CHAPTER TWO

Developing Effective Performance Management Systems

How do you go about creating and installing a performance management system in a public or nonprofit organization? How can you ensure that such a system is designed to meet the needs it is intended to serve? What are the essential steps in the design and implementation process?

The Design and Implementation Process

Those who have responsibility for developing performance management systems must proceed deliberately and systematically if they are to develop systems that are used effectively for their intended purposes. This chapter presents a step-by-step process for developing a performance management system that can help manage agencies and programs more effectively.

As we discussed in chapter 1, performance management is the purposive use of quantitative performance information to support management decisions that advance the accomplishment of organizational (or program) goals. The performance management framework organizes institutional thinking strategically toward key performance goals and strives to orient decision-making and policymaking processes toward greater use of performance information to stimulate learning and improvement. This is an ongoing cycle of key organizational management processes that interact in meaningful ways with performance measurement.

Performance measurement and performance management are often used interchangeably, although they are distinctly different. Performance measurement helps managers monitor performance. Many governments and nonprofits have tracked inputs and outputs and, to a lesser extent, efficiency and effectiveness. These data have been reported at regular intervals and communicated to stakeholders. This type of measurement is a critical component of performance management. However, measuring and reporting alone rarely lead to organizational learning and improved performance outcomes. Performance management, however, encompasses an array of practices designed to create a performance culture. Performance management systematically uses measurement and data analysis as well as other management tools to facilitate moving from measurement and reporting to learning and improving results.

Performance management systems come in all shapes and sizes. They may be comprehensive systems that include strategic planning, performance measurement, performance-based budgeting, and performance evaluations or those that establish goals and monitor detailed indicators of a production process or service delivery operation within one particular agency every week; others track a few global measures for an entire state or the nation as a whole on an annual basis. Some performance measurement systems are intended to focus primarily on efficiency and productivity within work units, whereas others are designed to monitor the outcomes produced by major public programs. Still others serve to track the quality of the services provided by an agency and the extent to which clients are satisfied with these services. What differentiates these programs as performance management is that the data are used to manage, make decisions, and improve programs.

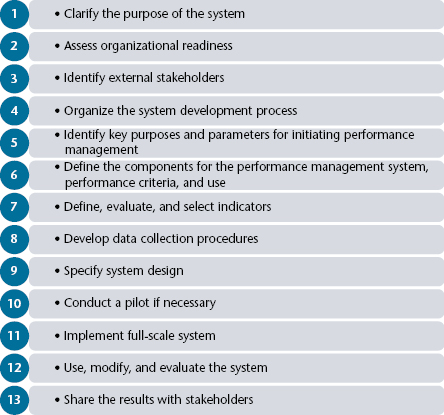

Yet all of these different kinds of performance management and measurement systems can be developed with a common design and implementation process. The key is to tailor the process to both the specific purpose for which a particular system is being designed and to the program or agency whose performance is being measured. Figure 2.1 outlines a process for designing and implementing effective performance management systems. It begins with clarifying the purpose of the system and securing management commitment and proceeds through a sequence of essential steps to full-scale implementation and evaluation.

Step One: Clarify the Purpose of the System

Before getting started, it is important to clarify the purpose of the system. Questions that should be answered include these:

- Is it to support implementation and management of an agency's strategic agenda, manage employees, manage programs, manage organizations, support quality improvement efforts, manage grants and contracts, or inform budget decision making?

- How will the performance measures be used to help manage more effectively?

- With whom will the data be shared?

- Who will be involved in regular reviews of the performance information?

- How will the information be provided to the decision makers?

- What kinds of decisions and actions are the performance data expected to inform—for example, goals, priorities, resource allocation and utilization, operating procedures, program design and operation, work processes, personnel, organization design and functioning?

- What kinds of incentives are being used explicitly or implicitly to encourage working harder and smarter to strengthen performance?

