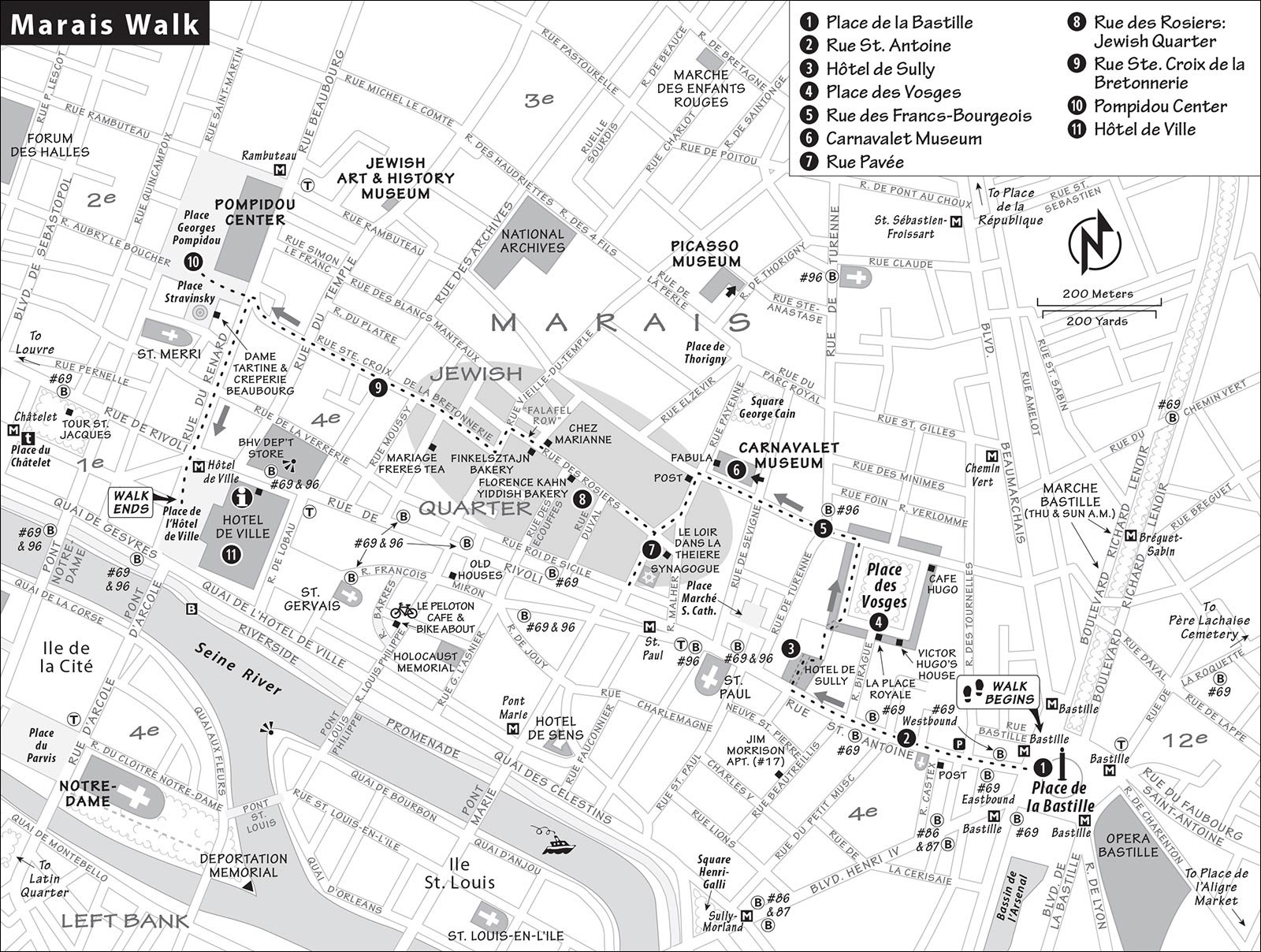

From Place Bastille to the Pompidou Center

8 Rue des Rosiers: Jewish Quarter

9 Rue Ste. Croix de la Bretonnerie

This walk introduces you to one of Paris’ most intriguing quarters, the Marais. Naturally, when in Paris you want to see the big sights—but to experience the city, you also need to visit a vital neighborhood. The Marais fits the bill, with trendy boutiques and art galleries, with-it cafés, narrow streets, leafy squares, Jewish bakeries, aristocratic mansions, and fun nightlife—and it’s filled with real Parisians. It’s the perfect setting to appreciate the flair of this great city.

