PREVIEW

Democracy is both one of the easiest and one of the most difficult of concepts to understand. It is easy because democracies are abundant and familiar, and most of the readers of this book will probably live in one, while others will live in countries that aspire to become democracies. Democracy is also one of the most closely studied of all political concepts, the ease of that study made stronger by the openness of democracies and the availability of information regarding how they work. But our understanding of democracy is made more difficult by the extent to which the concept is misunderstood and misused, by the numerous and highly nuanced interpretations of what democracy means in practice, and by the many claims that are made for democracy that do not stand up to closer examination.

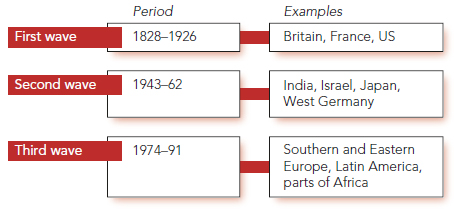

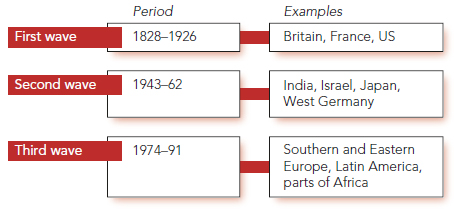

This chapter begins with a review of the key features of democracy, beginning with the Athenian idea of direct democracy (an important historical concept which has regained significance with the recent rise of e-democracy and social media), before assessing and comparing the features of representative and liberal democracy. It then looks at the links between democracy and modernization, and reviews the emergence of democracy in the three waves described by Samuel Huntington, adding speculation about the possibility of a fourth wave (but noting, also, the many problems that democracies face). It ends with a discussion about the dynamics of the transition from authoritarianism to democracy, examining the different stages in the process of democratization.

CONTENTS

• Democratic rule: an overview

• Direct democracy

• Representative democracy

• Liberal democracy

• Democracy and modernization

• Waves of democracy

• Democratization

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • About half the people in the world today live under democratic rule, even though there is still no universally agreed definition of democracy. Democracy is an ideal, not just a system of government. |

| • Studying Athenian direct democracy offers a standard of self-rule against which today’s representative (indirect) democracies are often judged. |

| • Representative democracy limits the people to electing a government, while liberal democracy goes a stage further by placing limits on government and protecting the rights of citizens. |

| • The impact of modernization (notably, economic development) on democracy raises the question of whether liberal democracy is a sensible short-term goal for low-income countries lacking democratic requisites. |

| • Democracies emerged in three main waves that resulted in most people in the world living under democratic government, but democracies continue to face many problems, not least of which is a worrying decline in levels of trust in government. |

| • A more recent approach to democracy, stimulated by recent transitions from authoritarian rule, is to study how the old order collapses and the transition takes place. |

Democratic rule: an overview

About half the people in the world today live under democratic rule (see Focus 3.1). This hopeful development reflects the dramatic changes that have taken place in the world’s political landscape since the final quarter of the twentieth century. In the space of just over a generation, the number of democracies has more than doubled, and democratic ideas have expanded beyond their core of Western Europe and its former settler colonies to embrace Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and more of Asia and Africa. For Mandelbaum (2007: xi), the changes have ‘a strong claim to being the single most important development in a century hardly lacking in momentous events and trends’.

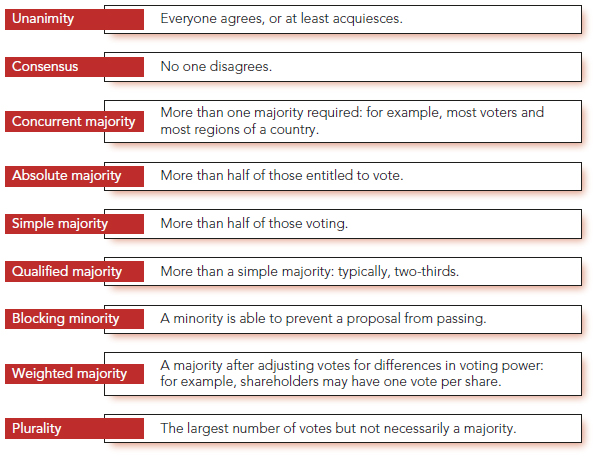

This is ironic, given that there is no fixed and agreed definition of democracy. At a minimum, it requires representative government, free elections, freedom of speech, the protection of individual rights, and government by ‘the people’. But the precise meaning of these phenomena remains open to debate, and many democracies continue to witness elitism, limits on representation, barriers to equality, and the impinge-ment of the rights of individuals and groups upon one another.

The confusion is reflected in the lack of agreement on how many democracies there are in the world. It is hard to find a government that does not claim to be democratic, because to do otherwise would be to admit that it was limiting the rights of its citizens. But some states have stronger claims to being democratic than others, and in practical terms we find democracy in its clearest and most stable form in barely three dozen states in North America, Europe, East Asia, and Australasia. But there are many other states that are undergoing a process of democratization, where political institutions and processes are developing greater stability, where individual rights are built on firmer foundations, and where the voice of the people is heard more clearly.

Democracy: A political system in which government is based on a fair and open mandate from all qualified citizens of a state.

Democratization: The process by which states build the institutions and processes needed to become stable democracies.

TABLE 3.1: Features of modern democracy

• Representative systems of government based on regular, fair, and competitive elections.

• Well-defined, stable, and predictable political institutions and processes, based on a distribution of powers and a system of political checks and balances.

• A wide variety of institutionalized forms of political participation and representation, including multiple political parties with a variety of platforms.

• Limits on the powers of government, and protection of individual rights and freedoms under the law, sustained by an independent judiciary.

• An active, effective, and protected opposition.

• A diverse and independent media establishment, subject to few political controls and free to share a wide variety of opinions.

The core principle of democracy is self-rule; the word itself comes from the Greek demokratia, meaning rule (kratos) by the people (demos). From this perspective, democracy refers not to the election of rulers by the ruled but to the denial of any separation between the two.The model democracy is a form of self-government in which all adult citizens participate in shaping collective decisions in an atmosphere of equality and deliberation, and in which state and society become one. But this is no more than an ideal, rarely found in practice except at the local level in decentralized systems of government.

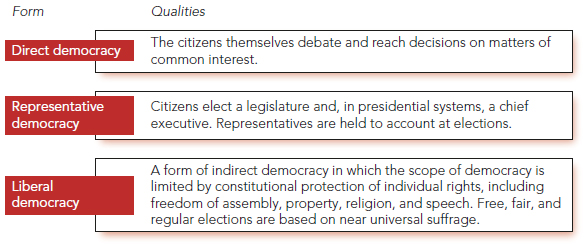

In trying to understand democracy, we should avoid the comforting assumption that it is self-evidently the best system of rule. It certainly has many advantages over dictatorship, and it can bring stability to historically divided societies provided the groups involved agree to share power through elections. But it has many imper-fections, as British political leader Winston Churchill once famously acknowledged when he argued that democracy was the worst form of government, except for all the others. In coming to grips with the concept, we can distinguish among three different strands: direct democracy, representative democracy, and liberal democracy.

