as a person moves through adulthood, reinforced by commitment to the social groups to which that person belongs. Party identification is the engine of the voter’s political belief sys-tem; the best leaders are seen to come from the voter’s favoured party, and the best policies must be those the party supports.The more often voters choose the party with which they identify, the stronger their allegiance becomes.

Party identification: Long-term attachment to a particular political party, which provides a filter for understanding political events.

Party identification means not so much enthusiastic support for party as an underlying disposition to support that party. Just as regularly buying a particular brand of car short-circuits the need to make a full-scale assessment of automobile engineering with every purchase, so voting for a given party becomes a standing commitment which precludes the need to go for a political test drive at each election. For many, voting for a given party is a pragmatic, long-term brand choice. Occasionally, special circumstances might lead a Toyota buyer to choose a Ford, and a liberal to vote for a conservative party, but the homing tendency will do its job and nor-mality will be restored next time.

The distinctive features of American politics – including an entrenched two-party system, closed party primaries, and the ability to vote a party ticket for the large number of elected offices – combine to mean that the notion of party identification does not necessarily travel well. In Europe, for example, voters historically identified with class and religion, and the labour unions and churches which expressed these affiliations. Parties formed part of such networks, rather than free-standing entities. In addition, the concepts of left and right provide alternative reference points, notably in countries such as France and Italy where parties are, or have become, weak. Also, there are few signs of strong party loyalties emerging in the more fluid party systems found in the newer democracies of Eastern Europe and beyond. Finally, Europeans have a greater range of parties from which to choose, meaning more opportunity to move from one to another.

Still, the political market – as with most others – remains generally stable in most liberal democracies, with the result that a party’s share at a previous election is usually a good predictor of its support at an upcom-ing election, except in the event of major political or economic events; economic downturns in most European states in 2008–12, for example, led to a notable switch to parties of the right, and particularly to anti-establishment parties of the far right. And at the individual level, too, stability of electoral choice remains substantial. Before we can explain electoral change, we must understand this continuity. Party identification, the habit of voting for the same party, ideological labels, and group loyalties all fit the bill, even if the balance between them varies across countries and over time. At the same time, we also need to track changes in support for parties, which is where partisan dealignment enters the equation.

Partisan dealignment

The weakening of bonds between voters and their parties – otherwise known as partisan dealignment – is a clear and widespread trend in democracies. It may also be true of some emerging states, but survey research is often less sophisticated in these cases, making it difficult to find meaningful comparative data (see discussion about polling in India in Kumar and Rai, 2013). Also, parties in emerging democracies do not have as long a history as those in democracies, and the ties that bind voters to parties, as well as the explanations for how voters choose, are somewhat different.

Partisan dealignment: The weakening bonds between voters and parties, reflected both in a fall in the proportion of voters identifying with any party and a decline in the strength of allegiance among those retaining a party loyalty.

In one recent study of 19 advanced industrial democracies for which there are long-term survey data, 17 were found to have seen a decrease in the percentage of partisans, as well as a decrease in the strength of partisanship (Dalton, 2013: 183). Britain is a striking example. Between 1964–6 and 2010, the proportion of voters identifying with a party fell from 90 to 82 per cent.This may not seem very much, but over the same period the proportion of respondents with a ‘very strong’ allegiance to any party collapsed from 40 to 11 per cent.The result, say Denver et al. (2012: 71), is that strong Conservative and Labour identifiers are ‘now something of an endan-gered species’.

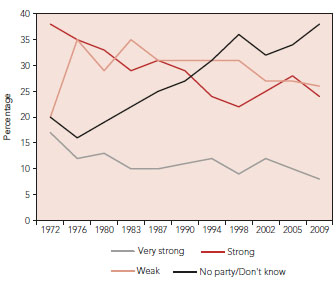

FIGURE 17.1: Partisan dealignment in Germany

Source: Dalton (2014). Data are for western Germany only.

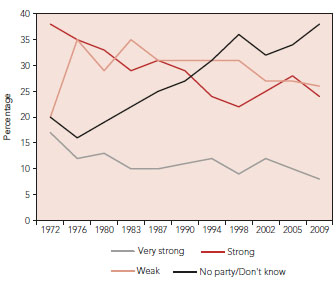

FIGURE 17.2: Partisan dealignment in Sweden

Source: Oscarsson and Hölmberg (2010: 9)

Comparable changes can be seen in Germany, with the rise of a class of independent voters who – argues Dalton (2014) – ‘are more sophisticated apartisans who are politically engaged even though they lack party ties’. As shown in Figure 17.1, the proportion of western Germans with very strong or strong party identification fell between 1972 and 2009 from 55 per cent to 32 per cent, while the proportion with weak or no party identification rose from 40 per cent to 64 per cent. There has been an even more precipitous decline in Sweden, where the proportion of people identifying with a party halved between 1968 and 2006 (see Figure 17.2).

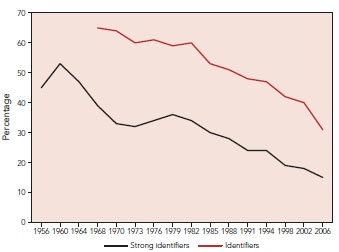

What has caused this dealignment? Although commentators within a country often concentrate on national influences, comparison across borders points to a common set of political and sociological factors (see Figure 17.3). Politically, the role of parties changed dramatically in the final third of the twentieth century, as we saw in Chapter 15.Their funding increasingly comes from the state rather than their own members; scandals and corruption tied to parties have reduced voter trust; election campaigning increasingly involves the media (the air war) as well as, or in place of, local parties (the ground war); party members have drifted towards single-issue groups; and major parties have become increasingly indistinct in their programmes and their social base. Now viewed as part of the system, rather than as expressions of social interests, parties in many countries face the same loss of trust as other state institutions.

