PREVIEW

So far we have looked at comparative government and politics in broad terms, and it is probably already clear that it is a field of complexity and of conflicting analyses. It is tangled enough at the level of the individual state, but when we add multiple political systems to the equation, the challenges of achieving an understanding are compounded.Theory comes to the rescue by pulling together what might otherwise be a cluster of unstructured observations and facts into a framework that can be tested and applied in different places and at different times.

A theoretical approach is a simplifying device or a conceptual filter that helps us decide what is important in terms of explaining political phenomena. In other words, it can help us sift through a body of facts, decide which are primary and which are secondary, enable us to organize and interpret the information, and develop complete arguments and explanations about the objects of our study.

This chapter offers some insights into the theoretical approaches used by political scientists. There are so many that it is impossible in a brief chapter to be comprehensive; instead, we focus here on five of the most important: the institutional, behavioural, structural, rational, and interpretive approaches. The chapter begins with a brief review of the changing face of comparative politics and a sampling of the debates about theory, then goes through each of the five key approaches in turn, explaining their origins, principles, and goals, and offering some illustrative examples.

CONTENTS

• Theoretical approaches: an overview

• The changing face of comparative politics

• The institutional approach

• The behavioural approach

• The structural approach

• The rational choice approach

• The interpretive approach

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • Theoretical approaches are ways of studying politics, and help in identifying the right questions to ask and how to go about answering them. |

| • The institutional perspective has done most to shape the development of politics as a discipline and remains an important tradition in comparative politics. |

| • The behavioural approach examines politics at the level of the individual, relying primarily on quantitative analysis of sample surveys. |

| • structural approach focuses on networks, and looks at the past to help understand the present. In this way, it helps bridge politics and history. |

| • The rational choice approach seeks to explain political outcomes by exploring interactions between political actors as they pursue their particular interests and goals. |

| • The interpretive approach, viewing politics as the ideas people construct about it in the course of their interaction, offers a contrast to more mainstream approaches. |

Theoretical approaches: an overview

Theory is a key part of the exercise of achieving understanding in any field of knowledge. For comparative politics, it means developing and using principles and concepts that can be used to explain everything from the formation of states to questions of national identity, the character of institutions, the process of democratization, and the dynamics of political instability, political participation, and public policy.

Theory: An abstract or generalized approach to explaining or understanding a phenomenon.

Unfortunately, there are several complicating factors. First, the field of comparative politics is so broad that it includes numerous theoretical explanations, ranging from the broad to the specific. For some, there are so many choices that diversity can sometimes seem to border on anarchy (Verba, 1991: 38), prompting comparative politics to lose (or even lack) direction. For others, the variety is good because it gives comparativists a wide array of options, and allows them to be ‘opportunists’ who can use whatever approach works best (Przeworski, in Kohli et al., 1995: 16).

Second, comparative political theory has been criticized for focusing too much on ideas emerging from the Western tradition. As comparison takes a more global approach – pressed by the influence of globalization – there have been calls for it to be more inclusive. This trend will further expand the already substantial range of theoretical approaches.

Third, comparative political theory suffers the standard problem faced by political theory more generally of being the victim of fad and fashion. For every new theory that is proposed or applied, there is a long line of critics waiting to shoot it down and propose alternatives. It can sometimes seem as though the debate about theory is more about competing explanations than about their practical, real-world applications.

Finally, the place of theory in the social sciences more generally is based on shaky foundations. Many natural sciences have a strong record of developing theories that are well supported by the evidence, are broadly accepted, and can be used to develop laws and make predictions. The social sciences suffer greater uncertainties (if only because they focus more on trying to understand human behaviour), with the result that they generate theories that are subject to stronger doubts, and that have a weaker track record in generating laws and predicting outcomes.

In this chapter, we focus on the major theoretical approaches to the comparative study of politics. By ‘approaches’ we mean ways of understanding, or ‘sets of attitudes, understandings and practices that define a certain way of doing political science’ (Marsh and Stoker, 2010: 3).They are schools of thought that influence how we go about political research, that structure the questions we ask, that offer pointers on where we should seek an answer, and that help us define what counts as a good answer.

Five such approaches are worth close study. We will take them in an order that reflects the historical evolution of politics as an academic discipline, but for clarity will avoid the many subdivisions, crossovers, and reinventions within each perspective. We will argue that the institutional approach is the most important, but that the other frameworks provide important additional insights. We will also make the point that comparative political theory needs to take a more inclusive approach by bringing non-Western perspectives into the picture.

The changing face of comparative politics

Although comparison lies at the heart of all research, the sub-field of comparative politics is relatively young, and so is its theoretical base. As a systematic endeavour, it can be dated back to the formal origins of political science in the late nineteenth century, but it long lagged behind the study of domestic politics, and still lacks a well-developed identity. Comparative political theory is even younger, although Dallmayr may have overstated the case when he described it in 1999 as ‘either non-existent or at most fledgling and embryonic’.

We saw in Chapter 1 how Aristotle is credited with the first attempt to classify political systems, but his work was mainly descriptive and did not establish principles that had much staying power. And while both comparative politics and comparative political theory owe much to some of the biggest names in political science and philosophy – from Machiavelli to Montesquieu and Marx – none of them took a systematically comparative approach to understanding government and politics as we would define the task today.

Most other early examples of comparison were his-toricist in the sense that they tried to understand past events as determinants of the future, and so were only tangentially comparative; the German writer Johann Wolfgang van Goethe even once quipped that ‘only blockheads compare’ (von Beyme, 2011). The English philosopher John Stuart Mill, best known for his treatise On Liberty, made an early contribution to systematic comparison with his 1843 work A System of Logic. This outlined his five principles of inductive reasoning, which included methods of agreement and difference that are reflected in the most different and most similar system designs used today in comparative politics (see Chapter 6).

