PREVIEW

For most residents of democracies, political parties are the channel through which they most often relate to government and politics. Parties offer them competing sets of policies, encourage them to take part in the political process, and are the key determinant of who governs. It is all the more ironic, then, that while parties are so central to politics, they are often not well regarded by citizens. They are increasingly seen less as a means for engaging citizens and more as self-serving channels for the promotion of the interests of politicians; as a result, support for parties is declining as people move towards other channels for political expression. In authoritarian regimes the story is even less palatable: parties have routinely been the means through which elites manipulate public opinion, and have been both the shields and the instruments of power.

This chapter begins with a brief survey of the origins and changing roles of parties, before looking at the variety of party systems around the world, ranging from states where parties are not allowed through single-party, dominant party and two-party systems to the multi-party systems found in the majority of democracies. It reviews the quite different dynamic of parties in these different systems. It then looks at the manner in which parties are organized, and at how leaders and candidates are recruited. After reviewing the changing significance of party membership, it looks at how parties are financed, and concludes with an examination of the different roles parties play in authoritarian systems.

CONTENTS

• Political parties: an overview

• Origins and roles

• Party systems

• Party organization

• Party membership

• Party finance

• Political parties in authoritarian states

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • The key dilemma facing parties is that they are poorly rated by the public yet they remain an essential device of liberal democracy. |

| • Major political parties began as agents of society (representing a particular group or class) and have since become agents of the state (so much so that the public funding of parties is quite normal). The implications of this change are important. |

| • Understanding the role of parties involves looking at party systems, not simply individual parties. The major theme here is the decline of dominant party and two-party systems, and the rise of multi-party systems. |

| • The selection process for party leaders and candidates has been changing, but its causes, and the effects on candidate quality, are less clear. |

| • The combination of falling party membership and growing public funding has changed the base of parties. |

| • Parties in authoritarian regimes play a different role from their democratic counterparts. Rather than providing a foundation for the creation of governments, they are a means for controlling citizens, disguising the power of elites, and distributing patronage. |

Political parties: an overview

It would be hard to imagine political systems functioning without political parties, and yet their history is far shorter than most people might imagine. The nineteenth-century Russian-born political thinker Moisei Ostrogorski was one of the first to recognize their growing importance in modern politics. His study of parties in Britain and the United States was less interested, as he said, in political forms than in political forces; ‘wherever this life of parties is developed’, he argued, ‘it focuses the political feelings and the active wills of its citizens’ (1902: 7). His conclusions were fully justified: in Western Europe, mass parties were founded to battle for the votes of enlarged electorates; in communist and fascist states, ruling parties monopolized power in an attempt to reconstruct society; in the developing world, nationalist parties became the vehicle for driving colonial rulers back to their imperial homeland.

Political party: A group identified by name and ideology that fields candidates at elections in order to win public office and control government.

Parties were a key mobilizing device of the twentieth century, drawing millions of people into the national political process for the first time. They jettisoned their original image as private factions engaged in capturing, and even perverting, the public interest. Instead, they became accepted as the central representative device of liberal democracy. Reflecting this new status, they began to receive explicit mention in new constitutions, some countries even banning non-party candidates from standing for the legislature, or preventing members from switching parties once elected (Reilly, 2007). Such restrictions were judged necessary for implementing party-based elections. By the century’s end, most liberal democracies offered some public funding to support party work. Parties had become part of the system, providing functions ranging from being the very foundations of government, to aggregating interests, mobilizing voters, and recruiting candidates for office.

Therein rests the problem. No longer do parties seem to be energetic agents of society, seeking to bend the state towards their supporters’ interests. Instead, they appear to be at risk of capture by the state itself. They also often seem to be less concerned with offering voters alternatives than with promoting their own interests, and competing for power for its own sake. No longer do parties provide the only home for the politically engaged; instead, people are moving towards social movements, interest groups, and social media. Western publics still endorse the principle of democracy, but they seem to be increasingly disillusioned with achieving it through competing political parties. With many parties now seen as self-serving and corrupt, Mair (2008: 230) could speculate, in contrast to Ostrogorski, that parties are in danger of ceasing to be a political driving force.

In authoritarian states, parties tend to be either non-existent (in a few cases) or else one official party dominates. The notion of competitive parties does not fit with the notion of centralized control, and parties are not so much the representatives of groups or interests as tools by which authoritarian leaders can exert power. Excepting the enormous power of ruling communist parties, they tend to be weak, lacking autonomy from the national leader, and reinforcing elite control of society. In countries that are poor and ethnically divided, parties typically lack the ideological contrasts that provided a base of party systems in most liberal democracies.

Origins and roles

Political parties are neither as old nor as central to government as we might suppose.They seem to be the lifeblood of democratic politics, and yet governments and states have long been wary of their potentially harmful impact on national unity, which is one reason why parties – unlike the formal institutions of government – went unmentioned in early constitutions. In examining party origins, we can distinguish between two types: cadre parties that had their origins in legislatures, and mass parties that were created to win legislative representation for a particular social group, such as the working class.

Cadre (or elite) parties were formed by members within a legislature joining together around common concerns and fighting campaigns in an enlarged electorate. The earliest nineteenth-century parties were of this type; they include the conservative parties of Britain, Canada, and Scandinavia, and the first American parties (the Federalists and the Jeffersonians). Cadre parties are sometimes known as ‘caucus’ parties, the caucus denot-ing a closed meeting of the members of a party in a legislature. Such parties remain heavily committed to their leader’s authority, with ordinary members playing a supporting role.

By contrast, mass parties – which emerged later – originated outside legislatures, in social groups seeking representation as a way of achieving their policy objectives.The working-class socialist parties that spread across Western Europe around the turn of the twentieth century epitomized these externally created parties. Mass socialist parties exerted tremendous influence on European party systems in the twentieth century, stimulating many cadre parties to copy their extra-parliamentary organization. Mass parties acquired an enormous membership organized in local branches, and – unlike cadre parties – tried to keep their representatives on a tight rein. They played an important role in education and political socialization, funding education, organizing workshops, and running party newspapers, all designed to tie their members closer to their party.

As cadre and mass parties matured, so they tended to evolve into catch-all parties (Kirchheimer, 1966). These respond to a mobilized political system in which electoral communication takes place through mass media, bypassing the membership. Such parties seek to govern in the national interest, rather than as representatives of a social group, the reality being that ‘a party large enough to get a majority has to be so catch-all that it cannot have a unique ideological program’ (Kirchheimer, quoted in Krouwel, 2003: 29). Catch-all parties seek electoral support wherever they can find it, their purpose being to govern rather than to represent.

