PREVIEW

Public policy is an appropriate topic with which to close this book, since it concerns the outcomes of the political process. The core purpose of government is to manage and address the needs of society. The approaches that governments adopt and the actions they take (or avoid) to address those needs collectively constitute their policies, and are the product of the political processes examined throughout the preceding chapters. Where political science examines the organization and structure of the political factory, policy analysis looks at how policy is formed, at the influences on policy, and at the results of different policy options.

This chapter begins with a review of three models of the policy process: the rational, the incremental, and the garbage-can model. The first provides an idealistic baseline, while the second and third are more reflective of reality, but it is debatable in which proportions. The chapter then goes on to look at the policy cycle, an artificial means for imposing some order on what is, in reality, a complex and often confusing process.The problems experienced at each step in the process – initiation, formulation, implementation, evaluation, and review – give us insight into why so many public policies fall short of their goals. The chapter then looks at the related phenomena of policy diffusion and policy convergence, before ending with a review of the dynamics of policy making in authoritarian systems, where – with greater focus on power politics – the policy process has its own distinctive dynamic.

CONTENTS

• Public policy: an overview

• Models of the policy process

• The policy cycle

• Policy diffusion and convergence

• Public policy in authoritarian states

KEY ARGUMENTS

| • Studying public policy offers a distinctive perspective within the study of politics. It involves looking at what governments do, rather than the institutional framework within which they do it. |

| • Underlying much policy analysis is a concern with the quality and effectiveness of what government does. Policy analysis asks ‘How well?’, rather than just ‘How?’ or ‘Why?’ |

| • There is always a danger of imagining policy-making as a rational process with precise goals. The incremental and garbage-can models offer a hearty dose of realism. Policy, it is always worth remembering, is embedded in politics; a statement of policy can be a cover for inaction. |

| • Breaking the policy process into its component stages, from initiation to evaluation, helps in analysing and comparing policies. The later stages, implementation and evaluation, provide a different focus which is integral to policy analysis. |

| • Policy diffusion and convergence studies help explain how policies evolve in similar directions in multiple countries. |

| • Policy in authoritarian regimes plays a secondary role to politics, where the overriding requirement for survival in offi ce often leads to corruption, uncertainty, and stagnation. |

Public policy is a collective term for the objectives and actions of government. It is more than a decision or even a set of decisions, but instead describes the approaches that elected officials adopt in dealing with the demands of their office, and the actions they take (or avoid taking) to address public problems and needs. The choices they make are driven by a variety of influences, including the priorities they face, their political ideology, the economic and political climate, and the budgets they have available. Policies consist both of aims (say, to reverse climate change) and of means (switching to renewable sources of energy in order to cut carbon dioxide emissions).

Public policy: The positions adopted and the actions taken (or avoided) by governments as they address the needs of society.

When parties or candidates run for office, they will have a shopping list of issues they wish to address, and the positions they take will be their policies. When they are elected or appointed to office, they will usually continue to pursue these policies, which will be expressed in the form of public statements, government programmes, laws, and actions. If policy was limited to these published objectives, then it might be relatively easy to understand and measure. However, government and governance are also influenced by informal activities, opportunism, the ebb and flow of political and public interest, and simply responding to needs and problems as they present themselves.

Once elected to office, political leaders will often find that their priorities and preferred responses will change because of circumstances. They may be diverted by other more urgent problems, or find that their proposals lack adequate political support or funding, or discover that implementation is more difficult then they anticipated. In understanding the policy process, it is important to avoid imposing rationality on a process that is often driven by political considerations: policies can be contradictory, they can be nothing more than window-dressing (an attempt to be seen to be doing something, but without any realistic expectation that the objective will be achieved), and policy statements may be a cover for acting in the opposite way to the one stated.

But whatever the course taken and the eventual outcome, the actions of government (combined with their inaction) are understood as their policies. These policies become the defining qualities of governments and their leaders, and the records of these policies in addressing and alleviating problems will become the reference points by which governments and leaders are assessed, and a key factor in determining whether or not they will be returned to another term in office.

The particular task of policy analysis is to understand what governments do, how they do it, and what difference it makes (Dye, 2012). So, the focus is on the content, instruments, impact, and evaluation of public policy, more than on the influences that come to bear on the policy process. The emphasis is downstream (on implementation and results) as much as upstream (on the institutional sources of policy). Because analysts are concerned with improving the quality and efficacy of public policy, the subject exudes a practical air. Policy analysts want to know whether and why a policy is working, and how else its objectives might be pursued.

Policy analysis: The systematic study of the content and impact of public policy.

Models of the policy process

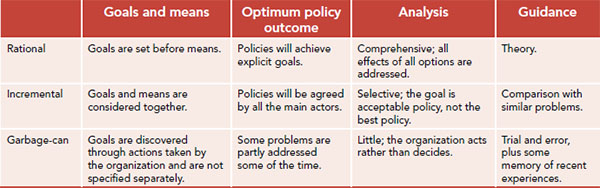

In analysing the manner in which policy is made, scholars have developed three distinct models: the rational model associated with Herbert Simon (1983), the incremental model developed by Charles Lindblom (1959, 1979), and the garbage-can model, so named by Michael Cohen et al. (1972). In evaluating these different perspectives, and in looking at policy analysis generally, we must distinguish between accounts of how policy should be made and descriptions of how it actually is made. Moving through each of these models in order (Table 19.1) is, in part, a transition from the former to the latter:

• The rational model seeks to elaborate what would be involved in rational policy-making without assuming that its conclusions are reflected in what actually happens.

• The incremental model views policy as a compromise between actors with ill-defined or even contradictory goals, and can be seen either as an account of how politics ought to proceed (namely, peacefully reconciling different interests), or as a description of how policy is made.

• The garbage-can model is concerned with highlighting the many limitations of the policy-making process within many organizations, looking only at what is, not what ought to be.

TABLE 19.1: Three models of policy-making

The lesson is that we should recognize the different functions these models perform, rather than presenting them as wholly competitive.

The rational model

Suppose you are the secretary of education and your key policy goal is an improvement in student performance. If you opt for the rational model, then you would first ensure that you had a complete and accurate set of data on performance levels, then set your goals (for example, a 10 per cent increase in the number of students going to university within five years), and then you would list and consider the most efficient means of achieving those goals.You might choose to improve secondary teaching, expand the size or the number of universities, deepen support for students from disadvantaged backgrounds, increase the number of university staff, improve facilities, or some combination of these approaches. Your approach focuses on efficiency, and demands that policy-makers rank all their values, develop specific options, check all the results of choosing each option against each value, and select the option that achieves the most values.

