Superpowers have rather surprising effects on substantive criminal law. 1 Consider the many questions raised by psychic powers, for example. Psychic supervillain Dr. Psycho was once put on trial for causing a crowd of bystanders to commit murder. This raises two questions: can he be held liable for doing so, and what defense do the bystanders have? Or consider Wonder Woman, who was charged with the murder of Maxwell Lord after killing him in order to stop him from causing Superman to attack his friends. If her case had gone to trial, could she have invoked self-defense or defense of others? More fundamentally, is reading someone’s mind itself a crime? This chapter deals with these kinds of questions.

While some may think of crimes as a kind of general “doing bad stuff” with particular kinds of bad stuff associated with particular crimes, this will not suffice as a legal analysis. Crimes are carefully and specifically defined as consisting of “elements,” just like molecules are composed of atoms. This careful specification is important because serious ambiguities in the definition of a crime can be interpreted in favor of the defendant, per the rule of lenity. 2 These elements are divisible into two main categories: “actus reus” and “mens rea,” Latin for “guilty act” and “guilty mind,” respectively. These are basically the same as “act” and “intent.”

The act element is probably the one that most people identify with intuitively. Murder involves killing, theft involves taking other people’s stuff, etc. But the level of detail with which criminal acts are defined may come as a surprise. For example, the act element of murder is the “unlawful killing of another.” All three of the main words in that definition are important. For starters, there must be a killing. No murder if the victim isn’t dead. But that killing must be “unlawful,” as there are a number of circumstances under which killing is legally justified. 3 The most obvious example is killing in self-defense, but we can also include soldiers killing in wartime or police officers killing a fleeing violent felon. Lastly, the killing must be “of another.” Suicide may be morally problematic, and it’s even a crime in some jurisdictions, but it isn’t murder because it doesn’t fit the definition. Implied in the “of another” element is that the victim must be a person. 4 Slaughtering pigs isn’t murder, and the legal system is pretty resistant to classifying people as anything other than human.

On the other hand, the intent element is not something that most people immediately think of when discussing criminal law, but it is intuitive enough that most people will recognize its validity almost right away. People recognize a difference between doing something on purpose and doing something accidentally. As the great American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes put it, “Even a dog distinguishes between being stumbled over and being kicked.” 5 The law generally recognizes five different “levels” of intent: intentional/purposeful, knowledgeable, reckless, negligent, and strict liability. 6 “Purposeful” actions are done with the “conscious object” that the act be accomplished and the consequences occur. “Knowledgeable” actions are done with the knowledge that a particular result is a practical certainty, but they are not specifically intended by the actor. “Reckless” acts are done with conscious disregard of known risks in a way that a normal, law-abiding person would not have done. “Negligent” acts are those that involve a risk that a reasonable person should have perceived but did not actually perceive. Lastly, there are some crimes for which there is no intent element at all, i.e., liability is “strict.” For instance, it doesn’t matter whether or not you meant to speed, if you did it, you’re guilty.

With those definitions out of the way, we can explore how throwing superpowers into the mix does odd and sometimes unexpected things to the elements of particular crimes.

There are a number of different crimes whose actus reus might be affected by superpowers.

Ra’s al Ghul has a nasty habit of coming back from the dead, even more so than most comic book villains. Grant Morrison et al., THE RESURRECTION OF RA’S AL GHUL (2008).

Let’s start with the big one: murder. As discussed, murder requires that someone die. But what if the dead don’t stay dead? Take Ra’s al Ghul. In DC’s 2007–08 The Resurrection of Ra’s al Ghul event, Ra’s, having been killed by his daughter Nyssa some years prior, is returned to life by a “Fountain of Essence,” similar in function to the Lazarus Pits that Ra’s had used to keep himself alive for centuries. In this particular story, killing Ra’s does not seem to have been a crime, but what if the circumstances had been different? What if it was Batman who was killed and brought back to life while his killer sat languishing in Arkham Asylum? In short, does the subsequent resurrection of a murder victim undermine the validity of the original conviction?