The broadening of Christian democratic parties in Europe from religious defence organizations to broader parties of the centre-right is the classic case of the transition to catch-all status. The subsequent transformation of several mass socialist parties into leader-dominated social democratic parties, as in Spain and the United Kingdom, is another example. While most major parties are now of the catch-all type, their origins inside or beyond legislatures continue to influence party style, the autonomy of their leaders, and the standing of ordinary members.

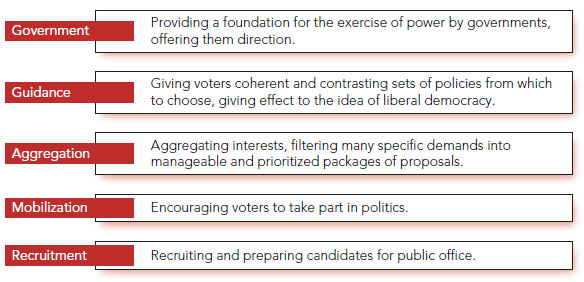

Modern democratic parties fulfil several functions that are critical to the formation of governments and the engagement of voters. Prime among these is the formation of governments. They also (at least ideally) offer voters guidance by helping them make choices among different sets of policies, help voters make themselves heard by pulling together like-minded segments of the electorate, encourage voters to participate in politics, and feed government by recruiting candidates for public office (see Figure 15.1).

Party systems

Just as the international system is more than the states that comprise it, so a party system is more than its individual parties. The term describes the overall pattern formed by the component parties, the interactions between them, and the rules governing their conduct. Parties copy, learn from, and compete with each other, with innovations in organization, fundraising, and campaigning diffusing across the system. By focusing on the relationships between parties, a party system means more than just the parties themselves, and helps us understand how they interact with one another, and the impact of that interaction on the countries they govern.

FIGURE 15.1: Five roles of political parties

Party system: The overall configuration of political parties, based on their number, their relative importance, the interactions among them, and the laws that regulate them.

There are also close links between the structure of elections and the party systems that result, if we accept the findings of the political scientist Maurice Duverger. As a result of research undertaken during the 1940s, he developed two principles published in his 1951 book Political Parties: first, that single-member plurality elections tend to produce two-party systems, and second that two-round and proportional representation elections tend to produce multi-party systems (Duverger, 1951). Others noticed the same effects, which eventually came to be known – respectively – as Duverger’s law and Duverger’s proposition (Benoit, 2006).

Duverger’s law: More of a hypothesis than a universal law, this holds that ‘The simple-majority single-ballot system favours the two-party system’ (Duverger, 1951).

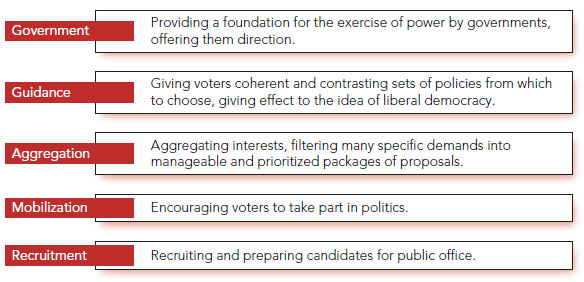

Party systems fall into one of five types: no-party, single-party, dominant party, two-party, and multi-party (see Figure 15.2). In democracies, both dominant and two-party systems are in decline, meaning that multiparty systems have become the most common configuration in the democratic world.

No-party systems

There are a small number of authoritarian states – mainly in the Middle East – that either do not allow political parties to form and operate, or where no parties have been formed. In the cases of Oman and Saudi Arabia, there is no legislature and the formation of parties is banned, although there are several movements in place that would evolve into parties if allowed, and Saudi Islamists made a largely symbolic request to the king in 2011 that they be allowed to form a party.There is no formal legal framework for parties in Bahrain, but there are active ‘political associations’ that compete in elections and are the functional equivalent of parties.

FIGURE 15.2: Comparing party systems

Single-party systems

These were once common, being found throughout the communist world as well as in most African and Arab countries.The argument made by most communist parties is that communism is the answer to all needs, alternative ideologies are moot, and democracy exists within communist parties in a phenomenon dubbed ‘democratic centralism’ by Lenin.The idea is that in a hierarchical system, each level is elected by the one below, to which it must in turn account (the democratic part) but decisions reached by higher levels are to be accepted and implemented by lower levels (the centralism part). In truth, the party is anything but democratic, and is instead highly elitist, based on alleged democracy within a party rather than among competing parties. In addition, membership is restricted, and offers a gateway to political influence and economic privileges, with non-party members being marginalized and, as a result, often resentful.

In China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the source of all meaningful political power, controls all other political organizations, plays a key role in deciding the outcome of elections, and dominates both state and government. Policy changes come not through a change of party at an election or a substantial public debate, but rather through changes in the balance of power within the leadership of the party.

From a base of 3.5 million primary party organizations – found in villages, factories, military units, and other local communities – the party works its way up through an elaborate hierarchy to the National Party Congress, which meets infrequently and delegates authority to a 370-member Central Committee, to a 25-member Politburo, and finally to the seven people who make up the Standing Committee of the Politburo, from which they exert enormous influence over the most populous country on earth – in itself, an astonishing political achievement.

Dominant party systems

In a dominant party system, one party outdistances all the others and becomes the natural party of government, even if it sometimes governs in coalition with junior partners. Dominant parties may fall victim to their own success, their very strength meaning that factions tend to develop internally, leading to an inward-looking perspective, a lack of concern with policy, excessive career-ism, and increasing corruption. This is not to suggest that a dominant party system is inherently corrupt and undemocratic, though, and there are several examples of parties that once dominated but which have had to learn to share power; these include the Institutional Revolutionary Party in Mexico, Japan’s Liberal Democrats, Sweden’s Social Democrats (which since 1932 has been in government for all but 16 years), and Italy’s Christian Democrats.

The Japanese Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has governed the country since 1955, except for breaks in 1993–6 and 2009–12. Although supposedly a united political party, the LDP is made up of several factions, each with its own leader, and these factions provide a form of intra-party competition. During times of LDP rule, the prime minister is not necessarily the leader of the LDP, nor even the leader of the biggest faction, nor even the leader of any faction, but rather the person who wins enough support among the competing factions to form a government. The LDP has kept power for many reasons, including its association with Japan’s post-war economic renaissance, an impressive network of grassroots supporter groups, the distribution of patronage to its own electoral districts, and the inability of opposition parties to mount an effective challenge.