Not only was the systematic study of politics and government still in its formative phase in the nineteenth century, but there were also few cases available to compare, and scholars in most countries were more interested in studying their home political systems than in taking a broader view. For European scholars, the differences among European states were not seen to be particularly profound or interesting, so it is perhaps unsurprising that the birth of modern comparative politics took place in the United States (see Munck, 2007), where American scholars began to study ‘foreign’ political systems as distinct from their own. There remained a view, however, that Americans had little to learn from other systems, thanks to a deeply held belief that the American system was superior (Wiarda, 1991: 12). The few scholars who studied other systems focused mainly on Western Europe, with the Soviet Union and Japan added later, and their comparisons were more often descriptive than analytical.

Attitudes changed after the Second World War, when the foreign policy interests of the United States broadened, and the Cold War made American scholars and policy-makers more interested in understanding both their allies and their enemies. Eventually, this perspective extended to potential allies and enemies in Latin America, Asia, and Africa (Lim, 2010: 7–11). The end of the colonial era also saw a near-doubling in the number of sovereign states, from just over 70 in 1945 to more than 130 in 1970 (see Table 2.1). As well as a new interest in emerging states, there was also a change in the approach taken by comparative political scientists, whose past work had been often criticized for being too parochial, too descriptive, too lacking in theory, and not even particularly comparative (Macridis, 1955).As part of what became known as the ‘behavioural revolution’, comparativists became interested in studying processes as well as institutions, in explaining as well as describing, and in taking a more scientific approach to the development of theory and methods.

While most of the famous names of comparative politics until this time had been American – including Charles Merriam, Gabriel Almond, Seymour Martin Lipset, Lucien Pye, and Samuel Huntington – new influence was asserted by scholars with European backgrounds and interests, including Giovanni Sartori, Stein Rokkan, Philippe Schmitter, Maurice Duverger, and Arend Lijphart. There was also more transfer of ideas between the study of domestic and comparative politics, and new interests were added with the break-up of the Soviet Union, the end of the Cold War, the emergence of the European Union, and the growing importance of states such as Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and South Africa.

Just as quickly, there was a reaction against the focus by behaviouralists on the scientific method and their attempts to develop a grand theory of comparative politics. A difference of opinion also developed between scholars favouring a quantitative approach (based on data analysis and emphasizing breadth over depth) and those favouring a qualitative approach (focused more on cases, history, and culture, and emphasizing depth over breadth) (see Chapter 6 for more details). More differences emerged as rational choice approaches began to win support within the sub-field, further promoting the use of mathematical modelling. The divisions reached a point in the late 1990s and early 2000s where there was something of a rebellion among American political scientists against what they described as the ‘math-ematicization of political science’, and the particular marginalization of comparative politics. An informal ‘Perestroika movement’ emerged that pressed for multiple methods and approaches, and for new efforts to broaden political science in search of greater relevance (Monroe, 2005).

Grand theory: A broad and abstract form of theorizing that incorporates many other theories and tries to explain broad areas of a discipline rather than more concrete matters.

FIGURE 5.1: Theoretical approaches to comparative politics

The last 30 to 40 years have seen both a dramatic increase in interest in comparative politics and new efforts to make it more systematic. But the development of theories of comparative politics has lagged behind, more often borrowing from other sub-fields of political science – or even other subjects entirely – than developing its own distinctive approaches. The importance of institutions has been a consistent theme throughout, but behaviouralism was inspired by the natural sciences, structuralism is influenced by history, rational choice approaches came out of economics, and interpretive approaches owe something to sociology. And in spite of decades of hard work, it is hard to find theories that have both won general support and produced lasting results.

Consider, for example, the critical question of what causes democratization. Finding an answer might be considered the Holy Grail of political research; armed with such knowledge, we might be able to reproduce the conditions needed and move the world more rapidly and sustainably towards a democratic future. But in her review of research on the question, Geddes (2007) is only able to point to some tendencies and to rule out others: richer countries are more likely to be democratic (but development does not cause democratization, although modernization might), as are countries that were once British colonies, but reliance on oil reduces the chances, as does having a large Muslim population. And every one of these arguments has been challenged. ‘Given the quality and amount of effort expended on understanding democratization’, Geddes concludes,‘it is frustrating to understand so little.’

The most recent problem identified with theories of comparative politics (and of politics and government in general) is their long history of association with Western ideas. This was a phenomenon noted by Parel (1992) when he argued that the scholarship of political theory was so focused on Western political thought that there was a prevailing assumption that modern Western texts were ‘products of universal reason itself ’. But he also argued that Western claims of universality were being questioned by other cultures, and argued that comparative political philosophy meant taking an approach that paid more attention to cultural and philosophical pluralism. This point was later taken up by Dallmayr (1999):

Only rarely are practitioners of political thought willing (and professionally encouraged) to transgress the [Western] canon and thereby the cultural boundaries of North America and Europe in the direction of genuine comparative investigation.

The sub-field of comparative politics today is broader and more eclectic than ever before, with new concepts and ideas regularly shaking up old assumptions. But it has sometimes been slow to catch up with the evolving realities of government and politics around the world, including the changing role of the state, the rise of new economic powers, the impact of new technology and globalization, the new political role of Islam, and the impact of failed and failing states. The changes within the sub-field have been positive and productive, and it employs a greater diversity of approaches than before, but much remains to be done.

The institutional approach

The study of governing institutions is a central purpose of political science in general, and of comparative politics in particular; hence the mantra often seen in studies of politics that ‘institutions matter’. Institutionalism provides the original foundation of the discipline and lies at the core of the discipline, and of this book.

Institutions: In the political sense, these are formal organizations or practices with a political purpose or effect, marked by durability and internal complexity.The core institutions are usually mandated by the constitution.

Institutionalism: An approach to the study of politics and government that focuses on the structure and dynamics of governing institutions.

