Ile de la Cité and the Latin Quarter

Virtual Tour of Notre-Dame’s Interior

4 Deportation Memorial (Mémorial de la Déportation)

8 Shakespeare and Company Bookstore

13 Cité “Métropolitain” Métro Stop

14 Conciergerie

Paris has been the cultural capital of Europe for centuries. We’ll start where it did, on Ile de la Cité, with a foray onto the Left Bank, on a walk that laces together 80 generations of history—from Celtic fishing village to Roman city, bustling medieval capital, birthplace of the Revolution, bohemian haunt of the 1920s café scene, and the working world of modern Paris. Along the way, we’ll marvel at two of Paris’ greatest sights—Notre-Dame and Sainte-Chapelle. Expect changes in the area around Notre-Dame as the cathedral undergoes reconstruction in the wake of the 2019 fire.

Length of This Walk: Allow 2 hours to do justice to this three-mile walk (allow 4 hours if you go into the Sainte-Chapelle and the Conciergerie). This is the most historically important walk you’ll do in Paris, so don’t rush it. Take breaks at any number of appealing cafés and bistros along the way.

Getting There: The closest Métro stop is Cité (actually on the island).

Paris Museum Pass: Some sights on this walk are covered by the time- and money-saving Paris Museum Pass (see here).

Notre-Dame: Due to the 2019 fire, only the cathedral’s exterior is viewable. The interior is closed (may reopen later in 2024), and some nearby areas may be blocked off. For updates, see www.notredamedeparis.fr (select “Visiter”—website is in French only). Binoculars are helpful to view the church exterior (as well as Sainte-Chapelle’s stained-glass windows).

Paris Archaeological Crypt: €9, covered by Museum Pass, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, enter 100 yards in front of cathedral, www.crypte.paris.fr.

Espace Notre-Dame: In the Heart of the Restoration exhibit-free, 45-minute Eternelle Notre-Dame virtual reality experience-€35, both open Tue-Sun 10:00-20:00, closed Mon, entrance is 30 yards behind the Paris Archaeological Crypt as you face Notre-Dame, www.eternellenotredame.com.

Deportation Memorial: Free, daily 10:00-19:00, Oct-March until 17:00, may close at random times, free 45-minute audioguide and guided tours may be available, at east tip of Ile de la Cité, behind Notre-Dame, +33 6 14 67 54 98.

Shakespeare and Company Bookstore: Daily 10:00-22:00, 37 Rue de la Bûcherie, across the river from Notre-Dame, Mo: St-Michel, +33 1 43 25 40 93.

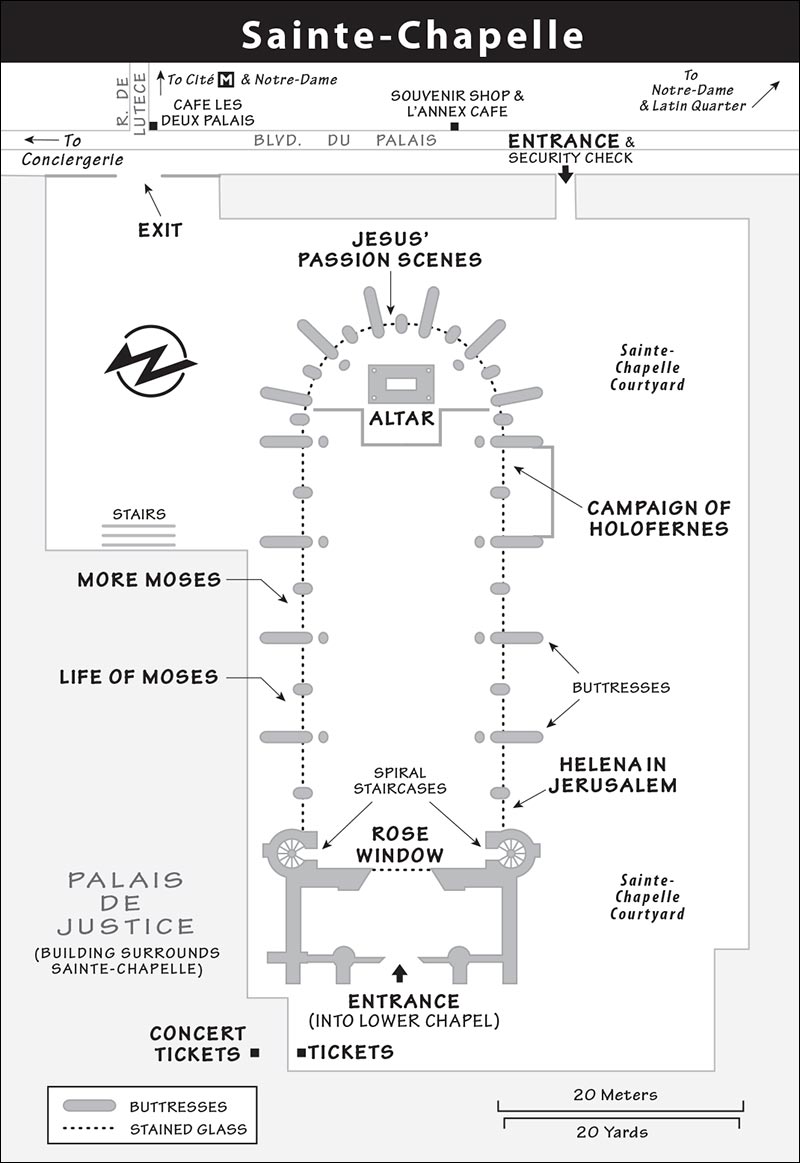

Sainte-Chapelle: €11.50 timed-entry ticket, €18.50 combo-ticket with Conciergerie, free for those under 18, covered by Museum Pass, reserve online in advance to ensure entry (limited tickets may be available in person); daily 9:00-19:00, Oct-March until 17:00; audioguide-€3, evening concerts—see here, 4 Boulevard du Palais, Mo: Cité, +33 1 53 40 60 80, www.sainte-chapelle.fr.

Expect long lines to get in. First comes the security line (sharp objects and glass confiscated). Next, you’ll encounter the ticket-buying line—but Museum Pass, combo, and advance ticket holders can skip this queue.

Conciergerie: €11.50 (timed-entry tickets available but not necessary), €18.50 combo-ticket with Sainte-Chapelle, covered by Museum Pass; daily 9:30-18:00, free multimedia guide, 2 Boulevard du Palais, Mo: Cité, +33 1 53 40 60 80, www.paris-conciergerie.fr.

Avoiding Crowds: This area is most crowded from midmorning to midafternoon, especially on Tue (when the Louvre is closed) and on weekends. Generally, come early or as late in the day as possible (while still leaving enough time to visit all the sights).

Sainte-Chapelle has limited space, and bottlenecks to get in are the norm. Its security lines are shortest first thing in the morning, so try for an early reservation. Lacking a reservation, arrive by 9:00 to inquire about available entry times, or arrive late and cross your fingers.

Tours:  Download my free Paris Historic Walk audio tour.

Download my free Paris Historic Walk audio tour.

Services: Find WCs at Sainte-Chapelle, the Conciergerie, Espace Notre-Dame, and at cafés.