The walk mixes history with glimpses of daily life in the Marais. Follow this suggested route for a start, then explore. If at any point you want to wander into a store or savor a café crème, by all means, you have permission to press pause.

Length of This Walk: Allow about 2 hours for this level, two-mile walk. Add an additional hour for each museum you decide to visit along the way.

When to Go: The Marais is liveliest on Sundays when many streets are off limits to cars (and shops are open, unlike in other neighborhoods). Monday mornings are sleepy. On Saturdays, Jewish businesses may close, but the area still hops.

Victor Hugo’s House: Free, fee for optional special exhibits, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, 6 Place des Vosges.

Carnavalet Museum: Free, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, 16 Rue des Francs Bourgeois.

Jewish Art and History Museum: €10, covered by Museum Pass, free on first Sat of month Oct-June; Tue-Fri 11:00-18:00, Sat-Sun from 10:00, open later during special exhibits—Wed until 21:00 and Sat-Sun until 19:00, closed Mon year-round, last entry 45 minutes before closing; 71 Rue du Temple.

Holocaust Memorial: Free, Sun-Fri 10:00-18:00, Thu until 22:00, closed Sat and certain Jewish holidays, 17 Rue Geoffroy l’Asnier.

Pompidou Center: €15, covered by Museum Pass, free escalator access to sixth-floor views, free on first Sun of month—requires timed-entry reservation; permanent collection open Wed-Mon 11:00-21:00, closed Tue. The center is scheduled to close in late 2025 for a multiyear renovation.

Tours: Paris Walks offers excellent guided tours of this area (see here).

Starring: The grand Place des Vosges, the Jewish Quarter, several museums, and the boutiques and trendy lifestyle of today’s Marais.

• Start at the west end of Place de la Bastille. Bus #69 stops on Rue St. Antoine, a half-block to the west. From the Bastille Métro, exit following signs to Place de la Bastille/Place des Vosges. Ascend onto a vast, noisy traffic circle dominated by the bronze Colonne de Juillet (July Column). The figure atop the column is, like you, headed west. Lean against the Métro railing in front of the Banque de France.

The famous Bastille fortress once stood on this square. All that remains today is a faint cobblestone outline of the fortress’ round turrets traced in the pavement on Rue St. Antoine (30 yards before it hits the square). Though virtually nothing remains, it was on this spot that history turned.

It’s July 1789, and the spirit of revolution is stirring in the streets of Paris. The king’s troops have evacuated the city center, withdrawing to their sole stronghold, a castle-like structure guarding the east edge of the city—the Bastille. The Bastille was also a prison (which even held the infamous Marquis de Sade in 1789) and was seen as the very symbol of royal oppression. On July 14, the people of Paris gathered here at the Bastille’s main gate and demanded the troops surrender. When negotiations failed, they stormed the prison and released its seven prisoners. For good measure, they decorated their pikes with the heads of a few bigwigs. This triumph of citizens over royalty ignited all of France and inspired the Revolution. Over the next few months, the Parisians demolished the stone prison brick by brick.

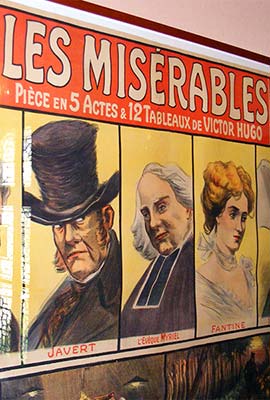

Though the fortress is long gone, Place de la Bastille has remained a sacred spot for freedom lovers ever since. The July Column—with its gilded statue of Liberty elegantly carrying the torch of freedom into the future—is a symbol of France’s long struggle to establish democracy. It was built to commemorate the revolution of 1830, when the conservative King Charles X—who forgot all about the Revolution of the previous generation—needed to be tossed out. The mid-19th century was a time of social unrest throughout Europe; the square drew worker rallies, and at times, the streets of Paris were barricaded by the working class, as dramatized in Les Misérables.

