PREVIEW

Where most institutions of government are formally outlined in the constitution, interest groups (like parties) are founded and operate largely outside these formal structures. Their goal – for those that are politically active – is to influence policy without becoming part of government.They come in several types: protective groups work in the material interests of their members, promotional groups advocate ideas and policies of a more general nature, peak associations bring together multiple like-minded groups to help them exploit their numbers, and think-tanks work to shape the policy debate through research. A vibrant interest group community is generally a sign of a healthy civil society but it can also become a barrier to the implementation of the popular will as expressed in elections.

This chapter begins with a survey of the different types of group, and the manner in which they work. It then critiques the idea of pluralism, contrasting the free marketplace of ideas with the privileged role that groups can come to play within the political process. The chapter next assesses the channels of influence used by groups before looking at the ingredients of influence and asking what gives particular groups the ability to persuade. It then looks at the distinctive qualities and effects of social movements, before assessing the place of interest groups in authoritarian regimes, where they are typically seen either as a threat to the power of the regime or as a device through which the regime can maintain its control over society.

CONTENTS

• Interest groups: an overview

• Types of interest groups

• The dynamics of interest groups

• Channels of influence

• Ingredients of influence

• Social movements

• Interest groups in authoritarian states

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • Interest groups are central to the idea of a healthy civil society. Their ability to organize and lobby government is a hallmark of liberal democracy and a condition of its effective functioning. |

| • Interest groups exert a pervasive infl uence over the details of the public policies that affect them. But groups are far from omnipotent; understanding them also requires an awareness of their limits as political actors. |

| • Pluralism, and the debate surrounding it, is a major academic interpretation of the political role of interest groups. But there are reasons to question whether the pluralist ideal is an accurate description of how groups operate in practice. |

| • Interest groups use a combination of direct and indirect channels of infl uence. Where ties with government are particularly strong, the danger arises of the emergence of sub-governments enjoying preferred access. |

| • Interest groups are often complemented by wider social movements, whose activities challenge conventional channels of participation. |

| • Where the governments of liberal democracies may be too heavily infl uenced by powerful groups, the problem can be reversed in authoritarian states. |

Interest groups – also known as ‘pressure groups’ – are bodies which seek to influence public policy from outside the formal structures of government. Examples include employer organizations, consumer groups, professional bodies, trade union federations, and single-issue groups.Traditionally, the term only covered bodies specifically created for lobbying purposes, and excluding businesses, churches, and sub-national or overseas governments. But since lobbying is pursued by many organizations whose primary focus is elsewhere, the restriction is too limiting (Scholzman, 2010). Even corporations can be seen as a form of interest group.

Interest group: A body that works outside government to influence government policy.

Like political parties, interest groups are a crucial channel of communication between society and government, especially in liberal democracies. But they pursue specialized concerns, seeking to influence government without becoming the government. They are not election-fighting organizations; instead, they typically adopt a pragmatic, low-key approach in dealing with whatever power structure confronts them, using whatever channels are legally (and occasionally illegally) available to them.

Although many interest groups go about their work quietly, their activity is pervasive.Their staff are to be found negotiating with bureaucrats over the details of proposed regulations, pressing their case in legislative committee hearings, and taking journalists out to lunch in their efforts to influence media coverage. As Finer noted decades ago, ‘their day-to-day activities pervade every sphere of domestic policy, every day, every way, at every nook and cranny of government’ (1966: 18). Without question, interest groups are central to a system of functional representation, especially on detailed issues of policy. Even so, political cultures vary in how they define the relationship between interest groups and the state.Thus groups can be seen as:

• An essential component of a free society, separate from the state.

• Partners with the state in achieving a well-regulated society.

• Providers of information and watchdogs on the performance of government.

• An additional channel through which citizens can be politically engaged.

• Promoters of elitism, offering particular sectors privileged access to government.

Interest groups are a critical part of a healthy civil society. In a liberal democracy, the limited role of government leaves space for groups and movements of all kinds to emerge and address shared problems, often without government intervention. A rich civic tradition also provides the context in which interest groups can develop their capacity to influence government, encouraged by the expectation that government will entertain competing views about the sources and effects of social problems. But some interests can become too powerful, developing an insider status with government, and compromising the principle of equal access.

Civil society: The arena that exists outside the state or the market and within which individuals take collective action on shared interests.

Types of interest group

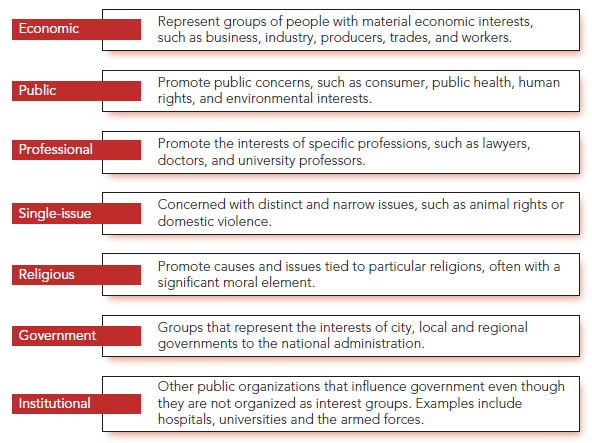

Interest groups come in many varieties, based on their size, geographical reach, objectives, methods, and influence. Many form for practical or charitable purposes rather than for political action, but develop a political dimension as they begin working either to modify public policy or to prevent unfavour-able changes. Their methods include fundraising (and spending), promoting public awareness, generating information, mobilizing their members, directly lobbying government, advising legislators, and encouraging favourable media. Their variety, in short, is so great, their methods so varied, and their overlap so considerable that it is not easy to develop a list of dis-crete types (Figure 18.1).

To simplify the list somewhat, it is helpful to distinguish between protective and promotional groups. Protective groups are perhaps the most prominent and powerful. They articulate the material interests of their members: workers, employers, professionals, retir-ees, military veterans, and so on. Sometimes known as ‘sectional’ or ‘functional’ groups, these protective bodies represent clear interests, and are well established, well connected and well resourced. They give priority to influencing government, and can invoke sanctions to help them achieve their goals: workers can go on strike, and business organizations can withdraw their cooperation with government.

FIGURE 18.1: Types of interest group

Protective group: An interest group that seeks selective benefits for its members and insider status with relevant government departments.

But protective groups can also be based on local, rather than functional, interests. Geographic groups emerge when the shared interests of people living in the same location are threatened by plans for, say, a new highway, or a hostel for ex-convicts. Because of their negative stance – ‘build it anywhere but here’ – these kinds of bodies are known as Nimby groups: not in my back yard. Collectively, Nimby groups can generate a Banana outcome: ‘build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone’. Unlike permanent functional organizations, however, Nimby groups often come and go in response to particular threats and changing levels of public interest.