Sociologically, the weakening of historic social divisions and the expansion of education contributed to a thinning of political identities. Dalton (2013: 187–9) suggests that what he calls ‘cognitive mobilization’ is an increasingly common way in which citizens connect themselves to politics. By this, he means that educated and politically interested voters can orient themselves to politics on their own, using the media for information and their own understanding to interpret it. The effects of dealignment have been substantial: issue voting has increased, electoral volatility has grown, turnout and active participation in campaigns has fallen, more voters wait until the last minute to decide which party to support, and new parties such as the Greens and parties on the far right have gained ground (in Europe, at least).

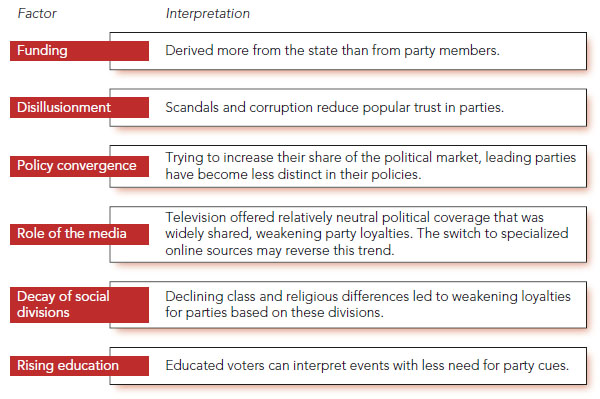

How voters choose

In trying to explain how voters make their choices, there are several options available. Longer-term influences include social class and religion, the first of which has been weakening as an indicator, while the second remains a factor in a surprising number of supposedly secular liberal democracies. Shorter-term influences – which tend to draw most media attention during election campaigns – include issue voting, the state of the economy and the personality of political leaders.

FIGURE 17.3: Causes of partisan dealignment

Social class

Since the industrial revolution, social class has influenced electoral choice in all liberal democracies: the working class has been inclined to support parties of the left, while the middle class has leaned towards parties of the right. To some extent, then, party activists campaigning in a neighbourhood can usually sense from its economic character whether it will be for or against them even before they start knocking on doors. But the evidence in recent decades points to a decline in class voting, with some (such as Knutsen, 2006) finding a particular decline of class voting in several Western European countries, such as Denmark, the Netherlands, and Britain. In general, class voting has declined the most where it was previously highest, notably in the Nordic countries.

The explanation for this change lies in a combination of political and sociological factors. At a political level, the collapse of socialism initiated a move to the centre by many left-wing parties, where traditional class themes were played down; thus Knutsen (2006) finds in a comparative analysis that ‘the political strategies of the major leftist parties showed a consistent pattern where a decisive move towards the centre was accompanied by a decline in class voting’.

But familiar sociological processes are also at work. As the service sector displaces manufacturing in advanced economies, so large unionized factories have been replaced by smaller service companies offering more diverse work to qualified staff. These skilled employees derive their power in the labour market from their individual qualifications, experience, and ability; unlike manual employees performing uniform tasks, they are not drawn to labour unions promoting collective solidarity. In this way, the foundations on which class parties were based have eroded. Comparative evidence suggests that the smaller the size of the working class in a country, and the lower the proportion of its workforce employed in industry, the greater the decline in class voting (Knutsen, 2006).

Growing income inequality in some liberal democracies, notably the United States and Britain, may represent an offsetting trend. Resentment grew against what were seen as excessive earnings by the best-paid workers in the financial sector in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008–9 (Hacker and Pierson, 2010). But individual income is not a dominant influence on how people vote, and this theme of resentment against the highest earners lacked the same resonance in other liberal democracies, such as the Nordic countries, where inequality remained less pronounced.

Religion

‘Want to know how Americans will vote next Election Day?’ asked a 2003 news story. ‘Watch what they do the weekend before … If they attend religious services regularly, they probably will vote Republican by a 2–1 margin. If they never go, they likely will vote Democratic by a 2–1 margin’ (quoted in Green, 2010b: 433). Leaving the exact figures to one side, what became known in the United States as the ‘God Gap’ illustrates the continuing relevance of religion (as indicated here by church attendance) to voting behaviour. Religion’s electoral influence remains widespread in liberal democracies, offering a contrast to the fall in class voting. Religion is not a single variable, however, and can be studied from three main angles:

• We can distinguish broadly between religious and secular voters, the former tending to vote for the right and the latter for the left.

• We can separate voters by religiosity (the importance of religion to the individual). Typically, the distinction between the religiously committed and the rest produces the largest contrasts in voting choice and also in electoral participation, with churchgoers more likely to turn out.

• We can examine the impact of specific denominations. Catholics, for example, might be inclined to vote for the right and Jewish voters for the left. Such studies can be extended to examine the electoral impact of other religions and denominations, including Islam and evangelical movements.

Comparative research has long recognized the electoral importance of religion. From a study of 16 Western democracies, Rose and Urwin (1969: 12) concluded that ‘religious divisions, not class, are the main social bases of parties in the Western world today’. Later, in examining voters rather than parties, Lijphart (1979) concluded from a study of countries where both class and religion played a political role that ‘religion tends to have a larger influence on party choice’. More recently, Esmer and Petterson (2007: 409) found that ‘religiosity still significantly shapes electoral choice in most European countries’ – noting, in particular, that ‘the devout and the pious are more likely to vote for the political right and the Christian Democrats’.The exceptions to religiosity’s continuing impact on voting are all in Northern Europe, including the United Kingdom.

Head to head, religion matters more than class, and – in a sense – class matters most when religion is weak. Thus, traditionally high levels of class voting in Scandinavia can be seen as reflecting the absence of religious conflict there once national Lutheran churches were established in the Reformation. Just as industrial change has contributed to the decline of class voting, so secularization might be expected to lead to a fall in religious voting; as societies modernize, so they naturally become more secular. And certainly, church attendance and religious belief continues to decline in many liberal democracies, not least in Europe (and increasingly among young Americans) (Esmer and Pettersson, 2007: table 25.2). Yet it is difficult to find evidence that religious voting has declined to the same extent as class voting. Some reduction is apparent but, overall, the religious base of electoral behaviour has considerable staying power.