Rational model: An approach to understanding policy that assumes the methodical identification of the most efficient means of achieving specific goals.

Cost–benefit analysis: An effort to make decisions on the basis of a systematic review of the relative costs and benefits of available options.

This is, of course, an unrealistic counsel of perfec-tion, because it requires policy-makers to foresee the unforeseeable and measure the unmeasurable. So, the rational model offers a theoretical yardstick, rather than a practical guide. Even so, techniques such as cost– benefit analysis (CBA) have been developed in an attempt to implement aspects of the rational model, and the results of such analyses can at least discourage policy-making driven solely by political appeal (Boardman et al., 2010).

Seeking to analyse the costs and benefits associated with each possible decision does have strengths, particularly when a choice must be made from a small set of options. Specifically, CBA brings submerged assumptions to the surface, benefiting those interests that would otherwise lack political clout; for example, the benefit to the national economy from a new airport runway is factored in, not ignored by politicians overreacting to vociferous local opposition. In addition, CBA discourages symbolic policy-making which addresses a concern without attempting anything more specific; it also contributes to transparent policy-making by forcing decision-makers to account for policies whose costs exceed benefits.

For such reasons, CBA has been formally applied to every regulatory proposal in the United States expected to have a substantial impact on the economy. It has also played its part in the development of risk-based regulation in the United Kingdom, under which many regulators seek to focus their efforts on the main dangers, rather than mechanically applying the same rules to all. The cost–benefit principle here is to incur expenditure where it can deliver the greatest reduction in risk (Hutter, 2005).

However, CBA, and with it the rational model of policy formulation, also has weaknesses. It underplays soft factors such as fairness and the quality of life. It calculates the net distribution of costs and benefits but ignores their distribution across social groups. It is cumbersome, expensive, and time-consuming. It does not automatically incorporate estimates of the likelihood that claimed benefits will be achieved.There is often no agreement on what constitutes a cost and what constitutes a benefit.

Take, for example, the problem of air pollution. We know it exists (particularly in and around large urban areas), we know its sources, we have a good idea of how to control and prevent it, and we have a good idea of its potential impact on human life. There is little question that it causes health problems, and can reduce overall life expectancy. However, it affects people differently, because some have a greater capacity than others to live and function in a polluted environment. The precise links between pollution and illness or death are often unclear, we cannot be sure how much health care costs are impacted by higher levels of pollution, and it is hard to place a value on a human life, or – more specifically – on extending life expectancy (Guess and Farnham, 2011: ch. 7). It is also hard to calculate the relative costs and benefits of economic development that takes pollution control into account versus such development that does not. The result of difficulties is that, in the real political world, any conclusions from CBA may be over-ridden by broader, less clear-cut but more important considerations.

The incremental model

Where the rational model starts with goals, the incremental model starts with interests. Taking again the example of improved educational performance, an education secretary proceeding incrementally would consult with the various stakeholders, including teachers’ unions, university administrations, and educational researchers. A consensus acceptable to all interests might emerge on how extra resources should be allocated. The long-term goals might not be measured or even specified, but we would assume that a policy acceptable to all is unlikely to be disastrous. Such an approach is policy-making by evolution, not revolu-tion; an increment is literally a small increase in an existing sequence. It ties in to the idea of path dependence discussed in Chapter 6 (the outcome of a process depends on earlier decisions that lead policy down a particular path).

Incremental model: An approach to policy-making that sees policy evolution as taking the form of small changes following negotiation with affected interests.

The incremental model was developed by Lindblom (1979) as part of a reaction against the rational model. Rather than viewing policy-making as a systematic trawl through all the options, and a focus on a single comprehensive plan, Lindblom argued that policy is continually remade in a series of minor adjustments to the existing direction, in a process that he described as ‘the science of muddling through’.What matters here is that those involved should agree on policies, not objectives. Agreement can be reached on the desirability of following a particular course, even when objectives differ. Hence, policy emerges from, rather than precedes, negotiation with interested groups.

This approach may not lead to achieving grand objectives but, by taking one step at a time, it at least avoids making huge mistakes.Yet, the model also reveals its limits in situations that can only be remedied by strategic action. As Lindblom (1979, 1990) himself came to recognize, incremental policy-making deals with existing problems, rather than with avoiding future difficulties. It is politically safe, but unadventurous; remedial, rather than innovative. But the threat of ecological disaster, for instance, has arisen precisely from our failure to consider our long-term, cumulative impact on the environment. For the same reasons, incrementalism is better suited to stable high-income liberal democracies than to low-income countries seeking to transform themselves through development. It is pluralistic policy-making for normal times.

The garbage-can model

To understand the title of this model, we return to our example. How would the garbage-can model interpret policy-making to improve educational performance? The answer is that it would doubt the significance of such clear objectives. It would suggest that, within the government’s education department, separate divisions and individuals engage in their own routine work, interacting through assorted committees whose composition varies over time. Static enrolments may be a concern of university administrators and solutions may be available elsewhere in the organization, perhaps in the form of people committed to online learning, or an expansion of financial aid. But whether participants with a solution encounter those with a problem, and in a way that generates a successful resolution, is hit and miss – as unpredictable and fluctuating as the arrangement of different types of garbage in a rubbish bin (Cohen et al., 1972).

Garbage-can model: An approach to understanding policy-making that emphasizes its partial, fluid, and disorganized qualities.

So, the garbage-can model presents an unset-tling image of decision-making. Where both the rational and incremental models offer some prescription, the garbage-can expresses the perspective of a jaundiced realist. As described by Cohen et al., it is ‘a collection of choices looking for problems, issues and feelings looking for decision situations in which they might be aired, solutions looking for issues to which they might be the answer, and decision makers looking for work’. Policy-making is seen as partial, fluid, chaotic, anarchic, and incomplete. Organizations are conceived as loose collections of ideas, rather than as holders of clear preferences; they take actions which reveal rather than reflect their preferences. To the extent that problems are addressed at all, they have to wait their turn and join the queue. Actions, when taken, typically reflect the requirement for an immediate response in a specific area, rather than the pursuit of a definite policy goal. At best, some problems are partly addressed some of the time. The organization as a whole displays limited overall rationality – and little good will come until we recognize this fact (Bendor et al., 2001).

This model can be difficult to grasp, a fact that shows how deeply our minds try to impose rationality on the policy process. Large, decentralized, public organizations such as universities perhaps provide the best illustrations. On most university campuses, decisions emerge from committees which operate largely independently. The energy-saving group may not know what instruments can achieve its goals, while the engineering faculty, fully informed about appropriate devices, may not know that the green committee exists. The committee on standards may want to raise overall admissions qualifications, while the equal opportunity group may be more interested in encouraging applications from minorities. Even within a single group, the position adopted may depend on which people happen to attend a meeting.