A particular concern of protective groups is scrutinizing government activity; for example, by monitoring proposed regulations. A trade association will keep an eye on even the least newsworthy of developments within its zone of concern. A detailed regulation about product safety may be politically trivial but commercially vital for a group’s members. Much activity of protective groups involves technical issues of this kind.

In contrast to the more material goals of protective bodies, promotional groups advocate ideas, identities, policies, and values. Also known as ‘public interest’, ‘advocacy’, ‘attitude’, ‘campaign’ or ‘cause’ groups, such organizations do not expect to profit directly from the causes they pursue, nor do they possess a material stake in how it is resolved. Instead, they seek broad policy changes in the issues that interest them, which include consumer safety, women’s interests, the environment, or global development. These are public interests, as distinct from the narrower interests of single-issue groups.

Promotional group: An ‘interest’ group that promotes wider issues and causes than is the case with protective groups focused on the tangible interests of their members.

In liberal democracies, promotional groups have expanded in number and significance, their growth since the 1960s constituting a major trend in interest politics. However, even more than for members of political parties, many who join promotional groups are credit card affiliates only; they send donations or sign up for membership, and perhaps follow news about the issue concerned, but otherwise remain unengaged.To be sure, a financial contribution expresses the donor’s commitment, but it also delegates the pursuit of the cause to the group’s leaders and staff. For this reason, the effectiveness of promotional bodies as schools for democracy can easily be overstated (Maloney, 2009).

The boundary separating protective and promotional groups is poorly defined. For example, bodies such as the women’s and gay movements seek to influence public opinion and are often classified as promotional. However, their prime purpose remains to protect the interests of specific non-occupational groups. Perhaps they are best conceived as protective interests employing promotional means.

Protective interest groups representing a specific industry not only lobby government directly, but will often also join a peak association, or a body that consists of multiple like-minded interest groups. Their members are not individuals but other organizations such as businesses, trade associations, and labour unions. For example, industrial associations and individual corporations may join a wider body representing business interests to government, and labour unions may do the same for wider bodies representing worker interests. Examples of peaks include the National Association of Manufacturers in the United States, the Federal Organization of German Employers, and the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) in the UK. The CBI’s direct business members, and indirect members through trade associations, amount to 190,000 organizations employing around one-third of the private sector workforce.

Peak association: An umbrella organization representing the broad interests of business or labour to government.

Despite the widespread decline in union membership and labour militancy, many labour peak associations still speak with an influential voice. In 2011, the Confederation of German Trade Unions (DGB) comprised eight unions with a total of more than six million individual members. Britain’s Trades Union Congress had 52 affiliated unions in 2015, representing a comparable number of working people. Such numbers are usually enough to earn a seat at the policy table.

In seeking to influence public policy, peak associations usually succeed, because they are attuned to national government, possess a strong research capacity and talk the language of policy. For example, the DGB (2012) defines its task thus:

the DGB represents the German trade union movement in dealing with: the government authorities at state and national level; the political parties; the employers’ organisations; and other groups within society. The DGB itself is not directly involved in collective bargaining and cannot conclude pay agreements. However, it is significant for its specialist competence on broader issues of a general political nature.

TABLE 18:1: Comparing protective and promotional interest groups

| Protective | Promotional | |

| Aims | Defend an interest | Promote a cause |

| Membership | Closed: membership is restricted | Open: anyone can join |

| Status | Insider: frequently consulted by government and actively seeks this role | Outsider: consulted less often by government; targets public opinion and the media |

| Benefits | Selective: only group members benefit | Collective: benefits go to both members and non-members |

| Focus | Aim to influence national government on specific issues affecting members | Also seek to influence national and global bodies on broad policy matters |

Throughout the democratic world, the rise of pro-market thinking, international markets, and smaller service companies has restricted the standing of peak associations. Trade union membership has fallen (see later in this chapter), and the voice of business is now often expressed directly by leading companies. In addition, the task of influencing the government is increasingly delegated to specialist lobbying companies. In response to these trends, peak associations have tended to become policy-influencing and service-providing bodies, rather than organizations negotiating collectively with government on behalf of their members (Silvia and Schroeder, 2007).

Even so, extensive consultation – if no longer joint decision-making – continues between the peaks and government, not least in Scandinavia. And some smaller countries, including Ireland and the Netherlands, have even developed or revived wide-ranging agreements designed to combine social protection with improved economic efficiency. Such structured arrangements provide a contrast to the pluralist interpretation of interest groups which we discuss in the next section.

Another kind of group, often overlooked in discussions about interest politics, is the think-tank, or policy institute. These are private organizations set up to undertake research with a view to influencing both the public and the political debate. They typically pub-lish reports, organize conferences, and host seminars, all with the goal of sustaining a debate over the issues in which they are interested, and to influence government and legislators either directly or indirectly. Most think-tanks are privately funded, but some are supported by governments, political parties, or corporations, and have a clear national, corporate, or ideological agenda. Examples include the Fabian Society in Britain, the Institute for National Strategic Studies in the US, the European Policy Centre in Belgium, the Centre for Civil Society in India, and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute in Sweden.

Think-tank: A private organization that conducts research into a given area of policy with the goal of fostering public debate and political change.

The dynamics of interest groups

Debate on the role of interest groups has long centred on the concept of pluralism, or competition for influence in the political market.This is a model that regards competition between freely organized interest groups as a form of democracy. Supposedly, interest groups can represent all major sectors of society so that each sector’s interests receives political expression. Groups compete for influence over government, which acts as an arbiter rather than an initiator, an umpire rather than a player. Groups compete on a level playing field, with the state showing little bias towards one over others. As new interests and identities emerge, groups form to represent them, quickly finding a place in the house of power. Overall, pluralism depicts a wholesome process of dispersed decision-making in which government’s openness allows its policies to reflect developments in the economy and society.

Pluralism: A political system in which competing interest groups exert influence over a responsive government.

The reality of interest group dynamics is somewhat different from this ideal (see Focus 18.1), and many political scientists accept that the original pluralist por-trayal of the relationship between groups and government was one-sided and superficial (McFarland, 2010). Criticism focuses on four areas:

• Interest groups do not compete on a level playing field. Some interests, such as business, are inherently powerful, while others are less powerful, and even marginal. The result is that groups form a hierarchy of influence, with their ranking reflecting their value to government.

• Pluralism overlooks the bias of the political culture and political system in favour of some interests but against others. Groups advocating modest reforms within the established order are usually heard more sympathetically than those seeking radical change (Walker, 1991). Some interests are inherently different.

• The state is far more than a neutral umpire. In addition to deciding which groups to heed, it may regulate their operation and even encourage their formation in areas it considers important, thus shaping the interest group landscape itself.