Direct democracy

The purest form of democracy is the type of direct democracy that was exemplified in the government of Athens in the fifth century bce, and which continues to shape our assessments of modern liberal democracy. The Athenians believed that citizens were the primary agent for reaching collective decisions, and that direct popular involvement and open deliberation were educational in character, yielding confident, informed and committed citizens who were sensitive both to the public good and to the range of interests and opinions found even in small communities.

FOCUS 3.1 How many democracies are there?

Although the precise definition of a democracy is contested, it is generally agreed that their number has more than doubled since the 1980s, thanks mainly to two developments. First, the end of the Cold War freed several Eastern European states from the centralized political and economic control of the Soviet Union. Second, an expansion of the membership of the European Union (EU) helped build on and strengthen the democratic and capitalist credentials of those Eastern European states that are now EU members, or would like to be members.

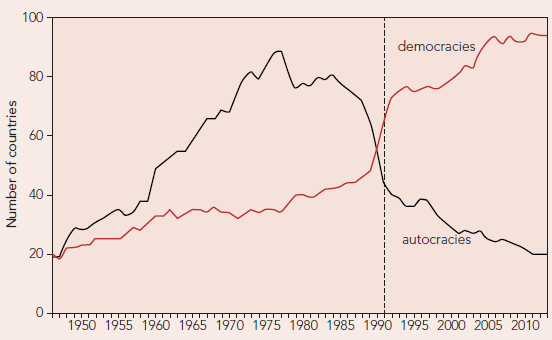

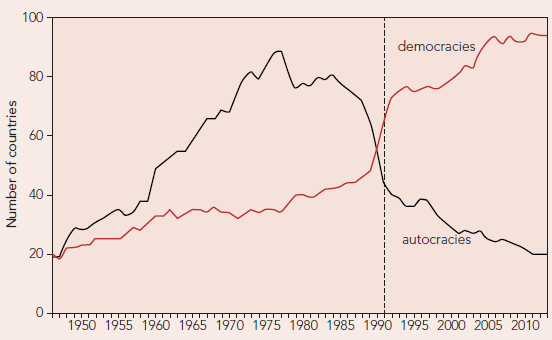

The Centre for Systemic Peace is a US-based research body that undertakes research on political violence. Its Polity IV project has gathered data for political systems dating back to 1800, the results for political change since 1945 showing how the number of democracies has grown since the end of the Cold War while the number of authoritarian regimes (specifically, autocracies) has fallen in tandem.

Note: Based on countries with a population exceeding 500,000.

Source: Adapted from Marshall and Cole (2014: 22)

And yet there is no universal agreement on how many democracies exist today, mainly because every assessment brings different standards to bear. Consider the following totals from the most recent editions of the three respective reports:

79 Economist Democracy Index 2014 (25 full democracies, 54 flawed democracies)

95 Centre for Systemic Peace

122 Freedom House 2015 (but only 88 are classified as Free)

Direct democracy: A system of government in which all members of the community take part in making the decisions that affect that community.

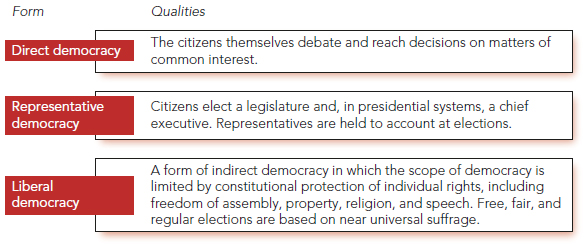

FIGURE 3.1: Forms of democracy

Between 461 and 322 bce, Athens was the leading polis (city-community) in ancient Greece. Poleis were small independent political systems, typically containing an urban core and a rural hinterland. Especially in its earlier and more radical phase, the Athenian polis operated on democratic principles summarized by Aristotle, which included appointments to most offices by lot, and brief tenures in office with no repeat terms. All male citizens could attend meetings of the Athenian Ekklesia (People’s Assembly), where they could address their peers; meetings were of citizens, not their representatives. The assembly met around 40 times a year to settle issues put before it, including recurring issues of war and peace. In Aristotle’s phrase, the assembly was ‘supreme over all causes’ (Aristotle 1962 edn: 237); it was the sovereign body, unconstrained by a formal constitution or even, in the early decades, by written laws.

Administrative functions were the responsibility of an executive council consisting of 500 citizens aged over 30, chosen by lot for a one-year period. Through the rotation of members drawn from the citizen body, the council was regarded as exemplifying community democracy: ‘all to rule over each and each in his turn over all’. Hansen (1999: 249) suggests that about one in three citizens could expect to serve on the council at some stage, an astonishing feat of self-government that has no counterpart in modern democracies. Meanwhile, juries of several hundred people – again, selected randomly from a panel of volunteers – decided the lawsuits which citizens frequently brought against those considered to have acted against the true interests of the polis. The courts functioned as an arena through which top figures (including generals) were brought to account.

The scope of Athenian democracy was wide, providing an enveloping framework within which citizens were expected to develop their true qualities. Politics was an amateur activity, to be undertaken by all citizens not just in the interest of the community at large, but also to enhance their own development. To engage in democracy was to become informed about the polis, and an educated citizenry meant a stronger whole. But there were flaws in the system:

• Because citizenship was restricted to men whose parents were citizens, most adults – including women, slaves, and foreign residents – were excluded.

• Turnout was a problem, with most citizens being absent from most assembly meetings even after the introduction of an attendance payment.

• The system was time-consuming, expensive, and over-complex, especially for such a small society.

• The principle of self-government did not always lead to decisive and coherent policy. Indeed, the lack of a permanent bureaucracy eventually contributed to a period of ineffective governance, leading to the fall of the Athenian republic after defeat in war.

Perhaps Athenian democracy was a dead end, in that it could only function on an intimate scale which limited its potential for expansion and, worse, increased its vulnerability to larger predators. Yet, the Athenian democratic experiment prospered for more than a century. It provided a settled formula for rule and enabled Athens to build a leading position in the complex politics of the Greek world. Athens proves that direct democracy is, in some conditions, an achievable goal.

Despite this, direct democracy is hard to find in modern political systems. It exists most obviously in the form either of referendums and initiatives (see Chapter 15), or of decision-making at the community level, for example in a village or a school where some decisions might be made without recourse to formal law or elected officials. To go any further, some would argue, would be to run the dangers inherent in the lack of interest and knowledge that many people display in relation to politics, and this would undermine effective governance. But create a more participatory social environment, respond its supporters, and people will be up to – and up for – the task of self-government. Society will have schooled them in, and trained them for, democratic politics, given that ‘individuals learn to participate by participating’ (Pateman, 2012: 15).

There has been some recent talk of the possibilities of electronic direct democracy, or e-democracy, through which those with an opinion about an issue can express themselves using the internet, via blogs, surveys, responses to news stories, or comments in social media. These are channels that are sometimes seen as a useful remedy to charges that representative government has become elitist, and while little research has yet been done on the political effects of social media, there are several early indications of its possibilities: it provides for the instant availability of more political information, it allows political leaders to communicate more often and more directly with voters (helping change the way that electoral campaigns are run), and it has been credited with helping encourage people to turn out in support of political demonstrations of the kind that led to the overthrow of the Egyptian government in 2011 and the fall of the Ukrainian government in 2014.

E-democracy: A form of democratic expression through which all those with an interest in a problem or an issue can express themselves via the internet or social media.