A classic example of diminished dominance is offered by the Indian National Congress, most often known simply as Congress. Under Mahatma Gandhi it provided the focus of resistance to British colonial rule, and rose to leadership with India’s independence in 1947. To maintain its position, the party relied on a patronage pyramid of class and caste alliances to sustain a national organization in a fragmented and religiously divided country. Lacking access to the perks of office, no other party could challenge its hegemony. But authoritarian rule during the state of emergency declared by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (1975–7) cost Congress dear, and the party suffered its first defeat at a national election in 1977. It regrouped briefly but has been unable to fend off rising support for the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, and in 2014 suffered its biggest defeat ever with just 19 per cent of the vote.

An example of a party which retains its dominant position is South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC). This party has multiple advantages, stemming not only from cultural memories of its opposition to apartheid and from its strong position among the black majority, but also from its use of office to reward its own supporters. Since the end of the apartheid regime in 1994, there have been five sets of elections in South Africa and the ANC has never won less than 62 per cent of the vote, a remarkable achievement. However, factions and corruption are growing problems, and they may eventually threaten the ANC’s supremacy.

Two-party systems

In a two-party system, two major parties of comparable size compete for electoral support, providing the framework for political competition while the other parties exert little, if any, influence on the formation and policies of governments. The two major parties alternate in power, with one or the other always enjoying a majority. Having said that, though, the two-party format – like dominant parties – is rare and becoming rarer.

The United States is one of the last hold-outs, dominated since 1860 by the Democrats and the Republicans. These two parties have been able to hold their positions in part because of the arithmetic of plurality electoral systems (see Chapter 16), and in part because – in most US states – the parties decide the borders of electoral districts and can design them to maximize their chances of winning seats. In particular, winning a US presidential election is a political mountain which can only be climbed by major parties capable of assem-bling a broad national coalition and of raising the astro-nomical funding needed to launch a bid.The two major parties have also proved adept at moving to the left or the right in order to absorb the policies and the voters of any third party that might seem to be on the rise. In the temple of free-market economics, the two leading parties form a powerful duopoly.

Australia is another example of a two-party system, again reinforced by a non-proportional electoral system. Liberals and Labor have consistently been the two biggest parties since the Second World War, winning 80–90 per cent of the seats in Parliament between them. They have only been stopped from forming a US-style duopoly by the much smaller National Party, whose base lies in the rural areas. Government in Australia has alternated between Labor governing alone and the Liberals governing in coalition with the Nationals.

Elsewhere, Britain was long presented as an emblem of the two-party pattern, but it has recently struggled to pass the test.The Conservative and Labour parties regularly alternated in office, with plurality elections meaning that their share of seats exceeded their share of votes, but third parties have gained ground. In 2010, the centre Liberal Democrats won 57 seats in a Parliament of 650 members, forming a coalition with the Conservatives after no party won an overall majority. However, the Conservatives were able to win with a small majority in 2015 when the Liberal Democrats imploded and the Labour Party failed to offer a credible challenge.

Multi-party systems

In multi-party systems, several parties – typically, at least five or six – each win a significant bloc of seats in the legislature, becoming serious contenders for a place in a governing coalition. The underlying philosophy is that political parties represent specific social groups (or opinion constituencies such as environmentalists) in divided societies. The legislature then serves as an arena of conciliation, with coalitions forming and falling in response to often minor changes in the political balance. Europe exemplifies the phenomenon, most countries in the region having parties drawn from some, but not all, of nine major party families (see Table 15.1).

A good example is offered by Denmark, where no party has held a majority in the unicameral Folketing since 1909. The country’s complex party system has been managed through careful consensus-seeking but this practice has come under some pressure from the rise of new parties. In an explosive election in 1973, three new parties achieved representation and, since then, a minimum of seven parties have won seats in the legislature. The centre-right ‘Blue’ coalition that followed the 2015 election comprised five of these, controlling 90 seats, or just five more than the opposition ‘Red’ coalition.

Brazil has developed a particularly colourful multi-party system since its return to civilian government in 1985. No less than 28 parties won seats in the 2014 elections to the Chamber of Deputies, representing a wide range of opinions and interests that coalesced into a pro-government coalition, two opposition coalitions, and a cluster of stand-alone parties. Twelve parties each had fewer than ten members, and the pro-government coalition contained nine parties that together controlled 59 per cent of the seats. The picture in Brazil is complicated by a widespread aversion to right-wing parties (stemming from the heritage of the military years), weak discipline within many of the smaller parties, and the powerful role played by other actors, such as state governors.The result is a system that has been labelled ‘coalition presidentialism’, describing presidents who must rely on large and unstable coalitions to pass legislation (Gómez Bruera, 2013: 94–5).

TABLE 15.1: Europe’s major party families

| Examples | |

| Far left | Left Front (France), Left Party (Sweden). |

| Green | Alliance ‘90/The Greens (Germany), Green League (Finland), Greens (Sweden). |

| Social democrat | Social Democrats (Denmark, Finland, Sweden), Democratic Party (Italy), Labour (UK). |

| Christian democrat | Christian Democratic Union (Germany), Fine Gael (Ireland), People’s Party (Spain). |

| Conservative | Conservative Party (UK, Norway). |

| Centre | Centre Party (Finland, Norway, Sweden). |

| Liberal | People’s Party (Netherlands), Venstre (Denmark), Liberal Democrats (UK). |

| Far right | New Flemish Alliance (Belgium), National Front (France), Party for Freedom (Netherlands), Sweden Democrats. |

| Regional | Scottish National Party, Christian Social Union (Bavaria), New Flemish Alliance (Belgium). |

An important element of multi-party systems in several countries is parties that operate only at the regional level (or at the state level in federations). Britain, for example, has parties that represent the interests of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, while the German Christian Democratic Union is in a sustained coalition with the Christian Social Union, which operates only in the state of Bavaria. Few countries offer a more varied array of regional parties than India, where such parties now play an expanded role in national politics. For example, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance relied heavily after the 2009 elections on regional parties in the states of West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, and Maharashtra. The 2014 election resulted in an 11-seat majority for the Bharatiya Janata Party, but it continued to be part of a coalition originally formed in 1998, in which it worked with nearly 30 regional parties with nearly 60 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower chamber of the Indian Parliament.

Party organization

Large political parties are multilevel organizations, with their various strata united by a common identity and, sometimes, shared objectives. A major party’s organization will include staff or volunteers operating at national, regional, and local levels, and even at a wider level in the case of those national parties in Europe that have formed pan-European federations. This complexity means that any large party is decentralized.While references to ‘the party’ as a single entity are unavoidable, they simplify a highly fragmented reality. As Bolleyer (2012: 316) says, ‘parties are not monolithic structures’.