Today the square remains a popular spot for demonstrations, and the Bastille is remembered every July 14 on France’s independence day—Bastille Day (see sidebar).

Across the square, the southeast corner is dominated (some say overwhelmed) by the flashy, curved, glassy gray facade of the Opéra Bastille. In a symbolic attempt to bring high culture to the masses, former French president François Mitterrand chose this location for the building that would become Paris’ main opera venue, edging out the city’s earlier “palace of the rich,” the Garnier-designed opera house. Designed by Uruguayan-Canadian architect Carlos Ott, the grand Opéra Bastille—one of the largest theaters in the world, with nine stages—was opened with fanfare by Mitterrand on the 200th Bastille Day, July 14, 1989. Tickets are subsidized to encourage the unwashed masses to attend, though how much high culture they have actually enjoyed here is a subject of debate. (For opera ticket info, see here.)

• Now turn your back on Place de la Bastille and head west down Rue St. Antoine about four blocks into the Marais.

From Paris’ earliest days, this has been one of its grandest boulevards, part of the east-west axis from Place de la Concorde to the eastern gate, Porte St. Antoine. The street was broadened in the mid-1800s as part of the civic renovation plan by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (see sidebar on here). Today, it’s an ordinary street with a typical mix of workaday shops: banks, clothing stores, produce stands, restaurants.

Just past the first block, a statue of Beaumarchais (1732-1799) introduces you to the aristocratic-but-bohemian spirit of the Marais. Beaumarchais, who lived near here, made watches for Louis XV, wrote the bawdy Marriage of Figaro (which Mozart turned into an opera), and smuggled guns to freedom fighters in both the American and French Revolutions.

On the next block, across the street to the left, is a stately pre-Revolutionary mansion with a fine red carriage gate. It became a school after the Revolution. Look ahead, along the roofline of this street of 19th-century facades with stout walls holding ranks of chimneys—one chimney for each fireplace, because back then any room that had heat had its own hearth.

Continuing on, at the intersection with Rue de Birague, music fans may wish to make a 100-yard detour to the left, down Rue Beautreillis to #17, the nondescript apartment where rock star Jim Morrison died. (For more on Morrison in Paris, see here.)

If you cross over here or elsewhere along Rue St. Antoine, pay attention to the busy two-way bike “freeway” on the south side of the street. Paris’ pro-bike and pro-pedestrian mayor, Anne Hidalgo, has replaced many car lanes with bike lanes like these. The bike lanes often seem busier than the parallel car lanes.

• Continue down Rue St. Antoine to #62 and enter the grand courtyard of Hôtel de Sully (daily 10:00-19:00). If the building is closed, you’ll need to backtrack one block to Rue de Birague to reach the next stop, Place des Vosges.

During the reign of Henry IV (r. 1589-1610), this area—originally a swamp (marais)—became the hometown of the French aristocracy. Big shots built their private mansions (hôtels), like this one, close to Henry’s stylish Place des Vosges. Hôtels that survived the Revolution now house museums, libraries, and national institutions.

Nobles entered the courtyard by horse-drawn carriage, then parked under the four arches to the right. The elegant courtyard separated the mansion from the noisy and very public street. Look up at statues of Autumn (carrying grapes from the harvest), Winter (a feeble old man), and the four elements.

Enter the building between the sphinxes into a passageway and admire the sumptuous ceiling in the bookstore. Continue into the back courtyard, where noisy Paris takes a back seat. Enjoy the oak tree, manicured hedges, vine-covered walls, birdsong, and the back side of the mansion with its warm stone and statues. Use the bit of Gothic window tracery (on the right) for a fun framed photo of your travel partner as a haloed Madonna. At the far end, the French doors are part of a former orangerie, or greenhouse, for homegrown fruits and vegetables throughout winter; these days it warms office workers. Ostentatious as mansions like this might seem, they were often the second residences of fabulously wealthy nobles. Owners of such mansions were members of pre-Revolutionary France’s one percent, who had primary residences that were much grander châteaux in the countryside.