FIGURE 17.4: Key factors explaining voter choice

Secularization: The declining space occupied by religion in political, social, and personal life.

Issue voting

Election campaigns will routinely bring up topics such as crime, defence, the environment, foreign affairs, education, public spending, and taxation. These are the ‘issues’ that are routinely discussed by parties, the media, and politicians, the implication being that they are a key element of voter choice. To what extent is this true? In reality, there are several rivers to cross before someone can be described as an issue voter. They must (1) be aware of the issue, (2) have an opinion on the issue, (3) believe that parties differ on the issue, and (4) vote for the party closest to their position.

These are considerable barriers. Studies conducted during the era of party alignment concluded that only a minority of voters passed them all. Writing of Britain, and using the metaphor of a famous English stee-plechase, Denver et al. (2012: 96) conclude that ‘when aligned voting was the norm, relatively few voters fulfilled the conditions for issue voting. As in the Grand National, large numbers fell at every fence.’ The American Voter was equally sceptical, classifying no more than one-third of the electorate as passing the first three of the four necessary conditions on each of a long list of issues.

Issue voting: The phenomenon of voters making choices at elections based on the policies that most interest them, rather than solely on the basis of sociological or demographic factors.

Having said this, more recent studies show that voting on the basis of specific policies (and also broader ideologies) has increased. As early as 1992, Franklin concluded from a study in 17 liberal democracies that the rise of issue voting matched more or less precisely a decline in voting on the basis of social position. Lewis-Beck et al. (2008: 425) reach a similar conclusion for the United States, where comparable information is available for the longest period:

The level of education within the American electorate has increased sharply since the 1950s, and this is reflected in more frequent issue voting, greater overall clarity in the structure of mass issue attitudes, and enhanced salience of ideological themes within the public’s political thinking.

But Lewis-Beck et al. go on to warn against falling too easily into the tempting narrative of issue voting supplanting party identification, and warn that the peripheral nature of politics to most Americans continues to create a ceiling to policy voting. And the nature of the political times is an understated factor: a return to the quiescence of the 1950s, when the initial studies were conducted, might lead to a reduction in issue voting, even as education levels continue to rise. Policy issues are far from irrelevant but they remain only a partial explanation for why people vote as they do.

The economy

Linking government popularity to economic performance is hardly a new idea, but it was most famously expressed by James Carville, lead strategist for Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, when he posted a list of key themes for the election at campaign headquarters, heading it with ‘The economy, stupid’.

With data on economic performance and political popularity available for most liberal democracies, this is a topic well suited to comparative analysis. The evidence suggests that the economy does matter; it affects not only government popularity, as recorded in opinion polls, but also how people behave in the polling booth. At the same time, there is a case for paraphrasing Winston Churchill’s view of democracy, and arguing that the economy is the worst explanation of election results – except for all the others (Hellwig, 2010: 200).

How exactly does the economy exert its influence? Just as it is unwise to discuss media effects without specifying a particular medium, so too should we avoid discussing economic effects without specifying a particular component. Three variables often emerging as significant are trends in real disposable personal income (i.e. after taxes and inflation), unemployment, and inflation.

The behavioural account offers one means for understanding voters. Another is offered by the rational choice approach, which assumes that voters are rational participants in the political market, and seek to maximize their utility. The most influential study by far along these lines is Anthony Downs’s An Economic Theory of Democracy, published in 1957. Downs was concerned not only with voters but also with parties, and even more with the relationship between the two.

He asks us to imagine that parties act as if they are motivated by power alone, and that voters want only a government which reflects their self-interest, as represented in their policy preferences. He also assumes that voter policy preferences can be shown on a simple left–right scale, with the left end representing full government control of the economy and the right end a completely free market. Given these assumptions, he asks, what policies should parties adopt to maximize their vote?

The crucial result, now known as the ‘median voter theorem’, is that vote-maximizing parties in a two-party system will converge at the midpoint of the distribution, and that the position of the median voter is critical. A party may start at one extreme but it will move towards the centre because there are more votes to be won there. In moving to the centre, the party remains closer to voters at its own extreme, but it also attracts middle-of-the-road voters who were previously closer to the competitor. Once parties have converged at the position of the median voter, they reach a position of equilibrium and have no incentive to change their position.

But what should we make of Downs’s assumption that voters behave rationally by voting for the party closest to their policy preferences on a single left–right scale? There are at least three objections (Ansolabehere, 2006):

• Why would self-interested voters turn out to vote at all, given the small possibility of a single ballot determining the outcome?

• Since no single ballot is likely to be decisive, why should voters go to the trouble of acquiring the information needed to cast a rational vote?

• We can question the assumption that elections are best understood as debates over policies on which voters adopt different positions. For example, voters may be more focused on a party’s competence than its policies.

Overall, Downs’s theory leads us to some interesting paradoxes. His notions of self-interest and rationality, while standard for rational choice thinking, appear to result in ignorant voters who fail to vote and in parties that adopt virtually indistinguishable policy positions. Still, the very process of comparing predictions with reality does generate puzzles whose resolution creates insight.

Personal income appears to be particularly important, as the case of the United States suggests. In the second half of the twentieth century, the growth of personal income over an electoral cycle predicted the vote share of American presidents with remarkable accuracy. One analysis suggested that ‘each percentage point increase in per capita real income [averaged across a presidential term] yielded a four per cent increase of the incumbent party’s vote share from a constant of 46 per cent’ (Hibbs, Jr, 2006: 576–7). In other words, incumbent presidents who achieve an annual average of 1 per cent growth in personal income over their first term in office should score 50 per cent of the vote; 2 per cent growth is rewarded with 54 per cent of the vote; and so on.