The weaknesses in pluralist thinking are illustrated by the contrasting cases of the United States and Japan, where group access to government is unbalanced, but for different reasons. The United States is often considered as an exemplar of the pluralist model, home as it is to numerous visible, organized, competitive, well-resourced, and successful interest groups. One directory listed more than 27,000 organizations politically active in Washington DC between 1981 and 2006 (Schlozman, 2010: 431), working to influence policy at the federal, state, and local levels on a wide range of interests. The separation of powers gives interest groups several points of leverage, including congressional committees, executive agencies, and the courts.

But – charge the critics – government entrenches the interests of those who are already wealthy and powerful, including financial institutions deemed too big to fail. In 2006, more than half the groups registered in Washington DC were business interests (Schlozman, 2010: 434). The general interest often drowns in a sea of special pleading, certainly avoiding majority dictatorship, but substituting the risk of tyranny by minorities.

Japan, too, is a society that places an emphasis on group politics, and so would seem to be a natural habitat for pluralism. Many groups are indeed active, using standard tactics such as lobbying and generating public awareness. But economic groups also try to influence the political system from inside, for example by trying to secure election of their members to public office, thus blurring the line between an interest group and a political party. There has been a particularly close relationship between business and government, and more specifically between large corporations and the dominant Liberal Democratic Party. This relationship helped Japanese companies to borrow and invest, and protected emerging industries as they sought to become internationally competitive. Public policy in Japan emerges less from electoral competition and public debate than from ‘Japan Inc.’: bargaining within a form of iron triangle involving the higher levels of the governing political party (or coalition), the bureaucracy, and big business. Organized labour, meanwhile, has relatively little influence over government. The outcome of this distinctly non-pluralist pattern, it used to be said, was a rich country with poor people.

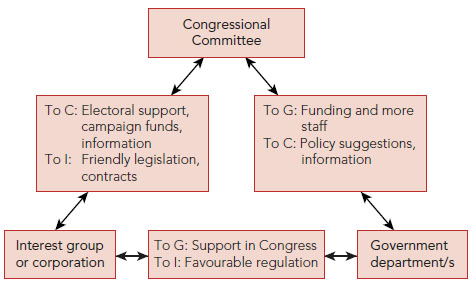

Both countries experience the problem of iron triangles though in the US, congressional committees are more important players (see Figure 18.2). In policy sectors where resources are available for distribution, legislative committees in Congress appropriate funds which are spent by government departments for the benefit of members of interest groups, which in turn offer electoral support and campaign funds for members of the committee. Perhaps most (in)famous among these triangles is the military-industrial complex of which President Eisenhower warned in his farewell address. Eisenhower described the close relationship between the US Department of Defense, the armed services committees in Congress, and the enormous defence contractors that provide most of the country’s weapons. In many sectors, these relationships have loosened, but they remain exceptions to the pluralist model of competitive policy-making.

Iron triangle: A policy-influencing relationship involving (in the United States) interest groups, the bureaucracy, and legislative committees, and a three-way trading of information, favours, and support.

• Pluralist conflict diverts attention away from the interests shared by leaders of mainstream groups, such as their common membership of the same class and ethnic group. There is still some truth, it is argued, in the conclusion drawn in 1956 by C. Wright Mills, who famously argued in his book The Power Elite that American leaders of industry, the military, and government formed an interlocking power elite, rather than separate power centres.

One famous analysis with critical implications for pluralist theory was offered in 1965 by the political scientist Mancur Olson in his book The Logic of Collective Action. Until then, it had often been assumed that all interests could achieve an approximately equal place at the bargaining table. But, Olson argued, it is difficult for people with diffuse interests to find each other, to come together, to organize themselves, and to compete against narrower and better organized interests. Each individual consumer, patient or student had less incentive to organize than is the case for the much smaller number of corporations, hos-pital and universities. This helped explain why it was so hard, for example, for ordinary citizens to compete against large corporations, which had funds, resources, contacts, and much else that could be used to influence policy-makers. Olson’s analysis overlapped with rational choice arguments that citizens did not have sufficient incentives to become informed about politics and to engage with other citizens. Certainly, the assumption of a balanced market for influence began to look unrealistic.

FIGURE 18.2: Iron triangles: the case of the United States

Not everyone agrees with this analysis, however. Since Olson’s day, organizations representing consumers and many other dispersed groups have emerged, grown and acquired a sometimes significant voice, not least in Washington DC. Trumbull (2012) argues that it is a misreading of history to believe that diffuse interests are impossible to organize or too weak to influence policy. Indeed, he suggests that weak interests often do prevail. His proposition is that organization is less important than legitimation: in other words, alliances forged among activists and regulators can form ‘legitimacy coalitions’ linking their agendas to the broader public interest. Hence, for example, such coalitions have limited the influence not only of the agricultural and pharmaceutical sectors in Europe, but also of some multinational companies in some developing countries.

If iron triangles are an American exception to pluralism, corporatism is the equivalent in continental Europe. (On iron triangles, see Focus 18.1 and 18.2.) Where classic iron triangles operated within particular sectors, corporatism engages the peak associations representing business and labour in wider social and economic planning. The groups become ‘social partners’ with government, engaging in tripartite discussions to settle important political questions such as wage increases, tax rates and social security benefits. Once a ‘social pact’ or ‘social contract’ is agreed for the year, the peak associations are expected to ensure the compliance of their members, thus avoiding labour unrest.

Corporatism: The theory and practice by which peak associations representing capital and labour negotiate with the government to achieve wide-ranging economic and social planning.

‘Social corporatism’, as this formula is called, worked best in smaller, highly organized countries where central agreements could be delivered by powerful peak associations with extensive membership. In the post-war decades, Austria was the clearest example but elements of the corporate model could also be found in Scandinavia and the Netherlands. Like iron triangles, corporatism has decayed. Peak associations have weakened, union membership has collapsed, smaller service companies have replaced large manufacturing industries and the ideological climate has shifted in favour of the market.Yet even today, corporatist thinking and practice provides a further challenge to the pluralist model.

Just as social corporatism has declined, so too have iron triangles. Factors involved include closer media scrutiny, new public interest groups that protest loudly when they spot the public being taken for a ride, and legislators who are more willing to speak out against closed and even corrupt policy-making. As policy issues has become more complex, so more groups have been drawn into the policy process, making it harder to stitch together insider deals. Reflecting more open government, the talk now is of issue networks. These refer to relationships between the familiar set of organizations involved in policy-making: government departments, interest groups, and legislative committees, with the addition of expert outsiders. However, issue networks are more open than iron triangles or corporate structures. A wider range of interests take part in decisions, the bias towards protective groups is reduced, new groups can enter the debate, and a sound argument carries greater weight.