• Continue through the small door at the far-right corner of the back courtyard, and pop out into one of Paris’ finest squares.

Walk to the center, where Louis XIII, on horseback, gestures, “Look at this wonderful square my dad built.” He’s surrounded by locals enjoying their community park. You’ll see children frolicking in the sandbox, lovers warming benches, and pigeons guarding their fountains while trees shade this escape from the glare of the big city (you can refill your water bottle in the center of the square, behind Louis).

Study the architecture: nine pavilions (houses) per side. The two highest—at the front and back—were for the king and queen (but were never used). Warm red brickwork—some real, some fake—is topped with sloped slate roofs, chimneys, and another quaint relic of a bygone era: TV antennas. Beneath the arcades are cafés, art galleries, and restaurants—it’s an atmospheric place for lunch or dinner (for recommendations, see the Marais section of the Eating chapter).

Henry IV built this centerpiece of the Marais in 1605 and called it “Place Royale.” As he’d hoped, it turned the Marais into Paris’ most exclusive neighborhood. Just like Versailles 80 years later, this was a magnet for the rich and powerful of France. The square served as a model for civic planners across Europe. With the Revolution, the aristocratic splendor of this quarter passed. To encourage the country to pay its taxes, Napoleon promised naming rights to the district that paid first—the Vosges region (near Germany).

The insightful writer Victor Hugo lived at #6 from 1832 to 1848. (It’s at the southeast corner of the square, marked by the French flag.) This was when he wrote much of his most important work, including his biggest hit, Les Misérables. Inside this free museum you can wander through eight plush rooms, take in a fine view of the square, and enjoy a charming garden café and good WCs (see “Victor Hugo’s House” on here).

Sample the flashy art galleries ringing the square (the best ones are behind Louis). Ponder a daring new piece for that blank wall at home and take a peek into the courtyard of the Hôtel le Pavillon de la Reine (#28) for a glimpse into refined living—my hotel doesn’t look like this. Or consider a pleasant break at one of the recommended eateries on the square.

• Exit the square at the northwest (far left) corner. Head west on...

From the Marais of yesteryear, immediately enter the lively neighborhood of today. Stroll down a block full of cafés and eclectic clothing boutiques with the latest fashions. A few doorways (including #8 and #13) lead into courtyards with more shops. Even this “main” street through the neighborhood is narrow and more fit for pedestrians than cars.

In the 19th century, the aristocrats moved elsewhere. The Marais became a working-class quarter, filled with gritty shops, artisans, immigrants, and a Jewish community. Haussmann’s modernization plan put the Marais in line for the wrecking ball. But then the march of “progress” was halted by one tiny little event—World War I—and the Marais was spared. It limped along as a dirty, working-class zone until the 1960s, when it was transformed and gentrified.

Across the street from the Carnavalet Museum (described next), on the corner, is the storefront of a long-gone boulangerie-pâtisserie. Its facade is protected and so it survives, even though baked goods are no longer sold here.

• The entrance to the museum is at the intersection of Rue des Francs-Bourgeois and Rue de Sevigné.

Housed inside a Marais mansion, this museum features the history of Paris, particularly the Revolution years. The bloody events of July 14, 1789, come to life in paintings and displays, including a model of the Bastille carved out of one of its bricks. The mansion provides the best possible look at the elegance of the neighborhood back when Place des Vosges was Place Royale. Walking past it, notice the original Carnavalet entrance and the elaborate iron gate through which carriages would enter. For more on the museum, see here. The museum also has a pleasant courtyard café (see “Eateries Along This Walk” sidebar, later).

• Continue west a half-block down Rue des Francs-Bourgeois to the post office. Modern-art fans can check out the nearby Picasso Museum, with temporary exhibits featuring a range of styles and media from the artist’s long life (see here). Turn left onto...

