Musée Marmottan Monet

MARMOTTAN’S FURNISHINGS, MORISOT, AND MORE

PAINTINGS OF GIVERNY (1883-1926)

NYMPHEAS AND LARGE-SCALE CANVASES

The Marmottan has the best collection of works by the master Impressionist Claude Monet. In this mansion on the western fringe of urban Paris, you can walk through Monet’s life, from black-and-white sketches to colorful open-air paintings to the canvas that gave Impressionism its name. The museum’s highlights are scenes of his garden at Giverny, including larger-than-life water lilies. The Marmottan also features a world-class collection of works by female Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot and intriguing temporary exhibitions.

Paul Marmottan (1856-1932) lived here amid his collection of exquisite 19th-century furniture and paintings. He donated his home and possessions to a private trust (which is why your Museum Pass isn’t valid here). After Marmottan’s death, the more daring art of Monet and others was added. The combination of the mansion, the furnishings, the Impressionist and Empire paintings, and the many Monet masterpieces makes the Marmottan an aesthetic pleasure.

Cost: €14.50, not covered by Museum Pass; €25 combo-ticket with Monet’s garden and house at Giverny (see here; lets you skip the line at Giverny).

Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, Thu until 21:00, closed Mon.

Information: +33 1 44 96 50 33, www.marmottan.fr.

Avoiding Lines: Advance tickets can be purchased at FNAC stores or on the Marmottan’s website for special exhibits, which are frequent. Without a reservation, arrive close to opening time or late in the day to minimize crowds (Thursday late is best).

Getting There: It’s in Paris’ west end at 2 Rue Louis-Boilly.

By Métro: Take Métro line 9 to La Muette. Exit via sortie 1. It’s a six-block, 10-minute walk: Cross Chaussée de la Muette street, turn left, and walk toward a major intersection (you’ll pass by a brick building called La Gare—formerly a train station). Follow Chaussée de la Muette to a second, three-way intersection, where you’ll continue straight onto a tree-lined pedestrian lane, Avenue du Ranelagh. Walk through the peaceful park to the museum at the far end.

By RER Train (handy from Rue Cler): Catch RER/Train-C from Austerlitz, St-Michel, Orsay, Invalides, or Pont de l’Alma (board any train called NORA or GOTA), get off at the Boulainvilliers stop, and follow signs to sortie Boulainvilliers. Turn right up Rue Boulainvilliers, then turn left down Chaussée de la Muette and follow the directions above to reach the museum. When returning on RER/Train-C, take the Sud direction and make sure your stop is listed on the monitor: You don’t want to end up in Versailles.

By Bus: Handy east-west bus #63 gets you kinda close but requires a walk of about 600 yards. Get off at the Octave Feuillet stop on Avenue Henri Martin, cross Avenue Henri Martin, and follow the tree-lined street to the right that curves around to the museum.

Tours: The €4 audioguide, while overkill for some, supplements my tour well and includes coverage of temporary exhibits. Small information displays are in many rooms.

Length of This Tour: Allow one hour.

Services: There are two WCs. One is on the second floor (usually with lines), and one is downstairs by the Monet collection (bigger and quieter).

Security: Water bottles must be left at the entry. Don’t forget to retrieve yours as you leave.

Cuisine Art: Cafés, boulangeries, and bistros are 10 minutes away around the La Muette Métro stop (Rue Mozart has good choices).

Nearby: The kid-friendly park in front of the museum is terrific for families with small kids. Parents can take turns visting the museum.

Make the most of the long trip here by combining a visit to the Marmottan with Trocadéro-area sights, a short Métro or bus ride away (see here).

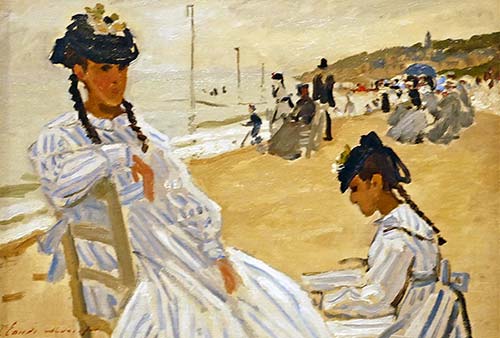

Starring: Claude Monet, including Impression: Sunrise (shown on here); paintings of cathedrals, train stations, and beaches; scenes from Giverny; and water lilies.