Issue network: A loose and flexible set of interest groups, government departments, legislative committees, and experts that work on policy proposals of mutual interest.

As we saw in earlier chapters, the internet promises to shake things up in ways that are not yet fully understood. Where Olson argued that interests were handicapped by the difficulties that people had in finding each other and organizing, the rise of social media largely removed this problem from the equation. Anyone with access to the internet can now create advocacy sites dealing with everything from local to international interests, and invite users to Like them, post information, debate the issues, and network with like-minded users and engage the opposition. Online communities are both significant and challenging for interest groups. Opening a site by clicking a button takes little effort, and engagement may not go much beyond posting a comment or a link, but these online conversations can create small informal communities that add up to larger movements influencing public opinion.

Interest groups have a nose for where policy is made, and are adept at following the debate to the arenas where it is resolved. Generally, there are three key channels through which groups do most of their work: the direct channel that takes them to policy-makers, and the indirect channels through which they seek to influence political parties and public opinion.

Direct influence with policy-makers

Those who shape and apply policy are the ultimate target of most groups. Direct conversations with government ministers are the ideal, and talking with ministers before specific policies have crystallized is particularly valuable because it enables a group to enter the policy process at a formative stage. But such privileges are usually confined to a few well-connected individuals, and most interest group activity focuses in practice on the bureaucracy, the legislature and the courts. Of these, the bureaucracy is the main pressure point: interest groups follow power and it is in the offices of bureaucrats that detailed decisions are often formed.

For instance, ministers may decree a policy of sub-sidizing consumers who use renewable energy, a strategy that most groups must accept as given. However, the precise details of these incentives, as worked out in consultation with officials, will impinge directly on the profitability of energy suppliers. Even if access to top ministers is difficult, most democracies follow a convention of discussion over detail with organized opinion through consultative councils and committees. Often, the law requires such deliberation. In any case, the real expertise frequently lies in the interest group rather than the bureaucracy, giving the government an incentive to seek out this knowledge. Besides, from the government’s viewpoint, a policy which can be shown to be acceptable to all organized interests is politically safe.

While the bureaucracy is invariably a crucial arena for groups, the significance of the legislature depends on its political weight. Comparing the United States and Canada illustrates the differences:

• The US Congress (and, especially, its committees) forms a vital cog in the policy machinery. Members of Congress realize they are under constant public scrutiny, not least in the House of Representatives,where a two-year election cycle means that politicians must be constantly aware of their ratings by interest groups. The ability of groups to endorse particular candidates – and, indirectly, to support their re-election campaigns – keeps legislators sensitive to group demands (Cigler and Loomis, 2015), especially those which resonate in their home districts.

FIGURE 18.3: Channels of interest group influence

• In Canada, as in most democracies, Parliament is more reactive than proactive; as a result, interest groups treat its members as opinion-formers rather than policy-makers. Party voting is entrenched in the House of Commons, extending beyond floor votes to committees and, in any case, ‘committees seldom modify in more than marginal ways what is placed before them and virtually never derail any bill that the government has introduced’ (Brooks, 2012: 257). Such a disciplined environment offers few opportunities for influence.

Lobbying is a core activity of most interest groups and is usually conducted directly by group leaders. Increasingly, however, such efforts can take the form of hiring a specialist lobbying firm to represent the group to key decision-makers (see Focus 18.2). This development raises some troubling questions. Is it now possible for wealthy interest groups and corporations simply to pay a fee to a lobbying firm to ensure that a bill is defeated or a regulation deferred? Is lobbying just a fancy word for bribery? On the whole,the answer is ‘no’. Professional lobbyists are inclined to exaggerate their own impact for commercial reasons but, except in countries where there are particularly strong links between government and key interests (such as Japan), most can achieve little more than access to relevant politicians and, perhaps, bureaucrats. Often, the lobbying firm’s role is merely to hold the client’s hand, helping an inexperienced company find its way around the corridors of power when it comes to town.’

In the British Parliament, between the chambers of the House of Commons and the House of Lords, is an open lobby where citizens could once approach their Members of Parliament in order to plead their case or request help. From this habit derived the terms lobbying and lobbyist. The essential meaning of these terms remains the same but has evolved into the more specific idea of organized efforts by paid intermediaries to influence government. Lobbyists are professionals, often working for corporations or even for lobbying firms consisting of hired guns in the business of interest group communication. Such services are offered not only by specialist government relations companies, but also by divisions within law firms and management consultancies. These operations are growing in number in liberal democracies, with some companies even operating internationally.

Lobbying is growing for three main reasons:

• Government regulation continues to grow. A specialist lobbying firm working for a number of interest groups can often monitor proposed regulations more efficiently than would be the case if each interest group undertook the task separately.

• Public relations campaigns are becoming increasingly sophisticated, often seeking to influence interest group members, public opinion and the government in one integrated project. Professional agencies come into their own in planning and delivering multifaceted campaigns, which can be too complex for an interest group client to manage directly.

• Many firms now approach government directly, rather than working through their trade association. Companies, both large and small, find that using a lobbying company to help them contact a government agency or a sympathetic legislator can yield results more quickly than working through an industry body.

The central feature of the lobbying business is its intensely personal character. A legislator is most likely to return a call from a lobbyist if the caller is a former colleague. Lobbying is about who you know. For this reason, lobbying firms are always on the look-out for former legislators or bureaucrats with a warm contact book, although the rules on registration and financial disclosure have tightened recently in some democracies.

Lobbying: Efforts made on behalf of individuals, groups or organizations to influence the decisions made by elected officials or bureaucrats.

Rather than viewing professional lobbying in a negative light, we should recognize its contribution to effective political communication. It can focus the client’s message on relevant decision-makers, ensuring that the client’s voice is heard by those who need to hear it. Furthermore, lobbyists spend most time with sympathetic legislators, contributing to their promotion of a cause in which they already believe. Long-time Brussels-based commercial lobbyist Stanley Crossick (quoted in Thomas and Hrebenar, 2009: 138) said that ‘successful lobbying involves getting the right message over to the right people in the right form at the right time on the right issue’. In that respect, at least, it enhances the efficiency of governance.

Of course, not everything in the lobby is rosy. Even if a company achieves no more for its fee than access to a decision-maker (and even if that meeting would have been possible with a direct approach), perhaps such exchanges in themselves compromise the principle of equality which underpins democracy. Because buying access and buying influence are rarely distinguished in the public’s mind, meetings arranged through lobbyists damage the legitimacy of the political process and generate a need, only now being met, for effective regulation. But as long as petitioning the government is a right rather than a requirement, it is difficult to see how inequalities in interest representation can be avoided.