In a few steps, at #24, you’ll pass the 16th-century Paris Historical Library (Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris). Step into the courtyard of this rare Renaissance mansion to see its unstained-glass windows and clean classical motifs. From the street, notice the corner lookout—designed so guards could see from which direction angry peasants were coming.

Continue down Rue Pavée, keeping to the right, until you come to the intersection with Rue des Rosiers. Before we turn right on Rue des Rosiers, consider two little side-trips: A half-block straight ahead leads to the Agoudas Hakehilos synagogue (at #10) with its striking (and filthy) Art Nouveau facade (c. 1913, closed to public). It was designed by Hector Guimard, the same architect who designed Paris’ Art Nouveau Métro stations. A half-block to the left, along Rue des Rosiers, is the recommended Le Loir dans la Théière (at #3). With tasty baked goods and hot drinks, this place provides the perfect excuse for a break.

• From Rue Pavée, turn right onto Rue des Rosiers, which runs straight for three blocks through Paris’ Jewish Quarter.

This street—the heart of the Jewish Quarter (and named for the roses that once lined the city wall)—has become the epicenter of Marais trendiness and fashion, with chic clothing boutiques and stylish cafés.

Once the largest in Western Europe, Paris’ Jewish Quarter, while greatly reduced in size, still reflects its colorful past. Notice the sign above #4, which says Hamam (Turkish bath). Although still bearing the sign of an old public bath, it now showcases trendy clothing. Next door, at #4 bis, the Ecole de Travail (trade school) has a plaque on the wall (left of the door) remembering the headmaster, staff, and students who were arrested here during World War II and killed at Auschwitz.

The size of the Jewish population here has fluctuated. It expanded in the 19th century when Jews arrived from Eastern Europe, escaping pogroms (surprise attacks on villages). The numbers swelled during the 1930s as Jews fled Nazi Germany. After France came under Nazi control, 75 percent of the Jews here were forcibly deported to concentration camps, where many were killed (for more information, visit the nearby Holocaust Memorial—see later). Most recently, Algerian exiles, both Jewish and Muslim, have settled in—living together peacefully here in Paris. (Nevertheless, much of the street has granite blocks on the sidewalk—an attempt to keep out any terrorists’ cars.)

The district’s traditional stores are being squeezed out by the upscale needs of modern Paris. Case in point: The yellow-tiled shop at the intersection of Rue des Rosiers and Rue Ferdinand Duval long thrived as the venerable Jewish deli Jo Goldenberg. A plaque marks a 1982 terrorist bombing that occurred at this spot.

The intersection of Rue des Rosiers and Rue des Ecouffes marks the heart of the small neighborhood that Jews call the Pletzl (“little square”). Lively Rue des Ecouffes, named for a bird of prey, is a derogatory nod to the moneychangers’ shops that once lined this lane. The next two blocks along Rue des Rosiers feature kosher (cascher) restaurants and fast-food places selling falafel, shawarma, kefta, and other Mediterranean dishes. Art galleries exhibit Jewish-themed works, and store windows post flyers for community events. You’ll likely see Jewish men in yarmulkes, a few bearded Orthodox Jews, and Hasidic Jews with black coats and hats, beards, and sidelocks.

Lunch Break: This is a good place to stop. You’ll be tempted by kosher pizza and plenty of cheap fast-food joints selling falafel “to go” (emporter). Choose from any of the many joints that line the street (for suggestions, see the sidebar). For a breath of fresh air, step into the very Parisian Jardin des Rosiers, a half-block before the L’As du Falafel eatery, at 10 Rue des Rosiers.

• Rue des Rosiers dead-ends at Rue Vieille-du-Temple. Turn left on Rue Vieille-du-Temple, then take your first right onto Rue Ste. Croix de la Bretonnerie and prepare for a little cultural whiplash (from Jewish culture to gay culture).

Side Trip to the Holocaust Memorial: Consider a five-block detour to visit the memorial (for details, see the listing on here). To get there, head south on Rue Vieille-du-Temple, cross Rue de Rivoli, and make your second left onto the traffic-free passageway named Allée des Justes. It’s at 17 Rue Geoffroy l’Asnier.