The 19th-century Marmottan mansion, formerly a hunting lodge, has three pleasant, manageable floors, all worth perusing. The ground floor has several rooms of Paul Marmottan’s period furnishings and notable paintings by French artists. Temporary exhibits are usually displayed in a gallery on this floor. Upstairs is a permanent collection, featuring illuminated manuscripts and some works by Monet’s fellow Impressionists—Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Paul Gauguin, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edouard Manet, and especially Berthe Morisot. Monet’s works—the core of the collection—are in the basement, which you’ll tour last.

Because the museum rotates its large collection of paintings, this chapter is not designed as a room-by-room tour. Use it as a general background on Monet’s life and some of the paintings you’re likely to encounter. Read it once before you go, then let the museum surprise you.

• Enter the museum on the ground floor. Before visiting the Monet collection in the basement, explore the first two floors, filled with...

Upon entering, you’ll be directed first through a dining room usually displaying a selection of paintings by Monet and his colleagues. Next you’ll see Marmottan’s furnishings, which tended toward the Empire style: highly polished mahogany with upholstery featuring brass highlights and classical motifs like laurel wreaths and torches. Chairs have arched backs, armrests, and tapered legs.

The paintings are also from this period, when the French bourgeoisie reigned supreme. There’s an embroidered portrait of Napoleon, plus portraits of ladies wearing tiaras and gentlemen in high-collared suits painted in the seamless-brushstroke style that Monet rebelled against.

• Head upstairs.

On this floor, look for Napoleon’s bed and a portrait of him at 30, having just been appointed consul. You’ll see works that look famous—statues by Canova and scenes of Venice by Canaletto—but most are by these famous artists’ students. A darkened room displays the Marmottan’s excellent medieval collection: illuminated manuscripts (colorfully illustrated books), musical scores, stained glass, and miniature paintings of saints and Bible scenes.

A highlight is a hall featuring the work of Berthe Morisot, one of the first female Impressionists (see the sidebar), and an ever-changing display of works by Monet’s fellow Impressionists and friends—Degas, Pissarro, Gauguin, Renoir.

• Drop back downstairs and pass through the temporary exhibition gallery (usually worth a good look) to reach the basement level. This is where you’ll find the...

Descending the stairs, you’re immediately plunged into the colorful and messy world of Claude Monet. A timeline of his life and accomplishments is posted immediately to the left.

The collection displays some 50 paintings by Monet spanning his lifetime (1840-1926). They’re generally (and very roughly) arranged in chronological order—from Monet’s youthful discovery of Impressionism, to his mature “series” paintings, to his last great water lilies from Giverny.

Claude Monet was the leading light of the Impressionist movement that revolutionized painting in the 1870s. Fiercely independent and dedicated to his craft, Monet gave courage to Renoir and other like-minded artists, who were facing harsh criticism.

Let’s survey Monet’s long life:

Born in Paris in 1840, Monet grew up in seaside Le Havre as the son of a grocer and began his art career sketching caricatures of townspeople. He realized he had a gift for quickly capturing an overall impression with a few simple strokes. Monet defied his family, insisted he was an artist, and sketched the world around him—beaches, boats, and small-town life. Fellow artist Eugène Boudin encouraged Monet to don a scarf, set up his easel outdoors, and paint the scene exactly as he saw it. Today, we say, “Well, duh!” But “open-air” painting was unorthodox for artists of the day, who were trained to study their subjects thoroughly in the perfect lighting of a controlled studio setting.

At 19, Monet went to Paris but refused to enroll in the official art schools. His letters to friends make it clear he was broke and paying the price for his bohemian lifestyle.

In 1867—the same year the Salon rejected his work—he and his partner Camille had their first child, Jean. They moved to the countryside of Argenteuil, where he developed his open-air, Impressionist style. Impression: Sunrise was his landmark work at the breakthrough 1874 Impressionist Exhibition. He went on to paint several series of scenes, such as Gare Saint-Lazare, at different times of day. His career was gaining steam.