Indirect influence through political parties

In the past, many interest groups sought to use a favoured political party as a channel of influence, with group and party often bound together as members of the same family. For instance, socialist parties in Europe have long seen themselves engaged with trade unions in a single drive to promote broad working-class interests. In a similar way, the environmental movement spawned both promotional interest groups dealing with specific problems (such as pollution, waste, and threats to wild-life) and green political parties.

Such intimate relationships between interest groups and political parties have become exceptional. Roles have become more specialized as interest groups concentrate on the specific concerns of their members, while parties have broader agendas. For instance, the religious and class parties of Europe have broadened their appeal, seeking to be viewed as custodians of the country as a whole, while green parties have long since moved far beyond their environmental roots into a wide range of policy interests. The distinction between parties seeking power and interest groups seeking influence has sharpened as marriages of the heart have given way to alliances of convenience. As a result, most interest groups now seek to hedge their bets, rather than to develop close links with a specific political party. Loose, pragmatic links between interests and parties are the norm, and protective interests tend to follow power, not parties.

Indirect influence through public opinion

Public opinion is a critical target for promotional interest groups, the twin goals being to shape public perceptions and also to mobilize public concern so as to bring pressure on government for policy change. This wider audience can be addressed by focusing on paid advertising (advocacy advertising), by promoting favourable coverage in conventional media (public relations), and by using social media to promote ideas and bring together like-minded constituencies.

Since many promotional groups lack both substantial resources and access to decision-makers, public opinion becomes a venue of necessity. Traditionally, though, the media are less important to protective groups with their more specialized and secretive demands. What food manufacturer would go public with a campaign opposing nutritional labels on foods? The confidential-ity of a government office is a more appropriate arena for fighting rear-guard actions of this kind. Keen to protect their reputation in government, protective groups steer away from disruption; they want to be seen as reliable partners by the public servants on the other side of the table.

But even protective groups are now seeking to influence the climate of public opinion, especially in political systems where legislatures help to shape policy. Especially when groups sense that public opinion is already onside, they increasingly follow a dual strategy, appealing to the public and to the legislature. The risk lies in upsetting established relationships with bureau-crats; however, this danger has declined compared with the era of iron triangles. In Denmark, for instance,‘decision makers seem to accept that groups seek attention from the media and the general public without excluding them from access to making their standpoint heard in decision-making’ (Binderkrantz, 2005: 703). Slowly and cautiously, even protective groups are emerging from the bureaucratic undergrowth into the glare of media publicity.

Ingredients of influence

There is no doubt that some interest groups exert more influence over government than others. So, what is it that gives particular groups the ability to persuade? Much of the answer is to be found in four attributes ranging from the general to the specific: legitimacy, sanctions, membership, and resources.

First, the degree of legitimacy achieved by a particular group is clearly important. Interests enjoying high prestige are most likely to prevail on particular issues. Professional groups whose members stand for social respectability can be as militant on occasion, and as restrictive in their practices, as trade unions once were. But lawyers and doctors escape the public hostility that unions continue to attract. Similarly, the intrinsic importance of business to economic performance means that its representatives can usually obtain a hearing in government.

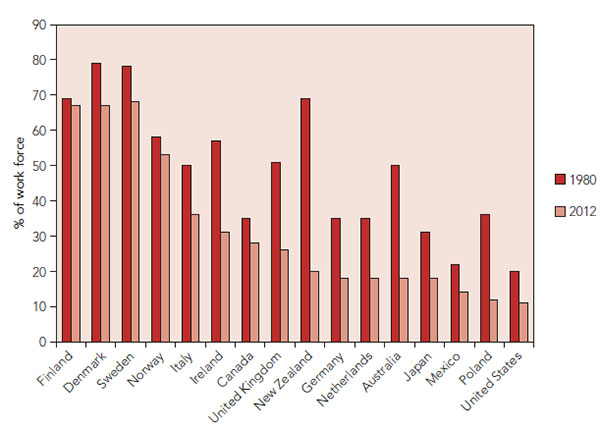

Second, a group’s influence depends on its membership. This is a matter of density and commitment, as well as sheer numbers. Labour unions have seen their influence decline as the proportion of workers belonging to unions fell in nearly all liberal democracies between 1980 and 2012, especially in the private sector (see Figure 18.4). Except for Scandinavia, union members are now a minority of the workforce.This has weakened labour’s bargaining power with government and employers alike. Influence is further reduced when membership is spread among several interest groups operating in the same sector.

Density: The proportion of all those eligible to join a group who actually do so. The higher the density, the stronger a group’s authority and bargaining position with government.

The commitment of the membership is also important. For instance, the several million members of the US National Rifle Association (NRA) – described by the New York Times as ‘the most fearsome lobbying organization in America’ (Draper, 2013) – include many who are prepared to contact their congressional representatives in pursuit of the group’s goal of ‘preserving the right of all law-abiding individuals to purchase, possess and use firearms for legitimate purposes’. Their well-schooled activism led George Stephanopoulos, spokesman for President Clinton, to this assessment: ‘let me make one small vote for the NRA. They’re good citizens.They call their Congressmen.They write.They vote. They contribute. And they get what they want over time’ (NRA, 2012).

Third, the financial resources available to an interest group affect influence. In the European Union, for example, as more decisions have been made at the EU level, so more interest groups have opened offices in Brussels, the seat of the major EU institutions. Prime among those groups have been business interests: individual corporations are represented either directly or through lobbying firms, and several cross-sectoral and multi-state federations have been created to represent wider economic interests. The latter include Business Europe (with national business federations as members), the European Consumers’ Organization, the European Trade Union Confederation, and the European Roundtable of Industrialists, an informal forum of chief executives from nearly 50 major European corporations.

FIGURE 18.4: Falling trade union membership

Note: Earlier figure for Poland is from 1990, and for Mexico from 1992.

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2015)

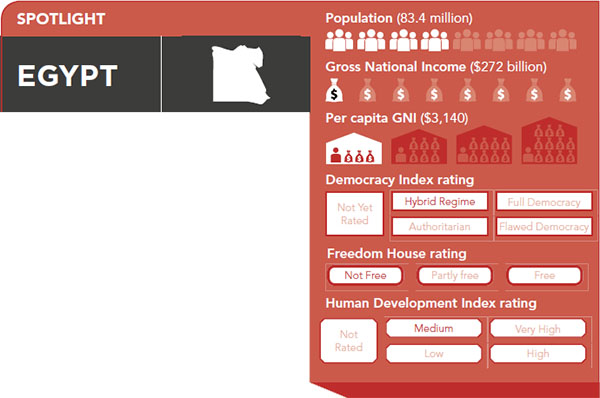

Brief Profile: Egypt has long been a major player in Middle East politics, thanks not only to its pioneering role in the promotion of Arab nationalism but also to its strategic significance in the Cold War and in the Arab–Israeli conflict. It was also at the heart of the Arab Spring, with pro-democracy demonstrations leading to the fall from power of Hosni Mubarak in 2011. Democratic elections brought Mohamed Morsi to power in 2012, but he was removed in a military coup the following year. Egyptians now face new uncertainties, led as they are by a military officer – Abdel Fattah el-Sisi – who has reinvented himself as a civilian leader. Egypt possesses the second biggest economy in the Arab world, after Saudi Arabia, but is resource-poor. It relies heavily on tourism, agriculture, and remittances from Egyptian workers abroad and struggles to meet the needs of its rapidly growing population.