Studies of the impact of an incumbent government’s actual economic record dominated early research into economic voting. In recent decades, attention has shifted to how these effects operate. In particular, researchers have investigated how electoral choice varies with voters’ own assessments of how the economy has performed. After all, voters will differ in how they judge the economic record; some will see inflation where others see stable prices. Such opinions provide a channel through which the objective economy affects votes.

Studies strongly confirm the presence of an economic vote. For example, Hellwig (2010) combined the results from surveys conducted in 28 countries between 1996 and 2002 to examine the electoral effect of respondent perceptions of whether the state of the economy over the previous 12 months had improved, stayed about the same, or worsened. As Table 17.1 shows, the results were striking: voters who believed the economy had improved were twice as likely to vote for the party of the incumbent president or prime minister as voters who thought the state of the economy had worsened. Of course, those who already support the governing party are inclined to view the economy through rose-tinted glasses, exaggerating the real economic vote. Partisanship is at work here, as everywhere. Even so, the observed relationship between economic assessments and electoral choice appears to reflect more than simply the projections of the partisans (Lewis-Beck et al., 2008: table 13.8).

The actions of poor voters – whether they live in wealthy or poor countries – sets up an interesting paradox. Many studies have shown that a significant number often vote for parties that do not appear to stand for their material interests, and that instead seem to represent the interests of the wealthy. Huber and Stanig (2009) point out, for example, that large numbers of voters in wealthy democracies support parties that are opposed to the kinds of higher taxes and redistributive policies from which such voters would benefit.

Turning to voting in poorer democracies, which have been much less studied than in their wealthier counterparts, the evidence gathered to date points to a somewhat different economic incentive: the link between voting and the promise of tangible vote-specific material rewards. For example, Thachil (2014) looks at India, and specifically at the curious success of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (a party usually identified with India’s privileged upper castes) among poorer Indians. The explanation, he suggests, lies in the way the BJP has won over disadvantaged voters by privately providing them with basic social services via grassroots affiliates. This ‘outsourcing’ allows the party to continue to represent the policy interests of its privileged base, while also drawing in many votes from the poor.

This example illustrates the widespread phenomenon of vote buying, whereby rewards are offered to individual voters in return for their support at elections. It has made something of a comeback in recent decades as a consequence of democratization; in parts of the world where party labels and electoral platforms may not mean much, argues Schaffer (2007), parties and candidates try to win votes by offering tangible rewards. These may take the form of cash, of commodities (Schaffer lists everything from ciga-rettes to watches, coffins, haircuts, bags of rice, birth-day cakes, and TV sets), or of services. If impoverished voters can achieve a little more security for their family by trading their vote in this way, who is to blame them for doing so? However, the phenomenon is far from limited to poorer states or communities. Governments legally and routinely ‘buy’ the votes of other governments in meetings of international organizations (Lockwood, 2013), and almost any instance where elected representatives can point to a new factory, school or military facility that was brought to their district through their efforts might be defined as vote buying. Is there much difference between buying a voter in, say, India and buying an electoral district in, say, the United States?

TABLE 17.1: The economy and voter choice

| Perception of the economy over the past 12 months | Percentage voting for the party of the incumbent president or prime minister |

| Has got better | 46 |

| Has stayed the same | 31 |

| Has got worse | 23 |

Source: Adapted from Hellwig (2010: table 9.1), rebased to 100 per cent. Based on 28 countries, 1996–2002.

Vote buying: The process whereby parties and candidates provide material benefits to voters in return for their support at elections.

Brazil provides an interesting example of vote buying operating within the political elite. A major scandal broke there in 2005, with charges that the ruling Worker’s Party had paid a number of congressional deputies a monthly stipend in return for their support for legislation supported by the party. Known as the Mensalão (big monthly stipend) scandal, it threatened to bring down the government of President Lula da Silva (in office 2003–10). Lula himself won election to a second term, but 25 of the 38 defendants in the resulting court case were found guilty on a variety of charges. The trial came to exemplify the issue of corruption in Brazil, a problem reflected in more low-level instances of candidates paying cash to voters for their support. The problem, argues Yadav (2011: 124– 5) has worsened with the advent of stronger political parties able to exploit the Brazilian state as a source of funds.

The personality of leaders

Political leaders are obviously important to the process of reshaping political parties and their policies, but their character and personality is also important. Just how much voters can be swayed by how much they like, or do not like, the personal traits of leaders is – however – questionable.

Perhaps the most famous example of the importance of appearance, style and likeability was the first television debate involving presidential candidates in the United States, between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960. Kennedy looked relaxed and used the medium well, while Nixon looked nervous and unwell. Polls found that those who watched the TV debate thought Kennedy had won, while those who listened on radio thought Nixon had won. Later, in the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher was encouraged by her advisers to lower the tone of her voice so as to sound more authoritative. In France and the US, polls found that François Hollande and Barack Obama won their respective presidential elections in 2012 at least in part because they were seen as more likable than their competitors, Nicolas Sarkozy and Mitt Romney.

There are obvious weaknesses in using such examples to conclude that the traits of leaders have become electorally decisive.The discussion of leaders often reveals a selection bias, focusing on the characterful while forget-ting the anonymous. And, as with other factors affecting electoral choice, the net effects of a leader’s character may be limited, even if gross effects are large. For instance, as many voters may be repelled as attracted by a particular candidate’s personality, resulting in no net impact.

In the first comparative study of this subject, King (2002) attempted to judge whether the personalities of leaders determined the winning party in 52 elections held between 1960 and 2001 in Canada, France, Britain, Russia, and the United States. His conclusion was ‘No’ in 37 cases, ‘Possibly’ in 6, ‘Probably’ in 5, and ‘Yes’ in just 4 (Harold Wilson, Great Britain, 1964 and February 1974; Charles de Gaulle, France, 1965; and Pierre Trudeau, Canada, 1968). King’s general conclusion (p. 221) was that ‘most elections remain overwhelmingly political contests, and political parties would do well to choose their leaders and candidates in light of that fact’.