Gay Paree’s openly gay main drag is lined with cafés, lively shops, and crowded bars at night. Check out Le Point Virgule theater to see what form of edgy musical comedy is showing tonight (the name means “The Semicolon”; most productions of up-and-coming humorists are in French). A short detour left on Rue du Bourg Tibourg leads to the luxurious tea extravaganza of Mariage Frères (#30).

Farther ahead at Rue du Temple, consider detouring a few blocks to the right to the Jewish Art and History Museum (see listing on here). On the way, you’ll pass a dance school wonderfully situated in a 17th-century courtyard above the Café de la Gare theater (41 Rue du Temple).

• Continue west on Rue Ste. Croix (which turns into Rue St. Merri). Up ahead you’ll see the colorful pipes of the Pompidou Center. Cross Rue du Renard and enter the Pompidou’s colorful world of fountains, restaurants, and street performers.

Survey this popular spot from the top of the sloping square. Tubular escalators lead to the museum and a great view.

The Pompidou Center subscribes with gusto to the 20th-century architectural axiom “form follows function.” To get a more spacious and functional interior, the guts of this exoskeletal building are draped on the outside and color-coded: vibrant red for people lifts, cool blue for air ducts, eco-green for plumbing, don’t-touch-it yellow for electrical stuff, and white for the structure’s bones. (Compare the Pompidou Center to another exoskeletal building, Notre-Dame.)  See the Pompidou Center Tour chapter for details on visiting the museum.

See the Pompidou Center Tour chapter for details on visiting the museum.

The adjacent fountain, an homage to Igor Stravinsky, has been under renovation for years. Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint-Phalle designed it as a tribute to the composer. When functional again, you’ll appreciate how every sculpture within the fountain represents one of his hard-to-hum scores. For low-stress meals or an atmospheric spot for a drink, try the lighthearted Dame Tartine (or the crêperie next door), which overlooks the fountains and serves good, inexpensive food (see the sidebar, earlier).

• Double back to Rue du Renard, turn right, and stroll past Paris’ ugliest (modern) building on the left. Walk toward the river until you find...

Looking more like a grand château than a public building, Paris’ City Hall stands proud. This spot has been the center of city government since 1357. Each of Paris’ 20 arrondissements has its own City Hall and mayor, but this one is the big daddy of them all.

The Renaissance-style building (built 1533-1628 and reconstructed after a 19th-century fire) displays hundreds of statues of famous Parisians on its facade. Peek from behind the iron fences through the doorways to see elaborate spiral stairways, which are reminiscent of Château de Chambord in the Loire. Playful fountains energize the big, lively square in front.

This spacious stage has seen much of Paris’ history. On July 14, 1789, Revolutionaries rallied here on their way to the Bastille. In 1870, it was home to the radical Paris Commune. During World War II, General Charles de Gaulle appeared at the windows to proclaim Paris’ liberation from the Nazis. And in 1950, Robert Doisneau snapped a famous black-and-white photo of a kissing couple, with Hôtel de Ville as a romantic backdrop.

Today, it’s the seat of the mayor of Paris, who has one of the most powerful positions in France. In the 1990s, Jacques Chirac used the mayoralty as a stepping stone to another powerful position—president of France.

The square in front is a gathering place for Parisians. Demonstrators assemble here to speak their minds. Crowds cheer during big soccer games shown on huge TV screens. In summer, the square hosts sand volleyball courts; in winter, a big ice-skating rink. There’s often a children’s carousel, or manège. Now a Paris institution, carousels were first introduced by Henri IV in 1605—the same year Place des Vosges was built. Year-round, the place is always beautifully lit after dark.

After our walk through the Marais, one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods, it’s appropriate to end up here, at the governmental heart of Paris.

• The tour’s over. The Hôtel de Ville Métro stop is right here. If you need information, Paris’ main TI is in the Hôtel de Ville (enter from the north side of the building at 29 Rue de Rivoli).