But there are several problems with e-democracy:

• The opinions expressed online are not methodically collected and assessed as they would be in a true direct democracy; the voices that are heard tend to be those that are recorded most often, and there is often a bandwagon effect reflected – for example – in the phenomenon of trending hashtags on Twitter.

• Many of those who express themselves via social media are either partisan or deliberately provocative, as reflected in the often inflammatory postings of anonymous internet ‘trolls’. The result is to skew the direction taken by debates.

• It has led to heightened concerns about privacy, perhaps feeding into the kind of mistrust of government that has led to reduced support for conventional forms of participation (see Chapter 13).

• E-democracy relies upon having access to the internet, which is a problem in poor countries, and even, sometimes, in poorer regions of wealthy countries.

• As with other media the internet can be manipulated by authoritarian regimes, resulting in the provision of selective information and interpretation.

More broadly, the internet has provided so many sources of information that consumers can quickly become overwhelmed, advancing the phenomenon of the echo chamber; whatever media they use, people will tend to use only those sources of information that fit with their values and preconceived ideas, and will be less likely to seek out a variety of sources. The result: interference with the free marketplace of ideas, the reinforcement of biases and closed minds, and the promotion of myths and a narrow interpretation of events.The internet was once described as an information super-highway, but perhaps it is better regarded as a series of gated information communities.

Echo chamber: The phenomenon by which ideas circulate inside a closed system, and users seek out only those sources of information that confirm or amplify their values.

Representative democracy

In its modern state form, and with barely a nod to ancient tradition, the democratic principle has transmuted from self-government to elected government, resulting in the phenomenon of representative democracy, an indirect form of government. To the Greeks, the idea of representation would have seemed preposterous: how can the people be said to govern themselves if a separate class of rulers exists? As late as the eighteenth century, the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau warned that ‘the moment a people gives itself representatives, it is no longer free. It ceases to exist’ (1762: 145). In interpreting representative government as elected monarchy, the German scholar Robert Michels (1911: 38) argued in a similar vein:

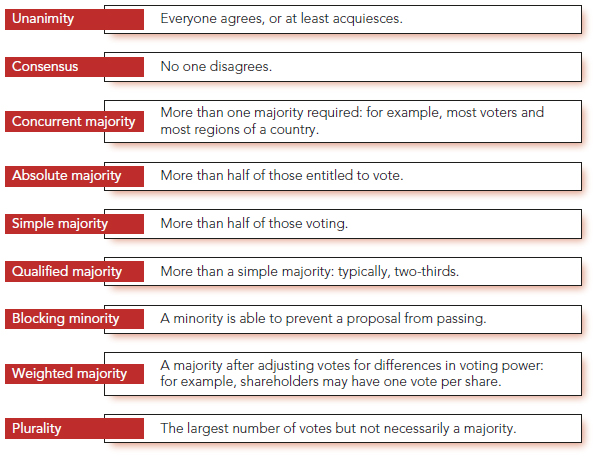

FIGURE 3.2: Degrees of democracy

Under representative government the difference between democracy and monarchy … is altogether insignificant – a difference not in substance but in form.The sovereign people elects, in place of a king, a number of kinglets!

Representative democracy: A system of government in which members of a community elect people to represent their interests and to make decisions affecting the community.

Yet, as large states emerged, so too did the requirement for a new way in which the people could shap collective decisions. Any modern version of democracy had to be compatible with large states and electorates.

One of the first authors to graft representation on t democracy was Thomas Paine, a British-born political activist who experienced both the French and the American revolutions. In his Rights of Man (1791/2: 180), Paine wrote:

The original simple democracy … is incapable of extension, not from its principle, but from the inconvenience of its form. Simple democracy was society governing itself without the aid of secondary means. By ingrafting representation upon democracy, we arrive at a system of government capable of embracing and confederating all the various interests and every extent of territory and population.

Scalability has certainly proved to be the key strength of representative institutions. In ancient Athens, the upper limit for a republic was reckoned to be the number of people who could gather together to hear a speaker. However, modern representative government allows enormous populations (such as 1.25 billion Indians and 320 million Americans) to exert some popular control over their rulers. And there is no upper limit. In theory, the entire world could become one giant system of representation. To adapt Paine’s phrase, representative government has proved to be a highly convenient form.

As ever, intellectuals have been on hand to validate this thinning of the democratic ideal. Promi-nent among them was the Austrian-born political economist Joseph Schumpeter. In Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1943), Schumpeter conceived of democracy as nothing more than party competition: ‘democracy means only that the people have the opportunity of refusing or accepting the men who are to rule them’. Schumpeter wanted to limit the contribution of ordinary voters because he doubted their political capacity:

The typical citizen drops down to a lower level of mental performance as soon as he enters the political field. He argues and analyzes in a way that he would recognize as infantile within the sphere of his real interests. He becomes a primitive again. (1943: 269)

Reflecting this jaundiced view, Schumpeter argued that elections should not even be construed as a device through which voters elect a representative to carry out their will. Rather, the point of elections is simply to produce a government. From this perspective, the voter becomes a political accessory, restricted to choosing among broad packages of policies and leaders prepared by the parties. Modern democracy is merely a way of deciding which party will decide, a system far removed from the intense, educative discussions in the Athenian assembly:

The deciding of issues by the electorate [is made] secondary to the election of the men who are to do the deciding. To put it differently, we now take the view that the role of the people is to produce a government. And we define the democratic method as that institutional arrangement for arriving at political decisions in which individuals acquire the power to decide by means of a competitive struggle for the people’s vote. (Schumpeter, 1943: 270)

Support for indirect democracy does not require Schumpeter’s scepticism about citizen quality.We might just view representation as a valuable division of labour for a specialized world. In other words, a political life is available for those who want it, while those with non-political interests can limit their attention to monitoring government and voting at elections (Schudson, 1998). In this way, elected rulers remain accountable for their decisions, albeit after the event.To make the point more explicitly: how serious would our commitment to a free society be if we sought to impose extensive political participation on people who would prefer to spend their time on other activities?

But there are many troubling questions regarding how representation works in practice.The standard means for choosing representatives is through elections, but – as we will see in Chapter 15 – there are problems associated with the ways in which elections are structured, and therefore with the ways in which citizens are represented. Votes are not always counted in an equitable fashion or equally weighted; political parties are not always given the same amount of attention by the media; money and special interests often skew the attention paid to competing sets of policy choices; and voter turnout varies by age, gender, education, race, income, and other factors. Questions are also raised about varying and often declining rates of voter turnout, and elections can also be manipulated in numerous ways, including complex or inconven-ient registration procedures, the intimidation of voters, the poor organization of polling stations, and the mis-counting of ballots.

Furthermore, as we will see in Chapter 8, there are questions about the manner in which elected officials actually represent the needs and opinions of voters. Should they act as the mouthpieces of voters (assuming they can establish what the voters want), should they use their best judgement regarding what is in the best interests of society, or should they follow the lead and guidance of their political parties? And how should they guard against being influenced excessively by interest groups, big business, social movements, or the voices of those with the means to make themselves heard most loudly?