Form of government  Unitary semi-presidential republic. Modern state formed 1952, and most recent constitution adopted 2014.

Unitary semi-presidential republic. Modern state formed 1952, and most recent constitution adopted 2014.

Legislature  Unicameral People’s Assembly (Majlis el-Shaab) with 567 members, of whom 540 are elected for renewable four-year terms and 27 can be appointed by the president.

Unicameral People’s Assembly (Majlis el-Shaab) with 567 members, of whom 540 are elected for renewable four-year terms and 27 can be appointed by the president.

Executive  Semi-presidential. A president directly elected for no more than two four-year terms, governing with a prime minister who leads a Cabinet accountable to the People’s Assembly. There is no vice president.

Semi-presidential. A president directly elected for no more than two four-year terms, governing with a prime minister who leads a Cabinet accountable to the People’s Assembly. There is no vice president.

Judiciary  Egyptian law is based on a combination of British, Italian and Napoleonic codes. The Supreme Constitutional Court has been close to recent political changes in Egypt; it has 21 members appointed for life by the president, with mandatory retirement at age 70.

Egyptian law is based on a combination of British, Italian and Napoleonic codes. The Supreme Constitutional Court has been close to recent political changes in Egypt; it has 21 members appointed for life by the president, with mandatory retirement at age 70.

Electoral system  A two-round system is used for presidential elections, with a majority vote needed for victory in the first round, while a mixed member majoritarian system is used for People’s Assembly elections; two-thirds of members are elected using party list proportional representation, and one-third in an unusual multi-member plurality system in two large districts.

A two-round system is used for presidential elections, with a majority vote needed for victory in the first round, while a mixed member majoritarian system is used for People’s Assembly elections; two-thirds of members are elected using party list proportional representation, and one-third in an unusual multi-member plurality system in two large districts.

Parties  Multi-party, but unsettled because of recent instability. Parties represent a wide range of positions and ideologies.

Multi-party, but unsettled because of recent instability. Parties represent a wide range of positions and ideologies.

Interest groups in Egypt

We saw in Chapter 4 how, in authoritarian political systems based on personal rule, access to policy-makers depends on patronage, clients, and contacts – proof of the adage that who you know is more important than what you know. Egypt is a case in point. It would seem to have a healthy and varied interest group community, representing business, agriculture, the professions, and religious groups, but government has long controlled access through the kind of corporatism discussed later in this chapter. At the same time, though, some interest groups have developed sufficient power and authority as to exert the influence usually associated with interest groups in liberal democracies.

The number and reach of groups in Egypt grew sharply during the administration of Hosni Mubarak (1981–2011). Groups such as the Chamber of Commerce and the Federation of Industries lobbied for economic liberalization, including the abolition of fixed prices. The leaders of professional groups such as the Journalists Syndicate, the Lawyers Syndicate, and the Engineers Syndicate used their personal contacts in government to win concessions for their members. Interest groups became so numerous that the Mubarak government felt the need to monitor them more closely, requiring that they be officially registered, and taking the controversial step in 1999 of passing a law that gave the government considerable powers to interfere in the work of groups. It could hire and fire board members, cancel board decisions, and even dissolve a group by court order. Groups were also barred from taking part in political activity, and their members were subject to imprisonment for a variety of vague and general crimes, including ‘undermining national unity’. Groups affiliated with religious organizations and those working on human rights issues were particularly affected by this reassertion of traditional state authority.

The administration of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi that came to power in a military coup in 2013 remains influenced by the military, and concerned about promoting economic development and controlling Islamic militancy. For the foreseeable future, the value of interest groups is likely to be defined in Egypt by the extent to which they are consistent with these goals.

Fourth, the ability of a group to invoke sanctions is clearly important. A labour union can go on strike, a multinational corporation can take its investments elsewhere, a peak association can withdraw its cooperation in forming policy. As a rule, promotional groups (such as those with environmental interests) have fewer sanctions available to use as a bargaining chip; their influence suffers accordingly.

Social movements

Interest groups are part of conventional politics, operating through orthodox channels such as the bureaucracy. Like the political systems of which they form part, they are increasingly treated with distrust by the wider public. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that traditional interest groups have been supplemented by social movements – a less conventional form of participation through which people come together to seek a common objective by means of an unorthodox challenge to the existing political order. These movements do not necessarily consist of pre-existing interest groups, but groups are often at their heart; thus the environmental movement that emerged in most industrialized countries in the 1960s was driven by interest groups, which continue to carry the banner of the environmental movement today. Social movements espouse a political style which distances them from established channels, thereby questioning the legitimacy, as well as the decisions, of the government.Their members adopt a wide range of protest acts, including demonstrations, sit-ins, boycotts, and political strikes. Some such acts may cross the border into illegality but the motives of the actors are political, rather than criminal.

Social movement: A movement emerging from society to pursue non-establishment goals through unorthodox means. Its objectives are broad rather than sectional and its style involves a challenge by traditional outsiders to existing elites.

Consider the example of the protestors who occupied Zuccotti Park in New York City’s financial district in 2011 to express their disapproval of growing income inequality, especially in the financial sector. Using the slogan ‘We are the 99 per cent’, Occupy Wall Street rapidly became not only a national, but also an international phenomenon, with tented encampments emerging in many countries, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, South Africa, and Turkey. Without putting up candidates for election or engaging in conventional lobbying, the Occupy protests succeeded in focusing public attention on income disparities and unchecked corporate power.

TABLE 18.2: Comparing social movements, parties, and interest groups

To appreciate the character of social movements, we can usefully compare them with parties and interest groups (see Table 18.2). Movements are more loosely organized, typically lacking the precise membership, subscriptions, and leadership of parties. As with those parties whose origins lie outside the legislature, movements emerge from society to challenge the political establishment. However, movements do not seek to craft distinct interests into an overall package; rather, they claim the moral high ground in one specific area.