Step Two: Assess Organizational Readiness

The second step in the process is to secure management commitment to the design, implementation, and use of the performance management system. If those who have responsibility for managing the agency, organizational units, or particular programs do not intend to use the management system or are not committed to sponsoring its development and providing support for its design and implementation, the effort will have little chance of success. Thus, it is critical at the outset to make sure that the managers of the department, agency, division, or program in question—those whose support for a performance management system will be essential for it to be used effectively—are on board with the effort and committed to supporting its development and use in the organization. It is important to have the commitment of those at various levels in the organization, including those who are expected to be users of the system and those who will need to provide the resources and ensure the organizational arrangements needed to maintain the system.

Organizations should be assessed on readiness that allow for levels of more or less complex systems to management performance (Van Dooren, Bouckaert, & Halligan, 2010). Niven (2003) provides ten criteria for evaluating the organization's readiness to implement and sustain performance management:

- A clearly defined strategy

- Strong, committed sponsorship or a champion

- A clear and urgent need

- The support of midlevel managers

- An appropriately defined scale and scope

- A strong team with available resources

- A culture of measurement

- Alignment between management and information technology

- Availability of quality data

- A solid technical infrastructure

Step Three: Identify External Stakeholders

It will be helpful to have commitments from external stakeholders—for example, customer groups, advocacy groups, and professional groups. If agreement can be developed among the key players regarding the usefulness and importance of a system, with support for it ensured along the way, the effort is ultimately much more likely to produce an effective management system. If such commitments are not forthcoming at the outset, it is probably not a workable situation for developing a useful system. (More on external stakeholders will be found in chapter 13.)

Step Four: Organize the System Development Process

Along with a commitment from higher levels of management, the individual or group of people who will take the lead in developing the management system must also organize the process for doing so. Typically this means formally recognizing the individual or team that will have overall responsibility for developing the system, adopting a design and implementation process to use (like the one shown in figure 2.1), and identifying individuals or work units that may be involved in specific parts of that process. This step includes decisions about all those who will be involved in various steps in the process—managers, employees, staff, analysts, consultants, clients, and others. It also includes developing a schedule for undertaking and completing various steps in the process. Beyond timetables and delivery dates, the individual or team taking the lead responsibility might find it helpful to manage the overall effort as a project. We return to issues concerning the management of the design and implementation process in chapter 15.

Step Five: Identify Key Purposes and Parameters for Initiating Performance Management

The fifth step in the process is to build on step two and clarify the purpose of the management system and the parameters within which it is to be designed. Purpose is best thought of in terms of use:

- Who are the intended users of this system, and what kinds of information do they need from it?

- Will this system be used simply for reporting and informational purposes, or is it intended to generate data that will assist in making better decisions or managing more effectively?

- Is it being designed to monitor progress in implementing an agency's strategic initiatives, inform the budgeting process, manage people and work units more effectively, support quality improvement efforts, or compare your agency's performance against other similar organizations?

- What kinds of performance data can best support these processes, and how frequently do they need to be observed?

Chapters 8 through 14 discuss the design and use of performance measures for these purposes, and it becomes clear that systems developed to support different management processes will themselves be very different in terms of focus, the kinds of measures that are used, the level of detail involved, the frequency of reporting performance data, and the way in which the system is used. Thus, it is essential to be clear about the purpose of a performance measurement system at the outset so that it can be designed to maximum advantage.

Beyond the questions of purpose and connections between the performance measurement system and other management and decision-making processes, system parameters are often thought of in terms of both scope and constraints. Thus, system designers must address the following kinds of questions early on in the process:

- What is the scope of the new system?

- Will it focus on organizational units or on programs?

- Will it cover a particular operating unit, a division, or the entire organization?

- Do we need data for individual field offices, for example, or can the data simply be rolled up and tracked for a single, larger entity?

- Should the measures comprehend the entire, multifaceted program or just one particular service delivery system?

- Who are the most important decision makers regarding these agencies or programs, and what kinds of performance data do they need?

- Are there multiple audiences for the performance data to be generated by this system, possibly including internal and external stakeholders?