Liberal democracy

Contemporary democracies are typically labelled liberal democracies.The addition of the adjective liberal implies embracing the notion of an elected representative government while adding a concern with limited government. Reflecting Locke’s notion of natural rights (see Chapter 2), the goal is to secure individual liberty, including freedom from unwarranted demands by the state. Liberalism seeks to ensure that even a representative government bows to the fundamental principle expressed by the English philosopher John Stuart Mill in On Liberty (1859: 68): ‘the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others’. By constraining the authority of the governing parties, the population can be defended against its rulers. At the same time, minorities can be protected from another of democracy’s inherent dangers: tyranny by the majority. Another way of describing liberal democracy is majority rule with minority rights.

Liberal democracy: A form of indirect democracy in which the scope of democracy is limited by constitutional protection of individual rights.

Limited government: Placing limits on the powers and reach of government so as to entrench the rights of citizens.

Liberalism: A belief in the supreme value of the individual, who is seen to have natural rights that exist independently of government, and who must therefore be protected from too much government.

So, in place of the boisterous debates and all-encompassing scope of the Athenian polis, liberal democracies offer governance by law, rather than by people. Under the principle of the rule of law (see Chapter 7), elected rulers and citizens alike are subject to constitutions that usually include a statement of individual rights. Should the government become overbearing, citizens can use domestic and international courts to uphold their rights. This law-governed character of liberal democracy is the basis for Zakaria’s claim (2003: 27) that ‘the Western model is best sym-bolized not by the mass plebiscite but by the impartial judge’.

Of course, all democracies must allow space for political opinion to form and to be expressed through political parties. As Beetham (2004: 65) rightly states, ‘without liberty, there can be no democracy’. But, in liberal democracy, freedom is more than a device to secure democracy; it is valued above, or certainly alongside, democracy itself. The argument is that people can best develop and express their individuality (and, hence, contribute most effectively to the common good) by taking responsibility for their own lives. By conceiving of the private sphere as the incubator of human development, we observe a sharp contrast with the Athenian notion that our true qualities can only be promoted through participation in the polis.

The protection of civil liberties is a key part of the meaning of liberal democracy. This is based on the understanding that there are certain rights and freedoms that citizens must have relative to government and that cannot be infringed by the actions of government.These include the right to liberty, security, privacy, life, equal treatment, and a fair trial, as well as freedom of speech and expression, of assembly and association, and of the press and religion. This is all well and good, but it is not always easy to define what each of these means and where the limitations fall in defining them. Even the most democratic of societies has had difficulty deciding where the rights of one group of citizens ends and those of another begin, and where the actions of government (particularly in regard to national security) restrict those of citizens.

Civil liberties: The rights that citizens have relative to government, and that should not be restricted by government.

Take the question of freedom of speech as an example; democratic societies consider it an essential part of what makes them democratic, and yet there are many ways in which it is limited in practice. There are laws against slander (spoken defamation), libel (defamation through other media), obscenity (an offence against prevalent morality), sedition (proposing insurrection against the established order), and hate speech (attack-ing a person or group on the basis of their attributes). But defining what can be considered legitimate free speech, and where such speech begins to impinge upon the rights and sensibilities of others, is not easy. Should Western society – for example – respect the fact that showing the prophet Muhammad in the form of images is offensive to Muslims, or should Muslims acknowledge that many in the West consider such a limitation an infringement on their freedom of speech?

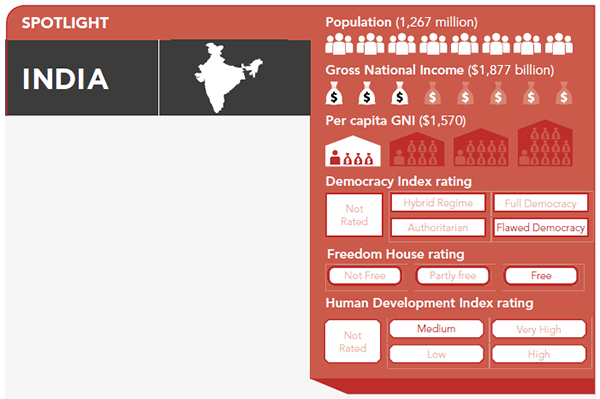

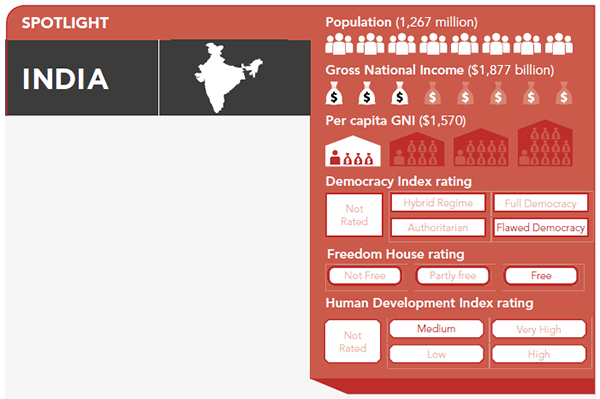

The concept of a flawed democracy contained within the Democracy Index is particularly interesting in what it suggests about the limits on rights and liberties. For example, India is often described as the world’s biggest democracy, and yet it is classified in the index as flawed. At least part of the problem stems from the generalized phenomenon of structural violence. Origi-nating in neo-Marxism, this term is used to describe intangible forms of oppression, or the ‘violence’ con-cealed within a social and political system. Hence the oppression of women is a form of structural violence perpetrated by male-dominated political systems, and extreme poverty is a form of violence perpetrated by one part of society on another. In India, structural violence can be found in the effects of poverty and caste oppression. These deep-rooted inequalities carry over to the political sphere, and impact on the way Indians relate to their political system.

FOCUS 3.2 Full democracies vs. flawed democracies

The Economist’s Democracy Index makes a distinction between what it calls full democracies and flawed democracies. The former group (consisting of 25 countries in the 2014 index) is characterized by the efficient functioning of government with an effective system of checks and balances, respect for basic political freedoms and liberties, a political culture that is conducive to the flourishing of democracy, a variety of independent media, and an independent judiciary whose decisions are enforced. For their part, flawed democracies (of which there were 54 in the 2014 index) enjoy most of these features but experience weaknesses such as problems in governance, an underdeveloped political culture, and low levels of political participation. Examples of the two types include the following:

| Full democracies | Flawed democracies |

| Australia | Brazil |

| Canada | Chile |

| Germany | France |

| Japan | Ghana |

| Netherlands | Greece |

| Norway | India |

| South Korea | Indonesia |

| Sweden | Italy |

| United Kingdom | Mexico |

| United States | South Africa |

Structural violence: A term used to describe the social economic and political oppression built into many societies.

Some democracies emphasize the liberal in liberal democracy more than others, and here we can contrast the United States and the United Kingdom. In the US, the liberal component is entrenched by design. The founding fathers wanted, above all, to forestall a dictatorship of any kind, including tyranny by the majority.To prevent any government – and, especially, elected ones – from acquiring excessive power, the constitution

set up an intricate system of checks and balances. Authority is distributed not only among federal institutions themselves (the executive, legislative, and judicial branches), but also between the federal government and the 50 states. Power is certainly dispersed; some would say dissolved.

Checks and balances: An arrangement in which government institutions are given powers that counter-balance one another, obliging them to work together in order to govern and make decisions.

Where American democracy diffuses power across institutions, British democracy emphasizes the sovereignty of Parliament. The electoral rules traditionally ensured a secure majority of seats for the leading party, which then forms the government. This ruling party retains control over its own members in the House of Commons, enabling it to ensure the passage of its bills into law. In this way, the hallowed sovereignty of Britain’s Parliament is leased to the party in office.