After the birth of their second son, Michel, Camille’s health declined, and she later died. Monet traveled a lot, painting landscapes (Bordighera), people (Portrait de Poly), and more series, including the famous Cathedral of Rouen. In 1890, he settled down at his farmhouse in Giverny and later married Alice Hoschedé. He traveled less but visited London to paint the Halls of Parliament. Mostly, he painted his own water lilies and flowers in an increasingly messy style. He died in 1926 a famous man.

While living at Argenteuil, Monet and Camille played host to Renoir, Edouard Manet, Alfred Sisley, and other painters. Monet led them on open-air painting safaris to the countryside. Inspired by the realism of Manet, they painted everyday things—landscapes, seascapes, street scenes, ladies with parasols, family picnics—in bright, basic colors.

They began perfecting the distinct Impressionist style—painting nature as a mosaic of short brushstrokes of different colors placed side by side, suggesting shimmering light.

First, Monet simplified. A lady’s dress might be composed of just a few thick strokes of paint (as in his early work The Beach at Trouville, 1870-1871). Monet gradually broke things down into even smaller “pixels”—small dots of different shades. If you back up from a Monet canvas, the pigments blend into one (for example, red plus green plus yellow equals a brown boat). Still, they never fully resolve, creating the effect of shimmering light. Monet limited his palette to a few bright basics; cobalt blue, white, yellow, two shades of red, and emerald green abound. But no black—even shadows are a combination of bright colors.

Monet’s constant quest was to faithfully reproduce nature in blobs of paint. His eye was a camera lens set at a very slow shutter speed to admit maximum light. Then he “developed” the impression made on his retina with an oil-based solution.

In search of new light and new scenes, Monet traveled throughout France and Europe, painting landscapes in all kinds of weather. Picture Monet at work, hiking to a remote spot—carrying an easel, several canvases, brushes (large-size), a palette, tubes of paint (an invention that made open-air painting practical), food and drink, a folding chair, and an umbrella (and this was before the invention of backpacks)—and wearing his trademark hat, with a cigarette on his lip. He weathered the elements, occasionally putting himself in danger by clambering on cliffs to get the scenes he wanted.

The key was to work fast, before the weather changed and the light shifted, completely changing the colors. Monet worked “wet-in-wet,” applying new paint before the first layer dried, mixing colors on the canvas, and piling them up into a thick paste.

• Monet’s most famous “impression” was the one that gave the movement its name.

This is the painting that started the revolution—a simple, serene view of boats bobbing under an orange sun. At the first public showing by Monet, Renoir, Degas, and others in Paris in 1874, critics howled at this work and ridiculed the title. “Wallpaper,” one called it. The sloppy brushstrokes and ordinary subject looked like a study, not a finished work. The style was dubbed “Impressionist”—an accurate name.

The misty harbor scene obviously made an “impression” on Monet, who faithfully rendered the fleeting moment in quick strokes of paint. The waves are simple horizontal brushstrokes. The sun’s reflection on the water is a few thick, bold strokes of orange tipped with white. They zigzag down the canvas the way a reflection shifts on moving water.

Monet’s claim to fame became a series of paintings of a single scene, captured at different times of day under different light. He first explored the idea with one of Paris’ train stations, Gare St. Lazare, in the 1870s. Soon, he conceived paintings to be shown as a group, giving a time-lapse view of a single subject.

In Rouen, he rented several rooms offering different angles overlooking the Rouen Cathedral. He worked on up to 14 different canvases at a time, shuffling the right one onto the easel as the sun moved across the sky. The cathedral is made of brown stone, but at sunset it becomes gold and pink with blue shadows, softened by thick smudges of paint. The true subject is not the cathedral but the full spectrum of light that bounces off it.

He did another series in London. Turning his hotel room into a studio, Monet—working on nearly a hundred canvases simultaneously—painted the changing light on the River Thames. He caught the reflection of the Houses of Parliament on the river’s surface, stretching and bending with the current. London’s famous fog epitomized Monet’s favorite subject—the atmosphere that distorts distant objects. That filtering haze gives even different-colored objects a similar tone, resulting in a more harmonious picture. When the light was just right and the atmosphere glowed, the moment of “instantaneity” had arrived, and Monet worked like a madman.