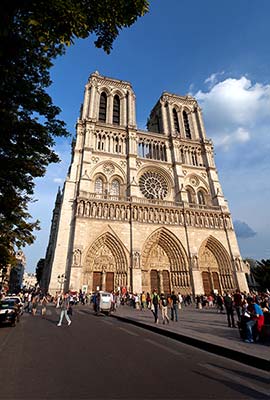

• Start in front of Notre-Dame Cathedral, the physical and historic bull’s-eye of your Paris map. Some areas around the cathedral are blocked off as reconstruction continues. Find a place where you can take in the whole scene: the church, the square (Place du Parvis), the cityscape, and visitors from around the globe. You’re standing near the center of France: The small bronze plaque called “Point Zero” (embedded in the ground, 30 yards in front of the church—may not be visible) is the point from which all distances are measured. And you’re looking at the symbolic heart of France. As you take it all in, ponder this spot’s long, venerable, and vulnerable history.

Centuries from now, people standing here will still talk about the night of April 15, 2019, when Notre-Dame Cathedral went up in flames. That disastrous event is just one more episode in the long and fascinating story of Paris.

Think of the changes this site has seen over the years. About 2,300 years ago, there was virtually nothing here at all. This was the humble island where the Parisii tribe lived, caught fish, and sold their catch at the place where the east-west river crossed a north-south road. When the Romans conquered the Parisii, they built their Temple of Jupiter where Notre-Dame stands today (52 BC). When Rome fell, the Germanic Franks sealed their victory by replacing the temple with the Christian church of St. Etienne. Around the year 800, the Frankish King Charlemagne (see his big equestrian statue to the right of the church) established the first glimmers of modern “France.”

By the year 1200, visitors standing here would have seen (as we do today) a construction zone. The old Frankish church was being torn down and replaced with a more glorious structure renamed “Notre-Dame.” Soon it was topped with a pointy spire atop the roof and two never-completed steeples in front (the two stubby bell towers we see today).

By 1800, if you were still standing here, you’d be exhausted, but you’d also see a crumbling church weathered by the ages and neglect. The central spire had been removed (for fear it would fall over), and there were virtually no statues on the facade (having been damaged during the Revolution). The square in front was a tangle of ramshackle medieval buildings, with Notre-Dame’s bell towers rising above, inspiring Victor Hugo’s story of a deformed bell-ringer who could look down on all of Paris. (The instant success of that book helped rally public interest in saving the building.)

In 1844, a 30-year-old architect named Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc began a massive renovation in the Neo-Gothic style. He put a new 300-foot spire atop the roof (echoing the original), and added more statues, including the fanciful gargoyles.

After 800 years of work, Notre-Dame had become a truly glorious structure, the most famous Gothic church in the world. That was the church that stood here in 2019 when it caught fire...and Paris began another chapter in its story.

• In fact, much of the history of Paris still lies buried in front of the cathedral. Some has been unearthed and put on display in the Archaeological Crypt (across the square from the cathedral; see here). Behind the crypt, the Espace Notre-Dame offers two activities: an exhibit on the restoration project and an excellent virtual reality experience called Eternelle Notre-Dame (both described on here). Now turn your attention to the church.

Despite the 2019 fire, the main body of the church still stands. We’ll get a better look at the damaged parts later, but for now, focus on the still-breathtaking facade.

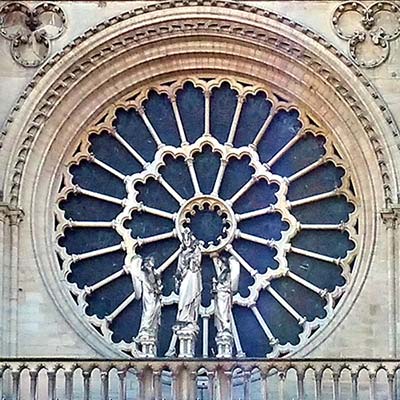

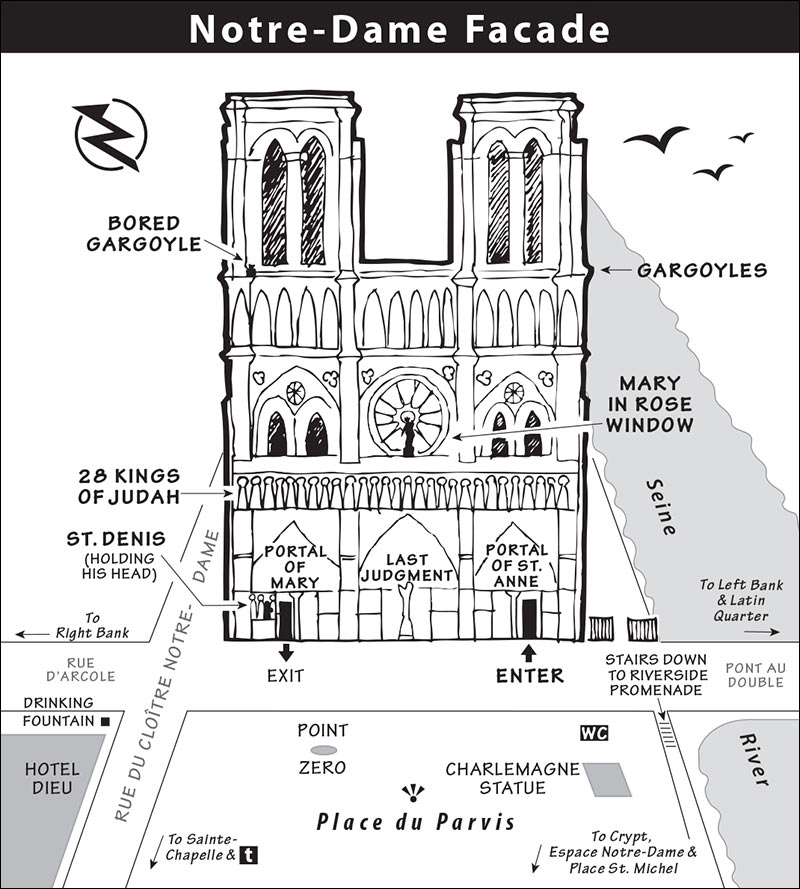

Find the circular window in the center of the facade, which frames a statue of a woman holding a baby. For centuries, the main figure in the Christian pantheon has been Mary, the mother of Jesus. Catholics petition her in times of trouble to gain comfort, and to ask her to convince God to be compassionate with them. This church is dedicated to “Our Lady” (Notre-Dame), and there she is, cradling God, right in the heart of the facade, surrounded by the halo of the rose window. Though the church is massive and imposing, it has always stood for the grace and compassion of Mary, the “mother of God.”

Imagine the faith of the people who built this cathedral. They broke ground in 1163 with the hope that someday their great-great-great-great-great-great grandchildren might attend the dedication Mass, which finally took place two centuries later, in 1345. Look up the 200-foot-tall bell towers and imagine a tiny medieval community mustering the money and energy for construction. Master masons supervised, but the people did much of the grunt work themselves for free—hauling the huge stones from distant quarries, digging a 30-foot-deep trench to lay the foundation, and treading like rats on a wheel designed to lift the stones up, one by one. This kind of backbreaking, arduous manual labor created the real hunchbacks of Notre-Dame.