Party ‘organization’ is sometimes too grand a term. Below the centre, and especially in areas where the party is electorally weak, the party’s organization may be little more than an empty shell. And coordination between levels is often weak. Some authors even draw a comparison between parties and franchise organizations such as McDonald’s (Carty, 2004). In a franchise structure, the centre manages the brand, runs market-ing campaigns, and supports the operating units, leaving local units to act with considerable autonomy. Party leaders set policy priorities, develop their organization’s image, and provide material for election campaigns. But local agents are left to get on with key tasks: selecting candidates, for example, or implementing election strategy at local level.

Opinion has been changing as regards the question of where authority lies in parties. Thinking was long dominated by the arguments posed by the German scholar Robert Michels (1875–1936). In Political Parties (1911), Michels argued that even organizations with democratic pretensions become dominated by a ruling clique of leaders and supporting officials. Using Germany’s Social Democrats as a critical case, he suggested that leaders develop organizational skills, expert knowledge, and an interest in their own continuation in power.The ordinary members, aware of their inferior knowledge and amateur status, accept their own subordination as natural. Michels’s pessimism about the possibility of democracy within organizations such as political parties was expressed in his famous iron law of oligarchy: ‘to say organization is to say a tendency to oligarchy’ (often reproduced as ‘who says organization, says oligarchy’).

A recent phenomenon in many European countries has been the rise of niche parties that appeal to a narrow part of the electorate. These include far right, nationalist, regional, and green parties, which – unlike mainstream parties – rarely prosper by moderating their position, instead achieving most success from exploiting their natural support group (Meguid, 2008). Several of these parties – including the German Greens, Austria’s Freedom Party, and Switzerland’s People’s Party (Ignazi, 2006) – have participated in coalitions, while others (such as the Scottish National Party) have succeeded in influencing the agenda of mainstream parties.

Niche parties of the far right deserve particular attention. They are an exception to the thesis that parties emerge to represent well-defined social interests. Evidence suggests that they draw heavily on the often transient support of uneducated and unemployed young men. Disillusioned with orthodox democracy and by the move of established conservative parties to the centre, this constituency is attracted to parties that blame immigrants, asylum seekers, and other minorities not only for crime in general, but also for its own insecurity (cultural, as well as economic) in a changing world (Kitschelt, 2007).

It is tempting to identify a new cleavage here: between the winners and losers from contemporary labour markets. In the winner’s enclosure stand well-educated, affluent professionals, proudly displaying their tolerant post-material liberalism. But in the shadows we find those without qualifications, without jobs, and without prospects in economies where full-time unskilled jobs have been exported to lower-cost producers. In this context, the perceived economic success of immigrants, especially those of a different colour, is easily regarded with resentment.

Such analysis is plausible, but we should note that the division between labour market winners and losers is not a social cleavage in the classic sense. The traditional industrial working class was supported by an organizational infrastructure of labour unions and socialist parties. But far right parties are supported by alienated individuals, rather than by social and political institutions. So, in considering the far right it may be preferable to speak not of a new cleavage but, rather, of post-cleavage analysis – of what Betz (1994: 169) called ‘political conflict in the age of social fragmentation’.

We should not be carried away. Many right-wing movements have proved to be short-lived flash parties whose prospects are held back by inexperienced leaders with a dubious background who have proved to be inept participants in coalition governments (Akkerman, 2012). Many protest voters might cease to vote for niche parties if they became leading parties, thus creating a natural ceiling to their support. Even joining a coalition dilutes the party’s outsider image. So, in this sense, niche parties may lack the potential of those based on a more secure and traditional cleavage (McDonnell and Newell, 2011).

Niche party: A political party that appeals to a narrow section of the electorate.They are positioned away from the established centre and highlight one particular issue.

Iron law of oligarchy: As developed by Robert Michels, this states that the organization of political parties – even those formally committed to democracy – becomes dominated by a ruling elite.

Elite recruitment continues to be a vital and continuing function of parties: even as parties decline in other ways, they continue to dominate elections to the national legislatures from which, in democracies, most political leaders are drawn. Given that candidates nominated for safe districts, or appearing near the top of their party’s list, are virtually guaranteed a place in the legislature, it is the selectorate, not the electorate, which makes ‘the choice before the choice’.The nomi-nators open and close the door to the house of power (Rahat, 2007). At the same time, there is evidence of a growing role for ordinary party members in the selection of leaders and candidates, a finding which suggests that Michels’s iron law is corroding as parties seek to retain members by giving them a greater if still limited voice in party affairs (Cross and Katz, 2013). If parties are becoming more democratic, the democracy is of a representative rather than direct kind.

Safe district: An electoral district in which a political party has such strong support that its candidate/s are all but assured of victory.

Selectorate: The people who nominate a party’s candidates for an election.

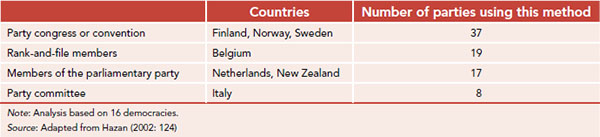

Party leaders

The method of selecting the party leader deserves more attention that it usually receives (Pilet and Cross, 2014), for the obvious reason that party leaders in most parliamentary systems stand a good chance of becoming prime minister. In some countries, to be sure, including many in continental Europe, the chair of the party is not allowed to be the party’s nominee for the top post in government (Cross and Blais, 2012a: 5). In Germany, for instance, the party’s candidate for chancellor is appointed separately from the party leader and need not be the same person. In the United States, the presidential candidate and chair of the party’s national committee are different people; indeed, the former usually chooses the latter. Nonetheless, it is important to review the mechanics and implications of the selection of the party’s leader.

In the same way that many parties afford their ordinary members a greater voice in candidate selection, so too has the procedure for selecting the party leader become more inclusive. As Mair (1994) notes, ‘more and more parties now seem willing to allow the ordinary members a voice in the selection of party leaders’. One factor here is the desire to compensate members for their declining role in what have become media-driven election campaigns; after all, party volunteers, unlike paid employees, can just walk away if they are given nothing interesting to do. The catalyst for reform is often an electoral setback or a desire to be seen as inclusive (Cross and Blais, 2012b).