Much subsequent research has confirmed King’s views. Not least in parliamentary systems, the difference that leaders’ characters make is typically, but not always, shown to be modest, with only limited evidence of an increase over time. For instance, a statistical study edited by Aarts et al. (2011) and covering nine liberal democracies confirms the unimportance of the characteristics of leaders. As part of this study, Holmberg and Oscarsson (2011: 51) conclude that the greater influence of leaders on the vote ‘is simply not substantiated’. Leader traits are only a part, and often a minor part, of the factors shaping individual votes and overall election results.

Where leader traits do make a difference, which matter most? The key characteristics appear to be those directly linked to performance in office. By comparison, purely personal characteristics, such as appearance and likeability, are unimportant. Specifically, the two main factors for candidates are competence and integrity. In the United States, there is broad agreement on two core traits: ‘one, ability to do the job well, based on performance in office (incumbency) or a previous record of accomplishment; and two, a reputation for honesty’ (Lewis-Beck et al., 2008: 55–6).

Extending the analysis to Australia, Germany, and Sweden, Ohr and Oscarsson (2011: 212) reach similar conclusions, judging that ‘politically relevant and performance-related leader traits are important criteria for voters’ political judgements’. They conclude that ‘leader evaluations and their effect on the vote in the electorate are firmly based on politically “rational” considerations – be it in a presidential or in a parliamentary system’. If personal traits matter, it is because they are judged to be relevant to government performance.

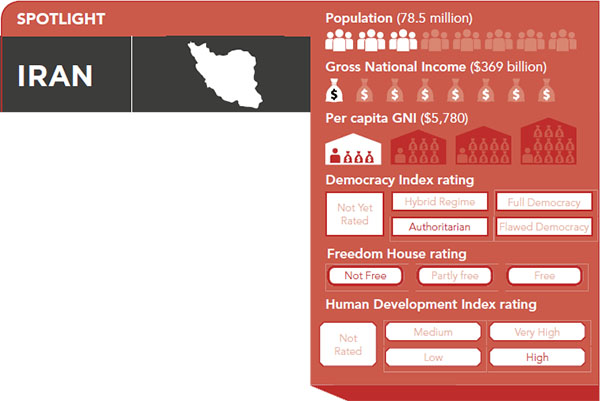

Brief Profile: Iran has long played a critical role in the Middle East, first because of the oil reserves that the British long sought, then because of the close strategic relationship between the United States and the regime of the Shah of Iran, and now because of the significance of the Islamic Republic created in the wake of the 1979 Iranian revolution. It has an elected president and legislature, but power is manipulated by an unelected Supreme Leader surrounded by competing cliques, candidates for public office are vetted, laws must be approved by an unelected clerical–juridical council, political rights are limited, and women are marginalized. It is a poor country that controls enormous oil and mineral wealth, and is socially diverse. Even if most Iranians are joined by a shared religion, they are still divided between those espousing conservative and reformist views. These differences are strongly structured by gender, generation and level of education.

Form of government  Unitary Islamic republic. Date of state formation debatable, and most recent constitution adopted 1979.

Unitary Islamic republic. Date of state formation debatable, and most recent constitution adopted 1979.

Legislature  Unicameral Majlis, with 290 members elected for renewable four-year terms.

Unicameral Majlis, with 290 members elected for renewable four-year terms.

Executive  Presidential. President elected for maximum of two consecutive four-year terms, but shares power with a Supreme Leader appointed for life by an Assembly of Experts (effectively an electoral college), who must be an expert in Islamic law, and acts as head of state with considerable executive powers.

Presidential. President elected for maximum of two consecutive four-year terms, but shares power with a Supreme Leader appointed for life by an Assembly of Experts (effectively an electoral college), who must be an expert in Islamic law, and acts as head of state with considerable executive powers.

Judiciary  Supreme Court with members appointed for five-year terms. The Iranian legal system is based on a combination of Islamic law (sharia) and civil law.

Supreme Court with members appointed for five-year terms. The Iranian legal system is based on a combination of Islamic law (sharia) and civil law.

Electoral system Single-member plurality for the legislature, simple majority for the president.

Single-member plurality for the legislature, simple majority for the president.

Parties  No-party system. Only Islamist parties can operate legally, but organizations that look like parties operate regardless. They are not formal political parties as conventionally understood, however, and instead operate as loose coalitions representing conservative and reformist positions.

No-party system. Only Islamist parties can operate legally, but organizations that look like parties operate regardless. They are not formal political parties as conventionally understood, however, and instead operate as loose coalitions representing conservative and reformist positions.

In general, leaders are higher in visibility than in impact. There is also a wider lesson here for students of electoral behaviour. As Key (1966: 7) pointed out long ago,‘voters are not fools’ and little insight is gained from treating them as such. Before dismissing voters as dupes, remember that you, too, are or may well become a voter (Goren, 2012).

Voters in Iran

Iran does not fare well on comparative democratic rankings. Since the 1979 revolution that removed the Western-backed (and authoritarian) regime of the Shah of Iran, and ushered in the era of the ayatollahs (an ayatollah is a high-ranking Shia cleric), Iran has possessed a pariah status in the eyes of most Western governments. It has been accused of repression at home, of efforts to support terrorist organizations such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, and of covert plans to build nuclear weapons.

It is all the more ironic, then, that it seems to have an active electorate faced with a significant number of circumscribed choices at the polls. The ruling clerics and the military still wield considerable power, many in the political opposition languish in jail, and elections are contested less by political parties than by religiously based factions. This does not mean, however, that many Iranians do not hanker after democratic choice, nor that they are unwilling to voice opposition to the regime and support reform-minded candidates at elections.