• Looking two-thirds of the way up Notre-Dame’s left tower, you might spot Paris’ most photographed gargoyle (see drawing above). Propped on his elbows on the balcony rail, he watches all the tourists below.

Now, approach closer to the cathedral (as best you can with the construction barriers) to view the statues adorning the church’s left portal. The lower facade may still not be viewable when you visit; you’ll have to use your imagination until the scaffolding is removed.

Flanking the left doorway is a man with a misplaced head—that’s St. Denis, the city’s first bishop and patron saint. He stands among statues of other early Christians who helped turn pagan Paris into Christian Paris.

Sometime in the third century, Denis came here from Italy to convert the Parisii. He settled here on the Ile de la Cité, back when there was a Roman temple on this spot and Christianity was suspect. Denis proved so successful at winning converts that the Romans’ pagan priests beheaded him as a warning to those forsaking the Roman gods. But those early Christians were hard to keep down. The man who would become St. Denis got up, tucked his head under his arm, headed north, paused at a fountain to wash it off, and continued until he found just the right place to meet his maker: Montmartre. The Parisians were convinced by this miracle, Christianity gained ground, and a church soon replaced the pagan temple.

Medieval art was OK if it embellished the house of God and told biblical stories. Find the base of the central column (at the foot of Mary, about where the head of St. Denis could spit if he were really good). Working around from the left, find God telling a barely created Eve, “Have fun, but no apples.” Next, the sexiest serpent I’ve ever seen makes apples à la mode. Finally, Adam and Eve, now ashamed of their nakedness, are expelled by an angel. This is a tiny example in a church covered with meaning.

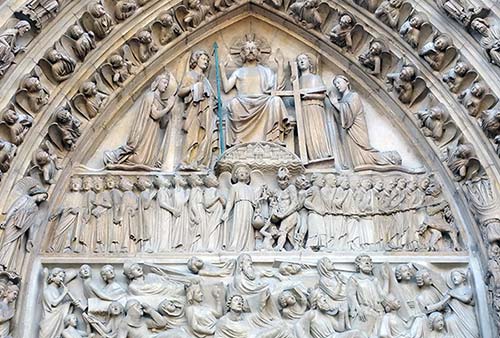

• Now, get as close as you can to the central doorway. Over the door are scenes from the Last Judgment.

It’s the end of the world, and Christ sits on the throne of judgment (just under the arches, holding both hands up). Beneath him an angel and a demon weigh souls in the balance; the demon cheats by pressing down. It’s a sculptural depiction of the good, the bad, and the ugly. The good souls stand to the left, gazing up to heaven. The bad souls to the right are chained up and led off to a six-hour tour of the Louvre with a lousy guide on a hot summer day. The ugly souls must be the crazy, sculpted demons just below.

On the arch to the right there’s a flaming cauldron with the sinner diving into it headfirst. The lower panel (beneath the chain of souls) shows angels with trumpets waking the dead from their graves. The souls are from every class of French society—knights, ladies, peasants, clergy, even royalty—reminding all who entered these doors that everyone will be judged. Fortunately, Jesus (who stands below, between the double doors) can lead the way to salvation, along with his 12 apostles—each barefoot and with his ID symbol (such as Peter with his keys).

• Now look higher. Above the doorway arches and scaffolding, you should be able to see a row of 28 statues, known as...

In the days of the French Revolution (1789-1799), these biblical kings were mistaken for the hated French kings, and Notre-Dame represented the oppressive Catholic hierarchy. The citizens stormed the church, crying, “Off with their heads!” Plop—they lopped off the crowned heads of these kings with glee, creating a row of St. Denises that weren’t repaired for decades.

But the story doesn’t end there. A schoolteacher who lived nearby collected the heads and buried them in his backyard for safekeeping. There they slept until 1977, when they were accidentally unearthed. Today, you can stare into the eyes of the original kings in the Cluny Museum, a few blocks away.

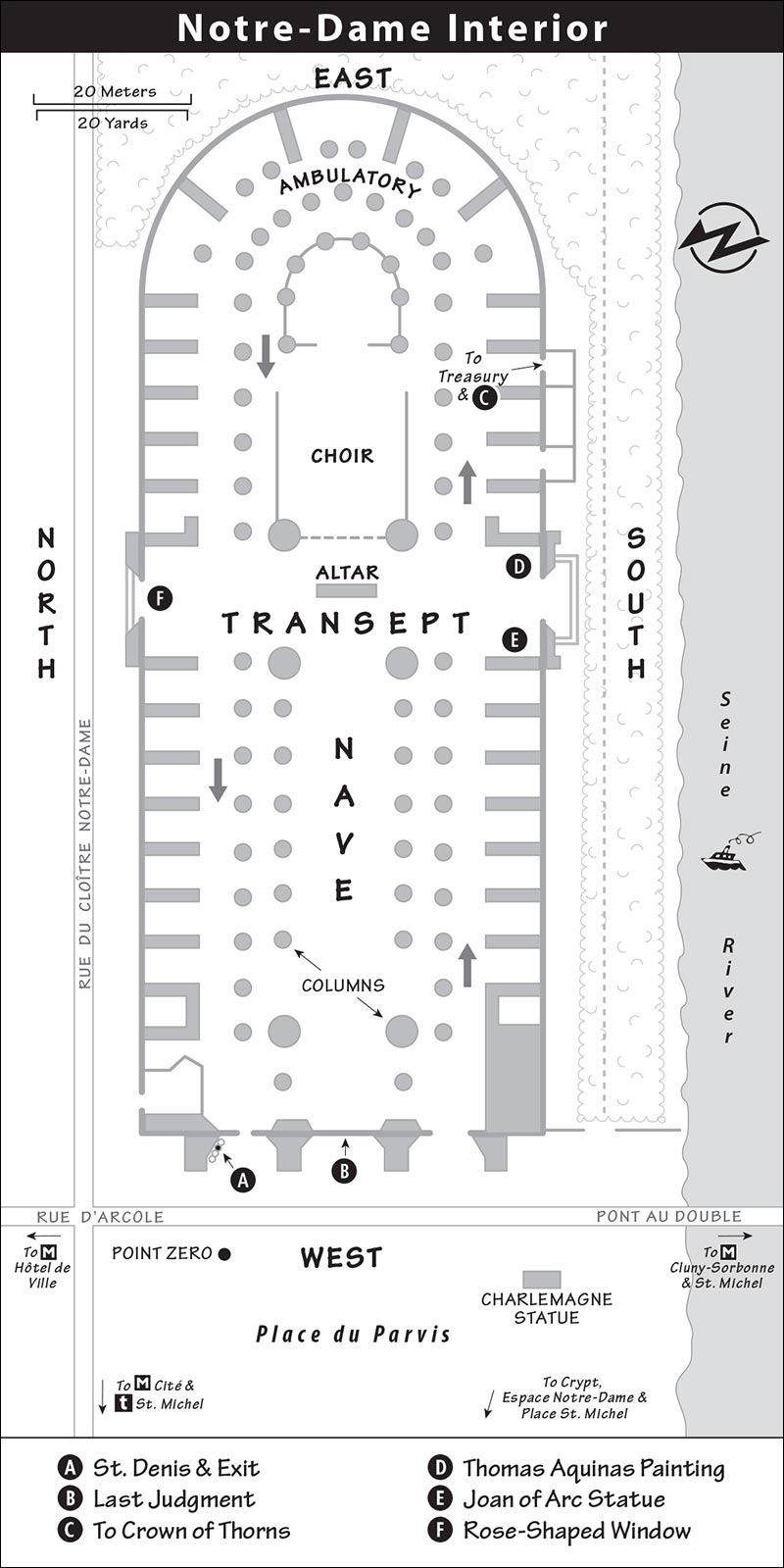

• Remember that Notre-Dame is more than a tourist sight—it’s been a place of worship for nearly a thousand years. By late 2024, the church’s interior may be open to visitors again. If still closed during your visit, shut your eyes and imagine the church in all its glory. Remove your metaphorical hat and mentally “step inside” the church, to take a...