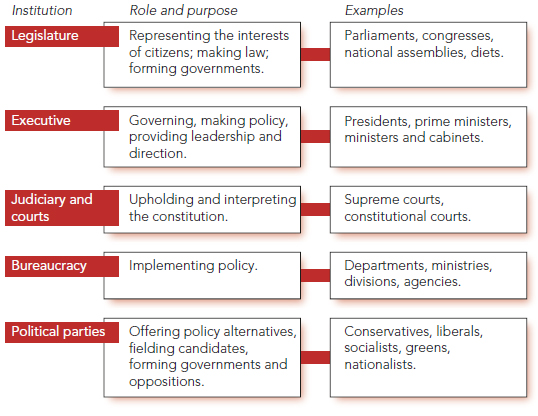

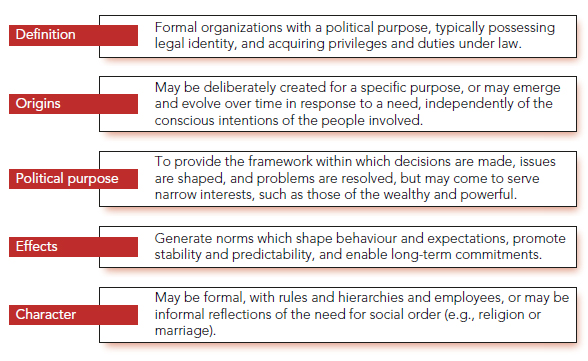

What, then, is an institution? In politics, the term traditionally refers to the major organizations of national government, particularly those specified in the constitution such as the legislature, the judiciary, the executive, and, sometimes, political parties (see Figure 5.2). Since they often possess legal identity, acquiring privileges and duties under law, these bodies are treated as literal ‘actors’ in the political process. However, the concept of an institution is also used more broadly to include other organizations which may have a less secure constitutional basis, such as the bureaucracy and local government. It is also used more widely to denote virtually any organization (such as interest groups) or even any established and well-recognized political practice. For instance, scholars refer to the ‘institutionalization’ of corruption in Russia or Nigeria, implying that the abuse of public office for private gain in these countries has become an accepted routine of political life – an institution – in its own right. When the concept of an ‘institution’ is equated with any and every political or social practice, however, it risks over-extension (Rothstein, 1996).

Institutional analysis assumes that positions within organizations matter more than the people who occupy them. This axiom enables us to discuss roles rather than people: presidencies rather than presidents, legislatures rather than legislators, the judiciary rather than judges. The capacity of institutions to affect the behaviour of their members means that politics, as other social sciences, is more than a branch of psychology.

Institutional analysis can be static, based on examining the functioning of, and relationships between, institutions at a given moment. But writers within this approach show increasing interest in institutional evolution and its effects. Institutions possess a history, culture and memory, frequently embodying traditions and founding values. In a process of institutionalization, they grow ‘like coral reefs through slow accretion’ (Sait, 1938: 18). In this way, many institutions thicken naturally over time, developing their internal procedures and also becoming accepted by external actors as part of the governing apparatus. In other words, the institution becomes a node in a network and, in so doing, entrenches its position.

Institutionalization: The process by which organizations build stability and permanence. A government department, for example, is institutionalized if it possesses internal complexity, follows clear rules of procedure, and is clearly distinguished from its environment.

FIGURE 5.2: The formal institutions of government

As particular institutions come to provide an established and accepted way of working, they acquire resilience and persistence (Pierson, 2004). For example, uncertainty abounded in 1958 when France adopted a new constitution with a semi-presidential system of government, greatly strengthening the powers of the executive relative to those of the legislature. Just a generation later, though, it would have been hard to find anyone favouring a switch back to the inefficiencies and uncertainties of the old parliamentary system. So, as with constitutions, institutions are devices through which the past constrains the present. Thus, the study of institutions is the study of political stability, rather than change. As Orren and Skowronek (1995: 298) put it:

Institutions are seen as the pillars of order in politics, as the structures that lend the polity its integrity, facilitate its routine operation and produce continuity in the face of potentially destabilizing forces. Institutional politics is politics as usual, normal politics, or a politics in equilibrium.

Institutions are particularly central to the functioning of liberal democracies, because they provide a settled framework for reaching decisions, In addition, they enable long-term commitments which are more credible than those of any single employee, thus building trust. For example, governments can borrow money at lower rates than are available to individual bureaucrats. Similarly, a government can make credible promises to repay its debt over a period of generations, a commitment that is beyond the reach of any individual debtor.

Institutions also offer predictability.When we visit a government office, we do so with expectations about how the members of staff will behave, even though we know nothing about them as individuals. A shared institutional context eases the task of conducting business between strangers. In and beyond politics, institutions help to glue society together, extending the bounds of what would be possible for individuals acting alone.

At the same time, an institutional approach, like all others, can become inward-looking. Two particular problems should be highlighted. First, some institutions are explicitly created to resolve particular problems. For example, in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007–10, and of the debt crisis that broke in the eurozone in 2009, European Union governments agreed to create new institutions designed to improve financial supervision and to encourage more consistent regulation of banking.We should perhaps focus more on these key historical moments which spark institutional creativity. Although uncommon, they help us to view institutions as a product of, rather than just an influence on, political action by individuals.

Second, governing institutions rarely act independently of social forces, especially in poorer, less complex, and authoritarian states. Sometimes, the president is the presidency, and the entire superstructure of government is a facade behind which personal networks and exchanges continue to drive politics. In the extreme case of communist party states, for instance, the formal institutions of government were controlled by the ruling party. Government was the servant, not the master, and its institutions carried little independent weight.

Even in liberal democracies, it is always worth asking whose interests benefit from a particular institutional set-up. Just as an institution can be created for specific purposes, so too can it survive by serving the interests of those in charge. For example, the arrangement in the United States by which electoral districts are designed by the dominant political parties in each state, allowing them to manipulate the outcome of elections in a process known as ‘gerrymandering’, is a distortion of democracy, but it suits the interests of the Republicans and the Democrats. In addressing the collective benefit that institutions deliver, we should remember that the support of powerful political and economic interests provides additional stability (Mahoney and Thelen, 2010: 8).

Overall, the institutions of government must be seen as central to liberal democratic politics, and we must look not just at their definition and origins, but also at their purpose, effects, and character (see Figure 5.3). They are the apparatus through which political issues are shaped, processed, and sometimes resolved. They provide a major source of continuity and predictability, and they shape the environment within which political actors operate and, to an extent, structure their interests, values, and preferences. The institutional approach offers no developed theory but does provide observations about institutional development and functioning which can anchor studies of specific cases.