- Are reports produced by this system likely to be going to more than one level of management?

- What are the resource constraints within which this measurement system will be expected to function?

- What level of effort can be invested in support of this system, and to what extent will resources be available to support new data collection efforts that might have to be designed specifically for this system?

- Are any barriers to the development of a workable performance measurement system apparent at the outset?

- Are some data that would obviously be desirable to support this system simply not available?

- Would the cost of some preferred data elements clearly exceed available resources? If so, are there likely to be acceptable alternatives?

- Is there likely to be resistance to this system on the part of managers, employees, or other stakeholders whose support and cooperation are essential for success? Can we find ways to overcome this problem?

The answers to these kinds of questions will have a great influence on the system's design, so they will need to be addressed very carefully. Sometimes these parameters are clear from external mandates for performance management systems, such as legislation of reporting requirements for jurisdiction-wide performance and accountability or monitoring requirements of grants programs managed by higher levels of government. In other cases, establishing the focus may be a matter of working closely with the managers who are commissioning a performance management system in order to clarify purpose and parameters before proceeding to the design stage.

Step Six: Define the Components for the Performance Management System, Performance Criteria, and Use

There are several performance management systems that many governments and nonprofits are using, including strategic planning based on mission, mandates, goals, objectives, strategies, and measures found in chapter 8 of this book; the balanced scorecard found in chapter 8; and the Stat system approach (e.g., CompStat and CitiStat) found in chapter 13. Organizations may adopt one of these approaches fully or partially, or select elements from several to create their own unique system. For example, the State of Delaware is among governments that use the framework in the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award program, focusing on leadership, strategic planning, customer focus, measurement, process management, and improving results. This model recommends a structured approach to management based on criteria set up for receiving the Baldrige Award.

Important areas to consider, according to Kamensky and Fountain (2008), include:

- Leadership meetings for discussions of the performance of the various programs

- The commitment of program managers and key contributors to the system

- Links to resources, with discussion that includes whether the performance information will be used in the budget decisions

- The role of granters or networks in delivering the services and how their performance will be used in the system

- Stakeholder feedback and how it will be used to inform performance

- Evaluation of programs to improve performance

- How nonachieving programs will be handled

This sixth step also requires the identification of the intended outcomes, use, and other performance criteria to be monitored by the measurement system:

- What are the key dimensions of performance of the agency or program that you should be tracking?

- What services are being provided, and who are the customers?

- What kind of results are you looking for?

- How do effectiveness, efficiency, quality, productivity, customer satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness criteria translate into this program area?

- How will this information be used? Will it inform budget decisions?

Chapter 3 is devoted to the subject of identifying program outcomes and other performance criteria. It introduces the concept of logic models that outline programmatic activity, immediate products, intermediate outcomes, and ultimate results and the presumed cause-and-effect relationships among these elements. Analysts, consultants, and other system designers can review program plans and prior research and can work with managers and program delivery staff, as well as with clients, and sometimes other external stakeholders, to clarify what these elements really are. Once a program logic model has been developed and validated with these groups, the relevant performance criteria can be derived directly from the model.

Remember that the ultimate purpose of these systems is program improvement. How will this information be used to improve programs? Chapter 4 elaborates on the all-important linkage of performance measures to goals and objectives. Chapter 9 addresses the use of performance information in budgeting.

Step Seven: Define, Evaluate, and Select Indicators

When consensus has been developed on what aspects of performance should be incorporated in a particular performance management system, the question of how to measure these criteria may begin to be addressed. As discussed in chapter 5, this involves defining, evaluating, and then selecting preferred performance indicators. Questions to consider include these:

- How should certain measures be specified?

- What about the reliability and validity of proposed indicators?

- How can you capture certain data elements, and to what extent will this entail collecting original data from new data sources?

- Is the value of these indicators worth the investment of time, money, and effort that will be required to collect the data?

- Will these measures set up appropriate incentives that will help to improve performance, or could they actually be counterproductive?