“Enter” the church like a simple bareheaded peasant of old (referring to the modern “Notre-Dame Interior” map). Imagine stepping into a dark, earthly cavern lit with an unearthly light from the stained-glass windows. The priest intones the words of the Mass that echo through the hall. Your eyes follow the slender columns up 10 stories to the praying-hands arches of the ceiling. Walk up the long central nave lined with columns and flanked by side aisles. The place is huge—it can hold up to 10,000 faithful for a service.

When you reach the altar, you’re at the center of this cross-shaped church, where the faithful receive the bread and wine of Communion. This was the holy spot for Romans, Christians...and even atheists. When the Revolutionaries stormed the church, they gutted it and turned it into a “Temple of Reason,” complete with a woman dressed like Lady Liberty holding court at the altar.

If you were able to browse around the church, you’d see it’s become a kind of Smithsonian for artifacts near and dear to the heart of the Parisian people. There’s the venerated Crown of Thorns that supposedly Jesus wore (kept safely in the Treasury). There’s the gilded-and-enameled reliquary dedicated to St. Geneviève (fifth century), whose prayers saved Paris from Attila the Hun. A painting honors the scholar Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), who studied at the University of Paris while writing his landmark theological works fusing faith and reason. There’s a statue of Joan of Arc, the teenager who rallied her country to drive English invaders from Paris. (Though she was executed, the former “witch” was later beatified—right here in Notre-Dame.)

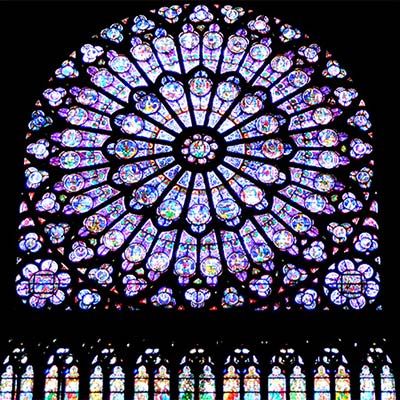

The oldest feature inside the church is the blue-and-purple rose-shaped window in the north transept—still with its original medieval glass, though not viewable. (To experience an intact Gothic interior, visit St. Eustache Church, near the Forum des Halles market—see here). Finish your virtual visit by pausing at one of the many chapels. Here the faithful can pause in your mental tour to meditate and light a (virtual) candle in hopes that someday soon the interior will be restored to its former glory.

• Back to reality. Let’s circle around the left (north) side of the church, walking down the street called...

As you head toward the back of the church, you’ll pass fascinating information panels describing (in English) the fire and its aftermath, the recovered rooster from the steeple’s top, and the restoration process. You’ll also get up-close views of the building. Notice gaps where stained-glass windows were removed—each panel is being tested for lead to ensure they’re safe for restoration work to begin. Get close to a flying buttress, now supported by wooden structures.

• Keep going past the church. (Don’t worry, we’ll get another classic look at Notre-Dame later, from just across the river.) After passing the area behind the cathedral, pause for a moment on the arched pedestrian-only bridge, Pont St. Louis, for a look at...

If Ile de la Cité is a tugboat laden with the history of Paris, it’s towing this classy little residential dinghy, laden only with high-rent apartments, boutiques, characteristic restaurants, and famous ice cream shops.

Ile St. Louis wasn’t developed until the 17th century, much later than Ile de la Cité. What was a swampy mess is now harmonious Parisian architecture and one of Paris’ most exclusive neighborhoods.

Now look upstream (east) to the bridge (Pont Tournelle) that links Ile St. Louis with the Left Bank (which is now on your right). Where the bridge meets the Left Bank, you’ll find one of Paris’ most exclusive restaurants, La Tour d’Argent (with a flag flying from the rooftop). This restaurant was the inspiration for the movie Ratatouille. Because the top floor has floor-to-ceiling windows, your evening meal comes with glittering views—and a golden price (€200 minimum). But, you get a photo of yourself dining elegantly with Notre-Dame in the background (not quite so elegant while covered in scaffolding).

Ile St. Louis is a lovely place for an evening stroll (for details, see the Entertainment in Paris chapter). If you won’t have time to come back later, consider taking a brief detour across the pedestrian bridge, Pont St. Louis, to explore this little island.

• Let’s head toward the Left Bank. Do an about-face and start walking south (with the backside of Notre-Dame on your right). Enter the little grassy park to your left, where (behind a tall green hedge) you’ll find the...

This memorial to the 200,000 French victims of the Nazi concentration camps (1940-1945) draws you into their experience. France was quickly overrun by Nazi Germany, and Paris spent the war years under Nazi occupation. Jews and dissidents were rounded up and deported—many never returned.

As you descend the steps, the city around you disappears. Surrounded by walls, you have become a prisoner. Your only freedom is your view of the sky and the tiny glimpse of the river below. Enter the dark, single-file chamber up ahead. Inside, the circular plaque in the floor reads, “They went to the end of the earth and did not return.”

The hallway stretching in front of you is lined with 200,000 lighted crystals, one for each French citizen who died. Flickering at the far end is the eternal flame of hope. The tomb of the unknown deportee lies at your feet. Above, the inscription reads, “Dedicated to the living memory of the 200,000 French deportees shrouded by the night and the fog, exterminated in the Nazi concentration camps.” The side rooms are filled with triangles—reminiscent of the identification patches inmates were forced to wear—each bearing the name of a concentration camp.

From the side room on the left, stairs lead up to Rooms 1 and 2, where you’ll find a powerful exhibit on life in a concentration camp (vividly described in English). You’ll circle around to where stairs lead back to the room of 200,000 crystals.

Above the exit as you leave is the message you’ll find at many other Holocaust sites: “Forgive, but never forget.”

• Return to ground level. Exit the garden, turn left, and cross the bridge (Pont de l’Archevêché). When you reach the Left Bank, turn right along the river and work your way along the south side of Notre-Dame. We’re now turning our attention to the neighborhood around us, the...

You’re now on the Left Bank.

The Rive Gauche, or the Left Bank of the Seine—“left” if you were floating downstream—is old Paris at its most atmospheric. This side of the river still has many of the twisting lanes and narrow buildings of medieval times. (The Right Bank near the Seine is more modern and business-oriented, with wide boulevards and stressed Parisians in suits.)

