There are many causes for the overall quality of industrially produced products being lower than they might be. As discussed, one is lack of awareness and attention paid to quality. We just don’t think about it enough and take those often simple actions that would increase it. When students would finish my course on quality and ask me how to continue to learn about overall product quality, I would advise them to simply keep paying attention to it—if possible to become obsessed with it.

Another cause of low quality is the nature of life in the modern world. We are living in a time of strong materialistic desires and widespread capitalism, even in countries that describe themselves as communist or socialist: Russia, China, Venezuela, and Finland want to make money, as do the United States, England, India, and Germany. It is often possible to make a fast buck by producing an item that is not as good as it might be, especially if it is promoted well and sold cheaply. Eventually, however, high overall quality produces the high value added and profitability that businesses seek. Do we in the United States think we will become the world’s leader in making things cheaply? Give me a break. Besides, it is more fun to make the best.

Most of us who buy products are quite occupied with day-today activities in life and tend to concentrate on the issues that cry for immediate attention, which may not include the overall quality of the products we purchase. In fact, we typically focus more on quality when a product fails or otherwise disappoints us than we do when we acquire it. Most of us buy a mattress because a friend bought that brand, or because the maker is an old name in mattresses, or because of a good salesperson, or an influential TV ad, or a low price, and maybe because we reclined upon it for a few minutes in a store. But when we really become aware of the bed’s quality is after a couple of weeks of sore backs in the morning.

We buy a car with a large number of electrical and electronic features, and love them greatly until after 50,000 miles, when they begin to fail and cost an unexpectedly large amount to have repaired. Only then do we talk to others who have had the same experience and become critical of the car. We buy an expensive formal dress because it is so fashionable, but become unhappy when it becomes unfashionable, well before we have gotten our money’s worth out of it, then begin thinking more deeply about the role of fashion in clothing. We are continuously mildly disgruntled owners of many of our possessions.

If we work in a company that manufactures products, many considerations consume our consciousness—schedule, short-term profit, budgets, job reviews, facilities, morale, competition, travel, and how to reduce the amount of e-mail we receive. Specific product goals usually focus on characteristics that are measurable, and these goals are often ambitious enough to squeeze out less tangible considerations. Overall quality again may receive short shrift and not qualify for the level of attention and conscious effort that it deserves.

As I have said many times in the book, quality is a multidimensional and complicated topic. There is no simple way to quantify it, and language leaves us short when discussing it and communicating what we mean. We evaluate the overall quality of a product with a mixture of logical thinking and emotional response.

I began the course that this book is drawn upon because I wanted to cover a number of topics about quality that were hard to discuss logically and treat quantitatively. I underestimated the difficulty of teaching a course of that nature, but fortunately I could put in a large experiential component by having the students rate and attempt to improve existing products and design and make projects of their own. Now here I am writing a book on these topics that are difficult to discuss logically and treat quantitatively. I must like to suffer.

When topics are difficult, it is often easier to think about them by breaking them down into parts—the analytical approach. The topics in Chapters 3 through 9 in the book correspond to useful parts of the whole. I believe that they are basic parts, but I won’t argue that they are the only ones. They are ones I have chosen through many years of thinking and teaching about the topic. I have tested these topics on a large number of people in many fields in many countries, and I am convinced that they help people think about the overall quality problem. Hopefully they convey some useful information, stimulate some thought, and make you more aware of the issue.

The Thought Problems at the end of the chapters are paraphrased student assignments. Comparing and consciously criticizing the quality of products demands your attention, increases your awareness, and builds your ability to discriminate between good and bad in a more useful manner. Next time you see something you would love to have, try to figure out why you react to it in that way. Next time you set forth to buy some common product, look at several competing ones and think deeply about why you prefer one over the others. The reason for these exercises was to fill in aspects of quality that are difficult to convey in words. These types of activities and extrinsic knowledge worked well in the classes I taught, and I am immodest enough to think they would also be fun and worthwhile for you. This book contains a large amount of information about product quality and how to improve it, but to change behavior, this information needs to be augmented by experimentation and usage. To really understand product quality, you need to become involved in the issue.

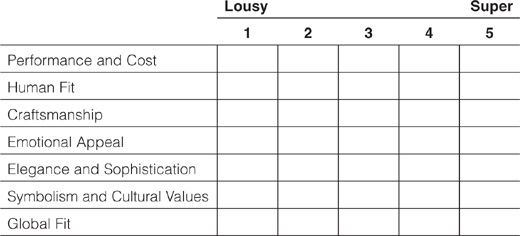

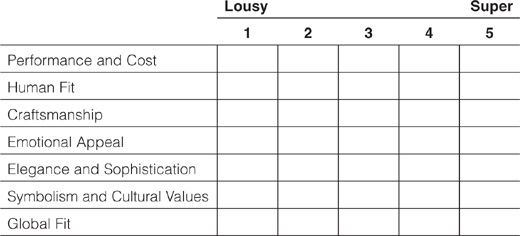

If you would like an easy way to play around with product quality, let me give you a simple matrix based on this book that you can use as an approach to evaluating product quality: Table 10.1, the “Good Product, Bad Product Matrix.”

Table 10.1 Good Product, Bad Product Matrix

Grade some products that you own, would like to own, or are involved in producing, on quality, considering each chapter topic in order. If most of the grades are 4s or 5s, as far as you are concerned, the product is a very good one. If some of the grades are lower, but most are still high, it is still a good product, because not all products can be perfect. It is unusual for a product to reach the top in all categories, but if the scores are mostly 1s, 2s, and 3s, why do you even bother with the product? Aren’t we reaching the point where we can no longer afford lousy or even mediocre products? If you are considering buying such a product, don’t. If you own it, get rid of it. If your company is considering producing it, stop it while you can. Or improve the product. Can you think of easy ways to improve it based on these grades? If it were improved, would it necessarily cost more, and if so why? This matrix, incidentally, can give insight on comparing competing products. And if you really consider yourself good at using the matrix, try making a version with grades between 1 and 10.

While struggling through writing this book, I sometimes wondered what has brought me from my simpler early days of trying to figure out how things work to trying to figure out how to make things better. Partially it is because I like to think about difficult things like quality. But even more, it is because the time to worry about improving quality in our industrial products has definitely arrived. Our population and expectations have increased to the point where we can no longer afford to make junk and throw it away when it breaks or when we are tired of it. High-quality products, whether they be cheap or expensive, help solve many of our problems, from the individual level to global. Quality, though difficult to quantify, can improve our lives while reducing the damage to the ecosphere on which our lives depend. It can improve value added for corporations producing products ranging from mosquito coil burners costing a few rupees to airliners costing millions of dollars. It can increase pride of ownership as well as the morale of those building the product. A perfect hammer (or nail gun) can ease our day’s labor, just as a beautifully designed hybrid can contribute to our feelings of enjoyment and social responsibility as we do our errands. If I were promoting a sound bite, it would be “Better quality is good.”