Brief Profile: Often described as the world’s largest democracy, India is also one of the most culturally and demographically varied countries in the world, and has the second biggest population after that of China (with which it is rapidly catching up). After centuries of British imperial control (some direct, some indirect), India became independent in 1947. While it has many political parties, it spent many decades dominated by a single party (Congress), which has recently lost much ground to the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. India has a large military and is a nuclear power, but its economy remains notably staid, with many analysts arguing that its enormous potential is held back by excessive state intervention as well as endemic corruption. It also suffers from religious and cultural divisions that have produced much communal strife, and has had difficulties addressing its widespread poverty.

Form of government  Federal parliamentary republic consisting of 25 states and seven union territories. State formed 1947, and most recent constitution adopted 1950.

Federal parliamentary republic consisting of 25 states and seven union territories. State formed 1947, and most recent constitution adopted 1950.

Legislature  Bicameral Parliament: lower Lok Sabha (House of the People, 545 members) elected for renewable five-year terms, and upper Rajya Sabha (Council of States, 250 members) with most members elected for fixed six-year terms by state legislatures.

Bicameral Parliament: lower Lok Sabha (House of the People, 545 members) elected for renewable five-year terms, and upper Rajya Sabha (Council of States, 250 members) with most members elected for fixed six-year terms by state legislatures.

Executive  Parliamentary. The prime minister selects and leads the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The president, indirectly elected for a five-year term, is head of state, formally asks a party leader to form the government, and can take emergency powers.

Parliamentary. The prime minister selects and leads the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The president, indirectly elected for a five-year term, is head of state, formally asks a party leader to form the government, and can take emergency powers.

Judiciary  Independent Supreme Court consisting of 26 judges appointed by the president following consultation. Judges must retire at age 65.

Independent Supreme Court consisting of 26 judges appointed by the president following consultation. Judges must retire at age 65.

Electoral system  Elections to the Lok Sabha are by single-member plurality. The Election Commission of India, established by the constitution, oversees national and state elections.

Elections to the Lok Sabha are by single-member plurality. The Election Commission of India, established by the constitution, oversees national and state elections.

Parties  Multi-party, with a recent tradition of coalitions. The two major parties are the Bharatiya Janata Party and the once dominant Congress Party. Regional parties are also important.

Multi-party, with a recent tradition of coalitions. The two major parties are the Bharatiya Janata Party and the once dominant Congress Party. Regional parties are also important.

Except for the government’s sense of self-restraint, the institutions that limit executive power in the United States – including a codified constitution, a separation of powers and federalism – are absent in Britain. Far more than the United States, Britain exemplifies Schumpeter’s model of democracy as an electoral competition between organized parties. ‘We are the masters now’, trumpeted a Labour MP after his party’s triumph in 1945. And his party did indeed use its power to institute substantial economic and social reforms.

But even Britain’s representative democracy has moved in a more liberal direction. The country’s judiciary has become more active and independent, stimulated in part by the influence of the European Court of Justice. Privatization has reduced the state’s direct control over the economy. Also, the electoral system is now less likely to deliver a substantial majority for a single party. But, from a comparative perspective, a winning party (or even coalition) in Britain is still rewarded with an exceptionally free hand. The contrast with the United States remains.

Democracy in India

India is the great exception to the thesis that stable liberal democracy is restricted to affluent states. In spite of enormous poverty and massive inequality, democracy is well-entrenched in India, begging the question of how it has been able to consolidate liberal democracy when most other poor post-colonial countries initially failed.

Part of the answer lies in India’s experience as a British colony. The British approach of indirect rule allowed local elites to occupy positions of authority, where they experienced a style of governance which accepted some dispersal of power and often permitted the expression of specific grievances. The resulting legacy favoured pluralistic, limited government.

More important still was the distinctive manner in which the colonial experience played out in India. Its transition to independence was more gradual, considered, and successful than elsewhere, avoiding a damaging rush to statehood. The Indian National Congress, which led the independence struggle and governed for 30 years after its achievement, was founded in 1885. Over a long period, Congress built an extensive, patronage-based organization which proved capable of governing a disparate country after independence.

In particular, Congress gained experience of elections as participation widened even under colonial rule. By 1946, before independence, 40 million people were entitled to vote in colonial elections, providing the second largest electorate in the non-communist world (Jayal, 2007: 21). These contests functioned as training grounds for democracy.

But perhaps the critical factor in India’s democratic success was the pro-democratic values of Congress’s elite. Democracy survived in India because that is what its leaders wanted. Practices associated with British democracy – such as parliamentary government, an independent judiciary, and the rule of law – were seen as worthy of emulation. So in India, as elsewhere, the consolidation of liberal democracy was fundamentally an elite project.

The quality of India’s democracy is inevitably constrained by inequalities in Indian society. Political citizenship has not guaranteed social and economic security yet such assurance is needed for democracy to deepen. Such limitations contribute to the Democracy Index’s rating of India as a flawed democracy. But the openness of the political system at least allows low status groups to express their interests. Jayal (2007: 45) sums up: ‘the singular merit of Indian democracy lies in its success in providing a space for political contestation and the opportunity for the articulation of a variety of claims’.

To conclude this section, we need to clarify the relationship between representative democracy and liberal democracy. In truth, the terms cover the same group of states and the qualifier used is largely a matter of preference. Still, the changing popularity of the two phrases does tell a story about how democracy is implicitly conceived:

• Representative democracy (or government) is the older phrase, emerging at a time when indirect democracy was establishing itself as a practical alternative to direct democracy.The phrase does not imply limits on elected authority, other than those needed for free and fair elections, and in the twentieth century tended to find particular favour with those supporting a strong role for party-based governments, such as socialists supporting public ownership of industry.

• Liberal democracy is the more recent term, acquiring greater currency in the second half of the twentieth century and continuing to grow in popularity today. In the name of individual liberty, it directs attention to the constitutional constraints on elected governments and places limits on the decision-making scope of representatives. So liberal democracy is a more natural phrase for those who favour a market economy with its limitations on the scope of government.

Democracy and modernization

Why are some countries democratic and others not? What, in other words, are the economic and social requisites of sustainable democracy? A frequent answer is that liberal democracy flourishes in modern conditions: in high-income industrial or post-industrial states with an educated population. By contrast, middle-income states are more likely to be flawed democracies, and low-income countries will tend to be authoritarian.

Modern: A term used to characterize a state with an industrial or post-industrial economy, affluence, specialized occupations, social mobility, and an urban and educated population.

Linking modernity and democracy carries important policy implications. It suggests that advocates of democracy should give priority to economic development in authoritarian states such as China, allowing political reform to emerge naturally at a later date. First get rich, then get a democracy, runs the logic. Russia tried it the other way around, and found that democracy did not take root as hoped, and that wealth drifted into the hands of the few rather than the many. But if we accept this advice, controversial policy implications will arise. Should we really follow Apter (1965) in applying the notion of ‘premature democratization’ to low-income countries? Do we want to encourage modernizing dictatorships? And if not, why not?