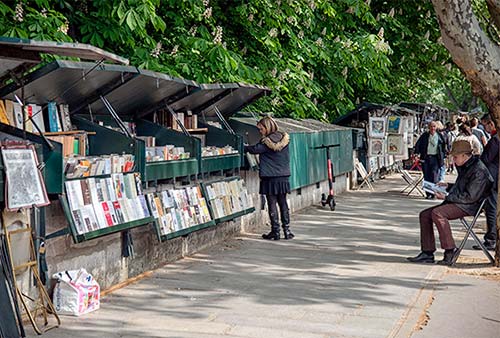

Here along the riverbank, the “big business” is secondhand books, displayed in the green metal stalls on the parapet. These literary entrepreneurs pride themselves on their easygoing style. With flexible hours and virtually no overhead, they run their businesses as they have since medieval times.

These booksellers (or bouquinistes; boo-keen-eest) have been a Parisian fixture since the mid-1500s, when such shops and stalls lined most of the bridges in Paris. In 1557, these merchants ran afoul of the authorities for selling forbidden Protestant pamphlets in then-Catholic Paris. After the Revolution, business boomed when entire libraries were liberated from rich nobles.

Today, the waiting list to become one of Paris’ 250 bouquinistes is eight years. Each bouquiniste is allowed four boxes, and the most-coveted spots are awarded based on seniority. Rent is free, but bouquinistes are required to paint their boxes a standard green and stay open at least four days a week, or they lose their spot. Notice how they guard against the rain by wrapping everything in plastic. And yes, they do leave everything inside when they lock up at night; metal bars and padlocks keep things safe. Though their main items may be vintage books, these days tourists prefer posters and magnets.

• At a gap in the green stalls directly across from Notre-Dame, find stairs leading down to the river—good for losing crowds and for a terrific...

From this side, you can really appreciate both the church architecture and the devastation wrought by the 2019 fire. Before the fire, you’d have seen a green lead-covered roof topped with Viollet-le-Duc’s 300-foot steeple, and several statues adorning its base.

Those are gone completely, as is the lead roof and all windows—save for the three massive rose windows (now covered for protection). But what’s surprising is how much of the church survived. That’s a testament to the medieval architects who designed this amazing structure. Their great technological innovation is what we’ve come to call the Gothic style.

In a glance, you can spot many of the elements of Gothic: pointed arches, the lacy stone tracery of the windows, pinnacles, statues on rooftops, and pointed steeples covered with the prickly “flames” (Flamboyant Gothic) of the Holy Spirit. Most distinctive of all are the flying buttresses. These 50-foot stone “beams” that stick out of the church were the key to the complex Gothic architecture. The pointed arches built inside the church cause the weight of the roof to push outward rather than downward. The “flying” buttresses support the roof by pushing back inward. Gothic architects were masters at playing architectural forces against each other to build loftier and loftier churches, opening the walls for stained-glass windows. The Gothic style was born here in Paris. Those wooden structures you see supporting the flying buttresses show how they were originally raised.

Picture Quasimodo (the fictional hunchback) limping around along the railed balcony at the base of the roof among the “gargoyles.” These grotesque beasts sticking out from pillars and buttresses represent souls caught between heaven and earth. They also function as rainspouts (from the same French root word as “gargle”) when there are no evil spirits to battle.

• Continue walking along the river. When you reach the bridge (Pont au Double) at the front of Notre-Dame, head back up the stairs, veer left across the street, and find a small park called Square Viviani (fill your water bottle from fountain on left). Angle across the square and pass by Paris’ oldest inhabitant—an acacia tree nicknamed Robinier, after the guy who planted it in 1602. Imagine that this same tree might once have shaded the Sun King, Louis XIV. Just beyond the tree you’ll find the small rough-stone church of St. Julien-le-Pauvre. Leave the park, walking past the church, to tiny Rue Galande.

Picture Paris in 1250, when the church of St. Julien-le-Pauvre was still new. You can pop into the church, if it’s open, for a trip east a few hundred miles and back a few centuries. Back outside, continue around the church a few steps. Notre-Dame was nearly built, Sainte-Chapelle had just opened, the university was expanding human knowledge, and Paris was fast becoming a prosperous industrial and commercial center. The area around the church and along Rue Galande gives you some of the medieval feel of ramshackle architecture and old houses leaning every which way. In medieval days, people were piled on top of each other, building at all angles, as they scrambled for this prime real estate near the main commercial artery of the day—the Seine. The smell of fish competed with the smell of neighbors in this knot of humanity.

Narrow dirt (or mud) streets sloped from here down into the mucky Seine until the 19th century, when modern quays and embankments cleaned everything up.

• Return toward the river, walking past the church and park on the cobbled lane. Turn left on Rue de la Bûcherie and drop into the...

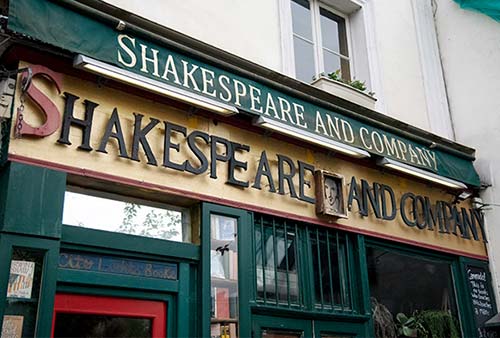

In addition to hosting butchers and fishmongers, the Left Bank has been home to scholars, philosophers, and poets since medieval times. This funky bookstore—a reincarnation of the original shop from the 1920s on Rue de l’Odéon—has picked up the literary torch. Sylvia Beach, an American with a passion for free thinking, opened Shakespeare and Company for the post-WWI Lost Generation, who came to Paris to find themselves. American writers flocked to the city for the cheap rent, fleeing the uptight, Prohibition-era United States. Beach’s bookstore was famous as a meeting place for Paris’ expatriate literary elite. Ernest Hemingway borrowed books from it regularly. James Joyce struggled to find a publisher for his now-classic novel Ulysses—until Sylvia Beach published it. George Bernard Shaw, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound also got their English fix at her shop.

Today, the bookstore carries on that literary tradition—the owner, Sylvia, is named after the original store’s founder. Struggling writers are given free accommodations in tiny rooms with views of Notre-Dame. Explore—the upstairs has a few seats, cots, antique typewriters, and cozy nooks. Downstairs, travelers enjoy a great selection of used English books—including my Paris and France guidebooks. Their cozy coffee shop sits next door.

Notice the green water fountain (1900) in front of the bookstore, one of the many in Paris donated by the English philanthropist Sir Richard Wallace. The hooks below the caryatids once held metal mugs for drinking the water before the age of plastic (the mugs were removed in the 1950s). Wallace donated the fountains after the Franco-Prussian War to give residents free access to water as aqueducts had been destroyed. The four nymphs represent sobriety, simplicity, kindness, and charity.

• Continue to Rue du Petit-Pont and turn left. This bustling north-south boulevard (which becomes Rue St. Jacques) was the Romans’ busiest street 2,000 years ago, with chariots racing in and out of the city. (Roman-iacs can view remains from the third-century baths, and a fine medieval collection, at the nearby Cluny Museum).