This is usually the most methodologically involved step in the process of designing performance management systems. It cuts to the heart of the issue: How will you measure the performance of this agency or program on an ongoing basis? The ideas come from prior research and other measurement systems, as well as from goals, objectives, and standards and from the logical extension of the definition of what constitutes strong performance for a particular program. Sometimes it is possible to identify alternative indicators for particular measures, and in fact the use of multiple or cascading measures is well advised. In addition, there are often trade-offs between the quality of a particular indicator and the practical issues in trying to operationalize it. Thus, as discussed in chapter 5, it is important to identify potential measures and then evaluate each one on a series of criteria in order to decide which to include in the monitoring system.

Step Eight: Develop Data Collection Procedures

Given a set of indicators to be incorporated in a performance management system, the next step in the design process is to develop procedures for collecting and processing the data on a regular basis. The data for performance monitoring systems come from a wide variety of sources, including agency records, program operating data, existing management information systems, direct observation, tests, clinical examinations, various types of surveys, and other special measurement tools. As discussed in chapter 7, in circumstances where the raw data already reside in established data files maintained for other purposes, the data collection procedures involve extracting the required data elements from these existing databases. Within a given agency, this is usually accomplished by programming computer software to export and import specific data elements from one database to another. Sometimes, particularly with respect to grant programs, for example, procedures must be developed for collecting data from a number of other agencies and aggregating them in a common database. Increasingly this is accomplished through interactive computer software over the Internet.

In other instances, operationalizing performance indicators requires collecting original data specifically for the purposes of performance measurement. With respect to tests, which may be needed to rate client or even employee proficiency in any number of skill areas or tasks as well as in educational programs, there are often a number of standard instruments to choose from or adapt; in other cases, new instruments have to be developed. This is also the case with respect to the kinds of medical, psychiatric, or psychological examinations that are often needed to gauge the outcomes of health care or other kinds of individual or community-based programs. Similarly, instruments may need to be developed for direct observation surveys in which trained observers rate particular kinds of physical conditions or behavioral patterns.

Some performance measures rely on surveys of clients or other stakeholders, and these require decisions about the survey mode—personal interview, telephone, mail-out, individual or group administered, or computer based—as well as the adaptation or design of specific survey instruments. In addition to instrument design, these kinds of performance measures require the development of protocols for administering tests, clinical examinations, and surveys so as to ensure the validity of the indicators as well as their reliability through uniform data collection procedures. Furthermore, the development of procedures for collecting original data, especially through surveys and other kinds of client follow-up, often requires decisions about sampling strategies.

With regard to both existing data and procedures for collecting original data specifically for performance measurement systems, we need to be concerned with quality assurance. As mentioned in chapter 1, performance management systems are worthwhile only if managers and decision makers actually use them for program improvement, and this will happen only if the intended users have faith in the reliability of the data. If data collection procedures are sloppy, the data will be less than reliable, and managers will not have confidence in them. Worse, if the data are biased somehow because, for example, records are falsified or people responsible for data entry in the field tend to include some cases but systematically exclude others, the resulting performance data will be distorted and misleading. As will be discussed in chapter 7, there needs to be provision for some kind of spot checking or systematic data audit to ensure the integrity of the data being collected.

Step Nine: Specify System Design

At some point in the design process, you must make decisions about how the performance management system will operate. One of these decisions concerns reporting frequencies and channels—that is, how often particular indicators will be reported to different intended users. As will become clear in chapters 8 through 14, how you make this decision will depend primarily on the specific purpose of a monitoring system. For example, performance measures developed to gauge the outcomes of an agency's strategic initiatives might be reported annually, whereas indicators used to track the outputs and labor productivity of a service delivery system in order to optimize workload management might well be tracked weekly. In addition to reporting frequency, there is the issue of which data elements go to which users. In some cases, for instance, detailed data broken down by work units might be reported to operating-level managers, while data on the same indicators might be rolled up and reported in the aggregate to senior-level executives.