With one minor caveat, the answer is “almost certainly not.” The caveat is that we need to be talking about actual, honest-to-goodness resurrection, not one of the myriad ways that comic book writers use to explain why a particular character wasn’t really dead. “I got better!” may be a decent hand-wave reason for bringing a beloved (or hated!) character back into the story, but if it turns out that the victim was never actually dead, then any convictions related to their death will need to be overturned. The law already knows how to deal with that one, as someone seeming to be dead but coming back later is an uncommon but understood phenomenon. While there are no criminal cases on point, there have been a number of civil cases in which someone faked his or her own death for insurance purposes then reappeared some years later. 7

But if the victim did die, then the fact that they later return to life does not matter. The actus reus for murder is simply that the victim has died as a result of the defendant’s actions. The victim’s staying dead is not actually an element of the crime. This is probably the right result too, because unless resurrection becomes some kind of commonly available service, we don’t want the convictions of known murderers to be overturned because there’s been what amounts to a miracle.

Resurrection isn’t the only comic book story element that is in play here. What about Multiple Man? Jamie Madrox has the ability to create duplicates of himself using absorbed kinetic energy. Does killing a “dupe” constitute murder? This one is a much harder call, especially given the fact that Madrox himself can “reabsorb” dupes at any time. The law currently has no mechanism for dealing with this kind of ability, but if we apply a “looks like a duck” analysis, it seems like someone else killing a dupe might well be found guilty of murder. Each dupe is said to possess all of Madrox’s memories up to the point the dupe was created, they are capable of independent thoughts and actions, including making more dupes, and can live separately from the original for an indefinite period of time. Furthermore, killing a dupe leaves a corpse, so it isn’t hard to see a prosecutor taking an interest in pursuing that case. Madrox himself might have an interest in that too, because if it weren’t murder, he would seem to be in constant mortal peril, as who’s to know which is a dupe and which is the original? If it’s open season on dupes, it winds up being open season on Madrox “Prime” too.

Jamie Madrox, the world’s only literal one-man army. Peter David et al., Trust Issues, in X-FACTOR (VOL. 3) 9 (Marvel Comics July 2006).

Deciding the dupes are people is not without side effects, however, both in criminal law and other areas. 8 For example, it’s an interesting question whether Madrox reabsorbing a dupe is itself murder. If the dupes control the process, then it would seem to be a form of suicide, which is generally legal. 9 If the original controls the process, however, then it’s arguably murder, except perhaps in the case of a terminally ill dupe being absorbed in a jurisdiction that explicitly allows assisted suicide. It’s not enough that the dupes want to be reabsorbed: “The lives of all are equally under the protection of the law, and under that protection to their last moment.…[Assisted suicide] is declared by the law to be murder, irrespective of the wishes or the condition of the party to whom the poison is administered.” 10

Attempting a crime, part of what are known as the “inchoate” (i.e., incomplete) offenses, is still a crime, and the punishment for attempted murder can be just as severe as for actual murder, though the death penalty is generally off the table. The layman’s definition of attempted murder is something like “trying to kill someone,” and that’s accurate, roughly speaking. But the technical definition is somewhat more precise. For example, one state statute defines attempted murder as follows:

a. A person commits an attempt when, with intent to commit a specific crime, he does any act which constitutes a substantial step toward the commission of that crime.

b. It shall not be a defense to a charge of attempt that because of a misapprehension of the circumstances it would have been impossible for the accused to commit the crime attempted. 11

What we have here is a rigorous definition for what counts as attempt and what doesn’t, as well as a provision that so-called factual impossibility is not a defense to a charge of attempt.

Let’s break that down a bit. The mens rea for attempt is intentional. Fair enough. It doesn’t make sense to convict someone for trying to do something they weren’t actually trying to do. But the actus reus element is a bit more interesting. It has to be a “substantial step” towards the commission of that crime. Shooting at someone and missing would count under most circumstances. It’s even possible that lying in wait might work too, though the lack of any actual shooting would hurt the prosecution’s case. But buying a gun? Not enough. That’s a step alright, but it’s a perfectly legal activity in and of itself, and doesn’t constitute a concrete step towards a crime.