A block south of the Seine, turn right at the Gothic church of St. Séverin and walk into the Latin Quarter.

Don’t ask me why, but building this church took a century longer than building Notre-Dame. This is Flamboyant, or “flame-like,” Gothic, and you can see how the short, prickly spires are meant to make this building flicker in the eyes of the faithful. The church gives us a close-up look at gargoyles, the decorative drain spouts that also functioned to keep evil spirits away.

Inside you can see the final stage of Gothic, on the cusp of the Renaissance. It’s also notable for carrying on the medieval tradition of stained-glass windows into more modern times, while keeping the dominant blues, greens, and reds popular in St. Séverin’s heyday. Walk to the apse and admire the lone twisted Flamboyant Gothic column and the fan vaulting. The apse’s windows (by Jean Bazaine, c. 1960) echo the fan-vaulting effect in a modern, abstract way. Each colorful window represents one of the seven sacraments—blue for baptism, yellow for marriage, etc. The impressive organ filling the entrance wall is a reminder that this church is still a popular venue for evening concerts (see gate for information posters, buy tickets at door).

• At #22 Rue St. Séverin, you’ll find the skinniest house in Paris, two windows wide. Rue St. Séverin leads right through the...

Although it may look more like the Greek Quarter today (cheap gyros abound), this area is the Latin Quarter, named for the language you’d have heard on these streets if you walked them in the Middle Ages. The University of Paris (founded 1215), one of the leading educational institutions of medieval Europe, was (and still is) nearby.

A thousand years ago, the “crude” or vernacular local languages were sophisticated enough to communicate basic human needs, but if you wanted to get philosophical, the language of choice was Latin. Medieval Europe’s class of educated elite transcended nations and borders. From Sicily to Sweden, they spoke and corresponded in Latin. Now the most “Latin” thing about this area is the beat you may hear coming from some of the subterranean jazz clubs.

Walking along Rue St. Séverin, you can still see the shadow of the medieval sewer system. The street slopes into a central channel of bricks. In the days before plumbing and toilets, when people still went to the river or neighborhood wells for their water, flushing meant throwing it out the window. At certain times of day, maids on the fourth floor would holler, “Garde de l’eau!” (“Watch out for the water!”) and heave it into the streets, where it would eventually wash down into the Seine.

As you wander, remember that before Napoleon III commissioned Baron Haussmann to modernize the city with grand boulevards (19th century), Paris was just like this—a medieval tangle. The diverse feel of this area is nothing new—it’s been a melting pot and university district for almost 800 years.

• At the fork with Rue de la Harpe, bear slightly right to continue down Rue St. Séverin another block until you come to...

Busy Boulevard St. Michel (or “boul’ Miche”) is famous as the main artery for Paris’ café and arts scene, culminating a block away (to the left) at the intersection with Boulevard St. Germain. Although nowadays you’re more likely to find leggings at 30 percent off, there are still many cafés, boutiques, and bohemian haunts nearby.

The Sorbonne—the University of Paris’ humanities department—is also nearby, if you want to make a detour, though visitors are not allowed to enter. (Turn left on Boulevard St. Michel and walk two blocks south. Gaze at the dome from the Place de la Sorbonne courtyard.) Originally founded as a theological school, the Sorbonne began attracting more students and famous professors—such as St. Thomas Aquinas and Peter Abélard—as its prestige grew. By the time the school expanded to include other subjects, it had a reputation for bold new ideas. Nonconformity is a tradition here, and Paris remains a world center for new intellectual trends.

• Also to the left is the Cluny Museum, which brings the era of Aquinas and Abélard to life ( see the Cluny Museum Tour chapter). But to continue this walk, cross Boulevard St. Michel. Just ahead is...

see the Cluny Museum Tour chapter). But to continue this walk, cross Boulevard St. Michel. Just ahead is...

This tree-filled square is lined with cafés. In Paris, most serious thinking goes on in cafés. For centuries these have been social watering holes, where you can get a warm place to sit and enjoy stimulating conversation for the price of a cup of coffee. Every great French writer—from Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Jean-Paul Sartre and Jacques Derrida—had a favorite haunt.

Paris honors its intellectuals. If you visit the Panthéon (described on here)—several blocks south on Boulevard St. Michel and to the left—you’ll find French writers (Voltaire, Victor Hugo, Emile Zola, and Rousseau), inventors (Louis Braille), and scientists (including Marie and Pierre Curie) buried in a setting usually reserved for warriors and politicians.

• Adjoining this square toward the river is the triangular Place St. Michel, with a Métro stop and a statue of St. Michael killing a devil. Note: If you were to continue west along Rue St. André-des-Arts, you’d find more Left Bank action ( see the Left Bank Walk chapter).

see the Left Bank Walk chapter).

You’re standing at the traditional core of the Left Bank’s artsy, liberal, hippie, bohemian district of poets, philosophers, winos, and baba cools (neo-hippies). Nearby, you’ll find international eateries, far-out bookshops, street singers, pale girls in black berets, jazz clubs, and—these days—tourists. Small cinemas show avant-garde films, almost always in the version originale (v.o.). For colorful wandering and café-sitting, afternoons and evenings are best. In the morning, it feels sleepy. The Latin Quarter stays up late and sleeps in.

In less commercial times, Place St. Michel was a gathering point for the city’s malcontents and misfits. In 1830, 1848, and again in 1871, the citizens took the streets from the government troops, set up barricades Les Miz-style, and fought against royalist oppression. During World War II, the locals rose up against their Nazi oppressors (read the plaques under the dragons at the foot of the St. Michel fountain).

In the spring of 1968, a time of social upheaval all over the world, young students battled riot batons and tear gas by digging up the cobblestones on the street and hurling them at police. They took over the square and declared it an independent state. Factory workers followed their call to arms and went on strike, challenging the de Gaulle government and forcing change. Eventually, the students were pacified, the university was reformed, and the Latin Quarter’s original cobblestones were replaced with pavement, so future scholars could never again use the streets as weapons. Even today, whenever there’s a student demonstration, it starts here.

• From Place St. Michel, look across the river and find the prickly steeple of the Sainte-Chapelle church. Head toward it. Cross the river on Pont St. Michel and continue north along the Boulevard du Palais. On your left, you’ll see the doorway to Sainte-Chapelle.

Security is strict at the Sainte-Chapelle complex because this is more than a tourist attraction: France’s Supreme Court meets to the right of Sainte-Chapelle in the Palais de Justice.

You’ll need a timed-entry ticket to go inside (see details at the beginning of this chapter), and the church entry may be hidden behind a line of ticket buyers. Once past security, you’ll enter the courtyard outside Sainte-Chapelle, where you’ll find information about upcoming church concerts.

• Enter the humble ground floor.

This triumph of Gothic church architecture is a cathedral of glass like no other. It was speedily built between 1242 and 1248 for King Louis IX—the only French king who is now a saint—to house the supposed Crown of Thorns (later moved to Notre-Dame’s treasury and now in safekeeping since the fire). Its architectural harmony is due to the fact that it was completed under the direction of one architect and in only six years—unheard of in Gothic times. Recall that Notre-Dame’s construction took more than 200 years.