The political sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset (1959) provided the classic statement of the impact of modernization, suggesting that ‘the more well-to-do a [country], the greater the chances that it will sustain democracy’. Using data from the late 1950s, Lipset found strong correlations between affluence, industrialization, urbanization and education, on the one hand, and democracy, on the other. Much later, Diamond (1992: 110) commented that the relationship between affluence and democracy remained ‘one of the most powerful and stable … in the study of national development’. In an analysis of all democracies existing between 1789 and 2001, Svolik (2008: 166) concluded that ‘democracies with low levels of economic development ... are less likely to consolidate’. Boix (2011) agrees, with the qualification that the effect of affluence on democracy declines once societies have achieved developed status.

Modernization: The process of acquiring the attributes of a modern society, or one reflecting contemporary ideas, institutions, and norms.

Inevitably, there continue to be exceptions to the rule, both apparent and real. The record of the oil-rich kingdoms of the Middle East suggests that affluence, and even mass affluence, is no guarantee of democracy. But these seeming counter-examples show only that modernity consists of more than income per head; authoritarian monarchs in the Middle East rule societies that may be wealthy, but are also highly traditional. A more important exception is India, a lower-middle-income country with a consolidated, if distinctive, democracy (see Spotlight).

So, why does liberal democracy seem to be the natural way of governing modern societies? Lipset (1959) proposed several possible answers:

• Wealth softens the class struggle, producing a more equal distribution of income and turning the working class away from ‘leftist extremism’, while the presence of a large middle class tempers class conflict between rich and poor.

• Economic security raises the quality of governance by reducing incentives for corruption.

• High-income countries have more interest groups to reinforce liberal democracy.

• Education and urbanization also make a difference. Education inculcates democratic and tolerant values, while towns have always been the wellspring of democracy.

Lipset’s list, like the relationship between modernity and democracy itself, has stood the test of time. However, recent contributions offer a more systematic treatment (Boix, 2003). Vanhanen (1997: 24), for instance, suggests that a relatively equal distribution of power resources in modern societies prevents a minority from becoming politically dominant:

When the level of economic development rises, various economic resources usually become more widely distributed and the number of economic interest groups increases. Thus the underlying factor behind the positive correlation between the level of economic development and democracy is the distribution of power resources.

Modernity has been an effective incubator of liberal democracy, but we should be careful about projecting this relationship forward. Today’s world contains many more liberal democracies than it did when Lipset was writing in the 1950s, suggesting that democracy can consolidate at lower, pre-modern levels of development. That threshold may continue to decrease, delivering a world that is wholly democratic before it becomes wholly modern. Alternatively, a few authoritarian regimes, such as China, may succeed in creating modern societies without becoming democracies.

Waves of democracy

When did modern democracies emerge? As with the phases of decolonization discussed in Chapter 2, so today’s democracies emerged – argues political scientist Samuel Huntington (1991) – in a series of distinct waves of democratization (see Figure 3.3). And just as each period of decolonization deposited a particular type of state on the political shore, so too did each democratic wave differ in the character of the resulting democracies. Not everyone agrees with Huntington’s analysis (see Munck, 1994, for example, and Doorenspleet, 2000, who argues that Huntington’s distinction between democracies and authoritarian regimes was too vague), but it is an interesting point of departure.

Waves of democratization: A group of transitions from non-democratic to democratic regimes that occurs within a specified period of time and that significantly outnumbers transitions in the opposite direction during that period.

First wave

The earliest representative democracies emerged during the longest of these waves, between 1828 and 1926. During this first period, nearly 30 countries established at least minimally democratic national institutions, including Argentina, Australia, Britain, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Scandinavian countries, and the United States. However, some backsliding occurred as fledgling democracies were overthrown by fascist, communist or military dictatorships during what Huntington describes as the ‘first reverse wave’ from 1922 to 1942.

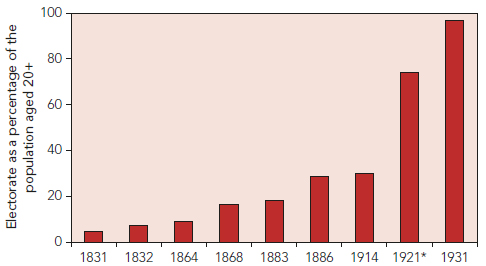

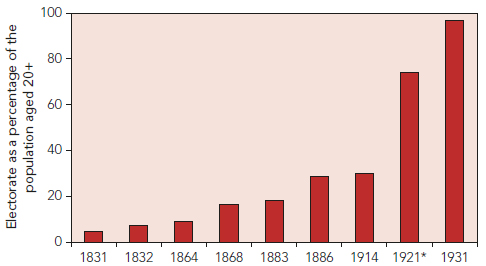

A distinctive feature of many first-wave transitions was their slow and sequential character. Political competition, traditionally operating within a privileged elite, gradually broadened as the right to vote extended to the wider population. Unhurried transitions lowered the political temperature; in the first wave, democracy was as much outcome as intention. In Britain, for example, the expansion of the vote occurred gradually (see Figure 3.4), with each step easing the fears of the propertied classes about the dangers of further reform.

In the United States, the idea that citizens could only be represented fairly by those of their own sort gained ground against the founders’ view that the republic should be led by a leisured, landed gentry.Within 50 years of independence, nearly all white men had the vote (Wood, 1993: 101), but women were not given the vote on the same terms as men until 1919, and the franchise for black Americans was not fully realized until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In that sense, America’s democratic transition was also a prolonged affair.

FIGURE 3.3: Huntington’s waves of democratization

Note: The first wave partly reversed between 1922 and 1942 (e.g. in Germany and Italy) and the second wave between 1958 and 1975 (e.g. in much of Latin America and post-colonial Africa). Many such reversals have now themselves reversed.

Source: Huntington (1991)

FIGURE 3.4: The expansion of the British electorate

Notes: The last major change was made in 1969, when the voting age was reduced from 21 to 18.

* In 1918, the vote was extended to women over 30.

Source: Adapted from Dahl (1998: figure 2)

Second wave

Huntington’s second wave of democratization began during the Second World War and continued until the 1960s. As with the first wave, some of the new democracies created at this time did not consolidate; for example, elected rulers in several Latin American states were quickly overthrown by military coups. But established democracies did emerge after 1945 from the ashes of defeated dictatorships, not just in West Germany, but also in Austria, Japan, and Italy. These post-war democracies were introduced by the victorious allies, supported by local partners. The second-wave democracies established firm roots, helped by an economic recovery which was nourished by US aid. During this second wave, democracy also consolidated in the new state of Israel and the former British dominion of India.

Political parties played a key role in the transition. First-generation democracies had emerged when parties were seen as a source of faction, rather than progress. But by the time of the second wave, parties had emerged as the leading instrument of democracy in a mass electorate. As in many more recent constitutions, Germany’s Basic Law (1949) went so far as to codify their role: ‘political parties shall take part in forming the democratic will of the people’. In several cases, though, effective competition was reduced by the emergence of a single party which dominated government for a generation or more: Congress in India, the Christian Democrats in Italy, the Liberal Democrats in Japan, and Labour in Israel. Many second-wave democracies took a generation to mature into fully competitive party systems.

Third wave

This was a product of the final quarter of the twentieth century. Its main and highly diverse elements were:

• The ending of right-wing dictatorships in Greece, Portugal, and Spain in the 1970s.

• The retreat of the generals in much of Latin America in the 1980s.

• The collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe at the end of the 1980s.