Monet started many of his canvases in the open air and then painstakingly perfected them later in the studio. He composed his scenes with great care—clear horizon lines give a strong horizontal axis, while diagonal lines (of trees or shorelines) create solid triangles.

These series—of London, the cathedral, haystacks, poplars, and mornings on the Seine—were very popular. Monet, poverty-stricken until his mid-40s, was slowly becoming famous, first in America, then in London, and finally in France. He soon took up residence in what would be his home for the rest of his life: Giverny.

In 1883, Monet’s brood settled into a farmhouse in Giverny (50 miles west of Paris). Financially stable and domestically blissful, he turned Giverny into a garden paradise and painted nature without the long commute.

In 1890, Monet started work on his Japanese garden, inspired by tranquil scenes from the Japanese prints he collected. He diverted a river to form a pond, planted willows and bamboo on the shores, filled the pond with water lilies, then crossed it with this wooden footbridge. As years passed, the bridge became overgrown with wisteria. Compare several versions. He painted the bridge at different times of day and year, exploring different color schemes.

Monet uses the bridge as the symmetrical center of simple, pleasing designs. The water is drawn with horizontal brushstrokes that get shorter as you move up the canvas (farther away), creating the illusion of distance. The horizontal water contrasts with the vertical willows, while the bridge “bridges” the sides of the square canvas and laces the scene together.

In 1912, Monet began to go blind. Cataracts distorted his perception of depth and color and sent him into a tailspin of despair. The (angry?) red paintings date from this period.

As his vision slowly failed, Monet concentrated on painting close-ups of the surface of the pond and its water lilies—red, white, yellow, and lavender. Some lilies are just a few broad strokes on a bare canvas (a study); others are piles of paint formed with overlapping colors.

But more than the lilies, the paintings focus on the changing reflections on the surface of the pond. Pan slowly around the room and watch the pond go from predawn to bright sunlight to twilight.

Early lily paintings show the shoreline as a reference point. But increasingly, Monet crops the scene ever closer, until there is no shoreline, no horizon, no sense of what’s up or down. Stepping back from the canvas, you see the lilies just hang there on the museum wall, suspended in space. The surface of the pond and the surface of the canvas are one. Modern abstract art—a colored design on a flat surface—is just around the corner.

• The climax of the visit is a round room (with benches), where you can immerse yourself in the...

In the midst of the chaos of World War I, Monet began a series of large-scale paintings of water lilies. They were installed at the Orangerie Museum. Here at the Marmottan are smaller-scale studies for that series. But the sheer size of these studies is impressive.

Get close—Monet did—and analyze how he composed these works. Some lilies are patches of thick paint circled by a squiggly “caricature” of a lily pad. Monet simplifies in a way that Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso would envy. You can see that the simple smudge of paint that composes the flower is actually a complex mix of different colors. But to get these colors to fully resolve in your eye, you’d have to back up all the way to Giverny.

When Monet died in 1926, he was a celebrity. Starting with meticulous line drawings, he had evolved into an open-air realist, then Impressionist color analyst, then serial painter, and finally master of reflections. In the latter half of his life, Monet’s world shrank—from the broad vistas of the world traveler to the tranquility of his home, family, and garden. But his artistic vision expanded as he painted smaller details on bigger canvases and helped invent modern abstract art.

• You’ve reached the end of the tour. From the museum, retrace your steps to La Muette Métro/Boulainvilliers RER station, where you’ll also find a taxi stand. Across from the museum, bus #32 takes you to stops at Trocadéro and along the Champs-Elysées near the Grand Palais.

Or, if you’re up for a postmuseum stroll, it’s a pleasant one-hour walk from here to the Eiffel Tower along Rue de Passy, one of Paris’ most pleasant (and upscale) shopping streets. To reach Rue de Passy, head east up Chaussée de la Muette, past the La Muette Métro stop—follow that tower. After Rue de Passy ends, you could continue straight—on Boulevard Delessert—all the way to the Eiffel Tower.