But what if you shoot Wolverine? That’s not going to kill him. It isn’t even necessarily going to incapacitate him for all that long. Getting shot in the head in X2 seems to have knocked him out for a few minutes at best, and being completely incinerated by Nitro seems to have lasted for only a few minutes, hours at most. So can it truly be said that shooting Wolverine counts as a “substantial step” towards killing him?

At this point we need to look at subsection (b). There, it says that it is not a defense that the act in question would not have accomplished the intended goal as long as the defendant thought that it would. Sneaking into someone’s home after midnight and trying to kill him by emptying a clip into his bed is still attempted murder if the defendant finds out after the fact that the intended victim wasn’t home. But if a defendant realizes that the person isn’t home and empties a clip into the bed out of frustration, that’s a different situation. If the defendant actually knows that what he’s going to do isn’t going to kill the victim, how is that a “substantial step” towards accomplishing the crime? Courts are generally looking for some action that the defendant believes will succeed, regardless of whether or not it could. Believing that an action will not succeed would seem to be a defense to an attempt charge.

He gets better. Marc Guggenheim et al., Vendetta Part 2, Revenge, in WOLVERINE (VOL. 3) 43 (Marvel Comics August 2006).

So turning back to Wolverine, the question becomes whether the person doing the shooting knows that Wolverine isn’t going to die as a result of being shot. If the assailant is someone who has just met him or is unaware of his abilities, he probably believes that shooting Wolverine will kill him, so the fact that it won’t will not serve as a defense. But if we’re talking about someone with whom Wolverine has tangled before, someone from the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants say, the bad guy should know quite well that anything he does isn’t going to kill Wolverine. As such, though any attack would definitely count as an assault, it would not count as attempted murder, because they knew they weren’t going to succeed.

Assault is another crime whose act element is implicated by superpowers. Most jurisdictions distinguish between simple assault and aggravated assault or between different degrees of assault. Simple assault is typically a misdemeanor, whereas aggravated assault is typically a felony. For example, here’s how the Model Penal Code defines simple and aggravated assault:

1. Simple Assault. A person is guilty of assault if he:

a. attempts to cause or purposely, knowingly or recklessly causes bodily injury to another; or

b. negligently causes bodily injury to another with a deadly weapon;

2.Aggravated Assault. A person is guilty of aggravated assault if he:

a. attempts to cause serious bodily injury to another, or causes such injury purposely, knowingly or recklessly under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to the value of human life; or

b. attempts to cause or purposely or knowingly causes bodily injury to another with a deadly weapon.12

Thus, the same intentional act (causing bodily harm) is a misdemeanor if done without a deadly weapon and a felony if done with one. Two issues present themselves: (1) can superpowers count as deadly weapons, and (2) what about telekinetic or psychic powers?

As to the first, Wolverine’s claws would seem to count as a deadly weapon, as would most of the gadgets ginned up by Forge and Batman. But in the end of the “Fatal Attractions” crossover in the early 1990s, Magneto stripped the adamantium from Wolverine’s skeleton, revealing that his claws are actually bone. Do they count as deadly weapons? The question here is whether a natural part of a person’s body counts as a “weapon” in terms of the law. If so, it’s plausible that any significant deviation from the human norm might lead to aggravated assault charges. This would include things like the Hulk’s strength and even Cyclops’s energy beams. It seems plausible that a court might well find that they do count as “deadly weapons.” 13 The theory here is that assaulting someone with a weapon is inherently worse than assaulting someone barehanded for two reasons. First, weapons enable even ordinary people to cause serious harm. The use of a weapon greatly increases the stakes in any conflict.

The second reason is related to the first. Using something other than one’s bare hands also suggests a different sort of mental state. Actus reus can sometimes act as a proxy for mens rea, the latter being more difficult to prove. A defendant who attacks with a gun wants to do more damage and has put more thought into doing so than someone who simply throws a punch. As most superpowered characters didn’t ask for their abilities—the vast majority were either born that way or were powered up as the result of an accident—it seems kind of unjust to hold them to a higher standard just because they can do stuff the rest of us can’t. On the other hand, superhero stories make much of the with-great-power-comes-great-responsibility idea. So ultimately, how a court would rule on whether assault by a superpowered individual constitutes aggravated assault per se would probably wind up depending on the facts of the specific case.