New institutionalism

The manner in which theories and approaches tend to go in and out of fashion (or, at least, to evolve) is reflected in what happened to institutionalism in the 1950s and 1960s, when new approaches such as behaviouralism won support. The institutional approach was criticized for being too descriptive and for looking at the formal rules of government at the expense of politics in its many different forms, and fell out of favour. But then the 1980s saw new research on social and political structures and a new interest in the reform of institutions in developing countries. The result was the birth of what became known as new institutionalism (March and Olsen, 1984).

FIGURE 5.3: Understanding political institutions

New institutionalism: A revival of institutionalism that goes beyond formal rules and looks at how institutions shape decisions and define interests.

This looks not just at the formal rules of government but also at how institutions shape political decisions, at the interaction of institutions and society, and at the informal patterns of behaviour within formal institutions. This lent itself well to comparative politics as researchers undertook cross-national studies, many of them interested in better understanding the process of democratization. Revealing just how many variations there can be on a theoretical theme, Peters (1999) identifies seven strands of new institutionalism, ranging from the historical to the international and the sociological.

The institutional approach offers two main reasons for supposing that organizations shape behaviour. First, because institutions provide benefits and opportunities, they shape the interests of their staff. As soon as an organization pays salaries, its employees acquire interests, such as ensuring their own personal progress within the structure and defending their institution against outsiders. March and Olsen (1984: 738) suggest that institutions become participants in the political struggle:

The bureaucratic agency, the legislative committee and the appellate court are arenas for contending social forces but they are also collections of standard operating procedures and structures that define and defend interests.They are political actors in their own right.

Second, sustained interaction among employees encourages the emergence of an institutional culture, which can weld the organization into an effective operational unit. Institutions generate norms which, in turn, shape behaviour. One strength of the institutional approach is this capacity to account for the origins of interests and cultures, rather than just taking them for granted. As Zijderveld writes (2000: 70), ‘institutions are coercive structures that mould our acting, thinking and feeling’.

The new institutional approach suggests that much political action is best understood by reference to the contrasts between the logic of appropriateness and the logic of consequences. The former sees human action as driven by the rules of appropriate behaviour, and hence institutions shape activity simply because it is natural and expected, not because it has any deeper political motive. For instance, when prime ministers visit an area devastated by floods, they are not necessarily seeking to direct relief operations, or even to increase their public support, but may just be doing what is expected in their job. In itself, the tour achieves the goal of meeting expectations arising from the actor’s institutional position. ‘Don’t just do something, stand there’, said Ronald Reagan, a president with a fine grasp of the logic of appropriateness. When an institution faces an obligation to act, its members are as likely to be heard asking ‘What did we do the last time this happened?’ as ‘What is the right thing to do in this situation?’They seek a solution appropriate for the organization and its history.

Logic of appropriateness: The actions which members of an institution take to conform to its norms. For example, a head of state will perform ceremonial duties because it is an official obligation.

Logic of consequences: The actions which members of an institution take on the basis of a rational calculation of altruism or self-interest.

This emphasis within the institutional framework on the symbolic or ritual aspect of political behaviour contrasts with the view of politicians and bureaucrats as rational actors who define their own goals independently of the organization they represent. In other words, their actions are shaped by consequences, or the political returns they expect to achieve from those actions; they are faced with a problem, they look at the alternatives and at their personal values, and they choose the option that provides the most efficient means to achieving their goals. In short, institutions provide the rules of the game within which individuals pursue their objectives (Shepsle, 2006).

One of the more important debates in political research concerns the differences between empirical and normative perspectives; one uses facts to ask what happened and why (descriptive), while the other uses judgements or prescriptions to ask what should have happened or what ought to happen (evaluative) (see Gerring and Yesnowitz, 2006). Take electoral systems, for example: the statement that ‘proportional representation encourages multi-party systems’ is empirical, while the statement that ‘proportional representation should be used to encourage multiple parties’ is normative.

Most political research tries to be empirical in the sense that it asks why things are the way they are in a manner that tries to be value-neutral, as when a researcher looks into the causes of war in a purely objective and scientific fashion. But other research takes a more normative approach by asking what should be done in order to achieve a desired outcome, such that the researcher questions the phenomenon of war in a more value-driven and philosophical manner, asking – for example – whether and in what circumstances war is ever justified.

The empirical and normative approaches are not mutually exclusive, and there has been renewed demand for the idea of making political science more relevant by combining the two. Consider the argument made by Gerring and Yesnowitz (2006):

Empirical study in the social sciences is meaningless if it has no normative import … It matters, or may matter, but we do not know how. Likewise, a normative argument without empirical support may be rhetorically persuasive or logically persuasive, but it will not have demonstrated anything about the world out there. It has no empirical ballast. Good social science must integrate both elements; it must be empirically grounded, and it must be relevant to human concerns.

Many of the towering figures in the history of political thought trod lightly between the two perspectives, the cases of Machiavelli and Marx illustrating this point:

• Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) was a writer and historian whose masterpiece The Prince looked at the qualities of power and the means used by rulers to win, keep, and manipulate it. On the one hand, his book can be seen as an empirical (and even cynical) analysis of the nature and exercise of power in the real world. On the other hand, it can also be understood as normatively endorsing the sometimes brutal tactics rulers need to, or indeed should, follow to sustain their position.

• Karl Marx (1818–83) wrote a vast body of empirical work presenting history as a class struggle between the owners of the means of production and the labourers, arguing that states were run in the interests of the owners. He concluded that capitalism created internal tensions which ensured that it was sowing the seeds of its own inevitable destruction. But underlying this empirical analysis was a normative concern to accelerate capitalism’s overthrow so as to create the possibility of a new classless society. In Marx’s work, empirical research was motivated by normative goals.

Empirical: Conclusions or inferences based on facts, experience or observation.

Normative: Reaching judgements and prescriptions about what ought to be done.