The 2009 and 2013 elections, for example, provided choice among candidates opting for different solutions to the country’s severe economic problems. Open campaigning included debates involving the major candidates. While there is no dependable way to measure Iranian public opinion, it was clear that many citizens – particularly younger voters suffering the most from high unemployment – were willing to express themselves. Turnout in 2013 was estimated to have exceeded 70 per cent, but charges of fraud continue to surround Iranian elections, although they are hard to verify in the absence of independent election monitoring (Addis, 2009).

With problems ranging from high population growth to unemployment, inflation, pollution, drug addiction, and poverty, Iran faces difficulties which the regime that has been in power since 1979 has intensified rather than resolved. But there is hope in the substantial desire for change among its many young, educated voters, leading Mohammadi (2006: 3) to conclude that Iran’s problems are not so much external threats as ‘the enemy within’, in the form of unresolved conflicts among major political interests.

Voter turnout

So far, this chapter has focused on the forces shaping voter choice. Equally important for political science, perhaps, is the question of voter turnout, and – more specifically –the decline in turnout in many democracies over the second half of the twentieth century.What initiated this drop? Has turnout now begun to recover? And what can be done to strengthen any recovery that is taking place? A fall in turnout is not to be equated with declining political interest since political participation may simply be evolving rather than declining (see Chapter 13). Still, turnout is important in its own right because of its effect on the outcome of an election and the relative legitimacy of the resulting government.

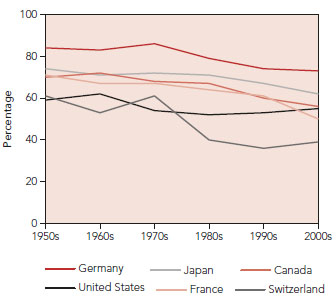

Despite rising education, turnout fell in most of the democratic world in the second half of the twentieth century. In 19 liberal democracies, it declined on average by 10 per cent between the 1950s and the 1990s (Wattenberg, 2000). Figure 17.5 reflects the trends by contrasting countries with different levels of turnout, all of which show declines over this period. To an extent, the reasons vary from one country to another, but the overall decline has formed part of a wider trend in democracies that has seen a growing distance between citizens on the one hand, and parties and government on the other. It is no coincidence that turnout has fallen as partisan dealignment has gathered pace, as party membership has fallen, and as the class and religious cleavages which once sustained party loyalties have decayed.

FIGURE 17.5: Turnout at legislative elections

Source: Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), Voter Turnout Database at www.idea.int/vt/viewdata.cfm (accessed June 2015)

In an influential analysis, Franklin (2004) linked the decline of turnout to the diminishing significance of elections. He suggested that the success of many democracies in sustaining welfare states and full employment in the post-war era resolved long-standing conflicts between capital and labour. With class conflict on the decrease, citizens had fewer incentives to vote. As Franklin (2004: 174) wrote, ‘elections in recent years may show lower turnout for the simple reason that these elections decide issues of lesser importance than elections did in the late 1950s’. As Downs would predict, when less is up for grabs, people are more likely to stay at home.

But declining satisfaction with the performance of democratic governments has also played its part.We saw in Chapter 12 how trust in government has fallen in Europe and the United States; even though mass support for democratic principles remains strong, rising cynicism about government performance has undoubtedly encouraged more people to stay away from the polls. But there are also some very practical reasons for deflated turnout: it tends to be higher in those countries where the costs or effort of voting are low and the perceived benefits are high, and patterns of turnout are also impacted by the distinctive demographic profile of voters (see Table 17.2).

As Figure 17.5 confirms, turnout continues to vary markedly between countries.There are some very practical reasons for this divergence. Overall, turnout tends to be higher in those countries where the costs or effort of voting are low and the perceived benefits are high. On the cost side, turnout is reduced when the citizen is required to take the initiative in registering as a voter, as in the United States. In most European countries, by contrast, registration is the responsibility of government. Turnout is also lower when citizens must vote in person and during a weekday. So, higher turnout can be encouraged by allowing voting at the weekend, by proxy, by mail, by electronic means, and at convenient locations such as supermarkets (Blais et al., 2003). The ability to vote in advance is also helpful; it is notable that over 30 million votes in the US presidential election of 2012 were cast before election day (United States Elections Project, 2012).

On the benefit side, the greater the impact of a single vote, the more willing voters are to incur the costs of voting. Thus, the closer the contest, the higher the turnout. Because each ballot affects the outcome, proportional representation also enhances turnout. The effect here is quite significant: turnout is about eight percentage points higher among countries using party list PR than in those using single-member plurality (IDEA, 2012).

Within countries, variations in turnout reflect the pattern found with other forms of political partici-pation; the likelihood of voting is shaped by an individual’s political resources and political interest (see Table 17.2, right column). Those most likely to vote are educated, affluent, married, middle-aged citizens with a job and a strong party loyalty, who belong to a church or a trade union, and are long-term residents of a neighbourhood. These are the people with both resources and an interest in formal politics. By contrast, abstention is most frequent among those with fewer resources and less reason to be committed to formal party politics; the archetypal non-voter is a young, poorly educated, single, unemployed man who belongs to no organizations, lacks party ties, and has recently moved to a new address.

TABLE 17.2: A recipe for higher voter turnout

| Features of the political system | Features of voters |

| Compulsory voting | Middle-aged |

| Automatic registration | Well educated |

| Voting by post and by proxy permitted | Married |

| Advance voting permitted | Higher income |

| Weekend polling | Employed |

| Election decides who governs | Home owner |

| Cohesive parties | Strong party loyalty |

| Proportional representation | Churchgoer |

| Close result anticipated | Member of a labour union |

| Small electorate | Has not changed residence recently |

| Expensive campaigns | Voted in previous elections |

| Elections for several posts held at the same time |

Sources: Endersby et al. (2006); Geys (2006); IDEA (2012)

Attempts to boost turnout must be sensitive to political realities: while increased participation may benefit the system as a whole, it will have an unequal impact on the parties within it. Conservative parties in particular will be cautious about schemes for encouraging turnout, because abstainers would probably vote disproportionately for parties of the left. There remains one other blunt but effective tool for promoting turnout: compulsory voting. We discuss this drastic solution in Focus 17.2.