Government is of course a classic example of an entity that is both large and decentralized. It is not a single entity but, rather, an array of departments and agencies. Several government departments may deal with different aspects of a problem, with none having an overall perspective. Or one department may be charged with reducing pollution while another works to attract investments in new polluting factories. By considering the garbage-can model, we can see why we should be sceptical about statements beginning ‘the government’s policy is …’.

Clearly, the garbage-can model suggests that real policy-making is far removed from the rigours of rationality. Even on key issues, strong, sustained leadership is needed to impose a coherent response by government as a whole. Many presidents and prime ministers advocate joined-up government but few succeed in vanquishing the garbage-can. Often, rationality is a gloss paint applied to policy after it is agreed.

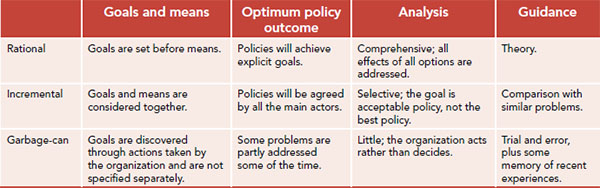

The policy cycle

One way of thinking about public policy is to see it as a cyclical series of stages. This risks painting a picture of an orderly sequence that is unmatched by political reality, but it helps impose some order on a phenomenon that is often enormously complex.There are various ways of outlining the cycle, one of which is to distinguish between initiation, formulation, implementation, evaluation, and review (see Figure 19.1). Of course, these divisions are more analytical than chronological, because – in the real world – they often overlap. So we must keep a sharp eye on political realities and avoid imposing logical sequences on complex realities. Nonetheless, a review of these stages will help to elaborate the particular focus of policy analysis, including its concern with what happens after a policy is agreed.

Initiation and formulation

Policies must start from somewhere, but identifying the point of departure is not easy. What we can say is that in liberal democracies much of the agenda bubbles up from below, delivered by bureaucrats in the form of issues demanding immediate attention. These requirements include the need to fix the unforeseen impacts of earlier decisions, leading to the notion of policy as its own cause (Wildavsky, 1979: 62). For example, once a new highway is opened, additional action will be needed to combat the spillover effects of congestion, accidents, and pollution.

As well as understanding how policies are made, it is also important to understand the tools that government have available. In short, how exactly do governments govern? The answer gives us insight into the complexity of governance.

It might seem as though a legislature can establish a legal entitlement to a welfare benefit, for example, and then arrange for local governments to pay out the relevant sum to those who are eligible. In reality, however, legislation and direct provision are just two of many policy instruments and by no means the most common. Consider the example of efforts to reduce tobacco consumption (Table 19.2). Policy instruments can be classified as sticks (sanctions), carrots (rewards), and sermons (information and persuasion) (Vedung, 1998). Sticks include traditional command-and-control functions, such as banning or limiting the use of tobacco. Carrots include financial incentives such as subsidising the use of nicotine replacement products. Sermons include that stalwart of agencies seeking to show their concern: the public information campaign. The list in the table is by no means comprehensive; Osborne and Gaebler (1992) have identified more than 30 different policy devices.

In addition to these traditional tools, market-based instruments (MBIs) have emerged as an interesting addition to the repertoire of policy instruments. Programmes such as tradable pollution permits and auctions are increasingly used in environmental policy, for example: limits are set on emissions, and companies or countries that fall below the limits can sell the ‘right’ to pollute to those that fail to meet the limits. This way, there is a financial benefit to cutting emissions, and a financial penalty to pay for exceeding the limits. In theory, MBIs resolve the conflict between regulation and markets; they aim to regulate by creating new, if in reality often imperfect, markets (Huber et al., 1998).

Given a range of tools, how should policy-makers choose between them? In practice, instrument selection is strongly influenced by past practice, by national policy styles, and by political factors, such as visibility (something must be seen to be done). Policy-makers can also review questions such as effectiveness, efficiency, equity, appropriateness, and simplicity. Since most policies use a combination of tools, the overall configuration should also be addressed. Instruments should not exert opposite effects and they should form a sequence such that, for example, information campaigns come before direct regulation of behaviour (Salamon, 2002).

TABLE 19.2: Policy instruments: the example of tobacco

FIGURE 19.1: Stages in the policy process

Rather like the development of law, public policy naturally tends to thicken over time; the workload increases, and cases of withdrawal – such as abolishing government regulations – are uncommon. In addition, much political business, including the annual budget, occurs on a regular cycle, dictating attention at certain times. So, policy-makers find that routine business always presses; in large measure, they respond to an agenda that drives itself.

Within that broad characterization, policy initiation differs somewhat between the United States and European (and other party-led) liberal democracies. In the pluralistic world of American politics, success for a proposal depends on the opening of policy windows, such as the opportunities created by the election of a new administration. This policy window creates the possibility of innovation in a system biased against radical change. Thus, Kingdon (2010) suggests that policy entrepreneurs help to seize the moment. Like surfers, these initiators must ride the big wave by convincing the political elite not only of the scale of the problem, but also of the timeliness of their proposal for its resolution.

Policy entrepreneurs: Those who promote new policies or policy ideas, by raising the profile of an issue, framing how it is discussed, or demonstrating new ways of applying old ideas.

From this perspective, interest group leaders succeed by linking their own preferred policies to a wider narrative; try to save the whale and you will be seen, rightly or wrongly, as concerned about the environment generally. Develop proposals for skills training and you will be seen to be addressing the bigger question of economic competitiveness. However, policy openings soon close: the cycle of attention to a particular issue is short, as political debate and the public mood moves on. Concepts such as policy entrepreneur and policy opening carry less resonance in the more structured, party-based democracies of Europe. Here, the political agenda is under firmer, if still incomplete, control, and party man-ifestos and coalition agreements set out a more explicit agenda for government.

Normally, policy-formers operate within a narrow range of options, and will seek solutions which are consistent with broader currents of opinion and previous policies within the sector. Compare American attitudes to medical care with those in the rest of the industrialized world, for example. In the United States, any health care reforms (including those achieved by President Obama) must respect the American preference for private provision. Reformers have faced consistent opposition from labour unions, the medical community, the health insurance industry, and political conservatives. In every other major democracy, by contrast, public health care is entrenched, either in public provision (e.g. Britain’s National Health Service) or more often through collective health insurance schemes.The general point is that policy formulation is massively constrained by earlier decisions in a path dependent fashion.