The behavioural approach

The major problem faced by political science in its early decades was the doubt that it was a science at all (Dahl, 1961b). This began to change in the 1960s as the theoretical focus moved away from institutions and towards individual behaviour, particularly in American political science; in other words, there was a switch from electoral systems to voters, from legislatures to legislators, and from presidencies to presidents. The central tenet of behaviouralism was that ‘people matter’, meaning not specific people so much as the individual as the level or unit of analysis.The aim was to use scientific methods to develop generalizations about political attitudes and behaviour by studying what people actually do, rather than studying constitutions, institutions and organizational charts. Rather than implying an exclusive concern with action, the word behaviour expressed a focus on observable political reality, rather than official discourse; on individuals rather than institutions; and on scientific explanation rather than the loose descriptions of the institutionalists.

Behaviouralism: An approach to the study of politics that emphasizes people over institutions, studying the attitudes and behaviour of individualsin search of scientific generalizations.

The shift can be traced back to the work of the political scientist Charles Merriam at the University of Chicago in the 1920s. He argued the importance of moving beyond the study of formal rules and looking at the behaviour of individuals, but his ideas took some time to become more widely adopted. In part, the eventual shift grew out of the influence of decolonization. In newly independent states, government institutions proved to be of little moment as presidents, and then ruling generals, quickly dispensed with the elaborate constitutions written at independence. A fresher and wider approach – one rooted in social, economic, and political realities, rather than constitutional fictions – was needed to understand politics in the developing world.

In the United States, meanwhile, the post-war generation of political scientists was keen to apply innovative social science techniques developed during the Second World War – notably, interview-based sample surveys of ordinary people. In this way, the study of politics could be presented as a social science and become eligible for research funds made possible by that designation. The study of legislatures, for example, moved away from formal aspects (e.g. the procedures by which a bill becomes law) towards legislative behaviour (e.g. how members defined their job). Researchers delved into the social backgrounds of representatives, their individual voting records, their career progression, and their willingness to rebel against the party line.

Similarly, scholars who studied judiciaries began to take judges, rather than courts, as their unit of analysis, using statistical techniques to assess how the social background and political attitudes of judges shaped their decisions and their interpretations of the constitution. This level of inquiry tended to focus on ‘the backgrounds, attitudes and ideological preferences of individual justices rather than on the nature of the Court as an institution and its significance for the political system’ (Clayton and Gillman, 1999: 1). In fact, the institutional setting was often just taken for granted.

Although the behavioural approach could target elites, it earned its spurs in the study of ordinary people. Survey analysis yielded useful generalizations about voting behaviour, political participation and public opinion. Unlike institutional analysis of government, these studies located politics in its social setting, showing – for example – how race and class impinged on whether, how, and to what extent people took part in politics. In this way, the behavioural revolution broadened our outlook.

The behavioural approach provided the research foundation for several chapters in this book. There have been ‘few areas in political science’, claim Dalton and Klingemann (2007: vii), ‘where scholarly knowledge has made greater progress in the past two generations’.Yet, as a model for the entire discipline, the behavioural revolution eventually ran its course. Its focus on individual political behaviour took the study of politics away from its natural concern with the institutions of government. Its methods became more technical and its findings more specialized.

Behaviouralism produced a political science with too much science and too little politics. Amid the political protests of the late 1960s, behaviouralists were criticized for fiddling while Rome burned. Rather like the institutional approach before it, behaviouralism seemed unable to address current political events. The strategy of developing generalizations applying across space and time was ill-suited to capturing the politics of any particular moment. In short, the research programme had become orthodox, rather than progressive; it was time for something new.

The structural approach

Structuralism is an approach to political analysis that focuses on relationships among parts rather than the parts themselves. In other words, it involves examining the ‘networks, linkages, interdependencies, and interactions among the parts of some system’ (Lichbach and Zuckerman, 1997: 247). The central tenet here is that ‘groups matter’, in the sense that the structural approach focuses on powerful groups in society, such as the bureaucracy, political parties, social classes, churches, and the military. These groups possess and pursue their own interests, creating a set of relationships which forms the structure underpinning or destabilizing the institutional politics of parties and government. Each group within the structure works to sustain its political influence in a society which is always developing in response to economic change, ideological innovations, international politics and the effects of group conflict itself. It is this framework which undergirds, and ultimately determines, actual politics, because human actions are shaped by this bigger structural environment.

Structuralism: An approach to the study of politics that emphasizes the relationships among groups and networks within larger systems.The interests and positions of these groups shape the overall configuration of power and provide the dynamic of political change.

A structure is defined by the relationships between its parts, with the parts themselves – including their internal organization and the individuals within them – being of little interest. As Skocpol (1979: 291) put it, structuralists ‘emphasize objective relationships and conflicts among variously situated groups and nations, rather than the interests, outlooks, or ideologies of particular actors’. For example, the relationship between labour and capital is more important than the internal organization or the leaders of trade unions and business organizations. The assumption is that capital and labour will follow their own real interests, regardless of who happens to lead the organizations formally representing their concerns. Individuals are secondary to the grand political drama unfolding around them.

But real interests and social actors are, of course, terms imposed by the researcher.Who is to say where a group’s true interests lie? How can we refer to the ‘actions’ of a group, rather than a person? In execution, the structural approach is broad-brush, making large if plausible assumptions about the nature of conflict in a particular society and using them to make inferences about causes without always paying great attention to the detailed historical record.

We can draw a clear contrast between structuralism and the cultural analysis covered in Chapter 12. While, for example, a structural explanation of poverty would emphasize the contrasting interests and power positions of property-owners and the working class, a cultural analysis would place more weight on the values of poor people themselves, showing how, for example, limited aspirations trap the poor in a cycle of poverty that can persist across generations. For the structuralist, the important factor is the framework of inequality, not the values that confine particular families to the bottom of the hierarchy. This point, and the overall thrust of structuralism, is summarized by Mahoney (2003: 51):

At the core of structuralism is the concern with objective relationships between groups and societies. Structuralism holds that configurations of social relations shape, constrain and empower actors in predictable ways. Structuralism generally downplays or rejects cultural and value-based explanations of social phenomena. Likewise, structuralism opposes approaches that explain social outcomes solely or primarily in terms of psychological states, individual decision-making processes, or other individual-level characteristics.