Voters in authoritarian states

So far in this chapter the focus has been on the influences that shape voter choice in democracies: identification with parties, the drift away from parties, the impact of social class, religion, issues, and the economy, and the personalities of leaders. The general point is that voter choice is indeed choice: voters are faced with alternatives and bring multiple considerations to bear in deciding which party or leader to support, or even whether to vote at all.Turning to authoritarian regimes, the dynamics of voting may at first seem much simpler: voters keep their heads down and do as they are told. But the process of voting in these states presents its own particular complexities, which are far less well studied and understood than is the case with democracies. Generally speaking, understanding the motives of rulers in authoritarian states is more important than understanding the motives of voters.

FOCUS 17.2 The pros and cons of compulsory voting

In encouraging voter turnout, compulsion can be considered the nuclear option. It is used in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Singapore, Turkey and a handful of other countries, although a distinction has to be made between countries that actually enforce the law (such as Australia and Brazil) and those that do not (such as Belgium and Turkey).

The case for compulsory voting is worth making. Most citizens acknowledge obligations such as paying taxes, serving on juries, and even fighting in war; why, then, should they oppose what Hill (2002) calls the ‘light obligation and undemanding duty’ of voting at national elections? Without it, abstainers take a free ride at the expense of the efforts of the conscientious.

But the arguments against are also strong. Mandatory voting undermines the liberty which is an essential part of liberal democracy: requiring people to participate smacks of authoritarianism rather than free choice. Paying taxes and fighting in battle are duties where every little helps and where numbers matter. In all democracies, elections still attract more than enough votes to form a decision. There is no evidence that high turnout increases the quality of the political choices made, so why not continue to rely on the natural division of labour between interested voters and indifferent abstainers?

| Arguments in favour | Arguments against |

| A full turnout means the electorate is representative. | The freedom to abstain should be part of a liberal democracy. |

| Disengaged groups are drawn into the political process. | |

| The authority of the government is enhanced by a fuller turnout. | Compulsory voting gives influence to less informed and less engaged voters. |

| More voters will lead to a more informed electorate. | Abstention may reflect contentment and is not necessarily a problem. |

| People who object to voting on principle can be exempted. | In practice, turnout remains well below 100 per cent even when voting is mandatory. |

| Blank ballots can be permitted for those who oppose all candidates. | Voting (and deciding who to support) takes time. |

| Parties no longer need to devote resources to encourage their supporters to vote. | The better policy is to attract voters to the polls through their own volition. |

At the opposite end of the spectrum from democracies are no-party or one-party political systems where voters are not given much in the way of alternatives but may still be expected to endorse the regime’s candidates by turning out to vote. In communist systems, ruling parties cannot be meaningfully opposed or defeated, and official candidates are simply presented to voters for ritual endorsement. Any opinions that voters might have about the electoral process, or about party policies or pressing public issues, are not for expression in the voting booth. Undoubtedly voters do have such opinions, for politics in authoritarian states is more central to ordinary life than in democracies, and people are adept at distinguishing between national propaganda and local reality.With a ‘choice’ of one party on election day, however, such opinions are effectively suppressed. This phenomenon ties in with what we saw in Chapter 13 about mobilized participation, where the actions of voters are managed and obligatory, their involvement organized by leaders and elites in order to give the impression of support for the regime.

In today’s largely post-communist world, regimes denying all choice to voters are few and far between. More common, and more interesting, is the phenomenon of electoral authoritarianism, a term which sits on the spectrum between clear authoritarianism, on the one hand, and democracy on the other. Like so many concepts in the social sciences, its exact meaning is disputed, but Schedler (2009: 382) uses it to describe regimes that ‘play the game of multiparty elections’ while violating ‘the liberal-democratic principles of freedom and fairness so profoundly and systematically as to render elections instruments of authoritarian rule rather than “instruments of democracy”’. In other words, there are regular elections with multiple candidates, but voting is so manipulated as to effectively remove the elements of choice and meaningful competition.The result (typically known in advance) is proclaimed by the regime as signalling support for its policies. In effect, voters are co-opted, even against their will, to ‘approve’ the work of the regime. Schedler (2006) considers this to be ‘the most common form of political regime in the developing world’, but also ‘the one we know least about’.

Electoral authoritarianism: An arrangement in which a regime gives the appearance of being democratic, and offering voters choice, while maintaining its authoritarian qualities.

Algeria is an example of elections in an authoritarian setting, and offers insight into the kinds of responses prompted from voters who are often quite aware of the manipulation to which they are being subjected. In 1991, the Islamic Salvation Front seemed poised to win legislative elections, prompting the military to step in and cancel them. This intervention sparked a civil war in Algeria in which an estimated 200,000 people died. Since 1999 there have been several elections, but they are so closely managed that they have little democratic value.The 2007 election season exemplified some of the longer-term effects (Tlemcani, 2007). Superficially, voters seemed to be presented with an impressive range of choices, with two dozen parties fielding more than 12,200 candidates. But the official turnout figure was a low 35.6 per cent, a number that was cut still further by a large number of spoiled ballots, meaning that probably only about 15 per cent of Algerians cast a legitimate vote. The problem, argues Tlemcani, was not so much that Algerians were depoliticized (as the government claimed), but that they used non-participation as a last resort in expressing their opposition. There were hopes that Algeria would democratize in response to the Arab Spring, but this has not so far come to pass.