Like interest groups, social movements can sometimes have focused concerns, such as protests against a war or in support of nuclear disarmament, but their concerns are usually broader, as with the cases of the feminist, environmental, and civil rights movements. As with interest groups, social movements do not seek state power, aiming rather to influence the political agenda, usually by claiming that their voice has previously gone unheard. Whereas interest groups have targeted goals, social movements are more diffuse, seeking cultural as much as legislative change. For example, the gay movement might measure its success by how many gay people come out, not just by the passage of anti-discrimination legislation. Similarly, women’s movements may emphasize consciousness-raising among women.

Tilly (2004: 33) regards the British anti-slavery movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as the earliest example of a social movement as now understood. The techniques adopted in this campaign, including petitions and boycotts, established a palette of protest activities soon emulated by other reforming groups. Then came the suffragette movements of the early nineteenth and early twentieth centuries on both sides of the Atlantic, which were instrumental in winning the right to vote for women. Since then, the number, concerns, and significance of social movements have all expanded (see Table 18.3).

TABLE 18.3: Examples of social movements

| Time and place | Focus | |

| Gay rights | Most active 1960s–present, in developed non-Islamic countries | Equal rights for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people |

| Chipko movement | 1960s–1980s, India | Village- and rural-based protests against deforestation |

| Anti-apartheid movement | Mid-1960s–1994, mainly Britain | To end apartheid in South Africa through sporting, political, and academic boycotts |

| Landless workers | Mid-1980s–present, Brazil | Land reform and access to land for the poor |

| Anti-globalization | Late 1980s–present, many countries | Critical of the power of global corporate capitalism |

| Fair trade | 1960s–present, originally in Europe | Higher prices and sustainable techniques for producers of commodities exporting from the developing to the developed world |

In the 1950s, ‘mass movements’, as they were then called, were perceived as a threat to the stability of liberal democracy. They were taken as a sign of a poorly functioning mass society ‘containing large numbers of people who are not integrated into any broad social groupings, including classes’ (Kornhauser, 1959: 14). Movements were judged to be supported by marginal, disconnected groups, such as unemployed intellectuals, isolated workers, and the peripheral middle class. Goodwin and Jasper (2003a: 5) claim that until the 1960s, ‘most scholars who studied social movements were frightened of them’.

The 1960s and 1970s saw a radical rethink. The civil rights movement in the United States mobilized blacks from multiple economic and social backgrounds, while Vietnam and the draft propelled parts of the educated American middle class into anti-war movements. As intellectuals became more critical of government, so their treatment of social movements became more positive. By the end of the twentieth century, della Porta and Diani (2006: 10) were able to conclude that it was ‘no longer possible to define movements in a prejudi-cial sense as phenomena which are marginal and anti-institutional. A more fruitful interpretation towards the political interpretation of contemporary movements has been established.’

The supporters of social movements do not always need much in the way of resources to make an impres-sion; sheer numbers may be enough, provided that the goals are clear. This means that social movements lend themselves well to political participation in poorer societies, where movements also benefit from the direct and immediate interest of many participants in encouraging policy change. A good example is the Green Belt Movement that has been active since 1977 in Kenya. It mobilizes rural women to plant trees in an effort to stop deforestation and soil erosion, and to provide wood fuel and income. In 2004, its founder – Wangari Maathai – became the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Developments in communications have lowered the barriers to entry for new movements, facilitating their rapid emergence when ordinary politics has been deemed to fail. For example, farmers in France have long been renowned for taking their protests against agricultural policy (including falling prices, cheaper imports, and environmental regulation) onto the streets. They block traffic by driving their trac-tors slowly along highways, dump tons of vegetables or manure onto city squares, and set fire to hay outside public buildings. In a digital age, such protests are easier than ever to co-ordinate, even in the absence of formal organization.

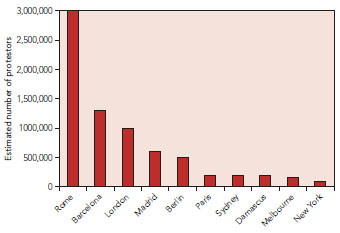

Mass communication also facilitates simultaneous global protest with virtually no central leadership at all; people in one country simply hear what is planned elsewhere and decide to join in. A remarkable example is provided by the international protests on the weekend of 15–16 February 2003 against the invasion of Iraq, which attracted an estimated six million people in about 600 cities (Figure 18.5). Bennett (2005: 207) reckons this protest, which provided a shared label for people from different backgrounds as well as countries, was ‘the largest simultaneous multinational demonstration in recorded history’. He concludes (p. 205) that ‘such applications of communication technology favour loosely linked distributed networks that are minimally dependent on central coordination, leaders or ideological commitment’.

FIGURE 18.5: Demonstrations against the Iraq War, 2003

Source: Estimates reported in the Financial Times, 17 February 2003

Interest groups in authoritarian states

In authoritarian states, the relationship between government and interest groups is very different from the democratic model. In liberal democracies, as we have seen, powerful groups can capture elements of the government but in authoritarian states those groups that do exist are generally subordinate to the regime. Authoritarian rulers see freely organized groups as a potential threat to their own power; hence, they seek either to repress such groups, or to incorporate them within their power structure. The groups are prisoner rather than master.

In the second half of the twentieth century, many authoritarian rulers had to confront the challenge posed by new groups unleashed by economic development, including labour unions, peasant leagues, and educated radicals. One of their responses was to suppress such groups completely. Where civil liberties were weak and groups were new, this approach was feasible. In military regimes, leaders often had their own fingers in the economic pie, sometimes in collaboration with overseas corporations; the goal of rulers was to maintain a workforce that was both compliant and poorly paid.Trouble-makers seeking to establish labour unions were quickly removed.

Long-term military rule in Burma offered an example of this forced exploitation. The military rulers that governed the country from 1962 to 2011 outlawed independent trade unions, collective bargaining, and strikes; imprisoned labour activists; and maintained strict control of the media. This repressive environment enabled the regime to use forced labour, particularly from ethnic minorities, to extract goods such as timber, which were exported through the black market for the financial benefit of army officers. Fortunately, governance in Burma softened considerably as political reforms strengthened from 2011.

Alternatively, authoritarian rulers could work to manage the expression of new interests created by development. In other words, they could allow interests to organize, but seek to control them: a policy of incor-poration rather than exclusion. By enlisting part of the population, particularly its more modern sectors, into officially sponsored associations, rulers hoped to accelerate the push towards modernization.This is a conceptual cousin of the social corporatism discussed earlier in the chapter, the difference being that it is a form of top-down political manipulation. It was common in Latin America, where the state licensed, funded, and granted a monopoly of representation to favoured groups, reflecting a Catholic tradition inherited from colonial times (Wiarda, 2004).