The traditional method for choosing party leaders is election by members of the party in the legislature, a device that is still used in several parliamentary systems, including Australia, Denmark, and New Zealand. Interestingly, several parties give a voice both to members of parliament and ordinary members, either through a special congress or a two-stage ballot. For instance, the British Conservatives offer ordinary members a choice between two candidates chosen by the parliamentary party. Although this would appear to be a more democratic option, it can lead to problems when the rank-and-file membership is out of step with the national party, resulting in the triumph of local over national interests.

A vote of the party’s members of the legislature alone is, of course, a narrow constituency. And the ability of potential leaders to instil confidence in their parliamentary peers may say little about their capacity to win a general election fought through television and social media. Even so, colleagues in the assembly will have a close knowledge of a candidate’s abilities; they provide an expert constituency for judging the capacity to lead not only the party, but also – more importantly – the country. Members of a legislature appear to be more influenced by experience than are ordinary party members. It is perhaps for this reason that many parties still permit the parliamentary party to remove the leader, even if the initial selection now extends to other groups (Cross and Blais, 2012a).

TABLE 15.2: Selecting party leaders in liberal democracies

A ballot of party members is an alternative and increasingly popular method of selecting leaders. Such elections, often described as OMOV (one member, one vote) contests, provide an incentive for people to join the party, and can also be used to limit the power of entrenched factions within it. In Belgium, for example, all the major parties have adopted this approach to choosing their party president. In Canada, too, all major parties (except the Liberals) have adopted OMOV.

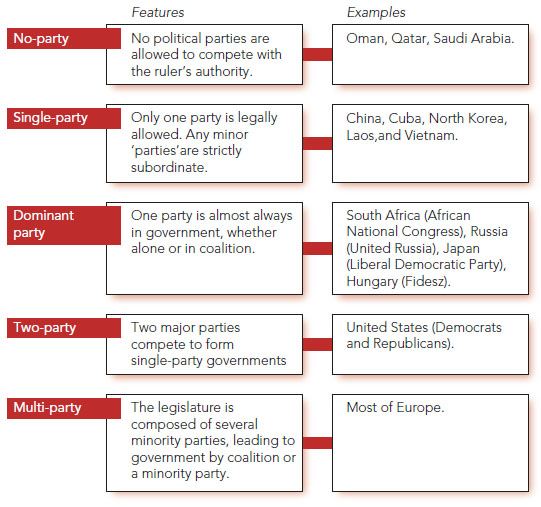

Candidates

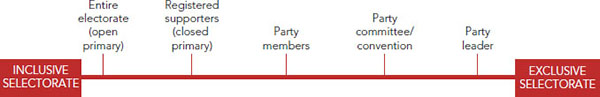

There are several options available for selecting legislative candidates, ranging from the exclusive (selection by the party leader) to the inclusive (an open vote of the entire electorate) (Figure 15.3). Reflecting the complexity of party organization, the nomination process is generally decentralized; a few parties give control to the national leadership, but even here the leaders usually select from a list generated at lower levels. More often, local parties are the active force, either acting autonomously or putting forward nominations to be ratified at national level. Smaller and more extreme parties tend to be the most decentralized in their selection procedures.

The nomination task is constrained by three wider features of the political system:

• The electoral system: Choosing candidates for individual constituencies in a plurality system is a more decentralized task than preparing a single national list in a party list system (see Chapter 16).

• Incumbents: Sitting members of a legislature have an advantage almost everywhere, usually achieving rese-lection without much fuss. Often, candidates for office are only truly ‘chosen’ when the incumbent stands down.

• Rules: Nearly all countries impose conditions such as citizenship on members of the legislature while many parties have also adopted gender quotas for candidates.

Consider how the electoral system affects the nomination process. Under the list form of proportional representation, parties must develop a ranked list of candidates to present to the electorate. This obliges central coordination, even if candidates are suggested locally. In the Netherlands, for example, each party needs to present a single list of candidates for the whole country. The major parties use a nominating committee to examine applications received either from local branches, or directly from individuals. A senior party board then produces the final ordering.

In the few countries still using the single-member plurality method, the nomination procedure is typically more decentralized. Candidates must win selection by a local party in a specific district, though often they must pre-qualify by gaining inclusion on a central master list of approved candidates. The result of this can be to put the interests of the local party and individual districts above the interests of the national party and voters at large.

The United States has gone furthest in opening up the selection process. There, primary elections enable a party’s supporters to choose their candidates for a particular office, ranging as high as the presidency. In the absence of a tradition of direct party membership, a ‘supporter’ is generously defined in most states as anyone who declares, in advance, an affiliation to that party, and can thereby take part in a closed primary.The holding of an open primary extends the choice still further: to any registered elector.

FIGURE 15.3: Who selects candidates for legislative elections?

Source: Adapted from Hazan and Rahat (2010: figure 3.1)

Primary election: A contest in which a party’s supporters select its candidate for a subsequent election (a direct primary), or choose delegates to the presidential nominating convention (a presidential primary). A closed primary is limited to a party’s registered supporters.

An increasing number of countries operate a mixed electoral system, in which voters make choices for both a party list and a district candidate. These circumstances complicate the party’s task of selecting candidates, requiring a national or regional list, plus local constituency nominees. In this situation, individual politicians also face a choice: should they seek election by means of the party list, or through a constituency? Many senior figures ensure they appear on both ballots, using a high position on the party’s list as insurance against restless-ness in their home district.

Party membership

Party membership was once an important channel for participation in politics, but this is no longer the case: most major European countries saw a dramatic fall in party membership between the 1960s and the 1990s (see Table 15.3), for instance in Denmark where membership collapsed from one in every five people to one in every 20. The drop continued into the 2000s, with membership of Sweden’s Social Democrats falling by nearly 70 per cent between 1999 and 2005 alone (Möller, 2007: 36).Writing about the Netherlands,Voerman and van Schurr (2011) concluded that ‘the era of the mass party [was] over’. Across the democratic world, millions of party foot soldiers have simply given up.

Furthermore, many new members do not engage with their party beyond paying an annual subscription; these credit card supporters tend also to be fair-weather supporters, resulting in increased turnover. Their commitment to the party is often no greater than to other voluntary groups to which they donate. Lacking a steady flow of young members, the average age of members has gone up; belonging to a party is increasingly a pastime for the middle-aged and elderly (Scarrow and Gezgor, 2011).

However, we should place this recent decline in a longer perspective. If statistics were available for the entire twentieth century, they would probably show a rise in membership over the first two-thirds of the century, followed by a fall in the final third. The recent decline is from a peak that was only reached, in many countries, in the 1970s. In other words, it is arguably the bulge in membership after the Second World War, rather than the later decline, which requires explanation.

The recent reduction in membership has occurred in tandem with dealignment among voters (see Chapter 17) and reflects similar causes.These include:

• The weakening of traditional social divisions such as class and religion.