Then there’s the issue of psychic powers, especially telekinesis. A number of superpowered individuals, including Jean Grey, Legion, and Magneto, can exert force on physical objects, including the bodies of others, without actually touching them. This ability can take a variety of forms including telekinesis and the control of magnetic fields, but they all have in common the mental projection of force. Although it might seem strange that a noncorporeal force could cause an assault, courts have recognized that even something as insubstantial as a low-power laser beam can cause an assault. 14

Jean Grey demonstrates her powers of telekinesis by levitating two small objects. Due to the inflation of superpowers over the years, this display looks positively quaint by today’s standards. Stan Lee, Jack Kirby et al., The Uncanny Threat of…Unus, the Untouchable!, in X-MEN (VOL. 1) 8 (Marvel Comics November 1964).

Another kind of psychic power is the manipulation of thoughts or memories. This is also arguably an assault, as manipulating someone’s mind necessarily requires manipulating his or her physical neurons. In the DC Universe, this process even leaves trace evidence in the brain, which has been used as evidence in court to prove psychic manipulation.

While we’re on the subject of superpowers being treated in unexpected ways, there are numerous characters whose powers have been stolen or removed by another, for example by the mutant Rogue. While this almost always involves some kind of assault, is it also theft? Comic book stories certainly use the language of theft to describe these interactions, but would they be viewed as such in the eyes of the law?

So…workers’ compensation claim? Stan Lee, Jack Kirby et al., The Fantastic Four!, in FANTASTIC FOUR (VOL. 1) 1 (Marvel Comics November 1961).

It’s actually hard to say. The actus reus of theft is the taking of another person’s property without permission. At common law there were a variety of different kinds of theft—larceny by trick, larceny by false pretenses, embezzlement, robbery, and the like—but they all have one common element: appropriating another person’s property. Which is where we run into problems, because the courts are pretty clear that while we certainly have an interest in our own bodies, that interest is not actually a property interest. 15

Property is generally considered a “bundle of rights,” including the right to control and use the property, obtain any benefits related to it, transfer or sell it, and to exclude others from it, along with other more technical rights we will not get into here. We generally think that we have those rights in our own bodies, right? So why are our rights in our bodies not considered property rights? We have actuarial tables for how much losing an arm, a leg, or an eye is worth, so why aren’t they property?

Largely because the courts, reflecting their perception of societal mores, are a little squeamish about assigning property rights in human bodies, in no small part due to the idea that recognizing such rights might create a market in human organs. Which is generally considered to be kind of gross. In addition, if we view the human body as being the property of its owner, we get into a pretty bizarre tax situation. For example, would the Fantastic Four’s gaining superpowers while in orbit suddenly become a taxable event? They’ve acquired new “property,” and those sorts of transfers or acquisitions generally require tax reporting. This does not seem to be the way that we want to go.

But more than that, most people’s intuition seems to be that whatever our relationship with our bodies, the relationship is more significant than that of mere ownership. Spitting in someone’s face is somehow morally different from spitting on someone’s lawn, even if the monetary damages are both purely nominal. So “stealing” superpowers is probably better categorized as an assault than as a theft.

Actually, compared to some real-life “experts,” this is pretty unremarkable testimony. Marc Andreyko et al., Psychobabble—Part Two: Mind Over Morals, in MANHUNTER (VOL. 3) 21 (DC Comics June 2006).

As mentioned in the beginning of the chapter, the law already has a pretty sophisticated way of analyzing intent and mental states ranging from deliberate, intentional actions all the way down to consequences that, while not intended or even anticipated, should have been if a defendant was acting reasonably. As with actus reus superpowers can do some pretty unexpected things to the intent element.