The third wave transformed the global political landscape, providing an inhospitable environment for those non-democratic regimes that survive. Even in sub-Saharan Africa, presidents subjected themselves to re-election (though rarely to defeat). With the end of the Cold War and the collapse of any realistic alternative to democracy, the European Union and the United States also became more encouraging of democratic transitions while still, of course, keeping a close eye on their own shorter-term interests.

Fourth wave, or a stalling of democracy?

While Huntington stopped with three waves, it is worth extending the logic of his arguments and looking in more detail at what has happened since 1991. Inspired by the end of the Cold War and the speed of the democratic transition in Eastern Europe, the political economist Francis Fukuyama was moved in 1989 to borrow from Hegel, Marx and others in declaring the end of history, or the final triumph of democracy:

What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history … That is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government. (Fukuyama, 1989)

End of history: The idea that a political, economic or social system has developed to such an extent that it represents the culmination of the evolutionary process.

An attractive thought, to be sure, if we think of liberal democracy in its ideal form. But it was soon clear that Fukuyama had spoken too soon, and many of today’s political conversations are not about the health or the spread of democracy but about the difficulties it faces even within those states we consider to be firmly liberal democratic. Among the concerns: social disintegration, voter alienation, the tensions between individual rights and democracy, and the manner in which competitive politics and economics can undermine the sense of community. In some cases, such as Brazil, France, India, and South Africa, the problems are sufficiently deep that the Democracy Index classifies them as flawed democracies. The more specific challenges that democracies face include the following:

• Women have less political power and opportunity than men, do not earn as much as men for equal work, and are still prevented from rising to positions of political and corporate power as easily as men.

• Racism and religious intolerance remain critical challenges, with minorities often existing on the margins of society, and denied equal access to jobs, loans, housing, or education.

• There is a large and sometimes growing income gap between the rich and the poor, and levels of unemployment and poverty often remain disturbingly high. With both comes reduced political influence, and sometimes political radicalization.

Opinion polls show declining faith in government and political institutions in many countries, reflecting less a concern with the concept of democracy than with the manner in which democracy is practised. Many see government as being dominated by elites, have less trust in their leaders, feel that government is doing a poor job of dealing with pressing economic and social problems, and – as a result – are voting in smaller numbers and switching to alternative forms of political expression and participation. As we will see in Chapter 12, trust in government has been falling in most liberal democracies.

Despite these concerns, democracy has been stable and lasting, and no country with a sustained history of liberal democracy has ever freely or deliberately opted for an alternative form of government. Neither have any liberal democracies gone to war with one another. The broad goals of the liberal democratic model – including freedom, choice, security, and wealth – are widely shared, and while the practice of liberal democracy is rarely clean or simple, as Churchill implied, the system still provides a uniquely stable and successful formula for achieving these important objectives.

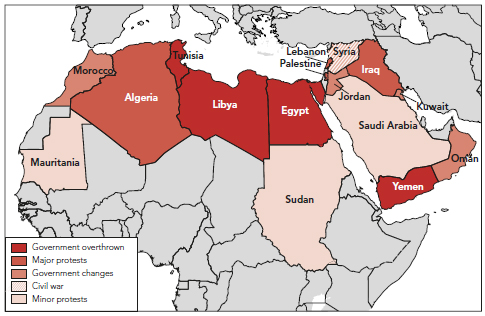

Democratization

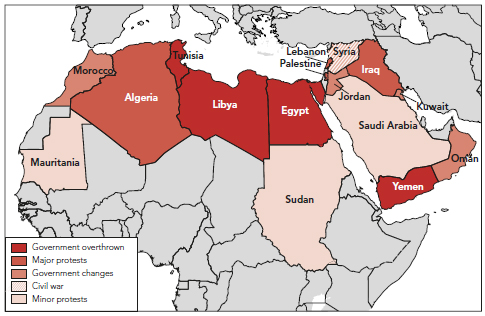

One of the most dramatic waves of political change of recent decades was the Arab Spring, a series of mass demonstrations, protests, riots, and civil wars that broke in Tunisia in late 2010, and quickly spread through much of the Arab world. Rulers were forced from power in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and Yemen, a civil war erupted in Syria, and there were mass protests or uprisings in Algeria, Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, and other countries. It was widely hoped that this remarkable protest wave would bring lasting democratic change to North Africa and the Middle East, where many of the world’s surviving authoritarian states are concentrated. However, the momentum of change had largely faded by mid-2012, with the actions of many governments in the region creating new uncertainties. Libya, for example, was in many ways in a more desperate situation by 2015 than it had been before the Arab Spring, with instability and political violence bringing death, destruction, and economic disruption. A critical point confirmed by the experience of the Arab Spring was that a transition from an authoritarian regime did not entail an immediate or even medium-term transition to liberal democracy: alternative outcomes include the replacement of one authoritarian order with another, or the emergence of a failed state.

For one point there is much supporting evidence: it is extraordinarily hard to impose democracy by force. It was a key part of US foreign policy throughout the Cold War to protect its allies from the threat of communist domination, and a goal since the end of the Cold War to bring peace to the Middle East through the promotion of democracy. But the record has not been a good one. For example, a 2003 Carnegie Endowment study (Pei, 2003) found that of 16 nation-building efforts in which the United States had engaged militarily during the twentieth century, only 4 (Germany, Japan, Grenada, and Panama) were successful in the sense that democracy remained ten years after the departure of US forces. Britain and France have shown no better average returns in their military interventions, and countries neighbouring those in which interventions have occurred have often shown more progress towards democracy than the target countries.

Why is this? De Mesquita and Downs (2004) blame US, British, and French policy, which they argue ‘has been motivated less by a desire to establish democracy or reduce human suffering than to alter some aspect of the target state’s policy’. Despite official claims, promoting democracy is rarely the most important goal. The chances of success are increased in cases where a multinational coalition takes action with the backing of the international community (or at least the bulk of the membership of the United Nations), but to assume that authoritarian regimes can be bullied or bombed into democracy is misguided, because democracy needs time to put down roots and to grow organically out of society, particularly in deeply divided states such as Afghanistan or Iraq.

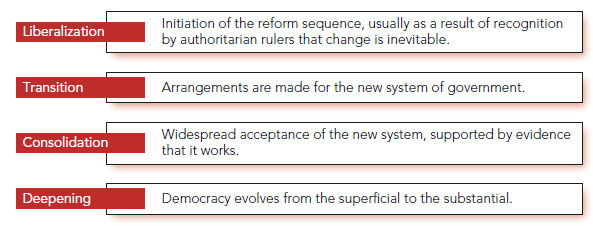

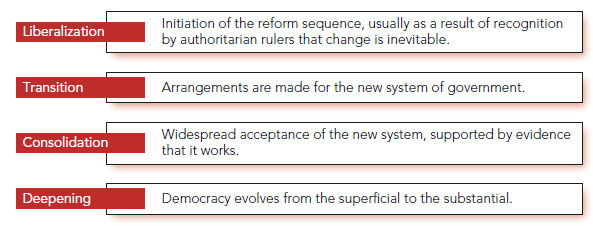

Figure 3.5 offers a model of the stages in the process of successful democratization (O’Donnell et al., 1986). However, this framework was developed in the 1980s out of research on the successful transitions in Southern Europe and Latin America, rather than the more varied outcomes from the later collapse of the Soviet Union, or the more recent experience of the Arab Spring. Even so, the model remains useful in identifying stages in a successful transition.