Implementation

After a policy has been agreed, it must be put into effect – an obvious point, of course, except that much traditional political science stops at the point where government reaches a decision, ignoring the numerous difficulties which arise in putting policy into practice. Probably the main achievement of policy analysis has been to direct attention to these problems of implementation. No longer can execution be dismissed by Woodrow Wilson (1887) as ‘mere administration’. Policy is as policy does.

Turning a blind eye to implementation can still be politically convenient. Often, the political imperative is just to have a policy; whether it works, in some further sense, is neither here nor there. Coalition governments, in particular, are often based on elaborate agreements between parties on what is to be done. This bible must be obeyed, even if its commandments are expensive, ineffective, and outdated.

But there is a political risk in sleepwalking into implementation failure. For example, the British government’s failure to prevent mad cow disease from crossing the species barrier to humans in the late 1980s was a classic instance of this error. Official committees instructed abattoirs to remove infec-tive material from slaughtered cows but, initially, took no special steps to ensure these plans were carried out carefully. As a result of incompetence in slaugh-terhouses, the disease agent continued to enter the human food chain, killing over 170 people by 2012 (Ncjdrsu, 2012). The standing of the government of the day suffered accordingly.

We can distinguish two philosophies of implementation: top-down and bottom-up. The top-down approach represents the traditional view.Within this limited perspective, the question posed is the classical problem of bureaucracy: how to ensure political direction of unruly public servants. Ministers come and go, and find it hard to secure compliance from departments already committed to pet projects of their own. Without vigilance from on high, sound policies can be hijacked by lower-level officials committed to existing procedures, diluting the impact of new initiatives (Hogwood and Gunn, 1984).

This top-down approach focused excessively on control and compliance. As with the rational model of policy-making from which it sprang, it was unrealistic, and even counter-productive. Hence the emergence of the contrasting bottom-up perspective, with its starting point that policy-makers should try to engage, rather than control, those who translate policy into practice. Writers in this tradition, such as Hill and Hupe (2002), ask: what if circumstances have changed since the policy was formulated? And what if the policy itself is poorly designed? Much legislation, after all, is based on uncertain information and is highly general in content. Often, it cannot be followed to the letter because there is no letter to follow.

Top-down implementation: Conceives the task of policy implementation as ensuring that policy execution delivers the outputs and outcomes specified by the policy-makers.

Bottom-up implementation: Judges that those who execute policy should be encouraged to adapt to local and changing circumstances.

Many policy analysts now suggest that objectives are more likely to be met if those who execute policy are given not only encouragement and resources, but also flexibility. Setting one specific target for an organization expected to deliver multiple goals simply leads to unbalanced delivery. Only what gets measured, gets done.

Furthermore, at street level – the point where policy is delivered – policy emerges from interaction between local bureaucrats and affected groups. Here, at the sharp end, goals can often be best achieved by adapting them to local circumstances. For instance, policies on education, health care, and policing will differ between rural areas and the inner city. If a single national policy is left unmodified, its fate will be that of the mighty dragon in the Chinese proverb: no match for the neighbourhood snake.

Further, local implementers will often be the only people with full knowledge of how policies interact. They will know that, if two policies possess incompatible goals, something has to give. They will know the significant actors in the locality, including the for-profit and voluntary agencies involved in policy execution. Implementation is often a matter of building relationships between organizations operating in the field, an art which is rarely covered in central manuals. The idea of all politics being local, quoted in Chapter 11, applies with particular force to policy implementation.

So, a bottom-up approach reflects an incremental view of policy-making in which implementation is seen as policy-making by other means. This approach is also attuned to the contemporary emphasis on governance, with its stress on the many stakeholders involved in the policy process.The challenge is to ensure that local coalitions work for the policy, rather than forming a conspiracy against it.

Evaluation

Just as policy analysis has increased awareness of the importance of policy implementation, so too has it sharpened the focus on evaluation. The task of policy evaluation is to work out whether a programme has achieved its goals and if so how efficiently and effectively.

Public policies, and the organizations created to put them into practice, lack the clear yardstick of profitability used in the private sector. How do we appraise a defence department if there are no wars and, therefore, no win-loss record? Which is the most successful police force: the one that solves the greatest number of crimes, or the one that has the fewest crimes to solve?

Evaluation is complicated further because, as we have seen, goals are often modified during implementation, transforming a failing policy into a different but more successful one. This ‘mushiness of goals’, to use Kettl’s phrase (2011: 287), means that the intent of policy-makers is often a poor benchmark for evaluation. Consider the case of the European Union’s attempts to inject more rapid growth into the European economy. Much was made of the launch in 2000 of the Lisbon Strategy, whose goal was to make the EU ‘the most dynamic and competitive knowledge-based economy in the world within a decade’. It soon became clear that member states were failing to make the necessary changes (such as reducing regulation and opening markets), so the Lisbon Strategy was transformed into the Europe 2020 strategy, changing some of the specific goals and extending the target by a decade.

The question of evaluation has often been ignored by governments. Sweden is a typical case. In the post-war decades, a succession of social democratic administrations concentrated on building a universal welfare state without even conceiving of a need to evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness with which services were delivered by an expanding bureaucracy. In France and Germany, and other continental European countries where bureaucratic tasks are interpreted in legalistic fashion, the issue of policy evaluation still barely surfaces – often to the detriment of long-suffering citizens.

Yet, without some evaluation, governments are unable to learn the lessons of experience. In the United States, Jimmy Carter (president, 1977–81) did insist that at least 1 per cent of the funds allocated to any project should be devoted to evaluation; he wanted more focus on what policies achieved. In the 1990s, once more, evaluation began to return to the fore. For example, the Labour government elected in Britain in 1997 claimed a new pragmatic concern with evidence-based policy: what mattered, it claimed, was what worked. In some other democracies, too, public officials began to think, often for the first time, about how best to evaluate the programmes they administered.

Policy outputs: The actions of government, which are relatively easily identified and measured.

Policy outcomes: The achievements of government, which are more difficult to confirm and measure.

Evaluation studies distinguish between policy outputs and policy outcomes. Outputs are easily measured by quantitative indicators of activities: visits, trips, treatments, inspections. The danger is that outputs turn into targets; the focus becomes what was done, rather than what was achieved. So, outcomes – the actual results – should be a more important component of evaluation. The problem is that outcomes are easier to define than to measure; they are highly resistant to change and, as a result, the cost per unit of impact can be extraordinarily high, with gains often proving to be only temporary. Further, outcomes can be manipulated by agencies seeking to portray their performance in the best light. They have multiple devious devices available to them, including creaming, offloading, and reframing (see Table 19.3).