• The loosening of the bond linking labour unions and socialist parties.

• The decay of local electioneering in an era of media-based campaigns.

• The greater appeal of social movements and social media.

TABLE 15.3: Europe’s declining party membership

• The declining standing of parties, often linked to cases of corruption.

• The perception of parties as forming a single structure of established authority with the state (Whiteley, 2011).

As we saw in discussing political participation generally (Chapter 13), it should not automatically be assumed that less is worse.The fall may indicate an evolution in the nature of parties, rather than a weakening of their significance in government. Crotty (2006: 499) notes how ‘the demands of society change, and parties change to meet them’. Scarrow and Gezgor (2010) also argue that while membership has been falling, some parties in Europe have seen a growth in the power of their members to select candidates, leaders, and party policies. This suggests, they conclude, that ‘today’s smaller but more powerful memberships still have the potential to help link their parties to a wider electoral base’. Social and political change has meant that it is unrealistic to expect the rebirth of mass membership parties with their millions of members and their supporting pillars of labour unions and churches. Instead we find the modern format of parties found in new democracies: lean and flexible, with communication from leaders through television and social media. Rather than relying on a permanent army of members, such parties mobilize volunteers for specific, short-term tasks – notably, election campaigns.

Party finance

Falling membership means reduced income for parties in an era when expenses (not least for election campaigns) continue to rise.The problem of funding political parties has therefore become highly significant. Should members, donors, or the state pay for the party’s work? Should private donations be encouraged (to increase funds and encourage participation) or restricted (to maintain fairness and reduce scandals)? Do limits on contributions and spending interfere with free speech? Whichever is the case, some method of funding parties must be found while also minimizing the ever-present danger of corruption.

In the main, the battle for public funding has been won. State support for national parties is now all but universal in liberal democracies. On a global level, research by the Swedish-based International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) has found that more than two-thirds of 180 countries studied made provision for public funding of parties by 2011; a similar proportion offer free or subsidized access to the media (IDEA, 2014). As Fisher and Eisenstadt (2004: 621) had earlier commented, ‘public subsidies have replaced private sponsorship as the norm in political finance’. State subsidies have also developed quickly in the new democracies of Eastern Europe, where party memberships are far smaller than in the West.

Typically, support is provided for legislative groups, election campaigns, or both. Campaign support, in turn, may be offered to parties, candidates, or both. In an effort to limit state dependence, public funding may be restricted to matching the funds raised by the party from other means, including its members. In any case, most funding regimes only reimburse a specified amount of party spending.

As with many political issues, there are costs and benefits involved in the question of state funding of parties (see Focus 15.2). One of the biggest points of concern is the advantage that large established parties have over small news ones in access to public funding. Some authors have developed this point by suggesting that the transition to public funding has led to a convergence of the state and major parties on a single system of rule. Governing parties, in effect, authorize subsidies for themselves, a process captured by Katz and Mair’s idea (1995) of cartel parties: ‘colluding parties become agents of the state and employ its resources to ensure their own survival’. The danger of cartel parties is that they become part of the political establishment, weakening their historic role as agents of particular social groups and inhibiting the growth of new parties in the political market.

Cartel party: Leading parties that exploit their combined dominance of the political market to establish rules of the game, such as public funding, which reinforces its own strong position.

On a worldwide basis, and including authoritarian regimes in which parties are permitted, nearly all countries now regulate donations in some way.The vast majority ban political donations by government and its agencies to parties and candidates (other than through regulated public funding); most also disallow donations from overseas parties and candidates. However, only a few countries currently place limits on the size of donations, and only one-fifth ban corporate donations. As IDEA (2012: 51) points out, even these limits can be ineffective, either because financial reports are inadequately monitored, or because restrictions on donations to parties are circumvented by helping candidates directly, or because the limits are ignored.

Because they started out by representing the interests of groups, political parties were once supported mainly by these groups, whether through membership fees or donations. But as membership has fallen, parties have had to look for other sources of financial support, and they have focused increasingly on public funding; that is, taxpayer support. The rising use of public funding has both advantages and disadvantages.

| Arguments in favour | Arguments against |

| Parties perform a public function by supplying leaders, candidates, and policies. | Public financing reduces a party’s incentive to attract members. |

| Parties should be funded to a professional level and not appear cheap. Marketing should match private sector standards. | Public funding reinforces the status quo, because it favours large established parties over new ones. |

| Public funding creates a level playing field between parties. | Public funding is a form of creeping nationalization, creating parties that serve the state, not society. |

| Without public support, pro-business parties gain access to greater funding. | Public funding favours established and large parties, encouraging a cartel. |

| Relying on public funding decreases the opportunities for corruption. | To maintain a level playing field, spending should be capped, rather than subsidized. |

| Why should taxpayers fund parties against their wishes? A tax credit for voluntary donations is a preferable compromise. | |

| Corruption can be reduced by banning anonymous donations, rather than adopting public funding. |

The main outlier in the discussion about political funding is the United States, where campaigns are uniquely expensive and few limits have been imposed on the sources of funding. According to the Center for Responsive Politics (2015), a Washington DC-based watchdog body, spending on American elections grew from $3 billion in the 2000 cycle to nearly $6.3 billion in the 2012 cycle. Such massive figures are beyond compare, and detailed regulation of contributions has proved ineffective; there is no cap on spending (except for presidential candidates unwise enough to accept public funding), campaign costs continue to escalate, and the US Supreme Court has determined that limits on contributions are unconstitutional on the grounds of free speech. Campaign advertising by groups which are independent of candidates is also unrestricted.

Political parties in authoritarian states

‘Yes, we have lots of parties here’, says President Naz-arbaev of Kazakhstan. ‘I created them all’ (quoted in Cummings, 2005: 104). This quote reflects the secondary character of parties in most authoritarian regimes. The party is a means of governing, and neither a source of power in itself nor a channel through which elections are contested, won and lost. As Lawson (2001: 673) says of parties under dictatorships, ‘the party is a shield and instrument of power. Its function is to carry out the work of government as directed by other agents with greater power (the military or the demagogue and his entourage).’ In doing this, it often presents itself as pursuing a national agenda based on a key theme such as anti-imperialism, national unity, or economic development, but such messages are often a means of legitimizing power rather than a substantive commitment.