Let’s start with a pretty obvious one: mind control. The X-Men’s Professor Xavier has demonstrated on numerous occasions that he is able to induce people to perform actions they might not otherwise do. So has the Martian Manhunter, J’onn J’onzz. Other characters, like Mastermind, can generate mental illusions, causing people to see things that aren’t there. Apart from the fact that using such powers may be an assault, we are also presented with a question as to whether people who commit criminal acts while under the influence of such powers possess the required mental state to be convicted.

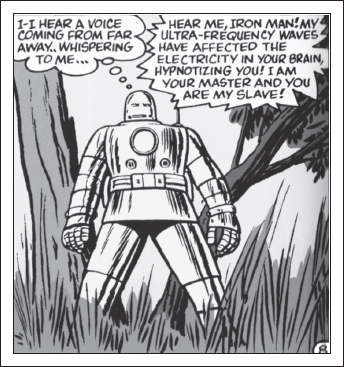

The answer probably depends on the nature of the mental powers at work. On one hand, the law recognizes that truly involuntary actions do not generally confer criminal liability. For example, the driver of a car who suffers an unexpected seizure cannot be held criminally liable for killing someone while in the throes of the seizure. 16 Or take the most basic example: If someone physically forces you to shoot someone else, actually pushing your finger on the trigger, the other person is responsible for the resulting death, not you. In Tales of Suspense #41, Dr. Strange 17 uses a device he made to control Tony Stark’s mind, forcing Stark to break him out of prison. 18 Breaking someone out of jail is obviously against the law, but it would be very difficult to convict Stark under these facts, assuming he could prove he was being controlled. Yes, he did bad things, but intent is just as much an element of criminal definitions as actions are.

No points for subtlety. Stan Lee, Jack Kirby et al., The Stronghold of Doctor Strange!, in TALES OF SUSPENSE (VOL. 1) 41 (Marvel Comics May 1963).

Illusions are a slightly different case. Here we have people acting under their own power and initiative, but faced with circumstances that are not as they appear to be. Under these circumstances the doctrine of “transferred intent” comes into play. If a defendant intends to commit a crime against victim A but somehow manages to victimize B instead, his intent is said to “transfer” from A to B. 19 If you think about it, given that the requirements for a crime are a guilty act combined with a guilty mind, the fact that the act and intent are not directed at exactly the same person doesn’t actually matter because both mind and act are still guilty.

This may sound bad for our heroes, but all is not lost. The question of whether a person acting under Mastermind’s influence could be guilty of a crime may actually depend on what the person thought was going on. If he was deceived into believing that he was acting in self-defense, then it could be difficult to convict him, assuming he is capable of convincing a jury that that’s what was going on. Almost this exact situation occurred when Maxwell Lord mentally manipulated Superman into thinking that Batman and Wonder Woman were actually Doomsday attacking Lois Lane. Superman tried to kill each of them as a result. In the end, Wonder Woman killed Lord in order to prevent future attacks. Superman’s belief in the necessity of the use of force may have been mistaken, but it was a reasonable and good faith belief caused by Lord’s mental manipulation.

Going one step further, what about effects that merely influence a person’s mind without controlling it, such as the Scarecrow’s fear gas or the alien symbiote that caused Eddie Brock to become the supervillain Venom? People under the influence of such effects could claim the defense of involuntary intoxication. As the Model Penal Code describes it, involuntary intoxication is “a disturbance of mental or physical capacities resulting from the introduction of substances into the body” and “is an affirmative defense if by reason of such intoxication the actor at the time of his conduct lacks substantial capacity…to appreciate its criminality.” 20 Note, however, that voluntary intoxication is not a defense: if someone puts on the symbiote suit knowing that it will affect his mind, any crimes he commits under its influence are on him. 21

A large percentage of Batman’s rogues gallery are characterized as insane: the Joker, the Riddler, Poison Ivy, Two-Face, etc. The list goes on, and this phenomenon isn’t limited to the DC Universe either. A frequent motivation for supervillains is that they’ve been driven mad by something in their past.

The specifics of this madness are usually not worked out all that well, certainly not in any way that the psychological or psychiatric establishments would recognize as describing any particular pathology. Regardless, this does raise the issue of whether such characters could successfully raise the insanity defense.