With social programmes, in particular, a creaming process often dilutes the impact. For example, an addiction treatment centre will find it easiest to reach those users who would have been most likely to overcome their drug use anyway.The agency will want to chalk up as successes cases to which it did not, in fact, make the decisive difference. Meanwhile, the hardest cases remain unreached. Just as regulated companies are usually in a position to outwit their regulator, so too do public agencies finesse measured outcomes using their unique knowledge of their policy sector.

The stickiness of social reality means that attempts to ‘remedy the deficiencies in the quality of human life’ can never be a complete success. Indeed, they can be, and sometimes are, a total failure (Rossi et al., 2003: 6). If our expectations of a policy’s outcomes were more realistic, we might be less disappointed with limited results. So, we can understand why agencies evaluating their own programmes often prefer to describe their impressive outputs, rather than their limited outcomes.

Just as policy implementation in accordance with the top-down model is unrealistic, so judging policy effectiveness against specific objectives is often an implausibly scientific approach to evaluation. A more bottom-up, incremental approach to evaluation has therefore emerged. Here, the goals are more modest: to gather the opinions of all the stakeholders affected by the policy, generating a qualitative narrative rather than a barrage of output-based statistics. As Parsons (1995: 567) describes this approach, ‘evaluation has to be predicated on wide and full collaboration of all programme stakeholders including funders, implementers and beneficiaries’.

In such evaluations, the varying objectives of different interests are welcomed. They are not dismissed as a barrier to objective scrutiny of policy. Unintended effects can be written back into the script, not excluded because they are irrelevant to the achievement of stated goals. This is a more pragmatic, pluralistic, and incremental approach. The stakeholders might agree on the success of a policy even though they disagree on the standards against which it should be judged.The object of a bottom-up evaluation can simply be to learn from the project, rather than to make uncertain judgements of success.

But such evaluations can become games of framing, blaming, and claiming: politics all over again, with the most powerful stakeholder securing the most favourable write-up. To prevent the evaluation of a project from turning into an application for continued funding, evaluation studies should include external independent scrutiny.

Review

Once a policy has been evaluated, or even if it has not, three options are left: continue, revise, or terminate. Most policies – or, at least, the functions associated with them – continue with only minor revisions. Once a role for government is established, it tends to continue, even if the agencies charged with performing the function might change over time, either because a task is split between two or more agencies, or because previously separate functions are consolidated into a single organization (Bauer et al., 2012). So the observation that there is nothing so permanent as a temporary government organization appears to be wide of the mark.

TABLE 19.3: Manipulating policy outcomes

| Definition | Example, using an employment service | |

| Creaming | Give most help to the easiest clients. | Focus on those unemployed clients who are most employable. |

| Offloading | Keep difficult cases off the books, or remove them. | Decline to take on unemployed people with mental health difficulties, or remove them from the list. |

| Reframing | Relabel the category. | Where plausible, remove unemployed people from the labour market by treating them as unemployable or disabled. |

Source: Adapted from Rein (2006)

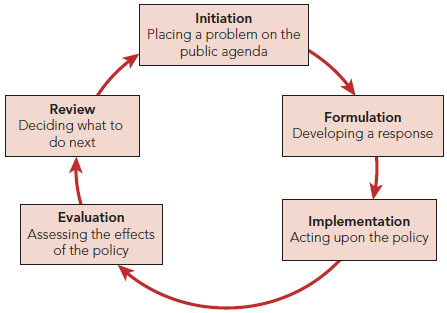

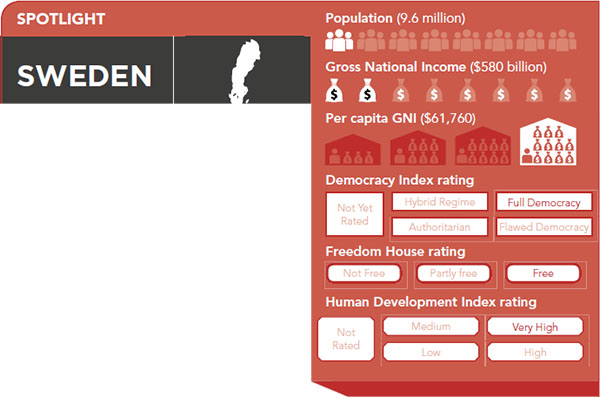

Brief Profile: Sweden ranks at or near the top of international league tables focused on democracy, political stability, economic development, education, and social equality; in this sense, it can be seen as one of the most successful countries addressed in this book. The Social Democrats have held a plurality in the Swedish parliament since 1917, and Sweden traditionally lacked significant internal divisions other than class. However, a recent influx of immigrants and asylum-seekers means that one in six of the population was born in another country (notably Syria), raising integration concerns. Even so, the country combines a high standard of living with a comparatively equal distribution of income, showing – with other Scandinavian states – that mass affluence and limited inequality are compatible. Meanwhile, Sweden is neutral in international affairs, remaining outside NATO but becoming a member of the European Union in 1995.

Form of government  Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy. Date of state formation debatable, and oldest element of constitution dates from 1810.

Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy. Date of state formation debatable, and oldest element of constitution dates from 1810.

Legislature  Unicameral Riksdag (‘meeting of the realm’) with 349 members, elected for renewable four-year terms.

Unicameral Riksdag (‘meeting of the realm’) with 349 members, elected for renewable four-year terms.

Executive  Parliamentary. The head of government is the prime minister, who is head of the largest party or coalition, and governs in conjunction with a cabinet. The head of state is the monarch.

Parliamentary. The head of government is the prime minister, who is head of the largest party or coalition, and governs in conjunction with a cabinet. The head of state is the monarch.

Judiciary  The constitution consists of four entrenched laws: the Instrument of Government, the Act of Succession, the Freedom of the Press Act, and the Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression. The Supreme Court (16 members appointed until retirement at the age of 67) is traditionally restrained.

The constitution consists of four entrenched laws: the Instrument of Government, the Act of Succession, the Freedom of the Press Act, and the Fundamental Law on Freedom of Expression. The Supreme Court (16 members appointed until retirement at the age of 67) is traditionally restrained.

Electoral system  The Riksdag is elected by party list proportional representation, with an additional tier of seats used to enhance proportionality. The national vote threshold (the share of votes needed to be awarded any seats) is 4 per cent.

The Riksdag is elected by party list proportional representation, with an additional tier of seats used to enhance proportionality. The national vote threshold (the share of votes needed to be awarded any seats) is 4 per cent.

Parties  Multi-party. The Social Democrats were historically the leading party, sharing their position on the left with the Left Party and the Greens. However, a centre-right coalition (led by the conservative Moderates and including the Centre Party, the Christian Democrats, and the Liberals) has recently gained ground.