Brief Profile: Although Brazil is widely regarded as the major rising power of Latin America, further north there have been critical developments in Mexico. A programme of democratization since the 1990s has been so successful that the Institutional Revolutionary Party – in power without a break since 1929 – lost the presidency in 2000. Almost equally significant have been Mexico’s economic reforms, which have brought greater freedom to a large market and have broadened the economic base of one of the world’s biggest oil producers. But the intertwined problems of drugs, violence and corruption remain, and political scientists are divided about how best to describe Mexico; analyses are peppered with terms such as bureaucratic, elitist, and patrimonial. And while the economy is one of the world’s 15 largest, many of its people remain poor and under-employed. It is common to hear talk of two Mexicos: one wealthy, urban, modern and well educated and the other poor, rural, traditional and under-educated.

Form of government  Federal presidential republic consisting of 31 states and the Federal District of Mexico City. State formed in 1821, and most recent constitution adopted 1917.

Federal presidential republic consisting of 31 states and the Federal District of Mexico City. State formed in 1821, and most recent constitution adopted 1917.

Legislature  Bicameral National Congress: lower Chamber of Deputies (500 members) elected for three-year terms, and upper Senate (128 members) elected for six-year terms. Members may not serve consecutive terms.

Bicameral National Congress: lower Chamber of Deputies (500 members) elected for three-year terms, and upper Senate (128 members) elected for six-year terms. Members may not serve consecutive terms.

Executive  Presidential. A president is elected for a single six-year term, and there is no vice president.

Presidential. A president is elected for a single six-year term, and there is no vice president.

Judiciary  A Supreme Court of 11 members nominated for single 15-year terms by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

A Supreme Court of 11 members nominated for single 15-year terms by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

Electoral system  A straight plurality vote determines the presidency, while mixed member majoritarian is used for the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate: 300 single-member plurality (SMP) seats and 200 proportional representation seats in the Chamber, and a combination of SMP, first minority and at-large seats in the Senate.

A straight plurality vote determines the presidency, while mixed member majoritarian is used for the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate: 300 single-member plurality (SMP) seats and 200 proportional representation seats in the Chamber, and a combination of SMP, first minority and at-large seats in the Senate.

Parties  Multi-party. Mexico was long a one-party system, but democratic reforms since the 1990s have broadened the field such that three major parties now compete at the national and state level, with a cluster of smaller parties.

Multi-party. Mexico was long a one-party system, but democratic reforms since the 1990s have broadened the field such that three major parties now compete at the national and state level, with a cluster of smaller parties.

Geddes (2005) argues that in spite of the risks potentially posed to authoritarian regimes by allowing parties and elections, there are several roles they can fulfil that dictators find useful:

• Helping solve intra-regime conflicts – or enforcing elite bargains – that might otherwise end or destabilize the rule of the dictator.

Political parties in Mexico

Mexico has seen a remarkable transformation in recent decades from a one-party dominant system to a truly competitive multi-party system, with three major national parties capable of winning the highest offices: a greater selection than is offered by the country’s northern neighbour, the United States.

Between 1929 and 2000, power was all but monopolized by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which won every presidential election, held large majorities in both chambers of Congress, and won almost all state and local elections as well. It kept its grip on power by multiple means, including being a source of patronage, incorporating the major social and economic sectors in Mexico, co-opting rival elites, mobilizing voters during elections, and overseeing the electoral process. It had no obvious ideology, but instead shifted with the political breeze and with the changing priorities of its leaders.

When economic problems began to grip Mexico in the 1970s, and again in the 1990s, PRI could not blame the opposition. Mexicans were also becoming better educated and more affluent, with increasing demand for more choice in their political system. PRI began to change the rules in order to allow opposition parties to win more seats, hoping that this would defuse demands for change. Instead, it lost its first national legislative elections in 1997, and lost the presidency for the first time in 2000, to the more conservative National Action Party (PAN). In 1997, the leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), won the second most powerful executive post in the country: the office of mayor of Mexico City.

Questions continue to be asked about the fairness of elections, but today Mexican voters have a wide array of political parties from which to choose, ranging across the political spectrum: PAN sits on the right, PRI straddles the centre, and PRD sits on the left, with a cluster of smaller parties including greens and the left-wing Labor Party. PRI regained the presidency in 2012 with the victory of Enrique Peña Nieto, and PRI and PAN are developing a track record as the two largest parties in the Mexican Congress, with PRD and smaller parties holding the balance.

• A ruling party provides a counter-balance to other potential threats, notably the military.

• Elections help to identify and purge potential rivals for power.

• A dominant party can oversee elections, distribute bribes to voters and provide a channel for rewarding loyal members.

• A leading party and election campaigns provide a useful channel of information from government to the people and, on routine matters, from people to the government.

• A national party must organize supporter networks throughout the country, thereby extending the government’s reach into outlying districts.

• A governing party educates and socializes members to support the regime’s ideology and economic strategy. Elections campaigns attempt the same for ordinary citizens.

The longer-term result is that, rather than threatening authoritarian regimes, what Geddes describes as ‘support parties’ can prolong the political life not just of individual leaders but also of the regimes themselves. Of course, many of these functions are also performed by parties in democracies but parties in democracies provide additional value. They were often founded as a result of social cleavages, and continue today to appeal to groups of voters based on competing views about economic and social issues. In many poorer authoritarian states, politics is driven more by differences of identity and interest rather than policy. Ethnic, racial, religious and local identities matter more than policy preferences.

Nigeria illustrates these points. It has a long history of political party activity, predating its independence from Britain in 1960. Its first party – National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons – was founded in 1944 on a platform of Nigerian nationalism, but was quickly joined (in 1948 and 1949 respectively) by the Action Group and the Northern People’s Congress, based respectively in western and northern Nigeria. It was the breakdown of parties along ethnic lines that led to the collapse of two civilian governments in 1966 and 1983, and a futile effort was made by the military government in 1987 to invent two political parties named the Social

Democratic Party and the National Republican Convention. Concerns remain that in a strongly regional country, parties will continue to drift towards identification with the different ethnic groups. However, a peaceful election in 2015 did witness the first-ever defeat for an incumbent president standing for re-election, suggesting a maturing of the country’s party system and a transition to a more democratic order.