The first step in the process comes with the liberalization of the authoritarian regime. Much as we would like to believe in the power of public opinion, transitions are rarely initiated by mass demonstrations against a united dictatorship. Rather, democracy is typically the outcome – intended or unintended – of recognition within part of the ruling group that change is inevitable, or even desirable. As O’Donnell and Schmitter (1986: 19) assert:

There is no transition whose beginning is not the consequence – direct or indirect – of important divisions

MAP 3.1: The Arab Spring, 2011–

FIGURE 3.5: Stages of democratization

within the authoritarian regime itself, principally along the fluctuating cleavage between hardliners and softliners … In Brazil and Spain, for example, the decision to liberalize was made by high-echelon, dominant personnel in the incumbent regime in the face of weak and disorganized opposition.

So, for example, a military regime might lose a sense of purpose once the crisis that propelled it into office is resolved. In the more liberal environment that emerges, opportunities increase to express public opposition, inducing a dynamic of reform.

In the fraught and often lengthy transition to democracy, arrangements are made for the new system of government.Threats to the transition from hardliners (who may consider a military coup) and radical reformers (who may seek a full-scale revolution, rather than just a change of regime) need to be overcome. Constitutions must be written, institutions designed and elections scheduled. Negotiations frequently take the form of round-table talks between rulers and opposition, often leading to an elite settlement. During the transition, the existing rulers will look for political opportunities in the new democratic order. For example, military rulers may seek to repackage themselves as the only party capable of guaranteeing order and security. In any event, the current elite will seek to protect its future by negotiating privileges, such as exemption from prosecution. The transition is substantially complete with the instal-lation of the new arrangements, most visibly through a high turnout election which is seen as the peak moment of democratic optimism (Morlino, 2012: 85–96).

The consolidation of democracy only occurs when new institutions provide an accepted framework for political competition, or – as Przeworski (1991: 26) puts it – ‘when a particular system of institutions becomes the only game in town and when no-one can imagine acting outside the democratic institutions’. It takes time, for example, for the armed forces to accept their more limited role as a professional, rather than a political, body.

While consolidation is a matter of attitudes, its achievement is measured through action and, in particular, by the peaceful transfer of power through elections.The first time a defeated government relinquishes office, democracy’s mechanism for elite circulation is shown to be effective, contributing further to political stability. So, consolidation is the process through which democratic practices become habitual – and the habit of democracy, as any other, takes time to form (Linz and Stepan, 1996). Transition establishes a new regime but consolidation secures its continuation.

Finally, the deepening of democracy refers to the continued progress (if any) of a new democracy towards full liberal democracy. This term emerged as academic awareness grew that many third-wave transitions had stalled midway between authoritarianism and democracy, with accompanying popular disenchantment. As we saw earlier, democracy in flawed democracies is ‘superficial rather than deep and the new order consoli-dates at a low level of “democratic quality”’ (Morlino, 2012: pt III). So, the point of the term ‘deepening’ is not so much to describe a universal stage in transitions as to acknowledge that the outcome of a transition, especially in less modern countries, may be a democracy which is both consolidated and superficial.

The political changes witnessed by Mexico since the 1990s offer an example of these four stages at work. It had been governed without a break since 1929 by the centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which was able to maintain control in part because of its ability to incorporate key sectors of Mexican society, offering them rewards in return for their support. But as Mexicans became better educated, and with PRI unable to blame anyone else for the country’s growing economic problems in the 1990s, the pressures for democratic change began to grow.

Presidents had long been chosen as a result of a secretive process through which the incumbent effectively named his own successor, who was sure to win because of PRI’s grip on the electoral process.An attempt was made in 1988 to make the nomination process more democratic, a dissident group within PRI demanding greater openness in selecting presidents. When it failed, one of its leaders – Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas – broke away and ran against Carlos Salinas, the anointed PRI candidate. Heading a coalition of parties on the left, Cárdenas was officially awarded 31 per cent of the vote, although most independent estimates suggest that he probably won. Salinas was declared the winner, but with the slim-mest margin of any PRI candidate for president (50.7 per cent) and only after a lengthy delay in announcing the results, blamed on a ‘breakdown’ in the computers counting the votes (Preston and Dillon, 2004, ch. 6).

Salinas’s successor in 1994 was Ernesto Zedillo, who ordered a review of the presidential selection process, which resulted in the use of open party primaries. Meanwhile, more opposition political parties were on the rise, changes had been made to the electoral system, more seats were created in Congress, and elections were subject to closer scrutiny by foreign observers. In 1997, PRI lost its majority in the Chamber of Deputies, and in 2000 lost its majority in the Senate and – most remarkable of all – lost the presidency of Mexico to the opposition National Action Party (PAN). PAN won the presidency again in 2006, and PRI won it back in 2012, but the changes of the 1990s – sparked by the realization among PRI’s leaders that change was inevitable – have created a healthier democratic system in which three parties compete for power, albeit against a still-troubled background of widespread poverty, a bloody drug war that has been under way since 2006, and ongoing corruption.

Mexico is today listed as a flawed democracy in the Democracy Index, and as Partly Free by Freedom House. As with so many recent transitions, the Mexican case shows the importance of distinguishing between the collapse of an authoritarian system, on the one hand, and the consolidation or deepening of its more democratic successor, on the other.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• Is democracy – in practice – truly government by the people, or have other voices come to be heard more loudly?

• Does the internet allow the recreation of Athenian-style direct democracy in today’s states?

• Do you agree with Schumpeter’s doubts about the political capacity of ordinary voters? Does your answer aêct your judgement of democracy’s value?

• What conditions are needed in order for democracy to ˚ourish?

• How close are we to the end of history?

• What can we learn from the evidence that democracy can rarely be spread by force?

KEY CONCEPTS

Checks and balances

Civil liberties

Democracy

Democratization

Direct democracy

Echo chamber

E-democracy

End of history

Liberal democracy

Liberalism

Limited government

Modern

Modernization

Representative democracy

Structural violence

Waves of democratization

FURTHER READING

Alonso, Sonia, John Keane, and Wolfgang Merkel (eds) (2011) The Future of Representative Democracy. A wide-ranging collection of essays examining trends in representative democracy.

Dahl, Robert A. (1998) On Democracy. An accessible primer on democracy by one of its most influential academic proponents.

Haerpfer, Christian W., Patrick Bernhagen, Ronald F. Inglehart, and Christian Welzel (eds) (2009) Democratization. A comprehensive text, covering actors, causes, dimensions, regions and theories.

Held, David (2006) Models of Democracy, 3rd edn. A thorough introduction to democracy from classical Greece to the present.

Morlino, Leonardo (2012) Changes for Democracy: Actors, Structures, Processes. An extensive review of the academic literature on democratization, including hybrid regimes.

Rosanvallon, Pierre (2008) Counter-Democracy: Politics in an Age of Distrust. An original (if abstract) interpretation, viewing democracy as consisting in informal mechanisms through which the public can express confidence in, or mistrust of, its representatives.

Federal parliamentary republic consisting of 25 states and seven union territories. State formed 1947, and most recent constitution adopted 1950.

Federal parliamentary republic consisting of 25 states and seven union territories. State formed 1947, and most recent constitution adopted 1950.