Multi-party. The Social Democrats were historically the leading party, sharing their position on the left with the Left Party and the Greens. However, a centre-right coalition (led by the conservative Moderates and including the Centre Party, the Christian Democrats, and the Liberals) has recently gained ground.

Yet, even if agency termination is surprisingly common, the intriguing question remains: why is policy termination so rare? Why does government as a whole seem to prefer to adopt new functions than to drop old ones? Bardach (1976) suggests five possible explanations:

• Policies are designed to last a long time, creating expectations of future benefits.

• Policy termination brings conflicts which leave too much blood on the floor.

• No one wants to admit the policy was a bad idea.

Public policy in Sweden

Swedish policy-making was once described as ‘open, rationalistic, consensual and extraordinarily deliberative’ (Anton, 1969: 94). Later, Richardson et al. (1982) characterized Sweden’s policy style as anticipatory and consensus-seeking. How do these two interpretations stand up in Sweden today?

They both remain fundamentally correct, from a comparative perspective. Even in a small unitary state with sovereignty firmly based on a unicameral legislature, Sweden has avoided the potential for centralization and has developed an elaborate negotiating democracy which is culturally and institutionally secure.

One factor sustaining this distinctive policy style is the compact size and policy focus of Sweden’s 12 central government departments, which together employ less than 5,000 staff. Their core task is to ‘assist the Government in supplying background material for use as a basis for decisions and in conducting inquiries into both national and international matters’ (Regeringskansliet, 2015). Most technical issues, meanwhile, and the services provided by the extensive welfare state, are contracted out to more than 300 public agencies and to local government. This division of tasks requires extensive collaboration between public institutions, and is sustained by high levels of transparency and trust.

Committees of enquiry (also known as ‘commissions’) are key to policy making. Typically, the government appoints a committee to research a topic and present recommendations. Committees usually comprise a chair and advisers but can include opposition members of the Riksdag, or even – sometimes – just one person. The commission consults with relevant interests and political parties, its recommendations are published and discussed, the relevant ministry examines the report, a government bill is drafted if needed (and presented with a summary of comments received), and the bill is then discussed in the Riksdag, where it may be modified before reaching the statute book. This procedure is slow, but it is also highly rational (in that information is collected and analysed) and incremental (in that organized opponents of the proposal are given ample opportunity to voice their concerns).

There are downsides – extensive deliberation may contribute to bland policy, and the strong emphasis on policy formulation may be at the expense of insufficient focus on implementation – but the style is distinctively Swedish. It offers a useful yardstick against which to compare the less measured policy-making styles found in other liberal democracies.

• Policy termination may affect other programmes and interests.

• Politics rewards innovation rather than tidy housekeeping.

Policy diffusion and convergence

Once, there were no speed limits, no seat belts, no nutritional labels, no restrictions on advertising ciga-rettes, no gender quotas for party candidates, and no state subsidies for political parties. Now, there are. Most democracies have introduced broadly similar policies in these and many other areas – and often at a similar time. So, how did they move in tandem from then to now? The answer lies in a combination of policy diffusion (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996; Rose, 2005) and policy convergence. The former describes the phenomenon of policy programmes spreading from one country to another, though with less emphasis on deliberate emulation than is suggested by related terms such as policy transfer, policy learning, or lesson-drawing. The latter refers to a tendency for policies to become more similar across countries, a phenomenon which can occur without explicit diffusion if different countries just respond to common problems (e.g. an ageing population) in a similar way (e.g. raising the age of retirement). Both diffusion and convergence usefully address the comparative dimension in public policy analysis.

Policy diffusion: The tendency for policy programmes to spread across countries.

Policy convergence: The tendency for policies in different countries to become more alike.

Although policy diffusion has attracted attention as an example of international influence on national policy, examples of countries clearly emulating innovations from abroad remain thin on the ground. In theory, the whole world could be a laboratory for testing policy innovation; in practice, most policy-making still runs in a national groove. How, then, do we explain why convergence occurs without explicit emulation? In other words, why do democracies adopt broadly similar policies in the same time period without the self-aware learning from abroad that policy convergence suggests?

A useful point of departure is offered by Rogers (2003), whose analysis distinguishes between a few innovators and early adopters, the majority (divided into two groups by time of adoption), and a small number of laggards, with non-adopters excluded (see Figure 19.2). Although not designed with cross-national policy diffusion in mind, this analysis allows us to interpret the spread of a particular policy and to ask why certain countries are innovators, either in a particular case, or in general. Innovation is perhaps most likely to emerge in high-income countries with (a) the most acute manifestation of a specific problem, (b) the resources to commit to a new policy, and (c) the governance capacity to authorize and deliver. A new government with fresh ideas and a desire to make its mark is an effective catalyst.

Knill and Tosun (2012: 275) identify a series of factors encouraging policy convergence (Table 19.4).

FIGURE 19.2: The diffusion of innovation Source: Adapted from Rogers (1962)

Of these, independent problem-solving is one of the more significant: as countries modernize, they develop similar problems calling for a policy response. At an early stage of development, for example, issues such as urban squalor, inadequate education, and the need for social security force themselves onto the agenda. The problems of development come later: the epidemic of obesity, for example, or the rising social cost of care for the elderly. In national responses to such difficulties, we often see policy-making in parallel, rather than by diffusion. Even if the response in one country is influenced by policy innovations elsewhere, it is still the need to respond to domestic problems that drives policy.

TABLE 19.4: Mechanisms for policy convergence

| Effect | Example | |

| Independent problem-solving | As countries develop, similar problems emerge, often resulting in similar policies. | Under-regulated industrialization leads to air and water pollution. |

| International agreements | National policies converge as countries seek to comply with international laws, regulations, and standards. | Membership of the World Trade Organization imposes common rules on member states. |

| International competition | Policies providing an economic or political advantage will be replicated elsewhere. | Privatization of state-owned enterprises has spread throughout the developed world, with New Zealand and the UK among the innovators. |

| Policy learning | Explicit lesson-drawing can occur even when no competitive advantage ensues. | Capital punishment is abolished because evidence from other countries indicates a limited impact on crime rates. |

| Coercion and conditionality | One country makes policy requirements of another, for example in return for aid. | Reforms imposed on Greece initially in 2010, in return for financial help in responding to the debt crisis. |

Source: Adapted from Knill and Tosun (2012: table 11.5)

In addition, policy convergence can result from conformity to the ever-expanding array of international agreements. Covering everything from the design of nuclear reactors to the protection of prisoner rights, these are agreed by national governments and monitored by intergovernmental organizations. Signing up to such agreements is voluntary, and the content may be shaped by the strongest states (the standard-makers rather than the standard-takers), but international norms remain a strong factor in encouraging policy convergence.