Political parties in Africa are a puzzle, in the sense that many seemingly similar countries have had very different records. Following independence in the 1950s and 1960s, the heroes of the nationalist struggle routinely put a stop to party competition, and one-party systems were established; the official party was often justified in terms of the need to build national unity, even if it only served as the leader’s personal vehicle.The tradition of the benevolent chief was skilfully exploited by dictators such as President Mobutu of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo):

In our African tradition, there are never two chiefs; there is sometimes a natural heir to the chief, but can anyone tell me that he has known a village that has two chiefs? That is why we Congolese, in the desire to conform to the traditions of our continent, have resolved to group all the energies of the citizens of our country under the banner of a single national party. (quoted in Meredith, 2006: 295)

But these single parties proved to be weak, they lacked autonomy from the national leader, and rather than building unity they merely entrenched the control of the elites. As with government itself, they had an urban bias, lacked presence in the rural areas, and showed little concern with policy. True, the party was one of the few national organizations and proved useful in recruiting supporters to public office but these functions could not disguise a lack of cohesion, direction, and organization. Indeed, when the founder-leader eventually departed, his party would sometimes disappear at the same time. This was what happened, for example, with the United National Independence Party (UNIP) in Zambia. Founded in 1959, it formed the first government of an independent Zambia in 1964, and stayed in power – as did Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda – until 1990. Following riots and a coup attempt that year, free elections were held in 1991 at which Kaunda was defeated. He retired from politics and UNIP sank into obscurity.

Despite recent economic growth, many African states still experience poverty, cultural heterogeneity, and centralized political systems that would seem to pose severe handicaps to democracy. Even so, Reidl (2014) finds that nearly two dozen have achieved a measure of democratic competition since the early 1990s; these include South Africa, Botswana, Ghana, Tanzania, and Mozambique. She suggests that the nature of the democratic transition shapes its success (see Chapter 3). In a counter-intuitive conclusion, she argues that where authoritarian incumbents are strong, they tightly control the democratic transition, leading to a stronger party system subsequently. Where the ruling party is weak, it loses control of the transition, allowing others to enter the process, resulting in a weaker party system.

An interesting – albeit rare – sub-variety of parties in authoritarian systems is one where the political party, rather than a dominant individual, is truly the real source of power. Singapore is one such case. The People’s Action Party (PAP) maintains a close grip despite permitting a modest, and perhaps increasing, level of opposition. Lee Kuan Yew, the island’s prime minister from 1959 to 1990, acknowledged that his party post, rather than his executive office, was the real source of his authority: ‘all I have to do is to stay Secretary-General of the PAP. I don’t have to be president’ (Tremewan, 1994: 184). Tremewan (p. 186) went on to refer to the ‘PAP-state’, in which the party uses its control of public resources to ensure citizen quiescence:

It is the party-state with its secretive, unaccountable party core under a dominating, often threatening personality which administers Singaporeans’ housing, property values, pensions, breeding, health, media, schooling and also the electoral process itself.

More typical of the story in authoritarian regimes is the case of Russia. At first glance it appears to have a wide range of political parties from which its voters can choose, but few of these have been able to develop either permanence or real influence. In fact, so many new parties were formed in the early years of democracy in the 1990s that they were often disparagingly described as ‘taxi-cab parties’ (driving around in circles, and stopping occasionally to let old members off and new ones on), or even ‘divan parties’ (they were so small that all their members could fit on a single piece of furniture). Clearly, when parties cease to exist from one election to the next, it is impossible for them to be held to account. Not surprisingly, they are the least trusted public organizations in a suspicious society (White, 2007: 27).

Far more than in the United States, voters in Russia’s presidential elections are choosing between candidates, not parties. The party is vehicle rather than driver. The biggest party in Russia today is United Russia, but Vladimir Putin was only informally allied with the party (and its predecessor Unity party) in the 2000 and 2004 elections. As prime minister in 2008–12 he became leader of the party, and was its candidate in the 2012 election, after which leadership moved to Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev. United Russia is what Russians term a ‘party of power’, meaning that the Kremlin uses threats and bribes to ensure it is supported by powerful ministers, regional governors and large companies.

Given the weak position of Russia’s parties, it is not surprising that they are poorly organized, with a small membership and minimal capacity to integrate a large and diverse country. In a manner typical of competitive authoritarian regimes, the rules concerning the registration of parties, the nomination of candidates, and the receipt of state funding are skewed in favour of larger parties. Minor parties are trapped: they cannot grow until they become more significant but their importance cannot increase until they are larger (Kulik, 2007: 201).

Party weakness of another kind is found in Haiti, also ranked as an authoritarian regime in the Democracy Index. A country that suffers at least as much from natural disasters as from political problems, Haiti is currently working off its 23rd constitution since becoming independent in 1804. Such volatility is both a cause and an effect of Haiti’s political difficulties, and its political parties demonstrate even less ability than its formal political institutions. It has elections, but they are rarely fair or efficient. It has a long history of political party activity, but has never developed durable parties with deep social roots. Party activity is at its greatest during presidential election seasons, when new parties emerge around the campaigns of the leading candidates. These have represented a wide range of issues, from Haitian nationalism to the interests of rural peasants, Haitian youth, communism, workers’ rights, and opposition to the incumbent government. However, they rarely survive much longer than the terms in office of the leaders with whom they are associated, and so parties play only a peripheral role in Haitian politics.

• Do we need political parties? If so, what are the most valuable functions they perform?

• Which is best: a multi-party system, or a two-party system?

• Which type of party system exists in your country? Does it reêct social divisions, voter preferences, the structure of government, or something else?

• Is it more democratic and e˚ective for parties to choose leaders and candidates themselves, or for the choice to be put in the hands of voters?

• What is the fairest and most democratic means of ˛nancing political parties and election campaigns?

• Are political parties dead, dying, or simply reforming?

KEY CONCEPTS

Cartel party

Duverger’s law

Iron law of oligarchy

Niche party

Party system

Political party

Primary election

Safe district

Selectorate

FURTHER READING

Brooker, Paul (2013) Non-Democratic Regimes: Theory, Government and Politics, 3rd edn.This wide-ranging examination of authoritarian rule includes a chapter on one-party rule.

Cross, William P. and Richard S. Katz (eds) (2013) The Challenges of IntraParty Democracy.This book considers the principal issues that parties and the state must address in introducing greater democracy within parties.

Gallagher, Michael, Michael Laver, and Peter Mair (2011) Representative Government in Modern Europe, 5th edn. An informative source on European politics, including extensive material on political parties.

Hazan, Reuven Y. and Gideon Rahat (2010) Democracy within Parties: Candidate Selection Methods and Their Political Consequences. A comparative analysis of candidate selection methods.

Riedl, Rachel Beatty (2014) Authoritarian Origins of Democratic Party Systems in Africa. A study of parties in Africa, looking at the challenging transitions from authoritarianism to competitive party systems.

Scarrow, Susan E. (ed.) (2002) Perspectives on Political Parties: Classic Readings. An interesting and unusual collection of primary documents, from various countries, revealing changing understandings of party politics in the nineteenth century.