A variation on the theme of electoral authoritarianism is found in states where there is a modicum of political choice, but the meaning of that choice is undermined by the manner in which government turns a blind eye to the manipulation of voters. In the lead-up to the 2007 elections in Nigeria, for example, Human Rights Watch (2007) recalled the widespread violence, intimidation, bribery, vote rigging and corruption that had surrounded the 1999 and 2003 elections. It pointed to violent clashes between supporters of parties in the 2007 campaign that had already claimed perhaps several hundred lives. Little effort had been made by the government to investigate or prosecute the offenders, encouraging powerful politicians to recruit and arm gangs to intimidate voters. The government had also done little to ensure accurate voter registration, casting doubt on the integrity of voter lists.

This portrait of a compromised election exemplifies the problems faced by a large, divided and volatile society such as Nigeria, where voters identify above all with their ethnicity, where parties have routinely reflected ethnic divisions, and where ethnic, religious and community tensions have generated considerable violence. The International Society for Civil Liberties and the Rule of Law and Human Rights Watch estimated that between 1999 and 2010, the number of Nigerians killed in such violence ranged between 11,000 and 13,500 (quoted in Campbell, 2013: xvii). Instability from another source – the infiltration of the Boko Haram Islamist movement into north-eastern Nigeria – was the immediate reason given for the postponement by six weeks of presidential and legislative elections in Nigeria in 2015. But critics charged that the motive was politics rather than security, and was aimed at giving the incumbent president Goodluck Jonathan more time to rebuild flagging support for his campaign. In the event, he lost to his northern opponent, Muhammadu Buhari, providing the first occasion on which an incumbent president in Nigeria had lost a re-election contest.

While many countries were involved in the third wave of democratization discussed by Huntington (see Chapter 3), they varied in their historical backgrounds, ranging from former military regimes to former communist states. Few, however, had much prior experience with democracy. As a result, argues Hagopian (2007), the relationship between parties and voters in these emerging democracies is neither strong nor stable. Party identification is often weak, and electoral vola-tility (the net change in party support from one election to another) is relatively high.The original measure of such volatility was developed by Mogens Pedersen (1979), who produced an index that ranges between 0 per cent (no parties gain or lose vote share from one election to the next) and 100 per cent (no parties from the last election win any votes at the new election). As a point of reference, Pedersen’s original study of parties in Western Europe between 1948 and 1977 produced an average figure of 8.1 per cent; that is, low volatility. By contrast, later research revealed much higher levels of volatility in emerging democracies, ranging as high as 45 per cent or more in Eastern Europe and Russia (see Figure 17.6).

Electoral volatility: A measure of the degree of change in support for political parties from one election to another.

FIGURE 17.6: Comparing levels of electoral volatility

Source: Mainwaring and Torcal (2006). Figures are for elections held between 1978 and 2003.

These higher levels can be explained in part by the newness of democracy in these countries, and by the changing face of party systems: parties have not developed deep roots, must work harder to establish themselves, and face voters who are still working their way through the changing political landscape. Furthermore, as states democratize, so the factors that have most often driven party identification in democracies – such as social class and the state of the economy – change more quickly. Voters must also learn to trust and understand the new options available to them.

Measuring voter turnout in authoritarian systems is difficult, in part because of manipulated results.When dead people are listed as having voted, sometimes several times, we can be sure turnout figures are exaggerated. Generally, when official turnout figures are high, and the percentage of those votes won by the victor are high, the numbers are almost certainly fabrications. (The claim by Saddam Hussein that he won the 2002 Iraq election – actually, a referendum – with 100 per cent support on 100 per cent turnout particularly beggars belief.) Where dependable independent data are available, however, and the numbers are more realistic, we find that turnout in authoritarian states is often comparable with that in democracies. Based on polls asking people if they had voted at the most recent election, for example, de Miguel et al. (2015) found that turnout in seven Arab countries (Algeria, Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco, Lebanon, Palestine, and Yemen) ranged between 51 and 72 per cent, with an average of 61 per cent.

It would be reasonable to ask why voters make the effort to turn out in elections in authoritarian states, given the combination of their probable cynicism about the process and their distance from the interests of the elites. In their study of elections in the Arab world, de Miguel et al. (2015) reject the standard view of elections in the region as purely patronage contests. While con-ceding that patronage does play a role, they argue that voters also care about policy and use elections to express their views about the regime and its performance, particularly on the economy. ‘Positive evaluations of economic performance’, they conclude, ‘lead individuals to have more positive overall evaluations of the regime, which in turn increases the likelihood of voting.’

• What role – if any – do social class and religion play in voter choices in your country?

• If identiĉation with parties is declining, what prevents them from disappearing altogether?

• Is it irrational to vote?

• Is the role of personality underrated or overrated as an explanation for voter choices?

• Does it matter how many voters turn out at elections?

• This chapter has suggested that the motives of leaders are more important than the motives of voters in explaining voting behaviour in authoritarian states. To what extent can the same logic be applied to democracies?

KEY CONCEPTS

Electoral authoritarianism

Electoral volatility

Issue voting

Partisan dealignment

Party identification

Secularization

Vote buying

FURTHER READING

Aarts, Kees, André Blais, and Hermann Schmitt (eds) (2011) Political Leaders and Democratic Elections. Assesses the role of political leaders in voting decisions in nine democracies, suggesting that characteristics of leaders are less important than conventional wisdom imagines.

Caplan, Bryan (2007) The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why Democracies Choose Bad Policies. A study by an economist of the misconceptions and biases held by voters, and how these make them choose badly at elections.

Duch, Raymond M. and Randolph T. Stevenson (2008) The Economic Vote: How Political and Economic Institutions Condition Election Results.

An authoritative analysis of economic voting in liberal democracies.

Eijk, Cees van der and Mark Franklin (2009) Elections and Voters. A comparative textbook including chapters on voter orientations, public opinion, and voters and parties.

Franklin, Mark (2004) Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies. An influential comparative study of turnout and its decline.

Schedler, Andreas (ed.) (2006) Electoral Authoritarianism:The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. An edited collection on voting and elections in states that are neither wholly authoritarian nor wholly democratic.