Moving beyond formal international regulation, international competition generates pressures to emulate winning policies. Here, an expanding supply of league tables produced by international bodies provides benchmarks that can have the effect of nudging governments in the direction favoured by the producer. One of those is the World Bank’s Doing Business Index, which ranks countries based on criteria such as the ease of starting a business, registering a property, and securing an electricity supply. Table 19.5 lists the top ten countries in the 2014 league, along with the other cases used in this book, and – for context – last-placed Eritrea.

In the competition for foreign direct investment, for instance, what government would want to occupy a lowly position in the World Bank’s table? Note, however, that there is more than one way to skin a rabbit. In seeking overseas investment, some governments emphasize workforce quality (a race to the top), while others give priority to low labour costs (a race to the bottom). Competition generates similar pressures but not identical policies; rather, it encourages countries to exploit their natural advantages, yielding divergence, rather than convergence.

The fourth mechanism behind policy convergence is direct policy learning, which may also be the weakest such mechanism. Governments do not select from a full slate of options but must operate in the context of national debates and their own past decisions. So, tweak-ing is more common than wholesale copying, and three conditions apply:

• Foreign models are only likely to be considered seriously when the domestic agenda seems to be incapable of resolving a problem. Even then, the search will not be global but will focus on similar or neighbouring countries with which the learning country has a long-standing and friendly relationship.

• Policies themselves often evolve in the process of dif-fusion; they are translated rather than transported. Even if a government does cite foreign examples, it may be to justify a policy adopted for domestic political reasons. In general, governments find it more difficult to learn than do individuals.

• Lesson-drawing can be negative as well as positive, because models to avoid are generally more visible than those worth emulating. Germany’s hyper-inflation in the 1920s and Japan’s lost decades of the 1990s and 2000s continue to offer warnings that influence economic policy-makers throughout the developed world, while few countries have shown a desire to reproduce Britain’s National Health Service, with its delivery of medical care through a gigantic nationalized industry.

TABLE 19.5: The Doing Business Index

| Country | |

| 1 | Singapore |

| 2 | New Zealand |

| 3 | Hong Kong* |

| 4 | Denmark |

| 5 | South Korea |

| 6 | Norway |

| 7 | United States |

| 8 | UK |

| 9 | Finland |

| 10 | Australia |

| 14 | Germany |

| 16 | Canada |

| 29 | Japan |

| 31 | France |

| 39 | Mexico |

| 43 | South Africa |

| 62 | Russia |

| 90 | China |

| 112 | Egypt |

| 120 | Brazil |

| 130 | Iran |

| 142 | India |

| 170 | Nigeria |

| 189 | Eritrea |

* Hong Kong often appears in league tables of this kind, even though it is not an independent state, but a Special Administrative Region of China.

Source: Doing Business (2015). Data are for 2014.

While Knill and Tosun do not include this in their list, coercion and the imposing of conditions by one country on another can also be an important element in policy convergence. In extreme cases, victory in war allows the dominant power to impose its vision on vanquished states, as with the forced construction of democracy in Germany and Japan by the victorious allies after the Second World War. More commonly, economic vulnerability gives weak countries little choice but to submit to more powerful countries and to international organizations. For example, the practice of attaching strings to aid became an important theme in international politics in the 1990s, after many developing countries had become massively indebted to Western banks. Similarly, international creditors including the International Monetary Fund sought to impose challenging reforms on Greece in 2010 in an effort to reduce that country’s severe financial indebtedness. The difficulty with coercion as a policy-shaping instrument is that the receiving country may lack genuine commitment to the reforms, leading to their failure over the long term.

One conclusion is that we should think in terms of the diffusion of ideas rather than policies. Even if policies remain attached to national anchors, ideas – at least for stronger states – know no boundaries. Broad agendas (where do we need policy?) and frameworks (how should we think about this area?) are often transnational in character and refined by discussions in international organizations. Ideas provide a climate within which national policies are made, whether or not national policy-makers are aware of this influence. In public policy, as in politics generally, ideas matter even if their influence is difficult to analyse on other than a case-by-case basis.

Public policy in authoritarian states

The central theme in the policy process of many non-democratic regimes is the subservience of policy to politics. Often, the key task for non-elected rulers is to play off domestic political forces against each other so as to ensure their own continuation in office. Uncertain of their own long-term survival in office, authoritarian rulers may want to enrich themselves, their family, and their support group while they remain in control of the state’s resources. These related goals of political survival and personal enrichment are hardly conducive to orderly policy development. As Hershberg (2006: 151) says:

To be successful, policies must reflect the capabilities – encompassing expertise, resources and authority – of the institutions and individuals charged with their implementation.Those capabilities are more likely to be translated into effective performance in environ-ments characterized by predictable, transparent and efficient procedures for reaching decisions and for adjudicating differences of interest.

But it is precisely these ‘predictable, transparent and efficient procedures’ that authoritarian regimes are often unable to supply. Frequently, opaque patronage is the main political currency; the age-old game of creating and benefiting from political credits works against clear procedures of any kind.The result is a conservative preference for the existing rules of the game, an indifference to policy and a lack of interest in national development. As Chazan et al. (1999: 171) note in discussing Africa, ‘patriarchal rule has tended to be conservative: it propped up the existing order and did little to promote change. It required the exertion of a great deal of energy just to maintain control’.

In addition, rulers may simply lack the ability to make coherent policy. As a group, authoritarian rulers are less well-educated than the leaders of liberal democracies. This weakness was especially common in military regimes whose leaders frequently lacked formal education and managerial competence. The generals sometimes seized power in an honest attempt to improve public policy-making but then discovered that good governance required skills they did not possess.

Policy inertia is therefore often a standard pattern under authoritarian rule. Stagnation is reinforced when, as in many of the largest non-democracies, the rulers engage in rent-seeking, often using their control over natural commodities such as oil or rare minerals as their main source of revenue. For example, government officials might take bribes to provide a licence to a company, or a passport to a citizen, benefiting both buyer and seller, but imposing a hidden tax on the economy and society. In these circumstances, the government need not achieve the penetration of society required to collect taxes, expand the economy, and develop human capital. Rather, a stand-off of mutual distrust develops between rulers and ruled, creating a context which is incompatible with the more sophisticated policy initiatives found in many liberal democracies. In the absence of effective social policy at national level, problems of poverty, welfare, and medical care are addressed locally, if at all.