Insanity comes into play because it affects mens rea, the mental state with which acts are committed. Insanity and mental disturbances have been known to human society since ancient times, but in 1843, the English House of Lords—the English supreme court at the time—handed down what have become known as the M’Naghten Rules. 22 The M’Naghten test (or something like it) is still what many American courts use to decide whether a given defendant is insane or not. The scope of the insanity defense widened during the first half of the twentieth century, as psychology and psychiatry came into their own as disciplines, but the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan by John Hinckley, Jr.—who was found not guilty by reason of insanity—prompted Congress to tighten things up, largely restoring the status quo from the late nineteenth century. Many states followed the federal example.

The core of the M’Naghten test is to determine whether “the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or, if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.”

In other words, if a defendant can prove that as a result of some mental condition either (1) he didn’t know what he was doing, or (2) he didn’t know what he was doing was wrong, then he should be found not guilty by reason of insanity.

The “nature and quality” part of the test asks whether the defendant actually knew what was going on. The classic example is cutting a woman’s throat under the delusion that it was a loaf of bread. If a person truly were suffering from such a delusion (not an easy thing to prove!), then no conviction will lie, because there is no intent to kill. There isn’t even negligence, because a reasonable person exercising due care will not have any qualms about slicing himself some toast.

Likewise, if people simply lack the capacity to string together actions and consequences, there are procedural problems with holding them accountable for their actions. The mental state of children is a useful analogy. Just as very young children are not held responsible for the acts they commit because they simply cannot understand the implications and consequences of what they do, 23 a mentally disabled adult might be found not guilty for the same reasons.

Note that either prong of the test, if proved, will result in an acquittal guilty verdict, but both of the prongs require that the defendant be operating under a “disease of the mind” or a “defect of reason.” Being drunk won’t cut it, as the courts generally impute knowledge to voluntarily intoxicated people so as to avoid drunkenness becoming a complete defense to crimes. But similarly, simply being mistaken about what it was you were doing will not cut it either.

Also note that while a clinical diagnosis can certainly help here, whether or not the defendant has been diagnosed as mentally disturbed is, in a sense, irrelevant. Legal insanity and clinical mental illness are only loosely related. A defendant with no psychiatric history, if he can make out either prong of the test, can be found not guilty, and a defendant with a schizophrenia diagnosis can be convicted.

It is worth mentioning two other tests for insanity: the irresistible impulse test and the Model Penal Code’s substantial capacity test. 24 In short, the “irresistible impulse” test excuses a defendant acting under an irresistible impulse, and the substantial capacity test excuses a defendant if “as a result of mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law.” 25

The irresistible impulse test has been rejected by most jurisdictions, often vigorously. As the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania put it: “Moreover, the ‘defense’ offered in this case is simply an attempt to once again foist the ‘irresistible impulse’ concept upon this Court under different nomenclature, an attempt which we have consistently rejected and will continue to resist.” 26 However, it is available in some jurisdictions, such as Virginia: “The irresistible impulse defense is available where the accused’s mind has become so impaired by disease that he is totally deprived of the mental power to control or restrain his act.” 27 It is possible that many comic book supervillains could be excused by the irresistible impulse test if it were available in Gotham, since many supervillains seem to labor under an irresistible compulsion to commit crimes, often in a specific way (e.g., the Riddler’s compulsive riddling).

The Model Penal Code’s substantial capacity test has been adopted by a few jurisdictions, including Illinois, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. It, too, is broader than the M’Naghten rule, and it might excuse supervillains where M’Naghten does not. But it is definitely a minority position; the majority of United States jurisdictions, including federal courts, use the M’Naghten test.

Since we don’t know what test the comic book worlds use for insanity, we will focus on the M’Naghten test, as it is the majority position. Under the M’Naghten test, a lot of so-called criminally insane supervillains are not actually insane, or at least not insane in such a way as would render them not guilty.