Though the inside is beautiful, the exterior is basically functional. The muscular buttresses hold up the stone roof, so the walls are essentially there to display stained glass. The lacy spire is Neo-Gothic—added in the 19th century. Inside, the layout clearly shows an ancien régime approach to worship. The low-ceilinged basement was for staff and other common folks—worshipping under a sky filled with painted fleurs-de-lis, a symbol of the king. Royal Christians worshipped upstairs. The paint job, a 19th-century restoration, helps you imagine how grand this small, painted, jeweled chapel was. (Imagine Notre-Dame painted like this...) Each capital is playfully carved with a different plant’s leaves.

• Climb the spiral staircase to the Chapelle Haute. Leave the rough stone of the earth and step into the light.

Fiat lux. “Let there be light.” From the first page of the Bible, it’s clear: Light is divine. Light shines through stained glass like God’s grace shining down to earth. Gothic architects used their new technology to turn dark stone buildings into lanterns of light. The glory of Gothic shines brighter here than in any other church.

There are 15 separate panels of stained glass (6,500 square feet—two-thirds of it 13th-century original), with more than 1,100 different scenes, mostly from the Bible. These cover the entire Christian history of the world, from the Creation in Genesis (first window on the left, as you face the altar), to the coming of Christ (over the altar), to the end of the world (the round “rose”-shaped window at the rear of the church). Each individual scene is interesting, and the whole effect is overwhelming. Allow yourself a few minutes to bask in the glow of the colored light before tackling the individual window descriptions below.

• Working clockwise from the entrance, look for these notable scenes, using the map in this chapter as a reference. Don’t worry if you have trouble making sense of the windows—you’re not alone. (The souvenir shop downstairs sells a little book with color photos for further tutoring.) The sun lights up different windows at various times of day. Overcast days give the most even light. On bright, sunny days, some sections are glorious, while others look like sheets of lead.

The first window on the left (with scenes from Genesis) is always dark because of a building butted up against it. Let’s pass over that one and turn to the second window on the left.

Life of Moses (second window, dark bottom row of diamond panels): The first panel shows baby Moses in a basket, placed by his sister in the squiggly brown river. Next, he’s found by the pharaoh’s daughter. Then he grows up. And finally, he’s a man, a prince of Egypt on his royal throne.

More Moses (third window, in middle and upper sections): See how many guys with bright yellow horns you can spy. Moses is shown with horns as the result of a medieval mistranslation of the Hebrew word for “rays of light,” or halo.

Jesus’ Passion Scenes (directly over the altar and behind the canopy): These scenes from Jesus’ arrest and Crucifixion were the backdrop for this chapel’s raison d’être—the Crown of Thorns, which was originally displayed on this altar. Stand close to the steps of the altar—about five paces away—and gaze through the canopy where, if you look just above the altar table, you’ll see Jesus, tied to a green column, being whipped. To the immediate right is the key scene in this relic chapel—Jesus (in purple robe) being fitted with the painful Crown of Thorns.

• Continuing clockwise, find the window on the right wall that’s four circular scenes wide.

Campaign of Holofernes: On the bottom row, focus on the second circle from the left. It’s a battle scene (the campaign of Holofernes) showing three soldiers with swords slaughtering three men. Examine the details. The background is blue. The men have different-colored clothes—red, blue, green, mauve, and white. You can actually see the folds in the robes, the hair, and facial features. Look at the victim in the center—his head is splotched with blood. Details like these were created either by scratching on the glass or by baking on paint. It was a painstaking process of finding just the right colors, fitting them together to make a scene...and then multiplying by 1,100.

Helena in Jerusalem (first window on the right wall, at the rear of the nave near where you’ll exit): This window tells the story of how Christ’s Crown of Thorns found its way from Jerusalem to Constantinople to this chapel. Start in the lower-left corner, where the Roman emperor Constantine (in blue, on his throne) waves goodbye to his Christian mom, Helena. She arrives at the gate of Jerusalem (next panel to the right). The other panels (though almost impossible for 21st-century eyes to follow) tell the rest of the story: Helena discovers the Crown of Thorns and brings it back to Constantinople. Nine hundred years later, French Crusader knights invade the Holy Land and visit Constantinople. Finally, King Louis IX returns to France with the sacred relic, and builds this church to house it.

Rose Window (above entrance): This window (added 200 years later) is the chapel’s climax, showing the final scene in human history. It’s Judgment Day, with a tiny Christ in the center, presiding over a glorious moment of wonders and miracles.

The altar was raised up high to better display the Crown of Thorns, the relic around which this chapel was built. Notice the staircase: Access was limited to the priest and the king, who wore the keys to the shrine around his neck. Also note that there is no high-profile image of Jesus anywhere—this chapel was all about the Crown.

King Louis IX, convinced he’d found the real McCoy, spent roughly the equivalent of €500 million for the Crown, €370 million for the gem-studded shrine to display it in (later destroyed in the French Revolution), and a mere €150 million to build Sainte-Chapelle to house it.

Lay your phone or camera on the ground and shoot the ceiling. Those pure and simple ribs growing out of the slender columns are the essence of Gothic structure.

• Exit Sainte-Chapelle. Back outside, as you walk around the church exterior, look down to see the foundation and take note of how much Paris has risen in the 750 years since Sainte-Chapelle was built. As you head toward the exit of the complex, you’ll pass by the...

Sainte-Chapelle sits within a huge complex of buildings that has housed the local government since ancient Roman times. It was the site of the original Gothic palace of the early kings of France. The only surviving medieval parts are Sainte-Chapelle and the Conciergerie prison.

Most of the site is now covered by the giant Palais de Justice, built in 1776, home of the French Supreme Court. The motto Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité over the doors is a reminder that this was also the headquarters of the Revolutionary government. Here they doled out justice, condemning many to imprisonment in the Conciergerie downstairs—or to the guillotine.

• Now pass through the big iron gate to the noisy Boulevard du Palais. Cross the street to the wide, pedestrian-only Rue de Lutèce and walk about halfway down.

Of the 141 original early-20th-century subway entrances, this is one of only a few survivors—now preserved as a national art treasure. (New York’s Museum of Modern Art even exhibits one.) It marks Paris at its peak in 1900—on the cutting edge of Modernism, but with an eye for beauty. The curvy, plantlike ironwork is a textbook example of Art Nouveau, the style that rebelled against the erector-set squareness of the Industrial Age. Other similar Métro stations in Paris are Abbesses and Porte Dauphine.

The flower and plant market on Place Louis Lépine is a pleasant detour. On Sundays this square flutters with a busy bird market. And across the way is the Préfecture de Police, where Inspector Clouseau of Pink Panther fame used to work, and where the local Resistance fighters took the first building from the Nazis in August 1944, leading to the Allied liberation of Paris a week later.

• Pause here to admire the view. Sainte-Chapelle is a pearl in an ugly architectural oyster. Double back to the Palais de Justice, turn right onto Boulevard du Palais, and enter the Conciergerie.