A particular problem that skews policy in several authoritarian states is the so-called resource curse (Auty, 1993; Collier and Bannon, 2003). This exists when a country is particularly well-endowed in a resource that could and should be the foundation for economic development, but instead alters the economic and political balance such as to reduce economic growth below the expected level. Oil has turned out to be just such a problem for several sub-Saharan African states, such as Nigeria, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Chad, and Sudan. It is also a factor in countries rich in easily exploitable minerals such as copper or uranium, or in precious gems such as diamonds.

The policy element of the ‘curse’ stems from four main factors:

• Because these resources are usually relatively easy to exploit and can bring quick and often profitable returns, a state will focus its development efforts almost entirely in that sector, investing little in other sectors; this is the so-called ‘Dutch disease’, named for the effects of the discovery of natural gas in the North Sea off the coast of the Netherlands in the 1970s (Humphreys et al., 2007). It will thereby have an imbalanced economy and will become dependent on a product whose value may be held hostage to fluctuations in its price on the international market.

• When a government can raise adequate revenue from simply taxing a major natural resource, it lacks incentive to improve economic performance by developing the skills of its people, thus damaging growth over the long run.

• The profits that come from these commodities can encourage theft and corruption, ensuring that they find their way into the bank accounts of the rich and powerful rather than being reinvested back into the community.

• The effect of the curse is to encourage internal conflict, when poorer regions of the country find that they are not benefiting equally from the profits of resources found in other parts of the country. In the most extreme cases, it can lead to violence and civil war.

Resource curse: A phenomenon by which a state that is well-endowed in a particular natural resource, or a limited selection of resources, nonetheless experiences low economic growth. Unbalanced policy, extensive corruption and internal conflict all contribute to the resource curse.

Rent-seeking: Seeking to make an income from selling a scarce resource without adding real value.

The absence of an extensive network of voluntary associations and interest groups in authoritarian states prevents the close coordination between state and society needed for effective policy-making and implementation. The blocking mechanism here is fear among rulers as much as the ruled. Saich (2015: 199) identifies these anxieties in the case of China’s party elite:

While it is true that public discourse is breaking free of the codes and linguistic phrases established by the party-state, it is also clear that no coherent alternative vision has emerged that would fashion a civil society. From the party’s point of view, what is lurking in the shadows waiting to pounce on any opening that would allow freedom of expression is revivalism, religion, linguistic division, regional and non-Han ethnic loyalties.

As always, however, it is important to distinguish between different types of authoritarian government. At one extreme, many military and personal rulers show immense concern about their own prosperity but none at all for that of their country, leading to a policy short-age. At the other extreme, modernizing regimes whose ruling elite displays a clear sense of national goals and a secure hold on power follow long-term policies, especially for economic development. Such countries do not suffer from inertia, but instead find it easier to push through substantial policy change, because they can suppress the short-term demands that would arise in a more open political system.

China offers an example of the latter approach. It survives as an authoritarian regime partly because it pursues policies leading to rapid economic development. The capacity of the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party to form and implement coherent policy in the world’s most populous country is a remarkable achievement. It owes much to political flexibility, the country’s authoritarian tradition, and the legitimacy the regime has derived from economic growth. The leadership’s sensitivity to public concerns, unusual in authoritarian regimes, is seen not only in the achievement of economic development but also in attempts to limit its unequal consequences. For example, the party’s 2006 programme, Building a Harmonious Society, sought to reduce income inequality, improve access to medical care for rural-dwellers and urban migrants, extend social security, and contain the environmental damage from industrialization (Saich, 2015).

The story in Russia has been different. After the initially chaotic transition from communism, the country’s rulers achieved considerable policy successes. A more predictable environment was created for business investment, a recentralization of power encouraged the more uniform application of a newly codified legal system, tax revenues improved, and social policy became more coherent with a controversial 2005 reform that replaced the bulk of Soviet-era privileges (such as free or subsidised housing, transportation, and medicine) with ‘supposedly equivalent cash payments’ (Twigg, 2005: 219).

But policy-making remains subject to the political requirements of the ruling elite. Industrialists who pose a political threat to President Putin still find that numerous rules and regulations are invoked selectively against them. The state has disposed of many enterprises but rent-seeking continues; the government has tightened its control over the oil and gas industries, political and economic power remain tightly interwoven, precluding – at the highest level – uniform policy implementation, and public control of export commodities enables the Russian elite to sustain its own position even if it neglects the development of closer connections with the Russian population. Meanwhile, social problems such as poverty, alcoholism, violent crime, and rural depopulation remain deep-rooted.

As in many poor countries, even-handed policy implementation is impossible in Russia because many public officials are so poorly paid that corruption remains an essential tool for making ends meet. It may be true that sunlight is the best disinfectant, but the improved policy process enabled by an escape from corruption and rent-seeking cannot be achieved simply by calling for more transparency.The dilemma is that transparency flows naturally from broad-based economic development, but such development itself requires a reduction in corruption.

• Which of the three models of the policy process oêrs the most insight into the policy process, and how does their utility vary by policy issue?

• Which policy instruments are likely to be most eêctive in reducing (a) obesity, (b) drug addiction, (c) texting while driving, and (d) climate change?

• What additional steps, if any, would you add to the policy cycle?

• Given the uncertainties of policy-making, why do politicians keep making unrealistic promises, and why do voters keep accepting them?

• Why does policy often fail to achieve its objectives?

• Can you identify any public policies in your country which were (a) adapted from, or (b) inůenced by, policies in other countries?

KEY CONCEPTS

Bottom-up implementation

Cost–benefit analysis

Garbage-can model

Incremental model

Policy analysis

Policy convergence

Policy diffusion

Policy entrepreneurs

Policy outcomes

Policy outputs

Public policy

Rational model Rent-seeking

Resource curse Top-down implementation

FURTHER READING

Birkland,Thomas A. (2010) An Introduction to the Policy Process:Theories, Concepts and Models of Public Making, 3rd edn. A thematic introduction to public policy with a particular focus on policy stages.

Dodds, Anneliese (2013) Comparative Public Policy. A survey of comparison in public policy, with chapters on specific issues such as economic, welfare and environmental policy.

Eliadis, Pearl, Margaret M. Hill, and Michael

Howlett (eds) (2005) Designing Government: From Instruments to Governance.This book provides a detailed examination of policy instruments.

Knill, Christoph and Jale Tosun (2012) Public Policy: A New Introduction. A thematic overview of public policy, emphasizing theories and concepts.

Rose, Richard (2005) Learning from Comparative Public Policy: A Practical Guide. An influential examination of how countries can learn from each other about the successes and failures of policy initiatives.

Sabatier, Paul A. and Christopher M. Weible (eds) (2014) Theories of the Policy Process, 3rd edn. A survey and comparison of theoretical approaches to the policy process.