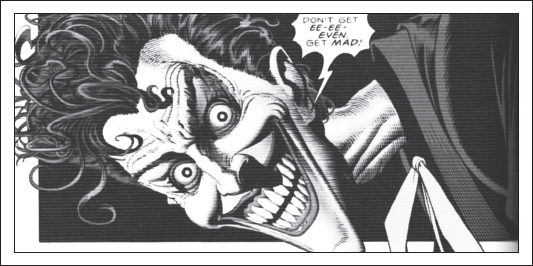

Take the Joker for example. In addition to occasionally denying that he is crazy—as he does at several points in the 2009 film The Dark Knight—the Joker does not actually display any likelihood, in most continuities anyway, of being eligible for an insanity defense. He almost always knows exactly what he is doing, and almost always knows that what he is doing is illegal. That, right there, means that he cannot successfully assert an insanity defense.

Perhaps the most detailed examination into the Joker’s “insanity” can be found in Alan Moore’s story Batman: The Killing Joke: “When you’re loo-oo-oony, then you just don’t give a fig. Man’s so pu-uu-uny, and the universe so big! If you hurt inside, get certified, and if life should treat you bad, don’t get ee-ee-even, get mad!” 28 Disturbed? Certainly. Evil even. But actually insane? It sounds as if the Joker has been reading too much Foucault and Nietzsche, but not as if he’s actually disoriented. And since it is that which the law is interested in when assessing mental culpability, simply adopting an abhorrent coping mechanism will not excuse the Joker from criminal guilt. It is this very line of reasoning that Heath Ledger’s Joker adopts when he confronts Harvey Dent in the hospital: “Introduce a little anarchy.” This is awful, but it isn’t actually unhinged.

Scary? Yes. Crazy? No. Alan Moore et al., THE KILLING JOKE (1988).

The same can likely be said of almost all the characters in Arkham Asylum. Very few if any of them are under the illusion that blowing up buildings is anything other than blowing up buildings. The Riddler commits crimes, knowing they are crimes, as a demonstration of his alleged intellectual superiority. 29 Black Mask is motivated by revenge. So, arguably, is Poison Ivy (at least in certain continuities). All of them know exactly what they’re doing, and most of them display extraordinary planning and strategic capabilities. They certainly are capable of forming the requisite mental state to be guilty of a crime. Many of them might be found not guilty under an irresistible impulse doctrine, but again, that doctrine has proved to be both judicially and politically disfavored, only operating in a small minority of jurisdictions.

But there are at least two characters that can probably never be found guilty of a crime even under the M’Naghten test: the Hulk and Doomsday.

The Hulk is going to be mostly immune from criminal prosecution, as when Bruce Banner goes into Hulk mode in most stories, he loses all ability to reason or plan. In those stories where the Hulk is a mindless ravaging beast, holding him criminally liable for his rampages will prove difficult, because he simply can’t form the mental state necessary for criminal culpability. In those stories where Banner remains more or less in control during his Hulk phases, the insanity defense should be unavailable, or at least a lot harder to prove. Of course, if Banner commits a crime while himself, his situation would be no different than any other criminal defendant.

Doomsday, on the other hand, is an almost elemental destroyer, possessing neither language nor reason, bent only on destruction. Exactly how that’s supposed to work is left as an exercise for the imagination, but it’s pretty clear from all of his appearances in comics that Doomsday isn’t really capable of forming any mental state, and not having a mind to speak of would certainly count as a “defect of reason.” In the story where Doomsday gains some modicum of awareness, the insanity defense would be unavailable, but he lost that awareness pretty quickly. 30

Then again, that would go for any of those villains who lack a sentient mind. Animals, machines, and other non-sentients would never be tried in open court. It does not require a court order for the dogcatcher to put down a rabid dog. Neither would it require a court order for a truly mindless enemy to be “punished” or otherwise dealt with. Whether or not rogue artificial intelligences would count is a discussion for another chapter, but to the extent that they are not considered persons, they would not be tried in court.

1. For criminal procedure, see chapter 4.

2. See, e.g., Muscarello v. United States, 524 U.S. 125 (1998).

3. There are certain traditions ethical, philosophical, and religious, which view any and all killing as impermissible, but we are concerned here not with ultimate moral significance but the current state of the legal system. A pacifist may think that killing in warfare or even self-defense is wrong, but that doesn’t make it illegal.