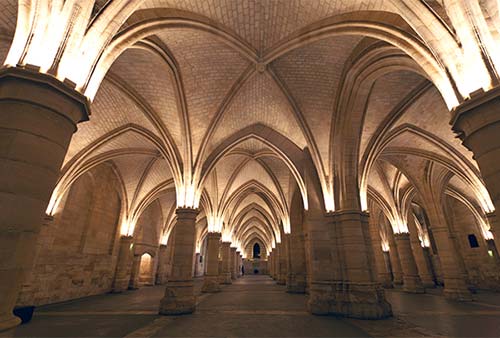

Though barren inside, this former prison echoes with history. The Conciergerie was the last stop for 2,780 victims of the guillotine, including France’s last ancien régime queen, Marie-Antoinette. Before then, kings had used the building to torture and execute failed assassins. (One of its towers along the river was called “The Babbler,” named for the pain-induced sounds that leaked from it.) When the Revolution (1789) toppled the king, the progressive Revolutionaries proudly unveiled a modern and more humane way to execute people—the guillotine. The Conciergerie was the epicenter of the Reign of Terror—the year-long period of the Revolution (1793-94) during which Revolutionary fervor spiraled out of control and thousands were killed. It was here at the Conciergerie that “enemies of the Revolution” were imprisoned, tried, sentenced, and marched off to Place de la Concorde for decapitation.

Pick up a free brochure (with a map) and breeze through the one-way, well-described circuit. You’ll start in the spacious, low-ceilinged Hall of Men-at-Arms (Room 1), originally a guards’ dining room warmed by four big fireplaces (look up the chimneys). During the Reign of Terror, this large hall served as a holding tank for the poorest prisoners. Then they were taken upstairs (in an area closed to visitors), where the Revolutionary tribunals grilled scared prisoners on their political correctness.

Continue to the raised area at the far end of the room (Room 4, today’s bookstore). This was the walkway of the executioner, who was known affectionately as “Monsieur de Paris.” Just past the bookstore, pause in rooms (to the right) with displays on Revolutionary history. Continuing on, you’ll pass the cell (on the left) where shackled suspects were processed by the Office of the Keeper (or “Concierge”), who admitted prisoners, monitored torture...and recommended nearby restaurants. The next cell is where condemned prisoners combed their hair or touched up their lipstick before their final public appearance—waiting for the open-air cart (tumbrel) to pull up outside. The tumbrel would carry them to the guillotine, which was on Place de la Concorde.

Upstairs is a memorial room with the names of the 2,780 citizens condemned to death by the guillotine (names inscribed within thicker outlines indicate a person of higher social rank). Find Marie-Antoinette on the vaulted wall on the right, 10 rows down, in the middle (look for Capet Marie-Antoinette). Head down the hallway past more cells that give a sense of the poor and cramped conditions. Then come several panels about the justice system during the Revolution era.

Next, go downstairs, where—tucked behind heavy black curtains—is a tiny chapel built on the site where Marie-Antoinette’s prison cell originally stood. The chapel’s three paintings tell her sad story: First, Marie (dressed in widow’s black) stoically says goodbye to her grieving family as she’s led off to prison. Next, still stoic, she awaits her fate. Finally, she piously kneels in her cell to receive the Last Sacrament on the night before her beheading. The chapel’s walls drip with silver-embroidered tears. It was made in Marie’s honor by Louis XVIII, the brother of beheaded Louis XVI and the first king to reclaim the throne after the Revolution.

The tour concludes outside in the “Cour de Femmes” courtyard, where female prisoners were allowed a little fresh air. Look up and notice the spikes still guarding from above...and be glad you can leave this place with your head intact. It wasn’t so easy for enemies of the state. On October 16, 1793, Marie-Antoinette was awakened at 4:00 in the morning and led away. She walked the corridor, stepped onto the cart, and was slowly carried to Place de la Concorde, where she had her date with “Monsieur de Paris.”

• Back outside, turn left on Boulevard du Palais. On the corner is the city’s oldest public clock. The mechanism of the present clock is from 1334, and although the case is Baroque, it keeps on ticking.

Turn left onto Quai de l’Horloge and walk along the river, past the “Babbler” tower. The bridge up ahead is Pont Neuf, where we’ll end this walk. At the first corner, veer left into a sleepy triangular square called...

It’s amazing to find such coziness in the heart of Paris. This city of more than two million is still a city of neighborhoods, a collection of villages. The French Supreme Court building looms behind like a giant marble gavel. Enjoy the village-Paris feeling in the park (young Parisians flock to the square on weekend afternoons for pétanque and more). For eating recommendations on this square, see the “Eateries Along This Walk” sidebar, earlier.

• Continue through Place Dauphine. As you pop out the other end, you’re face-to-face with a...

Henry IV (1553-1610) is not as famous as his grandson, Louis XIV, but Henry helped make Paris what it is today—a European capital of elegant buildings and quiet squares. He built the Place Dauphine (behind you), the Pont Neuf (to the right), residences (to the left, down Rue Dauphine), the Louvre’s long Grand Gallery (downriver on the right), and the tree-filled Square du Vert-Galant (directly behind the statue, on the tip of the island). The square is one of Paris’ make-out spots; its name comes from Henry’s nickname, the Green Knight, as Henry was a notorious ladies’ man. The park is a great place to relax, dangling your legs over the concrete prow of this boat-shaped island.

• From the statue, turn right onto the old bridge. Pause at the little nook halfway across.

This “new bridge” is now Paris’ oldest. Built during Henry IV’s reign (about 1600), its arches span the widest part of the river. Unlike other bridges, this one never had houses or buildings growing on it. The turrets were originally for vendors and street entertainers. In the days of Henry IV, who promised his peasants “a chicken in every pot every Sunday,” this would have been a lively scene. From the bridge, look downstream (west) to see the next bridge, the pedestrian-only Pont des Arts. Ahead on the Right Bank is the long Louvre Museum. Beyond that, on the Left Bank, is the Orsay. And what’s that tall tower in the distance?

Our walk ends where Paris began—on the Seine River. From Dijon to the English Channel, the Seine meanders 500 miles, cutting through the center of Paris. The river is shallow and slow within the city, but still dangerous enough to require steep stone embankments (built 1910) to prevent occasional floods.

In summer, the riverside quais are turned into beach zones with beach chairs and tanned locals, creating the Paris Plages (see here). The success of the Paris Plages helped motivate the city to take the next step: to permanently banish cars from long stretches of the riverside (between the Orsay and Pont de l’Alma on the Left Bank and between the Louvre and Place de la Bastille on the Right Bank), turning them into parks instead.

The Seine is still the main artery of Paris. Besides tourist boats, it also carries commercial barges with 20 percent of Paris’ transported goods. And on the banks, sportsmen today cast into the waters once fished by Paris’ original Celtic inhabitants 2,000 years ago.

• We’re done. You can take a boat tour that leaves from near the base of Pont Neuf on the island side (Vedettes du Pont Neuf; see here). Or you could take our Left Bank Walk, which begins one bridge downriver.

The nearest Métro stop is Pont Neuf, across the bridge on the Right Bank. Bus #69 heads east along the Right Bank’s Quai du Louvre (at the north end of the bridge) and west along Rue de Rivoli (a block farther north). Below the bridge is the riverside promenade—filled with people, for good reason, on a sunny day. In fact, from here you can go anywhere—you’re standing in the heart of Paris.