System design also entails determining what kinds of analysis the performance data should facilitate and what kinds of reporting formats should be emphasized. As discussed in chapter 6, performance measures do not convey information unless the data are reported in some kind of context through comparisons over time, against targets or standards, among organizational or programmatic units, or against external benchmarks. What kind of breakouts and comparisons should you employ? In deciding which analytical frameworks to emphasize, you should use the criterion of maximizing the usefulness of the performance data in terms of the overall purpose of the monitoring system. As illustrated in chapter 7, a great variety of reporting formats is available for presenting performance data, ranging from spreadsheet tables, graphs, and symbols to pictorial and dashboard displays; the objective should be to employ elements of any or all of these to present the data in the most intelligible and meaningful manner.

Furthermore, computer software applications have to be developed to support the performance management system from data entry and data processing through to the generation and distribution of reports, which increasingly can be done electronically. As discussed in chapter 7, a variety of software packages may be useful along these lines, including spreadsheet, database management, and graphical programs, as well as special software packages available commercially that have been designed specifically to support performance monitoring systems. Often some combination of these packages can be used most effectively. Thus, system designers have to determine whether their performance monitoring system would function more effectively with existing software adapted to support the system or with original software developed expressly for that system.

A final element of system specification is to assign personnel responsibilities for maintaining the performance management system when it is put into use. As discussed in chapter 15, this includes assigning responsibilities for data entry, which might well be dispersed among various operating units or field offices (or both), as well as for data processing, quality assurance, and reporting. Usually primary responsibility for supporting the system is assigned to a staff unit concerned with planning and evaluation, management information systems, budget and finance, management analysis, quality improvement, or customer service, depending on the principal use for which the system is designed. In addition, clarification of who is responsible for reviewing and using the performance data is needed, and establishment of deadlines within reporting cycles for data entry, processing, distribution of reports, and review.

Step Ten: Conduct a Pilot If Necessary

Sometimes it is possible to move directly from design to implementation of performance management systems, particularly in small agencies where responsibilities for inputting data and maintaining the system will not be fragmented or with simple, straightforward systems in which there are no unanswered questions about feasibility. However, in some cases, it may be a good idea to pilot the system, or elements of it at least, before committing to full-scale implementation. Most often, pilots are conducted when there is a need to test the feasibility of collecting certain kinds of data, demonstrate the workability of the administrative arrangements for more complex systems, get a clearer idea of the level of effort involved in implementing a new system, testing the software platform, or simply validating newly designed surveys or other data collection instruments. When there are real concerns about these kinds of issues, it often makes sense to conduct a pilot, perhaps on a smaller scale or sample basis, to get a better understanding of how well a system works and of particular problems that need to be addressed before implementing the system across the board. You can then make appropriate adjustments to the mix of indicators, data collection efforts, and software applications in order to increase the probability that the system will work effectively.

Step Eleven: Implement Full-Scale System

With or without benefit of a pilot, implementing any new management system presents challenges. Implementation of a performance management system means collecting and processing all the required data within deadlines, running the data and disseminating performance reports to the designated users on a timely basis, and reviewing the data to track performance and use this information as an additional input for decision making. It also includes initiating quality assurance procedures and instituting checks in data collection procedures where practical to identify stray values and otherwise erroneous data.

With larger or more complex systems, especially those involving data input from numerous people in the field, some training may well be essential for reliable data. As discussed in chapter 15, the most important factor for guaranteeing the successful implementation of a new monitoring system is a clear commitment from top management, or the highest management level that has commissioned a particular system, to providing reliable data and using the system effectively as a management tool.

Step Twelve: Use, Modify, and Evaluate the System

No matter how carefully a system may have been implemented, problems are likely to emerge in terms of data completeness, quality control, software applications, or the generation of reports. The level of effort required to support the system, particularly in terms of data collection and data entry, may also be a real concern as well as an unknown at the outset. Thus, over the first few cycles—typically months, quarters, or years—it is important to closely monitor the operation of the system itself and evaluate how well it is working. And when implementation and maintenance problems are identified, they need to be resolved quickly and effectively.