The best-known structural work in politics has adopted an explicitly historical style, seeking to understand how competition between powerful groups over time leads to specific outcomes such as a revolution, democracy, or a multi-party system.The authors of such studies argue that politics is about struggle rather than equilibrium, and they favour comparative history, giving us another contrast with the non-historical generalizations favoured by behaviouralists and the sometimes static descriptions of the institutionalists.

One of the leading figures in the field – who not only exemplifies the structural approach but helped to define it – was the American sociologist Barrington Moore. His 1966 book Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World did more than any other to shape this format of historical analysis of structural forces. In trying to understand why liberal democracy developed earlier and more easily in France, Britain, and the United States than in Germany and Japan, he suggested that the strategy of the rising commercial class was the key. In countries such as Britain, where the bourgeoisie avoided entanglement with the landowners in their battles with the peasants, the democratic transition was relatively peaceful. But where landlords engaged the commercial classes in a joint campaign against the peasantry, as in Germany, the result was an authoritarian regime which delayed the onset of democracy.

Although later research qualified many of Moore’s judgements, his work showed the value of studying structural relationships between groups and classes as they evolve over long periods (Mahoney, 2003). He asked important comparative questions and answered them with an account of how and when class relationships develop and evolve.

The structural approach asks big questions and, by selecting answers from the past, it interrogates history without limiting itself to chronology. Many authors working in this tradition make large claims about the positions adopted by particular classes and groups; specifically, interests are often treated as if they were actors, leading to ambitious generalizations which need verifi-cation through detailed research. Even so, the structural approach, in the form of comparative history, has made a distinctive contribution to comparative politics.

The rational choice approach

Like behaviouralism, rational choice approaches are focused on people, but instead of examining actions they try to explain the calculations behind those actions. They argue that politics consists of strategic interaction between individuals, with all players seeking to maximize the achievement of their own particular goals.The central tenet here is that objectives matter.The assumption is that people ‘are rational in the sense that, given goals and alternative strategies from which to choose, they will select the alternatives that maximize their chances of achieving their goals’ (Geddes, 2003: 177). Where behaviouralists aim to explain political action through statistical generalization, the rational choice approach focuses on the interests of the actors. And where the structural perspective is rooted in historical sociology, the rational choice approach comes out of economics.

Rational choice: An approach to the study of politics based on the idea that political behaviour reflects the choices made by individuals working to maximize their benefits and minimize their costs.

The potential value of rational choice analysis lies in its ability to model the essentials of political action, and hence make predictions, without all-encompassing knowledge of the actors.We simply need to identify the goals of the actors and how their objectives can best be advanced in a given situation.Then, we can predict what they will do. All else, including the accounts actors give of their own behaviour, is detail. The aim is to model the fundamentals of human interaction, not to provide a rich account of human motives.

Neither are rational choice analysts concerned to provide an accurate account of the mental process leading to decisions; the test is whether behaviour is correctly predicted. The underlying philosophy – that explanation is best sought in models that are both simple and fundamental – is a distinctive feature of the approach, reflecting its origins in economics. More than any other approach, the rational choice approach values parsimonious explanations. To appreciate the style of rational choice thinking, it is crucial to recognize how simplifying assumptions can be seen as a strength in building models and generating predictions.

What goals can people pursue within the rational choice framework? Most analysts adopt the axiom of self-interest. This was defined long ago by John C. Calhoun, the American politician and one-time vice president, in his Disquisition on Government (1851) as the assumption that each person ‘has a greater regard for his own safety or happiness, than for the safety or happiness of others: and, where they come into opposition, is ready to sacrifice the interests of others to his own’.

At the cost of increased complexity, we can broaden the range of goals.We can imagine that people take satisfaction from seeing others achieve their ends, or we can even permit our subjects to pursue altruistic projects.Yet, just as markets are best analysed by assuming self-interest among the participants, so too do most rational choice advocates believe that the same assumption takes us to the essence of politics. As Hindmoor (2010: 42) puts it, ‘if people are rational and self-interested it becomes possible to explain and even predict their actions in ways that would allow rational choice theorists to claim a mantle of scientific credibility’.

Rational choices are not necessarily all-knowing. Operating in an uncertain world, people need to discount the value of going for a goal by the risk they will fail to achieve it. In situations of uncertainty, they may prefer to eliminate the risk of a bad outcome, rather than go for broke by staking all on a single bet. Thus, a rational choice needs to be distinguished from a knowledgeable one.

Consider, for example, the task of working out which party to vote for. As voters, we might well find that the cost of research on all the candidates exceeds the benefits gained, leading us to use shortcuts such as relying on expert opinion. It is not always rational to be fully informed, a fact that brings the approach closer to the real world. However, the full rational model – the version which allows us to predict most easily – assumes that actors are knowledgeable as well as rational and self-interested.

In the study of politics, the rational choice framework is often extended from the individual to the larger units that are most often studied by comparativists. So rational choice analysts sometimes apply their techniques to political parties and interest groups, treating them as if they were individuals. In his analysis of political parties, for example, Downs (1957: 28) imagined that all party members ‘act solely in order to attain the income, prestige, and power which come from being in office’. For ease of analysis, he treated parties as if they were unitary actors, in the same way that students of international politics often regard states. In both cases, the aim is accurate prediction, not a detailed reconstruction of the actual decision process.

A major contribution of the approach lies in highlighting collective action problems. These arise in coordinating the actions of individuals so as to achieve the best outcome for each person. For instance, many people persist in living a polluting lifestyle, arguing that their behaviour will make no decisive difference to overall environmental quality.Yet, the outcome from everyone behaving in this way is climate change that is damaging to all. In other words, individual rationality leads to a poor collective result.

Collective action problem: Arises when rational behaviour by individuals produces a negative overall outcome.The issue typically arises when people seek to free ride on the efforts of others in providing public goods.

Similarly, during the global financial crisis, many investment bankers made high-risk investments in order to increase their bonuses; their employers, too, were happy enough as long as their corporate profits continued to grow.When these investments eventually turned bad, the effect was a problem not only for the original investors, but also – and more importantly – a threat to the stability of the Western financial system. Clearly, some form of coordination is needed if private actions are to be made compatible with desirable collective outcomes – in this case, governments imposed stricter regulation of banks by governments. More than any other framework, the rational choice approach encourages to us to recognize that individual preferences and collective outcomes are two different things; a government is needed to bridge the gap.