4. This will come up again when we talk about the status of non-human intelligences in chapter 13. For now, the law only recognizes the killing of a human being as murder, but that would likely change if genuine non-human intelligence, particularly in the form of a non-human civilization, were ever encountered.

5. OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES, THE COMMON LAW 3 (1909).

6. Though these distinctions were latent in the common law for centuries, they were only formalized in this spectrum in the 1960s with the introduction of the Model Penal Code, one of the most successful legal reforms in history.

7. See, e.g., Southern Farm. Bureau Life Ins. Co. v. Burney, 590 F. Supp. 1016 (E.D. Ark. 1984). See discussion in chapter 12.

8. For example, Madrox’s ability manifested from birth, unlike most mutants. If Madrox creates a duplicate while a minor, is he essentially foisting another child upon his parents or is he legally and financially responsible for the dupe himself? If Madrox typically has at least one dupe around at all times but not necessarily continuously, can he (or his parents) claim the dupe as a dependent?

9. Note that while suicide is generally legal, assisting, aiding, and counseling suicide generally are not.

10. Cruzan v. Director, Mo. Dept. of Health, 497 U.S. 261, 296 (1990) (quoting Blackburn v. State, 23 Ohio St. 146, 163 (1873)).

11. Pa. Cons. Stat. §901.

12. Model Penal Code § 211.1; See also, e.g., N.Y. Penal Law §§ 120.00, 120.05 (distinguishing between third degree and second degree assault).

13. Which raises the Second Amendment concerns discussed in chapter 1.

14. See, e.g., Adams v. Com., 534 S.E.2d 347 (Ct. App. Va. 2000).

15. See, e.g., Moore v. Regents of the University of California, 793 P.3d 479 (Cal. 1990) (en banc) (holding that a patient does not have a property right in his cells).

16. Of course, if the driver knew he was prone to seizures, the result is very different.

17. No relation to the master magician from later Marvel stories!

18. Stan Lee, Jack Kirby et al., The Stronghold of Doctor Strange!, in TALES OF SUSPENSE (VOL. 1) 41 (Marvel Comics May 1963).

19. People v. Bland, 48 P.3d 1107 (Cal. 2002) (“[T]he doctrine of transferred intent applies when the defendant intends to kill one person but mistakenly kills another. The intent to kill the intended target is deemed to transfer to the unintended victim so that the defendant is guilty of murder.”).

20. MODEL PENAL CODE §§ 2.08(5)(a) and 2.08(4).

21. Technically some jurisdictions recognize a limited defense of voluntary intoxication in that it may defeat the specific intent required for some crimes. For example, a drunken person may not be capable of forming the level of intent required for premeditated murder but could still be charged with involuntary manslaughter. If, however, the person became drunk knowing they would lose control, then they could be found guilty of premeditated murder.

22. M’Naghten’s Case, 8 Eng. Rep. 718 (H.L. 1843).

23. For example, at common law, children below the age of seven are conclusively presumed to be incapable of committing a crime, children between seven and fourteen are rebuttably deemed incapable of committing a crime, and those fourteen or over are presumed capable. 21 AM. JUR. 2d Crim. Law § 34. Some states have statutory minimum ages rather than following the common law rule.

24. The Model Penal Code is a model criminal law that has been adopted in many states. Although it is often modified by adopting states, it is nonetheless common to refer to the model law rather than individual state versions.

25. MODEL PENAL CODE § 4.01 (1962).

26. Com. v. Cain, 503 A.2d 959 (Pa. 1986).

27. Morgan v. Com., 646 S.E.2d 899, 902 (Ct. App. Va. 2007).

28. Alan Moore et al.,BATMAN: THE KILLING JOKE (1988).

29. The Riddler might have an argument to make under the “irresistible impulse” test, but would fail the M’Naghten test.

30. Jeph Loeb et al., Doomsday Rex, in SUPERMAN (VOL. 2) 175 (DC Comics December 2001).