Managers must begin to assess the usefulness of the measurement system as a tool for managing more effectively and improving decisions, performance, and accountability. If a performance management system is not providing worthwhile information and helping gain a good reading on performance and improve substantive results, managers should look for ways to strengthen the measures and the data or even the overall system. This is often a matter of fine-tuning particular indicators or data collection procedures, adding or eliminating certain measures, or making adjustments in reporting frequencies or presentation formats to provide more useful information, but it could also involve more basic changes in how the data are reported and used in management and decision-making processes. Depending on what the performance data show, experience in using the system might suggest the need to modify targets or performance standards or even to make changes in the programmatic goals and objectives that the measurement system is built around.

Evaluation must be a component of performance management because understanding the casual relationship between the activities the organization carries out and the results it achieves is necessary to learning, improvement, and accountability. It is the follow-up step whereby the results of programs and expenditures can be assessed according to expected results. Evaluations, discussed in chapter 10, rely on developing evaluation objectives that program results can be measured against. A basic performance evaluation has the following phases:

- Define the evaluation question.

- Establish a data collection strategy based on the question.

- Collect the data, which may require more than a single tool or method.

- Analyze and report the findings, and make recommendations for program improvement.

Data validation, discussed in chapter 7, is an important component of evaluation, and a performance management system will not function well without valid and reliable data. Staff must be trained in both the importance of having reliable data and how to test for reliability. If the validity of data is not addressed, performance management systems could create and communicate inaccurate pictures of actual performance.

Step Thirteen: Share the Results with Stakeholders

Stakeholder involvement is an important component of performance management. As discussed in chapter 13, developing a stakeholder feedback effort will help all parties gain understanding and develop and maintain support for the public and nonprofit programs. By inviting feedback and questions, not just providing information, a good communication process can counter inaccurate information and faulty perceptions by rapidly identifying inaccuracies and making sure that accurate and relevant information is provided. It is important to note that stakeholders may also consist of other public, nonprofit, and private sector actors, as many public services are the joint efforts of collaborations between governmental and nongovernmental actors.

A Flexible Process

Developing a performance management systems is both an art and a science. It is a science because it must flow systematically from the purpose of the system and the parameters within which it must be designed and because the particulars of the system must be based on an objective logic underlying the operation of the agency, program, or service delivery system to be monitored. However, it is also an art because it is a creative process in terms of defining measures, reporting formats, and software applications and it must be carried out in a way that is sensitive to the needs of people who will be using it and that will build credibility and support for the system along the way.

There is perhaps no precise “one right way” to develop a performance management system. Success will stem in part from tailoring the design and implementation process to the particular needs of the organization or program in question. Although the steps outlined in this chapter are presented in a logical sequence, this should not be viewed as a rigid process. Indeed, as is true of any other creative effort, designing and implementing performance measurement systems may at times be more iterative than sequential. Although the steps presented in figure 2.1 are all essential, integrating them is much more important than performing them in a particular sequence.

Utilization is the primary test of the worth of any performance management system. Thus, performing all the steps in the design and implementation process with a clear focus on the purpose of a particular monitoring system and an eye on the needs of its intended users is critical to ensuring that the performance measures add value to the agency or the program. To this end, soliciting input along the way from people who will be working with the system—field personnel, systems specialists, analysts, and managers—as well as others who might have a stake in the system, such as clients or governing boards, can be invaluable in building credibility and ownership of the system once it is in place.

References

- Kamensky, J., & Fountain, J. (2008). Creating and sustaining a results-oriented performance management framework. In P. DeLancer Julnes, F. Berry, M. Aristigueta, & K. Yang (Eds.), International handbook of practice-based performance management (pp. 489–508). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Niven, P. (2003). Balanced scorecard step by step for government and nonprofit agencies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Van Dooren, W. Bouckaert, G., & Halligan, J. (2010). Performance management in the public sector. Abingdon, Oxon, OX: Routledge.