Paradoxically, the rational choice approach can be useful even when it is inaccurate. Its value lies not merely in the accuracy of its predictions, but also in identifying what appears to be irrational behaviour. If people behave in a surprising way, we have identified a puzzle in need of a solution. Perhaps we have misunderstood their preferences, or the situation confronting them. Or perhaps their actions really are irrational. At the international level, Government A might judge that Government B’s interests lie in pursuing policy X. If Government B actually adopts policy Y, then Government A has some thinking to do. Has it misunderstood B’s goals, or has B simply made a mistake?

Yet the rational choice approach, as any other, takes too much for granted. It fails to explain the origins of the goals that individuals hold; it is here, in understanding the shaping of preferences, that society re-enters the equation. Our aspirations, our status, and even our goals emerge from our interactions with others, rather than being formed beforehand. Certainly, we cannot take people’s goals and values as given.

Also, since the rational choice approach is based on a universal model of human behaviour, it has limited relevance in understanding variation across countries. Just as individual goals are taken for granted, so too should be the different national settings which determine the choices available to individuals and within which they pursue their strategies. Still, even though the rational choice approach does not always generate accurate predictions, it provides one lens, among several, for analysing political processes.

The interpretive approach

The focus of the interpretive approach is on the interpretations within which politics operates, including assumptions, codes, constructions, identities, meanings, norms, narratives, and values. In other words, people do some things and avoid others because of the presence of social constructs that filter the way they see the world (hence the approach is also sometimes known as ‘constructivism’). This approach takes us away from the behaviouralist search for scientific laws and towards a concern with the ideas of individuals and groups, and how their constructs define and shape political activity. The starting point is that we cannot take the actor’s goals and definition of the situation for granted, as the rational actor approach does; instead, we must look at the way those goals and definitions are constructed.

Interpretive approach: An approach to the study of politics based on the argument that politics is formed by the ideas we have about it.

In its strongest version, the interpretive approach argues that politics consists of the ideas participants hold about it. There is no political reality separate from our mental constructions, and no reality which can be examined to reveal the impact of ideas upon it. Rather, politics is formed by ideas themselves. In short, ‘ideas matter’ and there is nothing but ideas.

In a more restrained version, the argument is not that ideas comprise our political world but, rather, that they are an independent influence upon it, shaping how we define our interests, our goals, our allies, and our enemies. We act as we do because of how we view the world; if our perspective differed, so would our actions. Where rational choice analysis focuses on how people go about achieving their individual objectives, the inter-pretivist examines the framing of objectives themselves and regards such interpretations as a property of the group, rather than the individual (hence interpretivists take a social rather than a psychological approach).

Because ideas are socially constructed, many interpretivists imagine that we can restructure our view of the world and, so, the world itself. For instance, there is no intrinsic reason why individuals and states must act (as rational choice theorists imagine) in pursuit of their own narrow self-interests. To make such an assumption is to project concepts onto a world that we falsely imagine to be independent of our thoughts. Finnemore (1996: 2), for example, suggests that interests ‘are not just “out there” waiting to be discovered; they are constructed through social interaction’. Also, ideas come before material factors because the value placed on material things is itself an idea (although Marxists and others would disagree).

For example, states are often presented as entities existing independently of our thoughts. But the state is not a physical entity such as a building or a mountain; it is an idea built over a long period by political thinkers, as well as by practical politicians. Borders between blocs of land were placed there not by nature but by people. There are no states when the world is viewed from outer space, as astronauts frequently tell us. Or, more accurately, the maps construct their own reality. It is this point Steinberger (2004) has in mind when he says that his idea of the state is that the state is an idea. True, the consequences of states, such as taxes and wars, are real enough, but these are the effects of the world we have made, and can remake.

Similarly, the class relationships emphasized by the structuralists, and the generalizations uncovered by the behaviouralists, are based not on physical realities but on interpretations that can, in principle, be changed. For instance, a behavioural observation about the under-representation of women in legislatures can generate a campaign that leads to an increase in the number of legislators who are women, thus altering the observation itself.

For this reason, interpretivists often focus on historical narratives, examining how understandings of earlier events influence later ones.Take the study of revolutions as an example. Where behaviouralists see a set of cases (French, Russian, Iranian, and so on) and seek common causes of events treated as independent, interpretivists see a single sequence and ask how later examples (such as the Russian Revolution) were influenced by the ideas then held about earlier revolutions (such as the French). Alternatively, take the study of elections. The meaning of an election is not given by the results themselves but by the narrative that the political class later establishes about it: for example, ‘the results showed that voters will not tolerate high unemployment’ (see Chapter 17 for more about this).

Parsons (2010: 80) provides a useful definition of the interpretive approach:

People do one thing and not another due to the presence of certain ‘social constructs’: ideas, beliefs, norms, identities or some other interpretive filter through which people perceive the world. We inhabit ‘a world of our making’ (Onuf, 1989) and action is structured by the meanings that particular groups of people develop to interpret and organise their identities, relationships and environment.

The interpretive approach sees the task of explanation as that of identifying the meaning which itself helps to define action.The starting point is not behaviour but action – that is, meaningful behaviour. Geertz (1973: 5) argues that, since we are suspended in webs of meaning that we ourselves have spun, the academic study of social and political affairs cannot be a behavioural science seeking laws but must instead be an interpretive one seeking meaning. Wendt (1999: 105) further illustrates this notion of explanation through meaning:

If we want to explain how a master can sell his slave then we need to invoke the structure of shared understandings existing between master and slave, and in the wider society, that makes this ability to sell people possible.This social structure does not merely describe the rights of the master; it explains them, since without it those rights by definition could not exist.

In politics, as in other disciplines concerned with groups, most interpretivists consider how the meanings of behaviour form, reflect, and sustain the traditions and discourses of a social group or an entire society. The concern is social constructs, rather than just the specific ideas of leaders and elite groups. For example, by acting in a world of states – where we apply for passports, support national sports teams, or just use the word citizen – we routinely reinforce the concept of the state. By practising statehood in these ways, as much as by direct influence through education and the media, the idea itself is socially reinforced or, as is often said, ‘socially constructed’. These understandings can also be socially contested (‘Why should I need a visa each time I visit this country?’), leading to gradual changes in the ideas themselves.