Before the democratic and economic reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, Mexico offered an example of this format. Its governing system was founded on a strong ruling organization: the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). This party was itself a coalition of labour, agrarian, and ‘popular’ sectors (the latter consisting mainly of public employees). Favoured unions and peasant associations within these sectors gained access to the PRI. Party leaders provided state resources, such as subsidies and control over jobs, in exchange for the political support (not least in ensuring PRI’s re-election) of incorporated groups.The system was a giant patron–client network. For the many people left out of the organized structure, however, life was extremely hard.

But Mexican corporatism declined. The state was overregulated, giving so much power to government and PRI-affiliated sectors as to deter business investment, especially from overseas. As the market sector expanded, so the patronage available to PRI diminished. In 1997, an independent National Workers Union emerged to claim that the old mechanisms of state control were exhausted, a point which was confirmed by PRI’s defeat in a presidential election three years later. (PRI regained the presidency in 2012, but its victorious candidate claimed there would be no return to the past.)

The position of interest groups in communist states was even more marginal than in other non-democratic regimes, providing a stark contrast to pluralism. For most of the communist era, there were no independent interest groups. Interest articulation by freely organized groups was inconceivable. Communist rulers sought to harness all organizations into so-called ‘transmission belts’ for party policy. Trade unions, the media, youth groups, and professional associations were little more than branches of the party, serving the cause of communist construction.

Elements of this tradition can still be found in contemporary China (see Table 18.4). The ruling Communist Party continues to provide the framework for most formal political activity, with a cluster of ‘mass organizations’ that are led by party officials and continue to transmit policy downwards, rather than popular concerns upwards. However, a new breed of non-governmental organization emerged in China in the 1980s, strengthening the link between state and society. Examples include the China Family Planning Association, Friends of Nature, the Private Enterprises Association, and the Federation of Industry and Commerce. Typically, only one body is officially recognized in each sector, confirming the state’s continuing control. The limited status of these new entities is reflected in their title: government-organized non-governmental organizations (GONGOs). What we are seeing in China, then, is what Frolic (1997) calls a ‘state-led civil society’, with civil society serving as an adjunct, rather than an alternative, to state power.

In hybrid regimes, the position of interest groups lies somewhere between their comparative autonomy in liberal democracies and their marginal status in authoritarian states. The borders between the public and private sectors are poorly policed, allowing presidents and their allies to intervene in the economy so as to reward friends and punish enemies. But this involvement is selective, rather than comprehensive, occasionally overriding normal business practices but not seeking to replace them.

At least in the more developed hybrid regimes, the result can be a dual system of representation, combining a role for interest groups on routine matters, with more personal relationships (nurtured by patronage) on matters that are of key importance to the president and the ruling elite. In the most sensitive economic areas (control over energy resources, for example), employer is set against employer in a competition for political influence, leaving little room for the development of influential business associations. The general point is that, even though hybrid regimes allow some interests to be expressed, interest groups are far less significant than in a liberal democracy.

Russia is an interesting case. The separation between public and private sectors, so central to the organization of interests in the West, has not fully emerged. Particularly in the early post-communist years, ruthless business executives, corrupt public officials, and jumped-up gangsters made deals in a virtually unregulated free-for-all. Individual financiers pulled the strings of their puppets in government but the politics was personal, rather than institutional. In such an environment, interests were everywhere but interest groups were nowhere.

As Russian politics stabilized and its economy recovered, so some business associations of a Western persuasion emerged, even if they have not yet won extensive political influence. As early as 2001, Peregudov (2001: 268) claimed that ‘in Russia a network of business organizations has been created and is up and running’. He suggested that this network was capable of adequately representing business interests to the state. However, this network has received limited attention from Vladimir Putin during his tenure as president. At a strategic level, he continues to reward his business friends and, on occasion, to imprison his enemies. Top-level relationships are still between groups of powerful individuals, not institutions.

TABLE 18.4: Social organizations in China

| Type | Features | |

| All-China Federation of Trade Unions | Mass organization | Traditional transmission belt for the Communist Party. |

| All-China Women’s Federation | Mass organization | Traditionally a party-led body, this federation has created some space for autonomous action. |

| China Family Planning Association | Non-governmental organization | Sponsored by the State Family Planning Commission, this association operates at international and local level. |

| Friends of Nature | Non-governmental organization | Operates with some autonomy in the field of environmental education. |

Source: Adapted from Saich (2015: Chapter 7)

We must be wary of assuming that Russia will eventually develop a liberal democratic system of interest representation. Certainly, pluralism is not currently on the agenda. Evans (2005: 112) even suggests that Putin has ‘sought to decrease the degree of pluralism in the Russian political system; it has become increasingly apparent that he wants civil society to be an adjunct to a strong state that will be dedicated to his version of the Russian national ideal’. In a manner resembling China’s GONGOs, the state works to collaborate with favoured groups, while condemning others to irrelevance.

The Russian government’s strong nationalist tone has led to particular criticism of those groups (such as women’s associations) which have depended on overseas support to survive in an unsympathetic domestic environment. Few promotional groups in Russia possess a significant mass membership; most groups operate solely at grassroots level, working on local projects such as education or the environment. As in China, these groups operate under state supervision. So Russia’s combination of an assertive state and a weak civil society continues to inhibit interest group development.

• Are interest groups a part of, or a threat to, democracy?

• To what extent do special interests limit the functioning of the market of political ideas?

• True or false: rather than viewing professional lobbying in a negative light, we should recognize its contribution to eêctive political communication.

• How is the rise of social media likely to impact the organization and political role of interest groups?

• Identify any signi˚cant social movements, past or present, in your country. Do they pose a challenge to establishment politics?

• How does corporatism diêr in democratic and authoritarian settings?

KEY CONCEPTS

Civil society

Corporatism

Density

Interest group

Iron triangle

Issue network

Lobbying

Peak association

Pluralism

Promotional group

Protective group

Social movement

Think-tank

FURTHER READING

Beyers, Jan, Rainer Eising, and William A. Maloney (eds) (2012) Interest Group Politics in Europe: Lessons from EU Studies and Comparative Politics. A collection analysing interest group politics in the European Union.

Olson, Mancur (1965) The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. A clas-

sic study of interest group formation, and still interesting for what it says about pluralism, even if some of the core arguments have been challenged.

Tarrow, Sidney G. (2011) Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics, 3rd edn. Focuses on the rise and fall of social movements as the outcome of political opportuni-

ties, state strategy, the mass media, and international diffusion.

Wilson, Graham K. (2003) Business and Politics: A Comparative Introduction, 3rd edn. Offers a clear comparative assessment of an important, but still understudied, topic.

Yadav,Vineeta (2011) Political Parties, Business Groups, and Corruption in Developing Countries. A study of the relationship between business lobbying and corruption in developing countries.

Zetter, Lionel (2014) Lobbying:The Art of Political Persuasion, 3rd edn. A global view of the dynamics of lobbying, including chapters on Europe, the United States, Asia and the Middle East.