There is a clear and useful lesson here for students of politics, and of comparative politics especially. When we confront a political system for the first time, our initial task is to engage in political anthropology: to make sense of the activities that comprise the system. What are the moves? What do they mean? What is the context that provides this meaning? And what identities and values underpin political action? Behaviour which has one meaning in our home country may possess a different significance, and constitute a different action, elsewhere. For example, offering a bribe may be accepted as normal in one place, but be regarded as a serious offence in another. Casting a vote may be an act of choice in a democracy, but of subservience in a dictatorship. Criti-cizing the president may be routine in one country, but sedition in another. Because the recognised consequences of these acts vary, so does their meaning.

FOCUS 5.2 The interpretive approach: mass killings and genocide

As an example of the independent impact of ideas in politics, consider the book Final Solutions, Benjamin Valentino’s prize-winning 2004 study of mass killing and genocide in the twentieth century. Valentino suggests that the mass murder of civilians is a product of the ideas of the instigators, designed to accomplish their most important ideological and political objectives (2004: 67). Valentino is a student of elite ideas, which he takes to include both goals and assessments of how to achieve them; he is less concerned with structural relationships or government institutions:

To identify societies at high risk for mass killing, we must first understand the specific goals, ideas and beliefs of powerful groups and leaders, not necessarily the broad social structures or systems of government over which these leaders preside. (p. 66)

Valentino contends that ‘mass killing occurs when powerful groups come to believe it is the best available means to accomplish certain radical goals, counter specific types of threat or solve difficult military problems’ (p. 66). Unlike rational choice thinkers, he does not assume that politicians are accurate in their perceptions of their environment. Their understandings are what matter, even if these are misunderstandings:

An understanding of mass killing does not imply that perpetrators always evaluate objectively the problems they face in their environment, nor that they accurately assess the ability of mass killings to resolve these problems. Human beings act on the basis of their subjective perceptions and beliefs, not objective results. (p. 67)

But it is not just ideas and perceptions that are Valentino’s concern. Rather, he examines how leaders are driven by actual and perceived changes in the political environment to regard mass killing as the final solution for achieving their ends. Thus, his approach is not purely interpretive but, instead, consists of a fruitful examination of the interaction over time between political realities, on the one hand, and elite ideas and perceptions, on the other.

Valentino carries through his interest in ideas to a consideration of how we can best prevent future occurrences of mass killing. He rejects the relevance of behavioural and structural generalizations suggesting that mass killings only occur in dictatorships or war. Rather, he suggests that leaders in any type of structure or political system may come to see mass killing as the best, most effective or sole method of achieving their goals. Effective prevention therefore requires us to return once more to leaders’ ideas: ‘if we hope to anticipate mass killing, we must begin to think of it in the same way its perpetrators do’ (p. 141).

So far, so good. Yet, in studying politics we want to identify patterns that abstract from detail; we seek general statements about presidential, electoral, or party systems which go beyond the facts of a particular case. We want to examine relationships between such cat-egories so as to discover overall associations. We want to know, for instance, whether a plurality electoral system always leads to a two-party system. Through such investigations we can acquire knowledge which goes beyond the understandings held by the participants in a particular case.

We must recognize, also, that events have unintended consequences: the Holocaust was certainly a product of Hitler’s ideas, but its effects ran far beyond his own intentions. With its emphasis on meaning, an interpretive approach misses the commonplace observation that much social and political analysis studies the unintended consequences of human activity. In short, unpacking the meaning of political action is best regarded as the start, but not the end, of political analysis. It provides a practical piece of advice: we must grasp the meaning of political behaviour, thus enabling us to compare like with like.Yet, it would be unsatisfactory to regard a project as complete at this preliminary point.

Compared with the other approaches reviewed in this chapter, the interpretive approach remains more aspiration than achievement. Some studies conducted within the programme focus on interesting but far-away cases when meanings really were different: when states did not rule the world; when lending money was considered a sin; or when the political game consisted of acquiring dependent followers, rather than independent wealth.

Yet, such studies do little to confirm the easy assumption that the world we have made can be easily dissolved. As the institutionalists with whom we began this chapter are quick to remind us, most social constructs are social constraints, for institutions are pow-erfully persistent. Our ability to imagine other worlds should not bias how we go about understanding the world as it is.

• Why is there so much disagreement among political scientists (or comparativists) about the best theoretical approach, and why are grand theories so elusive?

• How far can we understand politics and government by focusing only – or mainly – on institutions?

• Which matter more to an understanding of government and politics: institutions or people?

• What does ‘rational’ mean and do people behave rationally?

• What inûences have been most important in shaping how you view the political world? Which of the approaches in this chapter is most useful in comparative politics?

KEY TERMS

Behaviouralism

Collective action problem

Empirical

Grand theory

Interpretive approach

Institutionalism

Institutionalization

Institutions

Logic of appropriateness

Logic of consequences

New institutionalism Normative

Rational choice

Structuralism

Theory

FURTHER READING

Boix, Carles and Susan C. Stokes (eds) (2009) The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics. A survey of the field of comparative politics, including a section on theory and methodology.

Green, Daniel M. (ed.) (2002) Constructivism and Comparative Politics. Examines the value of the interpretive approach in comparative politics.

Lichbach, Mark Irving and Alan S. Zuckerman (eds) (2009) Comparative Politics: Rationality, Culture and Structure, 2nd edn. Detailed essays on the rational, cultural, and structural approaches to compara-

Mahoney, James and Dietrich Rueschemeyer (eds) (2003) Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences. A thorough presentation of structural analysis as expressed in comparative history.

Marsh, David and Gerry Stoker (eds) (2010) Theory and Methods in Political Science, 3rd edn. Includes essays on most of the approaches introduced in this chapter.

Peters, B. Guy (2011) Institutional Theory in Political Science, 3rd edn. A survey of the different facets of institutional theory, and its potential as a para-digm for political science. tive politics.